Primary Care in the Philippine Health System

Noel L. Espallardo, MD, MSc, FPAFP and Nicolas R. Gordo, MD, MHA, CFP

Health service in the Philippines is provided in the public and private sector in hospitals, group practice clinics, individually-run clinics and midwifery clinics. They range in size from small basic service units operated by individuals to sophisticated tertiary hospitals. Health services are more for curative and personal care and less on preventive care. The private sector accounts for about 60 percent of the national expenditures on health. It also employs over 70 percent of all health professionals in the country. It is patterned from the North American models of health facilities economically dependent on Medicare reimbursement and fee-for-service payments. Health workers in the Philippines are mainly doctors, nurses, midwives, dentists and physical therapists. Majority of these health workers are employed in the private sector and a significant proportion (mainly nurses) are employed overseas. As a result, the private sector continues to be the dominant source of health care financing. The households’ out-of-pocket (OOP) payments accounted for 82.5% of all private expenditure in 2005 and increased to 83.5% of all private expenditure. These are the findings of the late and former health secretary Dr. Alberto “Quasi” Romualdez Jr. in his analysis of the Philippine Health System in 2011.1

What happened since then?

In this issue of our journal, we included a special theme “Primary Care in the Philippine Health System”. This is a very important issue to raise discussion and hopefully more research since this may be a pressing concern in the implementation of the Universal Health Care (UHC) reform. The first article by Lavina, et al., describes in general the nature of practice of primary care providers. Family physicians are still mostly in the private sector and a mixed of hospital and free-standing clinic still much the same as in 2011. Another article is by Carpio, which describes the nature and capacity of primary care clinics. The basic structure and available services are described. Because of some services lacking in regular primary care facilities, access to other essential primary services are provide in special facilities or hospitals as described in the paper of Cruz, et al. The paper of Nicodemus, et al. describes the process of care which is the primary care orientation of family practice. This is again a very important issue in the UHC.

Primary care is an endeavor marked by complexity and clinical uncertainty. The World Health Organization defined primary care as “the first level of contact of individuals, the family and the community within the national health system”.2 Its functions are the “provision of integrated, accessible health care services by clinicians who are accountable for addressing a large majority of personal health care needs, developing a sustained partnership with patients and practicing in the context of family and community”.3 Primary care physicians are providers of initial care and continuing point of contact, coordinator, and navigator in the health care delivery system for patients. They refer patients when appropriate for secondary or specialist care. Thus, primary care is the first level of health care where patients consult their health problems. At this level their curative and preventive health needs are provided. It should therefore be available in the community with no barriers to access and utilization. It is a generalist care, focused on the person with a felt health problem in the patient’s social context and biomedical process.4 This is the vision of the UHC and one of PAFP’s organizational priority as it makes itself very relevant to the Philippine health system.

Official Journal of the

Philippine Academy of Family Physicians

visit us @ www.thepafp.org

Contact Info

Philippine Academy of Family Physicians (PAFP) 2244 Taft Avenue, Malate, Metro Manila , Philippines 1004 Telephone Nos: (+632) 8516-2900; (+632) 8405-0140 E-mail: [email protected]

The Filipino Family Physicians 2021 © All Rights Reserved.

Scaling up Primary Health care in the Philippines: Lessons from a Systematic review of Experiences of community-based Health Programs

- Edna Estifania A. Co

- Ruben N. Caragay

- Jaifred Christian F. Lopez

- Isidro C. Sia

- Leonardo R. Estacio

- Hilton Y. Lam

- Jennifer S. Madamba

- Regina Isabel B. Abola

- Maria Fatima A. Villena

Background. In view of renewed interest in primary health care (PHC) as a framework for health system development, there is a need to revisit how successful community health programs implemented the PHC approach, and what factors should be considered to scale up its implementation in order to sustainably attain ideal community health outcomes in the Philippines.

Objective and methodology. Using the 2008 World Health Report PHC reform categories as analytical framework, this systematic review aimed to glean lessons from experiences in implementing PHC that may help improve the functioning of the current decentralized community-level health system in the country, by analyzing gathered evidence on how primary health care evolved in the country and how community health programs in the Philippines were shaped by the PHC approach.

Results. Nineteen (19) articles were gathered, 15 of which documented service delivery reforms, two (2) on universal coverage reforms, three (3) on leadership reform, and one (1) on public policy. The literature described how successful PHC efforts centered on community participation and empowerment, thus pinpointing how community empowerment still needs to be included in national public health thrusts, amid the current emphasis on performance indicators to evaluate the success of health programs.

Conclusion and recommendations. The studies included in the review emphasize the need for national level public health interventions to be targeted to community health and social determinants of health as well as individual health. Metrics for community empowerment should be developed and implemented by government towards sustainable health and development, while ensuring scientific validity of community health interventions.

Most read articles by the same author(s)

- Alejandra M. Libunao, Reneepearl Kim P. Sales, Jaifred Christian F. Lopez, Ma. Rowena H. Alcido, Lester Sam A. Geroy, Joseph V. Oraño, Rafael Deo F. Estanislao, Effect of Personality, Power, and Emotion on Developing the 2017-2022 Philippine Health Research Agenda: A Case Study , Acta Medica Philippina: Vol 53 No 3 (2019): National Unified Health Research Agenda (NUHRA)

- Paul Ernest N. de Leon, Reneepearl Kim P. Sales, Lester Sam A. Geroy, Jaifred Christian F. Lopez, Strengthening Science and Technology for Health Research: Perspectives from Trade, Development, and Innovation , Acta Medica Philippina: Vol 53 No 3 (2019): National Unified Health Research Agenda (NUHRA)

- Chiqui M. de Veyra, Miguel Manuel C. Dorotan, Alan B. Feranil, Teddy S. Dizon, Lester Sam A. Geroy, Jaifred Christian F. Lopez, Reneepearl Kim P. Sales, Stakeholders in the Development of the National Unified Health Research Agenda of the Philippines , Acta Medica Philippina: Vol 53 No 3 (2019): National Unified Health Research Agenda (NUHRA)

- Jaifred Christian F. Lopez, Teddy S. Dizon, Regin George Miguel K. Regis, Achieving a Responsive Philippine Health Research Agenda: An Analysis of Research Outputs and Underlying Factors , Acta Medica Philippina: Vol 53 No 3 (2019): National Unified Health Research Agenda (NUHRA)

- Jaifred Christian F. Lopez, Chiqui M. de Veyra, Lester Sam A. Geroy, Reneepearl Kim P. Sales, Teddy S. Dizon, Eva Maria Cutiongco-de la Paz, Envisioning the Health Research System in the Philippines by 2040: A Perspective Inspired By AmBisyon Natin 2040 , Acta Medica Philippina: Vol 53 No 3 (2019): National Unified Health Research Agenda (NUHRA)

- Jaifred Christian F. Lopez, Arlene S. Ruiz, Reneepearl Kim P. Sales, Maria Angeli C. Magdaraog, Teddy S. Dizon, Lester Sam A. Geroy, Mapping the Influence of Socioeconomic Development Plans on Philippine Health Research Agenda: A Descriptive Study , Acta Medica Philippina: Vol 53 No 3 (2019): National Unified Health Research Agenda (NUHRA)

- Jaifred Christian F. Lopez, Reneepearl Kim P. Sales, Regin George Miguel K. Regis, Katherine Ann V. Reyes, Beverly Lorraine C. Ho, Strengthening the Policy Environment for Health Research in the Philippines: Insights from a Preliminary Analysis of Existing Policies , Acta Medica Philippina: Vol 53 No 3 (2019): National Unified Health Research Agenda (NUHRA)

- Maria Lourdes K. Otayza, Chiqui M. de Veyra, Jaifred Christian F. Lopez, Implementing Lessons Learned from Past Versions of the Philippine National Unified Health Research Agenda , Acta Medica Philippina: Vol 53 No 3 (2019): National Unified Health Research Agenda (NUHRA)

- Noel R. Juban, Hilton Y. Lam, Ruzanne M. Caro, Jorge M. Concepcion, Tammy L. Dela Rosa, A’Ericson Berberabe, Karen June P. Dumlao, Disability Weight Determination for Road Traffic Injuries in the Philippines: Metro Manila Scenario , Acta Medica Philippina: Vol 53 No 1 (2019)

- Ma. Rochelle Buenavista-Pacifico, Alexis L. Reyes, Bernadette C. Benitez, Esterlita Villanueva-Uy, Hilton Y. Lam, Enrique M. Ostrea, Jr., The Prevalence of Developmental Delay among Filipino Children at Ages 6, 12 and 24 Months Based on the Griffiths Mental Development Scales , Acta Medica Philippina: Vol 52 No 6 (2018)

Make a Submission

Information

- For Readers

- For Authors

- For Librarians

- For Peer Reviewers

Published by the University of the Philippines Manila Indexed in Scopus, Google Scholar, Asean Citation Index (ACI), Western Pacific Region Index Medicus (WPRIM) and Herdin Plus Publishing since 1939.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BMC Health Serv Res

Experiences from the Philippine grassroots: impact of strengthening primary care systems on health worker satisfaction and intention to stay

Regine ynez h. de mesa.

1 University of the Philippines Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines

Jose Rafael A. Marfori

2 University of the Philippines Manila, Manila, Philippines

Noleen Marie C. Fabian

Romelei camiling-alfonso, mark anthony u. javelosa, nannette bernal-sundiang, leonila f. dans, ysabela t. calderon, jayson a. celeste, josephine t. sanchez, cara lois t. galingana, ramon pedro p. paterno, jesusa t. catabui, johanna faye e. lopez, maria rhodora n. aquino, antonio miguel l. dans, associated data.

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available to uphold participant privacy. Datasets are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Inequities in health access and outcomes persist in low- and middle-income countries. While strengthening primary care is integral in improving patient outcomes, primary care networks remain undervalued, underfunded, and underdeveloped in many LMICs such as the Philippines. This paper underscores the value of strengthening primary care system interventions in LMICs by examining their impact on job satisfaction and intention to stay among healthcare workers in the Philippines.

This study was conducted in urban, rural, and remote settings in the Philippines. A total of 36 urban, 54 rural, and 117 remote healthcare workers participated in the study. Respondents comprised all family physicians, nurses, midwives, community health workers, and staff involved in the delivery of primary care services from the sites. A questionnaire examining job satisfaction (motivators) and dissatisfaction (hygiene) factors was distributed to healthcare workers before and after system interventions were introduced across sites. Interventions included the introduction of performance-based incentives, the adoption of electronic health records, and the enhancement of diagnostic and pharmaceutical capabilities over a 1-year period. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test and a McNemar’s chi-square test were then conducted to compare pre- and post-intervention experiences for each setting.

Among the factors examined, results revealed a significant improvement in perceived compensation fairness among urban ( p = 0.001) and rural ( p = 0.016) providers. The rural workforce also reported a significant improvement in medicine access ( p = 0.012) post-intervention. Job motivation and turnover intention were sustained in urban and rural settings between periods. Despite the interventions introduced, a decline in perceptions towards supply accessibility, job security, and most items classified as job motivators was reported among remote providers. Paralleling this decline, remote primary care providers with the intent to stay dropped from 93% at baseline to 75% at endline ( p < 0.001).

The impact of strengthening primary care on health workforce satisfaction and turnover intention varied across urban, rural, and remote settings. While select interventions such as improving compensation were promising for better-supported settings, the immediate impact of these interventions was inadequate in offsetting the infrastructural and staffing gaps experienced in disadvantaged areas. Unless these problems are comprehensively addressed, satisfaction will remain low, workforce attrition will persist as a problem, and marginalized communities will be underserved.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12913-022-08799-1.

Introduction

Background of the study.

The passage of the Universal Health Care Law in 2019 marked the Philippines’ commitment to achieve equitable health coverage for all, an endeavor shared by countries worldwide [ 1 ]. However, even if primary care is acknowledged as an essential element to achieving universal health coverage [ 1 – 3 ] and as a mechanism for improved health equity [ 4 ], the lack of health system readiness remains an issue. In the Philippines, as in many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [ 5 , 6 ], primary care networks remain undervalued, underfunded, and ultimately underdeveloped [ 7 ]. This has contributed to compromised health outcomes such as significantly shorter life expectancies [ 8 ] and higher child mortality rates among the country’s poorest quintiles [ 9 ]. National data reveals that 6 out of 10 Filipino deaths were medically unattended—with only the capital region of Metro Manila exhibiting higher attended than unattended deaths [ 10 ]. The World Health Organization sets the ideal skilled health worker (i.e., physicians, nurses, and midwives) to population ratio at 4.45:1000 [ 11 ]. However, human resources for health (HRH) deficits of at least 60,000 doctors, 121,000 nurses, and 109,000 midwives were reported among Philippine public facilities alone [ 12 ]. This bears significance as over 83% of outpatient visits from the two poorest wealth quintiles were made to government-funded community health stations [ 13 ].

Largely driven by workforce maldistribution and system fragmentation, inequities in health have persisted in the absence of a well-supported primary care network [ 14 ]. Disparities in health access have likewise had a disproportionate impact on low-income families [ 13 ] and geographically disadvantaged regions [ 15 ]. In rural and remote areas, health stations are often gravely understaffed, lacking supplies of basic drugs, and left without the regular supervision of an attending physician [ 16 ]. Despite severe HRH shortages, the Philippines remains a leading exporter of health professionals with nearly 85% of locally trained nurses deployed overseas [ 17 ]. The country’s economic reliance on the mass exodus of its workforce without comprehensively addressing the steep decline in HRH retention has adversely impacted health service delivery in underserved communities [ 18 ]. Thus, improving the retention of HRH is at the cornerstone of operationalizing primary care systems in LMICs like the Philippines.

Literature examining emigration patterns forward the substantial impact of job satisfaction on turnover intention. Locke broadly defines job satisfaction as “a pleasurable or positive emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one’s job or job experiences” [ 19 ]. A myriad of job attributes, such as workload, training opportunities, compensation, and enabling environments, influence job satisfaction [ 20 ]. Herzberg’s two-factor theory distinguishes between attributes that induce satisfaction from those that lead to dissatisfaction. These attributes are categorized as a) motivators and b) hygiene factors [ 21 ]. Motivators such as workplace morale and job involvement were linked to employee satisfaction, whereas hygiene factors such as compensation and job security were associated with dissatisfaction if not aptly addressed [ 22 ]. While Herzberg’s theory suggests that the absence of motivators may not necessarily lead to attrition, environments that only support good workplace hygiene can result in retaining an unsatisfied workforce [ 23 ]. Exploring the impact of strengthened primary care on HCW satisfaction has widespread implications for health outcomes in LMICs. Sustained contentment towards various workplace attributes enables HCWs to direct optimal focus towards patient care. With low HCW retention directly resulting in poor outcomes [ 24 ], HCW satisfaction proves integral for mitigating the effects of workforce maldistribution in LMICs.

Study objectives

Adopting Herzberg’s two-factor framework for analyzing job satisfaction, the objectives of this study are: 1) to evaluate the impact of strengthening urban, rural, and remote primary care system interventions on HCW satisfaction; and 2) to compare turnover intention among HCWs before and after the intervention period.

Methodology

Study design.

A pretest-posttest design was used to assess HCW job satisfaction and turnover intention across urban, rural, and remote settings in the Philippines. This entailed data collection of satisfaction measures through a single pre-test, followed by an intervention, and then a collection of post-test data on the same measure. The present study was conducted as part of the Philippine Primary Care Studies (PPCS) program, a longitudinal and multi-sited research series aimed at strengthening primary care systems through patient-centered interventions. In 2016, PPCS piloted its urban program to model comprehensive primary care, which provided free access to outpatient services, laboratory and diagnostic procedures, and medicines to eligible patients. This model and its package of interventions were extended to the study’s rural and remote sites in 2019. In delivering these interventions, HCWs were supported through enhanced capacity-building, the development of electronic health records (EHR), and the introduction of performance-based financial incentives. The impact of these interventions was then assessed, with HCW job satisfaction being one of the eight health system outcome measures outlined in the PPCS primary care model [ 25 ].

Instrumentation

A pre-validated Stayers questionnaire [ 26 ] initially used to measure job satisfaction and turnover intention among remote primary care physicians [ 27 ] was adapted for this study. The adapted instrument comprised a Likert-type section to measure satisfaction/dissatisfaction and a multiple-choice assessment to measure turnover intention. Following Herzberg’s two-factor framework, Likert items were classified as: 1) motivator factors; and 2) hygiene factors (see Table Table1 1 ).

List of Likert scale items by Herzberg’s two-factor classification

Since the original instrument was used to measure physician satisfaction in a remote setting, several sections of the original questionnaire did not apply to the practice types and settings examined in this study. As such, only 18 of the original 77 items were maintained (see Appendix A ) to enhance questionnaire adaptability. Overall consistency for the tool used in this study proved reliable [ 28 ] with a Cronbach’s α score of 0.8.

Sampling and survey distribution

This study was conducted across three pilot sites, namely: a) an urban site—the University of the Philippines Health Service Diliman in Metro Manila; b) the rural municipality of Samal, Bataan; and c) the remote municipality of Bulusan, Sorsogon. A census of all HCWs from the urban, rural, and remote sites was obtained—totaling 36, 54, and 117 respondents respectively. Self-administered questionnaires were distributed to the respondents in September 2016 for the baseline period and again in December 2017 for the endline assessment at the urban site. Baseline surveys for rural and remote sites were distributed during the study preparation phase in April 2019 and assessed after the one-year implementation in June 2020 through the endline survey. Verbal and written consent from each respondent was obtained before survey distribution.

Data analysis

Data gathered were encoded in Microsoft Excel and were analyzed using Stata version 12.0 and R version 3.5.0. Demographics were expressed through percentage comparisons for categorical variables, whereas mean scores were used to compare continuous data. Likert responses were scored as 1 = Strongly Disagree (SD); 2 = Disagree (D); 3 = Neutral (N); 4 = Agree (A); 5 = Strongly Agree (SA). Upon analysis, Likert-type responses were examined per item and as dichotomized responses (i.e., generally dissatisfied for scores 1–3 and generally satisfied for scores 4–5) [ 29 – 31 ]. Multiple-choice items on intent to stay were encoded as a binary before analysis. HCWs intending to leave were segregated from HCWs intending to stay in their jobs indefinitely. To determine the significance between baseline and endline scores, hypothesis testing was conducted using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for ordinal data and McNemar’s chi-square test for dichotomous data. Hodges-Lehmann point estimates reflecting the direction of change in Likert satisfaction scores between periods were reported along with their 95% confidence intervals (see Appendix B ). P -values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant for this study. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the University of the Philippines Manila Research Ethics Board (UPMREB – 2015-489-01) and the Philippines’ Department of Health Single Joint Research Ethics Board (SJREB – 2029-55). Ethics approval was annually renewed for all study sites. Furthermore, verbal and written informed consent was obtained from all health workers who have participated in this study.

Demographic profile

Majority of our respondents were female. Our participants were HCWs from the sites and included family physicians, nurses, midwives, community health workers, and staff. The urban site had the most number of physicians while the rural and remote sites being serviced by community health workers (CHWs or locally referred to as barangay health workers) who bridge the gap between health systems and localities [ 25 ]. The distribution of HCWs, particularly the doctor to patient ratio, reflects the disparities across communities. The average length of stay in years was also highest in the urban site (14 years) and lowest in the remote site (11 years). Most HCWs from the urban (86%) and remote (73%) sites reported no previous work experience apart from the job they occupied during the survey period (Table (Table2 2 ).

Demographic profile of survey respondents

Comparison of health worker satisfaction across sites

The baseline proportion of generally satisfied HCWs was relatively low at the urban site compared to rural and remote responses towards job motivators. While almost all urban HCWs felt secure with their current jobs (92%), far less perceived their work as enjoyable (63%) or felt positively towards their workplace morale (72%) at baseline. In contrast to urban data, the majority of rural and remote HCWs (> 85%) were generally more motivated despite experiencing moderate to low workplace hygiene at the start of the study period. Among hygiene factors, over half of the workforce across all sites felt undercompensated during the baseline period. The baseline percentage of HCWs satisfied with their job hygiene was lowest at the remote site, with less than 30% of remote HCWs expressing sufficient access to medical equipment (Table (Table3 3 ).

McNemar’s chi-square comparison of generally satisfied HCWs from the baseline and endline periods

* p < 0.05; statistically significant difference in the proportion of generally satisfied responses

We found a marked increase in the endline proportion of generally satisfied HCWs towards perceived compensation fairness at the urban and rural facilities and access to medicines at the rural site. However, significantly fewer rural HCWs felt satisfied with the accessibility of equipment during the endline period. The endline proportion of satisfied urban and rural HCWs remained constant towards motivation factors. However, there was a decrease in satisfaction on workplace morale and enjoyment towards HCWs working in the remote community.

We also found two notable improvements in scores, specifically in: a) perceived compensation fairness among urban ( p = 0.001) and rural HCWs ( p = 0.016), and b) perceived sufficiency in medicine supply among rural HCWs ( p = 0.012). Point estimates on the change in scores for both sites suggest that median satisfaction on perceived compensation fairness increased by a full rank (Table (Table4). 4 ). For the urban and rural cohorts, median satisfaction scores increased from being neither satisfied nor dissatisfied [ 3 ] at baseline to being satisfied [ 4 ] at the end of the study (see Appendix B ).

Wilcoxon signed-rank test comparison of median satisfaction scores between baseline and endline periods

1 P < 0.05; statistically significant increase between baseline and endline ranks

** P < 0.05; statistically significant decrease between baseline and endline ranks

When remote data were analyzed, significantly lower satisfaction scores were reported for both motivator and hygiene factors. Satisfaction towards motivating factors was significantly lower at the end of the study—with workplace morale exhibiting the steepest decline ( p < 0.001). Remote HCWs also reported lower satisfaction scores towards hygiene factors like supply accessibility and job security post-intervention. In contrast to urban andrural responses, no statistically significant changes were noted in perceived compensation fairness at the remote site.

Comparison of intention to stay across sites

Intention to stay did not change in the urban site after the primary care system interventions ( p = 1.000 ) . More HCWs in the rural site indicated intention to stay (baseline: 75% vs. endline: 89%; p = 0.090) while fewer HCWs practicing in the remote site intended to stay post-intervention (baseline: 93% vs. endline: 76%; p < 0.001) (Table (Table5 5 ).

McNemar’s chi-square test results on intent-to-stay across sites

* P < 0.05; statistically significant difference in the proportion of generally satisfied responses

Health sector performance hinges on a competent, motivated, and well-supported workforce. If performance gains are to be realized when transitioning from vertical disease-based health programs to integrated primary care systems, HCW satisfaction must be considered as a desired outcome measure. Technical training and enhanced incentives are necessary for improving HCW satisfaction [ 32 ]. However, the existing curricula of health-related professions in the Philippines have limited content and training on primary care. An appraisal conducted on HCW job motivation underscores a systemic approach in improving satisfaction scores and workforce retention [ 33 ]. According to existing literature, insufficient performance incentives and compensation have resulted in poor health outcomes and HCW maldistribution across challenging environments such as the Philippines [ 34 – 37 ]. Non-financial incentives also play a role in attracting physicians to practice in rural health systems, which includes supervision and being near to their families. To address maldistribution, this study initiated several interventions to encourage system integration and HCW capacity-building [ 38 ]. Primary care training workshops and access to UpToDate were provided to HCWs throughout the study period. Additional pharmacies and laboratories were incorporated into existing networks in the rural and remote sites to expand drug supply and services. A unified EHR system was also introduced to all sites to ease patient intake, diagnosis, referral, and monitoring.

In the study’s rural and remote sites, clinical care is delivered across a multitude of facilities. These range from central health units that house a limited number of physicians, to smaller community health stations that primarily operate through the services rendered by nurses, midwives, and CHWs. The introduction of the EHR enhanced system integration across these facilities through a unified patient database. In effect, the EHR enabled previously underutilized community health stations to refer patients to the central health unit and to likewise produce laboratory requests or prescriptions with the remote approval of the patient’s attending primary care physician. Rural HCWs were less dissatisfied with their ability to prescribe medical drugs post-intervention. As supported by post-intervention studies conducted in rural terrains, this likely resulted from the expansion of these services alongside the remote referral/approval capabilities provided by the EHR [ 39 , 40 ]. The central health unit of the rural site experienced the highest number of consultations year-round. As such, the referral/approval capabilities aided in distributing patients across the network of available community health stations. While most rural satisfaction scores have remained consistent, majority of rural HCWs (> 90%) were already highly satisfied with all motivational factors during the baseline period. Considerable institutional support and tight integration pre-intervention may have contributed to the high confidence level demonstrated by rural HCWs at baseline [ 41 ]. Their overall satisfaction was mirrored in their greater intention to stay after the implementation of primary care system interventions.

Dissatisfaction towards perceived compensation fairness was consistently high pre-intervention. To address possible gaps in remuneration, performance-based financial incentives were provided to all primary care providers across the three sites during the intervention period. These incentives were calculated based on completed consultations by the involved HCWs per consult. When a patient is initially assessed by a nurse and referred to an attending physician, both HCWs would merit financial incentives in the implemented payment scheme. As indicated in research evaluating the impact of HCWs income, adequate wage provisions are vital to system-incentivized performance improvements [ 42 , 43 ] and coordinated care among HCWs within the primary care network [ 25 ]. The results of this study reveal that perceptions towards compensation fairness significantly improved among urban and rural HCWs post-intervention. This may largely be due to the provision of the aforementioned incentives as wages and other fringe benefits across all sites remained the same.

Job hygiene at the remote site showed a conservative decline. Remote HCWs were more dissatisfied with supply accessibility and job security post-intervention. Although urban and rural job hygiene improved with the introduction of financial incentives, the remote site reported no significant difference in HCW perceptions towards perceived compensation fairness post-intervention. A slight decline in the level of satisfaction and the proportion of generally satisfied HCWs were also noted towards several motivation factors. Four underlying contexts can be examined to qualify these results: 1) delayed incentivization [ 36 ]; 2) HCW maldistribution [ 42 ]; 3) weak infrastructure [ 44 ]; and 4) the impact of COVID-19 [ 45 ]. Irregular payments and delayed remuneration contribute to HCW dissatisfaction and ultimately poor retention [ 46 ]. Resulting from administrative delays in the disbursement of additional financial incentives, most remote HCWs received these incentives several months after their services were rendered. This may have significantly mitigated the intended positive impact of incentivization. Although delays in incentive payouts occurred in other sites, the impact of delayed remuneration may have been more difficult to ignore in the remote site given the abundance of other challenges shouldered by its workforce.

Apart from administrative challenges, the demographic composition of remote-based staff likely had some impact on the reported dissatisfaction towards several hygiene factors. CHWs comprised the vast majority of the remote-based workforce surveyed in this study. CHWs are part-time volunteer workers, rendering them ineligible for receiving a regular wage, unlike other primary care providers. Non-urban CHWs typically receive a marginal monthly allowance of Php 1150 (estimated at $24.00 per month) alongside other benefits such as free groceries or medical care depending on the local government unit [ 47 ]. While intrinsic job factors such as perceived social prestige and acquired technical skills have been shown to be critical motivators for CHWs in existing literature [ 47 ], heightened dissatisfaction towards the inadequacy of job hygiene factors relative to the work expected may increase turnover intention as Herzberg’s theory and the findings of this study present.

The sporadic distribution of HCWs, particularly physicians, in remote areas proves potentially hazardous for providers—threatening to overload both staff and infrastructure. Expanding primary care providers’ responsibilities to include public health service delivery may cause low job satisfaction due to inadequate work autonomy and high dissatisfaction due to income mismatch [ 48 ]. HCWs are expected to deliver quality clinical services to individual patients while assuming population health roles for specific health programs (i.e., vaccination, sanitation). Despite the range of tasks HCWs are expected to fulfill, infrastructural gaps in the remote site vastly surpass those of other sites. Intermittent internet connectivity, unreliable transportation, poor maintenance of select health stations, and frequent electrical outages are additional challenges to an already understaffed workforce. These challenges potentially diminish health outcomes, rendering clinical efforts futile or frustrating, and may reinforce low regard for the primary care system—amongst providers and patients [ 44 , 49 ]. With infrastructural lacunae and the regular onslaught of natural disasters in this Pacific-facing site, seemingly minor inconveniences have resulted in adverse delays. This is evident in hours of back-encoding patient data, longer patient queues, difficulties in servicing remote communities, and challenges in referring patients throughout the primary care network.

Enhanced retention necessitates providing basic resources required for the job—including improved infrastructure, a unified EHR, supply accessibility, and fair compensation. Furthermore, experiences from the remote site suggest that financial incentives prove more effective once other infrastructural hurdles have already been addressed. System interventions must indeed provide enabling environments to prevent dissatisfaction and reduce workforce attrition. However, as Herzberg’s theory posits, job satisfaction is primarily achieved with a motivated workforce. In the urban site, most HCWs were not dissatisfied with hygiene factors such as workload and overall job security. However, satisfaction with motivational factors was still lower compared to rural and remote scores. Despite being in a well-supported job environment that retained its workforce the longest compared to other sites, urban data shows that good job hygiene alone does not ascertain HCW satisfaction. Providing non-monetary incentives such as training opportunities, pathways for career advancement, and involvement in clinical decision-making proves foremost essential in improving job satisfaction.

Scope and limitations

This study employed a diachronic approach in evaluating HCW satisfaction across three sites, with varying baseline and endline periods per site due to funding and infrastructural constraints. The endline responses from the rural and remote sites were obtained shortly after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. As such, the shifting social and economic climate may have affected responses at the time of the survey. Other factors such as survivor bias may have had some impact on the reported results. Only respondents with matched scores (i.e., HCWs present in both baseline and endline periods) were included for analysis. Other factors influencing satisfaction were not controlled. As such, the magnitude of each factor and its corresponding effect on satisfaction and intent to stay was outside the scope of the present study. Attempts to further contextualize satisfaction scores have been undertaken to grasp a holistic understanding of HCW experience. These were done through informal interviews with HCWs, and long-term participant observation of field teams deployed to each site. However, we were unable to measure the role of corruption in this study and we suggest that future studies collect data on this to better qualify and quantify its effect. With these limitations outlined, this research places greater focus on the possible impact of specific interventions undertaken in strengthening primary care networks in each area.

This study presents the observed impact of strengthening urban, rural, and remote primary care system interventions on primary care providers. Using Herzberg’s two-factor classification, overall job satisfaction and turnover intention were examined through motivational and hygiene factors experienced in each site before and after the implementation of study interventions. Perceptions towards job hygiene factors improved post-intervention at urban and rural sites—likely because of performance-based financial incentives provided to all HCWs during the study. Alongside the provision of monetary incentives, the expansion of service delivery networks to include additional pharmacies in the rural site showed a positive impact among HCWs in their regard for medical supply.

Despite attempts to strengthen the existing primary care system and potentially exacerbated by the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, infrastructural deficits have contributed to lower motivation and higher dissatisfaction among remote HCWs during the endline period. Reducing dissatisfaction by addressing hygiene factors at the workplace proves vital in retaining HCWs in remote and disadvantaged areas. This may be done by providing adequate remuneration and ensuring work environments support the demands of person-centered integrated care. However, targeting system interventions aimed at improving motivational factors may render beneficial in retaining a satisfied workforce in the long term. Strengthening primary care systems must, therefore, consider interventions that address motivational and job hygiene needs to improve healthcare worker satisfaction and intention to stay. This includes addressing HCW needs, strengthening infrastructural support, and enhancing primary care training across all HCW cadres. In doing so, patient-centered primary care can ultimately be better sustained by the very workforce it is founded upon.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their gratitude to all healthcare worker participants, the University of the Philippines Health Service administration, and the local government units of Samal and Bulusan for their unwavering support towards the objectives of this research. We also wish to acknowledge the expertise of Arianna Maever Amit – with whom the research team consulted with during the revision of the present manuscript. Her critical insight into manuscript ensured all assertions made by the research team were evidence-based and punctiliously reported.

Abbreviations

Authors’ contributions.

ALD, JAM, LFD, RPP, and MPR conceptualized the program as a whole. RDM and ALD conceptualized the submitted manuscript. CTG, JFL, and NBS gathered and processed study data. MAJ, MPR, and RDM statistically analyzed the elicited results. RDM led the development of the manuscript, writing majority of the enclosed sections. NCF and YTC assisted in cross-referencing and revising the manuscript. All authors suggested substantial revisions, commented, and approved the final manuscript.

This study was supported by the Philippine Department of Health, the Philippine Health Insurance Corporation (PhilHealth), the University of the Philippines Center for Integrative and Development Studies (UP-CIDS), the Emerging Interdisciplinary Research Program (EIDR), the Philippine Council for Health Research and Development (PCHRD) and the National Academy of Science and Technology (NAST) under the Philippines’ Department of Science and Technology (DOST).

Availability of data and materials

Declaration.

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the University of the Philippines Manila Research Ethics Board (UPMREB – 2015-489-01) and the Philippines’ Department of Health Single Joint Research Ethics Board (SJREB – 2029-55). Ethics Board approval was annually renewed for all study sites. The methodology was executed in accordance with the rules of the aforementioned ethical boards and guidelines under the Declaration of Helsinki. Furthermore, verbal and written informed consent was obtained from all health workers who have participated in this study.

All data obtained for this study were anonymized upon data collection and analysis. No personally identifiable participant information is included in the present manuscript. All participants of this research consented to the publication of their anonymized data.

All authors have no relevant or competing conflicts of interest to declare.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- français

- español

- português

Related Links

Philippines: a primary health care case study in the context of the covid-19 pandemic.

View Statistics

Description, collections.

- Publications

Show Statistical Information

- 1. Headquarters

Browse Econ Literature

- Working papers

- Software components

- Book chapters

- JEL classification

More features

- Subscribe to new research

RePEc Biblio

Author registration.

- Economics Virtual Seminar Calendar NEW!

Primary Health Care for Noncommunicable Diseases in the Philippines

- Author & abstract

- Related works & more

Corrections

- Ulep, Valerie Gilbert T.

- Casas, Lyle Daryll D.

Suggested Citation

Download full text from publisher.

Follow serials, authors, keywords & more

Public profiles for Economics researchers

Various research rankings in Economics

RePEc Genealogy

Who was a student of whom, using RePEc

Curated articles & papers on economics topics

Upload your paper to be listed on RePEc and IDEAS

New papers by email

Subscribe to new additions to RePEc

EconAcademics

Blog aggregator for economics research

Cases of plagiarism in Economics

About RePEc

Initiative for open bibliographies in Economics

News about RePEc

Questions about IDEAS and RePEc

RePEc volunteers

Participating archives

Publishers indexing in RePEc

Privacy statement

Found an error or omission?

Opportunities to help RePEc

Get papers listed

Have your research listed on RePEc

Open a RePEc archive

Have your institution's/publisher's output listed on RePEc

Get RePEc data

Use data assembled by RePEc

- Transparency Seal

- Citizen's Charter

- PIDS Vision, Mission and Quality Policy

- Strategic Plan 2019-2025

- Organizational Structure

- Bid Announcements

- Site Statistics

- Privacy Notice

- Research Agenda

- Research Projects

- Research Paper Series

- Guidelines in Preparation of Articles

- Editorial Board

- List of All Issues

- Disclaimer and Permissions

- Inquiries and Submissions

- Subscription

- Economic Policy Monitor

- Discussion Paper Series

- Policy Notes

- Development Research News

- Economic Issue of the Day

- Annual Reports

- Special Publications

Working Papers

Monograph Series

Staff Papers

Economic Outlook Series

List of All Archived Publications

- Other Publications by PIDS Staff

- How to Order Publications

- Rate Our Publications

- Press Releases

- PIDS in the News

- PIDS Updates

- Legislative Inputs

- Database Updates

- GIS-based Philippine Socioeconomic Profile

- Socioeconomic Research Portal for the Philippines

- PIDS Library

- PIDS Corners

- Infographics

- Infographics - Fact Friday

- Infographics - Infobits

Primary Health Care and Management of Noncommunicable Diseases in the Philippines

- Ulep, Valerie Gilbert T.

- Casas, Lyle Daryll D.

- noncommunicable diseases

- health systems

- primary healthcare

As the Philippines adopts major reforms under the Universal Health Care Act and embarks on an integrated and primary healthcare-oriented system, it is critical to assess its readiness to manage noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), the leading disease burden in the country. This study assesses the readiness of the primary healthcare system to handle NCDs, in the context of governance, financing, service delivery, human resources, and information and communications technology. It identifies challenges in the availability, quality, and equity of the health system, which hamper the provision of comprehensive and continuous healthcare services in local communities.

Download Publication

Please let us know your reason for downloading this publication. May we also ask you to provide additional information that will help us serve you better? Rest assured that your answers will not be shared with any outside parties. It will take you only two minutes to complete the survey. Thank you.

Related Posts

Publications.

Video Highlights

- How to Order Publications?

- Opportunities

Essay on Health Care System In The Philippines

Students are often asked to write an essay on Health Care System In The Philippines in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Health Care System In The Philippines

The basics of health care in the philippines.

The Philippines’ health care system is a set of health services provided by public and private providers. Public health care is managed by the Department of Health (DOH), while private health services are offered by various hospitals and clinics.

Public Health Care

Public health care is available to everyone. It is funded by taxes and contributions from workers. The Philippine Health Insurance Corporation (PhilHealth) is the main public health care provider. It gives Filipinos access to basic medical services.

Private Health Care

Private health care is offered by private hospitals and clinics. It’s usually more expensive than public health care. People who can afford it often choose private care for more personalized service and shorter waiting times.

Challenges in the Health Care System

The health care system in the Philippines faces many challenges. These include a lack of resources, unequal access to health services, and a high cost of care. The government is working on these issues to improve the health care system.

Future of Health Care in the Philippines

The government aims to improve the health care system through the Universal Health Care Act. This law aims to provide all Filipinos with access to quality health care. It’s a big step towards better health care in the Philippines.

250 Words Essay on Health Care System In The Philippines

Introduction.

The health care system in the Philippines is a mix of public and private providers. It aims to give medical help to all its citizens. The Department of Health (DOH) is the main body in charge of health care.

The government provides health care through public hospitals and clinics. These are usually free or cost very little. The Philippine Health Insurance Corporation (PhilHealth) is the national health insurance program. It helps people pay for medical services.

There are also private hospitals and clinics. These usually offer better facilities and shorter waiting times. But, they are more expensive. Many people have private health insurance to help cover these costs.

The health care system in the Philippines faces some issues. There are not enough doctors and nurses, especially in rural areas. Also, the quality of care can vary greatly. Some people can’t afford the cost of private health care but need it due to the lack of public facilities.

Improvements

The government is working to improve the health care system. One step is the Universal Health Care Act. This law aims to give all Filipinos access to quality health care, without causing financial hardship.

In conclusion, the health care system in the Philippines is a mix of public and private providers. It faces some challenges, but efforts are being made to improve it. Everyone in the Philippines deserves access to good health care.

500 Words Essay on Health Care System In The Philippines

The basics of the health care system in the philippines.

The health care system in the Philippines is a mix of public and private providers. The Department of Health (DOH) is the main public health agency. It sets policies, plans, and programs for health services. It also runs special health programs and research.

The Philippine Health Insurance Corporation (PhilHealth) is another important part of the public health system. It provides health insurance for Filipinos. This helps to make health care more affordable.

Public and Private Health Providers

There are both public and private health care providers in the Philippines. Public providers include hospitals, clinics, and health centers run by the government. These offer free or low-cost services. But sometimes, they may not have enough resources or staff.

Private providers include doctors, clinics, and hospitals that are not run by the government. They usually offer more services and shorter waiting times. But, their services cost more.

Health Care Challenges

The health care system in the Philippines faces several challenges. One is the uneven distribution of health services. More health services are available in urban areas than in rural areas. This means people living in rural areas may have to travel far to get health care.

Another challenge is the cost of health care. Even though PhilHealth helps, many Filipinos still find health care expensive. Some may not be able to afford the medicines or treatments they need.

Efforts to Improve Health Care

The government is working to improve the health care system. In 2019, it passed the Universal Health Care Law. This law aims to give all Filipinos access to quality health care. It also aims to make health care more affordable.

The government is also investing in health technology. This includes telemedicine, which allows people to consult with doctors online. This can help people in rural areas get health care more easily.

The health care system in the Philippines is a mix of public and private providers. It faces challenges like uneven distribution of services and high costs. But, the government is taking steps to improve it. It is working to provide universal health care and make health care more affordable. It is also investing in health technology to reach more people. Despite the challenges, the future of health care in the Philippines looks hopeful.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Health Care Issues

- Essay on Health Care In India

- Essay on Health And Hygiene

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

RECONSTRUCTING THE FUNCTIONS OF THE GOVERNMENT: THE CASE OF PRIMARY HEALTH CARE IN THE PHILIPPINES: A LITERATURE REVIEW

Related Papers

dhuss mania

Philippine Political Science Journal

Maria Ela Atienza

This paper analyzes the dynamics of health devolution in the Philippines within the context of the 1991 Local Government Code. The paper looks into how the present level of health devolution came about, the reform's impact on the public health system, and the factors involved in improving health service delivery in municipalities under a devolved set up. There are several variables that are tested as possible intervening variables. These are prioritization of health services in resource allocation and management, adequacy of formal health personnel and facilities, and citizens' participation in health service delivery. The sociopolitical context of the local government is also explored. Two case studies are presented to support the arguments of the paper.

Janet Cuenca

The study attempts to document the Philippine’s experience in health devolution with focus on the Department of Health’s efforts to make it work. It also aims to draw lessons and insights that are critical in assessing the country’s decentralization policies and also, in informing future policymaking. In particular, it highlights the importance of (i) a well-planned and well-designed government policy to minimize, if not avert, unintended consequences; and (ii) mainstreaming of health policy reforms to ensure sustainability. It suggests the need to (i) take a closer look at the experience of local government units (LGUs) that were able to reap the benefits of health devolution and find out how the good practices can be replicated in other LGUs; and (ii) review and assess the various health reforms and mechanisms that have been in place to draw lessons and insights that are useful for crafting future health policies.

Jaap de Visser

Harry Santos

RATIONALE The main obstacles to attaining universal health care are the following: 1) The two national healthcare financing mechanisms of direct govemment subsidy through DOH and LGU budgets, and the National Health Insurance Program (NHIP) have not been able to adequately provide financial risk protection for the poor; 2) As a result, poor households have inadequate access to quality outpatient and inpatient care from health care facilities. Rural Health Units (RHUs) and City Health Units in municipalities and cities, district and provincial hospitals, and even DOH-retained regional hospitals and medical centers do not have the necessary provisions to meet the needs of poor families; and 3) Owing to the failure of the financing and health care delivery systems to address the needs of poor Filipinos, it is unlikely that the Philippines will meet its MDG commitments by 2015. This is especially problematic for our targets to reduce maternal and infant mortality. Administrative Order No. 2010-0036 entitled, "The Aquino Health Agenda: Achieving Universal Health Care for All Filipinos" provided for three strategic thrusts to achieve universal health care or Kalusugan Pangkalahatan (Y-P):1) Rapid expansion in NHIP enrollment and benefit delivery using national subsidies for the poorest families; 2) Improved access to quality hospitals and health care facilities through accelerated upgrading of public health facilities; and 3) Attainment of the health-related MDGs by applying additional effort and resources in localities with high concentration of families who are unable to receive critical public health services. Implementation of KP will also involve aligning the DOH budget behind these aforementioned three strategic thrusts. Furthermore, KP execution shall use well-defined and area-specific deliverables as performance targets to be pursued by DOH managers within a set timeframe and with clearly defined accountabilities. OBJECTIVE This Order provides for guidelines and management arrangements to implement Kalusugan Pangkalahatanby accelerating the accomplishment of specif,rc performance targets. This is intended to streamline the tasks and functions of central office units to provide critical supporl and assistance to field units, who in turn shall be better supervised by Operations ClusterAssistant Secretaries andlor Building I,

Public Administration and Development

Patrick Vaughan

Abigail Gandol

Jesselle Manrique

Jonathan Yambao

Sarbani Chakraborty

RELATED PAPERS

Jasa saluran Mampet jakarta

Luoping Zhang

Juliane Griebeler

liana goletiani

Media Konservasi

dewi Prawiradilaga

Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board

MECIT CETIN

Fábio Nogueira

Victor S . GONÇALVES

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Computer Speech & Language

Development

Tushar Desai

Joao Miranda de Lima

SUSTAINABLE: Jurnal Kajian Mutu Pendidikan

Titi Candra Sunarti

JMIR Public Health and Surveillance

Vania Martínez

Journal of Medical Science And clinical Research

shivani gandhi

International Journal of Behavioral Consultation and Therapy

Larry Beutler

Jurnal Teknik ITS

Daniel Siahaan

Đỗ Phương Nam

Machrus Ali

Courtney Shelley

DANIELLE HERSHEYS ESPELITA

Journal of Dairy Science

Christian Gamborg

Remote Sensing

STEVEN ARTHUR LOISELLE

Smart Grid and Renewable Energy

Vilas Bugade

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Our Covid-19 Response

- Our Projects

- Our Clients

Dodoma 13 April 2024

Jakarta 13 april 2024, hanoi 13 april 2024, amman 13 april 2024, nairobi 13 april 2024, port-au-prince 13 april 2024, monrovia 13 april 2024, cairo 13 april 2024, lusaka 13 april 2024, maputo 13 april 2024, dar es salaam 13 april 2024, antananarivo 13 april 2024, karachi 13 april 2024, dhaka 13 april 2024, manila 13 april 2024.

View all projects

Strengthening primary health care provision in the philippines.

With support from the WHO, ThinkWell conducted a study to develop a primary care competency certification framework and a corresponding tool to certify primary care health workers. As part of the study, we mapped the current state of primary care delivery in the Philippines, developed options for primary care provider models for the Philippines based on global best practices, created and piloted primary care provider competency assessment tools, and designed a primary care provider certification framework. Our study helped ensure that the Department of Health is prepared to certify primary care providers to deliver services in primary care facilities, as mandated under the country’s Universal Health Care (UHC) Law.

Breaking New Ground

Our work consolidated and aligned initiatives that the Health Human Resource Development Bureau of the Philippine Department of Health has led to clarify and re-shape the traditional roles of health care workers in front-line health facilities, particularly in the public sector. More importantly, this work paved the way to ensure that primary health care services be prioritized and institutionalized.

ThinkWell helped to ensure that when the UHC Law was implemented in 2020, the Philippines had a certification tool to help identify and certify primary care providers who are equipped to deliver an expanded primary care benefit package for all Filipinos.

ThinkWell reviewed existing studies and documents that articulate important health care worker competencies. Our work aligned with the goal for primary health care services in the Philippines to be high-quality, efficient, and accessible to all.

Our research uncovered primary care delivery models that are potentially applicable in various settings in the Philippines. In addition, we identified and validated essential competencies for primary care health workers. Finally, we proposed a certification framework and tool that was pilot tested in selected primary care facilities. For a summary of the rationale and proposed design of the certification process of primary care providers, please visit the SP4PHC Philippines page .

Related reports

Primary health care in the Philippines: banking on the barangays?

111 citations

70 citations

68 citations

61 citations

33 citations

View 1 citation excerpt

Cites background from "Primary health care in the Philippi..."

... A decade before healthcare devolution, the country implemented a primary healthcare policy which created a large cadre of community-based health workers locally called barangay (village) health workers (BHW).(15) Organisationally, the BHW fall under the governance of the barangay and are selected to work in their respective areas of residence; functionally, they are under the local government health unit (LGHU). ...

430 citations

82 citations

38 citations

28 citations

Related Papers (5)

Trending questions (3).

The healthcare system in the Philippines includes primary health care with a focus on community participation and intersectoral cooperation.

The paper does not provide specific information about the services offered at barangay health centers in the Philippines.

As a result, the Philippines strategy may be said to be "banking on the barangays."

Ask Copilot

Related papers

Contributing institutions

Related topics

- Open access

- Published: 03 November 2023

The impact of eHealth on relationships and trust in primary care: a review of reviews

- Meena Ramachandran ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4670-5375 1 , 2 ,

- Christopher Brinton 1 , 3 ,

- David Wiljer ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2748-2658 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ,

- Ross Upshur ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1128-0557 1 , 8 &

- Carolyn Steele Gray 1 , 6

BMC Primary Care volume 24 , Article number: 228 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

1622 Accesses

10 Altmetric

Metrics details

Given the increasing integration of digital health technologies in team-based primary care, this review aimed at understanding the impact of eHealth on patient-provider and provider-provider relationships.

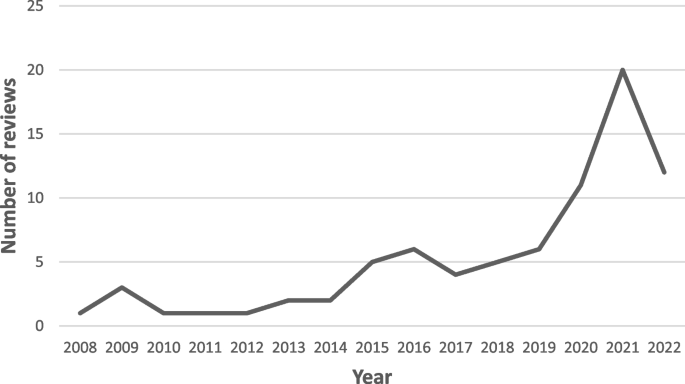

A review of reviews was conducted on three databases to identify papers published in English from 2008 onwards. The impact of different types of eHealth on relationships and trust and the factors influencing the impact were thematically analyzed.

A total of 79 reviews were included. Patient-provider relationships were discussed more frequently as compared to provider-provider relationships. Communication systems like telemedicine were the most discussed type of technology. eHealth was found to have both positive and negative impacts on relationships and/or trust. This impact was influenced by a range of patient-related, provider-related, technology-related, and organizational factors, such as patient sociodemographics, provider communication skills, technology design, and organizational technology implementation, respectively.

Conclusions

Recommendations are provided for effective and equitable technology selection, application, and training to optimize the impact of eHealth on relationships and trust. The review findings can inform providers’ and policymakers’ decision-making around the use of eHealth in primary care delivery to facilitate relationship-building.

Peer Review reports

Primary care is a person’s first point of contact in healthcare systems and includes “disease prevention, health promotion, population health, and community development” ([ 1 , 2 ] p1). Primary care across the globe is shifting towards team-based models that bring together interprofessional teams of family physicians, nurse practitioners, registered nurses, social workers, dietitians, and other professionals to provide holistic and comprehensive care [ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ]. These models are designed to address the needs of individuals with multimorbidity and complex conditions in the community as they can offer a diverse skill set to meet the variable needs of this population [ 7 ]. Along with an evolution towards team-based primary care models, this past decade has also witnessed an increasing global interest and rapid uptake of digital health in primary care [ 8 , 9 , 10 ], hastened by the COVID-19 pandemic [ 11 , 12 ]. Some jurisdictions are considering a “digital-first” primary care model where technology is used as the default care delivery mechanism [ 13 ], while others have noted a need to balance appropriate and equitable hybrid care delivery [ 10 ].

Digital health broadly refers to the use of technologies for health [ 14 ]. Technologies include information and communication technology (also referred to as eHealth), which includes the use of mobile wireless technologies (often referred to as mHealth as a specific type of eHealth) [ 14 ]. Digital health technologies can also include emerging technologies, processes, and platforms like big data, genomics, machine learning, and artificial intelligence [ 14 ]. eHealth includes: (i) management systems; (ii) communication systems; (iii) computerised decision support systems; and (iv) information systems [ 15 ]. The implementation and effectiveness of eHealth is influenced by a complex array of factors and can impact several facets of care delivery [ 16 ].

One aspect that can potentially be altered is the nature of relationships and trust between patients and their providers, and within provider teams. Relationships between patients and providers, built on trust, knowledge, regard, and loyalty, have been demonstrated to be fundamental to healthcare delivery [ 17 ]. This is particularly important in primary care where patients will tend to have longer-term relationships with their provider or practice [ 18 ]. Strong trust-based relationships between providers within teams can enable a positive work environment, improved communication, effective teamwork, and care coordination [ 19 , 20 ].

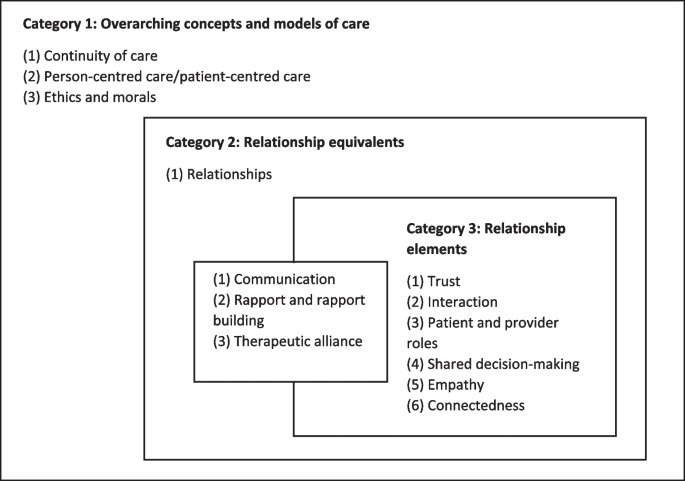

eHealth and patient-provider relationships

Patient-provider relationships are often referred to using terms like therapeutic relationship, therapeutic alliance, communication, interaction, and rapport [ 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 ]. Trust is thought to be an important component of this relationship [ 28 ] and its development has been found to require multiple interactions over time [ 29 ]. Promoting trust in the patient-provider relationship includes the demonstration of three key provider attributes: interpersonal and technical competence, moral comportment, and vigilance [ 30 ]. Patients perceive trust in providers as linked to their active participation and satisfaction with care [ 31 , 32 ]. An absence of trust in providers is associated with reductions in treatment adherence and care seeking behaviours by patients, and reduced continuity of care [ 33 ] (i.e., connected and coordinated care while moving through the healthcare system) [ 34 ].

Trust-based patient-provider relationships are changing with the expansion of eHealth. Henson et al. use the term ‘digital therapeutic alliance’ to refer to patient-provider relationships established through mental health apps [ 35 ]. The interconnection between technology and therapeutic relationships is evident in Mesko and Győrffy’s ([ 36 ] p2) definition of digital health as “the cultural transformation of how disruptive technologies that provide digital and objective data accessible to both health care providers and patients leads to an equal-level doctor-patient relationship with shared decision-making and the democratization of care”. Studies have reported positive changes accompanying this transformation. Patients may experience greater empowerment through improved access to health information and resources and can assume a more active role in communication and decision-making [ 36 , 37 , 38 ]. Providers may experience shifts towards empathy-driven care [ 39 ], assume the role of a guide to direct patients towards high-quality information and services [ 36 ], and support active patient engagement with technology [ 40 ]. Some providers value the use of technology for prioritizing patient values, enabling patient autonomy [ 41 ], and making caregivers part of the team [ 42 ].

However, the impact of technology on relationships has also been termed “a double-edged sword” with significant ethical and safety implications [ 38 ]. Technology is thought to harm the relationship and reduce efficiency if patients obtain irrelevant information or misinterpret information [ 37 , 38 ]. ( For instance, patients may misinterpret data or test results accessed through technology such as self-monitoring devices and smartphone apps when the provider’s involvement is limited) [ 37 ]. Patients may also access information through resources on the Internet that may enable them in engage actively in dialogue with the provider but may also lead to them obtaining irrelevant or inaccurate information. Some providers have expressed concerns related to overuse of technology by patients and caregivers (e.g., frequently checking blood sugar or pressure when deemed unnecessary by the provider) [ 42 ] and technology taking their attention away from patients during the clinical encounter [ 41 ].

eHealth and provider-provider relationships

Relationships between primary care providers that “provide support and sustenance” are among the key factors for compassion among healthcare workers ([ 43 ] p123). Like the case of patient-provider relationships, trust is integral to strong team relationships and can contribute to better quality of care and practice improvement through open discussions of successes and failures among team members [ 23 ]. In an increasingly virtual care delivery environment, trust-based relationships between providers can facilitate interprofessional collaboration [ 44 ]. Interpersonal trust has been identified as a primary determinant of performance in virtual relationships between telemedicine providers [ 45 ]. A lack of trust between telehealth nurses and other primary care professionals was found to create tensions in their relationships [ 37 ]. The use of health information technology can enhance trust between providers when it facilitates reviewing and affirming non-physician clinicians’ decisions or erode trust when it limits opportunities for developing familiarity and comfort [ 25 ].

Objectives and approach

While there is a growing body of literature on the impact of eHealth on patient-provider and provider-provider relationships and trust in primary care, questions remain around how to best integrate eHealth into primary health care systems to facilitate relationship-centred care and uphold the “humanness” of primary care [ 46 ]. There is a need to examine this issue to generate specific information that can inform decision- and policymaking around the integration and implementation of eHealth into primary care while considering its impact on relationships and trust.

This paper reports on a review of reviews [ 47 ] to synthesise high-level evidence on relationships and trust as related to the use of eHealth in primary care. This approach was selected to identify what is currently known and unknown in this field by summarizing evidence from the large number of existing evidence syntheses, and to generate recommendations on how to ensure eHealth adoption permits and strengthens relationships and trust in primary care. To guide the review, we sought to answer the research question: How does eHealth impact patient-provider and provider-provider relationships and trust in primary care? Given the importance of health equity, especially in relation to the use of digital health in primary care [ 48 ], we also sought to understand if eHealth has a differential impact on trust and relationships across different groups (e.g., sociodemographic groups).

Search strategy

The search strategy was developed for Medline and adapted to EMBASE and Cochrane databases (Additional file 1 ). Four concepts were included: ‘ primary care’, ‘digital health technologies’, ‘relationships’, and ‘ trust’. Strategies developed for previous reviews with a librarian’s assistance helped build the search for ‘ primary care’ and ‘digital health technologies’ . A strategy was developed for the other two concepts (i.e., ‘relationships’ and ‘trust’ ) using subject headings and non-indexed keywords identified through team brainstorming and literature scans. The initial search was conducted in May 2021, followed by an updated search using the same strategy in June 2022.

Inclusion criteria and study selection

The search focused on peer-reviewed evidence syntheses published in English from 2008 onwards. This timeline was determined based on trends noted in two reviews on digital health in primary care that indicated that most papers were published after 2008 [ 49 , 50 ]. Included reviews (i) were located in a primary care setting, either exclusively or along with other settings (ii) discussed patient-provider and/or provider-provider relationships and/or trust, and (iii) included the use of digital health/eHealth/mHealth technologies (as defined above, and as consistent with our search criteria listed in search lines 10–25 in Additional file 1 ) allowing for interaction or information-sharing between patients and providers and/or between providers. As the focus of the review was on adult patients receiving primary care services, reviews exclusively discussing patients below 18 years of age were excluded. Primary empirical studies, conference abstracts, editorials and grey literature were also excluded.

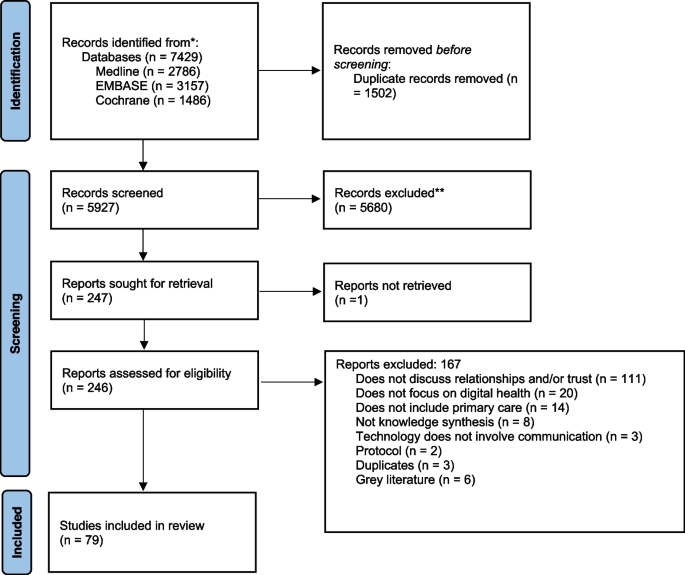

The search results were validated using five articles chosen by the research team that met the inclusion criteria. Articles were then uploaded to EndNote reference manager to remove duplicates, and then transferred to Covidence review management platform for screening. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram (Fig. 1 ) depicts the study selection process. Text screening followed two phases: 1) title and abstract and 2) full text.

Title and abstract screening: Two rounds of title and abstract screening tests between three team members were conducted to ensure agreement and alignment with the inclusion criteria at this stage. All three members screened a random sample of 100 titles and abstracts to check if they met the inclusion criteria. Cohen’s Kappa values [ 51 , 52 ] were calculated between pairs of reviewers (e.g. Rev 1-Rev2; Rev 2-Rev3; Rev 1- Rev3) resulting in Kappa values ranging from 0.496 to 0.754, suggesting moderate to substantial agreement by the second round. Team meetings were held to discuss conflicts, and after the second round it was determined that all three reviewers had come to a common understanding of the inclusion/exclusion criteria to proceed with a single-reviewer approach.

Full-text screening: At the stage of full-text screening a single-reviewer approach was deemed sufficient due to clear understanding of inclusion and exclusion criteria established by the reviewers, and due to time and resource constraints..

PRISMA chart

Data extraction and synthesis

Three members of the research team conducted data extraction. A data extraction sheet was developed for this study and piloted on three articles. It included: type of review; number of studies; research paradigm of authors (e.g., postpositivist, constructionist); study aims; participants; settings; type(s) of technology; definitions of relationships and trust and/or connected terms; factors influencing impact of eHealth on relationships and/or trust; and any discussions around equity (how this impact might differ in different groups).