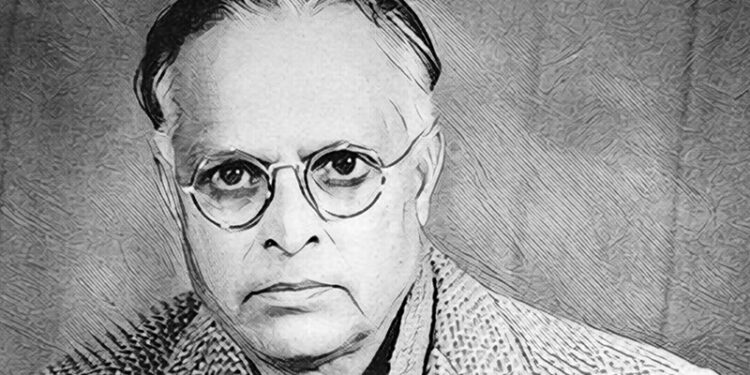

R. K. Narayan

R. k. narayan’s biography, early writing, first novel.

For instance, it was the first work in which Narayan set his story in the fictive town of Malgudi.

Local paper

Publication of first novel, narayan’s rising success.

After the first book, Greene began to counsel Narayan about how to write to gain the attention of the English audience. He also advised him to shorten his name according to the demand of English readers.

Effect of Depression

Busy career, beginning of mythological career, end of career.

Furthermore, in 1980, Narayan became a part of the Indian parliament and served in education for 6 years. From this time till death, he wrote abundantly. His final book was “Grandmother’s Tale”, a novella based upon Narayan’s childhood recollection of his grandmother’s tale about his great-grandmother.

R. K. Narayan’s Writing Style

Natural and unpretentious, compassionate representations, depiction of true indian society, short stories style, descriptive and objective style.

This gives the narrative a realistic and genuine representation. His work has a unique capability to intertwine actions and characters through his attitude towards the ways of life.

Themes in R. K. Narayan’s Writings

Misery and suffering of man, animal sympathy.

In his works, Narayan exhibits the intricacies of animal life and shows his understanding of their emotions in beautifully created stories.

Children Innocence and Mischiefs

Unemployment issues.

This condition can be related to most of the modern men in the growing competitive world.

Achievements

Works of r. k. narayan.

R. K. Narayan Biography

Birthday: October 10 , 1906 ( Libra )

Born In: Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

R. K. Narayan is considered as one of leading figures of early Indian literature in English. He is the one who made India accessible to the people in foreign countries—he gave unfamiliar people a window to peep into Indian culture and sensibilities. His simple and modest writing style is often compared to that of the great American author William Faulkner. Narayan came from a humble south Indian background where he was consistently encouraged to involve himself into literature. Which is why, after finishing his graduation, he decided to stay at home and write. His work involves novels like: ‘The Guide’, ‘The Financial Man’, ‘Mr. Sampath’, ‘The Dark Room’, ‘The English Teacher’, ‘A Tiger for Malgudi’, etc. Although Narayan’s contribution to the Indian literature is beyond description and the way he grabbed foreign audience’s attention for Indian literature is commendable too but he will always be remembered for the invention of Malgudi, a semi-urban fictional town in southern India where most of his stories were set. Narayan won numerous accolades for his literary work: Sahitya Akademi Award, Padma Bhushan, AC Benson Medal by the Royal Society of Literature, honorary membership of the American Academy of Arts and Literature, Padma Vibhushan, etc.

Recommended For You

Indian Celebrities Born In October

Also Known As: Rasipuram Krishnaswami Iyer Narayanaswami

Died At Age: 94

Born Country: India

Quotes By R. K. Narayan Novelists

Died on: May 13 , 2001

place of death: Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

Notable Alumni: Maharaja's College, Mysore

City: Chennai, India

education: Maharaja's College, Mysore

awards: Sahitya Akademi Award (1958) Padma Bhushan (1964) AC Benson Medal by the British Royal Society of Literature (1980) Padma Vibhushan (2001)

You wanted to know

What are some key themes in r. k. narayan's works.

Some key themes in R. K. Narayan's works include the clash between tradition and modernity, the complexities of human relationships, the struggles of ordinary individuals in a changing society, and the significance of everyday life and experiences.

What is the significance of Malgudi in R. K. Narayan's writings?

Malgudi serves as a fictional town created by R. K. Narayan as the setting for many of his novels and short stories. It represents a microcosm of Indian society, allowing Narayan to explore universal themes through the lives of its diverse inhabitants.

How did R. K. Narayan's writing style contribute to the popularity of his works?

R. K. Narayan's writing style, characterized by its simplicity, humor, and vivid portrayal of everyday life, resonated with readers from various backgrounds. His storytelling ability and authentic depiction of Indian culture drew widespread acclaim and contributed to the enduring popularity of his works.

What role did humor play in R. K. Narayan's storytelling?

Humor was a significant element in R. K. Narayan's storytelling, often used to highlight the idiosyncrasies of human behavior and society. His witty observations and satirical tone added depth to his narratives, making his works both entertaining and thought-provoking.

How did R. K. Narayan contribute to the development of Indian literature in English?

R. K. Narayan is regarded as a pioneering figure in Indian literature in English for his authentic portrayal of Indian life and culture. By capturing the nuances of everyday experiences and the complexities of human relationships, he helped establish a distinct voice for Indian writers in the global literary landscape.

Recommended Lists:

Narayan was known for his simple and unassuming lifestyle, often wearing a traditional Indian dhoti and kurta.

Despite being a prolific writer, Narayan did not have a formal education in literature or creative writing. He learned English on his own and started writing stories at a young age.

Narayan was a keen observer of human behavior and often drew inspiration for his characters and stories from the people he encountered in his hometown of Malgudi.

He had a great sense of humor and often infused his writing with wit and satire, making his stories both engaging and thought-provoking.

Narayan was a disciplined writer, following a strict routine of writing every morning and revising his work in the afternoons. This dedication to his craft contributed to his success as a renowned author.

Quotes By R. K. Narayan | Quote Of The Day | Top 100 Quotes

See the events in life of R. K. Narayan in Chronological Order

How To Cite

People Also Viewed

Also Listed In

© Famous People All Rights Reserved

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

R.K. Narayan

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- MapsofIndia.com - R. K. Narayan

- IndiaNetzone - R K Narayan

- International Journal of Creative Research Thoughts - Cultural And Social Ethos Depicted In The Novels of R.K. Narayan

- Indian Writing In English - Biography of R.K. Narayan

- R.K. Narayan - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

R.K. Narayan (born October 10, 1906, Madras [Chennai], India—died May 13, 2001, Madras) was one of the finest Indian authors of his generation writing in English.

Reared by his grandmother, Narayan completed his education in 1930 and briefly worked as a teacher before deciding to devote himself to writing. His first novel , Swami and Friends (1935), is an episodic narrative recounting the adventures of a group of schoolboys. That book and much of Narayan’s later works are set in the fictitious South Indian town of Malgudi. Narayan typically portrays the peculiarities of human relationships and the ironies of Indian daily life, in which modern urban existence clashes with ancient tradition. His style is graceful, marked by genial humour, elegance, and simplicity.

Among the best-received of Narayan’s 34 novels are The English Teacher (1945), Waiting for the Mahatma (1955), The Guide (1958), The Man-Eater of Malgudi (1961), The Vendor of Sweets (1967), and A Tiger for Malgudi (1983). Narayan also wrote a number of short stories; collections include Lawley Road (1956), A Horse and Two Goats and Other Stories (1970), Under the Banyan Tree and Other Stories (1985), and The Grandmother’s Tale (1993). In addition to works of nonfiction (chiefly memoirs), he also published shortened modern prose versions of two Indian epics, The Ramayana (1972) and The Mahabharata (1978).

Talk to our experts

1800-120-456-456

- R K Narayan Biography

Biography of R K Narayan

Rasipuram Krishnaswami Iyer Narayanaswami (RK Narayan) was a well-known Indian writer famous for his set of work and writing in the fictional South Indian town of Malgudi. He was one of the leading and famous authors of early Indian literature written in English along with two others, Mulk Raj Anand and Raja Rao.

Narayan's greatest achievement was to make India accessible to the outside world through his writing and powerful words in his literature. Narayan's biography is always centered on his friendship with Graham Greene. Because he was Narayan's mentor and close friend. He was actively involved in identifying and getting publishers for Narayan's first four books.

In 1941, he founded his own publishing house and his works quickly found a permanent and favorite place in the bookshelves of almost all the Indian homes. When he was at the peak of his fame in his successful career, Narayan was then awarded a Padma Bhushan in 1964 and 36 years later, just a year before his death at 94, another prestigious Padma Vibhushan award in 2000. Narayan was critically ill and hospitalized with cardiovascular problems two weeks ago in Madras, the capital of the southern state of Tamil Nadu, where he was born in 1906.

Early Life

Narayan was born in 1906 in Madras (now renamed and known as Chennai, Tamil Nadu), British India into a normal Hindu family. He was one of eight children his parents have had and Narayan was second among the sons; his younger brother Ramachandran was an editor at Gemini Studios, and the youngest brother Laxman was a successful cartoonist.

Narayan spent the early years of his life in Madras in the care of his grandmother and a maternal uncle and joined his parents mainly only during the vacations. At that time, India was still treated as the most important of the British empire, a colony held since 1857.

RK Narayan attended a number of schools than a usual student would as in Madras while living with his grandmother, in which the main school was the Lutheran Mission School in Purasawalkam, C.R.C. High School, and Christian College High School. Narayan was an ardent and passionate reader who grew up reading Dickens, Wodehouse, Arthur Conan Doyle, and Thomas Hardy.

After completing high school, Narayan failed the university entrance examination unfortunately but got to have lots of time to spend a year at home reading and writing; and then he successfully passed the final examination in 1926 and joined Maharaja College of Mysore.

RK Narayan was always found devoted and dedicated to reading whenever he got time.

Awards and Honors

Among the best works of RK Narayan among his 34 novels, The English Teacher (1945), Waiting for the Mahatma (1955), The Guide (1958), The Man-Eater of Malgudi (1961), The Vendor of Sweets (1967), and A Tiger for Malgudi (1983) were the best.

His novel The Guide (1958) won him the most prestigious National Prize of the Indian Literary Academy, which was his country's highest honor. Narayan received many other awards and honors including the AC Benson Medal from the Royal Society of Literature, the Padma Vibhushan, and the Padma Bhushan, India's second and third highest civilian awards, and in 1994 the Sahitya Akademi Fellowship, the highest honor of India's national academy of letters. He was also once nominated to the Rajya Sabha, which is the upper house of India's parliament.

To know more about RK Narayanan, log into Vedantu and find out what the experts have to say about this legend. His creations have made him an immortal figure in Indian literature that every booklover, irrespective of age, admires.

FAQs on R K Narayan Biography

1. Who is RK Narayan?

RK Narayan was one of the most important English-language Indian fiction authors. He is widely regarded as one of India's best novelists. He created a realistic and immersive experience for his audience by bringing small-town India to them.

2. When and Where Was RK Narayan Born?

RK Narayan was born on 10 October 1906 in Madras (Chennai), Tamil Nadu, India into an Iyer Vadama Brahmin family.

3. Which Was the First Book Published by RK Narayan?

Swami and Friends was RK Narayan's first book, published in 1930. The novel was based on several incidents from his own childhood and was semi-autobiographical. It is still one of the most recommended English readers in Indian schools.

4. What is the difference between Biography and Autobiography?

A biography is often written on account of a person's whole life, which will be framed and written by someone else. On the other hand, an autobiography is also written on account of a person's life but will be written by that person himself from his own point of view. Vedantu's website has been designed to help you find both biographical and autobiographical information in many different formats through online libraries. You can refer to the material and learn about all the great people who have marked their names in history with the help of Vedantu at the comfort of your home.

5. What are the types of Biography?

There are four classic and informative types of biographies they are historical fiction, academic, fictional academic, and prophetic biography. A historical fiction type of biography is a creative account inspired by the events of a person’s life. Academic biographies are based on documented facts and noted accomplishments of a person’s life. A fictional academic biography often tries to combine the best and interesting elements of the fictional biography (entertainment with a strong theme and storyline) and the academic biography (with factual accuracy as well). And a prophetic biography begins with retelling the regular academic approach of considering all the known facts which have been already framed.

6. Why is reading a biography really important?

Biographies help us gain insight and deep knowledge into how successful people handle crises and solve complex problems in their times. They will gradually invite us into people's lives, allowing us to observe them as they battle with challenges and make important decisions at right time. This ultimately helps the reader to greater understanding and better decision making in their own lives. Not all individuals are the same everyone has their own experience and knowledge but biographies of great people who have achieved a lot can always guide you on the right path.

7. How do students benefit from reading biographies?

Biographies help students understand the history and life experiences through another person's perspective, which may encourage them to ask more questions and learn even more. Biographies often serve as a starting point for learning more about a passion at an early age which helps them in choosing their career. Basically, while reading a biography or an autobiography, you get to learn about what an individual has been through, and more often their life experiences at every stage. Since it is believed that human life and psychology are in similarity you can easily relate with those individuals and put yourself in their shoes to understand the experience better.

8. Does reading History help us in our daily life?

Knowing the past is extremely important for any society and human being to know what has happened in their past and which person has invented or created memorable and historic moments. Past gives us insights into our evolving behavior and basic character in matters of life, love, mutuality, war, diplomacy, and peace. It provides insights in-depth understanding into the processes and events of the past and interconnects them with our current life. History serves as a Warning to avoid any mistakes that have been done in the past and gives us a second chance to live our lives even better in our present.

R. K. Narayan Biography

R. K. Narayan, a prominent figure in early Indian literature in English, is renowned for his ability to make Indian culture and sensibilities accessible to foreign audiences. With a writing style often compared to that of William Faulkner, Narayan’s humble background and passion for literature led him to stay at home and write after completing his education. His notable works include novels such as ‘The Guide’, ‘The Financial Man’, and ‘The English Teacher’. However, Narayan’s most enduring legacy lies in the creation of Malgudi, a semi-urban fictional town in southern India that served as the backdrop for many of his stories. His contributions to Indian literature have earned him numerous accolades, including the Sahitya Akademi Award and Padma Vibhushan.

Quick Facts

- Indian Celebrities Born In October Also Known As: Rasipuram Krishnaswami Iyer Narayanaswami

- Died At Age: 94

- Born Country: India

- Quotes By R. K. Narayan

- Died on: May 13, 2001

- Place of death: Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

- Notable Alumni: Maharaja’s College, Mysore

- City: Chennai, India

- Education: Maharaja’s College, Mysore

- Awards: Sahitya Akademi Award (1958) Padma Bhushan (1964) AC Benson Medal by the British Royal Society of Literature (1980) Padma Vibhushan (2001)

Childhood & Early Life

R. K. Narayan was born in Chennai, Indian in 1906 in a working class south Indian family. His father was a school headmaster and because his father had to be frequently transferred for his job, Narayan spent most of his childhood in the loving care of his grandmother, Parvati. It was his grandmother who taught him arithmetic, mythology and Sanskrit. He also attended many different schools in Chennai like, Lutheran Mission School, Christian College High School, etc. He was interested in English literature since he was very young. His reading habit further developed when he moved to Mysore with his family and there his father’s schools library offered him gems of writing from authors like Dickens, Thomas Hardy, Wodehouse, etc. In 1926, he passed the university examination and joined Maharaja College of Mysore. After completing his graduation, Narayan took a job as a school teacher in a local school. Soon after, he realized that he could only be happy in writing fiction, which is why he decided to stay at home and write.

Narayan’s decision of staying at home and writing was supported in every way by his family and in 1930, he wrote his first novel called ‘Swami and Friends’ which was rejected by a lot of publishers. But this book was important in the sense that it was with this that he created the fictional town of Malgudi. After getting married in 1933, Narayan became a reporter for a newspaper called ‘The Justice’ and in the meantime, he sent the manuscript of ‘Swami and Friends’ to his friend at Oxford who in turn showed it to Graham Greene. Greene got the book published. His second novel, ‘The Bachelors of Arts’, was published in 1937,. It was based on his experiences at college. This book was again published by Graham Greene who by now started counseling Narayan on how to write and what to write about to target the English speaking audience. In 1938, Narayan wrote his third novel called ‘The Dark Room’ dealt with the subject of emotional abuse within a marriage and it was warmly received, both by readers and critics. The same year his father expired and he had to accept regular commission by the government. In 1939, his wife’s unfortunate demise left Narayan depressed and disgruntled. But he continued to write and came out with his fourth book called ‘The English Teacher’ which was more autobiographical than any of his prior novels. After this, Narayan authored books like, ‘Mr. Sampath’ (1949), ‘The Financial Expert’ (1951) and ‘Waiting for the Mahatma (1955)’, etc. He wrote ‘The Guide’ in 1956 while he was touring United States. It earned him the Sahitya Akademi Award. In 1961, he wrote his next novel called ‘The Man-Eater of Malgudi’. After finishing this book, he travelled to the United States and Australia. He also gave lectures on Indian literature in Sydney and Melbourne. With his growing success, he also started writing columns for The Hindu and The Atlantic. His first mythological work ‘Gods, Demons and Others’, a collection of short stories was published in 1964. His book was illustrated by his younger brother R. K. Laxman, who was a famous cartoonist. In 1967, he came up with his next novel titled ‘The Vendor of Sweets’. Later, that year Narayan travelled to England, where he received the first of his honorary doctorates from the University of Leeds. Within next few years he started translating Kamba Ramayanam to English—a promise he made to his dying uncle once. Narayan was asked by the government of Karnataka to write a book to promote tourism which he republished in 1980 with the title of ‘The Emerald Route’. In the same year he was named as the honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. In 1980, Narayan was chosen as the member of Rajya Sabha, the upper house of the Indian Parliament and throughout his 6 years term he focused on the education system and how little children suffer in it. During the 1980s Narayan wrote prolifically. His works during this peiod include: ‘Malgudi Days’ (1982), ‘Under the Banyan Tree and Other Stories’, ‘A Tiger for Malgudi’ (1983), ‘Talkative Man’ (1986) and ‘A Writer’s Nightmare’ (1987). In 1990s, his published works include: ‘The World of Nagaraj (1990)’, ‘Grandmother’s Tale (1992)’, ‘The Grandmother’s Tale and Other Stories (1994)’, etc.

Personal Life & Legacy

In 1933, Narayan met his future wife Rajam, a 15 year old girl, and fell deeply in love with her. They managed to get married despite many astrological and financial hurdles. Rajam died of typhoid in 1939 and left a three year old daughter for Narayan to take care of. Her death caused a great shock in his life and he was left depressed and uprooted for a long period of time. He never remarried in his life. Narayan died in 2001 at the age of 94. He was planning on writing his next novel, a story on a grandfather, just before he expired.

- He was very fond of the publisher of The Hindu, N. Ram, and used to spend all his time, towards the end of his life, conversing with him over coffee.

- Narayan is regarded as one of the three leading English language Indian fiction writers, along with Raja Rao and Mulk Raj Anand.

Awards & Achievements

Narayan won numerous accolades for his literary works. These include: Sahitya Akademi Award (1958), Padma Bhushan (1964), AC Benson Medal by the British Royal Society of Literature (1980), and Padma Vibhushan (2001).

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Welcome to Gale International

You appear to be visiting us from United States . Please head to Gale North American site if you are located in the USA or Canada. If you are located outside of North America please visit the Gale International site.

R. K. Narayan (1906-2001)

When R. K. Narayan died on 13 May 2001 at the age of ninety-four, he left behind a body of work that will continue to impress generations of readers. Surveying Narayan's work, one is struck by the breadth and depth of his achievement. His first novel, Swami and Friends: A Novel of Malgudi , was published in 1935, and at the time of his death almost sixty-six years later, Narayan was still writing. In between, he had published novels, short stories, travel books, essays, and retellings of Indian epics, not to mention the articles he had produced as a journalist in his early years. From the 1930s to the early 1990s, when old age finally slowed him down, he managed to write at least three books every decade.

Chronologically, Narayan's fiction takes up the major events of Indian history, including British rule, World War II, the independence movement and the last days of the Raj, Gandhism as a phenomenon, the anxieties and traumas of nation-building, cross-cultural encounters after independence, and ideological debates between tradition and modernity. His characters include schoolboys, college students, teachers, housewives, small tradesmen, lawyers, rogues turned sadhus, taxidermists, dancers, feminists, foreigners in India, and even a tiger who has his own story to tell. Thematically, Narayan deals with such topics as the rites of passage, the education of a young man, a woman's place, death and life, sainthood, destiny and free will, and passivity versus activism. Stylistically, his technique ranges from simple, almost naive, realism to subtle irony. Not averse to using traditional myths and weaving fables into his stories of ordinary people, he is also able to write full-length allegories that manage to be realistic as well and that rely on experiments with narrative perspectives.

Rasipuram Krishnaswami Narayan was born on 10 October 1906 in his grandfather's home in Madras, the son of R. V. Krishnaswami Iyer and Gnana Iyer. His father was a schoolteacher in Mysore. Narayan spent the early years of his life in Madras in the care of his grandmother and a maternal uncle, joining his parents mainly during vacations. In My Days: A Memoir (1974), the novelist notes that his grandmother was a major influence on his life and storytelling. The maternal uncle, who published a literary journal in Tamil, also played a part in the growth of the novelist's mind in these years.

Narayan first went to school in Madras. In 1922 he was shifted to the school in Mysore where his father was the headmaster. My Days indicates that Narayan was an indifferent student but an avid reader in his childhood. He failed the school entrance examination twice and also was unable to get through college easily. Eventually he graduated from Maharaja College of Mysore with a B.A. degree in 1930.

Narayan began to write seriously in the 1920s. In R. K. Narayan: The Early Years: 1906-1945 (1996), his biographers Susan Ram and N. Ram describe his intense desire to see his name in print and the hard work he did, not only reading major English writers and periodicals but also going through books on how to sell one's manuscripts. He soon got accustomed to receiving rejection slips from publishers and newspaper editors; however, Narayan continued to harbor hopes of making a living as a writer, until his father persuaded him to take up a teaching position in a school. The experience proved distasteful to him, and he soon resumed corresponding with English publishers for his manuscripts. He eventually succeeded in getting an article on the Indian cinema published in the Madras Mail in July 1930.

In his memoir, Narayan recalls that he was wandering the streets of Mysore one day at this time of his life when Malgudi, the setting of most of his fiction, just seemed to "hurl" into his mind while he was thinking of a name for a railway station for one of his works. Along with the station, he had a vision then of a character called Swaminathan. He thus began his first novel, Swami and Friends , completing it two years later. Meanwhile, he managed to get a short story titled "A Night in a Rest House" published in The Indian Review (August 1932). What was even more satisfying was seeing a short satirical piece that he wrote called "How to Write an Indian Novel" appear in Punch on 27 September 1933.

That year he also fell in love with a fifteen-year-old girl named Rajam Iyer, whom he spotted as she was waiting to fill water in a brass vessel from a street tap. Too shy to approach her, he persuaded his father to send a proposal of marriage to her father. However, their horoscopes did not match as required by religious custom. Not deterred by this obstacle, Narayan had his father find a way around it. He married Rajam on 1 July 1934. Around this time, he also became the Mysore reporter of a newspaper called The Justice.

When Narayan had finished Swami and Friends in 1932, the odds against an Indian publishing English fiction in England were still high. Conscious that his book would not find a publisher in his country and failing to get a positive response from the English publishers to whom he had sent the manuscript, sometime in 1934 Narayan contacted his friend Krishna Raghavendra Putra, who was then studying at Oxford. When Putra at first had no luck getting publishers to respond, Narayan told his friend to throw the manuscript into the Thames. Instead, Putra persuaded the famous English novelist Graham Greene, who was already attempting to get some of Narayan's short stories published in English magazines, to take a look at Swami and Friends . Greene was so impressed that he recommended the book to the publisher Hamish Hamilton. After suggesting a few changes, including the title (originally "Swami, the Tate"), Hamilton agreed to publish the novel. It appeared in October 1935, and Malgudi was launched as a fictional place to be mentioned almost in the same breath as Thomas Hardy's Wessex, William Faulkner's Yoknapatawpha County, or Gabriel García Márquez 's Macondo.

Swami and Friends is a fictional account of Narayan's childhood. Although modeled on Mysore, Malgudi could be any midsize provincial town in the Indian subcontinent progressing through the twentieth century. Swaminathan, the titular character, grows up against the backdrop of colonial rule and the resistance movement that had already gained momentum throughout the subcontinent. His relationships with schoolmates and family members are rendered with great charm and humor in the novel. The deftness with which Narayan presents the mind of a young boy moving toward adolescence and the skill with which the novelist introduces readers to life in a provincial town make the novel noteworthy.

Typical of the few reviews that greeted the novel in England is the comment of the reviewer of the Morning Post (3 December 1935) that Swami and Friends is "a portrait of childhood pure and simple." The review in the Daily Mail (7 November 1935) was in the same vein: the work was "an entirely delightful story about life in an Indian school with equally vivid glimpses of life in Indian homes." But Narayan's biographers point out that although the reviews of the book were almost all favorable, the book was a failure if judged on the basis of its sales and the fact that Hamish Hamilton declined to be Narayan's publisher in the future.

Nevertheless, Narayan was buoyed by the fact that he had published a book in England and by the laudatory reviews. He began work on his second novel, The Bachelor of Arts (1937), as soon as the first one had been accepted for publication. While he was working on it, his wife gave birth to the couple's only child, a girl called Hema, in February 1936. The novel was completed by March of that year. Narayan sent the manuscript to Greene along with a collection of short stories. Greene was once again enthusiastic and found a literary agent for Narayan in the London firm of Pearn, Hollinger, and Higham. The novel was chosen for publication by Thomas Nelson and Sons and came out in March 1937.

The Bachelor of Arts is a fictional rendering of another phase of the writer's life. The protagonist, Chandran, is an undergraduate student in a missionary college. The resistance movement against the British presence seems to have intensified in the novel, and there is a lot of talk about political reforms, much anticolonial rhetoric, and ideas about the future course of Indian history aired by a few of the characters. However, the main focus of the novel is again on the protagonist's emotional growth, this time from adolescence to manhood. In the first part of the novel Chandran's relationships with friends and family members as well as his teachers are presented endearingly. In the middle part of the book Narayan depicts Chandran in love with a girl called Malathi. He feels intensely for her even though he has only seen her from a distance, but he becomes obsessive about her to the point that he clashes with his parents, who initially will not allow him to marry the girl because of her father's social standing. Even after they relent, he comes across another obstacle that he fails to overcome: the horoscopes of Chandran and Malathi do not match, and so the marriage cannot take place. In the final part of the novel, the frustrated Chandran leaves Malgudi and becomes for some time a mendicant, opting for the life of a holy man to assuage his grief. But he eventually realizes that he has made the wrong decision by deserting his family and has been guilty of self-deception in thinking that he could be a holy man. The chastened Chandran returns to his parents and is finally ready to settle down and marry a girl of their choosing.

The Bachelor of Arts was more widely reviewed than Swami and Friends , and the critics were as appreciative of the book as the reviewers of the first novel had been. The novel came with an enthusiastic introduction by Greene, who compared the Indian writer to Anton Chekhov. The combination of favorable reviews and Greene's endorsement meant that the novel did somewhat better in terms of sales than the previous one, but it still fell far short of being a success in the literary marketplace.

Narayan began work on his third novel, The Dark Room (1938), soon after the second was in print. He was able to send the typescript to Greene by October 1937. Greene was once more positive in his response to the book. Because the publishing house of Nelson declined to publish the new work, Narayan's agent had to locate a new publisher for him and found one in Macmillan in 1938.

The Dark Room shows Narayan moving away from autobiographical fiction. It is also unusual in Narayan's canon because it has a female protagonist. The novel has an almost tragic quality as it portrays the unfulfilled life of Savitri, a woman married to an uncaring but rich husband. In My Days , Narayan explains the frame of mind that led him to write The Dark Room:

I was somehow obsessed with a philosophy of woman as opposed to man, her constant oppressor. This must have been an early testament of the "Woman's Lib" movement. Man assigned her a secondary place and kept her there with such subtlety and cunning that she herself began to lose all notion of her independence, her individuality, stature, and strength. A wife in an orthodox milieu of Indian society was an ideal victim of such circumstances. My novel dealt with her, with this philosophy broadly in the background.

Deeply unhappy after fifteen years of married life, and because she finds out that her husband was having an affair with an employee in his office, Savitri decides to drown herself in the river. But a locksmith-thief who takes her to his home prevents her from taking her life. She then finds employment in the village temple, but the priest is a disagreeable character, and she feels totally depressed about staying without her children. In the end, therefore, she returns to her home and to the dark room that Fate seems to have set aside for her so that she could resume the role of Savitri--the Hindu archetype of the long-suffering, all-sacrificing wife.

Like the previous novels, The Dark Room was a success with the English critics when it was published. Typical of the laudatory reviews was John Brophy's comment in the Daily Telegraph (4 November 1938) that it was "a short, poignant, delicately shaped and finished novel . . . entirely convincing and charming in its reticent sympathy." In India, too, most critics praised the novel, as they had his first two books. The critic K. R. Srinivasa Iyengar, for example, found it to be a carefully and sensitively done portrait of middle-class South Indian society and compared Savitri to the heroine of Henrik Ibsen's A Doll's House (1879), though he concluded Narayan's presentation of Savitri is not a match for the Norwegian dramatist's portrait of Nora. Some Indian reviewers, however, were critical of Narayan's depiction of an Indian marriage, perhaps because, as his biographers indicate, the theme of the mistreated wife was bold for its period.

This novel did as poorly in terms of sales as the first two. Narayan was thus happy to find a regular outlet for his short fiction in the Madras daily, The Hindu. He also received a commission from the Mysore government to write a book on the state, and he researched extensively to write Mysore (1939), a travel narrative interspersed with historical events. Even though he received little money for this project, it allowed him to know Mysore even more intimately.

In June 1939 Narayan entered the darkest period of his life: five years into his marriage, his wife died after a short illness of what was probably typhoid. Overwhelmed with grief, he stopped writing for a while and withdrew into himself. He finally managed to get out of his depression, partly because he had to look after his daughter, but also because he felt that he had succeeded in renewing contact with Rajam through séance sessions. But although he slowly resumed normal activities, the outbreak of World War II impeded literary activity. Also, because Greene became inaccessible then, owing to his involvement in the war effort, Narayan found paths to publishing doubly difficult.

Narayan managed to sustain himself in this difficult period through his journalism and by giving talks on Madras radio. In 1941 he found a further outlet for his work and another vocation when he became the editor of a journal called Indian Thought. Although the periodical proved to be short-lived, the move was important for Narayan's career because it led him ultimately to publish his works in India through his own imprint, Indian Thought Publications. In the first half of the 1940s, three collections of his short stories as well as Swami and Friends and the travelogue Mysore came out in low-priced editions under this imprint. In the process, Narayan became one of the pioneers in publishing South Asian writing in English.

By 1944 Narayan had finished writing his fourth and most autobiographical novel, The English Teacher (1945). This novel is about Krishna, who teaches English in the missionary college that Chandran had graduated from and who vacillates between writing in English and Tamil. It is also a tale about Krishna's family life and bereavement after the death of his wife. Despite their different protagonists, Swami and Friends , The Bachelor of Arts , and The English Teacher can be read together to present the story of the novelist as a boy, a young man, and an adult. The autobiographical connections can be easily made by anyone who has read Narayan's memoir, My Days , even though Narayan inevitably fictionalized his experiences throughout the novels.

The English Teacher can be divided into two parts. The first half of the novel depicts Krishna's delight in his personal life and the satisfaction he derives from his marriage to Susila and the birth of his daughter. The second half presents his initial sense of shock and overwhelming grief at the sudden death of his wife and his efforts to reconcile himself to her loss by attempting spiritual communion with her. The movement of the novel is from bliss to grief to an affirmation of love that can transcend death. Near the end, the protagonist offers a bleakly cyclical vision of life:

Wife, children, brothers, parents, friends. . . . We come together only to go apart again. It is one continuous movement. They move away from us as we move away from them. The law of life can't be avoided. The law comes into operation the moment we detach ourselves from our mother's womb. All struggle and misery in life is due to our attempt to arrest the law or get away from it or in allowing ourselves to be hurt by it. The fact must be recognized. A profound unmitigated loneliness is the only truth of life.

However, the novel concludes with Krishna feeling that he had united with Susila in a mystic moment.

Of Narayan's early novels, The English Teacher was easily the most popular. It was widely praised and sold well in England. Writing in the Glasgow Evening News (29 October 1945), Compton Mackenzie declared it to be "an exquisite experience." A review in The Spectator (12 October 1945) found the novel to be "quite out of the ordinary run." It was the first Narayan novel to be published in the United States: Michigan State College Press brought it out as Grateful to Life and Death in 1953. After the success of this work, Narayan found it much easier to get publishers for his works, and his reputation in the West as well as in India began to grow steadily.

The English Teacher closed one phase of Narayan's career, since it is the last of his novels that depended mostly on the writer's life as the chief source of the narrative. In the next phase of his work as a novelist, he broadened his vision to depict individuals from all parts of society and convey the comic aspects of life as well as its tragic, heartrending moments. Having come to terms with the death of his wife and having achieved a measure of financial stability, he settled into a routine of writing, parenting, and taking the occasional trip out of Mysore. He built his own house in 1948 and saw his daughter get married in 1956. That year he was in the United States for an extended period of time and records his travels there in My Dateless Diary: An American Journey (1960). The critic William Walsh quotes Narayan as saying in 1974 that by then his life "had fallen firmly into a professional pattern: books, agents, contracts, and plenty of letter writing" in addition to visiting his daughter and grandchildren, who lived a hundred miles away.

After The English Teacher , Narayan began to draw on his contacts with people in the outside world for his novels. He also attempted to enrich his presentation of individuals, as he had done before with Savitri in The Dark Room , by searching for character archetypes in the Hindu holy books. As he observes in his essay "English in India," reprinted in A Story-Teller's World (1989), it was necessary to look "at the gods, demons, sages, and kings of our mythology and epics, not as some remote concoctions but as types and symbols, possessing psychological validity even when seen against the contemporary background." Narayan was ready to embark on a major fictional phase of his career, in which he went beyond autobiography and combined his experience of people and places with the founding myths of his nation as well as his thoughts about an India coping with the dawning of independence.

Mr. Sampath (1949), the first novel that Narayan wrote after India's independence, combines his knowledge of the motion-picture world (derived from a stint as a scriptwriter in the late 1940s) with his newfound interest in Indian myths. The novel is an ambitious attempt to represent Malgudi in the final years of British rule and to connect it with a mythical period of Indian history, arriving at a complex perspective on successive waves of colonization. The protagonist, Srinivas, is a rather confused but likable journalist who turns to scriptwriting for a movie on the god Shiva, the god's love for Parvithi, and his encounter with Kama, the god of love. But Srinivas's bid to come up with a script that would do justice to the mythical tale fails, apparently because the ancient tales cannot be presented in the contemporary world except in an adulterated form. The quotidian, too, constantly diverts Srinivas from the mythical past. In a vision, Srinivas learns the essential lesson about the perspective to be taken on what was happening in the country: "Dynasties rose and fell. Palaces and mansions appeared and disappeared. The entire country went down under the fire and sword of the invader. . . . But it always had its rebirth and growth." In other words, Indian history existed in a state of flux, and change was inevitable, as was the resilience of India and Indians.

The titular character is an egotistical, domineering, and amoral printer with whom Srinivas has to work to bring out his journal. Sampath is the one who leads Srinivas away from journalism to the movie industry. But Sampath's energy and egotism as well as lack of scruples create a mess that is further complicated by the unstable studio artist Ravi's passion for the actress Shanti, who has an affair with Sampath. In his vitality as well as selfishness, Sampath becomes a forerunner of other Narayan characters who disrupt social life because of their egotism and indifference to others or the norms of society. He thus stands in contrast with Srinivas, who, as the critic A. Hariprasana observes, "realizes that he cannot achieve self-identity in isolation" and learns to value the importance of becoming involved "in the web of human relationships" and of restraint and self-knowledge as precursors to the coming of wisdom.

The Financial Expert (1952), Narayan's next novel, uses Hindu myths creatively. The book is a realistic novel of Malgudi in the 1930s and early 1940s as well as an effective fable. Margayya, its protagonist, has acquired a fortune by publishing a quasi-pornographic book whose rights he had purchased for a paltry sum from the eccentric Dr. Pal, and he continues to raise money through questionable means. But he forgets the injunction of a priest who had cautioned him that one cannot appease Saraswati, the goddess of knowledge, and Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth, at the same time. Margayya tries to buy his son, Balu, an education by making himself the head of the school board and by neutralizing the fiercest teacher of the school. The result, however, is that Balu ends up a totally spoiled individual, indifferent to education, work, or the wife Margayya chooses for him.

Margayya discovers thus that all his wealth does not bring happiness either to him or to his wife and only corrupts his son. Narayan's point in the novel is a simple but profound one: true riches can never accrue when one makes money into a god or pursues dubious paths to wealth. At the conclusion of the novel, Margayya has lost all the wealth he had acquired from his financial shenanigans, but in the process he has learned that money is not everything. When he had wealth, he lacked enlightenment; when he loses everything he has acquired illicitly, he comes closer to self-knowledge. The novel ends as it begins, with Margayya ready to resume his old profession of adviser to peasants seeking help; but he appears to have learned his lesson and seems ready to start again in life.

The Financial Expert shows Narayan the novelist at his best in the way he handles the central theme of the vanity of human wishes, in his deft manipulation of events and structuring of the events in Margayya's life, and in the portrait of the central character, who is deeply flawed but also all too human and thus capable of retaining the reader's sympathy. The novel is memorable too for the portraits of Dr. Pal, the archetypal confidence man; Meenakshi, Margayya's long-suffering wife; and Balu, his prodigal son. Margayya's rise and fall take place against a backdrop of a world full of poverty, corruption, red tape, and the opportunism displayed by cynical businessmen and officials in wartime India. Narayan manages to be serious and comic throughout the novel; he also alternates details of everyday life in Malgudi with moments when readers get to view the workings of Margayya's mind. The critic William Walsh writes that the novel "has an intricate and silken organization, a scheme of composition holding everything together in a vibrant and balanced union."

Narayan followed The Financial Expert with his most political novel: Waiting for the Mahatma (1955). Written eight years after India's independence and the death of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, this work portrays in considerable detail the years leading to the partition of India. It is something of a postmortem on the roles played by Gandhi and his followers in the independence struggle and the way in which India had become vulnerable afterward because many Indians had not taken Gandhi's message of nonviolence and communal harmony to heart. Sriram, the central character, joins the freedom movement not because of his devotion to Gandhi but because of his passion for the Gandhian activist Bharati. Nevertheless, he becomes involved in almost all the major events leading to Indian independence and even goes to jail for taking part in a terrorist movement aimed at driving the British from India.

Narayan suggests through this novel that the bloodshed and divisiveness that accompanied the partition of India was inevitable, because people driven by personal passions and self-interest had cast the great leader's message aside. In the novel, except for Bharati, no one appears to be in the freedom struggle for love of India or seems inclined to follow Gandhi's teachings faithfully. The consequence is that post-independence India is, if anything, in worse condition than it was when the British had left it, for it has become a land full of religious riots, hunger, and unscrupulous politicians like the unprincipled Jagadish, a former terrorist who is now thriving financially. The novel concludes with Gandhi's assassination, although the great man blesses Sriram's marriage to Bharati before he is shot, suggesting that perhaps the couple will be able to keep Gandhi's spirit alive despite the many who have deviated from his philosophy and idealism.

Perhaps Narayan's most famous novel is his subsequent one, The Guide (1958), a work he wrote while he was in Berkeley, California, during his visit to America in 1958. It is the story of Raju, a scamp who ends up being perceived as a savior by many people. When the novel begins, he has just been released from jail. He wanders into a small town, where he finds Velan, a villager who is soon convinced that he has confronted a holy man and makes himself Raju's disciple. Soon after the meeting, Raju tries to dissuade Velan from hero worship by telling him the story of his life. While Raju relates to Velan his progress--from a wide-eyed child to the owner of a railway stall, a tourist guide, the lover and impresario of the classical dancer Rosie, and finally a jailbird--the narrator punctuates Raju's story by showing his dealings with Velan and the villagers who embrace him as a spiritual guide capable of leading the village out of a drought through a penitential fast. Raju's purpose in telling his story to Velan is to demystify his spiritual powers and to emphasize his shady past. Velan, however, is unmoved by the story and continues to see Raju as a guru. After Raju concludes his narrative, the omniscient narrator takes sole charge of the narration duties. The conclusion shows a Raju who may or may not be at the point of achieving transcendence.

Characteristically, Narayan interlaces the story of Raju with frequent references to Hindu theology. The Guide sets out to compare Raju's progress to that of Devaka, a man from India's legendary past, whose story Raju's mother used to tell him before the child used to doze off, so that he never could come to learn the ending, and so that as an adult, he could only remember that Devaka was "a hero, saint, or something of the kind." Also, Raju's excessive lust for sex and wealth and his taste for a life of luxury are precisely the sins Hindu metaphysical tradition cautions against, because giving in to such desires means forgetting that the world is maya (an illusion) and losing sight of the belief that a man must transcend this world by showing bhakti (true devotion).

The Guide is Narayan's most popular book, partly because of its witty presentation of Raju's character and partly because of its intricate narrative technique of the first-person account of Raju alternating with the omniscient narrator's presentation of the lovable rogue who becomes unwittingly a hero. The novel is also memorable because of its presentation of Rosie, who grows in stature throughout the work: she begins as a bored housewife who enters into an adulterous relationship with Raju, but by the time the novel ends, she has become a classical dancer of repute.

Typical of the praise heaped on the novel and its writer is the comment made by Anthony West in The New Yorker (19 April 1958): " The Guide is the latest, and the best, of R. K. Narayan's enchanting novels about the South Indian town of Malgudi and its people. . . . It is a profound statement of Indian realities." The Guide won India's highest literary prize, the Sahitya Akademi Award, in 1960. The novel was also made into a highly popular movie in 1965 that made Narayan even more famous in India. However, he disapproved of the script and distanced himself from it because he felt it had vulgarized his work.

Narayan followed The Guide with another triumph: The Man-Eater of Malgudi (1961). It is the story of Nataraj, an amiable and docile printer of Malgudi, who encounters Vasu, a taxidermist from outside the town who takes over Nataraj's attic to use it as a base for his grisly profession. Vasu is brisk, powerfully built, egotistical, and totally indifferent to the community's values. Narayan implies in his narrative that Vasu is a rakshasha, the type of demon who challenged the gods themselves. Nataraj's assistant Sastri, well-versed in Indian myths, even views Vasu as Bhasmasura, the demon of Indian myth who blights everything he touches, defies the heavens, and puts humanity into peril. But Bhasmasura is also an overreacher whose pride results in self-annihilation. In the novel, too, Vasu self-destructs when he inadvertently kills himself while squashing a mosquito that had landed on his forehead.

But The Man-Eater of Malgudi is also the story of its narrator, Nataraj, who is initially a passive character. He prefers to spend his time in the first part of the novel by chatting with his friends but is transformed by his contact with Vasu and the latter's intimidating ways into taking the offensive to contain "the man-eater of Malgudi." Thus, in the concluding parts of the novel Nataraj finds himself acting more like Vasu. He even wonders if in a fit of aggression he had been instrumental in cornering the taxidermist, perhaps thereby forcing himself to self-destruct.

Narayan presents the Vasu-Nataraj relationship against the backdrop of everyday life in Malgudi and a cast of idiosyncratic minor characters. His skill in depicting life in a midsize provincial town of India is evident. The Man-Eater of Malgudi is also a funny novel and reveals Narayan's delight in the human comedy. Narayan's technique in the work is an unobtrusive one as he takes readers from the tranquil opening to the frenzied climax of the story. Like The Guide , this book was received enthusiastically on publication. Donald Barr commented in The New York Times Book Review (12 February 1961): "it is classical art, profound and delicate art, profound in feeling and delicate in control."

Narayan's next novel, The Vendor of Sweets (1967), once again appears to set up tradition against disruptive Western influences. V. S. Naipaul sees the novel as characteristic of Narayan's work because of its theme: "there is a venture into the world of doing, and at the end there is a withdrawal." Tradition and the unchanging Indian world is here represented by Jagan, the vendor of sweets, and modernity by his son Mali, who has come back from America with Grace, a Korean American woman, and innovative business schemes. The novel is set in the 1960s, but Jagan keeps thinking about India's Gandhian past and his role in it as an activist inspired by the Mahatma. Jagan, a traditionalist by instinct, also treasures, paradoxically, mementos of the Raj as well as Indian greats, valuing the works of William Shakespeare as well as those of Rabindranath Tagore.

As Ashok Berry has stressed, Narayan is setting up an opposition between tradition and modernity in a way that will invert "the dominant hierarchy." Thus, the novel concludes with Jagan retreating from the world of Mali and Grace, but he does not forget to take his checkbook with him. Jagan also approves of Grace and is only upset because his son had backed off from his promise to marry her. While Naipaul says that the novel concludes with Jagan's withdrawal from modernity, Berry emphasizes Narayan's complex perspective on the novel when he says that it is "precisely about accommodating imperfection and hybridity. By destabilizing ideas of purity, it paves the way for different conceptions of identity."

Although not as successful as either The Guide or The Man-Eater of Malgudi , The Vendor of Sweets reveals Narayan's gift for characterization, as Jagan is a complex creation: comic, shrewd, and vain but also an idealist and a caring father whose loneliness attracts the reader's compassion. The portrait of Mali and his scheme of marketing a storytelling machine is Narayan's way of satirizing harebrained business ideas and uncritical acceptance of Western values, but Grace is portrayed with sympathy and understanding. The novel, typically, reveals the changing world of Malgudi, where cross-cultural exchanges take place even as the traditional values of the Bhagavad Gita , the Hindu sacred text that is Jagan's constant companion, continue to be a guide for people of his generation.

Narayan's subsequent novel, The Painter of Signs (1976), is one of his most impressive longer works of fiction. It echoes many of Narayan's earlier novels in its themes as well as its structure. The plot--about an obsessive young man, Raman, who pursues Daisy, a woman dedicated to easing overpopulation, the national issue of the 1970s--echoes Waiting for the Mahatma , which was about Sriram's single-minded pursuit of the zealous Gandhian, Bharati. Throughout the novel Raman broods on philosophical as well as topical issues, as did Srinivas of Mr. Sampath . Like Rosie of The Guide , Daisy is a modern woman, not afraid of transgressing conventional notions of morality in pursuit of her vocation. However, Daisy is even more independent minded than Rosie, for in the end she makes a clean break from Raman, something Narayan's earlier women seemed unable or unwilling to do. As Sadhana Allison Puranik points out, such a "radical overturning of convention" indicates that there is a subversive element in Narayan even though it coexists with "his love of traditional elements of Indian life and art." Puranik also stresses the political dimension of the novel and its contemporaneity: connecting Daisy's fanaticism about family planning with Indira Gandhi's excesses in enforcing it in India, Puranik thinks that "Narayan implicitly criticizes the attitude of cultural extremism apparent in the government's domestic policies."

As if to mark the change in Indian mores, the novel is much more explicit about sexuality than Narayan's other longer works of fiction. Also, Narayan seems more reform minded in this novel than in his earlier works. Daisy appears to have no inclination to be like Savitri from The Dark Room , and Narayan shows her leaving conventional notions of womanhood behind altogether. While it is too much to say that Narayan endorses Daisy's independence totally or upholds the ideology of the single woman or family planning unambiguously, the novel accepts her modernity to a great extent and shows her ideas gaining acceptance among quite a few women even when they conflict with other upholders of tradition.

Narayan's twelfth novel, A Tiger for Malgudi (1983), is distinctive in having a protagonist who is a tiger. He is called Raja, and he narrates the story of the spiritual changes he undergoes. In the introduction to the novel, Narayan writes that the idea of adopting such an unusual point of view came to him when he saw a tiger accompanying a sadhu in the Hindu Kumbh Mela, a major Hindu festival. What struck him in particular was that the tiger was not on a leash, and that the holy man accounted for the tiger's freedom by saying "they were brothers in previous lives." This encounter led Narayan to think about the tiger's perspective on life--which, he would have readers believe, evolved not unlike that of human beings. The book presents details of Raja's life as a cub, his brashness as he arrives at his physical peak, his capture and conversion into the star attraction of a circus, his "elevation" into a celebrity after being cast in movie roles, his escape from captivity, and his adoption by an ascetic. This sagacious man's views give Raja insight into life and death, making him appreciate that "separation is the law of life right from the mother's womb" and thus has to be accepted as part of God's plans for all animals. He also accepts the notion that one should free oneself from worldly attachments. Raja ends up in a zoo but appears to have achieved enlightenment and a mature acceptance of life. Because the protagonist is a tiger, the novel often strikes a comic note.

A Tiger for Malgudi was the last of Narayan's novels to receive wide critical attention. But it got mixed reviews, and a few critics recorded their disappointment with it. Writing in The New York Times Book Review (4 September 1983), for example, Noel Perrin noted that the book is "distinctly not drenched with humanity" and that "most of the flavor of Malgudi is missing." Similarly, Carlo Coppola observed in a review in World Literature Today (Spring 1984) that although there are good things in the book, "in the last analysis . . . the novel falls short of Narayan's best achievements (viz., The Financial Expert , The Guide , The Man-Eater of Malgudi ) because the author fails to convince us of the final phase of Raja's quest."

Narayan was eighty years old when he published his next novel, Talkative Man , in 1986. This story is another take on a theme that fascinated him throughout his career as a novelist: the fate of the long-suffering Indian wife. Although Malgudi has changed, the wife of this tale, Sarasa, continues to suffer because of her indifferent and philandering husband, the confidence man Rann, who claims to be working for the United Nations. She is financially independent, but she cannot part from him despite his obtuseness and tendency to abandon her. In her determination to stick to him, she is, in some ways, like Savitri of The Dark Room. The novel is of interest because of the titular character, the talkative man, a persona Narayan has used in many of his short fictions to reveal his delight in raconteurs and their garrulousness, which at times makes them sound comically gullible.

Narayan published his last novel, The World of Nagaraj (1990), four years after Talkative Man . The title character follows a holy man who has renounced the world and is bent on leaving it behind, freeing himself from the world of the senses so that he can concentrate fully on God. Nagaraj, too, appears to be preparing himself for forsaking earthly attachments and welcoming death. Nevertheless, Nagaraj continues to be dragged back into the quotidian because of his spoiled nephew Tim, who has a nose for trouble and involves Nagaraj in his problems. This entanglement makes him unable to renounce the world effectively, putting him in contrast with the mythical sage Narada, who has given up all earthly desires for the benefit of humanity at large.

The last long work of fiction that Narayan published in his lifetime is Grandmother's Tale (1992). It is essentially a novella, but the author himself points out in an explanatory note that it is a work located in "the borderline between fact and fiction, between biography and tale," and between family history and quest narrative. In it Narayan retells his great-grandmother's search for her husband, who had disappeared after telling her "laconically" one day, "I am going away." Re-creating the world of nineteenth-century India, where women were forced to lead much more confined lives than characters such as Sarasa of Talkative Man , this novel shows the triumph of Narayan's great-grandmother's love and the indomitable spirit that led her to her husband and allowed her to end her life happily.

Among Narayan's strengths as a novelist are the economy of his storytelling and the skill with which he manipulates his plot so that events that complicate the lives of his central characters are resolved within a couple hundred pages. Narayan is also a master of shorter forms of fiction, and he brought out five collections of short stories, most of them published first in the Madras newspaper The Hindu . They cover the same territory as the novels; indeed, the first collection was called Malgudi Days (1943). The stories of the early collections are slight pieces and usually reportorial in style, lacking the plotted quality of the novels. Some are anecdotal or no more than character sketches. The stories of the later collections are longer and more intricately built. Usually they show people as fallible, eccentric, or merely amusing. Some are about animals, and some present children and deal with the theme of growing up. Most often Narayan uses the short story to depict ordinary people in everyday situations with a light touch but also in a manner that reminds readers that his mission is to be the chronicler of Indian life. He registers the poverty of Malgudians and occasionally ventures into social criticism. A few of the stories are satirical in tone, and there is even a touch of the absurd in one or two of them. As in the novels, the dominant mood is of mild irony; but the best of them can be funny, as is the case with "A Horse and Two Goats," a hilarious account of cultural misunderstanding.

Narayan's collections of short tales include the volume Gods, Demons, and Others (1964). These stories are, as the title indicates, attempts to re-create Indian myths. They show Narayan adopting the role of the traditional storyteller who regales his audience with tales about a supernatural world that is of interest to mortals and that combines instruction with enjoyment. Narayan evidently enjoyed this role and found that modern audiences delighted in his versions; he thus went on to create his own versions of India's great epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata . These volumes, published in 1972 and 1978 respectively, complement the world of Malgudi portrayed in the novels and the short fiction, in which his situations and characters often allude to the Hindu holy books and legends. Patrick Swinden has noted that what Narayan's narrator says about the sage Narada in The World of Nagaraj could also be applied to the author: he "floats with ease from one world to another . . . carrying news and gossip, often causing clashes between gods and demons, demons and demons, and gods and gods, and between the creatures of the earth."

Any survey of Narayan's career should also take note of his miscellaneous writings and essays on literature, for as a practicing journalist as well as an author often invited to present his thoughts on writing and art, he published several collections of nonfictional prose. Essays such as his "Introduction to The Financial Expert, " collected in A Story-Teller's World , and "Misguided Guide," reprinted in A Writer's Nightmare (1988), give readers the contexts of his novels. Essays such as "Mysore City" (in A Story-Teller's World ) furnish them with details that are helpful in understanding the Malgudi setting. They also remind readers how close his novels are to the South Indian world he knew so intimately. Other essays provide information about his views on storytelling, the problems facing the Indian writer, the status of English in India, East-West encounters, and his delight in everyday life and simple events as well as his eye for the oddities of people. His two extended works of nonfiction are his memoir, My Days , and My Dateless Diary , in which he describes his travels in America and encounters with Americans during a nine-month visit sponsored by the Rockefeller Foundation.

Narayan received some major awards for his work. In addition to the Sahitya Akademi Award for The Guide , the Indian government conferred on him the Padma Bhushan, one of India's leading awards, in 1964 for his overall achievement. He was also decorated with the Royal Society's Benson Medal in 1980 and was made a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature that year. He was a visiting professor at Michigan State University and Columbia University in the United States. Major Indian universities and the University of Leeds conferred honorary degrees on him.

Narayan died on 13 May 2001. Viewing Narayan's achievement in perspective at the beginning of the twenty-first century, one can see that he has been one of the leading Indian writers in English of the previous century. The first wave of Indians writing in English, comprising men and women such as Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, Raja Rammohon Roy, Michael Modhusudhan Dutt, and Toru Dutt, had little or no impact on English literature. Many of these writers failed in using a language that was not their own and soon switched to their mother tongues. The second generation were the true pioneers: writers such as Nirad C. Chaudhuri, Narayan, Mulk Raj Anand, and Kamala Markandaya managed to attract a limited but devoted following not only in India but also all over the world. A few of them, Chaudhuri and Narayan for instance, even managed to win major literary awards overseas. Significantly, of these writers, Narayan was the only one ever considered for the Nobel Prize in literature. His fame continued to increase decade by decade, and his work continued to be published both in India and the West throughout the twentieth century.

The arrival of the third wave of Indian writers in English with Salman Rushdie's Midnight's Children (1981), a wave that swept forward writers such as Amitav Ghosh, Vikram Seth, Anita Desai, and Arundhati Roy, did not distract attention from Narayan but rather showed the solidity of his achievement. His peers as well as successors have been quick to acknowledge Narayan's contribution to Indian writing in English. In an essay written at Narayan's death, the distinguished Indian poet Dom Moraes called Narayan "by far the best writer of English fiction that his country has ever produced." Pankaj Mishra, one of the Indian writers in English now making their mark globally, declared in another eulogy that Narayan was "a precursor I could look up to and learn from, and I can't overestimate the importance of this to a young writer working in a tradition that doesn't seem very coherent."

With only Greene's help, but without the flamboyance of Rushdie or the benefit of postcolonial theory, R. K. Narayan carved a niche for himself nationally and internationally. For more than half a century he produced quality work despite writing in a language not his own while staying in India almost all the time. Mishra's New York Review of Books obituary survey can be invoked again to sum up Narayan's achievement: his "unmediated fidelity" to his world and "instinctive understanding of it" make him "a more accurate guide to modern India than the intellectually more ambitious writers of recent years."

Alam, Fakrul. " R. K. Narayan ." South Asian Writers in English , edited by Fakrul Alam, Gale, 2006.

FURTHER READING

From: Alam, Fakrul. "R. K. Narayan." South Asian Writers in English , edited by Fakrul Alam, Gale, 2006.

- Susan Ram and N. Ram, R. K. Narayan: The Early Years: 1906-1945 (New Delhi: Viking, 1996).

- Ashok Berry, "Purity, Hybridity and Identity: R. K. Narayan's The Vendor of Sweets, " WLWE, 35 (1996): 51-62.

- A. Hariprasana, The World of Malgudi: A Study of R. K. Narayan's Novels (New Delhi: Prestige Books, 1994).

- Pankaj Mishra, "The Great Narayan," New York Review of Books, 22 February 2001: 44-47.

- Dom Moraes, "A Gentle Enchantment," www.tehleka.com.

- V. S. Naipaul, India: A Wounded Civilization (New York: Vintage, 1976).

- Sadhana Allison Puranik, " The Painter of Signs: Breaking the Frontier," in R. K. Narayan: Contemporary Critical Perspectives, edited by Geoffrey Kain (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 1993), pp. 125-140.

- Patrick Swinden, "Gods, Demons and Others in the Novels of R. K. Narayan," in R. K. Narayan: An Anthology of Recent Criticism, edited by C. N. Srinath (Delhi: Pencraft International, 2000), pp. 36-49.

- William Walsh, R. K. Narayan: A Critical Appreciation (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982).

From: James Overholtzer. "R. K. Narayan." Contemporary Literary Criticism , edited by Jennifer Stock, vol. 452, Gale, 2020.

Bibliography

- Rao, Ranga. “Bibliography”. R. K. Narayan: The Novelist and His Art , Oxford UP, 2017, pp. 293-309. In the absence of a dedicated, full-length Narayan bibliography, the primary and secondary listings included in Rao’s biography are the most useful resources.

- Ram, Susan, and N. Ram. R. K. Narayan: The Early Years, 1906-1945 . New Delhi, Viking, 1996. The definitive biography of Narayan’s early life, which benefits from the authors’ friendship with the writer in his later years. The details of Graham Greene’s role in the publication of Narayan’s first novels and Narayan’s response to the tragic death of his young wife are particularly interesting. There is no comparable biography of the later years.

- Alam, Fakrul. “Plot and Character in R. K. Narayan’s Man-Eater of Malgudi : A Reassessment”. ARIEL , vol. 19, no. 3, 1988, pp. 77-92. Argues against views of The Man-Eater of Malgudi which see it as a struggle between good and evil, as represented by the protagonist, Nataraj, and his supposedly demonic adversary, Vasu. Alam suggests to the contrary that their characters overlap, a narrative feature that can be interpreted in terms of the Freudian concept of identification.

- Albertazzi, Silvia. “The Story-Teller and the Talkative Man: Some Conventions of Oral Literature in R. K. Narayan’s Short Stories”. Commonwealth Essays and Studies , vol. 9, no. 2, Spring 1987, pp. 59-64. Interprets Narayan’s short fiction as having affinities with the traditional Indian tales of the puranas, including a dialog form and an episodic structure. Albertazzi argues that his use of the figure of the Talkative Man as a narrator for six of the stories in An Astrologer’s Day, and Other Stories (1947) is designed to make readers feel they are participating in an oral tale.

- Almond, Ian. “Darker Shades of Malgudi: Solitary Figures of Modernity in the Short Stories of R. K. Narayan”. Journal of Commonwealth Literature , vol. 36, no. 2, 2001, pp. 107-116. Investigates what it was in Narayan’s work that led Greene to feel he had found a ‘second home’ there. Almond identifies recurring patterns in a broad spectrum of Narayan’s short fiction before focusing on the ambiguous representation of modernity in stories where it comes into dialog with tradition. He concludes that the darkness underlying Narayan’s comic elements may well have struck a chord with Greene’s sense of “loyalty” to unhappiness.

- Bery, Ashok. “‘Changing the Script’: R. K. Narayan and Hinduism”. ARIEL , vol. 28, no. 2, 1997, pp. 7-20. Argues that seeing Narayan as a Hindu traditionalist gives a distorted picture of his work and needs qualification. Bery claims that some of Narayan’s novels explore the limitations and contradictions in Hindu worldviews.

- Chew, Shirley, “A Proper Detachment: The Novels of R. K. Narayan”. Southern Review , vol. 5, no. 2, June 1972, pp. 147-159. Discusses a wide range of Narayan’s novels, from The Bachelor of Arts to The Vendor of Sweets. Chew contends that in Narayan’s early novels, his protagonists self-consciously strive to achieve a form of detachment that accords with traditional Hindu wisdom, but she notes that this can be contrived. In later novels, Chew observes, the theme of detachment is more dramatically realized through lived experience.

- Greene, Graham. “Introduction”. The Bachelor of Arts , London, Thomas Nelson, 1937, pp. v-x. Relates how Greene first became aware of Narayan and praises him for conveying a sense of essential Indianness, for populating Malgudi with memorable characters, and for combining sadness and humor in a manner reminiscent of Anton Chekhov.

- Naipaul, V. S. India: A Wounded Civilization . Alfred A. Knopf, 1977. Argues that Narayan’s novels are “religious fables” about the Hindu doctrine of karma, which he views as a quietist philosophy, rather than the purely social comedies he originally had assumed. Naipaul’s discussion focuses on Mr. Sampath and The Vendor of Sweets. [Excerpted in CLC, Vol. 28.]

- Narayan, R. K. “The World of the Story-Teller”. A Story-Teller’s World: Essays, Sketches, Stories , Penguin, 1989, pp. 3-9. Discusses the role of the storyteller in Indian village communities. Narayan casts light on his own narrative practice. He sees the figure as an oral repository of ancient Hindu wisdom, a man who conserves the legends and myths of the Vedas and tells tales from the Sanskrit epics that embody universally valid archetypes. Narayan comments that demons always carry the seeds of their own destruction, a remark that has particular resonance for his novel The Man-Eater of Malgudi.

- Rao, Ranga. “Enchantment in Life: Mr. Sampath and the Naipaul Enigma”. R. K. Narayan: The Novelist and His Art , Oxford UP, 2017, pp. 89-119. View Narayan’s novels as guna comedies, in which the three basic qualities of human nature (gunas) determine the behavior of people. Rao interprets Mr. Sampath as a transitional work, in which the central characters, Srinivas and Sampath, represent two of these personality types: the sattvic (idealistic) and the rajasic (worldly). He argues that the creative ambivalence of the style embodies the novel’s moral pluralism and rebuts Naipaul’s reading of the novel.