What Is Life Skills Education: Importance, Challenges, & Categories

Life skills education has become commonplace today, but many people do not know what it means.

However, as the world changes, so do many things, including how we define and look at life skills education.

This type of education is not focused on teaching young people to pass exams and go to university but rather prepares them to live useful and successful lives.

Life skills are essential because they form the foundation for success in many areas of life.

This article examines the importance of life skills education, what life skills are, and the benefits of learning them.

What are life skills?

Additionally, these kinds of skills are broad and transferable. That means they are applicable across different situations in life, including; home, work, community settings, and leisure activities.

It also includes your knowledge about how to access health care when needed.

Why is life skills education important?

Life skills education empowers young people to lead healthy, productive lives.

Also, life skills training for all young people is critical. Human development specialists agree that youth need a particular life skill competencies to thrive, stay healthy, and succeed.

Also, it helps you to manage your emotions and behavior, establish healthy relationships, make responsible decisions, and enjoy learning.

It is a strategy for promoting mental health that focuses on creating a positive and supportive school environment.

What are the benefits of life skills education?

Life skills education has proven so essential for child development that governments and education authorities in many countries have introduced it as an essential part of the school curriculum .

This education gives children the confidence and ability to make healthy choices, manage their emotions, and build strong relationships.

Training in life skills can give children a toolbox of approaches, strategies, and coping mechanisms to support their learning.

1. Strengthens the self-respect of children

Self-esteem is a child’s belief in her worth as a person or friend. When your child develops healthy self-esteem, she branches out from family and friends, exploring the world and trying new things.

Furthermore, children who develop self-respect have a better chance of successful lives.

2. Gives children tools to improve their quality of life

Through life skills education, students learn essential skills to benefit their peace of mind and quality of life.

Also, they learn how to manage stress, calm their minds and bodies, exercise, eat healthy, set goals, stay on top of their responsibilities, and more.

3. Kids develop a sense of social responsibility

It also fosters an understanding of teamwork and leadership that applies to every situation throughout their lives.

4. Life skills education develops teamwork skills

Children who have learned life skills are better prepared to tackle academic courses, build strong relationships with peers, and succeed socially and emotionally.

5. It helps students feel more confident

Students also learn to be more proficient in communication, child development, food proficiency, money management, and physical activity.

6. Children learn to use resources wisely

Life skills training helps children use their essential life resources-time, space, and materials wisely.

In addition, the ability to utilize these resources wisely is essential for success in all work and leisure areas.

7. Life skills education makes students self-sufficient and confident adults

8. helps with focus and attention skills.

The life skills curriculum covers critical topics like stress management, respectful communication, self-advocacy, sensory processing, executive functioning, and memory in a fun and engaging environment.

9. Improves time management skills

Research shows that life skills education improves time management skills and helps children plan for their goals.

Students also learn how to set a schedule, stick to it, determine resources to allocate, and see which tasks are urgent.

10. Life skills education encourages independence in kids

From interviewing for a job to managing finances, life skills education can be the key to living a fulfilling life as an adult.

11. Life skills education gives a boost to academic success

12. develops observation and critical thinking skills.

The activities should also promote the development of fine motor and communication skills, visual observation, and cognitive thinking abilities.

What are the challenges affecting life skills education?

The challenges affecting life skills education include; a lack of resources, inadequate teacher and learner training, family support problems, dual responsibility to meet literacy and life skills targets, and managing cultural sensitivities.

This occurs by encouraging them to think about what they want from their education and how it helps them develop as a whole person.

What are the categories of life skills?

Life skills include interpersonal and self-awareness skills, communication, decision-making, problem-solving, and coping with emotions.

These categories encompass many life skills, from physical to mental health.

Self-awareness skills

Communication skills.

Communication skills are talents and abilities that enable you to convey your thoughts, feelings, ideas, and information to others.

Decision making skills

Decision-making involves identifying a decision, gathering information, and assessing alternative resolutions.

Problem solving skills

The better your problem-solving skills are, the more asset you will be to an employer or project team.

Coping skills

They are used to increase self-control and emotional regulation to better handle disappointment, frustration, and other negative feelings.

How does life skills education affect society?

Why is life skills education necessary for employment.

Life skills training provides young people with the knowledge and experience they will need to succeed in their careers.

Why is life skills education crucial to a child’s development?

This teaching method helps children develop social-emotional skills essential for school achievement and success in adulthood.

Also, through life skills, children learn to deal with transition, stress, emotion, impulse control, self-esteem, and evaluation of consequences.

Life skills education is proven to impact children in the following ways: – Improved academic performance, improved social and emotional health, improved mental health, decreased stress, burnout, and anxiety.

Finally, teaching children adaptive skills also helps them maximize their potential.

You may also like:

Why do waiters get paid so little [+ how to make more money], navigating workplace norms: can you email a resignation letter, difference between roles and responsibilities, does suspension mean termination, moral claim: definition, significance, contemporary issues, & challenges, why can’t you flush the toilet after a drug test.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Malays J Med Sci

- v.30(3); 2023 Jun

- PMC10325125

Effectiveness of Life Skills Intervention on Depression, Anxiety and Stress among Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review

Yosra sherif.

1 Department of Community Health, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Selangor, Malaysia

Ahmad Zaid Fattah Azman

Hamidin awang.

2 Psychiatry Unit, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Sains Islam Malaysia, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia

Siti Aisha Mokhtar

Marjan mohammadzadeh.

3 Institute of Health and Nursing Sciences, Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Corporate Member of Freie Universität Berlin and Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Berlin, Germany

Aisha Siddiqah Alimuddin

4 Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Selangor, Malaysia

Associated Data

Electronic databases

| Database | Number |

|---|---|

| Academic Search Complete | 591 |

| MEDLINE Complete | 357 |

| CINAHL Plus with full text | 208 |

| Psychology and Behavioural Sciences Collection | 163 |

| Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials | 66 |

| Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | 3 |

| Web of Science | 218 |

| Scopus | 400 |

| PubMed | 154 |

| All | 2160 |

| Narrow by Langue | English |

Methodological quality of randomised controlled trial

| Studies | Criteria | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1* | 2* | 3* | 4* | 5* | 6* | 7* | 8* | 9* | 10* | 11* | 12* | 13* | Overall | |

| Mohammadzadeh et al. ( ) | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 11/13 85% |

| Lee et al. ( ) | Y | Y | Y | U | N | U | Y | U | N | Y | Y | Y | N | 8/13 62% |

| Jamali et al. ( ) | Y | N | Y | U | U | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9/13 69% |

| Total | 3/3 100% | 2/3 66% | 3/3 100% | 1/3 33% | 0/3 0% | 0/3 0% | 3/3 100% | 2/3 66% | 2/3 66% | 3/3 100% | 3/3 100% | 3/3 100% | 2/3 66% | |

Notes: JBI methodological quality appraisal checklist to be scored as: Yes = Y; No = N; Unclear = U; Not applicable = NA;

1* Was true randomisation used for assignment of participants to treatment groups?

2* Was allocation to treatment groups concealed?

3* Were treatment groups similar at the baseline?

4* Were participants blind to treatment assignment?

5* Were those delivering treatment blind to treatment assignment?

6* Were outcomes assessors blind to treatment assignment?

7* Were treatment groups treated identically other than the intervention of interest?

8* Was follow up complete and if not, were differences between groups in terms of their follow up adequately described and analysed?

9* Were participants analysed in the groups to which they were randomised?

10* Were outcomes measured in the same way for treatment groups?

11* Were outcomes measured in a reliable way?

12* Was appropriate statistical analysis used?

13* Was the trial design appropriate, and any deviations from the standard RCT design (individual randomisation, parallel groups) accounted for in the conduct and analysis of the trial?

Methodological quality of quasi-experimental study

| Studies | Criteria | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1* | 2* | 3* | 4* | 5* | 6* | 7* | 8* | 9* | Overall | |

| McMullen and McMullen ( ) | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8/9 88% |

| Roy et al. ( ) | Y | Y | N | N | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | 6/9 66% |

| Yankey and Urmi ( ) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9/9 100% |

| Ndetei et al. ( ) | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | 7/9 77% |

| Mohammadi and Poursaberi ( ) | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | 7/9 77% |

| Eslami et al. ( ) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9/9 100% |

| McMahon and Hanrahan ( ) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | 8/9 88% |

| Total | 7/7 100% | 7/7 100% | 4/7 57% | 5/7 71% | 7/7 100% | 4/7 57% | 7/7 100% | 6/7 85% | 7/7 100% | |

1* Is it clear in the study what is the ‘cause’ and what is the ‘effect’ (i.e. there is no confusion about which variable comes first)?

2* Were the participants included in any comparisons similar?

3* Were the participants included in any comparisons receiving similar treatment/care, other than the exposure or intervention of interest?

4* Was there a control group?

5* Were there multiple measurements of the outcome both pre- and post-intervention/exposure?

6* Was follow up complete and if not, were differences between groups in terms of their follow up adequately described and analysed?

7* Were the outcomes of participants included in any comparisons measured in the same way?

8* Were outcomes measured in a reliable way?

9* Was appropriate statistical analysis used?

Children and adolescents are at a significantly high risk of mental health problems during their lifetime, among which are depression and anxiety, which are the most common. Life skills education is one of the intervention programmes designed to improve mental well-being and strengthen their ability to cope with the daily stresses of life. This review aimed to identify and evaluate the effect of life skills intervention on the reduction of depression, anxiety and stress among children and adolescents. Following the Population, Intervention, Comparison and Outcome (PICO) model and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) 2009 checklist, eight databases (Academic Search Complete, CINAHL, Cochrane, MEDLINE, Psychology and Behavioural Sciences Collection, PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science) were systematically reviewed from 2012 to 2020. The search was limited to English papers only. It included published experimental and quasi-experimental studies addressing the effect of life skills interventions on the reduction of at least one of the following mental health disorders: depression, anxiety and stress among children and adolescents (from the age of 5 years old to 18 years old). We used the Joanna Briggs Institute checklist for experimental and quasi-experimental studies to evaluate the quality of the included studies. This study was registered in PROSPERO [CRD42021256603]. The search identified only 10 studies (three experimental and seven quasi-experimental) from 2,160 articles. The number of the participants was 6,714 aged between 10 years old and 19 years old. Three studies in this review focused on depression and anxiety, whereas one study investigated depression and the other anxiety. Three studies targeted only stress and two examined the three outcomes, namely, depression, anxiety and stress. Almost in all studies, the life skills intervention positively impacted mental disorders, considering the differences among males and females. The overall methodological quality of the findings was deemed to be moderate to high. Our results clearly indicated the advantages of life skills programmes among adolescents in different settings and contexts. Nonetheless, the results highlight some important policy implications by emphasising the crucial roles of developers and policymakers in the implementation of appropriate modules and activities. Further research examining life skills intervention with a cultural, gender perspective, age-appropriate and long-term effect is recommended.

Introduction

One of the growing public health issues among children and adolescents is mental disorders ( 1 ), which is recognised as a priority topic for more research and government intervention ( 2 ). It is estimated that 10% to 20% of children and adolescents globally have experienced mental health problems. Furthermore, a more significant proportion of mental health problems has been observed for specific subgroups of teenagers, those with socioeconomically disadvantaged positions and those who lack appropriate health or social services, are identified as minority ethnic groups and live in more rural or distant locations ( 2 – 4 ).

In Europe and the USA, mental illnesses account for most disability-adjusted life years among children between 5 years old and 14 years old ( 5 ). The findings from previous research indicated that anxiety and depression are common among children aged 8 years old–12 years old, with reported prevalence rates of approximately 2% and 5%, respectively ( 6 ). Moreover, adolescence is a sensitive and crucial stage for development from childhood to adulthood ( 7 ). Multiple physical, emotional and social changes occur during this formative time of adolescence ( 8 ). These changes can make adolescents vulnerable to mental health problems and nearly half of these problems begin before the age of 14 ( 9 ). Mental health conditions account for 16% of the global burden of disease and injury among adolescents ( 8 ). Furthermore, these problems have been demonstrated to increase the risk of adverse consequences, such as impairment, lack of productivity and ability to contribute to society, low educational performance and increased probability of exhibiting risky behaviours, such as alcoholism and sexual, and suicidal behaviours ( 10 ).

Anxiety and depression are the most prevalent mental health conditions during the early life ( 11 ). These disorders commonly emerge during childhood and adolescence but might continue until adulthood if left untreated. Depression and anxiety are the 4th and 9th leading causes of illness and disability in late-stage youth and the 15th and 6th in early-stage adolescents, respectively ( 12 ). Moreover, these disorders could have a long-term and repeating effect and are more likely to co-occur together up to 50% ( 4 , 11 ). Depression is the primary cause of disability-adjusted life years lost in teenagers worldwide. It occurs in 2%–8% of children and adolescents, with the highest prevalence during puberty. Of the affected individuals, around 40% experience repeated episodes and approximately 33% think about suicide, with 3% to 4% actually committing it ( 13 , 14 ).

Meanwhile, 1 in 10 young individuals suffers from anxiety disorders before reaching the age of 16 ( 15 ). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the prevalence of this disorder was between 5.7% and 17.7% in children and adolescents ( 16 ). Similarly, stress is a mental health condition that negatively impacts people’s lives. During adolescence, the susceptibility to stress is highly increased, adversely affecting individuals’ psychological and physical well-being ( 17 ).

Prevention is one strategy to reduce the burden of these illnesses, which can be categorised as either universal or targeted programmes ( 11 ). It is necessary to address these disorders by implementing educational programmes targeting diverse children and teenagers to introduce and reinforce essential knowledge and skills in mental well-being ( 18 ). School is a suitable atmosphere for targeting adolescents. It demonstrates the most effective social settings that can help students practice cognitive and social skills as they spend a significant amount of their time there. Furthermore, it offers intervention opportunities with the support of social relationships. School-based mental health programmes can reduce and alleviate many common barriers to treatment in the community, such as cost, location, time, transportation and stigmatisation, by offering alternatives that are of low cost, have high utilisation levels, are convenient and non-threatening ( 19 , 11 , 20 , 21 ). School plays a vital role in identifying those with symptomatic and those at risk of becoming symptomatic ( 11 ).

Life skills education is an organised educational programme designed to improve children and adolescents’ skills and abilities, enabling them to deal more effectively with the daily demands of life ( 22 , 23 ). It also aims to improve mental health and boost the positive and adaptive behaviours of the target individuals ( 24 ). According to the WHO, life skills are generally defined as ‘abilities for adaptive and positive behaviour that enables individuals to deal effectively with the demands and challenges of everyday life’ ( 25 ). The theoretical foundation of the life skills programme is based on the social learning theory developed by Albert Bandura in 1977 ( 24 , 25 ). He stated that people learn through observational learning, imitation and modelling. Bandura introduced the term ‘observational learning’ and defined the components of appropriate observational learning as attention, retention, reproduction and motivation ( Figure 1 ).

Schematic outline of observational learning and modelling process in social learning theory

Source : Nabavi ( 27 )

He posited that individuals observe and copy the behaviour of others in their social worlds and develop an idea of how new actions are performed. This recorded information serves as a guide for action on subsequent occasions. His explanation on observational learning enables an individual to rapidly gather knowledge by observing and imitating models found in his/her environment. Then, in 1986, Bandura highlighted the cognitive aspects of observational learning, and manner, behaviour, cognition and environment interact to shape individuals. He introduced the principle of the dynamic and reciprocal relationship between a person (an individual with a collection of previous experiences), their environment (the external social circumstances) and their behaviour (responses to stimuli to achieve goals) ( 26 – 28 ).

Life skills education includes activities that support critical and creative thinking, coping with emotions and stress, self-awareness and empathy, decision-making and problem-solving, communication skills and interpersonal relations ( 25 ). Life skills education has been used in different countries and targets different health outcomes, such as improvement and promotion of mental ( 25 , 29 ), psychosocial ( 30 ), and physical health and prevention of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome AIDS ( 31 ), substance abuse ( 32 ) and teenage pregnancy ( 22 , 33 ). Thus, life skills education has been established for preventive measures, promoting healthy positive behaviour, and strengthening communication and socialisation skills.

Therefore, this systematic review aimed to provide an overview and summarise the available literature about the effect of life skills programmes on the reduction of depression, anxiety and stress among children and adolescents. In addition, it would provide good insight into the appropriate approach for implementing the accurate methods. Following the PICO model, the main review question of the current systematic review is as follows: What is the effect of life skills intervention on depression, anxiety and stress levels among children and adolescents (5 years old–18 years old of age)?

The current systematic review and the bibliometric study were conducted by following the ‘PRISMA’ 2009 checklist ( 34 ). The protocol of this systematic review was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (registration number: CRD42021256603).

Literature Search and Eligibility Criteria

A comprehensive search was initially conducted on eight electronic databases, namely, Academic Search Complete, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, Psychology and Behavioural Sciences Collection, PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science. The following keywords were used in the search: Population: (Children OR child OR adolescents OR youth OR young OR teen OR teenage OR young people OR young adult), Intervention: AND (‘life skills’), Outcome: AND (‘mental disorders’ OR ‘mental health’ OR ‘internalising problems’ OR ‘emotional problems’ OR ‘anxiety disorders’ OR ‘depressive disorders’ OR ‘depression’ OR ‘stress’ OR ‘anxiety’ OR ‘Psychological stress’ OR ‘Life Stress’ OR ‘emotional stress’). Only databases from 2012 to 2020 were searched. The literature was limited to the English language due to the expected translation problem. The detailed search strategy of the electronic databases is illustrated in the supplementary table (Table S1) .

The inclusion criteria were as follows: i) participants were children or adolescents with ages between 5 years old and 18 years old; ii) intervention was the life skills programme; iii) life skills intervention groups compared with either school-as usual control groups, waitlist control groups or other educational interventions or no control groups; iv) the studies reported at least one mental health outcome, either depression, anxiety and stress, at baseline and post-intervention at a minimum; v) randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and non-randomised controlled trials (non-RCT), such as quasi-experimental and pre-post studies design. Studies were excluded if: i) the studies evaluated drug and alcohol use, physical and sexual activities, and nutritional interventions; ii) non-English studies and iii) non-experimental studies, such as observational (e.g. cross-sectional, case-control and cohort studies) and qualitative ones.

Data Collection and Analysis

All citations were uploaded into the Mendeley software and duplicated studies were removed. Two reviewers screened the titles, abstracts, and, finally, full texts based on the inclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved through a discussion between the two reviewers. If the disagreement remained, a third person was available to arbitrate.

Data Extraction and Management

Two reviewers independently collected the standardised data extraction forms. The information extracted included the following: first author, year of publication, country, study design (RCT or non-RCT), participant’s age, sample size, instrument, intervention characteristics and findings.

Quality Appraisal

Two independent reviewers used the Critical Appraisal Checklist for RCTs and Quasi-Experimental studies developed by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) ( 35 ) to evaluate the risk of bias for the eligible studies. In addition, they calculated the overall risk score based on the number of items checked for each evaluation. The purpose of this appraisal was to assess the methodological quality and determine the possibility of bias in the study design, conduct and analysis. Any disagreement between the reviewers was addressed by discussion.

The instruments consisted of 13 and 9 questions for the RCTs checklist and the quasi-experimental checklist, respectively. These questions were answerable by ‘yes,’ ‘no,’ ‘unclear,’ or ‘not applicable.’ The appraisal score represented the percentage of (yes) responses from the total number of questions. At least 50% of the ‘yes’ scores on the JBI critical evaluation instruments were used as the cut-off point for inclusion in the RCT and quasi-experimental trial review ( 36 ). When a criterion was ‘not reported,’ it was considered as ‘unclear’ and treated as a ‘no’ response. If a measure did not apply (N/A) to the study, that item was not counted in the total number of criteria ( 37 ).

Study Selection

According to the PRISMA diagram ( Figure 2 ), a total of 2,160 articles were identified in the initial database search. After removing the duplicates, 1,231 articles were further examined, of which 1,136 were excluded during the title and abstract screening. A total of 18 full-text articles were left for eligibility assessment. Finally, 10 articles were found to meet the eligibility criteria.

Prisma flow diagram of the selected articles

Study Characteristics

Detailed information about the authors, year of publication, countries, study design, sample size, participants, instrument, intervention characteristics, findings and summary of the results is provided in Table 1 . The studies included in the review were seven quasi-experimental ones and three were RCTs. All the included studies were conducted in seven different countries: one study in Malaysia ( 29 ); one study in Taiwan ( 38 ); three studies in Iran ( 39 – 41 ); two studies in India ( 42 , 43 ); one study in Uganda ( 44 ); one study in Kenya ( 45 ) and one study in Australia ( 46 ).

Study characteristics

| Authors, year | Country | Design | Participants characteristics/Sample size | Setting | Trainer | Methodological quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mohammadzadeh et al., 2019 ( ) | Malaysia | RCT | 271 male and female adolescents (13 years old– 18 years old) | Orphanages | Researcher | High (85%) |

| Lee et al., 2020 ( ) | Taiwan | RCT | 2,522 students with age 10-year-old to 12-year-old | School | Teacher | Moderate (62%) |

| Jamali et al., 2016 ( ) | Iran | Experimental (pre-post-tests) and control group | 100 students, aged 13 years old –14 years old | School | Qualified trainers | Moderate (69%) |

| Yankey and Urmi, 2012 ( ) | India | A quasi-experimental study | 600 Tibetan adolescents aged 13 years old– 19 years old | School | Researcher | High (100%) |

| McMullen and McMullen, 2018 ( ) | Uganda | Experimental study (pre-post-tests) and control group | 620 students aged 13 years old –18 years old at the baseline and 170 students at post-intervention ‘at 1 year’ were participated | School | Teachers | High (88%) |

| Roy et al., 2016 ( ) | India | Intervention study (pre-post-follow up) | 42 adolescent boys, mean age (SD) 14.38 (1.05) years old | School | Researcher | Moderate (66%) |

| Ndetei et al., 2019 ( ) | Kenya | Intervention (pre-post-follow up) | 2,273 students at baseline, and only 1,075 complete the questionnaire for 9 months. Age from 11 years old to 18 years old | School | Trained teachers | Moderate (77%) |

| Mohammadi and Poursaberi, 2018 ( ) | Iran | A quasi-experimental study | 120 Iranian adolescent cancer patients, aged 9 years old–18 years old | Hospital | Clinical psychologist | Moderate (77%) |

| Eslami et al., 2016 ( ) | Iran | A quasi-experimental study | 126 female students, the mean age group was 16 years old | School | Researcher | High (100%) |

| McMahon and Stephanie, 2020 ( ) | Australia | Experimental (pre-post-tests) and control group | 40 students aged from 16 years old to 17 years old | School | Teacher | High (88%) |

Participants’ Characteristics

The total number of participants in the included studies was 6,714 with varying sample sizes from 40 adolescents in Australia ( 46 ) to 2,522 in Taiwan ( 38 ). Most studies recruited individuals from schools, one in Malaysia from orphanages ( 29 ) and one in Iran from paediatric hospitals ( 40 ). The age range in all studies was 10 years old–19 years old; however, no research was conducted among children. Both gender, males and females, participated in most studies, only one study was conducted among boys ( 43 ) and another one among girls ( 41 ).

Intervention Characteristics

All studies in this review investigated the effect of life skills intervention on the reduction of depression, anxiety and stress among adolescents ( Table 2 ). Three studies targeted only stress ( 39 , 42 , 43 ), and one study each targeted depression ( 38 ) and anxiety ( 46 ). Meanwhile, three other studies focused on depression and anxiety-like symptoms ( 40 , 44 , 45 ), and the last two targeted three mental conditions, namely, depression, anxiety and stress, altogether ( 29 , 41 ). Baseline assessment was performed for all the participants and the findings were compared with the post-intervention results, except for one study, which did not include pre-intervention evaluation ( 38 ). The period of post-intervention assessment differed in the included studies, ranging from immediately after the intervention to 9 months ( 45 ) and 1 year ( 43 ). In a study by Lee et al. ( 38 ), there were no follow-ups, only post-test assessments. Detailed information and a summary of the intervention assessment and follow-up are presented in Table 2 . Four studies evaluated the effect of the intervention by comparing the intervention and control groups; only one study had no control group ( 45 ). The intervention programme was conducted by the researcher in most of the included studies.

Study instrument and findings

| Authors, year | Instrument/Psychometric properties | Data collection period | Intervention characteristics | Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mohammadzadeh et al., 2019 ( ) | Validated Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21), with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for depression = 0.81, anxiety = 0.79 and stress = 0.81 | 20 activities were conducted by the researcher, twice weekly for 2 h to 2½ h per session in the Malay language | The mean scores of depressions, anxiety, stress was significantly decreased compared to the pre-test scores for depression ( = 33.80; < 0.001; η = 0.11), for anxiety ( = 6.28; = 0.01; η = 0.02), stress ( = 32.05; < 0.001; η = 0.11) | |

| Lee et al., 2020 ( ) | Center for epidemiologic studies depression scale for children (CESDC), with Cronbach alpha, was 0.85 | 27 class sessions were conducted for 45 min by the teacher | Life skills was associated with reduction of depressive symptoms among males but not females. Boys in the Life Skills group had significantly lower total CESDC scores and lower depressed affect scores (M = 10.49, SD = 7.47; M = 2.14, SD = 3.43, respectively) than those in the education as usual group (M = 11.64, SD = 9.14; M = 2.71, SD = 4.37, respectively) | |

| Jamali et al., 2016 ( ) | Validated stress questionnaire (based on Kettle personality scale), with Cronbach’s alpha for stress (α = 0.76) | Qualified trainers provided eight sessions (two sessions a week for 2 h) to the intervention group for 1 month | The mean scores of the stress factor in the intervention group (18.48) and control group (22.18) was statistically significant, (2, 97) = 6.15, < 0.001, η = 0.113 | |

| Yankey and Urmi, 2012 ( ) | The Problem Questionnaire for stress, with reliability (Cronbach alpha = 0.83) and validity (from 0.18 to 0.45) | 30 basic sessions and 15 additional sessions for students who were not able to comprehend life skills in one session. Follow up assessments were done 2 weeks post-intervention | Life skills have significantly contributed to reducing stress related to school, leisure and self among Tibetan adolescents. School stress for the experimental group was significantly lower (M = 20.84, SD = 4.92) as compared to the control group (M = 22.64, SD = 5.34) in the post-intervention scores | |

| McMullen and McMullen, 2018 ( ) | The African Youth Psychosocial Assessment Instrument (AYPA) for ‘depression/anxiety-like symptoms, with Cronbach’s alpha (α = 0.86) | There were around 24 lessons conducted by teachers for 45 min–60 min | The intervention group had a significant reduction in internalising problems (depression/anxiety-like symptoms), (1,167) = 11.14, = 0.001, η = 0.063 | |

| Roy et al., 2016 ( ) | Manipal Stress Questionnaire (MSQ), psychometric property was not documented | Validated 7 days sessions programme. The programme was conducted for 50 min–60 min | The mean stress scores among adolescents who underwent the intervention program reduced significantly from 133 to 116 after 1 month and to 117 after 3 months follow up ( < 0.05) | |

| Ndetei et al., 2019 ( ) | Youth self-report (YSR), with (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.82) and high test-retest reliably ( = 0.88) | The training session was done at 8 h for 4 weeks with all schools | Life Skill intervention was significantly improving in the internalising YSR symptoms. There was an overall decrease in the internalising problems from 36.8% to 7.3%. AOR = 0.12; 95% CI: 0.09, 0.16. Better outcomes among girls than boys, rural region than urban, and in upper classes than in lower | |

| Mohammadi and Poursaberi, 2018 ( ) | The General Health Questionnaire (GHQ), with (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.90) | A clinical psychologist provided 13 training sessions for 45 min | The mean score of depressions, anxiety was decreased significantly after the training program, the anxiety score in the intervention group was M(SD) = 6.61 (2.62), compared to the control group M(SD)= 10.33 (2.37). While the depression score was 11.05 (2.84) for the intervention and 15.95 (2.33) for the control group | |

| Eslami et al., 2016 ( ) | Depression anxiety stress scales (DASS-21), with validity and reliability, were confirmed | Eight sessions for 45 min were conducted by the researcher for 3 months | The results revealed a significant decrease in the level of anxiety and stress in the experimental group as compared to the control group after 2 months of the intervention ( < 0.001). However, there was no significant difference in the depression score in the intervention group immediately and 2 months post-intervention ( < 0.09) | |

| McMahon and Stephanie, 2020 ( ) | The Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS), with Cronbach’s alpha (α = 0.82) | 10-session life skills programme with 2 h for 2 weeks was provided by the teacher | The result showed a significant decrease in social anxiety, Wilk’s Lamda = 0.84, ( , ) = 5.07; = 0.03, partial = 0.16 among the experimental group compared to the control group |

Meanwhile, the trained teachers conducted the programme in other studies and only one study was performed by a clinical psychologist ( 40 ). The length and contents of the intervention were also different from one study to another. The overall duration of the intervention ranged from 1 week to months and the length for each session ranged from 45 min to 150 min. The education modules were slightly different among the included studies. They used various activities such as brainstorming, goal-setting, role-playing and group discussion, drama, drawing, playing games and matches, and question-and-answer sessions.

As presented in Table 1 , the appraisal score for the methodological quality (in percentage) of the included studies ranged from moderate (62%) to high (100%), where high quality was regarded as more than 80%, moderate quality as 50% to 79% and poor quality as less than 50% ( 37 ). Half of the studies were of moderate quality, whereas the rest were considered to be of high quality. The comprehensive data on the methodological quality of the included studies are presented in the supplementary tables (Tables S2 and S3 ).

In this systematic review, we identified and summarised the effect of life skills intervention on depression and/or anxiety and/or stress among children and adolescents. The study demonstrated that the life skills intervention positively influenced the adolescents’ mental health. It also provided evidence supporting the development and establishment of life skills interventions. Our findings are consistent with those of previous research, indicating the efficiency and effectiveness of educational programmes and mental health interventions ( 18 , 29 , 11 , 47 – 49 ).

Several aspects of the effect of life skills programmes are highlighted in this review. For instance, the life skills intervention is based on three critical key elements, namely, appropriate educational strategies, active educational techniques and safe learning environments. Furthermore, the link between theoretical and practical aspects is one of the essential educational strategies. Four articles in this review mentioned the life skills intervention-based theories: stress-coping theory ( 29 ), social cognitive theory ( 45 ) and self-determinant theory ( 46 ). The teaching and learning approaches are situated at the junction of the conceptual and programmatic frameworks for life skills. Life skills education is also focused on two main aspects. First, life skills are changeable; they are not permanent character traits and may thus be taught, learned and acquired throughout life. Second, they can be reinforced through proper educational interventions. In this sense, because teaching and learning are integral components of life skills, a fundamental practical aspect of life skills programmes is the determination of the most effective teaching and learning methods.

In addition, active learning is the most effective method for delivering life skills education. It includes a learner-focused approach that places importance on the teaching and learning process. Active learning methods encourage students to become active participants in their education rather than becoming passive information users. Students are considered as active thinkers who may be stimulated by engaging in instructional approaches. They work with other students to improve their talents and, as a result, form strong bonds with their classmates. It is also critical to consider children and youth’s perspectives, ideas, and concerns while assuring their active involvement in educational activities. Another vital component of participatory education, small group and teamwork have several benefits for successful life skills education.

More insight into the importance of schools as safe environments can contribute to the success of life skills intervention and can help create an excellent ground for teachers and peer relationships. Schools are ideal environments for interventional and training studies on children and adolescents because of easy access to many participants, a high degree of confidence among parents and the community, and the possibility to evaluate the short- and long-term impact of the studies ( 11 , 19 – 21 ). Consequently, incorporating life skills training as part of the school curriculum at early stages is also necessary. It can facilitate the early recognition of students experiencing problems with their emotional health and well-being as well as the referral to appropriate support.

Our results contributed to this field of study by emphasising the critical components of success among teenagers that reflect numerous aspects of other mental health outcomes. Life skills interventions promote positive mental health and encourage teenagers with essential skills to improve their abilities and overcome challenges ( 50 ). Moreover, it plays a significant role in enhancing students’ success in both academic and non-academic areas ( 40 ), such as strengthening of coping mechanisms ( 29 ) and development of self-confidence ( 30 , 40 ) and empathy ( 51 ). Accordingly, good mental health and well-being influence healthy behaviours, improved physical health, high educational achievement, high productivity, jobs and income. Eventually, teenagers show positive changes from the knowledge gained about the different coping strategies and life skills ( 38 , 52 ).

Although the duration of the life skills programmes appeared different in this review, its effect on the studied variables was achieved. The priority was focused on the intensity of the sessions and the quality of the presented material, instead of the number of sessions. Most of the included studies were limited to the documentation of short-term effects obtained through methodologies with small sample sizes; in addition, they were restricted to pre-post-test assessments, without any follow-up, to fully evaluate the effectiveness of the respective activities. These findings indicate the need for additional research to fully evaluate the respective programme’s performance. Furthermore, long-term monitoring and assessment are required to construct empirical evidence with regard to the success of life skills interventions ( 6 ). Regular booster sessions and reinforcement must also be considered for the maintenance of mental health well-being.

Thus, the implementation of sustainable life skills programmes is a crucial element. As a result, greater focus is needed in these situations on the establishment of continuous and sustainable programmes through systematic planning, organisation, supervision and assessment of teaching these skills ( 22 , 53 ). The use of an appropriate instrument for the assessment of outcomes can help in the production of high-quality results. Although various tools have been used to evaluate and measure depression, anxiety and stress, they are suitable for children and adolescents. The validity and reliability of the rating scales were documented in most of the included studies, validating the quality of the studies.

Life skills programme mentors, policymakers, officials and instructors must understand its potential and worth and receive adequate training ( 19 , 54 , 55 ). In this setting, increasing access to appropriate interventions is necessary, especially those provided by non-healthcare professionals, such as teachers and caregivers.

Considering adolescent experiences in the context of an individual’s tradition and culture is crucial for comprehending how individuals from varied backgrounds acquire life skills knowledge. This may include student comments and discussions on each life skills issue to enhance the applicability of the skills ( 24 , 25 ). Studies might be described in terms of experiences, such as stories from teenagers’ lives, examination of different perspectives and the distinct social circumstances in which they acquire life skills. These perspectives will create a more balanced understanding of the realities of programme effectiveness.

Furthermore, it can be noticed that in the included studies, life skills education has been integrated into particular social and cultural contexts. For instance, in the Malaysian research ( 29 ), the programme was conducted in orphanages in the Malay language and targeted the Malaysian environment and local culture, with respect to ethnicity and religion. Meanwhile, in Taiwanese schools ( 38 ), the curriculum was translated to Mandarin’s local language. It was modified and changed using Taiwanese life-experience situations to ensure that it was known to Taiwanese students and practical in a school and classroom setting. Moreover, they used the most conventional social media application in Taiwan for further discussion.

In the Tibetan study ( 42 ), the programme was also constructed for Tibetan refugee teenagers by making the life skills activities realistic and relevant to the refugee experience. The names of characters and locations have been changed and replaced to reflect the situation of Tibetan refugee youths. In Uganda ( 44 ), Kenya ( 45 ), Australia ( 46 ) and Iran ( 40 ), the activities were designed based on the particular psychological needs of the students’ skills. The objective was to create a curriculum suited for those participants’ cultural and social contexts. Here, it can be noticed that the basic concept of life skills intervention is the same across different countries. Moreover, these skills were contextualised according to the social and cultural context and settings. Therefore, certified trainers who customise the curriculum with more appropriate examples and real-life situations closer to the user’s background would make the life skills programme more effective and impactful.

Another important finding in our review is the lack of life skills intervention studies among children due to several reasons. First, the prevalence of mental disorders peaks during adolescence. It is a transitional stage characterised by rapid growth and development with the occurrence of numerous physical and psychological changes, such as increased susceptibility to stressors and the emergence of many mental health disorders ( 14 , 17 , 56 , 57 ). Also, previous literature documented that the symptoms of these mental disorders persist throughout childhood; thus, it is not common for intervention programmes to focus on children ( 6 ). Furthermore, the limited search on the database might lead to missing relevant articles before 2012 and those in non-English languages. Finally, we excluded different study designs that target children, such as the mixed-method design.

Gender disparity in the interpretation of mental illness is reported in this review. For example, symptoms of depression were lesser in males but not in females after the life skills intervention. Similarly, previous literature documented the presence of gender inequality in adolescents who experienced internalising and externalising problems. Females tended to have higher levels of internalising problems, whereas males tended to have higher levels of externalising problems ( 58 ). Females generally showed more emotional reactions to stressful situations, whereas males exhibited more cognitive responses ( 59 , 49 ). This could mean that females are more susceptible to the risk factors owing to their biological differences ( 29 ).

Meanwhile, males were observed to practice more skills than females and regulate their emotional symptoms better than females. In addition, females used social support as a coping method, even though it has been observed that females who sought social support were more likely to experience mental health issues, but not males ( 60 ). Consequently, more advanced research focusing on gender variation and how various life skills interventions impact these populations is needed. Such an effort could help promote dedicated sections where males and females could be separately addressed.

Addressing the concerns and challenges faced by children and young adults in early life through education programmes could make them independent in coping with life’s demands, which can transform these challenges and obstacles into opportunities. In addition, the cultural and sustainable development of the programme is crucial, which involves indigenous individuals as consultants and local assistants in policymaking. It will contribute to sociocultural awareness, decreasing the possibility of inappropriate implementation.

Although a comprehensive search using eight databases was performed to obtain an enormous number of studies, our systematic review has several limitations. Our search was limited to articles published between 2012 and 2020. Furthermore, it did not include non-English articles and gray literature; thus, it is possible that some relevant studies have been missed. Furthermore, some of the studies that involved multicomponent interventions were not included, making narrative synthesis and interpretation of the evidence challenging. Lastly, the differences in the study population, location, sample size, study length and instruments across the included studies make it difficult to effectively compare the intervention.

This review has synthesised evidence on life skills intervention to improve the mental health of adolescents. It identifies several experimental and quasi-experimental studies that evaluated life skills programmes as a potential intervention strategy for effectively addressing teenagers’ mental well-being through the reduction of depression, anxiety and stress. The methods used by adolescents to acquire information and skills through life skills programmes and then to adopt good attitudes and behaviours were explained in almost all studies.

Life skills education was focused on specific life skills, depending on the setting. It considered psychosocial competencies and interpersonal skills that help participants in making the right decisions, solving problems, thinking critically and creatively, communicating effectively, building healthy relationships, empathising with others, and coping with managing their lives in a healthy and productive manner.

The current research has resulted in numerous critical recommendations on the development of life skills educational interventions. First, life skills development is at the core of childhood and adolescence protection strategies. Future research is recommended to holistically examine life skills educational intervention to provide robust evidence on its effectiveness and to achieve long-term effects.

In addition, a comprehensive approach with a cultural, gender perspective, age-appropriate and active learning should be considered. Based on the evidence in this review, policymakers, officials and health professionals are suggested to offer life skills training programmes to all children and adolescents in schools and institutions. In addition, it could benefit from providing resources using internet applications to enable fast and easy access to information.

Supplementary 1

Search strategy for databases

- The electronic databases were initially searched.

- They were Academic Search Complete, CINAHL, Cochrane, MEDLINE, Psychology and Behavioural Sciences Collection, PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science.

The title and abstract of articles searched using several keywords are as follows:

- Population: (Children OR child OR adolescents OR youth OR young OR teen OR teenage OR young people OR young adult),

- Intervention: AND (‘life skills’),

- Outcome: AND (‘mental disorders’ OR ‘mental health’ OR ‘internalising problems’ OR ‘emotional problems’ OR ‘anxiety disorders’ OR ‘depressive disorders’ OR ‘depression’ OR ‘stress’ OR ‘anxiety’ OR ‘Psychological stress’ OR ‘Life Stress’ OR ‘emotional stress’).

The literature was limited to the English language because of the expected translation problem.

Supplementary 2

Acknowledgements.

We would like to thank the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Putra Malaysia for their librarian support.

Conflict of Interest

Authors’ Contributions

Conception and design: YS, AZFA, HA

Analysis and interpretation of the data: YS, AZFA, HA

Drafting of the article: YS, AZFA, MM

Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content: YS, AZFA, HA, SAM, MM, ASA

Final approval of the article: AZFA, HA, SAM, MM, ASA

Provision of study materials or patients: YS

Administrative, technical or logistic support: MM, ASA

Collection and assembly of data: YS

Life Skills Education

Helping people make responsible and informed choices.

For youth to grow into well-functioning adults, it is essential that they learn key life skills such as critical and creative thinking, decision-making, and effective communication, as well as skills for developing self esteem and healthy relationships, navigating harmful gender norms, and accessing health care. While important for all young people around the world , these skills are particularly critical for adolescents who lack accurate information and guidance for making consequential decisions such as becoming sexually active, staying in school, and preventing or responding to abuse. Many children, however, do not have access to education that includes life skills training.

We layer life skills education onto many of our programs for young people, and deliver these in club-like settings in and out of school, as well as through national school curricula.

We also work with partners, including ministries of education, schools, and nongovernmental organizations, to develop life skills curricula and training approaches and help programs integrate and teach life skills to students in both formal schools and non-formal settings.

Our life skills education approach makes curricula more relevant to the needs of all youth and vulnerable adults, whose grasp of learning content increases dramatically when it is linked directly to their everyday lives. Learners acquire a range of skills to live effectively in society, as well as specific technical and occupational skills including how to set up and run small businesses and use sustainable agriculture methods.

Healthier children stay in school longer, learn more, and as a result, become more productive adults. We are committed to developing and scaling programs that meet the various health needs of children and their families.

We build on school curricula to inform students about their health and remove barriers to health services. We help ministries of education develop HIV prevention and life skills education curricula. We use schools as entry points to deliver integrated services including primary health care screening and referrals; reproductive health information; nutrition; and psychosocial support .

The use of clean cooking technology is critical to health. We implement activities in school kitchens to improve staff health and reduce the environmental consequences of traditional wood- and coal-burning stoves. We train students in clean cookstove technology so they can apply what they learn at home, thus improving the environment and the health of their families and communities.

View All Projects

Published in: {{resource.funding_source}}

Published in: {{resource.journal_article_info.JOURNAL_NAME}} {{resource.journal_article_info.JOURNAL_NAME}}

NEWS & STORIES

View related news.

Navigating HIV with a Social Worker's Compassion

The Power of Youth-led Action Research in Improving Climate Education and Action

Siyakha Plus: Building Economic Opportunities and Improving HIV Outcomes for Young Mothers and their Children in Mozambique

Partner with us.

World Education strives to build lasting relationships with partners across diverse geographic regions and technical sectors to produce better education outcomes for all.

Subscribe To Our Newsletter

Email Please leave this field empty.

Check out our past newsletters .

- Privacy Overview

- Strictly Necessary Cookies

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognizing you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Strictly Necessary Cookie should be enabled at all times so that we can save your preferences for cookie settings.

If you disable this cookie, we will not be able to save your preferences. This means that every time you visit this website you will need to enable or disable cookies again.

Skills for health : skills-based health education including life skills : an important component of a child-friendly/health-promoting school

| Title | Skills for health : skills-based health education including life skills : an important component of a child-friendly/health-promoting school |

| Publication Type | Book |

| Year of Publication | 2003 |

| Authors | |

| Secondary Title | WHO information series on school health |

| Volume | no. 9 |

| Pagination | v, 83 p. : boxes, fig. |

| Date Published | 2003-01-01 |

| Publisher | World Health Organization (WHO) |

| Place Published | Geneva, Switzerland |

| ISSN Number | 924159103X |

| Keywords | , , , , , |

| Abstract | Skills-based health education is an approach to creating or maintaining healthy lifestyles and conditions through the development of knowledge, attitudes, and especially skills, using a variety of learning experiences, with an emphasis on participatory methods. |

| Notes | Bibliography: p. 75-83 |

| Custom 1 | 132, 144 |

The copyright of the documents on this site remains with the original publishers. The documents may therefore not be redistributed commercially without the permission of the original publishers.

PDF [413 KB]

Www download document [413 kb].

- Fact sheets

- Facts in pictures

- Publications

- Questions and answers

- Tools and toolkits

- HIV and AIDS

- Hypertension

- Mental disorders

- Top 10 causes of death

- All countries

- Eastern Mediterranean

- South-East Asia

- Western Pacific

- Data by country

- Country presence

- Country strengthening

- Country cooperation strategies

- News releases

- Feature stories

- Press conferences

- Commentaries

- Photo library

- Afghanistan

- Cholera

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Greater Horn of Africa

- Israel and occupied Palestinian territory

- Disease Outbreak News

- Situation reports

- Weekly Epidemiological Record

- Surveillance

- Health emergency appeal

- International Health Regulations

- Independent Oversight and Advisory Committee

- Classifications

- Data collections

- Global Health Estimates

- Mortality Database

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Health Inequality Monitor

- Global Progress

- Data collection tools

- Global Health Observatory

- Insights and visualizations

- COVID excess deaths

- World Health Statistics

- Partnerships

- Committees and advisory groups

- Collaborating centres

- Technical teams

- Organizational structure

- Initiatives

- General Programme of Work

- WHO Academy

- Investment case

- WHO Foundation

- External audit

- Financial statements

- Internal audit and investigations

- Programme Budget

- Results reports

- Governing bodies

- World Health Assembly

- Executive Board

- Member States Portal

- Publications /

Life Skills Education School Handbook - Noncommunicable Diseases: Introduction

Health promoting schools has been recognized an effective approach to enhancing education and health outcomes of children and adolescents. This handbook deals with the prevention of noncommunicable diseases in school settings. The first part of the handbook presents the knowledge around risks linked to tobacco use, unhealthy diet, lack of physical activity and hygiene including oral. it highlights the need to address these risk factors trough health literacy and life skills education.

Why Education Matters to Health: Exploring the Causes

Americans with more education live longer, healthier lives than those with fewer years of schooling (see issue brief #1) . but why does education matter so much to health the links are complex—and tied closely to income and to the skills and opportunities that people have to lead healthy lives in their communities..

How are health and education linked? There are three main connections: 1

- Education can create opportunities for better health

- Poor health can put educational attainment at risk (reverse causality)

- Conditions throughout people’s lives—beginning in early childhood—can affect both health and education

The relationship between education and health has existed for generations, despite dramatic improvements in medical care and public health. Recent data show that the association between education and health has grown dramatically in the last four decades. Now more than ever, people who have not graduated high school are more likely to report being in fair or poor health compared to college graduates. 2 Between 1972 and 2004, the gap between these two groups grew from 23 percentage points to 36 percentage points among non-Hispanic whites age 40 to 64. African-Americans experienced a comparable widening in the health gap by education during this time period. The probability of having major chronic conditions also increased more among the least educated. 3 The widening of the gap has occurred across the country 4 and is discussed in more detail in Issue Brief #1 .

How important are years of school? Research has focused on the number of years of school students complete, largely because there are fewer data available on other aspects of education that are also important. It’s not just the diploma: education is important in building knowledge and developing literacy, thinking and problem-solving skills, and character traits. Our community research team noted that early childhood education and youth development are also important to the relationship between education and health.

This issue brief, created with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, provides an overview of what research shows about the links between education and health alongside the perspectives of residents of a disadvantaged urban community in Richmond, Virginia. These community researchers, members of our partnership, collaborate regularly with the Center on Society and Health’s research and policy activities to help us more fully understand the “real life” connections between community life and health outcomes.

1. The Health Benefits of Education

Income and resources.

“Being educated now means getting better employment, teaching our kids to be successful and just making a difference in, just in everyday life.” —Brenda

Better jobs: In today’s knowledge economy, an applicant with more education is more likely to be employed and land a job that provides health-promoting benefits such as health insurance, paid leave, and retirement. 5 Conversely, people with less education are more likely to work in high-risk occupations with few benefits.

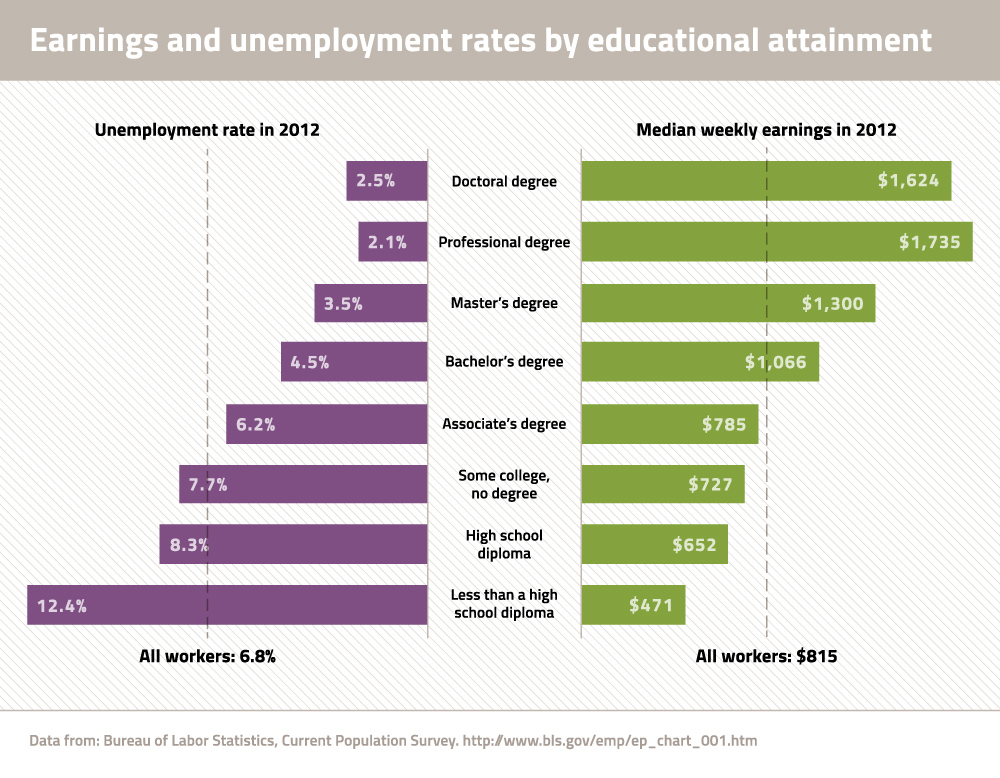

Higher earnings: Income has a major effect on health and workers with more education tend to earn more money. 2 In 2012, the median wage for college graduates was more than twice that of high school dropouts and more than one and a half times higher than that of high school graduates. 6 Read More

Adults with more education tend to experience less economic hardship, attain greater job prestige and social rank, and enjoy greater access to resources that contribute to better health. A number of studies have suggested that income is among the main reasons for the superior health of people with an advanced education. 1 Weekly earnings rise dramatically for Americans with a college or advanced degree. A higher education has an even greater effect on lifetime earnings (see Figure 1), a pattern that is true for men and women, for blacks and whites, and for Hispanics and non-Hispanics. For example, based on 2006-2008 data, the lifetime earnings of a Hispanic male are $870,275 for those with less than a 9th grade education but $2,777,200 for those with a doctoral degree. The corresponding lifetime earnings for a non-Hispanic white male are $1,056,523 and $3,403,123. 7

“Definitely having a good education and a good paying job can relieve a lot of mental stress.” —Chimere

Resources for good health: Families with higher incomes can more easily purchase healthy foods, have time to exercise regularly, and pay for health services and transportation. Conversely, the job insecurity, low wages, and lack of assets associated with less education can make individuals and families more vulnerable during hard times—which can lead to poor nutrition, unstable housing, and unmet medical needs. Read More

Economic hardships can harm health and family relationships, 8 as well as making it more difficult to afford household expenses, from utility bills to medical costs. People living in households with higher incomes—who tend to have more education—are more likely to be covered by health insurance (see Figure 3). Over time, the insured rate has decreased for Americans without a high school education (see Figure 4).

Lower income and lack of adequate insurance coverage are barriers to meeting health care needs. In 2010, more than one in four (27%) adults who lacked a high school education reported being unable to see a doctor due to cost, compared to less than one in five (18%) high school graduates and less than one in 10 (8%) college graduates. 9 Access to care also affects receipt of preventive services and care for chronic diseases. The CDC reports, for example, that about 49% of adults age 50-75 with some high school education were up-to-date with colorectal cancer screening in 2010, compared to 59% of high school graduates and 72% of college graduates. 10

Social and Psychological Benefits

“So through school, we learn how to socially engage with other classmates. We learn how to engage with our teachers. How we speak to others and how we allow that to grow as we get older allows us to learn how to ask those questions when we're working within the healthcare system, when we're working with our doctor to understand what is going on with us.” —Chanel

Reduced stress: People with more education—and thus higher incomes—are often spared the health-harming stresses that accompany prolonged social and economic hardship. Those with less education often have fewer resources (e.g., social support, sense of control over life, and high self-esteem) to buffer the effects of stress. Read More

Life changes, traumas, chronic strain, and discrimination can cause health-harming stress. Economic hardship and other stressors can have a cumulative, negative effect on health over time and may, in turn, make individuals more sensitive to further stressors. Researchers have coined the term “allostatic load” to refer to the effects of chronic exposure to physiological stress responses. Exposure to high allostatic load over time may predispose individuals to diseases such as asthma, cardiovascular disease, gastrointestinal disease, and infections 11 and has been associated with higher death rates among older adults. 12

Social and psychological skills: Education in school and other learning opportunities outside the classroom build skills and foster traits that are important throughout life and may be important to health, such as conscientiousness, perseverance, a sense of personal control, flexibility, the capacity for negotiation, and the ability to form relationships and establish social networks. These skills can help with a variety of life’s challenges—from work to family life—and with managing one’s health and navigating the health care system. Read More

Many types of skills can be developed through education, from cognitive skills to problem solving to fostering key personality traits. Education can increase ‘learned effectiveness,’ including cognitive ability, self-control, and problem solving. 13 Personality traits, otherwise known as ‘soft skills’, are associated with success in education and employment and lower mortality rates. 14 One set of these personality traits has been called the ‘Big Five’: conscientiousness, openness to experience, being extraverted, being agreeable, andemotional stability. 15

These various forms of human capital are an important way that education affects health. For example, education may strengthen coping skills that reduce the damage of stress. Greater personal control may also lead to healthier behaviors, partly by increasing knowledge. Those with greater perceived personal control are more likely to initiate preventive behaviors. 13

Social networks: Educated adults tend to have larger social networks—and these connections bring access to financial, psychological, and emotional resources that may help reduce hardship and stress and improve health. Read More

Social networks also enhance access to information and exposure to peers who model acceptable behaviors. The relationship between social support and education may be due, in part, to the social and cognitive skills and greater involvement with civic groups and organizations that come with education. 16, 17 Low social support is associated with higher death rates and poor mental health. 18, 19

Education is also associated with crime. Among young male high school drop-outs, nearly 1 in 10 was incarcerated on a given day in 2006-2007 versus fewer than 1 of 33 high school graduates. 20 The high incarceration rates in some communities can disrupt social networks and weaken social capital and social control—all of which may impact public health and safety.

“Being able to advocate and ask for what you want, helps to facilitate a healthier lifestyle. … If it's needing your community to have green spaces, have a park, a playground, have better trails within the community, advocating for that will help.” —Chanel

Health Behaviors

Knowledge and skills: In addition to being prepared for better jobs, people with more education are more likely to learn about healthy behaviors. Educated patients may be more able to understand their health needs, follow instructions, advocate for themselves and their families, and communicate effectively with health providers. 21 Read More

People with more education are more likely to learn about health and health risks, improving their literacy and comprehension of what can be complex issues critical to their wellbeing. People who are more educated are more receptive to health education campaigns. Education can also lead to more accurate health beliefs and knowledge, and thus to better lifestyle choices, but also to better skills and greater self-advocacy. Education improves skills such as literacy, develops effective habits, and may improve cognitive ability. The skills acquired through education can affect health indirectly (through better jobs and earnings) or directly (through ability to follow health care regimens and manage diseases), and they can affect the ability of patients to navigate the health system, such as knowing how to get reimbursed by a health plan. Thus, more highly educated individuals may be more able to understand health care issues and follow treatment guidelines. 21–23 The quality of doctor-patient communication is also poorer for patients of low socioeconomic status. A review of the effects of health literacy on health found that people with lower health literacy are more likely to use emergency services and be hospitalized and are less likely to use preventive services such as mammography or take medications and interpret labels correctly. Among the elderly, poor health literacy has been linked to poorer health status and higher death rates. 24

Healthier Neighborhoods

“Poor neighborhoods oftentimes lead to poor schools. Poor schools lead to poor education. Poor education oftentimes leads to poor work. Poor work puts you right back into the poor neighborhood. It's a vicious cycle that happens in communities, especially inner cities.” —Albert

Lower income and fewer resources mean that people with less education are more likely to live in low-income neighborhoods that lack the resources for good health. These neighborhoods are often economically marginalized and segregated and have more risk factors for poor health such as:

- Less access to supermarkets or other sources of healthy food and an oversupply of fast food restaurants and outlets that promote unhealthy foods. 25

Nationwide, access to a store that sells healthier foods is 1.4 less likely in census tracts with fewer college educated adults (less than 27% of the population) than in tracts with a higher proportion of college-educated persons. 26 Food access is important to health because unhealthy eating habits are linked to numerous acute and chronic health problems such as diabetes, hypertension, obesity, heart disease, and stroke as well as higher mortality rates.

“If the best thing that you see in the neighborhood is a drug dealer, then that becomes your goal. If the best thing you see in your neighborhood is working a 9 to 5, then that becomes your goal. But if you see the doctors and the lawyers, if you see the teachers and the professors, then that becomes your goal.” —Marco

“It's a lot of things going on [in this community], a lot of challenges. It's just hard sometimes to try and get people to come together, as one, just so we can solve the problem.” —Toni

- Less green space, such as sidewalks and parks to encourage outdoor physical activity and walking or cycling to work or school.

- Rural and low-income areas, which are more populated by people with less education, often suffer from shortages of primary care physicians and other health care providers and facilities.

- Higher crime rates, exposing residents to greater risk of trauma and deaths from violence and the stress of living in unsafe neighborhoods. People with less education, particularly males, are more likely to be incarcerated, which carries its own public health risks.

- Fewer high-quality schools, often because public schools are poorly resourced by low property taxes. Low-resourced schools have greater difficulty offering attractive teacher salaries or properly maintaining buildings and supplies.

- Fewer jobs, which can exacerbate the economic hardship and poor health that is common for people with less education.

- Higher levels of toxins, such as air and water pollution, hazardous waste, pesticides, andindustrial chemicals. 27

- Less effective political influence to advocate for community needs, resulting in a persistent cycle of disadvantage.

2. Poor Health That Affects Education (Reverse Causality)

“Things that happen in the home can definitely affect a child being able to even concentrate in the classroom. … If you're hungry, you can't learn with your belly growling. … If you’re worried about your mom being safe while you're at school, you're not going to be able to pay attention.” —Chimere

The relationship between education and health is never a simple one. Poor health not only results from lower educational attainment, it can also cause educational setbacks and interfere with schooling.

For example, children with asthma and other chronic illnesses may experience recurrent absences and difficulty concentrating in class. 28 Disabilities can also affect school performance due to difficulties with vision, hearing, attention, behavior, absenteeism, or cognitive skills. Read More

Health conditions, disabilities, and unhealthy behaviors can all have an effect on educational outcomes. Illness, poor nutrition, substance use and smoking, obesity, sleep disorders, mental health, asthma, poor vision, and inattention/hyperactivity have established links to school performance or attainment. 25, 29, 30 For example, compared to other students, children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are three times more likely to be held back (retained a grade) and almost three times more likely to drop out of school before graduation. 31 Children who are born with low birth weight also tend to have poorer educational outcomes, 32, 33 and higher risk for special education placements. 34, 35 Although the impact of health on education (reverse causality) is important, many have questioned how large a role it plays. 1

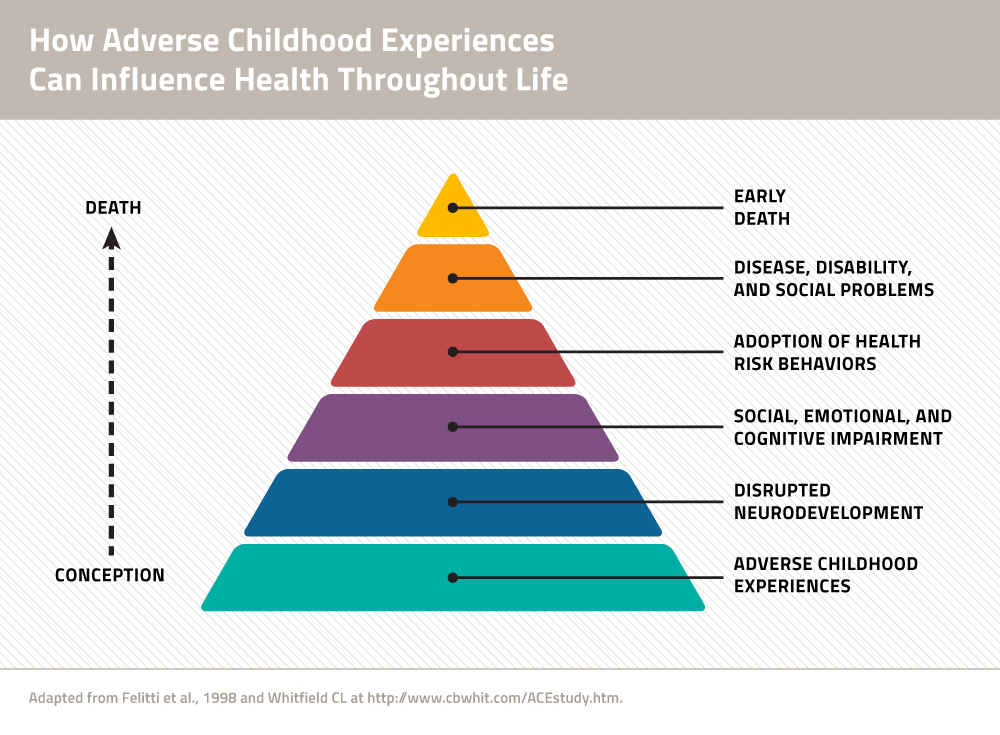

3. Conditions Throughout the Life Course—Beginning in Early Childhood—That Affect Both Health and Education

A third way that education can be linked to health is by exposure to conditions, beginning in early childhood, which can affect both education and health. Throughout life, conditions at home, socioeconomic status, and other contextual factors can create stress, cause illness, and deprive individuals and families of resources for success in school, the workplace, and healthy living. Read More