Narrative Writing: A Complete Guide for Teachers and Students

MASTERING THE CRAFT OF NARRATIVE WRITING

Narratives build on and encourage the development of the fundamentals of writing. They also require developing an additional skill set: the ability to tell a good yarn, and storytelling is as old as humanity.

We see and hear stories everywhere and daily, from having good gossip on the doorstep with a neighbor in the morning to the dramas that fill our screens in the evening.

Good narrative writing skills are hard-won by students even though it is an area of writing that most enjoy due to the creativity and freedom it offers.

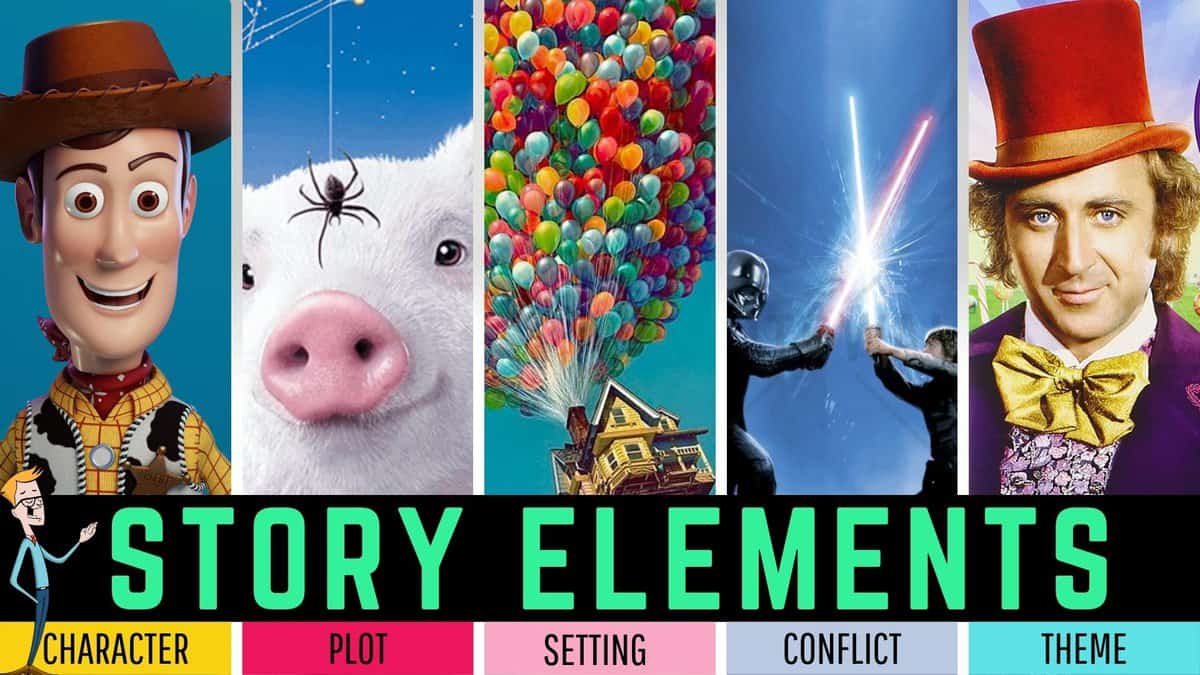

Here we will explore some of the main elements of a good story: plot, setting, characters, conflict, climax, and resolution . And we will look too at how best we can help our students understand these elements, both in isolation and how they mesh together as a whole.

WHAT IS A NARRATIVE?

A narrative is a story that shares a sequence of events , characters, and themes. It expresses experiences, ideas, and perspectives that should aspire to engage and inspire an audience.

A narrative can spark emotion, encourage reflection, and convey meaning when done well.

Narratives are a popular genre for students and teachers as they allow the writer to share their imagination, creativity, skill, and understanding of nearly all elements of writing. We occasionally refer to a narrative as ‘creative writing’ or story writing.

The purpose of a narrative is simple, to tell the audience a story. It can be written to motivate, educate, or entertain and can be fact or fiction.

A COMPLETE UNIT ON TEACHING NARRATIVE WRITING

Teach your students to become skilled story writers with this HUGE NARRATIVE & CREATIVE STORY WRITING UNIT . Offering a COMPLETE SOLUTION to teaching students how to craft CREATIVE CHARACTERS, SUPERB SETTINGS, and PERFECT PLOTS .

Over 192 PAGES of materials, including:

TYPES OF NARRATIVE WRITING

There are many narrative writing genres and sub-genres such as these.

We have a complete guide to writing a personal narrative that differs from the traditional story-based narrative covered in this guide. It includes personal narrative writing prompts, resources, and examples and can be found here.

As we can see, narratives are an open-ended form of writing that allows you to showcase creativity in many directions. However, all narratives share a common set of features and structure known as “Story Elements”, which are briefly covered in this guide.

Don’t overlook the importance of understanding story elements and the value this adds to you as a writer who can dissect and create grand narratives. We also have an in-depth guide to understanding story elements here .

CHARACTERISTICS OF NARRATIVE WRITING

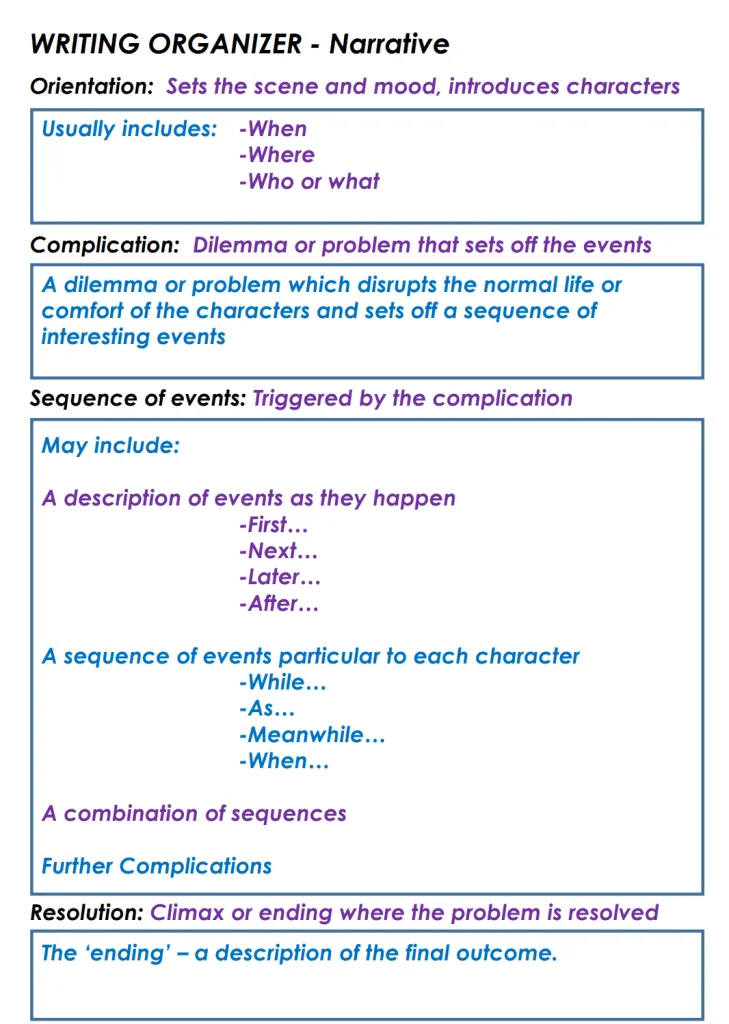

Narrative structure.

ORIENTATION (BEGINNING) Set the scene by introducing your characters, setting and time of the story. Establish your who, when and where in this part of your narrative

COMPLICATION AND EVENTS (MIDDLE) In this section activities and events involving your main characters are expanded upon. These events are written in a cohesive and fluent sequence.

RESOLUTION (ENDING) Your complication is resolved in this section. It does not have to be a happy outcome, however.

EXTRAS: Whilst orientation, complication and resolution are the agreed norms for a narrative, there are numerous examples of popular texts that did not explicitly follow this path exactly.

NARRATIVE FEATURES

LANGUAGE: Use descriptive and figurative language to paint images inside your audience’s minds as they read.

PERSPECTIVE Narratives can be written from any perspective but are most commonly written in first or third person.

DIALOGUE Narratives frequently switch from narrator to first-person dialogue. Always use speech marks when writing dialogue.

TENSE If you change tense, make it perfectly clear to your audience what is happening. Flashbacks might work well in your mind but make sure they translate to your audience.

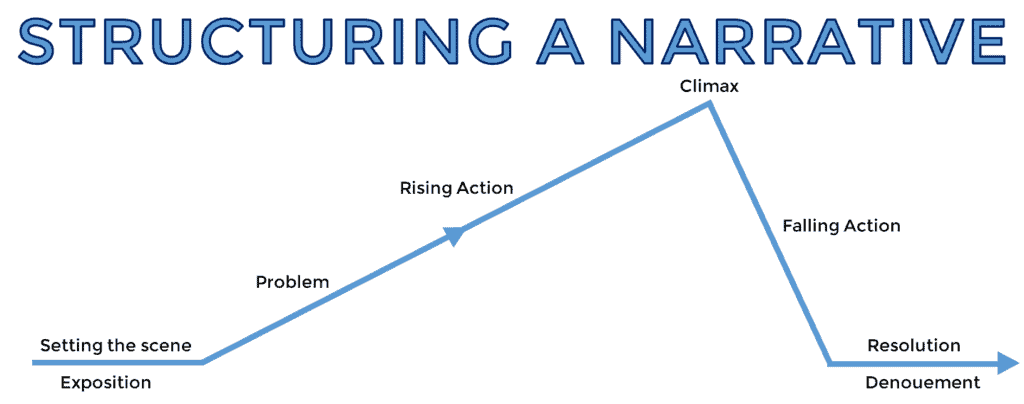

THE PLOT MAP

This graphic is known as a plot map, and nearly all narratives fit this structure in one way or another, whether romance novels, science fiction or otherwise.

It is a simple tool that helps you understand and organise a story’s events. Think of it as a roadmap that outlines the journey of your characters and the events that unfold. It outlines the different stops along the way, such as the introduction, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution, that help you to see how the story builds and develops.

Using a plot map, you can see how each event fits into the larger picture and how the different parts of the story work together to create meaning. It’s a great way to visualize and analyze a story.

Be sure to refer to a plot map when planning a story, as it has all the essential elements of a great story.

THE 5 KEY STORY ELEMENTS OF A GREAT NARRATIVE (6-MINUTE TUTORIAL VIDEO)

This video we created provides an excellent overview of these elements and demonstrates them in action in stories we all know and love.

HOW TO WRITE A NARRATIVE

Now that we understand the story elements and how they come together to form stories, it’s time to start planning and writing your narrative.

In many cases, the template and guide below will provide enough details on how to craft a great story. However, if you still need assistance with the fundamentals of writing, such as sentence structure, paragraphs and using correct grammar, we have some excellent guides on those here.

USE YOUR WRITING TIME EFFECTIVELY: Maximize your narrative writing sessions by spending approximately 20 per cent of your time planning and preparing. This ensures greater productivity during your writing time and keeps you focused and on task.

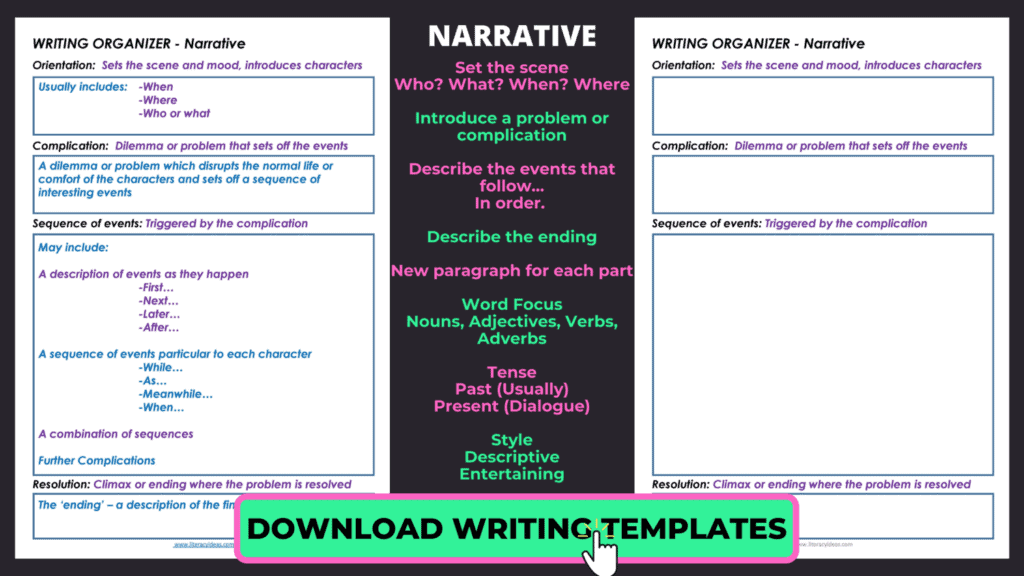

Use tools such as graphic organizers to logically sequence your narrative if you are not a confident story writer. If you are working with reluctant writers, try using narrative writing prompts to get their creative juices flowing.

Spend most of your writing hour on the task at hand, don’t get too side-tracked editing during this time and leave some time for editing. When editing a narrative, examine it for these three elements.

- Spelling and grammar ( Is it readable?)

- Story structure and continuity ( Does it make sense, and does it flow? )

- Character and plot analysis. (Are your characters engaging? Does your problem/resolution work? )

1. SETTING THE SCENE: THE WHERE AND THE WHEN

The story’s setting often answers two of the central questions in the story, namely, the where and the when. The answers to these two crucial questions will often be informed by the type of story the student is writing.

The story’s setting can be chosen to quickly orient the reader to the type of story they are reading. For example, a fictional narrative writing piece such as a horror story will often begin with a description of a haunted house on a hill or an abandoned asylum in the middle of the woods. If we start our story on a rocket ship hurtling through the cosmos on its space voyage to the Alpha Centauri star system, we can be reasonably sure that the story we are embarking on is a work of science fiction.

Such conventions are well-worn clichés true, but they can be helpful starting points for our novice novelists to make a start.

Having students choose an appropriate setting for the type of story they wish to write is an excellent exercise for our younger students. It leads naturally onto the next stage of story writing, which is creating suitable characters to populate this fictional world they have created. However, older or more advanced students may wish to play with the expectations of appropriate settings for their story. They may wish to do this for comic effect or in the interest of creating a more original story. For example, opening a story with a children’s birthday party does not usually set up the expectation of a horror story. Indeed, it may even lure the reader into a happy reverie as they remember their own happy birthday parties. This leaves them more vulnerable to the surprise element of the shocking action that lies ahead.

Once the students have chosen a setting for their story, they need to start writing. Little can be more terrifying to English students than the blank page and its bare whiteness stretching before them on the table like a merciless desert they must cross. Give them the kick-start they need by offering support through word banks or writing prompts. If the class is all writing a story based on the same theme, you may wish to compile a common word bank on the whiteboard as a prewriting activity. Write the central theme or genre in the middle of the board. Have students suggest words or phrases related to the theme and list them on the board.

You may wish to provide students with a copy of various writing prompts to get them started. While this may mean that many students’ stories will have the same beginning, they will most likely arrive at dramatically different endings via dramatically different routes.

A bargain is at the centre of the relationship between the writer and the reader. That bargain is that the reader promises to suspend their disbelief as long as the writer creates a consistent and convincing fictional reality. Creating a believable world for the fictional characters to inhabit requires the student to draw on convincing details. The best way of doing this is through writing that appeals to the senses. Have your student reflect deeply on the world that they are creating. What does it look like? Sound like? What does the food taste like there? How does it feel like to walk those imaginary streets, and what aromas beguile the nose as the main character winds their way through that conjured market?

Also, Consider the when; or the time period. Is it a future world where things are cleaner and more antiseptic? Or is it an overcrowded 16th-century London with human waste stinking up the streets? If students can create a multi-sensory installation in the reader’s mind, then they have done this part of their job well.

Popular Settings from Children’s Literature and Storytelling

- Fairytale Kingdom

- Magical Forest

- Village/town

- Underwater world

- Space/Alien planet

2. CASTING THE CHARACTERS: THE WHO

Now that your student has created a believable world, it is time to populate it with believable characters.

In short stories, these worlds mustn’t be overpopulated beyond what the student’s skill level can manage. Short stories usually only require one main character and a few secondary ones. Think of the short story more as a small-scale dramatic production in an intimate local theater than a Hollywood blockbuster on a grand scale. Too many characters will only confuse and become unwieldy with a canvas this size. Keep it simple!

Creating believable characters is often one of the most challenging aspects of narrative writing for students. Fortunately, we can do a few things to help students here. Sometimes it is helpful for students to model their characters on actual people they know. This can make things a little less daunting and taxing on the imagination. However, whether or not this is the case, writing brief background bios or descriptions of characters’ physical personality characteristics can be a beneficial prewriting activity. Students should give some in-depth consideration to the details of who their character is: How do they walk? What do they look like? Do they have any distinguishing features? A crooked nose? A limp? Bad breath? Small details such as these bring life and, therefore, believability to characters. Students can even cut pictures from magazines to put a face to their character and allow their imaginations to fill in the rest of the details.

Younger students will often dictate to the reader the nature of their characters. To improve their writing craft, students must know when to switch from story-telling mode to story-showing mode. This is particularly true when it comes to character. Encourage students to reveal their character’s personality through what they do rather than merely by lecturing the reader on the faults and virtues of the character’s personality. It might be a small relayed detail in the way they walk that reveals a core characteristic. For example, a character who walks with their head hanging low and shoulders hunched while avoiding eye contact has been revealed to be timid without the word once being mentioned. This is a much more artistic and well-crafted way of doing things and is less irritating for the reader. A character who sits down at the family dinner table immediately snatches up his fork and starts stuffing roast potatoes into his mouth before anyone else has even managed to sit down has revealed a tendency towards greed or gluttony.

Understanding Character Traits

Again, there is room here for some fun and profitable prewriting activities. Give students a list of character traits and have them describe a character doing something that reveals that trait without ever employing the word itself.

It is also essential to avoid adjective stuffing here. When looking at students’ early drafts, adjective stuffing is often apparent. To train the student out of this habit, choose an adjective and have the student rewrite the sentence to express this adjective through action rather than telling.

When writing a story, it is vital to consider the character’s traits and how they will impact the story’s events. For example, a character with a strong trait of determination may be more likely to overcome obstacles and persevere. In contrast, a character with a tendency towards laziness may struggle to achieve their goals. In short, character traits add realism, depth, and meaning to a story, making it more engaging and memorable for the reader.

Popular Character Traits in Children’s Stories

- Determination

- Imagination

- Perseverance

- Responsibility

We have an in-depth guide to creating great characters here , but most students should be fine to move on to planning their conflict and resolution.

3. NO PROBLEM? NO STORY! HOW CONFLICT DRIVES A NARRATIVE

This is often the area apprentice writers have the most difficulty with. Students must understand that without a problem or conflict, there is no story. The problem is the driving force of the action. Usually, in a short story, the problem will center around what the primary character wants to happen or, indeed, wants not to happen. It is the hurdle that must be overcome. It is in the struggle to overcome this hurdle that events happen.

Often when a student understands the need for a problem in a story, their completed work will still not be successful. This is because, often in life, problems remain unsolved. Hurdles are not always successfully overcome. Students pick up on this.

We often discuss problems with friends that will never be satisfactorily resolved one way or the other, and we accept this as a part of life. This is not usually the case with writing a story. Whether a character successfully overcomes his or her problem or is decidedly crushed in the process of trying is not as important as the fact that it will finally be resolved one way or the other.

A good practical exercise for students to get to grips with this is to provide copies of stories and have them identify the central problem or conflict in each through discussion. Familiar fables or fairy tales such as Three Little Pigs, The Boy Who Cried Wolf, Cinderella, etc., are great for this.

While it is true that stories often have more than one problem or that the hero or heroine is unsuccessful in their first attempt to solve a central problem, for beginning students and intermediate students, it is best to focus on a single problem, especially given the scope of story writing at this level. Over time students will develop their abilities to handle more complex plots and write accordingly.

Popular Conflicts found in Children’s Storytelling.

- Good vs evil

- Individual vs society

- Nature vs nurture

- Self vs others

- Man vs self

- Man vs nature

- Man vs technology

- Individual vs fate

- Self vs destiny

Conflict is the heart and soul of any good story. It’s what makes a story compelling and drives the plot forward. Without conflict, there is no story. Every great story has a struggle or a problem that needs to be solved, and that’s where conflict comes in. Conflict is what makes a story exciting and keeps the reader engaged. It creates tension and suspense and makes the reader care about the outcome.

Like in real life, conflict in a story is an opportunity for a character’s growth and transformation. It’s a chance for them to learn and evolve, making a story great. So next time stories are written in the classroom, remember that conflict is an essential ingredient, and without it, your story will lack the energy, excitement, and meaning that makes it truly memorable.

4. THE NARRATIVE CLIMAX: HOW THINGS COME TO A HEAD!

The climax of the story is the dramatic high point of the action. It is also when the struggles kicked off by the problem come to a head. The climax will ultimately decide whether the story will have a happy or tragic ending. In the climax, two opposing forces duke things out until the bitter (or sweet!) end. One force ultimately emerges triumphant. As the action builds throughout the story, suspense increases as the reader wonders which of these forces will win out. The climax is the release of this suspense.

Much of the success of the climax depends on how well the other elements of the story have been achieved. If the student has created a well-drawn and believable character that the reader can identify with and feel for, then the climax will be more powerful.

The nature of the problem is also essential as it determines what’s at stake in the climax. The problem must matter dearly to the main character if it matters at all to the reader.

Have students engage in discussions about their favorite movies and books. Have them think about the storyline and decide the most exciting parts. What was at stake at these moments? What happened in your body as you read or watched? Did you breathe faster? Or grip the cushion hard? Did your heart rate increase, or did you start to sweat? This is what a good climax does and what our students should strive to do in their stories.

The climax puts it all on the line and rolls the dice. Let the chips fall where the writer may…

Popular Climax themes in Children’s Stories

- A battle between good and evil

- The character’s bravery saves the day

- Character faces their fears and overcomes them

- The character solves a mystery or puzzle.

- The character stands up for what is right.

- Character reaches their goal or dream.

- The character learns a valuable lesson.

- The character makes a selfless sacrifice.

- The character makes a difficult decision.

- The character reunites with loved ones or finds true friendship.

5. RESOLUTION: TYING UP LOOSE ENDS

After the climactic action, a few questions will often remain unresolved for the reader, even if all the conflict has been resolved. The resolution is where those lingering questions will be answered. The resolution in a short story may only be a brief paragraph or two. But, in most cases, it will still be necessary to include an ending immediately after the climax can feel too abrupt and leave the reader feeling unfulfilled.

An easy way to explain resolution to students struggling to grasp the concept is to point to the traditional resolution of fairy tales, the “And they all lived happily ever after” ending. This weather forecast for the future allows the reader to take their leave. Have the student consider the emotions they want to leave the reader with when crafting their resolution.

While the action is usually complete by the end of the climax, it is in the resolution that if there is a twist to be found, it will appear – think of movies such as The Usual Suspects. Pulling this off convincingly usually requires considerable skill from a student writer. Still, it may well form a challenging extension exercise for those more gifted storytellers among your students.

Popular Resolutions in Children’s Stories

- Our hero achieves their goal

- The character learns a valuable lesson

- A character finds happiness or inner peace.

- The character reunites with loved ones.

- Character restores balance to the world.

- The character discovers their true identity.

- Character changes for the better.

- The character gains wisdom or understanding.

- Character makes amends with others.

- The character learns to appreciate what they have.

Once students have completed their story, they can edit for grammar, vocabulary choice, spelling, etc., but not before!

As mentioned, there is a craft to storytelling, as well as an art. When accurate grammar, perfect spelling, and immaculate sentence structures are pushed at the outset, they can cause storytelling paralysis. For this reason, it is essential that when we encourage the students to write a story, we give them license to make mechanical mistakes in their use of language that they can work on and fix later.

Good narrative writing is a very complex skill to develop and will take the student years to become competent. It challenges not only the student’s technical abilities with language but also her creative faculties. Writing frames, word banks, mind maps, and visual prompts can all give valuable support as students develop the wide-ranging and challenging skills required to produce a successful narrative writing piece. But, at the end of it all, as with any craft, practice and more practice is at the heart of the matter.

TIPS FOR WRITING A GREAT NARRATIVE

- Start your story with a clear purpose: If you can determine the theme or message you want to convey in your narrative before starting it will make the writing process so much simpler.

- Choose a compelling storyline and sell it through great characters, setting and plot: Consider a unique or interesting story that captures the reader’s attention, then build the world and characters around it.

- Develop vivid characters that are not all the same: Make your characters relatable and memorable by giving them distinct personalities and traits you can draw upon in the plot.

- Use descriptive language to hook your audience into your story: Use sensory language to paint vivid images and sequences in the reader’s mind.

- Show, don’t tell your audience: Use actions, thoughts, and dialogue to reveal character motivations and emotions through storytelling.

- Create a vivid setting that is clear to your audience before getting too far into the plot: Describe the time and place of your story to immerse the reader fully.

- Build tension: Refer to the story map earlier in this article and use conflict, obstacles, and suspense to keep the audience engaged and invested in your narrative.

- Use figurative language such as metaphors, similes, and other literary devices to add depth and meaning to your narrative.

- Edit, revise, and refine: Take the time to refine and polish your writing for clarity and impact.

- Stay true to your voice: Maintain your unique perspective and style in your writing to make it your own.

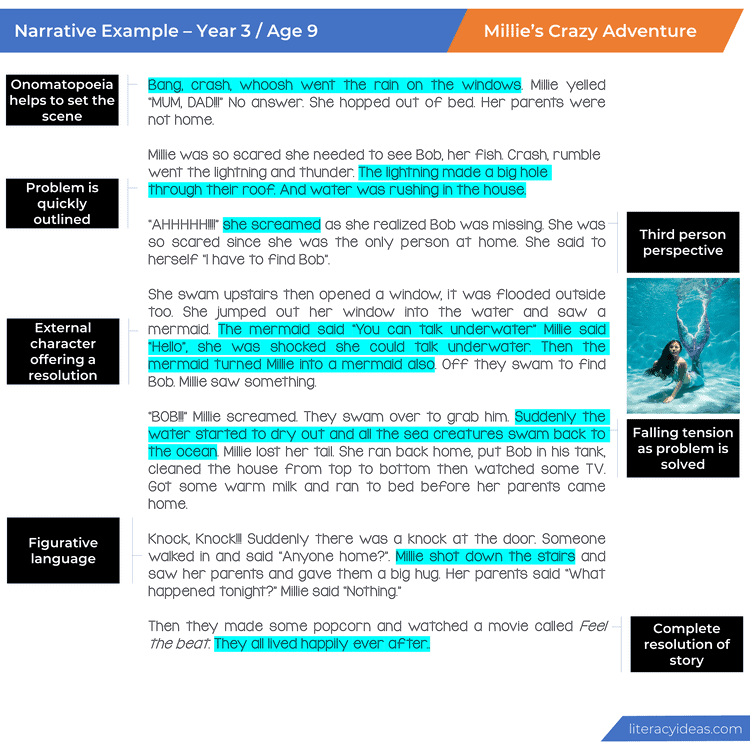

NARRATIVE WRITING EXAMPLES (Student Writing Samples)

Below are a collection of student writing samples of narratives. Click on the image to enlarge and explore them in greater detail. Please take a moment to read these creative stories in detail and the teacher and student guides which highlight some of the critical elements of narratives to consider before writing.

Please understand these student writing samples are not intended to be perfect examples for each age or grade level but a piece of writing for students and teachers to explore together to critically analyze to improve student writing skills and deepen their understanding of story writing.

We recommend reading the example either a year above or below, as well as the grade you are currently working with, to gain a broader appreciation of this text type.

NARRATIVE WRITING PROMPTS (Journal Prompts)

When students have a great journal prompt, it can help them focus on the task at hand, so be sure to view our vast collection of visual writing prompts for various text types here or use some of these.

- On a recent European trip, you find your travel group booked into the stunning and mysterious Castle Frankenfurter for a single night… As night falls, the massive castle of over one hundred rooms seems to creak and groan as a series of unexplained events begin to make you wonder who or what else is spending the evening with you. Write a narrative that tells the story of your evening.

- You are a famous adventurer who has discovered new lands; keep a travel log over a period of time in which you encounter new and exciting adventures and challenges to overcome. Ensure your travel journal tells a story and has a definite introduction, conflict and resolution.

- You create an incredible piece of technology that has the capacity to change the world. As you sit back and marvel at your innovation and the endless possibilities ahead of you, it becomes apparent there are a few problems you didn’t really consider. You might not even be able to control them. Write a narrative in which you ride the highs and lows of your world-changing creation with a clear introduction, conflict and resolution.

- As the final door shuts on the Megamall, you realise you have done it… You and your best friend have managed to sneak into the largest shopping centre in town and have the entire place to yourselves until 7 am tomorrow. There is literally everything and anything a child would dream of entertaining themselves for the next 12 hours. What amazing adventures await you? What might go wrong? And how will you get out of there scot-free?

- A stranger walks into town… Whilst appearing similar to almost all those around you, you get a sense that this person is from another time, space or dimension… Are they friends or foes? What makes you sense something very strange is going on? Suddenly they stand up and walk toward you with purpose extending their hand… It’s almost as if they were reading your mind.

NARRATIVE WRITING VIDEO TUTORIAL

Teaching Resources

Use our resources and tools to improve your student’s writing skills through proven teaching strategies.

When teaching narrative writing, it is essential that you have a range of tools, strategies and resources at your disposal to ensure you get the most out of your writing time. You can find some examples below, which are free and paid premium resources you can use instantly without any preparation.

FREE Narrative Graphic Organizer

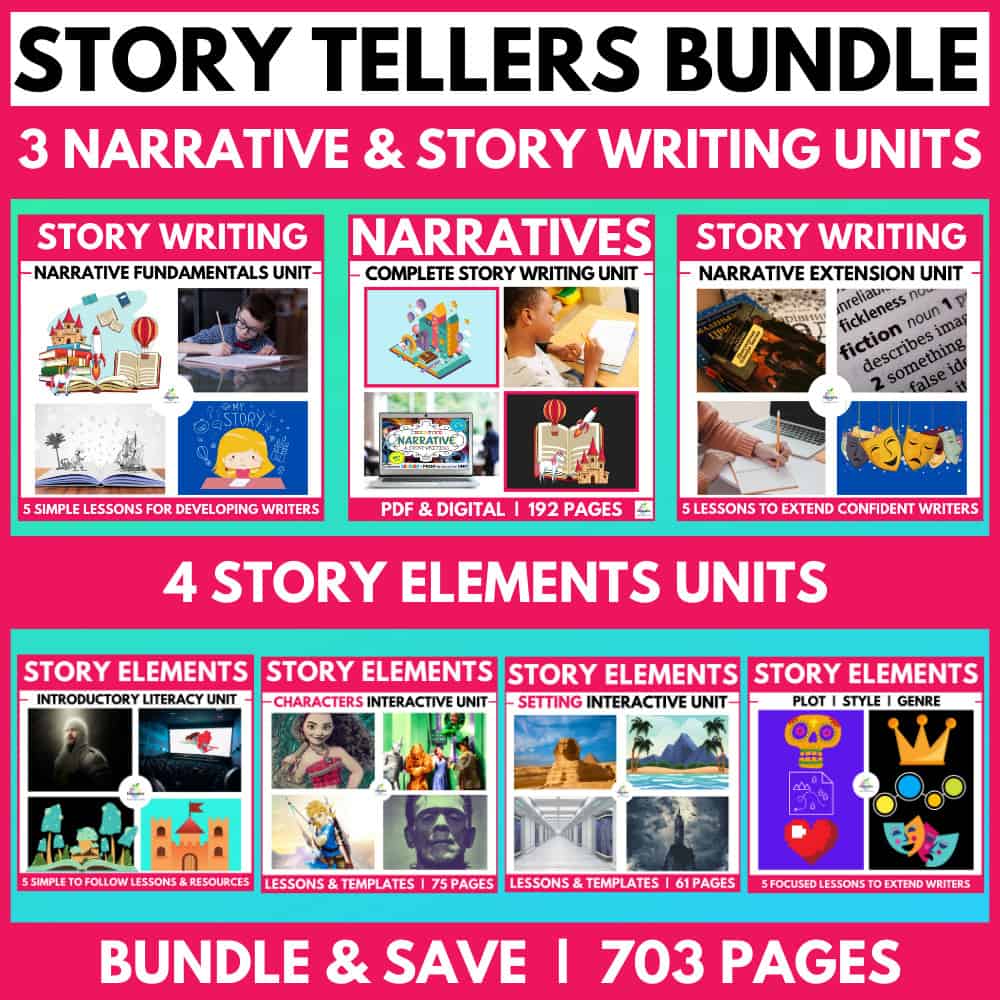

THE STORY TELLERS BUNDLE OF TEACHING RESOURCES

A MASSIVE COLLECTION of resources for narratives and story writing in the classroom covering all elements of crafting amazing stories. MONTHS WORTH OF WRITING LESSONS AND RESOURCES, including:

NARRATIVE WRITING CHECKLIST BUNDLE

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ (92 Reviews)

OTHER GREAT ARTICLES ABOUT NARRATIVE WRITING

Narrative Writing for Kids: Essential Skills and Strategies

7 Great Narrative Lesson Plans Students and Teachers Love

Top 7 Narrative Writing Exercises for Students

How to Write a Scary Story

Essay vs. Short Story

What's the difference.

Essays and short stories are both forms of written expression, but they differ in their purpose and structure. Essays are typically non-fiction pieces that aim to inform or persuade the reader about a specific topic. They often follow a formal structure with an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion. On the other hand, short stories are fictional narratives that focus on character development and plot. They can be written in various genres and styles, allowing for more creativity and imagination. While essays prioritize facts and logical arguments, short stories prioritize storytelling and evoking emotions in the reader.

| Attribute | Essay | Short Story |

|---|---|---|

| Length | Varies, can be short or long | Short, typically under 20,000 words |

| Structure | Introduction, body paragraphs, conclusion | Usually has a clear beginning, middle, and end |

| Plot | May or may not have a plot | Has a defined plot with conflict and resolution |

| Character Development | May or may not have in-depth character development | Characters are often developed within a limited scope |

| Theme | Explores a specific topic or idea | Focuses on a central theme or message |

| Tone | Varies depending on the purpose and subject matter | Can range from serious to humorous, depending on the story |

| Point of View | Can be written from various perspectives | Usually written from a single point of view |

| Language | Can be formal or informal, depending on the context | Varies, but often uses descriptive and concise language |

Further Detail

Introduction.

When it comes to literary forms, essays and short stories are two popular choices that captivate readers with their unique attributes. While both share the goal of conveying a message or exploring a theme, they differ in various aspects, including structure, length, and narrative techniques. In this article, we will delve into the characteristics of essays and short stories, highlighting their similarities and differences.

One of the primary distinctions between essays and short stories lies in their structure. Essays typically follow a more formal and structured format, often consisting of an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion. The introduction sets the stage by presenting the topic and thesis statement, while the body paragraphs provide supporting evidence and analysis. Finally, the conclusion summarizes the main points and offers a closing thought.

On the other hand, short stories have a more flexible structure. They often begin with an exposition, introducing the characters, setting, and conflict. The plot then unfolds through rising action, climax, and resolution. Unlike essays, short stories allow for more creative freedom in terms of narrative structure, with authors employing various techniques such as flashbacks, foreshadowing, or nonlinear storytelling to engage readers.

Another significant difference between essays and short stories is their length. Essays are typically shorter in length, ranging from a few hundred to a few thousand words. The brevity of essays allows writers to present their ideas concisely and directly, making them suitable for conveying arguments or exploring specific topics in a focused manner.

On the contrary, short stories are longer and more expansive in nature. They can range from a few pages to several dozen pages, providing authors with ample space to develop characters, build suspense, and create intricate plotlines. The extended length of short stories allows for a deeper exploration of themes and emotions, often leaving readers with a more immersive and satisfying reading experience.

Narrative Techniques

While both essays and short stories employ narrative techniques to engage readers, they differ in their approach. Essays primarily rely on logical reasoning, evidence, and analysis to convey their message. Writers use persuasive techniques, such as ethos, pathos, and logos, to appeal to the reader's intellect and emotions. The narrative in essays is often more straightforward and focused on presenting a coherent argument or viewpoint.

In contrast, short stories utilize a wide range of narrative techniques to create a captivating and immersive experience. Authors employ descriptive language, dialogue, and vivid imagery to bring characters and settings to life. They can experiment with different points of view, shifting perspectives, and unreliable narrators to add depth and complexity to the story. The narrative in short stories is often more imaginative and allows for a greater exploration of the human experience.

Themes and Messages

Both essays and short stories aim to convey themes and messages to their readers, but they do so in distinct ways. Essays often focus on presenting an argument or discussing a specific topic, aiming to inform, persuade, or provoke thought. The themes in essays are typically more explicit and directly related to the subject matter being discussed.

On the other hand, short stories explore themes and messages through storytelling and the experiences of characters. They often delve into complex human emotions, moral dilemmas, or societal issues, allowing readers to reflect on the deeper meaning behind the narrative. The themes in short stories are often more implicit, requiring readers to analyze the story's events and characters to uncover the underlying messages.

In conclusion, while essays and short stories share the common goal of conveying a message or exploring a theme, they differ significantly in terms of structure, length, narrative techniques, and the way they approach themes. Essays offer a more formal and structured approach, focusing on presenting arguments and analysis concisely. On the other hand, short stories provide a more immersive and imaginative experience, allowing for the exploration of complex characters, plotlines, and themes. Both forms of writing have their unique merits and appeal, catering to different reading preferences and purposes.

Comparisons may contain inaccurate information about people, places, or facts. Please report any issues.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Narrative Essays

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

What is a narrative essay?

When writing a narrative essay, one might think of it as telling a story. These essays are often anecdotal, experiential, and personal—allowing students to express themselves in a creative and, quite often, moving ways.

Here are some guidelines for writing a narrative essay.

- If written as a story, the essay should include all the parts of a story.

This means that you must include an introduction, plot, characters, setting, climax, and conclusion.

- When would a narrative essay not be written as a story?

A good example of this is when an instructor asks a student to write a book report. Obviously, this would not necessarily follow the pattern of a story and would focus on providing an informative narrative for the reader.

- The essay should have a purpose.

Make a point! Think of this as the thesis of your story. If there is no point to what you are narrating, why narrate it at all?

- The essay should be written from a clear point of view.

It is quite common for narrative essays to be written from the standpoint of the author; however, this is not the sole perspective to be considered. Creativity in narrative essays oftentimes manifests itself in the form of authorial perspective.

- Use clear and concise language throughout the essay.

Much like the descriptive essay, narrative essays are effective when the language is carefully, particularly, and artfully chosen. Use specific language to evoke specific emotions and senses in the reader.

- The use of the first person pronoun ‘I’ is welcomed.

Do not abuse this guideline! Though it is welcomed it is not necessary—nor should it be overused for lack of clearer diction.

- As always, be organized!

Have a clear introduction that sets the tone for the remainder of the essay. Do not leave the reader guessing about the purpose of your narrative. Remember, you are in control of the essay, so guide it where you desire (just make sure your audience can follow your lead).

BibGuru Blog

Be more productive in school

- Citation Styles

How to write a narrative essay [Updated 2023]

A narrative essay is an opportunity to flex your creative muscles and craft a compelling story. In this blog post, we define what a narrative essay is and provide strategies and examples for writing one.

What is a narrative essay?

Similarly to a descriptive essay or a reflective essay, a narrative essay asks you to tell a story, rather than make an argument and present evidence. Most narrative essays describe a real, personal experience from your own life (for example, the story of your first big success).

Alternately, your narrative essay might focus on an imagined experience (for example, how your life would be if you had been born into different circumstances). While you don’t need to present a thesis statement or scholarly evidence, a narrative essay still needs to be well-structured and clearly organized so that the reader can follow your story.

When you might be asked to write a narrative essay

Although less popular than argumentative essays or expository essays, narrative essays are relatively common in high school and college writing classes.

The same techniques that you would use to write a college essay as part of a college or scholarship application are applicable to narrative essays, as well. In fact, the Common App that many students use to apply to multiple colleges asks you to submit a narrative essay.

How to choose a topic for a narrative essay

When you are asked to write a narrative essay, a topic may be assigned to you or you may be able to choose your own. With an assigned topic, the prompt will likely fall into one of two categories: specific or open-ended.

Examples of specific prompts:

- Write about the last vacation you took.

- Write about your final year of middle school.

Examples of open-ended prompts:

- Write about a time when you felt all hope was lost.

- Write about a brief, seemingly insignificant event that ended up having a big impact on your life.

A narrative essay tells a story and all good stories are centered on a conflict of some sort. Experiences with unexpected obstacles, twists, or turns make for much more compelling essays and reveal more about your character and views on life.

If you’re writing a narrative essay as part of an admissions application, remember that the people reviewing your essay will be looking at it to gain a sense of not just your writing ability, but who you are as a person.

In these cases, it’s wise to choose a topic and experience from your life that demonstrates the qualities that the prompt is looking for, such as resilience, perseverance, the ability to stay calm under pressure, etc.

It’s also important to remember that your choice of topic is just a starting point. Many students find that they arrive at new ideas and insights as they write their first draft, so the final form of your essay may have a different focus than the one you started with.

How to outline and format a narrative essay

Even though you’re not advancing an argument or proving a point of view, a narrative essay still needs to have a coherent structure. Your reader has to be able to follow you as you tell the story and to figure out the larger point that you’re making.

You’ll be evaluated on is your handling of the topic and how you structure your essay. Even though a narrative essay doesn’t use the same structure as other essay types, you should still sketch out a loose outline so you can tell your story in a clear and compelling way.

To outline a narrative essay, you’ll want to determine:

- how your story will start

- what points or specifics that you want to cover

- how your story will end

- what pace and tone you will use

In the vast majority of cases, a narrative essay should be written in the first-person, using “I.” Also, most narrative essays will follow typical formatting guidelines, so you should choose a readable font like Times New Roman in size 11 or 12. Double-space your paragraphs and use 1” margins.

To get your creative wheels turning, consider how your story compares to archetypes and famous historical and literary figures both past and present. Weave these comparisons into your essay to improve the quality of your writing and connect your personal experience to a larger context.

How to write a narrative essay

Writing a narrative essay can sometimes be a challenge for students who typically write argumentative essays or research papers in a formal, objective style. To give you a better sense of how you can write a narrative essay, here is a short example of an essay in response to the prompt, “Write about an experience that challenged your view of yourself.”

Narrative essay example

Even as a child, I always had what people might call a reserved personality. It was sometimes framed as a positive (“Sarah is a good listener”) and at other times it was put in less-than-admiring terms (“Sarah is withdrawn and not very talkative”). It was the latter kind of comments that caused me to see my introverted nature as a drawback and as something I should work to eliminate. That is, until I joined my high school’s student council.

The first paragraph, or introduction, sets up the context, establishing the situation and introducing the meaningful event upon which the essay will focus.

The other four students making up the council were very outspoken and enthusiastic. I enjoyed being around them, and I often agreed with their ideas. However, when it came to overhauling our school’s recycling plan, we butted heads. When I spoke up and offered a different point of view, one of my fellow student council members launched into a speech, advocating for her point of view. As her voice filled the room, I couldn’t get a word in edgewise. I wondered if I should try to match her tone, volume, and assertiveness as a way to be heard. But I just couldn’t do it—it’s not my way, and it never has been. For a fleeting moment, I felt defeated. But then, something in me shifted.

In this paragraph, the writer goes into greater depth about how her existing thinking brought her to this point.

I reminded myself that my view was valid and deserved to be heard. So I waited. I let my fellow council member speak her piece and when she was finished, I deliberately waited a few moments before calmly stating my case. I chose my words well, and I spoke them succinctly. Just because I’m not a big talker doesn’t mean I’m not a big thinker. I thought of the quotation “still waters run deep” and I tried to embody that. The effect on the room was palpable. People listened. And I hadn’t had to shout my point to be heard.

This paragraph demonstrates the turn in the story, the moment when everything changed. The use of the quotation “still waters run deep” imbues the story with a dash of poetry and emotion.

We eventually reached a compromise on the matter and concluded the student council meeting. Our council supervisor came to me afterward and said: “You handled that so well, with such grace and poise. I was very impressed.” Her words in that moment changed me. I realized that a bombastic nature isn't necessarily a powerful one. There is power in quiet, too. This experience taught me to view my reserved personality not as a character flaw, but as a strength.

The final paragraph, or conclusion, closes with a statement about the significance of this event and how it ended up changing the writer in a meaningful way.

Narrative essay writing tips

1. pick a meaningful story that has a conflict and a clear “moral.”.

If you’re able to choose your own topic, pick a story that has meaning and that reveals how you became the person your are today. In other words, write a narrative with a clear “moral” that you can connect with your main points.

2. Use an outline to arrange the structure of your story and organize your main points.

Although a narrative essay is different from argumentative essays, it’s still beneficial to construct an outline so that your story is well-structured and organized. Note how you want to start and end your story, and what points you want to make to tie everything together.

3. Be clear, concise, concrete, and correct in your writing.

You should use descriptive writing in your narrative essay, but don’t overdo it. Use clear, concise, and correct language and grammar throughout. Additionally, make concrete points that reinforce the main idea of your narrative.

4. Ask a friend or family member to proofread your essay.

No matter what kind of writing you’re doing, you should always plan to proofread and revise. To ensure that your narrative essay is coherent and interesting, ask a friend or family member to read over your paper. This is especially important if your essay is responding to a prompt. It helps to have another person check to make sure that you’ve fully responded to the prompt or question.

Frequently Asked Questions about narrative essays

A narrative essay, like any essay, has three main parts: an introduction, a body and a conclusion. Structuring and outlining your essay before you start writing will help you write a clear story that your readers can follow.

The first paragraph of your essay, or introduction, sets up the context, establishing the situation and introducing the meaningful event upon which the essay will focus.

In the vast majority of cases, a narrative essay should be written in the first-person, using “I.”

The 4 main types of essays are the argumentative essay, narrative essay, exploratory essay, and expository essay. You may be asked to write different types of essays at different points in your education.

Most narrative essays will be around five paragraphs, or more, depending on the topic and requirements. Make sure to check in with your instructor about the guidelines for your essay. If you’re writing a narrative essay for a college application, pay close attention to word or page count requirements.

Make your life easier with our productivity and writing resources.

For students and teachers.

Frequently asked questions

What’s the difference between a narrative essay and a descriptive essay.

The key difference is that a narrative essay is designed to tell a complete story, while a descriptive essay is meant to convey an intense description of a particular place, object, or concept.

Narrative and descriptive essays both allow you to write more personally and creatively than other kinds of essays , and similar writing skills can apply to both.

Frequently asked questions: Writing an essay

For a stronger conclusion paragraph, avoid including:

- Important evidence or analysis that wasn’t mentioned in the main body

- Generic concluding phrases (e.g. “In conclusion…”)

- Weak statements that undermine your argument (e.g. “There are good points on both sides of this issue.”)

Your conclusion should leave the reader with a strong, decisive impression of your work.

Your essay’s conclusion should contain:

- A rephrased version of your overall thesis

- A brief review of the key points you made in the main body

- An indication of why your argument matters

The conclusion may also reflect on the broader implications of your argument, showing how your ideas could applied to other contexts or debates.

The conclusion paragraph of an essay is usually shorter than the introduction . As a rule, it shouldn’t take up more than 10–15% of the text.

An essay is a focused piece of writing that explains, argues, describes, or narrates.

In high school, you may have to write many different types of essays to develop your writing skills.

Academic essays at college level are usually argumentative : you develop a clear thesis about your topic and make a case for your position using evidence, analysis and interpretation.

The “hook” is the first sentence of your essay introduction . It should lead the reader into your essay, giving a sense of why it’s interesting.

To write a good hook, avoid overly broad statements or long, dense sentences. Try to start with something clear, concise and catchy that will spark your reader’s curiosity.

Your essay introduction should include three main things, in this order:

- An opening hook to catch the reader’s attention.

- Relevant background information that the reader needs to know.

- A thesis statement that presents your main point or argument.

The length of each part depends on the length and complexity of your essay .

Let’s say you’re writing a five-paragraph essay about the environmental impacts of dietary choices. Here are three examples of topic sentences you could use for each of the three body paragraphs :

- Research has shown that the meat industry has severe environmental impacts.

- However, many plant-based foods are also produced in environmentally damaging ways.

- It’s important to consider not only what type of diet we eat, but where our food comes from and how it is produced.

Each of these sentences expresses one main idea – by listing them in order, we can see the overall structure of the essay at a glance. Each paragraph will expand on the topic sentence with relevant detail, evidence, and arguments.

The topic sentence usually comes at the very start of the paragraph .

However, sometimes you might start with a transition sentence to summarize what was discussed in previous paragraphs, followed by the topic sentence that expresses the focus of the current paragraph.

Topic sentences help keep your writing focused and guide the reader through your argument.

In an essay or paper , each paragraph should focus on a single idea. By stating the main idea in the topic sentence, you clarify what the paragraph is about for both yourself and your reader.

A topic sentence is a sentence that expresses the main point of a paragraph . Everything else in the paragraph should relate to the topic sentence.

The thesis statement is essential in any academic essay or research paper for two main reasons:

- It gives your writing direction and focus.

- It gives the reader a concise summary of your main point.

Without a clear thesis statement, an essay can end up rambling and unfocused, leaving your reader unsure of exactly what you want to say.

The thesis statement should be placed at the end of your essay introduction .

Follow these four steps to come up with a thesis statement :

- Ask a question about your topic .

- Write your initial answer.

- Develop your answer by including reasons.

- Refine your answer, adding more detail and nuance.

A thesis statement is a sentence that sums up the central point of your paper or essay . Everything else you write should relate to this key idea.

An essay isn’t just a loose collection of facts and ideas. Instead, it should be centered on an overarching argument (summarized in your thesis statement ) that every part of the essay relates to.

The way you structure your essay is crucial to presenting your argument coherently. A well-structured essay helps your reader follow the logic of your ideas and understand your overall point.

The structure of an essay is divided into an introduction that presents your topic and thesis statement , a body containing your in-depth analysis and arguments, and a conclusion wrapping up your ideas.

The structure of the body is flexible, but you should always spend some time thinking about how you can organize your essay to best serve your ideas.

The vast majority of essays written at university are some sort of argumentative essay . Almost all academic writing involves building up an argument, though other types of essay might be assigned in composition classes.

Essays can present arguments about all kinds of different topics. For example:

- In a literary analysis essay, you might make an argument for a specific interpretation of a text

- In a history essay, you might present an argument for the importance of a particular event

- In a politics essay, you might argue for the validity of a certain political theory

At high school and in composition classes at university, you’ll often be told to write a specific type of essay , but you might also just be given prompts.

Look for keywords in these prompts that suggest a certain approach: The word “explain” suggests you should write an expository essay , while the word “describe” implies a descriptive essay . An argumentative essay might be prompted with the word “assess” or “argue.”

In rhetorical analysis , a claim is something the author wants the audience to believe. A support is the evidence or appeal they use to convince the reader to believe the claim. A warrant is the (often implicit) assumption that links the support with the claim.

Logos appeals to the audience’s reason, building up logical arguments . Ethos appeals to the speaker’s status or authority, making the audience more likely to trust them. Pathos appeals to the emotions, trying to make the audience feel angry or sympathetic, for example.

Collectively, these three appeals are sometimes called the rhetorical triangle . They are central to rhetorical analysis , though a piece of rhetoric might not necessarily use all of them.

The term “text” in a rhetorical analysis essay refers to whatever object you’re analyzing. It’s frequently a piece of writing or a speech, but it doesn’t have to be. For example, you could also treat an advertisement or political cartoon as a text.

The goal of a rhetorical analysis is to explain the effect a piece of writing or oratory has on its audience, how successful it is, and the devices and appeals it uses to achieve its goals.

Unlike a standard argumentative essay , it’s less about taking a position on the arguments presented, and more about exploring how they are constructed.

You should try to follow your outline as you write your essay . However, if your ideas change or it becomes clear that your structure could be better, it’s okay to depart from your essay outline . Just make sure you know why you’re doing so.

If you have to hand in your essay outline , you may be given specific guidelines stating whether you have to use full sentences. If you’re not sure, ask your supervisor.

When writing an essay outline for yourself, the choice is yours. Some students find it helpful to write out their ideas in full sentences, while others prefer to summarize them in short phrases.

You will sometimes be asked to hand in an essay outline before you start writing your essay . Your supervisor wants to see that you have a clear idea of your structure so that writing will go smoothly.

Even when you do not have to hand it in, writing an essay outline is an important part of the writing process . It’s a good idea to write one (as informally as you like) to clarify your structure for yourself whenever you are working on an essay.

Comparisons in essays are generally structured in one of two ways:

- The alternating method, where you compare your subjects side by side according to one specific aspect at a time.

- The block method, where you cover each subject separately in its entirety.

It’s also possible to combine both methods, for example by writing a full paragraph on each of your topics and then a final paragraph contrasting the two according to a specific metric.

Your subjects might be very different or quite similar, but it’s important that there be meaningful grounds for comparison . You can probably describe many differences between a cat and a bicycle, but there isn’t really any connection between them to justify the comparison.

You’ll have to write a thesis statement explaining the central point you want to make in your essay , so be sure to know in advance what connects your subjects and makes them worth comparing.

Some essay prompts include the keywords “compare” and/or “contrast.” In these cases, an essay structured around comparing and contrasting is the appropriate response.

Comparing and contrasting is also a useful approach in all kinds of academic writing : You might compare different studies in a literature review , weigh up different arguments in an argumentative essay , or consider different theoretical approaches in a theoretical framework .

If you’re not given a specific prompt for your descriptive essay , think about places and objects you know well, that you can think of interesting ways to describe, or that have strong personal significance for you.

The best kind of object for a descriptive essay is one specific enough that you can describe its particular features in detail—don’t choose something too vague or general.

If you’re not given much guidance on what your narrative essay should be about, consider the context and scope of the assignment. What kind of story is relevant, interesting, and possible to tell within the word count?

The best kind of story for a narrative essay is one you can use to reflect on a particular theme or lesson, or that takes a surprising turn somewhere along the way.

Don’t worry too much if your topic seems unoriginal. The point of a narrative essay is how you tell the story and the point you make with it, not the subject of the story itself.

Narrative essays are usually assigned as writing exercises at high school or in university composition classes. They may also form part of a university application.

When you are prompted to tell a story about your own life or experiences, a narrative essay is usually the right response.

The majority of the essays written at university are some sort of argumentative essay . Unless otherwise specified, you can assume that the goal of any essay you’re asked to write is argumentative: To convince the reader of your position using evidence and reasoning.

In composition classes you might be given assignments that specifically test your ability to write an argumentative essay. Look out for prompts including instructions like “argue,” “assess,” or “discuss” to see if this is the goal.

At college level, you must properly cite your sources in all essays , research papers , and other academic texts (except exams and in-class exercises).

Add a citation whenever you quote , paraphrase , or summarize information or ideas from a source. You should also give full source details in a bibliography or reference list at the end of your text.

The exact format of your citations depends on which citation style you are instructed to use. The most common styles are APA , MLA , and Chicago .

An argumentative essay tends to be a longer essay involving independent research, and aims to make an original argument about a topic. Its thesis statement makes a contentious claim that must be supported in an objective, evidence-based way.

An expository essay also aims to be objective, but it doesn’t have to make an original argument. Rather, it aims to explain something (e.g., a process or idea) in a clear, concise way. Expository essays are often shorter assignments and rely less on research.

An expository essay is a common assignment in high-school and university composition classes. It might be assigned as coursework, in class, or as part of an exam.

Sometimes you might not be told explicitly to write an expository essay. Look out for prompts containing keywords like “explain” and “define.” An expository essay is usually the right response to these prompts.

An expository essay is a broad form that varies in length according to the scope of the assignment.

Expository essays are often assigned as a writing exercise or as part of an exam, in which case a five-paragraph essay of around 800 words may be appropriate.

You’ll usually be given guidelines regarding length; if you’re not sure, ask.

Ask our team

Want to contact us directly? No problem. We are always here for you.

- Email [email protected]

- Start live chat

- Call +1 (510) 822-8066

- WhatsApp +31 20 261 6040

Our team helps students graduate by offering:

- A world-class citation generator

- Plagiarism Checker software powered by Turnitin

- Innovative Citation Checker software

- Professional proofreading services

- Over 300 helpful articles about academic writing, citing sources, plagiarism, and more

Scribbr specializes in editing study-related documents . We proofread:

- PhD dissertations

- Research proposals

- Personal statements

- Admission essays

- Motivation letters

- Reflection papers

- Journal articles

- Capstone projects

Scribbr’s Plagiarism Checker is powered by elements of Turnitin’s Similarity Checker , namely the plagiarism detection software and the Internet Archive and Premium Scholarly Publications content databases .

The add-on AI detector is powered by Scribbr’s proprietary software.

The Scribbr Citation Generator is developed using the open-source Citation Style Language (CSL) project and Frank Bennett’s citeproc-js . It’s the same technology used by dozens of other popular citation tools, including Mendeley and Zotero.

You can find all the citation styles and locales used in the Scribbr Citation Generator in our publicly accessible repository on Github .

The Difference between an Essay and a Story

There are several types of essays, and only a narrative essay resembles a story. The traditional length of a narrative essay would be comparable only to a short story in length.

A narrative essay is, in essence, a short version of a personal story from a writer's experience. In some ways, a narrative essay and a short story can feel similar to one another. Both require a certain amount of imaginative narrative from the writer and use descriptive words to convey emotions, lay out the scene, and place the reader inside the events.

However, there are quite a few differences, which is why you won't find a narrative essay in a compilation book of short stories.

Like all other forms of essays, a narrative essay needs a clear outline of ideas that organize the writer's thoughts. Essays will always include an introduction, a body of writing, and a conclusion that sums up the writer's points or describe what the writer learned from the experience they write about.

Short stories need no such structure. While there is technically a beginning, a middle, and an end, the linear structure of a narrative essay is often not followed in a short story. Some jump around in time and play with the reader's imagination to determine the sequence of events and how one event affects or leads to another.

Tell the Truth

One of the most notable differences between a narrative essay and a short story is that a short story does not always have to be true. A story can be fiction or non-fiction, as both fit the definition of a short story. A narrative essay, on the other hand, is expected by the reader to be an actual experience from the writer's life.

The intent of an essay is always to inform, so readers have an expectation that they will learn something by reading an essay regardless of its form. When reading a narrative essay, a reader expects to learn more on the topic being discussed through first-hand knowledge due to the lived experience of the writer.

The intent of a story is to entertain. Some short stories are fables, which include a moral that teaches a lesson. However, even the best lessons in short stories will not come across or even be remembered if the story itself isn't engaging and entertaining.

Stack Exchange Network

Stack Exchange network consists of 183 Q&A communities including Stack Overflow , the largest, most trusted online community for developers to learn, share their knowledge, and build their careers.

Q&A for work

Connect and share knowledge within a single location that is structured and easy to search.

What are the differences between narrative and descriptive writing?

What are the differences between narrative and descriptive writing? What should we keep in mind while writing it?

- 2 Can you clarify this question by telling us where you encountered these terms, and what the context is? This is difficult to answer otherwise. – Goodbye Stack Exchange Commented Jun 9, 2014 at 5:45

7 Answers 7

Narrative writing tells a story or part of a story.

Descriptive writing vividly portrays a person, place, or thing in such a way that the reader can visualize the topic and enter into the writer’s experience.

See here and here .

So in narrative writing, the writer is perfectly capable of telling you the plot of the story, while in descriptive writing there does not have to be a plot, but something has to become very easy for the reader to visualize.

Let's look at the Lord of the Rings. The way J.R.R. Tolkien describes a hobbit is very descriptive, and the reason the movies were so successful was not only because the story was told correctly (the book being narrative writing also), but because the readers did not have to come up with their own imagination of a hobbit (or other figures, places, and such). They were described in detail, giving everybody a very precise framework of imagination to work from. Therefore everybody could relate to and agree upon the characters and the make-up of the artists.

- @malach how do I know, that I should stop description and go on narration? – gaussblurinc Commented Apr 16, 2013 at 17:28

- 1 The 'here' and 'here' links a broken – alan Commented Mar 16, 2017 at 17:35

- Descriptive Writing paints pictures with words or recreates a scene or experience for the reader.

- Narrative Writing on the other hand, relates a series of events either real or imaginary or chronologically arranged and from a particular point of view.

For short, the descriptive is to describe and the narrative is to tell information.

Narrative - is when the author is narrating a story or part of a story. Usually, it has introduction, body and its conclusion. It let readers create their own imagination. It may be exact as what the author wants to express or not.

Descriptive - describing what the author wants to impart. It expresses emotion about its certain topic. It leads the way and not letting you fall out of nowhere.

Differences Narration often employs first person point of view, using words like "I" and "me," while other modes including description do not. The biggest difference between the two is that a narrative essay includes action, but the descriptive essay does not. Narration follows a logical order, typically chronological. In contrast, description typically contains no time elements, so organize descriptive essays by some other reasonable means, such as how you physically move around in a space or with a paragraph for each of the senses you use to describe.

The core of narrative writing is strong verbs. Descriptive writing might have some verbs, usually weak ones, but the main tools are nouns and adjectives.

Narrative writing involves the writer's personal experience and he tells it in the form of story.. e.g my first day at college descriptive writing involves the characters observed by five senses and does not contain a plot

- 1 Can you add a contrast to what descriptive writing is? And maybe provide some links to support this? – Nicole Commented May 12, 2015 at 18:42

- 2 Can you edit to expand this? We're looking for longer answers that explain why and how, not just one-liners. Thanks. – Monica Cellio Commented Jan 13, 2016 at 23:39

Narrative is the experience of the narrator in his own words whereas descriptive story is analysis of any topic desired..

- 3 "descriptive story is analysis of any topic desired" By that logic, an academic essay or a political polemic would be descriptive writing. – Goodbye Stack Exchange Commented Oct 27, 2014 at 2:49

- Featured on Meta

- Upcoming sign-up experiments related to tags

Hot Network Questions

- Is it unethical to have a videogame open on a personal device and interact with it occasionally as part of taking breaks while working from home?

- Can apophatic theology offer a coherent resolution to the "problem of the creator of God"?

- Is there some sort of kitchen utensil/device like a cylinder with a strainer?

- Proper way to write C code that injects message into /var/log/messages?

- A puzzle from YOU to ME ;)

- What is the purpose of the M1 pin on a Z80

- Is there an explicit construction of a Lebesgue-measurable set which is not a Borel set?

- Can a contract require you to accept new T&C?

- Why does Aemond focus on a coin in his room in "House of the Dragon" S02E02?

- How to join two PCBs with a very small separation?

- Redraw a Recurrent Neural Network

- Would a spaceport on Ceres make sense?

- My 5-year-old is stealing food and lying

- Can I replace a GFCI outlet in a bathroom with an outlet having USB ports?

- Why does c show up in Schwarzschild's equation for the horizon radius?

- Can a capacitor be used to close path between center-tap and shield instead of Bob-Smith (capacitor+resistor)?

- Does John 14:13 mean if we literally pray for anything God will act?

- How does a vehicle's brake affect the friction between the vehicle and ground?

- Did James Madison say or write that the 10 Commandments are critical to the US nation?

- Vespertide affairs

- Cut and replace every Nth character on every row

- Modify the width of each digit (0, 1, ..., 9) of a TTF font

- Are there really half-a billion visible supernovae exploding all the time?

- HTTP: how likely are you to be compromised by using it just once?

Narrative vs Descriptive Writing: Understanding the Key Differences

By: Author Paul Jenkins

Posted on May 13, 2023

Categories Storytelling , Writing

Narrative and descriptive writing are two of the most common writing styles used in literature. Both styles are used to convey a story, but they differ in their purpose and approach. Narrative writing is designed to tell a complete story, while descriptive writing conveys an intense description of a particular place, object, or concept.

Narrative writing involves telling a story with a beginning, middle, and end. It is often used in novels, short stories, and memoirs. Narrative writing can entertain, inform, or persuade the reader. It is a powerful tool for writers to convey their message and connect with their audience.

On the other hand, descriptive writing creates a vivid image in the reader’s mind. It is often used in poetry, descriptive essays, and travel writing. Descriptive writing allows the writer to use sensory details to create a picture in the reader’s mind. It is a powerful tool for writers to create a mood or atmosphere. Descriptive writing can entertain, inform, or persuade the reader.

Narrative Writing

Narrative writing is a style of writing that tells a story or describes an event. It can be fiction or non-fiction and is often written in the first-person point of view. The purpose of narrative writing is to entertain, inform or persuade the reader.

Narrative writing aims to engage the reader by telling a story that captures their attention. Narrative writing is often used in fiction writing, but it can also be used in non-fiction writing, such as memoirs or personal essays. The purpose of narrative writing is to create a vivid picture in the reader’s mind and make them feel like they are part of the story.

Narrative writing has several key elements that help to create a compelling story. These elements include characters, plot, point of view, narration, chronological order, action, setting, and theme. Characters are the people or animals that are involved in the story. The plot is the sequence of events that make up the story. Point of view is the perspective from which the story is told. Narration is how the story is told, such as first-person or third-person narration. Chronological order is the order in which events occur in the story. Action is the events that take place in the story. The setting is the time and place in which the story takes place. The theme is the underlying message or meaning of the story.

Examples of narrative writing include novels, short stories, and narrative essays. In fiction writing, the protagonist is the main character who drives the story forward. In a narrative essay, the writer tells a personal story that has a point or lesson to be learned. Narrative writing often uses first-person narration to create a more personal connection between the reader and the story.

In summary, narrative writing is a style of writing that tells a story or describes an event. It has several key elements that help to create a compelling story, including characters, plot, point of view, narration, chronological order, action, setting, and theme. Narrative writing can be used in fiction and non-fiction and is often used to entertain, inform, or persuade the reader.

Descriptive Writing

Descriptive writing is a type of writing that aims to provide a detailed description of a person, place, object, or event. It uses sensory details to create an image in the reader’s mind. The writer tries to make the reader feel like they are experiencing the scene.

Descriptive writing aims to create a vivid and detailed picture in the reader’s mind. It is often used to set the scene in a story or to provide a detailed description of a character or place. Descriptive writing can also create an emotional response in the reader.

Descriptive writing uses sensory details to create an image in the reader’s mind. It should be written in a logical order, so the reader can easily follow along. The following elements are commonly used in descriptive writing:

- Sensory detail (smell, taste, sight, sound, touch)

- Appearance and characteristics of the subject

- Description of the place or object

- Exposition of the subject

- Figurative language (metaphors, similes, onomatopoeia)

Here are a few examples of descriptive writing:

- The sun was setting over the mountains, casting a warm glow across the valley. The air was filled with the sweet scent of wildflowers and birds singing in the trees.

- The old house sat at the end of the street, its peeling paint and broken shutters a testament to its age. The front porch creaked as I stepped onto it, and the door groaned as I pushed it open.

- The chocolate cake was rich and decadent, with a moist crumb and a smooth, velvety frosting. Each bite was like a little slice of heaven, the flavors blending perfectly.

In conclusion, descriptive writing is a powerful tool for creating vivid and detailed images in the reader’s mind. The writer can transport the reader to another time and place using sensory details and logical order.

Narrative vs. Descriptive Writing

Differences.

Narrative writing and descriptive writing are two distinct forms of writing that have different purposes. Narrative writing is used to tell a story, while descriptive writing is used to describe something in detail. The following table summarizes some of the key differences between the two:

| Narrative Writing | Descriptive Writing |

|---|---|

| Tells a story | Describes something in detail |

| Has a plot, characters, and a setting | Focuses on sensory details |

| Can be fiction or non-fiction | Can be fiction or non-fiction |

| Often includes dialogue | Rarely includes dialogue |

| Has a beginning, middle, and end | Does not necessarily have a structure |

In narrative writing, the writer is trying to convey a specific message or theme through the story they are telling. In contrast, descriptive writing is more concerned with creating a sensory experience for the reader. Descriptive writing often uses figurative language, such as metaphors and similes, to create vivid images in the reader’s mind.

Similarities

Despite their differences, narrative writing and descriptive writing also share some similarities. Both forms of writing require the writer to use descriptive language to create a vivid picture in the reader’s mind. Both can also be used in both fiction and non-fiction writing.

Another similarity is that both forms of writing can create emotional connections with the reader. In narrative writing, this is achieved by creating relatable characters and situations. Descriptive writing is achieved by using sensory details to create a visceral experience for the reader.

In conclusion, while narrative writing and descriptive writing have different purposes, they require the writer to use descriptive language to create a vivid picture in the reader’s mind. Understanding the differences and similarities between these two forms of writing can help writers choose the appropriate style for their writing project.

Narrative Writing Techniques

Narrative writing is a form of storytelling that conveys a series of events or experiences through a particular perspective. This section will explore some of the key techniques used in narrative writing.

The narrator is the voice that tells the story. They can be a character within the story or an outside observer. The narrator’s perspective can greatly affect the reader’s interpretation of events. For example, a first-person narrator may provide a more personal and subjective account of events, while a third-person narrator may offer a more objective perspective.

Dialogue is the spoken or written words of characters within the story. It can reveal character traits, advance the plot, and provide insight into relationships between characters. Effective dialogue should sound natural and reflect the character’s personality and background.

Point of View