- Find a Lawyer

- Legal Topics

- Government Law

- Schools and Education Laws

- Due Process and School Suspension or Expulsio...

Due Process and School Suspension or Expulsion

(This may not be the same place you live)

Due Process and School Suspension or Expulsion

The Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution states that no person will be “deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law .” The 5th Amendment is more famous for containing the right against self-incrimination in criminal proceedings. But it also contains the admonition concerning due process of law. Over the years, courts have determined that this phrase contains within it two precepts. One is that government, federal, state, local, and any agency of government, must operate within the confines of the law and the other is that governments must take actions only within a context of fair procedures.

The Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution is called the “Due Process Clause” and it contains the same words as the Fifth Amendment to the same effect. All levels of government and all agencies of government must operate within the law and make decisions through the use of fair procedures.

The exact definition of procedures that are fair has been the subject of some discussion, but generally governments should make decisions only after giving the affected person notice, an opportunity to be heard, the right to review all of the evidence, the right to cross-examine adverse witnesses, a decision based exclusively on the evidence presented, the opportunity to be represented by counsel, preparation of a record of evidence presented, and a written findings of fact and reasons for its decision.

The point of requiring that governments provide due process when making decisions is to avoid government actions that are arbitrary and capricious. Procedural due process for students means that decisions affecting students in public educational institutions must include the same elements.

How Does Due Process Apply to Suspension or Expulsion in Schools?

Is due process required prior to an afterschool detention, what rights do i have in a school due process hearing, what happens if i am denied my right to due process, is there ever a time when i can be denied my right to due process, should i contact a lawyer.

Every student has the right to education and public education is an entitlement provided by agencies of local government. Whenever a student is deprived of his right to education through disciplinary actions such as suspension or expulsion, the student is entitled to due process.

This right to due process includes the right to notice and a fair hearing prior to the administration of long-term suspension or expulsion. Most states have laws regarding school suspension as do local school districts.

Whether full due process is required prior to an after-school detention may vary from state to state and school district to school district. After-school detention involves holding a student after dismissal has occurred for some period of time, usually quite brief. Full due process would probably not be required for after-school detention because it is not so significant as to require a formal hearing with evidence, findings of fact and a ruling.

Nonetheless, a school would be well advised to inform the student clearly of the violation for which they are being detained. Then the school would certainly want to communicate with the parent about the detention, informing them of the reason and the nature of the detention.

The school would want to know that the parent does not have any plan for the after-school period on any particular day that would make the detention inappropriate, e.g. a doctor’s appointment. If the parent were to object, the school should certainly discuss the situation with the parent and perhaps agree on an alternative disciplinary move that is acceptable to all parties. And if the student would miss their transportation, e.g. the school bus ride home, then the school would need to provide acceptable alternative transportation.

Understanding the steps of due process in schools in the context of an expulsion or suspension would first require reviewing both the law of the state in which the school is located and then the regulations of the local school district within which the school operates. Both parties would want to conform to state and local rules regarding suspension and expulsion, assuming, of course, that they are fair, and that any rules regarding due process procedures are fair. For example, in Montgomery County Public Schools, a school district in Maryland, the district’s rule limits out-of-school suspension to 10 days only.

If a long-term suspension is contemplated for a student, then usually the student is suspended temporarily until a due process hearing can be conducted. Local rules may determine for how long the student can be suspended before a formal hearing must be held. Usually it is a period of from 5 to 10 days but it could be as long as 30 days

A basic level of due process should be provided before the temporary suspension, e.g. a meeting including the student, their parents and school administrators, in which the circumstances leading to the suspension and the need for ongoing suspension pending a full hearing are discussed. Of course, the student and their parents must be given an opportunity to be heard at this meeting

The first step in any full hearing has to include notice to the student and their parents of the time, date and place of a hearing. Notice would also include a statement of the rule or rules that were violated and exactly how the rule was violated by the student. All long-term suspensions and expulsions must be reviewed in a formal hearing. The elements of due process at the hearing should include the following:

- A written notice of what specific rules were violated and how they were violated;

- Notice that the suspension/expulsion will be decided by an impartial, three-person panel;

- Notice to the effect that the student will have the opportunity to present evidence and witnesses on their own behalf;

- Notice that the student will be able to bring legal counsel or a non-attorney advocate;

- Notice that the he hearing will be closed to the public to protect the student’s privacy ;

- Notice that a written decision will be provided and when it will be provided.

Both sides to the dispute might want to be open to discussing alternatives to suspension or expulsion, e.g. reparation, community service, student participation in anger management counseling and the like.

The school would need to devise a plan that allowed the student to keep up with school work. This might be attendance at an alternative location or provision of assignments to the student by their regular teachers during the period of suspension. In any event, the school would want to take steps to ensure that the student is not deprived of their education during the suspension, especially if it is longer than a few days.

If a school official or the board of education denies a student their right to due process in connection with a suspension or expulsion, the student can use this as a defense to a suspension or expulsion decision. A denial of due process procedures is grounds for the reversal of a suspension or expulsion decision of the board of education and for the student’s immediate reinstatement to school.

An expelled or suspended student or their lawyer would review local school district rules and regulations regarding how to appeal a suspension/expulsion decision. A court will look to make sure the student exhausted administrative remedies before turning to the courts for relief. If local authorities cannot rectify the problem with respect to a failure to provide due process, then a student can seek relief in state court .

In an emergency situation, a student could be denied due process, but only temporarily. If the school believes that a student poses an immediate threat to themselves or others, the school staff can suspend the student immediately for up to ten days without giving the student a hearing. Of course, the school would want to communicate with parents about the problem and involve them in decision-making at the earliest possible opportunity.

Full due process procedures must be provided as soon as possible. Only in emergency situations can full due process be skipped following the application of discipline.

If you have questions regarding your due process rights, or if you believe you have been denied your right to due process in school, you may want to contact a government lawyer experienced in education and schools .

An experienced lawyer will be able to explain your rights to you and represent you in any appeals or administrative hearings that might be necessary. You are most likely to get the best possible outcome if you have an experienced lawyer representing your interests.

Need a Government Lawyer in your Area?

- Connecticut

- Massachusetts

- Mississippi

- New Hampshire

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- West Virginia

Susan Nerlinger

LegalMatch Legal Writer

Original Author

Susan is a member of the State Bar of California. She received her J.D. degree in 1983 from the University of California, Hastings College of Law and practiced plaintiff’s personal injury law for 8 years in California. She also taught civil procedure in the Paralegal program at Santa Clara University. She then taught English as a foreign language for eight years in the Czech Republic. Most recently, she taught English as a second language for Montgomery County Public Schools in suburban Washington, D.C. Now she devotes her time to writing on legal and environmental topics. You can follow her on her LinkedIn page. Read More

Jose Rivera

Managing Editor

Related Articles

- Advantages of Charter Schools

- Legal Rights of Children with Autism

- Education Rights of Students with Attention Deficit Disorder

- Zero Tolerance Policy in School

- Violations of Law at School

- Education Law: Truancy

- Education Law

- No Child Left Behind: Teacher Quality

- School Suspension Laws

- Student Discipline And Appeals Lawyers

- Student Discipline Lawyers

- Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act Lawyers

- How to Sue a School District in Wyoming?

- How to Sue a School District in Vermont?

- How to Sue a School District in Montana?

- How to Sue a School District in Maine?

- How to Sue a School District in New Hampshire?

- How to Sue a School District in Hawaii?

- How to Sue a School District in West Virginia?

- How to Sue a School District in Idaho?

- How to Sue a School District in Nebraska?

- How to Sue a School District in New Mexico?

- How to Sue a School District in Mississippi?

- How to Sue a School District in Kansas?

- How to Sue a School District in Arkansas?

- How to Sue a School District in Oregon?

- How to Sue a School District in Kentucky?

- How to Sue a School District in Louisiana?

- How to Sue a School District in Alabama?

- How to Sue a School District in Colorado?

Discover the Trustworthy LegalMatch Advantage

- No fee to present your case

- Choose from lawyers in your area

- A 100% confidential service

How does LegalMatch work?

Law Library Disclaimer

16 people have successfully posted their cases

- Trying to Conceive

- Signs & Symptoms

- Pregnancy Tests

- Fertility Testing

- Fertility Treatment

- Weeks & Trimesters

- Staying Healthy

- Preparing for Baby

- Complications & Concerns

- Pregnancy Loss

- Breastfeeding

- School-Aged Kids

- Raising Kids

- Personal Stories

- Everyday Wellness

- Safety & First Aid

- Immunizations

- Food & Nutrition

- Active Play

- Pregnancy Products

- Nursery & Sleep Products

- Nursing & Feeding Products

- Clothing & Accessories

- Toys & Gifts

- Ovulation Calculator

- Pregnancy Due Date Calculator

- How to Talk About Postpartum Depression

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

Due Process in Special Education Under the IDEA Law

Due process is a requirement under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) that sets forth a regulatory basis for a formal set of policies and procedures to be implemented by schools and districts for children in special education programs.

Due process is intended to ensure that children with learning disabilities and other types of disabilities receive a free appropriate public education. These policies and procedures are typically described in a school district's procedural safeguards statement and local policies. Procedural safeguards are sometimes referred to as parent rights statements.

Due process requirements were set forth in the IDEA with the intention that, if followed, they would help to facilitate appropriate decision making and services for children with disabilities.

Hearings for Aggrieved Parents

Special education due process hearing is one of three main administrative remedies available to parents under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 to resolve disagreements between parents and schools regarding children with disabilities.

Due process hearings are administrative hearings that are conducted, in many ways, like a court trial. Hearings may be held on behalf of individual students or groups of students, as in a class-action.

What Happens During a Hearing?

A due process hearing is similar to a hearing in civil court. Either party may be represented by an attorney or may present their cases themselves. The procedures and requirements for a due process hearing may vary depending on your state's specific administrative laws.

Generally, hearings occur because parents believe the child's individual education program (IEP) is not being implemented appropriately, their child has been denied a Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE), or they disagree with the school about which teaching methods would be appropriate for the child.

In other cases, parents believe the school district has failed to provide the necessary support services, such as speech, physical or occupational therapies , for the child. They may also believe they have tried to work with the district to resolve the problem but have not been successful. Sometimes, the disagreement has become so significant that it requires an impartial hearing officer (IHO) to resolve it.

How Due Process Hearings Unfold

The plaintiff or complainant gives an opening statement that details his or her allegations against the defendant or respondent. The plaintiff also has the burden of proof.

Both parties are provided an opportunity to state their cases. Each must prove any allegations are facts with adequate, admissible evidence, and supportive documentation.

Common types of evidence include the child's cumulative records and confidential special education files; referrals for assessment; assessment reports from the school or private evaluators. The child's IEP goals and objectives, progress reports; discipline reports, such as suspension and expulsion documentation; and attendance and grade reports; may also be evidence.

Both parties may prepare briefs to support their positions to submit to the IHO for consideration. Briefs typically include background information on issues involved with the case. For example, a parent of a child with autism may submit a brief detailing the effectiveness of augmentative communication.

Each party may subpoena witnesses to testify in person or via affidavit or deposition. Parties are given the opportunity to cross-examine any witnesses who testify during the hearing.

The hearing officer listens to the case presented by the parties and issues a formal decision based on case law. IHOs may rely on existing administrative laws, binding precedent and persuasive precedent to form their decisions on the matter.

Both parties have the option of appealing the ruling if they can present reasonable evidence that the hearing officer has made an error or that additional evidence has surfaced that may affect the outcome of the case.

Other Grievance Procedures

Parents may also pursue other grievance procedures. For example, they can seek an informal resolution to the problem by speaking with the principal or manager of the child's school, the special education administrator or a Section 504 administrator.

Additionally, they can file a complaint with the local board of education through the district superintendent or manager or file an IDEA formal complaint with the state's department of education. Some parents choose to file a Section 504 complaint with the U.S. Department of Education's Office of Civil Rights.

Lastly, they can request mediation from the state's department of education. Because due process hearings can be a lengthy and stressful process for all parties involved, pursuing other forms of resolution may be beneficial.

Lipkin PH, Okamoto J; Council on Children with Disabilities; Council on School Health. The Individuals With Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) for children with special educational needs . Pediatrics . 2015;136(6):e1650‐e1662. doi:10.1542/peds.2015-3409

U.S. Department of Education. Individuals With Disabilities Act. Section 1415 (f) .

U.S. Department of Education. Parent and educator resource guide to Section 504 in public elementary and secondary schools .

U.S. Department of Education. Office for Civil Rights. How the Office for Civil Rights handles complaints .

U.S. Department of Education. Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. Section 300.506 Mediation .

By Ann Logsdon Ann Logsdon is a school psychologist specializing in helping parents and teachers support students with a range of educational and developmental disabilities.

- Follow Us On:

- What is the CPIR?

- What’s on the Hub?

- CPIR Resource Library

- Buzz from the Hub

- Event Calendar

- Survey Item Bank

- CPIR Webinars

- What are Parent Centers?

- National RAISE Center

- RSA Parent Centers

- Regional PTACs

- Find Your Parent Center

- CentersConnect (log-in required)

- Parent Center eLearning Hub

Select Page

The Due Process Hearing, in Detail

So–we’ve arrived at the due process hearing , a longstanding option within IDEA for resolving disputes between parents and school systems. The two parties may have reached this point after unsuccessfully trying another of IDEA’s options for dispute resolution , or they may have waived those options and gone straight to the due process hearing. Regardless, the clock is now ticking on the timeline for holding a due process hearing and resolving their dispute. Let’s see what that involves. ____________________

Quick-Jump Links

To read IDEA’s exact words, visit IDEA’s Regulations on the Due Process Hearing .

Back to top ______________________________

How States Organize Their Due Process Systems

Before launching into a close look at the due process hearing, it’s helpful to know that states organize their due process systems in two different ways:

- one-tier, or

In a one-tier system , the SEA or another state-level agency is responsible for conducting due process hearings, and an appeal from a due process hearing decision goes directly to court.

In a two-tier due process system , the school district is responsible for conducting due process hearings, and an appeal from a due process hearing is to a state-level review hearing before appealing to court.

There are differences in the timelines for issuing decisions and rights of appeal for each of these systems.

Some stats on tiered systems | According to the findings of the Study of State and Local Implementation and Impact of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (SLIIDEA):

- 57% of the nation’s school districts use a one-tiered system (hearings held only at the state level),

- 43% use the two-tiered (hearings at the local level, with right to appeal to state-level hearing officer or panel). (O’Reilly, 2003)

The public agency’s procedural safeguards notice will provide information about the type of due process system used in the state. The notice should identify the agency that is responsible for conducting hearings (e.g., the school district, the SEA, or another state-level agency or entity).

Back to top

Organization of IDEA’s Due Process Provisions

IDEA’s due process provisions are as follows:

- Impartial due process hearing (§300.511);

- Hearing rights (§300.512);

- Hearing decisions (§300.513);

- Finality of decision, appeal, and impartial review (§300.514); and

- Timelines and convenience of hearings and reviews (§300.515).

All of these provisions are available in IDEA’s Regulations on the Due Process Hearing .

What’s a due process hearing, and what happens there?

There are times when the disputing parties have been unable or unwilling to resolve the conflict themselves, and so they proceed to a due process hearing. There, an impartial, trained hearing officer hears the evidence and issues a hearing decision.

During a due process hearing, each party has the opportunity to present their views in a formal legal setting, using witnesses, testimony, documents, and legal arguments that each believes is important for the hearing officer to consider in order to decide the issues in the hearing. Since the due process hearing is a legal proceeding, a party will often choose to be represented by an attorney.

Back to top

What rights does each party have in a due process hearing?

IDEA gives the disputing parties specific rights in a due process hearing. These rights are found at §300.512 and include the right to:

Be accompanied and advised by counsel and by individuals with special knowledge or training with respect to the problems of children with disabilities, except that whether parties have the right to be represented by non-attorneys at due process hearings is determined under State law.

Present evidence and confront, cross-examine, and compel the attendance of witnesses.

Stop any evidence from being introduced at the hearing that has not been disclosed to that party at least five business days before the hearing.

Get a written (or, at the option of the parents, electronic) verbatim record of the hearing.

Disclosure | At least five business days before a hearing conducted under §300.511(a), each party must disclose to all other parties all evaluations completed by that date and recommendations based on the offering party’s evaluations that the party intends to use at the hearing [§300.512(b)]. The hearing officer may prevent any party that fails to comply with this requirement from introducing the relevant evaluation or recommendation at the hearing without the consent of the other party.

Additional parent rights | IDEA gives parents additional rights in due process hearings. As identified at §300.512(c), these are the right to:

- have the child who is the subject of the hearing present,

- open the hearing to the public, and

- have the record of the hearing, and the findings of fact and decisions, provided to them at no cost. §300.512(c)

Who has the burden of proof in an IDEA due process hearing?

Burden of proof , as a legal term, refers to “the duty to prove disputed facts” (Harnett County, n.d.). In criminal cases, the burden of proof always rests on the prosecutors. In civil cases, the burden usually is carried by the party filing the complaint or bringing the action. In due process hearings, which party has the burden of proof (the parent or the public agency) varies from state to state and even, sometimes, within a state (Kerr, 2000). Thus, individuals involved in a due process hearing will need to find out how their state or locale addresses the question of burden of proof.

The question of which party has the burden of proof in an IDEA due process hearing—the parent or public agency—was addressed in the Supreme Court case Shaffer v. Weast (2005). While the IDEA is silent on the issue of burden of proof, the Supreme Court has held that, unless state law assigns the burden of proof differently, in general, the party who requests the hearing will have the burden of proving their case.

What qualifications must a hearing officer have?

The hearing officer has an important role as the individual who presides over a due process hearing. Not surprisingly, IDEA spells out a set of minimum qualifications that hearing officers must have. As listed at §300.511(c), this includes the following points.

The hearing officer must not be an employee of the SEA or the LEA involved in the education or care of the child.

The hearing officer must not have a personal or professional interest that conflicts with his or her objectivity in the hearing.

The hearing officer must have knowledge of, and the ability to understand, IDEA’s provisions, federal and state regulations pertaining to IDEA, and legal interpretations of IDEA made by federal and state courts.

The hearing officer must have the knowledge and ability to conduct hearings in keeping with appropriate, standard legal practice.

The hearing officer must have the knowledge and ability to render and write decisions in keeping with appropriate, standard legal practice.

What is the standard for the hearing officer’s decision?

It’s the hearing officer’s job to weigh the merits of each party’s argument, evidence, and witnesses, in light of what IDEA and state law require, also bearing in mind relevant federal and state regulations pertaining to the Act and legal interpretations of the Act by federal and state courts. The hearing officer must possess the knowledge and ability to conduct hearings in accordance with appropriate, standard legal practice. How does the hearing officer do this?

The regulations set forth the standard that must be applied when a hearing officer is deciding whether a child received FAPE. These requirements are found at §300.513(a) and read:

§300.513 Hearing decisions.

(a) Decision of hearing officer on the provision of FAPE . (1) Subject to paragraph (a)(2) of this section, a hearing officer’s determination of whether a child received FAPE must be based on substantive grounds.

(2) In matters alleging a procedural violation, a hearing officer may find that a child did not receive a FAPE only if the procedural inadequacies—

(i) Impeded the child’s right to a FAPE;

(ii) Significantly impeded the parent’s opportunity to participate in the decision-making process regarding the provision of a FAPE to the parent’s child; or

(iii) Caused a deprivation of educational benefit.

It’s interesting that IDEA’s provisions reference two contrasting words: substantive and procedural . A hearing officer’s decision on whether a child received FAPE must be made on “substantive grounds.” But due process hearings are also requested because of alleged procedural violations. IDEA and the final Part B regulations are very specific about when a hearing officer can find that there is a denial of FAPE as the result of an alleged procedural violation.

The essence of the contrast between substantive and procedural is well captured in the following explanation:

Substantive law consists of written statutory rules passed by legislature that govern how people behave. These rules, or laws, define crimes and set forth punishment.

Procedural law governs the mechanics of how a legal case flows, including steps to process a case. Procedural law adheres to due process, which is a right granted to U.S. citizens by the 14th Amendment. (Kadian-Baumeyer, n.d.)

So, under what circumstances would “procedural inadequacies” be sufficient for a hearing officer to find that a child did not receive FAPE?

According to IDEA, a hearing officer may so find when those procedural violations:

- impeded the child’s right to FAPE;

- significantly impeded the parent’s opportunity to participate in the decision-making process regarding the provision of FAPE to the parent’s child; or

- caused a deprivation of educational benefit. [§300.513(a)(2)]

What is the timeline for issuing the hearing decision?

Regardless of whether a state has a one- or two-tier system for handling due process hearings, the SEA or the public agency directly responsible for the child’s education (whichever agency is responsible for conducting the hearing in your state) must ensure that a final decision is reached in the hearing not later than 45 days after the 30-day resolution period expires (or any of the adjustments made to that period that were discussed in the separate article on Resolution Meetings ).

IDEA also states that:

A copy of the hearing officer’s decision must be mailed to each of the parties within the 45-day timeline, unless the hearing officer grants a specific extension of this timeline at the request of either party.

If the hearing officer’s decision is not appealed, it is final.

The school system must implement the hearing decision as soon as possible and, in any event, within a reasonable period of time. If it fails to do so, parents may seek court enforcement of an administrative decision. Parents may also file a state complaint with the SEA.

After personally identifiable information is deleted, due process hearing findings and decisions must be made available to the public. Many states have this information available in searchable online databases.

Findings and decisions in due process hearings, with the deletion of personally identifiable information, must also be transmitted to the state advisory panel established under §300.167.

Can the hearing officer’s decision be appealed?

Yes , it can be. But, as stated above, if it’s not appealed, the decision made by the hearing officer is final.

The specific actions required to appeal the hearing officer’s decision depend on what type of due process system (one-tier or two-tier) an SEA has, as described below.

Appealing in a one-tier system | In states using a one-tier system for due process hearings, the SEA is the entity that conducted the initial due process hearing and issued the decision. This means that, in a one-tier system, a state-level review of a hearing decision is not available. If one of the parties disagrees with the decision, the only “appeal” will be for the party to bring a civil action in an appropriate state or federal court. This will be discussed more fully after we take a look at appealing in a two-tier system.

Appealing in a two-tier system | In states that have a two-tier system, a state-level appeal to the SEA is available. This is because the initial due process hearing was conducted by the public agency directly responsible for the child’s education, so appeal to the SEA exists as an option. This is a longstanding provision of IDEA.

In such cases, the SEA must conduct an impartial review of the findings and decision in the hearing, as specified at §300.514(b). According to these provisions, the review conducted by the SEA:

- is based on examining the entire hearing record;

- must ensure that the procedures used in the original due process hearing were consistent with due process requirements; and

- may involve the SEA asking for additional evidence, if necessary, and holding a hearing to receive it.

If a hearing is held to receive additional evidence, the rights in §300.512 apply. These were discussed earlier and include the right to be accompanied and advised by counsel; the right to confront, cross-examine, and compel the attendance of witnesses; and so on.

IDEA uses slightly different language in referring to where and when hearings and reviews that involve oral arguments must be conducted. With respect to scheduling IEP meetings, the phrase IDEA uses is “mutually agreed on time and place.” The phrase IDEA uses with respect to scheduling hearings and reviews involving oral arguments is “reasonably convenient to the parents and child involved” [§300.515(d].

Why the difference? Why is there no requirement that the parties mutually agree to the hearing time and place?

In the Analysis of Comments and Changes, the Department responded to a public comment seeking clarification about the standard for determining the time and place for conducting hearings, stating:

The Department believes that every effort should be made to schedule hearings at times and locations that are convenient for the parties involved. However, given the multiple individuals that may be involved in a hearing, it is likely that hearings would be delayed for long periods of time if the times and locations must be ‘‘mutually convenient’’ for all parties involved. (71 Fed. Reg. 46707)

Okay, then, all the evidence is in. What happens next? As might be expected, the reviewing official must make an independent decision and issue findings of fact and decisions, providing a copy to both parties. Under §300.512(c)(3), the parent has the right to a copy of the findings of fact and decision on appeal in written or electronic form, at the parent’s option, at no cost.

Are there timelines for issuing a final decision in the review?

Yes . The SEA must ensure that, not later than 30 days after receiving a request for review, a final decision is reached in the review and a copy of the decision is mailed to the parties. This requirement is stated at §300.515(b). The 30-day timeline may be extended by the reviewing officer at the request of either party, as specified at §300.515(c).

Can the SEA’s decision be appealed?

Suppose that one of the parties is still not satisfied with the decision? Can the SEA’s decision be appealed? Yes, by bringing a civil action .

This is the same dispute resolution process mentioned just a bit ago when we were talking about one-tier due process systems where there is no right to appeal to the SEA for any party aggrieved by the decision in the initial hearing.

Who can bring a civil action, and what’s involved?

First, let us re-state, for clarity, who may bring a civil action. Under §300.516(a), a civil action may be brought by:

- any party aggrieved by the decision in a initial due process hearing in a one-tier State (where there is no right to appeal to the SEA); and

- any party aggrieved by the decision in the SEA-level review in a two-tier State (where an appeal of the initial hearing decision can be made to the SEA).

The civil action may be brought in a State court of competent jurisdiction (a State court that has authority to hear this type of case) or in a district court of the United States without regard to the amount in controversy.

Under a new provision in the statute and regulations, there is now a timeline for filing a civil action. Under §300.516(b), in a one-tier system, the party must bring the civil action within 90 days of the date of the hearing officer’s decision (or, if the state has established a different timeframe, within the time allowed under the state’s law). In a two-tier due process system, the civil action must be brought within 90 days from the date of the state review official’s decision (or, if the state has established a different timeframe, within the time allowed under the State’s law). It’s important to note that the public agency must, through the procedural safeguards notice, notify parents of the time period to file a civil action [§300.504(c)(12)].

In any civil action, the court receives the records of the administrative proceedings and hears additional evidence at the request of either party [§300.516(c)].

The court bases its decision on the preponderance of the evidence and grants the relief that the court determines to be appropriate [§300.516(c)(3)]. IDEA provides that the district courts of the United States have the authority to rule on actions brought under Part B of the IDEA without regard to the amount in controversy [§300.516(d)].

It’s also important to note that IDEA sets forth a “rule of construction” at §300.516(e) that pertains to civil actions. Under this rule of construction, a dissatisfied party may have remedies available under other laws that overlap with those available under the IDEA. However, in general, to obtain relief under those other laws, the dissatisfied party must first use the available administrative remedies under the IDEA (i.e., the due process complaint, resolution meeting, and impartial due process hearing procedures) before going directly into court (U.S. Department of Education, 2009, pp. 34-35).

Do parents have the right to represent themselves in an IDEA case in federal court?

Yes . Generally, federal law allows any person to represent themselves in federal court to protect their own federal rights. In Winkelman v. Parma City Sch. Dist. (2007), the U.S. Supreme Court held that non-lawyer parents of a child with a disability may represent themselves pro se (i.e., without an attorney) in federal court, because IDEA grants parents independent, enforceable rights that include the entitlement to a free appropriate public education (FAPE) for their child. Because parents have these rights under IDEA, they can bring and defend IDEA claims on their own and without an attorney in federal court.

May other individuals who are not attorneys help parents in a due process hearing and recover fees for their services?

The question naturally arises as to whether parents are entitled to recover fees for expert services. The straight answer: No.

The details: The U.S. Supreme Court decided this matter in Arlington Cent. Sch. Dist. Bd. of Educ. V. Murphy (2006). In that case, the court held that section 1415(i)(3)(B) of the statute, which authorizes courts to award reasonable attorneys’ fees to parents who are prevailing parties in actions or proceedings brought under the IDEA, does not authorize recovery of fees for experts’ services.

Arlington Cent. Sch. Dist. Bd. Of Educ. v. Murphy, 548 U.S., 126 S.Ct. 2455 (2006). (The decision is available online at: http://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/05-18.ZO.html )

Harnett County, North Carolina. (n.d.) Legal glossary: A guide to commonly used legal terms . Retrieved on November 29, 2017, at http://www.harnett.org/clerk/legal-glossary.asp

Kadian-Baumeyer, K. (n.d.). Substantive law vs. procedural law: Definitions and differences (Chapter 4, Lesson 3). Retrieved November 29, 2017 from the Study.com website: http://study.com/academy/lesson/substantive-law-vs-procedural-law-definitions-and-differences.html

Kerr, S. (2000, September). Special education due process hearings . Retrieved November 29, 2017, at www.harborhouselaw.com/articles/dp.kerr.htm

O’Reilly, F. (2003, April). Dispute resolution: Year 1 survey findings and Year 1 and 2 focus study findings . Paper presented at the annual meeting of the IDEA Part B Data Managers, Arlington, Virginia.

Shaffer v. Weast, 546 U.S. 49 (2005). (The decision is available online at: http://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/04-698.ZO.html )

U.S. Department of Education. (2009, June ). Model form: Procedural safeguards notice . Washington, DC: Author. (Quote from pp. 34-35. Available online at: http://idea.ed.gov/download/modelform_Procedural_Safeguards_June_2009.pdf )

Winkelman v. Parma City Sch. Dist., 127 S.Ct. 1994 (2007). Read all about it at: https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/publishing/preview/publiced_preview_briefs_pdfs_06_07_05_983_Petitioner.authcheckdam.pdf

Back to top ________________________________________________________

**Highly Rated Resource! This resource was reviewed by 3-member panels of Parent Center staff working independently from one another to rate the quality, relevance, and usefulness of CPIR resources. This resource was found to be of “High Quality, High Relevance, High Usefulness” to Parent Centers. ________________________________________

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

8 IDEA Principle – Due Process

Aligned Standards

CEC Initial Preparation

1.1 6.1 6.2 6.5

DEC Preparation

1.2 6.3 7.4

Although those familiar with special education will recognize a due process hearing as one way to resolve a dispute between an individual’s parents/guardians and their school division, due process in this case refers to the broader constitutional right of all individuals to have access to the legal system and be assured fair procedures within the legal system. Both the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution assert that no one shall be “deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law”. Until the case Goss v. Lopez (1975), the Supreme Court had not considered whether education was protected with due process rights.

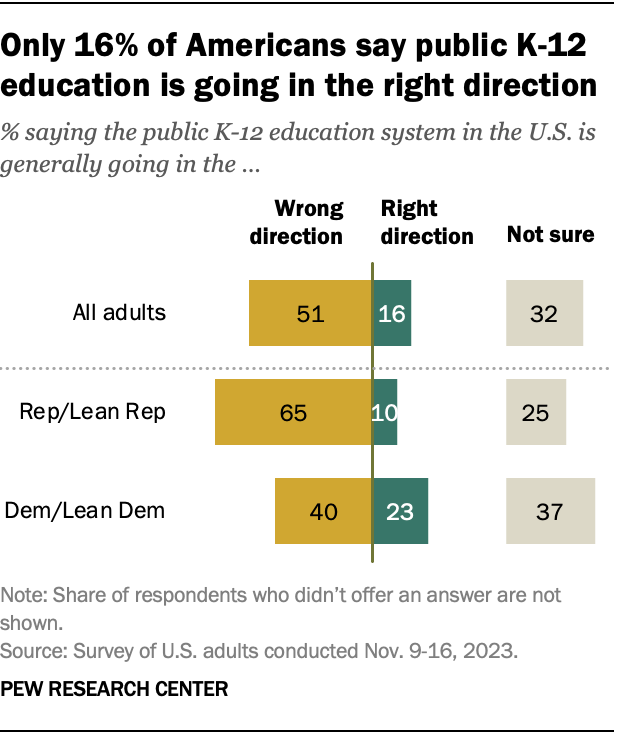

IDEA ensures that dispute resolution is available to parents/guardians and others associated with individuals with disabilities, but are all parents aware of these rights and do they have the resources to promote their interests in dispute resolution? This Government Accountability Office report, IDEA Dispute Resolution Activity in Selected States Varied Based on School Districts’ Characteristics (2019) indicated that the use of dispute resolution procedures was three to five times greater in high income school divisions than in low income school divisions.

federal law

IDEA §1415 Procedural Safeguards – Procedural safeguards are rules that protect both parents/guardians and school divisions by making clear the roles and responsibilities of each party in certain interactions regarding individuals with disabilities. In Part B of the IDEA regulations, Subpart E Procedural Safeguards Due Process Procedures for Parents and Individuals details the procedural safeguards available to parents/guardians and school divisions.

Goss v. Lopez (1975) is a Supreme Court case that established education as both a property and a liberty right under the Constitution. Goss v. Lopez answered the question of whether students, many of whom have not reached the age of majority, have due process rights in school disciplinary matters. This case arose when nine students in Ohio who attended demonstrations on school property were suspended without hearings. They joined together under the name of student Dwight Lopez in a class action lawsuit against Norval Goss, the director of pupil personnel of the Columbus Ohio Public School System. Goss appealed a lower court’s decision to the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court held that individuals facing temporary suspension from a public school have property and liberty rights under the due process clause of the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

Honig v. Doe (1988) served to confirm the limit on the number of days a student with an IDEA-covered disability could be removed from school through suspension. Prior to this Supreme Court case, individuals with disabilities were routinely suspended from schools without due process protections, endangering their right to a free appropriate public education (FAPE). High school students Doe and Smith were individuals with emotional disabilities who were suspended from school indefinitely due to disruptive conduct related to their disability and were facing expulsion. Honig was the state superintendent of public education in California. While the Education of the Handicapped Act (1970) regulations (precursor to IDEA) allowed temporary suspension of up to 10 days for students who were a danger to others, the statute also contained a “stay-put” provision that held that individuals with disabilities would remain in their current educational placements during any disciplinary proceedings. Both rules were meant to protect individuals with disabilities from a change of placement that would deny them a FAPE. The Supreme Court ruling confirmed that a suspension of more than 10 days was a change of placement. This sent a clear message to schools that longer suspensions and expulsions required procedures to protect the FAPE rights of individuals with disabilities when a change of placement was effected.

- Discipline procedures (8VAC20-81-160) : As a general rule, individuals with disabilities are accorded the same due process rights as all individuals under state and local disciplinary policies and procedures. However, individuals with disabilities have additional due process rights. First, when an individual with a disability has behaviors that impede their own or others’ learning, the IEP team must “consider use of positive behavioral interventions, strategies, and supports to address the behavior” (8VAC20-81-160). Secondly, when an individual with a disability violates the school code of conduct, school personnel may consider unique circumstances when determining whether to order a change in placement in response to the violation.

- Suspensions / Short-term Removals (8VAC20-81-160) : As we saw affirmed in Goss v. Lopez, ten days of suspension is the threshold for a suspension, also called a short-term removal. The discipline procedures give further detail, confirming that a short-term removal is for “a period of time of up to 10 consecutive school days or 10 cumulative school days in a school year” (8VAC20-81-160). School divisions are then advised as to the situations in which they are required to continue to provide services to an individual under a short term removal.

- Suspensions / Long-term Removals (8VAC20-81-160) : A long term removal can be defined in two ways: removal from school for more than 10 consecutive school days or a series of short term removals that constitute a pattern. A pattern is identified when three conditions are met: a. removals of more than 10 school days in a school year; b. the individual evidences similar behavior to previous incidents; and c. additional factors like the length of each removal, total amount of time removed, and the proximity of the removals to one another. The school division will decide whether a pattern of removals constitutes a change in placement (8VAC20-81-160). A change of placement triggers due process procedures and consents designed to protect an individual’s FAPE. Long-term removals incur additional decision points and procedures for school divisions regarding services to be provided, whether the behavior in question is a manifestation of the individual’s disability, any special circumstances, and an opportunity for parents/guardians to appeal some decisions in the process.

- Transfer of Rights to individuals who reach the age of majority (8VAC20-81-180) : All rights accorded to the parent(s) under the Act transfer to the individual upon the age of majority (age 18), including those individuals who are incarcerated in an adult or juvenile federal, state, regional, or local correctional institution. School divisions are required to give notice to the parents, include a statement on the individual’s IEP in advance of the transfer of rights, give required notices to both individual and parents, and may invite the individual’s parents to meetings. The adult individual may also invite their parents. The adult individual is presumed to be competent unless certain actions have been taken to certify them otherwise.

- Mediation (8VAC20-81-190) : When a parent/guardian and school division have a dispute about Part B entitlements for an individual with a disability, a mediation can be held to provide resolution. Virginia school divisions are required to inform parents of the availability of mediation services through the Virginia Department of Education (VDOE). A joint request from parent/guardian and school division is required to begin the mediation process. The process must be voluntary on both parties’ parts, not used to deny or delay a parent’s right to a due process hearing or other rights, and conducted by a trained, qualified, and impartial mediator. If a parent chooses not to use mediation, a school division is permitted to hold a meeting to encourage mediation. The VDOE must meet criteria for the management of mediators, the conduct of the mediation meetings, and the qualifications of individuals who serve as mediators.

- Co mplaint resolution procedures (8VAC20-81-200) : The complaint resolution system investigates complaints and issues findings regarding the rights of parents or individuals with disabilities. Any individual may file a complaint as long as it is in writing, signed, includes contact information, states that a school division has violated IDEA or the Virginia regulations, and includes facts to support the statement. If the complaint concerns a specific individual, identifying information and relevant documents are required. The action causing the complaint must have occurred within a year of the date of the complaint and the school division or public agency serving the individual must be notified simultaneously. The VDOE will determine whether the submitted complaint is complete within seven days of receipt and provide notice and directions for resubmission if it is not.

- Due process hearing (8VAC20-81-210) : The phrase due process hearing appears in the Virginia regulations over 90 times and with good reason: a due process hearing may be convened to yield a final decision at the level of the Virginia Department of Education for parents/guardians and school divisions with disputes over the identification, services, discipline, evaluation, placement, and provision of FAPE to individuals with disabilities. The VDOE provides an impartial special education due process hearing system using the impartial hearing officer system administered by the Supreme Court of Virginia. The VDOE provides training, certification, and recertification for a select number of individuals who become special education hearing officers.

- Fairfax County, VA Special Education Procedures website describes the the child find process, local screening information, initial evaluations, eligibility determination and those related to the individualized education program (IEP) and offers translation of several languages.

- VDOE Guidance for Due Process – VDOE Website “Special Education Due Process Hearings” describes the process and provides the documents required for due process. Due process hearing officer decisions are available for years 2001-2002 to the present.

- List of Due Process Hearing Officers

- Implementation Plan

- Legal / Advocacy Groups and Resources for Special Education

- Navigating the Maze of Due Process

- Parents’ Guide to Special Education Dispute Resolution (PDF)- This VDOE document Parents’ Guide to Special Education Dispute Resolution describes the options and processes for resolving disputes in parent-friendly language.

- Center for Appropriate Dispute Resolution in Special Education (CADRE) guide to IDEA Special Education Resolution Meetings (PDF) – This CADRE document describes the special education resolution meeting in parent-friendly language.

- Managing the Timeline in Due Process Hearings Guidance Document for Special Education Hearing Officers This VDOE guidance document is for special education hearing officers and describes the process of a due process case in detail.

- Your Family’s Special Education Rights –This document is Virginia’s procedural safeguards notice designed to satisfy the IDEA special education procedural safeguards requirements. It is also available in Spanish , Arabic , Chinese , Urdu , Farsi , Korean, and Vietnamese .

- IDEA Dispute Resolution Activity in Selected States Varied Based on School Districts’ Characteristics – IDEA ensures that dispute resolution is available to parents/guardians and others associated with individuals with disabilities, but are all parents aware of these rights and do they have the resources to promote their interests in dispute resolution? This Government Accountability Office report, IDEA Dispute Resolution Activity in Selected States Varied Based on School Districts’ Characteristics (2019) indicated that the use of dispute resolution procedures was three to five times greater in high income school divisions than in low income school divisions.

- Project Implicit is a non-profit organization that provides an Implicit Association Test so that people can recognize implicit biases.

Discussion / Reflection Questions :

- Why is protecting the rights of school divisions also important?

- Why is it important that parents and school divisions first try to resolve their disputes at informal levels like an IEP meeting?

Please use this Google Form to provide your feedback to authors about content, accessibility, or broken links.

Introduction to Special Education Resource Repository Copyright © 2023 by Serra De Arment; Ann S. Maydosz; Kat Alves; Kim Sopko; Christan Grygas Coogle; Cassandra Willis; Roberta A. Gentry; and C.J. Butler is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

What is a special education due process hearing?

The Special Education Due Process Hearing is a legal process you can use as the last resort when you disagree with the school. Learn more.

The Special Education Due Process Hearing is a legal process you can use as the last resort when you disagree with the school about special education.

This is a formal process and is like a lawsuit. A trained, neutral Court officer will listen to both sides, review the evidence, and then make a decision.

What should happen before I think about a Due Process hearing?

Before you take this step, go through the other steps of Special Education Dispute Resolution: meet with the school again, ask for a facilitated IEP, ask for mediation, and file a complaint with the school district. If you can resolve your conflict through those means, it will be much easier.

Consider getting help from a lawyer. It’s not required, but it is strongly recommended. The special education laws are complicated. A lawyer can help you to prepare a strong case and get what is best for your child. See this section below on getting legal help.

Either you, your lawyer, or the school can start this process.

How to file for a Special Education Due Process Hearing

- Find the Due Process instructions and Hearing Request form. You can download them from your state’s Department of Education website, find the details in the Procedural Safeguards manual, or ask the school principal or IEP team.

- Fill out the Hearing Request Form. Be sure to carefully describe your concerns and what you think the solutions should be. You must list all of your concerns here, because the hearing can only address the issues you list on this form.

- Send the signed written request to the special education director or superintendent of the school district.

- Make a copy of the form for yourself and keep it somewhere safe, like your IEP Binder .

- Send a copy to your state’s educational complaint office.

The request must be made within 1 year of the date that you knew of–-or should have known of-–the action you are complaining about.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Hearing process is run by the Louisiana Department of Education Legal Division. The Hearing Officer is called an Administrative Law Judge (ALJ).

Due Process Hearing Instructions . The Hearing Request Form is also on this page.

Send copy of form to:

Louisiana Department of Education, Attn: Legal Division

P. O. Box 94064

Baton Rouge, LA 70804-9064

Louisiana’s Procedural Safeguards (Educational Rights) See pages 15-20 for more on the Hearing and Dispute Resolution process.

Massachusetts:

The Hearing process is run by the Bureau of Special Education Appeals (BSEA), and is also called a BSEA Hearing.

How to file for a Due Process Hearing : Includes link to form and also how to file by mail, fax or in person.

Hearing Request Form

What happens at a BSEA Hearing

What happens after you request a Due Process Hearing?

The office will assign you a Hearing Officer, who will guide you through the process and represent you at the meeting. This officer will bring everyone together to clarify the problem, schedule the hearing, and try to find other resolution options before the hearing.

They may suggest a pre-hearing conference to see if you can all resolve the disagreement before you continue with the hearing. If you have a lawyer, they can come with you.

You may talk about:

- Clarifying the issues

- Areas where you agree and disagree

- Ideas for solutions

- Timing for exchanging information and documents

- Details for the hearing: scheduling, length, and getting an interpreter if needed

If English is not your first language, you have the right to a qualified interpreter. You must let the team know before the meeting. Interpreting services are free for families.

Have the Resolution Meeting with the school

- The school district is required to set up a resolution meeting with you within 15 calendar days of getting your hearing request. This is one step toward reaching an agreement.

- The school district has 30 calendar days after your hearing request, to work with you to reach an agreement before a hearing takes place.

- You are required to be at the resolution meeting unless you and the school district both agree in writing not to have it. You can agree not to have the resolution meeting if you have already reached a solution OR you are continuing the mediation process .

- If the school district is not willing to have a resolution meeting and it has been more than 15 calendar days since they got your request, then you can ask the hearing officer to move forward with the Due Process Hearing.

The resolution meeting may result in a Settlement Agreement, or you will all continue with the hearing.

A Settlement Agreement is a statement of what you agreed to. If you change your mind, you and the school have 3 business days to cancel it. After that, the agreement is official. They can enforce this in court if you end up in a lawsuit.

You should always have an attorney review this agreement. The legal language can be confusing and you want to make sure you don’t waive any of your rights.

How to prepare for the Due Process Hearing

It’s important to be ready for your hearing. This means having your documents ready, and knowing your rights and the different ways you can present your case.

At any due process hearing, you have the right to:

- Bring a lawyer or advocate to advise and represent you.

- Bring your child to the hearing.

- Present evidence like documents and reports.

- Have witnesses come to the hearing and answer questions. You also have the right to issue a subpoena, which is a document that requires them to come.

- See any evidence that will be used at the hearing at least 5 business days ahead of time (If you have not seen it ahead of time, you can ask the hearing officer to not allow it).

- This is a word-for-word record of everything people said at the hearing.

- You can get it electronically or on paper.

- It is free, but you must ask for it in writing.

Some things you and your lawyer may do:

- If you request a motion, you must submit a copy to the school. The school has 7 business days to respond. Then, the hearing officer will respond to your request in writing soon afterwards.

- At least 10 days business days before the hearing, you may ask the Education Office to issue a subpoena for anyone you want to speak at the hearing to support your case. This request must be in writing.

- Put the exhibits in a 3-ring binder

- Number each document

- Include a table of contents that explains each document

- Follow the instructions from the Education Office on how to submit your exhibits

- Make a list of all the witnesses who you are planning to have at the hearing.

- Make sure they really know your child so they can accurately talk about your child’s skills, strengths, and abilities.

- Send each witness the time and place so they can be ready.

- Tell the school and hearing officer if there are conflicts with your witnesses’ schedules.

What to expect at the Hearing

It may be slightly different in different courts, but here’s what happens in general:

- The hearing officer will ask if there are any logistical issues. Tell the officer now if there is anything that might affect the flow of the meeting. For example: scheduling conflicts for your witnesses, if you might need a break for medical reasons, if you have any problems with your supporting documents, etc.

- The officer will welcome everyone and read a formal opening statement. The hearing will be recorded.

- The officer will take your documents and put them into the record as official exhibits.

- You and the school will each give opening statements. If you have a lawyer, they will do this for you.

- You will present your witnesses one by one. You or your lawyer will ask them questions. You may also testify yourself. When someone testifies, they will take a formal oath and swear to tell the truth.

- Next, the school or their lawyer will ask your witnesses questions. The hearing officer might also ask questions.

- This process will repeat for the school’s witnesses.

- When all the witnesses are finished, the officer will ask if both sides would like to make a closing statement. Then, the hearing will end.

What happens next?

- They might not make a decision right away. You and the school district will get the decision in the mail, usually about 45 calendar days after the hearing.

- A hearing officer may grant an extension beyond 45 calendar days if either party requests it.

- This decision is final, unless you or the school appeal it and take it to the state or federal court. Otherwise, both you and the school district must follow the decision.

How do they make the decision?

The decision is based on the federal and state special education laws and regulations.

According to federal law, all children have a right to a Free and Appropriate Public Education (FAPE) in the Least Restrictive Environment (LRE) .

The hearing officer will consider all of the evidence and the testimony of the witnesses. Based on this, they will decide if your child’s special education rights were violated, or if the school district failed to fulfill its obligations to your child.

They may find that your child did not receive a FAPE if they find that the school’s actions:

- Impeded your child’s right to a FAPE

- Significantly impeded your opportunity to participate in the decision-making process, or

- Deprived your child of educational benefits

If you or the school disagrees with the decision, either of you can appeal it to the state or federal court.

- Get help from a lawyer who specializes in special education law. They can help you file the appeal, prepare your case, and represent you in court.

- File your appeal within 90 days of the hearing officer’s decision.

How to get legal help (even if you can’t afford a lawyer)

You may need to find a lawyer to help you resolve a dispute with the school about special education. This is especially true if you file for a Due Process Hearing.

There are 2 ways to get legal help:

- Get free or low cost legal advice from an advocacy organization.

- Hire a lawyer to represent you in the process.

Legal Advice:

There are many organizations that help families navigate legal problems with special education. They should be able to give you free advice and maybe free or low cost legal help.

Start with the National Disability Rights Network . Look up the legal advocacy organizations in your state and talk to them first.

Hiring a lawyer:

It’s best to find one who has lots of experience with special education laws and regulations.

Choose a lawyer who lists one of these as their specialty:

- Special Education

- Education Law

Be sure to ask in advance about fees. Fees will vary based on each lawyer’s experience and how complex the case is. The organizations you find through the National Disability Rights Network should be able to help you find a lawyer.

Legal advice:

- The Advocacy Center of LA provides free services. Call their hotline at 800-960-7705.

- The Louisiana Civil Justice Center offers a free legal hotline with brief advice and attorney referrals. Call 800-310-7029, Monday-Friday 9am-4pm.

- Louisiana State Bar Legal Education and Assistance Program provides a search directory by parish that includes legal aid organizations. Scroll to the bottom of the page and select your parish.

- The Southeast Louisiana Legal Services provides legal aid to low-income people. Visit their website to find contact information for an office located near you.

- The courts may also provide some legal assistance but there is no guarantee.

- You can contact the Louisiana Dept. of Education and ask if they can help you find free or low-cost legal assistance.

- Use our Disability Services Finder . Look in the Legal category under Services.

- Search for lawyers in your parish through the Disabilities Assistance Network . This list isn’t comprehensive; the people listed here have asked to be included.

- Check with the Louisiana Bar Association’s Referral Service . In New Orleans you can call 504-561-8828; in Baton Rouge you can call 225-344-9926.

- You can also call the Louisiana Bar Association at 1-800-421-5722 for help finding a lawyer in your area.

- Special Needs Alliance: Louisiana Listings .

- Use our Disability Service Finder . Look in the Legal category under Services.

Reminder: We do not endorse any of the lawyers listed through these resources. We are simply providing links to databases for your reference. Legal fees will vary depending on the complexity of your case.

The organizations below can help you find a lawyer. If you are concerned about costs, ask about free legal help.

Children’s Law Center of Massachusetts (Lynn)

Phone: (781) 581-1977; (888) 543-5298

Email: [email protected]

Disability Law Center, Inc. (Boston)

Phone: (617) 723-8455, (800) 872-9992, (617) 227-9464 (TTY), (800) 381-0577 (TTY)

Email: [email protected]

Greater Boston Legal Services (Boston)

Phone: (617) 371-1234

Massachusetts Advocates for Children (Boston)

Phone: (617)-357-8431 ext. 3224

Special Needs Advocacy Network, Inc. (North Attleboro)

Phone: (508) 655-7999, 617-388-3638

Email: [email protected]

The Bureau of Special Education Appeals (BSEA) also has information on finding legal help .

As you can see, the Special Education Due Process Hearing is a pretty complicated process. Clearly, it’s best if you can avoid it by using the other forms of Dispute Resolution . But if you need to take this step, follow these guidelines and get good support from a lawyer. Your child’s needs are important, and worth advocating for!

Learn More:

- Conflict resolution in special education: solving disagreements with the school

- Know your rights – What is IDEA?

- How to advocate for your child with a disability…and get results

More about the Special Education Due Process Hearing

Check out our page: Special Education Hub

Where you will find links to more articles on this topic.

Interested in our other resources for families?

Check out our landing page for families to see more of the topics we cover and learn more about Exceptional Lives.

- due process

Primary tabs

Introduction.

The Constitution states only one command twice. The Fifth Amendment says to the federal government that no one shall be "deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law." The Fourteenth Amendment , ratified in 1868, uses the same eleven words, called the Due Process Clause, to describe a legal obligation of all states. These words have as their central promise an assurance that all levels of American government must operate within the law ("legality") and provide fair procedures. Most of this article concerns that promise. We should briefly note, however, three other uses that these words have had in American constitutional law.

Incorporation

The Fifth Amendment's reference to “due process” is only one of many promises of protection the Bill of Rights gives citizens against the federal government. Originally these promises had no application at all against the states; the Bill of Rights was interpreted to only apply against the federal government, given the debates surrounding its enactment and the language used elsewhere in the Constitution to limit State power. (see Barron v City of Baltimore (1833)). However, this changed after the enactment of the Fourteenth Amendment and a string of Supreme Court cases that began applying the same limitations on the states as the Bill of Rights. Initially, the Supreme Court only piecemeal added Bill of Rights protections against the States, such as in Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad Company v. City of Chicago (1897) when the court incorporated the Fifth Amendment's Takings Clause into the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court saw these protections as a function of the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment only, not because the Fourteenth Amendment made the Bill of Rights apply against the states. Later, in the middle of the Twentieth Century, a series of Supreme Court decisions found that the Due Process Clause "incorporated" most of the important elements of the Bill of Rights and made them applicable to the states. If a Bill of Rights guarantee is "incorporated" in the "due process" requirement of the Fourteenth Amendment, state and federal obligations are exactly the same. For more information on the incorporation doctrine, please see this Wex Article on the Incorporation Doctrine .

Substantive due process

The words “due process” suggest a concern with procedure rather than substance, and that is how many—such as Justice Clarence Thomas, who wrote "the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause is not a secret repository of substantive guarantees against unfairness" —understand the Due Process Clause. However, others believe that the Due Process Clause does include protections of substantive due process—such as Justice Stephen J. Field, who, in a dissenting opinion to the Slaughterhouse Cases wrote that "the Due Process Clause protected individuals from state legislation that infringed upon their ‘privileges and immunities’ under the federal Constitution” (see this Library of Congress Article: https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/magna-carta-muse-and-mentor/due-process-of-law.html )

Substantive due process has been interpreted to include things such as the right to work in an ordinary kind of job, marry, and to raise one's children as a parent. In Lochner v New York (1905), the Supreme Court found unconstitutional a New York law regulating the working hours of bakers, ruling that the public benefit of the law was not enough to justify the substantive due process right of the bakers to work under their own terms. Substantive due process is still invoked in cases today, but not without criticism (See this Stanford Law Review article to see substantive due process as applied to contemporary issues).

The promise of legality and fair procedure

Historically, the clause reflects the Magna Carta of Great Britain, King John's thirteenth century promise to his noblemen that he would act only in accordance with law (“legality”) and that all would receive the ordinary processes (procedures) of law. It also echoes Great Britain's Seventeenth Century struggles for political and legal regularity, and the American colonies' strong insistence during the pre-Revolutionary period on observance of regular legal order. The requirement that the government function in accordance with law is, in itself, ample basis for understanding the stress given these words. A commitment to legality is at the heart of all advanced legal systems, and the Due Process Clause is often thought to embody that commitment.

The clause also promises that before depriving a citizen of life, liberty or property, the government must follow fair procedures. Thus, it is not always enough for the government just to act in accordance with whatever law there may happen to be. Citizens may also be entitled to have the government observe or offer fair procedures, whether or not those procedures have been provided for in the law on the basis of which it is acting. Action denying the process that is “due” would be unconstitutional. Suppose, for example, state law gives students a right to a public education, but doesn't say anything about discipline. Before the state could take that right away from a student, by expelling her for misbehavior, it would have to provide fair procedures, i.e. “due process.”

How can we know whether process is due (what counts as a “deprivation” of “life, liberty or property”), when it is due, and what procedures have to be followed (what process is “due” in those cases)? If "due process" refers chiefly to procedural subjects, it says very little about these questions. Courts unwilling to accept legislative judgments have to find answers somewhere else. The Supreme Court's struggles over how to find these answers echo its interpretational controversies over the years, and reflect the changes in the general nature of the relationship between citizens and government.

In the Nineteenth Century government was relatively simple, and its actions relatively limited. Most of the time it sought to deprive its citizens of life, liberty or property it did so through criminal law, for which the Bill of Rights explicitly stated quite a few procedures that had to be followed (like the right to a jury trial) — rights that were well understood by lawyers and courts operating in the long traditions of English common law. Occasionally it might act in other ways, for example in assessing taxes. In Bi-Metallic Investment Co. v. State Board of Equalization (1915), the Supreme Court held that only politics (the citizen's “power, immediate or remote, over those who make the rule”) controlled the state's action setting the level of taxes; but if the dispute was about a taxpayer's individual liability, not a general question, the taxpayer had a right to some kind of a hearing (“the right to support his allegations by arguments however brief and, if need be, by proof however informal”). This left the state a lot of room to say what procedures it would provide, but did not permit it to deny them altogether.

Distinguishing due process

Bi-Metallic established one important distinction: the Constitution does not require “due process” for establishing laws; the provision applies when the state acts against individuals “in each case upon individual grounds” — when some characteristic unique to the citizen is involved. Of course there may be a lot of citizens affected; the issue is whether assessing the effect depends “in each case upon individual grounds.” Thus, the due process clause doesn't govern how a state sets the rules for student discipline in its high schools; but it does govern how that state applies those rules to individual students who are thought to have violated them — even if in some cases (say, cheating on a state-wide examination) a large number of students were allegedly involved.

Even when an individual is unmistakably acted against on individual grounds, there can be a question whether the state has “deprive[d]” her of “life, liberty or property.” The first thing to notice here is that there must be state action. Accordingly, the Due Process Clause would not apply to a private school taking discipline against one of its students (although that school will probably want to follow similar principles for other reasons).

Whether state action against an individual was a deprivation of life, liberty or property was initially resolved by a distinction between “rights” and “privileges.” Process was due if rights were involved, but the state could act as it pleased in relation to privileges. But as modern society developed, it became harder to tell the two apart (ex: whether driver's licenses, government jobs, and welfare enrollment are "rights" or a "privilege." An initial reaction to the increasing dependence of citizens on their government was to look at the seriousness of the impact of government action on an individual, without asking about the nature of the relationship affected. Process was due before the government could take an action that affected a citizen in a grave way.