ERP System Term Paper

Introduction, reasons for recommending an erp system, disadvantages of erp systems, risks associated with erp systems.

An Enterprise Resource Planning, ERP, is a type of system that consolidates all management information and handling flow of data within an organization. It mostly kits a common enterprise data besides application elements to enhance everyday operational of business activities.

For example ERP can play an important aspect in managing finance, accounting, manufacturing, project management, sales, human resource planning, and distribution and so on. The ERP system is composed of three aspects; the information technology, specific business goals and business management practices.

This paper explores the valuable decision that a company can consider in adopting an ERP system. It further discusses some reasons why a company cannot opt for ERP system and identifies the risks the company can be aware of while adopting the system.

Many reasons arise as to why a company may implement an ERP system. It ties together business data and processes that would on the other hand disparage, aiding managers to have comprehensive business acumen. Besides integrating business processes, ERP assist companies in merging processes from all departments within the company and consolidate it in a central database.

This is achieved without incurring more costs and time hence making it easy for accessibility and smooth flow of work. Merging is achieved by building a database repository that allows integration with a variety of application software hence presenting business statistics and other information to various departments within the organization.

To have an ideal ERP system, the system should have an ERP structure which is made up of integrated central database repository in a fused environment

One reason why I would recommend my company to implement an ERP solution is to improve information accuracy and decision making. Modern business has created a competitive environment hence for any similar business to stay relevant it needs to have accurate managed information. According to Cruz-Cunha (2009, p.123), managing company’s future entails accuracy in managing information.

ERP solution is important in strengthening both internal and external information needs of a company. Hence linking information from various sources enhances continues flow of information thus aiding in decision making.

In other words for instance, if a process starts within the manufacturing department and ends at sales department or marketing with stops in-between, an ERP solution can facilitate a smooth transition from the beginning to the end (Cruz-Cunha, 2009, p.102).

Besides, an ERP system functions in real time. This implies that if someone in an accounting department for examples captures certain information in the system, it would immediately be available to anyone who accesses the system. The solution is normally implemented with a comparable feel and look in all departments thus consistency is factored to enhance efficiency in the company.

Secondly, ERP improves the relationship and performance of the company and its suppliers. The quality of raw materials and the ability of dealers to supply on time are important for any successful company. Cruz-Cunha (2009, p116) suggests that, a company has to its select its supplier cautiously and screen their actions to identify any problems before they pose a threat to the company.

To recognize these benefits, companies depend on ERP systems to manage, plan and control the intricate process linked to supplier’s partnerships. The ERP solutions offers dealer procurement and management support apparatus intended to harmonize critical aspects of procurement procedure.

They aid a company to aptly monitor, control, schedule and negotiate procurement costs to ensure superior quality is guaranteed (Cruz-Cunha, 2009, p.125). ERP encompasses supplier management and control processes that aid a company in managing supplier relationships, dealer activities and supplier quality.

Thirdly, ERP increases flexibility of a company. Competition is alive in modern business environments, hence businesses which learn to respond to a customer’s wish besides market changes stays ahead of the game. An ERP system play an important role in aiding companies to accurately forecasts the future and lay strategies to ensure it succeeds.

According to Malaga (2005, p.78), ERP encompasses forecasting tools to such as customer’s preferences sales projections, financial statements and feedbacks besides many tools. A company can rely on these tools to strategically plan and execute new ideas and strategies to remain competitive in business environment. Flexibility will ensure timely formulation of strategy and adjusting to prevailing market condition.

Fourthly, ERP system plays an important role in financial management. The market leaders or the best managed businesses in the world of today have embraced the ERP Financial Solution.

The adoption of an ERP financial solution has in many cases proved to make financial management more efficient. Financial management is a cornerstone is charting organizational success (Malaga, 2005, p.79). An ERP system makes financial management easier and efficient due to a number of factors.

Finance and accounting is, in a sense, about ensuring there are enough checks and controls on how organizational finances flow. ERP functions in a simple way; it has some internally embedded controls in its functions. With internal checks and controls, an ERP solution makes the preparation of accounts and other financial documents easier and fast.

It is very easy to generate account statements at the end of every accounting period. An ERP feature helps most companies to work with ease, because it can support various languages and currencies. Further, ERP systems or solutions are standardized or tailored in a way that it supports international operations; it meets the international accounting and reporting standards (Chorafas, 2001, p.76).

Financial ERP has various features and functions that enable organization achieve its financial management standards. One of the core features of most ERP’s is the Treasury; this is a feature that helps in providing risk management ability.

This facility is important because it enables an organization to know precisely how to manage their cash, and plan a head for financial risk. It also facilitates streamlining and interactions with financial institutions such as bank for matters regarding payment processes (Chorafas, 2001, p.89).

The treasury capability allows ERP applications to interlink endlessly with treasury activities which result in more effective control and management. It leads to integration with the ERP software general ledgers to guarantee adherent to policies and regulatory involvement in reporting financial standards (Glenn, 2008, p.83).

Financial chain management is a feature which is useful in ERP’s and which allows most companies to easily resolve disputes arising from invoices and significantly reduces their collections via electronic billings and other applications. Moreover, Seamless merging within ERP’s allows current information and accuracy reporting of information.

The seamless capability of ERP helps to minimize costs whereas improving net flow of cash in organizations. The feature of financial and management capability is quite beneficial in most organizations because it provide a cornerstone of accounting.

This facility allows accuracy in accounts reporting major large companies with distributed networks (Grant, 2003, p.90). The solution when integrated with general ledger enables achievement of accuracy in balances and reporting

Fifthly, human resource management is better managed by ERP system. Human resource is a valuable asset in a successful business enterprise. Adoption of an ERP system ensures continuous flow of Information related to labor or an organization’s personnel. When such information is received by the HR department it facilitates evaluations.

Human resource related evaluations help organizations in establishing skill and knowledge needs and well as attitude related gaps or issues that have to be addressed. The collection of such information is important for employees as it is instrumentally applied to encourage development of professionalism and improvement of working conditions within the organization.

Human resource managers handle huge loads of information. In big organizations, unless technology is adopted, it is very difficult to keep up to date data on all employees (Grant, 2003, p.68). ERP Solution is a productive management tool which comes in handy to orient and help users to remain focused on their task while focusing direct link with fellow staff (Grant, 2003, p.79).

This tool links personal ability and objectives to the aspirations and goals of the company. Through the use of ERP system, it is easier to facilitate collection and storage of information in a centralized location which allows staff in the human resource departments to center their goal in other strategic planning and personnel development.

Moreover, the operative functions are assumed and tailored automatically hence relieving the department personnel of work load. ERP provides integrated solution to all the different activities and functions in the human resource department.

These activities and functions of the human resource department include; the administration of payroll and manpower related, employee professional growth and development and the general administration in the organization (Grant, 2003, p.111).

Apart from providing the above mentioned services to the organization, the ERP solution provides a platform to enable decision making and analysis so that it can aid in management control reporting. Communication and especially internal communication is paramount in the day to day operations in an organization (Leon, 2007, p.98).

The ERP solution has been tailored to facilitate this function. Services such as opinion polls, news and appointment letters as daily communication examples have been proved efficient for being incorporated in the solution.

On management, the ERP features have tended to vary in regard of employee social benefits. but this social benefits such as vacation and trips and assessment forms have been catered in most ERP’s this simplify the work of Human resource department ( Leon,2007,p.103).

ERP solutions have enabled what is referred to as e-recruitment. The development of e-recruitment practice enabled by development of supporting ERP solutions play an important role in reduction of recruitment related costs for an organization. As the world job market gets complex and more demanding, many organizations have come up with e-recruitment process to enhance tapping the correct talent within and across their borders.

This means finding the right person for the right job. Developing a worthwhile human resource pool and human resource management structures is of great necessity to organizations. It is the human resource pool that drives the organization’s strategic goals or objectives to realization.

E-recruitment facilitates or plays a critical role towards identification of the right kind of employees in the globalized job market. E-recruitment assists the company to manage its recruitments processes more effectively.

One disadvantage associated with an ERP system is Cost. ERP solutions are expensive and complicated to implement and manage. This is the case in larger companies (Bansal, 2009, p.96). Perhaps, established companies have many legacy systems with different configurations thus it demands a great deal of project resources to unravel most of these system methods.

Besides, identifying overlaps, and establishing data feeds into the ERP systems is costly. Installations in larger organizations embraces bespoke solutions thus requiring specialized resources. In such cases, if the company is small or medium sized, the implementation outlay may pose a serious disadvantage. So, before adopting ERP, the company has to asses its capability.

The second disadvantage is the impact it brings on the business process. ERP solutions are dictated by changes in business processes. The changes can sometimes be complex.in order to determine each individual element appropriate in an ERP structure, it is uncertain that specific procedures and policies can remain intact (Bansal, 2009, 114).

Thus the application of ERP solution tends to mirror the architecture of a much broader business change project. These processes tend to be iterative hence when outlining the range of ERP solution at initial stages, most of these deliberations will not come to light.

ERP implementations tend to be viewed as projects that”compel” undesired changes on a company process (Bansal, 2009, p.69). When the ERP implementation is ongoing, often, no substitute is a solution but to alter business processes without starting from zero.

Also lack of adaptability and flexibility is a problem linked to ERP systems. ERP architecture conforms well to established businesses which have distinct procedures and practices. When these processes are aptly on place, ERP system will effectively support them.

However, for companies that are in a process of altering their business processes, ERP tends to be inflexible. This is because, an ERP system has a standardized architecture hence even a small change can cost a lot and complicate its implementation. Hence Companies, constantly exploring changes in line with their business process will not accrue like benefits from the solution because it not conforms to business activities.

Further, matters relating to ongoing support can be a serious setback if not addressed. Most ERP systems are mostly supported by third party dealers. This can lead to issues relating to service level agreements where quality of support and response time is not in tandem with company requirements (Bansal, 2009, p. 79).

Support and licensing fees can also surge the cost of the solution.Moreover, security of information stored in the ERP can be a major concern incase third party dealers are the custodian, thus many companies utilizing ERP are always at the sympathy of dealers with no adequate control over information and availability of the system.

Lastly, the ERP system erodes with the type of business. Efficiency of an ERP depends on the type of business and processes to be executed to aid and sustain the architecture. According to Bansal (2009, p.79), companies that have less investment in efficient training of their employees for instance, will not feel the results of ERP implementation.

Where companies work in a tight environment, the system will tend to give little results. The ERP architecture is anchored on an integrated business environment and limitation in sharing of information within departments will hinder efficient working thus creating more risk to a business.

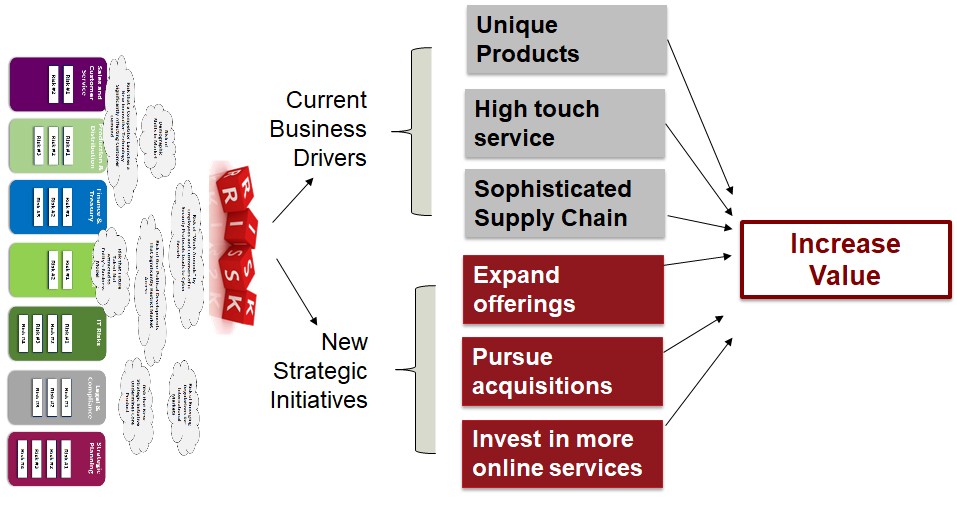

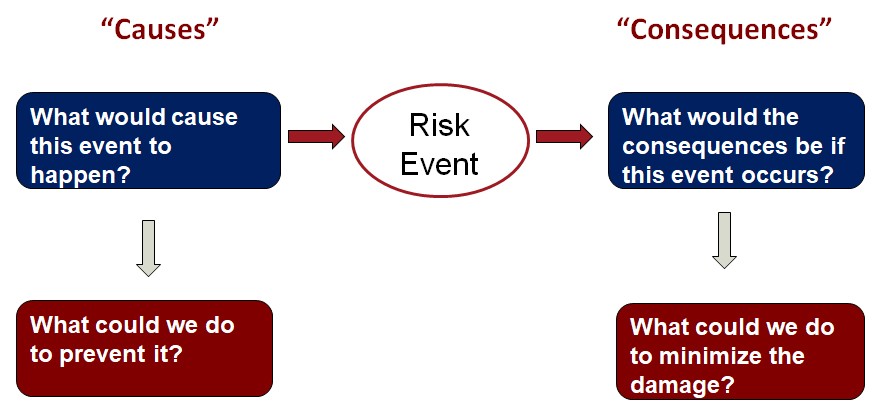

Without proper risks identification in selecting an ERP system, a lot of time, resources and knowledge can be wasted. Early risk identification ensures that success is achieved when a company is making a choice of implementing an ERP, because this incorporates of having a quality system in an organization (Grant, 2003, p.39).

The risk associated with the Implementation of the ERP systems includes the complexity of an application, lack of end user experience and lack of clear job definition of members handling the project. For any systems to successfully be utilized in an acompany, good end user support is important, lack of support poses a huge risk in implementing the ERP project in an organization (Grant, 2003, p.46).

Without proper job roles and specification, the project team can pose a serious risk in implementing the ERP project. The Project should be able to grasp and understand a complex technological problem regarding the application (Grant, 2003, p.56). This makes it better to relay and give clear support to the end user of the application. This eliminates risks and enhances proper implementation.

Lack of proper coordination between the company structure, strategy and processes and the choice of the ERP solutions also pose a severe risk. ERP alone cannot really improve the performance of the businesses (Harwood, 2003, p. 57).

Companies or organization should reduce the risks by restructuring its operational processes and the implementation should be seen as a business initiative. Unless an organization fails to strategize its implementation goals, this risk can make it harder for quality implementation (Harwood, 2003, p.77).

Loss of Project control is also a major risk in an ERP project implementation. ERP project loses control in two major ways which includes; lack of control over the project team members and failure to control the employees when the system is implemented and in operational (Jutras, 2003, p. 58).

This failure or lack or coordination leads to decentralization of decisions which develops into unproductive authorization of decisions. To ensure effective decision making and enabling proper ERP implementation, the collocation of information about ERP implementation, the company should set up a project implementation team.

The team should be conversant and have relevant information and knowledge about ERP system implementation (Jutras, 2003, p.79). The team should have knowledge of information Technology or change management skills. Decision making should be conferred to the team by the management

ERP also pose risk, Operational ERP solution results in responsibility of devolution and empowerment of lower or middle level employees. If no proper controls are instituted, either within the ERP or in the process that organization deems best, then there will be a potential risk (Jutras, 2003, p.87).

Complexity of the project also poses a major risk in ERP project implementation. ERP systems involve the use of large expenditures which encompasses software, hardware, consultation, implementation costs and training. This always takes more time to be completed (Leon, 2007, p.68).

ERP projects have been known to take longer time than other ordinary Information system management. The complexity of this ERP cause change of roles in the company and this pose a business risk in an organization

Lack of important in house skills in an organization also creates a risk in implementing an ERP system (Leon, 2007, p.98). This has been attributed to lack of skills by the project team which is associated with program development risk.

ERP development and deployment requires a variety of skills which encompasses, risk management, change management, technical knowledge in implementation among other factors. Most organization lacks knowledge on change management needed for ERP implementation (Myerson, 2001, p.68).

Furthermore, ERP is build using a programming concepts, this is sometimes new to existing IT personnel in an organization. Thus, lack of house skills regarding the ERP systems creates a possible business risk (Myerson, 2001, p.68).

The ERP is designed to provide much needed facility within and geographically dispersed businesses across a multi platform with its functional units.

This has been viewed as important to support itinerant management executives to have much needed details to support their decision making at the management level. For effective choice of an ERP system, a company as to efficiently explore its usefulness, demerits and risks factors to have a clear understanding.

Bansal, S., 2009, Technology Scorecards: Aligning IT Investments with Business Performance, John Wiley and Sons, New Jersey, NJ

Chorafas, D., N., 2004, Integrating ERP, CRM, supply chain management, and smart material, CRC Press, Boca Roda, FL

Cruz-Cunha, M., M., 2009, Enterprise Information Systems for Business Integration in SMEs: Technological, Organizational, and Social Dimension, Idea Group Inc (IGI), New York, NY,

Glenn, G., 2008, Enterprise Resource Planning 100 Success Secrets – 100 Most Asked Questions: The Missing ERP Software, Systems, Solutions, Applications and Implementation, Lulu.com, North Carolina

Grant, G., G., 2003, ERP & Data Warehousing in Organizations: Issues and Challenges, Group Inc (IGI), New Jersey, NJ

Harwood, S., 2003, ERP: The Implementation Cycle, Butterworth-Heinemann, Amsterdam

Jutras, C., M., 2003, ERP Optimization: Using your Existing System to Support Profitable E-business Initiatives , CRC Press, Boca Raton

Leon, A., 2007, Enterprise Resource Planning, Tata McGraw-Hill, New York, NY

Malaga, R., A., 2005, Information Systems Technology, Pearson Prentice Hall, London Myerson, J., M., 2001, Enterprise Systems Integration , CRC Press, Boca Raton

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2019, December 15). ERP System. https://ivypanda.com/essays/erp-system-term-paper/

"ERP System." IvyPanda , 15 Dec. 2019, ivypanda.com/essays/erp-system-term-paper/.

IvyPanda . (2019) 'ERP System'. 15 December.

IvyPanda . 2019. "ERP System." December 15, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/erp-system-term-paper/.

1. IvyPanda . "ERP System." December 15, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/erp-system-term-paper/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "ERP System." December 15, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/erp-system-term-paper/.

- Implementing ERP in an Organization

- Evolution of ERP system

- ERP Solution and Cloud Computing

- Sage ERP Software System Pros and Cons

- ERP Issue: Stakeholders

- Levi Strauss & Co. and the ERP Failure

- Change Management, BPR and successful ERP implementation

- Implementation of ERP Systems in Sharjah Airport

- ERP Technology Effect on Hansen’s Production

- Enterprise Resource Planning Benefits and Risks

- Health Information Management System: Sohar Hospital

- Difference in Public and Private Sector Management

- Talent on Demand: Facilitating Talent Development

- Running Head: Organizational Behavior

- Employment Relations in Modern Australian Work Place

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Why enterprise resource planning initiatives do succeed in the long run: A case-based causal network

Pierluigi zerbino.

Department of Energy, Systems, Territory and Construction Engineering, University of Pisa, Largo Lucio Lazzarino, Pisa, Italy

Davide Aloini

Riccardo dulmin, valeria mininno, associated data.

The minimal data set underlying the results described in the paper can be found in the paper and in the Supporting Information file.

Despite remarkable academic efforts, why Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) post-implementation success occurs still remains elusive. A reason for this shortage may be the insufficient addressing of an ERP-specific interior boundary condition, i . e ., the multi-stakeholder perspective, in explaining this phenomenon. This issue may entail a gap between how ERP success is supposed to occur and how ERP success may actually occur, leading to theoretical inconsistency when investigating its causal roots. Through a case-based, inductive approach, this manuscript presents an ERP success causal network that embeds the overlooked boundary condition and offers a theoretical explanation of why the most relevant observed causal relationships may occur. The results provide a deeper understanding of the ERP success causal mechanisms and informative managerial suggestions to steer ERP initiatives towards long-haul success.

1 Introduction

Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, the global Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) market is experiencing a prosperous trend in 2021 [ 1 ]. In 2020, SAP, the ERP market leader, has registered a greater increase in turnover than expected [ 2 ] by harnessing the Cloud technologies [ 3 ]. During the last five years, ERP systems have been building new momentum on the wave of topical streams, such as postmodern ERP [ 4 ], Big Data [ 5 ], Internet of Things [ 6 ], Process Mining [ 7 ].

Notwithstanding this, ERP failure rates are notoriously high [ 8 ], ranging from 40% to 90% according to different failure meanings [ 9 , 10 ]. The costs associated with a failure an ERP initiative may put the whole organisation at stake [ 11 ]. In 2016, Gartner [ 12 ] estimated that the lack of capabilities to fulfil future postmodern ERP strategies may give rise to a widespread failure on the ERP cloud initiatives. The contrast between growing investments and high failure rates characterises the ERP conundrum: in spite of a wealth of research regarding ERP success, the scientific literature is still lacking a thorough comprehension of why ERP initiatives succeed. This brainteaser may be rooted in two reasons.

First, the ERP scientific literature has spent remarkable efforts on figuring out what ERP success is, i . e ., which constructs may define it, and how it may occur, i . e ., which patterns may link the constructs to each other, but has mostly neglected why the proposed relationships may be observed [ 13 ]. The little focus on why a phenomenon is expected to occur points out the lack of causal explanations for such a phenomenon [ 14 , 15 ]. In investigating a phenomenon and its implications, exploring what and how has mainly descriptive purposes tied to an empirically driven perspective [ 16 ]. Delving into the why may enrich this valuable approach with theoretically driven explanations of the phenomenon. Conversely, the lack of why limits the understanding of a phenomenon [ 16 ] and the development of conceptually rigorous insights into it [ 17 – 19 ].

Second, in attempting to define and explain ERP success, the scientific literature has rarely considered its multi-stakeholder nature. This multi-stakeholder perspective may embody an interior boundary condition under which success occurs. Overlooking it may widen the gap between the theoretical models that define and explain the phenomenon under study–ERP success, in our case–and the empirical phenomenon itself [ 20 ]. Exploring the why of a phenomenon on the basis of theoretical models that might not adequately fit the reality may lead to theoretical inconsistency, hindering knowledge cumulativeness in the corresponding research stream [ 21 ].

To tackle these issues, this paper aims at answering the following research question:

" Why does ERP success occur ?"

In doing so, we refer to success in the long run, which is conceived in the ERP post-implementation phase called "onward/upward" by [ 22 ]. This phase begins after overcoming the performance dip that typically occurs during the shakedown phase and is associated with the potential achievement of most ERP benefits [ 22 ]. It is mainly at this stage that it is possible to effectively assess whether the attained results have lived up to the expectations. Thus, success notions such as implementation and project success are outside the scope of this work because the success of an Information System (IS) is " not intended to understand implementation or project success ", which may be better studied by change and project management theories [ 23 , p. 504]. We used the ERP life cycle by [ 22 ] as a theoretical reference for the development of this paper.

To answer the research question, we developed a multiple case study based on the theory-building guidelines by [ 24 ]. From a managerial standpoint, to achieve our research objective may help decision makers in planning more accurate strategies for attaining the post-implementation benefits and in better addressing the use of resources during the ERP initiative.

The findings contribute to the ERP success scientific stream by showing that the continuous flow of ERP benefits may be achieved by the synergistic actions of three causes: the degree to which the ERP specifications are fulfilled over time; the user-system interaction, conceptualised as a cognition that diverges from frequency-oriented evaluations; and the continuous compliance between the attained benefits flow and the stakeholders’ expectations. This contrasts the predominant behavioural conceptualisation of system use and emphasises the role of the expectations and the longitudinal assessment of the system and information quality in attaining ERP success.

The remainder of this work is structured as follows: Section 2 provides a theoretical background; Section 3 expounds the research design; Section 4 illustrates the case findings; Section 5 discusses the results; Section 6 concludes the manuscript.

2 Theoretical background

This section reviews ERP post-implementation success to better highlight the research gap (2.1) and structures a theoretical framework for leading the development of this work (2.2).

2.1 ERP post-implementation success

ERP systems are commercial software packages that automate and integrate firm’s business processes [ 25 ]. Their implementation enables and often drives a business process reengineering based on best practices embedded in the software [ 26 ]. ERP systems are part of the Enterprise Systems [ 27 ], i . e ., extensive organisation-wide applications including components such as ERP, Customer Relationship Management, Supply Chain Management, Product Lifecycle Management, Advanced Planning and Scheduling, Manufacturing Execution Systems, Business Intelligence and Data Analytics.

ERP systems are characterised by high integration– i . e ., their parts are tightly amalgamated–and complexity– i . e ., the relationships among their parts are numerous, nested, and interdependent [ 28 ]. Higher levels of integration and complexity usually correspond to a wider scope of the ERP initiative [ 28 ], which may thus gather interest and expectations from an increased number of stakeholders. This is a major reason why ERP success should be conceptualised from a multi-stakeholder standpoint [ 29 – 31 ], and not only from the perspective of the adopting firm and/or the end users. Example of additional stakeholders may be customers, suppliers, project leaders, key users, shareholders, vendors.

By drawing on [ 32 ], we define ERP post-implementation success as the effective exploitation of the ERP system and of the information it generates to achieve the intended benefits flow over time from the perspective of all the pertinent stakeholders. This excludes the technical installation success and all the related indicators ( e . g ., cost overruns, time estimates, project management metrics). Henceforth, for the sake of brevity, we use "ERP success" rather than "ERP post-implementation success". We make the following distinction regarding the benefits:

- Immediate benefits: benefits associated with the early effects of ERP-enabled business practices adoption and of modifications to the system and/or the information it generates. They directly affect profitability and are operational, e . g ., reduction of labour, inventory, and quality costs.

- Future benefits: benefits associated with the mid- and long-term effective consolidation of the ERP-enabled business practices adoption and of modifications to the system and/or the information it generates. They include most of the benefits that indirectly affect profitability, such as managerial benefits ( e . g ., improved decision making), strategic benefits ( e . g ., support to growth plans), organisational benefits ( e . g ., facilitated organisational learning), and potential benefits ( e . g ., future ERP-enabled investment opportunities).

Table 1 reviews how the scientific literature has conceived and operationalised ERP post-implementation success. The papers were identified through a systematic review we conducted on Scopus using the following search string: ("ERP" OR "Enterprise Resource Planning" OR "Enterprise Systems" OR "Organisational-wide information system") AND (success OR benefits OR impacts). The query was restricted to journal papers. To grant comprehensiveness of the review, no restrictions on the year or type of publication were applied. Furthermore, the review was enriched by applying the snowballing method.

The review we conducted highlights two evidences. First, surprisingly, only [ 53 ] probed why ERP success may occur. Despite the undoubted merit of their work, the ERP success definition they adopted coincides with ERP business benefits from the perspective of the implementing firm only. This overlooks the multi-stakeholder nature of ERP success. Moreover, their definition of post-implementation combines the shakedown and onward/upward phases. This may be debatable because, in these two phases, the conceptualisation of the success notion is deeply different [ 57 ].

Second, ERP success has been defined and described by drawing from the Information System (IS) success field. This was carried out in two ways. In the first one, the ERP literature used a single construct ( e . g ., User Satisfaction or Organisational Benefits) as a proxy for ERP success. This may be questionable because it is strongly subjective [ 72 ] and may lead to contrasting results [ 23 ]. In the second one, the ERP literature has borrowed and re-specified success models from the IS environment to the ERP one. Most papers equal ERP success to IS success explained through the IS success models by DeLone and McLean [ 39 , 59 ]. In particular, they generally leverage the quality of the information system, the quality of the information generated by the system, and the benefits or impacts yielded by the system to explain the success of the ERP. However, to the best of our knowledge, the ERP success literature has not adequately taken into account the multi-stakeholder perspective, despite its relevance to the topic. This finding may be worrying. Indeed, from a theory building perspective, the multi-stakeholder perspective is an interior boundary condition that may better specify the domain of a theoretical model, enhancing its adherence to the empirical system [ 20 ].

Therefore, the reason(s) why ERP post-implementation success occurs is still an open research question. A prominent reason for this may be that an ERP-specific interior boundary condition ( i . e ., the multi-stakeholder perspective) has often been discussed but not sufficiently considered in investigating the causal mechanisms conducive to ERP post-implementation success.

Thus, the next section sets a theoretical framework for investigating the reason(s) why ERP success may occur.

2.2 Theoretical framework

The awareness of commonalities and differences between IS failure and success has been effectively exploited for investigating the success of specific ISs, e . g ., monitoring systems [ 73 ]. In particular, while recognising the causal asymmetry between IS success and failure, [ 73 ] set the simplifying hypothesis that " the negated concept , ie , the lack of success , is the same thing as the opposite concept , ie , failure " (p. 404). Indeed, to a certain extent, IS failure and success are linked to each other [ 74 ].

Although IS success and failure are two sides of the same coin, they are not totally specular because the relationships among variables describing IS phenomena do not necessarily assume causal symmetry [ 75 ]. IS failure may propagate in a domino effect [ 76 ], while success does not. " With the benefit of hindsight one can usually reconstruct a systematic pattern of events that led to the failure " [ 76 , p. 284], while this is not true for success. Moreover, failure and success antecedents are not necessarily opposites [ 77 ]. Despite these differences, " there can be multiple , equally effective pathways to IS success " [ 73 , p. 385], and this equifinality is valid for the IS failure too [ 76 ].

Lyytinen and Hirschheim [ 76 ] presented one of the most complete and spread empirical taxonomies of IS failure, consisting of four failure types:

- Process failure . It refers to two aspects of inadequate project management performance in developing an IS. First, the IS development process cannot create a workable system because of severe issues in the design, implementation, or configuration phases. Second, more frequently, the IS development process oversteps budget and/or time constraints.

- Correspondence failure . The IS design objectives expressed by the management are not met. It represents the management’s perspective of IS failure.

- Interaction failure . The users do not use the IS as intended or reject it because of their negative attitude towards it.

- Expectation failure . An IS may attract the attention of several stakeholders. This attention consists of expectations on how the IS will serve the stakeholders’ interest. Expectation failure occurs when the IS fails to meet a stakeholder group’s expectations. Thus, while Correspondence failure regards the system requirements expressed from the internal management perspective only, Expectation failure potentially voices the expectations of all the other stakeholders.

This IS failure taxonomy leverages four IS domains (Project, Correspondence, Interaction, Expectation) to classify several failures reported in the IS literature. The concepts underlying such domains are rather general: Project relates to time and/or budget; Correspondence to design objectives/specifications; Interaction to IS use/acceptance; Expectation to stakeholder group’s expectations. It is our contention that the four IS domain may be harnessed in a success context too. Indeed, the definition of the most prominent IS success constructs may be associated with the main concepts underlying such domains ( Fig 1 ). We excluded the Process domain because if refers to a project management standpoint that is out of the scope of this manuscript. To identify the most prominent IS success constructs in Fig 1 , we conducted a systematic literature on the IS success topic. Further detail on the protocol and the results of this review are provided in the Supporting Information file.

Hence, we argue that the Correspondence, Interaction, and Expectation domains may be framed as logical clusters according to which explain ERP success and collect the related evidences to answer our research question. A similar approach was adopted by [ 29 ], who used the four IS domains as a theoretical reference to define four ERP success categories and to integrate them into an ERP Critical Success Factors taxonomy. Thereby, the three selected domains are not intended to have any descriptive or explanatory power per se. Instead, their role is to offer a theoretical reference for steering the collection and arrangement of the evidences to pursue our inquiry.

3 Research design

To pursue our research objective, we adopted the case study methodology for theory building. Case research is always proper in IS research and appropriate at any stage of knowledge about a phenomenon, particularly when capturing the context of the phenomenon is of utmost importance [ 78 ]. We chose the inductive, positivist, case-based roadmap for theory building by [ 24 ] because of two reasons. First, the positivist epistemological approach aims at identifying the individual components of a phenomenon and at explaining them [ 78 ]. Second, inductive methods strongly relate to the development of explanations [ 79 ].

This section expounds the methodological choices underpinning the multiple case study. To facilitate its understandability, it was structured in three parts in line with the case research framework by [ 80 , p. 172]: case selection (3.1), data collection (3.2), and data analysis (3.3).

3.1 Case selection

To define the case population, we considered only firms that completed the project phase. To exclude excessively small cases, we chose manufacturing firms with at least 250 system users and that challenged the same ERP implementation category [ cf . 81 ]. We excluded the Vanilla implementations because of their small number of prospective users and limited scope and budget [ 81 ].

By following a geographical proximity criterion within the defined population, we selected four European cases, the unit of analysis of which was the whole ERP initiative. The number of cases provided sufficient analytical power [ 24 ]. To achieve both the theoretical replication and the literal replication, we investigated two cases in which the ERP initiative was in the advanced onward/upward phase and two cases in which it was at the very beginning of this phase. As regards the latter cases, our investigation proceeded until over two years after returning to "normal operations". Indeed, while success is mostly conceived within the advanced onward/upward phase, some operational concerns are strongly linked to the early period of this phase [ 30 , 31 ].

Company A is a worldwide Swedish–Swiss multinational corporation that operates in the field of automation and power. The plant in which we carried out the case study experienced an Oracle roll-out after being acquired by Company A.

Company B is an engineering and systems technologies international company that decided to replace its legacy system with a Microsoft Dynamics NAV ERP. Company B top managers were initially reluctant to adopt the ERP because wanted to retain the flexibility of their old system. Yet, they changed their mind because their existing ICT infrastructure was Microsoft-based.

Company C is an iron and steel international company that implemented an Infor ERP. After initial indecision, the top managers advocated the replacement of the old legacy system because it was not able to support their business anymore due to the lack of required functionalities.

Company D is an Italian national leader in manufacturing and installing cargo systems for liquified gas carriers. Its extant legacy system was not able to back up the firm’s growth and was replaced by a JD Edwards ERP solution.

Table 2 summarises the main characteristics of the ERP implementations.

3.2 Data collection

We developed a case study protocol according to [ 82 ]. Each case started with a kick-off meeting with the Project Sponsor, the Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Manager, and the Project Manager of the ERP initiative–if different from the ICT manager. During the kick-off meeting, commitment to the research project was guaranteed, visits were arranged, and the data collection methods were discussed and approved. Fig 2 summarises the data collection process, which started in April 2015 and ended in October 2020.

The data collection methods we relied on are:

Personal notes by the investigators regarding the on-going development of the case and the links with other cases were recorded in field notes [ 78 ].

- Participant observation [ 82 , 84 ]. We employed the participant observation method for observing the end users interacting with the ERP system in their daily routine, according to the guidelines by [ 85 ]. For each functional area in each case, the corresponding manager suggested two end users to observe, and the observation was performed until saturation.

- Archival records [ 82 ]. For each case, we analysed the main project documents. In addition, as suggested by [ 83 ], we probed quantitative data on the ERP initiatives, particularly about the size of the ERP system, scope, and budget.

3.3 Data analysis

The data analysis ( Fig 4 ) was arranged in a two-stage way: within-case analysis (Steps 1–4) to develop a set of causal explanations for figuring out the mechanisms that led to ERP success; and cross-case analysis (Step 5) to cross the results from the within-case analyses for trying to generalise the findings.

The data analysis steps in Fig 4 are detailed in the following:

- Step 1 : developing interim case summaries . Drawing from the case archives, an interim case summary [ 86 ] was developed to synthesise and review the case data and findings.

- Step 1/bis : inter-functional analysis . For each case, we compared the evidences stemmed from the different business functions by contrast tables [ 86 ] for obtaining an inter-functional overview concerning the success topic across the three logical clusters ( i . e ., Correspondence, Interaction, Expectation).

- Step 2 : holistic coding . The purpose of the holistic coding step [ 86 ] was to elicit the Conceptual Units from the case evidences. A Conceptual Unit is the main concept expressed by a unit of case data and appropriately labelled. Table A1 in Appendix A in the S1 File reports some examples of holistic coding. The outcomes from this step were jointly discussed among the authors to reach consensus regarding the sixty-one identified Conceptual Units.

- Step 3 : causation coding . We formalised the causal sequences, called Causal Chains (CCs), among the sixty-one Conceptual Units by causation coding [ 86 ]. A CC is a plausible, causal link between two or more Conceptual Units. Appendix B in the S1 File contains Table B1, which displays an example of the CCs we developed from case B, and Figure B1, which graphically illustrates how they may be used. Appendix B in S1 File also includes further details on how Conceptual Units form CCs.

- Step 4 : developing within-case causal networks . By combining all the CCs from the four cases and the three logical clusters, we developed twelve within-case causal networks. A within-case causal network is a graphical representation of multiple CCs and its purpose is to group and illustrate the causal relationships stemmed from the cases.

- Step 5 : pairwise comparison . The within-case causal networks were pairwise compared to assess their similarities and differences and to synthesise them into three cross-case causal networks (one for each logical cluster).

- Step 6 : formalisation . By combining the three cross-case causal networks, reported in the Supporting Information file, we developed the overall ERP success causal network. Furthermore, we discussed how the resulting network embedded the multi-stakeholder boundary condition, why the main causal relationships were observed, and the theoretical and managerial implications.

This section briefly reports the results from the within-case analysis (4.1) and illustrates the results from the cross-case one (4.2).

4.1 Within-case analysis results

The four manufacturing firms are characterised by different approaches and challenged the ERP implementation for different reasons. Despite some operational issues, all of them overcame the shakedown phase and are currently benefiting from their new system. Table 4 describes the company cases.

The four ERP initiatives are judged as successful according the respondents. Although the point in time in which some benefits were perceived has been different than expected, the overall benefits flow has been satisfying.

For the sake of brevity, we did not include the within-case causal networks because they are an intermediate result that is included within the cross-case analysis. Despite the differences among the cases, no idiosyncratic Conceptual Units or CCs were found.

4.2 Cross-case analysis results

The overall ERP success causal network in Fig 5 contains a wealth of information on plausible causal mechanisms leading to ERP success. For the sake of brevity, this section focuses on the most relevant findings concerning the role of the Correspondence (4.2.1), Interaction (4.2.2), and Expectation (4.2.3) Conceptual Units in explaining ERP success.

4.2.1 Correspondence cluster

The realisation of a proficiently usable ERP is strongly driven by the satisfactory implementation of the specifications, which regard the system, the needed input, and the desired output and which emerge from the as-is and to-be analysis of the business processes. Thus, the specification implementation, review, and test cycles are the core concepts in the Correspondence cluster.

The ERP specifications should not be considered as indisputable data over time because they may be reasonable only in the specific point in time which they were approved in, based on the information available in that moment. Some of them may be successfully tested and be still valid in the shakedown phase, as occurred in case D. They may be successfully tested, but changed later in the shakedown phase because of operational issues, as highlighted by a Key User from the manufacturing function in Case C:

" We need to push the materials into production by the system as fast as possible because our production peak occurs in the summer […]. They [the functional managers] satisfied our requests . Two months later , during the summer , [name retained for privacy] started yelling with the keyboard in his hands because the system was still too slow ."

Moreover, some specifications may be successfully tested and still valid in the shakedown phase, but partly inadequate in the onward/upward phase–as stemmed from case A. The reasons for this latter occurrence are the unlikelihood to conduct the functional and non-functional tests in a complete way in all the possible scenarios and the difficulty in evaluating some specifications until after utilising the ERP massively.

Furthermore, some specifications may change over time during the onward/upward phase for responding to market needs, e . g ., in case A, the company switched from standard management practices to lean production ones. Notably, the CIO from case B stated that:

" The most important aspect is that the ERP includes the requested functionalities . The potential mistakes should not be linked to a wrong implementation but to a right implementation of specifications that , later , may turn out to be partly unsatisfactory and be modified/updated ".

More importantly, the fulfilment of the specifications over time is key to attain a benefits flow, as shown by some relevant case quotations in Table 5 .

Interestingly, the quotations in Table 5 show that the relationship between fulfilling the ERP requirements and achieving the benefits flow develops over time. During this time, the users may experience usage of the ERP and of its information, as suggested by the link between the Correspondence and the Interaction clusters in Fig 5 . While this aspect is more evident in the following section, we argue that:

The system and information specifications may not be static over time even during the onward-upward phase and may causally affect the ERP benefits flow indirectly through the Interaction Conceptual Units.

4.2.2 Interaction cluster

The user-system interaction may highlight the need to revise the implemented specifications to improve the usability of the ERP and of its information. This may occur during the shakedown phase, but also during the onward/upward phase after utilising the ERP for a while. In case A, the users of the logistics and finance functions experienced mediocre usability, despite appropriate vendor and package selection and the complete fulfilment of the specifications. The interaction was described as "intricate" to the extent that, after almost one year of the onward/upward phase, the Logistics Manager required additional human resources for managing the same activities:

" After almost one year , […] four new employees were needed to perform our activities because this devilish system was muddled and not convincing ."

Interestingly, this opinion was quite the opposite during the test phases. Moreover, additional issues in the sourcing functionalities emerged later fortuitously, only when the sourcing users had to revise some sub-sourcing activities.

In case A, the usability was also negatively affected by the excessive number of unused functionalities. Most of them were specifically requested and/or customised, since they were considered as " absolutely necessary to our daily routine " by the key users and the process owners. Notwithstanding this, one year and half after the go-live, 30% of the overall functionalities were removed because they were not actually used, burdening the windows and the Graphical User Interface, entailing relevant albeit superfluous maintenance costs, and garbling the maintenance of other functionalities.

In line with this, several respondents from cases B and D, particularly those from the accounting and finance functions, underlined that an ERP system has its own life cycle and it is not advisable to squander it by poor usability and suboptimal configurations. In addition, the Chief Commercial Officer from case C stated that:

" One may use an ERP that works as planned , but if s/he does so without smooth and serene utilisation , this may lead to abandon the system in the long run ".

ERP updates or modifications usually require users time to adapt by additional specific training and education activities. These activities make users more confident while using the ERP, and the more their use is acknowledged as correct, the more they build improved awareness and knowledge. In particular, the awareness concerns how the system works, how its information output is yielded, how to interpret the data, and which are the effects that user’s action exert on the business processes. The knowledge regards the link between the purpose ( e . g ., performing a task) for using the system and its information, on one hand, and the commands and functionalities for achieving this purpose, on the other hand.

These higher awareness and knowledge gratify the user and generate an enhanced interaction–an advanced form of interaction that is not meant as simply mechanical. In case B, the achievement of the advanced interaction required almost two years over the end of the shakedown phase. On one side, it entailed users realising the ERP-enabled improvements in their daily operations. On the other side, it allowed them to detect a mistake in the elaboration of an index for the production order management. In case A, under the same circumstances, the users discovered a function for solving misalignments between purchase orders and work orders. In case C, two users found a licit shortcut in the ERP for avoiding using a bugged functionality. Interestingly, the vendor-side Project Manager in case D stated that:

" The interaction with the ERP must be appropriate , where appropriate means to use the system in a way to avoid not to use the system . It is necessary to understand how the data steer the execution of the processes […] or the processes may fail even if the ERP works fine ".

Fig 5 exhibits a causal effect of this enhanced interaction on the ERP benefits flow. As shown by some case quotations in Table 6 , this effect is stronger when the above-mentioned awareness and knowledge are higher or, in other words, when the interaction is further enhanced.

Accordingly, we contend that:

User-system interaction, when developed by building awareness about using the system and its information and knowledge concerning the purpose for using the ERP, may cause the achievement of ERP post-implementation benefits.

4.2.3 Expectation cluster

The case evidences pointed out the usefulness of distinguishing between direct and indirect stakeholders. Direct stakeholders are those who directly interact with the ERP, i . e . the users. They may include end end/key users, process owners, members of the project team, but also external actors, e . g . partner suppliers that may be allowed to use some ERP functionalities for checking a stock level (cases A and B) or for loading a Bill of Materials (case D). For instance, an external Key User from a partner supplier in case A reported that:

"[Firm A] procures our engines since years . […] I pushed for including a functionality in their system to grant us visibility of their engine stock levels . We did not want to disappoint each other ."

Another example of external actors is a partner customer that may exploit other functionalities to intervene in the product design (case B) or to check the reserved stocks (cases A and C).

Indirect stakeholders are actors who have expectations towards the ERP initiative, but that do not interact with the system. Indirect stakeholders should be informed of the status of the ERP initiative, or they would experience the consequences of the implementation without figuring out whether their expectations were not met. Table 7 contains some examples of indirect stakeholders suggested by the case informants.

Both direct and indirect stakeholders have expectations towards the ERP initiative, which are summarised by the Aiming at business continuity and onward/upward performance Conceptual Unit. They type of performance to improve depends on the expectations that each stakeholder sets for the ERP initiative. Nonetheless, such expectations exert different effects on the ERP benefits flow. Direct stakeholders’ expectations cause ERP benefits indirectly by the translation of these expectations into requirements to fulfil, which eventually lead to Enhanced interaction through the Correspondence and Interaction CCs ( Fig 5 ). Instead, indirect stakeholders’ expectations showed a mutual causal relationship with the ERP benefits flow. This seems to be rather trivial, since having an expectation is not enough to achieve a benefit by itself. Although this unexpected finding is discussed in the next section, we can state that:

Direct stakeholders’ expectations may indirectly cause ERP benefits by the enhanced interaction between the users and a proficiently usable ERP if these stakeholders are actively involved in the elicitation of the requirements.

Indirect stakeholders’ expectations and the flow of ERP benefits may causally affect each other.

It is worth underlying that we assume that all the expectations are realistic. This is a basic assumption hypothesising that the change management activities conducted during the implementation project phase have been successful. Basic assumptions may not be perfectly true, but provide leverage in understanding the phenomenon under investigation. As underlined by Burton-Jones & Grange (2013, p. 634), making basic assumptions is typical in building theoretical concepts also in other fields, e.g.: in Economics, assuming that humans are rational.

5. Discussion

This section argues why ERP success may occur (5.1) and discusses the scientific and managerial implications (5.2).

5.1 Why ERP success may occur in the long run

The analysis of the causal network in Fig 5 revealed that ERP success may be mainly caused by three conjoint mechanisms: first, the causal action of direct stakeholders’ expectations on Enhanced interaction through ERP proficient usability ; second, the causal effect of Enhanced interaction on ERP benefits flow ; third, the mutual relationship between the indirect stakeholders’ expectations and ERP benefits flow .

As concerns the first causal mechanism, its explanation may be supported by the Expectation-Confirmation Theory (ECT). ECT posits that the match between the expectation towards a product or service prior to purchase and the performance perceived when using that product or service leads to post-purchase satisfaction, which in turn forms a repurchase intention [ 87 ]. Within the IS scope, ECT suggests that IS continuance is mainly explained by satisfaction with prior IS use, which stems from the consistency between the expectations over the IS and the perceptions after using the IS [ 88 ]. As pointed out by the ERP causal network, to satisfy direct stakeholders’ expectations means that the definition, review, and test cycles of the implemented specifications have fulfilled the established requirements. The initial interaction with the ERP developed in this way may entail further revising the specifications, which improves the proficient usability of the ERP. This increases the consistency between the expectations that direct stakeholders have towards the ERP and their judgement on the ERP. According to ECT, such a consistency makes users satisfied and more likely to continue using the ERP [ cf . 89 ]. As showed by our findings, the prolonged interaction between a proficiently usable ERP and trained and satisfied users allows users to make cognitive progresses regarding ERP-related awareness and knowledge while performing a task. In doing so, users master the ERP and become further gratified and satisfied. This higher, aware, and knowledgeable satisfaction over time generates the enhanced interaction and users’ willingness to use the ERP at their best.

The second causal mechanism requires explaining why Enhanced interaction may cause ERP benefits flow . This mechanism may be explained by the Theory of Effective Use (TEU) by [ 90 ]. TEU posits that the IS use founded on the task-user-system interdependence is a necessary and sufficient condition for attaining performance improvements. Analogously, the Enhanced interaction Conceptual Unit is meant as an interaction involving interdependence among system and information characteristics, task characteristics, and user skills and capabilities. In particular, Fig 5 displays that it is generated by a set of CCs that consider the proficient usability of the ERP system and information, user capabilities in the interaction with the ERP, and the user-task link while using the ERP for one or more purposes. Furthermore, TEU claims that, given a task and a system, the use value may vary according to the user’s capabilities, leading to variations in achieving benefits. This is consistent with the findings reported in Table 6 , which stress that a more aware and knowledgeable use causally leads to more benefits. Therefore, the CCs generating the enhanced interaction Conceptual Unit and the rationale underpinning Effective Use notion are consistent with each other. This analogy may thus explain the interaction-caused ERP benefits flow we observed.

The third causal mechanism accounts for the causal effect of the indirect stakeholders’ expectations on the ERP benefits flow. Admittedly, it is unlikely that having expectations over ERP benefits may be a necessary and sufficient condition to attain them. This direct action is attributable to the enhanced interaction. Instead, indirect stakeholders’ expectations strengthen the commitment and the economic support towards the ERP: although this does not cause any benefit, it grants continuity of the ERP initiative. Thus, the synergistic action of such expectations and of the enhanced interaction may cause the achievement of progressive ERP benefits distributed over time, i . e ., the attainment of a distributed flow of ERP benefits.

In addition, attaining ERP benefits may cause a positive effect on future direct and indirect stakeholders’ expectations because it highlights that the outcomes from the ERP initiative are satisfactory. The stakeholders become more certain about the usefulness of the ERP and more inclined to use and support it over time. In this regard, ECT overlooks that consumer’s expectations towards a product or a service often changes following the consumption experience [ 88 ]. In our case, the achievement of an ERP benefit is advantageous for one or more stakeholders, which directly experience the positive impacts of the ERP implementation. Consequently, their realistic expectations of future benefits become more optimistic because their cognitive processes set a new positive reference to guide their decision processes. The new optimistic expectations shape their positive attitude towards the ERP initiative and, thus, their direct or indirect support towards it, which is needed to guarantee the potential flow of future benefits. Conversely, although lower expectations do not necessarily prevent the achievement of a benefit, they may reduce the stakeholders’ support and the interest towards the ERP initiative. If the attainment of one or more benefits does not reshape any low expectation positively, the system might be abandoned.

5.2 Implications for theory and practice

The proposed explanations for the causal mechanisms conducive to ERP success have some implications for the ERP success research stream. First, in evaluating the quality of an ERP system and of the information it generates, e . g ., through the renowned System Quality and Information Quality constructs [ 91 ], it may advisable to consider the degree to which the desirable system and information specifications are fulfilled over time. This introduces a temporal dimension in the evaluation to reflect the evidence that ERP specifications are not a long-lasting constraint to be verified in the go-live date only. Instead, their assessment should account for the potential interventions on the ERP to cope with future, contingent upgrades/changes in the system or in its information during the ERP whole life cycle. It is not uncommon for turbulent market environments to call for changes in the business requirements during the onward/upward phase, which may imply adjustments in the ERP system and/or in the business processes over time [ 92 , 93 ]. Although the quality aspects have largely been considered in the ERP success literature [ e . g ., 30 , 32 , 55 , 56 , 63 , 65 , 94 , 95 ], to the best of our knowledge their multiple evaluations over time have never been linked to any ERP success causal mechanism. Staehr and colleagues [ 53 ] cunningly posited that additional IS projects may leverage off the ERP system to drive ERP benefits over time. Yet, they did not draw any relationship between ERP success and the longitudinal evaluation of the system and information quality. Instead, according to our findings, this overlooked aspect is critical to guarantee logical and temporal continuity between direct stakeholders’ expectations, proficient usability, and enhanced interaction over time.

Second, our findings suggest that the user-system interaction should be conceptualised as a cognition to capture the user cognitive progresses regarding aware and knowledgeable use. This is relevant because some ERP benefits are obtained only by massive use over long time [ 27 ], and their achievement is also affected by the user cognitive changes needed to adapt to the ERP modifications. The ERP success literature has mostly considered user-system interaction as a behavioural form of use, which cannot explain ERP success because frequency-related measurement of user-system interaction do not necessarily entail success [ 96 ]. For instance, [ 56 ] dropped any use-related variable in investigating the role of Information Technology governance in driving the ERP success because they were “ not seen as a fitting dimension of success unless system use is voluntary , which is not the case for ERP ” (p. 260). Our findings confirm this. In addition, they suggest that re-conceptualising the use of the system and of the information it generates as a cognition rather than a behaviour may be more effective in explaining performance improvements [ 97 ]. This provides an alternative view on the user-system interaction issue ( cf . Table 1 ). Indeed, the behavioural conceptualisation is not able to grasp the above-mentioned cognitive aspects based on the system-task-user interdependence, which is instead fundamental to include the ERP integration and complexity notions while conceiving the use of an ERP [ 98 ].

Third, the degree to which the realistic expectations of direct and indirect stakeholders are fulfilled does matter to the achievement of the ERP benefits flow. Although [ 99 ] found that creating and maintaining realistic expectations of future benefits may positively affect the level of perceived benefits, the ERP literature has not addressed the role of the expectations in explaining the benefits flow from a multi-stakeholder perspective. Yet, we found that the expectations-benefits compliance may causally ensure the necessary endorsement, funding, and active participation and interaction to attain the distributed flow of benefits over time. Thus, to address the multi-stakeholder perspective in theorising and assessing ERP success, such a compliance should not be overlooked.

From a managerial standpoint, our findings provide useful hints. First, users should be enabled to work with higher self-cognition and with increased system and information awareness and knowledge to beget a benefits-generative enhanced interaction. To satisfy both direct and indirect stakeholders, the enhanced interaction should be consistent over time and should be constantly intertwined with high ERP proficient usability, which should be assessed in multiple points in time according to the system life cycle ( e . g ., at fixed time intervals and after system every update). In this regard, the top management may design an incentive system to foster enhanced interaction, e . g ., a system that grants benefits to the users that exhibit increased system awareness in carrying out their activities. Second, it is advisable to assess the expectations-benefits compliance over time to figure out if the Correspondence-Interaction-Expectation loops maximise the ERP benefits flow. This knowledge of the ERP success causal mechanisms may help firms in better addressing the managerial efforts, reducing both the squandered resources during the ERP life cycle and the variability in achieving the ERP benefits. In turn, this may positively affect the propensity towards any rollout initiative.

6. Conclusions

The outstanding efforts spent by academics and practitioners over the last twenty years have transformed the ERP phenomenon in a renowned and mature reality. Nonetheless, the ERP acronym is still associated not only with long-lasting holistic benefits, but also with episodes of echoing failures, financial meltdown, and notorious lawsuits. Despite some notably contributions [ e . g ., 53 , 100 ], why ERP initiatives do succeed in the long run is largely unaddressed. One of the main reasons for this gap may be the lack of the context-specific "multi-stakeholder perspective" boundary condition in addressing ERP success. This widens the gap between any theoretical explanation of ERP success and the empirical occurrence of such a phenomenon, and may imply theoretical inconsistency. To fill this gap, we adopted the inductive case-based theory-building methodology by [ 24 ] and different qualitative data analysis techniques by [ 86 ] to explain why ERP success may occur. Thereby, we developed an ERP success causal network that embeds the multi-stakeholder overlooked boundary condition.

According to the findings, we justified the occurrence of the main Causal Chains by leveraging the Expectation-Confirmation Theory and the Theory of Effective Use. We argue that ERP post-implementation success may occur because of the conjoint and synergistic action of causal mechanisms related to ERP specifications, users’ cognitions, and stakeholders’ expectations. Thereby, this manuscript contributes to the understanding of the why theoretical criterion of the ERP success and proposes some implications regarding the ERP post-implementation success theorisation.

Nonetheless, this work is not free from limitations. Despite its appropriateness in establishing relationships among variables, case research methodology cannot always specify the direction of causation [ 78 ]. Moreover, although four cases provide sufficient explanatory power to attempt theory building [ 24 ], additional cases would have implied higher confidence in the completeness of the theory. Although no idiosyncratic evidences were found, more cases may have further reduced the gap between the ERP success causal network and the empirical phenomenon under study. This is true for the number of interviews too, which could be increased. In increasing the number of the cases, the data collection may be extended to non-European implementations to take into consideration possible ERP cultural misfits [ 101 ]. In fact, the geographical context which the cases were developed in might affect the managerial conduct [ 102 , 103 ].

The possible avenues for further research are rooted in such limitations. First, additional case studies may be conducted to strengthen the internal validity of the conclusions. Second, the explanation of the causal mechanisms we analysed may be formalised into a success model that may be operationalised and tested. This may open the way to the empirical application of a validated model. Third, text mining tools may be used to automate the analysis of the interview data and, thus, to account for additional data sources and larger data samples.

Supporting information

Funding statement.

The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Data Availability

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

- Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP)

- Understanding ERP

ERP Solutions Providers

The bottom line.

- Supply Chain

Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP): Meaning, Components, and Examples

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Group1805-3b9f749674f0434184ef75020339bd35.jpg)

What Is Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP)?

Enterprise resource planning (ERP) is a platform companies use to manage and integrate the essential parts of their businesses. Many ERP software applications are critical to companies because they help them implement resource planning by integrating all the processes needed to run their companies with a single system.

An ERP software system can also integrate planning, purchasing inventory, sales, marketing, finance, human resources, and more.

Key Takeaways

- ERP software can integrate all of the processes needed to run a company.

- ERP solutions have evolved over the years, and many are now typically web-based applications that users can access remotely.

- Some benefits of ERP include the free flow of communication between business areas, a single source of information, and accurate, real-time data reporting.

- There are hundreds of ERP applications a company can choose from, and most can be customized.

- An ERP system can be ineffective if a company doesn't implement it carefully.

Investopedia / Joules Garcia

Understanding Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP)

You can think of an enterprise resource planning system as the glue that binds together the different computer systems for a large organization. Without an ERP application, each department would have its system optimized for its specific tasks. With ERP software, each department still has its system, but all of the systems can be accessed through one application with one interface.

What Does ERP Do?

ERP applications also allow the different departments to communicate and share information more easily with the rest of the company. It collects information about the activity and state of different divisions, making this information available to other parts, where it can be used productively.

ERP applications can help a corporation become more self-aware by linking information about production, finance, distribution, and human resources together. Because it connects different technologies used by each part of a business, an ERP application can eliminate costly duplicates and incompatible technology. The process often integrates accounts payable, stock control systems, order-monitoring systems, and customer databases into one system.

How Does It Work?

ERP has evolved over the years from traditional software models that made use of physical client servers and manual entry systems to cloud-based software with remote, web-based access. The platform is generally maintained by the company that created it, with client companies renting services provided by the platform.

Businesses select the applications they want to use. Then, the hosting company loads the applications onto the server the client is renting, and both parties begin working to integrate the client's processes and data into the platform.

Once all departments are tied into the system, all data is collected on the server and becomes instantly available to those with permission to use it. Reports can be generated with metrics, graphs, or other visuals and aids a client might need to determine how the business and its departments are performing.

A company could experience cost overruns if its ERP system is not implemented carefully.

Benefits of Enterprise Resource Planning

Businesses employ enterprise resource planning (ERP) for various reasons, such as expanding, reducing costs, and improving operations. The benefits sought and realized between companies may differ; however, some are worth noting.

Improves Accuracy and Productivity

Integrating and automating business processes eliminates redundancies and improves accuracy and productivity. In addition, departments with interconnected processes can synchronize work to achieve faster and better outcomes.

Improves Reporting

Some businesses benefit from enhanced real-time data reporting from a single source system. Accurate and complete reporting help companies adequately plan, budget, forecast, and communicate the state of operations to the organization and interested parties, such as shareholders.

Increases Efficiency

ERPs allow businesses to quickly access needed information for clients, vendors, and business partners. This contributes to improved customer and employee satisfaction, quicker response rates, and increased accuracy rates. In addition, associated costs often decrease as the company operates more efficiently.

ERP software also provides total visibility, allowing management to access real-time data for decision-making .

Increases Collaboration

Departments are better able to collaborate and share knowledge; a newly synergized workforce can improve productivity and employee satisfaction as employees are better able to see how each functional group contributes to the mission and vision of the company. Also, menial and manual tasks are eliminated, allowing employees to allocate their time to more meaningful work.

ERP Weaknesses

An ERP system doesn't always eliminate inefficiencies within a business or improve everything. The company might need to rethink how it's organized or risk ending up with incompatible technology.