- Utility Menu

fa3d988da6f218669ec27d6b6019a0cd

A publication of the harvard college writing program.

Harvard Guide to Using Sources

- The Honor Code

- Summarizing, Paraphrasing, and Quoting

Depending on the conventions of your discipline, you may have to decide whether to summarize a source, paraphrase a source, or quote from a source.

When and how to summarize

When you summarize, you provide your readers with a condensed version of an author's key points. A summary can be as short as a few sentences or much longer, depending on the complexity of the text and the level of detail you wish to provide to your readers. You will need to summarize a source in your paper when you are going to refer to that source and you want your readers to understand the source's argument, main ideas, or plot (if the source is a novel, film, or play) before you lay out your own argument about it, analysis of it, or response to it.

Before you summarize a source in your paper, you should decide what your reader needs to know about that source in order to understand your argument. For example, if you are making an argument about a novel, you should avoid filling pages of your paper with details from the book that will distract or confuse your reader. Instead, you should add details sparingly, going only into the depth that is necessary for your reader to understand and appreciate your argument. Similarly, if you are writing a paper about a journal article, you will need to highlight the most relevant parts of the argument for your reader, but you should not include all of the background information and examples. When you have to decide how much summary to put in a paper, it's a good idea to consult your instructor about whether you are supposed to assume your reader's knowledge of the sources.

Guidelines for summarizing a source in your paper

- Identify the author and the source.

- Represent the original source accurately.

- Present the source’s central claim clearly.

- Don’t summarize each point in the same order as the original source; focus on giving your reader the most important parts of the source

- Use your own words. Don’t provide a long quotation in the summary unless the actual language from the source is going to be important for your reader to see.

Stanley Milgram (1974) reports that ordinarily compassionate people will be cruel to each other if they are commanded to be by an authority figure. In his experiment, a group of participants were asked to administer electric shocks to people who made errors on a simple test. In spite of signs that those receiving shock were experiencing great physical pain, 25 of 40 subjects continued to administer electric shocks. These results held up for each group of people tested, no matter the demographic. The transcripts of conversations from the experiment reveal that although many of the participants felt increasingly uncomfortable, they continued to obey the experimenter, often showing great deference for the experimenter. Milgram suggests that when people feel responsible for carrying out the wishes of an authority figure, they do not feel responsible for the actual actions they are performing. He concludes that the increasing division of labor in society encourages people to focus on a small task and eschew responsibility for anything they do not directly control.

This summary of Stanley Milgram's 1974 essay, "The Perils of Obedience," provides a brief overview of Milgram's 12-page essay, along with an APA style parenthetical citation. You would write this type of summary if you were discussing Milgram's experiment in a paper in which you were not supposed to assume your reader's knowledge of the sources. Depending on your assignment, your summary might be even shorter.

When you include a summary of a paper in your essay, you must cite the source. If you were using APA style in your paper, you would include a parenthetical citation in the summary, and you would also include a full citation in your reference list at the end of your paper. For the essay by Stanley Milgram, your citation in your references list would include the following information:

Milgram, S. (1974). The perils of obedience. In L.G. Kirszner & S.R. Mandell (Eds.), The Blair reader (pp.725-737).

When and how to paraphrase

When you paraphrase from a source, you restate the source's ideas in your own words. Whereas a summary provides your readers with a condensed overview of a source (or part of a source), a paraphrase of a source offers your readers the same level of detail provided in the original source. Therefore, while a summary will be shorter than the original source material, a paraphrase will generally be about the same length as the original source material.

When you use any part of a source in your paper—as background information, as evidence, as a counterargument to which you plan to respond, or in any other form—you will always need to decide whether to quote directly from the source or to paraphrase it. Unless you have a good reason to quote directly from the source , you should paraphrase the source. Any time you paraphrase an author's words and ideas in your paper, you should make it clear to your reader why you are presenting this particular material from a source at this point in your paper. You should also make sure you have represented the author accurately, that you have used your own words consistently, and that you have cited the source.

This paraphrase below restates one of Milgram's points in the author's own words. When you paraphrase, you should always cite the source. This paraphrase uses the APA in-text citation style. Every source you paraphrase should also be included in your list of references at the end of your paper. For citation format information go to the Citing Sources section of this guide.

Source material

The problem of obedience is not wholly psychological. The form and shape of society and the way it is developing have much to do with it. There was a time, perhaps, when people were able to give a fully human response to any situation because they were fully absorbed in it as human beings. But as soon as there was a division of labor things changed.

--Stanley Milgram, "The Perils of Obedience," p.737.

Milgram, S. (1974). The perils of obedience. In L.G. Kirszner & S.R. Mandell (Eds.), The Blair reader (pp.725-737). Prentice Hall.

Milgram (1974) claims that people's willingness to obey authority figures cannot be explained by psychological factors alone. In an earlier era, people may have had the ability to invest in social situations to a greater extent. However, as society has become increasingly structured by a division of labor, people have become more alienated from situations over which they do not have control (p.737).

When and how much to quote

The basic rule in all disciplines is that you should only quote directly from a text when it's important for your reader to see the actual language used by the author of the source. While paraphrase and summary are effective ways to introduce your reader to someone's ideas, quoting directly from a text allows you to introduce your reader to the way those ideas are expressed by showing such details as language, syntax, and cadence.

So, for example, it may be important for a reader to see a passage of text quoted directly from Tim O'Brien's The Things They Carried if you plan to analyze the language of that passage in order to support your thesis about the book. On the other hand, if you're writing a paper in which you're making a claim about the reading habits of American elementary school students or reviewing the current research on Wilson's disease, the information you’re providing from sources will often be more important than the exact words. In those cases, you should paraphrase rather than quoting directly. Whether you quote from your source or paraphrase it, be sure to provide a citation for your source, using the correct format. (see Citing Sources section)

You should use quotations in the following situations:

- When you plan to discuss the actual language of a text.

- When you are discussing an author's position or theory, and you plan to discuss the wording of a core assertion or kernel of the argument in your paper.

- When you risk losing the essence of the author's ideas in the translation from their words to your own.

- When you want to appeal to the authority of the author and using their words will emphasize that authority.

Once you have decided to quote part of a text, you'll need to decide whether you are going to quote a long passage (a block quotation) or a short passage (a sentence or two within the text of your essay). Unless you are planning to do something substantive with a long quotation—to analyze the language in detail or otherwise break it down—you should not use block quotations in your essay. While long quotations will stretch your page limit, they don't add anything to your argument unless you also spend time discussing them in a way that illuminates a point you're making. Unless you are giving your readers something they need to appreciate your argument, you should use quotations sparingly.

When you quote from a source, you should make sure to cite the source either with an in-text citation or a note, depending on which citation style you are using. The passage below, drawn from O’Brien’s The Things They Carried , uses an MLA-style citation.

On the morning after Ted Lavender died, First Lieutenant Jimmy Cross crouched at the bottom of his foxhole and burned Martha's letters. Then he burned the two photographs. There was a steady rain falling, which made it difficult, but he used heat tabs and Sterno to build a small fire, screening it with his body holding the photographs over the tight blue flame with the tip of his fingers.

He realized it was only a gesture. Stupid, he thought. Sentimental, too, but mostly just stupid. (23)

O'Brien, Tim. The Things They Carried . New York: Broadway Books, 1990.

Even as Jimmy Cross burns Martha's letters, he realizes that "it was only a gesture. Stupid, he thought. Sentimental too, but mostly just stupid" (23).

If you were writing a paper about O'Brien's The Things They Carried in which you analyzed Cross's decision to burn Martha's letters and stop thinking about her, you might want your reader to see the language O'Brien uses to illustrate Cross's inner conflict. If you were planning to analyze the passage in which O'Brien calls Cross's realization stupid, sentimental, and then stupid again, you would want your reader to see the original language.

- Locating Sources

- Evaluating Sources

- Sources and Your Assignment

- A Source's Role in Your Paper

- Choosing Relevant Parts of a Source

- The Nuts & Bolts of Integrating

PDFs for This Section

- Using sources

- Integrating Sources

- Online Library and Citation Tools

Summarizing and Paraphrasing in Academic Writing

“It’s none of their business that you have to learn to write. Let them think you were born that way.” – Ernest Hemingway

Plato considers art (and therefore writing) as being mimetic in nature. Writing in all forms and for all kinds of audience involves thorough research. Often, there is a grim possibility that an idea you considered novel has already been adequately explored; however, this also means there are multiple perspectives to explore now and thereby to learn from.

Being inspired by another’s idea opens up a world of possibilities and thus several ways to incorporate and assimilate them in writing, namely, paraphrasing , summarizing, and quoting . However, mere incorporation does not bring writing alive and make it appealing to readers . The incorporation of various ideas must reflect the writer’s understanding and interpretation of them as well.

What is Quoting, Paraphrasing, and Summarizing in Academic Writing?

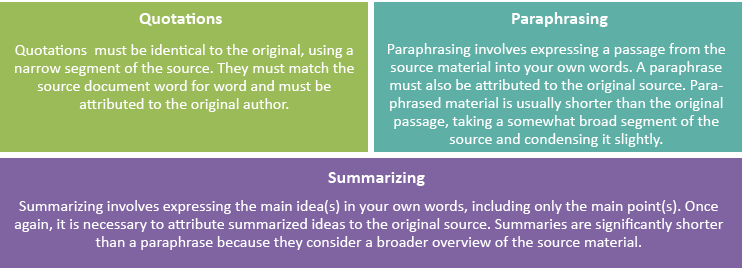

Purdue OWL defines these devices of representation quite succinctly:

Therefore, paraphrasing and summarizing consider broader segments of the main text, while quotations are brief segments of a source. Further, paraphrasing involves expressing the ideas presented from a particular part of a source (mostly a passage) in a condensed manner, while summarizing involves selecting a broader part of a source (for example, a chapter in a book or an entire play) and stating the key points. In spite of subtle variations in representation, all three devices when employed must be attributed to the source to avoid plagiarism .

Related: Finished drafting your manuscript? Check these resources to avoid plagiarism now!

Why is it Important to Quote, Paraphrase, and Summarize?

Quotations, paraphrases, and summaries serve the purpose of providing evidence to sources of your manuscript. It is important to quote, paraphrase, and summarize for the following reasons:

- It adds credibility to your writing

- It helps in tracking the original source of your research

- Delivers several perspectives on your research subject

Quotations/Quoting

Quotations are exact representations of a source, which can either be a written one or spoken words. Quotes imbue writing with an authoritative tone and can provide reliable and strong evidence. However, quoting should be employed sparingly to support and not replace one’s writing.

How Do You Quote?

- Ensure that direct quotes are provided within quotation marks and properly cited

- A Long quote of three or more lines can be set-off as a blockquote (this often has more impact)

- Short quotes usually flow better when integrated within a sentence

Paraphrasing

Paraphrasing is the manner of presenting a text by altering certain words and phrases of a source while ensuring that the paraphrase reflects proper understanding of the source. It can be useful for personal understanding of complex concepts and explaining information present in charts, figures , and tables .

How Do You Paraphrase?

- While aligning the representation with your own style (that is, using synonyms of certain words and phrases), ensure that the author’s intention is not changed as this may express an incorrect interpretation of the source ideas

- Use quotation marks if you intend to retain key concepts or phrases to effectively paraphrase

- Use paraphrasing as an alternative to the abundant usage of direct quotes in your writing

Summarizing

Summarizing involves presenting an overview of a source by omitting superfluous details and retaining only the key essence of the ideas conveyed.

How Do You Summarize?

- Note key points while going through a source text

- Provide a consolidated view without digressions for a concrete and comprehensive summary of a source

- Provide relevant examples from a source to substantiate the argument being presented

“Nature creates similarities. One need only think of mimicry. The highest capacity for producing similarities, however, is man’s. His gift of seeing resemblances is nothing other than a rudiment of the powerful compulsion in former times to become and behave like something else.” –Walter Benjamin

Quoting vs Paraphrasing vs Summarizing

Research thrives as a result of inspiration from and assimilation of novel concepts. However, do ensure that when developing and enriching your own research, proper credit is provided to the origin . This can be achieved by using plagiarism checker tool and giving due credit in case you have missed it earlier.

Source: https://student.unsw.edu.au/paraphrasing-summarising-and-quoting

Amazing blog actually! a lot of information is contained and i have really learnt a lot. Thank you for sharing such educative article.

hi, I enjoyed the article. It’s very informative so that I could use it in my writings! thanks a lot.

hi You are really doing a good job keep up the good work

Great job! Keep on.

nice work and useful advises… thank you for being with students

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Language & Grammar

- Reporting Research

Best Plagiarism Checker Tool for Researchers — Top 4 to choose from!

While common writing issues like language enhancement, punctuation errors, grammatical errors, etc. can be dealt…

How to Use Synonyms Effectively in a Sentence? — A way to avoid plagiarism!

Do you remember those school days when memorizing synonyms and antonyms played a major role…

- Manuscripts & Grants

Reliable and Affordable Plagiarism Detector for Students in 2022

Did you know? Our senior has received a rejection from a reputed journal! The journal…

- Publishing Research

- Submitting Manuscripts

3 Effective Tips to Make the Most Out of Your iThenticate Similarity Report

This guest post is drafted by an expert from iThenticate, a plagiarism checker trusted by the world’s…

How Can Researchers Avoid Plagiarism While Ensuring the Originality of Their Manuscript?

Ten Reasons Why Elsevier Journals Reject Your Article

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What should universities' stance be on AI tools in research and academic writing?

2b. Reading Analysis: Summarizing, Paraphrasing, and Quoting

Summarizing sources, writing with other voices.

In most of your college writing, which is evidence-based writing, you’ll need to incorporate sources. In some writing assignments, you’ll be asked to interpret and analyze a text or texts. The text is the subject of your writing, and your interpretation of the text will need to be supported with evidence from the text. In other writing assignments, you’ll need to support a thesis with evidence from texts and sources. When you incorporate a text or source should generally be performing one of four functions:

- Helping to provide context for your inquiry or argument

- Supporting a claim you are making

- Illustrating a claim you are making

- Providing a different perspective or counterargument to a claim you are making

When you incorporate other voices–texts and sources–into your writing, you will either summarize, paraphrase, or quote them in order to distinguish them for your voice and ideas.

Overview of Summarizing, Paraphrasing, and Quoting Texts and Sources

Quotations must be identical to the original, using a narrow segment of the source. They must match the source document word for word and must be attributed to the original author.

Paraphrasing involves putting a passage from source material into your own words. A paraphrase must also be attributed to the original source. Paraphrased material is usually shorter than the original passage, taking a somewhat broader segment of the source and condensing it slightly.

Summarizing involves putting the main idea(s) into your own words, including only the main point(s). Once again, it is necessary to attribute summarized ideas to the original source. Summaries are significantly shorter than the original and take a broad overview of the source material.

Writers frequently intertwine summaries, paraphrases, and quotations. As part of a summary of an article, a chapter, or a book, a writer might include paraphrases of various key points blended with quotations of striking or suggestive phrases as in the following example:

In his article “What’s The Matter With College?,” Rick Perlstein argues that college, in American society and individual lives, is not as significant as it was in the 1960s, because colleges are no longer sites of radical protest, heated intellectual debate, or freedom from parental authority for students. Perlstein waxes nostalgic over the 1966 California gubernatorial race between Ronald Reagan and Pat Brown when the University of California’s Berkeley campus—a locus for “building takeovers, antiwar demonstrations and sexual orgies”—became a key campaign issue. These days, “[c]ollege campuses seem to have lost their centrality,” according to Perlstein, and do not offer a “democratic and diverse culture” that stood apart from the rest of society and constituted “the most liberating moment” in a student’s life (par. 1).

Use the following pro tips as you read texts and sources so when it comes time to write you have quotations, paraphrases, and summaries ready!

- Read the entire text, noting the key points and main ideas.

- Summarize in your own words what the single main idea of the text is.

- Paraphrase important supporting points that come up in the text.

- Consider any words, phrases, or brief passages that you believe should be quoted directly.

Summarizing Texts and Sources in Your Writing

Generally speaking, a summary must at once be true to what the original author says while also emphasizing those aspects of what the author says that interest you, the writer. You need to summarize the work of other authors in light of your own topic and argument. Writers who summarize without regard to their own interests often create “list summaries” that simply inventory the original author’s main points (signaled by words like “first,” “second,” “and then,” “also,” and “in addition”), but fail to focus those points around any larger overall claim. Writing a good summary means not just representing an author’s view accurately but doing so in a way that fits the larger agenda of your own piece of writing.

The following is a two-sentence template* for a summary adapted from the work of writing scholar Katherine Woodworth that captures 1) info on the author/text and the text’s main point; and 2) the point or example that relates to the point you’re making:

[ Author’s credentials ] [ author’s first and last name ] in his/her [ type of text ] [ title of text ], published in [ publishing info ] addresses the topic of [ topic of text ] and argues/reports that [ argument/general point ]. [Author’s surname] claims/asserts/makes the point/suggests/describes/explains that _____.

See the two-sentence summary template in action:

Example . English professor and textbook author Sheridan Baker, in his essay “Attitudes” (1966), asserts that writers’ attitudes toward their subjects, audiences, and themselves determine to a large extent the quality of their prose. Baker gives examples of how negative attitudes can make writing unclear, pompous, or boring, concluding that a good writer “will be respectful toward his audience, considerate toward his readers, and somehow amiable toward human failings” (58).

NOTE that the first sentence identifies the author (Baker), the genre (essay), the title and date, and uses an active verb (asserts) and the relative pronoun that to explain what exactly Baker asserts. The second sentence gives more specific detail on a relevant point Baker makes.

More examples!

Example . In his essay “On Nature” (1850), British philosopher John Stuart Mill argues that using nature as a standard for ethical behavior is illogical. He defines nature as “all that exists or all that exists without the intervention of man.”

Example . In his essay “Panopticism,” French philosopher Michel Foucault argues that the “panopticon” is how institutions enforce discipline and conformity by making every subject feel like they are being watched by a central authority with the capability of punishing wrongdoing. He concludes that it should not be “surprising that prisons resemble factories, schools, barracks, hospitals, which all resemble prisons” (249).

Example . Independent scholar Indur M. Goklancy, in a policy analysis for the Cato Institute, argues that globalization has created benefits in overall “human well-being.” He provides statistics that show how factors such as mortality rates, child labor, lack of education, and hunger have all decreased under globalization.

NOTE that the above examples prompt the writer to develop a more detailed interpretation and explanation of the point/example made in the second sentence. That’s the work of developing a paragraph with a text or source! You can see what that looks like more fully in Integrating Quotes and Paraphrases into Your Writing .

Acknowledgments:

The summary template is adapted from Woodworth, Margaret K. “The Rhetorical Précis.” Rhetoric Review 7 (1988): 156-164.

Integrating Quotes and Paraphrases into Writing

Image: Sculpting from raw material; Piqsels

“Integrating” means to combine two or more separate elements or things into a cohesive whole. Obviously, as you bring other perspectives (readings and texts) into your writing, you’re combining the work and words of others with your own original ideas. However, you should be strategic in the choices that you make–not every author needs to be quoted directly, not every passage of text needs to have every word or phrase quoted directly, and not every source will contribute multiple quotes or paraphrases to your essay. That’s why we like the analogy of a sculptor at this point in the writing process. Now that you’ve collected the raw material you need to support your argument through thorough research, it’s time to shape it carefully and deliberately so that it combines with your own writing to create an appealing experience for your reader. On to the sculpting!

When to Paraphrase:

- When you need to communicate the main idea of a source, but the details are not relevant/important

- When the source isn’t important enough to take up significant space

- Any time you feel like you can state what the source claims more concisely or clearly

- Any time you think you can state what the source claims in a way that’s more appealing to the reader

When to quote directly:

- When incorporating an influential or significant voice into your essay

- The words themselves clearly back up your claims, and come from a good authority

- The words are unique/original, and already clearly express your key concepts in a compelling or interesting way

- There’s no better way to present those main ideas to the reader than how the original author has stated them

- When engaging with a source that disagrees with you, so you can state the argument fairly

A note on “cherry-picking” : Cherry-picking is a pejorative term that refers to writers using quotes or paraphrases to support their own argument, even though the source would likely disagree with how their words or ideas are being used. Responsible academic writing means presenting evidence in a context that’s consistent and appropriate with the source’s original use of the quote or paraphrase.

Placing Direct Quotes in Your Essay

Here’s a helpful acronym that will remind you of the steps to take to most effectively incorporate direct quotations into your argument: I.C.E (Introduce, Cite, Explain). I’ll use it as a verb to remind myself when constructing a paragraph: “Did I make sure to ICE my quotes?”

Image: Ice, Ice, baby; Pexels , CC0

I ntroduce:

Introduce the quote before providing it. Sometimes this is as simple as “Author X states” or some variation of that phrase. If it’s the first time you’re quoting an author, it’s a good idea to give the author’s full name, but you can rely on the surname in subsequent quotations. If there is context you’d like the reader to know about source, it’s generally wise to provide that before the quote, as part of its introduction. Avoid using “says” when introducing quotations unless you are citing a speech, interview, or other spoken text; “writes,” “states,” “explains,” “argues,” etc. are better options.

C ite:

Every style (MLA, APA, Chicago) has different formats for citations, but anything that isn’t common knowledge–whether you’re directly quoting or paraphrasing, must come with a citation. We’re using MLA format in this class, so make sure you understand the rules of MLA Citations and Formatting.

Example: In the “Higher Laws” chapter of Walden , Henry David Thoreau seems to become despondent over his inability to overcome what he calls “this slimy beastly life” (148).

(For reference, the introduction of the quote is underlined, while the citation is bolded; you won’t do this when you actually cite. If you introduce a quote by using the author’s name, you only need to provide the page number where the quote can be found. Otherwise, their last name will also need to appear in the citation.)

You should always take time to explain quotations, paraphrases, and other types of evidence that you include. Readers look for your analysis of evidence in academic writing, and without it, a reader may draw different conclusions about the relationship between evidence and claim than you do. This is why the basic format for making an argument in academic writing is claim –> evidence to support claim –> reasons why you think the evidence supports the claim.

The Explanation of a quote or paraphrase is where you’re showing the reader your critical thinking, analytical skills, and ability to present your original ideas clearly and concisely. It is the part of the essay where you’re really presenting your original ideas and perspectives on a topic–that makes it very important!

Template for a Paragraph with Direct Quotes

As you read the following example, note where we are introducing, citing, and explaining the quote. .

Example : As I argue above, Thoreau is burdened by the implications of his animal appetites, of the intrinsic sensuality of living in the material world. However, Thoreau’s own language may be creating a heavier burden than he realizes. In Philosophy of Literary Form , Kenneth Burke writes: “. . .if you look for a man’s burden , you will find the principle that reveals the structure of his unburdening; or, in attenuated form, if you look for his problem, you find the lead that explains the structure of his solution” (92, emphasis in original). As this quote suggests, Burke believes that the answer to the problem often lies in the way that the problem is presented by the author or poet. His description of life as “beastly” and “slimy” is an ironic reframing of similar natural elements as those that brought him to Walden Pond in the first place. Thoreau’s choice of terminology to describe something results in the shifting of his attention and priorities.

To think about how I’m structuring this body paragraph, let’s break it down into its constituent parts:

- Topic sentence : As I argued above, Thoreau is burdened by the implications of his animal appetites, of the intrinsic sensuality of living in the material world. This is what the paragraph will be about–Thoreau’s burdens–and I’m telling the reader in one quick phrase how this connects to another part of the essay.

- Paragraph’s Main Claim: However, Thoreau’s own language may be creating a heavier burden than he realizes. This is the main claim I’m making to my reader and is what the rest of the paragraph needs to focus on supporting with evidence and my own analysis. Each paragraph should generally only have one main claim so the reader can stay focused on the argument at hand.

- The Evidence: In Philosophy of Literary Form , Kenneth Burke writes: “. . .if you look for a man’s burden , you will find the principle that reveals the structure of his unburdening; or, in attenuated form, if you look for his problem, you find the lead that explains the structure of his solution” (92, emphasis his). Whether a direct quote or a paraphrase or both, there should be evidence of some sort in all of your body paragraphs (and sometimes in your intro and conclusion, too). It should clearly support the main claim and be cited, whether a quote or a paraphrase. Note that this evidence has the “I” and the “C” of ICE. The next step has the “E.”

- The Explanation: As this quote suggests, Burke believes that the answer to the problem often lies in the way that the problem is presented by the author or poet. His description of life as “beastly” and “slimy” is an ironic reframing of similar natural elements as those that brought him to Walden Pond in the first place. As mentioned above, this is arguably the most critical part of the paragraph. Depending on the evidence and your audience, your explanation might need to summarize the quote in your own words (if it’s complex), but it absolutely needs to analyze the evidence (quote or paraphrase) and explain its relevance or connection to the main claim of the paragraph. It may take one sentence, it may take several.

- The Concluding Sentence: Thoreau’s choice of terminology to describe something results in the shifting of his attention and priorities. Like a conclusion paragraph, this final sentence summarizes the main take-away for the reader of that paragraph its located within.

These parts of the paragraph should be present in any standard body paragraph, but besides the topic and concluding sentences, the other elements can actually be re-ordered (evidence can come before the main claim, if it’s clear which is which!). Use signal phrases and transitions to help guide the reader so they know the purpose of each of your sentences.

A Note on Direct Quotes and Syntax

Quotes (and this can be tricky!) have to be integrated into the correct syntax of your sentences , which may occasionally mean adding a word or clarifying a pronoun. Syntax refers to the ordering of words and expressions within a sentence. Brackets [ ] are useful for maintaining a smooth flow in the syntax of a sentence while integrating a quotation. Brackets are a signal to the reader that you are inserting a word or phrase into into a quotation for the purposes of clarity and correct syntax.

Example : Buell claims that “[Thoreau’s] point was not that we should turn our backs on nature but that we must imagine the ulterior benefits of the original turn to nature in the spirit of economy, both fiscal and ethical” (392).

Pro Tip : Here is what happens to your reader’s attention and understanding of your argument when you don’t match a direct quote’s syntax with the rest of the sentence that you’re placing it into:

Writing as Inquiry Copyright © 2021 by Kara Clevinger and Stephen Rust is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Academic Writing: Summarising, paraphrasing and quoting

- Academic Writing

- Planning your writing

- Structuring your assignment

- Critical Thinking & Writing

- Building an argument

- Reflective Writing

- Summarising, paraphrasing and quoting

Summarising, Paraphrasing and Quotations

Academic writing requires that you use literature sources in your work to demonstrate the extent of your reading (breadth and depth), your knowledge, understanding and critical thinking. Literature can be used to provide evidence to support arguments and can demonstrate your awareness of the research-base that underpins your subject specialism.

There are three ways to introduce the work of others into your assignments: summarising, paraphrasing and quotations.

When, Why & How to Use

- Summarising

- Paraphrasing

Definition: Using your own words to provide a statement (‘summary’) of the main themes, key points, or overarching ideas of a complete text, such as a book, chapter from a book, or academic article.

When to use:

- Useful for providing an overview or background to a topic

- Useful for describing your knowledge and understanding from a single source

- Useful for expressing your combined knowledge and understanding from several sources (synthesis of sources)

Why to use:

- Demonstrates your understanding of your reading

- Demonstrates your ability to identify the main points from a larger body of text or to draw together the main points from several sources

How to use:

- Should offer a balanced representation of the main points

- Should be expressed in your own words (except for technical terminology or conventional terms that appear in the original)

- Should not include detailed discussion or examples

- Should not include information that is not in the original text

- Should avoid using the same sentence structures as the original text

- Read the original text (more than once if necessary) to make sure you fully understand it

- Note the main points in your own words

- Recheck the original text to ensure you have covered the key content and meaning

- Rewrite using formal, grammatically correct academic writing

- Requires in-text citation and referencing

- No page numbers in in-text citation

Example (using Harvard referencing style, from CiteThemRight online, Cite Them Right - Summarising (Harvard) (citethemrightonline.com) :

'Nevertheless, one important study (Harrison, 2007) looks closely at the historical and linguistic links between European races and cultures over the past five hundred years.'

Definition: Using your own words to express an author’s specific point from a short section of text (one or two sentences, or a paragraph), retaining the original meaning.

- Used where the meaning of the text is more important than the exact words

- Useful for expressing the author’s specific point more concisely and in a way that clarifies its relationship to your work

- Useful for stating factual information such as data and statistics from a source

- Demonstrates that you have understood the content and can express it independently, rather than relying on the author’s words

- Allows you to use your own style of writing and your own ‘voice’ in your work

- Allows you to integrate the ideas to fit more readily with your own work and to improve the flow of the writing

- Must not change the original meaning

- Must go further than just changing a few words or changing the word order as this could amount to plagiarism (you would not be fully expressing the idea in your own words)

- Use different sentence structures from the original source

- Use different vocabulary from the original source to convey the meaning

- Read the original text several times, and identify the key content which is important and relevant to your work to distinguish this from content which is less important

- Identify any specialist terminology or key words which are essential

- Think about your reason for paraphrasing and how it relates to your own work

- Roughly note down your understanding of the relevant content in your own words (don’t copy) without looking at the original text

- Reread the original text and refine your notes to ensure that you are not misrepresenting the author, to determine whether you have captured the important aspects of the piece and to make sure your paraphrasing is not too similar to the original

- Rewrite this in formal, grammatically correct academic writing

- Requires page number/s in the in-text citation to precisely locate the original content on which the paraphrasing is based within the source

Example (using Harvard referencing style, from CiteThemRight online, Cite Them Right - Paraphrasing (Harvard) (citethemrightonline.com) :

'Harrison (2007, p. 48) clearly distinguishes between the historical growth of the larger European nation states and the roots of their languages and linguistic development, particularly during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. At this time, imperial goals and outward expansion were paramount for many of the countries, and the effects of spending on these activities often led to internal conflict.'

Definition: Using the author’s exact words to retain the author’s specific form of expression, clearly identifying the quotation as distinct from your own words (for example using quotation marks or indentation).

- Used where the author’s own exact words are important, rather than just the meaning

- Useful where the author’s original choice of words conveys subjective experience, uses persuasive language, or carries emotional force

- Useful where the precise wording is significant, for example in legal texts

- Useful for definitions

- Useful if the author’s own words carry the weight of power and authority that supports your argument

- Useful if you want to critique an author’s point, to ensure you do not misrepresent their meaning

- Useful if you want to disagree with the author as their own words may express their opposition to your argument enabling you to engage with and resist their point of view

- Useful if the author has expressed themselves so concisely, distinctively, and eloquently that paraphrasing would diminish the quality of the statement

- Demonstrates your ability to identify relevant and significant content from a larger body of work

- Demonstrates that you have read and understood the wider context of the quotation and can integrate it into your own work appropriately

- Should be used selectively (over-use of quotations does not demonstrate your own understanding)

- Should not be used just to avoid expressing the meaning in your own words or because you are not confident you have understood the content

- Make sure that the quotation is reproduced accurately, including spelling and punctuation

- Comment on the quotation and its relationship to your point, for example explain its interest and relevance, show how it applies to a particular situation, or discuss its limitations

- Short quotations of no more than three lines should be contained within quotation marks (you can use double or single quotations marks, but be consistent and note that Turnitin only recognises double quotation marks)

- Longer quotations (used sparingly) should be included as a separate paragraph indented from the main text, without quotation marks

- Don’t use quotation marks for technical terminology which is accepted within your specialism, and which is part of the common language of your academic discipline

- Requires page number/s in the in-text citation to precisely locate the quote within the source

Examples (from CiteThemRight online, Cite Them Right - Setting out quotations (Harvard) (citethemrightonline.com) ):

Short quotation (using Harvard referencing style):

'If you need to illustrate the idea of nineteenth-century America as a land of opportunity, you could hardly improve on the life of Albert Michelson’ (Bryson, 2004, p. 156).

Long quotation (using Harvard referencing style):

King describes the intertwining of the fate and memory in many evocative passages, such as:

So the three of them rode towards their end of the Great Road, while summer lay all about them, breathless as a gasp. Roland looked up and saw something that made him forget all about the Wizard’s Rainbow. It was his mother, leaning out of her apartment’s bedroom window: the oval of her face surrounded by the timeless gray stone of the castle’s west wing! (King, 1997, pp. 553-554)

Altering quotations:

You can omit part of a quotation by using three dots (ellipses). Only do this to omit unnecessary words which do not alter the meaning.

Example (from CiteThemRight online, Cite Them Right - Making changes to quotations (citethemrightonline.com) ).

'Drug prevention ... efforts backed this up' (Gardner, 2007, p. 49).

You can insert your own or different words into a quotation by placing them in square brackets. Only do this to add clarity to the quotation where it does not alter the meaning.

Example (from CiteThemRight online, Cite Them Right - Making changes to quotations (citethemrightonline.com) ):

'In this field [crime prevention], community support officers ...' (Higgins, 2008, p. 17).

Further Reading

- << Previous: Reflective Writing

- Next: Hub Home >>

- Last Updated: Jul 29, 2023 3:55 PM

- URL: https://libguides.uos.ac.uk/academic-writing

➔ About the Library

➔ Meet the Team

➔ Customer Service Charter

➔ Library Policies & Regulations

➔ Privacy & Data Protection

Essential Links

➔ A-Z of eResources

➔ Frequently Asked Questions

➔Discover the Library

➔Referencing Help

➔ Print & Copy Services

➔ Service Updates

Library & Learning Services, University of Suffolk, Library Building, Long Street, Ipswich, IP4 1QJ

✉ Email Us: [email protected]

✆ Call Us: +44 (0)1473 3 38700

- Generating Ideas

- Drafting and Revision

- Sources and Evidence

- Style and Grammar

- Specific to Creative Arts

- Specific to Humanities

- Specific to Sciences

- Specific to Social Sciences

- CVs, Résumés and Cover Letters

- Graduate School Applications

- Other Resources

- Hiatt Career Center

- University Writing Center

- Classroom Materials

- Course and Assignment Design

- UWP Instructor Resources

- Writing Intensive Requirement

- Criteria and Learning Goals

- Course Application for Instructors

- What to Know about UWS

- Teaching Resources for WI

- FAQ for Instructors

- FAQ for Students

- Journals on Writing Research and Pedagogy

- University Writing Program

- Degree Programs

- Majors and Minors

- Graduate Programs

- The Brandeis Core

- School of Arts and Sciences

- Brandeis Online

- Brandeis International Business School

- Graduate School of Arts and Sciences

- Heller School for Social Policy and Management

- Rabb School of Continuing Studies

- Precollege Programs

- Faculty and Researcher Directory

- Brandeis Library

- Academic Calendar

- Undergraduate Admissions

- Summer School

- Financial Aid

- Research that Matters

- Resources for Researchers

- Brandeis Researchers in the News

- Provost Research Grants

- Recent Awards

- Faculty Research

- Student Research

- Centers and Institutes

- Office of the Vice Provost for Research

- Office of the Provost

- Housing/Community Living

- Campus Calendar

- Student Engagement

- Clubs and Organizations

- Community Service

- Dean of Students Office

- Orientation

- Spiritual Life

- Graduate Student Affairs

- Directory of Campus Contacts

- Division of Creative Arts

- Brandeis Arts Engagement

- Rose Art Museum

- Bernstein Festival of the Creative Arts

- Theater Arts Productions

- Brandeis Concert Series

- Public Sculpture at Brandeis

- Women's Studies Research Center

- Creative Arts Award

- Our Jewish Roots

- The Framework for the Future

- Mission and Diversity Statements

- Distinguished Faculty

- Nobel Prize 2017

- Notable Alumni

- Administration

- Working at Brandeis

- Commencement

- Offices Directory

- Faculty & Staff

- Alumni & Friends

- Parents & Families

- 75th Anniversary

- New Students

- Shuttle Schedules

- Support at Brandeis

Writing Resources

Summarizing, paraphrasing, and quoting.

This handout is available for download in DOCX format and PDF format .

This handout is intended to help you become more comfortable with the uses of and distinctions among summaries, paraphrases, and quotations.

What are the differences among summarizing, paraphrasing, and quoting?

These three ways of incorporating other writers' work into your own writing differ according to the closeness of your writing to the source writing.

Summarizing

- Summarizing involves putting the main idea(s) into your own words, including only the main point(s). Although you are using your own words, it is still necessary to attribute the summarized ideas to the original source. Summaries are significantly shorter than the original and take a broad overview of the source material.

Paraphrasing

- Paraphrasing involves putting a passage from the source into your own words. A paraphrase must also be attributed to the original source. Paraphrased material is usually shorter than the original passage, taking a somewhat broader segment of the source and condensing it slightly.

- Quotations must be identical to the original, using a narrow segment of the source. They must match the source document word for word and must also be attributed to the original author.

Why use quotations, paraphrases, and summaries?

Quotations, paraphrases, and summaries serve many purposes. You might use them to:

- Provide support for claims or add credibility to your writing

- Refer to work that leads up to the work you are now doing

- Give examples of several points of view on a subject

- Call attention to a position that you wish to agree or disagree with

- Highlight a particularly striking phrase, sentence, or passage by quoting the original

- Distance yourself from the original by quoting it to show that the words are not your own

- Expand the breadth or depth of your writing

Writers frequently intertwine summaries, paraphrases, and quotations, including paraphrases of key points blended with quotations of striking or suggestive phrases as in the following example:

In his famous and influential work The Interpretation of Dreams , Sigmund Freud argues that dreams are the "royal road to the unconscious" (page #), expressing in coded imagery the dreamer's unfulfilled wishes through a process known as the "dream-work" (page #). According to Freud, actual but unacceptable desires are censored internally and subjected to coding through layers of condensation and displacement before emerging in a kind of rebus puzzle in the dream itself (page #).

How and when should I summarize, paraphrase, or quote?

Before you summarize a source in your paper, decide what your reader needs to know about that source in order to understand your argument. For example, if you are making an argument about a novel, avoid filling pages of your paper with details from the book that will distract or confuse your reader. Instead, add details sparingly, going only into the depth that is necessary for your reader to understand and appreciate your argument. Similarly, if you are writing a paper about a non-fiction article, highlight the most relevant parts of the argument for your reader, but do not include all of the background information and examples.

When you use any part of a source in your paper, you will always need to decide whether to quote directly from the source or to paraphrase it. Unless you have a good reason to quote directly from the source, you should paraphrase the source. Make it clear to your reader why you are presenting this particular material from a source, and be sure that you have represented the author accurately, that you have used your own words consistently, and that you have cited the source.

As a basic rule of thumb, you should only quote directly from a text when it is important for your reader to see the actual language used by the author of the source. While paraphrase and summary are effective ways to introduce your reader to someone's ideas, quoting directly from a text allows you to introduce your reader to the way those ideas are expressed by showing such details as language, syntax, and cadence. There are several ways to integrate quotations into your text; often a short quotation works well when integrated into a sentence, while longer quotations can stand alone. Whatever their length, be sure you have a good reason to include a direct quotation when you decide to do so.

You can become more comfortable using these three techniques by summarizing an essay of your choice, using paraphrases and quotations as you go. It might be helpful to follow these steps:

- Read the entire text, noting the key points and main ideas.

- Summarize in your own words what the single main idea of the essay is.

- Paraphrase important supporting points that come up in the essay.

- Consider any words, phrases, or brief passages that you believe should be quoted directly.

Credit: Adapted from the “Harvard Guide to Using Sources,” https://usingsources.fas.harvard.edu/summarizing-paraphrasing-and-quoting , and the Purdue OWL Guide, https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/using_research/quoting_paraphrasing_and_summarizing/index.html , 2020.

- Resources for Students

- Writing Intensive Instructor Resources

- Research and Pedagogy

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Identifying quoting, paraphrasing and summarizing

One common question that most new scholars ask is “how do i know when to quote, paraphrase, or summarize”.

There is no easy answer, it just takes practice. You will work with a number of instructors who will have different ideas on what you should do. To start, here are a few general guidelines.

Use the exact words of an author, copied directly from the source, word for word. You must use quotation marks and an in-text citation.

Use quotes when you want to

- add the power of the author’s words to support your argument or claims

- disagree with something specific an author said

- highlight a specific passage

- compare or contrast points of view

Paraphrasing

Paraphrasing is stating an idea, point or passage in your own words. You must significantly change the wording, phrasing, and sentence structure of the source (not just a few words here and there; don’t just use a thesaurus and change out terms!).

Every paraphrase must also have in-text citations at the end of the paraphrased section and the original source identified on reference or works cited page.

Paraphrase when you want to

- clarify a short passage from a text

- avoid overusing quotations

- explain a point when exact wording isn’t critical

- articulate the main ideas of a passage or part

- report numerical data or statistics

Summarizing

Summaries are a broad overview of the original material as a whole (not just a part, like a paraphrase). You may summarize an entire article, and then also paraphrase a small portion of the author’s findings. Like quotes and paraphrases, a summary must be cited with in-text citations and on your reference or works cited page.

Summarize when you want to:

- give an overview of a topic

- describe information (from several sources) about a topic

Learning these skills takes practice. It is okay if you are feeling overwhelmed.

Time to practice identifying the scholarly conversation →

Academic Integrity at the University of Minnesota Copyright © by University of Minnesota Libraries is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

VCU Writes: A Student’s Guide to Research and Writing

Focused inquiry, apa quoting, paraphrasing and summarizing.

An essential skill in writing is the ability to ethically and accurately share the ideas of others. Quotations, paraphrases and summaries are all methods of including research in your writing or presentations. Here is a quick overview of the difference between quoting, paraphrasing and summarizing:

- What it is: Using the exact words of your source; must be placed within quotation marks.

- When to use it: Specific terminology, powerful phrases.

- Example: McMillan Cottom (2021) explains that “Reading around a subject is about going beyond the object of study to unpack, examine, or pick apart what the person or the object of study represents” (1).

PARAPHRASING

- What it is: Putting another’s ideas into your own words.

- When to use it: To clarify a passage, to avoid over-quoting.

- Example: McMillan Cottom (2021) contends that, in addition to reading about a subject itself, we also need to read about the ideas and concepts that are ingrained in a subject in order to truly understand its deeper meaning (1).

SUMMARIZING

- What it is: Putting a larger main idea into your words.

- When to use it: Overview of a topic, main point/idea.

- Example: In McMillan Cottom’s (2021) article, “Sleep Around Before You Marry an Argument,” she describes the process of preparing to write about a subject and develop an argument. For her, the first and most important stage in this process is reading; however, she isn’t focused on simply reading everything ever written on a topic, but “reading around a subject.” In her view, the end goal is not just to compile facts, but to develop a thorough, but interesting final product that will connect with your audience. (1)

McMillan Cottom, T. (2021, March 8). “Sleep around before you marry an argument.” Essaying , Substack. https://tressie.substack.com/p/sleep-around-before-you-marry-an?utm_source=url

Note: This page reflects the latest version of the APA Publication Manual (APA 7), which released in October 2019.

General Guidelines

While you are still gaining experience and confidence in writing, there is often a temptation to rely heavily on the words and ideas of others. You might think, “How can I possibly say it as well as the expert?” or “How will anyone believe me unless I add in exhaustive research?” However, having confidence in your own ideas is one of the hallmarks of a more experienced writer, and this means that when incorporating the ideas of others, we should not allow them to “take over” our own ideas.

In addition, sometimes it is better to paraphrase or summarize an idea to keep it brief, rather than having an excessively long quotation. (See below for more info on both paraphrasing and summarizing ideas.)

That said, there are a number of reasons why we might want to quote the ideas of others. Here are some of the most common:

- When wording is very distinctive so you cannot paraphrase it adequately;

- When you are using a definition or explaining something very technical;

- When it is important for debaters of an issue to explain their positions in their own words (especially if you have a differing viewpoint);

- When the words of an authority will lend weight to your argument;

- When the language of a source is the topic of your discussion (as in an interpretation).

In certain instances, you do not need to cite information. This is called the “common knowledge rule.” If a fact is widely and generally known (e.g., the sun rises in the east and sets in the west), you do not need to cite. Similarly, familiar sayings or oft-repeated quotations (e.g., “a penny saved is a penny earned”) do not need citations.

Common knowledge can in some cases be audience-specific; research scientists writing to their peers can assume a different level of common knowledge on their subject than when writing to a younger, less educated audience, for example. If you are ever in doubt as to whether you should cite a piece of information, ask your professor or a Writing Center consultant.

Trying to balance your ideas and those of your sources takes a bit of skill and finesse. The goal is to make the ideas (both yours and those of your sources) feel and look like a conversation—a mutual exchange of voices and ideas that helps you and your audience work out your reasoning on a topic. (You can read more about this idea of academic conversations here .) Sometimes, in the process of trying to incorporate the ideas of others, things fall a bit short of the ideal. Here are some common missteps that can lead to your writing seeming less polished:

- Over-using one source: If you find yourself repeatedly citing the same source again and again in your writing, it will begin to seem as if you are merely repackaging the other author’s ideas, rather than presenting your own. It also gives the appearance that your ideas are one-sided, due to the lack of a diversity of voices in the conversation.

- Having more source material than your own original ideas*: Try color-coding your writing. Highlight each instance where you are quoting, paraphrasing or summarizing a source. What’s left? Is your essay a rainbow of colors, with little else? Or are the majority of ideas/sentences yours, with a few well-chosen instances of source material? Aim for the latter; otherwise, it will seem like you are just “reporting out” on all the research you have gathered, rather than developing your own thinking on a subject.

- Does every aspect of this passage relate to my own paragraph ideas?

- Can I cut out a section of this quotation to emphasize the points that are most relevant? (If yes, see below on proper formatting when you eliminate a portion of the quoted material.)

- Would it be easier/better/more concise to paraphrase this idea? (If yes, see below on how to correctly and incorrectly paraphrase.)

- Dropping in a random quote or source reference: Ideas without context are always confusing, whether they are yours or someone else’s. Make sure you provide adequate context and make connections between your ideas and those of your sources.

- Signal phrase (a few words that introduce the author and year of publication for the source; this might also include credentials of the author and/or title of work);

- Quoted, paraphrased or summarized material, followed by a parenthetical citation;

- Your own thinking that expands upon the ideas from the source material, and connects it back to your larger point.

For more on how to effectively incorporate evidence into your writing or presentation, see the handout “What Is Evidence?” here on VCU Writes.

*NOTE : This goal is more applicable to some writing situations than others. In a lab report or literature review, for example, the majority of your discussion might include restating/sharing research. Always confirm with your instructor if you are not sure what the appropriate balance of source material should be for your specific writing situation.

When quoting material from a source, wording and punctuation should be reproduced exactly as it is in the original. If you need to alter the quotation in any way, you must indicate this through punctuation or added material. Otherwise, you will be misrepresenting the ideas of others.

When paraphrasing or summarizing source info, you should still use quotation marks and cite any distinctive wording that you kept from the original.

See below for examples of how to correctly alter quotations.

Direct Quotation of Sources

A . Quotations that are fewer than four lines should be included in the text and enclosed in quotation marks. If you introduce the quotation in a signal phrase with the author’s full name and year of publication (or source title, if the author’s name is not provided), include “p.” and the page number in parentheses after the end of the quotation and before the period. It is not necessary to repeat the name or publication in the parenthetical citation :

On the efficacy and importance of religion, David Hume (2005) asserts , “The life of man is of no greater importance to the universe than that of an oyster” (p. 94) .

B . If you do not introduce the quotation with the author’s full name and publication date (or source title, if the author’s name is not provided), include the author’s last name, publication date, and page number (using “p.” before the number) in parentheses after the end of the quotation and before the period. Use commas to separate each piece of information in the parenthetical citation:

When considering the efficacy and importance of religion, one must understand that “the life of man is of no greater importance to the universe than that of an oyster” (Hume, 2005, p. 94) .

C . If the quotation appears mid-sentence , end the passage with quotation marks, cite the source in parentheses immediately after quotation marks, and finish the sentence:

Based on the findings, Sommerfeldt (2011) argued that “the normative role of public relations in democracy is best perceived as creating the social capital that facilitates access to spheres of public discussion” (p. 664) , challenging dominant notions of democratic discourse.

Quotations that are more than four lines should be displayed in block quotation format . This is an indented passage that does not require quotation marks (the indent serves in place of quotation marks):

In McLuhan’s compass for the voyage to a world of electric words, Terrence Gordon (2011) explains how Marshall McLuhan wrote The gutenberg galaxy :

In a letter written to his in-laws on Christmas Day 1960, Marshall McLuhan mentioned that he had drafted a book in less than a month. Of all his publications, The Gutenberg Galaxy (henceforth GG), so explosive on the page, had the tidiest beginnings. The manuscript flowed from McLuhan’s pen until he had written 399 pages. There he stopped, so that the total of the carefully numbered foolscap sheets would be divisible by three. (p. vii)

Gordon goes on to explain that the number three was a symbol of order for McLuhan throughout his life.

Note that the period at the end of the block quotation is placed at the end of the sentence, rather than after the parenthetical citation. After the quotation is completed, continue your paragraph on the left margin (i.e., don’t indent as if it were a new paragraph).

If the quotation includes an alternate spelling (i.e., British English) or an error in grammar, punctuation, or spelling, write the word “sic” in brackets directly after the alternate spelling or error inside the quotation :

“VCU is well known for it’s [sic] diversity” (Jones, 2017, p. 43).

This lets the reader know that it is the original writer’s spelling or error.

A . Though direct quotations must be accurate, the first letter of the first word in the quotation may be changed either as uppercase or lowercase to match the flow of your sentence. Additionally, the punctuation mark ending a sentence may also be changed if necessary for appropriate syntax.

B . It is sometimes important to insert material when it will help the reader understand the quotation. When inserting material, enclose the insert in brackets:

Original quotation :

“By programming a variety of Twitter bots to respond to racist abuse against black users, he showed that a simple one-tweet rebuke can actually reduce online racism” (Yong, 2016, para 3).

Revised quotation with brackets :

“By programming a variety of Twitter bots to respond to racist abuse against black users, [Kevin Munger] showed that a simple one-tweet rebuke can actually reduce online racism” (Yong, 2016, para 3).

C . When adding emphasis to a section of a quotation, italicize the specific word(s) and write “ emphasis added ” in brackets (e.g.,):

Original quotation:

“By programming a variety of Twitter bots to respond to racist abuse against black users, he showed that a simple one-tweet rebuke can actually reduce online racism” (Yong, 2016, para. 3).

Revised quotation with emphasis :

“By programming a variety of Twitter bots to respond to racist abuse against black users, he showed that a simple one-tweet rebuke [emphasis added] can actually reduce online racism” (Yong, 2016, para. 3).

Note : If words were already italicized in the quoted material, you do not need to include the “emphasis added” designation. It is assumed that all formatting is original to the quotation unless you indicate otherwise.

It is often useful to omit material when you do not need all words or sentences included in the passage you are citing. If you omit material, use three spaced periods (. . .) within a sentence (the three periods are called an ellipsis) to indicate that you have omitted material from the original source:

Ariel Levy notes that “in the decades since the McKennas’ odyssey, the drug . . . has become increasingly popular in the United States” (34).

If you omit material after the end of a sentence, use four spaced periods (. . . .) . This is a period, followed by an ellipsis.

Paraphrasing source material

When a writer uses another person’s idea but puts it in their own words, the writer is paraphrasing . We use paraphrasing when we wish to preserve the original ideas in their entirety (as opposed to summarizing the main points). Some reasons a writer might choose to do this include preserving the flow of their writing, or if quoting the material directly would take up too much space.

It is important to remember that just as with quotations, paraphrased material requires an in-text citation to give credit to the original author .

When paraphrasing or referencing an idea from another source, make sure that you provide enough information for the reader to easily locate the passage from the source you reference (for example, the page number or the paragraph number).

Example paraphrase :

Original passage : “Reading around a subject is about going beyond the object of study to unpack, examine, or pick apart what the person or the object of study represents” (McMillan Cottom, 2021, p. 1).

Unacceptable paraphrase : It’s important to read around the subject that we are studying by examining what that subject represents.

- Issue 1: Certain words from the original are simply moved around.

- Issue 2: Certain words are only replaced with synonyms or similar words.

- Issue 3: The sentence structure has remained the same.

- Issue 4: The source citation is missing.

Acceptable Paraphrase : McMillan Cottom (2021) contends that, in addition to reading about a subject itself, we also need to read about the ideas and concepts that are ingrained in a subject in order to truly understand its deeper meaning (p. 1).

McMillan Cottom, T. (2021, March 8). “Sleep around before you marry an argument.” Essaying, Substack. https://tressie.substack.com/p/sleep-around-before-you-marry-an?utm_source=url

Many writers are reluctant to paraphrase because they worry about making mistakes and unintentionally plagiarizing ideas in their writing. This is a valid concern, but with practice this skill can be developed just like any other. Learning to paraphrase effectively can demonstrate a deeper understanding and command of the ideas you are discussing, and aid in the flow of ideas in your essay or presentation. That said, there are some common mistakes that should be avoided:

- When paraphrasing, make sure that you don’t copy the same pattern of wording as the original sentence or passage . This sometimes happens when a writer tries to just swap out a few words, but keeps the structure of the sentence the same or very similar.

- Likewise, avoid using the same or very similar wording as the original . If your paraphrase includes a word or phrase borrowed from the original, make sure to put that portion in quotation marks.

- As noted above, paraphrases require citations, just like direct quotations. Always include a signal phrase and parenthetical citation to indicate that the info you are sharing is not your own. This is especially important in paraphrasing to make a clear distinction between the writer’s own ideas and the source info. Also, citing your source makes sure that you provide enough information for the reader to easily locate the passage from the source you reference.

To make sure that you don’t fall prey to the above mistakes, read the passage you wish to paraphrase and then put it aside. Without looking at it, try to think about how you can say it in your own words, and write it down. Make sure you aren’t including your own ideas—just try to capture the essence of the original in as clear and straightforward a manner as possible.

Summarizing source material

As explained at the top of this page, a summary is when a writer wants to provide a brief overview of a larger idea. This is distinct from a paraphrase, which usually focuses on a single sentence or paragraph. A writer can summarize an entire essay, a section of an article, or the overall main idea of a composition. While summarizing is perhaps not used as frequently as quoting or paraphrasing in academic writing, it can be an effective critical thinking and reading tool. In fact, your instructor may ask you to do a summary as part of your reading and research gathering to demonstrate your understanding of the material. In most academic writing, summaries should be used sparingly, but can be an efficient way to provide additional context to the intended audience.

It is important to remember that just as with quotations and paraphrases, summarized material requires an in-text citation to give credit to the original author .

When summarizing an idea from another source, make sure that you provide enough information for the reader to easily locate the passage from the source you reference (for example, the page number or the paragraph number).

Example summary :

The following summary focuses on an online article written by Tressie McMillan Cottom, which you can read in full here .

In Tressie McMillan Cottom’s (2021) article, “Sleep Around Before You Marry an Argument,” she describes the process of preparing to write about a subject and develop an argument. For her, the first and most important stage in this process is reading; however, she isn’t focused on simply reading everything ever written on a topic, but “reading around the subject.” In her view, the end goal is not just to compile facts, but to develop a thorough, but interesting final product that will connect with your audience. (p. 1)

There are some common mistakes that should be avoided when summarizing a source:

- Providing too much detail : While a summary is by its nature longer than a paraphrase, too much detail means that you are getting a bit “in the weeds” with your writing. A summary should be focused on the big ideas of a piece of writing, rather than the individual sections or minor points. A good summary should be much shorter than the original; in most cases, a full paragraph will be more than enough.

- Using the same or very similar wording for part of the summary : Just as with paraphrasing, you want to avoid words, phrases, or patterns of wording from the original source. Stick to your own wording/ideas; if your summary does include a word or phrase borrowed from the original, make sure to put that portion in quotation marks.

- Not providing a citation : As with paraphrases and quotations, summaries also require citations. Always include a signal phrase and parenthetical citation to indicate that the ideas you are summarizing are not your own. This is especially important in summarizing to make a clear distinction between your own ideas and the source info. Also, citing your source makes sure that you provide enough information for the reader to easily locate the source you reference.

To make sure that you don’t fall prey to the above mistakes, read the item you wish to summarize and then put it aside. Without looking at it, try to think about how you would explain the main ideas from the source to someone else in your own words, and write that down. Make sure you don’t add your own analysis or opinion—just try to capture the essence of the original in as clear and straightforward a manner as possible.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

15 Planning Your Writing – Quoting, Paraphrasing, and Summarizing

An important part academic writing is incorporating evidence. To do this, you will need to know the basics of quoting, paraphrasing, and summarizing.

Making sure that you are using evidence properly, through quoting, paraphrasing, and summarizing, will ensure that you are giving necessary credit for other peoples’ words and ideas and will help you avoid plagiarism.

The table [1] below describes three different ways of using evidence:

Effectively quoting, paraphrasing, and summarizing always includes citation.

We’ll review some examples of how you can effectively incorporate evidence to support your ideas in the next section. Before we get there, make sure that you are familiar with the citation style and reference style that you are using for your assignment – these can be different for different courses and assignments.

The KPU Library has guides to help you with make sure that you are citing your work correctly, according to the style that your instructor wants you to use. Visit their page here .

If you have questions about how you should be citing evidence, ask your instructor or check with one of the KPU librarians.

Properly Summarizing and Paraphrasing [2]

When you summarize, you should write in your own words and the result should be substantially shorter than the original text. In addition, the sentence structure should be your original format. In other words, you should not take a sentence and replace core words with synonyms (different words with the same meaning) .

You should also use your own words when you paraphrase. Paraphrasing should also involve your own sentence structure. However, paraphrasing might be as long or even longer than the original text. When you paraphrase, you should include, in your words, all the ideas from the original text in the same order as in the original text. You should not insert any of your ideas.

Both summaries and paraphrases should maintain the original author’s intent and perspective. Taking details out of context to suit your purposes is not ethical since it does not honor the original author’s ideas.

Review the examples in the table below to see the difference between quoting, paraphrasing, summarizing, and plagiarizing.

Here is a page from a book written by Maelle Jasper:

In the example of plagiarized text, some of the words from the original text are replaced with synonyms (different words with the same meaning).