Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

17 The SIFT Method

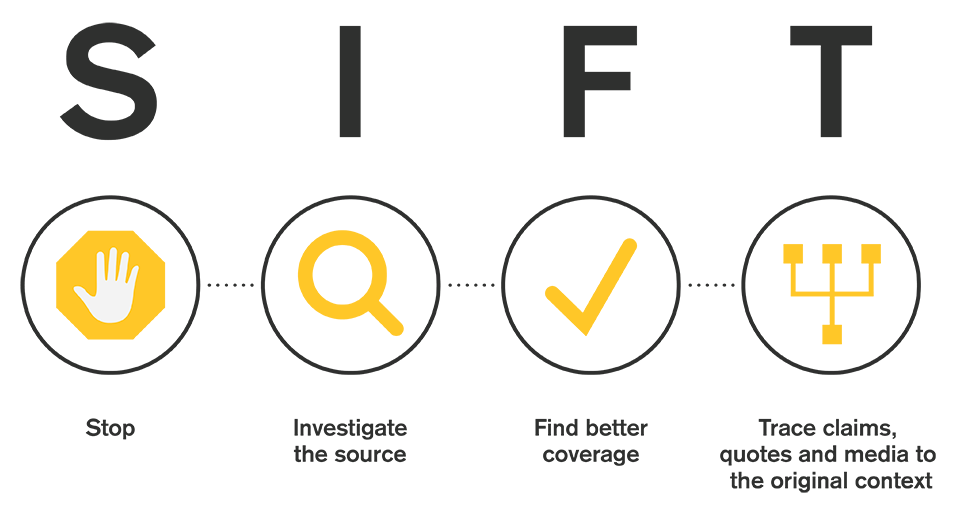

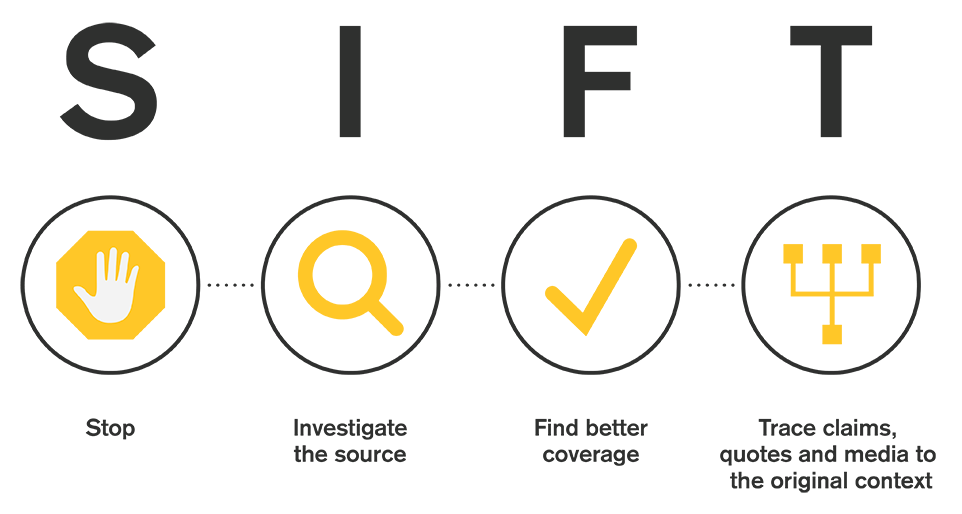

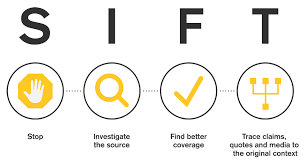

Mike Caulfield, Washington State University digital literacy expert, has helpfully condensed key fact-checking strategies into a short list of four moves, or things to do to quickly make a decision about whether or not a source is worthy of your attention . It is referred to as the “SIFT” method:

When you initially encounter a source of information and start to read it— stop . Ask yourself whether you know and trust the author, publisher, publication, or website. If you don’t, use the other fact-checking moves that follow, to get a better sense of what you’re looking at. In other words, don’t read, share, or use the source in your research until you know what it is, and you can verify it is reliable.

This is a particularly important step, considering what we know about the attention economy —social media, news organizations, and other digital platforms purposely promote sensational, divisive, and outrage-inducing content that emotionally hijacks our attention in order to keep us “engaged” with their sites (clicking, liking, commenting, sharing). Stop and check your emotions before engaging!

Investigate the Source

You don’t have to do a three-hour investigation into a source before you engage with it. But if you’re reading a piece on economics, and the author is a Nobel prize-winning economist, that would be useful information. Likewise, if you’re watching a video on the many benefits of milk consumption, you would want to be aware if the video was produced by the dairy industry. This doesn’t mean the Nobel economist will always be right and that the dairy industry can’t ever be trusted. But knowing the expertise and agenda of the person who created the source is crucial to your interpretation of the information provided.

When investigating a source, fact-checkers read “laterally” across many websites, rather than digging deep (reading “vertically”) into the one source they are evaluating. That is, they don’t spend much time on the source itself, but instead they quickly get off the page and see what others have said about the source. They open up many tabs in their browser, piecing together different bits of information from across the web to get a better picture of the source they’re investigating.

Please watch the following short video [2:44] for a demonstration of this strategy. Pay particular attention to how Wikipedia can be used to quickly get useful information about publications, organizations, and authors.

Note: Turn on closed captions with the “CC” button or use the text transcript if you prefer to read.

Find Better Coverage

What if the source you find is low-quality, or you can’t determine if it is reliable or not? Perhaps you don’t really care about the source—you care about the claim that source is making . You want to know if it is true or false. You want to know if it represents a consensus viewpoint, or if it is the subject of much disagreement. A common example of this is a meme you might encounter on social media. The random person or group who posted the meme may be less important than the quote or claim the meme makes.

Your best strategy in this case might actually be to find a better source altogether , to look for other coverage that includes trusted reporting or analysis on that same claim. Rather than relying on the source that you initially found, you can trade up for a higher quality source.

The point is that you’re not wedded to using that initial source. We have the internet! You can go out and find a better source, and invest your time there. Please watch this video [4:10] that demonstrates this strategy and notes how fact-checkers build a library of trusted sources they can rely on to provide better coverage.

Trace Claims, Quotes, and Media to the Original Context

Much of what we find on the internet has been stripped of context. Maybe there’s a video of a fight between two people with Person A as the aggressor. But what happened before that? What was clipped out of the video and what stayed in? Maybe there’s a picture that seems real but the caption could be misleading. Maybe a claim is made about a new medical treatment based on a research finding—but you’re not certain if the cited research paper actually said that. The people who re-report these stories either get things wrong by mistake, or, in some cases, they are intentionally misleading us.

In these cases you will want to trace the claim, quote, or media back to the source, so you can see it in its original context and get a sense of whether the version you saw was accurately presented. Please watch the following video [1:33] that discusses re-reporting vs. original reporting and demonstrates a quick tip: going “upstream” to find the original reporting source.

“ Online Verification Skills – Video 2: Investigate the Source .” YouTube , uploaded by CTRL-F, 29 June 2018.

“ Online Verification Skills – Video 3: Find the Original Source .” YouTube , uploaded by CTRL-F, 25 May 2018.

“ Online Verification Skills – Video 4: Look for Trusted Work .” YouTube , uploaded by CTRL-F, 25 May 2018.

SIFT text adapted from “ Check, Please! Starter Course ,” licensed under CC BY 4.0

SIFT text and graphics adapted from “ SIFT (The Four Moves) ” by Mike Caulfield, licensed under CC BY 4.0

Introduction to College Research Copyright © by Walter D. Butler; Aloha Sargent; and Kelsey Smith is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Evaluating Sources

The process of evaluating your resources may seem overwhelming, but it doesn’t have to be. Academic books and journals usually present themselves as scholarly and may be easily assessed for their quality of information. But others, especially websites, social media, newspapers, and magazines are not the same and sorting truth from fiction can be very challenging.

Our solution gives you a list of things to do when looking at a source, and hooks each of those things to one or two highly effective evaluation techniques. We call the “things to do” moves and there are four of them S top, I nvestigate, F ind, and T rack.

Licenses and Attributions: SIFT (The Four Moves) Authored by Mike Caulfield. Located at: https://hapgood.us/2019/06/19/sift-the-four-moves

Critical Thinking in Academic Research - Second Edition Copyright © 2022 by Cindy Gruwell and Robin Ewing is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Related topics

See all available workshops.

Short on time? Watch a video on:

- Finding information – 5:38

Have any questions?

This is the footer

- Article Databases

- Google Scholar

- Interlibrary Services

- Research Guides

- Staff Directory

- Study Rooms

- Citation Linker

- Digital Collections

- Digital Commons

- Reference Tools

- Special Collections

- All Resources

- Ask-A-Librarian

- Borrowing & Renewals

- Computing & Printing

- Copyright@Wayne

- Course Reserves

- Equipment Checkout

- Instruction

- Research Support

- Rooms & Spaces

- The Publishing House

- Technology Support

- All Services

- Arthur Neef Law Library

- Purdy/Kresge Library

- Reuther Library

- Shiffman Medical Library

- Undergraduate Library

- Accessibility

- Desktop Advertising

- Maps & Directions

- All Information

- Appointments

- WSU Login Academica, Canvas, Email, etc.

- My Library Account Renew Books, Request Material, etc.

- Make a Gift

- back to Wayne.edu

- Skip to Quicklinks

- Skip to Sitemap

- Skip to Main Navigation

- Skip to News

- Interlibrary Loan

Information

- {{guide_title}}

SIFT: Stop, Investigate, Find, Trace: What is SIFT?

What is sift.

- Investigate the Source

- Find Better Coverage

- Trace Claims, Quotes, and Media Back to Their Original Context

- Resources for Instructors

- SIFT Tutorial

SIFT is an evaluation strategy developed by digital literacy expert Michael Caulfield (Washington State University Vancouver) to help you judge whether or online content can be trusted for credible and reliable information. The SIFT strategy is quick, simple, and can be applied to various kinds of online content: social media posts, memes, statistics, videos, images, news articles, scholarly articles, etc.

SIFT stands for:

I NVESTIGATE THE SOURCE

F IND BETTER COVERAGE

T RACE CLAIMS, QUOTES, AND MEDIA BACK TO THEIR ORIGINAL CONTEXT

SIFT is an additional set of skills to build on “checklist” approaches to evaluating online content.

Some checklist questions you might ask yourself when initially arriving at a webpage:

- Does this webpage look professional?

- Are there spelling errors?

- Is it a .com or a .org?

- Is there scientific language?

- Does it use footnotes?

In today’s world, asking yourself these kinds of questions is no longer enough. Why?

- Anyone can easily design a professional looking webpage and use spellcheck

- .com or .org does not always reflect the credibility of the content

- Scientific language does not always reflect expertise or agenda of the content

- The inclusion of footnotes does not always reflect credibility of the content

SIFT: Evaluating Web Content

This video (4:27) provides a brief overview of SIFT.

Fakeout is an interactive game to test your evaluation skills on spotting fake news stories.

Click the link to play Fakeout

Further Reading

Article: Don't Go Down the Rabbit Hole

Article: In the age of fake news, here’s how schools are teaching kids to think like fact-checkers

Article: Here are all the ‘fake news’ sites to watch out for on Facebook

Article: Snopes’ Field Guide to Fake News Sites and Hoax Purveyors

Blog: Recognition is futile and also dangerous

Acknowledgement

Note: This SIFT method guide was adapted from Michael Caulfield's "Check, Please!" course. The canonical version of this course exists at http://lessons.checkplease.cc . The text and media of this site, where possible, is released into the CC-BY, and free for reuse and revision. We ask people copying this course to leave this note intact, so that students and teachers can find their way back to the original (periodically updated) version if necessary. We also ask librarians and reporters to consider linking to the canonical version.

As the authors of the original version have not reviewed any other copy's modifications, the text of any site not arrived at through the above link should not be sourced to the original authors.

- Next: Stop >>

- Last Updated: Mar 11, 2021 3:50 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.wayne.edu/sift

- Borrowing & Renewals

- Computing & Printing

- Rooms & Spaces

- Maps & Directions

- Make Appointment

- Last Updated: Jul 31, 2023 1:47 PM

- Clark College Libraries

- Research Guides

- Evaluating Information

- SIFT (The Four Moves)

Evaluating Information: SIFT (The Four Moves)

- A.S.A.P. and W5 for W3

- A.S.P.E.C.T

- Hoax or Real?

- Beyond the "About" Page

- Real News or Fake News?

Introduction to SIFT

Welcome to sift, an evaluation method designed by mike caulfield..

The SIFT method was created by Mike Caulfield . All SIFT information on this page is adapted from his materials with a CC BY 4.0 license.

Determining if resources are credible is challenging. Use the SIFT method to help you analyze information, especially news or other online media.

Remember, you can always Ask a Librarian for help with evaluating information.

Before you read the article, stop!

Before you share the video, stop!

Before you act on a strong emotional response to a headline, stop!

Ask yourself: Do I know this website? Do I know this information source? Do I know it's reputation?

Before moving forward, use the other three moves: I nvestigate the Source, F ind Better Coverage, and T race Claims, Quotes, and Media back to the Original Context.

I - Investigate the Source

- Use Google or Wikipedia to investigate a news organization or other resource.

- Hovering is another technique to learn more about who is sharing information, especially on social media platforms such as Twitter.

F - Find Better Coverage

- Look and see what other coverage is available on the same topic

- Keep track of trusted news sources

- Use fact-checking sites

- Do a reverse image search

T - Trace Claims, Quotes, and Media Back to the Original Context

- Click through to follow links to claims

- Open up the original reporting sources listed in a bibliography if present

- Look at the original context. Was the claim, quote, or media fairly represented?

Additional SIFT Resources

- Hapgood, Mike Caulfield's Blog This is Mike Caulfield's Blog where he explains SIFT in his own words.

- SIFTing Through the Pandemic Another Mike Caulfield creation, this blog focuses on using SIFT during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Web Literacy for Student Fact-Checkers This ebook by Mike Caulfield is freely available online under a CC BY 4.0 license

- Check, Please! Starter Course A free, five-lesson course on fact- and source-checking from Mike Caulfield

- << Previous: Real News or Fake News?

- URL: https://clark.libguides.com/evaluating-information

facebook twitter blog youtube maps

Information Evaluation: What is the SIFT Method?

- Scholarly vs. Popular

- Primary vs. Secondary

What is the SIFT Method?

- Move One: Stop

- Move Two: Investigate the Source

- Move Three: Find Better Coverage

- Move Four: Trace Claims, Quotes and Media to Their Original Context

- Fakeout! (interactive game)

- Bias vs. Agenda

- Fake News This link opens in a new window

- Audio/Visual Media

- Information Timeline

- Game: Fakeout!

The SIFT Method is a series of actions one can take in order to determine the validity and reliability of claims and sources on the web. Each letter in “SIFT” corresponds to one of the “Four Moves":

When practiced, SIFT reveals the necessary context to read, view, or listen effectively before reading an article or other information online.

We learn about the author, speaker, or publisher: What’s their expertise? Their agenda? Their record of fairness or accuracy? We check on claims: Are they broadly accepted? Rejected? Something in-between? We don’t take evidence at face value. Is it presented in its original context, or with a certain frame that changes its meaning for the reader or viewer?

Listen to Mike Caulfield, the man who created the SIFT Method, in the short video below (1:30) as he explains why developing our online evaluation skills are more important now than ever before:

Keep reading as we work our way through each of the Four Moves in detail. Click here to start with Move One, or, use the buttons at the bottom of this guide to move ahead.

Acknowledgement

The SIFT Method portion of this guide was adapted from "Check, Please!" (Caulfield). The canonical version of Check, Please! exists at http://lessons.checkplease.cc (CC-BY). As the authors of the original version have not reviewed any other copy's modifications, the text of any site not arrived at through the above link should not be sourced to the original authors.

- << Previous: The SIFT Method

- Next: Move One: Stop >>

- Last Updated: Mar 15, 2024 9:53 AM

- URL: https://lib.lavc.edu/information-evaluation

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

4.2: The SIFT Method

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 90211

- Walter D. Butler; Aloha Sargent; and Kelsey Smith

- Pasadena City College, Cabrillo College, and West Hills Community College

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Mike Caulfield, Washington State University digital literacy expert, has helpfully condensed key fact-checking strategies into a short list of four moves, or things to do to quickly make a decision about whether or not a source is worthy of your attention . It is referred to as the “SIFT” method:

When you initially encounter a source of information and start to read it— stop . Ask yourself whether you know and trust the author, publisher, publication, or website. If you don’t, use the other fact-checking moves that follow, to get a better sense of what you’re looking at. In other words, don’t read, share, or use the source in your research until you know what it is, and you can verify it is reliable.

This is a particularly important step, considering what we know about the attention economy —social media, news organizations, and other digital platforms purposely promote sensational, divisive, and outrage-inducing content that emotionally hijacks our attention in order to keep us “engaged” with their sites (clicking, liking, commenting, sharing). Stop and check your emotions before engaging!

Investigate the Source

You don’t have to do a three-hour investigation into a source before you engage with it. But if you’re reading a piece on economics, and the author is a Nobel prize-winning economist, that would be useful information. Likewise, if you’re watching a video on the many benefits of milk consumption, you would want to be aware if the video was produced by the dairy industry. This doesn’t mean the Nobel economist will always be right and that the dairy industry can’t ever be trusted. But knowing the expertise and agenda of the person who created the source is crucial to your interpretation of the information provided.

When investigating a source, fact-checkers read “laterally” across many websites, rather than digging deep (reading “vertically”) into the one source they are evaluating. That is, they don’t spend much time on the source itself, but instead they quickly get off the page and see what others have said about the source. They open up many tabs in their browser, piecing together different bits of information from across the web to get a better picture of the source they’re investigating.

Please watch the following short video [2:44] for a demonstration of this strategy. Pay particular attention to how Wikipedia can be used to quickly get useful information about publications, organizations, and authors.

A YouTube element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here: http://pb.libretexts.org/collegeresearch/?p=103

Note: Turn on closed captions with the “CC” button or use the text transcript if you prefer to read.

Find Better Coverage

What if the source you find is low-quality, or you can’t determine if it is reliable or not? Perhaps you don’t really care about the source—you care about the claim that source is making . You want to know if it is true or false. You want to know if it represents a consensus viewpoint, or if it is the subject of much disagreement. A common example of this is a meme you might encounter on social media. The random person or group who posted the meme may be less important than the quote or claim the meme makes.

Your best strategy in this case might actually be to find a better source altogether , to look for other coverage that includes trusted reporting or analysis on that same claim. Rather than relying on the source that you initially found, you can trade up for a higher quality source.

The point is that you’re not wedded to using that initial source. We have the internet! You can go out and find a better source, and invest your time there. Please watch this video [4:10] that demonstrates this strategy and notes how fact-checkers build a library of trusted sources they can rely on to provide better coverage.

Trace Claims, Quotes, and Media to the Original Context

Much of what we find on the internet has been stripped of context. Maybe there’s a video of a fight between two people with Person A as the aggressor. But what happened before that? What was clipped out of the video and what stayed in? Maybe there’s a picture that seems real but the caption could be misleading. Maybe a claim is made about a new medical treatment based on a research finding—but you’re not certain if the cited research paper actually said that. The people who re-report these stories either get things wrong by mistake, or, in some cases, they are intentionally misleading us.

In these cases you will want to trace the claim, quote, or media back to the source, so you can see it in its original context and get a sense of whether the version you saw was accurately presented. Please watch the following video [1:33] that discusses re-reporting vs. original reporting and demonstrates a quick tip: going “upstream” to find the original reporting source.

“ Online Verification Skills – Video 2: Investigate the Source .” YouTube , uploaded by CTRL-F, 29 June 2018.

“ Online Verification Skills – Video 3: Find the Original Source .” YouTube , uploaded by CTRL-F, 25 May 2018.

“ Online Verification Skills – Video 4: Look for Trusted Work .” YouTube , uploaded by CTRL-F, 25 May 2018.

SIFT text adapted from “ Check, Please! Starter Course ,” licensed under CC BY 4.0

SIFT text and graphics adapted from “ SIFT (The Four Moves) ” by Mike Caulfield, licensed under CC BY 4.0

- Library staff

- Librarian subject liaisons

- Mission and vision

- Policies and procedures

- Location and hours

- BOOKS & MEDIA

- Books and eBooks

- Streaming media

- Worldcat (Advanced Search)

- Summon (advanced search)

- GUIDES & TUTORIALS

- All research guides

- Guides by subject

- Guides by special topic

- Video tutorials

- Using library services (Rudisill Library)

- Academic services

- Library resources and services

- Using library services (Lineberger Library)

- Rudisill Library

- Asheville Library

- Lineberger Memorial Library

Service Alert

- Lenoir-Rhyne Libraries

Critical Thinking and Reasoning

- Misinformation

- Lateral Reading

SIFT is an evaluation strategy developed by digital literacy expert Michael Caulfield (Washington State University Vancouver) to help you judge whether online content can be trusted for credible and reliable information. The SIFT strategy can be applied to various kinds of online content: social media posts, memes, statistics, videos, images, news articles, scholarly articles, etc. It builds on “checklist” approaches to evaluating online content.

- << Previous: Lateral Reading

- Next: Checklists >>

- Last Updated: Mar 27, 2024 11:41 AM

- URL: https://libguides.lr.edu/critical_thinking

How to Evaluate Information Sources

- Fake News and Fact Checking

- Evaluating Research Articles

- Is it Scholarly (Peer-Reviewed) or Popular?

- Identify Bias

Need help? Ask a librarian

Courtesy of Mike Caulfield

Text Version

S - Stop

I - Investigate the source

F - Find better coverage

T - Trace claims, quotes and media to the original context

More on SIFT

Mike Caulfield's blog about critically evaluating pandemic-related news and information. This site teaches a four-step process to use with coronavirus-related information that will show you “the skills that will make a dramatic difference in your ability to sort fact from fiction on the web (and everything in between).

- << Previous: CRAAP Test

- Next: Fake News and Fact Checking >>

- Last Updated: Mar 26, 2024 1:51 PM

- URL: https://researchguides.njit.edu/evaluate

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

The process of evaluating your resources may seem overwhelming, but it doesn’t have to be. Academic books and journals usually present themselves as scholarly and may be easily assessed for their quality of information. But others, especially websites, social media, newspapers, and magazines are not the same and sorting truth from fiction can be very challenging.

Our solution gives you a list of things to do when looking at a source, and hooks each of those things to one or two highly effective evaluation techniques. We call the “things to do” moves and there are four of them S top, I nvestigate, F ind, and T rack.

Licenses and Attributions: SIFT (The Four Moves) Authored by Mike Caulfield. Located at: https://hapgood.us/2019/06/19/sift-the-four-moves

Critical Thinking in Academic Research Copyright © 2022 by Cindy Gruwell and Robin Ewing is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Ask a Librarian

Scla 102: transformative texts, critical thinking and communication ii: modern world.

- Getting started

- Searching the Libraries' Catalog and Databases

- Gathering Statistics and Data

- Incorporating Primary Sources

Why Evaluate Your Sources?

- Citing your sources

If you need any help as you are researching your topic, please visit the Ask a Librarian website. From here you can chat, email, text, or Tweet with a librarian.

Typical chat and text hours:

Monday-Thursday, 9 AM - 11 PM,

Friday, 9 AM - 5 PM,

Saturday, 1 PM - 5 PM

Sunday, 3 PM - 11 PM

As you are researching, you will need to determine if it is credible and relevant to your research assignment and the particular argument or claim you are trying to make. We call this process of determining the credibility and usefulness of a source "evaluating." There is no one perfect step-by-step process for evaluating sources. One useful framework for evaluating sources is:

In the Investigate step of SIFT, where you think about the source you are currently exploring, you can consider a couple of broad ideas:

- Authority: exploring the origins of a source to make sure the author(s) and publisher have requisite expertise to be credible on the topic.

- Accuracy: exploring a source for validity and completeness.

- Perspective or Objectivity: exploring a source to determine the purpose and perspective of the author, publisher, and source.

- << Previous: Incorporating Primary Sources

- Next: Citing your sources >>

- Last Edited: May 23, 2024 11:54 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.purdue.edu/scla102catalano

College & Research Libraries News ( C&RL News ) is the official newsmagazine and publication of record of the Association of College & Research Libraries, providing articles on the latest trends and practices affecting academic and research libraries.

C&RL News became an online-only publication beginning with the January 2022 issue.

C&RL News Reader Survey

Give us your feedback in the 2024 C&RL News reader survey ! The survey asks a series of questions today to gather your thoughts on the contents and presentation of the magazine and should only take approximately 5-7 minutes to complete. Thank you for taking the time to provide your feedback and suggestions for C&RL News , we greatly appreciate and value your input.

Allison I. Faix is instruction coordinator at Kimbel Library, Coastal Carolina University, email: [email protected] .

Amy F. Fyn is business librarian at Eastern Michigan University, email: [email protected] .

ALA JobLIST

Advertising Information

- Preparing great speeches: A 10-step approach (223742 views)

- The American Civil War: A collection of free online primary sources (204908 views)

- 2018 top trends in academic libraries: A review of the trends and issues affecting academic libraries in higher education (77859 views)

Perspectives on the Framework

Allison I. Faix and Amy F. Fyn

Six frames, four moves, one habit

Finding ACRL’s Framework within SIFT

Allison I. Faix is instruction coordinator at Kimbel Library, Coastal Carolina University, email: [email protected] . Amy F. Fyn is business librarian at Eastern Michigan University, email: [email protected] .

© 2023 Allison I. Faix and Amy F. Fyn

T he SIFT method of source evaluation, proposed in 2017 by educational technologist Mike Caulfield, was designed as a “practical approach to quick source and claim investigation.” 1 At this time, academic librarians (including us) had already been questioning the effectiveness of popular source evaluation methods, especially checklist-based ones. Checklists seem too cursory and lack the flexibility and nuance needed to fully address the complex nature of internet sources. 2 The number of librarian-proposed updates to checklist methods of source evaluation has accelerated in recent years, 3 while SIFT has also emerged as a popular evaluation method with librarians. 4

Because of SIFT’s popularity, and because we ourselves are using SIFT, we wanted to look closely at SIFT through the lens of the ACRL Framework for Information Literacy. We believe there is value in using concepts from the entire Framework to best teach source evaluation. 5 It is important to identify overlap and gaps between the SIFT method and the ACRL Framework. Where does SIFT align with the evaluation expectations expressed within the Framework? What may academic librarians need to pair with SIFT lessons to better teach source evaluation? To answer our questions, we mapped the six frames of the ACRL Framework to the four moves and one habit of SIFT. Here, we introduce each move of SIFT, then connect it with relevant parts of the Framework. We also note where the Framework addresses source evaluation differently or in a more extended way than SIFT does, and what that might mean for librarians using SIFT in their classrooms.

SIFT: Four moves and a habit

Stop, Investigate, Find Better Coverage, and Trace Claims (SIFT) are separate yet related moves that fact-checkers may use to evaluate web sources. Embedded within these moves is a strategy known as lateral reading, which involves going outside of a source being evaluated and finding what others say about its reputation. Caulfield published an early version of SIFT, originally called “Four Moves and a Habit,” in Web Literacy for Student Fact Checkers . This approach to examining web sources is intended to recontextualize a source by “reconstructing the necessary context to read, view, or listen to digital content effectively.” 6 The moves progressively delve deeper into a source, though not all sources will need the full treatment to determine the suitability of a source for a purpose. Caulfield updated and streamlined this into the SIFT method through a 2019 blog post and further refinements over time through lesson plans and other tools for teaching. 7 We used all these documentations of SIFT to draw the fullest picture of how SIFT works and is taught. We acknowledge that each move of SIFT, like each frame of the ACRL Framework, contains some overlap in concepts with the other moves.

The initial move in SIFT, Stop, directs “Don’t read or share media until you know what it is.” 8 To learn what you are looking at, pause and ask yourself what you already know. Are you familiar with the website or information source? What do you know about “the reputation of both the claim and the website”?Stop is also a reminder to keep an eye on your purpose. It gives permission to do a “quick and shallow” review of a source’s reputation for most situations unless the context of the research is for more academic or scientific purposes, in which case a deeper examination may be warranted. In Stop, students pause to decide whether they want to investigate their source further. If a fast evaluation doesn’t tell you enough for your purpose, you can continue to the next move.

The Stop move, though brief, connects to the frames Authority is Constructed and Contextual, Information Creation as a Process, Information has Value, Research as Inquiry, and Searching as Strategic Exploration. The first three frames acknowledge in varying ways that value (of information, of a source) changes based on context. 9 The Framework also addresses the need to keep a focus on your purpose, with both the Research as Inquiry and Searching as Strategic Exploration frame’s inclusion of determining and limiting the scope of an investigation. 10

Investigate the Source

If you aren’t familiar with a source or its reputation, Investigate the Source is the next move. Here, you start to answer the questions asked in Stop, seeking more information to understand the credentials, potential bias, and agenda of the authors, as well as the reputation of the authors and the source. Answering questions like, “Is the site or organization I am researching what I thought it was?” 11 is critical to investigation because SIFT emphasizes that “knowing the expertise and agenda of the source is crucial to your interpretation of what they say.” 12 This move also allows for context in its consideration of authority. Practical contextualized examples are found in Caulfield’s supplementary works. For instance, Caulfield notes that “a small local paper may be a great source for local news, but a lousy source for health advice or international politics.” 13 Caulfield also recommends using an investigative strategy called “Just add Wikipedia.” 14 In this version of lateral reading, students are asked to use Wikipedia to learn more about websites they found. Investigating who runs a website, why it exists, and its reputation helps determine the legitimacy of a site.

Two ACRL frames, Authority is Constructed and Contextual, along with Information Creation as a Process, are most relevant to this move. Authority is Constructed and Contextual states that “information resources reflect their creators’ expertise and credibility, and are evaluated based on the information need and the context in which the information will be used.” 15 Several knowledge practices from this frame address methods for evaluating authority, such as using relevant research tools and developing an understanding that authority can be based on many factors including subject expertise, social position, or personal experience. Librarians can help students imagine different kinds of expertise and experts depending on the context. Although this frame, by its very name, asks students to go further into analyzing the contextual nature of authority than the SIFT process does, both consider the importance of context in source evaluation.

The Information Creation as a Process frame notes the importance of additional aspects of investigating the quality of a source. This frame states that “elements that affect or reflect on the creation, such as a pre- or post-publication editing or review process, may be indicators of quality.” 16 However, the SIFT method does not ask students to look this deeply into a source. SIFT asks students to use lateral reading to determine more about the reputation of a source. During this move, students may encounter information about a source’s editorial processes, but they are not intentionally seeking that out. Even something as simple as identifying the type of source, be it a blog or an academic journal article preprint, may offer clues about the level of review the contents received.

This can be especially important at the beginning of a research project when students are judging how much (and what kind of) further research might be needed. Information Creation as Process emphasizes the importance of learning to “assess the fit between an information product’s creation process and a particular information need” and to “recognize that information may be perceived differently based on the format in which it is packaged.” 17 SIFT does not explicitly advocate for students to determine types of sources, so librarians may need to discuss this with students, especially because using specific types of sources is often required in academic work.

Find Better Coverage/Find Trusted Coverage

If students find a source with a claim they are interested in, but they are unconvinced of the trustworthiness of the source, they can search for a better source that makes a similar claim. In this move, students go beyond investigating a source to seek stronger or more trusted sources or to find general consensus about a topic or claim. Here they may also verify the accuracy of the claim or whether experts agree with it. In his original post about SIFT, Caulfield explains it like this: “You want to know if [a claim] is true or false. You want to know if it represents a consensus viewpoint, or if it is the subject of much disagreement.” 18 Gaining a sense of what experts in the field think about their topic helps students better judge if the source is an outlier to those expert views. Additional perspectives also help put sources into context. In both this move and the ACRL Framework, students are encouraged to develop an informed skepticism about the sources they locate and to strive to find the best possible sources for their research needs.

Finding better or trusted coverage connects with every ACRL frame. Assertions about the trustworthiness of a source align with the Authority is Constructed and Contextual frame’s focus on “creators’ expertise and credibility.” 19 The Information Creation as a Process and Information has Value frames are linked with the need to understand that the way information is created influences its credibility and value. The Research as Inquiry frame indicates that skilled researchers exhibit dispositions of “maintain[ing] an open mind and a critical stance” and “seek[ing] multiple perspectives during information gathering and assessment.” 20 Scholarship as Conversation also speaks of the need to understand that “a query may not have a single uncontested answer. Experts . . . seek out many perspectives.” 21 Librarians may want to discuss with students that there may not be a clear consensus among experts, and that is part of the ongoing academic conversation. Finally, the Searching as Strategic Exploration frame says that information-literate learners “realize that information sources vary greatly in content and format and have varying relevance and value.” 22 The Framework encourages students to fully explore the information available to them, rather than sticking with the first source they find. While SIFT focuses students’ attention on finding better sources, the Framework has much more to say about how to actually do this. Librarians can teach students search strategies to help them locate better sources.

Trace Claims

The Trace Claims move says to evaluate sources by following quotes, claims, or media back to their original context and to check if text, images, videos, or sound recordings have been altered from the original format. Especially with internet sources, it’s possible that a source has evolved from an original post or story into something that has been “altered so much that it presents a radically wrong version of an event or a piece of research.” 23 Finding the original source allows students to recontextualize information and determine if a source remained true to the context or was misrepresented. Reading quotations within their original context may help students understand why the authors chose to use those quotations, and if the authors understood the quotations in the same way. Each of these considerations make a difference in deciding if a source is trustworthy.

The need to trace claims is closely connected to multiple frames. Context is especially important in the Authority is Constructed and Contextual frame, which states learners should “ask relevant questions about origins, context, and suitability for the current information need.” 24 The Information has Value frame encourages respect for the original ideas of others, stressing that learners “value the skills, time and effort needed to produce knowledge.” 25 Scholarship as Conversation asserts that learners “critically evaluate contributions made by others in participatory information environments.” 26 This frame engages more deeply with the need to respect the work of others than SIFT does, primarily by showing how writing practices that value citing other experts enable scholars to have conversations with one another.

The affective dimensions of the researcher are considered within SIFT as the “habit” introduced in Web Strategies for Fact-Checkers (“Four moves and a habit”). 27 When a source provokes strong emotion, whether positive or negative, check in with your emotions to see if they are influencing your evaluation. Caulfield references research that describes how an emotional response to information can activate your confirmation bias, that “our normal inclination is to ignore verification needs when we react strongly to content.” 28 People often assume that information we agree with is correct and information we disagree with is incorrect. Students need to learn to override this tendency or at least examine it closely before using information.

One frame directly references effect, and this dimension is also addressed within each frame’s dispositions. Searching as Strategic Exploration acknowledges that “information searching is a contextualized, complex experience that affects, and is affected by, the cognitive, affective, and social dimensions of the searcher.” 30 Authority is Constructed and Contextual’s dispositions refer to managing bias, noting the need for qualities including open-mindedness, self-awareness, and recognition of the value of diversity in worldviews. These dispositions are reiterated throughout the framework. Awareness of these often-personal dimensions is important to both source evaluation and conducting research itself.

Both SIFT and the Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education are used by librarians to support source evaluation, the first as a strategy to teach to students, and the second as a set of underpinning concepts that supports the foundation of lesson plans and information literacy instruction as a whole. Looking at SIFT through the broadest lens possible, it’s clear that some frames are much more evident than others. The Framework’s concepts, practices, and dispositions that focus on evaluating sources rather than finding or creating them are more prevalent within SIFT. It’s worth noting that SIFT was developed as a quick way to evaluate internet sources, while academic librarians are teaching students to find and evaluate a wider variety of sources.

Overall, the SIFT method at least scratches the surface of all the ACRL frames, making SIFT a more robust method for teaching source evaluation than others we have seen. Librarians can incorporate concepts that are less prominent in SIFT, such as the importance of information-creation processes and developing good strategies for locating better sources—in other ways and at other moments—as we extend our instruction to help students not only evaluate but also use their sources well.

- Mike Caulfield, “About,” Hapgood, n.d., https://hapgood.us/about/ .

- Marc Meola, “Chucking the Checklist: A Contextual Approach to Teaching Undergraduates Web-Site Evaluation,” portal: Libraries and the Academy 4, no. 3 (2004): 331–44, https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2004.0055 .

- See Alaina C. Bull, Margy MacMillan, and Alison J. Head, “Dismantling the Evaluation Framework,” In the Library with the Lead Pipe (July 21, 2021), https://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2021/dismantling-evaluation/ ; Anthony Bernard Tardiff, “Have a CCOW: A CRAAP Alternative for the Internet Age,” Journal of Information Literacy 16, no. 1 (2022): 119; Grace Liu, “Moving up the Ladder of Source Assessment: Expanding the CRAAP Test with Critical Thinking and Metacognition,” College & Research Libraries News 82, no. 2 (2021): 75; and M. Sara Lowe, Katharine V. Macy, Emily Murphy, and Justin Kan, “Questioning CRAAP: A Comparison of Source Evaluation Methods with First-Year Undergraduate Students,” Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning 21, no. 3 (2021): 33.

- David Sye and Dana Statton Thompson, “Tools, Tests, and Checklists: The Evolution and Future of Source Evaluation Frameworks,” Journal of New Librarianship 8 (2023): 76.

- Allison Faix and Amy F. Fyn, “Framing Fake News: Misinformation and the ACRL Framework,” portal: Libraries and the Academy 20, no. 3 (2020): 495–508, https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2020.0027 .

- Mike Caulfield, “SIFT (The Four Moves),” Hapgood , June 19, 2019, https://hapgood.us/2019/06/19/sift-the-four-moves/ .

- Mike Caulfield, “Updated Resources for 2021,” in Web Literacy for Student Fact-Checkers . . . and Other People Who Care About Facts (Montreal: Pressbooks, 2017), https://pressbooks.pub/webliteracy/front-matter/updated-resources-for-2021/ .

- Caulfield, “SIFT (The Four Moves).”

- ACRL, “Framework.”

- ACRL, “Framework,” 18.

- Mike Caulfield, “Check, Please! Starter Course: Lesson Two: Investigate the Source,” Notion.so , n.d., https://checkpleasecc.notion.site/Lesson-Two-Investigate-the-Source-dc0ab0dc7c394df9bcab6ffdb4edf626 .

- Caulfield, “Check, Please!”

- Mike Caulfield, “Just Add Wikipedia,” Sifting through the Pandemic: Information Hygiene for the Covid-19 Pandemic (blog), February 17, 2020, https://infodemic.blog/2020/02/17/just-add-wikipedia/ .

- ACRL, “Framework,” 12.

- ACRL, “Framework,” 14.

- ACRL, “Framework,” 19.

- ACRL, “Framework,” 20.

- ACRL, “Framework,” 23.

- ACRL, “Framework,” 17.

- Mike Caulfield, “Building a Fact-Checking Habit by Checking Your Emotions,” in Web Literacy for Student Fact-Checkers . . . and Other People Who Care About Facts (Montreal: Pressbooks, 2017), https://webliteracy.pressbooks.com/ .

- Caulfield, Web Literacy, 3.

- ACRL, “Framework,” 22.

Article Views (Last 12 Months)

Contact ACRL for article usage statistics from 2010-April 2017.

Article Views (By Year/Month)

© 2024 Association of College and Research Libraries , a division of the American Library Association

Print ISSN: 0099-0086 | Online ISSN: 2150-6698

ALA Privacy Policy

ISSN: 2150-6698

The SIFT Method

Navigating digital information.

Now that we’re in our fact-checking frame of mind, let’s start thinking about why fact-checking is an important part of your daily information practices. Watch and consider the following video and then learn more fact-checking strategies used by experts!

SIFT Your sources

Just a reminder to practice our new fact-checking habit! Get an emotional response? Take a moment to stop, a sk yourself whether you know and trust the author, publisher, publication, or website. If you don’t, use the other fact-checking moves that follow, to get a better sense of what you’re looking at.

Investigate the Source

When investigating a source, fact-checkers read “laterally” across many websites. That is, they don’t spend much time on the source itself, but instead they quickly get off the page and see what others have said about the source. They open up many tabs in their browser, piecing together different bits of information from across the web to get a better picture of the source they’re investigating. You don’t have to do a three-hour investigation into a source before you engage with it. But if you’re reading a piece on economics, and the author is a Nobel prize-winning economist, that would be useful information. Likewise, if you’re watching a video on the many benefits of milk consumption, you would want to be aware if the video was produced by the dairy industry. This doesn’t mean the Nobel economist will always be right and that the dairy industry can’t ever be trusted. But knowing the expertise and agenda of the person who created the source is crucial to your interpretation of the information provided.

Watch and consider the following video to learn how to get a consensus on sources and how Wikipedia is helpful for this strategy.

Find Better Coverage

Your best strategy in this case might actually be to find a better source altogether , to look for other coverage that includes trusted reporting or analysis on that same claim. Rather than relying on the source that you initially found, you can trade up for a higher quality source. What if the source you find is low-quality, or you can’t determine if it is reliable or not? Perhaps you don’t really care about the source—you care about the claim that source is making. You want to know if it is true or false. You want to know if it represents a consensus viewpoint, or if it is the subject of much disagreement. A common example of this is a meme you might encounter on social media. The random person or group who posted the meme may be less important than the quote or claim the meme makes.

The point is that you’re not wedded to using that initial source. We have the internet! You can go out and find a better source, and invest your time there.

Watch and consider the following video demonstrating this strategy, noting how fact-checkers build a library of trusted sources they can rely on quickly.

Trace Claims, Quotes, and Media to the Original Context

Much of what we find on the internet has been stripped of context. Maybe there’s a video of a fight between two people with one person acting as the aggressor. But what happened before that? What was clipped out of the video and what stayed in? Maybe there’s a picture that seems real but the caption could be misleading. Maybe a claim is made about a new medical treatment based on a research finding—but you’re not certain if the cited research paper actually said that.

The people who re-report these stories either get things wrong by mistake, or, in some cases, they are intentionally misleading us. In these cases you will want to trace the claim, quote, or media back to the source, so you can see it in its original context and get a sense of whether the version you saw was accurately presented.

This chapter was adapted from the following:

Introduction to college research by walter d. butler, aloha sargent, and kelsey smith, licensed under a creative commons attribution 4.0 international license..

Introduction to Finding Information Copyright © by Kirsten Hostetler is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

A SIFT Lesson Plan: Critical Skills for Navigating Media

“Oh my goodness, have you seen all the political ads on the television recently?” said a colleague earlier this month. It’s an election year, but how are you making sense of what’s true and false? Many of us have to learn how to deal with persuasive text, which may include political propaganda. And many adults and students are dealing with media overwhelm.

The middle school Texas ELA TEKS emphasize critical thinking skills. But how do you teach that? Let’s take a look at one approach you might consider. That approach is Mike Caufield’s SIFT Method ( CC-BY 4.0 lic ense ). Before jumping into an overview of SIFT, let’s take a moment to review why it’s even necessary.

Media Overwhelm

If you can read, listen, or watch content, you are under continuous assault. Differing viewpoints and perspectives assail your senses. In fact, when you have so many points of view, you may lack an easy way to make your own selections. The sheer volume of content can force some to throw up their hands in anomie.

Did You Know?

Anomie is an old concept , dating back to Emile Durkheim’s 1897 work, “Suicide: A Study in Sociology.” You may, as I did, have first learned about it in high school sociology class. Anomie occurs when the norms and values of society are unclear. People become confused about how to behave. Social order is threatened and people feel unrestricted in their behavior.

Anomie is a lack of rules about interpreting content resulting from the media blizzard. It raises its head with media due to the effects of media overwhelm. This can have dire consequences for students:

The psychological and social effects of excessive exposure to media and information can lead to feelings of isolation or conformity .

Hyper-connectedness results in feelings of disconnection that can affect students ( source ). To assist students and staff, you might consider adopting a tool to sift through the fluff.

Introducing SIFT

A simple process, SIFT is an acronym that represents the following actions:

- Stop. Check your emotions. If you have an emotional response to content, you’ve been “hooked” already.

- Investigate the source. Where does the content originate? Who made it?

- Find better coverage. Check other reliable sources to verify.

- Trace claims, quotes, and media to the original context.

Each step in the process comes with a few moves and questions you can ask. You can find these outlined in the infographic below.

View | Get a Copy in Canva | Get PPTx or PDF

Using the SIFT approach (or SIFT Method) in a real-life situation is easy. Let’s give it a go.

Example Use of SIFT Method

“Hey, Miguel, did you hear the news? Our principal now expects us to write all our lesson plans by hand to prove they weren’t generated by AI.” said a teacher at a recent event. “It’s in response to a new policy that goes something like this,” she shared. Then she gave me a printout:

View full size | Get a Copy in Canva | Get PDF ( Adapted from Jason Horne’s “What do you tell teachers about AI? “ )

What might this analysis look like with the SIFT Approach in mind?

Applying the SIFT Method

Now that you know what SIFT is, let’s apply it quickly to a news item, “ Artificial Intelligence Helps Complete Beethoven’s Unfinished Symphony ” from DoGoNews. The analysis below relies on ChatGPT-generated content:

Looking for some additional sources of age-appropriate news? Here’s a short list:

View full-size | Get a copy in Canva or PDF

Now that you’ve seen it in action with age-appropriate content, let’s look at a lesson plan using the same example.

Lesson Plan Example

In the example below, you will see the following:

This lesson plan aims to teach 6th graders how to think in a critical manner. It also facilitates their understanding of how to assess online sources. This aligns to the relevant TEKS standards for English/Language Arts. The activities build on one another, solidifying the SIFT method’s learning goals. Accommodations appear to ensure all students can engage and gain from the lesson.

Here’s what a 60-minute lesson plan for sixth graders might look like:

In a world flooded with media, telling the truth from falsities is essential. Equip your students with a critical thinking approach, the SIFT method—stop, investigate the source, find better coverage, and trace claims back to their roots. It will assist them in sorting through the noise to evaluate media with a critical lens. This approach will guide you through the firehose of content and help you avoid the confusion and disconnection that too much information can cause.

Miguel Guhlin

Transforming teaching, learning and leadership through the strategic application of technology has been Miguel Guhlin’s motto. Learn more about his work online at blog.tcea.org , mguhlin.org , and mglead.org /mglead2.org. Catch him on Mastodon @[email protected] Areas of interest flow from his experiences as a district technology administrator, regional education specialist, and classroom educator in bilingual/ESL situations. Learn more about his credentials online at mguhlin.net.

Five Lesson Plan Ideas to Celebrate National Poetry Month

Texperts: the creation of a teacher ambassador program, you may also like, make “choose your own adventure” stories with google..., spark creativity in the classroom with story dice, digital reading tools for k-5 readers, five stages of k-12 ed tech adoption: part..., five lesson plan ideas to celebrate national poetry..., the middle school elar teks and free, editable..., seven ways audiobooks benefit struggling readers, four emoji kitchen activities for english language arts, examples for teaching with fake news and pseudoscience, the four reading comprehension strategies of collaborative strategic reading..., leave a comment cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

You've Made It This Far

Like what you're reading? Sign up to stay connected with us.

*By downloading, you are subscribing to our email list which includes our daily blog straight to your inbox and marketing emails. It can take up to 7 days for you to be added. You can change your preferences at any time.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

By subscribing, you will receive our daily blog, newsletter, and marketing emails.

The Research Hub

- Library Information & Research Help

- Getting Help With Technology

- Locating Library Materials

- My Library Account

- Identifying Concepts and Keywords

- Effective Searching Strategies

- Background Research

- AND, OR and NOT

- Scholarly, Popular, & Trade

- Google Scholar and the Deep Web

- Finding News Sources

- Get It! Interlibrary Loan

- Research & Scholarly Publication Cycle

- Primary & Secondary Sources

- SIFT: the four moves

- Critical Thinking Guide

- Organize Your Research

- Annotated Bibliography

Determining "good" information from "bad" can get tricky sometimes. One way to decide what's what is to ask a librarian for help, or you can use SIFT, a set of 4 'moves' .

SIFT stands for:

- I nvestigate the source.

- F ind better or other sources.

- T race back to the original source to see quotes in their original context.

The idea of SIFT comes from Mike Caulfield and is reused here under a Creative Commons license.

Here are some helpful websites:

- News Literacy Project NLP empowers educators to teach students the skills they need to be smart, active consumers of news and other information and engaged, informed participants in civic life. It also provides people of all ages with tools and resources that enable them to identify credible information and know what to trust, share and act on.

- SIFTing Through the Pandemic Mike Caulfield's blog about critically evaluating pandemic-related news and information. This site teaches a four-step process to use with coronavirus-related information that will show you “the skills that will make a dramatic difference in your ability to sort fact from fiction on the web (and everything in between).

- << Previous: Primary & Secondary Sources

- Next: Fake News >>

- Last Updated: May 13, 2024 10:21 AM

- URL: https://infoguides.southwestern.edu/hub

Mike Caulfield's latest web incarnation. Networked Learning, Open Education, and Online Digital Literacy

SIFT (The Four Moves)

How can students get better at sorting truth from fiction from everything in between? At applying their attention to the things that matter? At amplifying better treatments of issues, and avoiding clickbait?

Since 2017, we’ve been teaching students with something called the Four Moves.

Our solution is to give students and others a short list of things to do when looking at a source, and hook each of those things to one or two highly effective web techniques. We call the “things to do” moves and there are four of them:

The first move is the simplest. STOP reminds you of two things.

First, when you first hit a page or post and start to read it — STOP. Ask yourself whether you know the website or source of the information, and what the reputation of both the claim and the website is. If you don’t have that information, use the other moves to get a sense of what you’re looking at. Don’t read it or share media until you know what it is.

Second, after you begin to use the other moves it can be easy to go down a rabbit hole, going off on tangents only distantly related to your original task. If you feel yourself getting overwhelmed in your fact-checking efforts, STOP and take a second to remember your purpose. If you just want to repost, read an interesting story, or get a high-level explanation of a concept, it’s probably good enough to find out whether the publication is reputable. If you are doing deep research of your own, you may want to chase down individual claims in a newspaper article and independently verify them.

Please keep in mind that both sorts of investigations are equally useful. Quick and shallow investigations will form most of what we do on the web. We get quicker with the simple stuff in part so we can spend more time on the stuff that matters to us. But in either case, stopping periodically and reevaluating our reaction or search strategy is key.

Investigate the source

We’ll go into this move more on the next page. But idea here is that you want to know what you’re reading before you read it.

Now, you don’t have to do a Pulitzer prize-winning investigation into a source before you engage with it. But if you’re reading a piece on economics by a Nobel prize-winning economist, you should know that before you read it. Conversely, if you’re watching a video on the many benefits of milk consumption that was put out by the dairy industry, you want to know that as well.

This doesn’t mean the Nobel economist will always be right and that the dairy industry can’t be trusted. But knowing the expertise and agenda of the source is crucial to your interpretation of what they say. Taking sixty seconds to figure out where media is from before reading will help you decide if it is worth your time, and if it is, help you to better understand its significance and trustworthiness.

Find better coverage

Sometimes you don’t care about the particular article or video that reaches you. You care about the claim the article is making. You want to know if it is true or false. You want to know if it represents a consensus viewpoint, or if it is the subject of much disagreement.

In this case, your best strategy may be to ignore the source that reached you, and look for trusted reporting or analysis on the claim. If you get an article that says koalas have just been declared extinct from the Save the Koalas Foundation, your best bet might not be to investigate the source, but to go out and find the best source you can on this topic, or, just as importantly, to scan multiple sources and see what the expert consensus seems to be. In these cases we encourage you to “find other coverage” that better suits your needs — more trusted, more in-depth, or maybe just more varied. In lesson two we’ll show you some techniques to do this sort of thing very quickly.

Do you have to agree with the consensus once you find it? Absolutely not! But understanding the context and history of a claim will help you better evaluate it and form a starting point for future investigation.

Trace claims, quotes, and media back to the original context

Much of what we find on the internet has been stripped of context. Maybe there’s a video of a fight between two people with Person A as the aggressor. But what happened before that? What was clipped out of the video and what stayed in? Maybe there’s a picture that seems real but the caption could be misleading. Maybe a claim is made about a new medical treatment based on a research finding — but you’re not certain if the cited research paper really said that.

In these cases we’ll have you trace the claim, quote, or media back to the source, so you can see it in it’s original context and get a sense if the version you saw was accurately presented.

It’s about REcontextualizing

There’s a theme that runs through all of these moves: they are about reconstructing the necessary context to read, view, or listen to digital content effectively.

One piece of context is who the speaker or publisher is. What’s their expertise? What’s their agenda? What’s their record of fairness or accuracy? So we investigate the source. Just as when you hear a rumor you want to know who the source is before reacting, when you encounter something on the web you need the same sort of context.

When it comes to claims, a key piece of context includes whether they are broadly accepted or rejected or something in-between. By scanning for other coverage you can see what the expert consensus is on a claim, learn the history around it, and ultimately land on a better source.

Finally, when evidence is presented with a certain frame — whether a quote or a video or a scientific finding — sometimes it helps to reconstruct the original context in which the photo was taken or research claim was made. It can look quite different in context!

In some cases these techniques will show you claims are outright wrong, or that sources are legitimately “bad actors” who are trying to deceive you. But in the vast majority of cases they do something just as important: they reestablish the context that the web so often strips away, allowing for more fruitful engagement with all digital information.

To learn about SIFT in more detail, check out our free three hour online minicourse .

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

Share this:

mikecaulfield

Leave a comment Cancel reply

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

How it works

For Business

Join Mind Tools

Article • 8 min read

Critical Thinking

Developing the right mindset and skills.

By the Mind Tools Content Team

We make hundreds of decisions every day and, whether we realize it or not, we're all critical thinkers.

We use critical thinking each time we weigh up our options, prioritize our responsibilities, or think about the likely effects of our actions. It's a crucial skill that helps us to cut out misinformation and make wise decisions. The trouble is, we're not always very good at it!

In this article, we'll explore the key skills that you need to develop your critical thinking skills, and how to adopt a critical thinking mindset, so that you can make well-informed decisions.

What Is Critical Thinking?

Critical thinking is the discipline of rigorously and skillfully using information, experience, observation, and reasoning to guide your decisions, actions, and beliefs. You'll need to actively question every step of your thinking process to do it well.

Collecting, analyzing and evaluating information is an important skill in life, and a highly valued asset in the workplace. People who score highly in critical thinking assessments are also rated by their managers as having good problem-solving skills, creativity, strong decision-making skills, and good overall performance. [1]

Key Critical Thinking Skills

Critical thinkers possess a set of key characteristics which help them to question information and their own thinking. Focus on the following areas to develop your critical thinking skills:

Being willing and able to explore alternative approaches and experimental ideas is crucial. Can you think through "what if" scenarios, create plausible options, and test out your theories? If not, you'll tend to write off ideas and options too soon, so you may miss the best answer to your situation.

To nurture your curiosity, stay up to date with facts and trends. You'll overlook important information if you allow yourself to become "blinkered," so always be open to new information.

But don't stop there! Look for opposing views or evidence to challenge your information, and seek clarification when things are unclear. This will help you to reassess your beliefs and make a well-informed decision later. Read our article, Opening Closed Minds , for more ways to stay receptive.

Logical Thinking

You must be skilled at reasoning and extending logic to come up with plausible options or outcomes.

It's also important to emphasize logic over emotion. Emotion can be motivating but it can also lead you to take hasty and unwise action, so control your emotions and be cautious in your judgments. Know when a conclusion is "fact" and when it is not. "Could-be-true" conclusions are based on assumptions and must be tested further. Read our article, Logical Fallacies , for help with this.

Use creative problem solving to balance cold logic. By thinking outside of the box you can identify new possible outcomes by using pieces of information that you already have.

Self-Awareness

Many of the decisions we make in life are subtly informed by our values and beliefs. These influences are called cognitive biases and it can be difficult to identify them in ourselves because they're often subconscious.

Practicing self-awareness will allow you to reflect on the beliefs you have and the choices you make. You'll then be better equipped to challenge your own thinking and make improved, unbiased decisions.

One particularly useful tool for critical thinking is the Ladder of Inference . It allows you to test and validate your thinking process, rather than jumping to poorly supported conclusions.

Developing a Critical Thinking Mindset

Combine the above skills with the right mindset so that you can make better decisions and adopt more effective courses of action. You can develop your critical thinking mindset by following this process:

Gather Information

First, collect data, opinions and facts on the issue that you need to solve. Draw on what you already know, and turn to new sources of information to help inform your understanding. Consider what gaps there are in your knowledge and seek to fill them. And look for information that challenges your assumptions and beliefs.

Be sure to verify the authority and authenticity of your sources. Not everything you read is true! Use this checklist to ensure that your information is valid:

- Are your information sources trustworthy ? (For example, well-respected authors, trusted colleagues or peers, recognized industry publications, websites, blogs, etc.)

- Is the information you have gathered up to date ?

- Has the information received any direct criticism ?

- Does the information have any errors or inaccuracies ?

- Is there any evidence to support or corroborate the information you have gathered?

- Is the information you have gathered subjective or biased in any way? (For example, is it based on opinion, rather than fact? Is any of the information you have gathered designed to promote a particular service or organization?)

If any information appears to be irrelevant or invalid, don't include it in your decision making. But don't omit information just because you disagree with it, or your final decision will be flawed and bias.

Now observe the information you have gathered, and interpret it. What are the key findings and main takeaways? What does the evidence point to? Start to build one or two possible arguments based on what you have found.

You'll need to look for the details within the mass of information, so use your powers of observation to identify any patterns or similarities. You can then analyze and extend these trends to make sensible predictions about the future.

To help you to sift through the multiple ideas and theories, it can be useful to group and order items according to their characteristics. From here, you can compare and contrast the different items. And once you've determined how similar or different things are from one another, Paired Comparison Analysis can help you to analyze them.

The final step involves challenging the information and rationalizing its arguments.

Apply the laws of reason (induction, deduction, analogy) to judge an argument and determine its merits. To do this, it's essential that you can determine the significance and validity of an argument to put it in the correct perspective. Take a look at our article, Rational Thinking , for more information about how to do this.

Once you have considered all of the arguments and options rationally, you can finally make an informed decision.

Afterward, take time to reflect on what you have learned and what you found challenging. Step back from the detail of your decision or problem, and look at the bigger picture. Record what you've learned from your observations and experience.

Critical thinking involves rigorously and skilfully using information, experience, observation, and reasoning to guide your decisions, actions and beliefs. It's a useful skill in the workplace and in life.

You'll need to be curious and creative to explore alternative possibilities, but rational to apply logic, and self-aware to identify when your beliefs could affect your decisions or actions.

You can demonstrate a high level of critical thinking by validating your information, analyzing its meaning, and finally evaluating the argument.

Critical Thinking Infographic

See Critical Thinking represented in our infographic: An Elementary Guide to Critical Thinking .

You've accessed 1 of your 2 free resources.

Get unlimited access

Discover more content

Book Insights

Work Disrupted: Opportunity, Resilience, and Growth in the Accelerated Future of Work

Jeff Schwartz and Suzanne Riss

Zenger and Folkman's 10 Fatal Leadership Flaws

Avoiding Common Mistakes in Leadership

Add comment

Comments (1)

priyanka ghogare

Sign-up to our newsletter

Subscribing to the Mind Tools newsletter will keep you up-to-date with our latest updates and newest resources.

Subscribe now

Business Skills

Personal Development

Leadership and Management

Member Extras

Most Popular

Latest Updates

Pain Points Podcast - Presentations Pt 2

NEW! Pain Points - How Do I Decide?

Mind Tools Store

About Mind Tools Content

Discover something new today

Finding the Best Mix in Training Methods

Using Mediation To Resolve Conflict

Resolving conflicts peacefully with mediation

How Emotionally Intelligent Are You?

Boosting Your People Skills

Self-Assessment

What's Your Leadership Style?

Learn About the Strengths and Weaknesses of the Way You Like to Lead

Recommended for you

Developing personal accountability.

Taking Responsibility to Get Ahead

Business Operations and Process Management

Strategy Tools

Customer Service

Business Ethics and Values

Handling Information and Data

Project Management

Knowledge Management

Self-Development and Goal Setting

Time Management

Presentation Skills

Learning Skills

Career Skills

Communication Skills

Negotiation, Persuasion and Influence

Working With Others

Difficult Conversations

Creativity Tools

Self-Management

Work-Life Balance

Stress Management and Wellbeing

Coaching and Mentoring

Change Management

Team Management

Managing Conflict

Delegation and Empowerment

Performance Management

Leadership Skills

Developing Your Team

Talent Management

Problem Solving

Decision Making

Member Podcast

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The SIFT Method. The SIFT method is an evaluation strategy developed by digital literacy expert, Mike Caulfield, to help determine whether online content can be trusted for credible or reliable sources of information. All SIFT information on this page is adapted from his materials with a CC BY 4.0 license. Determining if resources are credible ...

17. The SIFT Method. Mike Caulfield, Washington State University digital literacy expert, has helpfully condensed key fact-checking strategies into a short list of four moves, or things to do to quickly make a decision about whether or not a source is worthy of your attention. It is referred to as the "SIFT" method: