Your web browser is outdated and may be insecure

The RCN recommends using an updated browser such as Microsoft Edge or Google Chrome

Non-medical prescribers

Types of nurse prescriber.

Nurses, Midwives, Pharmacists and other allied healthcare professionals (AHPs) who have completed an accredited prescribing course and registered their qualification with their regulatory body, are able to prescribe.

The two main types are:

- Community Practitioner Nurse Prescribers (CPNP)

These are nurses who have successfully completed a Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) Community Practitioner Nurse Prescribing course (also known as a v100 or v150 course) and are registered as a CPNP with the NMC. The majority of nurses who have done this course are district nurses and public health nurses (previously known as health visitors), community nurses and school nurses. They are qualified to prescribe only from the Nurse Prescribers Formulary (NPF) for Community Practitioners. This formulary contains appliances, dressings, pharmacy (P), general sales list (GSL) and thirteen prescription only medicines (POMs).

- Independent Prescribers (IP)

Independent prescribers are nurses who have successfully completed an NMC Independent Nurse Prescribing Course (also known as a v200 or v300 course) and are registered with the NMC as an IP. They are able to prescribe any medicine provided it is in their competency to do so. This includes medicines and products listed in the BNF, unlicensed medicines and all controlled drugs in schedules two - five.

Those who have successfully completed the supplementary part of the prescribing course are also able to prescribe against a clinical management plan. Supplementary prescribing is described by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) as:

"a voluntary partnership between an Independent Prescriber (IP-er) and a supplementary prescriber (SP-er)," (e.g. nurse, pharmacist) "to implement an agreed patient-specific clinical management plan (CMP) with the patient's agreement."

The RCN acknowledges that some nurse prescribers are registered midwives.

Nurse independent prescribers and controlled drugs: changes to the Misuse of Drugs Regulations

The Misuse of Drugs Regulations covers all of the UK except Northern Ireland. This legislation divides controlled drugs (CDs) into five schedules corresponding to their therapeutic usefulness and misuse potential.

On 23 April 2012 changes to these regulations allowed nurses and midwives who are qualified as nurse independent prescribers to prescribe all controlled drugs listed in schedules two-five where it is clinically appropriate and within their professional competence (except for cocaine, diamorphine and dipipanone for the treatment of addiction). Changes also allowed nurse independent prescribers to mix any controlled drugs listed in schedules two-five prior to administration with another medicine for patients who need drugs intravenously.

Amendments to the Misuse of Drugs Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2002 were introduced on 10 May 2012 to allow a nurse independent prescriber and a pharmacist independent prescriber to prescribe controlled drugs as described.

Pharmacists and Allied Healthcare Professionals

There are two types of prescribers:

- An independent prescriber is a practitioner, who is responsible and accountable for the assessment of patients with undiagnosed or diagnosed conditions and can make prescribing decisions to manage the clinical condition of the patient.

- A supplementary prescriber is a practitioner who prescribes within an agreed patient specific clinical management plan (CMP), agreed in partnership by a supplementary prescriber with a doctor or dentist.

The table below is a brief summary of what IPs and SPs can prescribe (this does not include CPNP).

In general, an IP can prescribe any medicine for any condition within their clinical competence, whilst a SP may prescribe any medicine within their clinical competence that is included in the patient specific CMP.

| Independent Prescriber (IP) | Supplementary Prescriber (SP) (Nurses, Midwives and Pharmacists only | |

| Controlled Drugs (CDs) | Yes - CDs Schedule 2 to 5, except diamorphine, dipipanone | Yes - CDs Schedule 2 to 5, except diamorphine, dipipanone or cocaine for treatment of addiction |

| Unlicensed medicines | Yes -provided they are competent and take responsibility for doing so. May vary for Nurse prescribers in Scotland see the | Yes - covered by the CMP |

| Off label/off-licence prescribing | Yes - should only be prescribed where it is best practice to do so and | Yes - covered by the CMP |

| Private prescribing | Yes - for any medicine within their competence | Yes - for any medicine covered by the CMP |

Nurse prescribers and RCN indemnity

Become a nurse prescriber, further information.

RCN resources

Medicines Management : RCN Library subject guide

From the NMC website:

The NMC Code

Standards of Proficiency for Nurse and Midwife Prescribers (pre-2019). Please note that from November 2021 the NMC accepted the Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s Prescribing Competency Framework as their standards of competency for prescribing practice. All approved prescribing programmes must meet the new standards by 1 September 2022.

Other resources:

Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA ) can provide information on legislation and medicines and medical devices

NICE Medicines and Prescribing Centre provides support for medicines and prescribing.

Country-specific guidance is also available at the following websites by searching for ‘nurse prescribing':

England: Department of Health

Northern Ireland: Department of Health

Scotland: NHS Scotland

Wales: Welsh Government

Read our advice on medicines management, immunisation, revalidation, practice standards and mental health.

See our A-Z of advice. These guides will help you answer many of your questions about work.

Page last updated - 29/12/2023

Your Spaces

- RCNi Profile

- Steward Portal

- RCN Foundation

- RCN Library

- RCN Starting Out

Work & Venue

- RCNi Nursing Jobs

- Work for the RCN

- RCN Working with us

Further Info

- Manage Cookie Preferences

- Modern slavery statement

- Accessibility

- Press office

Connect with us:

© 2024 Royal College of Nursing

Our systems are now restored following recent technical disruption, and we’re working hard to catch up on publishing. We apologise for the inconvenience caused. Find out more: https://www.cambridge.org/universitypress/about-us/news-and-blogs/cambridge-university-press-publishing-update-following-technical-disruption

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Independent and Supplementary Prescribing

- > Non-medical prescribing: an overview

Book contents

- Frontmatter

- List of contributors

- Foreword to the second edition

- Preface to the second edition

- 1 Non-medical prescribing: an overview

- 2 Non-medical prescribing in a multidisciplinary team context

- 3 Consultation skills and decision making

- 4 Legal aspects of independent and supplementary prescribing

- 5 Ethical issues in independent and supplementary prescribing

- 6 Psychology and sociology of prescribing

- 7 Applied pharmacology

- 8 Monitoring skills

- 9 Promoting concordance in prescribing interactions

- 10 Evidence-based prescribing

- 11 Extended/supplementary prescribing: a public health perspective

- 12 Calculation skills

- 13 Prescribing in practice: how it works

- 14 Minimising the risk of prescribing error

1 - Non-medical prescribing: an overview

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 10 January 2011

In 1986, recommendations were made for nurses to take on the role of prescribing. The Cumberlege report, Neighbourhood nursing: a focus for care (Department of Health and Social Security (DHSS) 1986), examined the care given to clients in their homes by district nurses (DNs) and health visitors (HVs). It was identified that some very complicated procedures had arisen around prescribing in the community and that nurses were wasting their time requesting prescriptions from the general practitioner (GP) for such items as wound dressings and ointments. The report suggested that patient care could be improved and resources used more effectively if community nurses were able to prescribe as part of their everyday nursing practice, from a limited list of items and simple agents agreed by the DHSS.

Following the publication of this report, the recommendations for prescribing and its implications were examined. An advisory group was set up by the Department of Health (DoH) to examine nurse prescribing (DoH 1989). Dr June Crown was the Chair of this group.

The following is taken from the Crown report:

Nurses in the community take a central role in caring for patients in their homes. Nurses are not, however, able to write prescriptions for the products that are needed for patient care, even when the nurse is effectively taking professional responsibility for some aspects of the management of the patient. However experienced or highly skilled in their own areas of practice, nurses must ask a doctor to write a prescription. It is well known that in practice a doctor often rubber stamps a prescribing decision taken by a nurse. […]

Access options

Save book to kindle.

To save this book to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service .

- Non-medical prescribing: an overview

- By Molly Courtenay , Matt Griffiths

- Edited by Molly Courtenay , University of Surrey , Matt Griffiths , University of the West of England, Bristol

- Foreword by June Crown

- Book: Independent and Supplementary Prescribing

- Online publication: 10 January 2011

- Chapter DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511861123.003

Save book to Dropbox

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save book to Google Drive

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

- Clinical articles

- CPD articles

- CPD Quizzes

- Expert advice

- Clinical placements

- Study skills

- Clinical skills

- University life

- Person-centred care

- Career advice

- Reflective accounts

- Practice-related feedback

- Patient view

- Revalidation articles

- Cancer Nursing Practice

- Emergency Nurse

- Learning Disability Practice

- Mental Health Practice

- Nurse Researcher

- Nursing Children and Young People

- Nursing Management

- Nursing Older People

- Nursing Standard

- Primary Health Care

- CPD webinars on-demand

- Nursing Live

- Nursing Careers and Jobs Fairs

- RCNi events calendar

- CPD quizzes

Preparing to Prescribe toolkit: becoming a non-medical prescriber

Lynne pearce posted 10 november 2020 - 01:00.

Reducing health inequalities by better access to hepatitis C virus testing and treatment

Type 2 diabetes: initiating non-insulin-based treatment in adults, sepsis treatment: answers to 10 questions could unlock breakthrough for outcomes, chimeric antigen receptor (car) t-cell therapy: an overview for nurses, 5 most read articles, the 10 ‘rights’ of drug administration: how do they help me practise safely, nurse pay: how do you make your band 5 salary stretch, clinical nurse educator: skills, experience and the pay for the role, record-keeping: how to avoid making serious mistakes or leaving gaps, taking on the nhs backlog: are you up for more overtime, other rcni websites.

- RCNi Learning

- RCNi Nursing Careers and Jobs Fairs

- RCNi Nursing Jobs

- RCNi Portfolio

BNF via NICE is only available in the UK

The NICE British National Formulary (BNF) site is only available to users in the UK (England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland).

If you are outside the UK, you can access BNF content by subscribing to Medicines Complete .

If you believe you are seeing this page in error, please contact us .

For students

- Current Students website

- Email web access

- Make a payment

- MyExeter (student app)

- Programme and module information

- Current staff website

- Room Bookings

- Finance Helpdesk

- IT Service Desk

- Staff profile support and guidance

Popular links

Accommodation

- Job vacancies

- Temporary workers

- Future Leaders & Innovators Graduate Scheme

New and returning students

- New students website

- Returning Students Guide

Wellbeing, Inclusion and Culture

- Wellbeing services for students

- Wellbeing services for staff

- Equality, Diversity and Inclusion

Postgraduate Taught

Practice Certificate in Independent and Supplementary Prescribing

- Postgraduate Taught home

- Healthcare and Medicine

| UCAS code | 1234 |

|---|---|

| Duration | 6 months part time |

| Entry year | 2025 |

| Campus | St Luke's Campus |

| Discipline | |

| Contact |

| Typical offer

| 2.2 Honours degree (or equivalent) in a relevant discipline. |

|---|---|

|

• Designed to help you achieve accreditation for annotation as an Independent or Supplementary Prescriber on the GPhC, NMC or HCPC registers*

• Blend of online learning supported by minimal face-to-face contact days with communication and clinical skills training within our Clinical Skills Resource Centre • Problem Based Learning (PBL) scenarios allow students to tailor their learning to their own needs and develop personal learning objectives. • Expert tutors and guest lecturers will be invited from a range of clinical and research backgrounds • Can be taken as a standalone module or the credit can be used towards the MSc Clinical Pharmacy programme, MSc Advanced Clinical Practice programme or the Advanced Clinical Practice Degree Apprenticeship

• Acquiring this qualification and Independent or Supplementary prescriber status will enable you to seek extended roles in clinical practice as a non-medical prescribing practitioner * Successful completion of an accredited Independent and Supplementary Prescribing course is not a guarantee of annotation on the GPhC, NMC or HCPC registers or of future employment as an Independent or Supplementary Prescriber

View 2024 Entry

Apply for Sept 2025 entry

Fast Track (current Exeter students)

Open days and visiting us

Get a prospectus

Programme Directors: Will Farmer and Dr Rob Daniels

Web: Enquire online

Phone: +44 (0)1392 72 72 72

The programme is supported by NHS England and Health Education England through the Pharmacy Integration Fund.

Top 10 in the UK for our world-leading and internationally excellent Clinical Medicine research

Based on 4* + 3* research in REF 2021

Our Public Health research is 11th in the UK for research power

Submitted to UoA2 Public Health, Health Services and Primary Care. REF 2021

Major capital investment in new buildings and state-of-the-art facilities

Accreditations

This course was accredited by the General Pharmaceutical Council in December 2018. Please see the GPhC accreditation reports for more information. It was also accredited by The Health and Care Professionals Council (HCPC) and Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) in March 2021.

Entry requirements

Normally a minimum 2.2 Honours degree (or equivalent) in a relevant discipline. A personal statement, detailing your reasons for seeking to undertake this subject, will be required.

Entry requirements vary by regulator. Please check you meet the specific requirements below:

GPhC/PSNI registered pharmacist with at least two years of appropriate patient-orientated experience in a UK hospital, community or primary care setting following qualification

Registered nurse (level 1), midwife or SCPHN with at least one years’ appropriate patient-orientated experience in a UK hospital, community or primary care setting following qualification

HCPC registered physiotherapist, therapeutic/diagnostic radiographer, podiatrist or dietitian, with at least three years post-qualification experience in the area in which you will be prescribing

HCPC (Paramedics)

Registered paramedic with at least five years since qualification, practising in your area of expertise for at least 12 months

Have completed post-qualification study at level 7 (Master’s level)

All applicants must: • Have the agreement of a designated prescribing practitioner (DPP), practice assessor (PA) or Practice Educator (PE) who is willing to supervise your training • Demonstrate experience and reflective professional practice • Have identified an intended area of prescribing practice • Have support from a line manager, employer or service commissioner • Be fit to practice in accordance with the requirements of your regulator

Please visit our international equivalency pages to enable you to see if your existing academic qualifications meet our entry requirements.

Application process

Please complete the Independent and Supplementary Prescribing Course Application form and the IP SP Educational Audit Tool form before applying online.

Applicants may be invited to undertake an informal interview as part of the application process. This will take the form of an individual meeting/telephone conversation with one of our academics.

How employers can support

Ensure your staff are prepared for future prescribing roles. To undertake this programme, applicants must have support from a line manager, employer or service provider.

Undertaking the Clinical Pharmacy or Advanced Clinical Practice Programmes?

If you are already on the MSc Clinical Pharmacy or Advanced Clinical Practice programmes and want to do Independent or Supplementary Prescribing as part of this, you will not need to apply to Independent Prescribing through the online application process. Instead, please complete the Independent and Supplementary Prescribing Course Application form (ACP)

If you are applying for the MSc Clinical Pharmacy or Advanced Clinical Practice programmes and wish to take the Independent or Supplementary prescribing course as part of this, you will need to need to apply for both the MSc programme and the prescribing course at the same time.

If you are an Advanced Clinical Practice degree apprenticeship applicant and intend to choose prescribing as your year two option, you will need to complete an application form for this module in addition to your apprenticeship application. The appropriate forms will be provided as part of the DA application process

Entry requirements for international students

Please visit our entry requirements section for equivalencies from your country and further information on English language requirements .

English language requirements

International students need to show they have the required level of English language to study this course. The required test scores for this course fall under Profile B2 . Please visit our English language requirements page to view the required test scores and equivalencies from your country.

Course content

This Independent and Supplementary Prescribing course is designed to help you achieve accreditation for annotation as an Independent or Supplementary Prescriber on the GPhC, NMC or HCPC registers. We aim to produce competent non-medical prescribers who can provide safe, effective and evidence-based prescribing to address the needs of patients in their area of practice.

Features include:

- Online learning supported by face-to-face contact days

- Problem Based Learning - patient case-based activities that reflect the challenges of current clinical practice

- Communication and clinical skills training within our Clinical Skills Resource Centre

- Supportive, enthusiastic and clinically active tutors

- Increase your professional expertise and status and enhance your career prospects

- Complete the course to obtain a Practice Certificate in Independent/Supplementary Prescribing (as appropriate to your profession)

- Can be taken as a standalone module or the credit can be used towards the MSc Clinical Pharmacy programme, MSc Advanced Clinical Practice programme or the Advanced Clinical Practice Degree Apprenticeship

Our Practice Certificate in Independent and Supplementary Prescribing is a six month part-time 45 Credit programme of study at National Qualification Framework (NQF) level 7. It is taught using a blended approach to learning incorporating taught sessions, clinical skills practice and case-based discussion along with the support of online resources and moderated activities on the University of Exeter’s electronic learning platforms. Expert tutors and guest lecturers will be invited from a range of clinical and research backgrounds. Credits gained on this programme can be used towards the MSc Clinical Pharmacy programme, MSc Advanced Clinical Practice programme or the Advanced Clinical Practice Degree Apprenticeship

Contact Days

View the draft timetable of contact days for Independent Prescribing 2024/25

Please note: this timetable is a draft and may be subject to change.

The last contact day and assessment deadline for the programme will be earlier than the actual end date of your registration with the University, to allow a period of time at the end of your active studies for further support and mitigation, if needed

The modules we outline here provide examples of what you can expect to learn on this degree course based on recent academic teaching. The precise modules available to you in future years may vary depending on staff availability and research interests, new topics of study, timetabling and student demand.

Supervised practice

The GPhC, NMC and HCPC all require that a trainee non-medical prescriber be supported and supervised by a prescribing practitioner who meets a series of experiential requirements. The different accrediting bodies give this role different titles: • GPhC - Designated Prescribing Practitioner (DPP) • NMC - Practice Assessor (PA) • HCPC - Practice Educator (PE).

The NMC require a trainee to have both a Practice Assessor and a Practice Supervisor. Practice Assessors assess and confirm the student’s achievement of practice learning for a placement; they will also work with the nominated academic assessor to make a recommendation for student progression. The Practice Supervisors’ role is to support and supervise nursing and midwifery students in the practice learning environment. All students must be supervised while learning in practice environments.

For the purposes of clarity, we will refer to the Designated Prescribing Practitioner (DPP) for all roles.

The aim of the DPP role is ‘to oversee, support and assess the competence of non-medical prescribing trainees, in collaboration with academic and workplace partners, during the period of learning in practice’ (RPS, 2019). A DPP directs and supervises the trainee’s period of learning in practice – a required element of independent prescribing qualifications. They will also be responsible for assessing whether the learning outcomes have been met and whether the trainee has acquired certain competencies.

Our trainee non-medical prescribers are required to complete 12 days or 90 hours in clinical practice. This time must be planned and aligned to the trainee’s learning needs and consist of activities relevant to the development of the trainee as an autonomous practitioner. The trainee will keep detailed logs of their activities and the DPP will need to provide supervision, feedback and oversight. The Designated Prescribing Practitioner has to assess the achievement of the learning outcomes and provide confirmation by signing the student’s practice-based log. At the end of the 90 hours in practice, the DPP is required to make a declaration that the trainee is suitable for annotation as an independent or supplementary prescriber (as appropriate to your profession).

Choosing your DPP

Your DPP must meet the Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s Competency framework for Designated Prescribing Practitioners (2019) . This allows for the supervision of trainee prescribers in practice by non-medical assessors as described below.

The DPP must: • Be a registered healthcare professional in Great Britain or Northern Ireland and in good standing with their professional regulator • Be registered with their regulator as a legally independent prescriber for at least the last three years, with no significant gaps in practice which would affect this three-year requirement.

Have at least three years’ active and recent prescribing practice, patient-facing clinical and diagnostic skill within the student’s chosen therapeutic area/scope of practice, with no significant gaps in practice which would affect this three-year requirement.

• Have the support of the employing organisation(s) or learning in practice setting(s) to act as a DPP who will provide supervision, support and opportunities to develop competence in prescribing practice for the pharmacist prescriber in training.

• Have experience of teaching, supervising and assessing other health care professionals in clinical practice.

• Have adequate indemnity insurance in place for their own professional and supervisory role as a DPP and ensure that all learning in practice settings have adequate indemnity insurance in place. Further requirements for this role can be found in section 7 of the Independent Prescribing Course Application Form Finally, your DPP must be able to personally commit to the time required to provide supervised practice which must be no less than 45 hours or 50% of your time in practice.

You will need to have agreed who will be your DPP before applying for this course. Your DPP must complete and sign Section 7 of the I IP/SP Course Application Form 2022-23 before you submit your application.

Practice Placement Quality Assurance

All applicants must ensure that the University of Exeter IP SP Educational Audit Tool has been completed within the last 12 months for the organisation providing their supervised practice placement. The audit should be completed by the education lead, prescribing lead or a senior manager for the organisation, in consultation with IP/SP module leads at the university. This audit is an essential part of our processes to quality assure your practice-based learning.

A copy of the completed audit tool must be submitted with your application, if we do not already hold one for your organisation. Your NMP or Prescribing Lead will be able to advise you if this is the case. Your application cannot be approved without a current copy of the audit tool.

2025/26 entry

- UK fees: £2,650

- International fees: £2,650

Fees can normally be paid by two termly instalments and may be paid online. You will also be required to pay a tuition fee deposit to secure your offer of a place, unless you qualify for exemption. For further information about paying fees see our Student Fees pages.

Scholarships

For more information on scholarships, please visit our scholarships and bursaries page.

*Selected programmes only. Please see the Terms and Conditions for each scheme for further details.

Find out more about tuition fees and funding »

Funding and scholarships

Uk government postgraduate loan scheme.

Postgraduate loans of up to £12,167 are now available for Masters degrees. Find out more about eligibility and how to apply .

There are various funding opportunities available including Global excellence scholarships. For more information visit our Masters funding page .

Scholarships

The University of Exeter is offering scholarships to the value of over £4 million for students starting with us in September 2021. Details of scholarships, including our Global Excellence scholarships for international fee paying students, can be found on our dedicated funding page .

University of Exeter Class of 2022 Progression Scholarship

We are pleased to offer graduating University of Exeter students completing their degree in Summer 2022 and progressing direct to a standalone taught Masters degree (eg MA; MSc; MRes; MFA) or research degree (eg MPhil/PhD) with us a scholarship towards the cost of their tuition fees. These awards are worth 10% of the first year tuition fee for students enrolling on a postgraduate taught or research programme of study in 2022/23, with the exception of the PGCE programme.

Teaching and research

Our purpose is to deliver transformative education that will help tackle health challenges of national and global importance.

Workshop days:

- Interactive patient-case discussions to develop your clinical reasoning

- Small group discussions to develop your future prescribing role

- Practical communication skills sessions

- Clinical examination training in specialist facilities

- Opportunities to reflect on your Supervised practice

- Academic tutor sessions to support your progress

E-learning material:

This comprises 3 units:

- Unit 1 - Prescribing Governance

- Unit 2 - Clinical skills for Prescribing

- Unit 3 - Prescribing Partnerships

Students also have access to extensive on-line resources used on our other clinical courses and University library facilities.

Learning is backed up with individual tutor support and peer group discussions.

Multi-modal Assessment

- Assessments are varied and reflect the responsibilities of the prescribing role

- Assessments include a clinical interest essay, MCQ test, observations of your clinical skills through OSCEs and submission of your Portfolio of Practice

You will already be a registered health professional in employment in a UK healthcare setting. Acquiring this qualification and Independent/Supplementary prescriber status will enable you to seek extended roles in clinical practice as an autonomous prescribing practitioner. In addition, the ability to tailor some of the assessments to an area of practice will enable you to further your clinical interests.

Careers support

All University of Exeter students have access to Career Zone, which gives access to a wealth of business contacts, support and training as well as the opportunity to meet potential employers at our regular Careers Fairs.

Related courses

Clinical pharmacy msc.

St Luke's Campus

Advanced Clinical Practice MSc

Master of public health (mph), environment and human health msc.

Penryn Campus

Healthcare Leadership and Management MSc

Clinical education msc.

View all Healthcare and Medicine courses

Why Exeter?

Student life

Our campuses

International students

Apply for a Masters

Immigration and visas

Tuition fees and funding

Connect with us

Information for:

- Current students

- New students

- Alumni and supporters

Quick links

Streatham Campus

Truro Campus

- Using our site

- Accessibility

- Freedom of Information

- Modern Slavery Act Statement

- Data Protection

- Copyright & disclaimer

- Cookie settings

Streatham Campus in Exeter

The majority of students are based at our Streatham Campus in Exeter. The campus is one of the most beautiful in the country and offers a unique environment in which to study, with lakes, parkland, woodland and gardens as well as modern and historical buildings.

Find out more about Streatham Campus.

St Luke's Campus in Exeter

Located on the eastern edge of the city centre, St Luke's is home to Sport and Health Sciences, the Medical School, the Academy of Nursing, the Department of Allied Health Professions, and PGCE students.

Find out more about St Luke's Campus.

Penryn Campus near Falmouth, Cornwall

Our Penryn Campus is located near Falmouth in Cornwall. It is consistently ranked highly for satisfaction: students report having a highly personal experience that is intellectually stretching but great fun, providing plenty of opportunities to quickly get to know everyone.

Find out more about Penryn Campus.

Module details

Independent/ Supplementary Prescribing (PgCert)

- Duration: 24 weeks

- Mode: Part time

Find out more about studying here as a postgraduate at our next Open Day .

Why study this course

This postgraduate certificate in non-medical prescribing will provide you with the knowledge and skills to qualify as an independent prescriber.

Accredited programme

Our course is accredited by the General Pharmaceutical Council (GPhC) and Health and Care Professions Council, the (HCPC).

Learning community

You will benefit from learning alongside a diverse group who are studying at various points in their career.

Student support

You will have academic support and be assigned a designated personal tutor throughout your studies with us.

High-quality teaching

You will be taught by experienced educational and clinical staff with considerable local, national and international reputations.

The programme will develop your ability to critically analyse and to hone your personal reflection skills, preparing you for lifelong professional development. It will provide the foundation for you to develop your practice, to enable you to provide a high professional standard of care, and be accountable for that care.

The programme will introduce you to the general principles of pharmacology relevant to prescribing practice, the professional, legal, and ethical frameworks relevant to Independent and Supplementary prescribing, and clinical governance / quality assurance aspects of prescribing.

These elements will be underpinned by evaluation of your own performance, and application of the prescribing principles to your own area of practice. It will also enable you to be aware of current developments within independent and supplementary prescribing in the UK. You will study in a multi-disciplinary setting along with a range of individuals from other professions including pharmacists, facilitating shared learning as recommended by the NMC/ HCPC.

Where you'll study

School of Healthcare Sciences

Our courses are designed to provide you with the knowledge and experience you need to embark on a professional healthcare career.

- Facilities Chevron right

- Research at the School of Healthcare Sciences Chevron right

- Academic staff Chevron right

- Telephone +44(0) 29 2068 7538

- Marker University Hospital of Wales, Heath Park, Cardiff, CF14 4XN

Admissions criteria

In order to be considered for an offer for this programme you will need to meet all of the entry requirements and must comply with the Professional, Statutory and Regulatory Body (Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) and Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC)) specific requirements for prescribing. Your application will not be progressed if the information and evidence listed is not provided.

With your online application you will need to provide:

- A copy of your professional registration number (NMC or HCPC) in order for us to confirm your current registration status.

- currently work in an area relevant to the programme

- have a minimum of one years’ full-time equivalent patient-orientated clinical experience

- are committed to Continuing Professional Development (CPD)

- Any evidence of previous study at Masters level.

- A copy of your certificate or transcript which shows you have undertaken a clinical assessment/diagnostics and evaluation module, or evidence that demonstrates you have developed these skills in clinical practice, such as a testimonial from a senior practitioner.

- A copy of your IELTS certificate with an overall score of 6.5 with 5.5 in all subskills, or evidence of an accepted equivalent. Please include the date of your expected test if this qualification is pending. If you have alternative acceptable evidence, such as an undergraduate degree studied in the UK, please supply this in place of an IELTS.

- Why have you selected this programme?

- What interests you about this programme?

- Any relevant experience related to the programme or module content.

- How you plan to use the qualification in your career.

- How you and your profession will benefit from your studies.

- Why you feel you should be given a place on the programme.

If you are self-funding your studies (if you work outside of a health board or an NHS Trust) you must also provide two additional references that specifically comment on your clinical and academic ability to undertake the programme.

Application Deadline

We allocate places on a first-come, first-served basis, so we recommend you apply as early as possible. Applications normally close at the end of July but may close sooner if all places are filled.

Selection process

Once you have submitted your application you will be sent a Learning Agreement and Statement of Support form, which you are required to complete and return to confirm you meet the criteria set out by the NMC and HCPC before we can consider your application. Once received, we will review your application and if you meet all of the entry requirements, including an assessment of suitability through the personal statement, we will make you an offer.

Additional information

You may apply for Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL) at level 6 or level 7 of up to 60 credits, of which only 30 credits can be at level 6. RPL is considered through mapping of learning outcomes of comparable modules. This complies with the NMC (2018) and HCPC (2019) prescribing standards.

If you intend to apply for recognition for prior learning, please supply copies of your credit transcripts with your application and provide further details in your personal statement.

Please contact the PGCert Independent Prescribing/ Supplementary Prescribing Programme Manager prior to applying to discuss RPL queries: [email protected]

Find out more about English language requirements .

Criminal convictions

A DBS (Disclosure Barring Service) certificate is required to undertake the following modules:

- HCT 356 Independent/Supplementary Prescribing (core)

- HCT 357 Independent/Supplementary Prescribing (core)

If you are currently subject to any licence condition or monitoring restriction that could affect your ability to successfully complete your studies, you will be required to disclose your criminal record. Conditions include, but are not limited to:

- access to computers or devices that can store images

- use of internet and communication tools/devices

- freedom of movement

- contact with people related to Cardiff University.

Course structure

The Postgraduate Certificate in Independent/ Supplementary Prescribing consists of 2 core modules (30 credits each).

The modules shown are an example of the typical curriculum and will be reviewed prior to the 2025/26 academic year. The final modules will be published by September 2025.

You will undertake both modules in year one.

Independent/ Supplementary Prescribing.

You will need to complete a minimum of 12 days (78 hours) of learning in practice in order to develop clinical assessment and prescribing skills, supported by a designated Practice Supervisor (PS). This is a PSRB requirement.

| Module title | Module code | Credits |

|---|---|---|

| HCT356 | 30 credits | |

| HCT357 | 30 credits |

The University is committed to providing a wide range of module options where possible, but please be aware that whilst every effort is made to offer choice this may be limited in certain circumstances. This is due to the fact that some modules have limited numbers of places available, which are allocated on a first-come, first-served basis, while others have minimum student numbers required before they will run, to ensure that an appropriate quality of education can be delivered; some modules require students to have already taken particular subjects, and others are core or required on the programme you are taking. Modules may also be limited due to timetable clashes, and although the University works to minimise disruption to choice, we advise you to seek advice from the relevant School on the module choices available.

Learning and assessment

How will i be taught.

In line with Cardiff University’s Digital Learning Strategy, the programme will be delivered using a blended learning approach. The programme will aim to provide a rich and engaging online experience, including a blend of synchronous and asynchronous learning activities alongside traditional face to face teaching and learning.

We will employ a range of learning and teaching approaches, from group and individual tutorials to student led seminars, dialogue, appreciative enquiry and problem- based learning, skills workshops, self-directed study, critical discussion /debate and expert led lectures. We employ e-learning via Virtual Learning Environments (VLE) that are specifically developed for Independent/ Supplementary Prescribing programmes.

Our programme and modules will facilitate effective inter-professional learning across a wide range of professions, and the sharing of differing professional perspectives and expertise. This experience will enhance your learning and development, and enable you to widen your professional network.

We appreciate that as registered practitioners, you will enter the programme with a wide range of skills, and some of you may hold advanced practitioner roles. Your clinical and experiential experiences are highly valued and will be used to enhance the learning process in terms of independent and shared learning.

We will encourage you to take an adult approach to learning at postgraduate degree level, which involves you taking responsibility for your own learning. We aim to prepare you for professional Independent/ Supplementary Prescribing practice.

How will I be assessed?

To meet professional and statutory regulatory body requirements, you will be assessed via the following methods:

Electronic Prescribing Portfolio:

Therapeutic Framework written Assignment,

Numeracy Test: (30 minutes)

Clinical logs reflective assignment:

Structured Clinical Assessment (SCA):

Therapeutics Class test (60 minutes):

How will I be supported?

To meet professional and statutory regulatory requirements (NMC and HCPC), a number of levels of support are offered:

Personal Tutor : You will be allocated a Personal tutor at the beginning of the programme who will provide educational and pastoral support and will:

• Maintain regular contact throughout the programme;

• Advise on the academic standards;

• Provide support and guidance with respect to learning;

• Provide feedback of progress and constructive comment on any aspects of learning which will

require further development;

• Be available for personal advice and support.

Academic Assessor : You will be allocated an Academic Assessor from the programme team for the duration of their programme; in addition to the Personal Tutor who will provide educational and pastoral support. The programme manager is responsible for ensuring that the allocation and monitoring of academic assessors is compliant the NMC standards for supervision and assessment of students, and that academic assessors are prepared for the role, as per faculty standards.

Responsibilities:

- academic assessors collate and confirm student achievement of proficiencies and programme outcomes in the academic environment for each part of the programme.

- academic assessors make and record objective, evidence based decisions on conduct, proficiency and achievement, and recommendations for progression, drawing on student records and other resources.

- academic assessors maintain current knowledge and expertise relevant for the proficiencies and programme outcomes they are assessing and confirming.

- the nominated academic assessor works in partnership with a nominated practice assessor to evaluate and recommend the student for progression, in line with programme standards and local and national policies.

- academic assessors have an understanding of the student’s learning and achievement in practice.

Strategy to Support Student Learning and Development as Prescribers

It is expected by the NMC/HCPC and University that regular meetings between you and your DPP should take place to enable a valid and constructive review of your progress and agreement about any further learning experiences which are required. The Practice Assessor (PA) should also meet with you to inform assessment of the your competence. Such meetings will involve direct observation of the your practice to enable a valid assessment of competence.

Meetings also need to take place between the PA and Practice Supervisor (PS) to inform the PA’s understanding of your learning and development in practice. The PA and academic assessor are also required to meet to explore the your progress with practice and academic learning to enable a constructive assessment of the your development of appropriate proficiencies and to allow the Academic Assessor to collate student outcomes from all elements of the programme.

The programme offers you the opportunity to develop and share ideas with health professionals, enabling you to learn and benefit from the experiences of others. Opportunity is given for discussion and exchange of ideas through seminars and tutorials.

We offer you the opportunity to become a student representative and shape future educational provision and advise on key elements of your learning.

All modules within the programme make extensive use of Cardiff University’s Virtual Learning Environment (VLE) Learning Central, on which you will find course materials, links to related materials and assessment exemplars. All lectures are recorded via electronic platforms, and are available for you to view throughout your programme.

The University offers a wide range of services and activities designed to support you. These include a student counselling service, a student advisory service, day care facilities, sport and exercise facilities, as well as campus information, library and IT services.

Further information about what the University can offer you can be found in the following link:

Student life - Study - Cardiff University

Our student app also allows you to access Cardiff University services and personalised information in one place in a simple and convenient way from a smartphone via the app store.

Features include:

- Campus maps

- Student library renewals, payments and available items

- Student timetable

- Find an available PC

- Access to help and student support

- Student news

- Receive important notifications

- Links to launch other University apps such as Outlook (for email) and Blackboard (for Learning Central).

What skills will I practise and develop?

The Learning Outcomes for this Programme describe what you will be able to do as a result of your study at Cardiff University. They will help you to understand what is expected of you.

The Learning Outcomes for this Programme can be found below:

Knowledge & Understanding:

On successful completion of the Programme you will be able to:

- Critically evaluate drug actions and sources of evidence-based information, advice and decision support in prescribing practice.

- Critically explore current available clinical, pharmacological and pharmaceutical knowledge relevant to your own area of practice.

- Demonstrate a critical evaluation of legal, ethical, professional and governance issues in their prescribing role.

Intellectual Skills:

- Demonstrate the appropriate application of a critical knowledge of drug actions in prescribing practice and the effective use of evidence-based decision support tools.

- Demonstrate a critical understanding and application of legislation relevant to the practice of non-medical prescribing.

- Demonstrate a critical and independent reflective approach to practice, analysing situations resulting in a coherent and sustained argument to enable service and practice improvement and professional development.

Professional Practical Skills:

- Critically evaluate approaches to the systematic and holistic assessment of patient need and the interpretation of diagnostic indicators to achieve a differential diagnosis.

- Demonstrate a strategic approach to effective collaboration with the multidisciplinary team involved in prescribing, supplying and administration of medicines.

- Demonstrate the critical application of effective strategies in negotiation and shared decision-making with patients and carers.

- Demonstrate a strategic application in practice of the framework of professional accountability and clinical governance in non-medical prescribing.

- Effectively employ appropriate communication/ education strategies to communicate and disseminate knowledge to the patient, families and client groups.

Transferable/Key Skills:

- Engage with information systems in order to analyse and interpret data to inform prescribing practice.

- Integrate theory with professional practice.

- Synthesise information/ data from a variety of sources.

- Critically appraise, synthesise and evaluate the evidence base related to Independent/ Supplementary Prescribing.

- Take responsibility for your individual personal and professional learning and development.

- Independent project manage and demonstrate time management skills.

- Work independently.

- Problem solve and reach realistic conclusions/ recommendations.

- Communicate ideas in a clear concise manner.

- Demonstrate digital literacy.

Tuition fees for 2025 entry

Your tuition fees and how you pay them will depend on your fee status. Your fee status could be home, island or overseas.

Learn how we decide your fee status

Fees for home status

Fees will be invoiced by module. Normally, invoices will be released shortly after enrolment for each individual module. For more information please refer to our tuition fees pages .

Students from the EU, EEA and Switzerland

If you are an EU, EEA or Swiss national, your tuition fees for 2025/26 be in line with the overseas fees for international students, unless you qualify for home fee status. UKCISA have provided information about Brexit and tuition fees .

Fees for island status

Learn more about the postgraduate fees for students from the Channel Islands or the Isle of Man .

Fees for overseas status

This course does not currently accept students from outside the UK/EU.

Additional costs

Cost of Disclosure and Barring Service (DBS) certificate.

Will I need any specific equipment to study this course/programme?

We will provide any equipment required.

Living costs

We’re based in one of the UK’s most affordable cities. Find out more about living costs in Cardiff .

Postgraduate loans

If you are starting your master’s degree in September 2024 or later, you may be able to apply for a postgraduate loan to support your study at Cardiff University.

Careers and placements

The non-medical prescribing pathway will provide you with a qualification that enable you to build on your existing role; improving the patient experience and reducing waiting times.

This programme will help you develop your career by undertaking more advanced roles with greater responsibilities for managing patient care.

The PgCert is also available as a pathway through the MSc in Advanced Practice; a programme designed for health, social care and related professionals in primary, secondary and tertiary settings who wish to advance their knowledge base, clinical, leadership and management skills. Students, irrespective of their clinical specialty, will become actively involved in the advancement of practice.

You will need to be employed and practising within a clinical environment within the United Kingdom to undertake this programme. You will be required to evidence clinical hours within your own clinical environment for the following modules:

- Independent/ Supplementary Prescribing modules require 78 hours associated practice within your prescribing area (core).

Open Day visits

Make an enquiry, international, other course options, independent/ supplementary prescribing (pg cert), discover more.

Search for your courses

Related searches: Healthcare , Nursing and midwifery , Healthcare sciences

HESA Data: Copyright Higher Education Statistics Agency Limited 2021. The Higher Education Statistics Agency Limited cannot accept responsibility for any inferences or conclusions derived by third parties from its data. Data is from the latest Graduate Outcomes Survey 2019/20, published by HESA in June 2022.

Module information

Postgraduate

Progress happens when extraordinary people come together to think about what matters most. Join a community where everyone is empowered to reach their potential and make a difference.

Postgraduate prospectus 2025

Download a copy of our prospectus, school and subject brochures, and other guides.

Order or download

Get in touch if you have a question about studying with us.

V300 Independent and Supplementary Prescribing for Registered Nurses

Accredited by University College Birmingham

Apply Ask us a question

- Postgraduate

- V300 Independent and Supplementary Prescribing Programme

Choose Award

90 hours of supervised prescribing practice (protected learning time)

September, February

Course breakdown

Entry requirements

Key information

- Placements and Careers

Small teaching group sizes ensures personalised learning with excellent engagement from our teaching team

Provides the invaluable opportunity to develop professionally and advance to senior or supervisory roles

Nurse prescribing ensures that patients can promptly access necessary medicines and treatments. This is especially crucial for individuals with chronic conditions who require ongoing care.

This 40-credit V300 programme for Registered Nurses will enable you to become a safe and competent independent and supplementary (non-medical) prescriber of medicines (from the British National Formulary).

You will learn to prescribe safely, appropriately and cost-effectively in your role as an NMC registered nurse (level 1), community specialist practitioner (SPQ) or specialist community public health nurse (SCPHN). Following successful completion of the programme, you will be eligible to be recorded as an independent/supplementary prescriber (V300) on the NMC register. It is an excellent opportunity to advance to senior roles, including an advanced nurse practitioner (ANP) or an advanced clinical practitioner (ACP).

Why should I choose this course?

- INDUSTRY APPROVED – The course been developed in partnership with our employer and practice partners, industry experts and experts-by-experience (service users), so the programme meets the current health and social care priorities for prescribing practice, as well as the NMC and Royal Pharmaceutical Society requirements

- CAREER PROGRESSION – Once your annotation is active, you can prescribe within your scope of practice within the approved formulary, in your current role, or search for new roles to progress your career

- FLEXIBLE LEARNING - The programme delivery is flexible, with online as well as face-to-face teaching sessions, simulated practice learning, self-directed study, e-learning and supervised practice

Our facilities

As part of this programme, you will have access to University College Birmingham’s specialist practical and academic learning environments in Moss House and McIntyre House. These include our Health Skills and Simulation Suite , complete with a purpose-built, six-bed hospital ward with simulation manikins, Anatomage table, integrated filming and audio equipment and a community care environment for simulated scenario sessions and ‘OSCE’ practice.

Independent and Supplementary Prescribing Module

40 credit Independent and Supplementary Prescribing Module (Level 6 or Level 7):

This module will facilitate your development of the knowledge and skills required for safe and effective prescribing from a legally specified UK formulary. Successful completion of all components of the module will lead to the achievement of a recordable prescribing qualification with the NMC. The subject areas you will study include assessing the patient and considering prescribing options, pharmacology for prescribing and de-prescribing, legal and regulatory frameworks, providing information, reaching shared decisions, monitoring, and reviewing treatments, prescribing safely, professionally and as part of a team and improving prescribing practice.

Module topics:

The syllabus for the teaching reflects the Royal Pharmaceutical Society's (2021) multiprofessional, competency framework for all prescribers’ and meets current regulatory requirements to register as an independent and/or supplementary prescriber. RPS (2021) A competency framework for all prescribers .

The competencies within the framework are presented as two domains and describe the knowledge, skill, behaviour, activity or outcome that prescribers should demonstrate:

Domain one - the consultation

This domain looks at the competencies that the prescriber should demonstrate during the consultation.

Domain two - prescribing governance

This domain focuses on the competencies that the prescriber should demonstrate with respect to prescribing governance.

In addition to the above, the module content includes:

• Anatomy and physiology • Person-centred communication, information provision and shared decision making • Legal, ethical and professional issues • Clinical pharmacology, including effects of co-morbidities • Evidence-based practice and issues of quality related to prescribing practice • Professional accountability and responsibility • Concordance strategies and overcoming clinical inertia • Monitoring and reviewing strategies • Prescribing in the team context • Prescribing in the public health context including health promotion • Models of consultation and motivational interviewing • Introductions to epidemiology • Service user partnership and collaboration • Consider prescribing options. • Prescribing safety • Improving prescribing practice through reflection

The modules listed above for this course are regularly reviewed to ensure they are up to date and informed by industry as well as the latest teaching methods. On occasion, we may need to make unexpected changes to modules – if this occurs, we will contact all offer holders as soon as possible.

To be considered for a place on the V300 Independent and Supplementary prescribing programme, you must provide evidence that you meet this entry criteria:

NMC registration NMC registrants: Registered Nurse (Level 1), midwife or SCPHN, must be registered with the NMC for a minimum of one year prior to applying for entry to the programme, usually with one year’s relevant experience in the clinical field in which they are intending to prescribe

Enhanced DBS Have a satisfactory enhanced disclosure clearance (DBS), dated within three years of the programme start date.

Academic ability Have the academic ability to study at the level required for the programme (i.e. academic Level 6 (degree level) or Level 7 (master’s level). Evidence of this is required on the application form.

Experience and skills Have the ability to practise safely and effectively as a Registered Nurse at a level of proficiency appropriate to the V300 programme and your intended area of prescribing practice in all of the following areas: > clinical/health assessment > diagnostics/care management > planning/evaluating care

Evidence of this must be supported by evidence on the application form.

Governance arrangements Your workplace must have appropriate clinical governance arrangements in place for you to practise as a Registered Nurse Independent/Supplementary Prescriber, including indemnity insurance arrangements

Protected learning time You are required to attend 24 study sessions/ complete online study, so you will need protected learning time approved by your manager, plus 90 hours of supervised prescriber practice, either in your workplace, or with other prescribers across different learning environments across the programme (26 weeks). These 90 hours must be protected by your employer. Approval of this must be provided by your employer, on the manager's reference form.

Registered Nurses working in independent practice

In addition to the entry requirements above, additional information is required for nurses working in independent practice:

Non NHS and self-employed applicants: If you are a self-funding applicant, or work independently, in private practice, or external to the NHS, then you will need to assure us that you will have protected learning time to meet the programme requirements at university, study and for the 90 hours of supervised prescriber practice. You must additionally provide information relating to entry criteria that are usually signed off by an NHS manager or non-medical prescribing lead and will be requested to provide the following information:

One professional reference that addresses the points identified above. The referee must be either an NMC/HCPC/GPhC registrant. They must have recent knowledge of your practice and they must be able to provide their professional registration number. They must confirm that you have the ability to practice safely and effectively as a Registered Nurse at a level of proficiency appropriate to the V300 programme and your intended area of prescribing practice in all of the following areas: > clinical/health assessment > diagnostics/care management > planning/evaluating care

On the application form , in the personal statement, you need to provide details of your anticipated prescribing role on completion of the programme, including conditions for which you intend to prescribe.

You need to provide details of the clinical governance process that will be employed to support the safety of your prescribing, for example indemnity insurance, health and safety legislation.

The budgetary arrangement for your prescribing, e.g. will you be using an NHS prescriber code or private prescription?

Practice Assessor (PA) and Practice Supervisor (PS) commitment

Practice Assessor (PA) and Practice Supervisor (PS) commitment:

Your PA and PS must submit commitment forms as part of the application process.

This form requires a declaration of their qualifications and competence as Registered Prescribers to be able to support, supervise and assess you within their role as either Practice Supervisor or Practice Assessor.

This agreement must be provided as part of the application form and assessed by the programme lead. Enrolment will not be complete until the programme team have verified you have the required support in place, and you will not be able to start the programme until we have assurance of this.

If your application is successful, applicants will receive an invitation to enrol. If more information is required, or an applicant requests ‘Recognition for Prior Learning’, then the applicant will attend a short interview with the programme lead to discuss their application.

At this stage, the applicant chooses how to pay the programme fees - several payment options are available.

Application process

There are three components to your application:

1. Your information

2. Manager’s approval

3. Practice Supervisor and Practice Assessor commitment

As an applicant, you must complete the application form as part of the admission process to provide evidence that you meet all of the criteria for entry onto the programme.

It can take up to 6 weeks to receive a formal offer, especially if your application form is incomplete, requires information or you do not have a DBS in place. It is best to apply early to avoid disappointment.

The completed application, with manager’s commendation, must be returned to [email protected] 6 weeks before the start of the programme for assessment.

Please ensure that all elements are completed or your application may be rejected.

If you work for a Trust or an employer with a non-medical prescribing lead, they MUST approve your application.

On your application, your non-medical prescribing lead / employer will need to provide supportive evidence that you have:

- at least one year’s experience working in a role with an identified clinical need for prescribing.

- the appropriate knowledge and experience in the area in which you intend to prescribe.

- protected time for the 90 hours of supervised prescribing practice.

- protected time for the 24 days of academic study time.

- the appropriate clinical supervision, clinical governance, and indemnity insurance to cover your future prescribing practice.

- a current Disclosure and Barring Services (DBS) check.

Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL)

The programme team will consider Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL) that is capable of being mapped to the RPS Competency Framework for all prescribers. You must request a consideration for this on the application form.

RPL can be applied up to 50% of the programme learning outcomes.

Evidence of prior knowledge, experience, programmes of study (for example V100/V150), study at the same academic level (Level 6 or Level 7) will require formal evidence, for example, transcripts, certificates or manager’s reference.

Employer-sponsored applications/apprenticeships/self funding applicants

Apprentices : If the V300 programme is taken as part of the MSc Adult Social Care Nursing or Homeless and Inclusion Health Nursing Apprenticeship programmes, then the levy fee arrangement through your employer will cover the cost of the V300 as the module is included within these programmes.

Self-funded students:

If the V300 is studied as a standalone programme, at level 6 or level 7, the cost is £2000 (2024-25 cost).

If the V300 programme is taken as part of a full master’s (MSc Adult Social Care Nursing or Homeless and Inclusion Health Nursing), the cost of the MSc is £9350 (2024-25 cost), which will include the V300.

Master’s students can apply for a postgraduate loan to cover the course cost of a full MSc programme. Funding for postgraduate study can be found at Gov.uk. The maximum available loan is £12,471 for the upcoming year (courses starting from 1 August 2024)

**This programme is not available to international students.**

Teaching and assessment

The programme is designed to have a 50:50 split between theory and practice. You will be taught general principles on study days through a variety of teaching methods, then relate your learning to your own practice area with the support of your Practice Supervisor and Practice Assessor.

The induction day, two practical sessions and ALL assessments at the end of each semester are held onsite at the University's Moss House campus (OSCE and 2 x written exams).

Assessment:

- 2-part online invigilated exam – 90 minutes pharmacology (80% pass mark) and 30 minutes prescribing calculations (100% pass mark)

- Practice Assessment Document (PAD) (90 hours of supervised practice) This is to record practice-based assessment and achievement of the practice competencies for independent and supplementary prescribing

- Portfolio containing 2 x 2000-word case-based assignments or reflections

Our teaching and assessment is underpinned by our Teaching, Learning and Assessment Strategy 2021-2024 .

Teaching methods include: • Online lectures • e-learning workbooks • Group discussions • Tutorials/academic assessor meetings • Interactive sessions, including quizzes • Problem-based learning case studies and scenarios • Practical prescribing sessions • Healthcare numeracy and prescriber calculation practice • Action learning sets/small group tutorials

90 hours of supervised prescriber practice (protected learning time) You are required to meet a minimum 90 hours of supervised prescriber practice to meet the Royal Pharmaceutical Society Competency Framework for Prescribers.

In partnership with your employer, you must identify a suitable Practice Assessor (PA).

A Practice Assessor is a Registered Healthcare Professional with a prescribing qualification and a minimum of three years’ recent prescribing experience in this role, for example, a doctor, nurse, pharmacist or other professionally registered, V300 trained independent prescriber.

In conjunction with your Practice Assessor, you must identify suitable Practice Supervisor(s) (PS) to support your practice learning.

Practice Supervisors should also be registered V300 Independent/Supplementary Prescribers (or equivalent) with at least one year of experience in this role.

In exceptional circumstances (for example, where there is limited access to non-medical prescribers), nurses can request from the programme lead that the same person acts as both Practice Assessor and Practice Supervisor ( https://www.nmc.org.uk/standards/standards-for-post-registration/standards-for-prescribers) .

Further details of supervision and assessment requirements can be found in the Royal Pharmaceutical Society Designated Prescribing Practitioner Framework: RPS English Competency Framework 3.pdf (rpharms.com)

Your Practice Assessor, along with your Academic Assessor, who will be a member of the university programme team, is responsible for signing you off as a competent and safe prescriber by the end of the programme.

Self-directed study It is recommended that you complete a further 12 days of self-directed study across the year in addition to the 24 advertised university study days, or six days if studying the 40-credit module only.

Self-directed is required for research for assessments, writing assignments and preparing for exams.

Timetable and schedule

The programme is a 40-credit module, taught and assessed across one year (September to March or February to August), with supervised learning in practice running alongside theory sessions. Each module starts in either September or February.

There are 24 taught study sessions in total. This is one study session per week including online learning/self-directed study plus supervised prescriber practice in the workplace up to a total of 90 hours.

Assessments will be in March and July and any required resits in August.

All sessions are mandatory attendance.

Unibuddy Community - meet other students on your course

Starting university is an exciting time, but we understand that it can sometimes feel a little daunting. To support you, you will be invited to join our Unibuddy Community , where you can meet other students who have applied for the same course at University College Birmingham, before you start studying here.

As soon as you have been made an offer, you will be sent an invitation email to complete your registration and join the Unibuddy Community. For more information, check out our Unibuddy Community page .

of graduate employers say relevant experience is essential to getting a job with them

Who we work with

A snapshot of some of the employers we have worked with:

- Cygnet Healthcare

- Practice Plus Group (Health in Justice)

Birmingham and Solihull Integrated Care System, and the Trusts and Organisations within this:

- University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust

- Birmingham and Solihull Mental Health Foundation Trust

- Birmingham Women's and Children's NHS Foundation Trust

- Royal Orthopaedic Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

- Birmingham Community Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust

- Birmingham and Solihull NHS Training Hub (GP Practice)

- Sandwell and West Birmingham NHS Trust (City, Sandwell, Rowley Regis)

- Change Grow Live

- Birmingham Council

- Solihull Metropolitan Borough Council

"University College Birmingham’s prescribing team are excited to be able to offer our Independent and Supplementary Prescribing programme to Registered Nurses. T he programme will ensure you develop personally and professionally and gain new knowledge, skills and behaviours that you can use within your scope of prescribing practice in your advanced and specialist practice roles."

Neelam Faree Programme lead for the V300 programme

Career opportunities

Note : Some roles below may require further study/training. The roles and salaries below are intended as a guide only.

Community specialist practitioner

Average Salary: £36,370

Advanced clinical practitioner

Average Salary: £50,173

Advanced nurse practitioner

£35,000-£50,000

We are here to support your career goals every step of the way.

Find out more

Antony's Story

Antony worked in the NHS for 27 years before joining the team at University College Birmingham as a lecturer.

Take the next step...

Apply now Book an open day

Other courses you may like

Adult social care nursing msc.

This MSc has been specifically written for Registered Adult Nurses working across community social care environments in recognition of the specialist knowledge and skills required for nurses to lead and manage services across diverse health and social care settings. If this sounds fascinating, this could be the perfect fit for you.

Homeless and Inclusion Health Nursing MSc

This website is intended for healthcare professionals

- Product Profiles

- { $refs.search.focus(); })" aria-controls="searchpanel" :aria-expanded="open" class="hidden lg:inline-flex justify-end text-gray-800 hover:text-primary py-2 px-4 lg:px-0 items-center text-base font-medium"> Search

Search menu

Armstrong A. Staff and patient views on nurse prescribing in the urgent-care setting. Nurse Prescribing. 2015; 13:(12)614-619 https://doi.org/10.12968/npre.2015.13.12.614

Courtenay M. An overview of developments in nurse prescribing in the UK. Nurs Stand. 2018; 33:(1)40-44 https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.2018.e11078

Courtenay M, Rowbotham S, Lim R Antibiotics for acute respiratory tract infections: a mixed-methods study of patient experiences of non-medical prescriber management. BMJ Open. 2017; 7:(3) https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013515

Courtenay M. Nurses can influence prescribing antibiotics. Primary Health Care. 2017a; 27:(6)14-14 https://doi.org/10.7748/phc.27.6.14.s19

Courtenay M, Khanfer R, Harries-Huntly G Overview of the uptake and implementation of non-medical prescribing in Wales: a national survey. BMJ Open. 2017b; 7:(9) https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015313

Courtenay M. The benefits of nurse prescribers in primary care diabetes services. Journal of Diabetes Nursing. 2015; 19:(10)386-387

Day M. UK doctors protest at extension to nurses' prescribing powers. BMJ. 2005; 331:(7526)

Report of the advisory group on nurse prescribing.London: DH; 1989

Nurse prescribing a guide for implementation.London

Review of prescribing, supply and administration of medicine: final report (Crown Report) London. 1998;

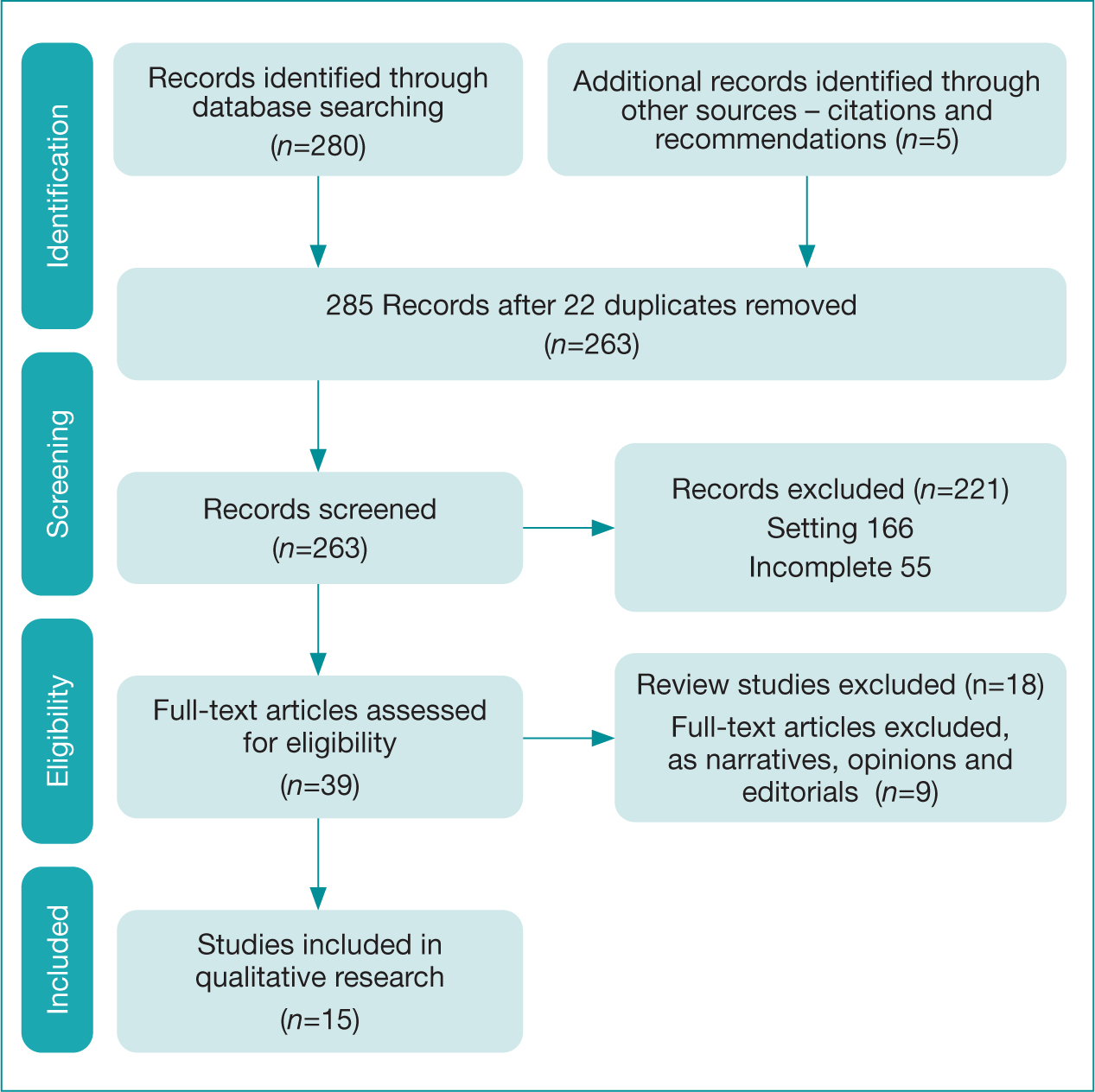

Facilitators and barriers to non-medical prescribing - A systematic review and thematic synthesis. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0196471

Hindi AMK, Seston EM, Bell D, Steinke D, Willis S, Schafheutle EI. Independent prescribing in primary care: A survey of patients', prescribers' and colleagues' perceptions and experiences. Health Soc Care Community. 2019; 27:(4)e459-e470 https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12746

Laurant M, Reeves D, Hermens R, Braspenning J, Grol R, Sibbald B. Substitution of doctors by nurses in primary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005:(2) https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001271.pub2

Maier CB. Nurse prescribing of medicines in 13 European countries. Hum Resour Health. 2019; 17:(1) https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-019-0429-6

NHS Health Education North West. Non-Medical Prescribing (NMP); An Economic Evaluation. 2015. http://www.i5health.com/NMP/NMPEconomicEvaluation.pdf (accessed 13 December 2022)

NHS England. Prescribing by paramedics. 2018. https://www.england.nhs.uk/ahp/medproject/paramedics/ (accessed 13 December 2022)