Facilitator Notes

How do we support struggling readers to become independent problem solvers?

- Growth Over Time: What can we learn from a struggling reader’s path towards independence?

- How do we use specific feedback to strengthen our struggling readers?

- How do we provide the appropriate amount of help to struggling readers?

How do we differentiate support to students during reading?

As children read, we work to provide them with the most appropriate support to accelerate their progress in developing independence. Prompts are calls to action: demonstrating a new approach to problem solving; helping children figure out how to use what they know or partially know in a new situation; reinforcing their actions through naming them. We pay close attention to using clear, consistent language to help children learn multiple ways to problem solve on their own. We teach children how to monitor and self-correct by cross-checking meaning, structure and visual (MSV) information. Eventually, they begin to use these sources of information in an integrated manner, quickly and efficiently, to read more difficult texts.

Video: Prompting for Independence ; Transcript , First Grade, Katie Babb, Emily Garrett, Maryann McBride

Video: MSV 1 ; Transcript , Emily Garrett, First Grade

Video: Using MSV 2 ; Transcript , Maryann McBride, First Grade Ashinique Owens, Second Grade

Growth Over Time: What lessons can we learn about helping a struggling reader build independence?

Children’s running records over time help us track their progress in developing independence. Recognizing the “red flag” of multiple appeals from a first grader at the beginning of the year in her intervention group, Reading Recovery/Intervention Teacher Katie Babb prompted consistently for strategic action to build student independence.

Supporting Documents: Growth Over Time Running Records

Video: Growth Over Time (Oct.-Jan.) ; Transcript , Running Records Katie Babb, First Grade

Video: Growth Over Time (Jan.-Mar.) ; Transcript , Running Records Katie Babb, First Grade

How do we use specific praise to strengthen our struggling readers?

The emphasis of specific praise is not on evaluation, but on naming for children the strategies they attempted or used successfully, to help them replicate or develop those actions. For a struggling reader, knowing what he/she has done well is a powerful tool.

Video: Using Students’ Strengths ; Transcript , Maryann McBride, First Grade

Video: Praising Attempts 1 ; Transcript , Maryann McBride, Katie Babb First Grade

Video: Praising Attempts 2 ; Transcript , Maryann McBride, First Grade

Video: Building Confidence ; Transcript , Maryann McBride, First Grade

How do we provide the appropriate amount of help to struggling readers?

Finding the “just right” amount of support to provide a struggling reader is similar to finding the “just right” book. Too much reinforces passivity and dependence on the teacher; too little leads to frustration and disengagement.

Video: Levels of Support 1 ; Transcript , Maryann McBride, CC Bates, Grade 1

Video: Levels of Support 2 ; Transcript , Elizabeth Arnold, Second Grade

Children reading at the same text level often have very different strengths and needs. One child may rely heavily on meaning and ignore visual, while another uses visual but doesn’t use meaning to confirm. As students move up levels, they have more options for strategies to use on their own. One child may need support in using analogies while another needs to work on seeing larger parts of words rather than proceeding letter by letter. Guided reading offers us the opportunity to prompt directly into the specific needs of each child, while all reading the same text.

Supporting Documents: Lesson Notes During Reading, Levels 16 and 20

Video: Differentiating Support 1 ; Transcript , Elizabeth Arnold, Second Grade

Video: Differentiating Support 2 ; Transcript , Elizabeth Arnold, Second Grade

- Summer Institute 2024

Guided reading

Guided reading is an instructional practice or approach where teachers support a small group of students to read a text independently.

Key elements of guided reading

- before reading discussion

- independent reading

- after reading discussion

The main goal of guided reading is to teach students to use strategies for reading that enable successful independent reading for meaning.

Why use guided reading

Guided reading is informed by Vygotsky’s (1978) Zone of Proximal Development and Bruner’s (1986) notion of scaffolding, informed by Vygotsky’s research. The practice of guided reading is based on the belief that the optimal learning for a reader occurs when they are assisted by an educator, or expert ‘other’, to read and understand a text with clear but limited guidance. Guided reading allows students to practise and consolidate effective reading strategies.

Vygotsky was particularly interested in the ways children were challenged and extended in their learning by adults. He argued that the most successful learning occurs when children are guided by adults towards learning things that they could not attempt on their own.

Vygotsky coined the phrase 'Zone of Proximal Development' to refer to the zone where teachers and students work as children move towards independence. This zone changes as teachers and students move past their present level of development towards new learning.

Guided reading helps students develop greater control over the reading process through the development of reading strategies which assist decoding and construct meaning. The teacher guides or ‘scaffolds’ their students as they read, talk and think their way through a text.

This guidance or ‘scaffolding’ has been described by Christie (2005) as a metaphor taken from the building industry. It refers to the way scaffolds sustain and support people who are constructing a building.

The scaffolds are withdrawn once the building has taken shape and is able to support itself independently (pp. 42-43). Similarly, the teacher places temporary supports around a text such as:

- frontloading new or technical vocabulary

- highlighting the language structures or features of a text

- focusing on a decoding strategy that will be useful when reading

- teaching fluency and/or

- promoting the different levels of comprehension – literal, inferential, evaluative.

Once the strategies have been practised and are internalised, the teacher withdraws the support (or scaffold) and the reader can experience reading success independently (Bruner, 1986, p.76).

Guided reading is a practice which promotes opportunities for the development of a self-extending system. When readers are guided to talk, think and read their way through a text, they build up a self-extending system, so that every time reading occurs, more learning about reading ensues (Ford and Opitz, 2011).

Teacher’s role in guided reading

Teachers select texts to match the needs of the group so that the students, with specific guidance, are supported to read sections or whole texts independently.

Students are organised into groups based on similar reading ability and/or similar learning needs determined through analysis of assessment tools such as reading conference notes and anecdotal records.

Every student has a copy of the same text and all students work individually, reading quietly or silently.

Understanding EAL/D students’ strengths and learning needs in the Reading and Viewing mode will help with appropriate text selection. Teachers consider a range of factors in selecting texts for EAL/D students including:

- content which connects to prior knowledge and experiences, including culturally familiar contexts, characters or settings

- content which introduces engaging and useful new knowledge, such as contemporary Australian settings and themes

- content which prepares students for future learning, e.g. reading a narrative about a penguin prior to a science topic about animal adaptations

- language at an accessible but challenging level ('just right' texts)

- availability of support resources such as audio versions or translations of the text

- texts with a distinctive beat, rhyming words or a combination of direct and indirect speech to assist with pronunciation and prosody

- the difficulty of the sentence structures or grammatical features in the selected text. Ideally, students read texts that have some challenge, but that they can read well enough to comprehend the text. This is not always feasible, particularly at the higher levels of primary school. If the text is difficult, the teacher could modify the text or focus the reading on a section before expecting them to read the whole text.

Students also need repeated exposure to new text structures and grammatical features to extend their language learning, such as texts with:

- different layouts and organisational features

- different sentence lengths

- simple, compound or complex sentences

- a wide range of verb tenses used

- a range of complex word groups (noun groups, verb groups, adjectival groups)

- direct and indirect speech

- passive voice, e.g. Wheat is harvested in early autumn, before being transported to silos.

- nominalisation (where a verb takes on the characteristics of a noun), e.g. The presentation of awards will take place at 8pm.

EAL/D students learn about the grammatical features as they arise in authentic texts. For example, learning about the form and function of passive sentences when reading an exposition text, and subsequently writing their own passive sentences.

All students in the class including EAL/D students will typically identify a learning goal for reading. Like all students, the learning needs of each EAL/D student will be different. Some goals may be related to the student’s prior experience with literacy practices, such as:

- ways to incorporate reading into daily life at home

- developing stamina to read for longer periods of time

- developing fluency to enable students to read longer texts with less effort.

Some goals may be related to the nature of students’ home language(s):

- learning to perceive, read and pronounce particular sounds that are not part of the home language, for example, in Korean there is no /f/ sound

- learning the direction of reading or the form of letters

- learning to recognise different word forms such as verb tense or plural if they are not part of the home language.

For more information on appropriate texts for EAL/D students, see: Languages and Multicultural Education Resource Centre

Major focuses for a teacher to consider in a guided reading lesson:

- activate prior knowledge of the topic

- encourage student predictions

- set the scene by briefly summarising the plot

- demonstrate the kind of questions readers ask about a text

- identify the pivotal pages in the text that contain the meaning and ‘walk’ through the students through them

- introduce any new vocabulary or literary language relevant to the text

- locate something missing in the text and match to letters and sounds

- clarify meaning

- bring to attention relevant text layout, punctuation, chapter headings, illustrations, index or glossary

- clearly articulate the learning intention (i.e. what reading strategy students will focus on to help them read the text)

- discuss the success criteria (e.g. you will know you have learnt to ….. by ………).

- ‘listen in’ to individual students

- observe the reader’s behaviours for evidence of strategy use

- assist a student to monitor meaning using phonic, semantic, contextual and grammatical knowledge

- confirm a student’s word problem-solving attempts and successes

- give timely and specific feedback to help students achieve the lesson focus

- make notes about the strategies individual students are using to inform future planning and student goal setting. See Teacher's role during reading ).

- talk about the text with the students

- invite personal responses such as asking students to make connections to themselves, other texts or world knowledge

- return to the text to clarify or identify a decoding teaching opportunity such as the revision of phoneme-grapheme correspondence blending or segmenting

- check a student understands what they have read by asking them to sequence, retell or summarise the text

- develop an understanding of an author’s intent and awareness of conflicting interpretations of text

- ask questions about the text or encourage students to ask questions of each other

- develop insights into characters, settings and themes

- focus on aspects of text organisation such as characteristics of a non-fiction text

- revisit the learning focus and encourage students to reflect on whether they achieved the success criteria.

The teacher selects a text for a guided reading group by matching it to the learning needs of the small group. The learning focus is identified through observation of the student reading, individual conference notes or anecdotal records.

Before reading a fictional text, the teacher can

- orientate students to the text. Discuss the title, illustrations, and blurb, or look at the titles of the chapters if reading a chaptered book

- activate students’ prior knowledge about language related to the text. This could involve asking students to label images or translate vocabulary. Students could do this independently, with same-language peers, family members or Multicultural Education Aides, if available

- use relevant artefacts or pictures to elicit language and knowledge from the students and encourage prediction and connections with similar texts.

Before reading a factual text, the teacher can

- support students to brainstorm and categorise words and phrases related to the topic

- provide a structured overview of the features of a selected text, for example, the main heading, sub headings, captions or diagrams

- support students to skim and scan to get an overview of the text or a specific piece of information

- support students to identify the text type, its purpose and language structures and features.

During reading the teacher can

- talk to EAL/D students about strategies they use when reading in their home language and encourage them to use them in reading English texts. Teachers can note these down and encourage other students to try them.

After reading the teacher can

- encourage EAL/D students to use their home language with a peer (if available) to discuss a response to a teacher prompt and then ask the students to share their ideas in English

- record student contributions as pictures (e.g. a story map) or in English so that all students can understand

- create practise tasks focusing on particular sentence structures from the text

- set review tasks in both English and home language. Home language tasks based on personal reflection can help students develop depth to their responses. English language tasks may emphasise learning how to use language from the text or the language of response

- ask students to practise reading the text aloud to a peer to practise fluency

- ask students to create a bilingual version of the text to share with their family or younger students in the school

- ask students to innovate on the text by changing the setting to a place in their home country and altering some or all of the necessary elements.

Inferring meaning

In this video the teacher leads an after reading discussion with a small group of students to check their comprehension of the text. The students re-read the text together. Prior to this session the children have had the opportunity to read the text independently and work with the teacher individually at their point of need.

Point of view

In this video, the teacher leads a guided reading lesson on point of view, with a group of Level 3 students.

Text selection

The teacher selects a text for a guided reading group by matching it to the learning needs of the small group. The learning focus is identified through:

- observation of the student/s reading

- individual conference notes

- or anecdotal records.

The text chosen for the small group instruction will depend on the teaching purpose. For example, if the purpose is to:

- demonstrate directionality - the teacher will ensure that the text has a return sweep

- predict using the title and illustrations - the text chosen must support this

- make inferences - a text where students can use their background knowledge of a topic in conjunction with identifiable text clues to support inference making.

Text selection should include a range of:

- texts of varying length and

- texts that span different topics.

It is important that the teacher reads the text before the guided reading session to identify the gist of the text, key vocabulary and text organisation. A learning focus for the guided reading session must be determined before the session. It is recommended that teachers prepare and document their thinking in their weekly planning so that the teaching can be made explicit for their students as illustrated in the examples in the information below.

Jessie, Rose, Van, Mohamed, Rachel, Candan

Tadpoles and Frogs, Author Jenny Feely, Program AlphaKids published by Eleanor Curtain Publishing Pty Ltd. ©EC Licensing Pty Ltd. (Level 5)

Learning Intention

We are learning to read with phrasing and fluency.

Success criteria

I can use the grouped words on each line of text to help me read with phrasing.

Phrasing helps the reader to understand the text through the grouping of words into meaningful chunks.

An example of guided reading planning and thinking recorded in a teacher’s weekly program (See Guided Reading Lesson: Reading with phrasing and fluency ).

Mustafa, Dylan, Rosita, Lillian, Cedra

The Merry Go Round – PM Red, Beverley Randell, Illustrations Elspeth Lacey ©1993. Reproduced with the permission of Cengage Learning Australia. (Level 3)

Learning intention

We are learning to answer inferential questions.

I can use text clues and background information to help me answer an inferential question.

Questions as prompts

Why has the author used bold writing? (Text clue) Can you look at Nick’s body language on page11? Page 16? What do you notice? (Text clues) Why does Nick choose to ride up on the horse rather than the car or plane? (Background information on siblings, family dynamics and stereotypes about gender choices).

An example of the scaffolding required to assist early readers to answer an inferential question. This planning is recorded in the teacher’s weekly program ( See Guided Reading Lesson: Literal and Inferential Comprehension ).

- an example of guided reading planning and thinking recorded in a teacher’s weekly program, see Guided Reading Lesson: Reading with phrasing and fluency)

- questions to check for meaning or critical thinking should also be prepared in advance to ensure the teaching is targeted and appropriate

- an example of the scaffolding required to assist early readers to answer an inferential question. This planning is recorded in the teacher’s weekly program.

It's important to choose a range of text types so that students’ reading experiences are not restricted.

Quality literature

Quality literature is highly motivating to both students and teachers. Students prefer to learn with these texts and given the opportunity will choose these texts over traditional ‘readers’ (McCarthey, Hoffman & Galda, 1999, p.51).

Research suggests the quality and range of books to which students are exposed to such as:

- electronic texts

- decodable texts

- student/teacher published work

- picture books

- information texts

- newspaper articles.

Students need to have access in the classroom to the full range of genres we want them to comprehend (Duke, Pearson, Strachan & Billman, 2011, p. 59). A variety of authentic text types as well as decodable texts addressing the students current reading need and the identified instructional purpose, need to be to be read and explicitly taught.

When selecting texts for teaching purposes include: levels of text difficulty and text characteristics such as:

- the degree of detail and complexity and familiarity of the concepts

- the support provided by the illustrations

- the complexity of the sentence structure and vocabulary

- the size and placement of the text

- students’ reading behaviours

- students’ interests and experiences including home literacies and sociocultural practices

- texts that promote engagement and enjoyment.

For ideas about selecting literature for EAL/D learners, see: Literature

Teacher's role during reading

During the reading stage, it is helpful for the teacher to keep anecdotal records on what strategies their students are using independently or with some assistance. Comments are usually linked to the learning focus but can also include an insightful moment or learning gap.

- finger tracking text

- uses some expression

- not pausing at punctuation

- some phrasing but still some word by word.

- reading sounds smooth.

- reads with expression

- re-reads for fluency.

- uses pictures to help decoding

- word by word reading

- better after some modelling of phrasing.

- tracks text with her eyes

- groups words based on text layout

- pauses at full stops.

- recognises commas and pauses briefly when reading clauses

- reads with expression.

Explicit teaching and responses

There are a number of points during the guided reading session where the teacher has an opportunity to provide feedback to students, individually or as a small group. To execute this successfully, teachers must be aware of the prompts and feedback they give.

Specific and focused feedback will ensure that students are receiving targeted strategies about what they need for future reading successes, see Guided Reading: Text Selection ; Guided Reading: Teacher’s Role .

- I really liked the way you grouped those words together to make your reading sound phrased. Did it help you understand what you read? (using meaning and visual or print information)

- Can you go back and reread this sentence? I want you to look carefully at the whole word here (the beginning, middle and end). What do you notice? (using vis ual or print information )

- As this is a long word, can you break it up into syllables to try and work it out? Show me where you would make the breaks. ( using vis ual or print information )

- It is important to pause at punctuation to help you understand the text. Can you go back and reread this page? This time I want you to concentrate on pausing at the full stops and commas ( using vis ual or print information and meaning )

- Look at the word closely. I can see it starts with a digraph you know. What sound does it make? Does that help you work out the word? ( using vis ual or print information, using phonic knowledge and skills ).

- This page is written in past tense. What morpheme would you expect to see on the end of verbs? Can you check? ( using vis ual and structural or grammatical information )

- Did what you read make sense? When you read something that does not make sense, you need to go back and reread, looking carefully at the words and letters to decode a word that does make sense ( using vis ual or print information and meaning ).

Specific feedback for EAL/D students may involve and build on transferable skills and knowledge they gained from reading in another language.

- I can see you were thinking carefully about the meaning of that word. What information from the book did you use to help you work out the meaning?

- Do you know this word in your home language? Let’s look it up in the bilingual dictionary to see what it means.

Reading independently

Independent reading promotes active problem solving and higher-order cognitive processes (Krashen, 2004). It is these processes which equip each student to read increasingly more complex texts over time; “resulting in better reading comprehension, writing style, vocabulary, spelling and grammatical development” (Krashen, 2004, p. 17).

It is important to note that guided reading is not the same as round robin reading. When students are reading during the independent reading stage, all children must have a copy of the text and individually read the whole text or a meaningful segment of a text (e.g. a chapter) quietly aloud to themselves while the teacher listens and observes individual students reading.

Students also have an important role in guided reading as the teacher supports them to practise and further explore important reading strategies.

- engage in a conversation about the new text

- make predictions based on title, front cover, illustrations, text layout

- activate their prior knowledge (what do they already know about the topic? what vocabulary would they expect to see?)

- ask questions

- locate new vocabulary/literary language in text

- articulate new vocabulary and match to letters/sounds

- articulate learning intention and discuss success criteria.

- read the whole text or section of text to themselves

- use concepts of print to assist their reading

- use pictures and/or diagrams to assist with developing meaning

- problem solve using the sources of information - the use of meaning, (does it make sense?) structure (can we say it that way?) and visual information (sounds, letters, words) on extended text (Department of Education, 1997)

- recognise high frequency words

- recognise and use new vocabulary introduced in the before reading discussion segment

- use text user skills to help read different types of text

- read aloud with fluency when the teacher ‘listens in’

- read the text more than once to establish meaning or fluency

- read the text a second or third time with a partner.

- be prepared to talk about the text

- discuss the problem solving strategies they used to monitor their reading

- revisit the text to further problem solve as guided by the teacher

- compare text outcomes to earlier predictions

- ask and answer questions about the text from the teacher and group members

- summarise or synthesise information

- discuss the author’s purpose

- think critically about a text

- make connections between the text and self, text to text and text to world.

Before reading the student can:

- activate their home language knowledge. What home language words related to this topic do they know?

During reading the student can:

- refer to vocabulary charts or glossaries in the classroom to help them recognise and recall the meaning of words learnt before reading the text

- use home language resources to help them understand words in the text. For example, translated word charts, bilingual dictionaries, same-language peers or family members.

After reading the student can:

- summarise the text using a range of meaning-making systems including English, home language and images.

Peer observation of guided reading practice (for teachers)

Providing opportunities for teachers to learn about teaching practices, sharing of evidence-based methods and finding out what is working and for whom, all contribute to developing a culture that will make a difference to student outcomes (Hattie, 2009, pp. 241-242).

When there has been dedicated and strategic work by a Principal and the leadership team to set learning goals and targeted focuses, teachers have clear direction about what to expect and how to go about successfully implementing core teaching and learning practices.

One way to monitor the growth of teacher capacity and whether new learning has become embedded is by setting up peer observations with colleagues. It is a valuable tool to contribute to informed, whole-school approaches to teaching and learning.

The focus of the peer observation must be determined before the practice takes place. This ensures all participants in the process are clear about the intention. Peer observations will only be successful if they are viewed as a collegiate activity based on trust.

According to Bryk and Schneider, high levels of “trust reduce the sense of vulnerability that teachers experience as they take on new and uncertain tasks associated with reform” and help ensure the feedback after an observation is valued (as cited in Hattie, 2009, p. 241).

To improve the practice of guided reading, peer observations can be arranged across Year levels or within a Year level depending on the focus. A framework for the observations is useful so that both parties know what it is that will be observed. It is important that the observer note down what they see and hear the teacher and the students say and do. Evidence must be tangible and not related to opinion, bias or interpretation (Danielson, 2012).

Examples of evidence relating to the guided reading practice might be:

- the words the teacher says (Today’s learning intention is to focus on making sure our reading makes sense. If it doesn’t, we need to reread and use our reading strategies to decode the tricky word)

- the words the students say (e.g. 'My reading goal is to break up a word into smaller parts when I don’t know it to help me decode the word').

- the actions of the teacher (Taking anecdotal notes as they listen to individual students read)

- what they can see the students doing (The group members all have their own copy of the text and read individually).

Noting specific examples of engagement and practice and using a reflective tool allows reviewers to provide feedback that is targeted to the evidence rather than the personality. Finding time for face-to-face feedback is a vital stage in peer observation. Danielson argues that “the conversations following an observation are the best opportunity to engage teachers in thinking through how they can strengthen their practice” (2012, p.36).

It's through collaborative reflection and evaluation that teaching and learning goals and the embedding of new practice takes place (Principles of Learning and Teaching [ PoLT ]: Action Research Model).

In practice examples

For in practice examples, see: Guided reading lessons

Bruner, J. (1986). Actual Minds, Possible Worlds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Christie, F. (2005). Language Education in the Primary Years. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press/University of Washington Press.

Danielson, C. (2012). Observing Classroom Practice, Educational Leadership, 70(3), 32-37.

Dewitz, P. & Dewitz, P. (February 2003), They can read the words, but they can’t understand: Refining comprehension assessment. In The Reading Teacher, 56 (5), 422-435.

Duke, N.K., Pearson, P.D., Strachan, S.L., & Billman, A.K. (2011). Essential Elements of Fostering and Teaching Reading Comprehension. In S. J. Samuels & A. E. Farstrup (Eds.), What research has to say about reading instruction (4th ed.) (pp. 51-59). Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Fisher, D., Frey, N. and Hattie, J. (2016). Visible learning for Literacy: Implementing Practices That Work Best to Accelerate Student Learning. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications.

Ford, M. P., & Opitz, M. F. (2011). Looking back to move forward with guided reading. Reading Horizons: A Journal of Literacy and Language Arts, 50(4), 3.

Hall, K. (2013). Effective Literacy Teaching in the Early Years of School: A Review of Evidence. In K. Hall, U. Goswami, C. Harrison, S. Ellis, and J. Soler (Eds), Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Learning to Read: Culture, Cognition and Pedagogy (pp. 523-540). London: Routledge.

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible Learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Publishers

Hill, P. & Crevola, C. (Unpublished)

Krashen, S.D. (2004). The Power of Reading: Insights from the Research (2nd Ed.). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

McCarthey,S.J., Hoffman, J.V., & Galda, L. (1999) ‘Readers in elementary classrooms: learning goals and instructional principles that can inform practice’ (Chapter 3) . In Guthrie, J.T. and Alvermann, D.E. (Eds.), Engaged reading: processes, practices and policy implications (pp.46-80). New York: Teachers College Press.

Principles of Learning and Teaching (PoLT): Action Research Model Accessed

Vygotsky, L.S. (1978). Mind in Society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cole, M., Jolm- Steiner, V., Scribner, S., Souberman, E. (eds) Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Our website uses a free tool to translate into other languages. This tool is a guide and may not be accurate. For more, see: Information in your language

Using Guided Reading to Develop Student Reading Independence

About this Strategy Guide

Guided reading gives teachers the opportunity to observe students as they read from texts at their instructional reading levels. This strategy guide describes ideas that support guided reading, including practical suggestions for implementing it in the classroom; introduces guided reading; and includes a reading list for further investigation.

Research Basis

Strategy in practice, related resources.

Guided reading is subject to many interpretations, but Burkins & Croft (2010) identify these common elements:

- Working with small groups

- Matching student reading ability to text levels

- Giving everyone in the group the same text

- Introducing the text

- Listening to individuals read

- Prompting students to integrate their reading processes

- Engaging students in conversations about the text

The goal is to help students develop strategies to apply independently. Work focuses on processes integral to reading proficiently, such as cross-checking print and meaning information, rather than on learning a particular book’s word meanings. (For example, a student might see an illustration and say “dog” when the text says puppy, but after noticing the beginning /p/ in puppy, correct the mistake.) During guided reading, teachers monitor student reading processes and check that texts are within students’ grasps, allowing students to assemble their newly acquired skills into a smooth, integrated reading system (Clay, p.17)

Preparation for Instruction Here is a general task list to consider before initiating guided reading instruction.

- Assess students to determine instructional reading levels (IRLs). At IRL, students should sound like good readers and comprehend well.

- Look for trends across classroom data. Cluster students into groups based on their IRLs, their skills, and how they solve problems when reading. Make groups flexible, based on student growth and change over time. If you must compromise reading level to assemble a group, always put students into an easier text rather than a more difficult one.

- Select a text that gives students the opportunity to engage in a balanced reading process. If a student looks at words but doesn’t think about the meaning or consider the pictures, find an IRL where the student uses all of the information the text offers. If there are more than a few problems for students to solve during reading, the text is too difficult.

- Plan a schedule for working with small groups, and organize materials for groups working independently. Independent work should be as closely connected to authentic reading and writing as possible; try things like rereading familiar texts or manipulating magnetic letters to explore word families.

The Guided Reading Session Individual lessons vary based on student needs and particular texts, but try this general structure.

- Familiar rereading—Observe and make notes while students read books from earlier guided reading lessons.

- Introduction—Ask students to examine the book to see what they notice. Support students guiding themselves through a preview of the book and thinking about the text. Students may notice the book’s format or a particular element of the print.

- Reading practice—Rotate from student to student while they read quietly or silently. Listen closely and make anecdotal notes. Intervene and prompt rarely, with broad questions like “What will you do next?”

- Discussion—Let students talk about what they noticed while reading. Support their efforts to think deeply and connect across the whole book. For example, a student may notice that an illustration opening the text shows ingredients in a pantry, and at the end, they are all over the kitchen.

- Teaching point—Offer a couple of instructions based on observations made during reading. Teaching points are most valuable when pointing to new things that students are demonstrating or ask for reflection on how they solved problems.

For Further Reading Burkins, J.M., & Croft, M.M. (2010). Preventing misguided reading: New strategies for guided reading teachers . Newark, DE: International Reading Association. Ford, M.P., & Opitz, M.F. (2008). Guided reading: Then and now. In M.J. Fresch (Ed.), An essential history of current reading practices (pp. 66-81). Newark, DE: International Reading Association. McLaughlin, M., & Allen, M.B. (2009). Guided comprehension in grades 3-8 (Combined 2nd Ed.). Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

- Print this resource

Explore Resources by Grade

- Kindergarten K

- ALI Overview

- Phonological Awareness

- Comprehension

Guided Reading

Guided Reading is a powerful and efficient way to differentiate and meet the specific needs of your children while you meet with them in small groups. It gives children a chance to problem solve with new texts in a safe environment and it gives you a chance to build rapport as you work side by side with the children.

Guided Reading in a First Grade Classroom: Zoom Zoom Readers

Guided Reading in a First Grade Classroom: Zoom Zoom Readers Directors Cut

In this Guided Reading lesson, the teacher models for children how to slow down while reading to make sure that what they are reading looks right, sounds right, and makes sense.

View this version of the Zoom Zoom Readers lesson for additional "look fors" and tips.

The purpose of Guided Reading is to help children become independent, strategic readers. When we understand and notice children’s reading behaviors, we can support them and give them exactly what they need to move forward.

“ Our teaching role changes during small-group time. Here, we support and scaffold the reader and help the child read as independently as possible. We want each student to problem solve and apply the strategies we have modeled in whole group instruction skillfully. The focus in small-group teaching is on having the child do more of the work than you are. The key is to know your students and find out what they can do during small group time. ” - Debbie Diller, Making the Most of Small Groups: Differentiation for All

Guided Reading supports a child-centered approach to instruction. We do Guided Reading because we know that all children:

Can be successful at reading whatever their level. When we meet children where they are and understand how reading develops, we can provide the scaffolding needed for their future growth.

Deserve to be taught at their level. Guided Reading is differentiated instruction at its best. All children deserve access to instructional level texts through which they can be guided to read.

Are responsible for their own learning. Guided Reading asks children to read the text on their own with some teacher support. The teacher notes the areas where they need assistance and provides strategies to scaffold them toward independence. Providing children with the necessary tools for success fosters confidence, motivation, and a sense of responsibility. When children understand their individual strengths and weaknesses, they can create action plans for improvement.

Guided Reading Is…

Guided Reading is a powerful and efficient way to differentiate and meet the specific needs of your children. It gives children a chance to problem solve and learn in a safe environment and it gives you a chance to build rapport with children.

“The idea is for children to take on novel texts, read them at once with a minimum of support, and read many of them again and again for independence and fluency.” - Guided Reading , Fountas and Pinnell p. 2.

A chance to meet the needs of all children in your classroom. In Guided Reading, you meet with groups of up to six children at a time who are reading at similar reading levels.

A time to support children as they take on more challenging texts. During Guided Reading, children read from the same instructional level texts. These are texts that they can understand, but that still provide them with some challenges and opportunities to problem solve.

An opportunity for children to learn in a more comfortable, supportive setting with peers who are in need of the same skill. Guided Reading is a time to teach a skill that a group of children need to move forward in reading. Not simply a time to reteach a skill taught earlier in your literacy block.

A way for you to get to know your children as readers. To be successful at Guided Reading, you’ll need to know your children’s strengths and needs and the process of reading and reading development.

Reflect on Your Guided Reading

If you are already doing Guided Reading in your classroom, take a few moments to think about how it is currently going. Use these questions to reflect on your own practice.

How do you currently plan for Guided Reading?

- How often do your groups change? What processes do you have for keeping groups flexible to meet children’s needs as their reading develops?

- What formal and informal assessments do you use to determine the strengths and needs of the children? Is there information missing that you would like to have?

- How do you use the information you have to form groups, choose books, and determine a teaching point?

- Do your children know what to do during the Guided Reading session? Are they able to concentrate on reading despite disruptions or distractions?

- What is the rest of the class doing while you are taking your small groups? Are you able to meet with your groups with minimal interruptions?

- How is your Guided Reading area organized? Do you have everything you need for your lessons at your fingertips?

What is your role and the role of the children before, during, and after reading the book?

- How do you preview the book with the children? Do you set a purpose before the children begin reading? How do you explain and demonstrate the teaching point to the children?

- Do you have a method for taking anecdotal notes while working with children? How do you organize your notes? How do you use them?

- What do you do when a child gets stuck while reading? Do you have tools for prompting and reminding children to use strategies?

- What do you do after reading to close out the lesson and consolidate learning?

- What role does word work or writing play in your Guided Reading lesson?

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I use my basal for Guided Reading?

Effective Guided Reading instruction depends on children reading texts at their instructional level. Almost every basal has selections at a wide range of text levels, so that one selection might be written at text level G, while the following one is at level M. Therefore, using your basal as the only source of texts for Guided Reading will not be effective or successful. You might be able to use certain basal selections for Guided Reading lessons, provided that these selections are carefully chosen to be at the readers’ instructional level. The importance of leveling the selections to make sure that they are appropriate for your readers cannot be overemphasized.

How many times a week should I meet with each group?

The number of times that a group meets with the teacher each week is dependent upon the number of groups in the class. Most teachers meet with three Guided Reading groups per day. That allows for 15 Guided Reading sessions per week. It is fairly common to have more than three groups in a class. Therefore, you will not be able to meet with every group every day. Meet with your highest support group every day. Fill in the balance of the slots with the other groups, of course keeping in mind that lower level groups will need more of your time than more advanced groups. Remember that Guided Reading is only one component of your literacy instruction. Your children are also benefiting from important literacy lessons in Intentional Read Aloud, shared reading, and independent reading.

Why can’t the children take turns reading a page aloud?

The purpose of Guided Reading is for children to problem solve and practice strategies using level-appropriate text. The role for each child in a Guided Reading group is to apply the focus strategy to the process of reading the entire text – not just a page. The teacher’s role is to support the readers by coaching, prompting, and confirming strategy use. Any format for Guided Reading which is incompatible with this predefined purpose and these predefined roles, such as taking turns reading aloud, would be inappropriate and counterproductive. We know that children love reading aloud and get some real benefit from it. So let’s provide appropriate opportunities for taking turns reading aloud. In partner reading, each child takes a turn reading aloud. In readers’ theater, children take turns reading aloud. They can also take turns reading aloud at the poetry center and the big book center – but not in their Guided Reading groups.

My children are not yet at level A. What do I do with them in a Guided Reading group?

Small group instruction is perfect for children who are not yet reading texts at level A. The small group setting allows the teacher to closely observe the children in order to gather pertinent information about their reading behaviors. Plan a 15 to 20 minute interactive lesson that will engage the pre-A readers in tasks working on sounds, letters, and words. Give them a chance to practice one-to-one matching in level-A texts and apply the lessons on sounds to interactive writing.

How do I select objectives? How do I know what to teach?

All effective Guided Reading lessons start with a literacy objective. Objectives can come from a variety of sources. One of the best sources of information is your anecdotal notes and running records. What are your children doing at the point of difficulty? Another source for Guided Reading lesson objectives is summative assessment data. What skills have the children mastered? What skills do they still need to learn? There are a number of excellent professional books that list lesson foci for each Guided Reading level, including The Next Step in Guided Reading (Richardson, 2009) and The Continuum of Literacy Learning (Fountas & Pinnell, 2010).

How long should children stay on a particular level?

Children continue to receive instruction in books at a given text level until they can successfully read texts at that level with 95% accuracy or higher. You determine this by having the child read an unfamiliar book or a “benchmark book” at that level and taking a running record. The length of time spent at a particular level of instruction varies with the level as well as with the child. It is expected that children will complete six text levels in first grade but only four text levels in third grade. Clearly, children will spend more time reading texts at level N (a third grade level) than they will at level E (a first grade level).

Can I use chapter books in Guided Reading?

Reading chapter books is a threshold that both readers and teachers celebrate. It means that the readers are now capable of processing print fluently and efficiently, holding information in their memories from one day to the next and keeping track of multiple characters and plot lines. The Guided Reading lesson is an appropriate forum for supporting children in making the transition from leveled texts and picture books to chapter books. But once they have successfully made that transition, consider shifting chapter book reading to literature circles instead of Guided Reading lessons. Your chapter book readers will still need targeted instruction during Guided Reading lessons.

Comments (9)

In Guided Reading, organization is the key. We need to stay organized and know the learning intention which guide you to come up with a meaningful station or differentiated activities. Just me thinking aloud c",)

WONDERFUL SITE XX

Where do you find the completed sample lesson plans for level A-c

I'm just loving this program. I enjoy introducing new ideas to my classroom.

Love video about zoom zoomers! The students love my input and I enjoyed teaching and being organized. The students were engaged and learning….Love it!

I changed up my organization over the years depending - However, I found that I preferred to keep one basket with that weeks guided reading books in it. I also liked to type up my entire weeks of guided reading plans onto one page if possible (maybe it would have to go on the back). For some books, if I had an extra copy- I might also leave myself sticky notes on the book. I kept a separate notebook with my guided reading conference notes. I found it best to just keep all the kids in one notebook. I used this book to drive my planning. All of this sat at my guided reading table along with any other materials. (White boards, markers, paper, pencils, colored pencils, etc.)

Finally, because I typed my lessons- I didn't keep the paper copies around long. If I needed too I could also print out a new copy.

Super excited to introduce this program to all levels of learners in my class!

I am just beginning guided reading and just soaking in all this information for best practice. I, too, love to hear how others stay organized and do lessons for guided reading.

I love learning new ways to stay organized. Does anyone want to share ideas about how they would organize materials, notes, lessons, etc.

Log in to post a comment.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 11 January 2023

The effectiveness of collaborative problem solving in promoting students’ critical thinking: A meta-analysis based on empirical literature

- Enwei Xu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6424-8169 1 ,

- Wei Wang 1 &

- Qingxia Wang 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 10 , Article number: 16 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

16k Accesses

16 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Science, technology and society

Collaborative problem-solving has been widely embraced in the classroom instruction of critical thinking, which is regarded as the core of curriculum reform based on key competencies in the field of education as well as a key competence for learners in the 21st century. However, the effectiveness of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking remains uncertain. This current research presents the major findings of a meta-analysis of 36 pieces of the literature revealed in worldwide educational periodicals during the 21st century to identify the effectiveness of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking and to determine, based on evidence, whether and to what extent collaborative problem solving can result in a rise or decrease in critical thinking. The findings show that (1) collaborative problem solving is an effective teaching approach to foster students’ critical thinking, with a significant overall effect size (ES = 0.82, z = 12.78, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.69, 0.95]); (2) in respect to the dimensions of critical thinking, collaborative problem solving can significantly and successfully enhance students’ attitudinal tendencies (ES = 1.17, z = 7.62, P < 0.01, 95% CI[0.87, 1.47]); nevertheless, it falls short in terms of improving students’ cognitive skills, having only an upper-middle impact (ES = 0.70, z = 11.55, P < 0.01, 95% CI[0.58, 0.82]); and (3) the teaching type (chi 2 = 7.20, P < 0.05), intervention duration (chi 2 = 12.18, P < 0.01), subject area (chi 2 = 13.36, P < 0.05), group size (chi 2 = 8.77, P < 0.05), and learning scaffold (chi 2 = 9.03, P < 0.01) all have an impact on critical thinking, and they can be viewed as important moderating factors that affect how critical thinking develops. On the basis of these results, recommendations are made for further study and instruction to better support students’ critical thinking in the context of collaborative problem-solving.

Similar content being viewed by others

Testing theory of mind in large language models and humans

Impact of artificial intelligence on human loss in decision making, laziness and safety in education

An overview of clinical decision support systems: benefits, risks, and strategies for success

Introduction.

Although critical thinking has a long history in research, the concept of critical thinking, which is regarded as an essential competence for learners in the 21st century, has recently attracted more attention from researchers and teaching practitioners (National Research Council, 2012 ). Critical thinking should be the core of curriculum reform based on key competencies in the field of education (Peng and Deng, 2017 ) because students with critical thinking can not only understand the meaning of knowledge but also effectively solve practical problems in real life even after knowledge is forgotten (Kek and Huijser, 2011 ). The definition of critical thinking is not universal (Ennis, 1989 ; Castle, 2009 ; Niu et al., 2013 ). In general, the definition of critical thinking is a self-aware and self-regulated thought process (Facione, 1990 ; Niu et al., 2013 ). It refers to the cognitive skills needed to interpret, analyze, synthesize, reason, and evaluate information as well as the attitudinal tendency to apply these abilities (Halpern, 2001 ). The view that critical thinking can be taught and learned through curriculum teaching has been widely supported by many researchers (e.g., Kuncel, 2011 ; Leng and Lu, 2020 ), leading to educators’ efforts to foster it among students. In the field of teaching practice, there are three types of courses for teaching critical thinking (Ennis, 1989 ). The first is an independent curriculum in which critical thinking is taught and cultivated without involving the knowledge of specific disciplines; the second is an integrated curriculum in which critical thinking is integrated into the teaching of other disciplines as a clear teaching goal; and the third is a mixed curriculum in which critical thinking is taught in parallel to the teaching of other disciplines for mixed teaching training. Furthermore, numerous measuring tools have been developed by researchers and educators to measure critical thinking in the context of teaching practice. These include standardized measurement tools, such as WGCTA, CCTST, CCTT, and CCTDI, which have been verified by repeated experiments and are considered effective and reliable by international scholars (Facione and Facione, 1992 ). In short, descriptions of critical thinking, including its two dimensions of attitudinal tendency and cognitive skills, different types of teaching courses, and standardized measurement tools provide a complex normative framework for understanding, teaching, and evaluating critical thinking.

Cultivating critical thinking in curriculum teaching can start with a problem, and one of the most popular critical thinking instructional approaches is problem-based learning (Liu et al., 2020 ). Duch et al. ( 2001 ) noted that problem-based learning in group collaboration is progressive active learning, which can improve students’ critical thinking and problem-solving skills. Collaborative problem-solving is the organic integration of collaborative learning and problem-based learning, which takes learners as the center of the learning process and uses problems with poor structure in real-world situations as the starting point for the learning process (Liang et al., 2017 ). Students learn the knowledge needed to solve problems in a collaborative group, reach a consensus on problems in the field, and form solutions through social cooperation methods, such as dialogue, interpretation, questioning, debate, negotiation, and reflection, thus promoting the development of learners’ domain knowledge and critical thinking (Cindy, 2004 ; Liang et al., 2017 ).

Collaborative problem-solving has been widely used in the teaching practice of critical thinking, and several studies have attempted to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of the empirical literature on critical thinking from various perspectives. However, little attention has been paid to the impact of collaborative problem-solving on critical thinking. Therefore, the best approach for developing and enhancing critical thinking throughout collaborative problem-solving is to examine how to implement critical thinking instruction; however, this issue is still unexplored, which means that many teachers are incapable of better instructing critical thinking (Leng and Lu, 2020 ; Niu et al., 2013 ). For example, Huber ( 2016 ) provided the meta-analysis findings of 71 publications on gaining critical thinking over various time frames in college with the aim of determining whether critical thinking was truly teachable. These authors found that learners significantly improve their critical thinking while in college and that critical thinking differs with factors such as teaching strategies, intervention duration, subject area, and teaching type. The usefulness of collaborative problem-solving in fostering students’ critical thinking, however, was not determined by this study, nor did it reveal whether there existed significant variations among the different elements. A meta-analysis of 31 pieces of educational literature was conducted by Liu et al. ( 2020 ) to assess the impact of problem-solving on college students’ critical thinking. These authors found that problem-solving could promote the development of critical thinking among college students and proposed establishing a reasonable group structure for problem-solving in a follow-up study to improve students’ critical thinking. Additionally, previous empirical studies have reached inconclusive and even contradictory conclusions about whether and to what extent collaborative problem-solving increases or decreases critical thinking levels. As an illustration, Yang et al. ( 2008 ) carried out an experiment on the integrated curriculum teaching of college students based on a web bulletin board with the goal of fostering participants’ critical thinking in the context of collaborative problem-solving. These authors’ research revealed that through sharing, debating, examining, and reflecting on various experiences and ideas, collaborative problem-solving can considerably enhance students’ critical thinking in real-life problem situations. In contrast, collaborative problem-solving had a positive impact on learners’ interaction and could improve learning interest and motivation but could not significantly improve students’ critical thinking when compared to traditional classroom teaching, according to research by Naber and Wyatt ( 2014 ) and Sendag and Odabasi ( 2009 ) on undergraduate and high school students, respectively.

The above studies show that there is inconsistency regarding the effectiveness of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking. Therefore, it is essential to conduct a thorough and trustworthy review to detect and decide whether and to what degree collaborative problem-solving can result in a rise or decrease in critical thinking. Meta-analysis is a quantitative analysis approach that is utilized to examine quantitative data from various separate studies that are all focused on the same research topic. This approach characterizes the effectiveness of its impact by averaging the effect sizes of numerous qualitative studies in an effort to reduce the uncertainty brought on by independent research and produce more conclusive findings (Lipsey and Wilson, 2001 ).

This paper used a meta-analytic approach and carried out a meta-analysis to examine the effectiveness of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking in order to make a contribution to both research and practice. The following research questions were addressed by this meta-analysis:

What is the overall effect size of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking and its impact on the two dimensions of critical thinking (i.e., attitudinal tendency and cognitive skills)?

How are the disparities between the study conclusions impacted by various moderating variables if the impacts of various experimental designs in the included studies are heterogeneous?

This research followed the strict procedures (e.g., database searching, identification, screening, eligibility, merging, duplicate removal, and analysis of included studies) of Cooper’s ( 2010 ) proposed meta-analysis approach for examining quantitative data from various separate studies that are all focused on the same research topic. The relevant empirical research that appeared in worldwide educational periodicals within the 21st century was subjected to this meta-analysis using Rev-Man 5.4. The consistency of the data extracted separately by two researchers was tested using Cohen’s kappa coefficient, and a publication bias test and a heterogeneity test were run on the sample data to ascertain the quality of this meta-analysis.

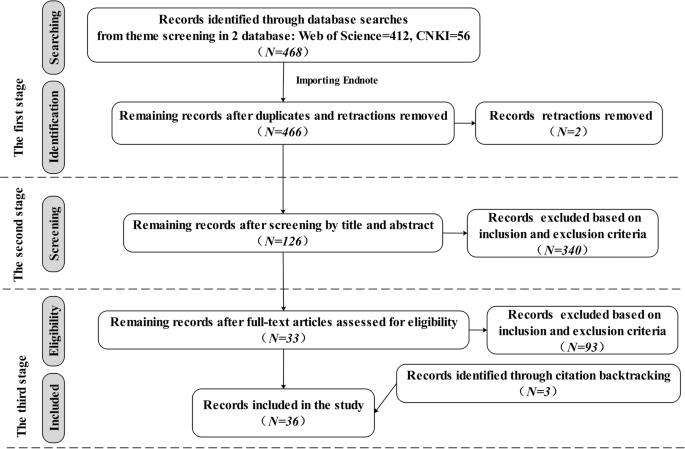

Data sources and search strategies

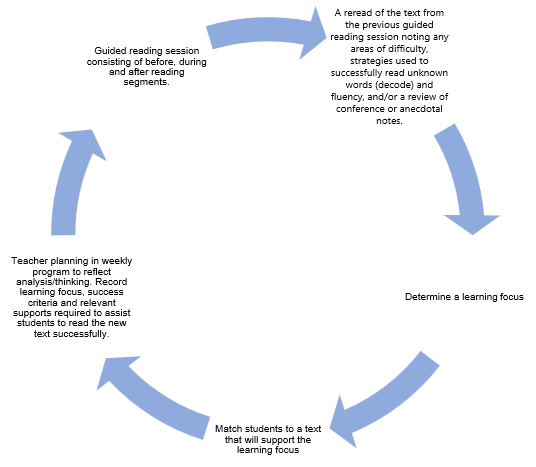

There were three stages to the data collection process for this meta-analysis, as shown in Fig. 1 , which shows the number of articles included and eliminated during the selection process based on the statement and study eligibility criteria.

This flowchart shows the number of records identified, included and excluded in the article.

First, the databases used to systematically search for relevant articles were the journal papers of the Web of Science Core Collection and the Chinese Core source journal, as well as the Chinese Social Science Citation Index (CSSCI) source journal papers included in CNKI. These databases were selected because they are credible platforms that are sources of scholarly and peer-reviewed information with advanced search tools and contain literature relevant to the subject of our topic from reliable researchers and experts. The search string with the Boolean operator used in the Web of Science was “TS = (((“critical thinking” or “ct” and “pretest” or “posttest”) or (“critical thinking” or “ct” and “control group” or “quasi experiment” or “experiment”)) and (“collaboration” or “collaborative learning” or “CSCL”) and (“problem solving” or “problem-based learning” or “PBL”))”. The research area was “Education Educational Research”, and the search period was “January 1, 2000, to December 30, 2021”. A total of 412 papers were obtained. The search string with the Boolean operator used in the CNKI was “SU = (‘critical thinking’*‘collaboration’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘collaborative learning’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘CSCL’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘problem solving’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘problem-based learning’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘PBL’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘problem oriented’) AND FT = (‘experiment’ + ‘quasi experiment’ + ‘pretest’ + ‘posttest’ + ‘empirical study’)” (translated into Chinese when searching). A total of 56 studies were found throughout the search period of “January 2000 to December 2021”. From the databases, all duplicates and retractions were eliminated before exporting the references into Endnote, a program for managing bibliographic references. In all, 466 studies were found.

Second, the studies that matched the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the meta-analysis were chosen by two researchers after they had reviewed the abstracts and titles of the gathered articles, yielding a total of 126 studies.

Third, two researchers thoroughly reviewed each included article’s whole text in accordance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Meanwhile, a snowball search was performed using the references and citations of the included articles to ensure complete coverage of the articles. Ultimately, 36 articles were kept.

Two researchers worked together to carry out this entire process, and a consensus rate of almost 94.7% was reached after discussion and negotiation to clarify any emerging differences.

Eligibility criteria

Since not all the retrieved studies matched the criteria for this meta-analysis, eligibility criteria for both inclusion and exclusion were developed as follows:

The publication language of the included studies was limited to English and Chinese, and the full text could be obtained. Articles that did not meet the publication language and articles not published between 2000 and 2021 were excluded.

The research design of the included studies must be empirical and quantitative studies that can assess the effect of collaborative problem-solving on the development of critical thinking. Articles that could not identify the causal mechanisms by which collaborative problem-solving affects critical thinking, such as review articles and theoretical articles, were excluded.

The research method of the included studies must feature a randomized control experiment or a quasi-experiment, or a natural experiment, which have a higher degree of internal validity with strong experimental designs and can all plausibly provide evidence that critical thinking and collaborative problem-solving are causally related. Articles with non-experimental research methods, such as purely correlational or observational studies, were excluded.

The participants of the included studies were only students in school, including K-12 students and college students. Articles in which the participants were non-school students, such as social workers or adult learners, were excluded.

The research results of the included studies must mention definite signs that may be utilized to gauge critical thinking’s impact (e.g., sample size, mean value, or standard deviation). Articles that lacked specific measurement indicators for critical thinking and could not calculate the effect size were excluded.

Data coding design

In order to perform a meta-analysis, it is necessary to collect the most important information from the articles, codify that information’s properties, and convert descriptive data into quantitative data. Therefore, this study designed a data coding template (see Table 1 ). Ultimately, 16 coding fields were retained.

The designed data-coding template consisted of three pieces of information. Basic information about the papers was included in the descriptive information: the publishing year, author, serial number, and title of the paper.

The variable information for the experimental design had three variables: the independent variable (instruction method), the dependent variable (critical thinking), and the moderating variable (learning stage, teaching type, intervention duration, learning scaffold, group size, measuring tool, and subject area). Depending on the topic of this study, the intervention strategy, as the independent variable, was coded into collaborative and non-collaborative problem-solving. The dependent variable, critical thinking, was coded as a cognitive skill and an attitudinal tendency. And seven moderating variables were created by grouping and combining the experimental design variables discovered within the 36 studies (see Table 1 ), where learning stages were encoded as higher education, high school, middle school, and primary school or lower; teaching types were encoded as mixed courses, integrated courses, and independent courses; intervention durations were encoded as 0–1 weeks, 1–4 weeks, 4–12 weeks, and more than 12 weeks; group sizes were encoded as 2–3 persons, 4–6 persons, 7–10 persons, and more than 10 persons; learning scaffolds were encoded as teacher-supported learning scaffold, technique-supported learning scaffold, and resource-supported learning scaffold; measuring tools were encoded as standardized measurement tools (e.g., WGCTA, CCTT, CCTST, and CCTDI) and self-adapting measurement tools (e.g., modified or made by researchers); and subject areas were encoded according to the specific subjects used in the 36 included studies.

The data information contained three metrics for measuring critical thinking: sample size, average value, and standard deviation. It is vital to remember that studies with various experimental designs frequently adopt various formulas to determine the effect size. And this paper used Morris’ proposed standardized mean difference (SMD) calculation formula ( 2008 , p. 369; see Supplementary Table S3 ).

Procedure for extracting and coding data

According to the data coding template (see Table 1 ), the 36 papers’ information was retrieved by two researchers, who then entered them into Excel (see Supplementary Table S1 ). The results of each study were extracted separately in the data extraction procedure if an article contained numerous studies on critical thinking, or if a study assessed different critical thinking dimensions. For instance, Tiwari et al. ( 2010 ) used four time points, which were viewed as numerous different studies, to examine the outcomes of critical thinking, and Chen ( 2013 ) included the two outcome variables of attitudinal tendency and cognitive skills, which were regarded as two studies. After discussion and negotiation during data extraction, the two researchers’ consistency test coefficients were roughly 93.27%. Supplementary Table S2 details the key characteristics of the 36 included articles with 79 effect quantities, including descriptive information (e.g., the publishing year, author, serial number, and title of the paper), variable information (e.g., independent variables, dependent variables, and moderating variables), and data information (e.g., mean values, standard deviations, and sample size). Following that, testing for publication bias and heterogeneity was done on the sample data using the Rev-Man 5.4 software, and then the test results were used to conduct a meta-analysis.

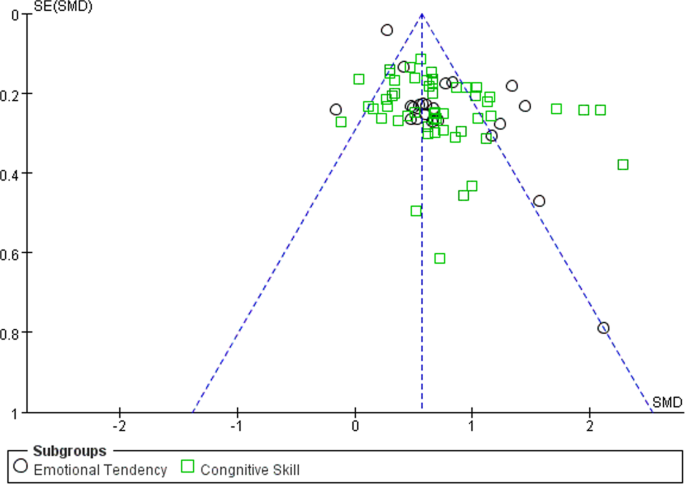

Publication bias test

When the sample of studies included in a meta-analysis does not accurately reflect the general status of research on the relevant subject, publication bias is said to be exhibited in this research. The reliability and accuracy of the meta-analysis may be impacted by publication bias. Due to this, the meta-analysis needs to check the sample data for publication bias (Stewart et al., 2006 ). A popular method to check for publication bias is the funnel plot; and it is unlikely that there will be publishing bias when the data are equally dispersed on either side of the average effect size and targeted within the higher region. The data are equally dispersed within the higher portion of the efficient zone, consistent with the funnel plot connected with this analysis (see Fig. 2 ), indicating that publication bias is unlikely in this situation.

This funnel plot shows the result of publication bias of 79 effect quantities across 36 studies.

Heterogeneity test

To select the appropriate effect models for the meta-analysis, one might use the results of a heterogeneity test on the data effect sizes. In a meta-analysis, it is common practice to gauge the degree of data heterogeneity using the I 2 value, and I 2 ≥ 50% is typically understood to denote medium-high heterogeneity, which calls for the adoption of a random effect model; if not, a fixed effect model ought to be applied (Lipsey and Wilson, 2001 ). The findings of the heterogeneity test in this paper (see Table 2 ) revealed that I 2 was 86% and displayed significant heterogeneity ( P < 0.01). To ensure accuracy and reliability, the overall effect size ought to be calculated utilizing the random effect model.

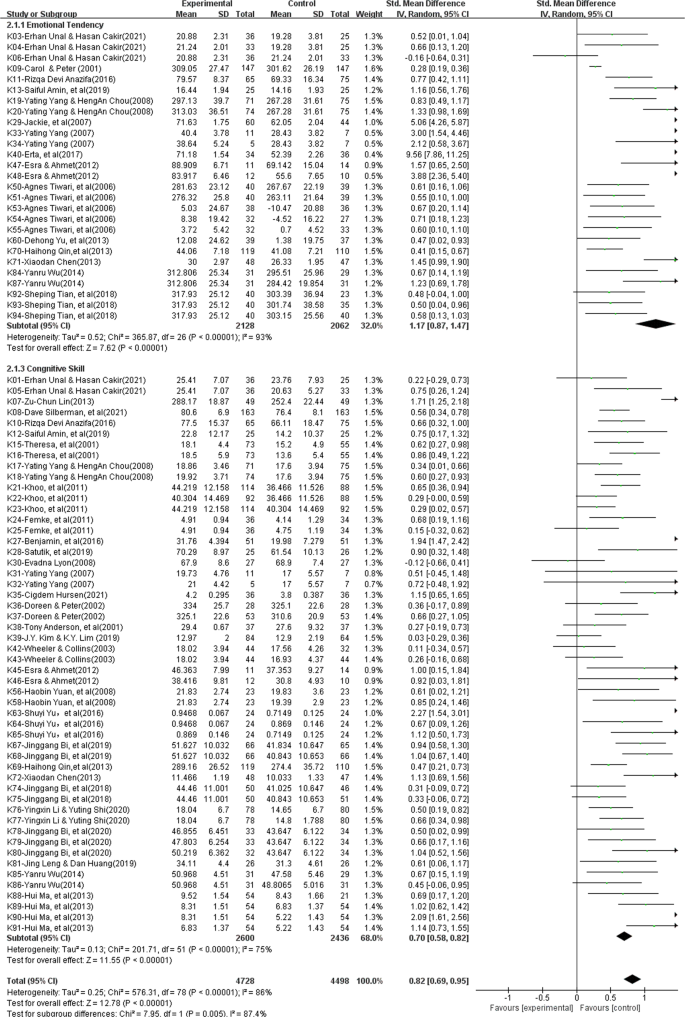

The analysis of the overall effect size

This meta-analysis utilized a random effect model to examine 79 effect quantities from 36 studies after eliminating heterogeneity. In accordance with Cohen’s criterion (Cohen, 1992 ), it is abundantly clear from the analysis results, which are shown in the forest plot of the overall effect (see Fig. 3 ), that the cumulative impact size of cooperative problem-solving is 0.82, which is statistically significant ( z = 12.78, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.69, 0.95]), and can encourage learners to practice critical thinking.

This forest plot shows the analysis result of the overall effect size across 36 studies.

In addition, this study examined two distinct dimensions of critical thinking to better understand the precise contributions that collaborative problem-solving makes to the growth of critical thinking. The findings (see Table 3 ) indicate that collaborative problem-solving improves cognitive skills (ES = 0.70) and attitudinal tendency (ES = 1.17), with significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 7.95, P < 0.01). Although collaborative problem-solving improves both dimensions of critical thinking, it is essential to point out that the improvements in students’ attitudinal tendency are much more pronounced and have a significant comprehensive effect (ES = 1.17, z = 7.62, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.87, 1.47]), whereas gains in learners’ cognitive skill are slightly improved and are just above average. (ES = 0.70, z = 11.55, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.58, 0.82]).

The analysis of moderator effect size

The whole forest plot’s 79 effect quantities underwent a two-tailed test, which revealed significant heterogeneity ( I 2 = 86%, z = 12.78, P < 0.01), indicating differences between various effect sizes that may have been influenced by moderating factors other than sampling error. Therefore, exploring possible moderating factors that might produce considerable heterogeneity was done using subgroup analysis, such as the learning stage, learning scaffold, teaching type, group size, duration of the intervention, measuring tool, and the subject area included in the 36 experimental designs, in order to further explore the key factors that influence critical thinking. The findings (see Table 4 ) indicate that various moderating factors have advantageous effects on critical thinking. In this situation, the subject area (chi 2 = 13.36, P < 0.05), group size (chi 2 = 8.77, P < 0.05), intervention duration (chi 2 = 12.18, P < 0.01), learning scaffold (chi 2 = 9.03, P < 0.01), and teaching type (chi 2 = 7.20, P < 0.05) are all significant moderators that can be applied to support the cultivation of critical thinking. However, since the learning stage and the measuring tools did not significantly differ among intergroup (chi 2 = 3.15, P = 0.21 > 0.05, and chi 2 = 0.08, P = 0.78 > 0.05), we are unable to explain why these two factors are crucial in supporting the cultivation of critical thinking in the context of collaborative problem-solving. These are the precise outcomes, as follows:

Various learning stages influenced critical thinking positively, without significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 3.15, P = 0.21 > 0.05). High school was first on the list of effect sizes (ES = 1.36, P < 0.01), then higher education (ES = 0.78, P < 0.01), and middle school (ES = 0.73, P < 0.01). These results show that, despite the learning stage’s beneficial influence on cultivating learners’ critical thinking, we are unable to explain why it is essential for cultivating critical thinking in the context of collaborative problem-solving.

Different teaching types had varying degrees of positive impact on critical thinking, with significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 7.20, P < 0.05). The effect size was ranked as follows: mixed courses (ES = 1.34, P < 0.01), integrated courses (ES = 0.81, P < 0.01), and independent courses (ES = 0.27, P < 0.01). These results indicate that the most effective approach to cultivate critical thinking utilizing collaborative problem solving is through the teaching type of mixed courses.

Various intervention durations significantly improved critical thinking, and there were significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 12.18, P < 0.01). The effect sizes related to this variable showed a tendency to increase with longer intervention durations. The improvement in critical thinking reached a significant level (ES = 0.85, P < 0.01) after more than 12 weeks of training. These findings indicate that the intervention duration and critical thinking’s impact are positively correlated, with a longer intervention duration having a greater effect.

Different learning scaffolds influenced critical thinking positively, with significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 9.03, P < 0.01). The resource-supported learning scaffold (ES = 0.69, P < 0.01) acquired a medium-to-higher level of impact, the technique-supported learning scaffold (ES = 0.63, P < 0.01) also attained a medium-to-higher level of impact, and the teacher-supported learning scaffold (ES = 0.92, P < 0.01) displayed a high level of significant impact. These results show that the learning scaffold with teacher support has the greatest impact on cultivating critical thinking.