- Find Studies

For Researchers

- Learn about Research

What does it mean to do research within a community?

Some researchers do studies in a lab. Some do studies in a clinic. Some do studies in hospitals. And some do studies within a community. You might be thinking, what does it mean to do research within a community? What do researchers even mean when they say “community”? Why do they want to do research with a community? How do they learn about communities? These are all great questions!

“Community” can mean a lot of different things when it comes to research. Researchers think about communities in many different ways. A community could be people who live in the same area. It could be people who are in the same age group (like children, or older adults). It could be people who share the same identities, speak the same languages, work the same jobs, experience the same health issues, join the same social media groups, enjoy doing the same activities…or people who feel connected to each other for any of these reasons, and others!

Just like there are many different types of communities, there are a lot of reasons why researchers might be interested in doing research with communities. Some researchers want to find out about how people live their lives within their communities to help improve everyday health. Some want to figure out what the most important health issues are in a community. And others want to see if a new program might help make communities healthier.

How do researchers learn about communities?

Imagine you just moved to a new town – how would you try to learn about your new home? Would you go to some events? Try to meet new people? Talk to your neighbors? Find groups that do activities you like? Now, if you were a researcher, how would you try to learn about a community you wanted to work with? If your answers seem similar, that’s because…well…they are. When researchers want to learn about communities, the best thing they can do is (you guessed it) get out there! As a researcher tries to learn more about a community, they might go to events, volunteer with community groups, or meet with people who are interested in the same health topics as they are. They might try to find out what research projects are already going on in a community by talking to other researchers. They might try to find out what health topics are most important to community members by looking at community health reports, or maybe even by trying to organize a listening session where community members come and share their thoughts and feelings about a research topic. The more time a researcher can spend learning about a community, the better their research can be! If you see a researcher out in your community before a research project starts, they might be trying to:

- Build trust and relationships with community members

- Choose a research topic that the community is interested in

- Pick a type of study that the community wants to take part in

- Learn what results community members want to see from the research

- Figure out what might make it hard for community members to join a research study and what might make it easier

- Learn if the community wants to help plan, do, or share the research

How can researchers work with a community on a research project?

One of the most important things a researcher can learn when they want to work with communities is how much a community wants to help plan, do, and share the research. Sometimes research projects happen in communities. Research that happens in communities is called community-based research . You might also think of research as happening on communities (research should not feel like it is happening on you!). Well, research can happen with communities, too. Working with communities on a research project is called community-engaged research .

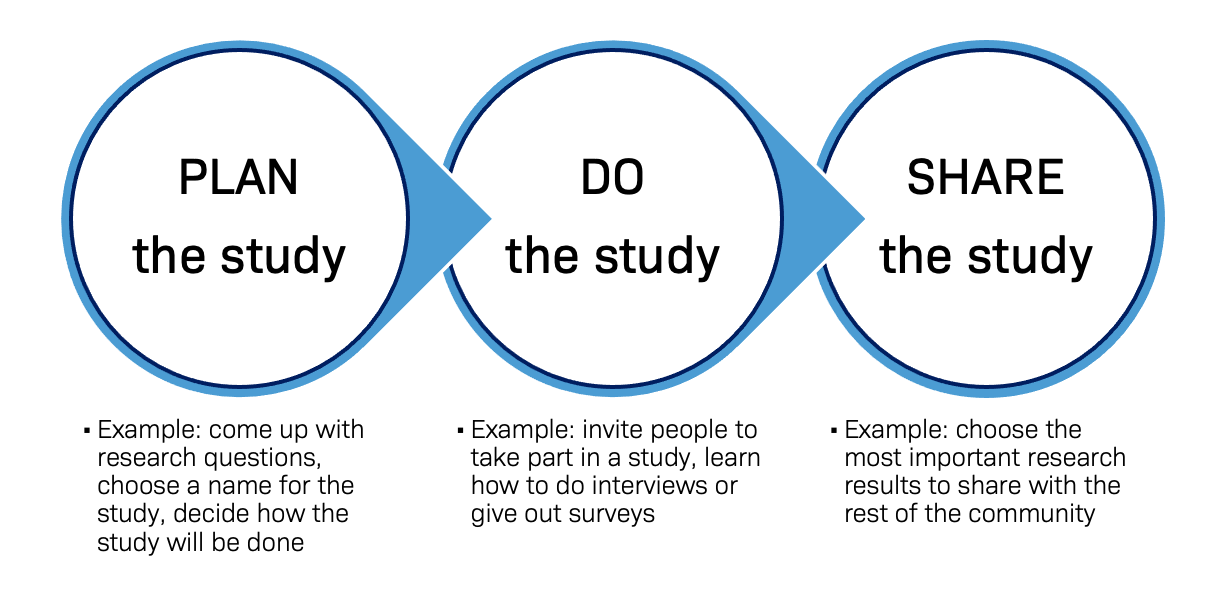

Even though community-engaged research is one type of research, these projects can all look really different. There are many ways to “engage” with communities on a research project. This is why it is so important for researchers to talk with communities about how involved they want to be in planning, doing, and sharing the research. Researchers can work with community members to…

Researchers can work with communities on one part of a research project (like PLAN), or all parts of a research project (PLAN, DO, and SHARE). And sometimes researchers will work with the same communities on many different research projects! It all depends on the researcher, the study, and what the community wants.

What if researchers really want to put the community in the driver’s seat?

Sometimes, when communities are really involved with research, it is called community-based participatory research or CBPR . In community-based participatory research projects, communities aren’t just doing research with a researcher – they are leading the research! Community-based participatory research is done through a true and equal partnership of community members and a researcher or research team. The ideas, research topic, study design…pretty much everything about the research…is driven by community members. They have the power to make decisions about all parts of the study and how the research is done. Community-based participatory research studies usually try to understand big issues impacting communities (maybe something like access to healthcare or poverty within a community) and try to find solutions through policy and social change. This type of research takes a lot of time, strong relationships, and trust between community partners and researchers.

So, to wrap it all up…

There are many researchers out there who work with communities on research. Working with communities to do research takes time, trust, and effort – but it makes the research so much better for everyone!

Copyright © 2013-2022 The NC TraCS Institute, the integrated home of the NIH Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA) Program at UNC-CH. This website is made possible by CTSA Grant UL1TR002489 and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences.

Helpful Links

- My UNC Chart

- Find a Doctor

- Accessibility

- Privacy Policy

- Duke NetID Login

- 919.660.1100

- Duke Health Badge: 24-hour access

- Accounts & Access

- Databases, Journals & Books

- Request & Reserve

- Training & Consulting

- Request Articles & Books

- Renew Online

- Reserve Spaces

- Reserve a Locker

- Study & Meeting Rooms

- Course Reserves

- Digital Health Device Collection

- Pay Fines/Fees

- Recommend a Purchase

- Access From Off Campus

- Building Access

- Computers & Equipment

- Wifi Access

- My Accounts

- Mobile Apps

- Known Access Issues

- Report an Access Issue

- All Databases

- Article Databases

- Basic Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Dissertations & Theses

- Drugs, Chemicals & Toxicology

- Grants & Funding

- Interprofessional Education

- Non-Medical Databases

- Search for E-Journals

- Search for Print & E-Journals

- Search for E-Books

- Search for Print & E-Books

- E-Book Collections

- Biostatistics

- Global Health

- MBS Program

- Medical Students

- MMCi Program

- Occupational Therapy

- Path Asst Program

- Physical Therapy

- Researchers

- Community Partners

Conducting Research

- Archival & Historical Research

- Black History at Duke Health

- Data Analytics & Viz Software

- Data: Find and Share

- Evidence-Based Practice

- NIH Public Access Policy Compliance

- Publication Metrics

- Qualitative Research

- Searching Animal Alternatives

- Systematic Reviews

- Test Instruments

Using Databases

- JCR Impact Factors

- Web of Science

Finding & Accessing

- COVID-19: Core Clinical Resources

- Health Literacy

- Health Statistics & Data

- Library Orientation

Writing & Citing

- Creating Links

- Getting Published

- Reference Mgmt

- Scientific Writing

Meet a Librarian

- Request a Consultation

- Find Your Liaisons

- Register for a Class

- Request a Class

- Self-Paced Learning

Search Services

- Literature Search

- Systematic Review

- Animal Alternatives (IACUC)

- Research Impact

Citation Mgmt

- Other Software

Scholarly Communications

- About Scholarly Communications

- Publish Your Work

- Measure Your Research Impact

- Engage in Open Science

- Libraries and Publishers

- Directions & Maps

- Floor Plans

Library Updates

- Annual Snapshot

- Conference Presentations

- Contact Information

- Gifts & Donations

A Researcher's Guide to Community Engaged Research: What is CEnR?

What is cenr.

- Recommended Reading from Our Community Partners

- Glossary of Terms

- Engaging with Government

- Duke Publications

- Recorded Trainings on Community Engaged Research Practices

- Association for Clinical and Translational Science 2024 Abstract Collection - Clinical Research Forum

Introduction

This guide is an introduction to Community Engaged Research (CEnR), which is defined by the WK Kellogg Community Health Scholars Program as "begin[ning] with a research topic of importance to the community, [and] having] the aim of combining knowledge with action and achieving social change to improve health outcomes and eliminate health disparities."

Here at the Clinical and Translational Science Institute's Community Engaged Research Initiative (CERI) , Duke faculty and staff work with researchers and community members to develop relationships, improve research, and create better health outcomes in our communities, particularly for historically disadvantaged groups of people.

This guide provides resources targeted toward researchers who are looking to learn more about CEnR and implement it in their work, and includes resources about two key concepts in CEnR: cultural competence/humility and plain language .

Diagram Note: Outreach is a preparatory step that does not formally constitute community engagement.

Foundational Principles

Principles of community engagement .

(Developed by the NIH, CDC, ATSDR, and CTSA)

Be clear about the purposes of engagement and the populations you wish to engage

Become knowledgeable about the community, establish relationships, collective self-determination is the responsibility and right of the community, partnering is necessary to create change and improve health, recognize and respect the diversity of the community, mobilize community assets and develop community capacity to take action, release control of actions and be flexible to meet changing needs, collaboration requires long-term commitment.

For more information, please consult:

How-To Guides, Manuals, and Toolkits

Community involvement in research, what does community-engaged research look like.

- Community stakeholders on project steering committees and other deliberative and decision-making bodies

- Community advisory boards

- Compensation for the community's time and other contributions

- Dissemination of results back out to the community

- Takes time!

What community-engaged research is NOT:

- Focus groups or interviews

- A research methodology

- A one-size fits all approach

- Appropriate for all research

- Recruitment of minority research participants

- A relinquishing of all insight or control by researchers

Key Concept: Cultural Competence and Cultural Humility

Key concept: plain language, for more information.

The CTSI Community Engaged Research Initiative (CERI) facilitates equitable, authentic, and robust community-engaged research to improve health. Contact CERI if you are a Duke researcher who wants more information about CEnR or to access CERI's services, which include consultation services and community studios, community partnerships and coalitions, and CEnR education and training.

For more information about the resources in this guide, contact Leatrice Martin ([email protected]).

- Next: What is CEnR? >>

- Last Updated: May 6, 2024 7:21 AM

- URL: https://guides.mclibrary.duke.edu/CENR_researchers

- Duke Health

- Duke University

- Duke Libraries

- Medical Center Archives

- Duke Directory

- Seeley G. Mudd Building

- 10 Searle Drive

- [email protected]

People and Communities

Community-engaged research brings people in local communities into the research process, especially people who will benefit from or be impacted by the research. The idea is that people and communities become equal partners in how the study is designed, conducted, analyzed, and shared with the world. Ongoing dialogue ensures that the communities' beliefs, cultures, languages, needs, and strengths are woven throughout the study’s process.

People from the community bring their lived experiences, needs, and strengths to these studies to:

- Craft research questions and inform other specific study details.

- Collect research data using community-informed strategies to engage participants and get meaningful data.

- Advise on policies and decisions related to safe and effective conduct of the research.

- Co-create interventions or programs that have a good fit with the community.

- Design appropriate materials tailored to specific cultures and languages.

- Analyze and report data in ways that acknowledge unique strengths and challenges within specific populations and are understandable to community audiences.

Benefits of Community-Engaged Research

Community-engaged research can:

- Address health disparities by making sure the strategies and interventions studied speak to and meet the needs of the people most affected by the topics being addressed.

- Build trust in science by including people from the community as equal partners from the start through the end of research studies.

- Improve health knowledge by working with trusted messengers to address questions, worries, or fears in the community.

Importance of Inclusion

CEAL research involves people with different backgrounds and lived experiences. Culture, language, family history, where and how one lives or works, past exposures, and risk of future exposures are just some factors that can impact how well a program or intervention will function.

CEAL is aligned with the conceptual model for community engagement published by the National Academy of Medicine.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

A newer edition of this book is available.

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

24 Community-Based Research: Understanding the Principles, Practices, Challenges, and Rationale

Margaret R. Boyd Bridgewater State University Bridgewater, MA, USA

- Published: 01 July 2014

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Community-based research challenges the traditional research paradigm by recognizing that complex social problems today must involve multiple stakeholders in the research process—not as subjects but as co-investigators and co-authors. It is an “orientation to inquiry” rather than a methodology and reflects a transdisciplinary paradigm by including academics from many different disciplines, community members, activists, and often students in all stages of the research process. Community-based research is relational research where all partners change and grow in a synergistic relationship as they work together and strategize to solve issues and problems that are defined by and meaningful to them. This chapter is an introduction to the historical roots and subdivisions within community-based research and discusses the core principles and skills useful when designing and working with community members in a collaborative, innovative, and transformative research partnership. The rationale for working within this research paradigm is discussed as well as the challenges researchers and practitioners face when conducting community-based research. As the scholarship and practice of this form of research has increased dramatically over the last twenty years, this chapter looks at both new and emerging issues as well as founding questions that continue to be debated in the contemporary discourse.

It is best to begin, I think, by reminding you, the beginning student, that the most admirable thinkers within the scholarly community you have chosen to join do not split their work from their lives. They seem to take both too seriously to allow such disassociation. — C.W. Mills, (1959 , 195)

Community-based research challenges the traditional research paradigm by recognizing that complex social problems today must involve multiple stakeholders in the research process—not as subjects but as co-investigators and co-authors. It has roots in critical pedagogy, as well as critical and feminist theory, and is research centered on social justice and community empowerment. Community-based research is not a methodology; it is an “orientation to inquiry” where researchers and community stakeholders collaborate to address community-identified problems and investigate meaningful and realistic solutions. Community-based research came out of a growing discontent among academics, researchers, and practitioners with the positivist research paradigm and instead argues that research must be “value based” not “value free.” It is relational research that fosters both individual and collective transformation. Community-based research also challenges disciplinary silos and instead fosters a transdisciplinary research paradigm.

There has been a growing interest and expectation within academia and community organizations that campus–community research partnerships provide benefits and challenges. We have seen a proliferation of research partnerships, courses, workshops and trainings on how to collaborate with community partners in community-driven research projects. There has also been a substantial increase in the literature (books and articles) describing best practices providing exemplars, and discussing methodologies. Israel, Eng, Schulz, and Parker (2005) argue that within the field of public health “researchers, practitioners, community members, and funders have increasingly recognized the importance of comprehensive and participatory approaches to research and intervention” (3).

This chapter begins with a discussion of the historical roots and theoretical background to this form of inquiry and a clarification of terminology. I include a discussion of the rationale and evaluation literature that offers convincing evidence for new and experienced researchers to consider this alternative research paradigm. Building on the work of others, I discuss seven core principles of community-based research and a list of skills often useful in the practice of engaged scholarship. This chapter argues that, as community-based research continues to grow, it is important that our scholarship includes exemplars, reflection, evaluation, and a critical discussion of best practices. This chapter hopes to contribute to this discourse.

I cannot think for others or without others, nor can others think for me. Even if the peoples thinking is superstitious or naïve, it is only as they rethink their assumptions in action that they can change. Producing and acting upon their own ideas—not consuming those of others. — Freire, 1970 , 108

The epistemology of community-based research can be traced back to many roots—Karl Marx, John Dewey, Paulo Freire, C.W. Mills, Thomas Kuhn, and Jane Addams to name but a few. Community-based research as it is practiced today has been enriched by the diversity of thoughts, methodologies, and practices that has been its foundation. The practice and scholarship of community-based research can found in many disciplines: sociology, psychology, economics, philosophy, education, public health, anthropology, urban planning and development, and social work. Different historical traditions and academic disciplines have led to contemporary differences in the form or focus of engaged scholarship, but what has united many practitioners and scholars is a social justice mission and the desire for personal and structural transformation. Lykes and Mallona (2008) argue:

Critical pedagogy (Freire) and liberation theologies (Berryman, Boff, Gutierrez, Ruether, Cone) and liberation psychologies (Martin-Baro, Watts, and Serrano-Garcia, Moane) emerged within relatively similar historical moments characterized by widespread social upheavals including armed struggle and broad- based non-violent social movements. A belief that the poor could be producers of knowledge and lead the transformation to a new social reality. [114]

Today you can find community-based research pedagogy, practices and scholarship across disciplines and collaboration between disciplines including new areas such as medicine, native or aboriginal research, conflict studies, history, and archeology. The expansion of community-engaged scholarship as epistemology reflects an important paradigm shift towards understanding multiple ways of knowing and experiential learning as critical to good research practices.

While it is not possible to include an extensive summary of the history and development of community-based research here, a brief review is necessary to provide the context and rationale for this major epistemological paradigm shift across multiple disciplines. Wicks, Reason, and Bradbury (2008) identify the influence of critical theory, civil rights, feminist movements, liberationists, and critical race theory—“critiques of domination and marginalization” and “critical examination of issues of power, identity and agency” (19). The historical roots and scholars who, I believe, have most influenced the development of community-based research are critical pedagogy (Paulo Freire and John Dewey), critical theory (Karl Marx and C.W. Mills), the epistemology of knowledge (Thomas Kuhn), and feminist theory (Jane Addams).

While Marx is noted for his writing about the conditions of the working class in Europe and his theories of alienation and oppression under capitalism, he was also an active participant in the French Revolution. According to Hall (cited in Ozerdem and Bowd, 2010 ) Marx was not only doing research and theorizing about the working classes but actively working with the workers to educate and raise consciousness. In addition to building theory, Marx and Engels sought to radically change and improve the political, economic, and social structure of society. The need to work with those most disadvantaged to challenge institutional inequality and power relationships is reflected in the principles of community-based research today. Many academics and scholars working from a critical theoretical perspective found a synergy with the principles and practices of community-based research.

Within education, John Dewey and Paulo Freire were reformers, activists, and key figures working to challenge traditional pedagogy and positivist research practices. Both were very influential in connecting research, theory, action, and refection to social reform. John Dewey (1859–1952) questioned the relevance of much of what was considered “education” by asking, “How many found what they did learn so foreign to the situations of life outside the school as to give them no power or control over the latter” (cited in Noll, 2010 , 8). Dewey saw educational institutions as agencies of social reform and social change through providing opportunities for learning and engagement with the world beyond the classroom. Summarizing Dewey, Peterson (2009) wrote:

Dewey believed that learning is a wholehearted affair; that is, you can’t sever knowing and doing, and with cycles of action and reflection, one’s greatest learning occurs. Dewey was interested in the learning that resulted from the mutual exchange between people and their environment. [542]

Dewey argued that learning—action and reflection—must take place in commune with one’s environment. Learning is co-created rather than unidirectional; a challenge to the traditional view of knowledge transfer from teacher to learner. Co-education and co-learning are key principles of community-based research.

Paulo Freire (1921–1997), the founder of critical pedagogy, also challenged conventional educational pedagogy and traditional research paradigms and saw education’s potential as liberation from oppression. His most famous and widely distributed book, Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1970) , was a call to action for both teacher and student to work together for social change and social reform. Freire saw learning as a two-way process involving “conscientization”—critical analysis and reflection leading to action. It is only through theory and practice, action and reflection, that real social change is possible. He also saw that the poor and oppressed can and must be leaders of their own liberation. Freire’s work—in challenging pedagogy and demanding researchers and academics to work with and learn from those most oppressed—has greatly influenced the practice of community-based research today.

Sociologist C.W. Mills also influenced critical pedagogy and engaged scholarship. In his classic work The Sociological Imagination (1959) he wrote:

An educator must begin with what interests the individual most deeply, even if it seems altogether trivial and cheap. He must proceed in such a way and with such materials as to enable the student to gain increasingly rational insight into these concerns, and into others he will acquire in the process of his education.... [187], We are trying to make the society more democratic. [189]

Similar to Freire, Mills challenged the social sciences to educate and through experiential education to foster democratic citizenry. Mills saw the connection between personal troubles and public issues and the role of sociology in helping others see the larger structures in society and how they reinforced inequality.

Another scholar who had a major influence on the development of community-based research is Thomas Kuhn in his classic book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1996). Kuhn’s work regarding the theory of the subjective nature of knowledge raised epistemological questions of “how we know what we know” and “what it is that we value as knowledge” (Wicks, Reason, & Bradbury, 2008 ). This became critically important in the development of engaged scholarship as academics and researchers began to respect and validate local knowledge, expertise, and other ways of thinking as equal to the knowledge and skills they could offer. Kuhn’s work led to questions about the privileged position of the researcher and how this privilege has denied or denigrated the experiential knowledge and understandings of oppressed groups.

It is also important to note the influence of feminist theory, in particular Jane Addams, on the development of community-based research and scholarship. Addams (1860–1935), a social activist and sociologist, played a key role in the development of engaged scholarship and community research. Naples (1996) writes that feminists argued for “a methodology designed to break the false separation between the subject of the research and the researcher” (160). Addams employed hundreds of women to go into their communities to interview, observe, and understand the experiences of other immigrant women in Chicago early in the twentieth century.

Addams also saw the need to make research relevant to the communities in which it originated. Much of the data gathered in Chicago was published as Hull House Maps and Papers (1895) and was for the benefit of the community, not for an academic audience. Her focus was social justice and social change, not theoretical conceptualizations of urban poverty. In writing about Jane Addams and the Chicago School, Deegan (1990) stated that Addams wrote “all the book’s royalties would be waived as we have little thought about the financial gain” (57). Deegan goes on to argue that Addams’ interests were in “empowering the community, the laborer, the elderly and youth, women and immigrants” (255). Addams, similar to Dewey and later Freire, was also very critical of traditional education, which reproduced inequality. Deegan (1990) writes that Addams articulated a goal of “generating reflective adults” (283).

Definitions, Terminology, and Subdivisions

We have exemplars of the methods of participatory research and canons for their practice, even if we cannot as yet agree on a single name. — Couto (2003 , 69)

Clarification of terminology is necessary before beginning a discussion of the principles and skills of community-based research,. Broadly defined, campus–community research collaboration can be referred to as community-based research (CBR), community-based participatory research (CBPR), collaborative research, engaged scholarship, participatory research (PR), participatory action research (PAR), action research (AR), aboriginal community research, popular education, participatory rural appraisal, public scholarship, university–community research collaboration, co-inquiry, and synergistic research. New terms and subdivisions continue to emerge. Strand, Marullo, Cutforth, Stoecker, and Donohue (2003a) suggest that practitioners of CBR come “from within and outside academia and work in areas throughout the world—all of which makes any commonly-accepted definition problematic” (6).

It is not my intent here to minimize or ignore the different historical roots or traditions reflected in the above forms of campus-community research, but a discussion of the distinct nature of each is beyond the scope of this chapter. Acknowledging that there are differences, this chapter will focus on commonalities and core principles that can apply broadly to campus—community research partnerships. Generally, the term “community-based research,” or CBR, is used here, although I have tried to include the terms used by authors when describing their own research. Other scholars have also focused on similarities rather than differences. Atalay (2010) suggests that, “regardless of the terminology used, the central tents remain the same” (419). CBR aims to connect academic researchers with individuals, groups, and community organizations to collaborate on a research project to solve community-identified and community-defined problems. CBR is intended to educate, empower, and transform at the individual, community, and structural level to challenge inequality and oppression.

While using a broad brush to be inclusive of all campus–community research partnerships, it is important to address what I see as two important differences in the goals and outcomes within CBR. For many practitioners, the ideal is a long-term, collaborative, and egalitarian partnership that builds community, fosters transformation, and promotes social change. Academics conduct research with and for the community, and all participants teach and learn in a synergistic relationship. Clayton, Bringle, Senor, Huq, and Morrison (2010) argue that campus–community relationships can be short term (transactional) or, ideally, a partnership in which both parties grow and change because of a deeper and more sustained (transformative) relationship.

For others, (e.g., McNaughton & Rock, 2004 ; Nygreen, 2009 –2010) the relationship between academic researchers, the university, and the community is always contentious, and power is rarely equal. For this reason, some CBR practitioners advocate community members learn the skills and knowledge necessary to conduct their own research within their communities. Nyden, Figbert, Shibley, and Burrows (1997) write, “Participatory Action Research aims at empowering the community by giving it the tools to do its own research and not to be beholden to universities or university professors to complete the work” (17). Academic researchers within this tradition are looking to empower local communities to be researchers and authors of their own transformation. The goal is to foster self-determination and self-reliance of the disenfranchised and powerless so they can be self-sufficient ( Park, 1993 ).

From this perspective, a long-term or sustained partnership with academic researchers could be seen as exploitive and disempowering.

Another major difference is that. for many, the goal of CBR includes pedagogy ( Strand, 2000 ). CBR provides an opportunity to involve students in a research project with community partners, often as part of their curriculum requirement. Strand, Marullo, Cutforth, Stoecker, and Donohue (2003b , xxi) suggest CBR is a way to “unite the three traditional academic missions of teaching, research and service in innovative ways.” CBR as pedagogy can bring students together with faculty and community partners to address community problems, as well as learn valuable skills regarding democratic research processes, communication, and civic responsibility. Porpora (1999 , 121) considers CBR “the highest state of service learning” and important as a way to promote engaged citizenship among students. There is an extensive body of research discussing the benefits, challenges, and practice of CBR as pedagogy that has generally found substantial benefits to students.

What is meant by “community” within the term community-based research requires some clarification. Alinsky (1971 , 120) noted that “in a highly mobile, urbanized society the word ‘community’ means community of interest, not geographic location.” This suggests a collective identity with shared goals, issues, or problems, or a shared fate ( Israel, Eng, Schultz & Parker, 2005 ). This has been particularly evident in the growing number of international community–researcher collaborative partnerships. Pinto et al (2007) writes:

International researchers need to become members, even if from afar, of the communities that host their studies, so that they can be part of the interactions that affect social processes and people’s understanding of their behaviors and identities. These interactions may occur at physical, psycho-social and electronic levels, encompassing geographic and virtual spaces and behaviors, social and cultural trends, and psychological constructs and interpretations. [55]

Accepting that today individuals and groups can participate in numerous “communities of interest” at the local and global level, many exemplars of CBR are situated in geographically defined communities. The community, however, is rarely a unified or homogenous group. It often includes groups within groups, competing and contentious factions, and members with diverse perspectives, needs and expectations ( Atalay, 2010 ). The diversity of participants within CBR projects reflects both the strengths and the challenges of engaged scholarship and will be discussed later in this chapter.

A final clarification with regards to CBR is that it is not the same as community organizing or advocacy. CBR includes scientific investigation respecting research ethics, methodologies, and analysis. CBR practitioners and community partners are seeking knowledge and understanding through data collection and analysis. The findings will inform decisions as to community organizing, social action, or advocacy work. Fuentes (2009 –2010, 733) makes the distinction between “ community organizing ,” which usually focuses on the development and support of leaders and “ organizing community ,” which “centers on community building, collectivism, caring, mutual respect, and self-transformation.” CBR is about organizing community to create research partnerships to address inequalities. Another misconception is that CBR is a form of public service. Public service implies a one-way transfer of knowledge, expertise, and action from the campus to the community. CBR is a multi-directional process that results in shared and collaborative teaching, learning, action, reflection, and transformation.

We both know some things, neither of us knows everything. Working together, we will both know more, and we will both learn more about how to know. — Maguire (1987 37–38)

There is universal agreement that research is critical in terms of planning, implementing, and evaluating policies and programs. Nyden and Wiewel (1992 , 44) state, “research is a political resource that can be used as ammunition” to provide credible evidence regarding funding, programs, and or policy decisions. So why do CBR? For engaged scholars and activist working within a CBR paradigm, the reasons for doing so are numerous—personal and structural transformation, co-education, community empowerment, capacity building, and a belief in the need to democratize the research process. Even though engaged scholarship has not always been given the support and resources needed within academia, many argue that it is the only type of research that really makes a difference. Reason and Bradbury (2008) assert “indeed we might respond to the disdainful attitude of mainstream social scientists to our work that action research practices have changed the world in far more positive ways than conventional social science” (3). Rahman (2008) in summarizing the early work of Budd Hall in the 1970s states, “Participatory Action Research is a more scientific method of research because the full participation of the community in the research process facilitates a more accurate and authentic analysis of social reality” (51).

For many engaged scholars, ethical research requires working with and for individuals and groups, not doing research on or about subjects. Collaboration with multiple stakeholders allows for an opportunity to re-conceptualize problems and come up with innovative solutions. For many, this form of research is “more than creating knowledge; in the process it is educational, transformative and mobilization for action” ( Gaventa; 1993 ; xiv–xv). Community-based researchers acknowledge that this form of inquiry is not the only way, but often it is the best way to address the magnitude and complexity of contemporary social programs. It requires researchers across disciplines and from multiple perspectives, together with activists and community members, to join as equal partners and to think about and strategize solutions that are meaningful and beneficial to them. The benefits of combining scientific methods and lived experiences to re-conceptualize problems and find solutions are clear. Involving community stakeholders in all stages of the research process also increases the chances that solutions will be relevant and meaningful to community members. CBR is ideally situated to inform best practices as it is research generated from the ground up.

For more traditional social scientists, the reasons for considering CBR may reflect pressure from outside funders or community members. There has been a growing frustration with traditional research that the findings have not been applied or benefited the community or broader society. Nyden, Figert, Shibley, and Burrows (1997 , 3) state, “Traditional academic research has focused on furthering sociological theory and research” and not social action or social justice. Forty years ago, Fritz and Plog saw traditional research methods as no longer viable within archeology, stating:

We suspect that unless archaeologists find ways to make their research increasingly relevant to the modern world, the modern world will find itself increasingly capable of getting along without archaeologists. [ Cited in Atalay, 2010 , 419].

This concern has been raised within other disciplines and is reflected in the development of CBR and scholarship.

There are also very good reasons for institutions of higher education to align their mission to reflect a commitment to serve. Boyer (1994) suggests that the historical roots of higher education as a service to the community and a “public good” have diminished. He argues for the “New American College”—an institution that celebrates and fosters action, theory, practice, and reflection among faculty, students, and practitioners to solve the very real problems facing communities today. Colleges and universities must respond to and engage with communities to listen, learn, and work together on solutions. Netshandama (2010) describes how the University of Venda in South Africa changed over the course of four years to “align its vision and mission to the needs of the community at local, regional, national, continental and international levels” (72). Netshandama (2010) argues that the university did not just support faculty or add resources; their vision was to “integrate community engagement into the core business of the university” (72).

Methodology and a Transdisciplinary Paradigm

CBR is not a research methodology. Researchers and community members use a variety of methods to gather data about a community issue or problem and then seek solutions. It reflects a radical paradigm shift away from positivist methods of inquiry to what Leavy (2011) refers to as “a holistic, synergistic, and highly collaborative approach to research” (83). It can be best understood as a “ philosophy of inquiry ” ( Cockerill, Meyers, & Allman, 2000 ) or an “ orientation to inquiry ” ( Reason & Bradbury, 2008 ) that seeks to create participative communities of inquiry to collaborate to address community problems. Practitioners of CBR recognize and value multiple ways of knowing and do not privilege the knowledge or skills of the researcher over local experiences, skills, and methodologies. Torre and Fine (2011) suggest that PAR “represents a practice of research, a theory of method and an epistemology that values the intimate, painful and often shamed knowledge held by those who have most endured social injustice” (116). At its best, CBR reflects a democratization of the research process and a validation of multiple forms of knowledge, expertise, and methodologies. It is a shift away from research “subjects” to research collaborators and colleagues.

Although CBR is not a methodology, it does address the recent methodological questions concerning the role of “reflexivity” in research design and practice. Subramaniam (2009) states, “After adopting reflexivity as a valid research process, the researcher must make decisions about her status vis-à-vis those being researched and become conscious about their status in relation to her, the researcher” (203). This has led to further methodological questions concerning the validity of traditional binaries such as “researcher/researched,” “insider/outsider,” and “objective/subjective.” These statuses are addressed openly and critically in CBR projects. For example, critical psychologists often face an ethical dilemma when involved in CBR projects. Baumann, Rodriguez, and Parra-Cardona (2011 , 142) refer to this dilemma, citing the American Psychological Association (APA) Code of Ethics that states psychologists must refrain from “multiple and dual relationships with clients and community members.” For CBR practitioners, research is relational. Scientific “objectivity” is problematic and does not strengthen the validity of research outcomes.

CBR lends itself to mixed method design and often reflects a transdisciplinary research paradigm. According to Leavy (2011) , “Transdisciplanarity is a social justice oriented approach to research in which resources and expertise from multiple disciplines are integrated in order to holistically address a real-world issue or problem” (35). Leavy argues that “transdisciplanarity does not mean the abandonment of disciplines (34)” but rather knowledge gained through this form of inquiry transcends traditional disciplinary silos. I would agree that CBR reflects a “transdisciplanary research paradigm” and that this also includes community scholars outside academia.

Although data can result from many methods, there are core principles or tenets of CBR that are generally agreed upon by most practitioners. Scholars do disagree on the number of core principles. However, the unique nature of every CBR project allows for flexibility and differences. The principles represent guidelines or best practices, and are helpful for setting goals and for praxis,—continuous reflection, and action. They are also interconnected and interdependent. Each principle can be conceptualized along a continuum. For example, Schwartz (2010) suggests that PAR can include research that has minimal collaboration to projects that have full participation of all stakeholders in every stage of the research process with most projects falling somewhere in the middle.

Principles of Community-Based Research

Strand, Marullo, Cutforth, Stoecker, and Donohue (2003) suggested three core principles that define CBR: collaboration, democratization, and social action for social change and social justice. Atalay (2010) expands on these three and suggests five core principles of CBR: community driven, participatory, reciprocal, power sharing, and action oriented. As the number of community-based researchers, practitioners, projects, and disciplines involved has multiplied and the scholarship of CBR has increased, so have the number of core principles. Leavy (2011) suggests seven principles: collaboration; cultural sensitivity, social action and social justice; recruitment and retention; building trust and rapport; multiplicity and different knowledges, participation and empowerment; flexibility and innovation; and representation and dissemination. Still other practitioners have identified nine ( Puma, Bennett, Cutforth, & Tombari, 2009 ; Israel, Eng, Schultz, & Parker, 2005 ).

An understanding of the core principles that define CBR is important, but how each principle is negotiated and understood will reflect contextual, social, and historical differences within each project. Synthesizing and building on the work of others, I discuss seven principles of CBR that I believe represent best practices within this orientation to inquiry: collaboration, community driven, power sharing, a social action and social justice orientation, capacity building, transformative, and innovative. Summaries of CBR projects are also provided as brief case studies. They are intended to reflect the challenges and benefits of this work and how the principles of CBR are negotiated and reflected in unique ways.

Collaboration

Collaboration between the researcher and community is a fundamental principle of CBR. It is defined as working in partnership with all stakeholders to identify, understand, and solve real problems facing their community. Collaboration happens in all stages of the research process—including problem definition, methodological decisions, data collection and analysis, dissemination of the findings, and evaluation of the project. Collaboration between the researcher and the researched is a fundamental paradigm shift from the traditional scientific method. Within CBR, the distinction between the researcher and the researched is no longer valid or acceptable. This does not remove differences between stakeholders or between community members and researchers but rather recognizes and validates different ways of knowing, experiences, skills, and methods equally. Mandell (2010) states:

Ultimately, what the activist sociologist has to offer social change organizations is her or his detachment from the immersion in the work, grounding in social change theoretical perspectives and the power to ask questions and to make outside observations. The outsider perspective of an action researcher with the insider views of community partners makes for a powerful combination. [154]

To collaborate with community members it is critical that the project is transparent and inclusive of all stakeholders. It is a reflective process that continues throughout the project and is based on trust, respect, and equality between all participants. Mandell (2010) states that a “successful trust filled researcher-community partnership is built over time, through rigorous self-examination and regular communication” (154). Trust can often be fostered by researchers participating in additional community events and activities and by attending celebrations that are not directly related to the research project. Listening to and supporting participants ‘own professional and personal goals also fosters trust and builds collaboration ( Baumann, Rodriguez, & Parra-Cardona, 2011 ).

To foster collaboration, the researcher needs to understand some basic principles of group processes and group dynamics. CBR success depends on participatory democracy and open communication between members. This facilitates understanding and enables all members to share their strengths and skills, to set priorities, and to accomplish tasks. However, inclusivity and collaboration with multiple stakeholders can lead to questions about project size. Generally, large projects with multiple stakeholders can lead to hierarchies in decision making and discussion and may leave some voices silenced. Small projects with few members can lead to concerns about burnout and/or reinforcing power inequality within the community. There is no ideal size for maximum collaboration. Each project will need to negotiate and reflect upon collaboration and inclusivity in an ongoing dialogue or “multilogue” with the community. Sometimes community education about what CBR is may be necessary before collaboration is possible. This can add months or years to the expected timeline and may alter the original CBR project.

Case Study: A CBPR Project in Catalhoyuk, Turkey

Atalay (2010) was involved in an archeological excavation site in Catalhoyuk, Turkey, and wanted to include the community in a CBPR project. She stated that her first priority was to “[d]etermine if the community was interested in becoming a research partner, and what their level of commitment was. This required substantial up-front investment both to explain CBPR and to demonstrate how their role as collaborators would differ from their previous role as excavation labor or ethnographic informants” (422). In conducting interviews with local residents to invite collaboration, individuals felt they could not contribute to the research partnership until they received “archeology-based knowledge.” Atalay found that “contrary to what I had initially expected, the first several years of the project focused on community education rather than on developing and carrying out an archeology, heritage management or cultural tourism-related research design” (423).

The CBPR project started with archeology education that resulted in “an annual festival, archaeological lab-guide training for village children and young teen residents, a regular comic series (for children), and a newsletter (for adults)” (423). After some time, Atalay began moving the community towards a research partnership. The CBPR project initiated a local internship program and archeological theatre. Both were community-led and community-driven projects that fostered capacity-building and recognized the importance of local knowledge and experiences. Atalay acknowledged that the work was slow and did not take the direction she had initially intended. However, she argues that “collaborative research with communities in a participatory way offers a sustainable model, and one that enhances the way archeology will be practiced in the next century” (427).

This CBPR project illustrates that collaboration is only possible when partners are not only seen as equal by the researcher but when they experience it themselves. Freire (1970) reminds us we must always begin where the community is: “All work done for the masses must start from their needs and not from the desire of any individual, however well intentioned” (94). Atalay’s work also reflects the challenges and benefits of collaborative research partnerships. Problems and solutions are identified by the community and it is the community that is the primary beneficiary of the research project.

Community Driven

Classic social science research focused on social problems that the researcher and the academic community defined as important or worthy of study. Generally, a research project was initiated and controlled by the researcher. It was the researcher who benefited and subjects were often treated as objects. CBR was a response by engaged scholars and practitioners to end exploitive and oppressive research practices that left community problems intact, inequality unchallenged, and often community members feeling used. Ideally, community-based projects should be community driven from conception to dissemination of the findings and evaluation of the project. Comstock and Fox (1993) suggest that local communities and workplace groups should decide on the nature of the problem and participate in the investigation of local and extra-local forces sharing their lives. Collectively they may decide to take action based on the research findings.

However, Maguire (1987) suggest that “realistically, such projects are often initiated by outside researchers” (43). If many CBR projects do not originate within the community, how can practitioners and researchers foster community - driven projects? Whether the community is local or global, participants in CBR projects will often have conflicting interests, sentiments, expectations, and priorities. To be inclusive and have all stakeholders as participants in the research project means tension, conflict, and challenges are inevitable. Bowd, Ozerdem and Kassa (2010) remind us that:

Participation literature is also criticized for ‘essentializing’ the word community as a homogeneous entity where people have egalitarian interests to produce knowledge, work with partners and decide on matters of common good in undisputed manners. In reality however, communities are characterized by protracted ethnic, linguistic and professional cliques and interest groups. [6]

Engaged scholars and practitioners need practice, patience, skills, and knowledge to ensure all stakeholders are heard and encouraged to participate. Democratization of the research process requires participatory democracy within the community, and this cannot be expected or assumed.