Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony Essay

Beethoven’s Seventh symphony has no equal. The symphony is articulately arranged and established with unique flow of both chords and musical patterns. Listening to the seventh symphony one may note that the music is purely priceless; it is not an impersonation of someone’s ideas.

Thus, it can be argued that with its rich texture and timbre the symphony is exceptionally great. This illustrates that the seventh symphony is beyond any common explanation. The manner it stimulates thrills and captures the imagination of the listeners with its musical beauty and glory, it is awesome. The introduction, for instance, is developed and arranged in a manner that it strikes an addictive attention.

This can be allied to the manner the instruments have been arranged in order to synch with the tempo. More so, the symphony’s imposing orchestra chords, and the compliments of wind instruments such as oboe makes the symphony have a taste that is extremely majestic. Hence, the smooth ascendancy of its sonorities makes the symphony rhythm and movements have an effect that cannot be compared to any other symphony (Grove 80).

It ought to be noted that Beethoven gave the symphony its magnificent touch by establishing strong rhythms which are tied to the symphony’s themes. With the impact of individual dynamism the symphony is etched along the pillars of integrating diverse instruments with selected and tested alterations.

These measures seem to have aided the composer in developing the diverse elements which are apparent in the symphony. Consider the fact that the seventh symphony is almost without any elements of slow movement, yet its mood is extremely exuberant. Yet, it has less melody which is also complimented by less usage of strings.

From such a creative alteration of chord the symphony is equally propelled to its greater heights by the manner Beethoven injecting both major and minor chords interchangeably. Also, as the symphony gains in moment, it is evident that he introduced a new melody which is accompanied by dissimilar rhythm, bassoons as well as clarinets yet the temple and the pulse of the symphony remains intact.

More so, another notable feature of the seventh symphony is the way the diverse musical notes are exploited from a simple texture to the more complex key patterns we find the notes being craftily altered.

With the use of violin the symphony captures the imagination of orchestra lovers, while at the same capacity he sets motley of short notes against external rhythm of the symphony. And this established the allegretto movement in the composition (Steinberg 54). Subsequently, the arrangement of strings and the usage of G-sharp which is elaborately sustained by brilliant twining of horns, trumpets and other assorted instruments are superb.

What I have discovered is that the symphony has unique delay effect that is difficult to pick. This can be testified by the way singular octaves rise and drop creating a sublime melody. And this can be said to be the third feature that is unique to the seventh symphony. The instrumentation of this symphony indicates that it is divided into four major segments. Each segment is defined as a movement.

However, according to diverse music pundits the second movement which is popularly known as Allegretto is the most popular. Though, the symphony itself was developed with the core introduction being etched on the traditional orchestral traditions, it is no surprise that it has such a lengthy introduction, yet so impressive and aesthetically independent both in content and character and this separate the seventh symphony from the preceding symphonies.

It ought to be noted that it has definite and impressive structural design that can be said to be anchored within the range of C-major. And this makes the seventh symphony rhythmically a danceable piece. Note that, the rhythm is well tied to the entire instrumentation where the tempo is neither fast nor slow and this makes the entire piece to be a movement in the dancing context.

Thus,in exploring the entire configuration of seventh symphony we can argue that the arrangement sand the composition is total consigned to exposition which is equally transferred with dynamic transpositions. And this gives the symphony the movement depicted as allegro.

More so,the other factor is that the establishment of diverse tones ranging from the F-ajor scale with minor tones moving towards 6 th scale with the extent of A provides a sound explanation of symphonies tendency to move towards its unique simplicity which is in the domain of E, a dominant feature all through the symphony.

In essence, this establishes the symphony’s unique context both in presentation and performance. With unconventional method the tones,chords,harmonies as well as the tempo are all integrated to give the piece the unique timbre making the symphony danceable and equally enjoyable to listen, it has a smooth texture that is a product of harnessing the elements of treble G-major which happens to e the ultimate musical hierarchy.

The vivacity which is evident in tone and rhythm ascertains the symphony’s audacity and its splendid vitality. It ought to be noted that the manner the symphony transcends and descends is an ultimate score in symphonic movement.

With sustained chords, smooth flow of basses, violin and unassumed dominance-note- E establishes the resounding melodic tune swayed by elaborate accompanienment of D-major which is also supported by the home-keys. The seventh symphony can be said to be the genius composition by Beethoven in his earlier symphonies (Hopkins 155).

Beethoven Symphony Basics at ESM

General Information

Composition dates: 1811-12.

Dedication: Count Moritz von Fries ( portrait ).

Instrumentation: Strings, 2 Fl, 2 Ob, 2 Cl, 2 Bsn, 2 Hn, 2 Tr, Timp.

First performance: 8 Dec. 1813, Akademie at University Concert Hall, Vienna.

Orchestra size for first or early performance: 13+12.7.6.4/single winds (estimated, based on Beethoven letter).

Autograph Score: Biblioteka Jagiellońska, Kraków. Biblioteka Jagiellońska website.

First published parts: Dec. 1816, S. A. Steiner & Co., Vienna.

First published score: Dec. 1816, S. A. Steiner & Co., Vienna. SJSU Link.

Movements (Tempos. Key. Form.)

I. Poco sostenuto (C, MM=69)—Vivace (6/8, MM=104). A Major. Sonata-Allegro (w/ slow intro.).

II. Allegretto (MM=76). A Minor (i). Ostinato variation (developing, passacaglia) with fugato.

III. Scherzo (Presto, MM=132)/Trio (Assai meno presto, MM=84). F Major (VI). Scherzo/Trio (ternary extended)

IV. Finale. Allegro con brio (2/4, MM=72). A Major. Sonata-Allegro, with hints of Rondo.

Significance and Structure

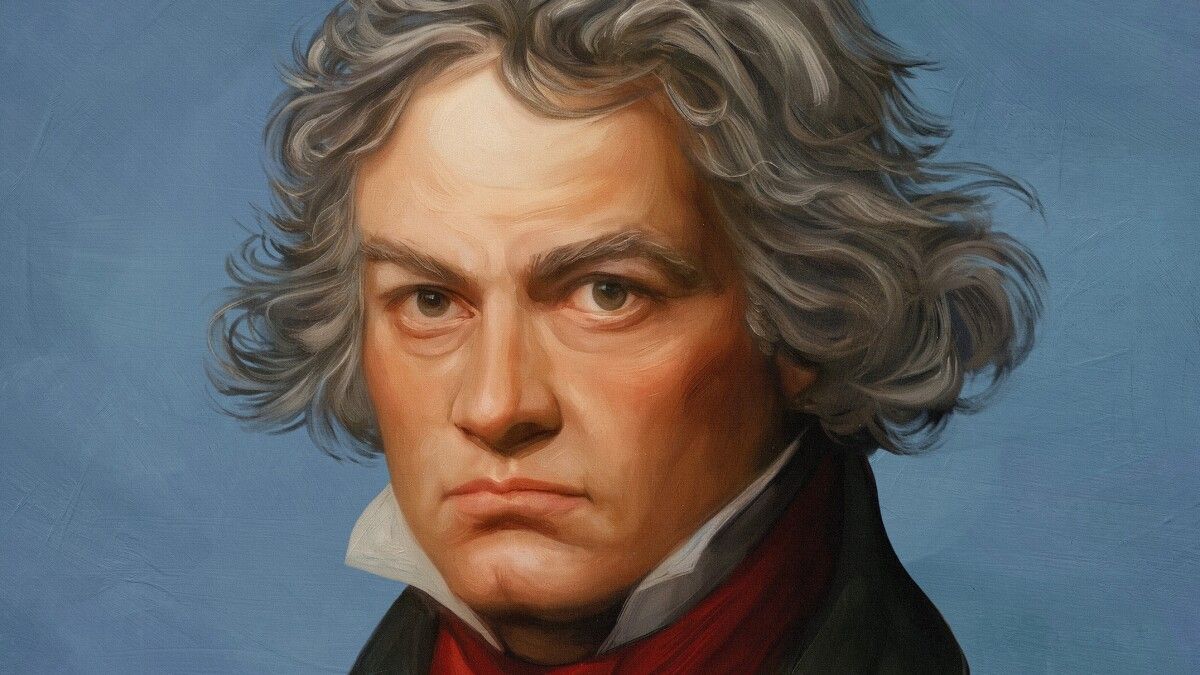

Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7 in A, Op. 92 was composed in 1811-12, more than three years after the premiere of the Fifth and the Sixth Symphonies. Although Beethoven did not compose any symphony during the intervening years, he remained productive in other genres, especially keyboard and chamber music, and produced some of his most important works, including the “Emperor” Piano Concerto , the “Lebewohl” (Farewell) Piano Sonata , and the “Archduke” Piano Trio . The vacancy of symphonic work did not imply that Beethoven was no longer interested in being publicly recognized as a symphonic composer (Lockwood, Beethoven’s Symphonies , 146). In 1809, he noted some short ideas marked “Sinfonia” in his sketchbooks, though some of them were not used in the later symphonies. Beethoven finally started working on the A major Symphony in earnest in the fall of 1811 in the Bohemian spa town of Teplice, where he had travelled to improve his health, and completed it in April 1812.

The Seventh Symphony was premiered in the great hall of the University in Vienna on December 8, 1813, as part of a charity concert for soldiers wounded in the Battle of Hanau . This concert was probably the most successful in Beethoven’s lifetime. The program also included the first performance of the “Battle Symphony” Wellington’s Victory , an anti-Napoleon patriotic showpiece which celebrated the British victory over the French at the Battle of Vitoria in Spain (Steinberg, The Symphony: A Listener’s Guide , 38-43). Unlike some of Beethoven’s other symphonies such as the Third and the Fifth, which we now regard as great works but were initially resisted to some degree by the composer’s contemporaries, the Viennese audience immediately embraced the Seventh Symphony, and considered it among their favorite orchestral works. Its huge popularity led to three performances in the ten weeks following its premiere. The second movement—Allegretto—was particularly loved, leading to outbreaks of applause before the third movement during a number of early performances. The Allegretto remained widely popular throughout the nineteenth century, and even today is often performed separately. According to a reviewer three years after the first performance, “the second movement…which since its first performance in Vienna has been a favorite of all connoisseurs…is still demanded to be repeated at every performance.” (Lockwood, Beethoven’s Symphonies , 159.) Not only did the audience enjoy the “rustic simplicity” of the work, the artistic value of the Seventh Symphony was also well-received by critics and composers such as Hector Berlioz who considered it “a masterpiece – alike of technical ability, taste, fantasy, knowledge, and inspiration.” (Lockwood, Beethoven’s Symphonies , 166.)

What has made the Seventh Symphony exceptional in the minds of critics since its earliest performances is its rhythmic vitality and momentum. Richard Wagner exalted the lively rhythm with this often-quoted poetic description:

All tumult, all yearning and storming of the heart, become here the blissful insolence of joy, which carries us away with bacchanalian power through the roomy space of nature, through all the streams and seas of life, shouting in glad self-consciousness as we sound throughout the universe the daring strains of this human sphere-dance. The Symphony is the Apotheosis of the Dance itself: it is Dance in its highest aspect, the loftiest deed of bodily motion, incorporated into an ideal mold of tone.

As Lockwood says, the rhythmic events are so strong that they sometimes overshadow other musical elements. (Lockwood, Beethoven’s Symphonies , 151.) But this rhythmic vitality is one characteristic of a larger factor that may account for the Seventh Symphony’s appeal to audiences who may have no training in music: its rusticity suggesting folk music. Lockwood goes on to say that Beethoven’s 6/8 theme in A major in the first movement reminded the listeners of Scottish and Irish folk songs. (Lockwood, Beethoven’s Symphonies, 166-167.) Colorful orchestration that favors woodwind solos and horn calls, particularly in the first and last movements, also serves the rustic character. This more Romantic orchestration is a long way from the criticism “too much of Harmoniemusik ” leveled at the “classical” First Symphony. (See Symphony No. 1 “Others’ Words” essay. )

The rhythmic vitality and simple rustic character cover an unusual choice of key layout for the movements. Rather than using a relative minor key or keys that are related by a fourth or fifth, Beethoven chose to exploit keys separated by a third, particularly between the inner movements. The second movement is in A Minor and the third movement is in F Major, with the trio in D Major. These third-related keys, and the rustic character supplied by woodwinds, are foreshadowed in the slow introduction of the first movement. The key of A Major is the first chord of the symphony, but the opening moves throughout various keys, such as C Major, led by the oboes , and F Major, led by the flutes , until orchestral arrival on the dominant E Major. The home key of A Major is not clear until the fifth measure of the Vivace section (3:33-3:59), with the flutes introducing the principal melody.

[We refer the reader to the following recording for the ensuing discussion: Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Iván Fischer, conducting, Beethoven: Symphony No. 7. ]

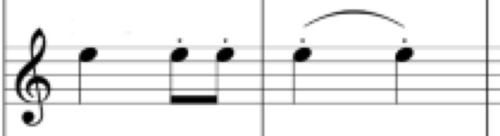

The first movement opens with the longest introduction (0:03-3:50) of any of Beethoven’s symphonies. As in earlier opening-movement slow introductions, Beethoven brilliantly outlined important key areas, and highlighted scalar and chromatic motives found throughout the rest of the first movement. The harmonic movement of the introduction mirrors fundamental key areas in each of the four movements, specifically: A major (first and last movement)—D major (trio of the third movement)—C major (second movement, B theme)—F major (third movement)—E major (beginning of the fourth movement) . Following the introduction, the first movement Vivace moves forward with an unrelenting rhythmic motive (3:50-3:55):

Rarely does this rhythmic figure cease, only doing so in order to create moments of great anticipation. These characteristic Beethovenian moments of dramatic, blaring silences give way to major changes in the music, such as signaling structural changes in moving to the development section (8:23-10:32) and the coda (12:51-14:19), where rising chromatic figures suddenly stop before falling into the next section (8:23-8:34, 12:51-12:57). Chromaticism is the third defining feature of the first movement. As with the use of silences, ascending and descending chromatic lines, often in the bass, lead towards and away from the different sections and key areas. Beethoven perfectly bookends the sonata form of the first movement with its introduction and coda, balanced at exactly 62 measures each. The exposition and recapitulation, being 114 and 115 measures respectively, also balance around a lengthier developmental center of 97 measures.

The second movement— Allegretto (14:43-24:08)—pulls back the frantic rush of the first movement into a melancholy march with a dramatic shift to the parallel key of A minor. The movement has been a favorite since its premiere in 1813, with early audiences often demanding encores before continuing on to the remaining movements. Its appeal could possibly be due to Beethoven’s ingenuity in combining simple melodic lines, a consistent rhythmic motive, and unexpected harmonies, to draw the listeners into an aural journey of their own imagination. The movement’s structure can be seen as a modified rondo or a hybrid between a theme and variations and a ternary form , with the outer sections carrying the theme and its variations, and the middle section providing a countering wistful themes in A major (18:19-19:38). Not content with only creating simple variations on the theme, Beethoven further developed the theme by turning it into a fugue. Like the first movement, the second movement features a rhythmic motive that is consistent throughout (14:48-15:41):

This rhythm ties the two harmonically and melodically disparate sections together with its steady, plodding pace. Also related to the first movement, Beethoven used ascending and descending chromatic lines, but here in the melody of the theme and variation, as heard here (15:43-16:33) played by the cellos and violas. After repeating the primary and secondary sections twice, the movement is brought to a close by returning to the main theme while gradually thinning out the orchestration and breaking apart the rhythmic motif, not unlike the end of the Marcia funebre movement of the Eroica Symphony. The movement ends the way it began: a fading A-minor chord in winds with an abundance of the pitch e (23:57-24:08).

The e of the last chord of the Allegretto movement moves up to an F-major chord to begin the third-movement Scherzo (24:30-33:52), the longest of any symphonic scherzo Beethoven had yet composed (the scherzo of the Ninth Symphony would eclipse it). While traditional key relationships in major symphonies focused on the dominant and subdominant relationships, Beethoven frequently preferred to explore third-related keys. The abundance of e in the last a-minor chord of the previous movement effectively serving as the leading tone moving up to the f major chord of the third movement neatly accommodates this mediant-key relationship. In the most general terms, the Scherzo alternates between a frolicking Presto (24:30-26:57) and the more relaxed yet majestic Trio (26:57-29:22) marked Assai meno presto (“very much less quick”). The faster sections have all of the trademarks of a scherzo—a fast tempo, irregular phrase lengths, and misplaced accents. There are two main melodic elements of the opening : an ascending third, stated first in unison by the strings and woodwinds and later passed around in dialogue, and descending scalar patterns, perhaps reminiscent of the scalar passages prevalent in the slow introduction of movement one. Beethoven expanded the global form of the traditional scherzo by repeating the Trio, creating an extended ternary form of ABABA, as in his Fourth and Sixth Symphonies. One of the most humorous gestures of this movement is Beethoven’s use of a repeated two-note descending gesture (29:46-30:02). The motive is stated by different parts of the orchestra, creating a trance-like effect that is broken up by a fortissimo outburst. In the second repetition of the Scherzo, the outbursts are supplanted by soft arrivals, making their return in the final repetition ever-more satisfying. Many believe that the Trio borrows material from an Austrian folk tune, which supports the symphony’s folksy character. It opens in D Major with horns, clarinets, and bassoons ( Harmonie ) playing a simple theme over an insistent dominant pedal tone (30:43-31:22). Energy builds gradually as the orchestration and dynamics grow until the entrance of the timpani announces the climax. As mentioned above, the Trio is repeated in full and, in one last humorous touch, Beethoven begins it a third time at the end of the movement, only to rapidly squelch it with a loud cadential explosion (33:35-33:52).

Reversing the move from the second to the third movement, the F-major ending of the Scherzo falls back to e-heavy stentorian sonorities as the dominant of the return to A major, punctuated by full measures of silence, open the finale movement (34:08-end). This creates a sublime effect and signals that this movement will offer no repose from the driving rhythmic intensity of the earlier movements. Several commentators on the fourth movement have rightfully characterized it as “bacchanalian.” Its driving rhythmic energy almost compels listeners to rise to their feet, recalling Richard Wagner’s quote that this symphony was “the apotheosis of the dance.” Indeed, this movement is a lively contredanse . The first theme is driven forward by sforzandi on the second beat of each measure until the stymied resolution to tonic is achieved in measure twelve. The movement continues in a sonata-rondo form , momentum building with each return of the refrain. Driving dotted rhythms (35:01-35:18) give way to the second theme, which unfolds not in the dominant but in C-sharp minor, another mediant-key relationship. The development section travels even further afield from the home key, visiting C major and F major (both present in the slow introduction of the first movement) and finally to the extremely distant B-flat major, before the recapitulation firmly returns in the tonic key. As in previous symphonies, the coda serves as another opportunity for development by exploring various key areas. A very long dominant pedal emerges (40:10-40:19), growing to a marking of fff, the first marking of its kind in Beethoven’s symphonic oeuvre. Retrospectively, the finale is relentless exercise in exuberant energy and forward momentum.

— Contributors : CH, FJ, JM, YLiu, MER

Beethoven’s Words

“At my last concert in the large Redoutensaal there were 18 first violins, 18 second, 14 violas, 12 violoncellos, 7 contra-basses, and 2 contra-bassoons.” Beethoven memorandum regarding the 27 December 1814 Akademie at the Redoutensaal, noted by Schindler to have been among Beethoven’s possessions. The Akademie included, along with the performance of Symphony No. 7, the first performance of Symphony No. 8, and Wellington’s Victory , and is reported to have had 3000-5000 in attendance. (Thayer, Life of Beethoven, 576.)

Großer Redoutensaal, c.1760. Wedding of Joseph II to Princess Isabella of Parma. Painting by Martin van Meytens, 1763.

The premiere concert of the Seventh Symphony in 1812 was a huge success. After the 1808 premiere of the Fifth and Sixth Symphonies, Beethoven ceased composing symphonic works for a few years, spending the time composing in other genres and reconsidering the symphonic genre. Symphonic work was still Beethoven’s “strongest ambition” (Lockwood, Beethoven’s Symphonies, 148), and this long pause gave Beethoven a good opportunity to continue to stretch the dramatic possibilities of the genre. His sketchbooks from this period show an abundance of ideas for symphonic works, and although not all of them resulted in complete works, they show that Beethoven continued exploring this genre.

After this dormancy, and with Wellington’s defeat of Napoleon at the Battle of Vitoria fresh in the minds of the Viennese, Beethoven started to compose the Seventh Symphony. The long period of thoughtful study and planning Beethoven undertook for the new symphony bore marvelous fruit. Its energetic character and magnificent orchestral sonorities prompted a vibrant reaction from the audience of the first performance, and even more from the exceptionally large audience described by Beethoven in the above quote. Beethoven himself was very satisfied with this newly composed work, calling it his “most excellent symphony.” (Schwarm, Symphony No. 7 in A Major, Op. 92 , 1.). One music critic said this symphony “is the richest melodically and the most pleasing and comprehensible of all Beethoven symphonies.” (Schwarm, Symphony No. 7 in A Major, Op. 92 , 1.)

The Großer Redoutensaal where the concert took place was located within the Hofburg palace , home to the Hapsburg dynasty, in the heart of Vienna. At the time of this concert in 1814, the Redoutensaal was the largest concert hall in Vienna. (Harrer, Musical Venues in Vienna, Seventeenth Century to the Present, 84. ) Beethoven was struggling financially during these years; the Austrian currency had been devalued as a result of the war, and Beethoven was receiving less from his patrons than had been promised to him. With the popularity of the Seventh Symphony already ensured because of its first performance, Beethoven would have appreciated the possibility of additional ticket sales and increased patronage the such a large hall offered. Furthermore, the size of the Redoutensaal well-accommodated the inordinately large orchestra Beethoven described, which surely would have given the audience a uniquely overwhelming experience.

Early performances of Beethoven’s first six symphonies used a string section one typically now associates with performances of works by Mozart and Haydn, with 6-8 first violins, 6-8 second violins, 3-4 violas, 2-4 cellos, and 2-5 basses. (Ruhling, The Classical Orchestra, 12.) Beethoven’s own memorandum on the 1814 concert relates that for this performance of the Seventh Symphony the string section was heavily expanded, and the mention of two contrabassoons suggests that not only were the winds doubled in tutti sections for such a large string contingent, but that their listing along with only the strings probably means the contrabassoons were used to reinforce the double bass parts. (Ruhling, The Classical Orchestra, 14.) The use of such a large string section may have been a result of the instrumentation required by Wellington’s Victory , which called for extra wind and brass instruments including six trumpets, four horns, and a large percussion battery, even muskets and artillery. This expanded orchestra would have given profound life to the colorful instrumentation and vibrant rhythms of the Seventh Symphony as well, and may have influenced Beethoven and other composers to explore even further the dramatic potential of the orchestral ensemble, leading towards what would later be considered a Romantic aesthetic. Consider the implications a string section of this size and the possibility of double winds would have from the very first bar of the symphony, with forceful tutti downbeats juxtaposed with a solitary oboe line, or with the arrival of the first theme in the full, tutti orchestra , after being presented by a single flute in a piano dynamic. The overwhelming jubilation and raucous character of the contredanse in the fourth movement would have only been increased by such a large orchestra, not to mention the mountainous fff at the end of the fourth movement . As a whole the symphony is full of moments of powerful tutti exclamations followed by soft solo sections , or even silences . This insertion of silence is even more striking on the 1814 audience when considering the effect in a hall the size of the Großer Redoutensaal itself, with a decay estimated at of 1.4 seconds. (Harrer, Musical Venues in Vienna, Seventeenth Century to the Present, 84. )

Discussion of Beethoven’s symphonies often focus on his communication of the sublime along with universal topoi relating back to humanity. This is sometimes lost in commentaries of the Seventh Symphony, which tend to focus on its omnipresent rhythmic character. This quote, however, brings our focus back on Beethoven’s use of the orchestra, and reminds us of his continual reconsideration of the endless dramatic possibilities of symphonic music, particularly pushing it towards monumentality.

— Contributors : EH, WZ, MER

Others’ Words

“The new symphony [No. 7 in A] was received with so much applause again. The reception was as animated as the first time; the Andante [second movement Allegretto] the crown of modern instrumental music, as at the first performance had to be repeated.” Reviewer of AMZ regarding the Seventh Symphonies second performance on February 27, 1814, on a concert with the Eighth Symphony and Wellington’s Victory . (Thayer, Life of Beethoven, 575.)

Beethoven completed the Seventh Symphony in 1812, after more than three years had passed since his Fifth and Sixth Symphonies were published in 1808. The above quote by a reviewer of the 1814 performance suggests that the symphony continued to astound audiences well after its first performance in 1812. The material such as scales, and melodies that outline common chords, described by some critics as having a “rustic simplicity,” must have been part of its noteworthy appeal. Additionally, the brilliant orchestration that favored woodwind colors, particularly the first-movement flute and oboe solos, and high horn calls of the first and last movements, further conveyed the rustic character. Berlioz notes this, stating, “I have heard this theme [the principal theme of the first movement] ridiculed for its rustic simplicity. Had the composer written in large letters at the head of this Allegro the words Dance of peasants , as he has done for the Pastoral symphony, the charge that it lacks nobility would probably not have been made.”

Lewis Lockwood speculates that some of the rhythmic and melodic aspects of this symphony related to Scottish, Irish, and Welsh folk-song traditions, themselves considered “rustic” by the Viennese. (Lockwood, Beethoven’s Symphonies , 166-67.) For example, the A major principal theme of the first movement emphasizes downbeats of the first two measures using grace-notes, and the fourth bar begins with a “ Scotch snap , “ reminding listeners of the melodic style of Scottish and Irish folk songs. Another example is in the finale, as Lockwood points out: “A connection between the Seventh Symphony and his folk-song setting is not just a matter of metrical identity, but is also shown by a direct melodic correspondence between the postlude to one of his Irish songs [“Save me from the grave and wise,” WoO 154/8] and the main theme of the finale of the Seventh.” (Lockwood, Beethoven’s Symphonies , 167.)

The finale opens with two roaring gestures with each followed by a full measure of silence, making clear that there will be no slackening that the driving rhythms that have directed the work so far. As Lockwood wrote, “Tovey called this movement ‘a triumph of Bacchic fury,’” (Lockwood, Beethoven’s Symphonies , 165), and this finale overwhelms the audience with never-ending forward momentum as much as any Beethoven had written to date. Just as Berlioz said, “Beethoven did not write music for the eyes . The coda, launched by this threatening pedal , has extraordinary brilliance, and is fully worthy of bringing this work to its conclusion – a masterpiece of technical skill, taste, imagination, craftsmanship and inspiration.”

The second movement received special attention when it premiered and became an audience favorite quickly. It was so popular that a Leipzig critic, who attributed the lack of enthusiasm from the audience for the Eighth Symphony to the lingering admiration for the Seventh Symphony performed right before, called the second movement the “crown of modern instrumental music.” (Thayer, Life of Beethoven, 575.) What made it the crown of modern instrumental music? The first ten measures of this movement have few melodic or harmonic elements, with only a few notes repeated throughout, and no notable harmonic progression nor contrapuntal elements. The familiar long-short-short-long-long rhythm (see above essay “Significance and Structure”) that carries the almost divine selection of notes is one of the features that generated a strong, stirring effect that perhaps reminded the audience of the powerful Funeral March in the Eroica . Lockwood speculates that Beethoven was well aware of the dramatic effects a slow march tempo might have on audiences, having composed marches for the Austrian army between 1809 and 1816. (Lockwood, Beethoven’s Symphonies , 161.) Given that the Viennese audience had been familiar with military marches from decades of war, it was perhaps inevitable that the second movement was received with such enthusiasm. But it continued to draw attention well after the immediate pain of the Napoleonic wars were forgotten. Leonard Bernstein , in an interview given by Maximillian Schell, commented: “[in the opening of the 2nd movement of the Seventh Symphony] there is no aspect of Beethoven in which you could say that Beethoven is great as a melodist, harmonist, contrapuntist, or tone painter. . . .” Bernstein goes on to say that Beethoven showed ingenuity in constructing the form, always choosing the right note to succeed every other note as though “he had some private telephone wire to heaven which told him what the next note had to be.” The right note? Consider the viola’s note e that sits on the repetitive rhythmic pattern in the opening and the subsequent development. In the final analysis it is perhaps this one note that is the seed that grew into the captivating music which the Leipzig critic labelled “the crown of modern instrumental music.”

— Contributors : MCho, YS, MER

Topics and readings for further inquiry

The Redoutensaal and Other Performance Venues in Vienna Harer, Ingeborg. “ Musical Venues in Vienna, Seventeenth Century to the Present .” Performance Practice Review 8, No. 1 (1995), accessed July 30, 2020. A brief but thorough review of performance venues in Vienna and their use throughout the seventeenth century to present day.

Beethoven as a Concert Organizer “ Beethoven as a Concert Organizer .” Beethoven-Haus Bonn, accessed 07/30/2020. A brief discussion of Beethoven’s public concerts organized by Beethoven in Vienna.

Beethoven and Orchestration Botstein, Leon. “Sound and Structure in Beethoven’s Orchestral Music.” In Glenn Stanley, ed., The Cambridge Companion to Beethoven . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. Available online through CambridgeCore .

Online Resources

Early Editions of Score and Parts Copyist’s manuscript

Autograph sketches at the Morgan Library & Museum

First published score: Dec. 1816, S. A. Steiner & Co., Vienna

Modern Edition of the Score New York Philharmonic score with annotations from Leonard Bernstein.

Dover edition (reprint of Henry Litolff’s Verlag, n.d., ca.1880)

Recordings available online Period/HIP Performances— Chamber Orchestra of Europe, Harnoncourt 1st movement , 2nd movement , 3rd movement , 4th movement

Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique, Gardiner 1st movement , 2nd movement , 3rd movement , 4th movement

Orchestra of the 18th Century, Brüggen 1st movement , 2nd movement , 3rd movement , 4th movement Complete Set of Beethoven Symphonies by Orchestra of the 18th Century and Brüggen

Important Recordings by Modern Orchestras— Albert Coates conducting the London Symphony Orchestra (1921) One of the first, if not the first, recording of the Seventh Symphony ( link ).

Carlos Kleiber conducting Concertgebouw

Bernstein conducting Vienna Philharmonic

Claudio Abbado conducting Vienna Philharmonic

Herbert von Karajan conducting the Berlin Philharmonic

Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Beethoven: Symphony No. 7 Includes two video performances by the Concertgebouw Orchestra, with or without commentary by conductor Iván Fischer.

Descriptions available online (videos, program notes, etc.,) Bernstein & Vienna Philharmonic commentary .

Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Beethoven: Symphony No. 7 Includes two video performances by the Concertgebouw Orchestra, with or without commentary by conductor Iván Fischer. Additional program notes here .

Berlioz, A Critical Study of Beethoven’s Nine Symphonies , p. 83: digital scan of printed version , web version .

Steven Ledbetter, Aspen Music Festival Program Notes Quotes memoir of Beethoven’s conducting during its rehearsal.

Christopher Gibbs, NPR: Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7 in A Major, Op. 92 Includes interview with conductor Christoph Eschenbach.

Michael Steinberg, San Francisco Symphony Program Notes

Marianne Williams Tobias, Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra Program Notes

Ken Meltzer, Atlanta Symphony Program Notes

Interview with Leonard Bernstein. Discussion with Maximillian Schell on the second movement with demonstration at the piano.

Sean Rice and Alexander Shelley, National Arts Centre: Exploring Beethoven Symphonies No. 7, 8 and 9

Wikipedia analysis

ESM Quick Links

- Eastman Journal

- Community Engagement

- Offices & Services

Read Eastman Notes Back Issues

- Eastman School of Music 26 Gibbs St. Rochester, NY 14604

- 585-274-1000

- Directions and Parking

- Questions and Comments

© 2024 University of Rochester. All rights reserved.

- Our Insiders

- Choral & Song

- Instrumental

- Great Recordings

- Musical terms

- TV and Film music

- Instruments

- Audio Equipment

- Free Download

- Listen to Radio 3

- Subscriber FAQ

- 2023 Awards

- 2024 Awards

A guide to Beethoven's Symphony No. 7

We investigate Beethoven's Seventh Symphony and how the composer declares the 'glory of light' through darkness

Stephen Johnson

Vienna, 8 December 1813

After the titanic adventures in sound-colour, form and dramatic expression of Symphonies Nos 5 and 6, the Seventh might initially seem a return to safer, more classical ground. Except that Beethoven doesn’t really do ‘safer’ – not by this stage in his career, anyhow.

Madness and rhythmic patterns:

Composed after a much-needed restorative spa holiday in 1811, Symphony No. 7 sounds like what Beethoven would later call a ‘return to life’. The key of A major is often associated with light and buoyancy (Mendelssohn’s Italian , Schubert ’s Trout Quintet), but here the sheer physical energy – expressed in dancing muscular rhythms and brilliant orchestration – can, in some performances, border on the unnerving. Confronted with one particularly obsessive chain of repetitions (possibly the spine-chilling final crescendo in the first movement), Beethoven’s younger contemporary Carl Maria von Weber pronounced him ‘ripe for the madhouse’.

But there’s nothing mad about the way Beethoven draws together the seemingly diverse dance rhythms in this work. Just over a minute into the substantial slow introduction, the woodwind intone a rhythmic pattern: DA de-de – in classical metric terms, a ‘dactyl’.

This same pattern pulses expectantly in the audacious sustained one-note transition to the Vivace , then springs to life in its main theme. The wonderful veiled Allegretto that follows is haunted by the same rhythm, the Trio of the scherzo repeats it like a playground game, while the finale is positively possessed by it, right up to the ferocious elation of the final bars.

- A guide to Beethoven's Symphony No. 5

- Beethoven's Symphonies: What did the 9th century think?

Just before the end, for the first time ever in an orchestral work, Beethoven uses the marking fff – fortississimo : ‘louder than as loud as possible’. There are times listening to this astonishing finale that one wonders if it wasn’t here that Stravinsky got the idea for the ‘Sacrificial Dance’ from the Rite of Spring – except that it is life, not death, that triumphs.

It isn’t all joyous assertion, of course. Like TS Eliot, Beethoven realised that it is darkness that ‘declares the glory of light’. The voluptuous nocturnal world of the Allegretto opens on a minor-key wind chord which, after the glowing A major that ends the first movement, feels like the deft extinguishing of a light.

Beethoven expands his tonal universe as never before in a symphony, allowing the bright A major to be continually undermined by a remote (and, in context, darker) F major – if that sounds technical, the effect in performance is fully visceral. But ultimately, the Seventh Symphony is testimony to Beethoven’s enduring ability to find energy and hope amidst inner and outer desolation, and as such it’s indispensible.

- A guide to Beethoven's Symphony No. 2

- How did Beethoven cope with going deaf?

Recommended recording:

Riccardo Chailly achieves the near-impossible, combining the classicising insights of period-style performers with the tonal richness and expressive gravity of old-school master interpreters such as Otto Klemperer or Carlos Kleiber. The rhythms are crisp and vital, the colours gorgeous, the expression intense and broad-ranging, and all is captured in superb recorded sound.

Gewandhausorchester Leipzig/Riccardo Chailly Decca 478 3496

Words by Stephen Johnson. This article first appeared in the December 2015 issue of BBC Music Magazine.

Read reviews of the latest Beethoven recordings here

Share this article

Journalist and Critic, BBC Music Magazine

- Privacy policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Cookies policy

- Manage preferences

Home — Essay Samples — Entertainment — Ludwig Van Beethoven — An Examination Of Symphony No. 7 In D Minor Op 92 Of Ludwig Van Beethoven

An Examination of Symphony No. 7 in D Minor Op 92 of Ludwig Van Beethoven

- Categories: Ludwig Van Beethoven

About this sample

Words: 661 |

Published: Mar 14, 2019

Words: 661 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Week Six Essay

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Entertainment

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 705 words

1 pages / 605 words

2 pages / 976 words

2 pages / 823 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Ludwig van Beethoven is widely regarded as one of the greatest composers in the history of Western classical music. His life and work have left an indelible mark on the world of music, and his influence can still be felt today. [...]

Budden, J. (2018). Beethoven: The Man Revealed. Yale University Press.Cooper, B. (2020). Beethoven. Oxford University Press.Lockwood, L. (2003). Beethoven: The Music and the Life. W. W. Norton & Company.

Ludwig van Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 in D Minor Op. 125 is a symphony unlike any other. This piece of music explores innovations in a vast array of characteristics and style techniques which brings universal appeal among [...]

German composer Ludwig van Beethoven was born on December 16, 1770, at Bonn, Germany and died on March 26, 1827, at Vienna, Austria. Beethoven is the most famous composer in the history of music. He continued to his career to [...]

Beethoven was a great composer during his time. Beethoven, or his full name, Ludwig van Beethoven was born in Bonn, Germany in December 1770. He was baptized on 17 December and his birthplace now is known as Beethoven-Haus [...]

Ludwig van Beethoven was born in December of 1770 in Bonn to parents Johann and Maria, who were excited and scared about the future of their newborn son. In his early 30s, he started losing his hearing and was completely deaf by [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7 in A major, Op. 92

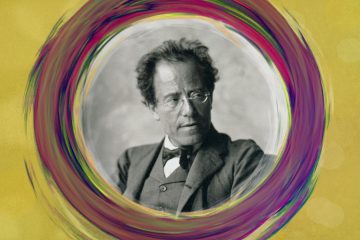

Portrait of Beethoven, by Joseph Willibrord Mähler in 1815

Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7 was composed in 1812, four years after his “ Pastoral ” symphony. What’s extraordinary about this work, in Sir George Grove’s words, is in “the originality, vivacity, power, and beauty of the thoughts, and in a certain romantic character of sudden and unexpected transition which pervades it.” [1] And one of the key characteristics that contribute to the “vivacity” and “power” here is its heavy use of rhythmic devices. To be completely honest, in the early years of listening to this piece, the endless and seemingly obsessive repetition of those rhythmic motifs throughout each movement sounded a bit annoying to me. It may be because, on a subconscious level, I was drawing contrasts between this work and all of Beethoven’s previous symphonies, which almost all carry memorable tunes and melodies, not to mention its immediate predecessor, the Pastoral symphony, of which the whole musical meaning builds on melodic motifs and phrases to express his feelings while submerging himself into the beauty of nature.

In the Seventh, however, such melodic features, if exist at all, are pushed (maybe deliberately) to the far back of Beethoven’s focus. In his conversation with Maximilian Schell, Leonard Bernstein didn’t consider the opening bars of the 2nd movement a legitimate melody at all (10 bars into the opening we hear only two notes) [2] . But, what makes this work unique (even peculiar) is it’s rhythmic features, with the general characteristics of the rhythms being incessantly forthcoming, fast and fiery. Lockwood stated that in the Seventh, “rhythmic consistency governs even more pervasively than in most of his other works…the streaming flow of rhythmic events … animates the discourse at every level and becomes a principal source of its organic unity.” [3]

1. Poco sostenuto - Vivace

Throughout the entire movement, the dance-like dotted rhythm in 6/8 meter permeates all the sections of its Sonata form, therefore produces this unstoppable energy that propels the

It is considered unusual for Beethoven to write first movement of his symphony in a fast 6/8 meter, and it’s incessant rhythmic power simply makes it a bold move compared to his previous symphonies.

2. Allegretto

Similar like the first movement yet in a relatively slower tempo, this movement’s opening also starts with a steady rhythmic pattern, played first by violas and cellos:

As the main subject develops, part two of the main subject (I-b) grows stronger and more prominent, then Beethoven threw in a short fugue on the subject, before the full force of the orchestra repeats it and ends the movement.

3. Presto – Assai meno presto

That sense of contradiction grows stronger when for the second round the strings takes over the melody, and the trumpet now holds the long note.

4. Allegro con brio

[1][4][5] George Grove: Beethoven’s Nine Symphonies Analytical Essays . Boston, 1888. [2] Bernstein discusses Beethoven’s 6th & 7th symphony, from Youtube.com [3] Lewis Lockwood: Beethoven’s symphonies: An artistic Vision . Norton, 2017.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Note: Post genuine comments on the topic only, spamming of ads or external links will be tracked and reported.

- Search for:

Recent Blogs

- Recording Survey: Bruckner’s Symphony No. 6 in A major

- Bruckner: Symphony No. 6 in A major

- Mahler: Symphony No. 2 in C minor “Resurrection” (3)

- Mahler: Symphony No. 2 in C minor “Resurrection” (2)

- Mahler: Symphony No. 2 in C minor “Resurrection” (1)

- Mahler: Symphony No. 1 in D major

- Beethoven: Symphony No. 9 “Choral”

- Beethoven: Symphony No. 8 in F Major, Op. 93

Genre & Types

- Excerpt (1)

- General (1)

- Orchestral (2)

- Piano Concerto (4)

- Piano Sonata (4)

- Symphony (19)

- Violin Concerto (2)

Of Beethoven�s �major� symphonies (that is, in the sense of innovation and prominence) the Seventh has aroused the widest spectrum of efforts to �interpret� its meaning. No such compulsion plagues the others � the �Choral� is guided by its text, the Fifth traces an emotional passage from grim determination to triumph, and Beethoven himself proclaimed his inspiration for the �Eroica� and labeled and described the movements of the �Pastoral.� But his Symphony # 7 in A major, Op. 92 is without such markers, and has drawn legions of commentators who felt compelled to explicate it. Arguably, that�s a sign of inspired subtlety � of the work, not the pundits � and a tribute to its remarkable ability to summon a broad spectrum of deeply personal and highly diverse response among listeners.

The sign of revolt is given; there is a rushing and running about of the multitude; an innocent man, or party, is surrounded, overpowered after a struggle and haled before a legal tribunal. Innocency weeps; the judge pronounces a harsh sentence; sympathetic voices mingle in laments and denunciations. � The magistrates are now scarcely able to quiet the wild tumult. The uprising is suppressed, but the people are not quieted; hope smiles cheeringly and suddenly the voice of the people pronounces the decision in harmonious agreement.

Alexander Wheeler Thayer asserted that �such balderdash disgusted and even enraged Beethoven� and that in 1819 �he dictated a letter � in which he protested energetically against such interpretations of his music.� Beethoven in 1814 by Louis-Rene Letronne The tide turned in due course. Writing in 1935, Donald Francis Tovey dismissed the �sad nonsense� of �a long time ago,� and proclaimed the Seventh �so overwhelmingly convincing and so obviously untranslatable that it has for many generations been treated quite reasonably as a piece of music, instead of an excuse for discussing the French Revolution.� Nowadays, most analysts seem content to follow Tovey�s approach. Thus Paul Affelder dismisses the irreconcilable range of all the past imagery as proof of its futility. William Mann agrees that the Seventh can only be viewed as abstract art, calling it �an argument in terms of music. � It is about melodic shapes, tunes and vestiges of tunes, about harmony and the effect that a new chord can make and build up, about keys and the effect one key can have on another, about the relationship of wind to string to brass instruments.� In that light, Richard Freed regards the Seventh as �a triumphant discourse by a man intoxicated with the spirit of creativity itself.� In a similar vein, although the Seventh has been choreographed, Charles O�Connell cautions that any association with the dance should not be literal, but rather in the sense of artistic spirituality � dancing with words and the pen rather than with feet.

Yet, while we may disparage the overblown literary efforts of past critics to attribute symbolic imagery to the Seventh , they provide a spur for fruitful thought. Thus, in retrospect, Maynard Solomon points to the common thread of a carnival or festival image as resonating our human desire for a temporary release from subjugation to the prevailing social order and a suspension of customary norms, a joyous lifting of restraints and an outpouring of mockery, all of which permeate the score. And Tim McDonald attributes the past tendency to the composer�s anti-social turbulent nature, which left the field wide open and, on a positive note, reflects the overriding sense of enthusiasm and excitement that the work generates.

Billed as a benefit for wounded Austrian and Bavarian soldiers and fueled in significant part by the celebratory mood now that Napoleon�s seemingly unstoppable conquest of Europe (and its threat of French hegemony) at last had run aground, the premiere was a gala affair, with many of Vienna�s celebrity musicians, including Hummel, Spohr, Salieri, Meyerbeer and Moscheles, recruited to play the percussion. Thayer, though, claimed that they viewed it as a gigantic professional frolic and a stupendous musical joke. Beethoven conducted but, according to Affelder, with difficulty as he could only hear the loudest passages; Spohr called his leadership �uncertain and often ridiculous.�

Modern disparagement aside, Wellington's Victory served a noble purpose � to provide the strongest launch of any major Beethoven work, even if only through association. Audiences at the time heard the Seventh Symphony's buoyant exuberance and irresistible rhythm as an ideal companion to the battle piece and embraced it as a deeply-felt patriotic gesture and a welcome manifestation of the jubilant public mood. Yet while Czerny echoed the popular assumption that it was inspired by the recent military victories, Schindler points out that it had been completed long before those events occurred. Reflecting modern scholarship, David Wyn Jones asserts that it had been written between the fall of 1811 and the summer of 1812. In any event, the Battle Symphony drew unprecedented attention to its more serious companion.

As a measure of the Seventh�s huge popularity, by early 1816 its publisher had issued not only the full score and orchestral parts but arrangements for wind band, quartet, trio, piano duet and piano solo. Early critics, though, were less enamored. Aside from some nonsensical, hyperbolic slurs (Carl Maria von Weber said that Beethoven was ripe for the madhouse and Friedrich Weick called it the work of a drunkard), several critics claimed to find it disorganized and repetitious. Thus, one called it �a true mixture of tragic, comic, serious and trivial ideals which spring from one level to another without any connection [and] repeat themselves to excess.� Over a decade later, the London Harmonicum echoed: �Often as we have heard it performed, we cannot yet discover any design in it, neither can we trace any connection in its parts.�

Beyond its extraordinary sense of rhythm, other commentators credit the Seventh as romantic, in the sense of �swift and unexpected changes and contrasts, exciting the imagination to the highest degree and whirling it into new and strange regions� (Grove). Tovey expands on this notion of "exciting the imagination," while rationalizing the compulsion to �interpret� it in diverse ways, �insofar as romance is a term which, like humor, every self-respecting person claims to understand, while no two people understand it in quite the same way.� Others laud its innovative orchestration. Basil Lam calls the scoring �wonderful beyond explanation, unsurpassed anywhere for grandeur of sound,� even though this is achieved with the same modest orchestra familiar to Haydn and Mozart. Irving Kolodin cites in particular the finale as the first real orchestral piece ever written, in that instruments are not used for mere color but in keeping with the potential sonority of their inherent character. Features cited by Barry Cooper include the use of horns crooked in A, giving them an unusually high register, and drone basses, an offshoot of the Irish songs Beethoven had been commissioned to arrange at the time, in which such sustained harmony was common. William Drabkin cites the use of winds as a self-contained group rather than as an amplifier of string-dominated textures. Also remarkable, especially in the finale, is the way that Beethoven creates a heightened sense of activity within the continuity of a musical line by quickly and fluently passing phrases back and forth among instruments. The net result of all this, according to Drabkin, is that its originality lies not in the materials or proportions, which he finds quite conventional, but rather in the way Beethoven is able to control our perception of musical time. And this is achieved without any sense of respite from the constant energy and momentum � as many commentators have pointed out, similar to his shorter and simpler companion Symphony # 8 in F, Op. 93 , there really is no slow portion at all, as the second movement specifies � allegretto � and even the trio is merely marked � assai meno presto � (much less quickly).

The acute sense of expectation fittingly peaks with a disarmingly simple but hugely effective transition to the ensuing vivace � it consists of nothing but 55 repeated E�s that at first tease and then coalesce into the modest but alluring three-note pattern in triplet time (a dotted eighth note, a sixteenth note and an eighth note) that will carry through to the end of the movement. (Noting that the repeated note is the top open violin string, Sigmund Spaeth intriguingly calls this �a suggestion of tuning fiddles,� as if to stress preparation for all that lies ahead.) Yet after four suspenseful minutes devoted to the introduction, rather than relieve the tension by having the vivace erupt dramatically, instead it emerges gently and playfully in the soft winds and only after a series of sforzando urgings do the strings at last proudly proclaim it fortissimo . The rest of the movement is in sonata form, but for Grove provides a prime example of Beethoven�s inventive genius � although the recapitulation presents the same materials as the exposition, it does so with �treatment, instrumentation and feeling all absolutely different.�

Unlike a standard symphonic scherzo movement, comprising a scherzo , a trio and an abbreviated repeat of the scherzo (A-B-A), here both sections are repeated (A-B-A-B-A). McDonald suggests that this was to give the movement a dimension commensurate with the overall scale of the work. Yet, the first repetition of the scherzo presents a huge surprise, suppressing the ff stings of the initial appearance to the same pp whisper as the rest to lend it an entirely new and unsuspected sustained delicacy. In keeping with the nature of a scherzo (literally, a �joke�), Beethoven adds humorous touches, throwing off the regular musical periods with two-bar insertions, flavoring the trio with horn �burps� (Schumann�s term) and, above all, crafting an inspired ending, in which the music subsides to begin what promises to launch yet a third trio only to sour and then after a mere four bars plunge into a rapid five-note cadence.

A second issue is the size of the ensemble that best conveys a score that is full of power yet demands fleet precision. The historically-informed approach generally is to assume an orchestra of modest dimensions, presumably typical of Beethoven�s day. Yet Drabkin notes that for a February 14, 1814 performance of the Seventh the composer left a memorandum specifying 18 first violins, 18 seconds, 14 violas, 12 celli, 7 basses and 2 contrabassoons (thus suggesting that all winds were to be doubled) � the approximate complement of a full modern symphonic orchestra (which would have to reinforce brass and winds yet further to match our louder strings). A related question is whether Beethoven, by now profoundly deaf, wrote within the practical limits of his time or on a more abstract, idealized level that transcends the resources he had at his disposal.

Robert Philips raises a third challenge by stressing the often overlooked point that early 20th century practice, as preserved in early recordings, is often wrongly dismissed as bloated and indulgent, yet was closer in time to Beethoven than to our own era and thus should not be disdained as an aberration requiring correction but rather as a manifestation of a venerable performance tradition. In particular, Philips catalogs more flexible tempos, greater acceleration, clearly defined tempo changes, more flexible and casual treatment of rhythmic detail, more restrained vibrato, more rubato (dislocating melody from accompanying rhythm) more portamento (sliding between notes) to clarify contrapuntal textures, and the use of individual string fingering in lieu of modern uniformity. He concludes that expressive irregularities and personal touches that strike us as decadent perhaps are far more authentic than the neat, clean simplicity that we tend to mistake as genuine. That, in turn, relegates any attempt to denounce the value of any particular interpretive approach to little more than a mere personal preference.

- Coates, London Symphony Orchestra (HMV 78s, Pristine CD or download, 1921; 23' [abridged])

Coates�s Seventh remains remarkable for preserving interpretive traditions inherited from the 19th century. Relatively free of the improvisatory feeling of much of his superb discography, Coates�s tempos remain generally steady throughout each section, even though he does accelerate the allegretto at the first shift to A-major (bar 102). Otherwise, he feels free to ignore Beethoven�s tempo indications, although hardly in the sense that most attach to them as being too fast. Thus, while his trio is taken at a leisurely 64 bars to the minute compared to Beethoven�s specification of 84, his opening poco sostenuto is a startling 90 beats to the minute versus Beethoven�s 69, and his finale is a frantic 92 bars v. 72, gaining extraordinary visceral excitement despite some lapses in articulation at the breakneck speed. It would be tempting to discount the extreme rapidity in order to fit the work onto six 78 rpm sides were it not for the similarly wild pacing of isolated movements of Coates�s Eroica and Jupiter recordings. Yet there were practical compromises, as all movements but the allegretto are cruelly cut � while the poco sustenuto introduction is intact, 95 bars are bypassed in the first-movement vivace , both the second scherzo and trio are omitted, and the entire recapitulation (bars 254-428) is excised from the finale. (The first of these cuts, coming at the mid-point of the vivace , is far more noticeable now than at the time, as it occurred between side changes, when continuity would have lapsed anyway.) Despite the severe restrictions of the acoustic recording process, the pickup is remarkably detailed, with inner voices clearly audible, the ensemble well-balanced and accents closely observed, although the dynamics are heavily compressed and the texture is distorted by the attenuation of overtones (making the flutes sound like slide-whistles) and the substitution of tubas for basses (with a more rasping, flatulent sonority � a routine studio practice of the time). Cuts and compromised fidelity aside, this remains a compelling, vivid account, as enjoyable today as when it first astounded listeners.

- Weingartner, London Symphony Orchestra (Columbia 78s, 1923-4; 32')

Although remembered nowadays for launching, even ahead of Toscanini, the modern �objective� style that typified (or, depending on your taste, ruined) 20th century interpretation (or lack thereof), Weingartner�s roots extended a generation deeper into the 19th century than Coates�s. Here, already 60 years old, he reaches back to his artistic origins to present a deeply romanticized, heavily inflected vision. Like Coates, he takes the opening faster, and the scherzo slower, than the score�s specifications (although his finale nearly matches Beethoven�s tempo). The most radical feature, which literally sets the pace for the vast majority of recordings that would follow, comes with the trio, which he paces at a mere 48 bars to the minute v. Beethoven�s 84 (and Coates�s 64). The result is a feeling not only of considerable repose but of comfort, perhaps in part because we have grown accustomed to hearing it that way. Weingartner may have been only the second conductor to record the Seventh , or the first to record it complete if we discount Coates�s condensation, but he also was the first to re-record it, in 1927 with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra as part of a complete set to commemorate the centennial of Beethoven�s death (and he would wax it yet a third time in 1936 with the Vienna Philharmonic in a less distinctive rendition). The 1927 remake is fascinating in comparison to the acoustic venture, as the scherzo is considerably faster (140 bars to the minute v. 116), thus providing a further reminder of the tradition of individual interpretation that could vary drastically from one performance to another (here bridged by a mere few years).

- Wohllebe, Berlin State Opera Orchestra (Grammophon 78s, 1924; 32:40)

Very little seems to have been written about Walter Wohllebe, other than that he was a choral director who assisted Erich Kleiber at the Berlin State Opera in 1923. Yet he must have been held in sufficient esteem to have been chosen to lead the Seventh in the first integral set of Beethoven symphonies, alongside such luminaries as Klemperer, Fried, Pfitzner and Seidler-Winkler. As might be expected of a relatively unknown conductor (he may have led only one other recording, of the Wagner Tannhauser Overture ) he adheres rather closely to the prescribed tempos but with two hugely notable exceptions: he begins the allegretto at a snail�s pace of only 50 beats per minute (v. Beethoven�s 76), but then (like Coates) jumps to 69 at the first A-major section, which he maintains throughout the rest, and (like Weingartner) takes the entire trio at a lugubrious 45 bars per minute, barely half of the prescribed 84. As a further individualistic touch, he adds a melodramatic flourish to the finale by prolonging the held notes and thus disrupting the insistent rhythm. Possibly in an effort to avoid sinking below the inherent noise floor of acoustic recordings, dynamics are nearly uniformly loud throughout, thus denying us the exhilarating surges and sforzando impacts of the score. The finale fits on a single side thanks to the same cut as Coates. The fidelity is indistinct and blurry, ironically due in part to the apparent use of real basses (and their unfortunate mid-range harmonic resonance) rather than the crisper tubas that most acoustic recordings substituted. Overall, the execution is rather indifferent and slipshod, but even that may preserve a valuable tradition of sorts � by draining much of the spirit and invoking the impression of an under-rehearsed pick-up band, we can empathize with early critics who found the work long and tedious, and to marvel with appreciation at Beethoven�s care in arranging its orchestration, textures and dynamics well beyond any reasonable expectations of the concert conditions of his time.

- Strauss, Berlin State Opera Orchestra (Grammophon 78s, Koch CD, 1926; 32:15)

This first electrical recording of the Symphony # 7 serves to disprove a stereotype. Perhaps due to his economical gestures, rapid tempos, obsession with fees and facetious pronouncements (conductors should never perspire; woodwinds should never be heard; the proper place for a conductor�s left [expressive] hand is in his waist-coat pocket), Richard Strauss tends to be remembered as a lazy and indifferent conductor. The generally reliable Harold Schonberg calls his records �disgraceful. � He rushes through the music with no force, no charm, no inflection and with a metronomic rigidity.� Yet nearly all Strauss�s recordings belie this damning portrayal. While most were of his own work, even his earliest (1917 acoustics of Till Eulenspiegel and Don Juan ) crackle with excitement yet have plenty of repose in their central lyrical sections. (Peter Morse asserts that Strauss was late to the session and the first two sides of Don Juan in fact had been led by George Szell.) His 1926 Beethoven Seventh is generally calm but never bland, and has plenty of drama, from powerfully emphatic opening chords to setting up blazing endings of all but the allegretto , slowing in order to accentuate a final acceleration. If there is any �laziness� to Strauss�s conception, it lies in his rather formulaic tendency to link tempo and dynamics, so as to speed up for loud portions and slow down for softer ones. He even enlivens the normally steadfast finale with constant acceleration and deceleration. Strauss takes full advantage of the wider dynamic range of the then-new electrical recording process, although at the cost of some harsh sound, distortion and noise, inherent flaws of the Brunswick system which bypassed microphones for a more complex technology in which vibrations caused a mirror attached to a diaphragm to deflect a light ray onto a photocell. Unfortunately, while the rest of the symphony is presented complete, Strauss cuts the finale to fit on a single 78 rpm side and heightens the excitement by culminating in a wildly fast ending. (While the scherzo would seem the logical candidate for any necessary condensation, Strauss, despite his reputation as a speed demon, takes it at an abnormally slow pace, and his trio is barely half Beethoven�s specified tempo, so that the movement consumes a full two sides.) Any residual impression of Strauss as an uninspired conductor perhaps stems from the deep respect of one great composer for another.

- Stokowski, Philadelphia Orchestra (Victor 78s, Biddulph CD, 1927; 36')

Here we arrive at the first recording of the Seventh that requires few apologies or mental adjustment for its sheer sound. Richly recorded only two years after introduction of the new electrical system, it�s beautifully played with confidence and a sheen that makes Strauss sound tentative and scrappy (and perhaps emphasizes the difference between an esteemed guest conductor and a permanent music director). Stokowski�s approach is unabashedly romantic, constantly adjusting the tempos to craft an organic voyage of vibrant, shifting feeling. The allegretto , in particular, emerges as a deeply emotional journey that takes its time (10:30 v. 7:05 for Weingartner, 7:20 for Coates, 8:20 for Wohlebbe and 9:25 for Strauss) to plumb depths impossible at any tempo near Beethoven�s and slows yet further for a heart-rending conclusion. The trio, too, overflows with profound feeling. Even in the faster sections, Stokowski constantly shapes phrases and leans into climaxes, taking full advantage of the extended dynamic range to create impassioned surges in the vivace and snarling and swirling his strings in the finale (and extending held notes to break the tempo for melodramatic effect).

Ever the populist educator, Stokowski also recorded a companion �Outline of Themes� side in which he marvels at Beethoven�s creation of such a joyous work during a period of personal melancholy, repeats the clich� about the Seventh being a dance symphony and then announces and plinks out the major themes on a piano. While Stokowski�s lecture nowadays may strike us as shallow and condescending, Edward Johnson reminds us in his notes to the Biddulph CD reissue that this was the first American recording of the work, that radio and recordings were in their infancy and that many record-buyers would be hearing this symphony � and perhaps hearing of this symphony � for the very first time. That sobering thought prompts reflection on how much recordings have changed our culture from one in which the opportunity to hear a given work required the rare and taxing effort to attend a concert to one in which we have the luxury of summoning great performances at the push of a few buttons, although much may have been lost in the transition from an atmosphere demanding rapt attention to one that relegates music to superficial background.

Stokowski would record the Seventh again in 1958 with the Symphony of the Air (United Artists LP) and once more in 1973, his 91st year, near the very end of his extraordinarily prolific recording career, with the New Philharmonia Orchestra for Decca/London Phase Four. Exquisitely burnished, considerably slower and in superlative fidelity, it breathes with an autumnal perspective that lovingly transmutes impulsive energy into a smooth flow of tender affection. It also bears the dubious distinction of one of the very few stereo recordings of the Seventh to be truncated. According to the LP liner notes, �Maestro Stokowski has formed the opinion that the conventional Scherzo-Trio-Scherzo format is perfectly adequate and has subsequently omitted the second runthrough.� Even so, to all of us used to the five-part structure the abridgement comes as a surprise and is capped by an immediate leap into the finale � one more highly effective trick up the sleeve of an old master to compel us to focus our attention for a fresh experience.

- Toscanini, New York Philharmonic (Victor 78s, BMG CD, 1936; 34')

The ecstatic praise heaped on this 1936 recording is truly astounding: �The Beethoven Seventh� (Kolodin); �The most perfect recording of any Beethoven symphony ever put on disc� (Records and Recordings, 1969); �Justifiably considered one of the greatest symphonic recordings ever made� (Harvey Sachs); �The standard against which all subsequent ones have been judged (and found wanting). � It remains as close to a perfect recording as one is likely to encounter this side of Elysium� (Mark Obert-Thorn). While I would hardly dare to pit my humble amateur taste against the weight of such expert authority, I just don�t hear it. Indeed, I wonder if their encomia were in part a function of the modern trend of distancing ourselves from the 19th century cult of personality in favor of a more �neutral� approach to the classics. In any event, Toscanini�s achievement here was to document a near-literal translation into sound of a score that perhaps demands (or tolerates) less �interpretation� than any of Beethoven�s other major works. His only significant departures from the score are an extremely somber poco sustenuto of 50 beats per minute v. Beethoven�s specification of 69 and an allegretto of 60 v. Beethoven�s 76; all other pacing is closely aligned with the composer�s. The method yields a striking result, enabling Toscanini to mold tempos, dynamics, textures and phrasing with a degree of subtlety that only a highly objective approach permits. Obert-Thorn reports that Toscanini had become annoyed by the start-and-stop mechanics of recording 78 rpm sides and had refused to approve efforts to record his concerts continuously on sound film, but here, at the end of his seven-year tenure with the New York Philharmonic, he agreed to momentary stops between sides, only long enough to switch the line inputs between turntables, and the result is a fine forward sweep of continuity.

To my ears, the Philharmonic set sounds bland when compared to Toscanini�s concert recordings of the era. Thus, while the timings are nearly identical, a 1935 BBC Symphony Orchestra concert (BBC Music CD) is marginally more dramatic, with more urgent articulation and inflection and a somewhat quicker allegretto . As Sachs points out, the excellence and synchronization of conductor and orchestra are remarkable, as they had only worked together for two weeks at that point. Even more intense is a 1939 concert with the NBC Symphony Orchestra (Music and Arts CD), which substitutes precision for atmosphere, abetted by a sharply detailed recording with crisp timpani, winds and brass in lieu of the smoother blend and dull thuds of the Philharmonic studio recording. And tantalizing fragments from an April 1933 Philharmonic concert, despite miserable sound, evidence a tightly focussed yet pliant approach. In comparison, Toscanini�s highly-regarded NBC 1951 studio remake (RCA LP, BMG CD) sounds rather tired, with some �lazy� trumpet figures falling behind the beat, although it is partly redeemed by even stronger timpani-fueled climaxes. Any of the Toscanini outings exemplify a dedication to presenting the score with only minimal injection of the performer�s personality. Whether that is the epitome of integrity or a lack of imagination is, for me at least, an open question. In any event, what was once a daring pioneering approach has since become the norm and deserves to be remembered on that basis, even if its sense of boldness has long since dissipated.

- Furtwangler, Berlin Philharmonic (DG or Music and Arts CD, November 3, 1943 concert; 37�')

A simplistic myth contrasts Toscanini and Furtwangler as inhabiting the extreme opposite poles of music interpretation. Yet in Beethoven, and especially here, it seems warranted. While Toscanini presents the Symphony # 7 as pure music, Furtwangler delves deep beneath the surface to craft a radical and profoundly personal rethinking that seeks eternal truth where others are content with lyrical grace and invocations of the dance. As with so many of his interpretations, his most intense reading is preserved in a Berlin Philharmonic concert during World War II. Consider the opening � each of the tutti chords is marked staccato , indicating a sharp attack, but under Furtwangler they emerge rough and blurred, struggling to overcome the stifling silence and heralding his vision of the entire work as an elemental metaphysical struggle between energy and fatigue, light and dark, motion and stasis � a heavy, dark and brooding universe far removed from any notion of classical balance or delight, much less �the dance.� Indeed, the ensuing vivace , while taken on average at the specified pace, assumes a wholly different character as the basses growl with menace, the tympani thunder with power, the horns bray in dire warning and the whole ensemble surges ahead and then grinds to a halt on a precipice of the unknown before resuming more as a tentative searching question than an affirmative resolute conviction, pulled back to earth before it can truly soar. The opening chord of the allegretto is held for eight seconds � over twice its notated length � and also heralds the ensuing movement that is dominated by a mournful yet unstable undercurrent, smoothly gliding between 27 and 36 beats per minute (v. Beethoven�s 76). The scherzo is suitably fast but thick, underlining the difference between tempo and texture. The feeling of insecurity returns in the finale, also taken at the prescribed pace, but with huge timpani rolls, abrasive trumpet accents and insistent outbursts, sounding far more desperate than joyous. He ends with an enormous acceleration that seems more a cathartic emergence from tragedy than a triumphant outcome. Indeed, his entire interpretation invests this ostensibly festive work with a pervasive sadness that adds a fascinating level of meaning to challenge our expectations. (Furtwangler�s other extant recordings of the Seventh � a 1948 Stockkholm Philharmonic concert, a 1950 Vienna Philharmonic EMI studio recording, a 1953 Berlin Philharmonic concert and a 1954 Vienna Philharmonic concert � all follow the same general scheme, but without the intense focus of this wartime concert.)

- Mengelberg, Concertgebouw Orchestra of Amsterdam (Music and Arts CD, Pristine download, 1940 concert; 39�')

It would be tempting to say that Mengelberg followed firmly in Furtwangler�s footsteps, had his career not begun 15 years earlier. Chronology aside, though, their approaches to the Symphony # 7 are strikingly similar, full of rolled opening chords, constantly variable tempos and thick tympani-fueled climaxes. They finally part company in the trio, which Mengelberg takes at an astoundingly protracted 40 beats per minute. But even that is a mere average, as the tempo constantly shifts and at times grinds to a near-halt, after which the scherzo snaps in with startling impact. Indeed, the effect of both the pacing and the instability is to deny any feeling for a downbeat, which dissolves into a state of suspended time that is as far from the rudiments of the dance, with its reliably consistent tempo, as can be. From that point forward, any possibility of restoring elation through the finale is irreparably lost. Indeed, Mengelberg�s finale is even darker than Furtwangler�s, owing in substantial part to the recording that emphasizes the bass-heavy sonic anchor to keep the entire work not only earth-bound but incapable of even the momentary flights of escape that his surges of onrushing power might otherwise allow. Rather, the impression is one of hesitation and uncertainty. Like Furtwangler, Mengelberg transforms the symphony into something wholly distinctive.