Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, should college athletes be paid an expert debate analysis.

Extracurriculars

The argumentative essay is one of the most frequently assigned types of essays in both high school and college writing-based courses. Instructors often ask students to write argumentative essays over topics that have “real-world relevance.” The question, “Should college athletes be paid?” is one of these real-world relevant topics that can make a great essay subject!

In this article, we’ll give you all the tools you need to write a solid essay arguing why college athletes should be paid and why college athletes should not be paid. We'll provide:

- An explanation of the NCAA and what role it plays in the lives of student athletes

- A summary of the pro side of the argument that's in favor of college athletes being paid

- A summary of the con side of the argument that believes college athletes shouldn't be paid

- Five tips that will help you write an argumentative essay that answers the question "Should college athletes be paid?"

The NCAA is the organization that oversees and regulates collegiate athletics.

What Is the NCAA?

In order to understand the context surrounding the question, “Should student athletes be paid?”, you have to understand what the NCAA is and how it relates to student-athletes.

NCAA stands for the National Collegiate Athletic Association (but people usually just call it the “N-C-double-A”). The NCAA is a nonprofit organization that serves as the national governing body for collegiate athletics.

The NCAA specifically regulates collegiate student athletes at the organization’s 1,098 “member schools.” Student-athletes at these member schools are required to follow the rules set by the NCAA for their academic performance and progress while in college and playing sports. Additionally, the NCAA sets the rules for each of their recognized sports to ensure everyone is playing by the same rules. ( They also change these rules occasionally, which can be pretty controversial! )

The NCAA website states that the organization is “dedicated to the well-being and lifelong success of college athletes” and prioritizes their well-being in academics, on the field, and in life beyond college sports. That means the NCAA sets some pretty strict guidelines about what their athletes can and can't do. And of course, right now, college athletes can't be paid for playing their sport.

As it stands, NCAA athletes are allowed to receive scholarships that cover their college tuition and related school expenses. But historically, they haven't been allowed to receive additional compensation. That meant athletes couldn't receive direct payment for their participation in sports in any form, including endorsement deals, product sponsorships, or gifts.

Athletes who violated the NCAA’s rules about compensation could be suspended from participating in college sports or kicked out of their athletic program altogether.

The Problem: Should College Athletes Be Paid?

You know now that one of the most well-known functions of the NCAA is regulating and limiting the compensation that student-athletes are able to receive. While many people might not question this policy, the question of why college athletes should be paid or shouldn't be paid has actually been a hot-button topic for several years.

The fact that people keep asking the question, “Should student athletes be paid?” indicates that there’s some heat out there surrounding this topic. The issue is frequently debated on sports talk shows , in the news media , and on social media . Most recently, the topic re-emerged in public discourse in the U.S. because of legislation that was passed by the state of California in 2019.

In September 2019, California governor Gavin Newsom signed a law that allowed college athletes in California to strike endorsement deals. An endorsement deal allows athletes to be paid for endorsing a product, like wearing a specific brand of shoes or appearing in an advertisement for a product.

In other words, endorsement deals allow athletes to receive compensation from companies and organizations because of their athletic talent. That means Governor Newsom’s bill explicitly contradicts the NCAA’s rules and regulations for financial compensation for student-athletes at member schools.

But why would Governor Newsom go against the NCAA? Here’s why: the California governor believes that it's unethical for the NCAA to make money based on the unpaid labor of its athletes . And the NCAA definitely makes money: each year, the NCAA upwards of a billion dollars in revenue as a result of its student-athlete talent, but the organization bans those same athletes from earning any money for their talent themselves. With the new California law, athletes would be able to book sponsorships and use agents to earn money, if they choose to do so.

The NCAA’s initial response to California’s new law was to push back hard. But after more states introduced similar legislation , the NCAA changed its tune. In October 2019, the NCAA pledged to pass new regulations when the board voted unanimously to allow student athletes to receive compensation for use of their name, image, and likeness.

Simply put: student athletes can now get paid through endorsement deals.

In the midst of new state legislation and the NCAA’s response, the ongoing debate about paying college athletes has returned to the spotlight. Everyone from politicians, to sports analysts, to college students are arguing about it. There are strong opinions on both sides of the issue, so we’ll look at how some of those opinions can serve as key points in an argumentative essay.

Let's take a look at the arguments in favor of paying student athletes!

The Pros: Why College Athletes Should B e Paid

Since the argument about whether college athletes should be paid has gotten a lot of public attention, there are some lines of reasoning that are frequently called upon to support the claim that college athletes should be paid.

In this section, we'll look at the three biggest arguments in favor of why college athletes should be paid. We'll also give you some ideas on how you can support these arguments in an argumentative essay.

Argument 1: The Talent Should Receive Some of the Profits

This argument on why college athletes should be paid is probably the one people cite the most. It’s also the easiest one to support with facts and evidence.

Essentially, this argument states that the NCAA makes millions of dollars because people pay to watch college athletes compete, and it isn’t fair that the athletes don't get a share of the profits

Without the student athletes, the NCAA wouldn’t earn over a billion dollars in annual revenue , and college and university athletic programs wouldn’t receive hundreds of thousands of dollars from the NCAA each year. In fact, without student athletes, the NCAA wouldn’t exist at all.

Because student athletes are the ones who generate all this revenue, people in favor of paying college athletes argue they deserve to receive some of it back. Otherwise, t he NCAA and other organizations (like media companies, colleges, and universities) are exploiting a bunch of talented young people for their own financial gain.

To support this argument in favor of paying college athletes, you should include specific data and revenue numbers that show how much money the NCAA makes (and what portion of that actually goes to student athletes). For example, they might point out the fact that the schools that make the most money in college sports only spend around 10% of their tens of millions in athletics revenue on scholarships for student-athletes. Analyzing the spending practices of the NCAA and its member institutions could serve as strong evidence to support this argument in a “why college athletes should be paid” essay.

I've you've ever been a college athlete, then you know how hard you have to train in order to compete. It can feel like a part-time job...which is why some people believe athletes should be paid for their work!

Argument 2: College Athletes Don’t Have Time to Work Other Jobs

People sometimes casually refer to being a student-athlete as a “full-time job.” For many student athletes, this is literally true. The demands on a student-athlete’s time are intense. Their days are often scheduled down to the minute, from early in the morning until late at night.

One thing there typically isn’t time for in a student-athlete’s schedule? Working an actual job.

Sports programs can imply that student-athletes should treat their sport like a full-time job as well. This can be problematic for many student-athletes, who may not have any financial resources to cover their education. (Not all NCAA athletes receive full, or even partial, scholarships!) While it may not be expressly forbidden for student-athletes to get a part-time job, the pressure to go all-in for your team while still maintaining your eligibility can be tremendous.

In addition to being a financial burden, the inability to work a real job as a student-athlete can have consequences for their professional future. Other college students get internships or other career-specific experience during college—opportunities that student-athletes rarely have time for. When they graduate, proponents of this stance argue, student-athletes are under-experienced and may face challenges with starting a career outside of the sports world.

Because of these factors, some argue that if people are going to refer to being a student-athlete as a “full-time job,” then student-athletes should be paid for doing that job.

To support an argument of this nature, you can offer real-life examples of a student-athlete’s daily or weekly schedule to show that student-athletes have to treat their sport as a full-time job. For instance, this Twitter thread includes a range of responses from real student-athletes to an NCAA video portraying a rose-colored interpretation of a day in the life of a student-athlete.

Presenting the Twitter thread as one form of evidence in an essay would provide effective support for the claim that college athletes should be paid as if their sport is a “full-time job.” You might also take this stance in order to claim that if student-athletes aren’t getting paid, we must adjust our demands on their time and behavior.

Argument 3: Only Some Student Athletes Should Be Paid

This take on the question, “Should student athletes be paid?” sits in the middle ground between the more extreme stances on the issue. There are those who argue that only the student athletes who are big money-makers for their university and the NCAA should be paid.

The reasoning behind this argument? That’s just how capitalism works. There are always going to be student-athletes who are more talented and who have more media-magnetizing personalities. They’re the ones who are going to be the face of athletic programs, who lead their teams to playoffs and conference victories, and who are approached for endorsement opportunities.

Additionally, some sports don't make money for their schools. Many of these sports fall under Title IX, which states that no one can be excluded from participation in a federally-funded program (including sports) because of their gender or sex. Unfortunately, many of these programs aren't popular with the public , which means they don't make the same revenue as high-dollar sports like football or basketball .

In this line of thinking, since there isn’t realistically enough revenue to pay every single college athlete in every single sport, the ones who generate the most revenue are the only ones who should get a piece of the pie.

To prove this point, you can look at revenue numbers as well. For instance, the womens' basketball team at the University of Louisville lost $3.8 million dollars in revenue during the 2017-2018 season. In fact, the team generated less money than they pay for their coaching staff. In instances like these, you might argue that it makes less sense to pay athletes than it might in other situations (like for University of Alabama football, which rakes in over $110 million dollars a year .)

There are many people who think it's a bad idea to pay college athletes, too. Let's take a look at the opposing arguments.

The Cons: Why College Athletes Shouldn't Be Paid

People also have some pretty strong opinions about why college athletes shouldn't be paid. These arguments can make for a pretty compelling essay, too!

In this section, we'll look at the three biggest arguments against paying college athletes. We'll also talk about how you can support each of these claims in an essay.

Argument 1: College Athletes Already Get Paid

On this side of the fence, the most common reason given for why college athletes should not be paid is that they already get paid: they receive free tuition and, in some cases, additional funding to cover their room, board, and miscellaneous educational expenses.

Proponents of this argument state that free tuition and covered educational expenses is compensation enough for student-athletes. While this money may not go straight into a college athlete's pocket, it's still a valuable resource . Considering most students graduate with nearly $30,000 in student loan debt , an athletic scholarship can have a huge impact when it comes to making college affordable .

Evidence for this argument might look at the financial support that student-athletes receive for their education, and compare those numbers to the financial support that non-athlete students receive for their schooling. You can also cite data that shows the real value of a college tuition at certain schools. For example, student athletes on scholarship at Duke may be "earning" over $200,000 over the course of their collegiate careers.

This argument works to highlight the ways in which student-athletes are compensated in financial and in non-financial ways during college , essentially arguing that the special treatment they often receive during college combined with their tuition-free ride is all the compensation they have earned.

Some people who are against paying athletes believe that compensating athletes will lead to amateur athletes being treated like professionals. Many believe this is unfair and will lead to more exploitation, not less.

Argument 2: Paying College Athletes Would Side-Step the Real Problem

Another argument against paying student athletes is that college sports are not professional sports , and treating student athletes like professionals exploits them and takes away the spirit of amateurism from college sports .

This stance may sound idealistic, but those who take this line of reasoning typically do so with the goal of protecting both student-athletes and the tradition of “amateurism” in college sports. This argument is built on the idea that the current system of college sports is problematic and needs to change, but that paying student-athletes is not the right solution.

Instead, this argument would claim that there is an even better way to fix the corrupt system of NCAA sports than just giving student-athletes a paycheck. To support such an argument, you might turn to the same evidence that’s cited in this NPR interview : the European model of supporting a true minor league system for most sports is effective, so the U.S. should implement a similar model.

In short: creating a minor league can ensure athletes who want a career in their sport get paid, while not putting the burden of paying all collegiate athletes on a university.

Creating and supporting a true professional minor league would allow the students who want to make money playing sports to do so. Universities could then confidently put earned revenue from sports back into the university, and student-athletes wouldn’t view their college sports as the best and only path to a career as a professional athlete. Those interested in playing professionally would be able to pursue this dream through the minor leagues instead, and student athletes could just be student athletes.

The goal of this argument is to sort of achieve a “best of both worlds” solution: with the development and support of a true minor league system, student-athletes would be able to focus on the foremost goal of getting an education, and those who want to get paid for their sport can do so through the minor league. Through this model, student-athletes’ pursuit of their education is protected, and college sports aren’t bogged down in ethical issues and logistical hang-ups.

Argument 3: It Would Be a Logistical Nightmare

This argument against paying student athletes takes a stance on the basis of logistics. Essentially, this argument states that while the current system is flawed, paying student athletes is just going to make the system worse. So until someone can prove that paying collegiate athletes will fix the system, it's better to maintain the status quo.

Formulating an argument around this perspective basically involves presenting the different proposals for how to go about paying college athletes, then poking holes in each proposed approach. Such an argument would probably culminate in stating that the challenges to implementing pay for college athletes are reason enough to abandon the idea altogether.

Here's what we mean. One popular proposed approach to paying college athletes is the notion of “pay-for-play.” In this scenario, all college athletes would receive the same weekly stipend to play their sport .

In this type of argument, you might explain the pay-for-play solution, then pose some questions toward the approach that expose its weaknesses, such as: Where would the money to pay athletes come from? How could you pay athletes who play certain sports, but not others? How would you avoid Title IX violations? Because there are no easy answers to these questions, you could argue that paying college athletes would just create more problems for the world of college sports to deal with.

Posing these difficult questions may persuade a reader that attempting to pay college athletes would cause too many issues and lead them to agree with the stance that college athletes should not be paid.

5 Tips for Writing About Paying College Athletes

If you’re assigned the prompt “Should college athletes be paid," don't panic. There are several steps you can take to write an amazing argumentative essay about the topic! We've broken our advice into five helpful tips that you can use to persuade your readers (and ace your assignment).

Tip 1: Plan Out a Logical Structure for Your Essay

In order to write a logical, well-organized argumentative essay, one of the first things you need to do is plan out a structure for your argument. Using a bare-bones argumentative outline for a “why college athletes should be paid” essay is a good place to start.

Check out our example of an argumentative essay outline for this topic below:

- The thesis statement must communicate the topic of the essay: Whether college athletes should be paid, and

- Convey a position on that topic: That college athletes should/ should not be paid, and

- State a couple of defendable, supportable reasons why college athletes should be paid (or vice versa).

- Support Point #1 with evidence

- Explain/interpret the evidence with your own, original commentary

- Support Point #2 with evidence

- Explain/interpret the evidence with your own, original commentary

- Support Point #3 with evidence

- New body paragraph addressing opposing viewpoints

- Concluding paragraph

This outline does a few things right. First, it makes sure you have a strong thesis statement. Second, it helps you break your argument down into main points (that support your thesis, of course). Lastly, it reminds you that you need to both include evidence and explain your evidence for each of your argumentative points.

While you can go off-book once you start drafting if you feel like you need to, having an outline to start with can help you visualize how many argumentative points you have, how much evidence you need, and where you should insert your own commentary throughout your essay.

Remember: the best argumentative essays are organized ones!

Tip 2: Create a Strong Thesis

T he most important part of the introduction to an argumentative essay claiming that college athletes should/should not be paid is the thesis statement. You can think of a thesis like a backbone: your thesis ties all of your essay parts together so your paper can stand on its own two feet!

So what does a good thesis look like? A solid thesis statement in this type of argumentative essay will convey your stance on the topic (“Should college athletes be paid?”) and present one or more supportable reasons why you’re making this argument.

With these goals in mind, here’s an example of a thesis statement that includes clear reasons that support the stance that college athletes should be paid:

Because the names, image, and talents of college athletes are used for massive financial gain, college athletes should be able to benefit from their athletic career in the same way that their universities do by getting endorsements.

Here's a thesis statement that takes the opposite stance--that college athletes shouldn’t be paid --and includes a reason supporting that stance:

In order to keep college athletics from becoming over-professionalized, compensation for college athletes should be restricted to covering college tuition and related educational expenses.

Both of these sample thesis statements make it clear that your essay is going to be dedicated to making an argument: either that college athletes should be paid, or that college athletes shouldn’t be paid. They both convey some reasons why you’re making this argument that can also be supported with evidence.

Your thesis statement gives your argumentative essay direction . Instead of ranting about why college athletes should/shouldn’t be paid in the remainder of your essay, you’ll find sources that help you explain the specific claim you made in your thesis statement. And a well-organized, adequately supported argument is the kind that readers will find persuasive!

Tip 3: Find Credible Sources That Support Your Thesis

In an argumentative essay, your commentary on the issue you’re arguing about is obviously going to be the most fun part to write. But great essays will cite outside sources and other facts to help substantiate their argumentative points. That's going to involve—you guessed it!—research.

For this particular topic, the issue of whether student athletes should be paid has been widely discussed in the news media (think The New York Times , NPR , or ESPN ).

For example, this data reported by the NCAA shows a breakdown of the gender and racial demographics of member-school administration, coaching staff, and student athletes. These are hard numbers that you could interpret and pair with the well-reasoned arguments of news media writers to support a particular point you’re making in your argument.

Though this may seem like a topic that wouldn’t generate much scholarly research, it’s worth a shot to check your library database for peer-reviewed studies of student athletes’ experiences in college to see if anything related to paying student athletes pops up. Scholarly research is the holy grail of evidence, so try to find relevant articles if you can.

Ultimately, if you can incorporate a mix of mainstream sources, quantitative or statistical evidence, and scholarly, peer-reviewed sources, you’ll be on-track to building an excellent argument in response to the question, “Should student athletes be paid?”

Having multiple argumentative points in your essay helps you support your thesis.

Tip 4: Develop and Support Multiple Points

We’ve reviewed how to write an intro and thesis statement addressing the issue of paying college athletes, so let’s talk next about the meat and potatoes of your argumentative essay: the body paragraphs.

The body paragraphs that are sandwiched between your intro paragraph and concluding paragraph are where you build and explain your argument. Generally speaking, each body paragraph should do the following:

- Start with a topic sentence that presents a point that supports your stance and that can be debated,

- Present summaries, paraphrases, or quotes from credible sources--evidence, in other words--that supports the point stated in the topic sentence, and

- Explain and interpret the evidence presented with your own, original commentary.

In an argumentative essay on why college athletes should be paid, for example, a body paragraph might look like this:

Thesis Statement : College athletes should not be paid because it would be a logistical nightmare for colleges and universities and ultimately cause negative consequences for college sports.

Body Paragraph #1: While the notion of paying college athletes is nice in theory, a major consequence of doing so would be the financial burden this decision would place on individual college sports programs. A recent study cited by the NCAA showed that only about 20 college athletic programs consistently operate in the black at the present time. If the NCAA allows student-athletes at all colleges and universities to be paid, the majority of athletic programs would not even have the funds to afford salaries for their players anyway. This would mean that the select few athletic programs that can afford to pay their athletes’ salaries would easily recruit the most talented players and, thus, have the tools to put together teams that destroy their competition. Though individual athletes would benefit from the NCAA allowing compensation for student-athletes, most athletic programs would suffer, and so would the spirit of healthy competition that college sports are known for.

If you read the example body paragraph above closely, you’ll notice that there’s a topic sentence that supports the claim made in the thesis statement. There’s also evidence given to support the claim made in the topic sentence--a recent study by the NCAA. Following the evidence, the writer interprets the evidence for the reader to show how it supports their opinion.

Following this topic sentence/evidence/explanation structure will help you construct a well-supported and developed argument that shows your readers that you’ve done your research and given your stance a lot of thought. And that's a key step in making sure you get an excellent grade on your essay!

Tip 5: Keep the Reader Thinking

The best argumentative essay conclusions reinterpret your thesis statement based on the evidence and explanations you provided throughout your essay. You would also make it clear why the argument about paying college athletes even matters in the first place.

There are several different approaches you can take to recap your argument and get your reader thinking in your conclusion paragraph. In addition to restating your topic and why it’s important, other effective ways to approach an argumentative essay conclusion could include one or more of the following:

While you don’t want to get too wordy in your conclusion or present new claims that you didn’t bring up in the body of your essay, you can write an effective conclusion and make all of the moves suggested in the bulleted list above.

Here’s an example conclusion for an argumentative essay on paying college athletes using approaches we just talked about:

Though it’s true that scholarships and financial aid are a form of compensation for college athletes, it’s also true that the current system of college sports places a lot of pressure on college athletes to behave like professional athletes in every way except getting paid. Future research should turn its attention to the various inequities within college sports and look at the long-term economic outcomes of these athletes. While college athletes aren't paid right now, that doesn’t necessarily mean that a paycheck is the best solution to the problem. To avoid the possibility of making the college athletics system even worse, people must consider the ramifications of paying college students and ensure that paying athletes doesn't create more harm than good.

This conclusion restates the argument of the essay (that college athletes shouldn't be paid and why), then uses the "Future Research" tactic to make the reader think more deeply about the topic.

If your conclusion sums up your thesis and keeps the reader thinking, you’ll make sure that your essay sticks in your readers' minds.

Should College Athletes Be Paid: Next Steps

Writing an argumentative essay can seem tough, but with a little expert guidance, you'll be well on your way to turning in a great paper . Our complete, expert guide to argumentative essays can give you the extra boost you need to ace your assignment!

Perhaps college athletics isn't your cup of tea. That's okay: there are tons of topics you can write about in an argumentative paper. We've compiled 113 amazing argumentative essay topics so that you're practically guaranteed to find an idea that resonates with you.

If you're not a super confident essay writer, it can be helpful to look at examples of what others have written. Our experts have broken down three real-life argumentative essays to show you what you should and shouldn't do in your own writing.

Ashley Sufflé Robinson has a Ph.D. in 19th Century English Literature. As a content writer for PrepScholar, Ashley is passionate about giving college-bound students the in-depth information they need to get into the school of their dreams.

Student and Parent Forum

Our new student and parent forum, at ExpertHub.PrepScholar.com , allow you to interact with your peers and the PrepScholar staff. See how other students and parents are navigating high school, college, and the college admissions process. Ask questions; get answers.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

Rhetoric 101

Why ncaa athletes should get paid outline.

The press conferences, the scholarships, the thousands of fans cheering their names— all things that come to mind when talking about college athletes. But what people usually do not think about is all the work and effort that goes into the preparation for the limelight. If you ask any Division 1 college athlete, a typical day is not full of fan-fare, but rather waking up before the sun rises and working out twice a day, attending practices, and of course getting themselves to class.

In the past few years there has been increased speculation on whether college athletes should be paid for the many positives they bring to universities, the NCAA, and television networks. There are many factors to be considered when trying to address one of the most pressing issues in the sports world. How much money there is to go around, which sports get the money, and how to regulate the payment of collegiate athletes—along with many others— are all imperative aspects to bring to light.

The key actors in this dilemma of paying Division 1 athletes are extremely powerful, including the NCAA, television networks, and of course the universities of which these “student-athletes” attend. Hundreds of millions of dollars are made annually in the broadcasting and administration of these sports, yet a fraction seems to go to the actual benefit of daily lives of these athletes.

These organizations make immense amounts of money from the athletic performance of athletes, especially in football, men’s and women’s basketball, as well as men’s hockey. When juxtaposing the time and effort that collegiate athletes are required to put into their craft and the sheer amount of money surrounding college sports, it is clear that these athletes should receive stipends on top of scholarship and perks to help them along their inevitably more difficult college life.

A day in the life of a Division 1 athlete

What is the NCAA?

- talk about them in a general sense and the what they do around college sports

What is the relationship with television networks?

- talk about how the networks bought the rights to broadcast the sports

How much money the NCAA has and what they spend it on

- in depth about spending and where they could cut money

How much universities make with college sports

- talk about each sport separately

- impact with application rates

- how much coaches get paid

Current status of how athletes are treated

- tutors, special locker and weight rooms, gear, scheduling classes advantages

- how larger universities are giving small stipends but needs to more and more broad

- northwestern university attempt to unionize and other examples

- could potentially hurt smaller schools with not as much money

- scholarship and perks already enough for the athletes

- debates over who will get the money

- lose drive for the game

- irresponsible use of money

- scholarships do not cover the added costs of day to day life of a college athlete

- not everyone on the roster gets a full ride

- if the NCAA takes this under its jurisdiction then the burden would be partially or wholly taken off the universities

- eliminates the effect of having athletes transfer to schools who offer more money

- potentially eliminates scandals surrounding paying players and giving them gifts through the school/agents

- kids can eat and buy extra workout clothes when needed, as well as dietary supplements that athletes tend to take

- WHO GETS THE MONEY??

Public Opinion

- racial thing with survey results?

The harsh reality of a college athlete/

- need the extra money to be rewarded for their time

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Bachelor’s Degrees

- Master’s Degrees

- Doctorate Degrees

- Certificate Programs

- Nursing Degrees

- Cybersecurity

- Human Services

- Science & Mathematics

- Communication

- Liberal Arts

- Social Sciences

- Computer Science

- Admissions Overview

- Tuition and Financial Aid

- Incoming Freshman and Graduate Students

- Transfer Students

- Military Students

- International Students

- Early Access Program

- About Maryville

- Our Faculty

- Our Approach

- Our History

- Accreditation

- Tales of the Brave

- Student Support Overview

- Online Learning Tools

- Infographics

Home / Blog

Should College Athletes Be Paid? Reasons Why or Why Not

January 3, 2022

Tables of Contents

Why are college athletes not getting paid by their schools?

How do student athlete scholarships work, what are the pros and cons of compensation for college athletes, keeping education at the center of college sports.

Since its inception in 1906, the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) has governed intercollegiate sports and enforced a rule prohibiting college athletes to be paid. Football, basketball, and a handful of other college sports began to generate tremendous revenue for many schools in the mid-20th century, yet the NCAA continued to prohibit payments to athletes. The NCAA justified the restriction by claiming it was necessary to protect amateurism and distinguish “student athletes” from professionals.

The question of whether college athletes should be paid was answered in part by the Supreme Court’s June 21, 2021, ruling in National Collegiate Athletic Association v. Alston, et. al. The decision affirmed a lower court’s ruling that blocked the NCAA from enforcing its rules restricting the compensation that college athletes may receive.

- As a result of the NCAA v. Alston ruling, college athletes now have the right to profit from their name, image, and likeness (NIL) while retaining the right to participate in their sport at the college level. (The prohibition against schools paying athletes directly remains in effect.)

- Several states have passed laws that allow such compensation. Colleges and universities in those states must abide by these new laws when devising and implementing their own policies toward NIL compensation for college athletes.

Participating in sports benefits students in many ways: It helps them focus, provides motivation, builds resilience, and develops other skills that serve students in their careers and in their lives. The vast majority of college athletes will never become professional athletes and are happy to receive a full or partial scholarship that covers tuition and education expenses as their only compensation for playing sports.

Athletes playing Division I football, basketball, baseball, and other sports generate revenue for their schools and for third parties such as video game manufacturers and media companies. Many of these athletes believe it’s unfair for schools and businesses to profit from their hard work and talent without sharing the profits with them. They also point out that playing sports entails physical risk in addition to a considerable investment in time and effort.

This guide considers the reasons for and against paying college athletes, and the implications of recent court rulings and legislation on college athletes, their schools, their sports, and the role of the NCAA in the modern sports environment.

Back To Top

The reasons why college athletes aren’t paid go back to the first organized sports competitions between colleges and universities in the late 19th century. Amateurism in college sports reflects the “ aristocratic amateurism ” of sports played in Europe at the time, even though most of the athletes at U.S. colleges had working-class backgrounds.

By the early 20th century, college football had gained a reputation for rowdiness and violence, much of which was attributed to the teams’ use of professional athletes. This led to the creation of the NCAA, which prohibited professionalism in college sports and enforced rules restricting compensation for college athletes. The rules are intended to preserve the amateurism of student participants. The NCAA justified the rules on two grounds:

- Fans would lose interest in the games if the players were professional athletes.

- Limiting compensation to capped scholarships ensures that college athletes remain part of the college community.

NCAA rules also prohibited college athletes from receiving payment to “ advertise, recommend, or promote ” any commercial product or service. Athletes were barred from participating in sports if they signed a contract to be represented by an agent as well. As a result of the NIL court decision, the NCAA will no longer enforce its rule relating to compensation for NIL activities and will allow athletes to sign contracts with agents.

Major college sports now generate billions in revenue for their schools each year

For decades, colleges and universities have operated under the assumption that scholarships are sufficient compensation for college athletes. Nearly all college sports cost more for the schools to operate than they generate in revenue for the institution, and scholarships are all that participants expect.

But while most sports don’t generate revenue, a handful, notably football and men’s and women’s basketball, stand out as significant exceptions to the rule:

- Many schools that field teams in the NCAA’s Division I football tier regularly earn tens of millions of dollars each year from the sport.

- The NCAA tournaments for men’s and women’s Division I basketball championships generated more than $1 billion in 2019 .

Many major colleges and universities generate a considerable amount of money from their athletic teams:

- The Power Five college sports conferences — the Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC), Big Ten, Big 12, Pac 12, and Southeastern Conference (SEC) — generated more than $2.9 billion in revenue from sports in fiscal 2020, according to federal tax records reported by USA Today .

- This figure represents an increase of $11 million from 2019, a total that was reduced because of restrictions related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- In the six years prior to 2020, the conferences recorded collective annual revenue increases averaging about $252 million.

What are name, image, likeness agreements for student athletes?

In recent years some college athletes at schools that field teams in the NCAA’s highest divisions have protested the restrictions placed on their ability to be compensated for third parties’ use of their name, image, and likeness. During the 2021 NCAA Division I basketball tournament known familiarly as March Madness, several players wore shirts bearing the hashtag “ #NotNCAAProperty ” to call attention to their objections.

Following the decision in NCAA v. Alston, the NCAA enacted a temporary policy allowing college athletes to enter into NIL agreements and other endorsements. The interim policy will be in place until federal legislation is enacted or new NCAA rules are created governing NIL contracts for college athletes.

- Student athletes are now able to sign endorsement deals, profit from their use of social media, and receive compensation for personal appearances and signing autographs.

- If they attend a school located in a state that has enacted NIL legislation, they are subject to any restrictions present in those state laws. As of mid-August 2021, 40 states had enacted laws governing NIL contracts for college athletes.

- If their school is in a state without such a law, the college or university will determine its own NIL policies, although the NCAA prohibits pay-for-play and improper recruiting inducements.

- Student athletes are allowed to sign with sports agents and enter into agreements with school boosters so long as the deals abide by state laws and school policies.

Within weeks of the NCAA policy change, premier college athletes began signing NIL agreements with the potential to earn them hundreds of thousands of dollars .

- Bryce Young, a sophomore quarterback for the University of Alabama, has nearly $1 million in endorsement deals.

- Quarterback Quinn Ewers decided to skip his last year of high school and enroll early at Ohio State University so he could make money from endorsements.

- A booster for the University of Miami pledged to pay each member of the school’s football team $500 for endorsing his business.

How will the change affect college athletes and their schools?

The repercussions of court decisions and state laws that allow college athletes to sign NIL agreements continue to be felt at campuses across the country, even though schools and athletes have received little guidance on how to manage the process.

- The top high school athletes in football, basketball, and other revenue-generating college sports will consider their potential for endorsement earnings while being recruited by various schools.

- The first NIL agreements highlight the disparity between what elite college athletes can expect to earn and what other athletes may realize. On one NIL platform, the average amount earned by Division I athletes was $471, yet one athlete made $210,000 in July alone.

- Most NIL deals at present are for small amounts, typically about $100 in free apparel, in exchange for endorsing a product on social media.

The presidents and other leaders of colleges and universities that field Division I sports have not yet responded to the changes in college athlete compensation other than to reiterate that they do not operate for-profit sports franchises. However, the NCAA requires that Division I sports programs be self-supporting, in contrast to sports programs at Division II and III institutions, which receive funding directly from their schools.

Many members of the Power 5 sports conferences have reported shortfalls in their operations, leading analysts to anticipate major structural reforms in the governing of college sports in the near future. The recent changes have also caused some people to believe the NCAA is no longer relevant or necessary.

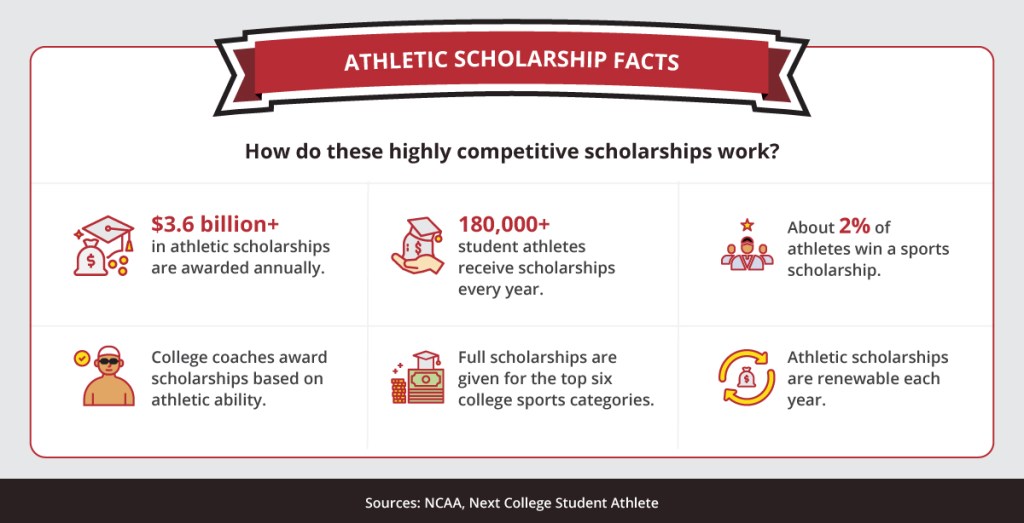

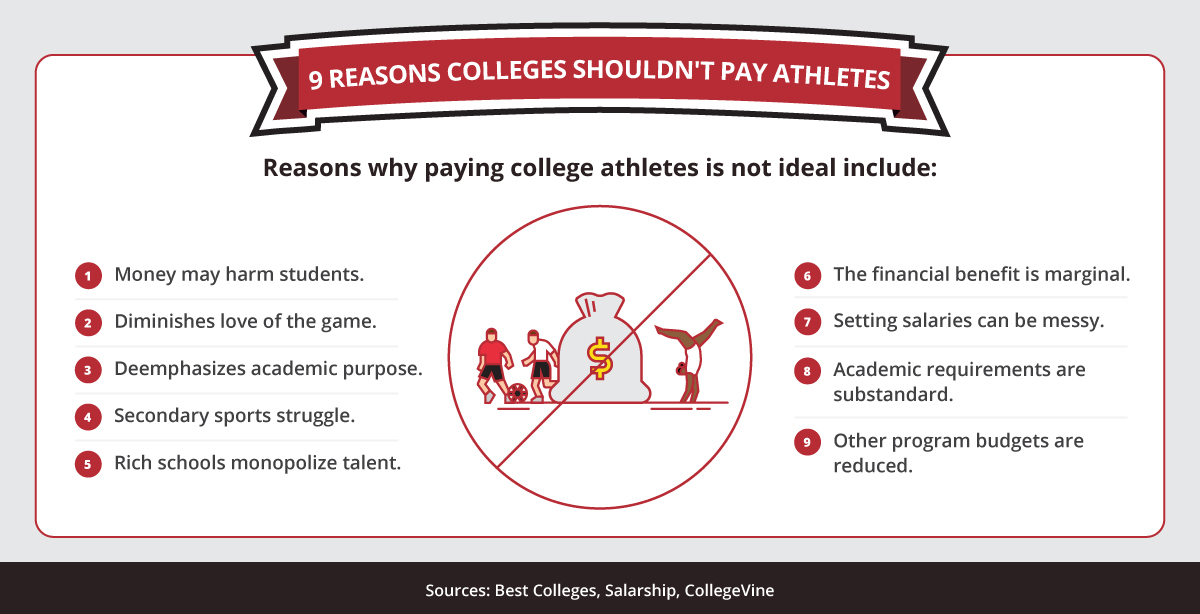

How do highly competitive athletic scholarships work? According to the NCAA and Next College Student Athlete: $3.6 billion+ in athletic scholarships are awarded annually, and 180,000+ student athletes receive scholarships every year. Additionally, about 2% of athletes win a sports scholarship; college coaches award scholarships based on athletic ability; full scholarships are given for the top six college sports categories; and athletic scholarships are renewable each year.

The primary financial compensation student athletes receive is a scholarship that pays all or part of their tuition and other college-related expenses. Other forms of financial assistance available to student athletes include grants, loans, and merit aid .

- Grants are also called “gift aid,” because students are not expected to pay them back (with some exceptions, such as failing to complete the course of study for which the grant was awarded). Grants are awarded based on a student’s financial need. The four types of grants awarded by the U.S. Department of Education are Federal Pell Grants , Federal Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grants , Iraq and Afghanistan Service Grants , and Teacher Education Assistance for College or Higher Education (TEACH) Grants .

- Loans are available to cover education expenses from government agencies and private banks. Students must pay the loans back over a specified period after graduating from or leaving school, including interest charges. EducationData.org estimates that as of 2020, the average amount of school-related debt owed by college graduates was $37,693.

- Merit aid is awarded based on the student’s academic, athletic, artistic, and other achievements. Athletic scholarships are a form of merit aid that typically cover one academic year at a time and are renewable each year, although some are awarded for up to four years.

Full athletic scholarships vs. partial scholarships

When most people think of a student athlete scholarship, they have in mind a full-ride scholarship that covers nearly all college-related expenses. However, most student athletes receive partial scholarships that may pay tuition but not college fees and living expenses, for example.

A student athlete scholarship is a nonguaranteed financial agreement between the school and the student. The NCAA refers to full-ride scholarships awarded to student athletes entering certain Division I sports programs as head count scholarships because they are awarded per athlete. Conversely, equivalency sports divide scholarships among multiple athletes, some of whom may receive a full scholarship and some a partial scholarship. Equivalency awards are divided among a team’s athletes at the discretion of the coaches, as long as they do not exceed the allowed scholarships for their sport.

These Division I sports distribute scholarships per head count:

- Men’s football

- Men’s basketball

- Women’s basketball

- Women’s volleyball

- Women’s gymnastics

- Women’s tennis

These are among the Division I equivalency sports for men:

- Track and field

- Cross-country

These are the Division I equivalency sports for women:

- Field hockey

All Division II and National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA) sports programs distribute scholarships on an equivalency basis. Division III sports programs do not award sports scholarships, although other forms of financial aid are available to student athletes at these schools.

How college athletic scholarships are awarded

In most cases, the coaching staff of a team determines which students will receive scholarships after spending time scouting and recruiting. The NCAA imposes strict rules for recruiting student athletes and provides a guide to help students determine their eligibility to play college sports.

Once a student has received a scholarship offer from a college or university, the person may sign a national letter of intent (NLI), which is a voluntary, legally binding contract between an athlete and the school committing the student to enroll and play the designated sport for that school only. The school agrees to provide financial aid for one academic year as long as the student is admitted and eligible to receive the aid.

After the student signs an NLI, other schools are prohibited from recruiting them. Students who have signed an NLI may ask the school to release them from the commitment; if a student attends a school other than the one with which they have an NLI agreement, they lose one full year of eligibility and must complete a full academic year at the new school before they can compete in their sport.

Very few student athletes are awarded a full scholarship, and even a “full” scholarship may not pay for all of a student’s college and living expenses. The average Division I sports scholarship in the 2019-20 fiscal year was about $18,000, according to figures compiled by ScholarshipStats.com, although some private universities had average scholarship awards that were more than twice that amount. However, EducationData.org estimates that the average cost of one year of college in the U.S. is $35,720. They estimate the following costs by type of school.

- The average annual cost for an in-state student attending a public four-year college or university is $25,615.

- Average in-state tuition for one year is $9,580, and out-of-state tuition costs an average of $27,437.

- The average cost at a private university is $53,949 per academic year, about $37,200 of which is tuition and fees.

Student athlete scholarship resources

- College Finance, “Full-Ride vs. Partial-Ride Athletic Scholarships” — The college expenses covered by full athletic scholarships, how to qualify for partial athletic scholarships, and alternatives to scholarships for paying college expenses

- Student First Educational Consulting, “Athletic Scholarship Issues for 2021-2022 and Beyond” — A discussion of the decline in the number of college athletic scholarships as schools drop athletic programs, and changes to the rules for college athletes transferring to new schools

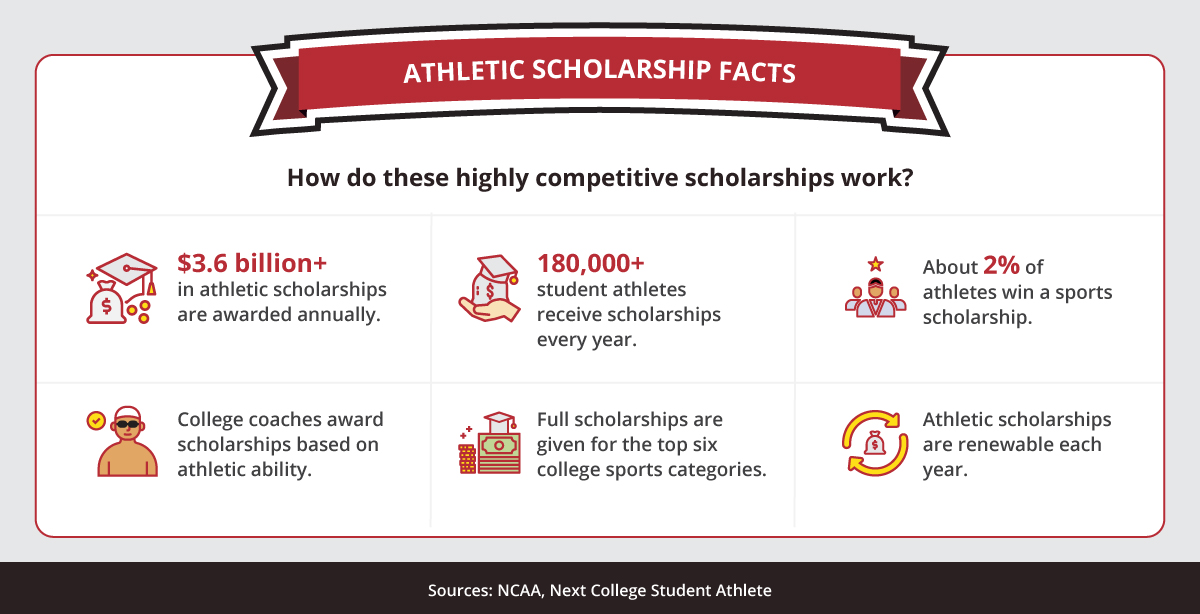

According to College Strategic, Fansided, and Future of Working, reasons why paying college athletes is fair include: 1. Playing sports resembles a full-time job. 2. Sports take time away from studies. 3. Sports generate corporate profits. 4. Pay minimizes athlete corruption. 5. Pay provides spending money. 6. Playing sports creates injury risk. 7. Sports elevate school brands. 8. Pay motivates performance. 9. Scholarships reduce poverty.

There are many reasons why student athletes should be paid, but there are also valid reasons why student athletes should not be paid in certain circumstances. The lifting of NCAA restrictions on NIL agreements for college athletes has altered the landscape of major college sports but will likely have little or no impact on the majority of student athletes, who will continue to compete as true amateurs.

Reasons why student athletes should be paid

The argument raised most often in favor of allowing college athletes to receive compensation is that colleges and universities profit from the sports they play but do not share the proceeds with the athletes who are the ultimate source of that profit.

- In 2017 (the most recent year for which figures are available), the NCAA recorded $1.07 billion in revenue. The organization’s president earned $2.7 million in 2018, and nine other NCAA executives had salaries greater than $500,000 that year.

- Elite college coaches earn millions of dollars a year in salary, topped by University of Alabama football coach Nick Saban’s $9.3 million annual salary.

- Many of the athletes at leading football and basketball programs are from low-income families, and the majority will not become professional athletes.

- College athletes take great physical risks to play their sports and put their future earning potential at risk. In school they may be directed toward nonchallenging courses, which denies them the education their fellow students receive.

Reasons why student athletes should not be paid

Opponents to paying college athletes rebut these arguments by pointing to the primary role of colleges and universities: to provide students with a rewarding educational experience that prepares them for their professional careers. These are among the reasons they give for not paying student athletes.

- Scholarships are the fairest form of compensation for student athletes considering the financial strain that college athletic departments are under. Most schools in Division I, II, and III spend more money on athletics than they receive in revenue from the sports.

- College athletes who receive scholarships are presented with an opportunity to earn a valuable education that will increase their earning power throughout their career outside of sports. A Gallup survey of NCAA athletes found that 70% graduate in four years or fewer , compared to 65% of all undergraduate students.

- Paying college athletes will “ diminish the spirit of amateurism ” that distinguishes college sports from their professional counterparts. Limiting compensation for playing a sport to the cost of attending school avoids creating a separate class of students who are profiting from their time in school.

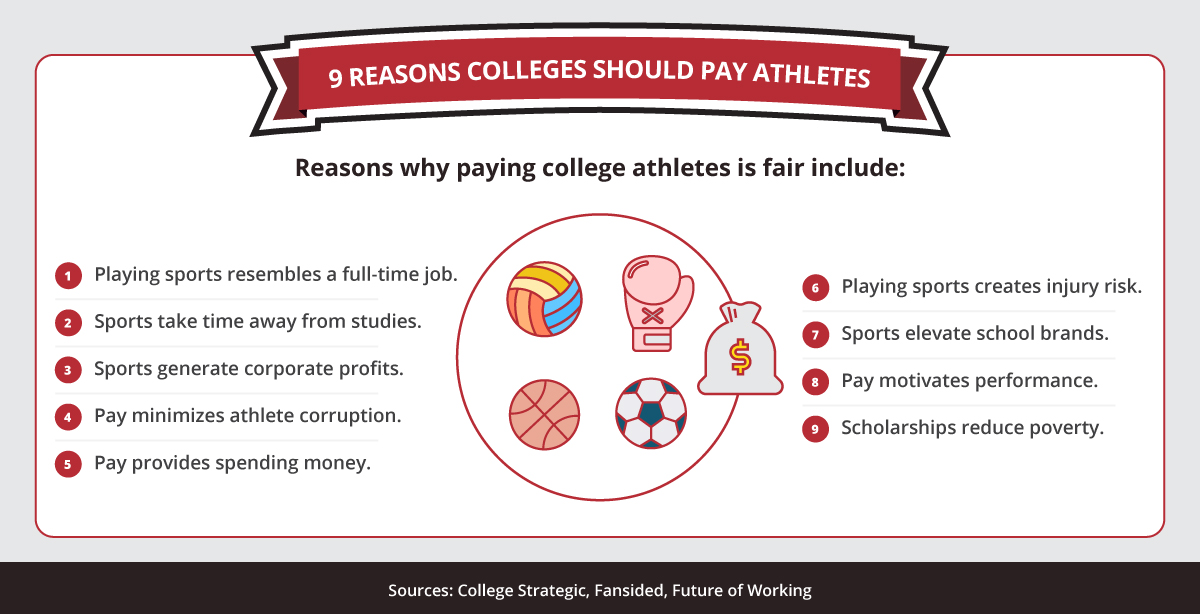

According to Best Colleges, Salarship, and CollegeVine, reasons why paying college athletes is less than ideal include: 1. Money may harm students. 2. Pay diminishes love of the game. 3. Pay deemphasizes academic purpose. 4. Secondary sports struggle. 5. Rich schools monopolize talent. 6. The financial benefit is marginal. 7. Setting salaries can be messy. 8. Academic requirements are substandard. 9. Other program budgets are reduced.

How do college athlete endorsements work?

Soon after the Supreme Court released its decision in NCAA v. Alston, the NCAA issued guidelines for schools that allow college athletes to make money from product endorsements, social media accounts, autographs, and other uses of their name, image, or likeness. This counters the NCAA’s longstanding opposition to student athletes profiting from endorsements. At present, implementation of the guidelines varies from school to school and state to state, which means athletes at some institutions may benefit more from NIL agreements than those attending other schools.

Several NIL consultancy firms are actively soliciting endorsements from college athletes in the aftermath of the rule change.

- Highly touted 19-year-old basketball recruit Hercy Miller, who joined the Tennessee State University basketball team in 2021, signed a $2 million endorsement deal with Web Apps America.

- University of Michigan quarterback Cade McNamara has entered into an endorsement deal with cryptocurrency company More Management that will pay him in cryptocurrency .

- Twin sisters Haley and Hanna Cavinder of the Fresno State University basketball team have marketing agreements to promote Boost Mobile and Six Star Pro Nutrition to the 3.3 million followers of their TikTok account.

- Gable Steveson, a wrestler for the University of Minnesota, entered into an endorsement deal with the delivery service Gopuff; Steveson has 245,000 followers on Instagram and 30,000 on Twitter.

Despite the rush of high-profile college athletes signing endorsement deals, some educators and analysts express concern about the impact of the endorsements on schools, athletes, and college sports.

- Schools with more favorable endorsement rules may entice student athletes away from the schools they are currently attending.

- Likewise, states that have enacted endorsement laws that provide more earning potential for college athletes may see more top recruits choosing to attend schools in those states.

- The time college athletes spend meeting the requirements of their endorsement contracts could detract from study and practice time. This can have an adverse effect on their education and athletic careers — if they are unable to maintain grade requirements, for example, they may be disqualified from playing.

- If a college athlete’s performance in the sport declines, they may be less likely to attract and retain endorsement deals. While the NCAA has banned NIL agreements based on the athlete meeting specific performance criteria, the group acknowledges that a student’s athletic performance may enhance their NIL value .

- Because of complicated contracts and tax laws, student athletes will have to rely on agents, advisers, and managers, which may leave them vulnerable to exploitation.

From the onset of intercollegiate sports, students have benefited from their participation by learning dedication to their sport, building relationships, and being part of a team. Sports allow students to acquire many important values, such as fair competition and physical and mental health. Education should remain at the forefront of all aspects of college, including sports, whether or not collegiate athletes are paid.

Infographic Source

Best Colleges, “Should College Athletes Be Paid?”

College Strategic, “Why College Athletes Should Be Paid”

CollegeVine, “Should College Athletes Be Paid? Pros and Cons”

Fansided, “64 Reasons College Athletes Need to Be Paid”

Future of Working, “17 Advantages and Disadvantages of Paying College Athletes”

NCAA, “Scholarships”

Next College Student Athlete, “What Are the Different Types of Offers I Could Get?”

Salarship, “Should College Athletes Be Paid: Pros and Cons”

Bring us your ambition and we’ll guide you along a personalized path to a quality education that’s designed to change your life.

Take Your Next Brave Step

Receive information about the benefits of our programs, the courses you'll take, and what you need to apply.

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

The Case for Paying College Athletes

The case against paying college athletes, the era of name, image, and likeness (nil) profiting, why should college athletes be paid, is it illegal for college athletes to get paid, what percentage of americans support paying college athletes, the bottom line, should college athletes be paid.

The Case For and Against

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Headshot-4c571aa3d8044192bcbd7647dd137cf1.jpg)

Should college athletes be able to make money from their sport? When the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) was founded in 1906, the organization’s answer was a firm “no,” as it sought to “ensure amateurism in college sports.”

Despite the NCAA’s official stance, the question has long been debated among college athletes, coaches, sports fans, and the American public. The case for financial compensation saw major developments in June 2021, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the NCAA cannot limit colleges from offering student-athletes “education-related benefits.”

In response, the NCAA issued an interim policy stating that its student-athletes were permitted to profit off their name, image, and likeness (NIL) , but not to earn a salary. This policy will remain in place until a more “permanent solution” can be found in conjunction with Congress.

Meanwhile, the landscape continues to shift, with new cases, decisions, and state legislation being brought forward. College athletes are currently permitted to receive “cost of attendance” stipends (up to approximately $6,000), unlimited education-related benefits, and awards. A 2023 survey found that 67% of U.S. adults favor paying college athletes with direct compensation.

Key Takeaways

- Despite the NCAA reporting nearly $1.3 billion in revenue in 2023, student-athletes are restricted to limited means of compensation.

- Although college sports regularly generate valuable publicity and billions of dollars in revenue for schools, even the highest-grossing college athletes tend to see only a small fraction of this.

- One argument for paying college athletes is the significant time commitment that their sport requires, which can impact their ability to earn income and divert time and energy away from academic work.

- Student-athletes may face limited prospects after college for a variety of reasons, including a high risk of injury, fierce competition to enter professional leagues, and lower-than-average graduation rates.

- The developing conversation around paying college athletes must take into account the practical challenges of determining and administering compensation, as well as the potential impacts on players and schools.

There are numerous arguments in support of paying college athletes, many of which focus on ameliorating the athletes’ potential risks and negative impacts. Here are some of the typical arguments in favor of more compensation.

Financial Disparity

College sports generate billions of dollars in revenue for networks, sponsors, and institutions (namely schools and the NCAA). There is considerable money to be made from advertising and publicity, historically, most of which has not benefited those whose names, images, and likenesses are featured within it.

Of the 2019 NCAA Division I revenues ($15.8 billion in total), only 18.2% was returned to athletes through scholarships, medical treatment, and insurance. Additionally, any other money that goes back to college athletes is not distributed equally. An analysis of players by the National Bureau of Economic Research found major disparities between sports and players.

Nearly 50% of men’s football and basketball teams, the two highest revenue-generating college sports, are made up of Black players. However, these sports subsidize a range of other sports (such as men’s golf and baseball, and women’s basketball, soccer, and tennis) where only 11% of players are Black and which also tend to feature players from higher-income neighborhoods. In the end, financial redistribution between sports effectively funnels resources away from students who are more likely to be Black and come from lower-income neighborhoods toward those who are more likely to be White and come from higher-income neighborhoods.

Exposure and Marketing Value

Colleges’ finances can benefit both directly and indirectly from their athletic programs. The “Flutie Effect,” named after Boston College quarterback Doug Flutie, is an observed phenomenon whereby college applications and enrollments seem to increase after an unexpected upset victory or national football championship win by that college’s team. Researchers have also suggested that colleges that spend more on athletics may attract greater allocations of state funding and boost private donations to institutions.

Meanwhile, the marketing of college athletics is valued in the millions to billions of dollars. In 2023, the NCAA generated nearly $1.3 billion in revenue, $945.1 million of which came from media rights fees. In 2022, earnings from March Madness represented nearly 90% of the NCAA’s total revenue. Through this, athletes give schools major exposure and allow them to rack up huge revenues, which argues for making sure the players benefit, too.

Opportunity Cost, Financial Needs, and Risk of Injury

Because participation in college athletics represents a considerable commitment of time and energy, it necessarily takes away from academic and other pursuits, such as part-time employment. In addition to putting extra financial pressure on student-athletes, this can impact athletes’ studies and career outlook after graduation, particularly for those who can’t continue playing after college, whether due to injury or the immense competition to be accepted into a professional league.

Earning an income from sports and their significant time investment could be a way to diminish the opportunity cost of participating in them. This is particularly true in case of an injury that can have a long-term effect on an athlete’s future earning potential.

Arguments against paying college athletes tend to focus on the challenges and implications of a paid-athlete system. Here are some of the most common objections to paying college athletes.

Existing Scholarships

Opponents of a paid-athlete system tend to point to the fact that some college athletes already receive scholarships , some of which cover the cost of their tuition and other academic expenses in full. These are already intended to compensate athletes for their work and achievements.

Financial Implications for Schools

One of the main arguments against paying college athletes is the potential financial strain on colleges and universities. The majority of Division I college athletics departments’ expenditures actually surpass their revenues, with schools competing for players by hiring high-profile coaches, constructing state-of-the-art athletics facilities, and offering scholarships and awards.

With the degree of competition to attract talented athletes so high, some have pointed out that if college athletes were to be paid a salary on top of existing scholarships, it might unfairly burden those schools that recruit based on the offer of a scholarship.

‘Amateurism’ and the Challenges of a Paid-Athlete System

Historically, the NCAA has sought to promote and preserve a spirit of “amateurism” in college sports, on the basis that fans would be less interested in watching professional athletes compete in college sports, and that players would be less engaged in their academic studies and communities if they were compensated with anything other than scholarships.

The complexity of determining levels and administration of compensation across an already uneven playing field also poses a practical challenge. What would be the implications concerning Title IX legislation, for example, since there is already a disparity between male and female athletes and sports when it comes to funding, resources, opportunities, compensation, and viewership?

Another challenge is addressing the earnings potential of different sports (as many do not raise revenues comparable to high-profile sports like men’s football and basketball) or of individual athletes on a team. Salary disparities would almost certainly affect team morale and drive further competition between schools to bid for the best athletes.

In 2021, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the NCAA violated antitrust laws with its rules around compensation, holding that the NCAA’s current rules were “more restrictive than necessary” and that the NCAA could no longer “limit education-related compensation or benefits” for Division I football and basketball players.

In response, the NCAA released an interim policy allowing college athletes to benefit from their name, image, and likeness (NIL) , essentially providing the opportunity for players to profit off their personal brand through social media and endorsement deals. States then introduced their own rules around NIL, as did individual schools, whose coaches or compliance departments maintain oversight of NIL deals and the right to object to them in case of conflict with existing agreements.

Other court cases against the NCAA have resulted in legislative changes that now allow students to receive “cost of attendance” stipends up to a maximum of around $6,000 as well as unlimited education-related benefits and awards.

The future of NIL rules and student-athlete compensation remains to be seen. According to the NCAA, the intention is to “develop a national law that will help colleges and universities, student-athletes, and their families better navigate the name, image, and likeness landscape.” However, no timeline has been specified as of yet.

Common arguments in support of paying college athletes tend to focus on players’ financial needs, their high risk of injury, and the opportunity cost they face (especially in terms of academic achievement, part-time work, and long-term financial and career outlook). Proponents of paying college athletes also point to the extreme disparity between the billion-dollar revenues of schools and the NCAA and current player compensation.

Although the NCAA once barred student-athletes from earning money from their sport, legislation around compensating college athletes is changing. In 2021, the NCAA released an interim policy permitting college athletes to profit off their name, image, and likeness (NIL) through social media and endorsement and sponsorship deals. However, current regulations and laws vary by state.

In 2023, a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults found that 67% of respondents were in favor of paying college athletes with direct compensation. Sixty-four percent said they supported athletes’ rights to obtain employee status, and 59% supported their right to collectively bargain as a labor union .

Although the NCAA is under growing pressure to share its billion-dollar revenues with the athletes it profits from, debate remains around whether, how, and how much college athletes should be paid. Future policy and legislation will need to take into account the financial impact on schools and athletes , the value of exposure and marketing, pay equity and employment rights, pay administration, and the nature of the relationship between college athletes and the institutions they represent.

NCAA. “ History .”

Marquette Sports Law Review. “ Weakening Its Own Defense? The NCAA’s Version of Amateurism ,” Page 260 (Page 5 of PDF).

U.S. Supreme Court. “ National Collegiate Athletic Association v. Alston et al. ”

NCAA. “ NCAA Adopts Interim Name, Image and Likeness Policy .”

PBS NewsHour. “ Analysis: Who Is Winning in the High-Revenue World of College Sports? ”

Sportico. “ 67% of Americans Favor Paying College Athletes: Sportico/Harris Poll .”

Sportico. “ NCAA Took in Record Revenue in 2023 on Investment Jump .”

National Bureau of Economic Research. “ Revenue Redistribution in Big-Time College Sports .”

Appalachian State University, Walker College of Business. “ The Flutie Effect: The Influence of College Football Upsets and National Championships on the Quantity and Quality of Students at a University .”

Grand Canyon University. “ Should College Athletes Be Paid? ”

Flagler College Gargoyle. “ Facing Inequality On and Off the Court: The Disparities Between Male and Female Athletes .”

U.S. Department of Education. “ Title IX and Sex Discrimination .”

Congressional Research Service Reports. “ National Collegiate Athletic Association v. Alston and the Debate Over Student Athlete Compensation .”

NCSA College Recruiting. “ NCAA Name, Image, Likeness Rule .”

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/GettyImages-151311702-a935ed8794c64194a53b5741d4be05f3.jpg)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

Should College Athletes Be Paid? Pros and Cons

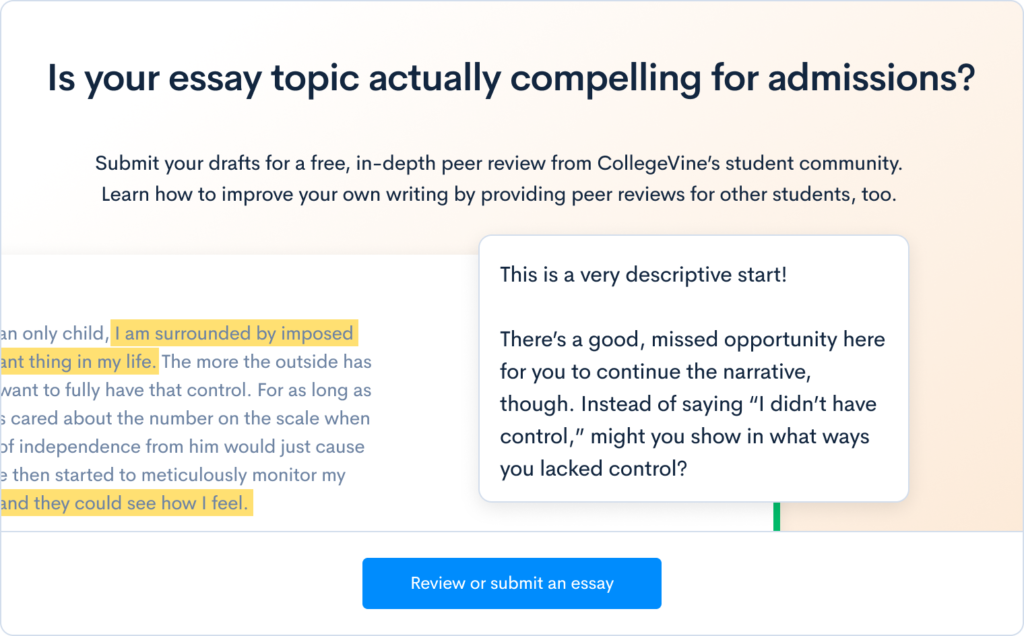

Do you know how to improve your profile for college applications.

See how your profile ranks among thousands of other students using CollegeVine. Calculate your chances at your dream schools and learn what areas you need to improve right now — it only takes 3 minutes and it's 100% free.

Show me what areas I need to improve

What’s Covered:

History of the debate: should college athletes be paid, why college athletes should be paid.

- Why College Athletes Shouldn’t Be Paid

- Where To Get Your Essay Edited For Free

College athletics provide big benefits for many schools: they increase their profile, generate millions of dollars in revenue, and have led to one of the most contentious questions in sports— should college athletes be paid? Like other difficult questions, there are good arguments on both sides of the issue of paying college athletes.

Historically, the debates over paying college athletes have only led to more questions, which is why it’s raged on for more than a century. Perhaps the earliest group to examine the quandary was Andrew Carnegie’s Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, which produced a mammoth study in 1929 of amateur athletes and the profits they generate for their universities. You don’t have to get past the preface to find questions that feel at home in today’s world:

- “What relation has this astonishing athletic display to the work of an intelligence agency like a university?”

- “How do students, devoted to study, find either the time or the money to stage so costly a performance?”

Many of the questions asked way back in 1929 continue to resurface today, and many of them have eventually ended up seeking answers in court. The first case of note came in the 1950s, when the widow of Fort Lewis football player Ray Dennison took the college all the way to the Colorado Supreme Court in an effort to collect a death benefit after he was killed playing football. She lost the case, but future generations would have more success and have slowly whittled away at arguments against paying athletes.

The most noticeable victory for athletes occurred in 2019, when California Governor, Gavin Newsom, signed legislation effectively allowing college athletes in the state to earn compensation for the use of their likeness, sign endorsement deals, and hire agents to represent them.

The court fights between college athletes and the NCAA continue today—while not exactly about payment, a case regarding whether or not schools can offer athletes tens of thousands of dollars in education benefits such as computers, graduate scholarships, tutoring, study abroad, and internships was heard by the U.S. Supreme Court in March 2021. A decision is expected in June 2021.

There are a number of great reasons to pay college athletes, many of which will not only improve the lives of student-athletes, but also improve the product on the field and in the arena.

College Athletes Deserve to Get Paid

In 2019, the NCAA reported $18.9 billion in total athletics revenue. This money is used to finance a variety of paid positions that support athletics at colleges and universities, including administrators, directors, coaches, and staff, along with other employment less directly tied to sports, such as those in marketing and media. The only people not receiving a paycheck are the stars of the show: the athletes.

A testament to the disparate allocation of funds generated by college sports, of the $18.9 billion in athletics revenue in 2019, $3.6 billion went toward financial aid for student-athletes, and $3.7 billion was used for coaches’ compensation. A February 2020 USA Today article found that the average total pay for Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) college football head coaches in 2020-21 was $2.7 million. The highest-paid college football coach—the University of Alabama’s Nick Saban—earns $9.3 million a year and is the highest-paid public employee in the country. He is not alone, college coaches dominate the list of public employees with the largest salaries.

If there’s money to provide college coaches with lavish seven-figure salaries (especially at public institutions), why shouldn’t there be funds to pay college athletes?

Vital Support for Athletes

A 2011 study published by the National College Players Association (NCPA) found that an overwhelming number of students on full athletics scholarships live below the federal poverty line—85% of athletes who live on campus and 86% athletes who live off-campus. “Full scholarship” itself is a misnomer; the same study found that the average annual scholarship for FBS athletes on “full” scholarships was actually $3,222. Find out more information about athletic scholarships .

Paying student-athletes would help eliminate the need for these student-athletes to take out loans, burden their families for monetary support, or add employment to their already busy schedules. The NCAA limits in-season practice time to 20 hours a week, but a 2008 NCAA report shows that in-season student-athletes commonly spent upward of 30 and 40 hours a week engaged in “athletic activities.”

Encouraged to Stay in College Longer