- Corrections

How Photography Pioneered a New Understanding of Art

The advent of photography significantly changed how art was perceived and gave way to new artistic movements. These movements transformed the way we think about art.

The earliest widely available photographic process was made public in 1839 by Louis Daguerre, creator of the Daguerreotype. The popularization of photography caused a great stir in the art world and led to significant changes in how art was perceived. Since photography could depict the world more accurately than painting, the latter had to reinvent itself. For this reason, the focus of painters shifted from representing reality to portraying emotions and impressions. Photography can, for this reason, be seen as a great drive for the reinvention of painting that occurred in the late 19th and throughout the 20th century.

When and How Did Photography First Appear?

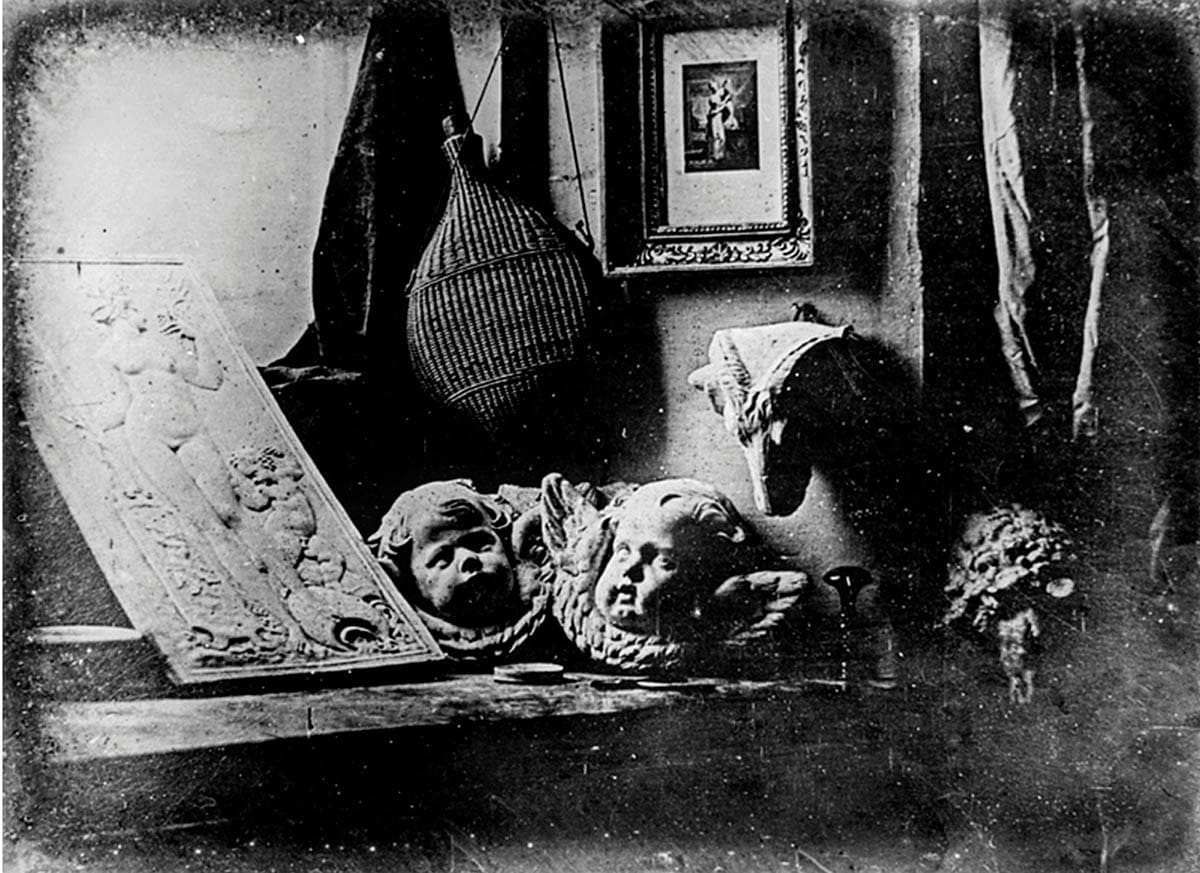

The first successful photographic process, the Daguerreotype , was created in 1837 by Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre. Daguerre had previously worked as a professional scene painter at a theater. For this reason, he already knew the camera obscura , a small, darkened room with a tiny hole or lens which allowed an image from the outside through. Daguerre took inspiration from this process in order to create the world’s first photographic camera.

The camera obscura had already been used for centuries and allowed the reflection of images from the outside world on a flat surface. Until Daguerre, the main difficulty had been to engrave the image produced without having to draw over it on a piece of paper. Even after other inventors in the 19th century managed to transfer the image onto a piece of copper, the image quickly disappeared when exposed to light. Before Daguerre, it was impossible for a photograph to leave the darkroom in which it was produced.

However, Daguerre didn’t engrave the images on paper but rather on silver-coated copper plates. This invention was announced to the public by a friend, Dominique François Jean Arago, in 1839. From there on, this new process spread throughout the world. In late 1839, daguerreotypes began being produced in several different industrialized nations. Due to how quickly it spread, this new invention was quickly perfected by several manufacturers.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Please check your inbox to activate your subscription.

It was in the United Kingdom in the early 1840s that the first European photography studios appeared. Revelation times decreased significantly, from Daguerre’s thirty minutes to only twenty seconds in most studios. In the late 1880s, George Eastman created the first film rolls. From there on, photographers didn’t need to carry silver-coated copper plates around, and photography became cheaper and more accessible.

Reception of Photography: The Democratization of Art

Photography had a significant impact in 19th-century society and its reception within artistic circles varied . While some welcomed photography and used it as an aid for their artistic production, others criticized this invention and refused to consider it as worthwhile for artists, as did Gustave Courbet .

Regardless of the differing receptions of photography, this invention revolutionized 19th-century European societies. For the first time, art had become affordable not only for the higher classes but also for the lower ones. Middle-class and lower-class families could have their portraits done almost instantly at a photography studio for relatively affordable prices.

It can be said that there was, for the first time, a democratization of art and image. While some reacted positively to this and the accessibility of art throughout society, others saw it as a banalization of artistic creation. Many were critical of photography and saw it only as an industrial imitation of art for commercial purposes.

Art Before the Advent of Photography

Despite their variations, the artistic movements in Europe before the 19th century had always had realism as their focus . Their change and variation manifested primarily in thematic change (what was painted) or technique, but realistic representation had always been valued in all of them.

At the time of the invention and spreading of photography, the leading art movements in Europe were Romanticism and Neoclassicism . The first had already introduced a shift in the artistic world by emphasizing the artist’s expression.

In Romanticist painting, there were many elements that did not belong to reality (supernatural elements, for example) but were nevertheless represented realistically.

In Neoclassical painting, there was a revival of the representation of mythological figures and scenes. As beautifully and harmoniously as possible, these were always represented in great detail and accuracy. Even if some artists didn’t fall within these artistic movements, they still painted realistically. Whether it was human subjects, nature, or mythological figures, what European paintings at the time had in common was their aim at representing images as accurately and in as much detail as possible.

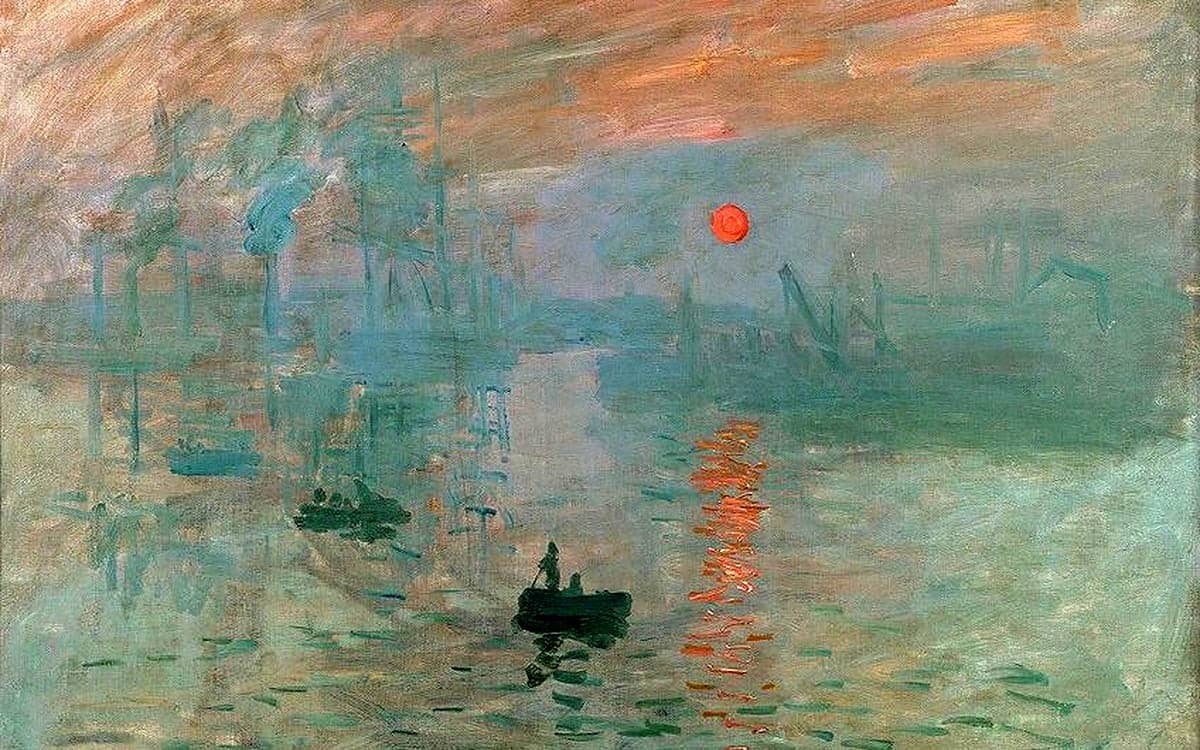

Impressionism: An Art Movement Shaped by Photography

Painters who witnessed the advent of photography developed a different perception of reality and images than their predecessors. These artists understood that reality was transient and that each moment was fleeting and limited. The nature of reality, these painters realized, was to be in constant movement.

For this reason, the artistic movement of Impressionism was the first to deviate from the realistic norm in European art. The artists of Impressionism accepted that photography was the best for capturing fixed images and that they could not outdo it. For this reason, impressionists explored other dimensions of painting, such as color, light, and movement. This style made it clear that painting was not meant to compete with photography, but rather to complement it, to represent that which photography couldn’t.

Impressionist painters, instead of accurately representing reality in detail, focus on the impression of reality and attempt to convey movement in their paintings . Impressionist paintings represent reality as perceived by the human eye: fleeting and transient, sometimes unclear or blurred. At first, these somewhat blurred representations of reality were criticized as low-quality or unfinished paintings, but in time they came to be appreciated.

From this time on, it became widely accepted that painting could not compete with photography in accurately representing reality. This realization, in a way, released painting from the shackles of realism and opened the door for a shift in artistic circles. Instead of valuing realism, artists began focusing on expressing emotions, impressions, and all that which is part of the human experience. In many ways, Impressionism created a bridge between traditional art, which had realism at its core, and modernist art, which distanced itself from an accurate representation of reality.

The Modernist Art Movement: A New Conception of Art

By the beginning of the 20th century , it was clear that photography had come to stay. Not only that but there was another brand-new medium for representing reality: film. After an 1895 film projection in Paris by the Lumière brothers, this new medium was quickly improved and gained significant popularity. Representing reality accurately was no longer a necessary task for painters. For this reason, Impressionism was only the first of a series of artistic movements which strayed away from realism.

During the first half of the 20th century, there were multiple movements within Modernism that transformed the art world. The first was Fauvism , which represented real scenes and subjects using bright colors which usually did not correspond with reality. Fauvists used thick brushstrokes, taking inspiration from Post-Impressionist painters such as Vincent van Gogh. The foremost name in Fauvism was Henri Matisse. When asked what the color of the lady’s dress in his famous painting Woman with a Hat was, he allegedly replied: “ Black, obviously .”

One of the earliest movements within the Modernist current was Expressionism , which had its origins in Van Gogh and Edvard Munch, but was significantly developed a few decades later through the German group Die Brücke ( The Bridge ). In Expressionism, the focus is not to represent the outward reality accurately, but the inward reality, feelings and emotions. Expressionist artists used vibrant colors and unusually thick brush strokes, and the resultant paintings were extremely dense and intense, conveying clear emotions and environments.

Particularly during the years following World War I , Expressionist paintings become particularly grotesque and dark. By focusing on emotions in the representation of reality, Expressionists could paint a more accurate and critical picture of society. In many ways, these paintings could show what photography could not, namely the artists’ feelings surrounding the reality represented.

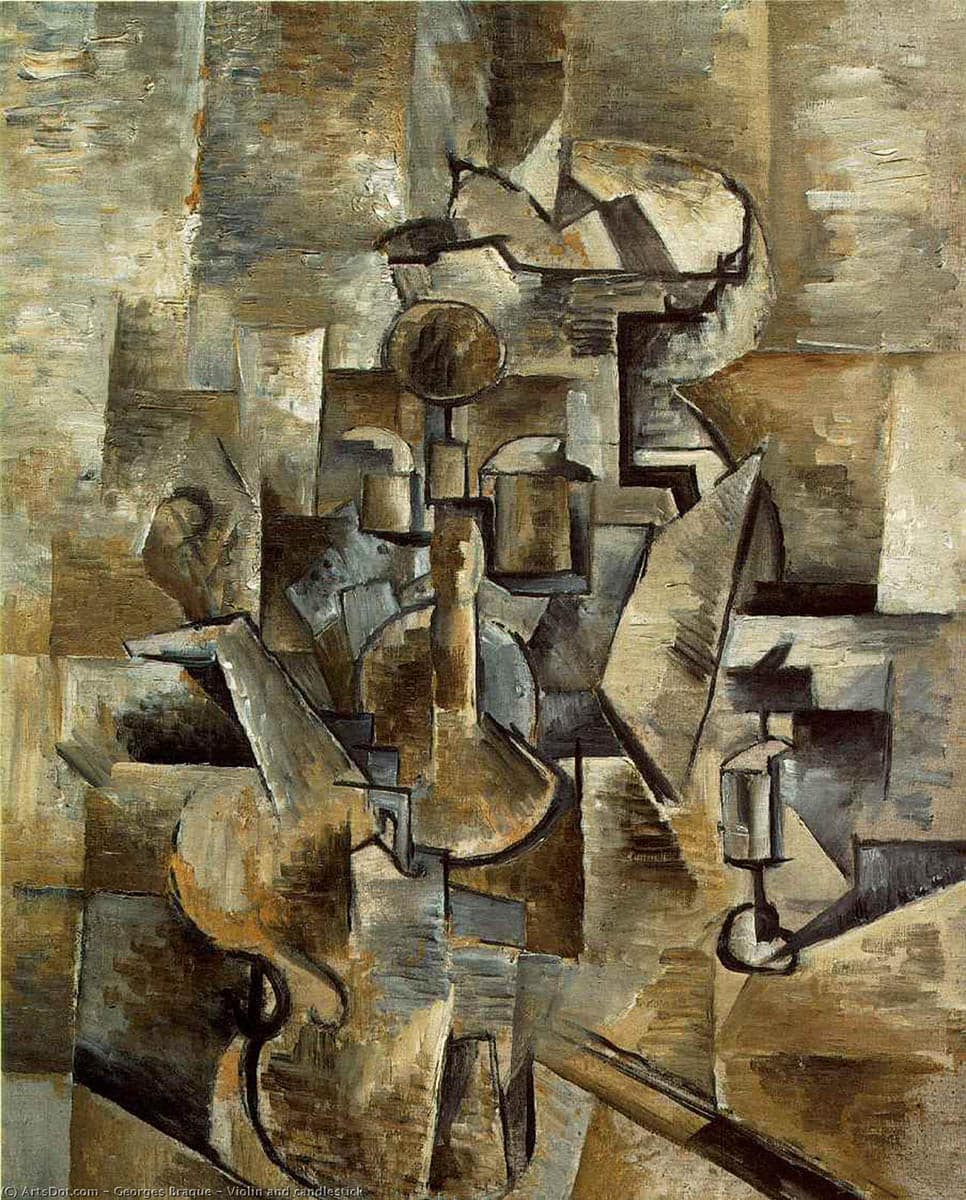

Probably one of the most famous movements within Modernism is Cubism . This movement revolutionized the concept of perspective and rejected the representation of three-dimensional objects. Instead of using typical modeling and perspective techniques, Cubists, such as Picasso or Braque, represented the objects as two-dimensional, often trying to include different perspectives of a single object at a time. By exploring perspective in such a way, Cubism, like other Modernist art movements, goes beyond what photography can do. Sometimes, the objects represented stray so far from reality that it is extremely difficult to understand what they are. Later, Cubism evolved to become more accessible and easier to understand, as seen on Picasso’s most famous paintings, such as Guernica .

Around 1920 began one of the most important movements within Modernism: Surrealism . Surrealists pick up where the Dadaists left off. Though fruitful in its first years, the Dadaist movement quickly lost itself in its own absurdism and was abandoned by many artists. Surrealism, despite enigmatic and absurd in its own way, is not at all devoid of meaning. Quite on the contrary, it attempts to demonstrate the overlapping of psychological processes in the human mind that cause dreams and imagination.

In Surrealist painting, it is not the physical reality that is represented, but the dream and unconscious reality. As in other Modernist art movements, Surrealism is complementary to photography because it represents something well beyond its reach: the human mind and the dream world. By breaking free of the shackles of reality, Surrealist painters portray our minds and dreams in a revolutionary way.

How Modernist Painting Influenced Photography

Despite not being created with artistic purposes in mind, photography was quickly explored by artists. First, photography was used as an aid for painting or other traditional art forms. Later, some artists began exploring the combination of photography, painting, and other mediums, thus creating new art forms, such as photomontage. One of the foremost artists in this new artistic medium was Hannah Höch , an artist of the Weimar Republic, who created famous examples of photomontage.

It took some time and controversy for photography to be considered a fine art form. Many critics, well into the 20th century, still refused to accept photography as anything more than an industrial mechanism that imitated reality but had little artistic value on its own. However, throughout the 20th century, photography began being recognized as an art form, and photographers created innovative ways to express themselves through it.

Modernism also significantly influenced photography and its alternative representations of reality and human emotion. During the 20th century, photographers also explored experimental and abstract photography . Despite still representing reality, these types of photography explore shapes, colors, and perspectives without striving to accurately represent a given scene or object.

How Photography Changed Our Perception of Art: An Overview

The 1837 invention of the Daguerreotype impacted society and the artistic world that Daguerre could not have foreseen. By surpassing painting in its ability to represent reality, photography, in a way, released painting from the need to be realistic. Photography also allowed for more widespread access to art and portraits, which were in high demand in 19th-century society.

Impressionism was the first movement to be shaped by photography and stray from the realism that was the norm in European art. This movement acted as a bridge between previous movements and Modernism. In the various artistic movements within Modernism, many artists explored countless new ways to express themselves. Artists began focusing on the human experience and different ways to perceive reality and created revolutionary works. Photography followed the tendency towards subjectivity and abstraction, which contributed to its recognition as an art form of its own.

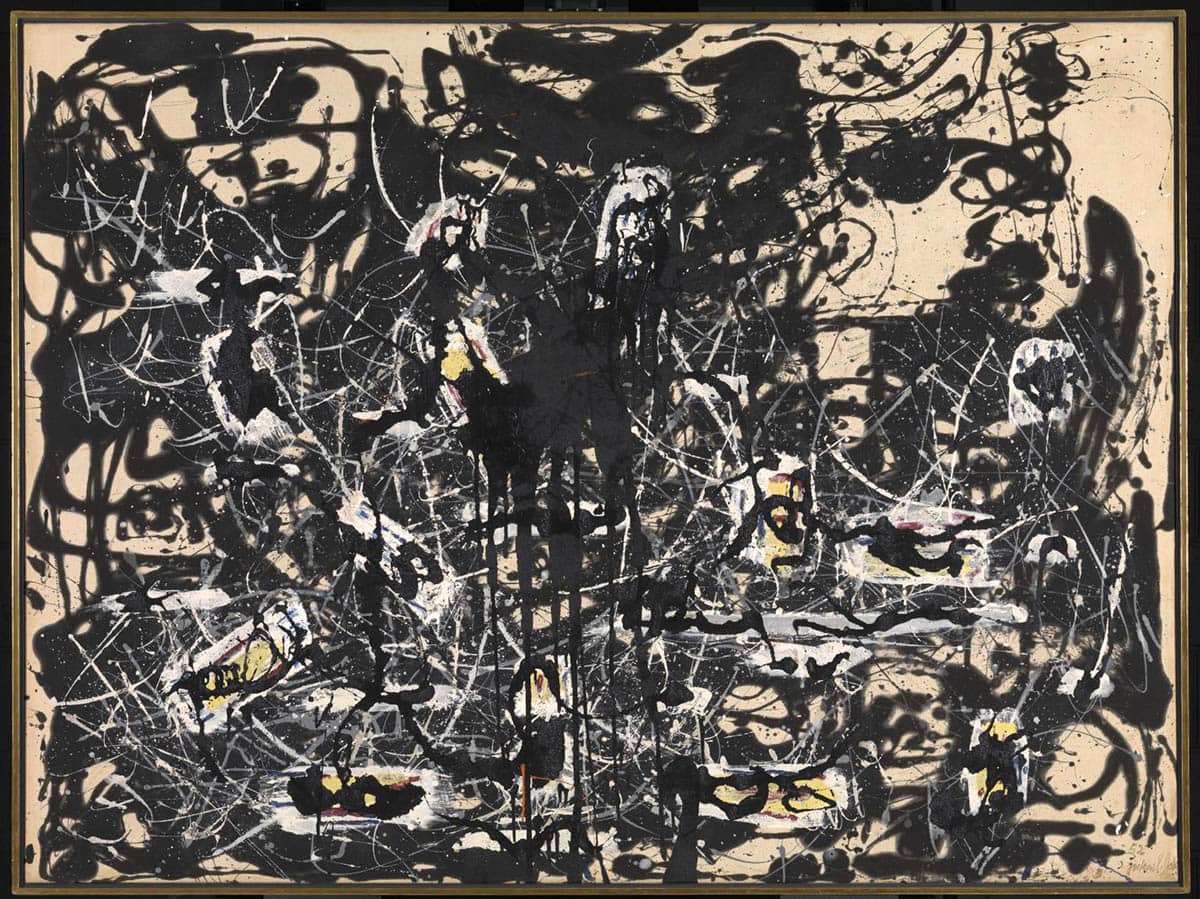

Nowadays, art is understood not only as a faithful representation of reality but as something which provokes thought and emotion. Many viewers are interested in the meanings and feelings an artwork conveys or represents or the social criticism it contains. Realism, although still valued by some, has lost its place as a priority within artistic circles and by artists themselves. This is especially clear when we think about art movements that have distanced themselves from reality, such as Abstract Expressionism .

4 Techniques of 19th-Century Photography You Should Know

By Eva Silva BA Languages, Literature and Culture Eva Silva has a BA in Languages, Literature and Culture from the University of Lisbon. Her research and work revolve around German history, culture, language, literature, and European culture in general.

Frequently Read Together

Want to Become a Great Photographer? Focus on These 5 Tips

Gustave Courbet: What Made Him The Father of Realism?

What is Spirit Photography: Fraud or Phenomenon?

When Photography Wasn’t Art

Today, photography is commonly accepted as a fine art. But through much of the 19th century, it was an art world outcast.

![essay about photography as art Pine forrest [sic], Summit Station, Catawissa R.R. Photo by John Moran](https://daily.jstor.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Pine-forrest-sic-Summit-Station-Catawissa-R.R..jpeg)

Today, photography is commonly accepted as a fine art. But through much of the 19th century, photography was not merely a second class citizen in the art world—it was an outcast.

Photography was invented in the 1820s and though it remained a fledgling technology in the few decades thereafter, many artists and art critics still saw it as a threat, as the artist Henrietta Clopath voiced in a 1901 issue of Brush and Pencil :

The fear has sometimes been expressed that photography would in time entirely supersede the art of painting. Some people seem to think that when the process of taking photographs in colors has been perfected and made common enough, the painter will have nothing more to do.

London’s Victoria & Albert Museum became the first museum to ever hold a photography exhibition in 1858, but it took museums in the United States a while to come around. The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston , one of the first American institutions to collect photographs, didn’t do so until 1924.

When critics weren’t wringing their hands about photography, they were deriding it. They saw photography merely as a thoughtless mechanism for replication, one that lacked, “that refined feeling and sentiment which animate the productions of a man of genius,” as one expressed in an 1855 issue of The Crayon . As long as “invention and feeling constitute essential qualities in a work of Art,” the writer argued, “Photography can never assume a higher rank than engraving.”

At best, critics viewed photography as a useful tool for painters to record scenes that they may later more artfully render with their brushes. “Much may be learned about drawing by reference to a good photograph, that even a man of quick natural perceptions would be slow to learn without such help,” wrote one in an 1865 issue of The New Path . But the writer’s appreciation ended there. Photography couldn’t qualify as an art in its own right, the explanation went, because it lacked “something beyond mere mechanism at the bottom of it.”

Some, like landscape photographer John Moran , however, fought back against this idea. “This refusal to rank Photography among the fine arts, I consider, is in a measure unfounded, its aim and end being one in common with art. It speaks the same language, and addresses itself to the same sentiments,” he wrote in a March 1865 issue of The Philadelphia Photographer. While he could not entirely escape the stigmas of his time—he declared photography could never “claim the homage of the higher forms of art” because “in the actual production of the work, the artist ceases and the laws of nature take his place”—he articulated an important argument for photography as a form of creative expression:

The exercises of the artistic faculties are undoubtedly necessary in the production of pictures from nature, for any given scene offers so many different points of view; but if there is not the perceiving mind to note and feel the relative degrees of importance in the various aspects which nature presents, nothing worthy the name of pictures can be produced. It is this knowledge, or art of seeing, which gives value and importance to the works of certain photographers over all others.

Moran’s central contention, that “there are hundreds who make, chemically, faultless photographs, but few make pictures” remains true today. Few are making photos with chemicals anymore, but billions make legible photographs with the click of a button. Still, as was the case 150 years ago, the art is in the eye, not the device.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

More Stories

The Development of Central American Film

Remembering Maud Lewis

Exploring the Yardbird Reader

But Why a Penguin?

Recent posts.

- Scaffolding a Research Project with JSTOR

- Making Implicit Racism

- The Diverse Shamanisms of South America

- Time in a Box

- K-cuisine in Malaysia: Are Locals Biting?

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Photography: is it art?

F or 180-years, people have been asking the question: is photography art? At an early meeting of the Photographic Society of London , established in 1853, one of the members complained that the new technique was "too literal to compete with works of art" because it was unable to "elevate the imagination". This conception of photography as a mechanical recording medium never fully died away. Even by the 1960s and 70s, art photography – the idea that photographs could capture more than just surface appearances – was, in the words of the photographer Jeff Wall , a "photo ghetto" of niche galleries, aficionados and publications.

But over the past few decades the question has been heard with ever decreasing frequency. When Andreas Gursky's photograph of a grey river Rhine under an equally colourless sky sold for a world record price of £2.7 million last year, the debate was effectively over. As if to give its own patrician signal of approval, the National Gallery is now holding its first major exhibition of photography, Seduced by Art: Photography Past and Present .

The show is not a survey but rather examines how photography's earliest practitioners looked to paintings when they were first exploring their technology's potential, and how their modern descendants are looking both to those photographic old masters and in turn to the old master paintings.

What paintings offered was a catalogue of transferable subjects, from portraits to nudes, still lifes to landscapes, that photographers could mimic and adapt. Because of the lengthy exposures necessary for early cameras, moving subjects were impossible to capture. The earliest known photograph of a person was taken inadvertently by Louis Daguerre – with Henry Fox Talbot one of photography's two great pioneers – when he set up his camera high above the Boulevard de Temple in Paris in 1838. His 10-minute exposure time meant that passing traffic and pedestrians moved too fast to register on the plate, but a boulevardier stood still long enough for both him and the bootblack who buffed his shoes to be captured for ever.

When Daguerre turned his camera on people rather than places the results were revelatory. Elizabeth Barrett Browning was so struck by Daguerreotypes that she rhapsodised over "the very shadow of the person lying there fixed forever". The fidelity of features captured meant that she "would rather have such a memorial of one I dearly loved, than the noblest Artist's work ever produced" not "in respect (or disrespect) of Art, but for Love's sake". If, however, her photographer followed the advice of Eugène Disdéri , who wrote in 1863 that: "It is in the works of the great masters that we must study the simple, yet grand, method of composing a portrait," she could satisfy love with both physiognomy and art.

What some pioneering photographers recognised straight away was that photographs, like paintings, are artificially constructed portrayals: they too had to be carefully composed, lit and produced. Julia Margaret Cameron made this explicit in her re-envisagings of renaissance pictures. Her Light and Love of 1865, for example, shows a woman in a Marian headcovering bending over her infant who is sleeping on a bed of straw. It is part of a line of nativity scenes that is as long as Christian art, and was hailed by one critic as the photographic equivalent of "the method of drawing employed by the great Italian masters". I Wait , 1872, shows a child with angel's wings resting its chin on folded arms and wearing the bored expression that brings to mind the underwhelmed cherubs in Raphael's Sistine Madonna . Such photographs were not direct quotations from paintings, but they raised in the viewer's mind a string of associations that gave photography a historical hinterland.

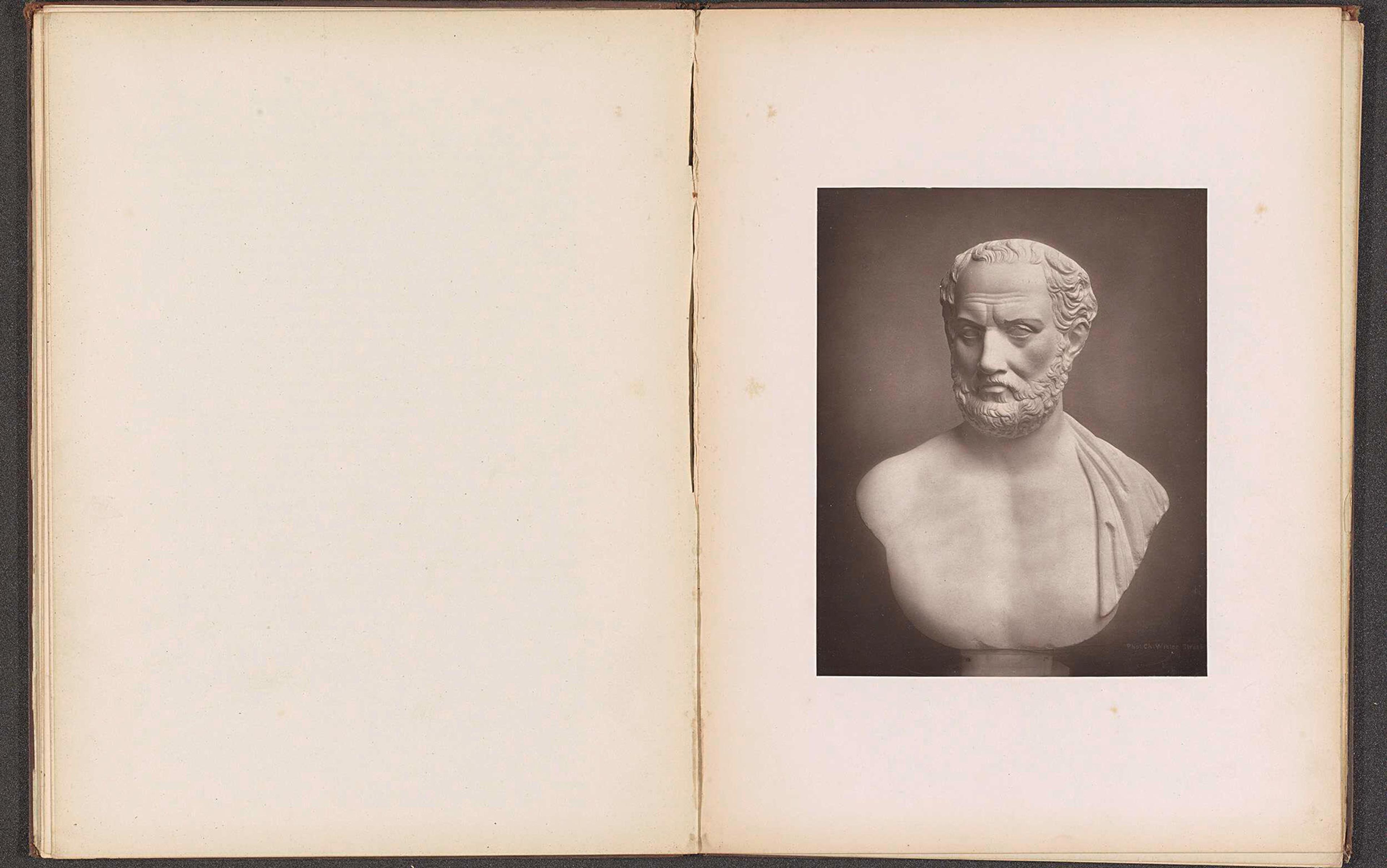

If Cameron and contemporaries such as Oscar Rejlander and Roger Fenton (who took numerous photographs of still-life compositions of fruit and flowers as well as his better known pictures of the Crimean war) were keen that their photographs should reflect their own knowledge of art, the links went both ways. In 1873, Leonida Caldesi published a book of her photographs of 320 paintings in the National Gallery, and her intended audience was not just the public but artists themselves, for whom the photographs were both more accurate and more affordable than engraved reproductions. By 1856, thanks to Fenton's photographs, artists could study classical statues in their own studios.

It was perhaps in depicting the nude – such as Fenton's bestselling photograph of the discus thrower Discobolus – that photography could repay its debt to art. Hiring a life model was expensive, and engravings were a poor substitute. Delacroix was one artist who "experienced a feeling of revulsion, almost disgust, for their incorrectness, their mannerisms, and their lack of naturalness". He praised instead the painterly aid provided by académies (books of nude photographs) since they showed him reality: "these photographs of the nude men – this human body, this admirable poem, from which I am learning to read". He even helped the photographer Eugène Durieu pose and light his models. And in 19th-century Britain and France, when pornography was illegal, photographs of the nude were in demand from customers who had no artistic interests.

When it came to landscape photography the new medium appeared just as the impressionists were beginning to work in the open air. Some commentators saw photography's real challenge to painting as lying in its ability to capture what the photographer and journalist William Stillman called in 1872 "the affidavits of nature to the facts on which art is based" – the random "natural combinations of scenery, exquisite gradation, and effects of sun and shade". Another practitioner, Lyndon Smith , went further, declaring landscape photography the answer to the "effete and exploded 'High Art', and 'Classic' systems of Sir Joshua Reynolds " and "the cold, heartless, infidel works of pagan Greece and Rome".

Being new was a laborious business, however. Eadweard Muybridge , the British-born photographer who first captured animals in motion and as a result ended the old painterly convention of showing horses running with all four legs off the ground, was primarily a landscape photographer. His pictures of the Yosemite wilderness , for example, involved carrying weighty cameras, boxes of glass negatives, as well as tents and chemicals for a makeshift darkroom, up mountains and through forests. Monet's painting expeditions by contrast required only paint and canvas.

If early photographers had no option but to negotiate their own engagement with painting their modern descendants can call on nearly two centuries of photographic history. It is a point the exhibition makes by combining old and new. So when a contemporary photographer such as Richard Billingham photographs an empty expanse of sea and sky in Rothko washes of slate blues and greys ( Storm at Sea ) he is referring to a heritage that encompasses both the monochrome tonality of Gustave Le Gray 's atmospheric photographic seascapes of the 1850s and a painting such as Steamer on Lake Geneva, Evening Effect , 1863, by the Swiss artist François Bocion .

The point is made across the different media. A brittle portrait of a suburban couple from Martin Parr's 1991 album Signs of the Times , for example, is contrasted with Gainsborough's Mr and Mrs Andrews of 1750 . Both are images of possession and entitlement, the latter displaying landowners at ease amid their fields and woods, comfortable with both themselves and their station, the former a couple posing stiffly in their sitting room.

Meanwhile a 19th-century flower painting by Henri Fantin-Latour is the starting point for Ori Gersht's fragmented blooms, Blow Up . Gersht froze his flowers with liquid nitrogen before exploding them with a small charge and photographing the petals turned to flying shards. Among the nudes, Richard Learoyd's Man with Octopus Tattoo , 2011 , is placed next to the gallery's 1819-39 painting of Angelica Saved by Ruggiero by that connoisseur of bodily curves, Ingres. The appeal of flesh and its sinuosity is timeless.

The curators of the National Gallery exhibition have avoided using many of contemporary photography's biggest names (there is no Andreas Gursky and no Cindy Sherman for example), and nor do they include photorealist painters such as Gerhard Richter or Andy Warhol . Their choices are largely less celebrated figures as if to show how deep is the seam of photographers still working with the long visual past. When in 1844-6 Fox Talbot published his thoughts about photography he gave the book (the first publication to contain photographic illustrations) the title The Pencil of Nature . This exhibition lays out what photography's founding father could never know: how the camera has also always been the pencil of art.

- Photography

- Andreas Gursky

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

Philosophy of Photography as an Art Essay

Many people claim that the word art cannot apply to contemporary artworks and photojournalism. When it comes to paintings or sculpture, it is argued that artists simply try to stand out from the rest of their peers or shock the public. Photography is regarded as a mere reflection of the reality that is created with the help of technology. This paper focuses on photography and its connection to art. It can be difficult to differentiate between photographs and pieces of art. However, Arthur Danto’s notion of interpretation as a key component of art can help in identifying artworks within the domain of photojournalism.

When considering the nature of contemporary art, Danto refers to Brillo Box by Andy Warhol (29). The art critic emphasizes that the depiction of Brillo boxes acquires an artistic value when the picture is characterized by hidden meanings and interpretations. Therefore, in order to identify a masterpiece among mere depictions, it is necessary to focus on meanings and interpretations (Danto 55). In simple terms, a photograph of a pile of boxes becomes an artwork if the viewer sees the idea behind the object. For instance, the photographer can reflect on such issues as consumerism or environmental responsibility. Importantly, although photographs can be easily reproduced, they can still be regarded as works of art as the photographer managed to capture the meaning.

In conclusion, it is necessary to stress that photography is a specific form of art that involves the use of technology. Danto’s view on artistic value helps in understanding photojournalism. Meaning and interpretation are elements of art. Hence, photographs that have hidden or explicit meanings are works of art. When people take pictures to capture memories, they use technology to reflect reality. When photographers capture meanings in the reflection of life, they create pieces of art.

Danto, Arthur C. What Art Is . Yale University Press, 2014.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, June 25). Philosophy of Photography as an Art. https://ivypanda.com/essays/philosophy-of-photography-as-an-art/

"Philosophy of Photography as an Art." IvyPanda , 25 June 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/philosophy-of-photography-as-an-art/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Philosophy of Photography as an Art'. 25 June.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Philosophy of Photography as an Art." June 25, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/philosophy-of-photography-as-an-art/.

1. IvyPanda . "Philosophy of Photography as an Art." June 25, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/philosophy-of-photography-as-an-art/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Philosophy of Photography as an Art." June 25, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/philosophy-of-photography-as-an-art/.

- “The Supermodel and the Brillo Box” by Don Thompson

- “Beauty and politics” Arthur Danto

- Aesthetic of Beauty - Views of Danto and Tolstoy

- Reading Response: Arthur Danto

- Andy Warhol’s Pop Art and Mass Production

- Aesthetics Art: Theory and Philosophy

- Knowing Andy Warhol’s Life and Photography

- Ethical Principles in Photojournalism

- The Issue of Ethics in Photojournalism

- Andy Warhol's Biography

- Robinson, Emerson, and Photography as an Art

- “The Valley of the Shadow of Death” the Photography by Roger Fenton

- Photography Changes Who We Think We Might Be

- A Distinct Camera Vision in Jacques-Henri Lartigue’s Photograph

- Alfred Stieglitz’s Photo Analysis

This site requires Javascript to be turned on. Please enable Javascript and reload the page.

Is Photography Among the Fine Arts?

By: Zofia Mowle Fine art is a form of visual art, intended to be appreciated entirely for its imaginative and visionary content. Photography has developed throughout the course of many years, and there has definitely been a shift in the way we appreciate it as an art form. The field of photography has expanded significantly and in today’s society anything that has artistic intent behind it, whether that be abstract, portrait or landscape photography, will be considered fine art. The discussion of whether or not photography should be considered a ‘fine art’ is a topic that has been debated for hundreds of years. There are such strong arguments for both sides, and it’s important to recognise all these factors when forming an opinion.

Joseph Pennell is an American illustrator and author, who spent the majority of his life studying the traditional means of architectural drawings in Europe. During his time abroad he established an international reputation for himself as someone of high regard within the fine art world. Joseph Pennell had an extreme bias and unfavourable opinion towards photography. In 1897, Pennell wrote an excerpt titled ‘Is Photography Among the Fine Arts?’ In this excerpt he provided an array of reasons as to why photography is not among the fine arts. There’s a strong bias against photography, which is supported within the text. Pennell discusses the lack of skill required with photography, as it’s “merely mechanical and [does] not require the [same level of] training that art does.” [1] To continue, Pennell argued that photography shouldn’t be considered a fine art as it’s too easy. He compared photography to a simple hobby, saying that, “photography is amusement and relaxation.” [2] Traditional painting and photography are two completely different forms of art. Therefore, it’s difficult to truly compare them when debating the topic of what makes something ‘fine art.’ Throughout the reading he continually expresses his belief that artists are more qualified and trained than photographers, and therefore are superior. He judges photographers and ridicules them, saying what a farce it is that “Titian, Velasquex and Rembrandt actually [studied].” [3] The art of photography is to capture our surroundings with a realistic approach. Unlike with paintings, cameras have the ability to see everything and capture specific moments of time, which may go unnoticed within our everyday lives. They are essentially machines that have the capability to produce a documentary fact. Similarly to how there are machines to create carpets and machines to produce shirts, the camera is a machine that was invented to generate pictures. For this reason, Pennell questions why photography is considered an art form at all. If photography is such an automated process dependent on machinery and chemicals, then why is it art? “The man who sells margarine for butter, and chalk and water for milk, does much the same, and renders himself liable to legal prosecution by doing it.” [4] It’s clear from Joseph Pennell’s excerpt that photography is not a form of ‘fine art.’ Fine art usually involves a story and is intended to have a purpose that evokes some sort of emotion from the viewer. I agree with Pennell that it’s not possible just to take a beautifully composed picture and call it fine art. In order for an image to be considered fine art it must be designed with the intention of resonating with the viewer and compel the audience to perceive the subject matter differently.

In contradiction to Joseph Pennell’s excerpt, Paul L. Anderson wrote a book titled ‘The Fine Art of Photography.” This book was interesting as the author went against everything previously mentioned and he discussed the array of reasons as to why photography should be considered among the fine arts. Paul L. Anderson was an American photographer and author, who wrote many books on the art of photography. Anderson considers photography a unique form of graphic art. In his book he conveys the importance of photography as an art form, and how it’s a collaborative process where “scientific knowledge and artistic feeling go hand-in-hand to the production of a fine result.” [5] He defines fine art as “any medium of expression which permits one person to convey to another an abstract idea of lofty character, to arouse in another a lofty emotion.” [6] Anderson highlights an important factor that must be established, which is to draw the line between fine art and craftsmanship. He uses Michelangelo’s David as a clear example of something that is considered fine art, whereas a typical Indian man’s tobacconist sign as something that is not. However, it’s not possible to say just where these two expressions merge. Anderson argues that, “the Indian may carry a glimmering of an abstract, and to that extent may possess some of the elements of fine art.” [7] The question of whether or not photography is among the fine arts varies significantly from person to person. Anderson believes that for photography to be considered a true art form, and not a craft, the photographer must create an image with a specific vision. The artist must use the camera as a medium for creative expression with a goal of creating something that expresses an idea, message and emotion.

E. Thiesson created a Daguerreotype titled Native Woman of Sofala, 1845. In my opinion, this photograph is an exquisite example of fine art. It’s a profile portrait of an African woman seated on a wooden chair. The composition is well-balanced and the figure is situated in the center of the frame. It’s a raw and organic image that provokes a multitude of emotion within the viewer. Her expression resembles something of contemplation -she appears to be deep in thought and it forces us, as the viewer, to ask questions. Her posture is slouched, she does not wear any makeup, her hair is natural and she wears a kaba skirt, which is a traditional African skirt made from kiswah. Her breasts are left uncovered, but not in a sexualised way. She’s a traditional African woman and her appearance represents her culture. One of the essential purposes of photography is communication. This image communicates heritage, it teaches us about ethnicities and cultures that differ from our own. We use photography as a form of documentation and it’s used for educational purposes. Pennell would argue that this photograph isn’t an example of fine art, as it’s simply just a woman sitting on a chair. In his reading he makes direct comparisons between photography and painting, emphasising that one is significantly more impressive than the other. What’s better, a nude photograph or a nude painting? Pennell believes that getting a model to pose naked for a photograph puts other artists like Botticelli to shame, for he “sees what he has been taught to like by reading books on painting; which he does not understand and which teaches nothing for him.” [8] Despite this, in my opinion, Thiesson’s photograph is a true example of fine art photography. It’s evident that the artist took the time to carefully create the composition, from the framing of the image to the details of the woman -her attire, posture, expression, etc. Dona Schwartz, an author and professor of journalism, wrote an article on the social construct of photography. In her article she argues that photography draws upon “ethnographic research comparing the activities of the camera club and fine art photography.” [9] This comparison translates to Thiesson’s photograph, as it’s a collaboration between ethnographic photography and fine art.

It’s interesting to debate the topic of what is and what isn’t considered to be ‘fine art.’ To this day, photographs remain to have less monetary value than paintings and sculpture. In my opinion, both mediums fulfil different tasks -a photographer captures a single moment, a snapshot of life, and a painter makes a picture. Paintings have the ability to illustrate deeper meanings that photographers are either unable to, or struggle to, encapsulate within their work. However, in my opinion, this doesn’t take away from what is considered ‘fine art.’ I believe that photography is among the fine arts, as fine art photography requires a similar level of precision and specific vision that other fine art mediums, such as painting and sculpture, require. Fine art photographs are created just as carefully as paintings, and therefore it’s unjust to classify photography, as a whole, as a medium that is unworthy being considered fine art.

This page has paths:

This page references:.

- 1 2021-03-15T19:42:58+00:00 [6] 1 plain 2021-03-15T19:42:58+00:00

- 1 2021-03-15T19:43:27+00:00 [7] 1 plain 2021-03-15T19:43:27+00:00

- 1 2021-03-15T19:44:14+00:00 [8] 1 plain 2021-03-15T19:44:14+00:00

- 1 2021-03-15T19:44:49+00:00 [9] 1 plain 2021-03-15T19:44:49+00:00

- 1 media/Joseph_Pennell_thumb.jpg 2021-02-22T20:09:03+00:00 Joseph Pennell 1 media/Joseph_Pennell.jpg plain 2021-02-22T20:09:03+00:00

- 1 media/unnamed_thumb.jpg 2021-02-22T20:10:10+00:00 Native Woman of Sofala 1 E. Thiesson media/unnamed.jpg plain 2021-02-22T20:10:10+00:00

- 1 2021-03-15T19:38:12+00:00 [1] 1 plain 2021-03-15T19:38:12+00:00

- 1 2021-03-15T19:39:33+00:00 [2] 1 plain 2021-03-15T19:39:33+00:00

- 1 2021-03-15T19:40:11+00:00 [3] 1 plain 2021-03-15T19:40:11+00:00

- 1 2021-03-15T19:40:51+00:00 [4] 1 plain 2021-03-15T19:40:51+00:00

- 1 2021-03-15T19:42:23+00:00 [5] 1 plain 2021-03-15T19:42:23+00:00

- Cinematography

Is Photography Art? — Both Sides of the Debate Explained

I s photography art? This question has been debated since the creation of the first camera, and is still sometimes contested to this day. The answer may seem obvious to those working within the photographic medium, but there is some dissent, even within the artistic community. We will be playing devil’s advocate and taking a look at both sides of the is photography art debate.

Photography definition in art

Defining art.

Before we can answer is photography art? We need to make sure we have a rock-solid definition of “art.” Art means different things to different people, so for the purposes of total clarity, we’ll be going by the dictionary definition.

For any other unclear terms, our ultimate guide to film terminology is a great resource for looking things up.

PHOTOGRAPHY DEFINITION IN ART

What is art.

The Merriam Webster dictionary defines art as: “the conscious use of skill and creative imagination especially in the production of aesthetic objects.” The dictionary also defines a work of art as something that is “produced as an artistic effort or for decorative purposes.”

So, is photography art? Based on this definition, it seems pretty clear that photography is considered a visual art. The umbrella of art is far reaching and can encompass any skillful creative endeavor. Despite the inherent artistic value in still photography, there are still plenty of individuals who would argue that photography is not an artistic pursuit. Let’s elucidate their point of view.

Does photography count as art?

Debunking why photography is not art.

Those on the opposing side in the is photography art debate rely on a few different arguments to make their case. One common stance against photography as art is that photography captures reality rather than creating a subjective reality, which is what “real art” does.

Why photography is not art stance: it merely captures reality

Taking this into consideration, does photography count as art? If so, what type of art is photography? It is easy to debunk the stance that derides photography as an art form.

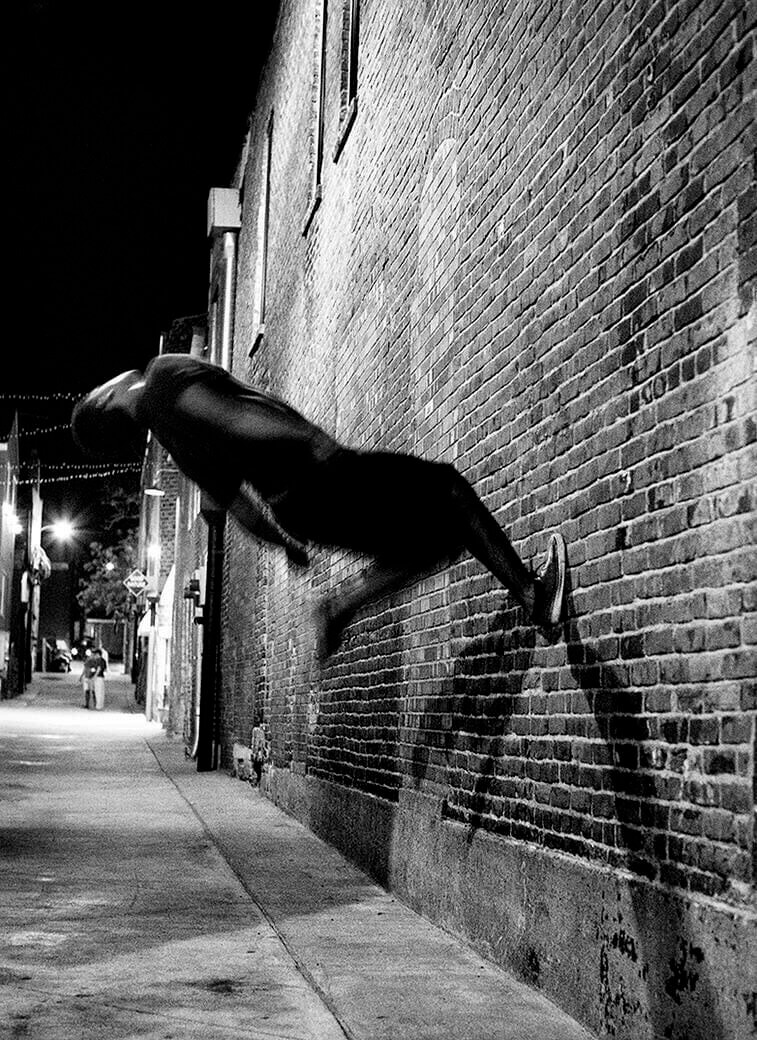

The idea that photography cannot do any more than capture a moment of real life is quite reductive to the entirety of what makes photography art.

You needn’t look far to find examples of aesthetic photographs that push the bounds of objective reality.

A clear-cut example of photography as an artform

It is easy to view the photographer as artist when taking all of the creative photography choices they make into consideration: subject, lighting techniques , camera framing , lens choice , symbolism , technical settings, post-processing, and many more decisions are what makes photography art.

What type of art is photography? In this case, surrealism

This same argument that opposes the classification of the photographer as artist because they capture reality also suggests that there is no artistic merit in capturing a moment in time that shows real life plainly. Believing this argument suggests that the work of street photographers is non-artistic.

What is photography in art? The answer may be subjective

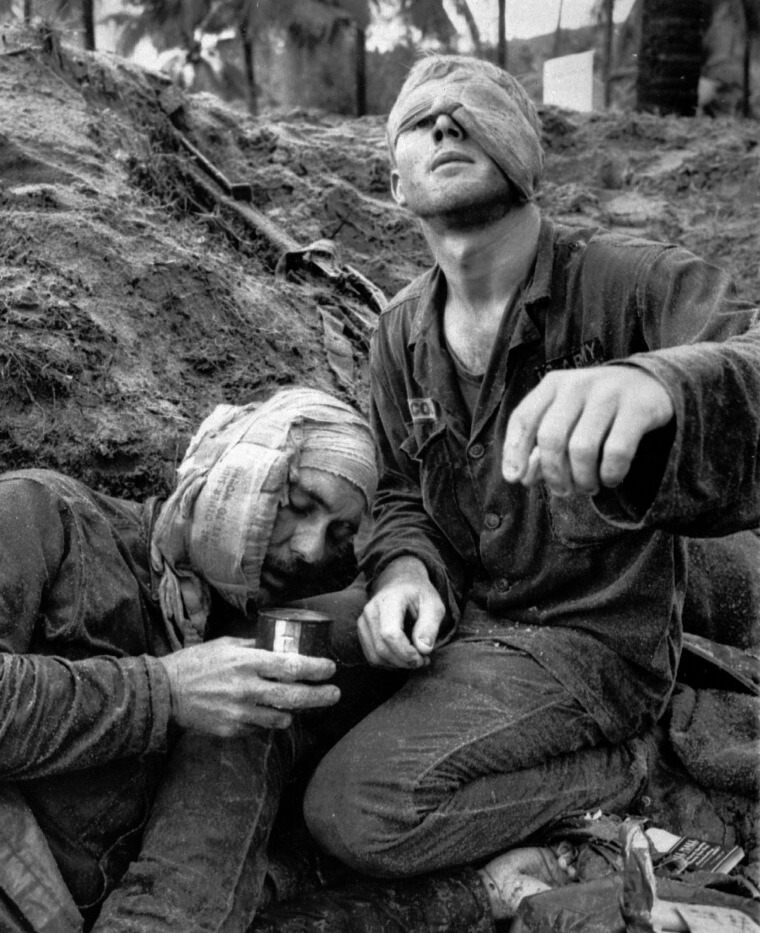

In the debate over is photography a form of art , suggesting that capturing reality is not artistic devalues the important photographic work done by the likes of war journalists, which is not a favorable stance to hold when taking historical context into account.

What is fine art photography if not candid images showcasing the horrors of war

The importance of war photographers, sports photographers , and other photojournalists can not be understated.

Is photography a fine art? This powerful photo from the Vietnam war says yes

Let’s dig deeper into what made photography an art form initially.

Photography as an Art Form

What made photography an art form.

Is photography art or science? When the first camera was invented , the question: is photography a fine art? was certainly more open to debate. The development of photography as an art form happened quickly. The practice of photography began rooted in science and experimentation but it wasn’t long for photography to be considered a visual art.

A case could be made for science in the question: is photography art or science? But, what made photography an art form in the first place was the application of science in the creation of art. What type of art is photography? The answers are as limitless as with any other medium. Just as a painter uses paint, a brush, and a canvas, the photography uses a camera and film as their tools.

What is photography in art?

Is photography art — arguments against.

Is photography art? Another time-tested argument against an affirmative answer has to do with replication. This argument posits that since photographs can be replicated infinitely, their artistic value is inherently lower than a traditional work of art, such as a painting, that was made by hand and exists as a one-of-a-kind piece.

Copies and prints can be made of a painting, but the original painting remains a singular work of art elevated above all subsequent copies.

What is fine art photography

Some detractors answer the question is photography a form of art on a conditional basis. There are people who assert that a still photograph is never art, while there are others who assert that photography is considered art under the right circumstances, but that not every photograph taken is automatically considered a work of art.

Acclaimed visual artist Roger Ballen holds a complicated view on is photography art? He believes there is an important distinction between a photographer and an artist who uses photography as their medium.

What is photography in art? Roger Ballen answers

Now that we’ve heard from those who don’t believe photography is art, at least not in all instances, let’s hear from the other point of view.

Related Posts

- What is Double Exposure? →

- What is Overexposure in Photography? →

- Types of Camera Lenses for film and photography →

Is photography art?

The case in favor of photography as art.

It is plain to see that a carefully composed , exposed , focused , and captured image has inherent artistic value. Photography, as a medium, can shade reality with new context and meaning. Messages and symbolism can be conveyed through the presentation of a still image.

The juxtaposition of visual elements can take on new value when frozen in time as a photograph. All of the near-infinite photographic variables and possibilities make it clear that photography is artistic

This TED Talk examines photography as a form of creative self-expression.

TED Talk by Flore Zoe

The manipulation of different camera types as tools, and of the visual subject as a canvas make for endless photographic potential. The first cameras in history maybe have been used more for the purposes of documentation rather than art, but it was not long before the artistic potential of the camera was first explored. Drawing, painting, and sculpting existed as art forms for thousands of years before the invention of the camera.

Whenever a new art form comes into existence, there is a hesitancy from the industry’s gatekeepers to recognize the new with the same reverence as the old .

Over time, barriers to artistic acceptance have been eroded and the pretentious protection of “traditional art” has lessened. These days, the general consensus is that photography is, in fact, an art form. For tips on taking artistic photographs, check out the video below.

How to Take Artistic Photographs

More So than with photography, a debate continues as to whether or not filmmaking is artistic. Any passionate filmmaker or cinephile will tell you, “Yes! Of course filmmaking is art!” But there are individuals who do not share that point of view. If you believe that filmmaking and photography are art forms, then we have numerous articles that can help further your understanding and appreciation of these creative mediums.

Cameras for Photography and Video

Is photography considered an art form? Absolutely. The most important piece of technology when working as a photographer or a videographer is the camera. There are many different types and models of cameras on the market these days. Telling them apart and, more importantly, knowing which one to choose for your own projects can be a challenge. Our camera guide can bring you up to speed on the different types of cameras available to you.

Up Next: Types of cameras →

Showcase your vision with elegant shot lists and storyboards..

Create robust and customizable shot lists. Upload images to make storyboards and slideshows.

Learn More ➜

- Pricing & Plans

- Product Updates

- Featured On

- StudioBinder Partners

- The Ultimate Guide to Call Sheets (with FREE Call Sheet Template)

- How to Break Down a Script (with FREE Script Breakdown Sheet)

- The Only Shot List Template You Need — with Free Download

- Managing Your Film Budget Cashflow & PO Log (Free Template)

- A Better Film Crew List Template Booking Sheet

- Best Storyboard Softwares (with free Storyboard Templates)

- Movie Magic Scheduling

- Gorilla Software

- Storyboard That

A visual medium requires visual methods. Master the art of visual storytelling with our FREE video series on directing and filmmaking techniques.

We’re in a golden age of TV writing and development. More and more people are flocking to the small screen to find daily entertainment. So how can you break put from the pack and get your idea onto the small screen? We’re here to help.

- Making It: From Pre-Production to Screen

- What is a Freeze Frame — The Best Examples & Why They Work

- TV Script Format 101 — Examples of How to Format a TV Script

- Best Free Musical Movie Scripts Online (with PDF Downloads)

- What is Tragedy — Definition, Examples & Types Explained

- What are the 12 Principles of Animation — Ultimate Guide

- 70 Facebook

- 0 Pinterest

University of Notre Dame

Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews

- Home ›

- Reviews ›

Photography and Philosophy: Essays on the Pencil of Nature

Scott Walden (ed.), Photography and Philosophy: Essays on the Pencil of Nature , Blackwell Publishing, 2008, 325pp., $79.95 (hbk), ISBN 9781405139243.

Reviewed by John Andrew Fisher, University of Colorado at Boulder

Shows devoted to photography seem to be everywhere in the art world. As Scott Walden, the editor of this collection of essays notes, photography "has become the darling of the avant-garde." It appears that photography has become trendier than painting. One reason for this may be that while the nature and scope of painting has been thoroughly investigated over the last two centuries, photography appears to be relatively unexplored. Moreover, as a medium photography has the advantage over both painting and sculpture of permeating social life and thus of appearing to be easier to understand in an art-world setting than other art forms. In addition, the variety of uses of photography in everyday life -- portraits, snapshots, fashion and advertising photographs -- provide artists with a multitude of genres to explore and often parody.

Perhaps surprisingly then, only a few of the thirteen essays that make up this collection directly address the artistic or conceptual content of current art photography. This is not to say that the collection is in any way disappointing. On the contrary, it is a ground-breaking, cutting-edge anthology of essays by leading analytic philosophers of art all focused in one way or another on the foundations of photography. In his contribution to the collection, Walden elaborates on his focus on truth in images with an explanation that could also serve as a rationale for the entire collection:

the operative assumption here is that the best methodology for understanding our appreciation of pictures involves first developing an understanding of their most literal aspects, and then proceeding to an understanding of the more complex aspects in terms of these relatively simple ones… . The faith is that if we can understand truth in relation to the depiction of the simple, visible properties of people and objects depicted, we can then, in terms of these and some other -- as yet undetermined -- principles governing the viewing of pictures, arrive at a more comprehensive understanding of the use of images in journalism, advertising, illustration, and art. (p. 94)

This faith might seem debatable, but in fact these essays do indirectly illuminate photography as art even when that is not their primary goal. By undermining the complacency with which we approach a mass art medium, they indirectly address the central aesthetic question that arises in looking at art photography: "In what ways can I appreciate a photograph aesthetically?"

Why does photography merit extended philosophical examination? Few other art media have troubled art theorists as much as photography, and this has been true since its inception in the nineteenth-century. Only instrumental classical music has fascinated philosophers as much. In pure instrumental music there is no intrinsic representational content, yet the music feels as if it is saying something and sounds as if it expresses emotions. In the case of photography we have the opposite problem: instead of too little representation, we have nothing but pure representation; we see nothing in a photograph but the objects that are photographed.

There are four fundamental issues that underlie the more specific themes of these essays: (i) What is the nature of photography? (ii) Given this nature, can photographs as photographs be fine art? (iii) How does photographic representation differ from other types of visual representation? and (iv) In what way are photographs more realistic, objective or true than representations produced in more traditional media?

Most of the papers were written especially for this anthology, although three chapters are reprints of papers by prominent figures in analytic aesthetics (Kendall Walton, Roger Scruton, Arthur Danto). Two of these papers, Walton's "Transparent Pictures: On the Nature of Photographic Realism," and Scruton's "Photography and Representation," are classics and serve to anchor the anthology by providing influential albeit controversial accounts of the foundations of photography. Walton argues that photographs are 'transparent,' by which he means that in looking at photographs we "quite literally" see their subjects. Scruton argues that a photograph cannot be what he calls a "representation," and by this he intends to imply that it cannot qua photograph be a work of art. To make their arguments, these two thinkers develop extended analyses of concepts central to photographs: in Walton's case, the concepts of seeing and visual experience, and in Scruton's case, the concept of an artistic representation. In relating photography to more general concepts, these papers join several others in the anthology. For example, Danto argues that individuals have rights over the way they appear, a meditation spawned by what he regards as untruthful photographic portraits.

Although the anthology is not divided into sections, one can collect most of the articles into three main groupings. The first group consists of five articles, all directed at analyses of the realism, objectivity, and truth that we attach to photographs: Walton on the transparency of photography, Cynthia Freeland on icons, Aaron Meskin and Jonathan Cohen on evidence, Walden on truth and Barbara Savedoff on authority. Danto's contribution, "The Naked Truth," also explores the specific sort of truth that might be ascribed to photographic portraits. He proposes a distinction between the optical truth that a high-speed photograph, which he calls a 'still,' might reveal and the natural way we see people or things. He argues that the "still … shows the world as we are not able to perceive it visually. It shows us the world from the perspective of stopped time" (300). Such photos often lie as portraits, Danto thinks, and when they do, they violate the personhood of the subject by failing to respect the image the subject desires to project to the community.

In "Transparent Pictures" Walton aims to understand the sort of realism possessed by photographs. He notes that photographs are not necessarily more accurate than paintings, yet he supports the idea that photography is "a supremely realistic medium" (21)). There is a gap, in his view, between the realism and immediacy of photography and what can be achieved by painting. He rejects the idea that in looking at a photograph we are having an illusion, as if we are mistaking the photograph for the objects photographed. His big claim is rather that photography "gave us a new way of seeing" (21). He means this quite literally: "Nor is my point that what we see -- photographs -- are duplicates or doubles or reproductions of objects … My claim is that we see , quite literally, our dead relatives themselves when we look at photographs of them" (22). He argues for this in several ways. One is a slippery slope argument, moving from seeing objects by means of mirrors, telescopes, etc. to seeing objects via live broadcast television, to seeing objects in documentary film. Although this implies seeing the past, he thinks we accept that we see events that occurred millions of years ago through a telescope. He does allow that we see photographed objects indirectly . Nor does he claim that we fail to see the photographs themselves. We see the objects -- our dead relatives -- by seeing the photograph; "one hears both a bell and the sound that it makes" (24).

Don't we also say that we 'see' Lincoln in a painting? Walton argues that this is fictional seeing, and this is because the sort of seeing involved applies equally to non-existent painted objects. Walton's theory of photography and of the way it differs from painting is based on the mechanical process of forming images which characterizes photography. Whether through an optical-and-chemical or digital process, once the shutter is triggered the image is determined by what is in front of the lens, not by the beliefs of the photographer:

The essential difference between paintings and photographs is the difference in the manner in which in which they … are based on beliefs of their makers. Photographs are counterfactually dependent on the photographic scene even if the beliefs (and other intentional attitudes) of the photographer are fixed. Paintings which have a counterfactual dependence on the scene portrayed lose it when the beliefs (and other intentional attitudes) of the painter are fixed. (38)

If a painter who is trying to depict the scene in front of her believes that there is a gorilla in the scene, she will put it in the painting even if it is not actually there, whereas even if a photographer also has that belief, a gorilla will not appear in the image if one does not exist in front of the camera.

The transparency of photographs is not about how photographs look, but about how we take them to imply that the objects we see in them existed. This explains, he suggests, why we experience a sort of shock when we learn that a Chuck Close photo-realist self-portrait is not a photograph: "We feel somehow less 'in contact with' Close when we learn that the portrayal of him is not photographic" (27). By contrast, "[v]iewers of photographs are in perceptual contact with the world" (48). This is not to deny that photographs, like some mirrors, can distort, nor that some photographs are constructions (combinations) that taken as a whole are not transparent.

Walton even allows that a "photograph, no less than a painting, has a subjective point of view" (35). Still, his account raises the question of whether the causal process that announces the existence of the objects photographed is the only defining characteristic of photography. Doesn't the photograph also show how these things appeared? Do we not only see our dead relatives, but also that the scene appeared a certain way ? Yet that appearance is the result of adjustments of many variables by the photographer. Although Walton says, "[p]hotography can be an enormously expressive medium," (35), it is not obvious how his account of the literal seeing involved in seeing a photograph addresses the subjective and expressive aspects of photographs. In literally seeing the objects in a photograph do we also literally see what they looked like? We think we do, but is there a basis for this thought in the transparency of photography?

The four papers that follow Walton's all grapple with photography's realism or truth. Freeland's "Photographs and Icons" points out that there are two senses of "realism," an epistemological sense related to truth and accuracy, and a psychological sense related to psychological force. She usefully employs terminology of Patrick Maynard's to mark this distinction as the difference between the "depictive" function of a picture and its "manifestation" function, which is similar to Walton's notion that we 'contact' the objects we see in the photograph. By describing an impressive parallel between photographs and religious icons, she presses the argument that photographic realism as the manifestation of the objects photographed has less to do with our beliefs in the epistemic status of photography than it does with our attitudes and emotions, such as the desire to sustain contact with departed people. In so far as her argument centers on portraits, whether of saints in icons or of people in photographs, it would be interesting to ask if it implies that we do not feel in contact with the non-human objects in, say, landscape photographs.

In "Photographs and Evidence," Meskin and Cohen approach realism from a different angle. They reject Walton's claim that we literally see the objects in photographs. Instead, they analyze the special epistemic status of (depictive) photographs in terms of their information content: "photographs typically provide information about many of the visually detectable properties of the objects they depict" (72). They follow Dretske in understanding that "information is carried when there is an objective, probabilistic, counterfactually supporting link between two independent events" (72). Because it is an objective link, their notion of the information carried by a photograph is independent of any subject's beliefs or other mental states. Their claim about photographic information is weaker than it might at first appear to be. Consider color: "photographs typically carry information about the color of the objects they depict -- if the colors of the objects had been different then the photographic image would have been different" (73). This concedes that the photograph does not tell the viewer what the color is ; as they note, "systematically replacing the colors of a picture with their complements would not thereby change the informational content of that picture" (74). They contrast visual or v-information about the appearance of objects with information about the egocentric location of the objects they depict, which they call e-information. In their view, the special epistemic status of photography is grounded on the fact that photographs provide v-information without providing e-information, whereas ordinary seeing provides both sorts of information.

Walden's "Truth in Photography," looks at photographs as potential sources of true beliefs. He contrasts objectively formed images -- those produced mechanically, such as photographs -- with subjectively formed images, such as handmade images. He argues that "we generally have better reason to accept beliefs engendered by viewing photographic images than we do those engendered by viewing handmade ones" (104). He concludes by considering whether the wide-spread adoption of digital-imaging techniques will undermine our confidence in the objectivity (mechanical nature) of the image-forming process. He argues that it is in "our collective interests to resist the implementation of such techniques [that undermine objectivity]" (109). One reason is that even if we still form true beliefs from looking at an image, these will be less epistemically valuable if we lack grounds for confidence in their truth.

Savedoff's contribution explores what she calls the documentary authority that we ascribe to photography: we regard a photograph as capturing a bit of the actual world. She makes this key to the ways that art photographs work; whether recognizably depictive or more abstract, they depend on and play off of this authority. The effectiveness of many artistic photos depend on our taking them as factual. She shows how the irony or humor of a photograph is made more profound because we regard the scene depicted as really in the world, not constructed by the photographer. She goes on to show how artistic photographs, because of their authority as photographs, often force the viewer to disambiguate complex images and thus see the world made strange. This authority also accounts for an important distinction between abstract paintings and abstract photographs. In the latter we are enticed to play a game of identifying the actual objects photographed. In a Cubist painting "the forms refer to objects … In the case of photographs, the forms are the forms of the objects before the lens" (122).

A second group of articles revolves around Roger Scruton's position. In "Photography and Representation" Scruton couples many of the same basic facts about photography that other authors accept with his own not implausible view of what an artistic representation of the world is to conclude that photographs as such can never be artistic representations: "photography is not a representational art" (139). It should be said that he is referring to a logically ideal photography, which he defines as having a purely causal and non-intentional relation to its subject. An ideal photograph of x implies that x exists and that it is, roughly, as it appears in the photograph. Yes, there is an intentional act involved in taking the photo, but it is not an essential part of the photographic relation. The appearance of the subject, therefore, is "not interesting as the realization of an intention but rather as a record of how an actual object looked" (140). Appearances in a representational painting are a different story. "The aim of painting is to give insight, and the creation of an appearance is important mainly as the expression of thought" (148). Given how they are defined, ideal photographs cannot express thoughts. He argues that "if one finds a photograph beautiful, it is because one finds something beautiful in its subject" (152). On the other hand, in so far as the photographer manipulates the image in some way, going beyond the 'ideal' photographic process, for example in a photo-montage, she becomes a painter. So, Scruton in effect presents a dilemma for anyone who would defend the possibility of photographs as art: either a given photograph is an 'ideal' photograph and hence not an artistic representation or it is in important ways not photography but a form of painting. To answer this challenge one would have to show that the photographic process involves possibilities for expression of the artist's thought and style that lie outside of Scruton's stark options.

Articles by David Davies and Patrick Maynard follow and counter Scruton's argument by going into details of photographic composition. Davies' "How Photographs Signify" takes direct aim at Scruton's argument by developing ideas drawn from Rudolph Arnheim and Cartier-Bresson. Davies shows how the geometry of a carefully composed photograph prevents the viewer from perceiving it as a "transparent window upon its subject" and instead leads her "to see the subject in a particular way." So, contra Scruton, there is a "thought embodied in perceptual form" (182-183). Maynard ("Scales of Space and Time in Photography") presents the most detailed analysis of the various dimensions of a photograph -- negative space, dynamics, etc. -- to argue that there are "inextricable but irreducible artistic values in snapshot art." Savedoff's sensitive discussion of various genres of art photography also provides weight to the argument against Scruton.

A third theme of the collection involves comparisons between films and still photographs. Scruton inspects film's credentials to be art in spite of its being a series of photographs (an artistic defect from his point of view). Gregory Currie ("Photography and the Power of Narrative") compares the ability of still photographs and film to support a narrative. In his second contribution to the anthology, "Landscape and Still Life," Walton investigates the differences between what can be depicted in a still picture and in a moving picture. Both Walton and Currie sketch accounts of the viewer's imaginative experience to explain the difference between what can be depicted in still and moving photographs.

Noël Carroll ("The Problem with Movie Stars") notes that movie stars often bring a persona to a movie role and that this persona is sometimes essential to our understanding of the narrative of the movie. He argues that this fact is inconsistent with standard assumptions about how we should understand fictional narratives. These assumptions dictate that extra-work information about an actor is not relevant to an understanding of the fictional world of the work. The cognitive background relevant to appreciating photographs as photographs is also explored by Dominic Lopes ("True Appreciation"). He contrasts two principles of adequate appreciation in general. One drawn from the theories of nature appreciation of Allen Carlson and Malcolm Budd requires that "an appreciation of O as a K is adequate only if O is a K" (212). One's appreciation of a whale will be inadequate if one appreciates it as a fish rather than a mammal. A different principle requires that "an appreciation of O as a K is adequate only as far as it does not depend counterfactually on any belief that is inconsistent with the truth about the nature of Ks" (213). He suggests reasons to favor the latter requirement as a general principle. However, this principle implies that our aesthetic appreciation of photographs is inadequate to the degree that we find them compelling because we have false beliefs about the accuracy with which photography records how things look.

I note in conclusion that Walden provides a thorough Introduction and an extensive Bibliography. As you would expect, there are photographs (32 of them) that illustrate the arguments. There is also a substantial Index, which is a bonus in an edited book. All in all, this is a very valuable collection that gathers together a set of articles and issues that should be of general interest to philosophers of art. As an anthology of analytic philosophy of art this collection may be most appropriate for upper-division and graduate aesthetics courses, although it would also be a provocative addition to interdisciplinary courses in photographic or film theory.

Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide a journal of nineteenth-century visual culture

Photography and the Arts: Essays on Nineteenth-Century Practices and Debates edited by Juliet Hacking and Joanne Lukitsh

Andrés Mario Zervigón Professor of the History of Photography Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey Email the author: Zervigon[at]rutgers.edu

Citation: Andrés Mario Zervigón, book review of Photography and the Arts: Essays on Nineteenth-Century Practices and Debates edited by Juliet Hacking and Joanne Lukitsh, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 22, no. 1 (Spring 2023), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2023.22.1.15 .

Juliet Hacking and Joanne Lukitsh, eds., Photography and the Arts: Essays on Nineteenth-Century Practices and Debates . London: Bloomsbury, 2020. 248 pp.; 62 b&w illus.; bibliography; index. $120 (hardcover), $32.95 (paperback) ISBN: 9781350048539 ISBN: 9781350283527

Earlier last summer in 2022, the two editors of Photography and the Arts staged a book launch at Photography Network with a provocative query: “Who’s Afraid of Art Photography?” The question, they readily admitted, recalled the postmodern critique of photography primarily waged by contributors to the journal October in the late 1970s and early 1980s. As a group, these critics and academics called into question—among other things—the creative ambitions of nineteenth-century photographers. Even more pointedly, they criticized the collecting and exhibition prerogatives of contemporary curators who championed such aspirations or perceived them in purely functional photography. Aesthetics in the medium’s first century, the October -based authors maintained, had to be understood as an archaic relic of modernist aesthetic conventions that the same postmodern intervention sought to debunk. Since then, discussions of ambitious art practices in nineteenth-century photography (or the conjuring of their presence) have appeared suspect at best, if not outright retrograde in our current historiographical context that still trades heavily in the currency of vernacular photography with all its quotidian patina. Why turn our attention to elite images when they represent only a fraction of the photographs produced and consumed in the medium’s early decades? Is not such a focus itself elitist and shortsighted? As editors Juliet Hacking (Sotheby’s Institute of Art, London) and Joanne Lukitsh (Massachusetts College of Art and Design) suggested at their launch, scholars and critics have grown fearful of early art photography as a subject of study, even if for legitimate reasons.

Their response to such trepidation is to broaden the category of art photography to the more capacious rubric of ambitious photography and suggest, in turn, that there’s a great deal more at stake in such images than their pleasing or sublime aesthetics may imply. As the editors and their contributors demonstrate, some of the most profound debates on the medium in the nineteenth century circled around enterprising image makers, generating photographic discourses and bracing pictures that tell us much more about their moment than we would know if we did not take such practices seriously and understand them on their own aesthetic terms. The editors and their contributors do just this in a useful historiographical introduction and twelve chapters. The reader comes away from the texts with a number of useful insights. Images and—more specifically—objects presented through the category of art did not just make beauty and philosophy possible in a medium closely associated with the mechanical and the functional. They also enabled several seemingly unrelated discourses to enter visual cultures under the cover of elegant art. In the images under scrutiny, such rubrics perform the work of dehumanization, colonialism, and nationalism, while others serve to promote new technologies and related reproductive media. Beauty, in other words, often served—intentionally or not—as a fig leaf in photographs with other agendas seemingly well outside the realm of art. Establishing this fact, along with making fundamental additions to our historical knowledge of photography, represents the volume’s primary contribution.

The introduction opens the book with a useful discussion of the state of the field, specifically as regards studies of nineteenth-century photography and the twentieth-century understandings of art that were mapped onto it retrospectively. What becomes clear in the first two pages is that Hacking and Lukitsh take the October -based critique and its postmodernist considerations seriously. As these critics from the 1970s and 1980s would advise, the editors and their contributors aim to restore the plurality of photography in the medium’s first century, making room for discussion of practical prints meant for information, documentation, evidence, illustration, and reportage, as well as those consciously presented as fine art. The diversity that the editors and their contributors navigate generally fits under a nineteenth-century rubric of “the arts,” which was far more capacious and embracing than it is for us today. The category included such things as electroplating, eclectic forms of reproduction such as plaster casting, colonial pictorial documentation, news reporting, and narration, all of which are covered in the volume. Few of these categories and the networks they generated consistently accord with the modernist photographic “way of seeing” that classic twentieth-century histories of the medium retrospectively took as their aesthetic standard for serious nineteenth-century prints. As the editors explain, the book “claims a significance for historical interactions between photography and the arts beyond matters of cultural status, judgements of quality or taxonomy” (1). What their openness to “the arts” laudably enables is a series of inter-medial investigations that show just how closely bound various forms of reproduction became once brought together over a primary objective, such as cataloging insects or building types. Teasing out the complex relationships that such investigations require constitutes a chief aim of the contributors as well, as they explore the social, political, scientific, and economic conditions that gave rise to specific bodies of photographs and the conditions through which those pictures can be understood today. The introduction brilliantly unpacks the historiographic significance of this approach for the medium’s first century.