Weak Procurement Practices and the Challenges of Service Delivery in South Africa

- First Online: 18 February 2021

Cite this chapter

- Koliswa Matebese-Notshulwana 3

261 Accesses

1 Citations

Procurement is a crucial institutional process and measure for the functioning of government, regarding service delivery. As such, it is important that such a process is characterised by ethical standards to ensure that service delivery is not compromised and undermined. However, despite the establishment of oversight mechanisms to monitor irregular, wasteful and unauthorised expenditure, corruption in procurement remains a challenge. One of the major problems is non-compliance with the requisite legislative frameworks. Consequently, weak procurement practices and corruption have a significant impact in the attainment of good governance. Although procurement plays a major and strategic role in the acquisition of goods and services, it is one of government’s activities that is most vulnerable to waste, fraud and corruption. Methodologically, desktop research was used with content analysis of the various primary and secondary resource material. The chapter concludes that the effect of corruption in procurement has seriously constrained sustainable economic development and seriously affected service delivery in South Africa. The chapter therefore recommends that there should be consequences for non-compliance and misuse of public resources and institutional entities must ensure full compliance with procurement legislation and processes.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

AGSA. (2014). Auditor-General on Use of Audit Reports as an Oversight Tool; Financial & Fiscal Commission on Department of Mineral Resource’s Past Performance & Future Projections [Accessed 28 May 2019].

Google Scholar

Alexander, P. (2013). Protest and Police Statistics in South Africa: Some Commentary. Popular Resistance, Daily Movement News and Resources . https://www.popularresistance.org/south-africathe-rebellion-of-the-poor/ [Accessed 27 May 2019].

Ambe, I. M. (2009). An Exploration of Supply Chain Management Practices in the Central District Municipality. Educational Research and Review, 4 (9), 427–435.

Ambe, I. M. (2016). Public Procurement Trends and Developments in South Africa. Research Journal of Business and Management. Unisa Press Academia, 3 (4), 277–290 [Accessed 27 May 2019].

Ambe, I. M., & Badenhorst, J. A. (2011). An Exploration of Public Sector Supply Chains with Specific Reference to the South African Situation. Journal of Public Administration, 46 (3), 1101–1113. [Accessed 10 January 2019].

Ambe, I. M., & Badenhorst, J. A. (2012). Procurement Challenges in the South African Public Sector. Journal of Transport and Supply Chain Management, 242–261 [Accessed 27 May 2019].

Bolton, P. (2006). Government Procurement as a Policy Tool in South Africa. Journal of Public Procurement, 6 (3), 193–217.

Article Google Scholar

Cane, P. (2004). Administrative Law (4th ed.). London: Oxford University Press.

CIPS Australia. (2005). How Do We Measure Up? An Introduction to Performance Measurement of the Procurement Profession [Accessed 17 May 2019].

Cogta. (2009). State of Local Government Report . Overview Report. Pretoria.

De Lange S. (2011). Irregular State Expenditure Jumps 62% . Business Day [Accessed 20 May 2019].

Dlova, V., & Nzewi, O. (2014). Developing and Institutionalising Supply Chain Management Procedures: A Case Study of the Eastern Cape Department of Roads and Public Works. Africa’s Public Service Delivery and Performance Review, 2 (1), 5–21.

DTI. (2012). Industrial Procurement and Designation of the Sectors . http://www.thedti.gov.za/parliament/industrial.procurement.pdf.Design [Accessed 15 May 2019].

DTI. (2013). Industrial Policy Action Plan . http://www.thedti.gov.za/news2013/ipap_2013–2016.pdf [Accessed 21 May 2019].

Eyaa, S., & Oluka, P. N. (2011). Explaining Noncompliance in Public Procurement in Uganda. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2 (11), 35–44.

Gelderman, J. C., Ghijsen, W. P., & Brugman, J. M. (2006). Public Procurement and EU Tendering Directives Explaining Non-compliance. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 19 (7), 702–714.

Godi, T. (2014). Auditor-General on Audit Outcomes for 2013–2014. Parliamentary Monitoring Group. Parliament. Cape Town.

Gurría, A. (2016). Public Procurement for Sustainable and Inclusive Growth: Enabling Reform Through Evidence and Peer Reviews . OECD. http://www.oecd.org/gov/ethics/PublicProcurementRev9.pdf [Accessed on 19 May 2019].

Heymans, C., & Lipietz, B. (1999). Corruption and Development. Institute of Security Studies (ISS) Monograph Series, 40, 9–20.

Hommen, L., & Rolfstam, M. (2009). Public Procurement and Innovation: Towards a Taxonomy. Journal of Public Procurement, 9 (1), 17–56.

Jeppesen, R. (2010). Accountability in Public Procurement: Transparency and the Role of Civil Society. United Nations Procurement Capacity Development Centre .

Kashap, S. (2004). Public Procurement as a Social, Economic and Political Policy . International public procurement conference proceedings, 3:133–147.

Kruger, L. P. (2011). The Impact of Black Economic Empowerment (Bee) on South African Businesses: Focusing on Ten Dimensions of Business Performance. Southern African Business Review, 15 (3), 207–233.

Mahlaba, P. J. (2004). Fraud and Corruption in the Public Sector: An Audit Perspective. S D R, 3 (2), 84–87.

Mahmood, S. (2013). Public Procurement System and e-Government Implementation in Bangladesh: The Role of Public Administration. Journal of Public Administration and Policy Research, 5 (5), 117–123.

Mail & Guardian. (2015). Government Supplier Database: A Blow to Corruption . http://mg.co.za/article/2015-03-05-govt-supplierdatabase-a-blow-to-corruption [Accessed on 13 April 2019].

Makwethu, K. (2014). Auditor-General on Audit Outcomes for 2013–2014 . Parliament. Cape Town.

Matthee, C. A. (2006). The Potential of Internal Audit to Enhance Supply Chain Management Outcomes . Master’s dissertation, University of Stellenbosch, Stellenbosch.

McCrudden, C. (2004). Using Public Procurement to Achieve Social Outcomes. Natural Resources Forum , 257–267.

Mkhize, C. Y. (2004). A Handbook of Community Development . Pretoria: Skotaville Media Publications.

Mukura, P. K.; Shalle, N., Kanda, M. K., & Ngatia, P. M. (2016). Role of Public Procurement Oversight Authority on Procurement Regulations in Kenyan State Corporations. A Case of Kenya Electricity Generating Company (KenGen). International Journal of Academic Research in Accounting, Finance and Management Sciences, 6 (3), 190–201.

Munzhedzi, P. H. (2016). South African Public Sector Procurement and Corruption: Inseparable Twins? Journal of Transport and Supply Chain Management, 10 (1), 1–8 [Accessed 4 April 2019].

Mwangi, P. N. (2017). Determinants of compliance with access to government procurement opportunities regulations for special groups by public universities in Kenya . PhD Thesis, Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology.

Ngcobo, Z., & Whittles, G. (2016). ANC Vows to Speed Up Pace of Service Delivery from August, Eye Witness News . http://ewn.co.za/2016/04/18/ANC-to-speed-up-service-delivery-from-August 18 May.

National Treasury. (2003). Policy Strategy to Guide Uniformity in Procurement Reforms Processes in Government . Pretoria [Accessed 23 May 2019].

National Treasury. (2015). Public Sector Supply Chain Management Review . Department of National Treasury, Republic of South Africa. pp. 1–83 [Accessed 28 May 2019].

National Treasury. (2017). Terms of Reference. Appointment of a service provider to assist the Office of the Chief Procurement Officer within the National Treasury, South Africa with the development of a procurement codification standard for the period of 12 months. pp. 1–66 [Accessed 28 May 2019].

Odhiambo, W., & Kamau, P. (2003). The Integration of Developing Countries into the World Trading System . Public Procurement Lessons for Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda. Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, (OECD)-DAC/World Bank. (2005). Guidelines and Reference Series . A DAC Reference Document Harmonizing Donor.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, (OECD). (2007). SIGMA Support for Improvement in Governance and Management . http://sigmaweb.org .

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, (OECD). (2011). Demand-side Innovation Policies . Paris.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, (OECD). (2015). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Fighting Corruption in the Public Sector: Public Procurement . http://www.oecd.org/gov/ethics/integrityinpublicprocurement.htm .

Payan, J. M., & McFarland, R. G. (2005). Decomposing Influence Strategies: Argument Structure and Dependence Determinants of Effectiveness of Influence Strategies in Gaining Channel Member Compliance. Journal of Marketing, 69, 66–79 [Accessed 19 March 2019].

Pillay, S. (2004). Corruption–The Challenge to Good Governance: A South African Perspective. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 17 (7), 586–605.

Pithouse, R. (2012, August, 6). Burning Message to the State in the Fire of Poor’s Rebellion . Business Day.

Porteous, E., & Naudé, F. (2012). Public Sector Procurement: The New Rules . http://www.apmp.org.za/public [Accessed 3 March 2019].

Ramaphosa, C. M. (2018). State of the Nation Address (SONA). Parliament of South Africa, Cape Town.

Rondinelli, D. A. (2007). Can Public Enterprises Contribute to Development? A Critical Assessment and Alternatives for Management Improvement. New York: United Nations.

Roodhooft, F., & Abbeele, A. V. D. (2006). Public Procurement of Consulting Services: Evidence and Comparison with Private Companies. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 19 (5), 490–512.

SCM Review Update. (2016). SCM Review Update. National Treasury. www.treasury.gov.za .

Smart Procurement. (2011). SA Public Procurement: Poor Value for Money. In I. M. Ambe, & J. A. Badenhorst-Weiss. (2012, November 7). Supply Chain Management Challenges in the South African Public Sector. African Journal of Business Management, 6 (44), 11003–11014 [Accessed 20 May 2019].

Soreide, I. (2002). Corruption in Public Procurement Causes, Consequences and Cures . Chr. Michelsen Institute, 1–41.

Soudry, O. (2007). A Principal-Agent Analysis of Accountability in Public Procurement. In Gustavo Piga & Khi V. Thai (Eds.), Advancing Public Procurement: Practices, Innovation and Knowledge-Sharing (pp. 432-451). Boca Raton, FL: PrAcademics Press.

State of the Nation Address. (2018). Parliament of the Republic of South Africa . Cape Town.

Stapenhurst, R.. Pelizzo, R., Olson, D. M., & von Trapp, L. (2006). Legislative and Budgeting Oversight: A World Perspective . Washington, DC: World Bank Institute.

Turley, L., & Perera, O. (2014). Implementing Sustainable Public Procurement in South Africa: Where to Start. The International Institute for Sustainable Development, 1–63.

Wallis, M. (1999). The Final Constitution: The Elevation of Local Government. In Cameron, R. (1999). Democratisation of South African Local Government: A Tale of Three Cities . Pretoria: Van Schaik [Accessed 26 May 2019].

Warren, M. E. (2004). What Does Corruption Mean in a Democracy? American Journal of Political Science. Midwest Political Science Association, 48 (2), 328–343.

Watermeyer, R. B. (2011, October 25). Regulating Public Procurement in Southern Africa Through International and National Standards . Public Procurement Regulation in Africa Conference, Stellenbosch.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Political Science, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

Koliswa Matebese-Notshulwana

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Durban University of Technology, Durban, South Africa

Nirmala Dorasamy

Omololu Fagbadebo

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Matebese-Notshulwana, K. (2021). Weak Procurement Practices and the Challenges of Service Delivery in South Africa. In: Dorasamy, N., Fagbadebo, O. (eds) Public Procurement, Corruption and the Crisis of Governance in Africa. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-63857-3_6

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-63857-3_6

Published : 18 February 2021

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-63856-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-63857-3

eBook Packages : Political Science and International Studies Political Science and International Studies (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Open access

- Published: 12 April 2022

Improving public health sector service delivery in the Free State, South Africa: development of a provincial intervention model

- Benjamin Malakoane 1 ,

- James Christoffel Heunis 2 ,

- Perpetual Chikobvu 3 ,

- Nanteza Gladys Kigozi 2 &

- Willem Hendrik Kruger 1

BMC Health Services Research volume 22 , Article number: 486 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

6332 Accesses

4 Citations

Metrics details

Public health sector service delivery challenges leading to poor population health outcomes have been observed in the Free State province of South Africa for the past decade. A multi-method situation appraisal of the different functional domains revealed serious health system deficiencies and operational defects, notably fragmentation of healthcare programmes and frontline services, as well as challenges related to governance, accountability and human resources for health. It was therefore necessary to develop a system-wide intervention to comprehensively address defects in the operation of the public health system and its major components.

This study describes the development of the ‘Health Systems Governance & Accountability’ (HSGA) intervention model by the Free State Department of Health (FSDoH) in collaboration with the community and other stakeholders following a participatory action approach. Documented information collected during routine management processes were reviewed for this paper. Starting in March 2013, the development of the HSGA intervention model and the concomitant application of Kaplan and Norton’s (1992) Balanced Scorecard performance measurement tool was informed by the World Health Organization’s (2007) conceptual framework for health system strengthening and reform comprised of six health system ‘building blocks.’ The multiple and overlapping processes and actions to develop the intervention are described according to the four steps in Kaplan et al.’s (2013) systems approach to health systems strengthening: (i) problem identification, (ii) description, (iii) alteration and (iv) implementation.

The finalisation of the HSGA intervention model before end-2013 was a prelude to the development of the FSDoH’s Strategic Transformation Plan 2015–2030. The HSGA intervention model was used as a tool to implement and integrate the Plan’s programmes moving forward with a consistent focus on the six building blocks for health systems strengthening and the all-important linkages between them.

The model was developed to address fragmentation and improve public health service delivery by the provincial health department. In January 2016, the intervention model became an official departmental policy, meaning that it was approved for implementation, compliance, monitoring and reporting, and became the guiding framework for health systems strengthening and transform in the Free State.

Peer Review reports

The Free State province of South Africa has recorded substandard population health outcomes at least since 2011 [ 1 ]. The dire need for effective and implementable interventions to improve public health services and outcomes is clear [ 2 ]. To avoid resource wastage, efforts should be made to systematically design health systems strengthening interventions with the potential of system-wide implementation [ 3 , 4 , 5 ].

When a new Member of the Executive Council (first author) assumed leadership of the Free State Department of Health (FSDoH) in 2013 there was a clear need to address the rising burden of both communicable and non-communicable disease [ 6 ], as well as declining community trust in the public health system. The Member of the Executive Council outlined a vision to “strengthen the health system’s effectiveness, drive system changes, improve burden of disease outcomes, [and] ensure financial sustainability for better health outcomes and increased life expectancy.”

A multi-method situation appraisal of the FSDoH’s public health services was undertaken by the first author, a senior programme manager (third author) in collaboration with two health systems researchers (second and fourth authors) and a community health specialist (fifth author) in collaboration with healthcare workers in 2013. The appraisal established that the main overall system challenges underlying sub-standard performance in the province included fragmentation of services, staff shortages, financial/cash-flow problems and leadership and governance defects [ 1 ]. There was a clear need to improve programme integration and leadership, and to address organisational, human resources and financial deficiencies in this setting. The above-mentioned team collaborated in developing, implementing and evaluating a whole-system intervention to improve public health service integration and outcomes, namely the Health Systems Governance & Accountability (HSGA) intervention.

Although no universal definition or concept of integration exists [ 7 ], in 2005, the World Health Organization (WHO) explained the term as follows: “The notion of integration has a long history. Integration is supposed to tackle the need for complementarity of different interdependent services and administrative structures, so as to better achieve common goals. In the 1950s these goals were defined in terms of outcome, in the 1960s of process and in the 1990s of economic impact” [ 8 pp. 108–109]. A systematic review conducted in 2016 defined integration as “a variety of managerial and operational changes to health systems that bring together inputs, delivery, management, and organizations of particular service functions, in order to provide clients with a continuum of preventative and curative services, according to their needs over time and across different levels of the health system” [ 9 p. 2]. The WHO suggests that integration has to take place at three levels: (i) patient level, i.e., case management; (ii) service delivery level, i.e., multiple interventions provided through one delivery channel and (iii) systems level, i.e., bringing together the management and support functions of different sub-programmes, and ensuring complementarity between the different levels of care [ 8 ]. Integration is a choice that affects programme financing, planning and delivery, and, ultimately, the achievement of public health goals [ 10 , 11 ].

Integration of disease control programmes such as the HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and chronic disease programmes within the district health system and comprehensive primary health care (PHC) approach has been a priority in South Africa for decades [ 12 , 13 ]. However, attempts at integration are hindered by leadership and management challenges as observed in three provinces in the complex dynamics between managers responsible for specific policies and those responsible for managing the integrated delivery of all policies [ 14 ].

The WHO [ 2 , 15 ] advances that health systems are comprised of six ‘building blocks’ that need to be considered in health system strengthening: (i) service delivery; (ii) health workforce; (iii) information; (iv) medical products, vaccines and technologies; (v) financing and (vi) leadership and governance (stewardship). The building blocks framework has been found to be useful to assess in-country health system performance [ 16 , 17 , 18 ]. However, there is some uncertainty as to how the framework can best be used to address the problems of fragmentation and ineffective performance of public health systems in low- and middle-income countries. Mounier-Jack et al. [ 19 ] thus recommended that researchers using the building blocks framework should adapt it and make it context-specific.

The FSDoH leadership believed that conceptualisation of the public health system in terms of the building blocks framework and improved integration of service programming and rendering through, amongst others, reconfigured facility clusters and service hubs, would help to address a broad spectrum of health system challenges. The decision was therefore made to design and develop a system-wide re-engineering intervention to address the fragmentation of healthcare provisioning using a systems approach. The working definition for a systems approach was one that “applies scientific insights to understand the elements that influence health outcomes; models the relationships between those elements; and alters design, processes, or policies based on the resultant knowledge in order to produce better health at lower cost” [ 20 p. 4].

Health systems are complex and characterised by high levels of variability, uncertainty, and dynamism [ 21 ]. Kaplan et al. (2013) [ 20 ] proposed that the use of a systems approach is beneficial in addressing complex health systems challenges by considering the dynamic interaction among the multiple elements (i.e., people, processes, policies, and organisations) involved in caring for patients and the multiple factors influencing health. These authors proposed four essential considerations or steps in designing interventions from the perspective of a systems approach, (i) identification, (ii) description, (iii) alteration and (iv) implementation. These steps were followed in the development of the HSGA intervention model in the Free State. Kaplan and Norton’s (1992) Balanced Scorecard performance measurement tool [ 4 ] was concomitantly put in use.

Details on the implementation and assessment of the intervention including the results of a questionnaire survey and focus group discussions with health managers and community representatives will be reported elsewhere. This descriptive study relates the development of an intelligible and promising intervention, the HSGA intervention model, and its formalisation into an official policy, the HSGA policy, to address fragmentation and improve public health service delivery in the Free State by the provincial health department in collaboration with its stakeholders. A participatory design involving a wide range of public health stakeholders and role players in plans and efforts to improve the integration and outcomes of public health services was followed as part of routine health service delivery management processes.

The FSDoH serves a population of approximately 2.9 million people [ 22 ], of whom about 80% are public health sector dependent [ 23 ]. The province includes four district municipalities, Fezile Dabi, Lejweleputswa, Thabo Mofutsanyana and Xhariep, and one metropolitan municipality, Mangaung. In 2015/16, PHC was provided by 211 fixed PHC clinics, ten community health centres and numerous mobile clinics [ 6 ]. Hospital services included 24 district hospitals, four regional hospitals, one specialised psychiatric hospital, one tertiary hospital and one central hospital. The PHC clinics, community health centres and hospitals respectively provide primary, secondary, and tertiary care services. Hospitals are managed by chief executive officers with hospital boards providing oversight or governance. PHC clinics and community health centres are managed by operational managers reporting to their respective district offices. Clinic committees provide oversight or governance and report to the provincial executive authority. District health managers are responsible for planning and monitoring of disease control programme implementation within their districts, with District Clinical Specialist Teams providing supportive supervision, clinical governance, and attending to health systems and logistics, staff development and user-related considerations [ 24 ].

The development of the HSGA intervention model followed a participatory action approach [ 25 , 26 , 27 ] as part of routine health service delivery management processes which took place from 2013 to 2015. The reports and minutes generated during these routine management processes were reviewed using the WHO health systems building blocks framework to conceptualise the intervention. This approach was chosen as it has been shown that interventions developed using participatory designs are more likely to be acceptable and implemented effectively [ 28 , 29 ]. A province-wide consultative process was embarked upon, wherein communities and stakeholders within the public health system were called upon to comment on the different functional domains: (i) the skill base of the management; (ii) patient and clinical workflow; (iii) the referral system and (iv) leadership alignment to community and operational needs, process reliability, and attainment of the desired outcomes [ 1 ]. The involvement of both managers and communities in shaping the HSGA intervention model empowered the executive authority to lead health system change and administrative action [ 30 ]. The designations of 584 FSDoH functionaries, community representatives, and other stakeholders who partook in the development of the model as part of routine health service delivery management processes from 2013 to 2015 are indicated in Table 1 .

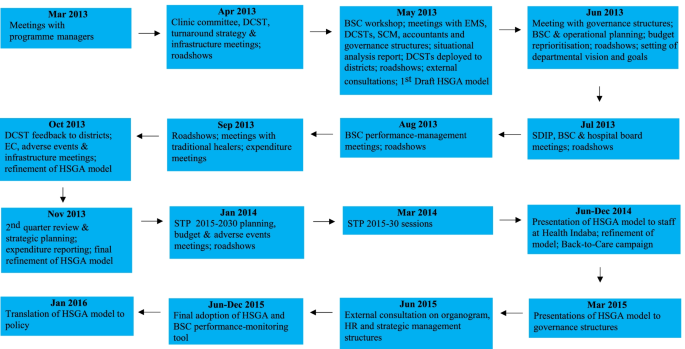

Key activities in the development process of the HSGA intervention model

The chronology of key activities in the development of the HSGA intervention model is depicted in Fig. 1 .

Key activities in HSGA intervention model development

BSC Balanced Scorecard, DCST District Clinical Specialist Team, EMS emergency medical services, EC Executive Committee, HR human resources, MEC Member of the Executive Committee, PHC primary health care, SCM supply change management, SDIP Service Delivery Improvement Plan, STP Strategic Transformation Plan

During March–April 2013, the executive management held meetings with PHC clinic committees and infrastructure improvement teams to understand the healthcare challenges faced by catchment communities, as well as the state of PHC infrastructure. Given that key health systems challenges had been identified in the preceding multifaceted situational analysis [ 1 ], the community engagements were aimed at teasing out specific malleable challenges from a wide range of health systems problems facing the province. During the same period, and for the same reason, hospital and PHC clinic ‘roadshows’ (organised campaigns carried out in identified catchment areas led by the executive leadership) commenced and turnaround strategy discussions were held at the corporate level.

During May 2013, in a quest to assess the status and quality of Emergency Medical Services, the referral system and patient and clinical workflow, as well as the management skill base and the budget support received in doing their work, various meetings were held with Emergency Medical Services, District Clinical Specialist Teams, supply chain management and governance structures in order to understand the status quo and leadership alignment to community and operational needs, process reliability, identification of areas needing intervention, and attainment of the desired outcomes.

Hospital and PHC clinic roadshows continued, and the first Balanced Scorecard workshop was conducted. Often applied to healthcare settings and organisations [ 31 , 32 , 33 ], the Balanced Scorecard performance measures include four questions or perspectives: (i) how do customers see us? (customer perspective); (ii) what must we excel at? (internal perspective); (iii) can we continue to improve and create value? (innovation and learning perspective) and (iv) how do we look to shareholders? (financial perspective) [ 4 ]. The Balanced Scorecard was adopted to enable production of evidence and tracking of progress when reporting. The Balanced Scorecard workshop culminated in the development of the first draft of the HSGA intervention model accompanied by relevant policy and procedure reviews to introduce a culture of coordination and communication within the confines of policy provisions.

The executive authority then presented the findings of the previous three months to the corporate and district-level managers with new mandates being given to various staff components. The District Clinical Specialist Teams were specifically responsible to visit PHC clinics and hospitals in their respective districts to conduct surveillance and monitoring of effectiveness of clinical protocols. They were to complete the investigation of the challenges and to provide recommendations within five months.

The PHC clinic committee and hospital board (governance) structures are by their nature, community advocacy formations. Meetings with them continued into June-July 2013 in tandem with the hospital and PHC clinic roadshows. A plan to operationalise the Balanced Scorecard was drafted, and budget reprioritisation sessions held. Additional meetings took place to discuss ways to conform to the new Service Delivery Improvement Plan and the Balanced Scorecard approach. Besides the continuation of hospital and PHC clinic roadshows, Balanced Scorecard and expenditure reporting meetings were held during August–September 2013 to discuss ways to improve programme performance.

During October–November 2013, the District Clinical Specialist Teams had returned from their five-month expedition into the districts. They provided feedback covering the sub-districts visited and problem areas identified. The HSGA intervention model was then refined to address the shortcomings identified and relevant policies and procedures were amended accordingly. After the second quarter performance review process and expenditure reporting, the model was further refined to streamline the interventions with policy and procedure reviews.

During January-March 2014, the Strategic Transformation Plan 2015–2030 [ 34 ] processes related to format, programmes and content were commenced, and relevant functionaries invited with clear mandates to present their ideas on what could further be done to improve service and programme delivery to the executive and senior management, including programme managers. Thereafter, the hospital and PHC clinic roadshows were completed in the last of the districts. The draft HSGA intervention model was also presented to the staff and stakeholders at a province-wide health ‘ indaba ’ (collective discussion or meeting). Thereafter, the model was further refined together with concomitant changes to policies and procedures.

During March-December 2015, the HSGA intervention model was presented to governance structures and across the whole department to progressively introduce the new way of working, which would inform the performance assessment system according to the Balanced Scorecard approach as well. External consultants were involved in helping to refine the strategic management issues and in assisting the streamlining of the organogram to address the changes to be implemented. The Balanced Scorecard was thus used during performance assessments to test compliance with the needed changes.

Finally, in January 2016, the HSGA intervention model became an official departmental policy [ 35 ]. The intention of the HSGA policy was to ensure the sustainability of implementation of the HSGA intervention model to strengthen compliance and entrench a culture of using the model as an operational system to achieve the aims of the Strategic Transformation Plan 2015–2030. Information gathered in the above processes was synthesised using an iterative participatory design approach with three main steps: (i) consultations, (ii) incorporating suggestions and (iii) revisions. Repeated consultations with a broad range of stakeholders (Table 1 ) took place where inputs were sought, and changes incorporated as part of health services delivery management process. By doing so, the HSGA intervention model was refined at each consultation point. Final revision followed an indaba with the executive leadership, District Management Teams, community representatives, departmental line managers, governance structures, labour organisations, academics, traditional leaders and healers, and PHC clinic committees. They proposed changes to clusters and service hubs and focused on ensuring that the content of the intervention model was appropriate and consistent with the National Department of Health’s (NDoH) guidelines as this would allow for easier embedding of the model into routine care and was likely to make it more acceptable to healthcare managers and workers.

Development of the intervention

The development of the HSGA intervention model is subsequently related according to the four steps outlined by Kaplan et al. [ 20 ].

Step 1: Identification

Kaplan et al. [ 20 p. 5] define this step as follows: “Identify the multiple elements involved in caring for patients and promoting the health of individuals and populations.” In the context of the development of the HSGA intervention model, this implied identifying all those elements involved in service delivery whose improvement would lead to improved integration and health outcomes. The identification of the multiple health system factors contributing to poor health service delivery was described by Malakoane et al. [ 1 ] and further investigated during the model development activities (Fig. 1 ).

In summary, a multi-method situation appraisal based on analysis of 44 reports generated in 2013 through presentations by unit managers, sub-district assessments by District Clinical Specialist Teams, and group discussions with district managers, PHC clinic supervisors and managers, and chief executive and clinical officers at all hospital levels was conducted. The appraisal established that the rising burden of disease and poor health outcomes were principally due to extant fragmentation of health service delivery and the disjointed way in which the public health system was operating. Other problems included poor policy and regulatory coordination, verticalisation of programme organisation and administration, staff shortages, budgetary problems, and, notably, leadership and governance deficits, as significant health system challenges that resulted in ineffective public healthcare service delivery [ 1 ].

Specific challenges with respect to people, processes and policy shortfalls within the health system are depicted in Table 2 in line with the WHO health systems building blocks framework. All the elements involved in service delivery that were investigated during the model development activities (Fig. 1 ) and whose improvement would lead to improved integration and health outcomes were consolidated in reports and minutes. These reports and minutes of the meetings were then thematically synthesized.

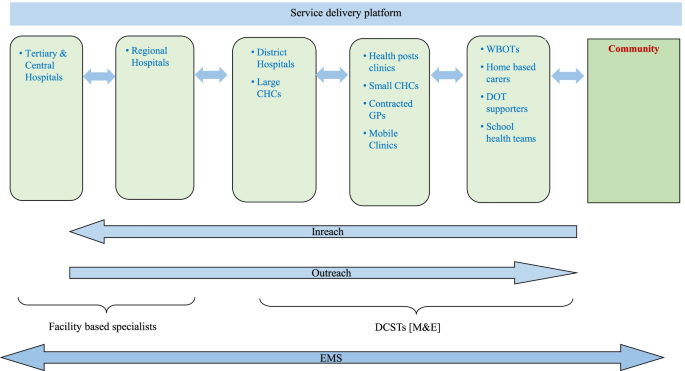

Step 2: Description

Kaplan et al. [ 20 p. 5] defines this step as follows: “Describe how those elements [aspects involved in caring for patients and promoting the health of individuals and populations] operate independently and interdependently.” The decision to reconfigure the public healthcare delivery platform for better integration of services and improved population-health outcomes was inevitable and required an intelligible and feasible intervention. In view of the multiple challenges that were identified (Table 2 ), and the extent to which continuation of these challenges impacted or infringed patients’ rights, the strengthening of the public health system was approached by means of systematic application of the WHO’s building blocks framework. It was particularly important to bring about a well-planned and managed referral system supported by policy and regulation and to deploy adequate resources across all levels of care [ 36 , 37 ]. The HSGA intervention model was intended to address, interlink and integrate all the public health service delivery processes for better outcomes (Fig. 2 ).

Service delivery platform

‘Inreach’ refers to referral to a higher level of care. CHC community health centre, DCST District Clinical Specialist Team, DOT directly observed treatment, EMS emergency medical services, GP general practitioner, M&E monitoring and evaluation, WBOT Ward Based Outreach Team

The executive leadership convened all the corporate managers, district managers, programme managers, hospital chief executive officers and clinic managers (Table 1 ) to discuss the findings of the situation appraisal. These discussions focused on required alterations to improve the public health system’s performance and advance cooperation between facilities and functionaries to enable integration of healthcare service delivery in consideration of the six WHO health system building blocks. It was agreed that a system to integrate the service delivery platform had to be developed. The executive leadership revisited and outlined the vision and trajectory for this, with a view to identify possible changes including goals aimed at achieving better health outcomes.

The vision for the required reconfiguration of the health system provided by the leadership was to: “increase life expectancy through health system effectiveness, driving system change and ensuring sustainable quality services.” Implementation of the intervention was expected to achieve seven departmental goals whose achievement would lead to the expected health outcomes envisaged during the intervention formulation: (i) provision of strategic leadership and creation of a social compact for better health outcomes; (ii) managing the financial affairs for sustainable health service delivery; (iii) building a strategic and dedicated workforce that is responsive to service demands; (iv) re-engineering PHC to improve access to quality services; (v) developing, operating and managing infrastructure for compliance and better health outcomes; (vi) strengthening the information and knowledge management system to optimise performance and research capabilities and (vii) optimising and supporting implementation of key priority programmes (transformation, affirmative action and business process re-engineering).

The main factors to be addressed included mainstreaming of the WHO health systems building blocks, strengthening of policies and procedures, re-engineering of patient admission and discharge, and improving the leadership capacity of managers. Amongst the malleable factors included were aspects forming part of the managers’ additional duties and reporting responsibilities, firstly, in terms of the service delivery building block, improved integration; and, secondly, in respect of the leadership/governance building block, appropriate distribution of delegated powers within the system.

Emergency Medical Services are crucial in ensuring consistent accessibility of the different levels of healthcare through the referral system. There was a need to review the referral policy and guidelines and to reconfigure referral pathways to enable easier and quicker access to services with the referral of patients to the closest health facility in times of need and to reduce the number of patient transport and emergency vehicles on the road so as to reduce operational costs.

Reconfiguration of the health service platform was to entail, firstly, that the fixed PHC facilities had to be grouped into clusters such that each cluster would consist of a community health centre or 24-h clinic with a number of fixed PHC clinics, mobile clinics, health posts, and Ward Based Outreach Teams referring to it within a given vicinity and not necessarily aligned to municipal boundaries. The composition of these teams is six to ten community health workers, a data capturer and a team leader. In terms of South Africa’s PHC re-engineering agenda [ 38 ], these teams are meant to become part of the multi-disciplinary PHC team setup within the district health system. The health promotion, disease prevention, therapeutic, rehabilitative and palliative roles of the Ward Based Outreach Teams must be supported by health practitioners in PHC facilities and by environmental health officers in the community [ 39 ]. The teams are managed by professional or enrolled nurses who are additionally responsible for post-natal and community health worker-referred home visits to patients.

The second aspect of the reconfiguration of the health service platform was that each PHC cluster was to fall under the leadership and supervision of one cluster manager and management team and each PHC clinic or community health centre had to be managed by one operational manager. Smaller district hospitals within a specific district were to be reorganised as complexes managed by a chief executive officer with a standardised management team, including clinical, nursing service, administration and finance managers. The chief executive officers of the hospital complexes were to report to the chief directors responsible for the different districts.

The third aspect of the reconfiguration of the health service platform was that the District Clinical Specialist Teams had to assume a leadership role in clinical governance programmes in district hospitals in conjunction with the hospital clinical managers.

Step 3: Alteration

Kaplan et al. [ 20 p. 5] defines this step as follows: “Change the design of organizations, processes, or policies to enhance the results of the interplay and engage in a continuous improvement process that promotes learning at all levels.” The executive leadership decided that a skills audit needed to be conducted and to revisit and revise the FSDoH’s organogram. A decision was made to redeploy some managers to more suitable areas of operation and to revise their responsibilities. These changes were to be supported by compliance to the public service regulations of which the executive authority was the custodian. The intention was to ensure that the right people were placed in the right positions to enable them to improve their performance and to help the FSDoH deliver better public health service outcomes. The whole process of altering the previous ways of working was informed by the conceptualisation of the health systems building blocks and interlinking change mechanisms championed by executive functionaries as shown in Table 3 . It was also decided to revisit and amend the previous Strategic Transformation Plan of 2012–2030 on an annual basis to keep functionaries engaged in continuous service improvement on a sustainable basis using the HSGA intervention model.

The finalisation and refinement of the HSGA intervention model by end-2014 was a prelude to the development of the Strategic Transformation Plan 2015–2030 in January 2014. The model was to be used as a tool to integrate and implement the Plan’s programmes moving forward. Hence, the HSGA model was approved as an official policy for compliance, monitoring, and reporting in January 2016. The HSGA policy would guide the FSDoH’s approach in implementing the reconfigured service platform and improving healthcare service integration, governance and accountability. It was expected that the HSGA policy would ensure uniform understanding and application of the HSGA intervention model and performance measures of the Balanced Scorecard throughout the department’s services.

Step 4: Implementation

Kaplan et al. [ 20 p. 5] defines this step as follows: “Operationalize the integration of the new dynamics to facilitate the ways people, processes, facilities, equipment, and organizations all work together to achieve better care at lower cost.” The HSGA policy outlined the different implementation roles and responsibilities of the various managers, institutions, stakeholders and formations within the FSDoH and aligned all the annual performance plans, district health plans and the Strategic Transformation Plan 2015–2030 to the HSGA intervention model using the Balanced Scorecard as a performance management tool.

The incremental implementation of the HSGA intervention model which took place from February 2014, was to ensure sustainable implementation and compliance to policy and procedure and was based on normalisation process theory. The implementation process was also directed by the six WHO health systems building blocks that were translated into the seven departmental goals. A subsequent paper will assess the impact of the HSGA policy on the public health systems functioning from the viewpoint of health managers and governors based on Balanced Scorecard performance measurement results.

The HSGA intervention model was developed and formalised into policy in a quest to bind the employees and managers across the whole department to comply with implementation of the model in a sustainable manner and in line with the Strategic Transformation Plan 2015–2030. The model was designed with support and input from all the relevant stakeholders.

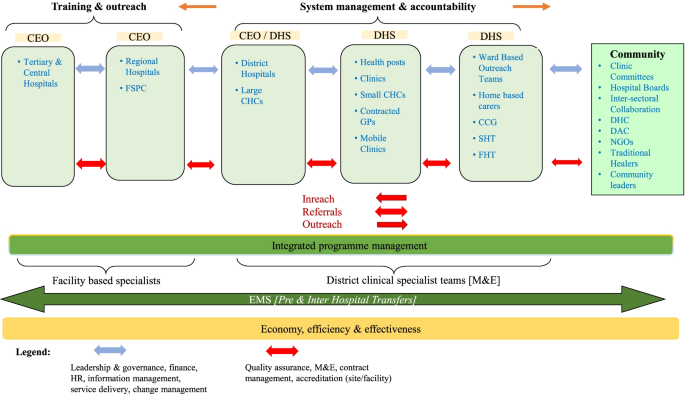

A process flow was conceptualised on how service delivery at the district level could be functionally integrated with the next levels of referral through a cascade termed Re-engineering of Admission (READ) to enable smooth referral of the patient from the community up to the tertiary level of care. Another process flow termed the Re-engineering of Discharge (RED) [ 40 ] was adopted to direct the safe referral and movement of the patient downwards through the system. These changes were reflected in a conceptual framework, the HSGA intervention model, illustrating the need for interventions to integrate the various levels of care within the reviewed policy positions and structural rearrangements (Fig. 3 ).

Health Systems Governance & Accountability intervention model

‘Inreach’ refers to deploying health professionals to a higher level facility for purposes of learning. ‘Outreach’ refers to deploying health professionals to a higher level facility for purposes of teaching. CCG community care giver, CEO chief executive officer, CHC community health centre, DAC District AIDS Council, DHC District Health Council, DHS district health system, EMS Emergency Medical Services, FHT Family Health Team, FIT Facility Improvement Team, FSPC Free State Psychiatric Complex, GP general practitioner, M&E monitoring and evaluation, NGO non-governmental organisation, SHT School Health Team

The HSGA intervention model emphasised the accountability of the system to the community and patients it served. It indicated how the different healthcare levels dovetailed into one integrated system to improve health system performance based on the six health system building blocks. It provided a framework for leadership, governance, and accountability throughout the whole health system, including community- and facility-based PHC, as well as district, provincial, tertiary, and central hospital services. All healthcare providers were required to comply with the approved referral and service protocols and to provide feedback to the referring facility clinician for further handling and down-referral for continuity of care.

In respect of the service delivery building block, the HSGA intervention model and policy also directed that all public healthcare facilities had to adhere to the norms and standards required by the Council for Health Service Accreditation of Southern Africa; healthcare services had to be provided in an integrated manner with good co-operation and communication between facilities and functionaries; patient movement up and down the health service value-chain had to be managed in line with procedural and clinical protocols; monitoring and evaluation functions had to be co-ordinated by the strategic planning and monitoring and evaluation unit at the corporate office; the District Clinical Specialist Teams had to conduct clinical oversight, clinical governance protocol audits and surveillance in district facilities; and the different levels of care had to be linked through a reciprocal transfer and referral system.

Regarding the leadership/governance building block, the HSGA intervention model and policy directed that leadership and managers had to ensure coordination and integration of governance efforts around a common mission to focus management teams’ activities on achieving optimum performance of the public health system; adopt a holistic view of the system’s operations to enable effective achievement of desired outcomes; comply with service integration imperatives and clinical governance protocols; and monitor obstacles with immediate intervention where necessary. Led by the district managers, the District Management Teams were responsible for governance at the PHC level, integration of service implementation, and compliance with policies and procedures. The District Management Teams were expected to collaborate with multiple internal and external stakeholders who play a role in disease control programme management. All the changes were streamlined in accordance with the building blocks and outlined in the draft Strategic Transformation Plan 2015–2030 [ 41 ].

Table 4 shows the changes in the configuration of the institutions per district, including the planned establishment of 32 health posts. A health post is a facility below the level of a clinic which is staffed by lower-category nurses allowing community members to collect their chronic medicines or receive care for minor ailments like wound care. Comprehensive PHC services provided by the Ward Based Outreach Teams in the households, health posts, mobile clinics and fixed PHC facilities were established for effective and efficient PHC re-engineering, thus bringing healthcare services closer to the people. The PHC facilities were re-organised into PHC clusters, each having a group of PHC clinics and a community health centre. Certain PHC clinics were upgraded to community health centres, and certain small hospitals downgraded to community health centres.

EMS are responsible for all transportation of patients, both in emergencies and planned patient referrals in FSDoH facilities. Patient routes had to be aligned with the changed referral paths and routes according to the reviewed departmental referral policy considering that the 60-seater buses were to be operated on long distances to Bloemfontein only. Bloemfontein is the capital of the province and is where most of the higher-level referral and specialist hospitals are located. The categories of patients referred to Bloemfontein was reviewed in line with the approved service packages and patient needs. The new routes improved the flow of patients to the nearest facilities with reduced transit times. Therefore, the operational costs of Emergency Medical Services were reduced as well.

To transform mental health service delivery by 2030, the service delivery system focused on the following aspects within an agreed upon timeframe. In line with the WHO (2003) recommendations [ 42 ] regarding organisation of mental health services, the mental health system was planned to include an array of settings and levels that included primary care, community-based settings, general hospitals, and specialised psychiatric hospitals. It was further planned that the Free State Psychiatric Complex would undertake outreach visits to regional hospitals and that the latter would in turn conduct outreach services to district hospitals and selected community health centres. Further outreach services would be provided to the Kimberley Hospital Complex in the Northern Cape province and Queen Mamohato Memorial Hospital in Lesotho.

This study describes the development the Health Systems Governance & Accountability (HSGA) intervention model by the FSDoH in collaboration with the community and other stakeholders following a participatory action approach. Researchers publish the processes they use to develop interventions to improve healthcare to help future developers to improve their approaches, plans and practices. Description of the development of interventions is important because it provides future developers with the terminology and language to identify, conceptualise and explain their rationales and more effectively plan and design context-specific intervention models [ 43 ]. It is important to understand how the models that end up being designed during interventions, complement the traditional ways of doing things for the betterment of a common good such as public health. A movement toward an assets-based approach to intervention design and implementation has started to take place in public health where intervention development processes emphasise activating and drawing on the strengths and skills of individuals, communities, and through the co-production of intervention programmes and research [ 44 ].

A systematic review of studies reporting intervention development showed that they mainly took a pragmatic self-selected approach, a theory- and evidence-based approach, or a partnership approach, e.g., community-based participatory research or co-design [ 45 ]. Both theory (systems) and provider/user approaches were utilised in the development of the HSGA model in the Free State. Systems theory and the WHO health systems building blocks framework helped the developers and participating stakeholders to conceptualise and plan a whole-system intervention, the HSGA intervention model and policy. The participatory approach allowed the developers to incorporate the experiences and ideas of frontline health systems users and providers and managers across all levels of the public health hierarchy. Obtaining both user and provider perspectives is crucial in efforts to model and design context-specific public health strengthening initiatives [ 46 , 47 , 48 ].

Previous studies to find ways to improve health outcomes through a consultative and iterative process involving users identified barriers such as weak and unorganised referral patterns and inadequate human resources as crucial [ 44 , 49 ]. The development of the ‘Better Health Outcomes through Mentoring and Assessment’ (BHOMA) intervention in Zambia was intended to specifically address such challenges [ 17 ]. Similar challenges were addressed in the development of the Free State HSGA model, but the focus was on improving integration and performance assessment as means to improve health outcomes. Both interventions were intended to provide the system-wide solutions to the challenges, rather than focusing on specific diseases. The influence that the users exerted could be thought of as a ‘user intervention’ because they would in turn support changes and improvements while constantly assessing whether they are appropriate or not. Von Hippel [ 44 ] and Altman et al. [ 50 ], reiterate that the context and support for this participatory approach to ‘user intervention’ leverages user innovation capability in influencing the manner of medicine practice or provision of health services, which is considered a novel approach in dispensing public health. Von Hippel explains that when faced with problems or challenges, the users of the products, services or beneficiaries of processes are often likely to develop solutions to their problems and sometimes offer innovative ways and new approaches and solutions to challenges facing them. Hence the essential aspects of the HSGA intervention model were premised on collective solution finding and co-creation of approaches. Users and communities therefore got to enjoy the benefits of the changes they themselves helped to bring about. That is why integration of inputs from users or beneficiaries into the development of innovative approaches or models should be considered as a way to leverage the strengths of communities served by health providers for efficient and effective interventions to be developed and new approaches to be generated to address the varied complexities of health service challenges they face [ 50 ].

In the development of the HSGA intervention model obtaining users and communities’ perspectives took the form of unannounced visits to hospitals and clinics and community meetings respectively. This worked well because during the unannounced visits and community meetings, different and diverse groups of patients and providers tended to congregate. They presented their respective views and suggestions on which processes need to be changed or improved for the service offering to improve. This was challenging to deal with because the views and recommendations of the respective users, communities and frontline health staff were often diverse and needed to be deciphered, understood by all parties, and reconciled.

In the development of the HSGA intervention model obtaining managers and providers’ perspectives took the form of learning from and incorporating their views and suggestions presented during routine management meetings, as well as engagements during routine performance assessments. This was advantageous because challenges and proposed solutions presented by the managers and providers could then be directly discussed and addressed. Defects in the referral processes and clinical procedures were identified and reviewed for translation into corrective policy positions. This was challenging because procedures and processes often had to be reviewed ‘on-the-go’ and drafters were to affect the changes on the existing process and procedure documents forthwith, for later implementation.

In the development of the HSGA intervention model obtaining other stakeholders and experts’ perspectives took the form, amongst others, of a health indaba . This was beneficial because various stakeholders at the indaba raised their views, some of which corroborated the issues earlier raised by users and communities, as well as during the initial situation appraisal. It was sometimes difficult to differentiate personal experiences from health system shortcomings relating to process or procedure defects or challenges. Nevertheless, the recommendations made were considered in the overall revisions of processes and procedures.

Using systems theory to understand organisational performance helps intervention developers to obtain a broader perspective that enables recognition of patterns, cycles and overall structures, rather than focus on specific events or aspects of the system [ 51 , 52 ]. While functional integration of health services may be an attainable vision [ 53 ], certain important intersecting health system capabilities are required to bring about frontline service integration as well. These include fully functional frontline health services, adequately trained and motivated healthcare workers, availability of suitable technology, and devolving authority and decision-making processes to lower cadres of frontline managers and staff to adapt integration processes to local circumstances [ 54 ]. Therefore, during the development of the HSGA model, Kaplan’s theory influenced the assessment of how the health system was organised, as well as the identification of the various service interlinkages and interdependencies of the multiple elements (building blocks) involved in public health systems strengthening and performance. The various interlinkages and process dependencies were clearly described, broadly understood and reconfigurations entrenched through policy changes to ensure continuous improvement of the Free State public health system’s performance.

The WHO considers systems thinking as an essential ingredient in opening pathways to identification and resolution of health system challenges [ 55 , 56 ]. The use of the WHO building blocks approach [ 2 , 15 ] to guide the integration process of the HSGA intervention model, placed emphasis on the interactions and interdependencies to guide the management of transitions among and between the demand side (community) and the supply side (healthcare facilities and staff).

The Zambian BHOMA study [ 17 ] proposed a framework to evaluate a complex health system intervention applying systems thinking concepts. It formed the basis for intervention development using systems thinking, where emphasis was placed on understanding the complete system and how the various parts interacted with each other to create a functional whole as opposed to the individual parts that made up the system [ 57 ]. In the development of the HSGA model in the Free State, system theory and the WHO building blocks framework were used to as a ‘template’ to assess the effectiveness and operational efficiencies of various components or divisions within the health services platform. This approach was appropriate because we could discern areas of weakness and how they could be addressed.

The HSGA intervention model was directed at three levels of care, i.e. (i) the community and sub-district levels of care; (ii) the district and regional level of care and (iii) the provincial level of care. At the community and sub-district level, care was to be delivered by Ward Based Outreach Teams and community health workers; at the district or regional level, by local PHC clinics, community health centres and district and regional hospitals; and at the provincial level, by provincial hospitals and the central hospital. Within and between these levels, transitions in the form of READ and RED [ 40 ] were intended to be managed efficiently and effectively in an integrated manner to mitigate morbidity and mortality. Austin et al. [ 49 ] acknowledged that the movement of a patient from the home or community setting into the health system during admissions into a healthcare facility or hospital and vice versa, constitutes transitions to avoid the effects of care-risk factors that can lead to morbidities, excess stays and even re-admissions if those transitions are ineffective and inefficient. In the Free State, the READ and RED transitions were conceptualised and applied to improve referral up and down the referral hierarchy. The effectiveness and efficiency of these transitions were based on the strength of the referral system which the HSGA intervention model sought to integrate and improve. Austin et al. [ 49 ] pointed out that both the system and patient factors exert influence on the transitions and the capacity to address complex barriers to safe admission and discharge procedures and workflows. The development of approaches like the HSGA intervention model to address and improve complex transitions effectively and efficiently require continued testing and assessment of their effectiveness in view of the complexity of the transitions.

Austin et al. [ 49 ] corroborate the importance of iterative, internally driven intervention, monitoring, and wide dissemination during the implementation process as was applied in the Free State and will be reported in another paper. In the current study monitoring or evaluation was conducted using Kaplan and Norton’s (1992) Balanced Scorecard performance measurement tool [ 4 ]. This decision was based on its successful application in healthcare settings and organisations elsewhere [ 31 , 32 , 33 ]. Our experience aligns with that of Oliveira et al. [ 31 ] that the Balanced Scorecard is a valuable management tool to enhance flexibility, collaboration, innovation and adaptation that contribute to improve healthcare integration and outcomes.

A limitation of this descriptive study is that it is first authored by the former executive leader of the FSDoH, and an element of bias is thus inevitable. However, inclusion of authors who are not employees of the department helped to mitigate this bias. A strength of the current study is that the health system as a whole, and not just disparate elements within it, were considered in the development of the HSGA intervention model. The study provides useful insight on practical issues to consider during the development of public health interventions geared towards health systems strengthening and moves away from the traditional practice of addressing only individual behaviour change. Furthermore, this study attempts to provide a systematic approach to health systems intervention development with community and stakeholder involvement and aligns with Wight et al.’s [ 3 ] and Kaplan et al.’s [ 20 ] recommendation that a systematic approach to intervention development, as well as rigorous evaluation, are required. Another strength of the HSGA intervention model is that it was developed during normal service delivery processes and mostly during routine management planning meetings and discussions.

Public health practice should be evidence-based and grounded in theory and systems thinking. The WHO’s health system building blocks framework is a useful guide to conceptualise and assess the status of a health system and its performance and is a valuable tool to align or configure services according to communities’ actual realities and needs. Based on the building blocks concept, the HSGA intervention model was developed by the provincial health department during routine service delivery conditions to bring about desired reforms where gaps and inefficiencies had previously been identified. Reconfiguration of the service platform provided an enabling framework for future efforts to enhance integration, improve service delivery and improve the public health system’s performance. Thus, the development of the HSGA intervention model and its formalisation into an official policy provided an opportunity to improve healthcare service integration, health system performance, and improve health outcomes in the Free State public health sector. The study contributes to the body of knowledge on health systems strengthening and illustrates how to draw on both theory and participatory approaches to develop an intelligible intervention to improve public health system integration and performance.

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated during the documentary review and therefore no data sharing is applicable to this article.

Abbreviations

Better Health Outcomes through Mentoring and Assessment

Free State Department of Health

Health Systems Governance & Accountability

National Department of Health

Primary health care

Re-engineering of Admission

Re-engineering of Discharge

World Health Organization

Malakoane B, Heunis JC, Chikobvu P, Kigozi NG, Kruger WH. Public health system challenges in the Free State, South Africa: a situational appraisal to inform health systems strengthening. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:58.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

World Health Organization. Everybody business: strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes. WHO’s framework. Geneva: WHO; 2007.

Google Scholar

Wight D, Wimbush E, Jepson R, Doi L. Six steps in quality intervention development (6SQuID). J Epidemiol Community Health. 2020;70:520–5.

Article Google Scholar

Kaplan RS, Norton DP. The Balanced Scorecard - measures that drive performance. Harv Bus Rev. 1992;70(71):9.

Ross J, Stevenson F, Dack C, Pal K, May C, Michie S, et al. Developing an implementation strategy for a digital health intervention: an example in routine healthcare. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:794.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Free State Department of Health. Free State Department of Health Annual Report 2014/2015. Bloemfontein: FSDoH; 2015.

Armitage GD, Suter E, Oelke ND, Adair CE. Health systems integration: state of the evidence. Int J Integr Care. 2009;9:e82.

World Health Organization. The world health report 2005: make every mother and child count. Geneva: WHO; 2005.

Book Google Scholar

Heyeres M, McCalman J, Tsey K, Kinchin I. The complexity of health service integration: a review of reviews. Public Health Front. 2016;4:233.

World Health Organization, United Nations Children’s Fund. A vision for primary health care in the 21st century: towards universal health coverage and the Sustainable Development Goals. Geneva: WHO; 2018.

Heunis C, Schneider H. Integration of ART: concepts, policy and practice. Acta Academica Supplementum. 2006;2006(Suppl 1):256–85.

van Rensburg HCJ, Engelbrecht MC. Transformation of the South African health system: post-1994. In: van Rensburg HCJ, editor. Heath and heath care in South Africa. 2nd ed. Pretoria: Van Schaik Pubishers; 2012. p. 121–88.

Heunis JC, Wouters E, Kigozi NG. HIV, AIDS and tuberculosis in South Africa: trends, challenges and responses. In: van Rensburg HCJ, editor. Health and health care in South Africa. 2nd ed. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers; 2012. p. 293–360.

McIntyre D, Klugman B. The human face of decentralisation and integration of health services: experience from South Africa. Reprod Health Matters. 2003;11(21):108–19.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

World Health Organization. Monitoring the building blocks of health systems: a handbook of indicators and their measurement strategies. Geneva: WHO; 2010.

Manyazewal T. Using the World Health Organization health system building blocks through survey of healthcare professionals to determine the performance of public healthcare facilities. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:50.

Mutale W, Bond V, Mwanamwenge MT, Mlewa S, Balabanova D, Spicer N, et al. Systems thinking in practice: the current status of the six WHO building blocks for health system strengthening in three BHOMA intervention districts of Zambia: a baseline qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:291.

Morris LD, Grimmer KA, Twizeyemariya A, Coetzee M, Leibbrandt MC, Louw QA. Health system challenges affecting rehabilitation services in South Africa. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;43(6):877–83.

Mounier-Jack S, Griffiths UK, Closser S, Burchett H, Marchal B. Measuring the health systems impact of disease control programmes: a critical reflection on the WHO building blocks framework. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:278.

Kaplan G, Griffiths UK, Closser S, Burchett H, Marchal B. Bringing a systems approach to health. Discussion paper. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine and National Academy of Engineering; 2013.

Khan S, Vandermorris A, Shepherd J, Begun JW, Jordan Lanham H, Uhl-Bien M, et al. Embracing uncertainty, managing complexity: applying complexity thinking principles to transformation efforts in healthcare systems. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:192.

Statistics South Africa. Mid-year population estimates 2020. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa; 2020.

Day C, Gray A. Health and related indicators. In: Padarath A, English R, editors. South African Health Review 2012/13. Durban: Health Systems Trust; 2013. p. 207–322.

Oboirien K, Harris B, Goudge J, Eyles J. Implementation of district-based clinical specialist teams in South Africa: Analysing a new role in a transforming system. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:600.

Cusack C, Cohen B, Mignone J, Chartier MJ, Lutfiyya Z. Participatory action as a research method with public health nurses. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74(7):1544–53.

Cordeiro L, Soares CB. Action research in the healthcare field: a scoping review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2018;16(4):1003–47.

Kushniruk A, Nøhr C. Participatory design, user involvement and health IT evaluation. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2016;222:139–51.

PubMed Google Scholar

DeSmet A, Thompson D, Baranowski T, Palmeira A, Verloigne M, De Bourdeaudhuij I. Is participatory design associated with the effectiveness of serious digital games for healthy lifestyle promotion? A meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(4):e94.

Tiruneh GT, Zemichael NF, Betemariam WA, Karim AM. Effectiveness of participatory community solutions strategy on improving household and provider health care behaviors and practices: A mixed-method evaluation. PLoS One. 2020;15(2):e0228137.

Pringle J, Doi L, Jindal-Snape D, Jepson R, McAteer J. Adolescents and health-related behaviour: using a framework to develop interventions to support positive behaviours. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2018;4:69.

Oliveira HC, Rodrigues LL, Craig R. Bureaucracy and the balanced scorecard in health care settings. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2020;33(3):247–59.

Al-Kaabi SK, Chehab MA, Selim N. The balanced scorecard as a performance management tool in the healthcare sector – the case of the Medical Commission Department at the Ministry of Public Health, Qatar. Cereus. 2019;11(7):e5262.

Bisbe J, Barrubés J. The Balanced Scorecard as a management tool for assessing and monitoring strategy implementation in health care organizations. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2012;65(10):919–27.

Free State Department of Health. Strategic Transformation Plan 2015/2030: FSDoH. Bloemfontein: FSDoH; 2015.

Free State Department of Health. Policy on the Implementation of the Health Systems Governance and Accountability (HSGA) Model. Bloemfontein: FSDoH; 2015.

Mojaki ME, Letskokgohka ME, Govender M. Referral steps in district health system side-stepped. S Afr Med J. 2011;101(2):109.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

National Department of Health. Referral Policy for South African Health Services and Referral Implementation Guidelines. Pretoria: NDoH; 2020.

National Department of Health. Provincial guidelines for the implementation of the three streams of primary health care re-engineering. Pretoria: NDoH; 2011.

National Department of Health. Policy Framework and Strategy for Ward-based Primary Healthcare Outreach Teams 2018/19 - 2023/24. Pretoria: NDoH; 2018.

Adams C, Stephens K, Whiteman K, Kersteen H, Katruska J. Implementation of the Re-Engineered Discharge (RED) Toolkit to decrease all-cause readmission rates at a rural community hospital. Qual Manag Health Care. 2014;23(3):169–77.

Free State Department of Health. Strategic Transformation Plan 2015–2030: Free State Department of Health. Bloemfontein: FSDoH; 2015.

World Health Organization. Mental Health Policy and Service Guidance Package. Geneva: WHO; 2003.

Glavin K, Schaffer MA, Kvarme LG. The Public Health Intervention Wheel in Norway. Public Health Nurs. 2019;36(6):819–28.

Von Hippel C. A next generation assets-based public health intervention development model: The public as innovators. Front Public Health. 2018;6:248.

Croot l, O’Cathain A, Sworn K, Yardley L, Turner K, Duncan E, et al. Developing interventions to improve health: a systematic mapping review of international practice between 2015 and 2016. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2019;5:127.

Ameh S, Klipstein-Grobusch K, D’ambruoso L, Kahn K, Tollman SM, Gomez-Olive FX. Quality of integrated chronic disease care in rural South Africa: user and provider perspectives. Health Policy Plan. 2017;32:257–66.

Phiri SN, Fylkesnes K, Ruano YL, Moland KM. ‘Born before arrival’: user and provider perspectives on health facility childbirths in Kapiri Mposhi district. Zambia BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:323.

Poremski D, Harris DW, Kahan D, Pauly D, Leszcz M, O’Campo P, et al. Improving continuity of care for frequent users of emergency departments: service user and provider perspectives. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016;40:55–9.

Austin EJ, Neukirch J, Ong TD, Simpson L, Berger GN, Keller CS, et al. Development and implementation of a complex health system intervention targeting transitions of care from hospital to post-acute care. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(2):358–65.

Altman M, Huang TTK, Breland JY. Design thinking in health care. Prev Chronic Dis. 2018;15:180128.

Checkland P. Systems thinking, systems practice. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1981.

Atun R, Manade N. Health systems and systems thinking. Maidenhead, Berkshire: Open University Press; 2006.

Schneider S. Functional integration of health services. Aust J Rural Health. 2004;12:36–7.

Topp SM, Abimbola S, Joshi R, Negin J. How to assess and prepare health systems in low- and middle-income countries for integration of services - a systematic review. Health Policy Plan. 2018;33:298–312.

de Savigny D, Adam T, editors. Systems thinking for health systems strengthening. Geneva: Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research; 2009.

Paina L, Peters DH. Understanding pathways for scaling up health services through the lens of complex adaptive systems. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27:365–73.

Von Bertalanffy L. General system theory: foundations, development, applications. New York: Braziller; 1976.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the participation of the FSDoH executive, divisional and programme managers and their support teams, as well as frontline healthcare workers, community representatives, community members, clinic committee and hospital board members and patients for their participation in the development of the HSGA intervention model and process reviews.

All non-routine expenses were paid for by BM.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Community Health, University of the Free State, PO Box 339, Bloemfontein, 9300, South Africa

Benjamin Malakoane & Willem Hendrik Kruger

Centre for Health Systems Research & Development, University of the Free State, PO Box 339, Bloemfontein, 9300, South Africa

James Christoffel Heunis & Nanteza Gladys Kigozi

Department of Community Health, Free State Department of Health, University of the Free State, PO Box 277, Bloemfontein, 9300, South Africa

Perpetual Chikobvu

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions