- Publications

- Conferences & Events

- Professional Learning

- Science Standards

- Awards & Competitions

- Instructional Materials

- Free Resources

- American Rescue Plan

- For Preservice Teachers

NCCSTS Case Collection

- Partner Jobs in Education

- Interactive eBooks+

- Digital Catalog

- Regional Product Representatives

- e-Newsletters

- Bestselling Books

- Latest Books

- Popular Book Series

- Prospective Authors

- Web Seminars

- Exhibits & Sponsorship

- Conference Reviewers

- National Conference • Denver 24

- Leaders Institute 2024

- National Conference • New Orleans 24

- Submit a Proposal

- Latest Resources

- Professional Learning Units & Courses

- For Districts

- Online Course Providers

- Schools & Districts

- College Professors & Students

- The Standards

- Teachers and Admin

- eCYBERMISSION

- Toshiba/NSTA ExploraVision

- Junior Science & Humanities Symposium

- Teaching Awards

- Climate Change

- Earth & Space Science

- New Science Teachers

- Early Childhood

- Middle School

- High School

- Postsecondary

- Informal Education

- Journal Articles

- Lesson Plans

- e-newsletters

- Science & Children

- Science Scope

- The Science Teacher

- Journal of College Sci. Teaching

- Connected Science Learning

- NSTA Reports

- Next-Gen Navigator

- Science Update

- Teacher Tip Tuesday

- Trans. Sci. Learning

MyNSTA Community

- My Collections

Case Study Listserv

Permissions & Guidelines

Submit a Case Study

Resources & Publications

Enrich your students’ educational experience with case-based teaching

The NCCSTS Case Collection, created and curated by the National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science, on behalf of the University at Buffalo, contains over a thousand peer-reviewed case studies on a variety of topics in all areas of science.

Cases (only) are freely accessible; subscription is required for access to teaching notes and answer keys.

Subscribe Today

Browse Case Studies

Latest Case Studies

Development of the NCCSTS Case Collection was originally funded by major grants to the University at Buffalo from the National Science Foundation , The Pew Charitable Trusts , and the U.S. Department of Education .

Center for Teaching

Case studies.

Print Version

Case studies are stories that are used as a teaching tool to show the application of a theory or concept to real situations. Dependent on the goal they are meant to fulfill, cases can be fact-driven and deductive where there is a correct answer, or they can be context driven where multiple solutions are possible. Various disciplines have employed case studies, including humanities, social sciences, sciences, engineering, law, business, and medicine. Good cases generally have the following features: they tell a good story, are recent, include dialogue, create empathy with the main characters, are relevant to the reader, serve a teaching function, require a dilemma to be solved, and have generality.

Instructors can create their own cases or can find cases that already exist. The following are some things to keep in mind when creating a case:

- What do you want students to learn from the discussion of the case?

- What do they already know that applies to the case?

- What are the issues that may be raised in discussion?

- How will the case and discussion be introduced?

- What preparation is expected of students? (Do they need to read the case ahead of time? Do research? Write anything?)

- What directions do you need to provide students regarding what they are supposed to do and accomplish?

- Do you need to divide students into groups or will they discuss as the whole class?

- Are you going to use role-playing or facilitators or record keepers? If so, how?

- What are the opening questions?

- How much time is needed for students to discuss the case?

- What concepts are to be applied/extracted during the discussion?

- How will you evaluate students?

To find other cases that already exist, try the following websites:

- The National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science , University of Buffalo. SUNY-Buffalo maintains this set of links to other case studies on the web in disciplines ranging from engineering and ethics to sociology and business

- A Journal of Teaching Cases in Public Administration and Public Policy , University of Washington

For more information:

- World Association for Case Method Research and Application

Book Review : Teaching and the Case Method , 3rd ed., vols. 1 and 2, by Louis Barnes, C. Roland (Chris) Christensen, and Abby Hansen. Harvard Business School Press, 1994; 333 pp. (vol 1), 412 pp. (vol 2).

Teaching Guides

- Online Course Development Resources

- Principles & Frameworks

- Pedagogies & Strategies

- Reflecting & Assessing

- Challenges & Opportunities

- Populations & Contexts

Quick Links

- Services for Departments and Schools

- Examples of Online Instructional Modules

- Our Mission

Making Learning Relevant With Case Studies

The open-ended problems presented in case studies give students work that feels connected to their lives.

To prepare students for jobs that haven’t been created yet, we need to teach them how to be great problem solvers so that they’ll be ready for anything. One way to do this is by teaching content and skills using real-world case studies, a learning model that’s focused on reflection during the problem-solving process. It’s similar to project-based learning, but PBL is more focused on students creating a product.

Case studies have been used for years by businesses, law and medical schools, physicians on rounds, and artists critiquing work. Like other forms of problem-based learning, case studies can be accessible for every age group, both in one subject and in interdisciplinary work.

You can get started with case studies by tackling relatable questions like these with your students:

- How can we limit food waste in the cafeteria?

- How can we get our school to recycle and compost waste? (Or, if you want to be more complex, how can our school reduce its carbon footprint?)

- How can we improve school attendance?

- How can we reduce the number of people who get sick at school during cold and flu season?

Addressing questions like these leads students to identify topics they need to learn more about. In researching the first question, for example, students may see that they need to research food chains and nutrition. Students often ask, reasonably, why they need to learn something, or when they’ll use their knowledge in the future. Learning is most successful for students when the content and skills they’re studying are relevant, and case studies offer one way to create that sense of relevance.

Teaching With Case Studies

Ultimately, a case study is simply an interesting problem with many correct answers. What does case study work look like in classrooms? Teachers generally start by having students read the case or watch a video that summarizes the case. Students then work in small groups or individually to solve the case study. Teachers set milestones defining what students should accomplish to help them manage their time.

During the case study learning process, student assessment of learning should be focused on reflection. Arthur L. Costa and Bena Kallick’s Learning and Leading With Habits of Mind gives several examples of what this reflection can look like in a classroom:

Journaling: At the end of each work period, have students write an entry summarizing what they worked on, what worked well, what didn’t, and why. Sentence starters and clear rubrics or guidelines will help students be successful. At the end of a case study project, as Costa and Kallick write, it’s helpful to have students “select significant learnings, envision how they could apply these learnings to future situations, and commit to an action plan to consciously modify their behaviors.”

Interviews: While working on a case study, students can interview each other about their progress and learning. Teachers can interview students individually or in small groups to assess their learning process and their progress.

Student discussion: Discussions can be unstructured—students can talk about what they worked on that day in a think-pair-share or as a full class—or structured, using Socratic seminars or fishbowl discussions. If your class is tackling a case study in small groups, create a second set of small groups with a representative from each of the case study groups so that the groups can share their learning.

4 Tips for Setting Up a Case Study

1. Identify a problem to investigate: This should be something accessible and relevant to students’ lives. The problem should also be challenging and complex enough to yield multiple solutions with many layers.

2. Give context: Think of this step as a movie preview or book summary. Hook the learners to help them understand just enough about the problem to want to learn more.

3. Have a clear rubric: Giving structure to your definition of quality group work and products will lead to stronger end products. You may be able to have your learners help build these definitions.

4. Provide structures for presenting solutions: The amount of scaffolding you build in depends on your students’ skill level and development. A case study product can be something like several pieces of evidence of students collaborating to solve the case study, and ultimately presenting their solution with a detailed slide deck or an essay—you can scaffold this by providing specified headings for the sections of the essay.

Problem-Based Teaching Resources

There are many high-quality, peer-reviewed resources that are open source and easily accessible online.

- The National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science at the University at Buffalo built an online collection of more than 800 cases that cover topics ranging from biochemistry to economics. There are resources for middle and high school students.

- Models of Excellence , a project maintained by EL Education and the Harvard Graduate School of Education, has examples of great problem- and project-based tasks—and corresponding exemplary student work—for grades pre-K to 12.

- The Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning at Purdue University is an open-source journal that publishes examples of problem-based learning in K–12 and post-secondary classrooms.

- The Tech Edvocate has a list of websites and tools related to problem-based learning.

In their book Problems as Possibilities , Linda Torp and Sara Sage write that at the elementary school level, students particularly appreciate how they feel that they are taken seriously when solving case studies. At the middle school level, “researchers stress the importance of relating middle school curriculum to issues of student concern and interest.” And high schoolers, they write, find the case study method “beneficial in preparing them for their future.”

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

A case study research paper examines a person, place, event, condition, phenomenon, or other type of subject of analysis in order to extrapolate key themes and results that help predict future trends, illuminate previously hidden issues that can be applied to practice, and/or provide a means for understanding an important research problem with greater clarity. A case study research paper usually examines a single subject of analysis, but case study papers can also be designed as a comparative investigation that shows relationships between two or more subjects. The methods used to study a case can rest within a quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-method investigative paradigm.

Case Studies. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010 ; “What is a Case Study?” In Swanborn, Peter G. Case Study Research: What, Why and How? London: SAGE, 2010.

How to Approach Writing a Case Study Research Paper

General information about how to choose a topic to investigate can be found under the " Choosing a Research Problem " tab in the Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper writing guide. Review this page because it may help you identify a subject of analysis that can be investigated using a case study design.

However, identifying a case to investigate involves more than choosing the research problem . A case study encompasses a problem contextualized around the application of in-depth analysis, interpretation, and discussion, often resulting in specific recommendations for action or for improving existing conditions. As Seawright and Gerring note, practical considerations such as time and access to information can influence case selection, but these issues should not be the sole factors used in describing the methodological justification for identifying a particular case to study. Given this, selecting a case includes considering the following:

- The case represents an unusual or atypical example of a research problem that requires more in-depth analysis? Cases often represent a topic that rests on the fringes of prior investigations because the case may provide new ways of understanding the research problem. For example, if the research problem is to identify strategies to improve policies that support girl's access to secondary education in predominantly Muslim nations, you could consider using Azerbaijan as a case study rather than selecting a more obvious nation in the Middle East. Doing so may reveal important new insights into recommending how governments in other predominantly Muslim nations can formulate policies that support improved access to education for girls.

- The case provides important insight or illuminate a previously hidden problem? In-depth analysis of a case can be based on the hypothesis that the case study will reveal trends or issues that have not been exposed in prior research or will reveal new and important implications for practice. For example, anecdotal evidence may suggest drug use among homeless veterans is related to their patterns of travel throughout the day. Assuming prior studies have not looked at individual travel choices as a way to study access to illicit drug use, a case study that observes a homeless veteran could reveal how issues of personal mobility choices facilitate regular access to illicit drugs. Note that it is important to conduct a thorough literature review to ensure that your assumption about the need to reveal new insights or previously hidden problems is valid and evidence-based.

- The case challenges and offers a counter-point to prevailing assumptions? Over time, research on any given topic can fall into a trap of developing assumptions based on outdated studies that are still applied to new or changing conditions or the idea that something should simply be accepted as "common sense," even though the issue has not been thoroughly tested in current practice. A case study analysis may offer an opportunity to gather evidence that challenges prevailing assumptions about a research problem and provide a new set of recommendations applied to practice that have not been tested previously. For example, perhaps there has been a long practice among scholars to apply a particular theory in explaining the relationship between two subjects of analysis. Your case could challenge this assumption by applying an innovative theoretical framework [perhaps borrowed from another discipline] to explore whether this approach offers new ways of understanding the research problem. Taking a contrarian stance is one of the most important ways that new knowledge and understanding develops from existing literature.

- The case provides an opportunity to pursue action leading to the resolution of a problem? Another way to think about choosing a case to study is to consider how the results from investigating a particular case may result in findings that reveal ways in which to resolve an existing or emerging problem. For example, studying the case of an unforeseen incident, such as a fatal accident at a railroad crossing, can reveal hidden issues that could be applied to preventative measures that contribute to reducing the chance of accidents in the future. In this example, a case study investigating the accident could lead to a better understanding of where to strategically locate additional signals at other railroad crossings so as to better warn drivers of an approaching train, particularly when visibility is hindered by heavy rain, fog, or at night.

- The case offers a new direction in future research? A case study can be used as a tool for an exploratory investigation that highlights the need for further research about the problem. A case can be used when there are few studies that help predict an outcome or that establish a clear understanding about how best to proceed in addressing a problem. For example, after conducting a thorough literature review [very important!], you discover that little research exists showing the ways in which women contribute to promoting water conservation in rural communities of east central Africa. A case study of how women contribute to saving water in a rural village of Uganda can lay the foundation for understanding the need for more thorough research that documents how women in their roles as cooks and family caregivers think about water as a valuable resource within their community. This example of a case study could also point to the need for scholars to build new theoretical frameworks around the topic [e.g., applying feminist theories of work and family to the issue of water conservation].

Eisenhardt, Kathleen M. “Building Theories from Case Study Research.” Academy of Management Review 14 (October 1989): 532-550; Emmel, Nick. Sampling and Choosing Cases in Qualitative Research: A Realist Approach . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2013; Gerring, John. “What Is a Case Study and What Is It Good for?” American Political Science Review 98 (May 2004): 341-354; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010; Seawright, Jason and John Gerring. "Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research." Political Research Quarterly 61 (June 2008): 294-308.

Structure and Writing Style

The purpose of a paper in the social sciences designed around a case study is to thoroughly investigate a subject of analysis in order to reveal a new understanding about the research problem and, in so doing, contributing new knowledge to what is already known from previous studies. In applied social sciences disciplines [e.g., education, social work, public administration, etc.], case studies may also be used to reveal best practices, highlight key programs, or investigate interesting aspects of professional work.

In general, the structure of a case study research paper is not all that different from a standard college-level research paper. However, there are subtle differences you should be aware of. Here are the key elements to organizing and writing a case study research paper.

I. Introduction

As with any research paper, your introduction should serve as a roadmap for your readers to ascertain the scope and purpose of your study . The introduction to a case study research paper, however, should not only describe the research problem and its significance, but you should also succinctly describe why the case is being used and how it relates to addressing the problem. The two elements should be linked. With this in mind, a good introduction answers these four questions:

- What is being studied? Describe the research problem and describe the subject of analysis [the case] you have chosen to address the problem. Explain how they are linked and what elements of the case will help to expand knowledge and understanding about the problem.

- Why is this topic important to investigate? Describe the significance of the research problem and state why a case study design and the subject of analysis that the paper is designed around is appropriate in addressing the problem.

- What did we know about this topic before I did this study? Provide background that helps lead the reader into the more in-depth literature review to follow. If applicable, summarize prior case study research applied to the research problem and why it fails to adequately address the problem. Describe why your case will be useful. If no prior case studies have been used to address the research problem, explain why you have selected this subject of analysis.

- How will this study advance new knowledge or new ways of understanding? Explain why your case study will be suitable in helping to expand knowledge and understanding about the research problem.

Each of these questions should be addressed in no more than a few paragraphs. Exceptions to this can be when you are addressing a complex research problem or subject of analysis that requires more in-depth background information.

II. Literature Review

The literature review for a case study research paper is generally structured the same as it is for any college-level research paper. The difference, however, is that the literature review is focused on providing background information and enabling historical interpretation of the subject of analysis in relation to the research problem the case is intended to address . This includes synthesizing studies that help to:

- Place relevant works in the context of their contribution to understanding the case study being investigated . This would involve summarizing studies that have used a similar subject of analysis to investigate the research problem. If there is literature using the same or a very similar case to study, you need to explain why duplicating past research is important [e.g., conditions have changed; prior studies were conducted long ago, etc.].

- Describe the relationship each work has to the others under consideration that informs the reader why this case is applicable . Your literature review should include a description of any works that support using the case to investigate the research problem and the underlying research questions.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research using the case study . If applicable, review any research that has examined the research problem using a different research design. Explain how your use of a case study design may reveal new knowledge or a new perspective or that can redirect research in an important new direction.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies . This refers to synthesizing any literature that points to unresolved issues of concern about the research problem and describing how the subject of analysis that forms the case study can help resolve these existing contradictions.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research . Your review should examine any literature that lays a foundation for understanding why your case study design and the subject of analysis around which you have designed your study may reveal a new way of approaching the research problem or offer a perspective that points to the need for additional research.

- Expose any gaps that exist in the literature that the case study could help to fill . Summarize any literature that not only shows how your subject of analysis contributes to understanding the research problem, but how your case contributes to a new way of understanding the problem that prior research has failed to do.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important!] . Collectively, your literature review should always place your case study within the larger domain of prior research about the problem. The overarching purpose of reviewing pertinent literature in a case study paper is to demonstrate that you have thoroughly identified and synthesized prior studies in relation to explaining the relevance of the case in addressing the research problem.

III. Method

In this section, you explain why you selected a particular case [i.e., subject of analysis] and the strategy you used to identify and ultimately decide that your case was appropriate in addressing the research problem. The way you describe the methods used varies depending on the type of subject of analysis that constitutes your case study.

If your subject of analysis is an incident or event . In the social and behavioral sciences, the event or incident that represents the case to be studied is usually bounded by time and place, with a clear beginning and end and with an identifiable location or position relative to its surroundings. The subject of analysis can be a rare or critical event or it can focus on a typical or regular event. The purpose of studying a rare event is to illuminate new ways of thinking about the broader research problem or to test a hypothesis. Critical incident case studies must describe the method by which you identified the event and explain the process by which you determined the validity of this case to inform broader perspectives about the research problem or to reveal new findings. However, the event does not have to be a rare or uniquely significant to support new thinking about the research problem or to challenge an existing hypothesis. For example, Walo, Bull, and Breen conducted a case study to identify and evaluate the direct and indirect economic benefits and costs of a local sports event in the City of Lismore, New South Wales, Australia. The purpose of their study was to provide new insights from measuring the impact of a typical local sports event that prior studies could not measure well because they focused on large "mega-events." Whether the event is rare or not, the methods section should include an explanation of the following characteristics of the event: a) when did it take place; b) what were the underlying circumstances leading to the event; and, c) what were the consequences of the event in relation to the research problem.

If your subject of analysis is a person. Explain why you selected this particular individual to be studied and describe what experiences they have had that provide an opportunity to advance new understandings about the research problem. Mention any background about this person which might help the reader understand the significance of their experiences that make them worthy of study. This includes describing the relationships this person has had with other people, institutions, and/or events that support using them as the subject for a case study research paper. It is particularly important to differentiate the person as the subject of analysis from others and to succinctly explain how the person relates to examining the research problem [e.g., why is one politician in a particular local election used to show an increase in voter turnout from any other candidate running in the election]. Note that these issues apply to a specific group of people used as a case study unit of analysis [e.g., a classroom of students].

If your subject of analysis is a place. In general, a case study that investigates a place suggests a subject of analysis that is unique or special in some way and that this uniqueness can be used to build new understanding or knowledge about the research problem. A case study of a place must not only describe its various attributes relevant to the research problem [e.g., physical, social, historical, cultural, economic, political], but you must state the method by which you determined that this place will illuminate new understandings about the research problem. It is also important to articulate why a particular place as the case for study is being used if similar places also exist [i.e., if you are studying patterns of homeless encampments of veterans in open spaces, explain why you are studying Echo Park in Los Angeles rather than Griffith Park?]. If applicable, describe what type of human activity involving this place makes it a good choice to study [e.g., prior research suggests Echo Park has more homeless veterans].

If your subject of analysis is a phenomenon. A phenomenon refers to a fact, occurrence, or circumstance that can be studied or observed but with the cause or explanation to be in question. In this sense, a phenomenon that forms your subject of analysis can encompass anything that can be observed or presumed to exist but is not fully understood. In the social and behavioral sciences, the case usually focuses on human interaction within a complex physical, social, economic, cultural, or political system. For example, the phenomenon could be the observation that many vehicles used by ISIS fighters are small trucks with English language advertisements on them. The research problem could be that ISIS fighters are difficult to combat because they are highly mobile. The research questions could be how and by what means are these vehicles used by ISIS being supplied to the militants and how might supply lines to these vehicles be cut off? How might knowing the suppliers of these trucks reveal larger networks of collaborators and financial support? A case study of a phenomenon most often encompasses an in-depth analysis of a cause and effect that is grounded in an interactive relationship between people and their environment in some way.

NOTE: The choice of the case or set of cases to study cannot appear random. Evidence that supports the method by which you identified and chose your subject of analysis should clearly support investigation of the research problem and linked to key findings from your literature review. Be sure to cite any studies that helped you determine that the case you chose was appropriate for examining the problem.

IV. Discussion

The main elements of your discussion section are generally the same as any research paper, but centered around interpreting and drawing conclusions about the key findings from your analysis of the case study. Note that a general social sciences research paper may contain a separate section to report findings. However, in a paper designed around a case study, it is common to combine a description of the results with the discussion about their implications. The objectives of your discussion section should include the following:

Reiterate the Research Problem/State the Major Findings Briefly reiterate the research problem you are investigating and explain why the subject of analysis around which you designed the case study were used. You should then describe the findings revealed from your study of the case using direct, declarative, and succinct proclamation of the study results. Highlight any findings that were unexpected or especially profound.

Explain the Meaning of the Findings and Why They are Important Systematically explain the meaning of your case study findings and why you believe they are important. Begin this part of the section by repeating what you consider to be your most important or surprising finding first, then systematically review each finding. Be sure to thoroughly extrapolate what your analysis of the case can tell the reader about situations or conditions beyond the actual case that was studied while, at the same time, being careful not to misconstrue or conflate a finding that undermines the external validity of your conclusions.

Relate the Findings to Similar Studies No study in the social sciences is so novel or possesses such a restricted focus that it has absolutely no relation to previously published research. The discussion section should relate your case study results to those found in other studies, particularly if questions raised from prior studies served as the motivation for choosing your subject of analysis. This is important because comparing and contrasting the findings of other studies helps support the overall importance of your results and it highlights how and in what ways your case study design and the subject of analysis differs from prior research about the topic.

Consider Alternative Explanations of the Findings Remember that the purpose of social science research is to discover and not to prove. When writing the discussion section, you should carefully consider all possible explanations revealed by the case study results, rather than just those that fit your hypothesis or prior assumptions and biases. Be alert to what the in-depth analysis of the case may reveal about the research problem, including offering a contrarian perspective to what scholars have stated in prior research if that is how the findings can be interpreted from your case.

Acknowledge the Study's Limitations You can state the study's limitations in the conclusion section of your paper but describing the limitations of your subject of analysis in the discussion section provides an opportunity to identify the limitations and explain why they are not significant. This part of the discussion section should also note any unanswered questions or issues your case study could not address. More detailed information about how to document any limitations to your research can be found here .

Suggest Areas for Further Research Although your case study may offer important insights about the research problem, there are likely additional questions related to the problem that remain unanswered or findings that unexpectedly revealed themselves as a result of your in-depth analysis of the case. Be sure that the recommendations for further research are linked to the research problem and that you explain why your recommendations are valid in other contexts and based on the original assumptions of your study.

V. Conclusion

As with any research paper, you should summarize your conclusion in clear, simple language; emphasize how the findings from your case study differs from or supports prior research and why. Do not simply reiterate the discussion section. Provide a synthesis of key findings presented in the paper to show how these converge to address the research problem. If you haven't already done so in the discussion section, be sure to document the limitations of your case study and any need for further research.

The function of your paper's conclusion is to: 1) reiterate the main argument supported by the findings from your case study; 2) state clearly the context, background, and necessity of pursuing the research problem using a case study design in relation to an issue, controversy, or a gap found from reviewing the literature; and, 3) provide a place to persuasively and succinctly restate the significance of your research problem, given that the reader has now been presented with in-depth information about the topic.

Consider the following points to help ensure your conclusion is appropriate:

- If the argument or purpose of your paper is complex, you may need to summarize these points for your reader.

- If prior to your conclusion, you have not yet explained the significance of your findings or if you are proceeding inductively, use the conclusion of your paper to describe your main points and explain their significance.

- Move from a detailed to a general level of consideration of the case study's findings that returns the topic to the context provided by the introduction or within a new context that emerges from your case study findings.

Note that, depending on the discipline you are writing in or the preferences of your professor, the concluding paragraph may contain your final reflections on the evidence presented as it applies to practice or on the essay's central research problem. However, the nature of being introspective about the subject of analysis you have investigated will depend on whether you are explicitly asked to express your observations in this way.

Problems to Avoid

Overgeneralization One of the goals of a case study is to lay a foundation for understanding broader trends and issues applied to similar circumstances. However, be careful when drawing conclusions from your case study. They must be evidence-based and grounded in the results of the study; otherwise, it is merely speculation. Looking at a prior example, it would be incorrect to state that a factor in improving girls access to education in Azerbaijan and the policy implications this may have for improving access in other Muslim nations is due to girls access to social media if there is no documentary evidence from your case study to indicate this. There may be anecdotal evidence that retention rates were better for girls who were engaged with social media, but this observation would only point to the need for further research and would not be a definitive finding if this was not a part of your original research agenda.

Failure to Document Limitations No case is going to reveal all that needs to be understood about a research problem. Therefore, just as you have to clearly state the limitations of a general research study , you must describe the specific limitations inherent in the subject of analysis. For example, the case of studying how women conceptualize the need for water conservation in a village in Uganda could have limited application in other cultural contexts or in areas where fresh water from rivers or lakes is plentiful and, therefore, conservation is understood more in terms of managing access rather than preserving access to a scarce resource.

Failure to Extrapolate All Possible Implications Just as you don't want to over-generalize from your case study findings, you also have to be thorough in the consideration of all possible outcomes or recommendations derived from your findings. If you do not, your reader may question the validity of your analysis, particularly if you failed to document an obvious outcome from your case study research. For example, in the case of studying the accident at the railroad crossing to evaluate where and what types of warning signals should be located, you failed to take into consideration speed limit signage as well as warning signals. When designing your case study, be sure you have thoroughly addressed all aspects of the problem and do not leave gaps in your analysis that leave the reader questioning the results.

Case Studies. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Gerring, John. Case Study Research: Principles and Practices . New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007; Merriam, Sharan B. Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education . Rev. ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1998; Miller, Lisa L. “The Use of Case Studies in Law and Social Science Research.” Annual Review of Law and Social Science 14 (2018): TBD; Mills, Albert J., Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010; Putney, LeAnn Grogan. "Case Study." In Encyclopedia of Research Design , Neil J. Salkind, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010), pp. 116-120; Simons, Helen. Case Study Research in Practice . London: SAGE Publications, 2009; Kratochwill, Thomas R. and Joel R. Levin, editors. Single-Case Research Design and Analysis: New Development for Psychology and Education . Hilldsale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1992; Swanborn, Peter G. Case Study Research: What, Why and How? London : SAGE, 2010; Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods . 6th edition. Los Angeles, CA, SAGE Publications, 2014; Walo, Maree, Adrian Bull, and Helen Breen. “Achieving Economic Benefits at Local Events: A Case Study of a Local Sports Event.” Festival Management and Event Tourism 4 (1996): 95-106.

Writing Tip

At Least Five Misconceptions about Case Study Research

Social science case studies are often perceived as limited in their ability to create new knowledge because they are not randomly selected and findings cannot be generalized to larger populations. Flyvbjerg examines five misunderstandings about case study research and systematically "corrects" each one. To quote, these are:

Misunderstanding 1 : General, theoretical [context-independent] knowledge is more valuable than concrete, practical [context-dependent] knowledge. Misunderstanding 2 : One cannot generalize on the basis of an individual case; therefore, the case study cannot contribute to scientific development. Misunderstanding 3 : The case study is most useful for generating hypotheses; that is, in the first stage of a total research process, whereas other methods are more suitable for hypotheses testing and theory building. Misunderstanding 4 : The case study contains a bias toward verification, that is, a tendency to confirm the researcher’s preconceived notions. Misunderstanding 5 : It is often difficult to summarize and develop general propositions and theories on the basis of specific case studies [p. 221].

While writing your paper, think introspectively about how you addressed these misconceptions because to do so can help you strengthen the validity and reliability of your research by clarifying issues of case selection, the testing and challenging of existing assumptions, the interpretation of key findings, and the summation of case outcomes. Think of a case study research paper as a complete, in-depth narrative about the specific properties and key characteristics of your subject of analysis applied to the research problem.

Flyvbjerg, Bent. “Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 12 (April 2006): 219-245.

- << Previous: Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Next: Writing a Field Report >>

- Last Updated: May 7, 2024 9:45 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

What the Case Study Method Really Teaches

- Nitin Nohria

Seven meta-skills that stick even if the cases fade from memory.

It’s been 100 years since Harvard Business School began using the case study method. Beyond teaching specific subject matter, the case study method excels in instilling meta-skills in students. This article explains the importance of seven such skills: preparation, discernment, bias recognition, judgement, collaboration, curiosity, and self-confidence.

During my decade as dean of Harvard Business School, I spent hundreds of hours talking with our alumni. To enliven these conversations, I relied on a favorite question: “What was the most important thing you learned from your time in our MBA program?”

- Nitin Nohria is the George F. Baker Professor of Business Administration, Distinguished University Service Professor, and former dean of Harvard Business School.

Partner Center

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 21 July 2021

A case study of university student networks and the COVID-19 pandemic using a social network analysis approach in halls of residence

- José Alberto Benítez-Andrades 1 ,

- Tania Fernández-Villa 2 ,

- Carmen Benavides 1 ,

- Andrea Gayubo-Serrenes 3 ,

- Vicente Martín 2 , 4 &

- Pilar Marqués-Sánchez 5

Scientific Reports volume 11 , Article number: 14877 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

11k Accesses

7 Citations

15 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Epidemiology

- Health care

- Public health

The COVID-19 pandemic has meant that young university students have had to adapt their learning and have a reduced relational context. Adversity contexts build models of human behaviour based on relationships. However, there is a lack of studies that analyse the behaviour of university students based on their social structure in the context of a pandemic. This information could be useful in making decisions on how to plan collective responses to adversities. The Social Network Analysis (SNA) method has been chosen to address this structural perspective. The aim of our research is to describe the structural behaviour of students in university residences during the COVID-19 pandemic with a more in-depth analysis of student leaders. A descriptive cross-sectional study was carried out at one Spanish Public University, León, from 23th October 2020 to 20th November 2020. The participation was of 93 students, from four halls of residence. The data were collected from a database created specifically at the university to "track" contacts in the COVID-19 pandemic, SiVeUle. We applied the SNA for the analysis of the data. The leadership on the university residence was measured using centrality measures. The top leaders were analyzed using the Egonetwork and an assessment of the key players. Students with higher social reputations experience higher levels of pandemic contagion in relation to COVID-19 infection. The results were statistically significant between the centrality in the network and the results of the COVID-19 infection. The most leading students showed a high degree of Betweenness, and three students had the key player structure in the network. Networking behaviour of university students in halls of residence could be related to contagion in the COVID-19 pandemic. This could be described on the basis of aspects of similarities between students, and even leaders connecting the cohabitation sub-networks. In this context, Social Network Analysis could be considered as a methodological approach for future network studies in health emergency contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Identification of cohesive subgroups in a university hall of residence during the COVID-19 pandemic using a social network analysis approach

Network analysis of depressive symptoms in Hong Kong residents during the COVID-19 pandemic

Improving the visibility of minorities through network growth interventions

Introduction.

Adversities seem to have been a permanent reality in the last decade 1 . Their consequences cause damage to people's lives that deserve the attention of political leaders and researchers. In the context of any disaster, models of human behaviour are constructed that reflect the importance of relationships between actors, between actors and knowledge, and even between actors and beliefs 2 .

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the COVID-19 a global emergency on January 31, 2020 3 . It is one of the disasters that has had the greatest impact on our history. Recent studies have already shown that the COVID-19 pandemic appears to have an impact on mental health, leading to anxiety, depression, disturbed sleep quality and even increased perceptions of loneliness 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 . In the same sense, the impact of the pandemic has also "hit" young people, who go to school every day but who have seen their social relationships decline. The educational context was always present in the strategies implemented in previous pandemics. Some of the most common measures were the closure of schools to contain the transmission of influenza 12 , support through informal networks on university campuses during the influenza A(H1N1) pandemic 13 , and the need to increase knowledge on the pandemic, as it was found to influence everyday attitudes and practices 14 .

One of the measures that has had the greatest social impact in the COVID-19 pandemic has been the obligation to maintain a physical distance. Specifically, in the field of higher education, it seems to be remarkably complex and more difficult to carry out 15 . University campuses are of interest for studying social behaviour in the context of a pandemic. Numerous studies have shown how university students acquire healthy habits or, conversely, drug and alcohol consumption habits, depending on the type of relationships they have on campus and in the university residences 16 , 17 .

However, there is a lack of studies that analyse the behaviour of university students based on their social structure during a pandemic. Therefore, a quantitative understanding of the behaviour of students in a health emergency situation is necessary as this information could be useful in making decisions about how to prepare for disasters. That is, how to act appropriately during and after an emergency of any kind, since interpersonal relationships, through which supportive and interdependent links are established and which are present in any emergency or disaster.

To address this structural perspective, the SNA method has been applied. The SNA is a distinctive perspective within the social and behavioural sciences. It is distinctive because it is based on the fact that relationships take place between interacting units 18 . For the SNA method, the unit of analysis is not the isolated individual, but the social entity made up of the actor with its possible connections, generating a structure 19 . The main perspective of the SNA focuses on the importance of the relationships between the units that interact in the social networks 18 . A social network is made up of a set of points or nodes that represent individuals or groups, and a set of lines that represent the interaction or otherwise, between the nodes, generating a social structure 20 .

One of the most relevant premises of the SNA, for our study, is that it is not only assumed that individuals are connected through a structure, but that their goals and objectives are as well, because these are only achieved through connections and relationships 19 , 21 , 22 . Thus, the SNA could show us if university students with a more responsible goal form their own networks or mingle with their not-so-responsible peers. In relation to the groups, the actors influence and inform each other in a process that creates a growing homogeneity 21 . This perspective is of interest to this research.

The contacts between actors can be analyzed in two types of networks: sociocentric or complete networks and egocentric networks. The former includes an analysis between actors that belong to a delimited and previously defined census 23 . While the latter analyzes the structure that is generated between an ego and its contacts 24 .

There is an extensive core of studies on SNA and health habits. Some of the most recent are related to contagion in substance use 25 , 26 , physical activity 27 , behavior related to the individual's low weight 28 , engagement in university rooms 29 or eating behaviors 30 among others. SNA has even been applied to disaster scenarios such as droughts, floods, landslides, tsunamis, and cyclones 31 . No one thought that one year after this study, its results would be so useful for another scenario related to a major catastrophe such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Other recent studies shows a social network analysis approach in the problematic internet use among residential college students during COVID-19 lockdown 32 or associations between interpersonal relationships and mental health 33 .

Based on the above, the purpose of this study was to analyse a community of university students and their structural behaviour in their university residences. Halls of residence form micro-communities where very close relationships develop, which can become a context of risk. In other words, university residences could become "places" that facilitate the spread of pandemics if adequate protocols are not followed. However, dormitories can also have a preventive value. Peer support behavioural patterns take place in them, among peers who are exposed to the same risks and circumstances. This sharing of similar situations can generate an enriching coping of personal experiences 34 . However, there is a lack of studies that analyse the structures of university students and their coping in crisis situations.

This study was conducted during one of the waves of the COVID-19 pandemic, where infection rates were at their highest. With the SNA methodology, the aim is to find answers to questions such as: What are the structural characteristics of the leading individuals in the dormitories? How are the contagion outcomes related to the structural positions in the network? For such questions, the proposed objectives were (i) to analyse the relationship between the students' network position and their outcomes with respect to the COVID-19 contagion, (ii) to describe the influential position of student leaders in the network, (iii) to analyse the Egonetwork of the most influential student leaders during the COVID-19 pandemic, and (iv) to visualise the relational behaviour of university students in the global network.

Study design

A descriptive cross-sectional study was carried out at one Spanish Public University. The data was collected during one of the waves of the pandemic, specifically from 23th October 2020 to 20th November 2020.

The measures taken during the pandemic in the different regions of Spain were different, depending on the results of the contagion at each moment. At the time of carried out this study, teaching in the locality of the study was adapted to the situation. That is, there were limitations on the number of people, "mirror" classrooms, identification of QR, etc. In the town there was a limit to the number of people who could meet, pubs and discotheques had been closed, and there was a 10 pm curfew.

Setting and sample

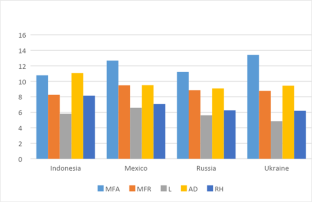

The participation was of 93 students, from 4 university residences. The characteristics of the sample can be seen in Table 1 . Of the total participants, 32.26% were women and 67.74% men.

Ethical consideration

All participants received an informed consent form to participate in the study. Lastly, participants were offered the possibility of retracting consent once they had signed the form, without needing to provide a reason, and an email contact address was given should they require any further information. Participation was voluntary, and subject availability was respected at all times. All the participants that were involved in the study have given their informed consent to participate in this study.

The data for this study are considered health-related data. They comply with Directive 03/2020 of the European Data Protection Committee 35 . The researchers requested anonymised data from the responsible body of the university in charge of contacts COVID-19.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of León (ETICA-ULE-008-2021).

Data collection

We collected the data from the database created at the university, SIVeULE, created for the follow-up of cases of COVID-19. This database collates the characteristics of the actors and their RT-qPCR result.

In the university there was a protocol to indicate norms and rules of (i) hygiene and preventive measures, (ii) what to do if you had symptoms, (iii) definitions of what was considered "close contact", "confinement", and " positive result ". There was support staff to collect data, deal with doubts, and assist both positive actors and confined actors. These people were called "trackers." The name defined their role because they identified the student's contacts that were positive, had symptoms, or had been "in close contact” with a positive person.

In the database, other data such as name, residence, gender, grade, name of contacts, and date and result of Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) test are also collected.

For the present study, the names were anonymized and registered in matrices for subsequent analysis using the SNA method.

The data obtained were used to construct a 93 × 93 matrix. The matrix was read as follows:

For rows, “A nominates B”;

For columns, “A is nominated by B”.

To carry out this study, the matrix has been symmetrized, determining that if A nominated B, B also nominated A. That is to say, it is an undirected matrix, since, if A had any contact with B, B also had contact with A.

Data analysis

For data analysis, we apply SNA to the 93 × 93 matrix. measures of centrality were applied to analyse leadership from a structural perspective. Centrality is a construct of the SNA that means the position in the network 18 . Previous researchers have applied SNA to the study of leadership, because they have conceptualized leadership as a process that starts from the collective and the interconnections 36 , 37 , 38 . For this study, the centrality measures selected were: degree, betweenness and eigenvector 18 :

The degree is the number of connections adjacent to an actor. Given the centrality of degree \({d}_{i}\) of the actor i and \({x}_{ij}\) is the cell ( i, j ) of the adjacency matrix, then

Betweenness centrality is defined as the Extent to which an actor serves as a potential “go-between” for other pairs of actors in the network by occupying an intermediary position on the shortest paths connecting other actors. The formula for the centrality of node j is given by the:

In this formula, \({g}_{ijk}\) represents the number of geodetic paths that connect i and k and through k while \({g}_{ik}\) is the total number of geodetic paths between i and k .

Eigenvector centrality corresponds to the measure of actor centrality that takes into account the centrality of the actors to whom the focal actor is connected.

Normalized measures were used.

The measures of centrality studied in the SNA have been the normalized degree (nDegree, the normalized degree centrality is the degree divided by the maximum possible degree expressed as a percentage), Eigenvector and nBetweenness (is the normalized betweenness centrality computed as the betweenness divided by the maximum possible betweenness).

To select the most leading students in the network, the measure of normalized nBetweenness was used 39 . This measure becomes more relevant during a pandemic, where the possibility of serving as a bridge or intermediary allows other networks to reach out, transferring good or bad practices and behaviors.

In order to have more information about the behaviour of the student leaders, the Egonetwork analysis of the most leading nodes for each component was carried out. Key players theory has been used to obtain this group of students displaying greater leadership 40 . Egonetwork studies the connections of a given node. This analysis in isolation is less comprehensive than the analysis of the entire network. But the researchers recommend this analysis combined with the analysis of the whole network to go deeper into the behaviour of certain nodes, depending on the objective of the research 24 , 34 , 41 .

Statistical analysis and visualisation

IBM SPSS Statistics (26.0) software. was used for the statistical processing of the data. For the analysis of descriptive data, frequencies and percentages were used for the qualitative variables, whereas the mean and standard deviation were used for the quantitative variables. A chi-square test was carried out to verify whether there was a relationship between the groups, and the Student’s t-test was used to compare the mean scores between the groups. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was carried out to check the differences for continuous variables divided in groups. The UCINET tool, version 6.679 42 was used for the calculation of the SNA measurements. The tests carried out to study the normality of the distribution were Kolmogorov–Smirnov for populations of more than 55 individuals and the Shapiro–Wilk test for those less than or equal to 55. The level of statistical significance was set at 0.05. For qualitative analysis, a visualization of the global network will be carried out using Gephi, version 0.9.2, software. The key player tool has been used to calculate the key players of the network 43 .

As shown in Table 2 , there was a significant effect of residence on nDegree [F(3,89) = 22.135, p < 0.001] and Eigenvector [F(3,89) = 151.035, p < 0.001] and there was no significant effect of residence on nBetweenness [F = (3,89),p = 0.784].

Students in residence C have significantly higher degrees of centrality in nDegree and Eigenvector compared to the other residences. In the case of nBetweenness, students in residences A and D have higher values, although not significantly so.

Significant differences in all measures of centrality (nDegree, Eigenvector and nBetweenness) measures were found for the groups of people who tested positive for RT-qPCR (PCR +) versus those who tested negative for PCR (PCR-). The PCR + group of people had higher values of centrality than the PCR- group. The degrees of significance of these differences are shown in Table 3 .

Significant differences were found between leaders and non-leaders calculated with the three measures of centrality and the prevalence of people who tested positive or negative for PCRs. Leaders had a higher percentage of people in the PCR + group compared to non-leaders. The degrees of significance of these differences are shown in Table 4 .

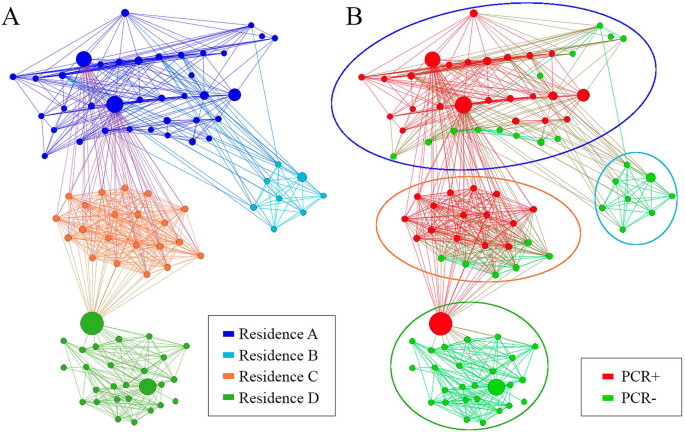

Figure 1 A shows the nodes of the study network highlighting in each colour which residence each one belongs to (A,B,C or D). In Fig. 1 B the same network can be seen but the nodes with PCR + appear in red and and the nodes with PCR- in green. The distribution of the network allows us to appreciate the 4 different residences. The size of the nodes is represented by the nBetweenness of each node.

Graphs of the university student network differentiating a colour for each residence hall ( A ) and differentiating the positive and negative PCR groups ( B) .

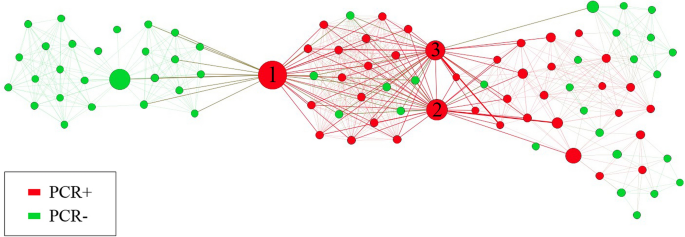

Figure 2 shows the network highlighting the trajectories of the three most important key players. The edges coming out of these key players are thicker than the others. Furthermore, the key players are numbered in order of importance in the network (1, 2 and 3). The size of the nodes is represented by the nBetweenness of each node.

The network shown under the Atlas 2 distribution highlighting the 3 most important key players in the network.

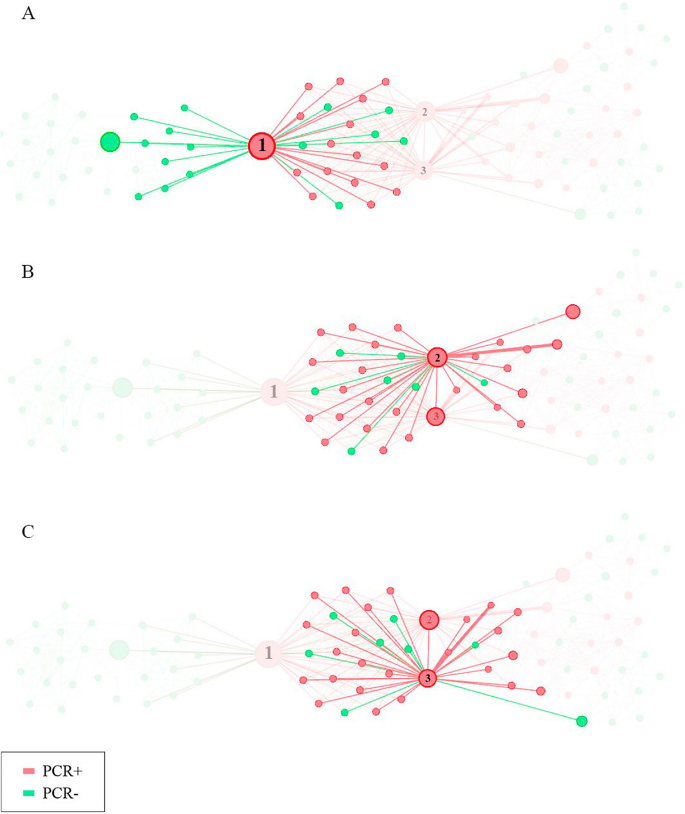

Figure 3 shows the Egonetworks of the 3 key players in the network. Figure 3 A shows the most important key player in the network. If this node were eliminated, the two components would be separated (those of the C and D residence). Figure 3 B,C show the Egonetworks of the key players 2 and 3 respectively. These nodes are structurally very similar. If both nodes were removed from the network, there would no longer be a connection between residence C and residences A and B.

Egonetworks of the 3 main key players of the network.

This research contributes empirical evidence based on a social network approach to the development of the COVID-19 pandemic on university halls of residence. We have presented a study strategy and results, which link the relationship between the centrality of leaders and the outcome of pandemic infection. There is a significant core of research using the SNA methodology applied to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, there is a lack of research focusing on the structural responses of university students, a population of particular interest given their training experience. A university student "absorbs" experiences that are translated into behaviour, and transfers the resources obtained through their relationships.

Our results demonstrate the relationship between the centrality in the network of student leaders and the outcome of their infection (positive or negative). Not only could leaders spread pandemic behaviour towards their more local peers, they also seem to spread it to other halls of residence. This is demonstrated by the structure of betweenness. Leaders with a higher degree of betweenness could become key players, so that their presence or absence can disconnect the various components of the entire network. This could lead to a disconnection of the contagion process, both on a positive and negative level. The findings are the first to demonstrate that networks in university accommodation develop successful or unsuccessful responses to a pandemic. University managers should take these findings into account when developing response and behavioural strategies in pandemic or disaster situations. Strategies should be designed with a network rather than an individual approach.

Although our study did not ask about the relationship between the actors, we understand that the contacts established between the students are relationships of friendship or good classmates. We only analysed whether or not people had been in contact, during a state of lockdown. But obviously, with the SNA, we can visualise relational behaviours that would be more difficult to appreciate using other methodologies.

Our results show that student leaders have a high degree of centrality not only at the local level, i.e. in the component related to their accommodation, but also at the level of the global network. Our results are in line with studies of Mehra et al. 36 , who highlighted that the integration of a leader into the friendship network in one social circle can be related to the reputation of the leader in other social circles.

Leadership or reputation at the local level is related to the performance of the team, and leadership outside the team is what allows new opportunities to arise and new information to be disseminated 36 . In the case of university students in their accommodation, the aim is to have a friendly atmosphere and to collaborate in difficult moments, to motivate each other, etc. Our results shown a statistically significant relationship between leadership and the positive results of the COVID-19 tests. In this sense, previous studies have already found that having too many resources related to social capital in a group (such as centrality) could negatively affect the efficiency of the group 44 . In other words, the leader will exert an influence on his or her colleagues and this influence could "infect" a certain behaviour, in this case of responsibility or not in a state of health emergency.

Another aspect demonstrated in our research is that there is a similarity between student groupings in terms of their COVID-19 test results. That is, we observe groups where the results are all positive (nodes in red), and others where the results are negative (nodes in green). This finding, could be related to numerous previous studies where actors occupy similar social positions in the classroom. For example, the studies from 45 showed that stuttering students had the same social position as the rest of their peers, because both (stutterers and non-stutterers) tended to design their groups structurally the same.

Homophily theory indicates that individuals associate with those with whom they share aspects of similarity, such as similar beliefs, characteristics and behaviours, which occurs especially in young people and adolescents 46 Therefore, this may partly justify why negative-test college students are more cohesive, and positive-test college students as well.

One of the measures implemented with the greatest impact in this COVID-19 pandemic has been social distancing or isolation. The closure of premises or the reduction in hours of places of leisure has led to this social, or rather physical, distancing, as it is physical contact that is avoided. Studies have shown that the reduction in contacts based on social networks that coexist in social bubbles, and the similarity between contacts, increase social distancing from other actors, and therefore decrease the risks of contagion 47 . But in the case of this research, university accommodation could not be considered as a bubble. We could think of them as big bubbles, where behavioural patterns become contagious, be they positive and negative ones. Therefore, in this sense, the directors of the centres should take note and plan different strategies according to the behaviour of the subnetworks. That is to say, promote those behaviours with negative results of contagion and intervene in those subnetworks with positive results. For this, and as explained previously, the best option would be to plan together with the leaders.

Our results have shown that students with a high degree of Betweenness have a position in the network that gives them great leadership. In this sense, previous studies have used this structural metric as a predictor of leadership due to the strategic position that the actors have in the network and their role in bridging different networks 39 , 48 .

For a better understanding of the role of these actors, in this research we analyse these university students on the basis of two more structural issues. On the one hand, which of them could have a key player role. Secondly, to analyse the Egonetwork of those students with a greater degree of centrality in each of the components.

As regards key players, our results showed that 3 students with a high degree of betweenness, i.e. with an intermediary role, had a key player structure. The importance of the key actor has been explained perfectly by Borgatti (2006) 40 , describing both the negative and positive aspects. The negative is that the network, or networks, actually depend on these nodes, and cohesion between the networks would be diminished if these actors were to disappear 40 . This problem is greater when, in a public health context, we select a small number of individuals to contain a pandemic or to reduce the risk of contagion that links different networks. If these actors disappeared, the number of those infected would increase. As regards the positive role of these actors, they are ideal for spreading attitudes and behaviour, because they quickly gain access to different networks. Borgatti (2006) explains the importance of the structure of the key players, with the same relevance in very different contexts, such as terrorist networks or pandemic contexts 40 . In our case, our results are supported by the justification of this great researcher.

Our findings have shown that student leaders with a higher degree of Betweenness had a higher density than their peers in their Egonetworks . This could facilitate the transmission of social capital in a context such as the COVID-19 pandemic. These students, who serve as bridges, could become key actors with the ability to mobilize and coordinate social activity 49 . Their role is key for other colleagues, since they could serve as a "mirror" to "invite" appropriate behaviors in a health emergency. The key question that remains is, what behavior do they have? Structurally, the present investigation has demonstrated and justified that its position in the network is a model that could be disseminated among the rest of the actors.

To summarize the above, those responsible for universities must take into account the collective behavior of its networks. In a context such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the diffusion of behaviors is very relevant. Authors call for “urban intelligence” as a possible strategy to deal effectively with a pandemic. They understand that the impact of a health emergency is more than just a public health problem since it involves social risks and instability. This situation would be better dealt with by having the best that the social and community structure can offer, the so-called "urban intelligence” 50 .

SNA could provide a set of terms and concepts to explain and describe social phenomena 51 . The method offers a distinctive approach to analysing leadership in disaster processes. Leaders could be like "builders" of social responses and the managers of the universities should take it into account for the intervention processes.

The most important limitations of this study should be considered for future research. For example, it would be of interest to carry out other analyzes focused more on the cohesion of the network and the behavior of the subgroups, in order to draw structural conclusions at the micro level. Future lines of research could focus on comparing the students’ leadership in terms of structure with leadership as perceived by both them and their own peers.

Conclusions

The present research has carried out a study with students in university residences. The aim has been to describe the structural behaviour of students in university residences during the COVID-19 pandemic, with a more in-depth analysis of student leaders. The specific objectives proposed to develop the research were to: (i) analyse the relationship between the position of students in the network and their results with respect to COVID-19 infection, (ii) describe the position of influence of student leaders in the network, (iii) analyzing the Egonetwork of the most influential student leaders on the COVID-19 pandemic, and (iv) visualise the relational behaviour of university students in the global network.

The main conclusions derived from the results are detailed below:

The most central students in the network, had more positive results regarding COVID-19 infection.

The leadership of the confined students was related to higher degree, eigenvector and betweenness.

A small core of leaders are key players, so their role conditions the connection or disconnection between different components of the global network.

Students with a key player structure show a similar Egonetwork if they belong to the same residence.

There is a student leader with the maximum key player power structure, causing a total disconnection between networks if he/she disappears from the global network.

The findings show that strategies to cope with a disaster or pandemic need to be addressed through a network approach. University managers will need to have a profound understanding of students' relational behaviour. Only then will the most restrictive measures be effective. Responsible or irresponsible behaviour is transferred through the connections between students, so Social Network Analysis should be considered as a method of analyzing the evolution of a pandemic at the societal level. Any crisis involves contacts, but in a pandemic, contacts can transfer infection. Also in a pandemic, contacts can transfer habits and behaviours "passed on" by leaders, so that they allow for more effective coping. All of this can be analysed using SNA. Our study provides findings with an innovative approach, achieved with SNA. Among the limitations of the study it should be noted that the sample is very small (n = 93). This means that we cannot state categorically the representativeness of the results presented. However, the results could be used for future research where it is useful to analyse health emergency contexts as a network rather than analysing individuals in isolation.

UNISDR. Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction Making Development Sustainable: The Future of Disaster Risk Management . (2015).

Rodrigueza, R. C. & Estuar, M. R. J. E. Social network analysis of a disaster behavior network: An agent-based modeling approach. in Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advance Social Networks Analysis Mining, ASONAM 2018 1100–1107. https://doi.org/10.1109/ASONAM.2018.8508651 (2018).

World Health Organization (WHO). Coronavirus disease 2019 (2019-nCOV) situation report-11. WHO Bull. 1–7 (2020).

Bauer, L. L. et al. Associations of exercise and social support with mental health during quarantine and social-distancing measures during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional survey in Germany. medRxiv . https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.01.20144105 (2020).

Grey, I. et al. The role of perceived social support on depression and sleep during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 293 , 113452 (2020).

Rozanova, J. et al. Social support is key to retention in care during Covid-19 pandemic among older people with HIV and substance use disorders in Ukraine. Subst. Use Misuse 55 (11), 1902–1904 (2020).

Arendt, F., Markiewitz, A., Mestas, M. & Scherr, S. COVID-19 pandemic, government responses, and public mental health: Investigating consequences through crisis hotline calls in two countries. Soc. Sci. Med. 265 , 113532 (2020).

Chirico, F. The role of health surveillance for the SARS-CoV-2 risk assessment in the schools. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 63 , e255–e256 (2021).

Chirico, F. & Ferrari, G. Role of the workplace in implementing mental health interventions for high-risk groups among the working age population after the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Health Soc. Sci. 6 , 145–150 (2021).

Google Scholar

Chirico, F. et al. Prevalence of anxiety, depression, burnout syndrome, and mental health disorders among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic : A rapid umbrella review of systematic reviews. J. Health Soc. Sci. 6 , 209–220 (2021).

Shala, M., Çollaku, P. J., Hoxha, F., Balaj, S. B. & Preteni, D. One year after the first cases of COVID-19: Factors influencing the anxiety among Kosovar university students. J. Health Soc. Sci. 6 , 241–254 (2021).

Glass, L. M. & Glass, R. J. Social contact networks for the spread of pandemic influenza in children and teenagers. BMC Public Health 8 , 1–15 (2008).

Article Google Scholar

Wilson, S. L. & Huttlinger, K. Pandemic flu knowledge among dormitory housed university students: A need for informal social support and social networking strategies. Rural Remote Health 10 , 1526 (2010).

PubMed Google Scholar