Home — Essay Samples — Sociology — Race and Ethnicity — American Identity

Essays on American Identity

Hook examples for identity essays, anecdotal hook.

Standing at the crossroads of cultures and heritage, I realized that my identity is a mosaic, a tapestry woven from the threads of my diverse experiences. Join me in exploring the intricate journey of self-discovery.

Question Hook

What defines us as individuals? Is it our cultural background, our values, or our personal beliefs? The exploration of identity leads us down a path of introspection and understanding.

Quotation Hook

"To be yourself in a world that is constantly trying to make you something else is the greatest accomplishment." These words from Ralph Waldo Emerson resonate as a testament to the importance of authentic identity.

Cultural Identity Hook

Our cultural roots run deep, shaping our language, traditions, and worldview. Dive into the rich tapestry of cultural identity and how it influences our sense of self.

Identity and Belonging Hook

Human beings have an innate desire to belong. Explore the intricate relationship between identity and the sense of belonging, and how it impacts our social and emotional well-being.

Identity in a Digital Age Hook

In an era of social media and digital personas, our sense of identity takes on new dimensions. Analyze how technology and online interactions shape our self-perception.

Identity and Self-Acceptance Hook

Coming to terms with our true selves can be a challenging journey. Explore the importance of self-acceptance and how it leads to a more authentic and fulfilling life.

American Identity in Sandra Cisneros Mericans

American identity in mericans, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

I Love America Research Paper

The way an american identity is created, characteristics that shaped an american identity, an overview of the evolution of the american identity, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Questioning The Identity: The Meaning of Being an American

What does it mean to be an american citizen, the rising of american identity, what america means to me, get a personalized essay in under 3 hours.

Expert-written essays crafted with your exact needs in mind

The American Identity and The Role of The Foreigner in American Nation and Other Nations

An analysis of native american identity as a result of colonialism in sherman alexie's novel the absolutely true diary of a part-time indian, a discussion on latin americans developing their american identity, the view of frederick douglass on american identity, what it means to live in america, what it means to be an american today, the impact of class in social identity, representation of the american family in the works of roth and miller, my cultural identity: who i am, understanding the concept of the american dream, freedom as the root of what it means to be an american, what america means to you: education, rights, and equality, tocqueville on the toxicity of american ideals, american dream as an integral part of american ideals, the evolution of native american identity in joy harjo's poetry, establishment of american ideals during american revolution, the great gatsby: what it means to be an american in a negative connotation, italian-american identity in stallone's rocky, exploring america’s identity subjugation in "americanah", representation of toxic american masculinity in slaughterhouse-five by kurt vonnegut.

National identity can be defined as an overarching system of collective characteristics and values in a nation, American identity has been based historically upon: “race, ethnicity, religion, culture and ideology”.

Relevant topics

- Social Justice

- Cultural Appropriation

- Discourse Community

- Sociological Imagination

- Social Media

- Effects of Social Media

- Media Analysis

- Sex, Gender and Sexuality

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Research: What Is American Identity and Why Does It Matter?

Why Does the American Identity Matter?

The most important reason for understanding American identity is related to white racial identification. It may not be prevalent in U.S. political attitudes, but it’s still an issue. A survey from 2012 asked white respondents to indicate if whiteness represented the way they thought of themselves most of the time, as opposed to identifying themselves as Americans . One fifth of the survey’s white respondents said that they preferred the term white to American when identifying themselves.

How to Analyze American Identity

- There’s no such thing as a universal identity, especially for an omni-cultural country such as the USA.

- Everyone has their own understanding of what it means to be American today, as citizens come from different religious, ethnic, ideological, and geographical backgrounds.

- Explaining the concept of American identity calls for an inclusive approach based on solidarity.

- Depending on how you discuss the concept, an academic essay may require arguments on modern-day immigration and immigrant policies. How do they fit within the common understanding of American identity?

Who Are We?

Guest Contributor

The most important good news and events of the day.

Subscribe to our mailing list to receives daily updates direct to your inbox!

Alexandria Gets Another New Mural!

Say hello to the turkish coffee lady, related articles.

Lt. Julia Bucholz, from Alexandria, Serves on The USS Howard

Honoring Gold Star Spouses

La’Baik Mediterranean Restaurant Opens in Del Ray Neighborhood

Volunteers Needed for Jones Point Marsh Cleanup April 21

- Current Issue

- Past Issues

- Get New Issue Alerts

- American Academy of Arts and Sciences

What does it mean to be an American?

Sarah Song, a Visiting Scholar at the Academy in 2005–2006, is an assistant professor of law and political science at the University of California, Berkeley, and the author of Justice, Gender, and the Politics of Multiculturalism (2007). She is at work on a book about immigration and citizenship in the United States.

It is often said that being an American means sharing a commitment to a set of values and ideals. 1 Writing about the relationship of ethnicity and American identity, the historian Philip Gleason put it this way:

To be or to become an American, a person did not have to be any particular national, linguistic, religious, or ethnic background. All he had to do was to commit himself to the political ideology centered on the abstract ideals of liberty, equality, and republicanism. Thus the universalist ideological character of American nationality meant that it was open to anyone who willed to become an American. 2

To take the motto of the Great Seal of the United States, E pluribus unum – "From many, one" – in this context suggests not that manyness should be melted down into one, as in Israel Zangwill's image of the melting pot, but that, as the Great Seal's sheaf of arrows suggests, there should be a coexistence of many-in-one under a unified citizenship based on shared ideals.

Of course, the story is not so simple, as Gleason himself went on to note. America's history of racial and ethnic exclusions has undercut the universalist stance; for being an American has also meant sharing a national culture, one largely defined in racial, ethnic, and religious terms. And while solidarity can be understood as "an experience of willed affiliation," some forms of American solidarity have been less inclusive than others, demanding much more than simply the desire to affiliate. 3 In this essay, I explore different ideals of civic solidarity with an eye toward what they imply for newcomers who wish to become American citizens.

Why does civic solidarity matter? First, it is integral to the pursuit of distributive justice. The institutions of the welfare state serve as redistributive mechanisms that can offset the inequalities of life chances that a capitalist economy creates, and they raise the position of the worst-off members of society to a level where they are able to participate as equal citizens. While self-interest alone may motivate people to support social insurance schemes that protect them against unpredictable circumstances, solidarity is understood to be required to support redistribution from the rich to aid the poor, including housing subsidies, income supplements, and long-term unemployment benefits. 4 The underlying idea is that people are more likely to support redistributive schemes when they trust one another, and they are more likely to trust one another when they regard others as like themselves in some meaningful sense.

Second, genuine democracy demands solidarity. If democratic activity involves not just voting, but also deliberation, then people must make an effort to listen to and understand one another. Moreover, they must be willing to moderate their claims in the hope of finding common ground on which to base political decisions. Such democratic activity cannot be realized by individuals pursuing their own interests; it requires some concern for the common good. A sense of solidarity can help foster mutual sympathy and respect, which in turn support citizens' orientation toward the common good.

Third, civic solidarity offers more inclusive alternatives to chauvinist models that often prevail in political life around the world. For example, the alternative to the Nehru-Gandhi secular definition of Indian national identity is the Hindu chauvinism of the Bharatiya Janata Party, not a cosmopolitan model of belonging. "And what in the end can defeat this chauvinism," asks Charles Taylor, "but some reinvention of India as a secular republic with which people can identify?" 5 It is not enough to articulate accounts of solidarity and belonging only at the subnational or transnational levels while ignoring senses of belonging to the political community. One might believe that people have a deep need for belonging in communities, perhaps grounded in even deeper human needs for recognition and freedom, but even those skeptical of such claims might recognize the importance of articulating more inclusive models of political community as an alternative to the racial, ethnic, or religious narratives that have permeated political life. 6 The challenge, then, is to develop a model of civic solidarity that is "thick" enough to motivate support for justice and democracy while also "thin" enough to accommodate racial, ethnic, and religious diversity.

We might look first to Habermas's idea of constitutional patriotism (Verfassungspatriotismus). The idea emerged from a particular national history, to denote attachment to the liberal democratic institutions of the postwar Federal Republic of Germany, but Habermas and others have taken it to be a generalizable vision for liberal democratic societies, as well as for supranational communities such as the European Union. On this view, what binds citizens together is their common allegiance to the ideals embodied in a shared political culture. The only "common denominator for a constitutional patriotism" is that "every citizen be socialized into a common political culture." 7

Habermas points to the United States as a leading example of a multicultural society where constitutional principles have taken root in a political culture without depending on "all citizens' sharing the same language or the same ethnic and cultural origins." 8 The basis of American solidarity is not any particular racial or ethnic identity or religious beliefs, but universal moral ideals embodied in American political culture and set forth in such seminal texts as the Declaration of Independence, the U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights, Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address, and Martin Luther King, Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech. Based on a minimal commonality of shared ideals, constitutional patriotism is attractive for the agnosticism toward particular moral and religious outlooks and ethnocultural identities to which it aspires.

What does constitutional patriotism suggest for the sort of reception immigrants should receive? There has been a general shift in Western Europe and North America in the standards governing access to citizenship from cultural markers to values, and this is a development that constitutional patriots would applaud. In the United States those seeking to become citizens must demonstrate basic knowledge of U.S. government and history. A newly revised U.S. citizenship test was instituted in October 2008 with the hope that it will serve, in the words of the chief of the Office of Citizenship, Alfonso Aguilar, as "an instrument to promote civic learning and patriotism." 9 The revised test attempts to move away from civics trivia to emphasize political ideas and concepts. (There is still a fair amount of trivia: "How many amendments does the Constitution have?" "What is the capital of your state?") The new test asks more open-ended questions about government powers and political concepts: "What does the judicial branch do?" "What stops one branch of government from becoming too powerful?" "What is freedom of religion?" "What is the 'rule of law'?" 10

Constitutional patriots would endorse this focus on values and principles. In Habermas's view, legal principles are anchored in the "political culture," which he suggests is separable from "ethical-cultural" forms of life. Acknowledging that in many countries the "ethical-cultural" form of life of the majority is "fused" with the "political culture," he argues that the "level of the shared political culture must be uncoupled from the level of subcultures and their prepolitical identities." 11 All that should be expected of immigrants is that they embrace the constitutional principles as interpreted by the political culture, not that they necessarily embrace the majority's ethical-cultural forms.

Yet language is a key aspect of "ethical-cultural" forms of life, shaping people's worldviews and experiences. It is through language that individuals become who they are. Since a political community must conduct its affairs in at least one language, the ethical-cultural and political cannot be completely "uncoupled." As theorists of multiculturalism have stressed, complete separation of state and particularistic identities is impossible; government decisions about the language of public institutions, public holidays, and state symbols unavoidably involve recognizing and supporting particular ethnic and religious groups over others. 12 In the United States, English language ability has been a statutory qualification for naturalization since 1906, originally as a requirement of oral ability and later as a requirement of English literacy. Indeed, support for the principles of the Constitution has been interpreted as requiring English literacy. 13 The language requirement might be justified as a practical matter (we need some language to be the common language of schools, government, and the workplace, so why not the language of the majority?), but for a great many citizens, the language requirement is also viewed as a key marker of national identity. The continuing centrality of language in naturalization policy prevents us from saying that what it means to be an American is purely a matter of shared values.

Another misconception about constitutional patriotism is that it is necessarily more inclusive of newcomers than cultural nationalist models of solidarity. Its inclusiveness depends on which principles are held up as the polity's shared principles, and its normative substance depends on and must be evaluated in light of a background theory of justice, freedom, or democracy; it does not by itself provide such a theory. Consider ideological requirements for naturalization in U.S. history. The first naturalization law of 1790 required nothing more than an oath to support the U.S. Constitution. The second naturalization act added two ideological elements: the renunciation of titles or orders of nobility and the requirement that one be found to have "behaved as a man . . . attached to the principles of the constitution of the United States." 14 This attachment requirement was revised in 1940 from a behavioral qualification to a personal attribute, but this did not help clarify what attachment to constitutional principles requires. 15 Not surprisingly, the "attachment to constitutional principles" requirement has been interpreted as requiring a belief in representative government, federalism, separation of powers, and constitutionally guaranteed individual rights. It has also been interpreted as disqualifying anarchists, polygamists, and conscientious objectors for citizenship. In 1950, support for communism was added to the list of grounds for disqualification from naturalization – as well as grounds for exclusion and deportation. 16 The 1990 Immigration Act retained the McCarthy-era ideological qualifications for naturalization; current law disqualifies those who advocate or affiliate with an organization that advocates communism or opposition to all organized government. 17 Patriotism, like nationalism, is capable of excess and pathology, as evidenced by loyalty oaths and campaigns against "un-American" activities.

In contrast to constitutional patriots, liberal nationalists acknowledge that states cannot be culturally neutral even if they tried. States cannot avoid coercing citizens into preserving a national culture of some kind because state institutions and laws define a political culture, which in turn shapes the range of customs and practices of daily life that constitute a national culture. David Miller, a leading theorist of liberal nationalism, defines national identity according to the following elements: a shared belief among a group of individuals that they belong together, historical continuity stretching across generations, connection to a particular territory, and a shared set of characteristics constituting a national culture. 18 It is not enough to share a common identity rooted in a shared history or a shared territory; a shared national culture is a necessary feature of national identity. I share a national culture with someone, even if we never meet, if each of us has been initiated into the traditions and customs of a national culture.

What sort of content makes up a national culture? Miller says more about what a national culture does not entail. It need not be based on biological descent. Even if nationalist doctrines have historically been based on notions of biological descent and race, Miller emphasizes that sharing a national culture is, in principle, compatible with people belonging to a diversity of racial and ethnic groups. In addition, every member need not have been born in the homeland. Thus, "immigration need not pose problems, provided only that the immigrants come to share a common national identity, to which they may contribute their own distinctive ingredients." 19

Liberal nationalists focus on the idea of culture, as opposed to ethnicity or descent, in order to reconcile nationalism with liberalism. Thicker than constitutional patriotism, liberal nationalism, Miller maintains, is thinner than ethnic models of belonging. Both nationality and ethnicity have cultural components, but what is said to distinguish "civic" nations from "ethnic" nations is that the latter are exclusionary and closed on grounds of biological descent; the former are, in principle, open to anyone willing to adopt the national culture. 20

Yet the civic-ethnic distinction is not so clear-cut in practice. Every nation has an "ethnic core." As Anthony Smith observes

[M]odern "civic" nations have not in practice really transcended ethnicity or ethnic sentiments. This is a Western mirage, reality-as-wish; closer examination always reveals the ethnic core of civic nations, in practice, even in immigrant societies with their early pioneering and dominant (English and Spanish) culture in America, Australia, or Argentina, a culture that provided the myths and language of the would-be nation. 21

This blurring of the civic-ethnic distinction is reflected throughout U.S. history with the national culture often defined in ethnic, racial, and religious terms. 22

Why, then, if all national cultures have ethnic cores, should those outside this core embrace the national culture? Miller acknowledges that national cultures have typically been formed around the ethnic group that is dominant in a particular territory and therefore bear "the hallmarks of that group: language, religion, cultural identity." Muslim identity in contemporary Britain becomes politicized when British national identity is conceived as containing "an Anglo-Saxon bias which discriminates against Muslims (and other ethnic minorities)." But he maintains that his idea of nationality can be made "democratic in so far as it insists that everyone should take part in this debate [about what constitutes the national identity] on an equal footing, and sees the formal arenas of politics as the main (though not the only) place where the debate occurs." 23

The major difficulty here is that national cultures are not typically the product of collective deliberation in which all have the opportunity to participate. The challenge is to ensure that historically marginalized groups, as well as new groups of immigrants, have genuine opportunities to contribute "on an equal footing" to shaping the national culture. Without such opportunities, liberal nationalism collapses into conservative nationalism of the kind defended by Samuel Huntington. He calls for immigrants to assimilate into America's "Anglo- Protestant culture." Like Miller, Huntington views ideology as "a weak glue to hold together people otherwise lacking in racial, ethnic, or cultural sources of community," and he rejects race and ethnicity as constituent elements of national identity. 24 Instead, he calls on Americans of all races and ethnicities to "reinvigorate their core culture." Yet his "cultural" vision of America is pervaded by ethnic and religious elements: it is not only of a country "committed to the principles of the Creed," but also of "a deeply religious and primarily Christian country, encompassing several religious minorities, adhering to Anglo- Protestant values, speaking English, maintaining its European cultural heritage." 25 That the cultural core of the United States is the culture of its historically dominant groups is a point that Huntington unabashedly accepts.

Cultural nationalist visions of solidarity would lend support to immigration and immigrant policies that give weight to linguistic and ethnic preferences and impose special requirements on individuals from groups deemed to be outside the nation's "core culture." One example is the practice in postwar Germany of giving priority in immigration and naturalization policy to ethnic Germans; they were the only foreign nationals who were accepted as permanent residents set on the path toward citizenship. They were treated not as immigrants but "resettlers" (Aussiedler) who acted on their constitutional right to return to their country of origin. In contrast, non-ethnically German guestworkers (Gastarbeiter) were designated as "aliens" (Auslander) under the 1965 German Alien Law and excluded from German citizenship. 26 Another example is the Japanese naturalization policy that, until the late 1980s, required naturalized citizens to adopt a Japanese family name. The language requirement in contemporary naturalization policies in the West is the leading remaining example of a cultural nationalist integration policy; it reflects not only a concern with the economic and political integration of immigrants but also a nationalist concern with preserving a distinctive national culture.

Constitutional patriotism and liberal nationalism are accounts of civic solidarity that deal with what one might call first-level diversity. Individuals have different group identities and hold divergent moral and religious outlooks, yet they are expected to share the same idea of what it means to be American: either patriots committed to the same set of ideals or co-nationals sharing the relevant cultural attributes. Charles Taylor suggests an alternative approach, the idea of "deep diversity." Rather than trying to fix some minimal content as the basis of solidarity, Taylor acknowledges not only the fact of a diversity of group identities and outlooks (first-level diversity), but also the fact of a diversity of ways of belonging to the political community (second-level or deep diversity). Taylor introduces the idea of deep diversity in the context of discussing what it means to be Canadian:

Someone of, say, Italian extraction in Toronto or Ukrainian extraction in Edmonton might indeed feel Canadian as a bearer of individual rights in a multicultural mosaic. . . . But this person might nevertheless accept that a Québécois or a Cree or a Déné might belong in a very different way, that these persons were Canadian through being members of their national communities. Reciprocally, the Québécois, Cree, or Déné would accept the perfect legitimacy of the "mosaic" identity.

Civic solidarity or political identity is not "defined according to a concrete content," but, rather, "by the fact that everybody is attached to that identity in his or her own fashion, that everybody wants to continue that history and proposes to make that community progress." 27 What leads people to support second-level diversity is both the desire to be a member of the political community and the recognition of disagreement about what it means to be a member. In our world, membership in a political community provides goods we cannot do without; this, above all, may be the source of our desire for political community.

Even though Taylor contrasts Canada with the United States, accepting the myth of America as a nation of immigrants, the United States also has a need for acknowledgment of diverse modes of belonging based on the distinctive histories of different groups. Native Americans, African Americans, Irish Americans, Vietnamese Americans, and Mexican Americans: across these communities of people, we can find not only distinctive group identities, but also distinctive ways of belonging to the political community.

Deep diversity is not a recapitulation of the idea of cultural pluralism first developed in the United States by Horace Kallen, who argued for assimilation "in matters economic and political" and preservation of differences "in cultural consciousness." 28 In Kallen's view, hyphenated Americans lived their spiritual lives in private, on the left side of the hyphen, while being culturally anonymous on the right side of the hyphen. The ethnic-political distinction maps onto a private-public dichotomy; the two spheres are to be kept separate, such that Irish Americans, for example, are culturally Irish and politically American. In contrast, the idea of deep diversity recognizes that Irish Americans are culturally Irish American and politically Irish American. As Michael Walzer put it in his discussion of American identity almost twenty years ago, the culture of hyphenated Americans has been shaped by American culture, and their politics is significantly ethnic in style and substance. 29 The idea of deep or second-level diversity is not just about immigrant ethnics, which is the focus of both Kallen's and Walzer's analyses, but also racial minorities, who, based on their distinctive experiences of exclusion and struggles toward inclusion, have distinctive ways of belonging to America.

While attractive for its inclusiveness, the deep diversity model may be too thin a basis for civic solidarity in a democratic society. Can there be civic solidarity without citizens already sharing a set of values or a culture in the first place? In writing elsewhere about how different groups within democracy might "share identity space," Taylor himself suggests that the "basic principles of republican constitutions – democracy itself and human rights, among them" constitute a "non-negotiable" minimum. Yet, what distinguishes Taylor's deep diversity model of solidarity from Habermas's constitutional patriotism is the recognition that "historic identities cannot be just abstracted from." The minimal commonality of shared principles is "accompanied by a recognition that these principles can be realized in a number of different ways, and can never be applied neutrally without some confronting of the substantive religious ethnic-cultural differences in societies." 30 And in contrast to liberal nationalism, deep diversity does not aim at specifying a common national culture that must be shared by all. What matters is not so much the content of solidarity, but the ethos generated by making the effort at mutual understanding and respect.

Canada's approach to the integration of immigrants may be the closest thing there is to "deep diversity." Canadian naturalization policy is not so different from that of the United States: a short required residency period, relatively low application fees, a test of history and civics knowledge, and a language exam. 31 Where the United States and Canada diverge is in their public commitment to diversity. Through its official multiculturalism policies, Canada expresses a commitment to the value of diversity among immigrant communities through funding for ethnic associations and supporting heritage language schools. 32 Constitutional patriots and liberal nationalists say that immigrant integration should be a two-way process, that immigrants should shape the host society's dominant culture just as they are shaped by it. Multicultural accommodations actually provide the conditions under which immigrant integration might genuinely become a two-way process. Such policies send a strong message that immigrants are a welcome part of the political community and should play an active role in shaping its future evolution.

The question of solidarity may not be the most urgent task Americans face today; war and economic crisis loom larger. But the question of solidarity remains important in the face of ongoing large-scale immigration and its effects on intergroup relations, which in turn affect our ability to deal with issues of economic inequality and democracy. I hope to have shown that patriotism is not easily separated from nationalism, that nationalism needs to be evaluated in light of shared principles, and that respect for deep diversity presupposes a commitment to some shared values, including perhaps diversity itself. Rather than viewing the three models of civic solidarity I have discussed as mutually exclusive – as the proponents of each sometimes seem to suggest – we should think about how they might be made to work together with each model tempering the excesses of the others.

What is now formally required of immigrants seeking to become American citizens most clearly reflects the first two models of solidarity: professed allegiance to the principles of the Constitution (constitutional patriotism) and adoption of a shared culture by demonstrating the ability to read, write, and speak English (liberal nationalism). The revised citizenship test makes gestures toward respect for first-level diversity and inclusion of historically marginalized groups with questions such as, "Who lived in America before the Europeans arrived?" "What group of people was taken to America and sold as slaves?" "What did Susan B. Anthony do?" "What did Martin Luther King, Jr. do?" The election of the first African American president of the United States is a significant step forward. A more inclusive American solidarity requires the recognition not only of the fact that Americans are a diverse people, but also that they have distinctive ways of belonging to America.

- 1 For comments on earlier versions of this essay, I am grateful to participants in the Kadish Center Workshop on Law, Philosophy, and Political Theory at Berkeley Law School; the Penn Program on Democracy, Citizenship, and Constitutionalism; and the UCLA Legal Theory Workshop. I am especially grateful to Christopher Kutz, Sarah Paoletti, Eric Rakowski, Samuel Scheffler, Seana Shiffrin, and Rogers Smith.

- 2 Philip Gleason, "American Identity and Americanization," in Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups , ed. Stephan Thernstrom (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press, 1980), 31–32, 56–57.

- 3 David Hollinger, "From Identity to Solidarity," Dædalus 135 (4) (Fall 2006): 24.

- 4 David Miller, "Multiculturalism and the Welfare State: Theoretical Reflections," in Multiculturalism and the Welfare State: Recognition and Redistribution in Contemporary Democracies , ed. Keith Banting and Will Kymlicka (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 328, 334.

- 5 Charles Taylor, "Why Democracy Needs Patriotism," in For Love of Country? ed. Joshua Cohen (Boston: Beacon Press, 1996), 121.

- 6 On the purpose and varieties of narratives of collective identity and membership that have been and should be articulated not only for subnational and transnational, but also for national communities, see Rogers M. Smith, Stories of Peoplehood: The Politics and Morals of Political Membership (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003).

- 7 Jürgen Habermas, "Citizenship and National Identity," in Between Facts and Norms: Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy , trans. William Rehg (Cambridge, Mass.: mit Press, 1996), 500.

- 9 Edward Rothstein, "Connections: Refining the Tests That Confer Citizenship," The New York Times , January 23, 2006.

- 10 See http://www.uscis.gov/files/nativedocuments/100q.pdf (accessed November 28, 2008).

- 11 Habermas, "The European Nation-State," in Between Facts and Norms , trans. Rehg, 118.

- 12 Charles Taylor, "The Politics of Recognition," in Multiculturalism: Examining the Politics of Recognition , ed. Amy Gutmann (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994); Will Kymlicka, Multicultural Citizenship: A Liberal Theory of Minority Rights (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995).

- 13 8 U.S.C., section 1423 (1988); In re Katz , 21 F.2d 867 (E.D. Mich. 1927) (attachment to principles of Constitution implies English literacy requirement).

- 14 Act of Mar. 26, 1790, ch. 3, 1 Stat., 103 and Act of Jan. 29, 1795, ch. 20, section 1, 1 Stat., 414. See James H. Kettner, The Development of American Citizenship , 1608–1870 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1984), 239–243. James Madison opposed the second requirement: "It was hard to make a man swear that he preferred the Constitution of the United States, or to give any general opinion, because he may, in his own private judgment, think Monarchy or Aristocracy better, and yet be honestly determined to support his Government as he finds it"; Annals of Cong. 1, 1022–1023.

- 15 8 U.S.C., section 1427(a)(3). See also Schneiderman v. United States , 320 U.S. 118, 133 n.12 (1943), which notes the change from behaving as a person attached to constitutional principles to being a person attached to constitutional principles.

- 16 Internal Security Act of 1950, ch. 1024, sections 22, 25, 64 Stat. 987, 1006–1010, 1013–1015. The Internal Security Act provisions were included in the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, ch. 477, sections 212(a)(28), 241(a)(6), 313, 66 Stat. 163, 184–186, 205–206, 240–241.

- 17 Gerald L. Neuman, "Justifying U.S. Naturalization Policies," Virginia Journal of International Law 35 (1994): 255.

- 18 David Miller, On Nationality (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), 25.

- 19 Ibid., 25–26.

- 20 On the civic-ethnic distinction, see W. Rogers Brubaker, Citizenship and Nationhood in France and Germany (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1992); David Hollinger, Post-Ethnic America: Beyond Multiculturalism (New York: Basic Books, 1995); Michael Ignatieff, Blood and Belonging: Journeys into the New Nationalism (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1995); Yael Tamir, Liberal Nationalism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993).

- 21 Anthony D. Smith, The Ethnic Origins of Nations (Oxford: Blackwell, 1986), 216.

- 22 See Rogers M. Smith, Civic Ideals: Conflicting Visions of Citizenship in U.S. History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997).

- 23 Miller, On Nationality , 122–123, 153–154.

- 24 Samuel P. Huntington, Who Are We? The Challenges to America's National Identity (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004), 12. In his earlier book, American Politics: The Promise of Disharmony (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press, 1981), Huntington defended a "civic" view of American identity based on the "political ideas of the American creed," which include liberty, equality, democracy, individualism, and private property (46). His change in view seems to have been motivated in part by his belief that principles and ideology are too weak to unite a political community, and also by his fears about immigrants maintaining transnational identities and loyalties – in particular, Mexican immigrants whom he sees as creating bilingual, bicultural, and potentially separatist regions; Who Are We? 205.

- 25 Huntington, Who Are We? 31, 20.

- 26 Christian Joppke, "The Evolution of Alien Rights in the United States, Germany, and the European Union," Citizenship Today: Global Perspectives and Practices , ed. T. Alexander Aleinikoff and Douglas Klusmeyer (Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2001), 44. In 2000, the German government moved from a strictly jus sanguinis rule toward one that combines jus sanguinis and jus soli , which opens up access to citizenship to non-ethnically German migrants, including Turkish migrant workers and their descendants. A minimum length of residency of eight (down from ten) years is also required, and dual citizenship is not formally recognized. While more inclusive than before, German citizenship laws remain the least inclusive among Western European and North American countries, with inclusiveness measured by the following criteria: whether citizenship is granted by jus soli (whether children of non-citizens who are born in a country's territory can acquire citizenship), the length of residency required for naturalization, and whether naturalized immigrants are permitted to hold dual citizenship. See Marc Morjé Howard, "Comparative Citizenship: An Agenda for Cross-National Research," Perspectives on Politics 4 (2006): 443–455.

- 27 Charles Taylor, "Shared and Divergent Values," in Reconciling the Solitudes: Essays on Canadian Federalism and Nationalism , ed. Guy Laforest (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1993), 183, 130.

- 28 Horace M. Kallen, Culture and Democracy in the United States (New York: Boni & Liveright, 1924), 114–115.

- 29 Michael Walzer, "What Does It Mean to Be an 'American'?" (1974); reprinted in What It Means to Be an American: Essays on the American Experience (New York: Marsilio, 1990), 46.

- 30 Charles Taylor, "Democratic Exclusion (and Its Remedies?)," in Multiculturalism, Liberalism, and Democracy , ed. Rajeev Bhargava et al. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 163.

- 31 The differences in naturalization policy are a slightly longer residency requirement in the United States (five years in contrast to Canada's three) and Canada's official acceptance of dual citizenship.

- 32 See Irene Bloemraad, Becoming a Citizen: Incorporating Immigrants and Refugees in the United States and Canada (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006.

What Does it Mean to be an American? Reexamining the Rights and Responsibilities of Citizenship

- Abortion & Reproductive Health

- Climate Change & Science

- Immigration

- Law & Criminal Justice

- Politics & Elections

- Race & Ethnicity

- Religion & Culture

- Family Religious Dynamics and Interfaith Relationships

- Faith, Politics, and Environmental Stewardship: Identity, Religiosity, and Malleability in Americans’ Climate Change Attitude

- Careers and Fellowships

- Current PRRI Public Fellows

- PRRI Public Fellow Alumni

- Partnerships

- Press Coverage

- PRRI Voices

Our current political polarization can feel new, but it has a long cultural history. Two dominant visions of American identity have historically been in tension and at times outright competition with one another: pluralism and exclusion.

On the one hand, the first vision understands the United States as a country built on a commitment to pluralism, where anyone, from anywhere, can be American. As people fled religious persecution, the US as a nation of immigrants provided many a home where diverse religious and political views and backgrounds could co-exist. In this broad sense, the country affirms its society is a land of others. These ideals laid out by the Framers of the Constitution have over the centuries been invoked by groups marginalized by race, religion, and immigrant backgrounds to argue for a more inclusive, representative American democracy.

On the other hand, the exclusionary vision of American society has emphasized that American identity–and all the idealized or normative standards that entails (e.g., race, gender)–is not available to all. Historically, what it means to be American has been exclusively available to white people – white men in particular – with European ancestry , both in how people imagine American identity and how law has enforced boundaries of citizenship. For example, when Asian Americans and Latino Americans made legal claims for citizenship in the 19th and early 20th century, they were forced to argue that they fit either ‘white’ or ‘black’ definitions of citizenship. Both during this period and since, citizenship held by immigrants and/or racialized minorities is insufficient to be considered “American.”

Given this tension between a cultural value for pluralism and narrow notions of American identity, how does the public understand what it means to be “truly American” and are these views changing?

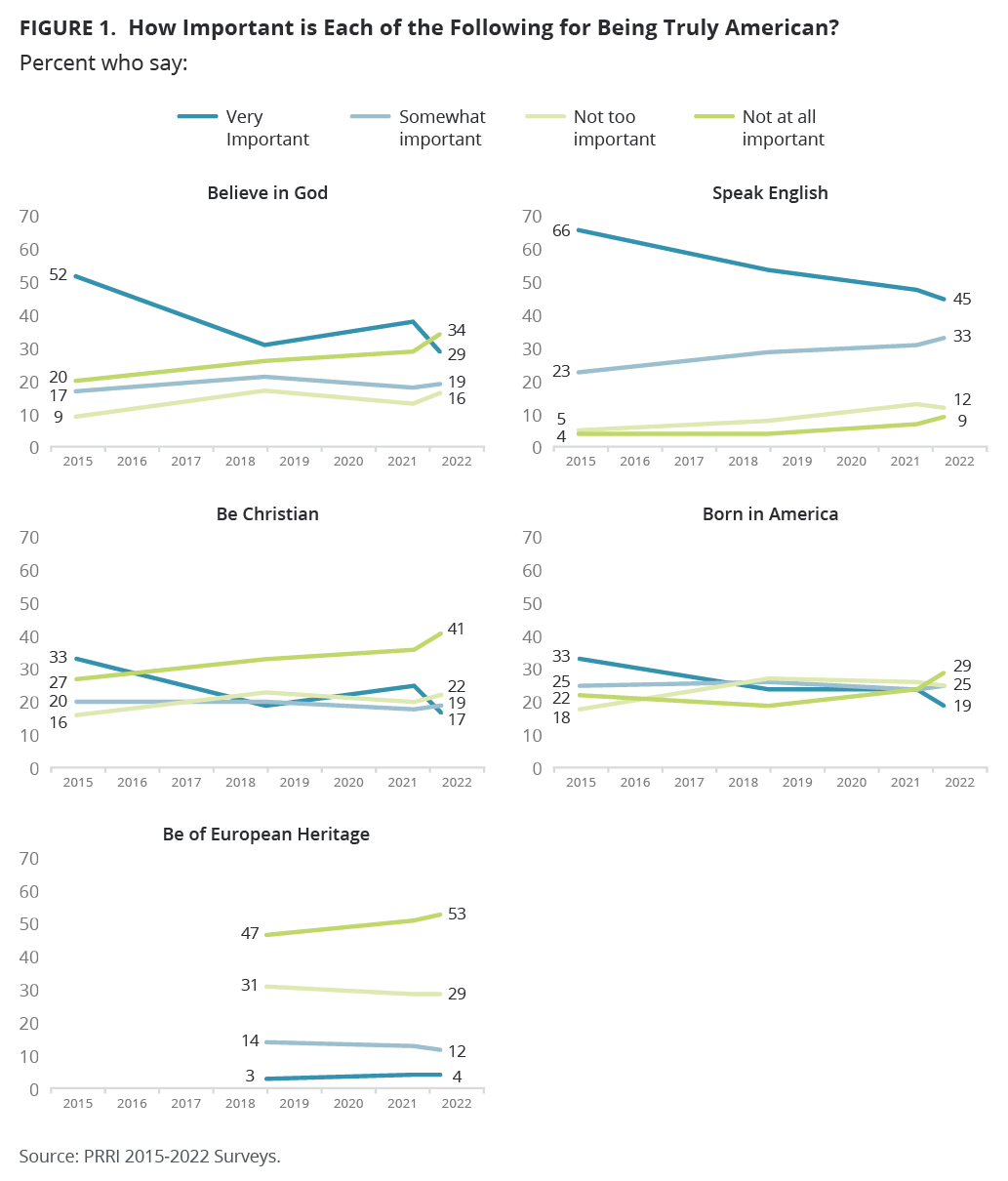

Since 2015, PRRI has asked questions about the hard boundaries of American identity on four occasions. This battery of questions assesses how important the following factors are to being “truly” American: being a Christian, being born in America, being able to speak English, and believing in God. Since 2018, PRRI has included a question about whether being of European heritage is important to being “truly” American.

We examined attitudes about each of these items on a cross-section of Americans in 2015, 2018, 2021, and 2022.

Second, most Americans place the greatest importance on English language skills as the most important factor of the five posed to being truly American, whereas being of European heritage is the least important of the five factors.

Finally, while these trends suggest slight movement toward inclusion, they also show that many people still believe that religious identities and beliefs, language, and place of birth dictate who counts as a true American to some degree. Rates of moderate agreement with these questions are more stable over time.

Together, this snapshot suggests that the tension between the pluralist and exclusionary traditions endure. While the over time trend suggests a move towards a more pluralist vision, the majority of Americans still believe that these hard boundaries of American identity and the exclusionary vision that they support define what it means to be a true American.

Today, some Americans believe that speaking English and holding particular kinds of religious beliefs are central to American identity. These beliefs are tied to citizenship and denied to religious minorities . National political rhetoric often underscores the reality of this vision of America. National identity is regularly invoked in American politics, often to turn public opinion away from progressive immigration policies. Politicians regularly contrast American citizens with immigrants, arguing that their cultures and religions are incompatible with American values and that they will never be “true Americans.” Research also shows that people do not always choose a pluralist or an exclusive vision of American society – their attitudes toward different social groups often combine parts of both visions .

Nazita Lajevardi , Evan Stewart , Roy Whitaker , and Tarah Williams are members of the 2021-2022 cohort of PRRI Public Fellows.

Morning Buzz New Research Research Roundup

American and national identity

We the People: a millennium of American identities

How have we defined who is an American? Who have we left out?

Teaching Guides

Questions for looking closely and thinking critically, images to download, and more.

- Benny Andrews, Flag Day

- Thomas Cole, The Hunter's Return

- Mississippian shell gorget

All videos + essays for this theme

c. 1250–1350 America before Columbus: a Mississippian view of the cosmos

Found marking the grave of an important individual, this gorget was worn as a neck ornament during life.

c. 1790 Fashioning diplomacy: the Anishinaabe, Britain, and 18th-century America

This outfit was likely made for a British lieutenant and gifted to him in a ritual exchange to show mutual respect.

1801 Rembrandt Peale, Rubens Peale with a Geranium

An unusual double portrait: a botanist and his geranium.

1842 Thomas Cole, The Voyage of Life

Cole’s extraordinary series chronicles each stage of human life: childhood, youth, manhood, and old age.

1845 Wilderness, settlement, and American identity, Thomas Cole's The Hunter's Return

Cole feared for the American landscape as his country expanded westward.

1848 Before the Civil War, the Mexican-American War as prelude

Painted for a divided US, people from North and South could identify with this image—others remain marginalized.

The Mexican-American War American Art in context

There is no memorial to the Mexican-American War in Washington, D.C.—a war in which more than 15,000 American soldiers lost their lives.

1857 Jasper Francis Cropsey, Mount Jefferson, Pinkham Notch, White Mountains

Summer, autumn, a saw mill all provide metaphors about American republicanism in this pre-Civil War landscape

1863 Representing freedom during the Civil War

This remarkable work honors those who fought for their own freedom, but acknowledges that the struggle goes on.

before 1870 The power of the bear and the story an American massacre

Six bears were required to create this necklace, meant to imbue the Pawnee chief with protection and power.

1895 The closing of the frontier and Remington's The Fall of the Cowboy

Remington mourns the decline of the cowboy by depicting the very thing that destroyed his iconic lifestyle.

c. 1925 Cities and pueblos: the search for an authentic America

The Southwest became a hub for artists seeking “quintessentially American” subjects beyond New York and Chicago.

1927 Georgia O'Keefe, Radiator Building—Night, New York

O'Keeffe takes on the New York skyline in the 1920s

1928 Strange Worlds, immigrant experience in the early 20th century

Geller captures the tensions of the Jewish immigrant experience in the early 20th-century United States.

c. 1930s Pottery and tourism: Pueblo culture and the lure of the Southwest

Nampeyo found inspiration from the old to create a pottery style that was entirely new and highly sought after.

1939 Revisiting the myth of George Washington and the cherry tree with Grant Wood

Wood infuses a famous folktale about George Washington with theatricality, humor, and a Gilbert Stuart sample.

1948 Harlem 1948, Ralph Ellison, Gordon Parks and the photo essay

Gordon Parks and the writer Ralph Ellison collaborated to show that Harlem is everywhere.

1954–55 Icon and irony: Jasper Johns, Flag

The American flag is a potent symbol that has different meanings for different viewers.

1958 From wire to weightlessness: Ruth Asawa, Untitled

Asawa was interned in World War II, but we must be careful about interpreting her artworks as related to that trauma.

1966 Identity and civil rights in 1960s America

Does the figure emerge from the stripes of the flag, or do they imprison him?

1967 Romare Bearden, Three Folk Musicians

Bearden thought about painting like music.

2011 United States Federal Building and Courthouse

This federal building inspires discussion over neoclassical architecture's ties to the ideals of democracy and contemporary American politics.

2014 Speaking to past and present, Clarissa Rizal’s Resilience Robe

This prestigious garment follows a traditional design passed down through generations of indigenous Alaskans.

2014 Wendy Red Star, 1880 Crow Peace Delegation

Red Star annotated photographs to restore dignity and context to government-issue photographs of Crow chiefs.

2015 Nari Ward, We the People (black version)

Hundreds of shoelaces form just three words. Here, the artist takes an abstract idea and makes it immediate.

2023 Kerry James Marshall, Now And Forever ; Elizabeth Alexander, "American Song," Washington National Cathedral

Kerry James Marshall and Elizabeth Alexander create words and images that fill the Washington National Cathedral with hope.

The Constitution of the United States (detail), 1787 (National Archives)

“We the People.”

Essay by dr. bryan zygmont.

Thus begins the Preamble to the United States Constitution. And though this phrase be only three words, it is a complicated and ever-shifting expression. Indeed, who are “We the People” (today) and who have “We the People” been (over the past millennium)?

The close study of art can do much to answer this question, but one must proceed with extreme caution. Traditionally, the study of the art made in North America has largely involved the examination of painting and sculpture commissioned by the only group affluent enough to pay for such works: wealthy white men. The study of eighteenth-century art from the American Colonies is an excellent case in point. To look only at the artistic record, one might assume North America was predominantly populated by wealthy, well-dressed men of European heritage. If we broaden the lens of our examination—that is, if we look at art that extends beyond the painting and sculpture that was restricted to the elite—we see the ways the artistic record is filled with works from a panoply of peoples: those who were native to North America, and from peoples from both sides of the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. These works have much to say about the shifting nature of national identity.

Mississippian culture

Gorget, c. 1250-1350, probably Middle Mississippian Tradition, whelk shell, 10 x 2 cm (National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, 18/853)

The Mississippian gorget (c. 1300 C.E.) is an excellent point of departure. A gorget is an ornament meant to be worn around the neck. This small object, carved out of shell likely brought from the Gulf of Mexico, was discovered at the end of the nineteenth century by an amateur archaeologist in a burial site in what is now north-central Tennessee. It is an object that speaks to the civilization, world views, and identity of the culture that made it, and those cultures with which it was in close contact.

The body of the intricately incised figure has been contorted to fit within the constraints of the round shape. The figure’s right knee is raised in front of him, while his left knee is similarly bent behind him, as if to suggest he is running. He holds a mace—a kind of weapon—in his left hand, while in his right he holds a decapitated human head. The fork-shaped form around his eye suggests the markings of a peregrine falcon, an element commonly seen in similar gorgets. He displays beads, both on his necklace and around his legs, and he also wears an elaborate headdress and decorated loincloth around his waist. The iconography of this object suggests the figure is Morning Star—who astronomically corresponds with Venus—a hero figure, who, with his twin brother, retrieved his father’s remains from the underworld. That similar figures have been found all over the large Mississippi Valley—and in a variety of media—tells us important things about pre-Columbian cultures in North America.

To begin an examination of this object, we need to displace some (likely) preconceived notions about pre-Columbian cultures in North America. When we speak of groups of Native Americans, we sometimes use the archaic term “tribes,” a word that seems to suggest a sense of isolation and separation. Moreover, when we think of the date of this object—it was made about 700 years ago—we might believe that the Mississippi Valley was an untamed wilderness, devoid of hamlets or towns. In fact, neither of these notions are necessarily true. As the Spanish conquistador Hernando de Sota observed between 1539-42, North America was filled with cities of various sizes. For example, the original Mississippian town, Cahokia, had a population of around 30,000 early in the second millennium, a size that was roughly equal to that of London at the same time. Clearly, any city of this size was multi-ethnic in nature and contained groups of different “tribes.” It also must have had contact with communities far beyond its own borders. Indeed, the Mississippian gorget is not an object about a single “tribe” that roamed the North American wilderness. Instead, it is a work that eloquently speaks about the ways in which different cultures lived in complex civilizations with firmly established belief systems before the first Europeans arrived.

Fashioning diplomacy: an Anishinaabe outfit

Anishinaabe outfit, c. 1790, collected by Lieutenant Andrew Foster, Fort Michilimackinac (British), Michigan, Birchbark, cotton, linen, wool, feathers, silk, silver brooches, porcupine quills, horsehair, hide, sinew; the moccasins were likely made by the Huron–Wendat people (National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution)

It would be inaccurate, of course, to assume that these disparate groups of Native Americans shunned contact with Europeans once they began to settle North America, and there is a perception that these two groups, from different sides of the Atlantic Ocean, were in constant conflict. In fact, these two groups often peacefully coexisted, deriving at least some mutual benefit. One might even suggest that in certain cases friendships formed. And like friendships today, these relationships centuries ago might prompt gift exchanges. The Anishinaabe outfit from the National Museum of the American Indian is one such gift. But this is no simple token of friendship. Instead, it is a powerful and forceful testament to trans-world mercantilism and trade, and the complex diplomatic relationships between world powers.

At first glance one might assume that this Native American outfit was intended for a Native American wearer. Instead, it was a gift to Andrew Foster, a lieutenant in the British army who served in the Great Lakes area—in what is now Michigan—around the year 1790. The end of the eighteenth century was a complicated time in the history of the United States. The Treaty of Paris, signed on 3 September 1783, officially ended the American Revolutionary War. Moreover, New Hampshire ratified the Constitution in June 1788, and the government of the United States formally began less than a year later on 4 March 1789. In an attempt to protect their North American interests, Great Britain searched out diplomatic relationships with various Native American groups in the Great Lakes area to buffer the approach of the ever-growing United States that was already eyeing westward expansion.

Clearly, about the time this extravagant outfit was made—and presented to a British army officer—the United States was very much attempting to figure out its place in the world, to say nothing of its place in North America. Six years after the close of the War of American Independence, the British army was still fully entrenched in the Great Lakes area and actively engaged in trade and diplomatic relationships with the Anishinaabe peoples who lived there. Although we are looking only at an Anishinaabe outfit given to a British officer, we can easily imagine British tokens of friendship being given to the leadership of the Anishinaabe peoples, too.

Anishinaabe outfit (detail), c. 1790, collected by Lieutenant Andrew Foster, Fort Michilimackinac (British), Michigan, Birchbark, cotton, linen, wool, feathers, silk, silver brooches, porcupine quills, horsehair, hide, sinew; the moccasins were likely made by the Huron–Wendat people (National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution)

A close examination of these garments points to the ways in which the eighteenth century was a time of long-distance commerce and trade. Great Britain became one of the world’s foremost mercantile powers, so much so that after the conclusion of the Seven-Years’ War (also referred to as the French and Indian War), the Irish-born British Statesman George Macartney wrote that Great Britain had become “the vast empire on which the sun never sets.” A fine illustration of this point is the shirt. The cotton for this shirt was grown in India—a British territory at the end of the eighteenth century—and then exported to Great Britain where the cloth was milled and manufactured into the cloth from which the shirt was made. The cut of the garment and the floral decoration were intended to appeal to a Native American audience. In short, this cotton shirt has had a multi-continent life. The cotton was grown in India, made into a shirt in England, exported to North America, and then returned to Britain when Foster returned home.

Other elements—such as the glass beads that decorate the necklace—are European made but designed to look as if they were manufactured in North America. These Venetian glass beads have been made to resemble wampum, a material Native Americans traditionally made from shells. Still other elements suggest trade between different groups of Native Americans. For example, the intricately decorated deerskin moccasins are not of Anishinaabe origin, but were instead made by women of the Huron-Wendat Nation and subsequently traded with Anishinaabe peoples. Like the Mississippian Gorget, Andrew Foster’s outfit eloquently speaks to intertribal commerce, exchange, and cooperation.

Wilderness, settlement, and American identity

Thomas Cole, The Hunter’s Return , 1845, oil on canvas (Amon Carter Museum of American Art)

If these first two works of art—the Mississippian Gorget and the Anishinaabe outfit—involve Native Americans both before and after the arrival of European settlers, Thomas Cole’s The Hunter’s Return (1845) is very much about that act of settlement by those Europeans. Although born in England, Cole moved to the United States when a teenager and is most well-known today for his landscapes that depict the Hudson River Valley of New York. In this autumnal landscape, the inclusion of the human figures and their domicile points to the westward expansion of the United States during the middle of the nineteenth century.

It is unlikely that Cole depicts a specific location in The Hunters Return . A log cabin—complete with smoke billowing from the chimney—can be observed on the right side of the composition, and a small garden is located just to its left. We see seven figures: the hunters of the title include the two men on the left side of the composition carrying the recently killed stag, and the young boy carrying the rifle over his shoulder who walks along the path towards the log cabin. Those who stayed behind include the two adult women (one of whom holds up an infant), and another young boy who embraces a dog, one that presumably was out with the hunting party. This multi-generational family suggests that they have lived here for a while, and the presence of a permanent structure such as a log cabin indicates that they will remain for some time to come, too.

Manifest Destiny

One can easily imagine what this scene may have looked like fifty years before Cole painted it. There would have been no log cabin, there would have been no human figures—and if they were there, they would not have been of European descent—and there would have been no felled trees or tree stumps to show the evidence of the saw (as we see in the lower right corner of the painting and between the garden and the log cabin). But by the middle third of the nineteenth century, there was an underlying notion in the United States that God placed Europeans in North America in order to settle the land and make it useful. No writer more forcefully expressed this than did John L. O’Sullivan, who in the July-August 1845 issue of the Democratic Review wrote that it was “our manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions.”

It is interesting to note that the first use of this term—Manifest Destiny, which would in time acquire Proper Noun status—was in 1845, the very year Cole completed The Hunters Return . Thus, Cole’s painting is not merely a composition about several hunters returning to their homestead after a successful hunt. Instead, it is a visual declaration of the political ideology of the process of (and results of) Manifest Destiny.

The middle of the nineteenth century in the United States was not only about westward expansion, it was also troubled by the brewing social, economic, and political turmoil growing between the North and the South in the ever-expanding country. The use of the first-person “our” in the O’Sullivan’s phrase “our manifest destiny” is as ambiguous as the first-person “we” in the “We the People” opening of the United States Constitution. It was clear by the middle of the nineteenth century that the “we” of “We the People” was restricted to the (white) people of European descent, not the Native Americans who predated European settlers by millennia or the African-Americans who had been enslaved here for generations.

Representing freedom during the Civil War

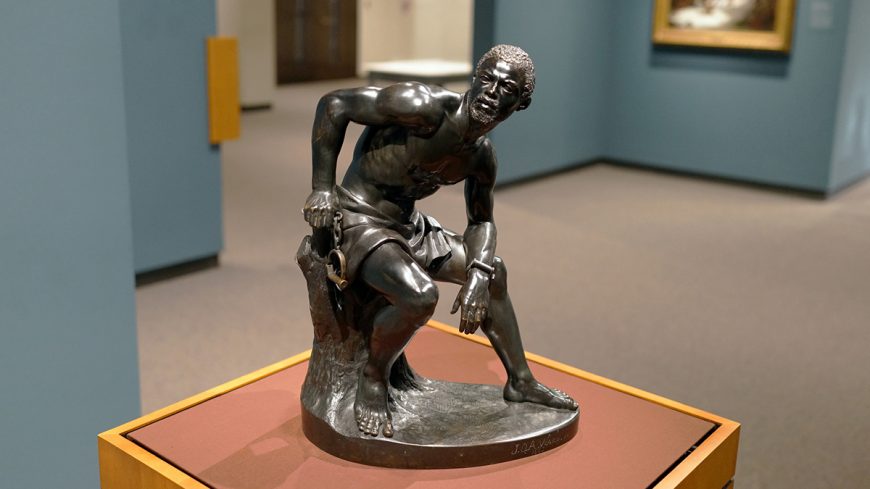

John Quincy Adams Ward, The Freedman , 1863, bronze (Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas)

The artist John Quincy Adams Ward cast The Freedman in 1863 during the middle of the American Civil War (1861-65). This creation date is important, for this object has strong ties to Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation.

The Emancipation Proclamation

On 22 September 1862, Lincoln issued a warning that he would free every slave in the states that did not end their rebellion against the Union. This was in strident opposition to the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 that stipulated that all slaves who escaped to free states must be returned to their captors, and the Dred Scott vs. Sandford decision of 1857 which stated that slaves were not citizens but instead only constitutionally protected property of their masters.

When the Civil War was still in full swing on 1 January 1863—and no slave state had withdrawn from the Confederacy and rejoined the Union—Lincoln issued the formal Emancipation Proclamation. In it, Lincoln wrote, “And by the virtue of the power, and for the purpose aforesaid, I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of states, are, and henceforward shall be free; and that the Executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons.”

What Ward has so elegantly cast is the tangible and human result of Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. An idealized and nude-to-the-waist African American male sits atop a tree stump, looking to his right with a sense of intense concentration on his face. His left forearm rests upon his left knee, and we can clearly see a manacle still in place around his left wrist. In contrast, he holds in his right hand the links to a manacle that once bound his two hands together. The juxtaposition of these two manacles—one still attached to the wrist, the other recently removed—suggests the ways in which his freedom has also not yet been fully accomplished.

While the Emancipation Proclamation may have freed this man, it hardly gave him freedom. It was not until the ratification of the 13th Amendment on 6 December 1865 that the practice of slavery was formerly abolished in the United States. But although the 13th Amendment only ended slavery, it did not necessarily provide citizenship, something that was only accomplished in July 1868 when the ratification of the 14th Amendment provided citizenship to all born in the United States. But even still, this was not the end of the road. For there are citizens, and there are citizens who can vote. And it was not until February 1870 when the ratified 15th Amendment—“The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridge by the United States or by any State on the account of race, color, ore previous condition of servitude”—provided male African-Americans with full enfranchisement (at least in theory). And it was not until the 19th Amendment was ratified in 1920 that women of any ethnicity were allowed the right to vote.

“Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free”

Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi (sculptor), Gustave Eiffel (interior structure), Richard Morris Hunt (base), Statue of Liberty, begun 1875, dedicated 1886, copper exterior, 151 feet 1 inch / 46 m high (statue), New York Harbor

One of the most recognizable works of art in the history of the United States is the Statue of Liberty . Although it was formally dedicated on 28 October 1886, a poem—written three years earlier by Emma Lazarus—was engraved onto a bronze plaque and placed inside the lower level of the statue’s pedestal in 1903. It reads, in part:

From her beacon-hand Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame. “Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, The wretched refuse of your teeming shore. Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me, I lift my lamp beside the golden door!” Emma Lazarus, from The New Colossus , 1883

By 1903, Ellis Island was the busiest immigration inspection station through which aspiring citizens-to-be could enter the United States. Of course, immigration was not a new thing—the United States has always been a country populated by immigrants and the descendants of those immigrants—but immigration into the United States during the decades surrounding the turn of the twentieth century was particularly robust. It was during this time when the tired, the poor, the huddled masses yearning to breathe free most flocked to the United States. The Statue of Liberty stood tall to welcome them to their American Dream.

The Johnson-Reed Act

Then, as now, the topic of immigration was a complicated political topic. For example, the Immigration Act of 1924—sometimes called the Johnson-Reed Act—was passed to restrict the flow of potential immigrants from targeted parts of Europe. In an attempt to ensure that “America must remain American,” this act proposed an annual limit to the number of immigrants from each country to 2% of the number of people already living in the United States from that country. For those countries with a high immigration population already living in the United States—nations such as England and Germany—this act would have had little real practical effect (two percent of an enormous number is still a big number). For other countries—such as predominantly Catholic Italy, and those in Eastern Europe with a large Jewish population—this law severely restricted who could pursue the American Dream. At its core, the Johnson-Reed Act was an attempt to manipulate and control what future Americans would look like and what Americans believed (their religious faith).

Strange Worlds , immigrant experience in the early 20th century

Todros Geller, Strange Worlds , 1928, oil on canvas, 71.8 x 66.4 cm (Art Institute of Chicago)

Todros Geller painted Strange Worlds in 1928, just four years after the passage of the Johnson-Reed Act. Geller was an immigrant himself, having fled the pogroms (organized massacres of the Jews in Eastern Europe) in Ukraine, in 1906. He settled in Montreal, and then moved to the United States in 1918 and studied at the Art Institute of Chicago. This city had been a hotbed of immigration from Eastern Europe for decades. One only need recall Jurgis Rudkus, the Lithuanian immigrant in Upton Sinclair’s novel, The Jungle (1906) to be reminded of the incredible melting pot Chicago had become.

In Strange Worlds , Geller gives us a visual representation of what the immigrant experience might have been for those living in Chicago during the early decades of the twentieth century, and the plurality of that title— Strange Worlds , not Strange World—speaks to the difficulty many had in coming to America. A solitary elderly man stares out at us from the left foreground, a tense, distant look on his face. With his dark hat and nondescript clothing, it is clear that this figure is not intended to be a portrait of a specific person. Instead, it is a representation of a type; in this instance, the type is that of the Eastern European immigrant. The compressed foreground is filled by the figure, a diagonal staircase leading upwards to one of Chicago’s elevated trains (a track of which can be seen in the distance, in the upper right corner), and a collage of newspapers. These two elements—the L and newspapers—would hardly have seemed strange to anyone living in Chicago at the time. But the figure’s wearied look and his own isolation makes clear that he is a foreigner in a foreign land.

If the foreground—the man’s own space—is static, and, one might say, comparatively traditional, then the background is much more dynamic and modern. The human figures and the landscape have been painted with a kind of kinetic energy that vibrates through the background. And this tension—between the man’s own space and that which surrounds him—was part of the immigrant experience for millions of new Americans. America was strange to them, and, as important, they were strange to (the) Americans (already here). Even if this man were granted citizenship and the right to vote, one gets the idea that he is not yet a part of “We the People.”

Nari Ward, We the People (black version) , 2015, shoelaces, 8 × 27 feet (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas)

E Pluribus Unum

In the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson wrote, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” Who qualified for these unalienable rights has shifted and changed over time, just as who has been included in “We the People” has changed, too. These changes and additions are part of our national identity, one that is also in a state of dynamic flux. But even though that identity may have changed, the idea of E Pluribus Unum —out of many, one—has remained constant in the United (an adjective that implies singularity) States (a plural noun).

Explore the diverse history of the United States through its art. Seeing America is funded by the Terra Foundation for American Art and the Alice L. Walton Foundation.

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!

Select one or multiple and then click Browse

Share this page with friends! Please add your recipient's email address below.

National Identity and Why It Matters

Reading: “The Man without a Country” By Edward Everett Hale

- 1. Introduction

- 2. THINKING ABOUT THE TEXT

- 3. THINKING WITH THE TEXT

- 4. ONLINE DISCUSSION

How To Use This Discussion Guide

Materials Included | Begin by reading Edward Everett Hale’s “ The Man without a Country ” on our site or in your copy of What So Proudly We Hail .

Materials for this guide include background information about the author and discussion questions to enhance your understanding and stimulate conversation about the story. In addition, the guide includes a series of short video discussions about the story, conducted by Wilfred McClay (Hillsdale College) with the editors of the anthology. These seminars help capture the experience of high-level discourse as participants interact and elicit meaning from a classic American text. These videos are meant to raise additional questions and augment discussion, not replace it.

Learning Objectives | Students will be able to:

- Explore the meaning and significance of national identity in general and American identity in particular, using the principles set out in the Declaration of Independence as background;

- Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it;

- Cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text;

- Determine central ideas or themes of a text and analyze their development;

- Summarize the key supporting details and ideas;

- Analyze how and why individuals, events, and ideas develop and interact over the course of a text;

- Interpret words and phrases as they are used in a text, including determining technical, connotative, and figurative meanings, and analyze how specific word choices shape meaning or tone;

- Analyze the structure of texts, including how specific sentences, paragraphs, and larger portions of the text (e.g., a section, chapter, scene, or stanza) relate to one another and the whole; and

- Delineate and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, including the validity of the reasoning and the relevance and sufficiency of the evidence.

Writing Prompts

- Is there anything especially American in the identity and attachment that Philip Nolan comes to desire? After reading “The Man without a Country,” write an essay that addresses the question and support your position with evidence from the text.

- Is the Civil War background important for understanding the meaning of “The Man without a Country”? After reading the story, write an explanatory essay that addresses the question and analyzes the reasons why it is—or isn’t—important to the story, providing examples to clarify your analysis. What conclusions or implications can you draw?

- Which is more important for making attached American citizens: the love of American principles or love of our native land? After reading “The Man Without a Country,” write an essay that compares these two forms of attachment and argues which one is important for making good citizens. Be sure to support your position with evidence from the text.

About the Author

It is probably no accident that Edward Everett Hale (1822–1909) was a lifelong American patriot. He was the nephew of Edward Everett, renowned orator and statesman. And his father, Nathan Hale, was the namesake and nephew of Nathan Hale, executed by the British for espionage during the Revolutionary War and famous for his last words: “I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country.”

As a Unitarian minister in Boston, as chaplain in the United States Senate, and as a prolific writer of essays and short fiction, Edward Everett Hale was a devoted activist, championing especially the causes of the abolition of slavery and the advancement of public education. “The Man without a Country,” his most famous story, was published anonymously in the Atlantic Monthly during the terrible days of Civil War, in 1863, the same year that President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation .

The video seminar helps capture the experience of high-level discourse as particpants interact and elicit meaning from classic American texts. To watch the full conversation, click here. Otherwise click below to continue.

Related Links

- A history of Edward Everett Hale and his family

- More stories by Edward Everett Hale

To watch the full conversation, click here.

The plot of Hale’s story is straightforward: Seduced, “body and soul,” by the charm and grand vision of Aaron Burr, young Philip Nolan, an ambitious artillery officer in the “Legion of the West,” becomes a Burr accomplice (2 – 3). Tried for treason, “Nolan was proved guilty enough” (3). Still, no one would have heard of him “but that, when the president of the court asked him at the close, whether he wished to say anything to show that he had always been faithful to the United States, Nolan cried out, in a fit of frenzy,—

‘D—n the United States! I wish I may never hear of the United States again!’”

His judges, half of them veterans of the Revolutionary War, are stunned. They decide to give him precisely what he has asked for: From that moment, September 23, 1807, until his dying day, May 11, 1863—nearly fifty-six years later—Nolan is literally, and figuratively, put out to sea. He never again sets foot on American soil; only as he is dying does he again hear anything about the United States. Yet during—and perhaps because of—his enforced separation from his native land, Nolan’s attitude toward her changes dramatically. The rest of the story powerfully shows how his transformation comes about.

Section Overview