Promoting Client Participation and Constructing Decisions in Mental Health Rehabilitation Meetings

- First Online: 22 June 2020

Cite this chapter

- Melisa Stevanovic 6 ,

- Taina Valkeapää 6 ,

- Elina Weiste 7 &

- Camilla Lindholm 8

Part of the book series: The Language of Mental Health ((TLMH))

556 Accesses

2 Citations

The chapter analyzes practices by which support workers promote client participation in mental health rehabilitation meetings at the Clubhouse. While promoting client participation, the support workers also need to ascertain that at least some decisions get constructed during the meetings. This combination of goals—promoting participation and constructing decisions—leads to a series of dilemmatic practices, the dynamics of which the chapter focuses on analyzing. The support workers may treat clients’ turns retrospectively as proposals, even if the status of these turns as such is ambiguous. In the face of a lack of recipient uptake, the support workers may remind the clients about their epistemic access to the content of the proposal or pursue their agreement or commitment to the idea. These practices involve the support workers carrying primary responsibility over the unfolding of interaction, which is argued to compromise the jointness of the decision-making outcome.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Barry, M. J., & Edgman-Levitan, S. (2012). Shared decision making: The pinnacle of patient-centered care. New England Journal of Medicine, 366 (9), 780–781.

Article Google Scholar

Beitinger, R., Kissling, W., & Hamann, J. (2014). Trends and perspectives of shared decision-making in schizophrenia and related disorders. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 27 (3), 222–229.

Chamberlin, J. (1990). The ex-patients’ movement: Where we’ve been and where we’re going. Journal of Mind and Behavior, 11 (3&4), 323–336.

Google Scholar

Charles, C., Gafni, A., & Whelan, T. (1999). Decision-making in the physician-patient encounter: Revisiting the shared treatment decision-making model. Social Science and Medicine, 49 (5), 651–692.

Davidson, L., O’Connell, M. J., Tondora, J., Lawless, M., & Evans, A. C. (2005). Recovery in serious mental illness: A new wine or just a new bottle? Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 36 (5), 480–487.

Drake, R. E., Deegan, P. E., & Rapp, C. (2010). The promise of shared decision making in mental health. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 34 (1), 7–13.

Elstad, T. A., & Eide, A. H. (2009). User participation in community mental health services: Exploring the experiences of users and professionals. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Science, 23 (4), 674–681.

Epstein, R. M., Franks, P., Fiscella, K., Cleveland, G. S., Meldrum, S. C., Kravitz, R., & Duberstein, P. R. (2005). Measuring patient-centred communication in patient-physician consultations: Theoretical and practical issues. Social Science and Medicine, 61 (7), 1516–1528.

Ernst, M., & Paulus, M. P. (2005). Neurobiology of decision making: A selective review from a neurocognitive and clinical perspective. Biological Psychiatry, 58 (8), 597–604.

Goffman, E. (1955). On face work: An analysis of ritual elements in social interaction. Psychiatry: Journal for the Study of Interpersonal Processes, 18 (3), 213–231.

Goodwin, C. (1995). Co-constructing meaning in conversation with an aphasic man. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 28 (3), 233–260.

Hänninen, E. (2012). Choices for recovery: Community-based rehabilitation and the Clubhouse Model as means to mental health reforms . Helsinki: National Institute for Health and Welfare.

Hänninen, E. (Ed.) (2016). Mieleni minun tekevi: Mielenterveyskuntoutujien Klubitalot 20 vuotta Suomessa [I would like to: Clubhouses for mental health rehabilitation 20 years in Finland]. Helsinki: Lönnberg.

Hickey, G., & Kipping, C. (1998). Exploring the concept of user involvement in mental health through a participation continuum. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 7 (1), 83–88.

John-Steiner, V., & Mann, H. (1996). Sociocultural approaches to learning and development: A Vygotskian framework. Educational Psychologist, 31 (3–4), 191–206.

Kurhila, S. (2006). Second language interaction . Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Book Google Scholar

Laakso, M. (2012). Aphasia as an example of how a communication disorder affects interaction. In M. Egbert & A. Deppermann (Eds.), Hearing Aids Communication (pp. 138–145). Mannheim: Verlag für Gesprächsforschung.

Laakso, M. (2015). Collaborative participation in aphasic word searching: Comparison between significant others and speech and language therapists. Aphasiology, 29 (3), 269–290.

Larquet, M., Coricelli, G., Opolczynski, G., & Thibaut, F. (2010). Impaired decision making in schizophrenia and orbitofrontal cortex lesion patients. Schizophrenia Research, 116 (2), 266–273.

Niemi, J. (2010). Myönnyttelymuotti: Erimielisyyttä enteilevä samanmielisyyden konstruktio [Concession format: Construction of agreement anticipating disagreement]. Virittäjä, 114 (2), 196–222.

Sacks, H., & Schegloff, E. A. (1973). Opening up closings. Semiotica, 8 (4), 289–327.

Scarinci, N., Worrall, L., & Hickson, L. (2008). The effect of hearing impairment in older people on the spouse. International Journal of Audiology, 47 (3), 141–151.

Schegloff, E. A. (2007). Sequence organization in interaction: A primer in conversation analysis . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sidnell, J. (2013). Basic conversation analytic method. In J. Sidnell & T. Stivers (Eds.), The handbook of conversation analysis (pp. 77–99). Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Snow, C. E. (1977). The development of conversation between mothers and babies. Journal of Child Language, 4 (1), 1–22.

Stevanovic, M. (2012). Establishing joint decisions in a dyad. Discourse Studies, 14 (6), 779–803.

Stevanovic, M. (2015). Displays of uncertainty and proximal deontic claims: The case of proposal sequences. Journal of Pragmatics, 78, 84–97.

Stevanovic, M., & Peräkylä, A. (2012). Deontic authority in interaction: The right to announce, propose and decide. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 45 (3), 297–321.

Tomasello, M. (2009). Why we cooperate . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Treichler, E. B., & Spaulding, W. D. (2017). Beyond shared decision-making: Collaboration in the age of recovery from serious mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 87 (5), 567–574.

Valkeapää, T., Lindholm, C., Tanaka, K., Weiste, E., & Stevanovic, M. (2019). Interaction, ideology, and practice in mental health rehabilitation. Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Mental Health, 6 (1), 9–23.

Vehviläinen, S. (2014). Ohjaustyön opas: Yhteistyössä kohti toimijuutta [Guide for counselling work: In cooperation toward agency]. Helsinki: Gaudeamus.

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Thought and language . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Download references

Acknowledgements

This study (and the studies reported in Chapters 6 , 8 , 9 , and 12 ) was funded by the Academy of Finland (Grant No. 307630) and the University of Helsinki.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland

Melisa Stevanovic & Taina Valkeapää

Finnish Institute of Occupational Health, Helsinki, Finland

Elina Weiste

Tampere University, Tampere, Finland

Camilla Lindholm

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Melisa Stevanovic .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Faculty of Information Technology and Communication Sciences, Tampere University, Tampere, Finland

Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland

Melisa Stevanovic

The Finnish Institute of Occupational Health, Helsinki, Finland

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Stevanovic, M., Valkeapää, T., Weiste, E., Lindholm, C. (2020). Promoting Client Participation and Constructing Decisions in Mental Health Rehabilitation Meetings. In: Lindholm, C., Stevanovic, M., Weiste, E. (eds) Joint Decision Making in Mental Health. The Language of Mental Health. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-43531-8_2

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-43531-8_2

Published : 22 June 2020

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-43530-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-43531-8

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Close ×

- ASWB Exam Prep Overview

- LCSW Exam Prep (ASWB Clinical Exam)

- LMSW Exam Prep (ASWB Masters Exam)

- LSW Exam Prep (ASWB Bachelors Exam)

- California Law and Ethics Exam Practice

- Free Practice Test

- Get Started

- Free Study Guide

- Printed Exams

- Testimonials

The social worker's role in the problem-solving process

First, a question: what's that mean exactly?

The Problem-Solving Process

The problem-solving process is a systematic approach used to identify, analyze, and resolve issues or challenges. It typically involves several steps:

Identification of the Problem: The first step is to clearly define and identify the problem or issue that needs to be addressed. This involves understanding the symptoms and root causes of the problem, as well as its impact on individuals, groups, or the community.

Gathering Information: Once the problem is identified, relevant information and data are gathered to gain a deeper understanding of the issue. This may involve conducting research, collecting data, or consulting with stakeholders who are affected by or have expertise in the problem.

Analysis of the Problem: In this step, the information collected is analyzed to identify patterns, underlying causes, and contributing factors to the problem. This helps in developing a comprehensive understanding of the problem and determining possible solutions.

Generation of Solutions: Based on the analysis, a range of potential solutions or strategies is generated to address the problem. Brainstorming, creative thinking techniques, and consultation with others may be used to generate diverse options.

Evaluation of Solutions: Each potential solution is evaluated based on its feasibility, effectiveness, and potential impact. This involves considering factors such as available resources, potential risks, and alignment with goals and values.

Decision-Making: After evaluating the various solutions, a decision is made regarding which solution or combination of solutions to implement. This decision-making process may involve weighing the pros and cons of each option and considering input from stakeholders.

Implementation: Once a decision is made, the chosen solution is put into action. This may involve developing an action plan, allocating resources, and assigning responsibilities to ensure the effective implementation of the solution.

Monitoring and Evaluation: Throughout the implementation process, progress is monitored, and the effectiveness of the solution is evaluated. This allows for adjustments to be made as needed and ensures that the desired outcomes are being achieved.

Reflection and Learning: After the problem-solving process is complete, it's important to reflect on what was learned from the experience. This involves identifying strengths and weaknesses in the process, as well as any lessons learned that can be applied to future challenges.

The Social Worker's Role

Okay, so social worker's assist with all of that. The trickiest part (and the part most likely to show up on the ASWB exam) is decision making. Do social workers make decisions for clients, give advice, gently suggest...? The answer is no, sometimes, and sort-of. Client self-determination is a key component of social work ethics. Problem-solving and decision-making in social work are guided by these general principles:

Client-Centered Approach: Social workers prioritize the autonomy and self-determination of their clients. They empower clients to make informed decisions by providing them with information, options, and support rather than imposing their own opinions or solutions.

Collaborative Problem-Solving: Social workers engage in collaborative problem-solving with their clients. They work together to explore the client's concerns, goals, and available resources, and then develop strategies and plans of action that are mutually agreed upon.

Strengths-Based Perspective: Social workers focus on identifying and building upon the strengths and resources of their clients. They help clients recognize their own abilities and resilience, which can empower them to find solutions to their problems.

Non-Directive Approach: While social workers may offer suggestions or recommendations, they typically do so in a non-directive manner. They encourage clients to explore various options and consequences, and they respect the client's ultimate decisions.

Cultural Sensitivity: Social workers are sensitive to the cultural backgrounds, beliefs, and values of their clients. They recognize that advice-giving may need to be tailored to align with the cultural norms and preferences of the client.

Ethical Considerations: Social workers adhere to ethical principles, including the obligation to do no harm, maintain confidentiality, and respect the dignity and rights of their clients. They avoid giving advice that may potentially harm or exploit their clients.

Professional Boundaries: Social workers maintain professional boundaries when giving advice, ensuring that their recommendations are based on professional expertise and not influenced by personal biases or conflicts of interest.

On the Exam

ASWB exam questions on this material may look like this:

- During which step of the problem-solving process are potential solutions evaluated based on feasibility, effectiveness, and potential impact?

- In the problem-solving process, what is the purpose of gathering information?

- Which ethical principle guides social workers in giving advice during the problem-solving process?

Or may be a vignette in which client self-determination (eg re sleeping outside) is paramount.

Get ready for questions on this topic and many, many others with SWTP's full-length practice tests. Problem: need to prepare for the social work licensing exam. Solution: practice!

Get Started Now .

March 15, 2024.

Right now, get SWTP's online practice exams at a reduced price. Just $39 . Get additional savings when buying more than one exam at a time-- less than $30 per exam!

Keep going till you pass. Extensions are free.

To receive our free study guide and get started!

Using tools to enhance engagement in social services

Introduction.

Tools have the potential to transform how we work. Just like the DIY tools many of us keep in a cupboard at home, tools used in interactions between people have the power to save us time. They can also reduce effort, substantially increase the quality of our work, and aide and facilitate interactions and discussion between people. However, selecting the right tools and using them effectively is not easy; tools can end up sitting alongside creative engagement practice, rather than within it.

The use of tools in social service interactions can better support practitioners, reveal and reflect that which is unsaid, as well as the values, attitudes, constraints and assets practitioners bring to interactions Winter 2009

This Iriss On… is the result of collaboration between Iriss and the Leapfrog project (a research project lead by Lancaster University in partnership with the Glasgow School of Art). The work of both Iriss and Leapfrog has revealed first-hand how people work together differently when they have a tool that gives them permission to engage with others in a different way. We’ve also found that people’s trust and confidence in using tools can vary; we sometimes need to encourage practitioners to give tools a ‘go’, and to better understand the effectiveness of their use in practice. Here we draw on this experience to take a closer look at tools, their role in creative engagement and the challenges that accompany using them.

Tools can be used to re-design and create new organisations, services and systems Meroni & Sangiorgi, 2011

What do we mean by tools?

The term ‘tool’ is commonly used, interchangeably, with terms such as ‘resources’, ‘materials’ and ‘objects’. It is worth noting that ‘tools’ and ‘methods’ are also terms that are used interchangeably, however methods usually relate to a process in which a tool is used to assist people to reach a desired outcome.

Our Definition

Tools are objects which aim to support people to perform a function or achieve a desired outcome that otherwise would be more difficult or even impossible. For example, a stone can be used to knock in a nail, but a hammer makes it safer, more accurate and involves less effort. Similarly, tools that enhance engagement in the social services can enable richer, more productive interactions between social service practitioners and the people they work with. Yet we believe the skills and experience developed by practitioners working in social services can be your most useful tool. So you yourself could be thought of as your ‘primary tool of practice’ 3 .

Why tools can be useful

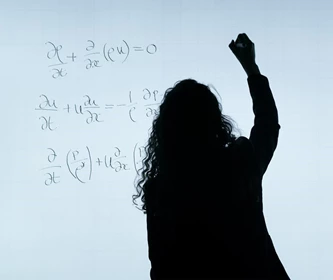

How people engage with one another is a very complex process. The process can be difficult to describe, relies upon people’s relationships with one another and how they communicate, and is influenced by aspects such as how they feel about one another, their roles and what they know and feel about the topic they are talking about.

However we’ll offer an interpretation to help get to grips with this process so we can highlight the contribution tools can make.

Interactions between practitioners and people who access services

There are, understandably, many approaches that social service practitioners may take when working with people. A core aspect of this role is using evidence from conversations and observations to make assessments about how they, in a professional capacity, can enable people. These judgements are made from several perspectives. They are influenced by organisational cultures and processes which invite and allow certain types of responses and not others, align with the profession’s code of ethics, and are influenced by the ability of the practitioner to relate to the person they are working with 4 .

These judgements, are therefore, not neutral, which can complicate how practitioners and people who access support work together. From the supported person’s perspective, this experience can be further complicated, particularly when they experience crisis, are stressed, fearful or feel under threat (due to this interaction or for other reasons). Therefore, interactions can be highly emotional and intimate encounters. They may also not engage with the practitioner, or find it difficult to communicate their views, feelings and needs 5 . Adding to this complexity are elements such as: the purpose of the interaction, what people’s needs are in any given situation, and how people prefer to communicate and learn.

In a health context, there is a broad framework which suggests the need for a ‘full range of activities’ that empower both the patient and the practitioner so that they have the knowledge they need to discuss particular topics 6,7 .

Suggested activities include the:

- recognition and clarification of a problem

- identification of potential solutions

- appraisal of potential solutions

- selection of a course of action

- implementation of the chosen course of action

- evaluation of the solution adopted

These activities can include the use of tools. It is also thought that tools can better support practitioners, reveal and reflect that which is unsaid, as well as the values, attitudes, constraints and assets they bring to interactions with people who access services 8 .

Designing services

Tools can also be an integral part of the re-design or innovation of organisational, service and system designs.

Meroni and Sangiorgi suggest that tools can be used to support people to analyse information, generate shared meaning, develop ideas and prototype new service ideas. When designing for services it is suggested that tools create a space in which people are given permission to engage with others in different ways, and encourage people to learn about one another, while acknowledging that neither person is an expert when it comes to the other’s knowledge and experience of the design of a service 9,10,11,12 . Practical ways tools can support the way people work together include offering a means of mediating conversations 13 , structuring the way people engage 14 , and aiding memory and thinking processe 15 . However, which tool, and when to use it, will depend on the needs of the people who are working together, the purpose and anticipated outcomes of any given situation.

Although not a comprehensive list of all the tools that can be used to design for service provision, Meroni and Sangiorgi 16 and Stickdorn and Schneider 17 present many service design tools and provide detailed explanations about their use in practice.

The right tool for the job

Navigating the myriad of tools available to social service practitioners is a daunting task for anyone. Our research reveals just how difficult it is to create a meaningful overview of tools because they are used in a extremely varied way in a great variety of contexts. Work within the Leapfrog project emphasises enabling adaptation of tools to fit with the needs and capabilities of specific individuals and groups.

In this section we present some of the tools that Iriss and Leapfrog have developed and describe how they can be adapted. We also signpost other tools that you may find helpful to enhance engagement.

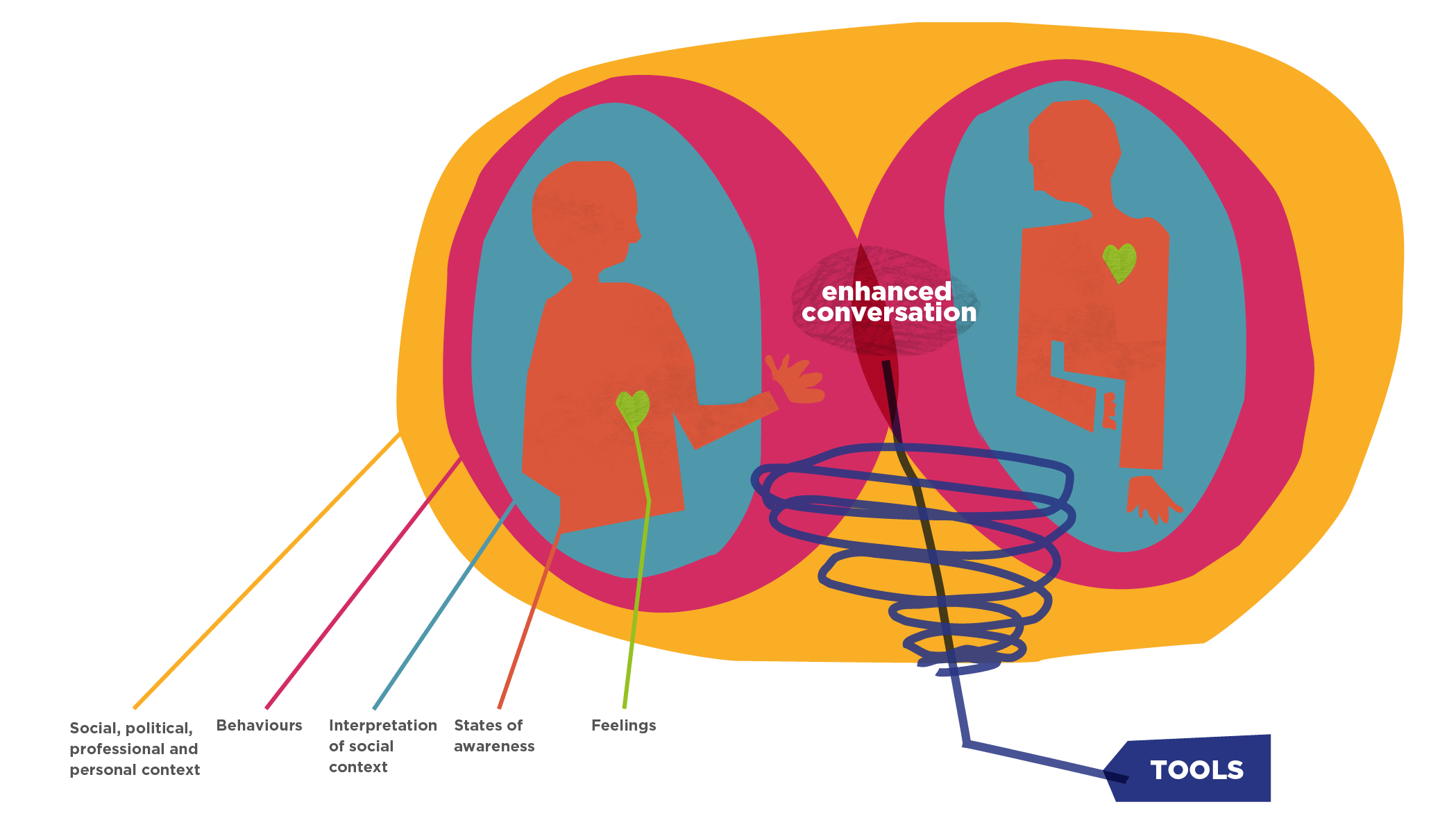

Tool name: What’s Important to You? (WITTY)

Type of activity: Engagement - reflection, personal assessment, planning

Intention and context: WITTY is an iPad app and paper-based tool which enables people to visually map positive assets and factors they have and can better engage with in day-to-day life. The intended outcome of using this tool is that people identify what it means for them to stay well, connected to these assets and happy.

This tool can be used to help people identify community and personal assets by creating a visual map of things a person has done in the past, things that exist in the present, or they would like to do in the future. This imagery enables people to see ‘the bigger picture’ of their life, and identify things they like and are able to do when they are not feeling well. It can be used individually, or to support conversations between practitioners and those who access support. If the tool is used with an asset-based approach it can also support conversations to move from a deficit-based model to an asset-based model when thinking about a person’s health.

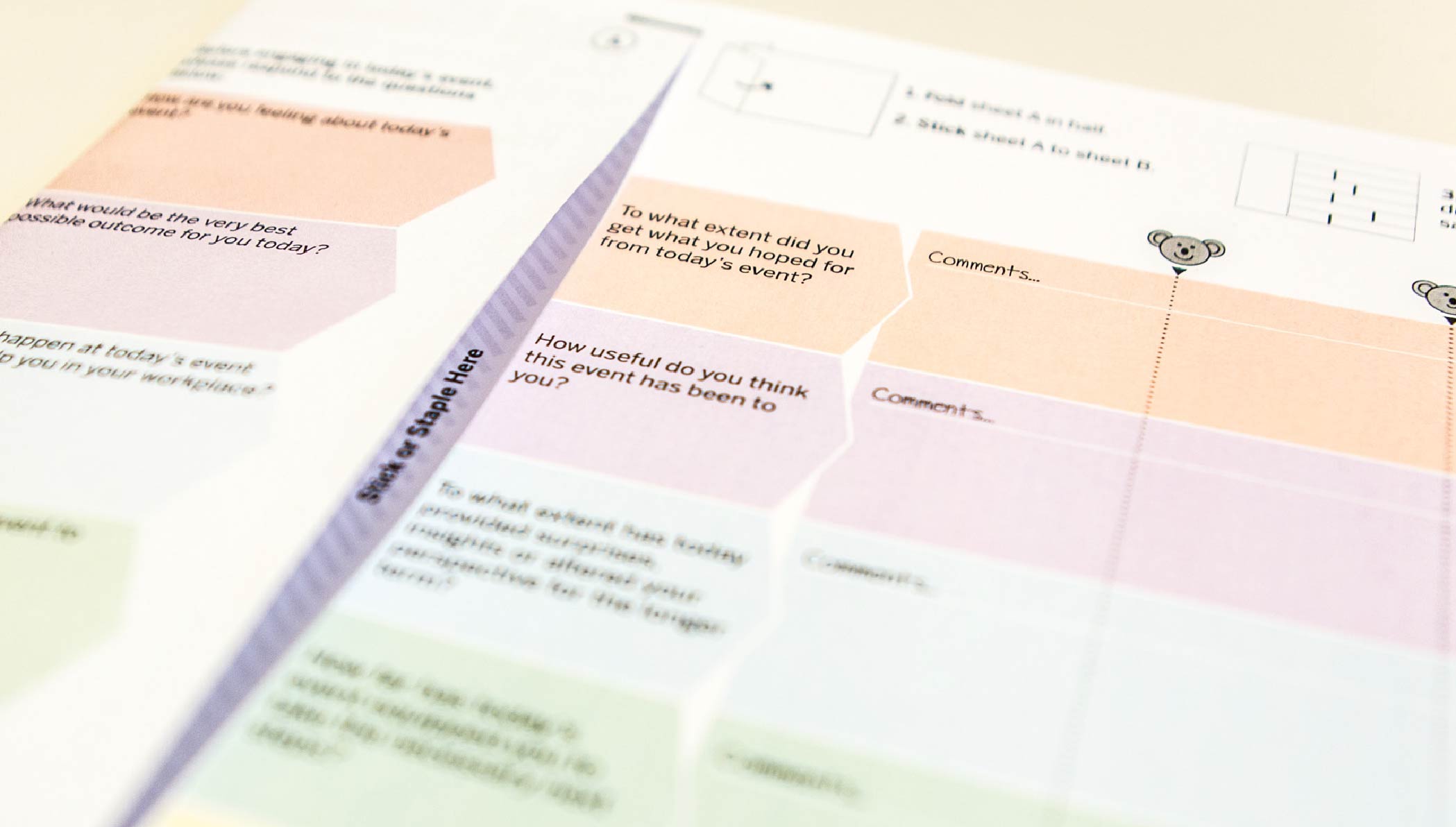

Tool name: Koala (KnOwledge And Learning evAluation)

Type of activity: Engagement evaluation

Intention and context: Koala seeks to improve end of a group work session evaluation by taking a different approach based on three principles.

- It captures expectations before an event and invites participants to use these as a baseline for reflection on the workshop.

- It invites the facilitator to tailor questions within the evaluation to better fit the needs and the audience they will be working with, rather than using generic language

- There is a constructional element to the evaluation, helping participants to see the evaluation as part of the workshop, as well as making it fun rather than just form-filling.

On or before arrival participants are invited to respond to a series of questions on an A5 sized sheet of paper. Critically, these are put aside and not available for participants to look at or modify during the session. At the end this A5 sheet is folded and wraps around or grips (like a Koala) an evaluation sheet that has a space for confidential comments, but also uses the expectations and other responses from the beginning of the session as a prompt for the evaluation questions.

We find that we get a great deal more qualitative feedback using this method compared to conventional evaluation sheets. We are also better able to calibrate these comments as we can better understand the starting or baseline state of the participant.

You may want to use this when thinking about developing service provision, or consider how to adapt it to use on a one-to-one basis.

Other tools that may enhance your practice

Participative practices can be key when enabling and enhancing working practices. You may, therefore, find several websites useful, such as:

- The Scottish Health Council’s Participation toolkit

- The Routledge International Handbook of Participatory Design

- Helen Sanderson person centered practices

- The Inclusion Press person centered methods and tools

- In Control have a number of toolkits, presentations and templates to support inclusion

- Tools developed by Iriss to support people who access and provide services work together

- Leapfrog’s creative engagement consultation tools

There are lots of tools that people use to support the design of organisations and services. For example:

- Design methods for developing services

- IDEOs Human Centered Design and Prototyping Kit

- The Social Design Methods Menu

- Service Design Toolkits

- Innovation Tools

- Experience Based Design toolkits used to improve the NHS

- Other methods and tools to develop services

- A range of tools to support the design of services as highlighted by Meroni and Sangiorgi 16 and Stickdorn and Schneider 17 .

There are also many tools that have been created to enable conversations that some people find difficult. For example:

- Helping children and young people communicate confidently: Conversation cards , Tools for social workers , In my shoes

- Supporting those with communication difficulties

- When working with complex systems

If you are aware of tools that are not included on this list please share a link to them using the #toolsforSSpractice on Twitter and include the Iriss and Leapfrog handle @irissorg @leapfrogtools so we can collate them.

Tips for adapting tools

Most tools are ripe for adaptation. If you do adapt tools, key tips include thinking about:

- Current and aspired outcomes and experiences of the interaction 18 . Who should identify this?

- Capabilities of the people who will use the tool 19 . What support might be needed?

- Ability to capture a variety of perspectives in a way that is useful to those who are involved 20 . What methods can be used for this and how does this fit into existing processes?

- Impact of overarching cultural, social, political and relational conventions which can enable but also constrain interactions 21 . Are these being challenged or accepted? How are they reflected in the design of the tool?

- Flexibility 22,23 . How can the tool work with matters that may arise during conversations?

Of note, some creators of tools share them with the aim of contributing to a more equitable, accessible and innovative world. Free Creative Commons licensing is used to explicitly state under what circumstances tools can be used and adapted 24 . This is something to check out when adapting someone else’s work.

Some benefits of using tools

It is important to point out that tools do not offer, structure, aid, prompt, encourage, reveal or reflect anything unless the people who are using them take the time to reflect on what they and others are hearing, seeing and doing. Reflective practice in the moment and after the event is key to making sense of what is learned individually and together 25,26,27,28 . We would suggest that openly sharing what you are thinking, feeling and learning with others supports the engagement process.

If tools are fully integrated into practice then the outcomes of using them will be as unique as the contexts and situations they are applied in.

A tool may enhance or distract from your practice. It is hard to identify what makes a tool work well for everyone. Through the process of reflective practice you will be able to identify this for yourself. However, there is some emerging evidence that tools support:

Inclusivity

Fundamental to the use of creative approaches to engagement is the opportunity it affords to include all voices 29,30,31 . Research into the partnerships between the voluntary arts and community sector, public and social service providers in the UK, provides evidence as to the value of creative engagement between public bodies and citizens.

Balancing power

There is a strong value associated with the ability of creative engagement to bridge divides. Tools that enable participation can support people to work together to co-create new practices, with improved chances of long term success 32,33 .

Gauntlett 34 identifies that when some people use tools they feel that they have been given time to create a thoughtful response to questions.

A holistic perspective

Using tools and developing visual imagery can aid people to develop opinions or responses on issues for which they do not always have words. As pictures are created, people are better able to discuss things from a holistic perspective rather than in the linear sequence, which language can often force. For example metaphors can be used to express abstract thoughts and feelings in a concrete way 35 .

Interestingly, tools and visual methods of engagement are said to support people to ‘unlock’ different kinds of responses, as the creative problem solving task means the brain works in a different way than when having a conversation without the use of tools 36 .

Things to remember…

- Using tools reflectively with people can foster collaborative learning opportunities

- Taking time to acquaint yourself with the relative merits of different tools means that you will be ready to consider how you might adapt them to better serve you and others needs

- Some tools are easy to use when people are familiar with them, while other's require training

- Using tools can be an effective way to support people to engage with each other

- Good tools are not a substitute for good practice

- Iriss tools

- Leapfrog tools

- Ruch G, Turney D and Ward A (2010) Relationship-based social work, London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers

- Rice (2016) Developing an interdisciplinary approach to design for, and evidence, the outcomes of young people and leaving care workers’ experiences of conversations about leaving care

- Entwistle V and Watt I (2006) Patient involvement in treatment decision-making: The case for a broader conceptual framework, Patient education and counselling, 63, 263-273

- Winter K (2009) Relationships matter, Child and Family Social Work, 14, 450-460

- Bernstein B (1971) Class, codes, and control, Theoretical Studies Towards A Sociology of Language, London: Routledge

- Engeström Y, Engeström R and Kärkkäinen M (1995) Polycontextuality and boundary crossing in expert cognition: Learning and problem solving in complex work activities, Learning and Instruction, 5 (4), 319–336

- Star SL (1989) The structure of ill-structured solutions: Boundary objects and heterogenous distributed problem solving, In L Gasser and M Huhns eds. Distributed Arti cial Intelligence, 2, 37–54. London: Pitman

- Suchman L (1994) Working relations of technology production and use, Computer Supported Cooperative Work, 2 (1-2), 21–39

- Conole G (2008) The role of mediating artefacts in learning design, Handbook of Research on Learning Design and Learning Objects: Issues, Applications, and Technologies, 0, 188–208

- Conole G and Fill K (2005) A learning design toolkit to create pedagogically effective learning activities

- Norman, D. A. (1991). Cognitive artifacts, pp17-38, in J Carroll (ed), Designing interaction: Psychology at the human-computer interface, New York: Cambridge University Press

- Meroni A and Sangiorgi D (2011) Design for services, London: Gower Publishing

- Stickdorn M and Schneider J (2010) This is service design thinking, The Netherlands: BIS Publishers

- Jewett T and Kling R (1991) The dynamics of computerization in a social science research team: A case study of infrastructure, strategies, and skills, Social Science Computer Review, 9(2), 246– 275

- Bowker G and Star S(2005)How to infrastructure,pp230- 244, in L Lievrouw and S Livingstone (eds) Handbook of new media : social shaping and social consequences of ICTs, SAGE Publications Ltd: London

- Hasu M and Engeström Y (2000) Measurement in action: an activity- theoretical perspective on producer–user interaction, International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 53(1), 61–89

- Creative Commons

- Dewey J (1916) Democracy and education, Philosophical Review, 735

- Freire P (2006) Pedagogy of the oppressed, New York: Continuum

- Forester J (1982) Planning in the face of power, Journal of the American Planning Association, 48(1), 67-80

- Sarkissian W, Hurford D and Wenman C (2010) Creative community planning, London: Routledge

- Kagan C and Duggan K (2011) Creating community cohesion, Social Policy and Society, 10 (03), 393-404

- Clennon O, Kagan C, Lawthom R and Swindells R (2015) Participation in community arts: Lessons from the inner-city

- GauntlettD(2008)Creative and refective production activities as a tool for social research, in J Prossor (ed.) ESRC research development initiative, building capacity in visual methods, Introduction to visual methods workshop [proceedings]. Unpublished

If you use tools as part of your practice share the tools you use with us by tweeting #toolsforSSpractice on Twitter and include the Iriss and Leapfrog handle @irissorg @leapfrogtools and tell us about your experiences.

To keep up-to-date with the work at Iriss please follow @irissorg on Twitter and sign up to the Iriss mailing list

To follow the work of the Leapfrog project, please follow @leapfrogtools on Twitter or visit the project website

- Written by: Gayle Rice, Leon Cruickshank, Roger Whitham and Hayley Alter. Thanks also extend to Lisa Pattoni and Rossendy Galabo for their contributions.

- Creative direction: Gayle Rice

- Illustration and Design: Josie Vallely

- Reviewed by: Debbie Lucas, Lead Officer, Child’s Plan, East Renfrewshire Council; Judith Midgley, Pilotlight Self Directed Support Associate, Iriss; Kathleen Quinn (MRes), Residential Foster Care Worker, Kibble.

The Leapfrog programme of work, undertaken by Imagination Lancaster and The Institute of Design Innovation at the Glasgow School of Art, is funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council. We would like to thank them for their contribution to the print costs of this publication.

Related resources

Room 130, Spaces 1 West Regent Street Glasgow G2 1RW

- Hannah Martin

- Ian Phillip

- Jeanette Sutton

- Jon Dimmick

- Kerry Musselbrook

- Louise Bowen

- Stuart Muirhead

- Our governance

- Be an associate

- Job vacancies

- Our priority areas

- Our innovation model

- Partner with us

- Current work

- Iriss podcast

- Case studies

- Learning materials

- Student research

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Moreover, social workers valued client participation significantly more than they used it. The implications for researchers and professionals in social services are discussed. Proper training could increase social workers' awareness of client participation and provide tools for implementation. Policy makers should set standards for its use and ...

paper is that client participation makes for a better social work interven tion, and thus the higher the degree of client participation the more effective the intervention will be (Kurzman and Solomon, 1970; Freed berg, 1989; York, 1989). In Bernstein's words: we find that imposing, telling or giving orders do not work well. Only as the

Client participation is both a value and a strategy in social work, involving clients in decisions influencing their lives. Nevertheless, the factors encouraging its use by social workers in social services have received little research attention. This article reports on a study drawing on Goal Commitment Theory to examine, for the first time, four categories of variables that might predict ...

This approach has important implications for moving the profession toward greater accountability in the practice of social work. Unless educators can motivate practitioners to change the way in which they ask questions and make predictions, it is unlikely that practitioners will use scientific information in their problem-solving processes.

Client participation is a central value of social work, and it is generally assumed that inter vention involving clients will be more effective than that in which they are not involved. ... was tested empirically by questioning 200 senior workers in Israeli community centers as to the techniques of client participation they used in their work ...

1. Client participation. In the context of social and health care, the idea of client participation has recently undergone a significant change. This holds particularly true for the means of decision-making (for overviews, see Weiste, Stevanovic, & Lindholm, 2020).In these contexts, the authority to make decisions has earlier belonged to professionals, who have relied on their professional ...

The sample included 264 participants, 132 social workers employed by social service departments in a wide range of positions and one client of each of the professionals (132 clients) participated ...

Terry T. F. Leung. "Client participation" is a popular ideal and object of rhetorical commitment in social work. service. But the much-touted potential of this concept requires careful and critical scrutiny. This article reports on a study of client-participation initiatives in the Hong Kong welfare sector.

Broadening participation in community problem solving: A multidisciplinary model to support collaborative practice and research. ... and few of them have integrated their work with experiences or literatures beyond their own domain. In this article, we seek to overcome some of this fragmentation of effort by presenting a multidisciplinary model ...

The level of client participation can range from very low (e.g., informing clients of decisions made by the social worker) to very high (e.g., the client alone makes all the relevant decisions ...

One key form of participation is the right to make joint decisions. In recent decades, the importance of joint decision-making has been highlighted in the field of social and health care, where the client's right to self-determination and empowerment have been emphasized (Epstein et al., 2005).In mental health care, particularly in the United States since the 1970s, this development has been ...

Social Construction of Client Participation 37 Definitions There are differences in terminology for defining the topic here. Social workers have generally used the term client, al-though those who work in medical and psychiatric systems typically use patient. During the 1960s, the words patient and

Problem Solving in Social Work Practice: Implications for Knowledge Utilization. July 1991. Research on Social Work Practice 1 (3):306-318. DOI: 10.1177/104973159100100306. Authors: José Ashford ...

Social Worker's Role in the Problem-Solving Process. During treatment, a social worker takes on the role of a mentor. They manage the diagnosis and assessment of the client. They are also ...

Involving Clients in Identifying their Problems. At times, social workers need to help their clients come to the realization that they have a problem. In other situations, clients may realize that ...

ABSTRACT Client participation is both a value and a strategy in social work, involving clients in decisions influencing their lives. Nevertheless, the factors encouraging its use by social workers in social services have received little research attention. This article reports on a study drawing on Goal Commitment Theory to examine, for the first time, four categories of variables that might ...

problem-solving or processing client issues. This paper is focusing on the assessment component. Social workers are aware that micro, mezzo and macro levels impact client systems. In fact one definition of Social Systems Theory is the interconnectedness of the person and environment on the micro, mezzo and macro levels.

The answer is no, sometimes, and sort-of. Client self-determination is a key component of social work ethics. Problem-solving and decision-making in social work are guided by these general principles: Client-Centered Approach: Social workers prioritize the autonomy and self-determination of their clients. They empower clients to make informed ...

Suggests that professional workers should consider a more realistic model, based on self-help, mutual aid, and group services, rather than the traditional medical model. Advantages of a problem-solving model include (a) reliance on processes related to the problem rather than the service setting; (b) involvement of services at levels in addition to the pragmatic or cognitive; and (c) providing ...

For example, a stone can be used to knock in a nail, but a hammer makes it safer, more accurate and involves less effort. Similarly, tools that enhance engagement in the social services can enable richer, more productive interactions between social service practitioners and the people they work with. Yet we believe the skills and experience ...

cess and goal of social treatment. This SOCIAL PROBLEM SOLVING. dents' ability to solve interpersonal to the ability to resolve personal and problems is related to their ability to interpersonal problems through a con- carry out the steps of a problem-solving scious decision-making process. treatment approach.

The profession of social work emphasizes problem solving and positive change from a strength-based perspective. Social workers serve as change agents in society and in the lives of the individuals ...

CLIENT PARTICIPATION - refers to the client part and active involvement in the entire problem solving process o Clients are asked to provide pertinent facts and to define the nature of the problem and is also involved in prioritizing these problems o Social workers builds upon and utilizes the clients strengths and should be able to make the ...