What Is Loving-Kindness Meditation? (Incl. 4 Metta Scripts)

… would you believe me?

Probably not.

Yet it is all possible if you practice loving-kindness meditation. And science backs up my claim.

Loving-kindness meditation (LKM) is an ancient Buddhist practice that cultivates goodwill and universal friendliness toward oneself and others.

In this article, I’ll explain more about what it is, how it works, and the benefits of the practice according to research. I’ll also provide useful resources and scripts to help you try LKM, deepen your existing practice, and introduce it to your clients.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Mindfulness Exercises for free . These science-based, comprehensive exercises will help you cultivate a sense of inner peace throughout your daily life, and will also give you the tools to enhance the mindfulness of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

What is loving-kindness meditation, benefits of loving-kindness meditation, 2 metta meditation scripts, 2 short loving-kindness meditation scripts, guided audio meditations, 3 recommended youtube videos (incl. metta meditation), 3 meditation books, a take-home message.

Loving-kindness meditation is the English translation of “metta bhavana,” the first of the Four Brahma Vihara meditation practices taught by the Buddha to cultivate positive emotions (Feldman, 2017).

Loving-kindness meditation (LKM) focuses on generating loving-kindness toward oneself and others in a graded way to include all living beings eventually, both seen and unseen, across the cosmos. Importantly, metta is sometimes translated as “universal friendliness” to emphasize the impersonal nature of the affection generated, free from any desire or expectation of return (Griffin, 2022).

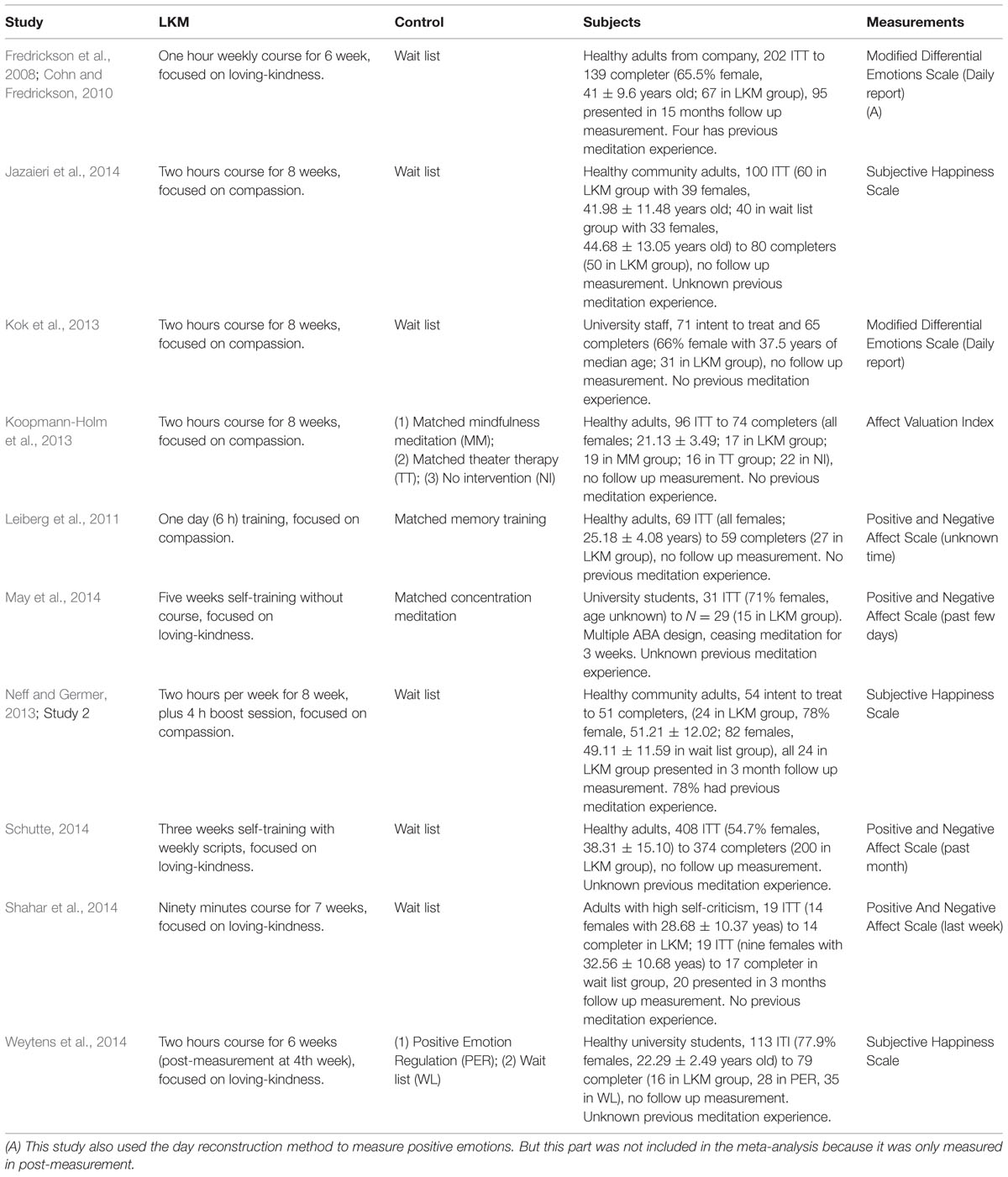

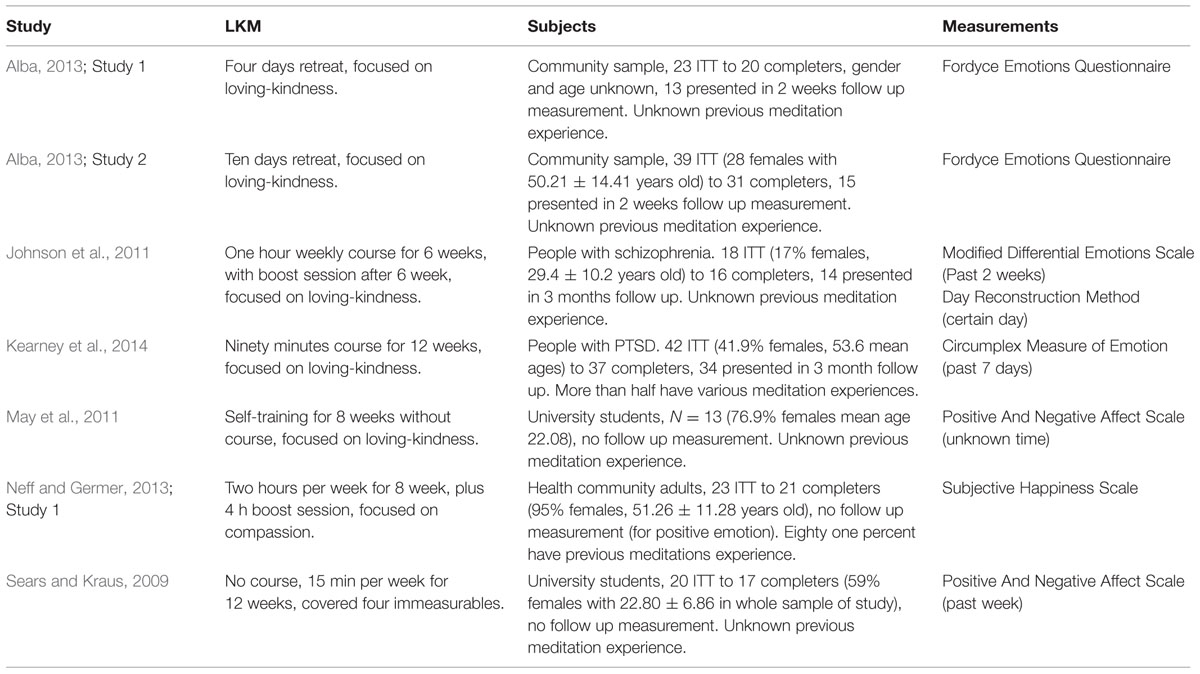

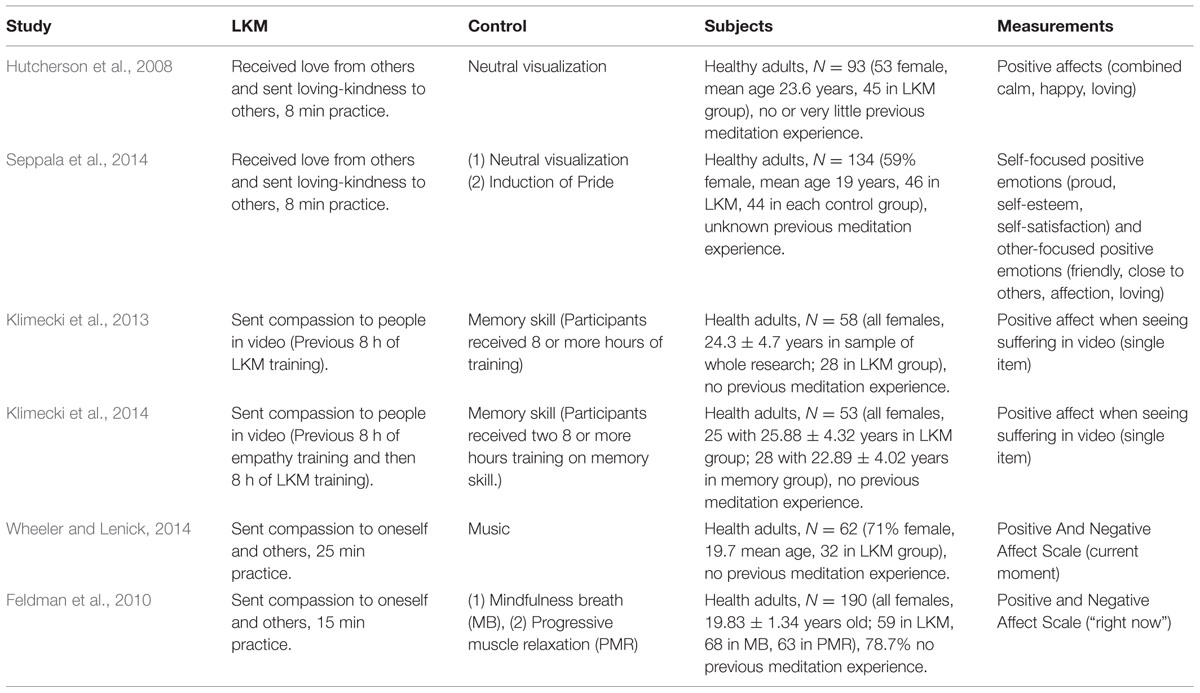

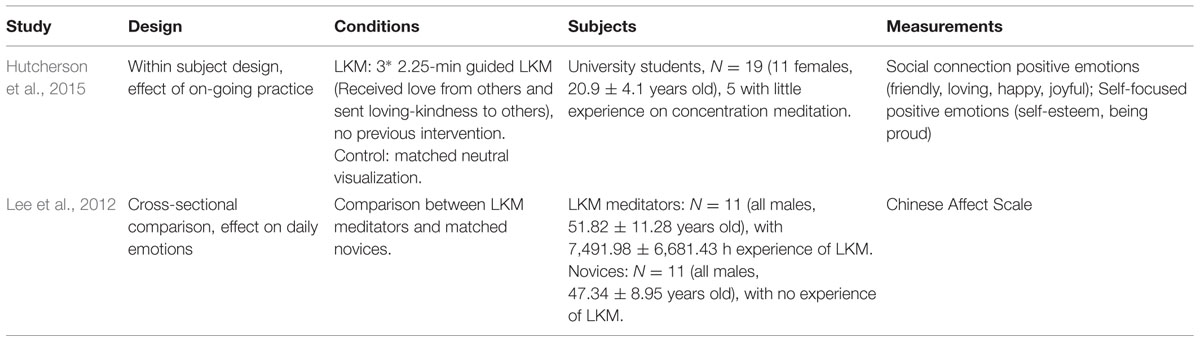

Recent scientific research has shown that LKM enhances mental wellbeing in many ways that support the claims of Buddha’s original teaching. The benefits of the practice are discussed in more detail below.

4 Brahma Viharas

LKM is the foundational practice of a quartet of Buddhist meditation practices called the Four Brahma Viharas (also called the four divine abodes or the four immeasurables). These are a set of complementary meditation practices that focus on cultivating positive emotions (Feldman, 2017):

- Metta (loving-kindness)

- Karuna (compassion)

- Mudita (appreciative joy)

- Uppekha (equanimity)

Each of these positive meditation practices provides the foundation for the next. For example, we need to generate loving-kindness to cultivate compassion, and we need both loving-kindness and compassion practices to cultivate the appreciative joy that celebrates others’ talents and success (Nhat Hanh, 2006).

The Buddha prescribed these three practices as a method for transforming their opposing emotional states as follows:

- Loving-kindness overcomes hatred.

- Compassion overcomes cruelty.

- Appreciative joy overcomes envy.

When these three practices are combined, a state of serenity is eventually attained called equanimity. This is the emotional foundation of freedom from suffering (Nhat Hanh, 2006).

What loving-kindness is and isn’t – Sharon Salzberg

In the video below, meditation teacher and international bestselling author Sharon Salzberg (2002) explains in more detail what loving-kindness is and isn’t. This is important given that in Western, competitive cultures, the idea of practicing loving-kindness toward all life-forms may evoke fears of weakness and gullibility.

However, nothing could be further from the truth. Far from putting practitioners at risk of being manipulated or abused, the fruits of LKM practice are an open and fearless heart with an enhanced ability to manage conflict by taking things much less personally.

In the section below, I discuss the benefits of the practice, but overall, research shows that a regular LKM practice improves resilience and should be considered a source of strength (Kabat-Zinn, 2023).

Salzberg explains how loving-kindness practice challenges conventional notions of love as personal, conditional, and transactional. Take a look at her entertaining and surprising talk in this video .

Taking a more secular perspective, you could say that the Buddha taught metta to the monks to help them overcome their fear while meditating alone in the forest at the mercy of many dangers. The rationale for the practice is that generating goodwill toward all living beings banishes fear because loving-kindness and fear cannot coexist. Metta is protective, both physically and mentally (Ñanamoli Thera, 1994).

For example, most of us will be familiar with how feeling afraid and anxious can make you more vulnerable to harm when traveling alone far from home. Those with criminal intentions look for signals of vulnerability when targeting a victim.

A similar logic applies here. The Buddha taught his monks metta because love and fear cannot coexist. A lack of fear made the monks less vulnerable, calmed them down, and they created less disturbance in the forest. The story is that once the monks began to practice metta meditation, the tree and earth spirits were pacified and even protected them during their practice (Buddharakkhita, 2013).

According to the Buddha

The Buddha gave a talk on the 11 benefits of loving-kindness meditation (AN 11.16), some of which are now supported by science.

- You sleep well.

- You awaken refreshed.

- You don’t have bad dreams.

- Other people regard you with affection.

- Animals and pets regard you with affection.

- Celestial beings protect you.

- You will be free from injury from fire, weapons, and poison.

- You can concentrate quickly.

- You have a bright complexion.

- You will die peacefully, free of fear and agitation.

- If you fail to attain enlightenment, you will have a pleasant rebirth.

According to science

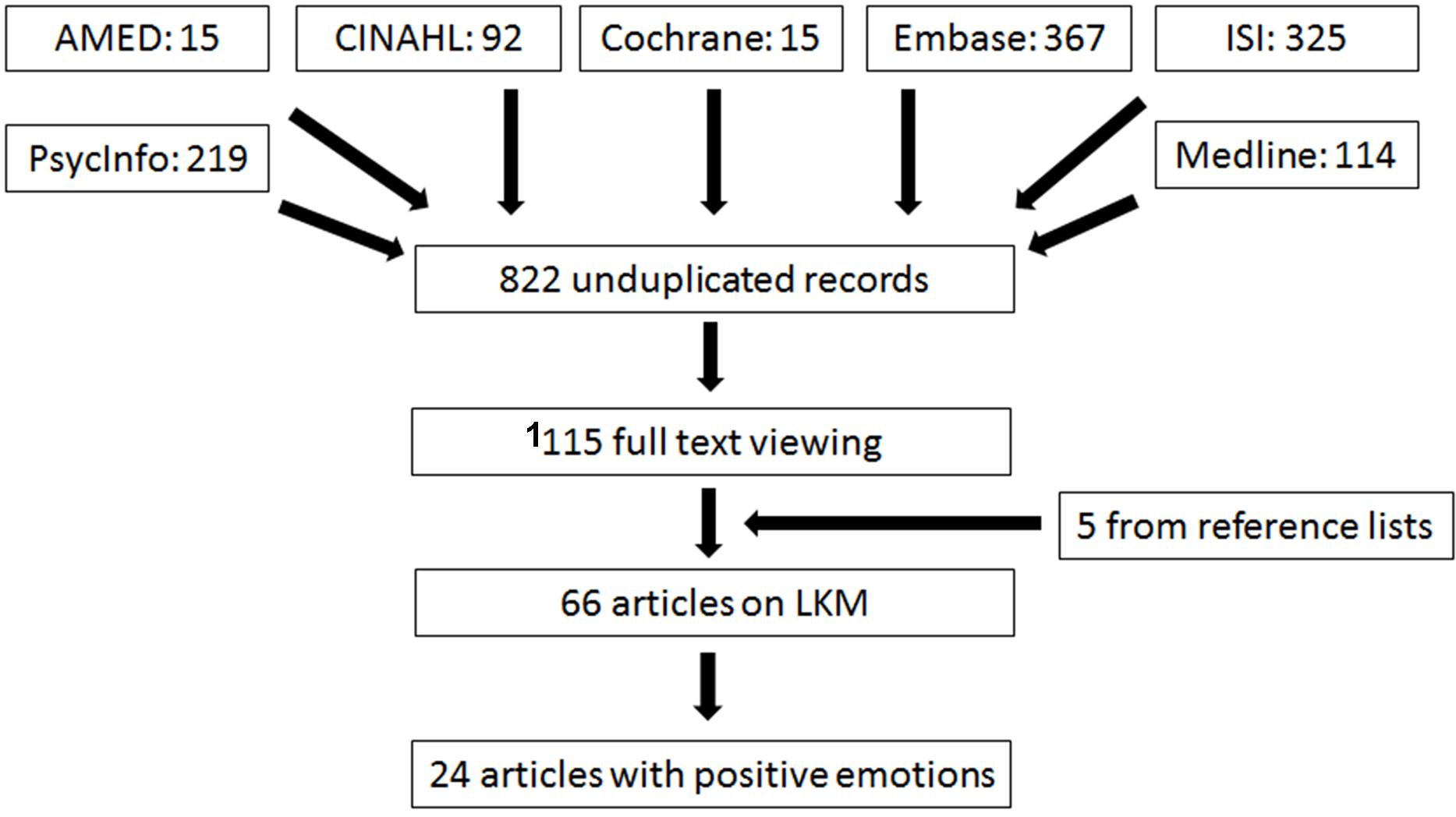

Below is a snapshot of the benefits of LKM according to the latest scientific research.

1. Reduced self-criticism

Loving-kindness meditation reduces self-criticism, quietens our inner critic, and makes us more self-accepting (Shahar et al., 2015).

Also, seven weeks of LKM resulted in a marked reduction in self-harming impulses in individuals with suicidal tendencies and borderline personality traits (Fredrickson et al., 2008).

2. Enhanced wellbeing

Studies have shown that regular LKM practice increases vagal tone, a physiological marker of subjective wellbeing that improves the quality of life and life satisfaction (Kok et al., 2013).

3. Reduced cellular aging

A 12-week randomized control trial comparing the effects of mindfulness meditation and LKM on telomere length in beginner practitioners found that LKM buffered the telomere shortening associated with cellular aging (Le Nguyen et al., 2019).

4. Reduced pain

Pilot studies on patients with chronic back pain (Carson et al., 2005) and migraine (Tonelli & Wachholtz, 2014) showed that when they practiced loving-kindness meditation for brief periods, participants experienced a reduction in pain symptoms and accomplished their daily tasks with more ease and comfort.

5. Greater resilience

A study of patients with long-term post-traumatic stress disorder showed that engaging in compassion and self-love meditations reduced trauma symptoms and flashbacks (Kearney et al., 2013).

Control studies showed that groups that received loving-kindness meditation scripts during their sessions could resume work sooner than participants who received other instruction.

Also, LKM improves resilience and helps prevent burnout in healthcare providers (Seppala et al., 2014).

6. Improved relationships

Loving-kindness meditation results in greater empathy for strangers and better social connections at work (Hutcherson et al., 2008), as well as greater stability in social relationships in general (Don et al., 2022).

7. Improved mental health

The research into the impact of LKM on major mental health disorders is still in its infancy, but preliminary findings have reported a reduction in rumination and negative affect in patients diagnosed with depression (Hofmann et al., 2015) and a reduction in hallucinations and delusions in patients diagnosed with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (Johnson et al., 2011).

Given the benefits, here’s some guidance on how to practice LKM.

Download 3 Free Mindfulness Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients enjoy the benefits of mindfulness and create positive shifts in their mental, physical, and emotional health.

Download 3 Free Mindfulness Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

Posture is all important when learning how to meditate. The most important thing is to be comfortable. Sitting with a straight back in a chair or on the floor is usually advised. However, you could try lying on a yoga mat flat on your back with a pillow under your head and another under your knees if sitting is uncomfortable.

When you’ve decided on your posture, do a quick scan of your body to detect areas of tension, such as tight shoulders. Take a few deep breaths and relax. Scan your body again to ensure you’re relaxed but alert.

The following script is taken from my article on guided meditation , which uses the power of imagery and visualization .

Loving-kindness meditation 1

“Imagine a dearly loved person sitting opposite you and that a white light connects you heart to heart. Connect with the feelings of affection and warmth you have for them.

Enjoy the feelings as they fill your body.

Next, slowly focus on the phrase, ‘May I be well, happy, and peaceful,’ feeling the warmth of loving-kindness filling your body.

And send these feelings to your friend. ‘May you be well, happy, and peaceful.’

Breathing naturally… As the light connects you, heart to heart.

‘May I be well, happy, and peaceful.’

‘May you be well, happy, and peaceful.’

Feel yourselves bathed in the warmth and light of loving-kindness while repeating these phrases, silently (mentally recite for two minutes).

Remember to breathe naturally, as the white light connects you both, heart to heart, and continue. ‘May I be well, happy, and peaceful. May you be well, happy, and peaceful.’

Next, remembering to breathe naturally, imagine the white light between you becoming a circle of light around you both.

The light is bathing you in the warmth and peace of loving-kindness that you radiate out to your surroundings.

Including all beings, from the smallest insect to the largest animal … and out into the universe.

See yourself and your friend radiating the light of loving-kindness out into infinity. ‘May we be well, happy, and peaceful. May all beings be well, happy, and peaceful.’

Breathing naturally, repeat these phrases, silently. ‘May we be well, happy, and peaceful. May all beings be well, happy, and peaceful’ (mentally recite this for two minutes).

Now, enjoy the feelings of warmth and expansion in your body. Recognize the feelings that flow from your heart out into the universe … and the universal friendliness reflected in your own heart.

‘May we be well, happy, and peaceful. May all beings be well, happy, and peaceful’ (mentally recite this for one minute).

As you continue to bathe in the warmth of loving-kindness, turn your attention to your body and notice your feelings and sensations. Notice ‘what’ is observing your body and recognize that awareness … a peaceful, still part of you, that witnesses everything, without judgment.

Breathe naturally.

And slowly open your eyes.”

Loving-kindness meditation 2

You can also download another free Loving-Kindness Meditation worksheet that has been adapted from Fredrickson et al. (2008) and Hutcherson et al. (2008).

1. LKM bitesize

This short script can be adapted using a variety of phrases that specifically apply to your own or your client’s situation. Suggested phrases include:

May I/you be healthy, well, at ease, light, happy, peaceful, strong, safe.

With eyes closed and back straight, focus your attention on the heart. You can also place a hand there if it helps.

First, send yourself loving-kindness by repeating your chosen phrases three times. For example:

“May I be healthy, safe, and strong.”

Next, think of someone you care for deeply (not a romantic partner or spouse), a neutral person you see around regularly, and somebody you’re having difficulties with at the moment. Imagine the four of you sitting in a circle.

Keeping all of them in mind, repeat your chosen phrases to your circle three times.

“May you be healthy, safe, and strong.”

Next, imagine the loving-kindness spreading out from your small circle to the neighborhood, country, continent, and across the world to all life-forms. Repeat the following phrase three times:

“May all beings on planet earth be healthy, safe, and strong.”

Next, imagine loving-kindness radiating from the earth into space and to all life-forms in the cosmos repeating the phrase:

“May all beings throughout all time and space be healthy, safe, and strong.”

Slowly bring your awareness back to your breath and your surroundings, and then gradually open your eyes.

2. UCLA LKM Script

You can also download this free 10-minute LKM transcript courtesy of UCLA’s Semel Institute.

Guided audio meditations are especially useful when practicing at home or during a commute or long journey. You can download or stream these and listen to them at your leisure.

Guided loving-kindness practice by Emma Seppala

Dr. Emma Seppala is the science director of Stanford University’s Center for Compassion and Altruism Research and Education and author of The Happiness Track .

This short 15-minute audio meditation is ideal for beginners. You can listen and follow the audio script on SoundCloud .

Guided metta meditation by Gil Fronsdal

Gil Fronsdal is a veteran meditation teacher who has been active in this field since 1990. Here is a 30-minute guided metta meditation that is ideal for beginners and experienced meditators.

Guided meditation by Tara Brach

Tara Brach, PhD, is a meditation teacher, psychologist, and author of several bestselling books. She founded the Insight Meditation Community in Washington DC, one of the liveliest meditation centers in the United States.

The video guides you through her brand of loving-kindness meditation, which is accessible to beginners and great for those needing a refresher.

Street loving-kindness by Sharon Salzberg

You don’t have to confine your loving-kindness practice to meditation. You can use loving-kindness to establish a fearless open heart that connects you to the best in yourself and others in any situation.

For this purpose, veteran LKM teacher Sharon Salzberg developed her street loving-kindness practices to help practitioners stabilize the fruits of LKM in everyday life.

Visit her free online resources here .

Top 17 Exercises for Mindfulness & Meditation

Use these 17 Mindfulness & Meditation Exercises [PDF] to help others build life-changing habits and enhance their wellbeing with the physical and psychological benefits of mindfulness.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

The following YouTube videos have supported me in my LKM practice, as well as my coaching clients and students.

1. Karaniya Metta Sutta chanting by Bhante Indrathana

If you can’t find time to sit but need a short boost of positive energy or a brief self-compassion or self-soothing practice, try listening to Bhante Indrathana chanting the Karaniya Metta Sutta (SN 1.8), an original discourse of the Buddha.

People in Buddhist countries often play this in the morning to invite positive energy to the house and for the day ahead.

2. 10-Minute LKM with Sharon Salzberg

If you have spare 10 minutes when you can take a breather, try this short LKM with Sharon Salzberg.

3. Guided metta meditation from Mahamevnawa Bodhignana Monastery, Sri Lanka

You can practice this metta meditation open eyed if you like. The video depicts a Buddhist monk meditating in the forest as they still do to this day in Sri Lanka, Thailand, and other Buddhist cultures.

Meanwhile, the monk’s voice guides you through an ancient metta practice.

These books are widely regarded as LKM classics.

1. Lovingkindness : The Revolutionary Art of Happiness – Sharon Salzberg

In this book, Sharon Salzberg describes the sense of liberation that follows from daily LKM practice.

Seen as a must-read for LKM practitioners, Salzberg introduces evidence-based approaches that apply LKM to modern life.

Throughout, she draws on Buddhist teachings and guided meditation exercises to teach us how to love ourselves and others by uncovering the well of natural goodness dwelling in our own heart.

Find the book on Amazon .

2. Loving-Kindness in Plain English: The Practice of Metta – Bhante Henepola Gunaratana

Buddhist monk Bhante Gunaratana introduces a step-by-step LKM practice and shares many stories about the results of LKM in everyday life.

In the book, Bhante shares personal anecdotes, step-by-step meditations, and the Buddha’s words in the suttas to teach us how to cultivate peace within ourselves and in all our relationships.

You can listen to one of these stories in this reading from the book courtesy of AudioBuddha.

3. True Love: A Practice for Awakening the Heart – Thich Nhat Hanh

True Love is a book in which Zen Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh explores loving-kindness, compassion, joy, and freedom with his characteristic simplicity, warmth, and directness.

He emphasizes that to love in a real way, we must first learn how to be fully present and authentic with ourselves and others .

If you want to learn how to care for yourself and others by applying LKM to self-care and relationships, this book is recommended.

Now that you have all the research, scripts, and information on loving-kindness meditation, it is time to try out the magic formula for yourself.

As I’ve mentioned, loving-kindness meditation has many proven benefits and is a wonderful self-care practice that can also improve our relationships with others. It helps us cultivate an abiding sense of goodwill toward all forms of life while improving our resilience to life’s difficulties.

Not only that, but the sense of connectedness that develops with regular LKM practice can also help overcome feelings of loneliness and grief (Nhat Hanh, 2006).

Given it is an active meditation that replaces our inner dialogue with more helpful self-talk, it can be an especially helpful practice for those who struggle with lethargy in other forms of meditation.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Mindfulness Exercises for free .

Ed: Updated March 2023

- Buddharakkhita, A. (2013). Metta: The philosophy and practice of universal love . Access to Insight. Retrieved March 11, 2023, from http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/buddharakkhita/wheel365.html.

- AN 11.16: Metta (Mettanisamsa) Sutta: Discourse on advantages of loving-kindness (Piyadassi Thera, Trans.). (2005). Access to Insight. Retrieved March 11, 2023, from http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/an/an11/an11.016.piya.html.

- Carson, J. W., Keefe, F. J., Lynch, T. R., Carson, K. M., Goli, V., Fras, A. M., & Thorp, S. R. (2005). Loving-kindness meditation for chronic low back pain: Results from a pilot trial. Journal of Holistic Nursing , 23 (3),287–304.

- Don, B. P., Van Cappellen, P., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2022). Training in mindfulness or loving-kindness meditation is associated with lower variability in social connectedness across time. Mindfulness , 13 , 1173–1184.

- Feldman, C. (2017). Boundless heart: The Buddha’s path of kindness, compassion, joy, and equanimity . Shambhala.

- Fredrickson, B. L., Cohn, M. A., Coffey, K. A., Pek, J., & Finkel, S. M. (2008). Open hearts build lives: Positive emotions, induced through loving-kindness meditation, build consequential personal resources. Journal of Personal and Social Psychology , 95 (5),1045–1062.

- Griffin, K. (2022, December 29). Practicing fearless metta . Tricycle. Retrieved March 11, 2023, from https://tricycle.org/article/practicing-fearless-metta/.

- Hofmann, S. G., Petrocchi, N., Steinberg, J., Lin, M., Arimitsu, K., Kind, S., Mendes, A., & Stangier, U. (2015). Loving-kindness meditation to target affect in mood disorders: A proof-of-concept study. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine , 2015 .

- Hutcherson, C. A., Seppala, E. M., & Gross, J. J. (2008). Loving-kindness meditation increases social connectedness. Emotion , 8 (5), 720–724.

- Johnson, D. P., Penn, D. L., Fredrickson, B. L., Kring, A. M., Meyer, P. S., Catalino, L. I., & Brantley, M. (2011). A pilot study of loving-kindness meditation for the negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research , 129 (2–3),137–40.

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (2023, February 10). This loving-kindness meditation is a radical act of love . Mindful. Retrieved March 11, 2023, from https://www.mindful.org/this-loving-kindness-meditation-is-a-radical-act-of-love/.

- Kearney, D. J., Malte, C. A., McManus, C., Martinez, M. E., Felleman, B., & Simpson, T. L. (2013). Loving-kindness meditation for posttraumatic stress disorder: A pilot study. Journal of Traumatic Stress , 26 (4), 426–434.

- Kok, B. E., Coffey, K. A., Cohn, M. A., Catalino, L. I., Vacharkulksemsuk, T., Algoe, S. B., Brantley, M., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2013). How positive emotions build physical health: Perceived positive social connections account for the upward spiral between positive emotions and vagal tone. Psychological Science , 24 (7), 1123–1132.

- Le Nguyen, K. D., Lin, J., Algoe, S. B., Brantley, M. M., Kim, S. L., Brantley, J., Salzberg, S., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2019). Loving-kindness meditation slows biological aging in novices: Evidence from a 12-week randomized controlled trial. Psychoneuroendocrinology , 108 , 20–27.

- Ñanamoli Thera. (1994). The practice of loving-kindness (metta): As taught by the Buddha in the Pali canon . Access to Insight. Retrieved March 11, 2023, from https://www.accesstoinsight.org/ati/lib/authors/nanamoli/wheel007.html.

- Nhat Hanh, T. (2006). True love: A practice for awakening the heart . Shambhala.

- Salzberg, S. (2002). Lovingkindness: The revolutionary art of happiness . Shambhala.

- Seppala, E. M., Hutcherson, C. A., Nguyen, D. T., Doty, J. R., & Gross, J. J. (2014). Loving-kindness meditation: A tool to improve healthcare provider compassion, resilience, and patient care. Journal of Compassionate Health Care , 1 .

- Shahar, B., Szsepsenwol, O., Zilcha-Mano, S., Haim, N., Zamir, O., Levi-Yeshuvi, S., & Levit-Binnun N. (2015). A wait-list randomized controlled trial of loving-kindness meditation program for self-criticism. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy , 22 (4), 346–356.

- SN 1.8: Karaniya Metta Sutta: The Buddha’s words on loving-kindness (Amaravati Sangha, Trans.). (2004). Access to Insight. Retrieved from http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/kn/snp/snp.1.08.amar.html.

- Tonelli, M. E., & Wachholtz, A. B. (2014). Meditation-based treatment yielding immediate relief for meditation-naïve migraineurs. Pain Management Nursing , 15 (1), 36–40.

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

Thank You for this incredible article on Love-Kindness Meditation. It is very helpful and I will apply it to my personal and professional life.

Thank you for such a comprehensive guide to loving-kindness practices. I am new to loving-kindness. This article gave me a lot to work with as I create and develop an approach that works for me. I look forward to applying these principles to my life.

Thank you for taking the time to write this comprehensive article on Loving Kindness Meditation. It was very helpful.

One of the most comprehensive and accessible reviews of different teachers’ approaches. Thank you

Thank you for this beautifully extensive article on the practice and research on loving kindness meditation. The world really needs this….

Thanks – a through study of meditation should include the 112 techniques listed in Paul Reps book, Zen Flesh, Zen Bones and explained by OSHO in The Book Of The Secrets. NOTE: Your buddha quote is listed online as a FAKE BUDDHA QUOTE. We really don’t know what THE BUDDHA said; the first Buddhist writings were hundreds of years after his death.

The Buddha’s teachings were collected 3 months after he passed away at the First Buddhist Council at Rajagaha. The huge body of the Buddha’s teachings were committed to memory and passed down orally from teachers to students since this was the way knowledge was transmitted in India. So it is incorrect to say that we really don’t know what the Buddha said. The writing down of the teachings in the first century BCE merely recorded what had been committed to memory by the monks.

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

13 Ways Meditation Can Help You Relieve Stress (+ 3 Scripts)

Feeling stressed? Take a few moments to focus on your breath rising and falling while sitting comfortably with a straight back in a quiet place. [...]

How to Practice Visualization Meditation: 3 Best Scripts

Visualization is a component of many meditation practices, including loving-kindness meditation (or metta) and the other three Brahma Viharas of compassion, appreciative joy, and equanimity [...]

3 Simple Guided Meditation Scripts for Improving Wellbeing

Guided meditation is a great starting point for those new to meditation and a great way to refresh your practice if you are a seasoned [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (50)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (29)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (4)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (17)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (38)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

3 Mindfulness Exercises Pack (PDF)

Meditation Training

The Surprising Power of Loving-Kindness Meditation

Loving-Kindness Meditation (LKM) is a Buddhist-derived practice that teaches us to cultivate compassion, kindness and warmth toward ourselves and others. This technique can help reduce stress, anxiety, depression, anger, fear, and pain. Based on the principle of metta, which roughly means “positive energy towards others”, this practice is often used in conjunction with other forms of meditation like mindfulness.

This type of meditation is about focusing your attention on one object of concentration, repeating phrases like “May I be happy”. In today’s article, we’ll explain in further detail what loving-kindness meditation is, exploring the origins of the movement, the best ways to practice it, and the scientific evidence backing it up. Later on, we’ll share some great tools to help access the benefits of compassion meditation. But first, let’s define what this meditative method actually entails.

What is Loving-Kindness Meditation?

Loving-Kindness meditation, or sometimes called “Metta” or “Maitrī” meditation, is a proven and well-known meditation practice used to develop our proclivity and ability for kindness. You usually practice this approach by silently repeating a series of mantras to send goodwill, kindness, and warmth to others. There are no expectations or responsibilities in loving-kindness meditation, we don’t do it to achieve an objective or goal rather, we do it to experience life to its fullest and enjoy each experience at the moment. It is a practice that induces and increases the feelings of warmth you have for yourself and others.

Metta or Maitrī is a Sanskrit and Pali word meaning: amity, an active interest in others, benevolence, friendliness, goodwill, and loving-kindness . As a Buddhist meditation practice, Metta is a wonderful complement to other awareness practices. Metta consists of reciting specific words and phrases with a “boundless warm-hearted feeling.” This feeling is not limited to anyone or anything, including family, religion, or social class. We begin with ourselves and gradually extend the wish for happiness to everyone, including ourselves.

It is one form of meditation that allows you to practice forms of meditation through one of the four qualities of love according to Buddhism:

Metta : Friendliness

Mudita : Appreciation and joy

Karuna : Compassion

Upekkha : Equanimity

Like Mindfulness-based meditation practices, Loving-Kindness meditation is an equally flexible practice that can be performed anywhere, at any time throughout your day, life and experiences. The Buddhist path of loving-kindness practice is not about inducing a superficial sappy sense of goodwill for all, it is a practice that is about exploring the practice and process, rather than fulfilling an obligation. Long-time meditators and practices of loving-kindness and compassion meditation will tell you that it is an efficient way of creating motivation and empathy for yourself in everyday life, as well as a way to improve your relationship with self-disclosure. Once it is a regular practice, the positive effects and benefits, like the decrease of anxiety, fear and negative self-esteem, last a lifetime.

Sharon Salzberg and Loving-Kindness Meditation

Salzberg is a famous author and teacher of Buddhist meditation, as well as the co-founder of the Insight Meditation Society, a non-profit organization dedicated to spreading awareness of the benefits of meditation to all. In her essay Mindfulness and Loving-Kindness, she describes loving-kindness as a quality of the heat that gives awareness of the connection we all have. Love-Kindness acknowledges that everyone wishes to be happy and that many people struggle with the question of how to attain it; it addresses our shared vulnerability to suffering and change, which elicits compassion and other positive emotions

Further, on from this, Salzberg also teaches that when we incorporate mindfulness fully into our lives, it leads us to experience a greater understanding of loving-kindness by reducing our habitual natures to fall into easy, but painful, reactions like aversion, delusions and reaching in our minds. Her book, Loving-kindness: The Revolutionary Art of Happiness depicts the lessons she has learned from fellow long-time meditators all over the world and the way they enlightened her. Salzberg reminds us, compassion and directing loving-kindness meditation at a difficult person around you can lead to you feeling all the other difficult emotions like anger, or fear, or resentment – and learn to accept it through better emotional processing.

Tara Brach on Loving-Kindness Meditation

Tara Brach, psychologist and meditation teacher at the Insight Meditation Community, Washington USA has created a career from spreading her knowledge of loving-kindness meditation. With her years of experience in meditation, yoga and mindfulness practices as a trainer, her publications about the benefits of living-kindness are used by many well reputable therapists when helping their clients battle depression, trauma, grief and loss. Brach’s book True Refuge: Finding Peace and Freedom in Your Own Awakened Heart explores her journey to spread awareness around the world that we can tackle stressful daily moments through loving-kindness and compassion meditation.

Science-Backed Reasons to Try Loving-Kindness Meditation

It’s all well and good to tell you the psychological and emotional benefits of the loving-kindness practice, but in order for you to truly understand the benefits of this practice, let’s take a look at some of the ways it is scientifically proven to help our physical health. As we have told you before, loving-kindness and compassion meditation enable us to hone and develop our feelings of goodwill for ourselves and others, kindness and warmth.

Researchers into loving-kindness practices have shown that long-term practices have seen huge benefits. Loving-kindness meditation provides them greater emotional intelligence and subsequent relief from pain and chronic disease.

In a study by psychiatrist Barbara Fredrickson Et Al., where participants participated in a 7-week loving-kindness meditation practice. They reported that they felt an increase in their experiences of emotions like awe, amusement, contentment, gratitude, hope, interest, pride, love and joy. The increase of the experience of these positive emotions was proven then to produce a wider range of internal personal resources in the participant that included a reduction in the symptoms of illness, increased mindfulness and better communication .

Other studies for patients with chronic pain and who underwent a course of loving-kindness meditation reported a demonstrable decrease in anger, pain and psychological distress. According to psychiatrist Makenzie E Tonelli’s study in clinical psychology published in 2014, a brief Loving-Kindness Meditation intervention significantly reduces sufferers’ migraine pain and eases emotional tension that comes with chronic migraines. A pilot trial by psychiatrist David J. Kearney in 2013 shows that a 12-week loving-kindness practice significantly reduces the mental health symptoms of veterans with PTSD.

The Path to Loving-Kindness

Meditators who practice loving-kindness meditation reap long-lasting benefits, including awareness, mental peace, and focus through regular practice. The practice is extremely flexible and straightforward, which makes it accessible to a wide range of settings. Personal – like your everyday mindfulness practice, professional – like your outlook at work and your relationship with your colleagues, and spiritual – like your actual meditation practice.

A growing body of research specifically on Loving-Kindness meditation is also helping social scientists understand the unique benefits that it offers, although the majority of study authors note that more research is required. An article published in 2018 in the Harvard Review of Psychology summarized the evidence for compassion-based interventions and loving-kindness meditation. In their study, the authors concluded that LKM could be helpful in treating chronic pain and borderline personality disorder.

There has been some research that suggests this meditation technique may be useful for the management of afflictive mind states that cause social anxiety, marital conflict, anger, and long-term caregiving stress. In addition, other research suggests that loving kindness meditation can enhance the activation of brain areas that are involved in emotional processing and empathy, leading to a greater feeling of positivity, reducing negativity and a more positive stress response.

Other than the proven studies, you youreslf have probably observed that your mind spends a lot of time focusing on your faults, considering the faults of others, and being quite critical of people in general. Loving-Kindness is a way of off-setting this natural tendency of our minds. Keeping and wishing ourselves and others well is rooted in recognizing that every organism on this earth – person, animal and plant – is just trying to live a happy life, however they choose to do so.

How to Best Practice Loving-Kindness Meditation

The point of loving-kindness meditation is to direct your energy in a benevolent and loving direction to yourself and others. Despite its many benefits, traditional meditation takes practice, as with any technique. People are not used to giving and receiving love at such a level, so it can be difficult and even lead to resistance. Practice of lovingkindness, compassion, sympathetic joy and equanimity can be used as an antidote to mind states such as ferocious rage. Just naming these qualities of heart explicitly and making their role explicit in our practice may help us to recognize them when they arise spontaneously during mindfulness practice.

Carve out some time from your daily schedule and commit to loving-kindness during those minutes every day. There are no right or wrong ways to practice unconditional love, as long as we are committed to self-appreciation. Even a small break at work would work be great! The key is a consistent commitment to Metta or Loving-Kindness meditation during a particular time of the day through mindful attention.

A Mindowl Loving-Kindness Meditation:

Loving-Kindness practice can be done in many ways. The practice of this form of meditation differs according to Buddhist traditions, but each variation uses the same psychological operation at its core. The most popular method begins with wishing yourself well, before sending a well wish to a loved one and a neutral person. Then moving on to more difficult things like sending a wish of love and wellness to someone you consider an enemy, and then all living things on the planet.

We have devised a meditative activity for you to try for yourself, to see how easy this practice is. Because wishing ourselves well can be difficult for some of us, we will start today’s practice by asking you to wish someone you love well.

Start by closing your eyes and taking a few deep breaths.

Let’s begin with someone you love and deeply respect.

Bring this person to mind. Visualise them as clearly as you can. Think of their face, their hands, how they stand.

See if you can slowly repeat some of the traditional phrases used in this practice. If not, you can make up your own phrases.

Slowly repeat the following phrases, but feel free to make up phrases that work for you and your practice.

Say them in silence, to yourself and in complete awareness:

- May you be safe.

- May you be healthy.

- May you be happy.

- May you live with ease in the world.

Try to connect with the emotional experiences of the phrases in your mind as you repeat them slowly. Remember that this is someone you truly want to see happy.

Take a moment to really feel that desire for them to be happy.

When the image of this person fades, gently bring them to your mind again and consciously wish them well.

Slowly repeat in your mind the same phrases in complete awareness:

Whenever you become distracted, bring your focus back to your wish for this person to be happy by bringing the image of them to the front of your mind.

Visualize this person radiant with joy, as if they are experiencing the best day of their lives.

Try putting a smile on your face when you think of this special person — even a fake smile will work for now. Move your lips gently and smile.

As you do that, remember that you also want to be happy. Just like this person, you too want to be healthy, happy, and safe.

Now begin to visualise yourself and silently repeat in complete awareness:

- May I be safe.

- May I be healthy.

- May I be happy.

- May I live with ease in the world.

Okay, get ready to open your eyes.

After each meditation session, it is vital to spare a few minutes for recapitulating the experience. You can maintain a journal for recording how you felt before, after, and during the meditation session. Sharing the feelings helps in enhancing awareness about how the meditation helped you and provides enthusiasm to continue practising.

Ask yourself these questions as you go forward in your practice:

- What was your experience like?

- Was it easier for you to wish someone else well or to wish yourself well?

- What has changed since you started practising?

I hope you got a sense of how this practice can affect your emotions, bring you greater peace in your everyday life. LKM is a meditation practice that involves imagining or actually experiencing an emotional state as an object of attention and mindful awareness.

Don’t worry if it all seems a bit unnatural for now. Over time, it will become more normal to sustain this moment-to-moment awareness. We are training ourselves to think in a new way. Give it some time, as you make your practice a habit you will feel the benefits of lessened intense emotions like rage and misery. As the hours of meditation practice build when you practice at a regular time of day, that moment of awareness will encourage positive relations with those around you and the wide world.

Loving-Kindness Phrases for You

Here are some loving-kindness and compassion phrases to go with your meditation session, if you are having trouble thinking of new ones:

1. May I be strong.

2. May I have the power to accept and forgive.

3. May I live and die in peace.

4. May I be safe.

5. May I love and appreciate others boundlessly.

6. May I achieve what I want and deserve in life.

7. May I have the power to accept my anger and sadness.

8. May I be healthy and happy always.

9. May you be strong.

10. May you have the power to accept and forgive.

11. May you live and die in peace.

12. May you be safe.

13. May you love and appreciate others boundlessly.

14. May you achieve what you want and deserve in life.

15. May you have the power to accept your anger and sadness.

16. May you be healthy and happy always.

Frequently Asked Questions About Loving-Kindness Meditation

We thought it would be a good idea to go over some frequently asked questions before we round off the article. These questions should answer all your remaining questions about Loving-Kindness meditation:

Q. How do I feel Metta?

A. To feel “metta” when we are practising metta or loving-kindness meditation, we must understand what we are cultivating in this practice. In the Sanskrit phrase “Metta Bhavana”, metta means “kindness” and Bhavana means “developing”. In order to properly practise metta Bhavana, you must get to the stage where you are able to learn to be kinder and more loving to not only others but yourself as well. It begins with cultivating self-kindness. We can be kinder to ourselves if we understand our weaknesses, appreciate our strengths, forgive our mistakes, and support ourselves during difficult times.

Q. What is the Metta Prayer?

A. As we saw before, we can practice our metta, or loving-kindness meditation by using a meditation script that includes loving-kindness phrases. You can also use these short phrases at work, throughout the day on your errands, or as you go to bed, as a mindful way to practice on the go. But, there is also a way to use Buddhist Metta Prayers within your meditation and practice to do the same, if you would like to.

Try some of these out for yourself, and see if they work for you:

- My heart fills with loving-kindness. I love myself. May I be content and happy. May I be healthy. May I be peaceful. May I be free.

- May all beings in my vicinity be content and happy. May they be healthy. May they be peaceful. May they be free.

- May my parents be content and happy. May they be healthy. May they be peaceful. May they be free.

- May all my friends be content and happy. May they be healthy. May they be peaceful. May they be free.

- May all my enemies be content and happy. May they be healthy. May they be peaceful. May they be free

- .May all beings in the Universe be content and happy. May they be healthy. May they be peaceful. May they be free.

- If I have hurt anyone, knowingly or unknowingly in thought, word or deed, I ask for their forgiveness.

- If anyone has hurt me, knowingly or unknowingly in thought, word or deed, I extend my forgiveness.

Q. What are Zen Meditation Techniques?

A. Zen meditation, or Zazen literally meaning “seated meditation”, is a meditation technique rooted in Buddhist positive psychology. Zen practice involves regulating attention by “thinking about not thinking”.

There are 5 formally recognsed Buddhist Zen meditation techniques:

- Bompu Zen – Bompu, meaning “ordinary”, zen is a type of meditation suitable to all kinds of peope regardless of circumstance or setting and most importantly, it doesn’t have any overarching spiritual or philosophical dogma that you must follow. When practicing Bompu Zen, the aim is to concentrate, regulate your mind and calm it. Martial arts, Zen arts and all Western meditation are a form of Bompu Zen.

- Gedo Zen – Gedu, meaning “outside way”, is referring to types of meditation that fall outsie of the Buddhist traditions. This may include practicces like Hindu Yoga, Confucian sitting practices, and Christian contemplation based meditation practices.

- Shojo Zen – Shojo, meaning “small vehicle”, is the teaching of transitioning from illusion to enlightenment. The small vehicle is referring to only you, your responsible for your peace of mind . This form of Zen meditation allows you to examine the cause of any suffering and confusion. Shojo Zen believes that some states of mind are better than others and practitioners should strive to achieve equanimity. Through awareness, you learn that you are part of a whole and not separate from anything.

- Daijo Zen – Daijo Zen, also known as the “great practice” is the zen teaching taught by Buddha, that shows you how to find your true nature. Daijo Zen teaches you to break free from the illusions of the world to experience an absolute, indivisible reality. It focuses on the nature of the self and is a practice of enlightenment. Daijo Zen practice allows you to awaken and actualize your true nature through a spiritual path. The more you practice this technique, the more you’ll want to practice it and feel the need to do so. You affect everyone else, and they affect you.

- Saijojo Zen – This zen practice is known as the great practice as the goal is not achieving anything. Proper practice of Saijojojo brings you back to the essence of your true nature. You refrain from wanting, grasping, or trying to achieve something. Its focus is practicing the practice. You’re fully awakened to your pure, true nature with this practice.

Q. What Happens When I do an Act of loving-kindness to Friends and Others?

A. The “science of kindness” refers to the positive effects and benefits of loving-kindness. Oxytocin has been the subject of most research examining why kindness makes us feel better. Occupying a crucial role in the formation of relationships and the formation of trust, oxytocin is sometimes referred to as “the love hormone.” Research suggests that acts of kindness can raise our love hormone levels, shifts in people’s mental states and release more oxytocin throughout the day.

Q. What’s Another Word for Loving-Kindness?

A. Another word for loving-kindness meditating is, of course, Metta meditation as we looked at earlier on in this article! Other words for loving-kindness are;

- Warm-heartedness

- Soft-heartedness

- Tender-heartedness

- Goodness of heart

- Kindness of heart

Q. Is Loving-Kindness the Same as Mercy?

A. The difference between mercy and loving-kindness as terms used in meditation is that mercy is uncountable and forgiving, and loving-kindness is kindness or goodwill that stems from love or grows from love.

In Conclusion

So it is clear to see, loving-kindness meditation can create wonderfully positive daily experiences for you. The Buddhist tradition and Hindu practices like Metta and loving-kindness meditation can be used anywhere, anytime to help you reach a state of peace and equanimity even for a moment in your everyday life. The more you practice this nuanced approach, the better it will feel and the easier it will be to feel positive emotions over time.

The practice of directing warm-heartedness, goodwill, kindness and care to yourself, those around you and the whole world is important. Not only will it stop the negative symptoms of painful emotions like rage, sadness and spite. And, it will alleviate the painful illness symptoms of chronic illness, chronic depression and anxiety. It has been found that with this practice you can balance mental happiness and physical happiness.

If you would like to join our online community to access excellent and game-changing mindfulness-meditation training to help you cope with depression, anxiety or chronic pain, join our online community!

MindOwl Founder – My own struggles in life have led me to this path of understanding the human condition. I graduated with a bachelor’s degree in philosophy before completing a master’s degree in psychology at Regent’s University London. I then completed a postgraduate diploma in philosophical counselling before being trained in ACT (Acceptance and commitment therapy). I’ve spent the last eight years studying the encounter of meditative practices with modern psychology.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

- Greater Good Science Center

- In Education

- Donate to support our work

- Forgiveness

- Mindfulness

- Resilience to Stress

- Self-Compassion

- Sign In/Register

Need help getting started? Unlock your own 28-day journey to a more meaningful life.

Loving-Kindness Meditation

Strengthen feelings of kindness and connection toward others.

- How to do it

- Why to Try It

Time Required

7 minutes daily

How to Do It

This practice draws on a guided meditation created by Eve Ekman Ph.D., LCSW, senior fellow at the Greater Good Science Center.

We recommend listening to the audio of this guided meditation in the player below. We have included a script of the practice to help you follow it yourself or teach it to others.

Body Position

For this practice, it's especially important that we find a comfortable position. This may be easiest lying down or seated.

To help us focus and gain some initial stability, let's bring our attention and awareness to the breath at the belly. Inhale, noticing sensations of breath. Exhale, noticing sensations of breath, as the belly rises and falls.

[30 seconds of silence]

Receiving Loving-Kindness

We'll now shift into this practice of joy, by bringing to mind someone who we really believe has our best interests in their heart. Someone who has extended kindness and support to us. This could be someone we know now or someone from the past. A friend, family member, teacher, colleague.

Choose just one person and bring them to mind as though they were seated right in front of you. Smiling at you.

Imagine them truly wishing for you to be happy, fulfilled. For you to have a life that is flourishing. Imagine them beaming this towards you in their smile, in their eyes. And with your next breaths, inhale and draw in that intention of goodness.

In meditation and visualization practices, we have an opportunity to generate positive emotional states right here and now that we might experience in the world were this person really next to us. Simply through our mind and imagination, it's as though we can call upon this valuable resource right here, right now. So for a couple more breaths, really take in this wish of well, happiness, joy from this person who cherishes us.

[15 seconds of silence]

Sending Loving-Kindness to Loved Ones

Now letting go of the image of this person, notice if in the body there is any emotional residue. Feelings of warmth or goodness. Ways we can identify what it's like to receive this wish of happiness. Then relax into these sensations and feelings for just a couple breaths.

With this feeling of support and happiness, we can now extend this boost of joy to others. Bring to mind someone in your life who could really use an extra boost—a friend, family member, or colleague. And, again, bring them to mind vividly as though they were right in front of you.

And without too many stories, or thoughts, or ideas—just call upon this experience of wishing this person to be truly happy, fulfilled, joyful. As you inhale, draw in this intention. And as you exhale, wish this person happiness, fulfillment, flourishing.

Twice more—inhale, drawing in this intention. And then exhale, sending out.

Release the image of this person. And once again, just notice the sensations in your own body associated with wishing someone else well, generating and extending joy.

Let's bring this practice to a close with three long inhales and three long exhales.

Why You Should Try It

Practicing kindness is one of the most direct routes to happiness: Research suggests that kind people tend to be more satisfied with their relationships and with their lives in general. We all have a natural capacity for kindness, but sometimes we don’t take steps to nurture and express this capacity as much as we could.

Loving-kindness meditation (sometimes called “metta” meditation) is a great way to cultivate our propensity for kindness. It involves mentally sending goodwill, kindness, and warmth towards others by silently repeating a series of mantras.

Why It Works

Loving-kindness meditation increases happiness in part by making people feel more connected to others—to loved ones, acquaintances, and even strangers. Research suggests that when people practice loving-kindness meditation regularly, they start automatically reacting more positively to others—and their social interactions and close relationships become more satisfying. Loving-kindness meditation can also reduce people’s focus on themselves—which can, in turn, lower symptoms of anxiety and depression.

Evidence That It Works

Fredrickson, B. L., Cohn, M. A., Coffey, K. A., Pek, J., & Finkel, S. M. (2008). Open hearts build lives: Positive emotions, induced through loving-kindness meditation, build consequential personal resources . Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95 , 1045-1062.

People who practiced Loving-Kindness Meditation daily for seven weeks reported a steady increase in their daily experience of positive emotions, such as joy, gratitude, contentment, hope, and love. They also reported greater life satisfaction and lower depressive symptoms following the intervention, compared to when they started. People who were on a waitlist to learn the practice didn't report these benefits.

Who Has Tried The Practice?

Participants in the above study were mostly white, held bachelor’s degrees, and had a median annual income of over $85,000. Additional research has engaged members of other groups:

- Israeli adults who attended seven 90-minute weekly classes on Loving-Kindness Meditation and were asked to practice daily “showed significant reductions in self‐criticism and depressive symptoms as well as significant increases in self‐compassion and positive emotions” compared to those on a waitlist.

- For university freshmen in China , 30 minutes of Loving-Kindness Meditation three times a week for four weeks enhanced positive emotions, decreased negative emotions, and improved interpersonal interactions.

- Singaporean individuals with clinically significant symptoms of borderline personality disorder showed reduced negative emotions and feelings of rejection after 10 minutes of Loving-Kindness Meditation.

- Japanese individuals increased in self-compassion and decreased in negative thoughts and emotions after a seven-week program that included Loving-Kindness Meditation, Mindful Breathing , and self-compassion exercises.

- University students in South Korea experienced reductions in self-criticism and psychological distress, along with improvements in self-reassurance and mental health, after participating in a six-week program that included Loving-Kindness Meditation, Body Scan , and Mindful Breathing .

- Female trauma survivors of interpersonal violence (41% non-white) in an American substance abuse treatment and housing program experienced significant reductions in mental health symptoms across a six-week meditation program that included two weeks of Loving-Kindness Meditation for an hour every day.

- Arabic- and Bangla-speaking migrants in Australia experienced reductions in depression, anxiety, and stress after a bilingual group mindfulness program that included Loving-Kindness Meditation, Body Scan , and Mindful Breathing .

Loving-Kindness Meditation is one of the practices included in Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR). Developed by Jon Kabat-Zinn and based on Buddhist teachings , MBSR is a six- to 10-week program that teaches various mindfulness techniques through weekly sessions and homework assignments. Research suggests that MBSR benefits the mental health of various groups, including the following:

- People in different cultures and countries, such as bilingual Latin-American families , university students in China , disadvantaged families in Hong Kong , low-income cyclo drivers in Vietnam , males with generalized anxiety disorder in Iran , Indigenous people in the Republic of Congo , and Aboriginal Australians .

- Women around the world, including pregnant women in China, rural women in India who experienced still-birth, at-risk women in Iran, Muslim women college students in the United Arab Emirates, American survivors of intimate partner violence , and socioeconomically disadvantaged Black women with post-traumatic stress disorder.

- People with certain diseases, such as New Zealanders with rheumatoid arthritis , male patients with heart disease in India, patients with diabetes in South Korea, cancer patients in Canada, breast cancer survivors in China, and HIV-positive individuals in Toronto , San Francisco , Iran , and South Africa .

More research is needed to explore whether, and how, the impact of this practice extends to other groups and cultures.

Keep in Mind

A 2015 study found that MBSR “improved depressive symptoms regardless of affiliation with a religion, sense of spiritually, … sex, or age.” However, other studies suggest that MBSR may not benefit everyone equally:

- When MBSR was administered in Massachusetts correctional facilities , male prisoners experienced less mental health improvement than female prisoners.

- MBSR may not be beneficial in all cultural contexts. For Haitian mental health practitioners and teachers , MBSR contradicted some of their cultural worldviews and everyday practices. Brazilian medical students who participated in MBSR experienced no significant changes in mental health or quality of life.

Adelian, H., Sedigheh, K. S., Miri, S., & Farokhzadian, J. (2021). The effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction on resilience of vulnerable women at drop-in centers in the southeast of Iran . BMC Women's Health, 21 , 1–10.

Arimitsu, K. (2016). The effects of a program to enhance self-compassion in Japanese individuals: A randomized controlled pilot study . The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11 (6), 559–571.

Blignault, I., Saab, H., Woodland, L., Mannan, H., & Kaur, A. (2021). Effectiveness of a community-based group mindfulness program tailored for Arabic and Bangla-speaking migrants . International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 15 , 1–13.

Fogarty, F. A., Booth, R. J., Lee, A. C., Dalbeth, N., & Consedine, N. S. (2019). Mindfulness-based stress reduction with individuals who have rheumatoid arthritis: Evaluating depression and anxiety as mediators of change in disease activity . Mindfulness, 10 (7), 1328–1338.

Gallegos, A. M., Heffner, K. L., Cerulli, C., Luck, P., McGuinness, S., & Pigeon, W. R. (2020). Effects of mindfulness training on posttraumatic stress symptoms from a community-based pilot clinical trial among survivors of intimate partner violence . Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12 (8), 859–868.

Gayner, B., Esplen, M. J., DeRoche, P., Wong, J., Bishop, S., Kavanagh, L., & Butler, K. (2012). A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction to manage affective symptoms and improve quality of life in gay men living with HIV . Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 35 (3), 272–285.

Greeson, J. M., Smoski, M. J., Suarez, E. C., Brantley, J. G., Ekblad, A. G., Lynch, T. R., & Wolever, R. Q. (2015). Decreased symptoms of depression after mindfulness-based stress reduction: Potential moderating effects of religiosity, spirituality, trait mindfulness, sex, and age . The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 21 (3), 166–174.

He, X., Shi, W., Han, X., Wang, N., Zhang, N., & Wang, X. (2015). The interventional effects of loving-kindness meditation on positive emotions and interpersonal interactions . Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 11 , 5.

Hecht, F. M., Moskowitz, J. T., Moran, P., Epel, E. S., Bacchetti, P., Acree, M., Kemeny, M. E., Mendes, W. B., Duncan, L. G., Weng, H., Levy, J. A., Deeks, S. G., & Folkman, S. (2018). A randomized, controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction in HIV infection . Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 73 , 331–339.

Ho, R. T. H., Lo, H. H. M., Fong, T. C. T., & Choi, C. W. (2020). Effects of a mindfulness-based intervention on diurnal cortisol pattern in disadvantaged families: A randomized controlled trial . Psychoneuroendocrinology, 117 , 7.

Hoffman, D. M. (2019). Mindfulness and the cultural psychology of personhood: Challenges of self, other, and moral orientation in Haiti . Culture & Psychology, 25 (3), 302–323.

Jung, H. Y., Lee, H., & Park, J. (2015). Comparison of the effects of Korean mindfulness-based stress reduction, walking, and patient education in diabetes mellitus . Nursing & Health Sciences, 17 (4), 516–525.

Kabat-Zinn, J., De Torrijos, F., Skillings, A. H., Blacker, M., Mumford, G. T., Alvares, D. L., & Rosal, M. C. (2016). Delivery and effectiveness of a dual language (English/Spanish) Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program in the inner city - A seven-year experience: 1992-1999 . Mindfulness & Compassion, 1 (1), 2–13.

Kabat-Zinn, J., & Hanh, T. N. (2009). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness . Delta.

Lavrencic, L. M., Donovan, T., Moffatt, L., Keiller, T., Allan, W., Delbaere, K., & Radford, K. (2021). Ngarraanga giinganay (‘thinking peacefully’): Co-design and pilot study of a culturally-grounded mindfulness-based stress reduction program with older First Nations Australians . Evaluation and Program Planning, 87 , 12.

Le, T. N. (2017). Cultural considerations in a phenomenological study of mindfulness with Vietnamese youth and cyclo drivers . International Perspectives in Psychology: Research, Practice, Consultation, 6 (4), 246–260.

Lee, M. Y., Zaharlick, A., & Akers, D. (2017). Impact of meditation on mental health outcomes of female trauma survivors of interpersonal violence with co-occurring disorders: A randomized controlled trial . Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 32 (14), 2139–2165.

Li, J., & Qin, X. (2021). Efficacy of mindfulness‐based stress reduction on fear of emotions and related cognitive behavioral processes in Chinese university students: A randomized controlled trial . Psychology in the Schools , 1–17.

Majid, S. A., Seghatoleslam, T., Homan, H. A., Akhvast, A., & Habil, H. (2012). Effect of mindfulness based stress management on reduction of generalized anxiety disorder . Iranian Journal of Public Health, 41 (10), 24–28.

McIntyre, T., Elkonin, D., de Kooker, M., & Magidson, J. F. (2018). The application of mindfulness for individuals living with HIV in South Africa: A hybrid effectiveness-implementation pilot study . Mindfulness, 9 (3), 871–883.

Neto, A. D., Lucchetti, A. L. G., Ezequiel, O. S., & Lucchetti, G. (2020). Effects of a required large-group mindfulness meditation course on first-year medical students’ mental health and quality of life: A randomized controlled trial . Journal of General Internal Medicine, 35 (3), 672–678.

Noh, S. & Cho, H. (2020). Psychological and physiological effects of the mindful lovingkindess compassion program on highly self-critical university students in South Korea . Frontiers in Psychology, 11 , 2628.

Parswani, M. J., Sharma, M. P., & Iyengar, S. S. (2013). Mindfulness-based stress reduction program in coronary heart disease: A randomized control trial . International Journal of Yoga, 6 (2), 111.

Roberts, L. R., & Montgomery, S. B. (2016). Mindfulness-based intervention for perinatal grief in rural India: Improved mental health at 12 months follow-up . Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 37 (12), 942–951.

Samuelson, M., Carmody, J., Kabat-Zinn, J., & Bratt, M. A. (2007). Mindfulness-based stress reduction in Massachusetts correctional facilities . The Prison Journal, 87 (2), 254–268.

SeyedAlinaghi, S., Jam, S., Foroughi, M., Imani, A., Mohraz, M., Djavid, G. E., & Black, D. S. (2012). Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction delivered to human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients in Iran: effects on CD4⁺ T lymphocyte count and medical and psychological symptoms . Psychosomatic Medicine, 74 (6), 620–627.

Shahar, B., Szsepsenwol, O., Zilcha‐Mano, S., Haim, N., Zamir, O., Levi‐Yeshuvi, S., & Levit‐Binnun, N. (2015). A wait‐list randomized controlled trial of loving‐kindness meditation programme for self‐criticism . Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 22 (4), 346–356.

Speca, M., Carlson, L. E., Goodey, E., & Angen, M. (2000). A randomized, wait-list controlled clinical trial: The effect of a mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction program on mood and symptoms of stress in cancer outpatients . Psychosomatic Medicine, 62 (5), 613–622.

Stell, A. J., & Farsides, T. (2016). Brief loving-kindness meditation reduces racial bias, mediated by positive other-regarding emotions . Motivation and Emotion, 40 (1), 140–147.

Thomas, J., Raynor, M., & Bahussain, E. (2016). Stress reactivity, depressive symptoms, and mindfulness: A Gulf Arab perspective . International Perspectives in Psychology: Research, Practice, Consultation, 5 (3), 156–166.

Vinesett, A. L., Whaley, R. R., Woods-Giscombe, C., Dennis, P., Johnson, M., Li, Y., Mounzeo, P., Baegne, M., & Wilson, K. H. (2017). Modified African Ngoma healing ceremony for stress reduction: A pilot study . The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 23 (10), 800–804.

Waldron, E. M., & Burnett-Zeigler, I. (2021). The impact of participation in a mindfulness-based intervention on posttraumatic stress symptomatology among Black women: A pilot study . Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 14 (1), 29–37.

Williams, J. M., & Kabat-Zinn, J. (2013). Mindfulness: Diverse perspectives on its meaning, origins and applications at the intersection of science and dharma . Routledge.

Zhang, J., Cui, Y., Zhou, Y., & Li, Y. (2019). Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on prenatal stress, anxiety and depression . Psychology, Health & Medicine, 24 (1), 51–58.

Zhang, J., Zhou, Y., Feng, Z., Fan, Y., Zeng, G., & Wei, L. (2017). Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on posttraumatic growth of Chinese breast cancer survivors . Psychology, Health & Medicine, 22 (1), 94–109.

Loving-kindness meditation invites us to cultivate warm feelings of love and kindness toward increasingly distant people, and ultimately all living creatures. How concerned are you about your community, your fellow citizens, and all of mankind? Take the Connection to Humanity quiz to find out.

Pathway to Happiness

Ready to try this practice.

Find it on your Pathway to Happiness Already started Your Pathway to Happiness? Log In here .

Comments and Reviews

Theresa Worrell March 20, 2024

Woke up late, so I have a rushed morning. This meditation calmed me and I feel balanced

Yolanda S Trujillo March 5, 2024

Rena elizabeth smith march 3, 2024, dora february 20, 2024.

Our motivation, when we begin to practise it essential to be sure about our motivation. Altruistic or self-centred, vast or limited, that will give the journey we are about to take a positive or negative direction and thus determine its result. THANK YOU Thank you with all my heart for this meditation, I am also sending you a stream of love.

LC Conner February 6, 2024

Caroline mckinnon january 19, 2024.

My concentration was not focused well today. "oh this again" so I tuned out a lot. Also felt critical of the speaker's voice which didn't sound natural, as if reading a script. The directions for breathe in and out were annoying.

The Greater Good Toolkit

Made in collaboration with Holstee, this tookit includes 30 science-based practices for a meaningful life.

Write a Review

If you'd like to leave a review or comment, please login —it's quick and free!

Other Practices Like This

Compassion meditation.

Strengthen feelings of concern for the suffering of others.

Feeling Connected

A writing exercise to foster connection and kindness.

Shared Identity

How to encourage generosity by finding commonalities between people.

Body Scan Meditation

Feeling tense? Feel your body relax as you try this practice.

Walking Meditation

Turn an everyday action into a tool for mindfulness and stress reduction.

Developed in partnership with

Most Talked About Practices

Change your outlook on a negative event — and enjoy less stress.

A way to tune into the positive events in your life.

Top Rated Practices

Ask kids to make a verbal pledge to be honest.

Teach kids how to practice to help them achieve their goals.

Already have an account?

Registration.

There are some errors in your form.

Register using your email address!

- Accept Terms of Use

- Email me monthly updates about Greater Good in Action practices!

Login with facebook Login with Twitter Login with email

Need to create an account instead? Register here

Sign in using your email address:

Please send me monthly Greater Good in Action updates!

Lost your password?

Lost password?

Please enter your email address. You will receive a link to create a new password via email.

Our Privacy Policy has changed!

Please take a moment to review our updated Privacy Policy .

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Practice Loving Kindness Meditation

Elizabeth Scott, PhD is an author, workshop leader, educator, and award-winning blogger on stress management, positive psychology, relationships, and emotional wellbeing.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Elizabeth-Scott-MS-660-695e2294b1844efda01d7a29da7b64c7.jpg)

Sara Clark is an EYT 500-hour certified Vinyasa yoga and mindfulness teacher, lululemon Global Yoga Ambassador, model, and writer.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Sara-Clark-1000-ec845b3e32314f9782370ec43ea68e82.jpg)

Loving kindness meditation (LKM) is a popular self-care technique that can be used to boost well-being and reduce stress. Those who regularly practice loving kindness meditation are able to increase their capacity for forgiveness, connection to others, self-acceptance, and more.

This technique is not easy as you are asking yourself to send kindness your way or to others. It often takes practice to allow yourself to receive your own love or to send it.

Benefits of Loving Kindness Meditation

During loving kindness meditation, you focus benevolent and loving energy toward yourself and others. There are many well-documented benefits of traditional meditation , but as with other techniques, this form of meditation takes practice. It can be difficult and sometimes leads to resistance since the average person is not used to this level of giving and receiving love.

Press Play for Advice On Meditation

Hosted by therapist Amy Morin, LCSW, this episode of The Verywell Mind Podcast , featuring 'Good Morning America' anchor Dan Harris, shares a quick step-by-step process for beginners to try meditation. Click below to listen now.

Follow Now : Apple Podcasts / Spotify / Google Podcasts

Emerging research specifically on LKM is also helping social scientists to understand the unique benefits that it provides, although most study authors note that more research is needed.

For example, a study published in the 2018 July/August issue of the Harvard Review of Psychology provided an overview of scientific evidence related to loving-kindness meditation and other compassion-based interventions.

Study authors concluded that LKM may be beneficial in the treatment of chronic pain and borderline personality disorder but further evidence is needed to confirm these promising effects.

Some published studies have noted that this meditation technique may be useful in the management of social anxiety, marital conflict, anger, and coping with the strains of long-term caregiving. And other research has suggested that loving kindness meditation can enhance the activation of brain areas that are involved in emotional processing and empathy to boost a sense of positivity and reduce negativity.

While more research is needed to confirm the full extent of LKM benefits, there are no risks or costs associated with the practice. So if you choose to give this meditative practice a try, you've got nothing to lose except for a few quiet moments in your day.

There are different ways to practice this form of meditation, each based on different Buddhist traditions, but each variation uses the same core psychological operation. During your meditation, you generate kind intentions toward certain targets including yourself and others.

The following is a simple and effective loving kindness meditation technique to try.

- Carve out some quiet time for yourself (even a few minutes will work) and sit comfortably. Close your eyes, relax your muscles, and take a few deep breaths.

- Imagine yourself experiencing complete physical and emotional wellness and inner peace. Imagine feeling perfect love for yourself, thanking yourself for all that you are, knowing that you are just right—just as you are. Focus on this feeling of inner peace, and imagine that you are breathing out tension and breathing in feelings of love.

- Repeat three or four positive, reassuring phrases to yourself. These messages are examples, but you can also create your own:

- May I be happy

- May I be safe

- May I be healthy, peaceful, and strong

- May I give and receive appreciation today

Next, bask in feelings of warmth and self-compassion for a few moments. If your attention drifts, gently redirect it back to these feelings of loving kindness. Let these feelings envelop you.

You can choose to either stay with this focus for the duration of your meditation or begin to shift your focus to loved ones in your life. Begin with someone who you are very close to, such as a spouse, a child, a parent, or a best friend. Feel your gratitude and love for them. Stay with that feeling. You may want to repeat the reassuring phrases.

Once you've held these feelings toward that person, bring other important people from your life into your awareness, one by one, and envision them with perfect wellness and inner peace. Then branch out to other friends, family members, neighbors, and acquaintances. You may even want to include groups of people around the world.

Extend feelings of loving kindness to people around the globe and focus on a feeling of connection and compassion. You may even want to include those with whom you are in conflict to help reach a place of forgiveness or greater peace.

When you feel that your meditation is complete, open your eyes. Remember that you can revisit the wonderful feelings you generated throughout the day. Internalize how loving kindness meditation feels, and return to those feelings by shifting your focus and taking a few deep breaths.

Tips for a More Effective LKM Practice

When you first begin your loving kindness practice, use yourself as the sole subject during meditation. As you get more comfortable with the imagery and loving phrases, begin to add the visualization of others into your practice.

Finally, direct loving kindness meditation toward difficult people in your life. This last arm of LKM boosts feelings of forgiveness and helps you to let go of rumination for an increased sense of inner peace. As you develop a regular practice of meditation, you may want to set a timer with a gentle alarm if you're concerned about spending too much time in focus.

Lastly, remember that this meditation can be practiced in many different ways. The method outlined above is a sample of how you might choose to begin. You may come up with your own loving kindness meditation technique that works better for you. As long as you focus your attention in a way that promotes feelings of loving kindness, you can expect to gain benefits from the practice.

Learn about the 21 best meditation podcasts .