Winter 2024

Syria’s Displaced: A Photo Essay

Za’atari refugee camp houses some 80,000 residents, making it one of the largest cities in Jordan. Views from inside the wall.

In late July 2012, the first Syrian families arrived at the Za’atari refugee camp, a barren strip of land twelve kilometers from the Syrian border and seventy kilometers from the Jordanian capital, Amman.

At the time, Andrew Harper, UNHCR’s Country Representative in Jordan said, “We are the first to admit that it is a hot desolate location. Nobody wants to put a family who has already suffered so much in a tent, in the desert, but we have no choice.”

By the end of that summer, the camp housed over 28,000 refugees. In March 2013, 156,000 people were living in a space designed for 113,000. The windswept camp had become Jordan’s fourth largest city, and UNHCR’s second largest camp after Dadaab in Kenya, currently home to about 328,000 displaced Somalis. Today, of the close to 700,000 registered Syrian refugees in Jordan, Za’atari houses about 80,000 residents.

In July 2013 U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry arrived by helicopter to visit the camp. Agence France-Presse photographer Mandel Ngan’s aerial photographs of Za’atari became the defining images of the visit. In these images, people appear as dots, little specks in brown sand against an undulating grid of tents and container homes, with no end in sight. The photographs evoked the enormity of the Syrian refugee crisis. They were powerful, but also impersonal.

As the Za’atari camp grew, the camp’s security architecture evolved.

Just past the checkpoint entrance is the camp’s main road bordered on one side by a barbed-wire security wall that stands 2.44 meters high and 120 meters long. This is the largest and most prominent in a series of walls encircling service areas and UNHCR buildings.

In late December 2013 and early January 2014, along with three experienced photographers, I visited the camp to capture the daily life of its residents. Our aim was to tell a story about the camp through images and to paste these photos on the security wall, transforming the concrete barrier into a massive narrative canvas. The photographic display would be visible to both the subjects of the photographs and to visitors, diplomats, and other actors who would decide the fate of the refugees living within.

Rather than unidentifiable specks in brown sand, we wanted Za’atari’s refugees to appear epic, but also to show their humanity and dignity. The project used the visual language of photojournalism but required consent and collaboration from the camp’s residents. In addition, the images had to strike a particular note: they had to negotiate the space between the grim reality of the camp and the project’s intention to use art as an affirming medium in spaces of disenfranchisement and trauma.

When escaping violence, refugees flee with what they can carry. Many left behind their family photographs. So in addition to the creation of the security wall mural, our team of photographers turned one tent into a photo studio. Refugees were invited to have their portraits taken alone or with someone—or something—they loved. One man brought his shisha; a young boy, his blanket. Four girls held their schoolbooks. Mothers carried babies. A father stood behind his son. The photo studio provided a neutral space where residents could momentarily escape their refugee status. Participants were treated as clients, not subjects. They chose how they would pose and look. We printed hundreds of these portraits and distributed them for free on the spot. I also selected a few images for the security wall mural.

In March 2014, we pasted the photographs on the wall and it came alive.

People drove by honking their horns, giving the thumbs-up sign. Some walked by in careful contemplation, taking in each picture. Others, however, were less positive. One refugee, a former fighter who had first agreed to be photographed outside his tent, became self-conscious once he saw his image enlarged. We covered the picture at his request. The Jordanian authorities (who had not been given prior review) grew agitated during the installation process. They questioned whether some of the images portrayed the camp, and by extension, the host country, in a negative light. For example, a photo of a man holding up X-rays of injuries he had suffered in Syria could be mistaken for injuries received at the camp. Another depicting the daily ritual of bread distribution could give the impression, authorities said, that everyone in the camp was poor and hungry.

The pictures were designed to have a six-month life span. But the majority of the nearly one hundred images still remain on the security wall today. They are discolored and frayed, washed out by the passage of time, yet the faces of the refugees are still discernible on the concrete slabs. Their photographs are now testament to the duration of the refugee crisis and the permanence of the camp.

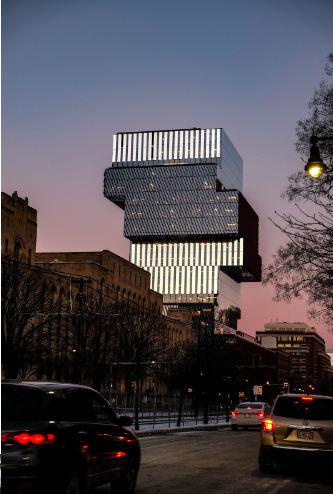

Nina Berman is a documentary photographer, author of Purple Hearts: Back from Iraq (Trolley Books, 2004), and Homeland (Trolley Books, 2008), and an associate professor at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. The Za’atari project was produced by Nina Berman and NOOR images, and photographed by Stanley Greene, Alixandra Fazzina, Andrea Bruce, and Nina Berman. Curator Sam Barzilay assisted with installation.

CAPTION -->

Sign up for the Dissent newsletter:

Socialist thought provides us with an imaginative and moral horizon.

For insights and analysis from the longest-running democratic socialist magazine in the United States, sign up for our newsletter:

Photo essay: In DRC, women refugees rebuild lives, with determination and hope

Date: 18 May 2016

Burundi’s ongoing political turmoil has caused hundreds of thousands to flee their homes and seek shelter in neighbouring Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). At the Lusenda refugee camp, which is home to more than 16,000 refugees, the majority are women and girls. Hundreds of refugees have come to the Safe Haven multipurpose centres for protection and economic and social empowerment, established by UN Women [ 1 ]. Here’s a glimpse into daily life at the camp and the centres.

When her husband was arrested during the 2015 political crisis, Luscie, 32, fled the Bujumbura province in Burundi with her eight children, with only the clothes on their backs. Since then they have been refugees at the Lusenda camp in DRC.

Photo: UN Women/Catianne Tijerina

With the help of a camp worker, Luscie, right, hauls rock and clay from a river back to a UN Women multipurpose centre for use in building a clay stove. UN Women has established three Safe Haven multipurpose centres, which offer psychosocial counselling, referrals, skills training and cash-for-work programmes.

Luscie, left, and Marita, right, work to make a handmade clay stove. At the multipurpose centres, they’ve learned to make stoves which help cut the cost of feeding their families. “It takes less charcoal and the surface stays hot longer,” says Marita.

Also at the multipurpose centre, Luscie, far right, joined the collective efforts to cultivate vegetables for a shared profit. Her goal: to make enough money to replace her children’s torn clothes.

Luscie with her children. Many women in the camp are widows and have had to become heads of their households, taking on the responsibility for the children, the sick or the elderly. They need services and resources. Through the multipurpose centres, nearly 300 women in Lusenda have gained temporary employment through cash-for-work programmes. Another 80 women and girls acquired soap-making skills and 38 learned how to operate a camp restaurant.

Women who are part of the agriculture programme gather early to attend to the crops they cultivate collectively.

The women learn how to plant many different kinds of crops. After working in the collective, some of them are able to plant and harvest vegetables outside of their temporary houses at the refugee camp.

With UN Women’s assistance, in 2015, 264 women refugees contributed to the camp’s food security after being trained to grow vegetables.

After finishing their morning’s work, the women often walk back to the UN Women multipurpose centre, where they can also find information on women’s rights and receive psychological support and counselling. In the camp, refugee women face social isolation, harassment, domestic violence and other types of sexual and gender-based violence.

Celestine, a refugee at the Lusenda camp, leads a dance performance organized by youth at a multipurpose centre in October 2015. The centres also serve as safe spaces for women to feel comfortable and express themselves, without the fear of judgement or harm.

In the midst of all the daily challenges, women attending the dance performance have a moment to laugh together. One of the goals of the centres is to help refugee women socialize, make new friends and rebuild their social networks. “We should not give up but fight for a better life for our children!” say the women in the Lusenda refugee camp.

UN Women works so that women and girls in protracted crises have access to the services they need to ensure their recovery and develop their resilience to future crises.

For larger-format images, you can also find this photo essay cross-posted on Medium .

For more information on Women in Humanitarian Action, visit our In Focus section .

[1] The UN Women multipurpose centres are run in partnership with the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), its local partner Rebuild Hope for Africa and the Women Refugee Committee, with funding from the Government of Japan.

- ‘One Woman’ – The UN Women song

- UN Under-Secretary-General and UN Women Executive Director Sima Bahous

- Kirsi Madi, Deputy Executive Director for Resource Management, Sustainability and Partnerships

- Nyaradzayi Gumbonzvanda, Deputy Executive Director for Normative Support, UN System Coordination and Programme Results

- Guiding documents

- Report wrongdoing

- Programme implementation

- Career opportunities

- Application and recruitment process

- Meet our people

- Internship programme

- Procurement principles

- Gender-responsive procurement

- Doing business with UN Women

- How to become a UN Women vendor

- Contract templates and general conditions of contract

- Vendor protest procedure

- Facts and Figures

- Global norms and standards

- Women’s movements

- Parliaments and local governance

- Constitutions and legal reform

- Preguntas frecuentes

- Global Norms and Standards

- Macroeconomic policies and social protection

- Sustainable Development and Climate Change

- Rural women

- Employment and migration

- Facts and figures

- Creating safe public spaces

- Spotlight Initiative

- Essential services

- Focusing on prevention

- Research and data

- Other areas of work

- UNiTE campaign

- Conflict prevention and resolution

- Building and sustaining peace

- Young women in peace and security

- Rule of law: Justice and security

- Women, peace, and security in the work of the UN Security Council

- Preventing violent extremism and countering terrorism

- Planning and monitoring

- Humanitarian coordination

- Crisis response and recovery

- Disaster risk reduction

- Inclusive National Planning

- Public Sector Reform

- Tracking Investments

- Strengthening young women's leadership

- Economic empowerment and skills development for young women

- Action on ending violence against young women and girls

- Engaging boys and young men in gender equality

- Sustainable development agenda

- Leadership and Participation

- National Planning

- Violence against Women

- Access to Justice

- Regional and country offices

- Regional and Country Offices

- Liaison offices

- UN Women Global Innovation Coalition for Change

- Commission on the Status of Women

- Economic and Social Council

- General Assembly

- Security Council

- High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development

- Human Rights Council

- Climate change and the environment

- Other Intergovernmental Processes

- World Conferences on Women

- Global Coordination

- Regional and country coordination

- Promoting UN accountability

- Gender Mainstreaming

- Coordination resources

- System-wide strategy

- Focal Point for Women and Gender Focal Points

- Entity-specific implementation plans on gender parity

- Laws and policies

- Strategies and tools

- Reports and monitoring

- Training Centre services

- Publications

- Government partners

- National mechanisms

- Civil Society Advisory Groups

- Benefits of partnering with UN Women

- Business and philanthropic partners

- Goodwill Ambassadors

- National Committees

- UN Women Media Compact

- UN Women Alumni Association

- Editorial series

- Media contacts

- Annual report

- Progress of the world’s women

- SDG monitoring report

- World survey on the role of women in development

- Reprint permissions

- Secretariat

- 2023 sessions and other meetings

- 2022 sessions and other meetings

- 2021 sessions and other meetings

- 2020 sessions and other meetings

- 2019 sessions and other meetings

- 2018 sessions and other meetings

- 2017 sessions and other meetings

- 2016 sessions and other meetings

- 2015 sessions and other meetings

- Compendiums of decisions

- Reports of sessions

- Key Documents

- Brief history

- CSW snapshot

- Preparations

- Official Documents

- Official Meetings

- Side Events

- Session Outcomes

- CSW65 (2021)

- CSW64 / Beijing+25 (2020)

- CSW63 (2019)

- CSW62 (2018)

- CSW61 (2017)

- Member States

- Eligibility

- Registration

- Opportunities for NGOs to address the Commission

- Communications procedure

- Grant making

- Accompaniment and growth

- Results and impact

- Knowledge and learning

- Social innovation

- UN Trust Fund to End Violence against Women

- About Generation Equality

- Generation Equality Forum

- Action packs

- High contrast

- Press Centre

Search UNICEF

The things we hold on to: refugee children carry memories of home, no matter where they’re from or why they left, refugee and displaced children are children first..

What would you take if you had only hours – even minutes – to decide before being forced to flee your home? And what if you didn’t know how long you’d be gone, or what would be left of your home should you return?

These are questions that a growing number of refugees have had to confront as new waves of violence and protracted crises worldwide uproot millions from their homes. But even as the global refugee population has more than doubled in the past decade, refugee and displaced children – from Afghanistan to South Sudan to Syria to Ukraine – have something important in common: They all have equal rights. And they need our support to grow, to learn and to thrive in safety.

Zaina took a framed photograph of her late father when she fled Syria for the Za’atari refugee camp in Jordan. “I wanted to bring this with me when I came here. It was hanging on the wall. I saw my mother putting stuff together, so I ran to the photo and took it off the wall and put it in her bag,” Zaina says. “I have many memories of all the toys he gave me. I couldn’t bring those with me.”

Maksym fled eastern Ukraine with his mother and brother as the war escalated. “[We] had to flee because they were shelling,” Maksym says. He was supposed to play his first concert on the piano the week he left. His musical score was among the few precious things he was able to pack and take with him.

Ayoub packed a set of spoons when he fled Syria. “I wanted to take them with me as a memory, so I grabbed them as we were leaving the house and I carried them the whole way here,” says Ayoub, now in the Za’atari refugee camp in Jordan. “I used to eat my meals with them back at home, so I thought that I’m going to need them to eat when I come to the camp.”

Andaili holds up her family photo album, her most prized possession, which she brought from Venezuela to her new home in Colombia.

Nilufar is Afghan by descent but has never lived in Afghanistan. She was born a refugee in Pakistan before her family sought safety in Iran, Turkey, Greece, and then in Serbia.

“I don't have any more photographs, just this one,” she says, carefully unwrapping a framed photo of herself. “This is me wearing the religious headscarf I got from my school when I completed the third grade in Iran. All the children got the same headscarves back then.”

Yonas left his home in Eritrea due to instability in the country. He crossed Ethiopia, Sudan and Libya, hitching rides in cars and trucks. He was then evacuated by UNHCR (the UN Refugee Agency) to Niamey, Niger. He found a yellow hat while he was in Libya. “Since then, I keep it with me, even in Niger!” he says. “It protected me during cold nights. Now it has become special to me.”

Agnes holds her baby boy’s knitted hat in the Bidibidi refugee settlement, north-western Uganda. She fled South Sudan, in the midst of conflict, where the war and instability had created a severe food crisis. Her baby contracted malaria during the journey to Uganda. He passed away just days after their arrival at the settlement.

Fourteen-year-old Rohingya refugee Tasmin Akter holds her favourite book of poetry at a UNICEF-supported project in Kutupalong refugee camp, Cox’s Bazar District, Bangladesh. “When I take a decision for myself, like deciding to read a Bengali poem at home, I feel strong,” says Tasmin.

“I brought this dog,” says Shatha, 15, as she holds the small toy in her hands. She was 9 when she left Syria. “When we had to leave, I had so many toys to choose from, but he was my favourite.” She says she held him the whole way to the Za’atari camp. “I never let go of my dog so he could protect me. My toy dog will always be with me. I’ll tell my children my whole life story and his – because it’s the same as mine.”

Tatiana brought her dog with her to a temporary refugee centre in Moldova near the border with Ukraine. “I’m worried about my sister who’s hospitalized in Ukraine, and my brother,” Tatiana says. “I just want to go back home. I don’t want there to be a war.”

Reaching safety is just the start. Once out of harm’s way, refugee children and their families need opportunities to heal, learn and thrive. UNICEF stands in solidarity with all refugee children – because wherever they come from, whenever they’re forced to flee, all refugee children have equal rights. They all need our support. Read more about UNICEF’s work for migrant and displaced children and six actions that must be taken to achieve equal rights and opportunities for all refugee children.

Related topics

More to explore.

Nearly 37 million children displaced worldwide – highest number ever recorded

Migrant and displaced children

Children on the move are children first

Six actions for refugee children

Ensuring equal rights and opportunities for all refugee children

UNICEF in emergencies

Humanitarian action is central to UNICEF’s mandate and realizing the rights of every child

Search the United Nations

- Policy and Funding

- Recover Better

- Disability Inclusion

- Secretary-General

- Financing for Development

- ACT-Accelerator

- Member States

- Health and Wellbeing

- Policy and Guidance

- Vaccination

- COVID-19 Medevac

- i-Seek (requires login)

- Awake at Night podcast

COVID-19 photo essay: We’re all in this together

About the author, department of global communications.

The United Nations Department of Global Communications (DGC) promotes global awareness and understanding of the work of the United Nations.

23 June 2020 – The COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated the interconnected nature of our world – and that no one is safe until everyone is safe. Only by acting in solidarity can communities save lives and overcome the devastating socio-economic impacts of the virus. In partnership with the United Nations, people around the world are showing acts of humanity, inspiring hope for a better future.

Everyone can do something

Rauf Salem, a volunteer, instructs children on the right way to wash their hands, in Sana'a, Yemen. Simple measures, such as maintaining physical distance, washing hands frequently and wearing a mask are imperative if the fight against COVID-19 is to be won. Photo: UNICEF/UNI341697

Creating hope

Venezuelan refugee Juan Batista Ramos, 69, plays guitar in front of a mural he painted at the Tancredo Neves temporary shelter in Boa Vista, Brazil to help lift COVID-19 quarantine blues. “Now, everywhere you look you will see a landscape to remind us that there is beauty in the world,” he says. Ramos is among the many artists around the world using the power of culture to inspire hope and solidarity during the pandemic. Photo: UNHCR/Allana Ferreira

Inclusive solutions

Wendy Schellemans, an education assistant at the Royal Woluwe Institute in Brussels, models a transparent face mask designed to help the hard of hearing. The United Nations and partners are working to ensure that responses to COVID-19 leave no one behind. Photo courtesy of Royal Woluwe Institute

Humanity at its best

Maryna, a community worker at the Arts Centre for Children and Youth in Chasiv Yar village, Ukraine, makes face masks on a sewing machine donated by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and civil society partner, Proliska. She is among the many people around the world who are voluntarily addressing the shortage of masks on the market. Photo: UNHCR/Artem Hetman

Keep future leaders learning

A mother helps her daughter Ange, 8, take classes on television at home in Man, Côte d'Ivoire. Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, caregivers and educators have responded in stride and have been instrumental in finding ways to keep children learning. In Côte d'Ivoire, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) partnered with the Ministry of Education on a ‘school at home’ initiative, which includes taping lessons to be aired on national TV and radio. Ange says: “I like to study at home. My mum is a teacher and helps me a lot. Of course, I miss my friends, but I can sleep a bit longer in the morning. Later I want to become a lawyer or judge." Photo: UNICEF/UNI320749

Global solidarity

People in Nigeria’s Lagos State simulate sneezing into their elbows during a coronavirus prevention campaign. Many African countries do not have strong health care systems. “Global solidarity with Africa is an imperative – now and for recovering better,” said United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres. “Ending the pandemic in Africa is essential for ending it across the world.” Photo: UNICEF Nigeria/2020/Ojo

A new way of working

Henri Abued Manzano, a tour guide at the United Nations Information Service (UNIS) in Vienna, speaks from his apartment. COVID-19 upended the way people work, but they can be creative while in quarantine. “We quickly decided that if visitors can’t come to us, we will have to come to them,” says Johanna Kleinert, Chief of the UNIS Visitors Service in Vienna. Photo courtesy of Kevin Kühn

Life goes on

Hundreds of millions of babies are expected to be born during the COVID-19 pandemic. Fionn, son of Chloe O'Doherty and her husband Patrick, is among them. The couple says: “It's all over. We did it. Brought life into the world at a time when everything is so uncertain. The relief and love are palpable. Nothing else matters.” Photo: UNICEF/UNI321984/Bopape

Putting meals on the table

Sudanese refugee Halima, in Tripoli, Libya, says food assistance is making her life better. COVID-19 is exacerbating the existing hunger crisis. Globally, 6 million more people could be pushed into extreme poverty unless the international community acts now. United Nations aid agencies are appealing for more funding to reach vulnerable populations. Photo: UNHCR

Supporting the frontlines

The United Nations Air Service, run by the World Food Programme (WFP), distributes protective gear donated by the Jack Ma Foundation and Alibaba Group, in Somalia. The United Nations is using its supply chain capacity to rapidly move badly needed personal protective equipment, such as medical masks, gloves, gowns and face-shields to the frontline of the battle against COVID-19. Photo: WFP/Jama Hassan

S7-Episode 2: Bringing Health to the World

“You see, we're not doing this work to make ourselves feel better. That sort of conventional notion of what a do-gooder is. We're doing this work because we are totally convinced that it's not necessary in today's wealthy world for so many people to be experiencing discomfort, for so many people to be experiencing hardship, for so many people to have their lives and their livelihoods imperiled.”

Dr. David Nabarro has dedicated his life to global health. After a long career that’s taken him from the horrors of war torn Iraq, to the devastating aftermath of the Indian Ocean tsunami, he is still spurred to action by the tremendous inequalities in global access to medical care.

“The thing that keeps me awake most at night is the rampant inequities in our world…We see an awful lot of needless suffering.”

:: David Nabarro interviewed by Melissa Fleming

Brazilian ballet pirouettes during pandemic

Ballet Manguinhos, named for its favela in Rio de Janeiro, returns to the stage after a long absence during the COVID-19 pandemic. It counts 250 children and teenagers from the favela as its performers. The ballet group provides social support in a community where poverty, hunger and teen pregnancy are constant issues.

Radio journalist gives the facts on COVID-19 in Uzbekistan

The pandemic has put many people to the test, and journalists are no exception. Coronavirus has waged war not only against people's lives and well-being but has also spawned countless hoaxes and scientific falsehoods.

Yemeni refugees seek shelter in Djibouti (Photo Essay)

Oualid Khelifi, Al Jazeera, 14 Nov 2015

URL: http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/inpictures/2015/11/yemeni-refugees-seek-shelter-djibouti-151113094929289.html

Available layouts.

Yemeni refugees seek shelter in Djibouti (Photo Essay)

Oualid Khelifi, Al Jazeera, 14 Nov 2015

URL: http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/inpictures/2015/11/yemeni-refugees-seek-shelter-djibouti-151113094929289.html

Available layouts.

About . Click to expand section.

- Our History

- Team & Board

- Transparency and Accountability

What We Do . Click to expand section.

- Cycle of Poverty

- Climate & Environment

- Emergencies & Refugees

- Health & Nutrition

- Livelihoods

- Gender Equality

- Where We Work

Take Action . Click to expand section.

- Attend an Event

- Partner With Us

- Fundraise for Concern

- Work With Us

- Leadership Giving

- Humanitarian Training

- Newsletter Sign-Up

Donate . Click to expand section.

- Give Monthly

- Donate in Honor or Memory

- Leave a Legacy

- DAFs, IRAs, Trusts, & Stocks

- Employee Giving

Photo essay: The reality for those fleeing Ukraine

More than 1 million people have fled Ukraine in just the first week of conflict, and thousands more are on the move.

Mar 4, 2022 | By: Kieran McConville

In search of safety, more than 1 million people fled Ukraine in the last week and thousands more are on the move. The UNHCR estimates it could be the biggest refugee crisis of the century.

Most of the refugees crossing the border into Poland, Slovakia, Romania, Hungary, and Moldova are women and children. In pictures, this is the reality for people fleeing the crisis in Ukraine.

Get updates from our work in Ukraine as it develops

More from Ukraine

From the Ukrainian border

Sign up for our newsletter.

Get emails with stories from around the world.

You can change your preferences at any time. By subscribing, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Special Issues

- Editor's Choice

- Submission Site

- Author Guidelines

- Open Access

- About Journal of Refugee Studies

- Editorial Board

- Early-Career Researcher Prize

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Books for Review

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, challenging sociopolitical contexts, the corporatization of the humanitarian industry, humanitarian communication strategies, social media opportunities and challenges for humanitarian organizations, methodology, discussion and conclusion, acknowledgements, author contributions, disclosure statement, data availability, beyond victim and hero representations a comparative analysis of unhcr’s instagram communication strategies for the syrian and ukrainian crises.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

David Ongenaert, Claudia Soler, Beyond victim and hero representations? A comparative analysis of UNHCR’s Instagram communication strategies for the Syrian and Ukrainian crises, Journal of Refugee Studies , 2024;, feae035, https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feae035

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The Ukrainian crisis has received substantial Global Northern policy support and favourable news coverage, contrasting sharply with Global Southern crises. Nevertheless, refugee organizations can influence public perceptions through social media. This study comparatively analyses UNHCR’s Instagram communication strategies for the Ukrainian and Syrian crises (2022–2023). Applying a multimodal critical discourse analysis on UNHCR’s Instagram posts (N = 90), we discern interacting humanitarian and post-humanitarian appeals, involving inter- and intra-group hierarchies of deservingness, expanding research on humanitarian communication. While UNHCR mainly represents forcibly displaced Ukrainians as victims and focuses on ‘ideal victims’, it mostly portrays forcibly displaced Syrians as empowered individuals, likely due to context-specific differences and partially countering news and policy narratives. Both humanitarian representations often intersect with post-humanitarian strategies, facilitated by Instagram affordances. This study thus contributes to the literature on humanitarian communication with comparative crisis-specific and platform-specific insights and causes. Moreover, it nuances the often-assumed importance of post-humanitarian imageries on social media.

The Ukrainian-Russian war has led to one of the largest crises of modern times, involving 11.6 million forcibly displaced Ukrainians at the end of 2022 ( UNHCR 2023 ). Many European countries, including those with anti-migration sentiments, are promoting solidarity with Ukrainian refugees. This is illustrated by the European Union’s (EU) first activation of the Temporary Protection Directive since its adoption in 2001, which prioritizes prompt and efficient assistance rather than individual asylum application processing. This approach contrasts sharply with the EU’s much more restrictive policies towards refugees from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), including Syria ( Moallin et al. 2023 ). Similarly, Western news media often portray forcibly displaced Ukrainians more positively as contingent, legitimate, innocent and/or resilient victims, while those from the MENA as passive victims and/or threats, constructing hierarchies of deservingness. Various media have bluntly justified these double standards by arguing that Ukrainians resemble more their host populations: European, Christian, and white ( Zawadzka-Paluektau 2023 ).

In these challenging contexts, international refugee organizations often play important roles. They provide humanitarian assistance and protection ( Betts et al. 2012 ) but also increasingly attempt to inform and influence media, public, and political agendas through public communication (Green 2018). However, international refugee organizations face acute dilemmas about how to deal with and communicate the above-mentioned double standards on refugee protection and tensions with humanitarian priorities and principles (e.g. impartiality and neutrality) ( Moallin et al. 2023 ). This raises the question of whether and how they use different communication strategies for different crises. So far, various studies have analysed how international refugee organizations portray forcibly displaced people from the Global South and mostly identified ‘victim’ and ‘hero’ representations ( Ongenaert 2019 ; Veeramoothoo 2022 ). However, humanitarian representations of forcibly displaced people from the Global North, including Ukraine, have barely been explored.

Furthermore, the focus has mainly been on reports ( Veeramoothoo 2022 ), photo archives ( Bellander 2022 ), and press releases and news stories ( Ongenaert and Joye 2019 ; Ongenaert et al. 2023b ). However, refugee organizations’ social media strategies, including on Instagram, have hardly been investigated. Nevertheless, refugee organizations increasingly utilize social media to inform, sensitize, advocate, mobilize, and raise funding ( Carrasco-Polaino et al. 2018 ). These platforms provide new opportunities for broader visibility, interactivity, more nuanced representations, and challenging ingrained hierarchical societal structures ( Scott 2014 ). Hence, refugee organizations’ social media strategies can significantly influence public perceptions of migration. Especially as social media discourses may affect conventional media’s coverage priorities, which often follow social media trends ( Yang and Saffer 2018 ). Particularly Instagram has gained substantial popularity for social justice discourse, partially due to its rapid development and significance to aesthetic photos ( Carrasco-Polaino et al. 2018 ).

Acknowledging the above-mentioned trends, we apply a Multimodal Critical Discourse Analysis (MCDA) ( Machin and Mayr 2023 ) on the Instagram posts (N = 90) of the leading refugee organization United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) about the Syrian and Ukrainian crises in the key period between February 2022 and March 2023. This study investigates what are the main Instagram communication strategies used by UNHCR for the Ukrainian and Syrian crises? We examine whether and how UNHCR’s Instagram communication strategies differ from previously identified humanitarian narratives on traditional communication channels and differ for the Ukrainian and Syrian crises. Hence, we respond to the need for more comparative research on this subject ( Ongenaert et al. 2023b ).

This study reveals mixed results as UNHCR employs interacting humanitarian and post-humanitarian appeals, involving explicit and implicit inter- and intra-group hierarchies of deservingness and crisis-specific differences and commonalities, extending and nuancing earlier research. While UNHCR primarily represents forcibly displaced Ukrainians as victims and highlights ideal victims, it mostly portrays forcibly displaced Syrians as empowered individuals. These representations partially counter common news narratives and can likely be explained by context-specific differences (e.g. different crisis phases and geographical locations) and objectives. Further, both humanitarian appeals often interact with post-humanitarian appeals, which are facilitated by Instagram affordances. Overall, we argue that UNHCR’s Instagram communication strategies largely reproduce humanitarian and post-humanitarian strategies. Following challenging institutional and crisis-specific contexts and dominant social media logics, UNHCR barely utilizes the platform’s opportunities for more nuanced, contextualized representations. This study contributes to the literature on humanitarian communication by providing in-depth, comparative insights into the largely unexplored social media strategies of refugee organizations for both Global Southern and barely examined Global Northern crises. It provides comparative crisis-specific and platform-specific insights and potential underlying causes and demonstrates that mainly humanitarian imageries, frequently in interaction with post-humanitarian imageries, are used on Instagram, which nuances the often-assumed importance of the latter on social media. We first discuss the underlying challenging sociopolitical and corporatized contexts in which refugee organizations operate and then elucidate their communication strategies and social media challenges and opportunities.

Although providing protection and assistance is primarily the duty of states, several countries are increasingly reluctant to cooperate with refugee organizations, have tightened their asylum policies and rarely provide sufficient humanitarian funding ( Betts et al. 2012 ). These measures have made it increasingly challenging for refugee organizations to achieve their goals ( Walker and Maxwell 2009 ).

Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic, the worldwide recession, the climate crisis, and widespread negative public opinions on forcibly displaced people from the Global South have significantly complicated their operations. Popular populist movements attempt to criminalize and fuel public discontent with forced migration, often on social media ( Yang and Saffer 2018 ). Moreover, news media often portray forcibly displaced people as passive victims and/or threats ( Chouliaraki 2012a ) and usually limit their voice in the public debate, favouring politicians and governmental officials as the dominating news sources ( Franquet Dos Santos Silva et al. 2018 ). Further, the humanitarian competition for funding and criticisms of the limited transparency and accountability of humanitarian organizations have further challenged refugee organizations’ goals ( Vestergaard 2008 ). Given the growing role of both UN agencies and NGOs in addressing global challenges, there are rising expectations of transparency and accountability of their operations towards donors, taxpayers, and affected people. They should therefore promote accountability and transparency, relying on high-quality, culturally inclusive, learning-based management ( Clarke 2021 ).

Considering these challenges, refugee organizations must create successful communication strategies to sensitize, inform, build agendas, and fundraise ( Yang and Saffer 2018 ; Ongenaert and Joye 2019) . Refugee organizations are simultaneously adapting their communication practices to corporatization trends in the humanitarian industry.

Following trends of professionalization and commercialization, humanitarian organizations increasingly adopt branding practices, allowing them to communicate their values more explicitly and generate new types of legitimacy ( Vestergaard 2008 ). In short, non-profit branding concerns the deliberate, active management of both tangible and intangible perceptions to communicate consistent and coherent messages to stakeholders ( Hankinson and Rochester 2005 ). A positive non-profit brand image often increases fundraising ( Paço et al. 2014 ).

Similarly, celebrity humanitarianism has been promoted within humanitarian organizations as it enables larger visibility, brand awareness, and fundraising ( Mitchell 2016 ). Importantly, the engagement of celebrities in humanitarianism is not new but celebrity humanitarianism transcends mere advocacy through branding. This results in mutually beneficial alliances between humanitarian organizations and celebrities. While celebrities’ reputations as humanitarians are legitimized, humanitarian brands obtain increased exposure ( Chouliaraki 2012b ).

The integration of these corporate practices, interests, and values indicates the corporatization of humanitarianism and has blurred public–private sector divisions ( Vestergaard 2008 ). Critics argue that by adopting a marketing logic, humanitarian organizations prioritize in their communication consumers’ interests, identities, and values over their cause and thus support existing values rather than social change. Therefore, humanitarian branding is sometimes considered to contradict the principles of charity, voluntarism, democracy, and grassroots activism (ibid.). Given the corporatization of humanitarianism, the types of humanitarian communication strategies have changed, especially on digital platforms.

We discuss the main communication strategies applied by humanitarian organizations, including refugee organizations, through Scott’s (2014) typology. Essentially, humanitarian organizations mainly use various humanitarian discourses, including shock effect appeals and deliberate positivity (infra), which morally justify solidarity on human vulnerability by relying on a universalist common, shared humanity, across political and/or cultural differences. However, Chouliaraki (2012a ) observed gradual, non-linear shifts from these humanitarian discourses to post-humanitarian discourses. These respond to ‘existing concerns about the moral deficit of ‘common humanity’ as a justification for solidarity, by moving away from the refugee and towards the self as the primary object of our cognition and emotion’ (ibid.: 13). These rely on a morality of contingency, involving the ‘Self’ as a moral justification for solidarity with distant suffers, particularly on digital media.

Shock effect appeals

Humanitarian organizations traditionally use shock effect appeals, which address the suffering of affected people. They usually portray people as innocent, powerless people who deserve compassion and help ( Scott 2014 ) to generate strong emotions such as pity and guilt among audiences and eventually media, public, and political attention and support ( Chouliaraki 2010 ; Ongenaert et al. 2023a ). There is often a focus on women and children, who are considered ‘ideal victims’ ( Höijer 2004 ; Jhoti and Allen 2024 ). Through their apparent innocence and vulnerability, they are usually more effective in generating pity and eventually audience engagement and fundraising than other population groups ( Moeller 1999 ; Johnson 2011 ). However, as the circumstances of others or the context and nature of the larger cause are not considered, this focus can diminish public engagement in humanitarian causes and lead to public perceptions that some victims deserve more compassion and assistance than others, creating hierarchies of deservingness among distant suffers ( Scott 2014 ).

Nevertheless, shock effect appeals are often the most effective in generating awareness and financial support, especially for humanitarian emergencies ( Scott 2014 ). International refugee organizations have therefore widely adopted this communication strategy. Forcibly displaced people’s humanitarian images have generally changed from heroic, politicized individuals in the Cold War period to anonymous, voiceless, depoliticized, dehistoricized, decontextualized, universalized, racialized, and/or victimized masses from the ‘Global South’ ( Ongenaert 2019 ; Bellander 2022 ; Ongenaert et al. 2023b ). These discursive transformations interact with the aforementioned policy shifts and serve to mobilize public support and manage forcibly displaced people’s perceived threats. These representations contribute to frequently oversimplified crisis and emergency discourses which, driven by financial and media interests, emphasize the severity of humanitarian situations ( Johnson 2011 ).

However, the repeated use of these appeals can make audiences desensitized to images of suffering, also known as ‘compassion fatigue’ ( Moeller 1999 ; Chouliaraki 2010 ). This entails both practical and ethical risks. It can create a sense of powerlessness and lead to less involvement. Since these appeals attempt to arouse guilt, this can generate frustration and resistance to campaigns. Rather than promoting social action for humanitarian causes, these risks could undermine it ( Chouliaraki 2010 ). Moreover, humanitarian organizations could inadvertently reinforce white saviour stereotypes by implying that Northern donors are key to societal issues in the Global South. Furthermore, these appeals address suffering victims, benefit from them, and often neglect or oversimplify the complex contexts and root causes of suffering ( Scott 2014 ).

Deliberate positivity

In pursuing more representative and dignified communication strategies, humanitarian organizations began to adopt deliberate positivity, favouring the agency and dignity of affected people ( Chouliaraki 2010 ). It seeks to induce feelings of gratitude and empathy through images that subtly convey affected people’s gratitude to donors ( Chouliaraki 2010 ; Scott 2014 ). Refugee organizations often represent forcibly displaced people as ‘heroes’; as empowered, optimistic, resilient, and humane individuals, highlighting their voices, emotions, and names ( Rodriguez 2016 ; Ongenaert et al. 2023b ). They frequently represent forcibly displaced people as entrepreneurs or talented people (Turner 2020; Ongenaert et al. 2023b ). This positive imagery aims to engage audiences through identification and relatedness and to demonstrate the relevance of donating, often to eventually encourage (further) donating ( Ongenaert et al. 2023a ).

However, deliberate positivity often highlights talented, prosperous and/or engaging individuals and fails to address broader systemic issues ( Chouliaraki 2010 ; Ongenaert et al. 2023b ). It may also inadvertently create a dependency on external assistance. Given that donations are promoted to facilitate positive change in the Global South, this may further strengthen the dependence on existing unequal North-South power relations, rather than promoting self-reliance and empowerment ( Scott 2014 ). Finally, highlighting positive progress can appear as if active support is no longer necessary ( Chouliaraki 2010 ; Scott 2014 ).

Post-humanitarian appeals

In recent years, humanitarian organizations increasingly employ post-humanitarian appeals. Post-humanitarian communication uses creative text and visual techniques, emphasizing discourses centred on Western audiences rather than distant suffers, who are often completely absent ( Scott 2014 ). Relying on celebrity humanitarianism and online donation actions, this strategy can realize brand differentiation, attract niche customers or influence global policy ( Scott 2014 ; Ongenaert et al. 2023b ). Hence, refugee organizations represent forcibly displaced people in creative, innovative, and aesthetic ways and engage in celebrity humanitarianism, particularly on digital and social media ( Chouliaraki 2012a ; Mitchell 2016 ). Celebrity humanitarianism can increase the visibility of humanitarian issues, reach and engage wider, previously unconcerned audiences, and foster emotions of belonging and connection ( Mitchell 2016 ).

However, celebrity humanitarianism will mainly generate public discussion about the celebrity rather than educating the public about systemic change ( Chouliaraki 2012b ). Celebrity humanitarianism and branding also create moral conflicts by staging human misery in the fields of entertainment and consumerism ( Vestergaard 2008 ). Post-humanitarian appeals have been criticized for depriving affected people of their voice, reproducing North-South power imbalances ( Scott 2014 ), and relying primarily on own moral judgements to engage with suffering people ( Chouliaraki 2010 ).

Audiences and social media in a humanitarian context

We consider audiences in the digital networked age as relatively active. They engage, interpret, negotiate, and critique media texts. Whereas once people used temporarily media for specific purposes, they are currently continually and unavoidably audiences, as all aspects of social reality are mediated or mediatized ( Hepp 2013 ). However, there are simultaneously substantial digital divides ( Scheerder et al. 2019 ). Moreover, audiences are diverse and interpret polysemic news differently. For instance, the frequency and the tone of news on immigration, contextual factors ( Boomgaarden and Vliegenthart 2009 ) and citizens’ media consumption, media trust, and coverage evaluation strongly shape public opinions on immigration ( De Coninck et al. 2018 ). Audiences’ responses to mediated distant suffering are thus diverse and mediated by media texts and their sociodemographic positions, biographical scripts and broader national and cultural contexts, and discursive frameworks ( Kyriakidou 2022 ).

To reach, inform, sensitize, and engage audiences, social media has become crucial for humanitarian organizations, including refugee organizations ( Kim 2022 ). They provide potent, affordable platforms for showcasing organizations’ efforts to large audiences ( Carrasco-Polaino et al. 2018 ). By enabling two-way communication and immersion in virtual worlds, social media might help reduce the gap between audiences and affected people. Social media allows for more nuanced, varied, and comprehensive representations of the Global South and provide simpler options for action (e.g. exchanging information, signing online petitions), increasing participation levels ( Scott 2014 ; Rosa and Soto-Vásquez 2022 ). Hence, many NGOs utilize popular social networks ( Carrasco-Polaino et al. 2018 ). However, there are also risks. Aesthetic visual representations of humanitarian issues could become more relevant than the issues themselves and the demands for action ( Chouliaraki 2010 ). Furthermore, editing images to meet public and aesthetic ideals can create distance between the represented and the audience and distort everyday life realities ( Woods and Shee 2021 ). Moreover, the simplicity of participation may give the appearance of commitment but can foster short-term, superficial engagements in humanitarian issues ( Scott 2014 ).

Instagram affordances and aesthetics

Particularly Instagram has gained popularity for social justice communication ( Carrasco-Polaino et al. 2018 ). An important advantage is the convincing ability of visuals. Images are more memorable and understandable than texts, attract more attention ( Knobloch et al. 2003 ) and are perceived as more reliable because they are mostly seen as an accurate representation of reality ( Carrasco-Polaino et al. 2018 ). However, to achieve stakeholder engagement on social media, refugee organizations’ posts should also reflect, besides stakeholder interests and principles, social media logics ( Yang and Saffer 2018 ). In short, social media logics refer to the norms, strategies, mechanisms, and economies through which social media platforms process information, news, and communication and channel social traffic ( Van Dijck and Poell 2013 ). ‘[E]ach social media platform comes to have its own unique combination of styles, grammars, and logics’, or ‘platform vernacular’ ( Gibbs et al. 2015 : 257). These genres of communication result from the affordances of social media platforms and users’ appropriations, mediated practices, and communicative habits. These vernaculars evolve over time and through design, appropriation, and use (ibid.).

Organizations need to design their posts attractively as aesthetics are important on Instagram. Instagram aesthetics can be situated at the levels of Instagram’s visual and textual content, practices and users. It includes visual aesthetics, including genres and tropes of content and visual aesthetic normalization, users’ practices and norms, and audiences and their motivations for using Instagram ( Leaver et al. 2020 ). Central to Instagram’s vernacular and aesthetics are the affordances for photo-sharing, tagging images, creating captions and texts, applying photographic filters, and mobile phone usage as well as their interplays. These enable Instagram to be embedded in everyday practices and function as a space to present one’s life and get informed and learn about others’, including both mundane and extraordinary experiences ( Gibbs et al. 2015 ; Leaver et al. 2020 ). In that regard, ‘Instagramism’ refers to the aesthetic strategies employed in the construction of aesthetic identities in designed Instagram images ( Manovich 2020 ). It provides an own worldview and visual language (e.g. frame, composition, space, themes, photo sequence). An emergent activist tactic that relies on Instagram’s logic is slideshow activism ( Dumitrica and Hockin-Boyers 2022 ). That is a series of slides (images) with short words and graphic components that highlight a particular topic and provide new ways to discuss and translate complex political issues into comprehensible and easily disseminated images. Instagram is thus for humanitarian organizations a tool for modern artivism, or a fusion of art and activism ( Carrasco-Polaino et al. 2018 ).

The popularity and importance of Instagram are also largely related to the ‘aesthetic society’ we live in, where aesthetically refined consumer goods, services, and experiences are central to economic and social functioning ( Manovich 2020 ). Sophisticated aesthetics are the central characteristic of goods and services, and aesthetically oriented professionals and individuals are valued. Similarly, we live in an increasingly ‘visual age’ ( Bleiker 2018 ). The production and distribution of images have been democratized and they have unprecedented, potentially global circulation and reach. Visual media have become the main semiotic channels for shaping, depicting, interpreting and comprehending the world, including global political topics such as forced migration ( Bleiker 2018 ; Woods and Shee 2021 ). Visual representations can have powerful political and emotional effects, including through their illusion of authenticity, aesthetic choices, politics of visibility and invisibility and domination and resistance, and their need for interpretation: ‘they delineate what we, as collectives, see and what we don’t and thus, by extension, how politics is perceived, sensed, framed, articulated, carried out, and legitimized’ ( Bleiker 2018 : 4). Images have fundamentally altered citizens’ lives and interactions. They often evoke and generate emotions, shaping how audiences worldwide perceive, understand, and respond to particular events, including humanitarian crises ( Bleiker 2018 ). By depicting individuals and personal stories, they provide viewers with identification opportunities and make distant, complex political topics accessible. Through close-up portraits of victims, compassion can be evoked in viewers, whereas group pictures rather create emotional distance. However, this process can be affected by compassion fatigue ( Moeller 1999 ), states of denial ( Cohen 2001 ), media fatigue ( Campbell 2014 ), or other societal factors, requiring humanitarian organizations to use considerate social media strategies.

Social media strategies by humanitarian organizations

Rodriguez (2016) found that some asylum-specific NGOs use Facebook and Twitter to share the individualized experiences of forcibly displaced people to elicit compassion and sympathy, reflecting deliberate positivity. Nevertheless, these organizations primarily use social media to disseminate foreign and human rights policy information, which can be considered an attempt to educate the public about systemic change. Carrasco-Polaino et al. (2018) identified two predominant communication strategies among international NGOs on Instagram. Some nonprofits used empowering images of potential project participants, mirroring deliberate positivity. However, to raise awareness about the need for assistance, NGOs portray potential solemn- or concerned-looking project participants ( Carrasco-Polaino et al. 2018 ), indicating shock effect appeals. Although social media provides opportunities to highlight societal complexities and are often assumed to foster post-humanitarian imageries (supra), mostly the dominant humanitarian representation strategies thus (re)appear.

Although valuable, these studies analyse NGOs’ Facebook and Twitter communication or examine the use of Instagram by NGOs in general. To our knowledge, the Instagram communication strategies of refugee organizations are largely unexplored but can significantly influence public opinions ( Chouliaraki 2012b ). Having connected commonly separated communication strategies and production, reception and societal contexts, we now extend and refine the literature by comparatively analysing UNHCR’s Instagram communication strategies for two crises.

Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) investigates the influence of discursive features of power dynamics and inequalities ( Fairclough 2013 ). By analysing word and grammar choices, CDA examines the discursive construction and meaning-making of reality ( Hansen and Machin 2019 ; Machin and Mayr 2023 ). However, as images can also reflect ideologies and power ( Machin and Mayr 2023 ), there has been a growing interest in visual methods. MCDA has therefore been used to critically analyse discourses within both textual and (audio)visual genres (e.g. videos, images). This study analyses discursive strategies in both Instagram images and captions and their interplays, which are central to Instagram’s vernacular and logic (supra). Therefore, we applied MCDA as it scrutinizes how visual and textual elements interact and co-create meaning ( Hansen and Machin 2019 ; Machin and Mayr 2023 ). Supported by Office software, we applied a comparative-synchronous approach ( Carvalho 2008 ) to consider crisis-related differences.

We examined UNHCR, as it is the key international refugee organization ( Clark-Kazak 2009 ), currently counts 1.9 million followers on Instagram ( UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency n.d. ), and is extensively engaged in and communicates about the large-scale Ukrainian and Syrian crises. We analysed UNHCR’s Instagram posts as we live in an increasingly aesthetic and visual society (supra) and social media plays crucial roles in influencing the discourses about forcibly displaced people. Their Instagram representations particularly need further investigation ( Rosa and Soto-Vásquez 2022 ). Further, we selected the Syrian and Ukrainian crises for various reasons. First, international refugee organizations face acute dilemmas regarding how to communicate the above-mentioned double standards on refugee protection and tensions with humanitarian priorities and principles (supra). This raises the question of whether and how UNHCR employs different communication strategies for both crises. This is especially relevant given that humanitarian representations of forcibly displaced people from the Global North, including Ukraine, have barely been explored. Second, both crises are internationally important, large-scale, and protracted but were in a different phase in 2022. The Russian-Ukrainian war began in 2014 and settled in 2015 into a violent but static conflict. However, the Russian invasion in 2022 created the fastest displacement crisis since the Second World War ( UNHCR 2023 ). Since then, the Ukrainian crisis has dominated public, media, and political agendas and discussions ( Newman et al. 2023 ). The Syrian conflict, however, started in 2011 and became in 2013 the largest displacement crisis worldwide. However, it has declined sharply and disappeared from media attention in recent years, even though there is a massive, growing humanitarian crisis due to ongoing war, economic collapse, and climate change ( The New Humanitarian 2024 ). The Syrian crisis remains the largest with 13.8 forcibly displaced people at the end of 2022 ( UNHCR 2023 ). We thus fully acknowledge the potential influence of the different and complementary nature of both crises (e.g. crisis phase, scale, context, implications, mediatization) on UNHCR’s communication content. By focusing on the same organization, platform, and year, this comparative approach potentially allows us to investigate whether and how these crisis-specific societal factors influence humanitarian communication, which has hardly been explored.

Further, we analysed the key year 2022, for theoretical, practical, and pragmatic reasons. First, we decided to start our research period on 1 February 2022. As the Russian invasion started on 24 February 2022, the selected research period allows us to analyse UNHCR’s Instagram posts for the Ukrainian and Syrian crises both before and during this escalation of the protracted Russian-Ukrainian conflict. Second, a preliminary examination of UNHCR’s Instagram posts revealed a huge amount of data. Considering the time-consuming nature of our in-depth, comparative, multimodal approach and to ensure a feasible and uniform analysis, equal amounts of data were collected for both the Syrian (N = 45) and Ukrainian crises (N = 45), resulting in a total of 90 analysed posts. Only posts which explicitly refer, textually and/or visually, to these crises were selected. Although the data set is relatively limited and we thus will be cautious in making generalizations, it constitutes a reasonable record of UNHCR’s Instagram posts on both crises, including various topics, times, and places. Considering UNHCR’s different amount of Instagram posts for both crises in 2022, the sample includes material published online between 1 February 2022 and respectively 8 April 2022 (Ukraine) and 1 March 2023 (Syria). As the research periods do not fully coincide, we are cautious in making contextual comparisons and consider the influence of different contexts on the results. However, we do not think this substantially affected the main results. The subsamples of the Instagram posts about the Ukrainian and Syrian crises constitute relatively temporally proximate, limited, and logical entities, which also enable us to make relevant statements about contextual dimensions.

The CDA model of Fairclough (2013) , used here, addresses three dimensions: text (i.e. linguistic and visual features of a media text); discursive practices (i.e. production, distribution, and consumption of a media text); and social practice (i.e. broader societal context of the text and discursive practices). (M)CDA is, however, a critical, interpretative state of mind, rather than an explicit, systematic, reproducible research method ( Reisigl and Wodak 2016 ). Hence, to increase the study’s reliability, we reflexively discuss our research decisions and used various discursive criteria, informed by multiple key works ( Hansen and Machin 2019 ; Machin and Mayr 2023 ) and the literature review. The discursive criteria mainly address the textual and/or visual representation of social actors, such as personalization, impersonalization, individualization, collectivization, specification, genericization, nomination, functionalization, pronouns, distance, and angle. Nevertheless, given the limited and fragmented research on the subject, this study approaches the data also from an open, explorative, inductive perspective. We respond to common criticisms that (M)CDA lacks comparative analyses, spends little attention on (non-journalistic) social actors’ discursive strategies, and is too text-focused, neglecting (audio)visual content ( Carvalho 2008 ; Hansen and Machin 2019 ). While not distinguishing between Fairclough’s (2013) dimensions of text, discursive practices, and social practices, the latter two are integrated into the discussion of textual strategies to contextualize the analysis. We structure the results according to Scott’s (2014) typology and contextualize them via textual and audience research on humanitarian discourses.

Shock effect appeals: victimized masses and ideal victims

The study shows that UNHCR primarily uses shock effect appeals. It represents forcibly displaced Ukrainians and, to lesser extents, Syrians as victimized, voiceless masses, and highlights ideal victims.

Our analysis revealed that UNHCR mostly textually represents forcibly displaced Ukrainians and Syrians as anonymous masses in need of assistance through shock effect appeals in its Instagram posts, corresponding with previous research ( Ongenaert and Joye 2019 ; Bellander 2022 ). First, UNHCR often impersonalizes and silences them by not mentioning any personal information (e.g. perspectives, experiences, feelings), which dehumanizes and makes the presented people voiceless ( Machin and Mayr 2023 ). Relatedly, UNHCR often generically presents forcibly displaced Ukrainians (e.g. ‘people in need’, ‘people fleeing’) and, to a lesser extent, Syrians (e.g. ‘a Syrian refugee’, ‘Syrian girls’), which can homogenize their personal experiences and feelings ( Machin and Mayr 2023 ; Ongenaert et al. 2023b ). UNHCR frequently reduces their identities to nationality and/or gender and simplifies their sociopolitical and economic contexts. Relatedly, UNHCR often represents them as collectives (e.g. ‘Syrian refugee children’, ‘3 million refugees’), devoid of any individuality, which can also have dehumanizing effects ( Machin and Mayr 2023 ; Ongenaert et al. 2023b ). These findings confirm previous criticisms of shock effect appeals denying the dignity of affected people ( Scott 2014 ).

In images, the distance and angles through which people are displayed connote varying relations with the audience, which can affect audience engagement and relatedness ( Hansen and Machin 2019 ; Machin and Mayr 2023 ). We found that UNHCR often portrayed forcibly displaced Ukrainians and Syrians through eye-level views, which often imply equality, ordinariness, and closeness and facilitate sympathy ( Figures 1 , 5 , and 8 ) ( Machin and Mayr 2023 ). UNHCR also occasionally uses bird’s-eye views, which usually connote low(er) statuses, physically weak(er) positions, limited agency and/or empowerment ( Figures 2 and 3 ). This reinforces the textual victim narratives and can potentially arouse feelings of pity ( Clark-Kazak 2009 ; Ongenaert and Joye 2019 ). Moreover, UNHCR often uses medium shots ( Figures 1 , 2 , and 5 ), which frequently imply intimacy, closeness, approachability, and/or genuineness. Such imagery can facilitate empathy ( Machin and Mayr 2023 ). In sum, UNHCR often seeks to visually reinforce the victim narratives, which can evoke emotions of pity and guilt.

Screenshot of UNHCR’s official Instagram account. 15 April 2022. © UNHCR/Lilly Carlisle.

Screenshot of UNHCR’s official Instagram account. 9 March 2022. © UNHCR/Zsolt Balla.

Screenshot of UNHCR’s official Instagram account. 7 March 2022. © UNHCR/Chris Melzer.

Our analysis shows that UNHCR visually mainly represents helpless and anonymous Ukrainian and Syrian women and children ( Figures 1 and 2 ), corresponding with previous findings on ideal victims ( Höijer 2004 ; Jhoti and Allen 2024 ). Hence, UNHCR can potentially more easily generate strong emotions of pity and guilt and subsequently awareness and donations ( Höijer 2004 ; Scott 2014 ). Contrasting with Syrian women and children (infra), UNHCR often portrays forcibly displaced Ukrainians in relatively generic groups, which may diminish their individuality ( Machin and Mayr 2023 ). Nevertheless, UNHCR mostly foregrounds women and children in these groups ( Figure 3 ), which might elicit sentiments of pity ( Höijer 2004 ). Importantly, reflecting UNHCR’s communication focus, most Ukrainian refugees are women and children ( UNHCR 2023 ). Although there are also many (less visible) internally displaced Ukrainians, this probably partially explains UNHCR’s visual sociodemographic focus. The Syrian crisis, however, also involves many children but a more balanced gender division of refugees (ibid.). This indicates the potentially deliberate nature of UNHCR’s focus on ideal Syrian victims (i.e. helpless women and children).

Extending previous research, we found that UNHCR frequently represents forcibly displaced Ukrainians as ‘families’ ( Figures 2 and 3 ). This can create more nuanced, humanized portrayals ( Machin and Mayr 2023 ), and might also mobilize support. As ‘families’ are often associated with affection, warmth, or safety—and thus can also be considered as ideal victims, it may facilitate relatedness and compassion. However, forcibly displaced Syrians are labelled more generically as ‘refugee families’. Due to the constant functionalizing reference to legal status, this term may sound less identifiable and humanizing than ‘families’ (ibid.). By overly highlighting specific sociodemographic groups (i.e. women, children, families) or using different terminologies, UNHCR might indirectly contribute to hierarchies of deservingness within and between population groups. This might influence public perceptions and policy measures and emphasizes the need to develop (more) diverse, balanced, and inclusive representations ( Ongenaert et al. 2023b ).

Overall, shock effect appeals can be effective in raising awareness and donations ( Scott 2014 ). However, UNHCR’s repeated use of these strategies could in the long term potentially generate compassion fatigue ( Moeller 1999 ; Chouliaraki 2010 ). Furthermore, none of UNHCR’s Instagram posts address the underlying economic and political contexts of the crises, nor provide recommendations for structural change, confirming earlier criticisms of shock effect appeals and social media posts oversimplifying complex situations ( Scott 2014 ; Ongenaert and Joye forthcoming ). UNHCR’s Instagram posts only limitedly contribute to a more comprehensive public understanding of these international conflicts and affected people’s complex experiences.

Deliberate positivity: empowered and talented individuals

The analysis shows that UNHCR also frequently uses deliberate positivity by portraying forcibly displaced Syrians and, to far lesser extents, Ukrainians as ‘heroes’; as talented, empowered, resilient, and unique individuals, likely to engage audiences ( Ongenaert et al. 2023b ). First, we found that UNHCR substantially individualizes, nominates, personalizes, and specifies them as individuals with unique identities and often resilient experiences by including their names, stories and/or Instagram tags in the captions ( Figures 4 and 5 ). Instagram’s affordances thus allow us to further explore forcibly displaced people’s experiences, stories, and perspectives. UNHCR also often visually individualizes forcibly displaced Syrians, as the agents of stories and emotions ( Machin and Mayr 2023 ). It mainly uses medium shots, often to showcase their activities and cheerful faces and likely to create intimacy, closeness, approachability, genuineness, and empathy ( Figure 5 , Carrasco-Polaino et al. 2018 ; Machin and Mayr 2023 ). UNHCR mostly portrayed forcibly displaced Syrians through eye-level views, which often imply equality, ordinariness and/or closeness and can facilitate sympathy and audience engagement ( Figure 5 ). It sometimes uses frog’s-eye views, which often portray the represented people as empowered individuals ( Machin and Mayr 2023 ), corresponding with deliberate positivity ( Rodriguez 2016 ). These representations can be interpreted as more humanized but not necessarily more nuanced ( Scott 2014 ).

Screenshot of UNHCR’s official Instagram account. 18 November 2022. © UNHCR/Lam Duc Hien.

Screenshot of UNHCR’s official Instagram account. 18 November 2022. © UNHCR/Jack Nolos.

UNHCR often functionalizes forcibly displaced Syrians by representing them based on what they do, which can confer legitimacy and authority ( Machin and Mayr 2023 ). However, UNHCR frequently reduces them to their legal status (e.g. ‘refugee’), which can have dehumanizing effects. UNHCR often also mentions highly socially valued functions (e.g. ‘UNHCR Goodwill ambassador’, ‘Olympian’, ‘author’, ‘engineer’), which portrays individuals as respectable, ‘good’ members of society (ibid.). UNHCR thus mainly highlights talented, empowered and/or unique forcibly displaced Syrians ( Ongenaert et al. 2023b ). These discursive transitions from ‘refugees’ to talented, active citizens illustrate positive changes in their lives. UNHCR arguably aims to highlight their empowerment, agency, talents, and resilience and the positive impact of donor-funded humanitarian assistance ( Scott 2014 ). Likewise, the analysis revealed that UNHCR sometimes combines different distance perspectives within the same post. Forcibly displaced Syrians are sometimes depicted walking in rural areas from long shots to working in professional environments from medium shots ( Figures 4 and 5 ). Hence, UNHCR arguably visually showcases the favourable long-term changes in forcibly displaced Syrians’ lives, reinforcing textual discourses. While UNHCR should of course highlight forcibly displaced people’s development, empowerment, and achievements, it should not neglect, nor deprive the dignity of people without highly socially valued functions or characteristics.

Overall, by portraying individuals in empowered and resilient ways, UNHCR might aim to prove the impact of donations ( Scott 2014 ) and ultimately foment humanitarian engagement ( Chouliaraki 2010 ). Nevertheless, donations from the Global North are often presented as the only way to facilitate social change in the Global South (infra). Deliberate positivity consequently reinforces existing North-South symmetries, including by implicitly fostering the notions of the grateful recipient and the benevolent donor ( Scott 2014 ). Therefore, UNHCR should work to change this dependency narrative, for instance, by educating its audiences on advocacy for long-term, structural policy changes. Moreover, the repetitive illustration of positive change has been criticized for promoting similar inaction outcomes as in shock effect appeals ( Scott 2014 ). Deliberate positivity might convey that humanitarian engagement is no longer necessary ( Chouliaraki 2010 ).

In sum, we found that UNHCR represents forcibly displaced Ukrainians more as anonymous, victimized groups (shock effect appeals), while forcibly displaced Syrians rather as empowered individuals (deliberate positivity). This can likely be partially explained by the phase of the crisis, the geographical location of the represented people, and UNHCR’s related objectives. The Ukrainian crisis grew strongly during the research period, with many people fleeing to neighbouring countries. UNHCR therefore likely portrayed large, victimized groups on the move to emphasize the size and urgency of the crisis ( Ongenaert et al. 2023b ). The Syrian crisis, however, has been going on since 2011 and many forcibly displaced Syrians have integrated into the region and Europe. UNHCR therefore likely aims to emphasize ‘success stories’ to improve public perceptions in host countries. However, at the same time, Syria has a very difficult security, humanitarian, and economic situation (supra). Nevertheless, UNHCR only occasionally depicts internally displaced Syrians. Previous production research showed that refugee organizations communicate little about and from Syria due to difficult political and security situations ( Ongenaert et al. 2023a ). This likely explains why UNHCR portrays Syrians more as empowered individuals than as victimized groups, especially as various studies focusing on the ‘peak years’ of the Syrian crisis found opposite results ( Ongenaert and Joye 2019 ; Ongenaert et al. 2023b ).

Post-humanitarian appeals: branding, self-centred solidarity, and celebrity humanitarianism

We found that UNHCR frequently combines shock effect appeals and, to a lesser extent, deliberate positivity with post-humanitarian appeals, which are facilitated by Instagram affordances and reflect the marketization of the humanitarian industry ( Chouliaraki 2012a ; Scott 2014 ; Bellander 2022 ). Whereas shock effect appeals are often paired with post-humanitarian branding strategies and self-centred solidarity discourses, deliberate positivity is sometimes connected with celebrity humanitarianism.

The analysis shows that UNHCR constructs its brand, generates visibility, and positively highlights its partners through various branding strategies. First, UNHCR accentuates governmental and own actions and achievements in assisting forcibly displaced people. For instance: ‘We are grateful to the Moldovan officials and people who are helping these refugees’ ( Figure 6 ) and ‘We’re working around the clock to help those in need’ (UNHCR 22 February 2023). Likewise, UNHCR’s images of the Ukrainian crisis sometimes include visual elements related to assisting states, including flags ( Figure 6 ), amenities, or donations, to emphasize their humanitarian involvement. Similarly, UNHCR’s images of the Syrian crisis often include its officials and/or logo, as a separate symbol and/or on relief items and clothing ( Figure 7 ), to highlight its humanitarian assistance. UNHCR thus often prioritizes post-humanitarian self-focused discourses rather than enhancing forcibly displaced people’s voices and agency ( Scott 2014 ). It builds its brand and anticipates common criticisms of limited accountability and transparency in the humanitarian sector ( Vestergaard 2008 ).

Screenshot of UNHCR’s official Instagram account. 5 March 2022. © UNHCR/Marin Bogonovschi.

Screenshot of UNHCR’s official Instagram account. 16 March 2022. © UNHCR/Emrah Gürel.

UNHCR frequently prioritizes consumer interests and values through self-centred solidarity discourses over the urgency of the humanitarian cause ( Vestergaard 2008 ). UNHCR occasionally directly addresses its audience through pronouns like ‘you’ to evoke reflexivity and emotion ( Ongenaert and Joye 2019 ; Ongenaert et al. 2023b ): ‘What would you take if you had to flee war?’ (UNHCR 19 March 2022). Likewise, UNHCR often calls for donations or other assistance via references like ‘Please donate via the link in bio’ and ‘You can help us help those in need of urgent support’ (UNHCR 25 March 2022). While UNHCR likely aims to foster audience engagement, this arguably also confirms the criticisms of post-humanitarian appeals fostering limited, emotion- and self-centred notions of solidarity to engage with humanitarian causes ( Vestergaard 2008 ; Chouliaraki 2010 ). It could promote more altruistic, political, and human-rights-oriented notions of solidarity.