Major Life Events that Affect Development

Life events affecting development can be broadly classified into predictable and unpredictable events. Predictable events occur in a sequence and at relatively specific times in the lifespan, while unpredictable events don’t follow a set timeline.

Predictable life events include going to school, puberty, getting a job, retirement, and death. These events are typically anticipated and prepared for, although they still can impact an individual’s development significantly.

Unpredictable life events are those which aren’t expected or planned. These can include accidents, natural disasters, loss of loved ones or diagnosis of serious health conditions. These events can have a major impact on a person’s physical, emotional, and cognitive development.

Major life events can trigger significant changes in a person’s life, influencing their physical health, emotional well-being, relationships, lifestyle, self-esteem and views on life.

In terms of physical impact, major life events can result in changes in growth, level of fatigue, immune system function and susceptibility to disease. For example, during periods of chronic stress, the immune system’s ability to fight off antigens is reduced, making individuals more susceptible to infections.

Major life events can also influence emotional development. For instance, the loss of a loved one may cause a person to experience feelings of sadness, anger, or confusion. This can impact their emotional well-being, potentially leading to conditions such as depression or anxiety.

In terms of cognitive development, major life events may force an individual to reassess their values, beliefs, and assumptions. This could result in personal growth and increased resilience.

Additionally, certain life events can have a major impact on social development. For example, marriage, having a child or divorce could significantly affect an individual’s social network and relationships with others.

Major life events can also change the way a person perceives themselves and their self-esteem. Achieving certain life milestones (like graduating from university or getting a promotion at work) can boost self-esteem, while negative events (like job loss or illness) could lead to a decrease in self-esteem.

The overall impact of major life events on development may vary depending on an individual’s genetic makeup, socioeconomic conditions, coping strategies, and the support network available to them during these times. That’s why it’s crucial to understand that responses to life events can be very individual and wide-ranging.

- International

- Schools directory

- Resources Jobs Schools directory News Search

![health and social care life stages coursework R025 [LO1 complete] Understanding life stages - Cambridge Nationals L1/2](https://d1e4pidl3fu268.cloudfront.net/92f26fe9-58c2-4524-a8ed-42dc49e7a01f/displaypict.crop_633x475_21,0.preview.jpg)

R025 [LO1 complete] Understanding life stages - Cambridge Nationals L1/2

Subject: Vocational studies

Age range: 14-16

Resource type: Unit of work

Last updated

15 March 2021

- Share through email

- Share through twitter

- Share through linkedin

- Share through facebook

- Share through pinterest

Resources include outstanding lessons for complete LO1 for R025 within the OCR cambridge nationals health and social care qualification.

Lessons preparing learners for coursework on LO1. All resources for the lessons are included.

Structure includes recap questions at the start, main learning, and a reflection on the learning. Differentiation is included throughout. Knowledge organiser included.

Feedback appreciated! :)

Tes paid licence How can I reuse this?

Your rating is required to reflect your happiness.

It's good to leave some feedback.

Something went wrong, please try again later.

This resource hasn't been reviewed yet

To ensure quality for our reviews, only customers who have purchased this resource can review it

Report this resource to let us know if it violates our terms and conditions. Our customer service team will review your report and will be in touch.

Not quite what you were looking for? Search by keyword to find the right resource:

Advertisement

Maslow and Mental Health Recovery: A Comparative Study of Homeless Programs for Adults with Serious Mental Illness

- Original Article

- Published: 12 February 2014

- Volume 42 , pages 220–228, ( 2015 )

Cite this article

- Benjamin F. Henwood 1 ,

- Katie-Sue Derejko 2 ,

- Julie Couture 1 &

- Deborah K. Padgett 2

12k Accesses

65 Citations

33 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This mixed-methods study uses Maslow’s hierarchy as a theoretical lens to investigate the experiences of 63 newly enrolled clients of housing first and traditional programs for adults with serious mental illness who have experienced homelessness. Quantitative findings suggests that identifying self-actualization goals is associated with not having one’s basic needs met rather than from the fulfillment of basic needs. Qualitative findings suggest a more complex relationship between basic needs, goal setting, and the meaning of self-actualization. Transforming mental health care into a recovery-oriented system will require further consideration of person-centered care planning as well as the impact of limited resources especially for those living in poverty.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

A Mixed-Methods Study of the Recovery Concept, “A Meaningful Day,” in Community Mental Health Services for Individuals with Serious Mental Illnesses

Understanding the ups and downs of living well: the voices of people experiencing early mental health recovery.

Mental Health Treatment Planning: A Dis/Empowering Process

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis . Los Angeles: Sage.

Google Scholar

Clarke, S., Oades, L. G., & Crowe, T. P. (2012). Recovery in mental health: A movement towards well-being and meaning in contrast to an avoidance of symptoms. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 35 , 297–304.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Collins, S. E., Malone, D. K., & Clifasefi, S. L. (2013). Housing retention in single-site housing first for chronically homeless individuals with severe alcohol problems. American Journal of Public Health, 103 (S2), S269–S274.

Article PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar

Culhane, D. (2008). The costs of homelessness: A perspective from the United States. European Journal of Homelessness, 2 , 97–114.

Dordick, G. A. (2002). Recovering from homelessness: Determining the “quality of sobriety” in a transitional housing program. Qualitative Sociology, 25 (1), 7–32.

Article Google Scholar

Draine, J., Salzer, M., Culhane, D., & Hadley, T. (2002a). Poverty, social problems, and serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 53 , 899.

Draine, J., Salzer, M. S., Culhane, D. P., & Hadley, T. R. (2002b). Role of social disadvantage in crime, joblessness, and homelessness among persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 53 , 565–573.

Freund, K. S., & Lous, J. (2012). The effect of preventive consultations on young adults with psychosocial problems: a randomized trial. Health Education Research, 27 (5), 927–945.

Fukui, S., Starnino, V. R., Susana, M., Davidson, L. J., Cook, K., Rapp, C. A., et al. (2011). Effect of Wellness Recovery Action Plan (WRAP) participation on psychiatric symptoms, sense of hope, and recovery. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 34 (3), 214.

Gorman, D. (2010). Maslow’s hierarchy and social and emotional wellbeing. Aboriginal and Islander Health Worker Journal, 34 , 27–29.

Greenwood, R. M., Stefancic, A., & Tsemberis, S. (2013). Pathways housing first for homeless persons with psychiatric disabilities: Program innovation, research, and advocacy. Journal of Social Issues, 69 (4), 645–663.

Henwood, B. F., Stanhope, V., & Padgett, D. K. (2011). The role of housing: a comparison of front-line provider views in housing first and traditional programs. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 38 , 77–85.

Hopper, K. (2007). Rethinking social recovery in schizophrenia: what a capabilities approach might offer. Social Science and Medicine, 65 (5), 868–879.

Hopper, K. (2012). Commentary: the counter-reformation that failed? A commentary on the mixed legacy of supported housing. Psychiatric Services, 63 (5), 461–463.

Hopper, K., Jost, J., Hay, T., & Welber, S. (1997). Homelessness, severe mental illness, and the institutional circuit. Psychiatric Services, 48 (5), 659–665.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Jacobson, N., & Greenley, D. (2001). What is recovery? A conceptual model and explication. Psychiatric Services, 52 , 482–485.

Kenrick, D. T., Griskevicius, V., Neuberg, S. L., & Schaller, M. (2010). Renovating the pyramid of needs. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5 , 292–314.

Kertesz, S. G., Crouch, K., Milby, J. B., Cusimano, R. E., & Schumacher, J. E. (2009). Housing first for homeless persons with active addiction: are we overreaching? Milbank Quarterly, 87 (2), 495–534.

Kiel, J. M. (1999). Reshaping Maslow’s hierarchy of needs to reflect today’s educational and managerial philosophies. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 26 , 167.

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50 , 370–396.

Maslow, A. H. (1970). Motivation and personality (2nd ed.). New York: Harper & Row.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook . Los Angeles: Sage.

Nelson, G., Lord, J., & Ochocka, J. (2001). Empowerment and mental health in community: Narratives of psychiatric consumer/survivors. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 11 , 125–142.

Nussbaum, M. C. (2006). Frontiers of justice: disability, nationality, species membership . Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Ochocka, J., Nelson, G., & Janzen, R. (2005). Moving forward: Negotiating self and external circumstances in recovery. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 28 , 315–322.

Onken, S. J., Craig, C. M., Ridgway, P., Ralph, R. O., & Cook, J. A. (2007). An analysis of the definitions and elements of recovery: a review of the literature. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 31 , 9–22.

Padgett, D. K. (2007). There’s no place like (a) home: Ontological security among persons with serious mental illness in the United States. Social Science and Medicine, 64 (9), 1925–1936.

Padgett, D. K. (2008). Qualitative methods in social work research . Los Angeles: Sage.

Padgett, D. K., Smith, B., Henwood, B. F., & Tiderington, E. (2012). Life course adversity in the lives of formerly homeless persons with serious mental illness: context and meaning. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 82 , 421–430.

Palinkas, L. A., Horwitz, S. M., Chamberlain, P., Hurlburt, M. S., & Landsverk, J. (2011). Mixed-methods designs in mental health services research: A review. Psychiatric Services, 62 (3), 255–263.

Pearson, C., Montgomery, A. E., & Locke, G. (2009). Housing stability among homeless individuals with serious mental illness participating in Housing First programs. Journal of Community Psychology, 37 (3), 404–417.

Rawls, J. (1971). A theory of justice . Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Ridgway, P. (2001). Restorying psychiatric disability: Learning from first person recovery narratives. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 24 , 335–343.

Roychowdhury, A. (2011). Bridging the gap between risk and recovery: a human needs approach. The Psychiatrist, 35 , 68–73.

SAMHSA (2011). SAMHSA announces a working definition of “recovery” from mental disorders and substance use disorders. Retrieved July 11, 2012, from http://www.samhsa.gov/newsroom/advisories/1112223420.aspx .

Sandelowski, M. (2001). Real qualitative researchers do not count: The use of numbers in qualitative research. Research in Nursing & Health, 24 , 230–240.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Stake, R. E. (1995). The art of case study research . Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Stefancic, A., & Tsemberis, S. (2007). Housing First for long-term shelter dwellers with psychiatric disabilities in a suburban county: A four-year study of housing access and retention. J Prim Prev, 28 (3–4), 265–279.

Tondora, J., Miller, R., & Davidson, L. (2012). The Top Ten Concerns about Person-Centered Care Planning in Mental Health Systems. International Journal of Person Centered Medicine, 2 (3), 410–420.

Trattner, W. I. (1998). From poor law to welfare state: A history of social welfare in America (6th ed.). New York: Free.

Tsemberis, S., & Eisenberg, R. F. (2000). Pathways to housing: Supported housing for street- dwelling homeless individuals with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D. C.), 51 (4), 487–493.

Tsemberis, S., Gulcur, L., & Nakae, M. (2004). Housing First, consumer choice, and harm reduction for homeless individuals with a dual diagnosis. American Journal of Public Health, 94 , 651–656.

Viron, M., Bello, I., Freudenreich, O., & Shtasel, D. (2013). Characteristics of homeless adults with serious mental illness served by a state mental health transitional shelter. Community Mental Health Journal, 1–6. doi: 10.1007/s10597-013-9607-5 .

Wahba, M. A., & Bridwell, L. G. (1976). Maslow reconsidered: A review of research on the need hierarchy theory. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 15 , 212–240.

Download references

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 69865).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Social Work, University of Southern California, 1150 S. Olive Street, #1429, Los Angeles, CA, 90015-2211, USA

Benjamin F. Henwood & Julie Couture

Silver School of Social Work, 838 Broadway, 3rd Floor, New York Recovery Study, New York, NY, 10003, USA

Katie-Sue Derejko & Deborah K. Padgett

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Benjamin F. Henwood .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Henwood, B.F., Derejko, KS., Couture, J. et al. Maslow and Mental Health Recovery: A Comparative Study of Homeless Programs for Adults with Serious Mental Illness. Adm Policy Ment Health 42 , 220–228 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-014-0542-8

Download citation

Published : 12 February 2014

Issue Date : March 2015

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-014-0542-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Mental health recovery

- Housing first

- Homelessness

- Serious mental illness

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

May 9, 2024

- Introducing the 2024-2025 Magnuson Scholars

On behalf of the University of Washington, the Board of Health Sciences Deans, and the Magnuson Scholar Program, we are pleased to announce the 2024–2025 Magnuson Scholars.

The Magnuson Scholar Program is a key component of the Warren G. Magnuson Institute for Biomedical Research and Health Professions Training. The program is funded by a 1991 endowment established in the late Senator’s name. The annual income allows the University of Washington to distribute an award to one scholar from each of the six health sciences schools – Dentistry, Medicine, Nursing, Pharmacy, Public Health and Social Work – annually. As was the case in recent years, the endowment allowed a seventh scholar to receive a scholarship.

Each Health Sciences School nominates their specific scholar on the basis of outstanding academic performance and potential contributions to research in the health sciences. All Magnuson Scholars help continue the legacy of the late Senator Warren G. Magnuson and his remarkable commitment to improving the nation’s health through biomedical research, education, and responsive, sustainable healthcare discoveries. Per the endowment, at least one scholar must be engaged in research related to diabetes, it’s antecedents or treatment.

Please join us in recognizing the 2024-2025 Magnuson Scholars’ exceptional achievements while also celebrating Warren G. Magnuson’s extraordinary public service career.

The 2024-2025 Magnuson Scholars are:

Scholar Profiles

Claire Mills, School of De ntistry

Claire Mills is a dual DDS/PhD student at UW. During her dental training, she learned extensively about the challenges in both screening and treating head and neck cancer (HNSCC). This prompted her to pursue a mechanistic study of HNSCC during her PhD.

As a current PhD student, Claire also actively practices dentistry. She screens for head and neck pathologies, including cancer. Her clinical experiences underscore an increased risk of (HNSCC) in specific demographics, including patients with diabetes. She discovered that, despite regular screenings, most cases of oral cancer are not detected until tumors are significantly advanced. These challenges highlight the urgent need for more sensitive clinical screening techniques to identify early cancerous changes before they evolve into tumors.

Slobodan Beronja, PhD, highlights, “Claire adapted an approach for rapid gene targeting of human oral epithelium and cancer in the context of orthotopic transplants. She demonstrated competence, determination, and persistence that I have not seen before. I felt privileged she chose my lab for her training.”

To stop tumor formation from occurring, Claire specifically aims to identify genetic markers of pre-cancer changes in healthy tissues. These efforts will help propel her career to becoming an independent investigator and clinician-scientist, empowering her to focus on scientific pursuits in understanding oral disease, contribute to the field of oral cancer research, and build a successful career combining clinical expertise with scientific research.

Justin Lo aspires to be an academic physician scientist who conducts data-driven research focused on risk factors for diabetes and diabetes-related diseases. As an undergraduate student, Justin gained an affinity for the interconnected endocrine system, eventually becoming a teaching assistant for an endocrinology course. His undergraduate studies provided background for his research in obesity-related population health at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME).

This past summer, Justin was an NIDDK Medical Student Researcher working with the Brain, Body, and Appetite Research Collaborative on a cohort analysis investigating the relationships between inflammation in body weight and glucose-regulating areas of the brain, as well as several metabolic diseases, including diabetes. He presented at the Western Medical Research Conference and was awarded the student subspecialty award in endocrinology.

Ellen A. Schur, MD, MS Professor, Medicine states, “Justin’s capacity to interpret results, compose a manuscript, and communicate findings is beyond his stage of training. He is at the level of a skilled postdoctoral scholar or above. Justin remains engaged and will continue his research with us by investigating genetic risk factors for hypothalamic gliosis. I believe he will grow into a creative and rigorous physician-investigator.”

In pursuit of a career as a physician scientist, Justin is committed to lifelong learning and professional growth. He recognizes that his analytical skillset will be valuable as medicine heads towards an era of big data. Justin’s hope is to complete a fellowship after residency, applying his skills to emerging data-driven topics such as metabolomics and diabetes. Ultimately, Justin strives for evidence-based approaches that can ameliorate the significant burden of diabetes on individuals and communities.

Elizabeth Frazier’s commitment to cardiovascular health is deeply rooted in her clinical experiences as a cardiovascular intensive care nurse. Witnessing her family navigate the burdens of living with chronic cardiac arrhythmias, particularly atrial fibrillation (AF), was the impetus for pursing a future career as a nurse scientist. Her dissertation research has the potential to advance current understanding of the links between cardiovascular disease and diabetes.

“Atrial fibrillation,” explains Elizabeth, “is the most common cardiac arrhythmia in the U.S. and is recognized as a growing epidemic. This irregular heart rhythm is often accompanied by distressing symptoms, including palpitations, fatigue, and shortness of breath. My research examines social support and the biological markers, epicardial adipose tissue and adipokines, as potential mechanisms contributing to AF symptoms differences in women and men.”

Cynthia M. Dougherty, ARNP, PhD, FAHA, FAAN Professor explains, “The link between diabetes and AF is well established, but Ms. Frazier’s focus on epicardial adipose tissue and adipokines have relevant potential to add depth to our understanding of the mechanisms connecting diabetes, AF, and sex and gender differences in diabetes and AF outcomes.”

Ms. Frazier has a long-term goal of developing biobehavioral interventions that alleviate the symptom burdens of women with cardiac arrhythmias. To achieve her goal, Elizabeth is building a program of study that expands her knowledge in advanced methodologies, statistics, and responsible, ethical research. She feels privileged to be embedded in a team of expert cardiovascular nursing researchers, led by Dr. Dougherty, and to have gained direct research experience working as a Research Assistant with Dr. Megan Streur. Through these experiences, Elizabeth is developing skills to lead her own future interdisciplinary research team and program of research.

Yue (Winnie) Wen graduated with a bachelor’s degree in Pharmaceutical Sciences and joined the Department of Pharmaceutics at UW due to her passion for scientific research. “My thesis projects,” explains Winnie, “center on liver fatty acid binding protein (FABP1) and its role in lipid and drug distribution and metabolism. Given that studies have linked FABP1 polymorphism with type 2 diabetes mellitus, I am keen to improve understanding the role of this variant in metabolic disorders, diabetes and their treatments.” By leveraging experimental, mathematical, and statistical methods, Winnie aims to improve clinical decision-making by translating in vitro and in vivo research findings into practical clinical applications.

Her involvement in diabetes and health science research has not only refined her expertise. It also deepened her commitment to the field of drug development. During a summer internship she observed the intricacies of the drug development pipeline, realizing how her contributions could translate into the clinical real-world.

Dr. Nina Isoherranen states, “During Winnie’s rotation in my lab she impressed me with her ability to analyze literature, independently develop and verify PBPK models, gain expertise in Matlab, integrate parent-metabolite kinetic models with enzyme kinetic information, and finally apply all of this into a pregnancy PBPK model that incorporates changes in kidney clearance during pregnancy. The model she developed can predict drug disposition in treatment of gestational diabetes and expand to diabetic kidney disease.” It is Winnie’s hope that by customizing therapies to individuals, she will pioneer personalized medicine in health care, reducing patient discomfort and enhancing clinical outcomes.

“I am driven to make an impact on individuals affected by prevalent conditions such as diabetes,” states Winnie. “Through my coursework in drug metabolism, pharmacokinetics, biostatistics, and applied mathematics I aspire to contribute to a future where such diseases are effectively managed and no longer pose threats to the patients.”

Amanda Brumwell’s goal as a research scientist is to help address the significant disparities witnessed first-hand in the management of diabetes. She plans to devote her dissertation research to advancing the field of diabetes care by investigating health systems and community-level approaches to managing and preventing type-II diabetes.

“I believe,” explains Amanda, “that this kind of research may help to prepare health systems to manage the burgeoning epidemic of diabetes effectively, efficiently, and equitably. It’s exciting to think that low- and middle-income settings could serve as exemplars of success.”

Her work as Managing Director at the nonprofit Advance Access & Delivery, allowed her to oversee two projects, in Durban, South Africa and Chennai, India. Both projects integrated diabetes and hypertension screening and linked to care with local tuberculosis control programs.

Amanda discovered a deep disparity between an alarming burden of diabetes and the lack of financial, structural, and political resources made available for this disease. She believes that, given the huge advances in clinical management of diabetes during recent years, there is significant opportunity for low- and middle-income settings to translate these practices to a real-world setting. Paving the way for novel strategies of treatment and preventing diabetes at a community- and population-level show great potential.

Kenneth Sherr PHD, MPH states, “Amanda is a superlative student with a strong background in implementation of health programs that address diabetes in low and middle-income countries. She is well positioned to build on this implementation experience and scientific training to move towards an independent research career that makes an impact on addressing the unmet diabetes burden globally.”

Prevention of chronic diseases like diabetes and hypertension, by improving childhood nutrition for Latinx communities via policies that promote a healthy lifestyle, is Miriana Duran’s foremost goal. Before moving to the United States, Miriana worked as a physician in Mexico, where diabetes is the second leading cause of death. “I realized,” states Miriana, “I couldn’t address some of the structural barriers or risk factors related to their illness as a physician.”

Having worked on multiple projects addressing disparities in chronic disease care and outcomes within the Latinx community, Miriana worked on a project that adapted an existing in-person program for caregivers of people with dementia (STAR-C) into a virtual program (STAR-VTF) using a cultural adaptation framework to meet the cultural and linguistic needs of Latinx caregivers. She also worked within the Latino community in rural areas in Washington state including one in which she and her team taught community health workers to identify and implement evidence-based interventions for cancer prevention.

Jessica Jones-Smith, PhD, MPH, RD, explains, “Miriana’s experience as a physician in Mexico, working with patients with obesity and diabetes, fuels her research interests and provides a valuable perspective. She is able to work collaboratively as part of a team, and also skilled enough to make great strides in this field independently.”

Her bilingual, bicultural skills help coordinate, adapt and implement culturally appropriate programs on different topics for the Latinx community. For her dissertation she intends to focus on and examine the health impacts of Seattle’s Fresh Bucks Program. Fresh Bucks is an incentive program that provides $40 per month for fruits and vegetables for lower-income Seattle residents.

Miriana draws on her interpersonal skills, life experience, background knowledge of the relevant literature, and familiarity in qualitative research methods to develop her dissertation ideas. Her intellectual ability and drive to become a leader in public health research will enable Miriana’s work to benefit communities that have been historically marginalized.

Aiming to disrupt the foster care to prison pipeline, Hannah Scheuer partners with youth, parents, and social workers, intending to interrogate a systems failure that perpetuates inequity, family instability, and poor health outcomes in Washington state. As Hannah explains, “both foster care and youth incarceration are associated with long-term negative outcomes including physical and mental health concerns and lifelong economic instability which inhibits access to quality health care. Young people in foster care or the juvenile legal system experience health problems including untreated diabetes and hypertension, sexual and reproductive conditions, respiratory and dental concerns, substance use disorders, and suicidality, at much higher rates than the general adolescent population.”

Disruption of this pipeline requires an analysis of the various points at which child welfare, juvenile legal, and legal systems intersect. Hannah’s research goal is to offer potential alternatives from the perspectives of parents and young adults who have experienced child welfare involvement and social workers who work within these systems in Washington state.

Hannah’s primary doctoral advisers, Margaret Kuklinski, PhD and Emiko Tajima, PhD believe her dissertation research and career objectives beautifully exemplify the strong potential for immediate impact as it’s a timely response to the current call for system alternatives. It emerges from the perspectives of those with lived expertise, where Hannah is conducting in partnership with a community-based coalition eager to advance evidence-informed policy and systems change.

Hannah’s research and goals will contribute to an impactful dissertation and propel a career that keeps families and communities center stage. By addressing translational research questions using mixed methods, Hannah hopes to achieve her goal of guiding tangible change.

- 2023-2024 Magnuson Scholar Winter Updates

- 2023-2024 Magnuson Scholar Recognition Luncheon

- UW Health Sciences Education Building Wins National Award

- Dr. Alice Ko, a 2023-2024 Magnuson Scholar, Featured in UW School of Dentistry News

- Magnuson Scholar Alex Wiley Featured in UW School of Pharmacy News

Be boundless

Connect with us:.

© 2024 University of Washington | Seattle, WA

Guppy Life Cycle and Growth Stages – Guides and More

When talking about one of the most popular fish in the world, it’s natural to wonder how long they live and what their life cycle is like. For many people, guppies are the gateway fish – the first freshwater fish they ever kept. Though often thought of as a “starter fish,” Guppies can be found in nearly every corner of the world and come in a wide variety of colors and patterns.

In this article, we’ll take a look at the life cycle of a guppy – from birth to adulthood – and discuss some of the different stages of growth they go through. We’ll touch on some of the key facts you need to know about each stage, and give you some pointers on how to care for your fish at each stage of their lives.

Table of Contents

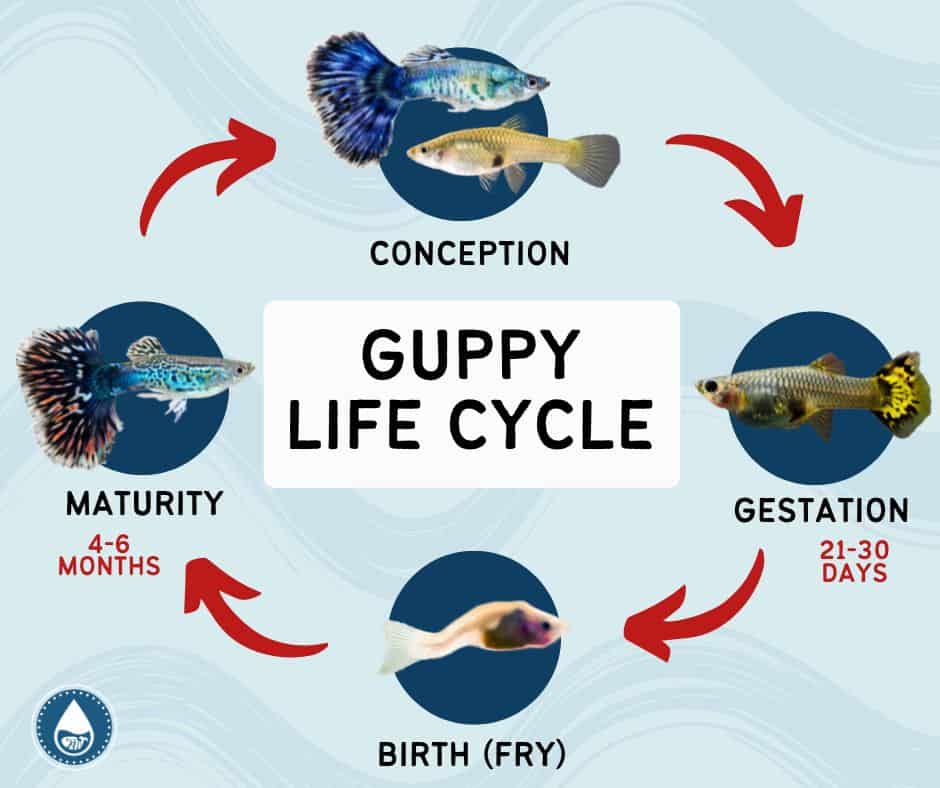

Guppy Life Cycle

Guppies are livebearers, which means that they give birth to live young rather than laying eggs. The gestation period for a guppy is usually between 21 and 30 days, though it can be as short as two weeks in some cases. However, the life cycle of a guppy actually begins with the breeding of guppies – at conception.

Size (In/Cm)

Fully transparent

Juvenile Guppy

0.47 to 0.78 in

1.2 cm to 2 cm

Subtly colored

Young Guppy

¾ in and 2 in

8.89cm and 5.08 present

Present vibrant colors

Adult Guppy

Adult (Months 4-6)

2.5 to 3 in

6.35 to 8.62

Size (Inches/Cm)

0.24 in/0.6cm

0.47 to 0.78 in/1.2 cm to 2 cm

¾ in and 2 in/8.89cm and 5.08 present

present vibrant colors

2.5 to 3 in/6.35 to 8.62

Commonly considered the beginning of the guppy life cycle, conception is when a male and female guppy mate. This can happen either by chance – if you have a population of guppies consisting of mixed males and females – or on purpose, if you’re breeding guppies.

During mating, the male will chase the female and “nip” at her fins in order to get her attention. Typically, several different males will attempt to mate with a single female. Duller males are often ignored in favor of more fit males. If the female is interested, she will allow the male to swim alongside her and tap her body with his.

Mating is a relatively quick process – lasting only a few seconds to a minute – during which the male will deposit his sperm inside the female. The female can store the sperm and use it to fertilize her eggs for several weeks, allowing her to give birth multiple times without having to mate again.

After conception, the female will begin to show signs of pregnancy – known as gestation. Most guppies have a gestation period of 21-30 days, after which the female guppy will give birth to anywhere from 5 to 100 live young. The number of babies a guppy has varies depending on the size and health of the mother, as well as the water conditions they’re kept in.

Pregnant females need extra care and attention, as they are more susceptible to stress and disease. They also need plenty of food – especially live foods such as blood worms – to support the baby guppies growing inside them. Your pregnant fish will also start to look “rounded” as her belly swells with the developing fry.

You’ll also want to pay attention to the gravid spot – a dark patch on her belly that is visible when she’s pregnant. This dark spot will get larger as the pregnancy progresses, and is usually a good indicator of when the pregnant guppy is due to give birth. In some cases, you’ll even spot tiny guppy eyes peering out from the gravid spot!

Whether you’re dealing with a common guppy or a fancy guppy, the birthing process is relatively similar. To start with, you’ll need to provide clean water that’s well-suited for the needs of newborn fry. You’ll be dealing with a brood size of dozens of fish, so a larger tank is best. Aim for at least 10 gallons, and make sure it is well-heated.

When the time comes, the mother guppy will “drop” her fry – usually at night while everyone is sleeping. The fry are born fully formed and independent, and will quickly start to swim away from their mother. Like most animal species, the fry are born weak and vulnerable, and need time to grow and develop. However, they will start to eat and swim on their own almost immediately.

The survival rate for newborn guppy fry will vary depending on the conditions they’re kept in. Keeping your guppy fry alive is a matter of providing them with the cleanest water possible and hiding places for them to hide from predators. Many fry will also die due to cannibalism, so be sure to remove all adult fishes (even their parents) from the breeding tank as soon as possible.

Guppy Fish Growth Stages

Now that we have a better understanding of how a guppy’s life cycle works, let’s take a look at the different guppy growth stages. The distinction between these stages is important, as it will help you determine the best care for your fish at each stage of their lives.

Guppy fry are born fully-formed and independent but still very small. By the end of the first 30 days of their lives, they average just 0.24 inches or 0.6 centimeters in length. At this stage of their lives, guppies also lack the bright coloration of their adult counterparts. Realistically speaking, your fry will look like tiny, drab versions of their parents.

As one would expect, the conditions of food availability, water quality, and tank mates will all play a role in how quickly the fry grow. Fry cannot digest pellets and flakes at this juncture, nor can they take on larger chunks of protein. However, things like mosquito larvae and daphnia are perfect for their needs. You can also purchase special fry foods from your local fish store.

Some beginner fishkeepers also wonder how often to feed the fry. The best answer is “as much as they can eat.” Fry have tiny stomachs, so they need to eat small meals several times a day. Shoot for 3-5 meals daily, and remove any uneaten food immediately to prevent water quality issues. This way, you can be sure your fry are getting the nutrition they need to survive.

Between days 30-60, your fry will transition into the juvenile stage. At this point, they will start to develop subtle colors and patterns on their bodies. They will also begin to develop the “swordlike” dorsal fins that are characteristic of male guppies. While juvenile guppies are still tiny, they are considerably larger than fry at between 0.47 to 0.78 inches.

Frequent water changes are a must under every circumstance, but they’re especially important during the juvenile stage. Because their growth rate is so rapid, guppy fry produce a lot of waste. Ammonia and nitrites can quickly build up in the water, leading to serious water quality issues and disease. It’s crucial that you keep a close eye on water conditions to keep your guppies healthy.

As with fry, feeding juvenile guppies is all about providing them with small meals several times a day. You can start to introduce pellets and flakes into their diet, but make sure they are small enough for the fry to eat. You should still ensure that they have sufficient fat intake to support their growth, so live foods should still make up a large part of their diet.

At between 2-4 months of age, your guppies will transition into the young adult stage. At this point, they will be fully grown, and their coloration will be close to what it will be as adults. Male guppies will also have fully-developed “swords” on their dorsal fins. In short, your guppies will start resembling the colorful fish you see in pet stores.

Sexual dimorphism, or the ability to distinguish males from females, also becomes apparent during the young adult stage. Male guppies tend to be smaller than females and have brighter colors. Females, on the other hand, are larger with duller colors. This difference is because males need to be more conspicuous to attract mates, while females need to be less visible to avoid predators.

Young guppies aren’t able to reproduce yet, so you won’t see a wide variety of behavioral differences between males and females at this stage. However, you may notice that your males become more aggressive as they begin to vie for dominance within a shared community tank. Though guppies are fundamentally peaceful fish, aggression shouldn’t be a major issue.

To make the most of their young adult stage, be sure to provide your guppies with a varied and nutritious diet. They no longer require abundant food several times a day, but they should still have 3-4 small meals every day. A diet rich in live foods, high-quality flake foods, and freeze-dried foods will help your guppies stay healthy and thrive.

Maturity/Adult Guppy

Between 4-6 months of age, guppies enter their adult stage. At this point, they will be fully grown, measuring up to 3 inches in length on average. Each will also feature bright, attention-grabbing coloration, and males will have well-developed dorsal fins. Females, on the other hand, will be rounder in shape with much shorter fins.

Mature guppies can start reproducing at the 20-week, or 5-month mark. Females will be ready to lay eggs every 4-6 weeks, so you can expect a lot of fry if you don’t take steps to prevent it. If you want to avoid an explosion in your guppy population, it’s best to remove pregnant females and raise the fry separately.

Nutrition-wise, adult guppies still thrive on a wide variety of food, but need fewer meals than fry or juveniles. 2-3 small meals per day should be sufficient to keep your guppies healthy. A diet rich in live foods, high-quality flake foods, and freeze-dried foods will help your guppies stay healthy and thrive.

How Long Do Guppies Live?

Guppies have a life span of 2-5 years, but the average guppy raised in captivity will live for 3 years with proper care. Wild guppies tend to have better odds of survival, as they are more accustomed to their natural environment. In captivity, guppies are more susceptible to disease and water quality issues, which can shorten their life span.

Some common health problems that can shorten a guppy’s life span include:

- Ich: A common fish disease caused by a parasitic infection. Symptoms include white spots on the fish’s body, lethargy, and a loss of appetite.

- Gill flukes: A parasitic infection that attacks a fish’s gills, causing difficulty breathing. Symptoms include gasping at the surface of the water and increased mucus production.

- Fungal infections: A common fish disease caused by a fungal infection. Symptoms include white spots on the fish’s body, lethargy, and a loss of appetite.

To help your guppies stay healthy and live a long life, be sure to provide them with a clean and well-maintained aquarium. A diet rich in live foods, high-quality flake foods, and freeze-dried foods will also help your guppies stay healthy and thrive.

The Takeaway

Guppies are an excellent choice for beginner fishkeepers, as they are relatively easy to care for and can live in a wide range of water conditions. With proper care, your guppies will bring you years of enjoyment. Watching them grow from fry to adults is a rewarding experience, and you’ll get to witness the magic of reproduction as they produce fry of their own.

We hope this guide has given you everything you need to know about caring for guppies. If you know someone who’s thinking about getting into fishkeeping, be sure to share this guide with them. And if you have any questions or tips of your own, feel free to leave a comment below. Happy fishkeeping!

Wanda is a second-generation aquarist from the sunny tropics of Malaysia. She has been helping her father with his freshwater tanks since she was a toddler, and has fallen in love with the hobby ever since. A perpetual nomad, Wanda does her best to integrate fish-keeping with her lifestyle, and has taken care of fish in three different continents. She loves how it provides a nice break from the hustle and bustle of life.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

BTEC Tech Award Level 1/2 Health & Social Care 3 Component 1 Learning content to be covered A1 Human growth and development across life stages Learners will explore different aspects of growth and development across the life stages using the physical, intellectual, emotional and social (PIES) classification.

M1 Describe the role of the health and social care practitioner: o in preparing individuals for a planned transition at each life stage o in supporting the needs of individuals during transition and significant life events at each life stage. D1 Describe the effects of an unplanned transition on an individual during one (1) life stage. An ...

an overview of the key life stages of development and links to the relevant P.I.E.S of each stageMusic: www.bensound.com Track: All that

essential knowledge and understanding for health and social care practitioners. A1 Growth and development across life stages A2 Factors affecting growth and development Lifestages 1. Infancy (0 - 2 years) a) 2. Early childhood (3 - 8 years) b) 3. Adolescence (9 - 18 years) choices 4. Early adulthood (19 - 45 years) c) 5.

Health & Social Care — Topic 1 Human Growth & Development Across Life Stages INTRODUCTION Many changes OCCU across the course of a human's life. In this topic you will explore different aspects of growth and development across the life stages COURSEWORK TIPS: Research and write a report to explain how an

Major life events can trigger significant changes in a person's life, influencing their physical health, emotional well-being, relationships, lifestyle, self-esteem and views on life. In terms of physical impact, major life events can result in changes in growth, level of fatigue, immune system function and susceptibility to disease.

Sarah Ash and Sarah Millington - Subject Advisors for Health and Social Care, and Child Development. In this blog we consider how to approach teaching and learning of life stages for R033 which is the mandatory NEA unit for Cambridge National Health and Social Care, J835. This addresses the teaching content of how we grow and develop in terms ...

The life-course approach is about recognizing the importance of these stages, and WHO/Europe addresses them in four programmes: Maternal and newborn health, Child and adolescent health, Sexual and reproductive health, and Healthy ageing. The Gender programme works across all others, applying a cross-cutting analysis to the impact of gender ...

pdf, 240.55 KB. Resources include outstanding lessons for complete LO1 for R025 within the OCR cambridge nationals health and social care qualification. Lessons preparing learners for coursework on LO1. All resources for the lessons are included. Structure includes recap questions at the start, main learning, and a reflection on the learning.

Year 10 - OCR Level 1/Level 2 Cambridge National in Health and Social Care Teacher Ms Nyabango (COURSEWORK) New qualification. UNIT R033: Supporting individuals through life events. TERM 1 TERM 2 TERM 3. CONTENT. Growth and development through life stages. • Life stages and key milestones of growth and development for age groups.

Qualification J835 Unit R033 Unit Recording Sheet. Please read the instructions printed at the end of this form. A Unit Recording Sheet must be completed for each candidate and unit. Brief description of growth and development of the individual through the life stage, using PIES. Sound description of growth and development of the individual ...

This unit is assessed by an exam. The exam is 1 hour and 15 minutes and has 70 marks in total. TA 1: The rights of service users in health and social care settings. Types of care settings Rights of service users The benefits to service users' health and wellbeing when their rights are maintained. TA 2: Person-centred values.

CCEA GCSE Health and Social Care from September 2017 11 Version 2: 28 November 2019 3.2 Unit 2: Working in the Health, Social Care and Early Years Sectors In this unit, students develop their understanding of the world of work in the health, social care and early years sectors and how the needs of different service user groups are met.

GCSE Health and Social Care (2017) The CCEA GCSE Health and Social Care specification provides opportunities for students to develop a broad knowledge and understanding of what is required for working in the health, social care and early years sectors. In particular, they learn about: human development through the main life stages and age ranges;

Health and Social Care Scheme of work - R033 Supporting individuals through life events About this scheme of work Our redeveloped Cambridge National in Health and Social Care J835 is for first teaching from September 2022. This qualification provides lots of flexibility, allowing you to find the best route to suit your centre's needs.

This mixed-methods study uses Maslow's hierarchy as a theoretical lens to investigate the experiences of 63 newly enrolled clients of housing first and traditional programs for adults with serious mental illness who have experienced homelessness. Quantitative findings suggests that identifying self-actualization goals is associated with not having one's basic needs met rather than from the ...

The capacity for health comparisons, including the accurate comparison of indicators, is necessary for a comprehensive evaluation of well-being in places where people live. An important issue is the assessment of within-country heterogeneity for geographically extensive countries. The aim of this study was to assess the spatial and temporal changes in health status in Russia and to compare ...

Join us at 6 PM (WAT) this Thursday May 9, 2024, as our distinguish guest will be discussing the topic: GEN-Z ACCOUNTANTS: Redefining Traditional...

essential knowledge and understanding for health and social care practitioners. A1 Growth and development across life stages A2 Factors affecting growth and development Lifestages 1. Infancy (0 - 1.2 years) a) 2. Early childhood (3 - 8 years) b) 3. Adolescence (9 - 18 years) choices 4. Early adulthood (19 - 45 years) c) 5.

The program is funded by a 1991 endowment established in the late Senator's name. The annual income allows the University of Washington to distribute an award to one scholar from each of the six health sciences schools - Dentistry, Medicine, Nursing, Pharmacy, Public Health and Social Work - annually.

Beyond providing comprehensive pre and perinatal care, the long-term impact of educating each medical intern, licensed clinician, or supervisor in considering identity, intersections, and the ...

Guppy Life Cycle. Guppies are livebearers, which means that they give birth to live young rather than laying eggs. The gestation period for a guppy is usually between 21 and 30 days, though it can be as short as two weeks in some cases. However, the life cycle of a guppy actually begins with the breeding of guppies - at conception.