Understanding College Costs

Resources to help you pay for college..

A common myth about college is that it’s too expensive. But once students understand what college really costs, they often discover that higher education is within their reach.

College Costs Vary

The biggest part of college costs is usually tuition. Tuition is the price you pay for classes. Along with tuition, you’ll probably have to pay some other fees to enroll in and attend a college. Tuition and fees vary from college to college.

Other college costs include room and board, books and supplies, transportation, and personal expenses. Just like tuition, these costs vary from college to college. And students can find ways to save money on most of these expenses.

You can see that the cost of college depends a lot on the choices you make. There’s something else you should know: The published price of attending a college is not usually what students actually pay. They often pay less, thanks to financial aid.

Financial Aid Reduces Your Cost

Financial aid is money given or lent to you to help you pay for college. It may be awarded to you based on your financial need alone, or based partly on factors such as proven academic or athletic ability. Most full-time college students receive some form of financial aid.

The actual, final price (or “net price”) you’ll pay for a specific college is the difference between the published price (tuition and fees) to attend that college, minus any grants, scholarships, and education tax benefits for which you may be eligible.

The difference between the published price and the net price can be considerable. For example, in 2015-16, the average published price of in-state tuition and fees for public four-year colleges was about $9,410. But the average net price of in-state tuition and fees for public four-year colleges was only about $3,980.

So don’t let the prices published on college websites discourage you. The number you actually need to know is the estimated net price for you. How can you figure that out? Almost all colleges offer a net price calculator on their website. You can also use the College Board’s Net Price Calculator to estimate your net price at hundreds of colleges.

To find out more about the actual cost of college, read College Costs: FAQs.

How many college students get financial aid?

Millions of students receive financial aid each year. In 2021-22, undergraduate and graduate students received a total of $234.6 billion in student aid in the form of grants, Federal Work-Study, federal loans, and federal tax credits and deductions.

Can I afford to go to college?

Despite the news stories about rising college prices, a college education is more affordable than most people believe. Many colleges provide an excellent educational experience at a price you can manage. Public college prices are much lower than you might expect, and many private nonprofit colleges provide generous grants and scholarships to offset published costs.

Does applying for financial aid hurt my chances of being admitted?

You’re usually admitted based on your academic performance and the qualities you bring to the campus community. Colleges want to admit a diverse group of students and often use financial aid to achieve that goal. It’s crucial that you apply for financial aid early in the application process before all of a college’s funds are allocated.

Do I qualify for aid even if I don’t get straight A’s?

It's true that some scholarships are awarded based on academic performance. However, most financial aid is based on your family’s financial information provided on an aid application, typically the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) .

Are private colleges out of my reach?

Although the cost of college may be a crucial factor for you, focus instead on finding a college that’s a good fit ─ one that meets your academic, career, and personal needs.

You don’t have to rule out “expensive” schools. Keep in mind that private colleges usually offer generous financial aid to attract students from every income level. Plus, financial aid can come from different sources such as scholarships, grants, and loans. So think about net price (not published price), and don’t be afraid to apply to colleges you think you can’t afford.

Is my family’s income too high to qualify for aid?

Financial aid is intended to make a college education available to students from different financial backgrounds. Family income, the number of family members in college, medical expenses, and other factors may be considered when determining your financial aid eligibility. Even if you think your family income is too high for you to qualify for aid, fill out the Free Application for Federal Student Aid . This form determines your eligibility for federal and state student grants, work-study, and federal loans.

The best way to get an estimate of how much financial aid a college will offer you and therefore how much you’ll really pay to go to that college is to use the college’s net price calculator. Colleges provide these tools on their websites. Net price calculators give you an estimate of your net price for a particular college (i.e., the cost of attendance minus the gift aid you might get). Learn more about net price .

Should I consider working while I’m attending college?

Each student should consider their financial situation and the weight of their studies. Students who choose to work a moderate amount often do better academically. You may find that working a campus job related to your career goal is a good way to manage college costs, get experience, and engage with the university community.

Can I try to get my aid award revised?

Some colleges are willing to review your financial aid package if your financial situation changes. Consider discussing these changes with the financial aid office if your family has experienced an unexpected decrease in income or increase in expenses since you applied for financial aid.

Financial Aid Checklist

Related Articles

See the Average College Tuition in 2023-2024

The average sticker price for in-state public schools is about one-quarter what's charged by private colleges, U.S. News found.

The average college tuition cost has increased in the 2023-2024 academic year over the prior year across both public and private schools, according to U.S. News data based on an annual survey.

A college's sticker price is the amount advertised as the full rate for tuition and fees before financial need, scholarships and other aid are factored in. Net price is the amount that a family pays after aid and scholarships – usually offsetting the sticker price shock.

The average tuition and fees at private ranked colleges has climbed by about 4% over the last year, according to data for the 2023-2024 school year submitted to U.S. News in an annual survey. At ranked public schools, tuition and fees rose 2% for in-state students and about 1.4% for out-of-staters.

Considering inflation, the year-over-year numbers look a little different. For private ranked colleges, tuition and fees actually decreased by 0.4%. For public ranked schools, there was also a decline: about 2% for in-state students and about 3% for out-of-state students.

Schools reported this data in spring and summer of 2023. Some colleges offer tuition discounts to eligible students: 341 private nonprofit colleges and universities reported an average estimated tuition discount rate of 56.2% for full-time, first-year, first-time students in 2022-2023, according to a study from the National Association of College and University Business Officers.

But the cost of education remains a significant financial challenge for many families, who often underestimate the price.

According to the 2023 Fidelity Investments survey College Savings & Student Debt , 1 in 4 high school students believe the total cost of attendance for one year of college equals $5,000 or less. This number is far below what they're likely to pay at public and private four-year colleges.

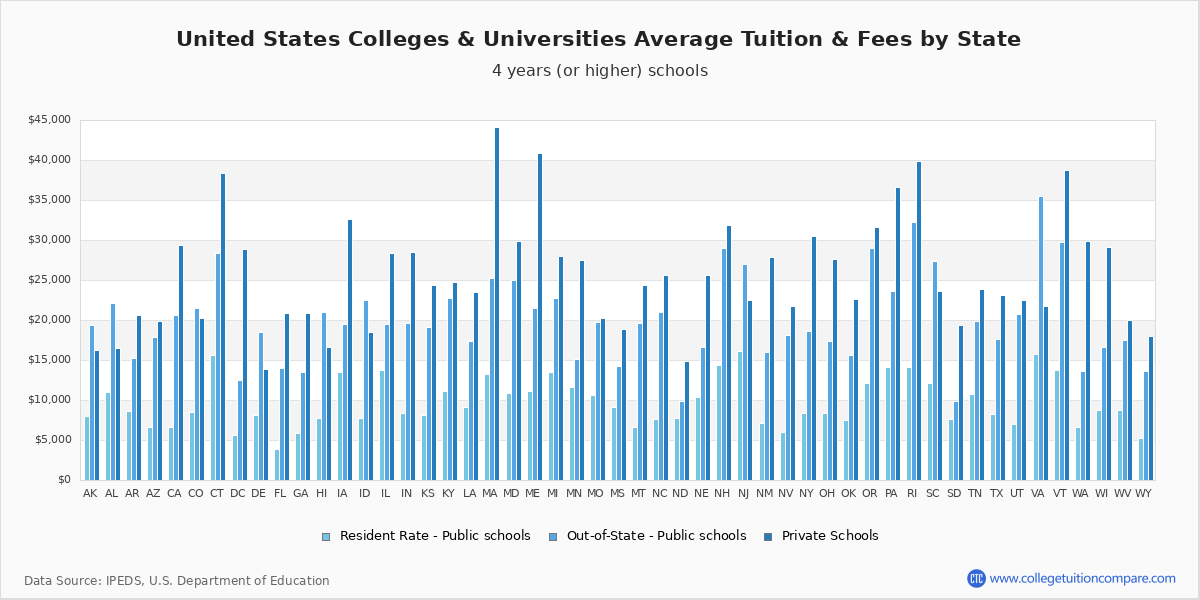

The average in-state cost of tuition and fees to attend a ranked public college is nearly 75% less than the average sticker price at a private college, at $10,662 for the 2023-2024 year compared with $42,162, respectively, U.S. News data shows. The average cost for out-of-state students at public colleges comes to $23,630 for the same year.

In addition to tuition and fees, students must also pay other expenses, such as housing , food and books, which can run thousands of dollars a year.

A Look at the Best Value Schools

But sticker prices don't tell the whole story. Private schools can often make up the price gap through tuition discounts and institutional aid.

While Princeton University in New Jersey, for instance, advertised a sticker price of $57,410 for tuition and fees in 2022-2023, the average cost to students after receiving need-based grants that year was about $17,464.

Since 1993, U.S. News has provided information on the Best Value Schools , looking at academic quality and price, and factoring in the net cost of attendance for a student after receiving the average level of need-based financial aid.

Harvard University is the No. 1 Best Value School among National Universities, schools that are often research-oriented and offer bachelor's, master's and doctoral degrees.

Harvard provided need-based grants to 54% of undergraduates. The highly selective Massachusetts school offered an average need-based scholarship or grant award of $65,053 to undergraduates in 2022-2023. That amount exceeded the school's tuition and fees that year of $57,261, sometimes going toward other costs, like room and board.

Some regional schools, including those not as selective as Harvard, also provide significant need-based financial aid.

For example, although Berry College charged $39,376 in tuition and fees last year, 68% of students received need-based grants. The Georgia institution's financial aid awards in 2022-2023 dropped the average net price for students to $25,630.

Below is a chart showing the top-ranked Best Value Schools in each of the U.S. News categories – National Universities , National Liberal Arts Colleges , Regional Colleges and Regional Universities – along with the percent of undergraduates who received need-based grants and the average cost of attendance after grants.

The data above is correct as of Sept. 20, 2023. For complete cost data, full rankings and much more, access the U.S. News College Compass .

College Tuition Costs

- Average College Tuition in 2023-2024

- What to Know About College Tuition Costs

- Tuition Growth at National Universities

- The Cost of Private vs. Public Colleges

Tags: paying for college , colleges , education , tuition , students , financial aid , college admissions

College Admissions: Get a Step Ahead!

Sign up to receive the latest updates from U.S. News & World Report and our trusted partners and sponsors. By clicking submit, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions & Privacy Policy .

Ask an Alum: Making the Most Out of College

Paying for College

College Financial Aid 101

College Scholarships

College Loan Center

College Savings Center

529 College Savings Plans

Get updates from U.S. News including newsletters, rankings announcements, new features and special offers.

Sign in to manage your newsletters »

Sign up to receive the latest updates from U.S News & World Report and our trusted partners and sponsors. By clicking submit, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions & Privacy Policy .

You May Also Like

Fafsa delays alarm families, colleges.

Sarah Wood March 25, 2024

Help Your Teen With the College Decision

Anayat Durrani March 25, 2024

20 Lower-Cost Online Private Colleges

Sarah Wood March 21, 2024

How to Avoid Scholarship Scams

Cole Claybourn March 15, 2024

What You Can Buy With a 529 Plan

Emma Kerr and Sarah Wood March 1, 2024

What Is the Student Aid Index?

Sarah Wood Feb. 9, 2024

Affordable Out-of-State Online Colleges

Sarah Wood Feb. 7, 2024

The Cost of an Online Bachelor's Degree

Emma Kerr and Cole Claybourn Feb. 7, 2024

How to Use Scholarship Money

Rebecca Safier and Cole Claybourn Feb. 1, 2024

FAFSA Deadlines You Should Know

Sarah Wood Jan. 31, 2024

What's New on the 2024-2025 FAFSA

College Financial Planning for Parents

Cole Claybourn Jan. 29, 2024

How to Find Local Scholarships

Emma Kerr and Sarah Wood Jan. 22, 2024

Help for Completing the New FAFSA

Diona Brown Jan. 11, 2024

Aid Options for International Students

Sarah Wood Dec. 19, 2023

10 Sites to find Scholarships

Cole Claybourn Dec. 6, 2023

A Guide to Completing the FAFSA

Emma Kerr and Sarah Wood Nov. 30, 2023

Are Private Student Loans Worth It?

Erika Giovanetti Nov. 29, 2023

Colleges With Cheap Out-of-State Tuition

Cole Claybourn and Travis Mitchell Nov. 21, 2023

Steps for Being Independent on the FAFSA

Emma Kerr and Sarah Wood Nov. 17, 2023

- Society ›

- Education & Science

The cost of college in the United States - Statistics & Facts

Taking out student loans to afford higher education, is college still worth the cost, key insights.

Detailed statistics

University tuition costs and fees U.S. 2000-2022

Room and board cost per year at U.S. universities 2000-2019

Most expensive colleges in the U.S. 2021-2022

Editor’s Picks Current statistics on this topic

Current statistics on this topic.

Educational Institutions & Market

Total student loans provided in the U.S. 2001-2023

Value of outstanding student loans U.S. 2006-2023

Related topics

Recommended.

- Cost of living U.S.

- Saving for college in the U.S.

- Back-to-college

Recommended statistics

- Basic Statistic Average annual costs of attending a 4-year university U.S. 2000-2022

- Basic Statistic Average undergraduate budgets U.S. 2023/24, by expense and institution type

- Basic Statistic Tuition cost and student loan amounts U.S. 2021/22, by institution type

- Basic Statistic Average debt of university graduates in the U.S. 2008-2022

- Basic Statistic Number of student aid applicants in the U.S. 2006-2022

Average annual costs of attending a 4-year university U.S. 2000-2022

Average annual undergraduate tuition, fees, room, and board for full-time students in four-year postsecondary institutions in the United States from the academic year 2000/01 to 2021/22 (in U.S. dollars)

Average undergraduate budgets U.S. 2023/24, by expense and institution type

Average estimated undergraduate student budget in the United States in academic year 2023/24, by expense category and institution type (in U.S. dollars)

Tuition cost and student loan amounts U.S. 2021/22, by institution type

Average tuition and fees compared to average student loan amount received in the United States 2021/22, by institution type (in U.S. dollars)

Average debt of university graduates in the U.S. 2008-2022

Average university graduate debt levels in the United States from 2008 to 2022 (in U.S. dollars)

Number of student aid applicants in the U.S. 2006-2022

Number of applicants for federal student aid in the United States from 2006/07 to 2021/22 (in millions)

Tuition and fees

- Basic Statistic University tuition costs and fees U.S. 2000-2022

- Basic Statistic Average cost to attend a U.S. university 2013-2024, by institution type

- Basic Statistic Average tuition costs when studying in-state at U.S. universities by state 2018/19

- Premium Statistic Average tuition and fees at U.S. flagship universities 2023-24

- Premium Statistic In-state vs out-of-state tuition at public four-year institutions U.S. 2022, by state

- Premium Statistic Annual tuition and fees at leading universities U.S. 2023/24

- Basic Statistic Room and board cost per year at U.S. universities 2000-2019

- Basic Statistic Most expensive colleges in the U.S. 2021-2022

Average cost for tuition and required fees at all degree-granting postsecondary institutions* in the United States from 2000/01 to 2021/22 (in U.S. dollars)

Average cost to attend a U.S. university 2013-2024, by institution type

Average annual cost to attend university in the United States from 2013/14 to 2023/2024, by institution type (in U.S. dollars)

Average tuition costs when studying in-state at U.S. universities by state 2018/19

Average tuition and fees per year when studying in-state at U.S. universities 2018/19, by state (in U.S. dollars)

Average tuition and fees at U.S. flagship universities 2023-24

Average In-state vs. out-of-state tuition at flagship universities in the United States in academic year 2023-24, by state (in U.S. dollars)

In-state vs out-of-state tuition at public four-year institutions U.S. 2022, by state

Average in-state vs. out-of-state tuition at public four-year institutions in the United States in 2022-23, by state (in U.S. dollars)

Annual tuition and fees at leading universities U.S. 2023/24

Annual tuition and fees for full-time students at leading universities in the United States in 2023/24 (in U.S. dollars)

Average cost for room and board at U.S. universities per year from the academic year of 2000/01 to 2018/19 (in U.S. dollars)

Most expensive colleges in the United States for the academic year of 2021-2022, by total annual cost (in U.S. dollars)

Distribution of student aid

- Basic Statistic Total student grants provided in the U.S. 2002-2023

- Basic Statistic Total student loans provided in the U.S. 2001-2023

- Basic Statistic Graduate student aid in the U.S. 2022/23, by source and type

- Basic Statistic U.S. undergraduate student aid 2022-2023, by source and type

- Basic Statistic Amount of student loans offered, by federal loan program U.S. 2017-2023

- Basic Statistic Amount of student aid paid U.S. 2017-2023, by federal grant program

- Basic Statistic Expenditure on Federal Pell Grants in the U.S. 1981-2023

- Premium Statistic Grant aid as percentage of total state financial support U.S. 2020/21, by state

Total student grants provided in the U.S. 2002-2023

Total amount provided in student grants in the United States from 2002/03 to 2022/23 (in billion 2022 U.S. dollars)

Total amount provided in student loans in the United States from 2002/01 to 2022/23 (in 2022 billion U.S. dollars)

Graduate student aid in the U.S. 2022/23, by source and type

Amount of graduate student aid provided in the United States in the academic year 2022/23, by source and type (in billion U.S. dollars)

U.S. undergraduate student aid 2022-2023, by source and type

Amount of undergraduate student aid provided in the United States in 2022-2023 (in billion U.S. dollars)

Amount of student loans offered, by federal loan program U.S. 2017-2023

Total amount of student aid distributed in the United States, by federal loan program from 2017/2018 to 2022/2023 (in 2022 million U.S. dollars)

Amount of student aid paid U.S. 2017-2023, by federal grant program

Total amount of student aid distributed in the United States from 2017/2018 to 2022/2023, by federal grant program (in 2022 million U.S. dollars)

Expenditure on Federal Pell Grants in the U.S. 1981-2023

Total expenditure on Federal Pell Grant Awards in the United States from 1981/82 to 2022/23 (in billion 2022 U.S. dollars)

Grant aid as percentage of total state financial support U.S. 2020/21, by state

Share of the total state support for higher education spent on grant aid in the United States in the 2020/21 academic year, by state

Student aid received

- Basic Statistic Share of students receiving student aid in the U.S. 2020-2021, by type of aid

- Basic Statistic Percentage of U.S. students with student loans 2020/21, by institution type

- Basic Statistic Share of Federal Pell Grants recipients U.S. 2012-2023

- Basic Statistic Recipients of Federal Pell Grants in the U.S. 1980-2023

- Basic Statistic Share of U.S. students' expenses covered by Pell grants 2003/04-2023/24

- Basic Statistic Total Education tax savings for college students U.S. 2002-2023

- Premium Statistic Student grant aid at public 2-year institutions U.S. 2006-2023

- Premium Statistic Student grant aid at public 4-year institutions U.S. 2006-2023

- Premium Statistic Student grant aid in private nonprofit 4-year institutions U.S. 2006-2022

Share of students receiving student aid in the U.S. 2020-2021, by type of aid

Share of university students receiving student aid in the United States for the 2020/21 academic year, by type of aid and institution

Percentage of U.S. students with student loans 2020/21, by institution type

Percentage of students attending 2-year and 4-year institutions who have student loans in the United States 2020/21, by type of institution

Share of Federal Pell Grants recipients U.S. 2012-2023

Share of Federal Pell Grant recipients in the United States, as percentage of total undergraduate enrollment from 2012/13 to 2022/23

Recipients of Federal Pell Grants in the U.S. 1980-2023

Number of recipients of the Federal Pell Grant Award in the United States from 1980/81 to 2022/23 (in millions)

Share of U.S. students' expenses covered by Pell grants 2003/04-2023/24

Percentage of U.S. students' expenses for tuition fees, room and board covered by Pell grants from 2003/2004 to 2023/2024

Total Education tax savings for college students U.S. 2002-2023

Total Education tax savings for college students and their parents across the United States from 2002/2003 to 2022/2023 (in billion 2022 U.S. dollars)

Student grant aid at public 2-year institutions U.S. 2006-2023

Average grant aid per student at public two-year institutions in the United States from academic year 2006/07 to 2022/23 (in U.S. dollars)

Student grant aid at public 4-year institutions U.S. 2006-2023

Average grant aid per student at public four-year institutions in the United States from academic year 2006/07 and 2022/23 (in U.S. dollars)

Student grant aid in private nonprofit 4-year institutions U.S. 2006-2022

Average grant aid per student at private nonprofit 4-year institutions in the United States from academic year 2006/07 to 2022/23 (in U.S. dollars)

Student debt

- Premium Statistic Value of outstanding student loans U.S. 2006-2023

- Basic Statistic Average student debt for a 4-year bachelor's degree, by institution type U.S. 2020/21

- Basic Statistic Per capita debt of university graduates in the U.S. 2003-2019

- Basic Statistic Share of U.S. graduates with debt 2003-2019

- Basic Statistic U.S. student loan borrowers' debt levels in public four-year colleges 2006-2022

- Basic Statistic U.S. student loan borrowers' debt levels, private four-year colleges 2006-2022

- Basic Statistic Average student debt U.S. 2020, by state

- Premium Statistic Share of Americans with student loan debt U.S. 2023, by state

- Basic Statistic Student loan cohort default rate in the U.S. 2019, by institution type

- Basic Statistic Average student debt of students at top U.S. universities 2023

- Premium Statistic Students with federal loans for higher education U.S. 2023, by repayment status

Value of outstanding student loans in the United States from Q1 2006 to Q3 2023 (in billion U.S. dollars)

Average student debt for a 4-year bachelor's degree, by institution type U.S. 2020/21

Average student loan debt for a four-year bachelor's degree in the United States in 2020/21, by institution type (in U.S. dollars)

Per capita debt of university graduates in the U.S. 2003-2019

Per capita graduate debt levels in the United States from the academic year of 2003/04 to 2018/19 (in U.S. dollars)

Share of U.S. graduates with debt 2003-2019

Share of graduates with debt in the United States from the academic years 2003/04 to 2018/19

U.S. student loan borrowers' debt levels in public four-year colleges 2006-2022

Average amount of debt per borrower at public four-year colleges and universities in the United States from 2006/07 to 2021/22 (in 2022 U.S. dollars)

U.S. student loan borrowers' debt levels, private four-year colleges 2006-2022

Average amount of debt per borrower at private nonprofit four-year colleges and universities in the United States from 2006/07 to 2021/22 (in 2022 U.S. dollars)

Average student debt U.S. 2020, by state

Average debt of university graduates in the United States in 2020, by state (in U.S. dollars)

Share of Americans with student loan debt U.S. 2023, by state

Share of Americans who have some form of student loan debt in their name in the United States in 2023, by state of residence

Student loan cohort default rate in the U.S. 2019, by institution type

Percentage of students in default on student loans after attending 2-year and 4-year institutions United States in 2019, by institution type

Average student debt of students at top U.S. universities 2023

Average student debt of students at the top 20 U.S. universities in 2023 (in U.S. dollars)

Students with federal loans for higher education U.S. 2023, by repayment status

Distribution of federal education loan recipients in the United States as of second quarter fiscal year 2023, by repayment status

Further reports Get the best reports to understand your industry

Get the best reports to understand your industry.

- The student debt crisis in the U.S.

Mon - Fri, 9am - 6pm (EST)

Mon - Fri, 9am - 5pm (SGT)

Mon - Fri, 10:00am - 6:00pm (JST)

Mon - Fri, 9:30am - 5pm (GMT)

How are college costs adding up these days and how much has tuition risen? Graphics explain

College decision day is closing in and many prospective students are making commitments to their university of choosing. With that commitment comes an enrollment deposit – one of many fees students will pay in the next four years.

Of the more than 60,000 high school graduates, 64% will go on to enroll in two- or four-year college programs. Many will incur debt and join the already 43.5 million Americans who have student loans.

Last year, President Joe Biden's student debt cancellation plan was struck down by the Supreme court. Now he's proposing a workaround that could cancel the loans of more than four million borrowers, according to the White House . In addition, more than 10 million borrowers could get $5,000 in debt relief.

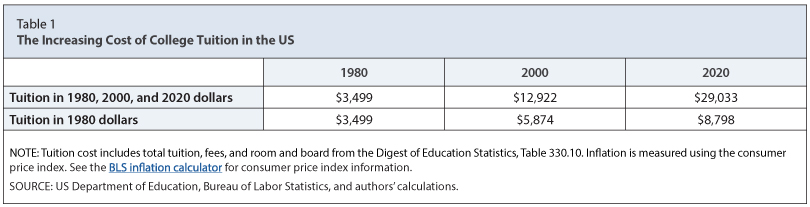

Whether or not the new proposal works, many college students will be paying nearly two-fold what their parents paid for an undergraduate education 20 years earlier. According to the Education Data Initiative, the average cost of college tuition and fees at public four-year institutions has risen 179.2% over the last two decades.

How much does college tuition cost?

The average cost of an undergraduate degree ranges from $25,707 to over $218,000 , according to the Education Data Initiative. The price varies and depends on whether a student lives on campus and the institution they're attending.

According to the most recent data from the Education Department, the average tuition at a four-year private nonprofit university increased 14% between the fall of 2010 and fall of 2021.

Chart shows rise in cost of 4-year college

In 2023, the average full time student at a four-year college spent nearly $31,000 on their tuition fees, room and board for the year. That number is more than double amount paid for the same education in the 1960s, adjusted for inflation in 2022-2023 dollars.

Why is college tuition rising?

The demand for a college education is going up – at the same time government funding for postsecondary education is on the decline, according to Bankrate.

The personal finance website pointed out several key areas that have lead to an increase in tuition costs:

- The cost of operation is increasing, due to rising inflation. The inflation rate increased 3.5% between March 2023 and 2024, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. With rising inflation comes increased cost of living. Universities must pay highly educated professors more to keep up with rising living costs.

- A reduction in state funding led to increased tuition costs, according to the National Education Association. An analysis from NEA found that state funding for higher education decreased in 37 states by an average of 6% between 2020 and 2021.

- Colleges are spending more on administrative services: A 2021 study found that between 2010 and 2018, spending on student services and administration grew by 29% and 19% respectively.

Some universities are already estimating the cost of attendance for the 2024-2025 academic year to be nearly $100,000.

Watch CBS News

What's behind the sky-high cost of a college education — and are there any solutions?

By Kathryn Watson

Updated on: November 5, 2022 / 12:41 PM EDT / CBS News

The Biden administration's announcement that up to $20,000 in student loan debt will be canceled for borrowers will bring welcome relief to millions, as long as courts allow . But that relief won't do anything to slow the rapidly rising cost of going to college.

In the 1963-1964 academic year, the average annual published cost of in-state tuition and fees was $243 at public four-year institutions, and $1,011 at private four-year institutions, according to National Center for Education Statistics data . That excludes room and board.

If the published cost of college remained in line with inflation, annual tuition and fees would have been $2,076 at four-year public universities and $8,624 at private institutions for the 2020-2021 academic year, according to the National Center for Education Statistics' data in constant dollars, or income adjusted for inflation.

But in the 2020-2021 academic year, the average price tag for in-state tuition and fees at a four-year public institution was $9,375, and at private four-year institutions, it was a whopping $32,825. With student housing, that cost skyrockets — some schools are charging those who can afford it over $70,000 per year .

Why is college so expensive?

"There's no one single answer," says Beth Akers, author of "Making College Pay" and a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. "You can ask lots of different people and they have lots of different reasons."

However, the sticker price an institution lists on its website and the net price can be pretty far apart, said Phillip Levine, an economist at Wellesley College. The net price is what students pay after needs-based aid and merit scholarships. The net price has increased at a faster rate at public institutions, where state funding hasn't kept pace with the increase in price.

The government doesn't track the net price students pay at public vs. private institutions. But according to the College Board, students on average receive more financial aid at private institutions. And the net price families paid at private colleges for tuition, room and board was about $33,720 at private institutions, compared with $19,230 at public colleges for the 2021-2022 academic year.

In the last two decades, the published price of tuition and fees at private four-year institutions has increased much more rapidly than the net tuition. Over the last 20 years, their sticker prices have gone up 54% in inflation-adjusted dollars, even though net tuition prices — what students are paying after factoring in grants and scholarships — have gone up just 7%, according to College Board and National Center for Education Statistics data analyzed by the Manhattan Institute.

For many public institutions that have been seeing decreases in state funding, the financial picture is worse. The published price for tuition and fees has increased 102% at public four-year institutions, adjusted for inflation, with net tuition and fees at public four-year schools running 115% higher in the last 20 years.

"A lot of times we overestimate the rising cost of college," Levine said. "Because mostly what we do is focus on the sticker price.

But the vast majority of students don't pay the sticker price at public or private schools, he said.

Public institutions have "shifted away from funding through taxpayer support and toward collecting revenue through individual tuition charges," said Akers.

Students from upper-middle class and affluent families who often comprise the governing and media classes are the ones paying full price, Levine noted.

"The discrepancy is that's the price that high-income families have to pay," Levine said.

Administrative costs and facilities

The number of administrative staff added at higher education institutions has outpaced the hiring of teaching faculty in recent decades.

The number of administrators at higher education institutions grew twice as fast in the 25 years ending in 2012 as the number of students did, the New England Center for Investigative Reporting found by analyzing federal data.

And from 2010 to 2018, spending on student services increased 29% and spending on administrative functions increased 19%, while spending on instruction only grew 17%, according to a 2021 report from the American Council on Trustees and Alumni.

Colleges and universities have become more comprehensive in the services that they offer, and in general, students are reaping the benefits, said Janet Napolitano , the former Arizona governor and former secretary of the Department of Homeland Security who was president of the University of California system for seven years.

"I never had students come to me and say, we need fewer Title IX officers, or we need to reduce mental health services or we need to reduce the number of people who help in the financial aid office," said Napolitano, who is now the director of the Center for Security in Politics at the University of California, Berkeley.

"The point being is that over time, as universities have absorbed the cost of providing not just the academic teaching and research aspect of a college education but all the kind of adjunct or associated services that go along with it, that, too, has I think added to the cost."

But administrative spending doesn't account for most of the increase in the sticker price of college, Akers said.

Then, there are the headlines about luxury amenities for students, like lazy rivers at Texas Tech University, or climbing walls at the University of Maryland. But those additions are also facile targets, and still don't come close to explaining the increase in the sticker price for college, Akers said.

Market forces

Higher education is competitive — Harvard and Princeton will always be competing for the same very select pool of the nation's most promising students.

"It's also the case that in some ways higher education doesn't look like a normal market," Levine said.

In a normal market, everyone pays the same price. "Everyone doesn't pay the same price in higher education," Levine said. At many schools, those who can afford less pay less, and at a handful of the nation's most elite schools, including Harvard, Yale and Stanford, students who are accepted and whose family income is under around $60,000 get a free ride .

That lack of price transparency in what the net price will be for a prospective student is aso something that distorts the market, Levine noted, since most college applicants don't know what they'll actually pay until after they're accepted, commit to a university and apply for aid.

Levine created a tool, MyinTuition , through which students can estimate their net tuition cost based on factors like how much their family has in savings and investments, their GPA and their SAT scores. He built the tool when he was trying to figure out how much he would pay for his own kids' college education.

But his website doesn't include the majority of higher education institutions, and the calculator is just an estimate, and isn't binding.

Student loans

Then there are student loans.

"People claim all the time the fact that we've allowed people to borrow so much is driving up the price, and I think there's some truth in that," Akers said.

"It's not really a basic economic argument that the availability of loans has driven up the price, but I think it's more of a behavioral thing."

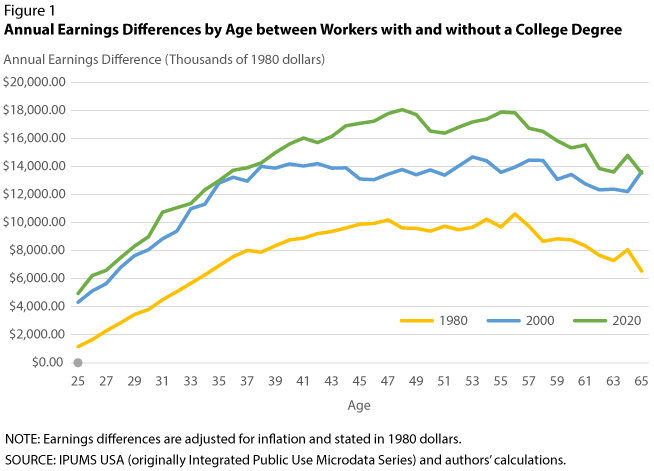

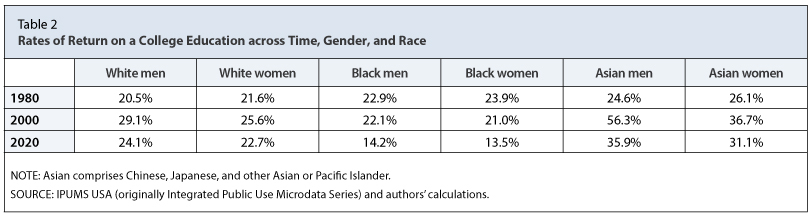

Millions of Americans will continue to attend college and take on mountains of debt to do so because the financial — and even social — benefits of attending college still generally outweigh the financial cost, Akers and Levine each noted.

"The returns to graduating from college are significant," Levine said. "And simple calculations basically will indicate that for the typical student, attending college definitely pays off relative to its cost."

But "that doesn't mean it pays off for everybody," Levine added.

Men with bachelor's degrees earn about $900,000 more in median lifetime earnings than their high school graduate counterparts, according to Social Security Administration data . Women with bachelor's degrees earn $630,000 more during their lifetimes than women with only a high school diploma.

And a 2021 study from Georgetown University found high school graduates make a median of $1.6 million during their lifetimes, compared to $2.8 million for those with bachelor's degrees.

So, over the span of a lifetime, spending say $100,000 for a college education with those returns is a relative "bargain," Akers said.

Millions will continue to pay more and more for college, so long as the benefit generally outweighs the cost. But at some point, "the market forces will continue to drive up the price until it's no longer worth it," Akers said.

Napolitano is skeptical of the Republican argument that universities will use the Biden administration student loan forgiveness as an opportunity to significantly ratchet up prices.

"I think any college president who relies on the assumption that loans in the future will be canceled is living in a fairy land," she said.

Are there any solutions?

Akers said the solution to addressing the ever-increasing cost of college is the opposite of the student loan cancellation the Biden administration is undertaking.

That said, "I don't want to eliminate subsidies," said Akers. "I don't want to eliminate the student loan program."

But graduates who can afford to pay back loans should be required to do so, she said.

One avenue to reducing costs would be cutting the time it takes to obtain a college degree. If students are able to receive college credit for coursework while they're still in high school or even middle school, that would shorten the time they're paying for four-year colleges. Napolitano, for instance, thinks state governments should further incentivize students to attend community college, to attend far less expensive community colleges, both while they're still in high school and after, so they can transfer those credits to a four-year institution.

There also should be more pathways to securing good, well-paying jobs, Akers said, adding she thinks there's "going to be kind of a natural correction," with more employers dropping requirements for college degrees. Some companies have already begun to do that in today's tight labor market. Apprenticeship programs and trades should be celebrated, she argued, saying that political and social leaders need to celebrate those pathways, too.

- Student Loan

Kathryn Watson is a politics reporter for CBS News Digital based in Washington, D.C.

More from CBS News

6 risks to consider before tapping into your home's equity

Does Medicare cover long-term care costs?

Protests continue at college campuses as graduation approaches

Searches on Americans in FBI foreign intelligence database fell in 2023

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Estimate your college cost

Online tools and calculators can help you estimate how much a specific college will cost. Knowing that helps you compare schools more accurately and choose the best one for you.

Know what college costs include

Start by understanding what is included in the total cost of college . Look at the costs for the specific schools you are considering and identify:

- Other expenses to plan for

- Ways to cut costs

- How to compare costs of colleges

Use tools to help you find schools

These tools from the Department of Education can help you find the best colleges for your budget.

- College Navigator - Search schools for those that meet your academic and financial needs.

- College Scorecard - Compare schools by price, field of study, and other criteria.

- Net Price Calculator Center - Learn the estimated price you will pay to attend a certain school. It factors in scholarships and grants the school might award you.

List the schools you are interested in on your Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) . The schools will be notified and may make financial aid offers.

Calculate costs after receiving financial aid offers

Once you receive a financial aid offer, learn how to calculate the school's actual net cost to you. This is the amount you will pay, minus financial aid and any savings you have for your education.

If you get more than one offer, compare them using Your Financial Path to Graduation . This tool from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau helps you understand each offer. It shows how much in costs you will have to cover, and if you can afford the school.

Get more tips to help with the new responsibilities of adulthood.

Transitioning to adulthood

LAST UPDATED: February 27, 2024

Have a question?

Ask a real person any government-related question for free. They will get you the answer or let you know where to find it.

Sorry, we did not find any matching results.

We frequently add data and we're interested in what would be useful to people. If you have a specific recommendation, you can reach us at [email protected] .

We are in the process of adding data at the state and local level. Sign up on our mailing list here to be the first to know when it is available.

Search tips:

• Check your spelling

• Try other search terms

• Use fewer words

College tuition has increased — but what’s the actual cost?

More and more Americans are going to college as tuition increases. But what’s the actual cost of higher education? Here’s an analysis of how colleges finances work and how tuition factors in.

Updated on Tue, October 3, 2023 by the USAFacts Team

More and more Americans are going to college. According to data from the Department of Education National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), in 1980, 50% of high school graduates between the ages of 16 and 24 were enrolled in college; in 2016, it was 70%. In 2016, 19.3 million undergraduate students were enrolled in higher education institutions. 70% were enrolled at public schools, 23% at private non-profits schools and 7% at private for-profit schools. The cost of going to college has also changed since 1980 — however, how much it has changed depends on whether you look at the “sticker price” or the net price after financial aid.

Tuition is an increasingly important revenue source

After adjusting for inflation, the average undergraduate tuition, fees, room and board has more than doubled since 1964, from $10,040 to $23,835 in 2018. Tuition has recently grown the fastest at public and private non-profit institutions, for which tuition has gone up 65% and 50%, respectively, since 2000. Tuition at private for-profit institutions has only increased 11%. However, as we describe below, the sticker price (our term for full tuition without aid) only reflects what one shrinking group of students pays for college.

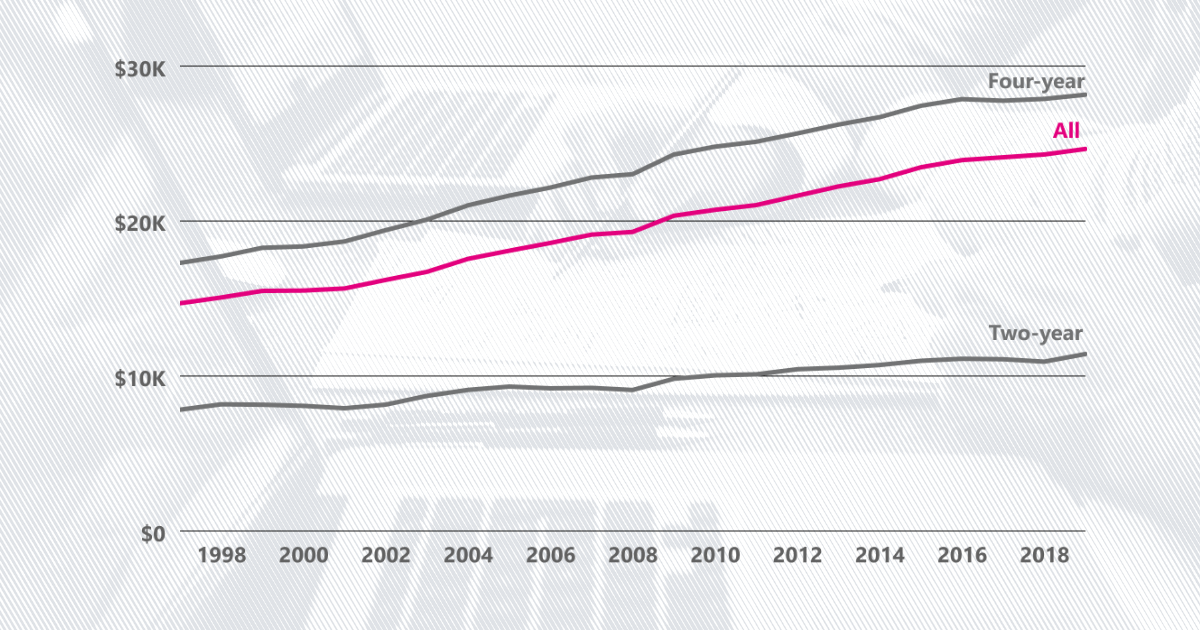

Average undergraduate tuition, fees, room and board Constant 2017-18 dollars

As tuition has increased, the revenue makeup for many institutions has also shifted, with government funding making up a smaller proportion of revenue for schools, and tuition payments making up a larger proportion. At public institutions, state, local and private funding has decreased from making up 50% of revenue in 1981 to 29% in 2016. It’s not just public schools experiencing a shift in funding sources. Private institutions, which have historically relied on tuition and fees even more than public institutions, have also seen federal funding drop from 19% of revenue to 13%. Tuition payments are making up a larger proportion of their revenue as a result. University-affiliated hospitals are also increasingly important revenue streams for public and private schools, as well as a growing component of institution expenditures.

Average undergraduate tuition, fees, room and board (Constant 2017-18 dollars, by institution type)

Non-profit Institutions

Average undergraduate tuition, fees, room and board (Constant 2017-18 dollars, by institution level)

Two-year Institutions

Despite these shifts in revenues, colleges have not really altered how they spend money. Public schools spend heavily on instruction and student services, with expenditures shifting slightly from instruction to student services during the last 30 years. Both private non-profit and for-profit institutions also spent most of their revenue in these areas, though non-profits have shifted more dollars away from student services and more toward “Other” spending (a miscellaneous category that contains expenses that don’t fit in other categories, such as an early retirement program for faculty and staff ), while for-profit institutions have shifted dollars toward student services.

However, expenditures can vary greatly by institution. For example, top research universities may spend a much larger proportion of expenditures on research—for example, University of California Berkeley spends 26% of expenditures on research—whereas many post-secondary institutions, such as Berkeley City College, may spend nothing on research.

Institution revenues (Public institutions)

Auxiliary enterprises in the United States

$27,581,335,730

Institution revenues (Private non-profit institutions)

Investment income gains (losses) in the United States

-$2,736,521,305

Institution revenues (Private for-profit institutions)

Student tuition and fees in the United States

$14,429,842,000

Sticker v.s. net price

While the sticker price of college is increasing, fewer students are paying the full price due to grant aid. For example, while the average tuition at public institutions in 2016 was $17,459, the average tuition revenue institutions received on average per full-time student was only $7,547.

Federal grants are the most common type of aid students receive — about two in five students at public and non-profit schools receive some form of federal grant aid compared to two-thirds of students at for-profit schools. There are four major types of federal grants , the largest of which is the Pell Grant program, which is available for students for whom the difference between cost of attendance and the expected family contribution exceeds a certain amount (roughly $600 for full-time students according to information provided in a student’s FAFSA ( IFAP )).

Across almost all categories and school types, more students are awarded grant aid to pay for school, meaning fewer students are paying the list price. In 2000, 44.4% of all undergraduates received grant aid, whereas in 2016, that number increased to 63.1%.

Institution expenditures (Public institutions)

Instruction in the United States

$108,162,492,300

Institution expenditures (Private non-profit institutions)

Student services, academic and institutional support in the United States

$32,937,346,000

Institution expenditures (Private for-profit institutions)

$9,198,033,000

Note: These categories are not mutually exclusive — many students receive multiple types of aid. The population covered in this table is first-time, full-time students at degree-granting institutions.

The average amount of grant aid has also increased, but few types of grant aid have increased at the same rate as tuition, which has increased 53% since 2001.

While federal grants are the most common form of aid, the largest forms of aid from a monetary standpoint, are institutional grants and scholarships. The average amount of federal aid received per student receiving aid ranged between $4,453 and $5,208 per school year.

Percent of full-time, first-time undergraduate students awarded grant aid (Public)

Percent of full-time, first-time undergraduate students awarded grant aid (private non-profit), percent of full-time, first-time undergraduate students awarded grant aid (private for-profit).

So, what does this mean most students end up paying? For the roughly 55% of students receiving any form of federal aid—including federal grants, loans, or work-study aid — the average annual net price of the school, or the sticker price minus any government or institutional grants and scholarships, was $16,147 in the 2016-17 school year.

This average net price varies based both by the student’s family income and by the type of school. A family earning $30,000 per year may on average pay $9,510 per year for their child to attend a four-year public institution (48% of the average sticker price). Enrolling in a four-year, private non-profit institution would cost $20,150 per year, or 44% of the average private non-profit sticker price.

Note: Net price data is for students receiving some form of federal aid—including federal grants, loans, or work-study aid. For this reason, data for students from higher-income families is more limited and may not be representative.

When looking at students receiving any form of federal aid, the net price of college has not dramatically changed since 2010. While the sticker price average for four-year institutions has increased 12.4% since 2010, the net price has only increased 1.7%. For two-year institutions, the sticker price increased 10.8%, whereas the net price decreased 5.6%. The percent of students receiving any form of federal aid has also increased from 36.6% in 2001 to 55.9% in 2016. This appears to be part of a larger trend of federal funding shifting from operating grants and non-operating appropriations to non-operating grants, which includes grant aid to students like Pell Grants.

Note: Net price data is for students receiving some form of federal aid—including federal grants, loans, or work-study aid.

However, not all students who need financial help qualify for federal aid and increasing sticker prices are still felt by many students. In 2017, while 56% students received federal aid, 83% of students received either government or institution grants or student loans (excluding Parent PLUS loans). For many students, what’s left over after grant aid — if they even receive grant aid — requires student loans.

Learn more about education in the US and get the data directly in your inbox by signing up for our newsletter.

Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Digest of Education Statistics

Department of Education, College Scorecard

Department of Education, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System

Explore more of USAFacts

Related articles, which states have the highest and lowest adult literacy rates.

Virtual school, mask mandates and lost learning: COVID-19's impact on K-12 schools

The price of college is rising faster than wages for people with degrees

How often do teacher strikes happen?

Related Data

Inflation-adjusted median annual earnings of full-time workers aged 25-34

Average Pell Grant award

Pell Grant applicants

15.59 million

Data delivered to your inbox

Keep up with the latest data and most popular content.

SIGN UP FOR THE NEWSLETTER

Compare Schools and Fields of Study

Schools (0), fields of study (0), average annual cost more information.

Cost includes tuition, living costs, books and supplies, and fees minus the average grants and scholarships for federal financial aid recipients.

Graduation Rate More Information

Median earnings more information.

The median earnings of former students who received federal financial aid at 10 years after entering the school.

Salary After Completing

Monthly earnings more information, financial aid, median total debt after graduation more information, monthly loan payment more information, number of graduates more information, no schools selected to compare., no fields of study selected to compare., start your fafsa® application.

To receive financial aid, you must complete the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA®) form. Use Federal Student Aid Estimator to see how much aid may be available to you.

Other Sources

Don't forget: Do fill out the FAFSA® form, but also look into other programs such as GI Bill Benefits

Why Has the Cost of Education Skyrocketed?

Author: Mayuri Hebbar, Graphics: Bella Aharonian

The BRB Bottomline:

Are you planning on going to college but worried about the cost? The cost of education has increased significantly in the past couple of decades. Continue reading to learn more about this increase as well as ways to mitigate the potential future financial burden of attending college.

Exploring the Cost of Education

Introduction.

In the United States, attending college is usually perceived as a huge financial burden. But was college always this expensive? Not really. In fact, since 1980, the average cost of college tuition has increased by 1200% . What happened? In the past couple of decades, education has transformed into more of a profit-maximizing industry, and society has placed more cultural emphasis on attending college.

Education Historically

Historically, education was primarily only accessible to wealthy, white men . This problematic restriction systematically furthered the cycle of poverty by requiring applicants of higher-paying jobs to have a college degree—thus effectively barring non-white, non-male members of the workforce from pursuing high-powered, high-paying careers. As a result, members of minority groups were largely held back in a perpetual cycle of poverty and restriction to higher education. Today, social progress has resulted in a drastic reduction of race, age, and gender, negatively impacting access to higher education.

Education in the United States Versus Other Countries

As expected, developing nations sink less money into further education than does the United States. In contrast to America, gender inequality in education still creates major setbacks for female students in areas of poverty and “geographic remoteness.” This inequality is largely driven by fundamental issues, such as a lack of public transport to educational institutions or dangerous travel conditions, which makes parents less willing to send their daughters to school due to safety concerns. Therefore, without the prerequisite primary and secondary education, many girls in these nations cannot attend college, driving down the demand and thereby the market price of further education.

However, more developed countries also spend less on higher education compared to the United States— countries that have consistently outperformed the U.S. in terms of literacy rates and other metrics. The U.S. spends more on education at the post-secondary level than does any other country. In fact, the U.S. spends approximately $30,000 per student, while the average spending across other countries, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), was just over half of that, at $16,100 per student . This seemingly counterintuitive disparity can be explained by the fact that individuals in other countries are able to more easily access education—and therefore, those countries outrank the U.S. in education-related metrics.

So why does the United States relegate itself to a counterproductive system of pricing up its college tuition? There are a number of factors at play in the U.S. that have resulted in a high cost of education. The $30,000 that students spend on average for post-secondary education includes any publicly-funded loans or grants that the student receives. Additionally, students are more likely to attend college away from home , and the added living expenses increase the total cost of going to college. Tuition for out-of-state and private colleges is more expensive than in-state tuition, so selecting out-of-state or private colleges can also raise the cost of education.

In other countries, there are substantial government initiatives that help subsidize the costs of education. Likewise, the U.S. government offers financial aid through the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) program. However, FAFSA provides less relief from hefty college tuition compared to analogous programs in other countries. There are a few reasons for this discrepancy . Firstly, the size of loans given out is not enough to fully cover the cost of education. On top of that, complex paperwork that needs to be accurately filled out in order to be considered for a loan makes financial aid harder to receive. Lastly, most colleges do not offer financial aid or accept FAFSA for international students. With all of these factors being considered, there are not enough financial support resources within the U.S. to meet the increasing demand for higher education, and as a result, the price of education continues to skyrocket and become increasingly unaffordable for many students.

Why is the Cost of Education so High?

The cost of higher education has increased by over 100% in the last 20 years—a much higher rate compared to most other industries. This increase in the cost of tuition is paralleled by the increasingly widespread mentality that you need a college education in order to earn a good living. While this may generally be true across many industries, a college education does not reap the same value for every individual. The cost of education is not always proportional to income earned after graduation; this ratio differs across different majors, professions, colleges, and individual circumstances at the end of the day. So while a college education may pave the way to more opportunities—generally speaking, it is not the end-all-be-all answer to success. In more recent years, most students see college as the final destination after high school; therefore, families are willing to pay a premium, and students are willing to take out loans and work multiple jobs to afford an education. This mentality contributes to more and more students seeking out a college education, increasing the demand for a college degree, which thereby raises the price of college since educational systems are aware that families are willing to pay such high prices for a college education.

Preparing to Pay for College

College is expensive, which is why if college is on a student’s radar, they can work with their families or caregivers to come up with a plan that would reduce potential financial burden. For example, there are different savings plans , including mutual funds , Roth IRAs, and 529 plans, that can be set up before a student heads off to college. There are pros and cons associated with each, but in general, most of these different accounts are tax-sheltered, which means that money can be deposited into the account without being taxed and will grow until the student needs that money to pay for college.

The 529 savings plan is one of the most popular forms of savings accounts for college as it offers tax benefits if the money is used specifically for college. Additionally, all money earned from interest rates is completely tax-free and is not taxable upon withdrawal to use to pay for college expenses. There are different sub-plans within the 529 savings plan, which have high maximum amount limits for the account and also allow for larger deposits. Investing early into these types of savings accounts is really beneficial as it allows money to grow over time, making paying for college a lot less stressful.

Additionally, much of the U.S. population is made up of the middle-class, who make enough money to not receive financial aid but still cannot comfortably pay for college, especially when multiple children in a household are going to college at the same time. From a policy standpoint, increasing aid and scholarship opens more opportunities for middle-class families since oftentimes their financial struggles are overlooked. Offering loans, grants, and scholarships specifically geared towards middle-class families could help to somewhat subsidize the cost of education for these families, making higher education a more attainable reality. In doing so, the government is also playing a part in actively giving these students the chance to achieve financial independence and move higher up in the socioeconomic ladder . An increasing demand for a college education doesn’t have to correspond to unsustainable costs. There are measures in both the form of personal investments and government policy that can be taken to help mitigate the cost for those interested in going to college.

So the question remains: what can the student from an average household do to help alleviate the financial burden of college tuition? Students need to ask themselves if college is even right for them and figure out why they even want to go to college in the first place. Will a college degree facilitate the process of getting them to their dream career, or are they going to college simply because everyone else is and they do not know what better to do with their time? This question cannot be answered easily until students are one or two years away, but that does not mean that families need to wait until that point to start saving for college. Good financial planning always accounts for the “financially worst case” situation, which in this context would mean needing to pay for college. Therefore, planning for college should start much sooner, preferably as early as possible. Investing a little bit every year into a college savings plan, like a 529 savings plan, will help alleviate the burden of paying for college if the student decides to attend in the future.

Take-Home Points

- In the United States, attending college is usually perceived as a huge financial burden. The average cost of college education has drastically increased in recent years, but it wasn’t always this expensive.

- Historical gender and racial barriers to education have furthered the cycle of poverty, resulting in minimal access to minority groups pursuing high-powered, high-paying careers.

- In developing countries, there is a lesser demand for higher education which results in lower prices for higher education in comparison to the U.S.

- Less developed foreign countries spend less on education, which makes it more accessible for students.

- American students are more likely to attend college away from home, which results in more expenses.

- FAFSA provides less relief than in analogous foreign countries for several reasons.

- The cost of education is also so high due to the mentality that you need a good education to have a successful and high-paying career.

- There are several ways to pay for college such as Roth IRAs, 529 savings plans, and mutual funds.

- While going to college is expensive, with careful financial planning, the burden can ultimately be mitigated.

Great article. I like how you mentioned the systems of higher education in other countries, comparing them to the US’s. I also appreciate how you made this article more than just informative by incorporating a section on how people can prepare for the financial burden of college.

The article covered a lot of important information. I appreciated the historical perspective of the rising cost to attend college. The financial advice portion was super insightful and could be very useful for many families.

Interesting article. I think the comparison between the cost of higher education in the US and other developed countries is poignant.

I found it interesting that “developed” nations are spending less on higher education than the U.S. I don’t think a lot of people would expect that. I don’t know how far the U.S. is from catching up to other developed countries when it comes to education, but it does beg the question, “Where is all the money going?” Thank you for answering!

Applying a global comparison to modern day US higher education spending helps restore perspective on where the US and its future generations is headed relative to other countries. An interesting read and important points on the increased financial burden college makes.

There is an additional hidden cost to individuals and society as a whole. Reportedly, 40% of those who go to college never get a degree, yet are still on the hook for their loans. Often, the student was “sold a bill of goods,” so to speak, by the intense sales job colleges and high school guidance counselors subject then to. But after deciding to drop out, the student is often blamed, whereas the college not only denies any responsibility, but adds insult to injury by refusing to help in any way. The student is burdened and disempowered by the college and society as a whole. Millions of people suffer for years while national productivity is diminished and the imbalance of wealth is exacerbated.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

We are a student group acting independently of the University of California. All information on this website is published in good faith and for general information purposes only. Business Review at Berkeley does not make any warranties about the completeness, reliability and/or accuracy of this information. The Editorials section features views of the individual authors and do not reflect the position of our organization as a whole or of the greater UC Berkeley community. No article or portion of an article should be construed as providing financial, legal, or political advice. Any action you take upon the information you find on this website is strictly at your own risk. Business Review at Berkeley will not be liable for any losses and/or damages in connection with the use of our website.

Designed using Unos Premium . Powered by WordPress .

- MAIN NAVIGATION

- All Schools & Programs

- Graduate Programs

- Online Degrees

- Community Colleges

- Career Schools

- Law Schools

- Medical Schools

- Comparison Home

- Quick Comparison

- Best Colleges

- Rivalry Schools

- College by SAT/ACT

- 2024 Core Stats

- Tuition Trends

- Area of Study

- Career Programs

2024 Average College Tuition By State

2024 tuition and living costs summary by states.

State Having Highest Tuition

State having lowest tuition, state having highest graduate tuition, state having lowest graduate tuition.

- University of Phoenix-Arizona Private, four-years | Phoenix, AZ

- CUNY John Jay College of Criminal Justice Public, four-years | New York, NY

- Grand Canyon University Private, four-years | Phoenix, AZ

- Harvard University Private, four-years | Cambridge, MA

- University of Massachusetts-Amherst Public, four-years | Amherst, MA

- University of Wisconsin-Madison Public, four-years | Madison, WI

- University of Florida Public, four-years | Gainesville, FL

- Alaska Bible College Private, four-years | Palmer, AK

- University of Georgia Public, four-years | Athens, GA

- California Polytechnic State University-San Luis Obispo Public, four-years | San Luis Obispo, CA

- Bethany Global University Private, four-years | Bloomington, MN

- George Washington University Private, four-years | Washington, DC

- Walden University Private, four-years | Minneapolis, MN

- Saint Cloud State University Public, four-years | Saint Cloud, MN

- National University Private, four-years | San Diego, CA

- Bethel University Private, four-years | Saint Paul, MN

- St Catherine University Private, four-years | Saint Paul, MN

- University of Central Florida Public, four-years | Orlando, FL

- Saint Leo University Private, four-years | Saint Leo, FL

- Utah Valley University Public, four-years | Orem, UT

- Ashford University Private, four-years | San Diego, CA

- Minnesota North College Public, 2-4 years | Hibbing, MN

- Normandale Community College Public, 2-4 years | Bloomington, MN

- Capella University Private, four-years | Minneapolis, MN

- Rasmussen University-Minnesota Private, four-years | St. Cloud, MN

- Howard University Private, four-years | Washington, DC

- University of Minnesota-Twin Cities Public, four-years | Minneapolis, MN

- Crown College Private, four-years | Saint Bonifacius, MN

- City College-Hollywood Private, 2-4 years | Hollywood, FL

- Carrington College-Mesa Private, 2-4 years | Mesa, AZ

- Cochise County Community College District Public, 2-4 years | Sierra Vista, AZ

- Pima Medical Institute-Albuquerque Private, 2-4 years | Albuquerque, NM

- ATA Career Education Private, 2-4 years | Spring Hill, FL

- Stautzenberger College-Brecksville Private, 2-4 years | Brecksville, OH

- Carrington College-Tucson Private, 2-4 years | Tucson, AZ

- Ivy Tech Community College Public, 2-4 years | Indianapolis, IN

- Houston Community College Public, 2-4 years | Houston, TX

- Summit Academy Opportunities Industrialization Center Private, Less than 2-years | Minneapolis, MN

- Aveda Arts & Sciences Institute Minneapolis Private, Less than 2-years | Minneapolis, MN

- Careers Institute of America Private, Less than 2-years | Dallas, TX

- Coastline Beauty College Private, Less than 2-years | Fountain Valley, CA

- Cosmetology Careers Unlimited College of Hair Skin and Nails Private, Less than 2-years | Duluth, MN

- Evergreen Beauty and Barber College-Everett Private, Less than 2-years | Everett, WA

- Advance Beauty College Private, Less than 2-years | Garden Grove, CA

- Paul Mitchell the School-Milwaukee Private, Less than 2-years | Wauwatosa, WI

- Davis Technical College Public, Less than 2-years | Kaysville, UT

- Champion Beauty College Private, Less than 2-years | Houston, TX

Higher education accountability: Measuring costs, benefits, and financial value

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, katharine meyer katharine meyer fellow - governance studies , brown center on education policy @katharinemeyer.

March 14, 2023

- 15 min read

Higher education has long been a vehicle for economic mobility and the primary center for workforce skill development. But alongside the recognition of the many individual and societal benefits from postsecondary education has been a growing focus on the individual and societal costs of financing higher education. In light of national conversations about growing student loan debt and repayment, there have been growing calls for improved higher education accountability and interrogating the value of different higher education programs.

The U.S. Department of Education recently requested feedback on a policy proposal to create a list of “low-financial-value” higher education programs. The Department hopes the list will highlight programs that do not provide substantial financial benefits to students relative to the costs incurred, in hopes of (1) steering students away from those programs and (2) applying pressure on institutions on the list to improve the value of those programs—either on the cost or the benefit side. Drawing on my comments to the Department, in this piece, I outline the key considerations when measuring the value of a college education, the implications of those decisions on what programs the list will flag, and how the Department’s efforts can be more effective at achieving its goals.

Why create a list of low-financial-value programs?

Ultimately, whether college will “pay off” is highly individualized, dependent on students’ earnings potential absent education, how they fund the education, and some combination of effort and luck that will determine their post-completion employment. What value does a federal list of “low-financial-value” programs provide students beyond their own knowledge of these factors?

First, it is challenging for students to evaluate the cost of college given that the “sticker price” costs colleges list rarely reflect the “net price” most students actually pay after accounting for financial aid. Many higher education institutions employ a “ high cost, high aid ” model that results in students paying wildly different prices for the same education. Colleges are supposed to provide “net price calculators” on their websites to help students estimate their actual expenses, but a recent report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office found only 59% of colleges provide any net price estimate, and only 9% of colleges were accurate ly estimating net price. When students do not have accurate estimates of costs, they are vulnerable to making suboptimal enrollment decisions.

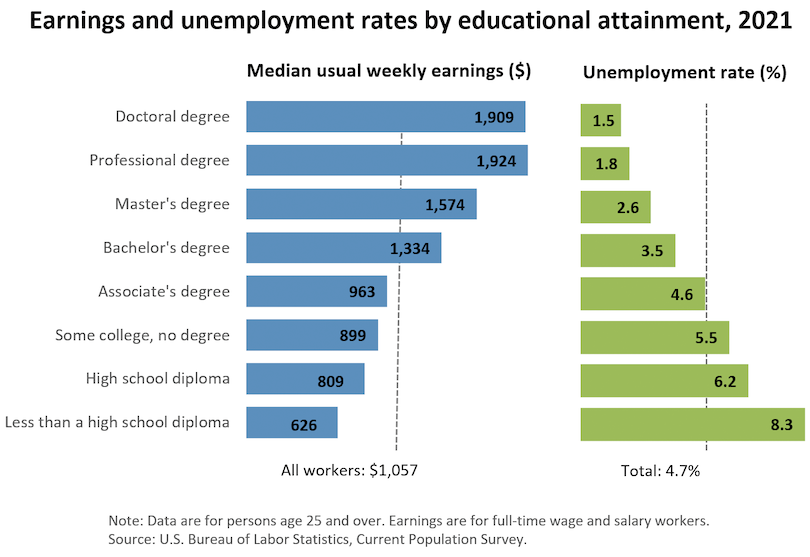

Second, it is difficult for students to estimate the benefits of postsecondary education. While on average individuals earn more as they accrue more education—with associate degree holders earning $7,800 more each year than those with a high school diploma and bachelor’s degree holders earning $21,200 more each year than those with an associate degree—that return varies substantially across fields of study within each level of education and across institutions within those fields of study. Yet students rarely have access to this program-specific information when making their enrollment decisions.

The Department has focused on developing a list of “low-financial-value” programs from an individual, monetary perspective. But it is important to note there are non-financial costs and benefits to society, as well as to individuals. There are many careers that have high value to society, but that do not typically have high wages. Higher education institutions cannot control the local labor market, and there is a risk that in response to the proposed list, institutions would simply cut “low-financial-value” programs, worsening labor shortages in some key professions. For example, wages are notoriously low in the early education sector, where labor shortages and high turnover rates have significant negative effects on student outcomes. Flagging postsecondary programs that result in slightly higher wages for their childcare graduates is less productive than policy efforts to ensure adequate pay to attract and retain those workers into this crucial profession.

HOW TO MEASURE the value of a college education?

This is not the first time the Department has proposed holding programs accountable for their graduates’ employment outcomes. The most analogous effort has been the measurement of “ gainful employment ” (GE) for career programs. As the Biden administration prepares to release a new gainful employment rule in spring 2023, elements of that effort offer a starting point for the current accountability initiative. Specifically, the proposed GE rules of using both the previously calculated debt-to-earnings ratio and setting a new “ high school equivalent ” benchmark for outcomes provide a framework for evaluating the broader set of programs and credential levels proposed under the “low-financial-value” effort.

Setting Benefits Benchmarks

The primary financial benefits of a postsecondary education are greater employment stability and higher wages. The U.S. Census Post-Secondary Employment O utcomes (PSEO) data works in partnership with states to measure both outcomes, though wage data only includes those earning above a “ minimum wage ” threshold and coverage varies across states . With those caveats, I use PSEO to examine outcomes for programs in the four states reporting data for more than 75% of graduates (Indiana, Montana, Texas, and Virginia, limiting analysis to programs with at least 40 graduates). The Department is deliberating on which benchmark to measure outcomes against, and here I examine how programs would stack up against two potential wage benefits benchmarks: 1) earning more than 225% of the federal poverty rate ( $28,710, which is similar to a $25,000 benchmark frequently proposed ); and 2) earning more than the average high school graduate ( $36,600 ). These benchmarks are compared against the median reported earnings of a program’s median graduate; those where the median graduate’s earnings fail to meet the benchmark are at risk of being labeled a “low-financial-value” program.

Many certificate programs produce low wages