Advertisement

Criminological Research and the Death Penalty: Has Research by Criminologists Impacted Capital Punishment Practices?

- Published: 16 April 2019

- Volume 44 , pages 536–580, ( 2019 )

Cite this article

- Gordon P. Waldo 1 &

- Wesley Myers 1

2365 Accesses

4 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

At the request of the SCJA president this paper addresses five questions. Does criminological research make a difference relative to the death penalty? - If criminological research does make a difference, what is the nature of that difference? - What specific instances can one cite of research findings influencing death penalty policy decisions? Why hasn’t our research made more of a difference? What can we do, either in terms of directing our research or in terms of disseminating it, to facilitate it making a difference? Specific examples of research directly impacting policy are examined. The evidence presented suggests that research on capital punishment has had some impact on policy, but not nearly enough. There is still a high level of ignorance that has limited the impact of criminological research on death penalty policy. The proposed solution is to improve the education of the general public and decision makers in order to increase the impact of criminological research on capital punishment policy.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Should we Maintain or Break Confidentiality? The Choices Made by Social Researchers in the Context of Law Violation and Harm

The Impact of COVID-19 on Crime: a Systematic Review

The creation of the belmont report and its effect on ethical principles: a historical study.

One of the most interesting things the senior author learned in his first statistics class as an undergraduate, which became much clearer when he took his first graduate research methods class, was that if a correlation exists between two variables it does not automatically mean that one of the variables caused the other variable. This is true even if the one that appeared to be the cause (independent variable) met the first criteria for causation and occurred prior to the presumed effect (dependent variable). As he began to teach the first research methods course ever taught in the Criminology Program at Florida State University he also learned about extraneous variables, intervening variables, component variables, antecedent variables, suppressor variables, distorter variables, spurious non-correlations, conditional relationships, conjoint influence, etc. (Rosenberg, 1968 ). These different types of variables will not be discussed, but their existence has relevance in trying to answer the questions posed to the panelists. Instead, reference will be made to ‘direct’ and ‘indirect’ influences in this paper because each can be important in bringing about change.

Two other methods the courts have used in this regard is the number of states that have made a significant change in their death penalty statutes, such as the number of states changing the age for execution of juveniles (Thompson v. Oklahoma, 1988 ) . Another method the United States Supreme Court has used is international opinions. “It is proper that we acknowledge the overwhelming weight of international opinion …. The opinion of the world community, while not controlling our outcome, does provide respected and significant confirmation for our own conclusions” (Roper v. Simmons, 2005 p.11).

Warden describes the first exoneration as follows. “The first of what would become a cavalcade of post-Furman Illinois death row exonerations occurred in 1987 when a young prosecutor, Michael Falconer, came forward with exculpatory evidence that exonerated two condemned Chicagoans, Perry Cobb and Darby Tillis. It is hard to imagine more fortuitous or improbable events than those that led to the exonerations of Cobb and Tillis, who had been sentenced to death for a double murder that occurred a decade earlier.’ In 1983, the Illinois Supreme Court reversed and remanded their case because the trial judge had rejected a defense request to give the jury an accomplice instruction. The prosecution’s star witness, Phyllis Santini, had driven the getaway car used in the crime - admittedly but, she claimed, unwittingly. Chicago Lawyer , an investigative publication … carried a detailed article based on the Illinois Supreme Court opinion and case file. As luck would have it, Falconer, who recently had graduated from law school, read the article, which discussed Santini’s testimony in some depth. Years earlier, Falconer had worked with Santini at a factory and, as he would testify, she had told him that her boyfriend had committed a murder and that she and the boyfriend were working with police and prosecutors to pin it on someone else. “I thought to myself, ‘Jeez, there’s a name from the past,”‘Falconer reflected in a Chicago Lawyer interview. “I read on and started thinking, ‘Holy shit, this is terrible.”‘He called a defense lawyer mentioned in the article, reporting what Santini had told him. At an ensuing bench trial in 1987, Cobb and Tillis were acquitted by a directed verdict on the strength of Falconer’s testimony.” By then, Falconer was a prosecutor in a neighboring jurisdiction.” Cobb and Tillis eventually received gubernatorial pardons based on innocence. As serendipitous as the Cobb and Tillis exonerations” were, they were no more so than many that would follow. … (there were) 20 Illinois death row exonerations -each involving odds-defying fortuity. The error rate among 305 convictions under the 1977 Illinois capital punishment statute was in excess of 6% (Warden, 2012 p. 247–248).

Justice Marshall was careful to fully support his position surrounding the lack of a deterrent effect of the death penalty with two lengthy ‘laundry lists’ of research in the footnotes of his published opinion which are abbreviated here. “See, e. g., Jon Peck, The Deterrent Effect of Capital Punishment: Ehrlich and His Critics, 85 Yale L. J. 359 (1976); David Baldus & James Cole, A Comparison of the Work of Thorsten Sellin and Isaac Ehrlich on the Deterrent Effect of Capital Punishment, 85 Yale L. J. 170 (1975); William Bowers & Glenn Pierce, The Illusion of Deterrence in Isaac Ehrlich’s Research on Capital Punishment, 85 Yale L. J. 187 (1975); Issac Ehrlich. The Deterrent Effect of Capital Punishment: A Question of Life and Death, 65 Am. Econ. Rev. 397 (June 1975); Hook, The Death Sentence, in The Death Penalty in America 146 (Hugo Adam Bedau ed. 1967); Thurston Sellin, The Death Penalty, A Report for the Model Penal Code Project of the American Law Institute (1959).” And “See Passell & Taylor, The Deterrent Effect of Capital Punishment: Another View (unpublished Columbia University Discussion Paper 74–7509, Mar. 1975), reproduced in Brief for Petitioner App. E in Jurek v. Texas, O. T. 1975, No. 75–5844; Passell, The Deterrent Effect of the Death Penalty: A Statistical Test, 28 Stan. L. Rev. 61 (1975); Baldus & Cole, A Comparison of the Work of Thorsten Sellin & Isaac Ehrlich on the Deterrent Effect of Capital Punishment, 85 Yale L. J. 170 (1975); Bowers & Pierce, The Illusion of Deterrence in Isaac Ehrlich’s Research on Capital Punishment, 85 Yale L. J. 187 (1975); Peck, The Deterrent Effect of Capital Punishment: Ehrlich and His Critics, 85 Yale L. J. 359 (1976). See also Ehrlich, Deterrence: Evidence and Inference, 85 Yale L. J. 209 (1975); Ehrlich, Rejoinder, 85 Yale L. J. 368 (1976)… See also Bailey, Murder and Capital Punishment: Some Further Evidence, 45 Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 669 (1975); W. Bowers, Executions in America 121–163 (1974).”

This only happened once with a legislator who was in favor of the death penalty and opposed to abortion. I later learned from other lobbyist’s that he was known as a ‘weird duck’ and they tried to stay away from him. Fortunately, he is no longer in the legislature.

ABA. (1997). American Bar Association Policy 1997 MY 107: Death Penalty Moratorium Resolution . https://www.americanbar.org/groups/committees/death_penalty_representation/resources/dp-policy/moratorium-1997.html . Accessed 7 June 2018.

ABA. (2017). Amicus Curiae Briefs. https://www.americanbar.org/groups/committees/amicus.html . Accessed 30 Aug 2018.

ABA. (2018a). American Bar Association: Death Penalty due Process Review Project Report to the House of Delegates . https://www.americanbar.org/groups/committees/death_penalty_representation/resources/dp-policy/moratorium-1997.html . Accessed 7 June 2018.

ABA. (2018b, February 5). Ban death penalty for those 21 or younger . ABA Journal: ABA House says http://www.abajournal.com/news/article/Ban_death_penalty_for_those_21_or_younger_aba_house_says/ . Accessed 31 July 2018.

ACLU. (2016). Capital punishment. American Civil Liberties Union . https://www.aclu.org/issues/capital-punishment . Accessed 7 June 2018.

ALI. (1959, May 8). Model Penal Code: Tentative Draft No. 9. American Law Institute.

ALI. (2009). Report of the council to the membership of the American law institute on the matter of the death penalty. American Law Institute. https://www.ali.org/media/filer_public/3f/ae/3fae71f1-0b2b-4591-ae5c-5870ce5975c6/capital_punishment_web.pdf . Accessed 17 June 2018.

AMA. (n.d.). Capital Punishment: Code of Medical Ethics Opinion 9.7.3. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/capital-punishment . Accessed 8 June 2018.

Amnesty International. (n.d.). Death penalty. Amnesty International USA . https://www.amnestyusa.org/issues/death-penalty/ . Accessed 7 June 2018.

An Act Revising the Penalty for Capital Felonies (2012) Favorable Report of the Committee on Judiciary- 4/4/2012. , § Connecticut Senate, General Assembly.

APA. (2001, August). The Death Penalty in the United States. American Psychological Association. http://www.apa.org/about/policy/death-penalty.aspx . Accessed 7 June 2018.

APA. (2005). Roper v . Simmons: American Psychological Association http://www.apa.org/about/offices/ogc/amicus/roper.aspx . Accessed 22 August 2018.

Google Scholar

APA. (2018, May 1). APA amicus briefs by year. http://www.apa.org/about/offices/ogc/amicus/index-chron.aspx . Accessed 30 Aug 2018.

APA, American Psychiatric Association, (2018) National Association of Social Workers, & American Academy of Psychiatry and Law. Dassey v. Dittman. , No. 17–1172 (U.S. 2018). https://www.supremecourt.gov/DocketPDF/17/17-1172/39982/20180326134136295_Dassey%20v.%20Dittmann%2003.26.18%20Cert%20Stage%20Amicus%20Brief.pdf . Accessed 22 Aug 2018.

APHA. (1986, January 1). Abolition of the Death Penalty. American Public Health Association. https://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2014/07/14/13/50/abolition-of-the-death-penalty . Accessed 8 June 2018.

Applebome, P. (2012, April 11). Connecticut House Votes to Repeal Death Penalty. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/12/nyregion/connecticut-house-votes-to-repeal-death-penalty.html . Accessed 8 June 2018.

ASA. (2015). Amicus Briefs. http://www.asanet.org/amicus-briefs . Accessed 31 Aug 2018.

ASC. (1989). Historical policy positions: Official policy position of the American Society of Criminology with respect to the death penalty. American Society of Criminology . https://www.asc41.com/policies/policyPositions.html . Accessed 7 June 2018.

Atkins v. Virginia. (2002) 536 U.S. 304 (2002).

Ball, J. (2007, May). Illinois’ death penalty: Still too flawed to fix. Campaign to End the Death Penalty . http://www.nodeathpenalty.org/new_abolitionist/may-2007-issue-42/illinois%E2%80%99-death-penalty . Accessed 8 June 2018.

Banner, S. (2003). The death penalty: an American history (third printing.). Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Univ. press.

Bard, M., & Ellison, K. (1974). Crisis intervention and investigation of forcible rape. Police Chief, 41 (5), 68–73.

Barnhart, C. (Ed.). (1957). Ignorance. The American College Dictionary (p. 600). New York, N.Y: Random House.

Beck, J. C., & Shumsky, R. (1997). A comparison of retained and appointed counsel in cases of capital murder. Law and Human Behavior, 21 (5), 525–538.

Article Google Scholar

Bersoff, D. N. (1987). Social science data and the Supreme Court: Lockhart as a case in point. American Psychologist, 42 (1), 52–58.

Bersoff, D. N., & Ogden, D. W. (1987). In the Supreme Court of the United States Lockhart v. McCree: amicus curiae brief for the American Psychological Association. American Psychologist, 42 (1), 59–68.

Bienen, L. B. (2010). Capital punishment in Illinois in the aftermath of the Ryan commutations: Reforms, economic realities, and a new saliency for issues of cost. The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 100 (4), 1301–1402.

Black, C. L. (1974). Capital punishment: The inevitability of Caprice and Mistake. Norton.

Bohm, R. M. (2017). Deathquest: an introduction to the theory and practice of capital punishment in the United States (Fifth edition.). New York ; London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Bowers, W. J. (1983). The Pervasiveness of Arbitrariness and Discrimination under Post-"Furman" Capital Statutes. The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology (1973-), 74 (3), 1067.

Bye, R. T. (1926). Recent History and Present Status of Capital Punishment in the United States. Journal of the American Institute of Criminal Law and Criminology, 17 (2), 234.

Byrd, V., & Allen, D. (2017, February 21). ANA Releases New Position Statement Opposing Capital Punishment. American Nurses Association. https://www.nursingworld.org/news/news-releases/2017-news-releases/ana-releases-new-position-statement-opposing-capital-punishment/ . Accessed 8 June 2018.

Coker v. Georgia. (1977) 433 U.S. 584 (1977).

Cowan, C. L., Thompson, W., & Ellsworth, P. C. (1984). The effects of death qualification on jurors' predisposition to convict and on the quality of deliberation. Law and Human Behavior, 8 , 53–80.

Culp-Ressler, T. (2014, April 10). One Sentence That Could Help End The Death Penalty In America. Think Progress. https://thinkprogress.org/one-sentence-that-could-help-end-the-death-penalty-in-america-8246f562d923/ . Accessed 8 June 2018.

Donohue, J. J. (2011, October 15). Capital Punishment in Connecticut, 1973–2007: A Comprehensive Evaluation from 4686 Murders to One Execution. https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/documents/DonohueCTStudy.pdf . Accessed 8 Jun 2018.

DPIC. (2002). Executions is the U.S. 1608-2002: The ESPY File Executions by State. https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/documents/ESPYyear.pdf . Accessed 25 Sep 2018.

DPIC. (2009). Governor bill Richardson signs repeal of the death penalty. Death Penalty Information Center . https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/governor-bill-richardson-signs-repeal-death-penalty . Accessed 8 June 2018.

DPIC. (2016, November 9). States With and Without the Death Penalty. Death Penalty Information Center. https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/states-and-without-death-penalty . Accessed 7 June 2018.

DPIC. (2017, December 31). Death sentences in the United States from 1977 by state and by year. Death Penalty Information Center . https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/death-sentences-united-states-1977-present . Accessed 7 June 2018.

DPIC. (2018a). Abolitionist and Retentionist Countries. https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/abolitionist-and-retentionist-countries . Accessed 25 Sep 2018.

DPIC. (2018b). Nebraska Executes Carey Dean Moore in First Execution in 21 Years. https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/node/7175 . Accessed 25 Sep 2018.

DPIC. (2018c). Recent Legislative Activity. https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/recent-legislative-activity#currentyear . Accessed 25 Sep 2018.

DPIC. (2018d). States With and Without the Death Penalty. https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/states-and-without-death-penalty . Accessed 8 Apr 2019.

DPIC. (2018e). The Death Penalty: An International Perspective. https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/death-penalty-international-perspective#interexec . Accessed 25 Sep 2018.

DPIC. (2018f, May 16). Searchable execution database. https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/views-executions . Accessed 25 Sep 2018.

DPIC. (2018g, July 12). Poll: Washington State Voters Overwhelmingly Prefer Life Sentences to Death Penalty. https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/node/7149 . Accessed 25 Sep 2018.

Eberhart v. Georgia. (1977) 433 U.S. 917 (1977).

Eckholm, E. (2016, August 2). Delaware Supreme Court Rules State’s Death Penalty Unconstitutional. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/03/us/delaware-supreme-court-rules-states-death-penalty-unconstitutional.html. Accessed 8 June 2018 .

Ellsworth, P. C. (1988). Unpleasant facts: The Supreme Court's response to empirical research on capital punishment. In K. C. Haas & J. A. Inciardi (Eds.), Challenging capital punishment: Legal and social science approaches (pp. 177–211). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Enmund V. Florida (1982) 458 U.S. 782 (1982),

Epstein, L. (1992). The supreme court and legal change: Abortion and the death penalty. Univ of North Carolina Press.

Erickson, R. J., & Simon, R. J. (1998). The use of social science data in supreme court decisions. University of Illinois Press.

European Commission. (2018, June 7). Fight against death penalty. International Cooperation and Development. https://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/sectors/human-rights-and-governance/democracy-and-human-rights/fight-against-death-penalty_en . Accessed 7 June 2018.

Ford v. Wainwright. (1986) 477 U.S. 399 (1986).

Furman v Georgia. (1972) 408 U.S. 238 (1972).

Gallup Inc. (n.d.). Death penalty. Gallup.com . http://news.gallup.com/poll/1606/Death-Penalty.aspx . Accessed 21 January 2018.

Gregg v Georgia. (1976) 428 U.S. 153 (1976).

Grinberg, E. (2009, March 18). New Mexico governor repeals death penalty in state. CNN. http://www.cnn.com/2009/CRIME/03/18/new.mexico.death.penalty/ . Accessed 8 June 2018.

Hall v Florida. (2014) 527 U.S. ___ (2014).

Hall, H. V. (2008). Forensic Psychology and Neuropsychology for Criminal and Civil Cases . CRC Press.

Haney, C. (Ed.). (1984). Death qualification [Special issue]. Law and Human Behavior, 8 (1&2).

Haney, C. (2016, August 16). Floridians prefer life without parole over capital punishment for murderers. Tampa Bay Times. http://www.tampabay.com/opinion/columns/column-floridians-prefer-life-without-parole-over-capital-punishment-for/2289719 . Accessed 7 June 2018.

Hillsman, S. (2005). Executive Officer’s column: What really mattered to the supreme court. American Sociological Association. http://www.asanet.org/sites/default/files/savvy/footnotes/mayjun05/exec.html . Accessed 22 August 2018.

Hodgson v. Minnesota. (1990) 497 U.S. 417 (1990).

Hooks v. Georgia. (1977) 433 U.S. 917 (1977).

Hughes, C. C., & Robinson, M. (2013). Perceptions of law enforcement officers on capital punishment in the United States. International Journal of Criminal Justice Sciences; Thirunelveli, 8 (2), 153–165.

Hurst v Florida. (2016) 577 U.S. ___ (2016).

In re Kemmler. (1890) 136 U.S. 436 (1890).

International Commission Against the Death Penalty. (2013). How States Abolish the Death Penalty. http://www.icomdp.org/cms/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Report-How-States-abolition-the-death-penalty.pdf . Accessed 8 June 2018.

Keil, T. J., & Vito, G. F. (1995). Race and the death penalty in Kentucky murder trials: 1976-1991. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 20 (1), 17–36.

Kennedy v. Louisiana. (2008) 554 U.S. 407 (2008).

Maryland Commission on Capital Punishment. (2008). Final Report to the General Assembly . https://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc5300/sc5339/000113/012000/012331/unrestricted/20100208e.pdf . Accessed 8 June 2018.

NAACP. (2017, January 17). Death penalty fact sheet. National Association for the Advancement of Colored People . http://www.naacp.org/latest/naacp-death-penalty-fact-sheet/ . Accessed 7 June 2018.

New Jersey Death Penalty Study Commission. (2007). New Jersey Death Penalty Study Commission Report. http://www.njleg.state.nj.us/committees/dpsc_final.pdf . Accessed 8 June 2018.

New Mexico Coalition to Repeal the Death Penalty. (2017). New Mexico death penalty action. New Mexico Coalition to Repeal the Death Penalty . http://www.nmrepeal.org/ . Accessed 8 June 2018.

Oliphant, B. (2016, September 29). Support for death penalty lowest in more than four decades. Pew Research Center. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/09/29/support-for-death-penalty-lowest-in-more-than-four-decades/ . Accessed 31 July 2018.

Oliphant, B. (2018, June 11). Public support for the death penalty ticks up. Pew Research Center. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/06/11/us-support-for-death-penalty-ticks-up-2018/ . Accessed 31 July 2018.

Oxford, A. (2018, February 3). Swift end for House bill to reinstate death penalty. The Santa Fe New Mexican. http://www.santafenewmexican.com/news/legislature/swift-end-for-house-bill-to-reinstate-death-penalty/article_4dec9f33-0253-50c3-8e22-16a12ba01f9a.html . Accessed 8 June 2018.

Packer, H. L. (1963). Making the Punishment Fit the Crime. Harvard Law Review, 77 , 1071.

Panetti v. Quarterman. (2007) 551 U.S. 930 (2007).

Paternoster, R. (1991). Prosecutorial discretion and capital sentencing in North and South Carolina. In R. M. Bohm (Ed.), The death penalty in America: Current research (pp. 39–52). Cincinnati, OH: Anderson.

Paternoster, R., & Kazyaka, A. (1988). Racial considerations in capital punishment: The failure of evenhanded justice. In K. C. Haas & J. A. Inciardi (Eds.), Challenging capital punishment: Legal and social science approaches (pp. 113–148). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Pentin, E. (2018, August 2). Pope Francis Changes Catechism to Say Death Penalty ‘Inadmissible.’ http://www.ncregister.com/blog/edward-pentin/pope-francis-changes-catechism-to-declare-death-penalty-inadmissible . Accessed 25 Sep 2018.

Pierce, G. L., & Radelet, M. L. (2002). Race, religion, and death sentencing in Illinois, 1988-1997. Oregon Law Review, 81 , 39–96.

Powell v. Alabama. (1932) 287 U.S. 45 (1932).

Quinnipiac University National Poll. (2018, March 22). Most U.S. Voters Back Life Over Death Penalty. QU Poll. https://poll.qu.edu/national/release-detail?ReleaseID=2530 . Accessed 8 June 2018.

Robinson, M. B. (2008). Death nation: the experts explain American capital punishment . Upper Saddle River, N.J: Pearson/prentice hall.

Roper v. Simmons. (2005) 543 U.S. 551 (2005).

Rosenberg, M. (1968). The logic of survey analysis. New York: Basic.

Sanger, R. M. (2003). Comparison of the Illinois commission report on capital punishment with the capital punishment system in California. Santa Clara Law Review, 44 , 101–234.

Saklofske, D. H., Schwean, V. L., & Reynolds, C. R. (2013). The Oxford Handbook of Child Psychological Assessment: Psychological Evaluation | Psychological Testing . Oxford University Press.

Singleton v. Norris. (2003) 267 F.3d 859 (8th Cir. 2003).

Sorensen, J. R., & Wallace, D. H. (1995). Capital punishment in Missouri: Examining the issue of racial disparity. Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 13 (1), 61–81.

Sourcebook of Criminal Justice Statistics. (2013). Table 2.51.2013: Attitudes toward the death penalty for persons convicted of murder. https://www.albany.edu/sourcebook/pdf/t2512013.pdf . Accessed 21 January 2018.

Stanford v. Kentucky. (1989) 492 U.S. 361 (1989).

Thomson, E. (1997). Discrimination and the Death Penalty in Arizona. Criminal Justice Review, 22 (1), 65–76.

Thompson v. Oklahoma. (1988) 487 U.S. 815 (1988).

Top Stories. (2017, October 5). Lower house in US state of Delaware votes to reinstate death penalty. Top Stories. http://www.dw.com/en/lower-house-in-us-state-of-delaware-votes-to-reinstate-death-penalty/a-38781130 . Accessed 8 June 2018.

Trop v. Dulles. (1958) 356 U.S. 86 (1958).

UN General Assembly. (1989, November 15). Resolution 44/824: 2nd Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights Aiming at the Abolition of the Death Penalty. http://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/44/128 . Accessed 7 June 2018.

UN General Assembly. (2015, February 4). Resolution 69/186: Moratorium on the use of the death penalty. http://dag.un.org/bitstream/handle/11176/158748/A_RES_69_186-EN.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y . Accessed 7 June 2018.

United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. (1980). Bishops’ statement on capital punishment. United States Conference of Catholic Bishops . http://www.usccb.org/issues-and-action/human-life-and-dignity/death-penalty-capital-punishment/statement-on-capital-punishment.cfm . Accessed 7 June 2018.

Vollum, S., Carmen, R. V. del, Frantzen, D., Miguel, C. S., Cheeseman, K., Carmen, R. V. del, … Cheeseman, K. (2015). The death penalty : Constitutional issues, commentaries, and case briefs. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315721293

Waldo, G. P., & Chiricos, T. G. (1977). Work release and recidivism: An empirical evaluation of a social policy. Evaluation Quarterly, 1(1), 87–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193841X7700100104 .

Wanger, E. G. (2017). Fighting the death penalty . East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press.

Warden, R. (2012). How and why Illinois abolished the death penalty. Law and Inequality, 30 (2), 244–286.

Weems v. United States. (1910) 217 U.S. 349 (1910).

White, D. L. (2018, March 2). Survey Shows Most Pinellas County Voters Oppose Death Penalty. St. Pete Patch. https://patch.com/florida/stpete/survey-shows-most-pinellas-county-voters-oppose-death-penalty . Accessed 7 June 2018.

Wilkerson v. Utah. (1879) 99 U.S. 130 (1879).

Wilson, M. J. (2008). The application of the death penalty in New Mexico, July 1979 through December 2007: An empirical analysis. New Mexico Law Review, 38 , 255–302.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

College of Criminology and Criminal Justice, Florida State University, 112 S. Copeland Street, Tallahassee, FL, 32306-1273, USA

Gordon P. Waldo & Wesley Myers

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Gordon P. Waldo .

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Waldo, G.P., Myers, W. Criminological Research and the Death Penalty: Has Research by Criminologists Impacted Capital Punishment Practices?. Am J Crim Just 44 , 536–580 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-019-09478-4

Download citation

Received : 02 April 2019

Accepted : 02 April 2019

Published : 16 April 2019

Issue Date : 15 August 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-019-09478-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Death penalty

- Capital punishment

- Impact of research

- Policy implications

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Follow us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

- Criminal Justice

- Environment

- Politics & Government

- Race & Gender

Expert Commentary

The research on capital punishment: Recent scholarship and unresolved questions

2014 review of research on capital punishment, including studies that attempt to quantify rates of innocence and the potential deterrence effect on crime.

Republish this article

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License .

by Alexandra Raphel and John Wihbey, The Journalist's Resource January 5, 2015

This <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org/criminal-justice/research-capital-punishment-key-recent-studies/">article</a> first appeared on <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org">The Journalist's Resource</a> and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.<img src="https://journalistsresource.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cropped-jr-favicon-150x150.png" style="width:1em;height:1em;margin-left:10px;">

Over the past year the death penalty has again come into focus as a major public policy and political issue, catalyzed by several high-profile events.

The botched execution of convicted murderer and rapist Clayton Lockett in Oklahoma in 2014 was seen as a potential turning point in the debate, bringing increased attention to the mechanisms by which persons are executed. That was followed by a number of other closely scrutinized cases, and the year ended with few executions relative to years past. On December 31, 2014, Maryland Gov. Martin O’Malley commuted the sentences of the remaining four prisoners on death row in that state. In 2013, Maryland became the 18th state to abolish the death penalty after Connecticut in 2012 and New Mexico in 2009.

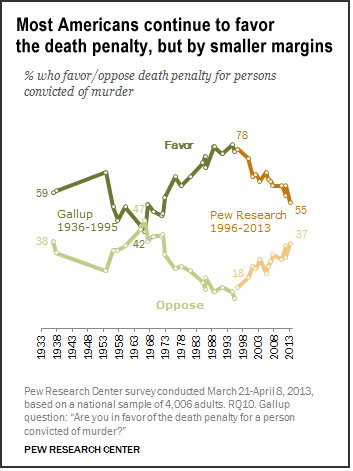

Meanwhile, polling data suggests some softening of public attitudes, though the majority Americans continue to support capital punishment. Gallop noted in October 2014 that the level of public support (60%) is at its lowest in 40 years. A Washington Post -ABC News poll in mid-2014 found that more Americans support life sentences, rather than the death penalty, for convicted murderers. Further, recent polls from the Pew Research Center indicate that only a bare majority of Americans now support capital punishment, 55%, down from 78% in 1996.

Scholarly research sheds light on a number of important aspects of this issue:

False convictions

One key reason for the contentious debate is the concern that states are executing innocent people. How many people are unjustly facing the death penalty? By definition, it is difficult to obtain a reliable answer to this question. Presumably if judges, juries, and law enforcement were always able to conclusively determine who was innocent, those defendants would simply not be convicted in the first place. When capital punishment is the sentence, however, this issue takes on new importance.

Some believe that when it comes to death-penalty cases, this is not a huge cause for concern. In his concurrent opinion in the 2006 Supreme Court case Kansas v. Marsh , Justice Antonin Scalia suggested that the execution error rate was minimal, around 0.027%. However, a 2014 study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggests that the figure could be higher. Authors Samuel Gross (University of Michigan Law School), Barbara O’Brien (Michigan State University College of Law), Chen Hu (American College of Radiology) and Edward H. Kennedy (University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine) examine data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics and the Department of Justice relating to exonerations from 1973 to 2004 in an attempt to estimate the rate of false convictions among death row defendants. (Determining innocence with full certainty is an obvious challenge, so as a proxy they use exoneration — “an official determination that a convicted defendant is no longer legally culpable for the crime.”) In short, the researchers ask: If all death row prisoners were to remain under this sentence indefinitely, how many of them would have eventually been found innocent (exonerated)?

Interestingly, the authors also note that advances in DNA identification technology are unlikely to have a large impact on false conviction rates because DNA evidence is most often used in cases of rape rather than homicide. To date, only about 13% of death row exonerations were the result of DNA testing. The Innocence Project , a litigation and public policy organization founded in 1992, has been deeply involved in many such cases.

Death penalty deterrence effects: What do we know?

A chief way proponents of capital punishment defend the practice is the idea that the death penalty deters other people from committing future crimes. For example, research conducted by John J. Donohue III (Yale Law School) and Justin Wolfers (University of Pennsylvania) applies economic theory to the issue: If people act as rational maximizers of their profits or well-being, perhaps there is reason to believe that the most severe of punishments would serve as a deterrent. (The findings of their 2009 study on this issue, “Estimating the Impact of the Death Penalty on Murder,” are inconclusive.) In contrast, one could also imagine a scenario in which capital punishment leads to an increased homicide rate because of a broader perception that the state devalues human life. It could also be possible that the death penalty has no effect at all because information about executions is not diffused in a way that influences future behavior.

In 1978 — two years after the Supreme Court issued its decision reversing a previous ban on the death penalty ( Gregg v. Georgia ) — the National Research Council (NRC) published a comprehensive review of the current research on capital punishment to determine whether one of these hypotheses was more empirically supported than the others. The NRC concluded that “available studies provide no useful evidence on the deterrent effect of capital punishment.”

Researchers have subsequently used a number of methods in an effort to get closer to an accurate estimate of the deterrence effect of the death penalty. Many of the studies have reached conflicting conclusions, however. To conduct an updated review, the NRC formed the Committee on Deterrence and the Death Penalty, comprised of academics from economics departments and public policy schools from institutions around the country, including the Carnegie Mellon University, University of Chicago and Duke University.

In 2012, the Committee published an updated report that concluded that not much had changed in recent decades: “Research conducted in the 30 years since the earlier NRC report has not sufficiently advanced knowledge to allow a conclusion, however qualified, about the effect of the death penalty on homicide rates.” The report goes on to recommend that none of the reviewed reports be used to influence public policy decisions on the death penalty.

Why has the research not been able to provide any definitive answers about the impact of the death penalty? One general challenge is that when it comes to capital punishment, a counter-factual policy is simply not observable. You cannot simultaneously execute and not execute defendants, making it difficult to isolate the impact of the death penalty. The Committee also highlights a number of key flaws in the research designs:

- There are both capital and non-capital punishment options for people charged with serious crimes. So, the relevant question on the deterrent effect of capital punishment specifically “is the differential deterrent effect of execution in comparison with the deterrent effect of other available or commonly used penalties.” None of the studies reviewed by the Committee took into account these severe, but noncapital punishments, which could also have an effect on future behaviors and could confound the estimated deterrence effect of capital punishment.

- “They use incomplete or implausible models of potential murderers’ perceptions of and response to the capital punishment component of a sanction regime”

- “The existing studies use strong and unverifiable assumptions to identify the effects of capital punishment on homicides.”

In a 2012 study, “Deterrence and the Dealth Penalty: Partial Identificaiton Analysis Using Repeated Cross Sections,” authors Charles F. Manski (Northwestern University) and John V. Pepper (University of Virginia) focus on the third challenge. They note: “Data alone cannot reveal what the homicide rate in a state without (with) a death penalty would have been had the state (not) adopted a death penalty statute. Here, as always when analyzing treatment response, data must be combined with assumptions to enable inference on counterfactual outcomes.”

However, even though the authors do not arrive at a definitive conclusion, the National Research Council Committee notes that this type of research holds some value: “Rather than imposing the strong but unsupported assumptions required to identify the effect of capital punishment on homicides in a single model or an ad hoc set of similar models, approaches that explicitly account for model uncertainty may provide a constructive way for research to provide credible albeit incomplete answers.”

Another strategy researchers have taken is to limit the focus of studies on potential short-term effects of the death penalty. In a 2009 paper, “The Short-Term Effects of Executions on Homicides: Deterrence, Displacement, or Both?” authors Kenneth C. Land and Hui Zheng of Duke University, along with Raymond Teske Jr. of Sam Houston State University, examine monthly execution data (1980-2005) from Texas, “a state that has used the death penalty with sufficient frequency to make possible relatively stable estimates of the homicide response to executions.” They conclude that “evidence exists of modest, short-term reductions in the numbers of homicides in Texas in the months of or after executions.” Depending on which model they use, these deterrent effects range from 1.6 to 2.5 homicides.

The NRC’s Committee on Deterrence and the Death Penalty commented on the findings, explaining: “Land, Teske and Zheng (2009) should be commended for distinguishing between periods in Texas when the use of capital punishment appears to have been erratic and when it appears to have been systematic. But they fail to integrate this distinction into a coherently delineated behavioral model that incorporates sanctions regimes, salience, and deterrence. And, as explained above, their claims of evidence of deterrence in the systematic regime are flawed.”

A more recent paper (2012) from the three authors, “The Differential Short-Term Impacts of Executions on Felony and Non-Felony Homicides,” addresses some of these concerns. Published in Criminology and Public Policy , the paper reviews and updates some of their earlier findings by exploring “what information can be gained by disaggregating the homicide data into those homicides committed in the course of another felony crime, which are subject to capital punishment, and those committed otherwise.” The results produce a number of different findings and models, including that “the short-lived deterrence effect of executions is concentrated among non-felony-type homicides.”

Other factors to consider

The question of what kinds of “mitigating” factors should prevent the criminal justice system from moving forward with an execution remains hotly disputed. A 2014 paper published in the Hastings Law Journal , “The Failure of Mitigation?” by scholars at the University of North Carolina and DePaul University, investigates recent executions of persons with possible mental or intellectual disabilities. The authors reviewed 100 cases and conclude that the “overwhelming majority of executed offenders suffered from intellectual impairments, were barely into adulthood, wrestled with severe mental illness, or endured profound childhood trauma.”

Two significant recommendations for reforming the existing process also are supported by some academic research. A 2010 study by Pepperdine University School of Law published in Temple Law Review , “Unpredictable Doom and Lethal Injustice: An Argument for Greater Transparency in Death Penalty Decisions,” surveyed the decision-making process among various state prosecutors. At the request of a state commission, the authors first surveyed California district attorneys; they also examined data from the other 36 states that have the death penalty. The authors found that prosecutors’ capital punishment filing decisions remain marked by local “idiosyncrasies,” meaning that “the very types of unfairness that the Supreme Court sought to eliminate” beginning in 1972 may still “infect capital cases.” They encourage “requiring prosecutors to adhere to an established set of guidelines.” Finally, there has been growing support for taping interrogations of suspects in capital cases, so as to guard against the phenomenon of false confessions .

Related reading: For an international perspective on capital punishment, see Amnesty International’s 2013 report ; for more information on the evolution of U.S. public opinion on the death penalty, see historical trends from Gallup .

Keywords: crime, prisons, death penalty, capital punishment

About the Authors

Alexandra Raphel

John Wihbey

Finding Sources for Death Penalty Research

Barry Winiker/photolibrary/Getty Images

- Writing Research Papers

- Writing Essays

- English Grammar

- M.Ed., Education Administration, University of Georgia

- B.A., History, Armstrong State University

One of the most popular topics for an argument essay is the death penalty . When researching a topic for an argumentative essay , accuracy is important, which means the quality of your sources is important.

If you're writing a paper about the death penalty, you can start with this list of sources, which provide arguments for all sides of the topic.

Amnesty International Site

Amnesty International views the death penalty as "the ultimate, irreversible denial of human rights." This website provides a gold mine of statistics and the latest breaking news on the subject.

Mental Illness on Death Row

Death Penalty Focus is an organization that aims to bring about the abolition of capital punishment and is a great resource for information. You will find evidence that many of the people executed over the past decades are affected by a form of mental illness or disability.

Pros and Cons of the Death Penalty

This extensive article provides an overview of arguments for and against the death penalty and offers a history of notable events that have shaped the discourse for activists and proponents.

Pro-Death Penalty Links

This page comes from ProDeathPenalty and contains a state-by-state guide to capital punishment resources. You'll also find a list of papers written by students on topics related to capital punishment.

- 100 Persuasive Speech Topics for Students

- Capital Punishment: Pros and Cons of the Death Penalty

- Pros & Cons of the Death Penalty

- 5 Arguments in Favor of the Death Penalty

- Ethos, Logos, Pathos for Persuasion

- History of Capital Punishment in Canada

- Preparing an Argument Essay: Exploring Both Sides of an Issue

- Recent Legal History of the Death Penalty in America

- Tips on How to Write an Argumentative Essay

- The Death Penalty in the United States

- New Challenges to the Death Penalty

- 50 Argumentative Essay Topics

- Furman v. Georgia: Supreme Court Case, Arguments, Impact

- "The Penalty of Death" by H.L. Mencken

- The Best Interactive Debate Websites for Students and Teachers

- Coker v. Georgia: Supreme Court Case, Arguments, Impact

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

- Most Americans Favor the Death Penalty Despite Concerns About Its Administration

78% say there is some risk of innocent people being put to death

Table of contents.

- Acknowledgments

- Methodology

Pew Research Center conducted this study to better understand Americans’ views about the death penalty. For this analysis, we surveyed 5,109 U.S. adults from April 5 to 11, 2021. Everyone who took part in this survey is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology .

Here are the questions used for the report, along with responses, and its methodology .

The use of the death penalty is gradually disappearing in the United States. Last year, in part because of the coronavirus outbreak, fewer people were executed than in any year in nearly three decades .

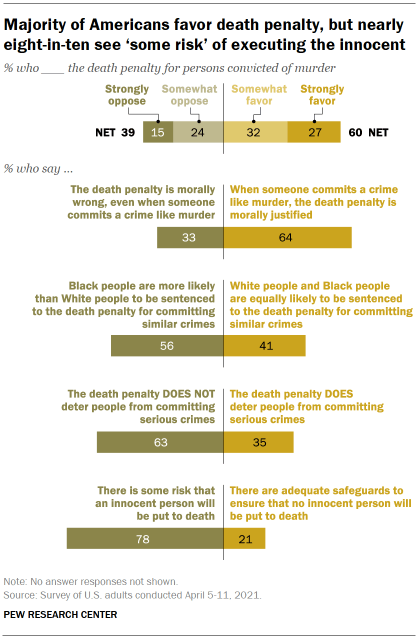

Yet the death penalty for people convicted of murder continues to draw support from a majority of Americans despite widespread doubts about its administration, fairness and whether it deters serious crimes.

More Americans favor than oppose the death penalty: 60% of U.S. adults favor the death penalty for people convicted of murder, including 27% who strongly favor it. About four-in-ten (39%) oppose the death penalty, with 15% strongly opposed, according to a new Pew Research Center survey.

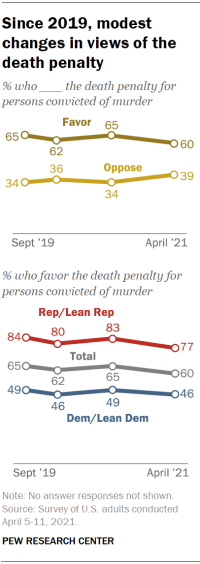

The survey, conducted April 5-11 among 5,109 U.S. adults on the Center’s American Trends Panel, finds that support for the death penalty is 5 percentage points lower than it was in August 2020, when 65% said they favored the death penalty for people convicted of murder.

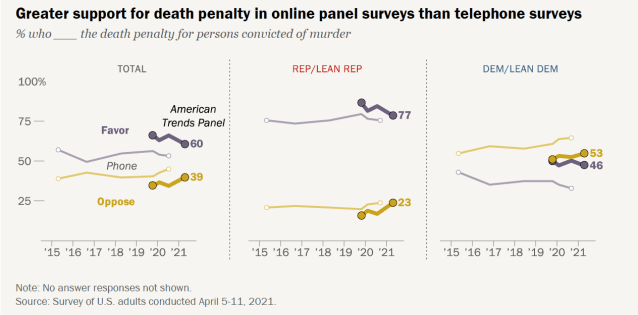

While public support for the death penalty has changed only modestly in recent years, support for the death penalty declined substantially between the late 1990s and the 2010s. (See “Death penalty draws more Americans’ support online than in telephone surveys” for more on long-term measures and the challenge of comparing views across different survey modes.)

Large shares of Americans express concerns over how the death penalty is administered and are skeptical about whether it deters people from committing serious crimes.

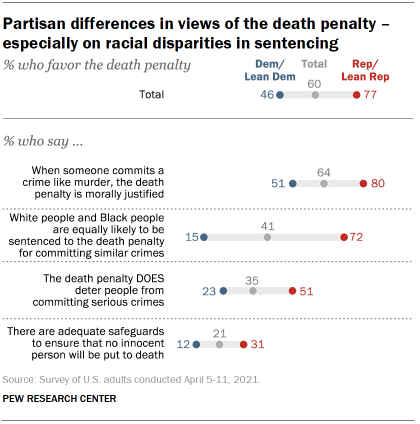

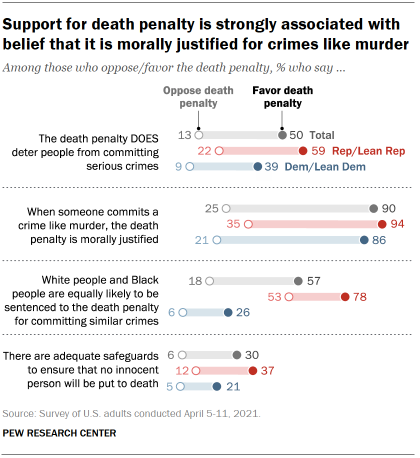

Nearly eight-in-ten (78%) say there is some risk that an innocent person will be put to death, while only 21% think there are adequate safeguards in place to prevent that from happening. Only 30% of death penalty supporters – and just 6% of opponents – say adequate safeguards exist to prevent innocent people from being executed.

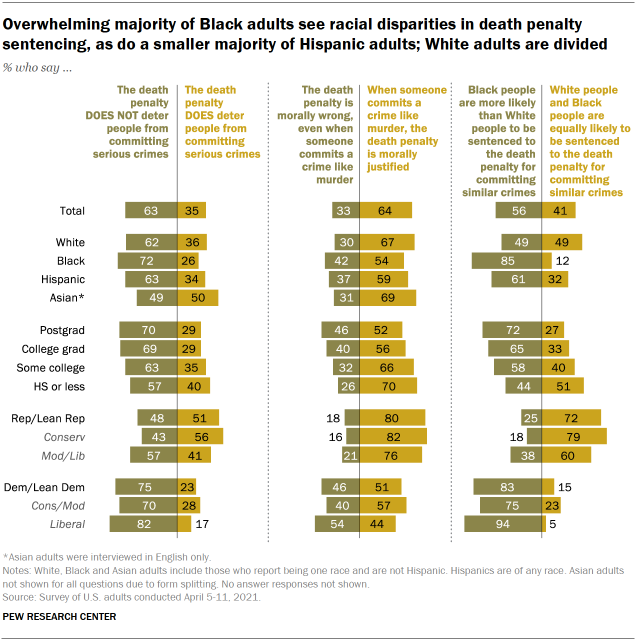

A majority of Americans (56%) say Black people are more likely than White people to be sentenced to the death penalty for being convicted of serious crimes. This view is particularly widespread among Black adults: 85% of Black adults say Black people are more likely than Whites to receive the death penalty for being convicted of similar crimes (61% of Hispanic adults and 49% of White adults say this).

Moreover, more than six-in-ten Americans (63%), including about half of death penalty supporters (48%), say the death penalty does not deter people from committing serious crimes.

Yet support for the death penalty is strongly associated with a belief that when someone commits murder, the death penalty is morally justified. Among the public overall, 64% say the death penalty is morally justified in cases of murder, while 33% say it is not justified. An overwhelming share of death penalty supporters (90%) say it is morally justified under such circumstances, compared with 25% of death penalty opponents.

The data in the most recent survey, collected from Pew Research Center’s online American Trends Panel (ATP) , finds that 60% of Americans favor the death penalty for persons convicted of murder. Over four ATP surveys conducted since September 2019, there have been relatively modest shifts in these views – from a low of 60% seen in the most recent survey to a high of 65% seen in September 2019 and August 2020.

In Pew Research Center phone surveys conducted between September 2019 and August 2020 (with field periods nearly identical to the online surveys), support for the death penalty was significantly lower: 55% favored the death penalty in September 2019, 53% in January 2020 and 52% in August 2020. The consistency of this difference points to substantial mode effects on this question. As a result, survey results from recent online surveys are not directly comparable with past years’ telephone survey trends. A post accompanying this report provides further detail and analysis of the mode differences seen on this question. And for more on mode effects and the transition from telephone surveys to online panel surveys, see “What our transition to online polling means for decades of phone survey trends” and “Trends are a cornerstone of public opinion research. How do we continue to track changes in public opinion when there’s a shift in survey mode?”

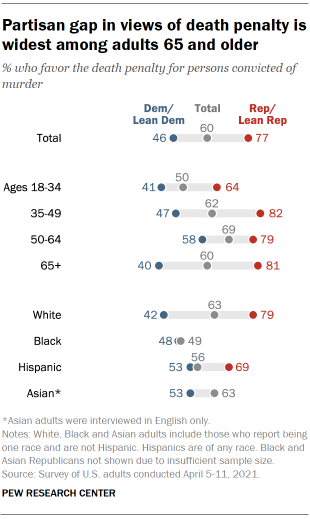

Partisanship continues to be a major factor in support for the death penalty and opinions about its administration. Just over three-quarters of Republicans and independents who lean toward the Republican Party (77%) say they favor the death penalty for persons convicted of murder, including 40% who strongly favor it.

Democrats and Democratic leaners are more divided on this issue: 46% favor the death penalty, while 53% are opposed. About a quarter of Democrats (23%) strongly oppose the death penalty, compared with 17% who strongly favor it.

Over the past two years, the share of Republicans who say they favor the death penalty for persons convicted of murder has decreased slightly – by 7 percentage points – while the share of Democrats who say this is essentially unchanged (46% today vs. 49% in 2019).

Republicans and Democrats also differ over whether the death penalty is morally justified, whether it acts as a deterrent to serious crime and whether adequate safeguards exist to ensure that no innocent person is put to death. Republicans are 29 percentage points more likely than Democrats to say the death penalty is morally justified, 28 points more likely to say it deters serious crimes, and 19 points more likely to say that adequate safeguards exist.

But the widest partisan divide – wider than differences in opinions about the death penalty itself – is over whether White people and Black people are equally likely to be sentenced to the death penalty for committing similar crimes.

About seven-in-ten Republicans (72%) say that White people and Black people are equally likely to be sentenced to death for the same types of crimes. Only 15% of Democrats say this. More than eight-in-ten Democrats (83%) instead say that Black people are more likely than White people to be sentenced to the death penalty for committing similar crimes.

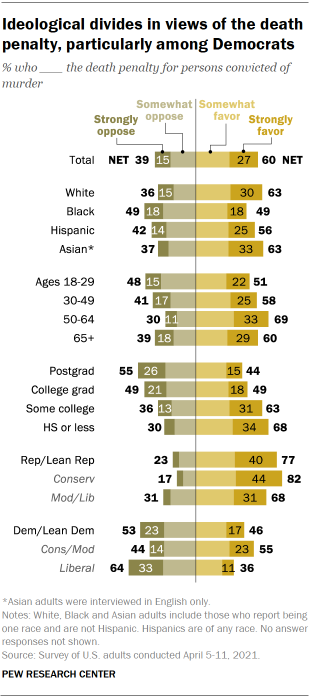

Differing views of death penalty by race and ethnicity, education, ideology

There are wide ideological differences within both parties on this issue. Among Democrats, a 55% majority of conservatives and moderates favor the death penalty, a position held by just 36% of liberal Democrats (64% of liberal Democrats oppose the death penalty). A third of liberal Democrats strongly oppose the death penalty, compared with just 14% of conservatives and moderates.

While conservative Republicans are more likely to express support for the death penalty than moderate and liberal Republicans, clear majorities of both groups favor the death penalty (82% of conservative Republicans and 68% of moderate and liberal Republicans).

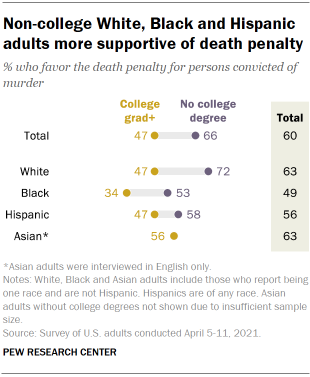

As in the past, support for the death penalty differs across racial and ethnic groups. Majorities of White (63%), Asian (63%) and Hispanic adults (56%) favor the death penalty for persons convicted of murder. Black adults are evenly divided: 49% favor the death penalty, while an identical share oppose it.

Support for the death penalty also varies across age groups. About half of those ages 18 to 29 (51%) favor the death penalty, compared with about six-in-ten adults ages 30 to 49 (58%) and those 65 and older (60%). Adults ages 50 to 64 are most supportive of the death penalty, with 69% in favor.

There are differences in attitudes by education, as well. Nearly seven-in-ten adults (68%) who have not attended college favor the death penalty, as do 63% of those who have some college experience but no degree.

About half of those with four-year undergraduate degrees but no postgraduate experience (49%) support the death penalty. Among those with postgraduate degrees, a larger share say they oppose (55%) than favor (44%) the death penalty.

The divide in support for the death penalty between those with and without college degrees is seen across racial and ethnic groups, though the size of this gap varies. A large majority of White adults without college degrees (72%) favor the death penalty, compared with about half (47%) of White adults who have degrees. Among Black adults, 53% of those without college degrees favor the death penalty, compared with 34% of those with college degrees. And while a majority of Hispanic adults without college degrees (58%) say they favor the death penalty, a smaller share (47%) of those with college degrees say this.

Intraparty differences in support for the death penalty

Republicans are consistently more likely than Democrats to favor the death penalty, though there are divisions within each party by age as well as by race and ethnicity.

Republicans ages 18 to 34 are less likely than other Republicans to say they favor the death penalty. Just over six-in-ten Republicans in this age group (64%) say this, compared with about eight-in-ten Republicans ages 35 and older.

Among Democrats, adults ages 50 to 64 are much more likely than adults in other age groups to favor the death penalty. A 58% majority of 50- to 64-year-old Democrats favor the death penalty, compared with 47% of those ages 35 to 49 and about four-in-ten Democrats who are 18 to 34 or 65 and older.

Overall, White adults are more likely to favor the death penalty than Black or Hispanic adults, while White and Asian American adults are equally likely to favor the death penalty. However, White Democrats are less likely to favor the death penalty than Black, Hispanic or Asian Democrats. About half of Hispanic (53%), Asian (53%) and Black (48%) Democrats favor the death penalty, compared with 42% of White Democrats.

About eight-in-ten White Republicans favor the death penalty, as do about seven-in-ten Hispanic Republicans (69%).

Differences by race and ethnicity, education over whether there are racial disparities in death penalty sentencing

There are substantial demographic differences in views of whether death sentencing is applied fairly across racial groups. While 85% of Black adults say Black people are more likely than White people to be sentenced to death for committing similar crimes, a narrower majority of Hispanic adults (61%) and about half of White adults (49%) say the same. People with four-year college degrees (68%) also are more likely than those who have not completed college (50%) to say that Black people and White people are treated differently when it comes to the death penalty.

About eight-in-ten Democrats (83%), including fully 94% of liberal Democrats and three-quarters of conservative and moderate Democrats, say Black people are more likely than White people to be sentenced to death for committing the same type of crime – a view shared by just 25% of Republicans (18% of conservative Republicans and 38% of moderate and liberal Republicans).

Across educational and racial or ethnic groups, majorities say that the death penalty does not deter serious crimes, although there are differences in how widely this view is held. About seven-in-ten (69%) of those with college degrees say this, as do about six-in-ten (59%) of those without college degrees. About seven-in-ten Black adults (72%) and narrower majorities of White (62%) and Hispanic (63%) adults say the same. Asian American adults are more divided, with half saying the death penalty deters serious crimes and a similar share (49%) saying it does not.

Among Republicans, a narrow majority of conservative Republicans (56%) say the death penalty does deter serious crimes, while a similar share of moderate and liberal Republicans (57%) say it does not.

A large majority of liberal Democrats (82%) and a smaller, though still substantial, majority of conservative and moderate Democrats (70%) say the death penalty does not deter serious crimes. But Democrats are divided over whether the death penalty is morally justified. A majority of conservative and moderate Democrats (57%) say that a death sentence is morally justified when someone commits a crime like murder, compared with fewer than half of liberal Democrats (44%).

There is widespread agreement on one topic related to the death penalty: Nearly eight-in-ten (78%) say that there is some risk an innocent person will be put to death, including large majorities among various racial or ethnic, educational, and even ideological groups. For example, about two-thirds of conservative Republicans (65%) say this – compared with 34% who say there are adequate safeguards to ensure that no innocent person will be executed – despite conservative Republicans expressing quite favorable attitudes toward the death penalty on other questions.

Overwhelming share of death penalty supporters say it is morally justified

Those who favor the death penalty consistently express more favorable attitudes regarding specific aspects of the death penalty than those who oppose it.

For instance, nine-in-ten of those who favor the death penalty also say that the death penalty is morally justified when someone commits a crime like murder. Just 25% of those who oppose the death penalty say it is morally justified.

This relationship holds among members of each party. Among Republicans and Republican leaners who favor the death penalty, 94% say it is morally justified; 86% of Democrats and Democratic leaners who favor the death penalty also say this.

By comparison, just 35% of Republicans and 21% of Democrats who oppose the death penalty say it is morally justified.

Similarly, those who favor the death penalty are more likely to say it deters people from committing serious crimes. Half of those who favor the death penalty say this, compared with 13% of those who oppose it. And even though large majorities of both groups say there is some risk an innocent person will be put to death, members of the public who favor the death penalty are 24 percentage points more likely to say that there are adequate safeguards to prevent this than Americans who oppose the death penalty.

On the question of whether Black people and White people are equally likely to be sentenced to death for committing similar crimes, partisanship is more strongly associated with these views than one’s overall support for the death penalty: Republicans who oppose the death penalty are more likely than Democrats who favor it to say White people and Black people are equally likely to be sentenced to death.

Among Republicans who favor the death penalty, 78% say that Black and White people are equally likely to receive this sentence. Among Republicans who oppose the death penalty, about half (53%) say this. However, just 26% of Democrats who favor the death penalty say that Black and White people are equally likely to receive this sentence, and only 6% of Democrats who oppose the death penalty say this.

CORRECTION (July 13, 2021): The following sentence was updated to reflect the correct timespan: “Last year, in part because of the coronavirus outbreak, fewer people were executed than in any year in nearly three decades.” The changes did not affect the report’s substantive findings.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Criminal Justice

- Death Penalty

- Politics & Policy

What the data says about crime in the U.S.

Fewer than 1% of federal criminal defendants were acquitted in 2022, before release of video showing tyre nichols’ beating, public views of police conduct had improved modestly, black americans differ from other u.s. adults over whether individual or structural racism is a bigger problem, violent crime is a key midterm voting issue, but what does the data say, most popular, report materials.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Terms & Conditions

Privacy Policy

Cookie Settings

Reprints, Permissions & Use Policy

Senate approves death penalty for drug traffickers

Senator Ali Ndume urged the Senate to replace “life imprisonment” with “death penalty” for convicted drug offenders.

The Senate has approved the death penalty for those convicted on the charge of drug trafficking in the country, despite the current NDLEA Act which stipulates a maximum penalty of life in prison as the punishment.

This resolution followed the consideration of a report of the Committees on Judiciary, Human Rights and Legal Matters and Drugs and Narcotics, National Drug Law Enforcement Agency (NDLEA) Act (Amendment) Bill, 2024, presented by the Chairman of the Committee, Senator Mohammed Monguno (APC, Borno North) during Thursday’s plenary.

The bill, which passed its third reading, intends to update the list of prohibited substances, enhance NDLEA activities, reevaluate fines, and authorise laboratory establishments.

Section 11 of the current act prescribes that “any person who, without lawful authority, imports, manufactures, produces, processes, plants or grows the drugs popularly known as cocaine, LSD, heroin or any other similar drugs shall be guilty of an offence and liable on conviction to be sentenced to imprisonment for life” was amended to reflect a stiffer penalty of death.

READ ALSO: Reps oppose NAFDAC over ban on sachet alcohol drinks

The report did not recommend a death penalty for the offence, however, during the clause-by-clause consideration, the Senate assented to a motion moved by Senator Ali Ndume (APC, Borno South), who urged the Senate to replace “life imprisonment” with “death penalty” for convicted offenders.

He said, “I support the punishment. The only way to eradicate drugs is to nip it in the bud.”

Senator Ndume’s motion was seconded by his deputy, Peter Onyekachi Nwebonyi (Ebonyi North).

Following this recommendation, the Deputy President of the Senate, Barau Jibrin , who presided over the plenary, put the amendment on the death penalty to a voice vote and ruled that the “ayes” had it.

On the contrary, Senator Adams Oshiomhole objected to the ruling, arguing that matters of life and death should not be treated hurriedly.

He said, “I have the responsibility for every law. This is a matter of life and death, I don’t believe that the ‘Ayes’ have it.”

However, Barau said it was too late because he had not promptly called for the division immediately after his ruling. The bill was thereafter read for the third time and passed by the Senate.

Sharon Eboesomi

Power: reps urge shettima to urgently implement measures for the enhancement of the national grid , reps urge tinubu to meet asuu's demand, avert possible strike actions, leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Post Comment

Related Posts

Cybersecurity levy not punitive – Senate committee chairman insists

PWD: Senate set to commence full implementation of Disability Act

Senate moves to increase salaries, allowances of judicial officers

Please email us - [email protected] - if you need this content for legitimate research purposes. Please check our privacy policy

IMAGES

COMMENTS

In this paper we build on a small number of studies that have examined cross-national public attitudes to the death penalty (Stack, 2004; Unnever and Cullen, 2010a, 2010b; Unnever et al., 2010; Van Koppen et al., 2002), providing a much-needed update to the evidence base.A great deal has changed since these studies were conducted.

"The death penalty is, in our common experience, an atavistic relic from the past that should be shed in the 21st century", said UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Volker Türk in April, 2023, during the 52nd session of the Human Rights Council. The death penalty has existed since the Code of Hammurabi, with its history seeped in politics and discrimination.

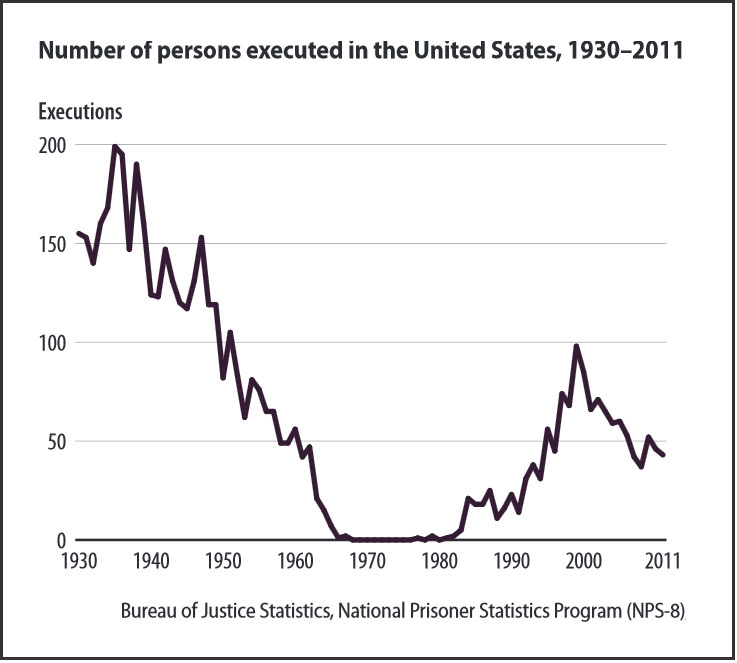

The abolitionist movement to end capital punishment also influenced state legislatures. By the early 1900s, most states had adopted laws that allowed juries to apply either the death penalty or a sentence of life in prison. Executions in the United States peaked during the 1930s at an average rate of 167 per year.

While there are several books and many articles and chapters (e.g., Alvarez, Miller, & Bornstein, 2016; Haney, 2005; Lynch, 2009; Myers, Johnson, & Nuñez, 2018) that summarize the social science research related to various aspects of the death penalty and how it has changed over time, there is limited scholarship that also synthesizes the role of social science in understanding events and ...

The state's obligation to uphold the right to life—even of those who have committed grave crimes—takes priority over considerations of retribution and deterrence. ... (ed) Matters of life and death: new introductory essays in moral philosophy, 3rd edn. McGraw-Hill, New York, pp 160-194. Google ... Death Penalty Information Center (2022 ...

This review addresses four key issues in the modern (post-1976) era of capital punishment in the United States. First, why has the United States retained the death penalty when all its peer countries (all other developed Western democracies) have abolished it? Second, how should we understand the role of race in shaping the distinctive path of capital punishment in the United States, given our ...

Capital punishment, also known as death penalty, is a government sanctioned practice. whereby a person is put to death by the state as a punishment for a crime. Since at. present 58 countries ...

Over the past 15 years there have been movements by researchers and pollsters to ... In addition, there is a lack of death penalty research capable of capturing a larger degree of variation in death penalty opinion. In an attempt to better understand death penalty opinion, the current study utilizes qualitative focus groups to ...

Following a decade of renewed interest in death penalty research, the National Research Council for the National Academies concluded in a 2012 report that "research to date on the effect of capital punishment on homicide is not informative about whether capital punishment decreases, increases, or has no effect on homicide rates" (National ...

As argued in this Article, the simplest answer to the puzzle of capital punishment's persistence is that the retributive impulse is, as Justice Potter Stewart observed, "part of the nature of man.". The answer is so obvious that what is puzzling is not the persistence of the death penalty but that some people regard this persistence as ...

In this paper, we draw on a dataset of 135,000 people from across 81 nations to examine differences in death penalty support. ... There is mixed evidence about the role of religious values in shaping death penalty support. Some research finds that religious people tend to have lower levels of support for the death penalty and similar punitive ...

death penalty were just recently at an all-time high of 80% in the 1990s, but a rapid decline to the. most recent 54% shows an erosion for death penalty support in the United States.4 Also included. in the report was a poll conducted by the Pew Research Center, which showed that over half of.

The death penalty is inhumane and violates the fundamental right to life. Physician involvement enables this continuing abuse of human rights and undermines the four pillars of medical ethics—beneficence, non-maleficence, autonomy, and justice. Universal condemnation of the death penalty, by physicians and medical associations alike, is an ...

This essay examines Death Penalty, a contemporary social issue in the world today. It gives a. general idea of what death penalty means and shows the argument revolving around th e. implementation ...

It should be noted, however, that despite all of the negative research findings about the death penalty presented by criminological researchers, and the presence of Kirk Bloodsworth (who was an innocent man exonerated from Maryland's death row in 1993) serving as a member of the commission, the vote on the above resolution to abolish the ...

Phone polls have shown a long-term decline in public support for the death penalty. In phone surveys conducted by Pew Research Center between 1996 and 2020, the share of U.S. adults who favor the death penalty fell from 78% to 52%, while the share of Americans expressing opposition rose from 18% to 44%. Phone surveys conducted by Gallup found a ...

Over the past year the death penalty has again come into focus as a major public policy and political issue, catalyzed by several high-profile events.. The botched execution of convicted murderer and rapist Clayton Lockett in Oklahoma in 2014 was seen as a potential turning point in the debate, bringing increased attention to the mechanisms by which persons are executed.

When researching a topic for an argumentative essay, accuracy is important, which means the quality of your sources is important. If you're writing a paper about the death penalty, you can start with this list of sources, which provide arguments for all sides of the topic. 01. of 04.

Most Americans Favor the Death Penalty Despite Concerns About Its Administration. Nearly eight-in-ten U.S. adults (78%) say there is some risk an innocent person will be put to death, and 63% say the death penalty does not deter people from committing serious crimes. short readJan 22, 2021.

The data in the most recent survey, collected from Pew Research Center's online American Trends Panel (ATP), finds that 60% of Americans favor the death penalty for persons convicted of murder.Over four ATP surveys conducted since September 2019, there have been relatively modest shifts in these views - from a low of 60% seen in the most recent survey to a high of 65% seen in September ...

The death penalty is one of the most controversial subjects in America today. Although the practice remains legal in 36 ... body of evidence from research has begun to develop over the past 40 years, which has provided information regarding vary-ing degrees of support certain groups of people have had for

Sharon Eboesomi May 10, 20243 min. Senator Ali Ndume urged the Senate to replace "life imprisonment" with "death penalty" for convicted drug offenders. The Senate has approved the death penalty for those convicted on the charge of drug trafficking in the country, despite the current NDLEA Act which stipulates a maximum penalty of life ...