Sexual Harassment of Women: Climate, Culture, and Consequences in Academic Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2018)

Chapter: 7 findings, conclusions, and recommendations, 7 findings, conclusions, and recommendations.

Preventing and effectively addressing sexual harassment of women in colleges and universities is a significant challenge, but we are optimistic that academic institutions can meet that challenge—if they demonstrate the will to do so. This is because the research shows what will work to prevent sexual harassment and why it will work. A systemwide change to the culture and climate in our nation’s colleges and universities can stop the pattern of harassing behavior from impacting the next generation of women entering science, engineering, and medicine.

Changing the current culture and climate requires addressing all forms of sexual harassment, not just the most egregious cases; moving beyond legal compliance; supporting targets when they come forward; improving transparency and accountability; diffusing the power structure between faculty and trainees; and revising organizational systems and structures to value diversity, inclusion, and respect. Leaders at every level within academia will be needed to initiate these changes and to establish and maintain the culture and norms. However, to succeed in making these changes, all members of our nation’s college campuses—students, faculty, staff, and administrators—will need to assume responsibility for promoting a civil and respectful environment. It is everyone’s responsibility to stop sexual harassment.

In this spirit of optimism, we offer the following compilation of the report’s findings, conclusions, and recommendations.

FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS

Chapter 2: sexual harassment research.

- Sexual harassment is a form of discrimination that consists of three types of harassing behavior: (1) gender harassment (verbal and nonverbal behaviors that convey hostility, objectification, exclusion, or second-class status about members of one gender); (2) unwanted sexual attention (unwelcome verbal or physical sexual advances, which can include assault); and (3) sexual coercion (when favorable professional or educational treatment is conditioned on sexual activity). The distinctions between the types of harassment are important, particularly because many people do not realize that gender harassment is a form of sexual harassment.

- Sexually harassing behavior can be either direct (targeted at an individual) or ambient (a general level of sexual harassment in an environment) and is harmful in both cases. It is considered illegal when it creates a hostile environment (gender harassment or unwanted sexual attention that is “severe or pervasive” enough to alter the conditions of employment, interfere with one’s work performance, or impede one’s ability to get an education) or when it is quid pro quo sexual harassment (when favorable professional or educational treatment is conditioned on sexual activity).

- There are reliable scientific methods for determining the prevalence of sexual harassment. To measure the incidence of sexual harassment, surveys should follow the best practices that have emerged from the science of sexual harassment. This includes use of the Sexual Experiences Questionnaire, the most widely used and well-validated instrument available for measuring sexual harassment; assessment of specific behaviors without requiring the respondent to label the behaviors “sexual harassment”; focus on first-hand experience or observation of behavior (rather than rumor or hearsay); and focus on the recent past (1–2 years, to avoid problems of memory decay). Relying on the number of official reports of sexual harassment made to an organization is not an accurate method for determining the prevalence.

- Some surveys underreport the incidence of sexual harassment because they have not followed standard and valid practices for survey research and sexual harassment research.

- While properly conducted surveys are the best methods for estimating the prevalence of sexual harassment, other salient aspects of sexual harassment and its consequences can be examined using other research methods , such as behavioral laboratory experiments, interviews, case studies, ethnographies, and legal research. Such studies can provide information about the presence and nature of sexually harassing behavior in an organization, how it develops and continues (and influences the organizational climate), and how it attenuates or amplifies outcomes from sexual harassment.

- Women experience sexual harassment more often than men do.

- Gender harassment (e.g., behaviors that communicate that women do not belong or do not merit respect) is by far the most common type of sexual harassment. When an environment is pervaded by gender harassment, unwanted sexual attention and sexual coercion become more likely to occur—in part because unwanted sexual attention and sexual coercion are almost never experienced by women without simultaneously experiencing gender harassment.

- Men are more likely than women to commit sexual harassment.

- Coworkers and peers more often commit sexual harassment than do superiors.

- Sexually harassing behaviors are not typically isolated incidents; rather, they are a series or pattern of sometimes escalating incidents and behaviors.

- Women of color experience more harassment (sexual, racial/ethnic, or combination of the two) than white women, white men, and men of color do. Women of color often experience sexual harassment that includes racial harassment.

- Sexual- and gender-minority people experience more sexual harassment than heterosexual women do.

- The two characteristics of environments most associated with higher rates of sexual harassment are (a) male-dominated gender ratios and leadership and (b) an organizational climate that communicates tolerance of sexual harassment (e.g., leadership that fails to take complaints seriously, fails to sanction perpetrators, or fails to protect complainants from retaliation).

- Organizational climate is, by far, the greatest predictor of the occurrence of sexual harassment, and ameliorating it can prevent people from sexually harassing others. A person more likely to engage in harassing behaviors is significantly less likely to do so in an environment that does not support harassing behaviors and/or has strong, clear, transparent consequences for these behaviors.

Chapter 3: Sexual Harassment in Academic Science, Engineering, and Medicine

- Male-dominated environment , with men in positions of power and authority.

- Organizational tolerance for sexually harassing behavior (e.g., failing to take complaints seriously, failing to sanction perpetrators, or failing to protect complainants from retaliation).

- Hierarchical and dependent relationships between faculty and their trainees (e.g., students, postdoctoral fellows, residents).

- Isolating environments (e.g., labs, field sites, and hospitals) in which faculty and trainees spend considerable time.

- Greater than 50 percent of women faculty and staff and 20–50 percent of women students encounter or experience sexually harassing conduct in academia.

- Women students in academic medicine experience more frequent gender harassment perpetrated by faculty/staff than women students in science and engineering.

- Women students/trainees encounter or experience sexual harassment perpetrated by faculty/staff and also by other students/trainees.

- Women faculty encounter or experience sexual harassment perpetrated by other faculty/staff and also by students/trainees.

- Women students, trainees, and faculty in academic medical centers experience sexual harassment by patients and patients’ families in addition to the harassment they experience from colleagues and those in leadership positions.

Chapter 4: Outcomes of Sexual Harassment

- When women experience sexual harassment in the workplace, the professional outcomes include declines in job satisfaction; withdrawal from their organization (i.e., distancing themselves from the work either physically or mentally without actually quitting, having thoughts or

intentions of leaving their job, and actually leaving their job); declines in organizational commitment (i.e., feeling disillusioned or angry with the organization); increases in job stress; and declines in productivity or performance.

- When students experience sexual harassment, the educational outcomes include declines in motivation to attend class, greater truancy, dropping classes, paying less attention in class, receiving lower grades, changing advisors, changing majors, and transferring to another educational institution, or dropping out.

- Gender harassment has adverse effects. Gender harassment that is severe or occurs frequently over a period of time can result in the same level of negative professional and psychological outcomes as isolated instances of sexual coercion. Gender harassment, often considered a “lesser,” more inconsequential form of sexual harassment, cannot be dismissed when present in an organization.

- The greater the frequency, intensity, and duration of sexually harassing behaviors, the more women report symptoms of depression, stress, and anxiety, and generally negative effects on psychological well-being.

- The more women are sexually harassed in an environment, the more they think about leaving, and end up leaving as a result of the sexual harassment.

- The more power a perpetrator has over the target, the greater the impacts and negative consequences experienced by the target.

- For women of color, preliminary research shows that when the sexual harassment occurs simultaneously with other types of harassment (i.e., racial harassment), the experiences can have more severe consequences for them.

- Sexual harassment has adverse effects that affect not only the targets of harassment but also bystanders, coworkers, workgroups, and entire organizations.

- Women cope with sexual harassment in a variety of ways, most often by ignoring or appeasing the harasser and seeking social support.

- The least common response for women is to formally report the sexually harassing experience. For many, this is due to an accurate perception that they may experience retaliation or other negative outcomes associated with their personal and professional lives.

- The dependence on advisors and mentors for career advancement.

- The system of meritocracy that does not account for the declines in productivity and morale as a result of sexual harassment.

- The “macho” culture in some fields.

- The informal communication network , in which rumors and accusations are spread within and across specialized programs and fields.

- The cumulative effect of sexual harassment is significant damage to research integrity and a costly loss of talent in academic science, engineering, and medicine. Women faculty in science, engineering, and medicine who experience sexual harassment report three common professional outcomes: stepping down from leadership opportunities to avoid the perpetrator, leaving their institution, and leaving their field altogether.

Chapter 5: Existing Legal and Policy Mechanisms for Addressing Sexual Harassment

- An overly legalistic approach to the problem of sexual harassment is likely to misjudge the true nature and scope of the problem. Sexual harassment law and policy development has focused narrowly on the sexualized and coercive forms of sexual harassment, not on the gender harassment type that research has identified as much more prevalent and at times equally harmful.

- Much of the sexual harassment that women experience and that damages women and their careers in science, engineering, and medicine does not meet the legal criteria of illegal discrimination under current law.

- Private entities, such as companies and private universities, are legally allowed to keep their internal policies and procedures—and their research on those policies and procedures—confidential, thereby limiting the research that can be done on effective policies for preventing and handling sexual harassment.

- Various legal policies, and the interpretation of such policies, enable academic institutions to maintain secrecy and/or confidentiality regarding outcomes of sexual harassment investigations, arbitration, and settlement agreements. Colleagues may also hesitate to warn one another about sexual harassment concerns in the hiring or promotion context out of fear of legal repercussions (i.e., being sued for defamation and/or discrimination). This lack of transparency in the adjudication process within organizations can cover up sexual harassment perpetrated by repeat or serial harassers. This creates additional barriers to researchers

and others studying harassment claims and outcomes, and is also a barrier to determining the effectiveness of policies and procedures.

- Title IX, Title VII, and case law reflect the inaccurate assumption that a target of sexual harassment will promptly report the harassment without worrying about retaliation. Effectively addressing sexual harassment through the law, institutional policies or procedures, or cultural change requires taking into account that targets of sexual harassment are unlikely to report harassment and often face retaliation for reporting (despite this being illegal).

- Fears of legal liability may prevent institutions from being willing to effectively evaluate training for its measurable impact on reducing harassment. Educating employees via sexual harassment training is commonly implemented as a central component of demonstrating to courts that institutions have “exercised reasonable care to prevent and correct promptly any sexually harassing behavior.” However, research has not demonstrated that such training prevents sexual harassment. Thus, if institutions evaluated their training programs, they would likely find them to be ineffective, which, in turn, could raise fears within institutions of their risk for liability because they would then knowingly not be exercising reasonable care.

- Holding individuals and institutions responsible for sexual harassment and demonstrating that sexual harassment is a serious issue requires U.S. federal funding agencies to be aware when principal investigators, co-principal investigators, and grant personnel have violated sexual harassment policies. It is unclear whether and how federal agencies will take action beyond the requirements of Title IX and Title VII to ensure that federal grants, composed of taxpayers’ dollars, are not supporting research, academic institutions, or programs in which sexual harassment is ongoing and not being addressed. Federal science agencies usually indicate (e.g., in requests for proposals or other announcements) that they have a “no-tolerance” policy for sexual harassment. In general, federal agencies rely on the grantee institutions to investigate and follow through on Title IX violations. By not assessing and addressing the role of institutions and professional organizations in enabling individual sexual harassers, federal agencies may be perpetuating the problem of sexual harassment.

- To address the effect sexual harassment has on the integrity of research, parts of the federal government and several professional societies are beginning to focus more broadly on policies about research integrity and on codes of ethics rather than on the narrow definition of research misconduct. A powerful incentive for change may be missed if sexual harassment is not considered equally important as research misconduct, in terms of its effect on the integrity of research.

Chapter 6: Changing the Culture and Climate in Higher Education

- A systemwide change to the culture and climate in higher education is required to prevent and effectively address all three forms of sexual harassment. Despite significant attention in recent years, there is no evidence to suggest that current policies, procedures, and approaches have resulted in a significant reduction in sexual harassment. It is time to consider approaches that address the systems, cultures, and climates that enable sexual harassment to perpetuate.

- Strong and effective leaders at all levels in the organization are required to make the systemwide changes to climate and culture in higher education. The leadership of the organization—at every level—plays a significant role in establishing and maintaining an organization’s culture and norms. However, leaders in academic institutions rarely have leadership training to thoughtfully address culture and climate issues, and the leadership training that exists is often of poor quality.

- Evidence-based, effective intervention strategies are available for enhancing gender diversity in hiring practices.

- Focusing evaluation and reward structures on cooperation and collegiality rather than solely on individual-level teaching and research performance metrics could have a significant impact on improving the environment in academia.

- Evidence-based, effective intervention strategies are available for raising levels of interpersonal civility and respect in workgroups and teams.

- An organization that is committed to improving organizational climate must address issues of bias in academia. Training to reduce personal bias can cause larger-scale changes in departmental behaviors in an academic setting.

- Skills-based training that centers on bystander intervention promotes a culture of support, not one of silence. By calling out negative behaviors on the spot, all members of an academic community are helping to create a culture where abusive behavior is seen as an aberration, not as the norm.

- Reducing hierarchical power structures and diffusing power more broadly among faculty and trainees can reduce the risk of sexual ha

rassment. Departments and institutions could take the following approaches for diffusing power:

- Make use of egalitarian leadership styles that recognize that people at all levels of experience and expertise have important insights to offer.

- Adopt mentoring networks or committee-based advising that allows for a diversity of potential pathways for advice, funding, support, and informal reporting of harassment.

- Develop ways the research funding can be provided to the trainee rather than just the principal investigator.

- Take on the responsibility for preserving the potential work of the research team and trainees by redistributing the funding if a principal investigator cannot continue the work because he/she has created a climate that fosters sexual harassment and guaranteeing funding to trainees if the institution or a funder pulls funding from the principal investigator because of sexual harassment.

- Orienting students, trainees, faculty, and staff, at all levels, to the academic institution’s culture and its policies and procedures for handling sexual harassment can be an important piece of establishing a climate that demonstrates sexual harassment is not tolerated and targets will be supported.

- Institutions could build systems of response that empower targets by providing alternative and less formal means of accessing support services, recording information, and reporting incidents without fear of retaliation.

- Supporting student targets also includes helping them to manage their education and training over the long term.

- Confidentiality and nondisclosure agreements isolate sexual harassment targets by limiting their ability to speak with others about their experiences and can serve to shield perpetrators who have harassed people repeatedly.

- Key components of clear anti-harassment policies are that they are quickly and easily digested (i.e., using one-page flyers or infographics and not in legally dense language) and that they clearly state that people will be held accountable for violating the policy.

- A range of progressive/escalating disciplinary consequences (such as counseling, changes in work responsibilities, reductions in pay/benefits, and suspension or dismissal) that corresponds to the severity and frequency of the misconduct has the potential of correcting behavior before it escalates and without significantly disrupting an academic program.

- In an effort to change behavior and improve the climate, it may also be appropriate for institutions to undertake some rehabilitation-focused measures, even though these may not be sanctions per se.

- For the people in an institution to understand that the institution does not tolerate sexual harassment, it must show that it does investigate and then hold perpetrators accountable in a reasonable timeframe. Institutions can anonymize the basic information and provide regular reports that convey how many reports are being investigated and what the outcomes are from the investigation.

- An approach for improving transparency and demonstrating that the institution takes sexual harassment seriously is to encourage internal review of its policies, procedures, and interventions for addressing sexual harassment, and to have interactive dialogues with members of their campus community (especially expert researchers on these topics) around ways to improve the culture and climate and change behavior.

- Cater training to specific populations; in academia this would include students, postdoctoral fellows, staff, faculty, and those in leadership.

- Attend to the institutional motivation for training , which can impact the effectiveness of the training; for instance, compliance-based approaches have limited positive impact.

- Conduct training using live qualified trainers and offer trainees specific examples of inappropriate conduct. We note that a great deal of sexual harassment training today is offered via an online mini-course or the viewing of a short video.

- Describe standards of behavior clearly and accessibly (e.g., avoiding legal and technical terms).

- To the extent that the training literature provides broad guidelines for creating impactful training that can change climate and behavior, they include the following:

- Establish standards of behavior rather than solely seek to influence attitudes and beliefs. Clear communication of behavioral expectations, and teaching of behavioral skills, is essential.

- Conduct training in adherence to best standards , including appropriate pre-training needs assessment and evaluation of its effectiveness.

- Creating a climate that prevents sexual harassment requires measuring the climate in relation to sexual harassment, diversity, and respect, and assessing progress in reducing sexual harassment.

- Efforts to incentivize systemwide changes, such as Athena SWAN, 1 are crucial to motivating organizations and departments within organizations to make the necessary changes.

- Enacting new codes of conduct and new rules related specifically to conference attendance.

- Including sexual harassment in codes of ethics and investigating reports of sexual harassment. (This is a new responsibility for professional societies, and these organizations are considering how to take into consideration the law, home institutions, due process, and careful reporting when dealing with reports of sexual harassment.)

- Requiring members to acknowledge, in writing, the professional society’s rules and codes of conduct relating to sexual harassment during conference registration and during membership sign-up and renewal.

- Supporting and designing programs that prevent harassment and provide skills to intervene when someone is being harassed.

- Strengthening statements on sexual harassment, bullying, and discrimination in professional societies’ codes of conduct, with a few defining it as research misconduct.

- Factoring in harassment-related professional misconduct into scientific award decisions.

- Professional societies have the potential to be powerful drivers of change through their capacity to help educate, train, codify, and reinforce cultural expectations for their respective scientific, engineering, and medical communities. Some professional societies have taken action to prevent and respond to sexual harassment among their membership. Although each professional society has taken a slightly different approach to addressing sexual harassment, there are some shared approaches, including the following:

___________________

1 Athena SWAN (Scientific Women’s Academic Network). See https://www.ecu.ac.uk/equalitycharters/athena-swan/ .

- There are many promising approaches to changing the culture and climate in academia; however, further research assessing the effects and values of the following approaches is needed to identify best practices:

- Policies, procedures, trainings, and interventions, specifically how they prevent and stop sexually harassing behavior, alter perception of organizational tolerance for sexually harassing behavior, and reduce the negative consequences from reporting the incidents. This includes informal and formal reporting mechanisms, bystander intervention training, academic leadership training, sexual harassment training, interventions to improve civility, mandatory reporting requirements, and approaches to supporting and improving communication with the target.

- Mechanisms for target-led resolution options and mechanisms by which the target has a role in deciding what happens to the perpetrator, including restorative justice practices.

- Mechanisms for protecting targets from retaliation.

- Rehabilitation-focused measures for disciplining perpetrators.

- Incentive systems for encouraging leaders in higher education to address the issues of sexual harassment on campus.

RECOMMENDATIONS

RECOMMENDATION 1: Create diverse, inclusive, and respectful environments.

- Academic institutions and their leaders should take explicit steps to achieve greater gender and racial equity in hiring and promotions, and thus improve the representation of women at every level.

- Academic institutions and their leaders should take steps to foster greater cooperation, respectful work behavior, and professionalism at the faculty, staff, and student/trainee levels, and should evaluate faculty and staff on these criteria in hiring and promotion.

- Academic institutions should combine anti-harassment efforts with civility-promotion programs.

- Academic institutions should cater their training to specific populations (in academia these should include students/trainees, staff, faculty, and those in leadership) and should follow best practices in designing training programs. Training should be viewed as the means of providing the skills needed by all members of the academic community, each of whom has a role to play in building a positive organizational climate focused on safety and respect, and not simply as a method of ensuring compliance with laws.

- Academic institutions should utilize training approaches that develop skills among participants to interrupt and intervene when inappropriate behavior occurs. These training programs should be evaluated to deter

mine whether they are effective and what aspects of the training are most important to changing culture.

- Anti–sexual harassment training programs should focus on changing behavior, not on changing beliefs. Programs should focus on clearly communicating behavioral expectations, specifying consequences for failing to meet these expectations, and identifying the mechanisms to be utilized when these expectations are not met. Training programs should not be based on the avoidance of legal liability.

RECOMMENDATION 2: Address the most common form of sexual harassment: gender harassment.

Leaders in academic institutions and research and training sites should pay increased attention to and enact policies that cover gender harassment as a means of addressing the most common form of sexual harassment and of preventing other types of sexually harassing behavior.

RECOMMENDATION 3: Move beyond legal compliance to address culture and climate.

Academic institutions, research and training sites, and federal agencies should move beyond interventions or policies that represent basic legal compliance and that rely solely on formal reports made by targets. Sexual harassment needs to be addressed as a significant culture and climate issue that requires institutional leaders to engage with and listen to students and other campus community members.

RECOMMENDATION 4: Improve transparency and accountability.

- Academic institutions need to develop—and readily share—clear, accessible, and consistent policies on sexual harassment and standards of behavior. They should include a range of clearly stated, appropriate, and escalating disciplinary consequences for perpetrators found to have violated sexual harassment policy and/or law. The disciplinary actions taken should correspond to the severity and frequency of the harassment. The disciplinary actions should not be something that is often considered a benefit for faculty, such as a reduction in teaching load or time away from campus service responsibilities. Decisions regarding disciplinary actions, if indicated or required, should be made in a fair and timely way following an investigative process that is fair to all sides. 2

- Academic institutions should be as transparent as possible about how they are handling reports of sexual harassment. This requires balancing issues of confidentiality with issues of transparency. Annual reports,

2 Further detail on processes and guidance for how to fairly and appropriately investigate and adjudicate these issues are not provided because they are complex issues that were beyond the scope of this study.

that provide information on (1) how many and what type of policy violations have been reported (both informally and formally), (2) how many reports are currently under investigation, and (3) how many have been adjudicated, along with general descriptions of any disciplinary actions taken, should be shared with the entire academic community: students, trainees, faculty, administrators, staff, alumni, and funders. At the very least, the results of the investigation and any disciplinary action should be shared with the target(s) and/or the person(s) who reported the behavior.

- Academic institutions should be accountable for the climate within their organization. In particular, they should utilize climate surveys to further investigate and address systemic sexual harassment, particularly when surveys indicate specific schools or facilities have high rates of harassment or chronically fail to reduce rates of sexual harassment.

- Academic institutions should consider sexual harassment equally important as research misconduct in terms of its effect on the integrity of research. They should increase collaboration among offices that oversee the integrity of research (i.e., those that cover ethics, research misconduct, diversity, and harassment issues); centralize resources, information, and expertise; provide more resources for handling complaints and working with targets; and implement sanctions on researchers found guilty of sexual harassment.

RECOMMENDATION 5: Diffuse the hierarchical and dependent relationship between trainees and faculty.

Academic institutions should consider power-diffusion mechanisms (i.e., mentoring networks or committee-based advising and departmental funding rather than funding only from a principal investigator) to reduce the risk of sexual harassment.

RECOMMENDATION 6: Provide support for the target.

Academic institutions should convey that reporting sexual harassment is an honorable and courageous action. Regardless of a target filing a formal report, academic institutions should provide means of accessing support services (social services, health care, legal, career/professional). They should provide alternative and less formal means of recording information about the experience and reporting the experience if the target is not comfortable filing a formal report. Academic institutions should develop approaches to prevent the target from experiencing or fearing retaliation in academic settings.

RECOMMENDATION 7: Strive for strong and diverse leadership.

- College and university presidents, provosts, deans, department chairs, and program directors must make the reduction and prevention of sexual

harassment an explicit goal of their tenure. They should publicly state that the reduction and prevention of sexual harassment will be among their highest priorities, and they should engage students, faculty, and staff (and, where appropriate, the local community) in their efforts.

- Academic institutions should support and facilitate leaders at every level (university, school/college, department, lab) in developing skills in leadership, conflict resolution, mediation, negotiation, and de-escalation, and should ensure a clear understanding of policies and procedures for handling sexual harassment issues. Additionally, these skills development programs should be customized to each level of leadership.

- Leadership training programs for those in academia should include training on how to recognize and handle sexual harassment issues, and how to take explicit steps to create a culture and climate to reduce and prevent sexual harassment—and not just protect the institution against liability.

RECOMMENDATION 8: Measure progress.

Academic institutions should work with researchers to evaluate and assess their efforts to create a more diverse, inclusive, and respectful environment, and to create effective policies, procedures, and training programs. They should not rely on formal reports by targets for an understanding of sexual harassment on their campus.

- When organizations study sexual harassment, they should follow the valid methodologies established by social science research on sexual harassment and should consult subject-matter experts. Surveys that attempt to ascertain the prevalence and types of harassment experienced by individuals should adopt the following practices: ensure confidentiality, use validated behavioral instruments such as the Sexual Experiences Questionnaire, and avoid specifically using the term “sexual harassment” in any survey or questionnaire.

- Academic institutions should also conduct more wide-ranging assessments using measures in addition to campus climate surveys, for example, ethnography, focus groups, and exit interviews. These methods are especially important in smaller organizational units where surveys, which require more participants to yield meaningful data, might not be useful.

- Organizations studying sexual harassment in their environments should take into consideration the particular experiences of people of color and sexual- and gender-minority people, and they should utilize methods that allow them to disaggregate their data by race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and gender identity to reveal the different experiences across populations.

- The results of climate surveys should be shared publicly to encourage transparency and accountability and to demonstrate to the campus community that the institution takes the issue seriously. One option would be for academic institutions to collaborate in developing a central repository for reporting their climate data, which could also improve the ability for research to be conducted on the effectiveness of institutional approaches.

- Federal agencies and foundations should commit resources to develop a tool similar to ARC3, the Administrator-Researcher Campus Climate Collaborative, to understand and track the climate for faculty, staff, and postdoctoral fellows.

RECOMMENDATION 9: Incentivize change.

- Academic institutions should work to apply for awards from the emerging STEM Equity Achievement (SEA Change) program. 3 Federal agencies and private foundations should encourage and support academic institutions working to achieve SEA Change awards.

- Accreditation bodies should consider efforts to create diverse, inclusive, and respectful environments when evaluating institutions or departments.

- Federal agencies should incentivize efforts to reduce sexual harassment in academia by requiring evaluations of the research environment, funding research and evaluation of training for students and faculty (including bystander intervention), supporting the development and evaluation of leadership training for faculty, and funding research on effective policies and procedures.

RECOMMENDATION 10: Encourage involvement of professional societies and other organizations.

- Professional societies should accelerate their efforts to be viewed as organizations that are helping to create culture changes that reduce or prevent the occurrence of sexual harassment. They should provide support and guidance for members who have been targets of sexual harassment. They should use their influence to address sexual harassment in the scientific, medical, and engineering communities they represent and promote a professional culture of civility and respect. The efforts of the American Geophysical Union are especially exemplary and should be considered as a model for other professional societies to follow.

- Other organizations that facilitate the research and training of people in science, engineering, and medicine, such as collaborative field sites (i.e., national labs and observatories), should establish standards of behavior

3 See https://www.aaas.org/news/sea-change-program-aims-transform-diversity-efforts-stem .

and set policies, procedures, and practices similar to those recommended for academic institutions and following the examples of professional societies. They should hold people accountable for their behaviors while at their facility regardless of the person’s institutional affiliation (just as some professional societies are doing).

RECOMMENDATION 11: Initiate legislative action.

State legislatures and Congress should consider new and additional legislation with the following goals:

- Better protecting sexual harassment claimants from retaliation.

- Prohibiting confidentiality in settlement agreements that currently enable harassers to move to another institution and conceal past adjudications.

- Banning mandatory arbitration clauses for discrimination claims.

- Allowing lawsuits to be filed against alleged harassers directly (instead of or in addition to their academic employers).

- Requiring institutions receiving federal funds to publicly disclose results from campus climate surveys and/or the number of sexual harassment reports made to campuses.

- Requesting the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health devote research funds to doing a follow-up analysis on the topic of sexual harassment in science, engineering, and medicine in 3 to 5 years to determine (1) whether research has shown that the prevalence of sexual harassment has decreased, (2) whether progress has been made on implementing these recommendations, and (3) where to focus future efforts.

RECOMMENDATION 12: Address the failures to meaningfully enforce Title VII’s prohibition on sex discrimination.

- Judges, academic institutions (including faculty, staff, and leaders in academia), and administrative agencies should rely on scientific evidence about the behavior of targets and perpetrators of sexual harassment when assessing both institutional compliance with the law and the merits of individual claims.

- Federal judges should take into account demonstrated effectiveness of anti-harassment policies and practices such as trainings, and not just their existence , for use of an affirmative defense against a sexual harassment claim under Title VII.

RECOMMENDATION 13: Increase federal agency action and collaboration.

Federal agencies should do the following:

- Increase support for research and evaluation of the effectiveness of policies, procedures, and training on sexual harassment.

- Attend to sexual harassment with at least the same level of attention and resources as devoted to research misconduct. They should increase collaboration among offices that oversee the integrity of research (i.e., those that cover ethics, research misconduct, diversity, and harassment issues); centralize resources, information, and expertise; provide more resources for handling complaints and working with targets; and implement sanctions on researchers found guilty of sexual harassment.

- Require institutions to report to federal agencies when individuals on grants have been found to have violated sexual harassment policies or have been put on administrative leave related to sexual harassment, as the National Science Foundation has proposed doing. Agencies should also hold accountable the perpetrator and the institution by using a range of disciplinary actions that limit the negative effects on other grant personnel who were either the target of the harassing behavior or innocent bystanders.

- Reward and incentivize colleges and universities for implementing policies, programs, and strategies that research shows are most likely to and are succeeding in reducing and preventing sexual harassment.

RECOMMENDATION 14: Conduct necessary research.

Funders should support the following research:

- The sexual harassment experiences of women in underrepresented and/or vulnerable groups, including women of color, disabled women, immigrant women, sexual- and gender-minority women, postdoctoral trainees, and others.

- Policies, procedures, trainings, and interventions, specifically their ability to prevent and stop sexually harassing behavior, to alter perception of organizational tolerance for sexually harassing behavior, and to reduce the negative consequences from reporting the incidents. This should include research on informal and formal reporting mechanisms, bystander intervention training, academic leadership training, sexual harassment and diversity training, interventions to improve civility, mandatory reporting requirements, and approaches to supporting and improving communication with the target.

- Approaches for mitigating the negative impacts and outcomes that targets experience.

- The prevalence and nature of sexual harassment within specific fields in

science, engineering, and medicine and that follows good practices for sexual harassment surveys.

- The prevalence and nature of sexual harassment perpetrated by students on faculty.

- The amount of sexual harassment that serial harassers are responsible for.

- The prevalence and effect of ambient harassment in the academic setting.

- The connections between consensual relationships and sexual harassment.

- Psychological characteristics that increase the risk of perpetrating different forms of sexually harassing behaviors.

RECOMMENDATION 15: Make the entire academic community responsible for reducing and preventing sexual harassment.

All members of our nation’s college campuses—students, trainees, faculty, staff, and administrators—as well as members of research and training sites should assume responsibility for promoting civil and respectful education, training, and work environments, and stepping up and confronting those whose behaviors and actions create sexually harassing environments.

This page intentionally left blank.

Over the last few decades, research, activity, and funding has been devoted to improving the recruitment, retention, and advancement of women in the fields of science, engineering, and medicine. In recent years the diversity of those participating in these fields, particularly the participation of women, has improved and there are significantly more women entering careers and studying science, engineering, and medicine than ever before. However, as women increasingly enter these fields they face biases and barriers and it is not surprising that sexual harassment is one of these barriers.

Over thirty years the incidence of sexual harassment in different industries has held steady, yet now more women are in the workforce and in academia, and in the fields of science, engineering, and medicine (as students and faculty) and so more women are experiencing sexual harassment as they work and learn. Over the last several years, revelations of the sexual harassment experienced by women in the workplace and in academic settings have raised urgent questions about the specific impact of this discriminatory behavior on women and the extent to which it is limiting their careers.

Sexual Harassment of Women explores the influence of sexual harassment in academia on the career advancement of women in the scientific, technical, and medical workforce. This report reviews the research on the extent to which women in the fields of science, engineering, and medicine are victimized by sexual harassment and examines the existing information on the extent to which sexual harassment in academia negatively impacts the recruitment, retention, and advancement of women pursuing scientific, engineering, technical, and medical careers. It also identifies and analyzes the policies, strategies and practices that have been the most successful in preventing and addressing sexual harassment in these settings.

READ FREE ONLINE

Welcome to OpenBook!

You're looking at OpenBook, NAP.edu's online reading room since 1999. Based on feedback from you, our users, we've made some improvements that make it easier than ever to read thousands of publications on our website.

Do you want to take a quick tour of the OpenBook's features?

Show this book's table of contents , where you can jump to any chapter by name.

...or use these buttons to go back to the previous chapter or skip to the next one.

Jump up to the previous page or down to the next one. Also, you can type in a page number and press Enter to go directly to that page in the book.

Switch between the Original Pages , where you can read the report as it appeared in print, and Text Pages for the web version, where you can highlight and search the text.

To search the entire text of this book, type in your search term here and press Enter .

Share a link to this book page on your preferred social network or via email.

View our suggested citation for this chapter.

Ready to take your reading offline? Click here to buy this book in print or download it as a free PDF, if available.

Get Email Updates

Do you enjoy reading reports from the Academies online for free ? Sign up for email notifications and we'll let you know about new publications in your areas of interest when they're released.

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

- Sexual Harassment at Work in the Era of #MeToo

Many see new difficulties for men in workplace interactions and little effect on women’s career opportunities

Table of contents.

- Acknowledgments

- Methodology

Recent allegations against prominent men in entertainment, politics, the media and other industries have sparked increased attention to the issue of sexual harassment and assault, in turn raising questions about the treatment of the accused and the accusers and what lies ahead for men and women in the workplace .

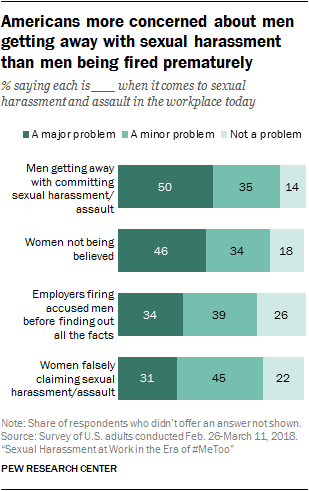

A new Pew Research Center survey finds that, when it comes to sexual harassment in the workplace, more Americans think men getting away with it and female accusers not being believed are major problems than say the same about employers firing men before finding out all the facts or women making false accusations. And while these attitudes differ somewhat by gender, they vary most dramatically between Democrats and Republicans.

The nationally representative survey of 6,251 adults was conducted online Feb. 26-March 11, 2018, using Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel . 1

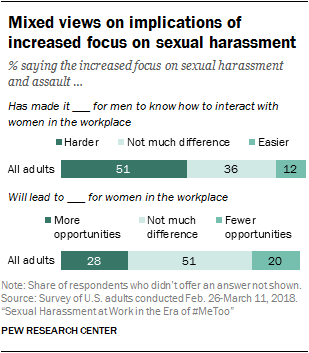

Many Americans also believe the increased focus on sexual harassment and assault poses new challenges for men as they navigate their interactions with women at work. About half (51%) say the recent developments have made it harder for men to know how to interact with women in the workplace. Only 12% say this increased focus has made it easier for men, and 36% say it hasn’t made much difference.

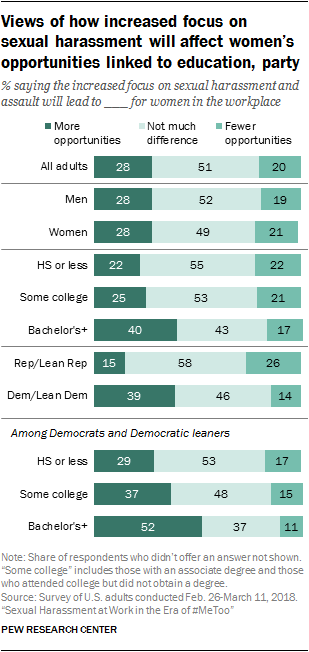

At the same time, Americans see little upside for women’s workplace opportunities as a result of the increased focus on sexual harassment and assault. Just 28% say it will lead to more opportunities for women in the workplace in the long run, while a somewhat smaller share (20%) say it will lead to fewer opportunities and 51% say it won’t make much of a difference.

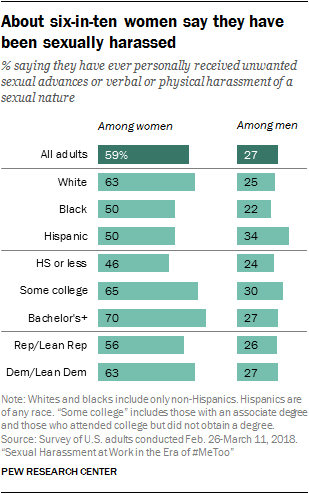

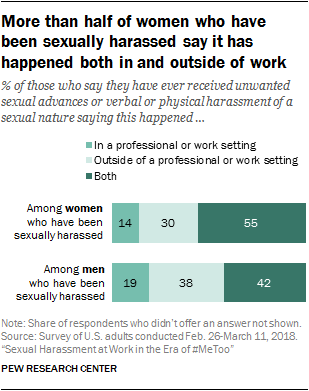

The survey also finds that 59% of women and 27% of men say they have personally received unwanted sexual advances or verbal or physical harassment of a sexual nature, whether in or outside of a work context. Among women who say they have been sexually harassed, more than half (55%) say it has happened both in and outside of work settings.

Large partisan gaps in concerns about men getting away with sexual harassment and women not being believed

When asked about sexual harassment and sexual assault in the workplace today, half of Americans think that men getting away with this type of behavior is a major problem. Similarly, 46% see women not being believed when they claim they have experienced sexual harassment or assault as a major problem.

Smaller shares see premature firings (34%) and false claims of sexual harassment or assault (31%) as major problems.

In general, women are more likely than men to be concerned about sexual harassment going unpunished and victims not being believed. Some 52% of women say that women not being believed is a major problem, compared with 39% of men. And while a 55% majority of women think that men getting away with sexual harassment is a major problem, 44% of men say the same. Men and women express similar levels of concern over employers firing men who have been accused of sexual harassment before knowing all the facts and about women making false claims of sexual harassment.

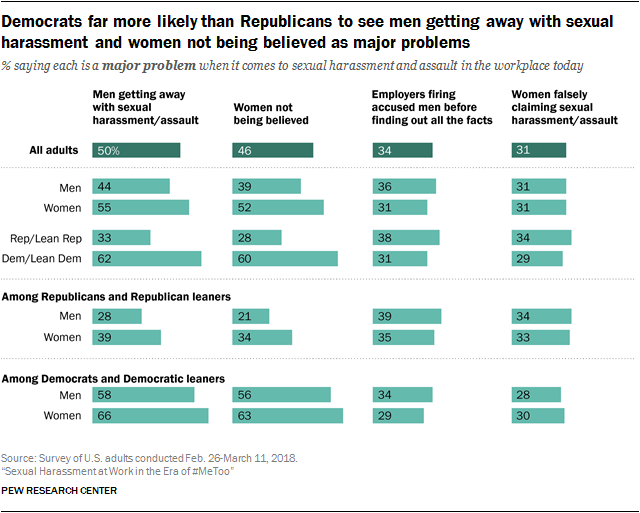

Concerns about sexual harassment in the workplace vary even more widely along partisan lines when it comes to men getting away with it and women not being believed. About six-in-ten Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents say that men getting away with sexual harassment (62%) and women not being believed when they claim they have experienced it (60%) are major problems. By contrast, just 33% of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents see men getting away with it as a major problem, and 28% say the same about women not being believed.

Because the gender gap exists within each party coalition, this leaves Democratic women as the most concerned and Republican men as the least on both of these questions. For example, 63% of Democratic women and 56% of Democratic men say that women not being believed is a major problem, compared with 34% of Republican women and 21% of Republican men.

Conversely, Republicans are somewhat more likely than Democrats to say that employers prematurely firing men accused of sexual harassment is a major problem (38% vs. 31%) and to say the same about women falsely claiming they have experienced sexual harassment (34% vs. 29%).

Democrats who describe their political views as liberal express particularly high levels of concern about men getting away with sexual harassment (71% vs. 55% of moderate or conservative Democrats say this is a major problem) and women not being believed (67% vs. 54%). In contrast, moderate or conservative Democrats are more likely than their liberal counterparts to express concern about men accused of sexual harassment being fired prematurely and women making false accusations. A similar pattern is evident among Democrats with at least a bachelor’s degree and those with less education. For example, 39% of Democrats with a high school diploma or less education see employers firing accused men prematurely as a major problem, compared with 32% of those with some college experience and 22% of those with at least a bachelor’s degree. Differences by ideology and educational level tend to be less pronounced among Republicans.

Older adults, Republicans more likely to say increased focus on sexual harassment has made it harder for men to know how to interact with women in the workplace

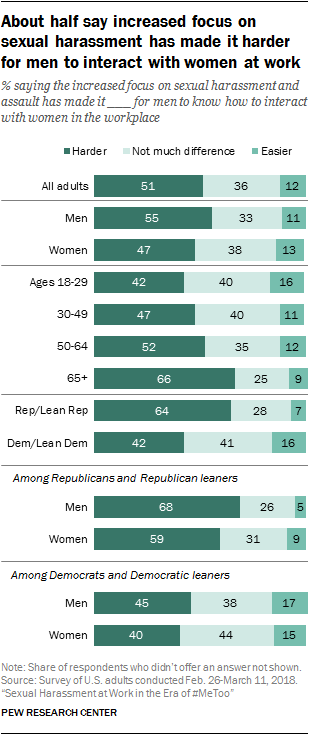

Many Americans see the increased focus on sexual harassment and assault as potentially creating challenges for men at work while not necessarily having a positive impact for women in terms of career opportunities. About half (51%) think the increased attention to the issue has made it harder for men to know how to interact with women in the workplace, while 12% say it’s made it easier for men and 36% say it hasn’t made much difference.

At least a plurality of men (55%) and women (47%) say the recent developments have made it harder for men to navigate workplace interactions. There is a large partisan gap on this question, however, with Republicans and Republican-leaning independents far more likely than Democrats and Democratic leaners to say the increased focus on sexual harassment and assault has made it harder for men to know how to interact with women in the workplace. Most Republicans (64%) say this is the case, compared with 42% of Democrats.

Republican men are particularly likely to express this view: 68% say workplace interactions with women are harder now, compared with a narrower majority of Republican women (59%). Democratic men and women are both far less likely to say the same (45% and 40%, respectively).

There is a significant age gap on this question as well. Among adults ages 65 and older, about two-thirds (66%) say the heightened attention has made navigating workplace interactions more difficult for men. By comparison, 52% of those ages 50 to 64, 47% of those 30 to 49 and 42% of those younger than 30 say the same.

Roughly half of all adults say the increased focus on sexual harassment will have little impact on women’s career opportunities

A relatively small share of Americans think the increased focus on sexual harassment and assault will lead to more opportunities for women in the workplace in the long run. Roughly three-in-ten (28%) expect this outcome, while 20% believe this will lead to fewer opportunities for women and 51% say it won’t make much difference. Men and women express similar views on this question.

Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents are far more likely than Republicans and Republican leaners to say women will have more opportunities in the workplace in the long run as a result of the increased focus on sexual harassment. About four-in-ten Democrats (39%) say this, compared with just 15% of Republicans. Liberal Democrats are especially likely to hold this view – about half (48%) think the increased attention to sexual harassment will lead to more opportunities for women, while about three-in-ten moderate or conservative Democrats (31%) say the same.

Among Democrats, views on this issue vary by educational attainment. About half of Democrats with a bachelor’s degree or more education (52%) think this increased focus will lead to more opportunities for women, compared with 37% of those with some college experience and 29% of those with a high school education or less.

About six-in-ten women say they have received unwanted sexual advances or experienced sexual harassment

Some 44% of Americans say they have received unwanted sexual advances or verbal or physical harassment of a sexual nature. About six-in-ten women (59%) say they have experienced this, while 27% of men say the same.

Among women, those with at least some college education are far more likely than those with less education to say they have experienced sexual harassment. Seven-in-ten women with a bachelor’s degree or more education and 65% of women with some college but no bachelor’s degree say they have been sexually harassed, compared with 46% of women with a high school education or less.

Reports of unwanted sexual advances or sexual harassment are also more common among white women: 63% in this group say this has happened to them, compared with half of black and Hispanic women. The shares of women saying they have been sexually harassed are largely similar across age groups.

While somewhat higher shares of Democratic than Republican women say they have received unwanted sexual advances or experienced sexual harassment, majorities of both groups say this has happened to them (63% vs. 56%).

Among women who say they have received unwanted sexual advances or experienced sexual harassment, more than half (55%) say this has happened to them both in and outside of a professional or work setting. Overall, 69% of women who say they have experienced sexual harassment say this happened in a professional or work setting; 85% say they have experienced this outside of work.

Among men who say they have been sexually harassed, roughly four-in-ten (42%) say they experienced it both in and out of work situations. Overall, about six-in-ten men who say they have been sexually harassed (61%) say it happened in a professional or work setting; 80% say they experienced this outside of a work situation.

Men and women who say they have experienced sexual harassment are more likely than their counterparts to say that men getting away with sexual harassment or assault is a major problem. Fully 61% of women and 51% of men who say they have experienced sexual harassment hold this view, compared with 46% of women and 41% of men who say they have not been sexually harassed.

On other concerns related to sexual harassment in the workplace, the views of men do not vary by whether they report experiencing sexual harassment or not. Among women, however, the experience of sexual harassment is linked to concerns about this issue. For example, 58% of women who say they have experienced sexual harassment say that women not being believed is a major problem when it comes to sexual harassment in the workplace, compared with 43% of women who do not report having been sexually harassed.

All references to party affiliation include those who lean toward that party: Republicans include those who identify as Republicans and independents who say they lean toward the Republican Party, and Democrats include those who identify as Democrats and independents who say they lean toward the Democratic Party.

References to college graduates or people with a college degree comprise those with a bachelor’s degree or more. “Some college” includes those with an associate degree and those who attended college but did not obtain a degree. “High school” refers to those who have a high school diploma or its equivalent, such as a General Education Development (GED) certificate.

References to whites and blacks include only those who are non-Hispanic and identify as only one race. Hispanics are of any race.

- For more details, see the Methodology section of the report. ↩

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Business & Workplace

- Economics, Work & Gender

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Gender & Work

- Sexual Misconduct & Harassment

Half of Latinas Say Hispanic Women’s Situation Has Improved in the Past Decade and Expect More Gains

A majority of latinas feel pressure to support their families or to succeed at work, a look at small businesses in the u.s., majorities of adults see decline of union membership as bad for the u.s. and working people, a look at black-owned businesses in the u.s., most popular, report materials.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Sexual Harassment in Workplace: A Literature Review

- Related Documents

Pendidikan Seksual Anak Usia Dini: "My Bodies Belong To Me"

Early childhood sexual education is an important thing that can be provided to children starting as early as possible. From the rampant phenomena of cases of violence and sexual harassment that often occur, this article can be a guide for readers in providing sexual education to children by paying attention to the stages of child development. This article can increase knowledge for parents in conducting sexual education about their bodies so that children can take care of themselves and prevent increasing cases of irregularities around the child. With the literature review method using various sources of research results that have been done, this article can be a reference for parents in developing knowledge about early childhood sexual education. This article explains the method of knowing the body and the rules of underwear that are packed with attention to cognitive development, communication and sexuality of children. Parents can use strategies using various methods such as storytelling, discussion or question and answer and utilizing audio, visual and audio visual communication media such as pictures, videos and songs.

A Systematic Literature Review of Sexual Harassment Studies with Text Mining

Sexual harassment has been the topic of thousands of research articles in the 20th and 21st centuries. Several review papers have been developed to synthesize the literature about sexual harassment. While traditional literature review studies provide valuable insights, these studies have some limitations including analyzing a limited number of papers, being time-consuming and labor-intensive, focusing on a few topics, and lacking temporal trend analysis. To address these limitations, this paper employs both computational and qualitative approaches to identify major research topics, explore temporal trends of sexual harassment topics over the past few decades, and point to future possible directions in sexual harassment studies. We collected 5320 research papers published between 1977 and 2020, identified and analyzed sexual harassment topics, and explored the temporal trend of topics. Our findings indicate that sexual harassment in the workplace was the most popular research theme, and sexual harassment was investigated in a wide range of spaces ranging from school to military settings. Our analysis shows that 62.5% of the topics having a significant trend had an increasing (hot) temporal trend that is expected to be studied more in the coming years. This study offers a bird’s eye view to better understand sexual harassment literature with text mining, qualitative, and temporal trend analysis methods. This research could be beneficial to researchers, educators, publishers, and policymakers by providing a broad overview of the sexual harassment field.

PANCASILA IN THE GLOBAL ERA

Introduction: Fading of the Pancasila values in social life now has a very bad impact on citizens in Indonesia, including the number of brawls between residents triggered by trivial problems, then cases of religious blasphemy, and criminal crimes. In the name of religion, then the existence of terrorism, sexual harassment and many others. This study aims to find out what the existence of Pancasila values and the application of today's globalization era looks like. Method : This research is using literature review from publications regarding the corresponding topic, along with determined criteria. As is well known, Results : Pancasila is the basis of the Indonesian state, and becomes the guide for all Indonesian people. As it is known that with the existence of Pancasila, all Indonesian people have guideline values in recognizing and solving problems such as politics, social, cultural, religious and others. However, in reality, the value of Pancasila is now starting to fade in social life. This situation can be seen with the many problems that have emerged lately, such as bombing places of worship, the emergence of terrorism activities and so on. If the problems like this are not resolved immediately it will eliminate the value and the meaning of the state guideline, namely Pancasila. Conslusion : This situation can be observed from the emergence of various kinds of problems arising from not applying the values of Pancasila, and if they are not immediately resolved, the values of Pancasila or the meaning of Pancasila may disappear itself. Suggestion : To counteract all the negative impacts of globalization, Indonesian people only need to hold, and actualize the values of Pancasila properly and correctly.

Strategies to prevent sexual harassment & abuse(SHA) in Taekwondo: via literature review on sports related SHA

Effect of computerized auditory training on speech perception of adults with hearing impairment.

Computerized auditory training (CAT) is a convenient, low-cost approach to improving communication of individuals with hearing loss or other communicative disorders. A number of CAT programs are being marketed to patients and audiologists. The present literature review is an examination of evidence for the effectiveness of CAT in improving speech perception in adults with hearing impairments. Six current CAT programs, used in 9 published studies, were reviewed. In all 9 studies, some benefit of CAT for speech perception was demonstrated. Although these results are encouraging, the overall quality of available evidence remains low, and many programs currently on the market have not yet been evaluated. Thus, caution is needed when selecting CAT programs for specific patients. It is hoped that future researchers will (a) examine a greater number of CAT programs using more rigorous experimental designs, (b) determine which program features and training regimens are most effective, and (c) indicate which patients may benefit from CAT the most.

Taking Care of Children After Traumatic Brain Injury

AbstractPurpose: The purpose of this article is to inform speech-language pathologists in the schools about issues related to the care of children with traumatic brain injury.Method: Literature review of characteristics, outcomes and issues related to the needs serving children.Results: Due to acquired changes in cognition, children with traumatic brain injury have unique needs in a school setting.Conclusions: Speech-Language Pathologists in the school can take a leadership role with taking care of children after a traumatic brain injury and coordination of medical and educational information.

Sexual harassment during medical training: the perceptions of medical students at a university medical school in Australia

Literature review, export citation format, share document.

- Search UNH.edu

- Search Carsey School of Public Policy

Commonly Searched Items:

- Academic Calendar

- Masters Programs

- Accelerated Masters

- Executive Education

- Continuing Education

- Grad Certificate Programs

- Changemaker Collaborative

- Student Experience

- Online Experience

- Application Checklist: How to Apply

- Paying For School

- Schedule a Campus Visit

- Concentrations & Tools

- Publications

- Carsey Policy Hour

- Coffee & Conversations Archive

- Communications

- Working With Us

Half of Women in New Hampshire Have Experienced Sexual Harassment at Work

- Kristin Smith

- Sharyn Potter

- Jane Stapleton

download the brief

Key findings.

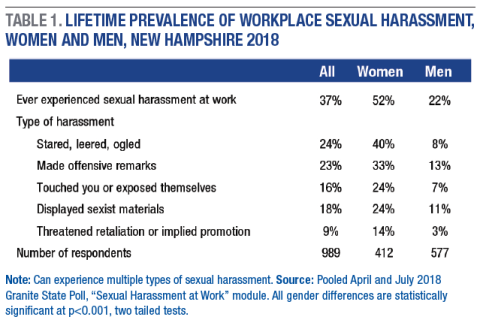

Over half of women and nearly one-quarter of men in New Hampshire have been victims of sexual harassment at their workplaces during their lifetimes.

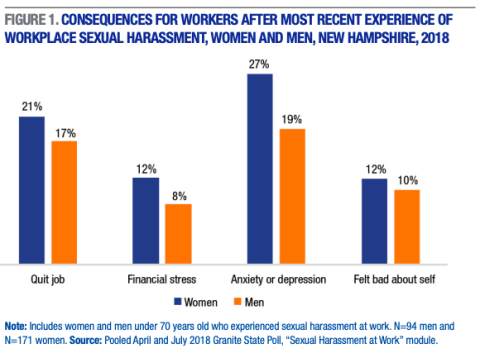

Women are more likely to state they suffered work-related consequences (for example, financial loss, being fired or demoted) than men (33 percent and 25 percent, respectively), but similar shares reported quitting their jobs as a result of the harassment (21 percent and 17 percent, respectively).

Sexual harassment in the workplace is a serious problem affecting workers across the United States and in New Hampshire. Nationwide, approximately four in ten women and more than one in ten men have been victims of workplace sexual harassment in their lifetimes. 1 Research shows that such harassment has lasting economic, health, and family-related consequences for victims and their families: it increases victims’ job exits and financial stress, alters career paths, and has deleterious consequences for mental and physical health, including depression, anger, and self-doubt. 2

In New Hampshire, more than half of women (52 percent) and nearly one quarter of men (22 percent) have been victims of sexual harassment at work during their lifetimes (Table 1), 3 and women are more likely than men to have experienced any type of sexual harassment. Four in ten women reported being stared at, leered at, or ogled in a way that made them feel uncomfortable; one-third reported that coworkers had made offensive remarks about their appearance, body, or sexual activities; and about one-quarter (24 percent) reported that they were touched in an uncomfortable way or that someone exposed themselves physically while they were at work. About one-quarter of women reported that others displayed, used, or distributed sexist materials while at work; and over 10 percent reported that others threatened retaliation for not being sexually cooperative or implied faster promotion for being sexually cooperative. Just over 10 percent of men reported that coworkers made offensive remarks about their appearance, body, or sexual activities or that others displayed, used, or distributed sexist materials while at work; just under 10 percent of men reported experiencing other types of workplace sexual harassment.

Women More Likely to Suffer Work-Related Consequences Than Men

The detrimental consequences of workplace sexual harassment can be multifaceted and lasting, with negative effects on victims, their families, and workplaces. Victims of workplace sexual harassment suffer work-related consequences, including quitting their job, being fired or demoted, experiencing a voluntary or involuntary work transfer, taking leave, or having their work schedule modified. When asked to consider their most recent sexual harassment experience, women in the New Hampshire survey were more likely to state they suffered a work-related consequence than men (33 percent and 25 percent, respectively); however, the sample sizes are small and should be interpreted with caution. About one-fifth of women and men reported quitting their jobs in response to recent sexual harassment victimization (21 percent and 17 percent, respectively; Figure 1). Both women and men in New Hampshire reported financial stress due to sexual harassment (about 10 percent of each), according with existing research that shows a strong link between workplace sexual harassment and financial stress, largely due to job change, either voluntary or forced. 4

Sexual harassment negatively impacts victims’ physical and mental health, causing anxiety, depression, and diminished self-esteem, self-confidence, and psychological well-being. A higher proportion of women reported anxiety or depression than men as a result of the most recent sexual harassment victimization (27 percent and 19 percent, respectively); however, the sample sizes are small and should be interpreted with caution . Similar proportions of women and men reported feeling bad about themselves (about 10 percent each).

Sexual harassment is problematic for the workplace, as it reduces worker morale and job satisfaction, diminishes productivity, and increases absenteeism and worker withdrawal. It can be indicative of a toxic environment if employers fail to address harassers or protect victims. 5 Employers would do well to invest in prevention, such as bystander intervention training, and encourage victims’ use of supports to mitigate the negative effects of workplace sexual harassment. 6

The data used in this analysis were collected in the Granite State Poll (GSP) in April and July 2018. The GSP, a random-digit-dialing telephone survey administered by the University of New Hampshire Survey Center, provides a statewide representative sample of approximately 500 households and collects demographic, economic, and employment information. The authors developed a Sexual Harassment at Work Topical Module that was added to the GSP based on established definitions of sexual harassment at work in previous studies, including the National Study on Sexual Harassment and Assault Study, the Youth Development Study, and the SEQ: DoD Study. For a full definition of workplace sexual harassment, with examples, see the United Nations report . All analyses are weighted using household-level weights provided by the UNH Survey Center based on U.S. Census Bureau estimates of the New Hampshire population.

1 . Holly Kearl, “The Facts Behind the #metoo Movement: A National Study on Sexual Harassment and Assault” (Reston, VA: Stop Street Harassment, 2018).

2. Heather McLaughlin, Christopher Uggen, and Amy Blackstone, “The Economic and Career Effects of Sexual Harassment on Working Women,” Gender & Society 31, no. 3 (2017): 333–58; Jason Houle et al., “The Impact of Sexual Harassment on Depressive Symptoms During the Early Occupational Career,” Society and Mental Health 1 (2011): 89–105.

3. Since 2007, University of New Hampshire Prevention Innovation Research Center researchers have engaged in research on sexual assault, relationship violence, stalking, harassment, and emotional abuse in New Hampshire. See D. Laflamme, G. Mattern, M. Moynihan, and S.J. Potter, “Sexual Assault in New Hampshire: A Report from the New Hampshire Coalition Against Domestic and Sexual Violence” (2011), https://www.nhcadsv.org/uploads/1/0/7/5/107511883/sexualassaultinnh.pdf (authors listed alphabetically) ; D. Laflamme, G. Mattern, M. Moynihan, and S.J. Potter, ”Violence Against Men in New Hampshire” (2009), https://www.nhcadsv.org/uploads/1/0/7/5/107511883/vam_report_final.pdf (authors listed alphabetically) ; V. Banyard, L. Bujno, D. Laflamme, G. Mattern, M. Moynihan, and S.J. Potter, “Violence Against Women in New Hampshire” (2007), https://www.nhcadsv.org/uploads/1/0/7/5/107511883/vaw_report_final.pdf (authors listed alphabetically) .

4. McLaughlin et al., 2017.

5. Victoria L. Banyard, Sharyn J. Potter, and Heather Turner, “The Impact of Interpersonal Violence in Adulthood on Women’s Job Satisfaction and Productivity: The Mediating Roles of Mental and Physical Health,” Psychology of Violence 1 (2011): 16–28; Victoria L. Banyard and Sharyn J. Potter, “Victimization in the Lives of Employed Women: Disclosure in the Workplace,” Family and Intimate Partner Violence Quarterly 3 (2010): 1–20; Chelsea Willness, Piers Steel, and Kibeom Lee, “A Meta-Analysis of the Antecedents and Consequences of Workplace Sexual Harassment,” Personnel Psychology 60 (2007): 127–62.

6. Sharyn J. Potter and Jane G. Stapleton, “Sexual Harassment in the Workplace: The Importance of Cultural Change,” Business NH Magazine, January 2018, p. 52.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Carsey School of Public Policy and the Prevention Innovations Research Center . The authors would like to thank Michael Ettlinger, Curt Grimm, Michele Dillon, Marybeth Mattingly, Laurel Lloyd, and Bianca Nicolosi at the Carsey School of Public Policy; Jennifer Scrafford, Caroline Leyva, Laurie Dawe, and Taylor Flagg at the Prevention Innovations Research Center; and Patrick Watson for his editorial assistance.

- New Hampshire

- Vulnerable Families Research Program

Carsey School of Public Policy

- Carsey Stories: Local Community Development

- Carsey Stories: From Ukraine to Durham

- Carsey Stories: Community Capstone Project

- Carsey Stories: Expanding Horizons

- Carsey Stories: A Degree for Working Professionals

- Carsey Stories: Careers in Nonprofit Management

- Carsey Stories: Different Perspectives

- Master of Global Conflict and Human Security (Online)

- Carsey Stories: A Flexible Degree Program

- Carsey Stories: A Calling to Civic Leadership

- Carsey Stories: Earning Your Degree Your Way

- Carsey Stories: Leveraging Education for a Late-Career Move

- Carsey Stories: Serving Others Through Affordable Housing

- Carsey Stories: Building Skills

- Carsey Stories: It's All Worth It!

- Carsey Stories: Communicating Policy

- Carsey Stories: Say "Yes!" to Opportunity

- Carsey Stories: Sustainable Solutions

- Carsey Stories: Just Do It!

- Carsey Stories: Representing

- Carsey Stories: Intern Working Against Internment in Washington, D.C.

- Carsey Stories: Dreams Fulfilled

- Master in Public Policy and Juris Doctor Dual Degree MPP/JD

- The Judge William W. Treat Fellowship

- Governor John G. Winant Fellowship

- Master in Public Policy Fellowships

- S. Melvin Rines Fellowship (MCD Students)

- Meet Our Alumni

- Meet Our Students

- Meet Our Faculty

- 2023 Washington, D.C., Colloquium Highlights

- Master in Community Development Capstone Projects

- Master of Public Administration Capstone Projects

- Recorded Information Sessions

- Upcoming Information Sessions

- City of Concord Employee Award

- Coverdell Fellowship Award

- First Responders Education Award

- Inclusiv Education Award

- LISC Employee Award

- NALCAB Education Award

- National Development Council Award

- NeighborWorks Award

- OFN Employee Award