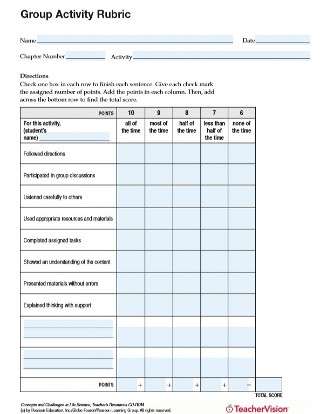

Assessment Rubrics

A rubric is commonly defined as a tool that articulates the expectations for an assignment by listing criteria, and for each criteria, describing levels of quality (Andrade, 2000; Arter & Chappuis, 2007; Stiggins, 2001). Criteria are used in determining the level at which student work meets expectations. Markers of quality give students a clear idea about what must be done to demonstrate a certain level of mastery, understanding, or proficiency (i.e., "Exceeds Expectations" does xyz, "Meets Expectations" does only xy or yz, "Developing" does only x or y or z). Rubrics can be used for any assignment in a course, or for any way in which students are asked to demonstrate what they've learned. They can also be used to facilitate self and peer-reviews of student work.

Rubrics aren't just for summative evaluation. They can be used as a teaching tool as well. When used as part of a formative assessment, they can help students understand both the holistic nature and/or specific analytics of learning expected, the level of learning expected, and then make decisions about their current level of learning to inform revision and improvement (Reddy & Andrade, 2010).

Why use rubrics?

Rubrics help instructors:

Provide students with feedback that is clear, directed and focused on ways to improve learning.

Demystify assignment expectations so students can focus on the work instead of guessing "what the instructor wants."

Reduce time spent on grading and develop consistency in how you evaluate student learning across students and throughout a class.

Rubrics help students:

Focus their efforts on completing assignments in line with clearly set expectations.

Self and Peer-reflect on their learning, making informed changes to achieve the desired learning level.

Developing a Rubric

During the process of developing a rubric, instructors might:

Select an assignment for your course - ideally one you identify as time intensive to grade, or students report as having unclear expectations.

Decide what you want students to demonstrate about their learning through that assignment. These are your criteria.

Identify the markers of quality on which you feel comfortable evaluating students’ level of learning - often along with a numerical scale (i.e., "Accomplished," "Emerging," "Beginning" for a developmental approach).

Give students the rubric ahead of time. Advise them to use it in guiding their completion of the assignment.

It can be overwhelming to create a rubric for every assignment in a class at once, so start by creating one rubric for one assignment. See how it goes and develop more from there! Also, do not reinvent the wheel. Rubric templates and examples exist all over the Internet, or consider asking colleagues if they have developed rubrics for similar assignments.

Sample Rubrics

Examples of holistic and analytic rubrics : see Tables 2 & 3 in “Rubrics: Tools for Making Learning Goals and Evaluation Criteria Explicit for Both Teachers and Learners” (Allen & Tanner, 2006)

Examples across assessment types : see “Creating and Using Rubrics,” Carnegie Mellon Eberly Center for Teaching Excellence and & Educational Innovation

“VALUE Rubrics” : see the Association of American Colleges and Universities set of free, downloadable rubrics, with foci including creative thinking, problem solving, and information literacy.

Andrade, H. 2000. Using rubrics to promote thinking and learning. Educational Leadership 57, no. 5: 13–18. Arter, J., and J. Chappuis. 2007. Creating and recognizing quality rubrics. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Merrill Prentice Hall. Stiggins, R.J. 2001. Student-involved classroom assessment. 3rd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Reddy, Y., & Andrade, H. (2010). A review of rubric use in higher education. Assessment & Evaluation In Higher Education, 35(4), 435-448.

Rubric Best Practices, Examples, and Templates

A rubric is a scoring tool that identifies the different criteria relevant to an assignment, assessment, or learning outcome and states the possible levels of achievement in a specific, clear, and objective way. Use rubrics to assess project-based student work including essays, group projects, creative endeavors, and oral presentations.

Rubrics can help instructors communicate expectations to students and assess student work fairly, consistently and efficiently. Rubrics can provide students with informative feedback on their strengths and weaknesses so that they can reflect on their performance and work on areas that need improvement.

How to Get Started

Best practices, moodle how-to guides.

- Workshop Recording (Fall 2022)

- Workshop Registration

Step 1: Analyze the assignment

The first step in the rubric creation process is to analyze the assignment or assessment for which you are creating a rubric. To do this, consider the following questions:

- What is the purpose of the assignment and your feedback? What do you want students to demonstrate through the completion of this assignment (i.e. what are the learning objectives measured by it)? Is it a summative assessment, or will students use the feedback to create an improved product?

- Does the assignment break down into different or smaller tasks? Are these tasks equally important as the main assignment?

- What would an “excellent” assignment look like? An “acceptable” assignment? One that still needs major work?

- How detailed do you want the feedback you give students to be? Do you want/need to give them a grade?

Step 2: Decide what kind of rubric you will use

Types of rubrics: holistic, analytic/descriptive, single-point

Holistic Rubric. A holistic rubric includes all the criteria (such as clarity, organization, mechanics, etc.) to be considered together and included in a single evaluation. With a holistic rubric, the rater or grader assigns a single score based on an overall judgment of the student’s work, using descriptions of each performance level to assign the score.

Advantages of holistic rubrics:

- Can p lace an emphasis on what learners can demonstrate rather than what they cannot

- Save grader time by minimizing the number of evaluations to be made for each student

- Can be used consistently across raters, provided they have all been trained

Disadvantages of holistic rubrics:

- Provide less specific feedback than analytic/descriptive rubrics

- Can be difficult to choose a score when a student’s work is at varying levels across the criteria

- Any weighting of c riteria cannot be indicated in the rubric

Analytic/Descriptive Rubric . An analytic or descriptive rubric often takes the form of a table with the criteria listed in the left column and with levels of performance listed across the top row. Each cell contains a description of what the specified criterion looks like at a given level of performance. Each of the criteria is scored individually.

Advantages of analytic rubrics:

- Provide detailed feedback on areas of strength or weakness

- Each criterion can be weighted to reflect its relative importance

Disadvantages of analytic rubrics:

- More time-consuming to create and use than a holistic rubric

- May not be used consistently across raters unless the cells are well defined

- May result in giving less personalized feedback

Single-Point Rubric . A single-point rubric is breaks down the components of an assignment into different criteria, but instead of describing different levels of performance, only the “proficient” level is described. Feedback space is provided for instructors to give individualized comments to help students improve and/or show where they excelled beyond the proficiency descriptors.

Advantages of single-point rubrics:

- Easier to create than an analytic/descriptive rubric

- Perhaps more likely that students will read the descriptors

- Areas of concern and excellence are open-ended

- May removes a focus on the grade/points

- May increase student creativity in project-based assignments

Disadvantage of analytic rubrics: Requires more work for instructors writing feedback

Step 3 (Optional): Look for templates and examples.

You might Google, “Rubric for persuasive essay at the college level” and see if there are any publicly available examples to start from. Ask your colleagues if they have used a rubric for a similar assignment. Some examples are also available at the end of this article. These rubrics can be a great starting point for you, but consider steps 3, 4, and 5 below to ensure that the rubric matches your assignment description, learning objectives and expectations.

Step 4: Define the assignment criteria

Make a list of the knowledge and skills are you measuring with the assignment/assessment Refer to your stated learning objectives, the assignment instructions, past examples of student work, etc. for help.

Helpful strategies for defining grading criteria:

- Collaborate with co-instructors, teaching assistants, and other colleagues

- Brainstorm and discuss with students

- Can they be observed and measured?

- Are they important and essential?

- Are they distinct from other criteria?

- Are they phrased in precise, unambiguous language?

- Revise the criteria as needed

- Consider whether some are more important than others, and how you will weight them.

Step 5: Design the rating scale

Most ratings scales include between 3 and 5 levels. Consider the following questions when designing your rating scale:

- Given what students are able to demonstrate in this assignment/assessment, what are the possible levels of achievement?

- How many levels would you like to include (more levels means more detailed descriptions)

- Will you use numbers and/or descriptive labels for each level of performance? (for example 5, 4, 3, 2, 1 and/or Exceeds expectations, Accomplished, Proficient, Developing, Beginning, etc.)

- Don’t use too many columns, and recognize that some criteria can have more columns that others . The rubric needs to be comprehensible and organized. Pick the right amount of columns so that the criteria flow logically and naturally across levels.

Step 6: Write descriptions for each level of the rating scale

Artificial Intelligence tools like Chat GPT have proven to be useful tools for creating a rubric. You will want to engineer your prompt that you provide the AI assistant to ensure you get what you want. For example, you might provide the assignment description, the criteria you feel are important, and the number of levels of performance you want in your prompt. Use the results as a starting point, and adjust the descriptions as needed.

Building a rubric from scratch

For a single-point rubric , describe what would be considered “proficient,” i.e. B-level work, and provide that description. You might also include suggestions for students outside of the actual rubric about how they might surpass proficient-level work.

For analytic and holistic rubrics , c reate statements of expected performance at each level of the rubric.

- Consider what descriptor is appropriate for each criteria, e.g., presence vs absence, complete vs incomplete, many vs none, major vs minor, consistent vs inconsistent, always vs never. If you have an indicator described in one level, it will need to be described in each level.

- You might start with the top/exemplary level. What does it look like when a student has achieved excellence for each/every criterion? Then, look at the “bottom” level. What does it look like when a student has not achieved the learning goals in any way? Then, complete the in-between levels.

- For an analytic rubric , do this for each particular criterion of the rubric so that every cell in the table is filled. These descriptions help students understand your expectations and their performance in regard to those expectations.

Well-written descriptions:

- Describe observable and measurable behavior

- Use parallel language across the scale

- Indicate the degree to which the standards are met

Step 7: Create your rubric

Create your rubric in a table or spreadsheet in Word, Google Docs, Sheets, etc., and then transfer it by typing it into Moodle. You can also use online tools to create the rubric, but you will still have to type the criteria, indicators, levels, etc., into Moodle. Rubric creators: Rubistar , iRubric

Step 8: Pilot-test your rubric

Prior to implementing your rubric on a live course, obtain feedback from:

- Teacher assistants

Try out your new rubric on a sample of student work. After you pilot-test your rubric, analyze the results to consider its effectiveness and revise accordingly.

- Limit the rubric to a single page for reading and grading ease

- Use parallel language . Use similar language and syntax/wording from column to column. Make sure that the rubric can be easily read from left to right or vice versa.

- Use student-friendly language . Make sure the language is learning-level appropriate. If you use academic language or concepts, you will need to teach those concepts.

- Share and discuss the rubric with your students . Students should understand that the rubric is there to help them learn, reflect, and self-assess. If students use a rubric, they will understand the expectations and their relevance to learning.

- Consider scalability and reusability of rubrics. Create rubric templates that you can alter as needed for multiple assignments.

- Maximize the descriptiveness of your language. Avoid words like “good” and “excellent.” For example, instead of saying, “uses excellent sources,” you might describe what makes a resource excellent so that students will know. You might also consider reducing the reliance on quantity, such as a number of allowable misspelled words. Focus instead, for example, on how distracting any spelling errors are.

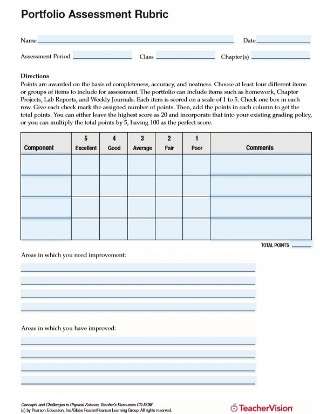

Example of an analytic rubric for a final paper

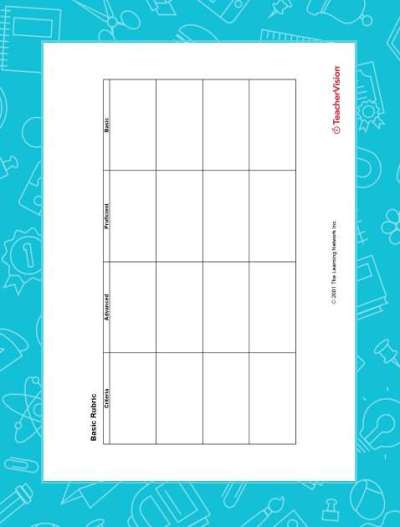

Example of a holistic rubric for a final paper, single-point rubric, more examples:.

- Single Point Rubric Template ( variation )

- Analytic Rubric Template make a copy to edit

- A Rubric for Rubrics

- Bank of Online Discussion Rubrics in different formats

- Mathematical Presentations Descriptive Rubric

- Math Proof Assessment Rubric

- Kansas State Sample Rubrics

- Design Single Point Rubric

Technology Tools: Rubrics in Moodle

- Moodle Docs: Rubrics

- Moodle Docs: Grading Guide (use for single-point rubrics)

Tools with rubrics (other than Moodle)

- Google Assignments

- Turnitin Assignments: Rubric or Grading Form

Other resources

- DePaul University (n.d.). Rubrics .

- Gonzalez, J. (2014). Know your terms: Holistic, Analytic, and Single-Point Rubrics . Cult of Pedagogy.

- Goodrich, H. (1996). Understanding rubrics . Teaching for Authentic Student Performance, 54 (4), 14-17. Retrieved from

- Miller, A. (2012). Tame the beast: tips for designing and using rubrics.

- Ragupathi, K., Lee, A. (2020). Beyond Fairness and Consistency in Grading: The Role of Rubrics in Higher Education. In: Sanger, C., Gleason, N. (eds) Diversity and Inclusion in Global Higher Education. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore.

How to Use Rubrics

A rubric is a document that describes the criteria by which students’ assignments are graded. Rubrics can be helpful for:

- Making grading faster and more consistent (reducing potential bias).

- Communicating your expectations for an assignment to students before they begin.

Moreover, for assignments whose criteria are more subjective, the process of creating a rubric and articulating what it looks like to succeed at an assignment provides an opportunity to check for alignment with the intended learning outcomes and modify the assignment prompt, as needed.

Why rubrics?

Rubrics are best for assignments or projects that require evaluation on multiple dimensions. Creating a rubric makes the instructor’s standards explicit to both students and other teaching staff for the class, showing students how to meet expectations.

Additionally, the more comprehensive a rubric is, the more it allows for grading to be streamlined—students will get informative feedback about their performance from the rubric, even if they don’t have as many individualized comments. Grading can be more standardized and efficient across graders.

Finally, rubrics allow for reflection, as the instructor has to think about their standards and outcomes for the students. Using rubrics can help with self-directed learning in students as well, especially if rubrics are used to review students’ own work or their peers’, or if students are involved in creating the rubric.

How to design a rubric

1. consider the desired learning outcomes.

What learning outcomes is this assignment reinforcing and assessing? If the learning outcome seems “fuzzy,” iterate on the outcome by thinking about the expected student work product. This may help you more clearly articulate the learning outcome in a way that is measurable.

2. Define criteria

What does a successful assignment submission look like? As described by Allen and Tanner (2006), it can help develop an initial list of categories that the student should demonstrate proficiency in by completing the assignment. These categories should correlate with the intended learning outcomes you identified in Step 1, although they may be more granular in some cases. For example, if the task assesses students’ ability to formulate an effective communication strategy, what components of their communication strategy will you be looking for? Talking with colleagues or looking at existing rubrics for similar tasks may give you ideas for categories to consider for evaluation.

If you have assigned this task to students before and have samples of student work, it can help create a qualitative observation guide. This is described in Linda Suskie’s book Assessing Student Learning , where she suggests thinking about what made you decide to give one assignment an A and another a C, as well as taking notes when grading assignments and looking for common patterns. The often repeated themes that you comment on may show what your goals and expectations for students are. An example of an observation guide used to take notes on predetermined areas of an assignment is shown here .

In summary, consider the following list of questions when defining criteria for a rubric (O’Reilly and Cyr, 2006):

- What do you want students to learn from the task?

- How will students demonstrate that they have learned?

- What knowledge, skills, and behaviors are required for the task?

- What steps are required for the task?

- What are the characteristics of the final product?

After developing an initial list of criteria, prioritize the most important skills you want to target and eliminate unessential criteria or combine similar skills into one group. Most rubrics have between 3 and 8 criteria. Rubrics that are too lengthy make it difficult to grade and challenging for students to understand the key skills they need to achieve for the given assignment.

3. Create the rating scale

According to Suskie, you will want at least 3 performance levels: for adequate and inadequate performance, at the minimum, and an exemplary level to motivate students to strive for even better work. Rubrics often contain 5 levels, with an additional level between adequate and exemplary and a level between adequate and inadequate. Usually, no more than 5 levels are needed, as having too many rating levels can make it hard to consistently distinguish which rating to give an assignment (such as between a 6 or 7 out of 10). Suskie also suggests labeling each level with names to clarify which level represents the minimum acceptable performance. Labels will vary by assignment and subject, but some examples are:

- Exceeds standard, meets standard, approaching standard, below standard

- Complete evidence, partial evidence, minimal evidence, no evidence

4. Fill in descriptors

Fill in descriptors for each criterion at each performance level. Expand on the list of criteria you developed in Step 2. Begin to write full descriptions, thinking about what an exemplary example would look like for students to strive towards. Avoid vague terms like “good” and make sure to use explicit, concrete terms to describe what would make a criterion good. For instance, a criterion called “organization and structure” would be more descriptive than “writing quality.” Describe measurable behavior and use parallel language for clarity; the wording for each criterion should be very similar, except for the degree to which standards are met. For example, in a sample rubric from Chapter 9 of Suskie’s book, the criterion of “persuasiveness” has the following descriptors:

- Well Done (5): Motivating questions and advance organizers convey the main idea. Information is accurate.

- Satisfactory (3-4): Includes persuasive information.

- Needs Improvement (1-2): Include persuasive information with few facts.

- Incomplete (0): Information is incomplete, out of date, or incorrect.

These sample descriptors generally have the same sentence structure that provides consistent language across performance levels and shows the degree to which each standard is met.

5. Test your rubric

Test your rubric using a range of student work to see if the rubric is realistic. You may also consider leaving room for aspects of the assignment, such as effort, originality, and creativity, to encourage students to go beyond the rubric. If there will be multiple instructors grading, it is important to calibrate the scoring by having all graders use the rubric to grade a selected set of student work and then discuss any differences in the scores. This process helps develop consistency in grading and making the grading more valid and reliable.

Types of Rubrics

If you would like to dive deeper into rubric terminology, this section is dedicated to discussing some of the different types of rubrics. However, regardless of the type of rubric you use, it’s still most important to focus first on your learning goals and think about how the rubric will help clarify students’ expectations and measure student progress towards those learning goals.

Depending on the nature of the assignment, rubrics can come in several varieties (Suskie, 2009):

Checklist Rubric

This is the simplest kind of rubric, which lists specific features or aspects of the assignment which may be present or absent. A checklist rubric does not involve the creation of a rating scale with descriptors. See example from 18.821 project-based math class .

Rating Scale Rubric

This is like a checklist rubric, but instead of merely noting the presence or absence of a feature or aspect of the assignment, the grader also rates quality (often on a graded or Likert-style scale). See example from 6.811 assistive technology class .

Descriptive Rubric

A descriptive rubric is like a rating scale, but including descriptions of what performing to a certain level on each scale looks like. Descriptive rubrics are particularly useful in communicating instructors’ expectations of performance to students and in creating consistency with multiple graders on an assignment. This kind of rubric is probably what most people think of when they imagine a rubric. See example from 15.279 communications class .

Holistic Scoring Guide

Unlike the first 3 types of rubrics, a holistic scoring guide describes performance at different levels (e.g., A-level performance, B-level performance) holistically without analyzing the assignment into several different scales. This kind of rubric is particularly useful when there are many assignments to grade and a moderate to a high degree of subjectivity in the assessment of quality. It can be difficult to have consistency across scores, and holistic scoring guides are most helpful when making decisions quickly rather than providing detailed feedback to students. See example from 11.229 advanced writing seminar .

The kind of rubric that is most appropriate will depend on the assignment in question.

Implementation tips

Rubrics are also available to use for Canvas assignments. See this resource from Boston College for more details and guides from Canvas Instructure.

Allen, D., & Tanner, K. (2006). Rubrics: Tools for Making Learning Goals and Evaluation Criteria Explicit for Both Teachers and Learners. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 5 (3), 197-203. doi:10.1187/cbe.06-06-0168

Cherie Miot Abbanat. 11.229 Advanced Writing Seminar. Spring 2004. Massachusetts Institute of Technology: MIT OpenCourseWare, https://ocw.mit.edu . License: Creative Commons BY-NC-SA .

Haynes Miller, Nat Stapleton, Saul Glasman, and Susan Ruff. 18.821 Project Laboratory in Mathematics. Spring 2013. Massachusetts Institute of Technology: MIT OpenCourseWare, https://ocw.mit.edu . License: Creative Commons BY-NC-SA .

Lori Breslow, and Terence Heagney. 15.279 Management Communication for Undergraduates. Fall 2012. Massachusetts Institute of Technology: MIT OpenCourseWare, https://ocw.mit.edu . License: Creative Commons BY-NC-SA .

O’Reilly, L., & Cyr, T. (2006). Creating a Rubric: An Online Tutorial for Faculty. Retrieved from https://www.ucdenver.edu/faculty_staff/faculty/center-for-faculty-development/Documents/Tutorials/Rubrics/index.htm

Suskie, L. (2009). Using a scoring guide or rubric to plan and evaluate an assessment. In Assessing student learning: A common sense guide (2nd edition, pp. 137-154 ) . Jossey-Bass.

William Li, Grace Teo, and Robert Miller. 6.811 Principles and Practice of Assistive Technology. Fall 2014. Massachusetts Institute of Technology: MIT OpenCourseWare, https://ocw.mit.edu . License: Creative Commons BY-NC-SA .

- Skip to Content

- Skip to Main Navigation

- Skip to Search

IUPUI IUPUI IUPUI

- Center Directory

- Hours, Location, & Contact Info

- Plater-Moore Conference on Teaching and Learning

- Teaching Foundations Webinar Series

- Associate Faculty Development

- Early Career Teaching Academy

- Faculty Fellows Program

- Graduate Student and Postdoc Teaching Development

- Awardees' Expectations

- Request for Proposals

- Proposal Writing Guidelines

- Support Letter

- Proposal Review Process and Criteria

- Support for Developing a Proposal

- Download the Budget Worksheet

- CEG Travel Grant

- Albright and Stewart

- Bayliss and Fuchs

- Glassburn and Starnino

- Rush Hovde and Stella

- Mithun and Sankaranarayanan

- Hollender, Berlin, and Weaver

- Rose and Sorge

- Dawkins, Morrow, Cooper, Wilcox, and Rebman

- Wilkerson and Funk

- Vaughan and Pierce

- CEG Scholars

- Broxton Bird

- Jessica Byram

- Angela and Neetha

- Travis and Mathew

- Kelly, Ron, and Jill

- Allison, David, Angela, Priya, and Kelton

- Pamela And Laura

- Tanner, Sally, and Jian Ye

- Mythily and Twyla

- Learning Environments Grant

- Extended Reality Initiative(XRI)

- Champion for Teaching Excellence Award

- Feedback on Teaching

- Consultations

- Equipment Loans

- Quality Matters@IU

- To Your Door Workshops

- Support for DEI in Teaching

- IU Teaching Resources

- Just-In-Time Course Design

- Teaching Online

- Scholarly Teaching Taxonomy

- The Forum Network

- Media Production Spaces

- CTL Happenings Archive

- Recommended Readings Archive

Center for Teaching and Learning

- Assessing Student Learning

Creating and Using Rubrics

Rubrics are both assessment tools for faculty and learning tools for students that can ease anxiety about the grading process for both parties. Rubrics lay out specific criteria and performance expectations for an assignment. They help students and instructors stay focused on those expectations and to be more confident in their work as a result. Creating rubrics does require a substantial time investment up front, but this process will result in reduced time spent grading or explaining assignment criteria down the road.

Reasons for Using Rubrics

Research indicates that rubrics:

- Rubrics can help normalize the work of multiple graders, e.g., across different sections of a single course or in large lecture courses where TAs manage labs or discussion groups.

- Well-crafted rubrics can reduce the time that faculty spend grading assignments.

- Timely feedback has a positive impact on the learning process.

- When coupled with other forms of feedback (e.g., brief, individualized comments) rubrics show students how to improve.

- By giving students a clear sense of what constitutes different levels of performance, rubrics can make self- and peer-assessments more meaningful and effective.

- If students complete an assignment with a rubric as a guide, then students are better equipped to think critically about their work and to improve it.

- Rubrics establish, in great detail, what different levels of student work look like. If students have seen an assignment rubric in advance and know that they will be held accountable to it, defending grade decisions can be much easier.

Tips for Creating Effective Rubrics

- To create performance descriptions for a new rubric, first rank student responses to an assignment from best to mediocre to worst. Read back through the assignments in that order. Record the characteristics that define student work at each of the three levels. Use your notes to craft the performance descriptions for each criteria category of your new rubric.

- Alternately, start by drafting your high and low performance descriptions for each criteria category, then fill in the mid-range descriptions.

- Use the language of your assignment prompt in your rubric.

- Consider rubric language carefully—how do you encapsulate the range of student responses that could realistically fall in a given cell? Lots of “and/or” statements.

- E.g., “Introduction and/or conclusion handled well but may leave some points unaddressed;” “Sources may be improperly cited or may be missing”

- Completely Effective, Reasonably Effective, Ineffective

- Superb, Strong, Acceptable, Weak

- Compelling, Reasonable, Basic

- Advanced, Intermediate, Novice

- Proficient, Not Yet Proficient, Beginning

- Outstanding, Very Good, Good, Basic, Unsatisfactory

- Exemplary, Proficient, Competent, Developing, Beginning

Tips for Testing and Revising Rubrics

- Score sample assignments without a rubric and then with one. Compare the results. Ask a colleague to use your rubric to do the same.

- Ask a colleague to use your rubric to score student work you've already scored with the rubric and then compare results.

- Get your colleagues' feedback on the alignment of your rubric's grading criteria with your assignment and course-level learning objectives.

- Discuss your rubrics with your students and determine what they do and do not like or understand about them.

Tips for Using Rubrics

- Create a generic rubric template that you can modify for specific assignments.

- Keep the rubric to one page if at all possible. Give the rubric a descriptive title that clearly links it to the assignment prompt and/or digital grade book.

- Give the rubric to students in advance (i.e., with the related assignment prompt) and discuss it with them. Explain the purpose of the rubric, and require students to use the rubric for self-assessment and to reflect on process.

- Allow students to score example work with the rubric before attempting actual peer- or self-review. Discuss with the students how the example work correlates to the competency levels on the rubric.

- Consider engaging in active-learning, rubric development exercises with your students. Have your students help you identify relevant assignment components or develop drafts of your performance descriptions, etc.

- When returning work to students, only highlight those portions of the rubric text that are relevant.

- Couple rubrics with other measures or forms of feedback. Giving brief additional feedback that responds holistically and/or subjectively to student work is a good way to support formative assessment.

- Include relevant learning objectives on your rubrics and/or related assignment prompts.

- To document trends in your teaching, keep copies of rubrics that you return to students and review them later on. Analyzing groups of graded rubrics over time can give you a sense of what might be weak in your teaching and what you need to focus on in the future.

- Canvas has a built-in rubric tool .

- iRubric can be used create be used to create rubrics in Canvas as well (availability varies by department).

Online Resources

- Rubrics resource page from the Eberly Center at Carnegie Mellon University (includes several discipline-specific examples):

- Sample Rubrics from the Association for the Assessment of Learning in Higher Education

- Association of American Colleges and Universities VALUE (Valid Assessment of Learning in Undergraduate Education) Rubrics

- Holistic Essay-Grading Rubrics at the University of Georgia, Athens

- Quality Matters Rubric for Assessing University-Level Online and Blended Courses (Seventh Edition)

- iRubric Tool and Samples

- Canvas Guides on Rubrics:

- Creating a rubric

- Editing a rubric

- Managing course rubrics

- Rubrics in Speedgrader

Barkley, E.F., Cross, P.K., and Major, C.H. (2005). Collaborative learning techniques: A handbook for college faculty . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Barney, Sebastian, et al . “Improving Students with Rubric-Based Self-Assessment and Oral Feedback.” IEEE Transaction on Education 55, no. 3 (August 2012): 319-25.

Besterfield-Sacre, Mary, et al . “Scoring Concept Maps: An Integrated Rubric for Assessing Engineering Education.” Journal of Engineering Education 93, no. 2 (2004): 105-15.

Broad, Brian. What we Really Value: Beyond Rubrics in Teaching and Writing Assessment . Logan, UT: Utah State University Press, 2003.

Hout, Brian. Rearticulating Writing Assessment for Teaching and Learning . Logan, UT: Utah State University Press, 2002.

Howell, Rebecca J. “Exploring the Impact of Grading Rubrics on Academic Performance: Findings from a Quasi-Experimental, Pre-Post Evaluation.” Journal on Excellence in College Teaching 22, no. 2 (2011): 31-49.

Jonsson, Anders and Gunilla Svingby. “The Use of Scoring Rubrics: Reliability, Validity, and Educational Consequences.” Educational Research Review 2 (2007): 130-44.

Kishbaugh, Tara L.S., et al . “Measuring Beyond Content: A Rubric Bank for Assessing Skills in Authentic Research Assignments in the Sciences.” Chemistry Education Research and Practice 13 (2012): 268-76.

Leist, Cathy, et al . “The Effects of Using a Critical Thinking Scoring Rubric to Assess Undergraduate Students’ Reading Skills.” Journal of College Reading and Learning 43, no. 1 (Fall 2012): 31-58.

Livingston, Michael and Lisa Storm Fink. “The Infamy of Grading Rubrics.” English Journal, High School Edition 102, no. 2 (Nov. 2012): 108-13.

Stevens, Dannelle D. and Antonia J. Levi. Introduction to Rubrics: An Assessment Tool to Save GradingTime, Convey Effective Feedback and Promote Student Learning . (Sterling, VA: Stylus Press, 2005).

Wilson, Maja. Rethinking Rubrics in Writing Assessment . (Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 2006).

Authored by James Gregory (September, 2014)

Updated by James Gregory (September, 2015)

Updated by James Gregory (February, 2016)

Updated by Andi Rehak (February, 2017)

Center for Teaching and Learning resources and social media channels

Eberly Center

Teaching excellence & educational innovation, creating and using rubrics.

A rubric is a scoring tool that explicitly describes the instructor’s performance expectations for an assignment or piece of work. A rubric identifies:

- criteria: the aspects of performance (e.g., argument, evidence, clarity) that will be assessed

- descriptors: the characteristics associated with each dimension (e.g., argument is demonstrable and original, evidence is diverse and compelling)

- performance levels: a rating scale that identifies students’ level of mastery within each criterion

Rubrics can be used to provide feedback to students on diverse types of assignments, from papers, projects, and oral presentations to artistic performances and group projects.

Benefitting from Rubrics

- reduce the time spent grading by allowing instructors to refer to a substantive description without writing long comments

- help instructors more clearly identify strengths and weaknesses across an entire class and adjust their instruction appropriately

- help to ensure consistency across time and across graders

- reduce the uncertainty which can accompany grading

- discourage complaints about grades

- understand instructors’ expectations and standards

- use instructor feedback to improve their performance

- monitor and assess their progress as they work towards clearly indicated goals

- recognize their strengths and weaknesses and direct their efforts accordingly

Examples of Rubrics

Here we are providing a sample set of rubrics designed by faculty at Carnegie Mellon and other institutions. Although your particular field of study or type of assessment may not be represented, viewing a rubric that is designed for a similar assessment may give you ideas for the kinds of criteria, descriptions, and performance levels you use on your own rubric.

- Example 1: Philosophy Paper This rubric was designed for student papers in a range of courses in philosophy (Carnegie Mellon).

- Example 2: Psychology Assignment Short, concept application homework assignment in cognitive psychology (Carnegie Mellon).

- Example 3: Anthropology Writing Assignments This rubric was designed for a series of short writing assignments in anthropology (Carnegie Mellon).

- Example 4: History Research Paper . This rubric was designed for essays and research papers in history (Carnegie Mellon).

- Example 1: Capstone Project in Design This rubric describes the components and standards of performance from the research phase to the final presentation for a senior capstone project in design (Carnegie Mellon).

- Example 2: Engineering Design Project This rubric describes performance standards for three aspects of a team project: research and design, communication, and team work.

Oral Presentations

- Example 1: Oral Exam This rubric describes a set of components and standards for assessing performance on an oral exam in an upper-division course in history (Carnegie Mellon).

- Example 2: Oral Communication This rubric is adapted from Huba and Freed, 2000.

- Example 3: Group Presentations This rubric describes a set of components and standards for assessing group presentations in history (Carnegie Mellon).

Class Participation/Contributions

- Example 1: Discussion Class This rubric assesses the quality of student contributions to class discussions. This is appropriate for an undergraduate-level course (Carnegie Mellon).

- Example 2: Advanced Seminar This rubric is designed for assessing discussion performance in an advanced undergraduate or graduate seminar.

See also " Examples and Tools " section of this site for more rubrics.

CONTACT US to talk with an Eberly colleague in person!

- Faculty Support

- Graduate Student Support

- Canvas @ Carnegie Mellon

- Quick Links

Creating Effective Rubrics: Examples and Best Practices

- Classroom Activities/Strategies/Guides

Rubrics are an essential component of assessing student learning effectively. A rubric is a scoring guide that clearly defines the expectations for student performance on a particular task or assignment. Teachers can use rubrics to both evaluate a student’s performance level and to provide feedback to that student. Because they provide a standardized way to assess learning, rubrics help to ensure grading is fair and consistent across all students.

It is important that rubrics are a clear, consistent evaluation of a student’s work. This can sometimes be hard to achieve because rubrics have the potential to become cumbersome and confusing. The best rubrics will typically include specific criteria relevant to the task or assignment at hand, as well as a set of descriptors that outline the different levels of performance that learners may achieve.

There are many different types and uses of rubrics, as well as many benefits of using rubrics. Therefore, learning how to create effective rubrics and the best practices for using rubrics is important for all educators to know. Some may think rubrics are only used in upper-level grades or only for essay assignments, but rubrics can be a beneficial tool for many different subjects and grade levels. All teachable content has learning goals and outcomes, and therefore all content can benefit from the use of good-quality rubrics.

Types of Rubrics

There are three main types of rubrics that are typically used in the education realm: analytic, holistic, and developmental. These three rubrics all pair differently with certain tasks or assignments, depending on the learning goals and desired outcomes for the assignment. While each have their advantages and disadvantages, they all have an appropriate place in a teacher’s assessment toolbox.

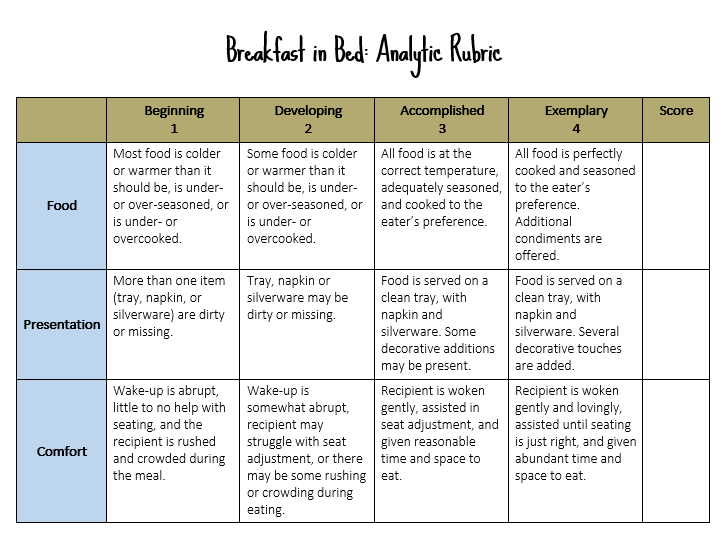

Analytic Rubric

Analytic rubrics focus on breaking down the work into specific components or criteria and then evaluating each of those components separately. Each individual component is usually scored on a separate scale, allowing for more detailed feedback on the strengths and weaknesses of the performance. Analytic rubrics are useful when there is a specific focus on particular skills or knowledge students are expected to demonstrate. Analytic rubrics are very specific and detailed, and for that reason, they can sometimes be seen as more complicated or complex to use.

Analytic rubrics are sometimes viewed as the most reliable assessment rubric because they tend to be more precise assessments and offer more specific and detailed feedback to students. Because of this, these rubrics are often better able to align with learning objects, which can promote deeper learning. Teachers who are using more targeted instruction will benefit from using a more targeted assessment.

Below, Jennifer Gonzalez of Cult of Pedagogy offers a playful example of rubrics assessing breakfast in bed:

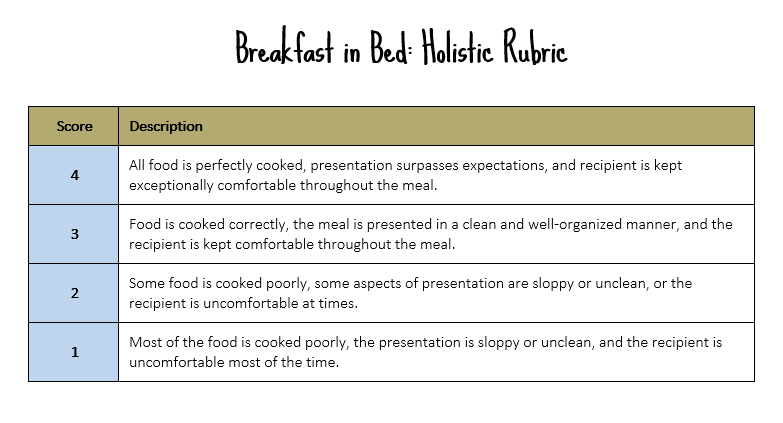

Holistic Rubric

Holistic rubrics provide a broader overall assessment of the quality of student work. They typically use a single scale to evaluate the work, ranging simply from one to five or from excellent to poor. Holistic rubrics are useful when the focus is on the overall quality of the work rather than on smaller, more specific components of the work.

Holistic rubrics can be used at any point in any subject when there is a task or assignment being assessed as a whole. For example, art classes often use a holistic grading rubric to assess broad categories such as creativity or composition. Whereas an English class may use a more analytical rubric for writing, a history class may use a holistic rubric when grading an essay for the overall success of argumentation, evidence, and organization. Holistic rubrics are often used with projects in many classes to evaluate the quality of the project on an overall scale from weak to exemplary.

Developmental Rubric

Finally, developmental rubrics are used to assess a student’s progress or development over time. They are typically used in subjects like writing or language development, where progress is more gradual. Developmental rubrics are great for courses or assessments that require multiple assessments over a longer period of time. Within a developmental rubric, there are multiple levels of performance that show progress made from one level to the next over time.

Because developmental rubrics are focused on growth and development, they are often best used in courses to judge progress that has been made over a length of the course. For example, English classes may assess someone’s writing growth with a developmental rubric that ranges from weak to exemplary. Math classes may assess progress on categories such as problem-solving or mathematical reasoning with a rubric including emerging, developing, and proficient levels. Likewise, art classes may track progressions of creativity and technique with descriptors like beginner, intermediate, or advanced. As a student’s knowledge and skills develop over time, teachers will see a progression in learning and mastery of those concepts.

How to Design a Rubric

While each type of rubric may have its own step in how to design it, the overall process of designing a rubric should follow a standard pattern of steps. Writing a strong rubric takes time and attention to detail, but the outcome produces a more effective rubric that will offer more benefits to students and the teacher.

Plan your purpose and pick a rubric style . First, teachers must decide what they want to teach, what they want to assess, and then how they are going to assess it. Teachers must think all the way to the end even at the very beginning. This may determine what type of rubric will be designed.

Align the rubric with the task or assignment . Once a certain rubric has been chosen, teachers must identify the learning objectives of the assessment and determine the skills and knowledge the students need to demonstrate. If a teacher does not properly align the assessment with the assignment, then they are seemingly setting students up for failure.

Write clear and concise criteria and levels of performance . Long and wordy does not always mean detailed or superior. Sometimes the lengthy and complex rubrics may seem detailed, but instead overwhelm or confuse students. Teachers must develop the criteria and descriptors for each criterion, but doing so in a clear and concise way will help students better understand what is expected of them.

Provide specific and actionable feedback to students . Remember that rubrics and assessments are ultimately meant to be used as a tool for supporting student learning and growth. Therefore, rubrics should be used as a stepping stone, not an end point. Students should be able to do something with the feedback that has been presented to them on a rubric.

Reflect on what worked and be willing to revise . The first rubric designed for an assessment may not always be the final rubric used. Sometimes rubrics need edits or changes along the way, and it is better for the teacher to accept responsibility for those adjustments rather than risk inaccurately assessing students based on a poorly constructed rubric.

Online resources for rubrics are very common and range from simple rubric examples , to common core-aligned rubrics , to college university recommended rubrics. For example, NC State University offers best rubric practices and examples, including this example of a holistic rubric for a final paper:

Within the last few years, the College Board switched its AP English Language and Composition rubric from a holistic grading scale of zero to nine to using an analytic rubric, which evaluates student performance based on three main scoring categories.

Using Rubrics for Assessment

To use rubrics to facilitate fair, efficient, and effective assessment of student work, there are several things to consider when implementing the rubrics. These include the purpose of the rubric, the placement within the lesson plan, and the people using the rubric.

First, one must consider what the intended purpose of the rubric is within the assessment. For example, rubrics can be used in different types of assessments, such as formative or summative. Both types of assessments are valuable for different reasons, and therefore rubrics should be used in both scenarios.

Another thing to consider when using rubrics is the placement of the rubric within the lesson plan. Providing the rubric at the beginning of a task or assessment can allow students to clearly see the requirements and expectations. Using a rubric in the middle of an assignment can provide more specific and actionable feedback for students before completing a project. Then, of course, using the rubric at the end of a lesson plan is where final and more formal assessment and reflection can take place.

Finally, teachers are not the only ones who can fill out and “assess” using a rubric. Allowing students to use rubrics for self-assessment and peer assessment teaches them vital skills of how to self-evaluate their work as well as how to offer constructive criticism and compliments to others.

It is important that once a rubric has been used for assessment, the data generated be evaluated, processed, and used for future assignments. Because rubrics allow teachers to assess with fairness and objectivity, the results of rubrics offer teachers and students valuable feedback for teaching and learning.

Best Practices for Creating Effective Rubrics

Whether you are providing detailed feedback to a student on their essay, observing that a student needs improvement on a certain math skill, or assessing the overall quality of someone’s artwork, rubrics used effectively lead to less teacher stress and more student success. Creating clear, reliable, and valid rubrics might seem like a massive undertaking, but with a few simple steps and a few key strategies, rubrics can revolutionize a classroom .

Use clear and concise language . Students often struggle with heavy academic language, so providing clear instructions and understandable language can help students go into a task or assignment knowing exactly what is expected of them. This includes writing clear and concise criteria and levels of performance.

Know when to use what . Use different types of rubrics for different tasks or assignments. A teacher who uses a variety of assessments is a teacher who understands different students learn in different ways. Rubrics are not “one size fits all,” so know when to use different resources. The rubric must align with the task or assignment to be effective for both teachers and students.

Provide actionable feedback . A painful moment for a teacher is when a student looks at the number or letter at the top of a grade sheet, ignores the heartfelt feedback written on the page, and immediately tosses it into the trash can. Teachers can avoid this scenario by providing specific action steps for students to take once they have received their feedback.

Some of the common misconceptions when it comes to creating and using effective rubrics are that 1) any rubric will work for anything and that 2) rubrics are too hard to make. These two misconceptions lead people to the common mistake of taking to the Internet and downloading a rubric that looks like a good fit.

It is important to avoid these when creating rubrics because the reality is that not all rubrics will work for all assignments, but it is also not impossible to quickly and effectively create a rubric that is perfect for your specific needs. If using a rubric from another source, you must ensure the reliability and validity of the rubric. One might be better off creating a simple holistic rubric than using a detailed analytic rubric that needs a lot of checking or editing to fit your assignment.

Conclusion: The Importance of Rubrics in Education

Rubrics are an important assessment tool for evaluating student learning and provide a consistent, fair, and clear way to assess student work. While there are a number of different rubric resources available online, rubrics are also fairly easy for educators to create and personalize to their specific needs. Creating rubrics is an ongoing process, which means it is important to continually review and revise rubrics to ensure they are still meeting the needs of the students. Just as students need to make adjustments in their learning, teachers may also need to make adjustments from time to time in their assessments.

Subscribe to EDVIEW360 to gain access to podcast episodes, webinars and blog posts where top education thought leaders discuss hot topics in the industry.

Center for Teaching Innovation

Resource library.

- AACU VALUE Rubrics

Using rubrics

A rubric is a type of scoring guide that assesses and articulates specific components and expectations for an assignment. Rubrics can be used for a variety of assignments: research papers, group projects, portfolios, and presentations.

Why use rubrics?

Rubrics help instructors:

- Assess assignments consistently from student-to-student.

- Save time in grading, both short-term and long-term.

- Give timely, effective feedback and promote student learning in a sustainable way.

- Clarify expectations and components of an assignment for both students and course teaching assistants (TAs).

- Refine teaching methods by evaluating rubric results.

Rubrics help students:

- Understand expectations and components of an assignment.

- Become more aware of their learning process and progress.

- Improve work through timely and detailed feedback.

Considerations for using rubrics

When developing rubrics consider the following:

- Although it takes time to build a rubric, time will be saved in the long run as grading and providing feedback on student work will become more streamlined.

- A rubric can be a fillable pdf that can easily be emailed to students.

- They can be used for oral presentations.

- They are a great tool to evaluate teamwork and individual contribution to group tasks.

- Rubrics facilitate peer-review by setting evaluation standards. Have students use the rubric to provide peer assessment on various drafts.

- Students can use them for self-assessment to improve personal performance and learning. Encourage students to use the rubrics to assess their own work.

- Motivate students to improve their work by using rubric feedback to resubmit their work incorporating the feedback.

Getting Started with Rubrics

- Start small by creating one rubric for one assignment in a semester.

- Ask colleagues if they have developed rubrics for similar assignments or adapt rubrics that are available online. For example, the AACU has rubrics for topics such as written and oral communication, critical thinking, and creative thinking. RubiStar helps you to develop your rubric based on templates.

- Examine an assignment for your course. Outline the elements or critical attributes to be evaluated (these attributes must be objectively measurable).

- Create an evaluative range for performance quality under each element; for instance, “excellent,” “good,” “unsatisfactory.”

- Avoid using subjective or vague criteria such as “interesting” or “creative.” Instead, outline objective indicators that would fall under these categories.

- The criteria must clearly differentiate one performance level from another.

- Assign a numerical scale to each level.

- Give a draft of the rubric to your colleagues and/or TAs for feedback.

- Train students to use your rubric and solicit feedback. This will help you judge whether the rubric is clear to them and will identify any weaknesses.

- Rework the rubric based on the feedback.

- Faculty and Staff

Assessment and Curriculum Support Center

Creating and using rubrics.

Last Updated: 4 March 2024. Click here to view archived versions of this page.

On this page:

- What is a rubric?

- Why use a rubric?

- What are the parts of a rubric?

- Developing a rubric

- Sample rubrics

- Scoring rubric group orientation and calibration

- Suggestions for using rubrics in courses

- Equity-minded considerations for rubric development

- Tips for developing a rubric

- Additional resources & sources consulted

Note: The information and resources contained here serve only as a primers to the exciting and diverse perspectives in the field today. This page will be continually updated to reflect shared understandings of equity-minded theory and practice in learning assessment.

1. What is a rubric?

A rubric is an assessment tool often shaped like a matrix, which describes levels of achievement in a specific area of performance, understanding, or behavior.

There are two main types of rubrics:

Analytic Rubric : An analytic rubric specifies at least two characteristics to be assessed at each performance level and provides a separate score for each characteristic (e.g., a score on “formatting” and a score on “content development”).

- Advantages: provides more detailed feedback on student performance; promotes consistent scoring across students and between raters

- Disadvantages: more time consuming than applying a holistic rubric

- You want to see strengths and weaknesses.

- You want detailed feedback about student performance.

Holistic Rubric: A holistic rubrics provide a single score based on an overall impression of a student’s performance on a task.

- Advantages: quick scoring; provides an overview of student achievement; efficient for large group scoring

- Disadvantages: does not provided detailed information; not diagnostic; may be difficult for scorers to decide on one overall score

- You want a quick snapshot of achievement.

- A single dimension is adequate to define quality.

2. Why use a rubric?

- A rubric creates a common framework and language for assessment.

- Complex products or behaviors can be examined efficiently.

- Well-trained reviewers apply the same criteria and standards.

- Rubrics are criterion-referenced, rather than norm-referenced. Raters ask, “Did the student meet the criteria for level 5 of the rubric?” rather than “How well did this student do compared to other students?”

- Using rubrics can lead to substantive conversations among faculty.

- When faculty members collaborate to develop a rubric, it promotes shared expectations and grading practices.

Faculty members can use rubrics for program assessment. Examples:

The English Department collected essays from students in all sections of English 100. A random sample of essays was selected. A team of faculty members evaluated the essays by applying an analytic scoring rubric. Before applying the rubric, they “normed”–that is, they agreed on how to apply the rubric by scoring the same set of essays and discussing them until consensus was reached (see below: “6. Scoring rubric group orientation and calibration”). Biology laboratory instructors agreed to use a “Biology Lab Report Rubric” to grade students’ lab reports in all Biology lab sections, from 100- to 400-level. At the beginning of each semester, instructors met and discussed sample lab reports. They agreed on how to apply the rubric and their expectations for an “A,” “B,” “C,” etc., report in 100-level, 200-level, and 300- and 400-level lab sections. Every other year, a random sample of students’ lab reports are selected from 300- and 400-level sections. Each of those reports are then scored by a Biology professor. The score given by the course instructor is compared to the score given by the Biology professor. In addition, the scores are reported as part of the program’s assessment report. In this way, the program determines how well it is meeting its outcome, “Students will be able to write biology laboratory reports.”

3. What are the parts of a rubric?

Rubrics are composed of four basic parts. In its simplest form, the rubric includes:

- A task description . The outcome being assessed or instructions students received for an assignment.

- The characteristics to be rated (rows) . The skills, knowledge, and/or behavior to be demonstrated.

- Beginning, approaching, meeting, exceeding

- Emerging, developing, proficient, exemplary

- Novice, intermediate, intermediate high, advanced

- Beginning, striving, succeeding, soaring

- Also called a “performance description.” Explains what a student will have done to demonstrate they are at a given level of mastery for a given characteristic.

4. Developing a rubric

Step 1: Identify what you want to assess

Step 2: Identify the characteristics to be rated (rows). These are also called “dimensions.”

- Specify the skills, knowledge, and/or behaviors that you will be looking for.

- Limit the characteristics to those that are most important to the assessment.

Step 3: Identify the levels of mastery/scale (columns).

Tip: Aim for an even number (4 or 6) because when an odd number is used, the middle tends to become the “catch-all” category.

Step 4: Describe each level of mastery for each characteristic/dimension (cells).

- Describe the best work you could expect using these characteristics. This describes the top category.

- Describe an unacceptable product. This describes the lowest category.

- Develop descriptions of intermediate-level products for intermediate categories.

Important: Each description and each characteristic should be mutually exclusive.

Step 5: Test rubric.

- Apply the rubric to an assignment.

- Share with colleagues.

Tip: Faculty members often find it useful to establish the minimum score needed for the student work to be deemed passable. For example, faculty members may decided that a “1” or “2” on a 4-point scale (4=exemplary, 3=proficient, 2=marginal, 1=unacceptable), does not meet the minimum quality expectations. We encourage a standard setting session to set the score needed to meet expectations (also called a “cutscore”). Monica has posted materials from standard setting workshops, one offered on campus and the other at a national conference (includes speaker notes with the presentation slides). They may set their criteria for success as 90% of the students must score 3 or higher. If assessment study results fall short, action will need to be taken.

Step 6: Discuss with colleagues. Review feedback and revise.

Important: When developing a rubric for program assessment, enlist the help of colleagues. Rubrics promote shared expectations and consistent grading practices which benefit faculty members and students in the program.

5. Sample rubrics

Rubrics are on our Rubric Bank page and in our Rubric Repository (Graduate Degree Programs) . More are available at the Assessment and Curriculum Support Center in Crawford Hall (hard copy).

These open as Word documents and are examples from outside UH.

- Group Participation (analytic rubric)

- Participation (holistic rubric)

- Design Project (analytic rubric)

- Critical Thinking (analytic rubric)

- Media and Design Elements (analytic rubric; portfolio)

- Writing (holistic rubric; portfolio)

6. Scoring rubric group orientation and calibration

When using a rubric for program assessment purposes, faculty members apply the rubric to pieces of student work (e.g., reports, oral presentations, design projects). To produce dependable scores, each faculty member needs to interpret the rubric in the same way. The process of training faculty members to apply the rubric is called “norming.” It’s a way to calibrate the faculty members so that scores are accurate and consistent across the faculty. Below are directions for an assessment coordinator carrying out this process.

Suggested materials for a scoring session:

- Copies of the rubric

- Copies of the “anchors”: pieces of student work that illustrate each level of mastery. Suggestion: have 6 anchor pieces (2 low, 2 middle, 2 high)

- Score sheets

- Extra pens, tape, post-its, paper clips, stapler, rubber bands, etc.

Hold the scoring session in a room that:

- Allows the scorers to spread out as they rate the student pieces

- Has a chalk or white board, smart board, or flip chart

- Describe the purpose of the activity, stressing how it fits into program assessment plans. Explain that the purpose is to assess the program, not individual students or faculty, and describe ethical guidelines, including respect for confidentiality and privacy.

- Describe the nature of the products that will be reviewed, briefly summarizing how they were obtained.

- Describe the scoring rubric and its categories. Explain how it was developed.

- Analytic: Explain that readers should rate each dimension of an analytic rubric separately, and they should apply the criteria without concern for how often each score (level of mastery) is used. Holistic: Explain that readers should assign the score or level of mastery that best describes the whole piece; some aspects of the piece may not appear in that score and that is okay. They should apply the criteria without concern for how often each score is used.

- Give each scorer a copy of several student products that are exemplars of different levels of performance. Ask each scorer to independently apply the rubric to each of these products, writing their ratings on a scrap sheet of paper.

- Once everyone is done, collect everyone’s ratings and display them so everyone can see the degree of agreement. This is often done on a blackboard, with each person in turn announcing his/her ratings as they are entered on the board. Alternatively, the facilitator could ask raters to raise their hands when their rating category is announced, making the extent of agreement very clear to everyone and making it very easy to identify raters who routinely give unusually high or low ratings.

- Guide the group in a discussion of their ratings. There will be differences. This discussion is important to establish standards. Attempt to reach consensus on the most appropriate rating for each of the products being examined by inviting people who gave different ratings to explain their judgments. Raters should be encouraged to explain by making explicit references to the rubric. Usually consensus is possible, but sometimes a split decision is developed, e.g., the group may agree that a product is a “3-4” split because it has elements of both categories. This is usually not a problem. You might allow the group to revise the rubric to clarify its use but avoid allowing the group to drift away from the rubric and learning outcome(s) being assessed.

- Once the group is comfortable with how the rubric is applied, the rating begins. Explain how to record ratings using the score sheet and explain the procedures. Reviewers begin scoring.

- Are results sufficiently reliable?

- What do the results mean? Are we satisfied with the extent of students’ learning?

- Who needs to know the results?

- What are the implications of the results for curriculum, pedagogy, or student support services?

- How might the assessment process, itself, be improved?

7. Suggestions for using rubrics in courses

- Use the rubric to grade student work. Hand out the rubric with the assignment so students will know your expectations and how they’ll be graded. This should help students master your learning outcomes by guiding their work in appropriate directions.

- Use a rubric for grading student work and return the rubric with the grading on it. Faculty save time writing extensive comments; they just circle or highlight relevant segments of the rubric. Some faculty members include room for additional comments on the rubric page, either within each section or at the end.

- Develop a rubric with your students for an assignment or group project. Students can the monitor themselves and their peers using agreed-upon criteria that they helped develop. Many faculty members find that students will create higher standards for themselves than faculty members would impose on them.

- Have students apply your rubric to sample products before they create their own. Faculty members report that students are quite accurate when doing this, and this process should help them evaluate their own projects as they are being developed. The ability to evaluate, edit, and improve draft documents is an important skill.

- Have students exchange paper drafts and give peer feedback using the rubric. Then, give students a few days to revise before submitting the final draft to you. You might also require that they turn in the draft and peer-scored rubric with their final paper.

- Have students self-assess their products using the rubric and hand in their self-assessment with the product; then, faculty members and students can compare self- and faculty-generated evaluations.

8. Equity-minded considerations for rubric development

Ensure transparency by making rubric criteria public, explicit, and accessible

Transparency is a core tenet of equity-minded assessment practice. Students should know and understand how they are being evaluated as early as possible.

- Ensure the rubric is publicly available & easily accessible. We recommend publishing on your program or department website.

- Have course instructors introduce and use the program rubric in their own courses. Instructors should explain to students connections between the rubric criteria and the course and program SLOs.

- Write rubric criteria using student-focused and culturally-relevant language to ensure students understand the rubric’s purpose, the expectations it sets, and how criteria will be applied in assessing their work.

- For example, instructors can provide annotated examples of student work using the rubric language as a resource for students.

Meaningfully involve students and engage multiple perspectives

Rubrics created by faculty alone risk perpetuating unseen biases as the evaluation criteria used will inherently reflect faculty perspectives, values, and assumptions. Including students and other stakeholders in developing criteria helps to ensure performance expectations are aligned between faculty, students, and community members. Additional perspectives to be engaged might include community members, alumni, co-curricular faculty/staff, field supervisors, potential employers, or current professionals. Consider the following strategies to meaningfully involve students and engage multiple perspectives:

- Have students read each evaluation criteria and talk out loud about what they think it means. This will allow you to identify what language is clear and where there is still confusion.

- Ask students to use their language to interpret the rubric and provide a student version of the rubric.

- If you use this strategy, it is essential to create an inclusive environment where students and faculty have equal opportunity to provide input.

- Be sure to incorporate feedback from faculty and instructors who teach diverse courses, levels, and in different sub-disciplinary topics. Faculty and instructors who teach introductory courses have valuable experiences and perspectives that may differ from those who teach higher-level courses.

- Engage multiple perspectives including co-curricular faculty/staff, alumni, potential employers, and community members for feedback on evaluation criteria and rubric language. This will ensure evaluation criteria reflect what is important for all stakeholders.

- Elevate historically silenced voices in discussions on rubric development. Ensure stakeholders from historically underrepresented communities have their voices heard and valued.

Honor students’ strengths in performance descriptions

When describing students’ performance at different levels of mastery, use language that describes what students can do rather than what they cannot do. For example:

- Instead of: Students cannot make coherent arguments consistently.

- Use: Students can make coherent arguments occasionally.

9. Tips for developing a rubric

- Find and adapt an existing rubric! It is rare to find a rubric that is exactly right for your situation, but you can adapt an already existing rubric that has worked well for others and save a great deal of time. A faculty member in your program may already have a good one.

- Evaluate the rubric . Ask yourself: A) Does the rubric relate to the outcome(s) being assessed? (If yes, success!) B) Does it address anything extraneous? (If yes, delete.) C) Is the rubric useful, feasible, manageable, and practical? (If yes, find multiple ways to use the rubric: program assessment, assignment grading, peer review, student self assessment.)

- Collect samples of student work that exemplify each point on the scale or level. A rubric will not be meaningful to students or colleagues until the anchors/benchmarks/exemplars are available.

- Expect to revise.

- When you have a good rubric, SHARE IT!

10. Additional resources & sources consulted:

Rubric examples:

- Rubrics primarily for undergraduate outcomes and programs

- Rubric repository for graduate degree programs

Workshop presentation slides and handouts:

- Workshop handout (Word document)

- How to Use a Rubric for Program Assessment (2010)

- Techniques for Using Rubrics in Program Assessment by guest speaker Dannelle Stevens (2010)

- Rubrics: Save Grading Time & Engage Students in Learning by guest speaker Dannelle Stevens (2009)

- Rubric Library , Institutional Research, Assessment & Planning, California State University-Fresno

- The Basics of Rubrics [PDF], Schreyer Institute, Penn State

- Creating Rubrics , Teaching Methods and Management, TeacherVision

- Allen, Mary – University of Hawai’i at Manoa Spring 2008 Assessment Workshops, May 13-14, 2008 [available at the Assessment and Curriculum Support Center]

- Mertler, Craig A. (2001). Designing scoring rubrics for your classroom. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation , 7(25).

- NPEC Sourcebook on Assessment: Definitions and Assessment Methods for Communication, Leadership, Information Literacy, Quantitative Reasoning, and Quantitative Skills . [PDF] (June 2005)

Contributors: Monica Stitt-Bergh, Ph.D., TJ Buckley, Yao Z. Hill Ph.D.

Educircles.org

How to Co-Create Rubrics with Students (FREE Lesson Plan, handouts, slideshow)

How do you co-create rubrics with students.

Co-creating rubrics is when a teacher collaborates with students to create a rubric assessment tool together. The theory is that students gain a deeper understanding of what is expected from them if they help create the rubric.

When you co-create a rubric with your class, it’s kind of like you and your class are working together to create a building block replica of a famous painting.

- Everyone in the class contributes some building blocks – including the teacher.

- You’re working together towards an end goal – let’s say you’re trying to re-create a building block version of the Mona Lisa.

- You work as a team to talk about key elements that you have to include in your replica .

- Through the discussion process, you realize that some blocks fit better than others.

- You go back and forth discussing with your students to create something that is more than the sum of its’ parts.

- Over time, you might tweak your structure to make it even better and more accurate..

In the end, you class might even end up with a Lego reconstruction of the Mona Lisa like this . (Made by Nathan Sawaya )

Now imagine the same process of collaboration, but with ideas. And the goal is to create an assessment tool for an assignment.

- Everyone in the class contributes some ideas – including the teacher.

- You’re working together towards an end goal – creating an assessment rubric for a major assignment.

- You work as a team to talk about key elements that you have to include in your rubric .

- Through the discussion process, you realize that some ideas fit better than others.

- Over time, you might tweak your rubric to make it even better and more accurate.

But it’s one thing to build with building blocks because they’re tangible and more concrete. It’s a lot harder when you have to build ideas together in a group.

So, here’s a free lesson plan on how to teach students to effectively co-create rubrics! Use it to learn the process, and then co-create rubrics with your own subject material and lessons!

How to Co-Create Rubrics with Students – Table of Contents

Part 1: co-creating rubrics with students… ummm, why.

- Introduction

What’s a rubric (in a school / academic setting)?

What does it mean to co-create rubrics with students.

- Collaboration

- Coordination

- Cooperation

Collaboration means something new is created.

We don’t always have time to co-create every rubric with students, empathize with your students. co-creating rubrics is hard work., change is hard for everyone. (teachers can have fixed mindsets, too), question for the principals and the people running this meeting:, question for the teachers sitting in the meeting:, don’t worry. we’re not alone. business leaders also tell their group what to think, part 2: free lesson : how to co-create rubrics with students, about this lesson:.

- Independent Thinking Strategy: ASK “WHY or HOW”

- Group Thinking Strategy: IDEA VOLLEYBALL

- Group Thinking Strategy: PEEP

- Group Thinking Strategy: SPEAK OUT

- Group Thinking Strategy: SPEAK LAST

We provide handouts:

We provide 3 different versions of the lesson slideshow (147 slides):, note: this taste of challenge is part of a larger lesson.

- DAY/LESSON 1 – What are the 6Cs / Notes – Show don’t tell – 50 MIN

- DAY/LESSON 2 – Look Fors / Co-Creating criteria – 60 MIN

Co-Creating Rubrics with Students… Ummm, why?