- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Affective Science

- Biological Foundations of Psychology

- Clinical Psychology: Disorders and Therapies

- Cognitive Psychology/Neuroscience

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational/School Psychology

- Forensic Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems of Psychology

- Individual Differences

- Methods and Approaches in Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational and Institutional Psychology

- Personality

- Psychology and Other Disciplines

- Social Psychology

- Sports Psychology

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Gender in a social psychology context.

- Thekla Morgenroth Thekla Morgenroth Department of Psychology, University of Exeter

- and Michelle K. Ryan Michelle K. Ryan Dean of Postgraduate Research and Director of the Doctoral College, University of Exeter

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.013.309

- Published online: 28 March 2018

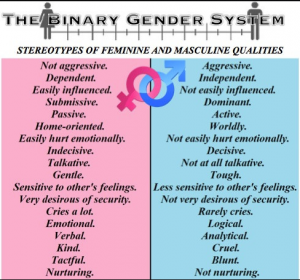

Understanding gender and gender differences is a prevalent aim in many psychological subdisciplines. Social psychology has tended to employ a binary understanding of gender and has focused on understanding key gender stereotypes and their impact. While women are seen as warm and communal, men are seen as agentic and competent. These stereotypes are shaped by, and respond to, social contexts, and are both descriptive and prescriptive in nature. The most influential theories argue that these stereotypes develop in response to societal structures, including the roles women and men occupy in society, and status differences between the sexes. Importantly, research clearly demonstrates that these stereotypes have a myriad of effects on individuals’ cognitions, attitudes, and behaviors and contribute to sexism and gender inequality in a range of domains, from the workplace to romantic relationships.

- gender stereotypes

- gender norms

- social psychology

- social role theory

- stereotype content model

- ambivalent sexism

- stereotype threat

Introduction

Gender is omnipresent—it is one of the first categories children learn, and the categorization of people into men and women 1 affects almost every aspect of our lives. Gender is a key determinant of our self-concept and our perceptions of others. It shapes our mental health, our career paths, and our most intimate relationships. It is therefore unsurprising that psychologists invest a great deal of time in understanding gender as a concept, with social psychologists being no exception. However, this has not always been the case. This article begins with “A Brief History of Gender in Psychology,” which gives an overview about gender within psychology more broadly. The remaining sections discuss how gender is examined within social psychology more specifically, with particular attention to how gender stereotypes form and how they affect our sense of self and our evaluations of others.

A Brief History of Gender in Psychology

During the early years of psychology in general, and social psychology in particular, the topic gender was largely absent from psychology, as indeed were women. Male researchers made claims about human nature based on findings that were restricted to a small portion of the population, namely, white, young, able-bodied, middle-class, heterosexual men [see Etaugh, 2016 ; a phenomenon that has been termed androcentrism (Hegarty, & Buechel, 2006 )]. If women and girls were mentioned at all, they were usually seen as inferior to men and boys (e.g., Hall, 1904 ).

This invisibility of women within psychology changed with a rise of the second wave of feminism in the 1960s. Here, more women entered psychology, demanded to be seen, and pushed back against the narrative of women as inferior. They argued that psychology’s androcentrism, and the sexist views of psychologists, had not only biased psychological theory and research, but also contributed to and reinforced gender inequality in society. For example, Weisstein ( 1968 ) argued that most claims about women made by prominent psychologists, such as Freud and Erikson, lacked an evidential grounding and were instead based on these men’s fantasies of what women were like rather than empirical data. A few years later, Maccoby and Jacklin ( 1974 ) published their seminal work, The Psychology of Sex Differences , which synthesized the literature on sex differences and concluded that there were few (but some) sex differences. This led to a growth of interest in the social origins of sex differences, with a shift away from a psychology of sex (i.e., biologically determined male vs. female) and toward a psychology of gender (i.e., socially constructed masculine vs. feminine).

Since then, the psychology of gender has become a respected and widely represented subdiscipline within psychology. In a fascinating analysis of the history of feminism and psychology, Eagly, Eaton, Rose, Riger, and McHugh ( 2012 ) examined publications on sex differences, gender, and women from 1960 to 2009 . In those 50 years, the number of annual publications rose from close to zero to over 6,500. As a proportion of all psychology articles, one can also see a marked rise in popularity in gender articles from 1960 to 2009 , with peak years of interest in the late 1970s and 1990s. In line with the aforementioned shift from sex differences to gender differences, the largest proportion of these articles fall into the topic of “social processes and social issues,” which includes research on gender roles, masculinity, and femininity.

However, as interest in the area has grown, the ways in which gender is studied, and the political views of those studying it, have become more diverse. Eagly and colleagues note:

we believe that this research gained from feminist ideology but has escaped its boundaries. In this garden, many flowers have bloomed, including some flowers not widely admired by some feminist psychologists. (p. 225)

Here, they allude to the fact that some research has shifted away from societal explanations, which feminist psychologists have generally favored, to more complex views of gender difference. Some of these acknowledge the fact that nature and nurture are deeply intertwined, with both biological and social variables being used to understand gender and gender differences (e.g., Wood & Eagly, 2002 ). Others, such as evolutionary approaches (e.g., Baumeister, 2013 ; Buss, 2016 ) and neuroscientific approaches (see Fine, 2010 ), focus more heavily on the biological bases of gender differences, often causing chagrin among feminists. Nevertheless, much of the research in social psychology has, unsurprisingly, focused on social factors and, in particular, on gender stereotypes. Where do they come from and what are their effects?

Origins and Effects of Gender Stereotypes

A stereotype can be defined as a “widely shared and simplified evaluative image of a social group and its members” (Vaughan & Hogg, 2011 , p. 51) and has both descriptive and prescriptive aspects. In other words, gender stereotypes tell us what women and men are like, but also what they should be like (Heilman, 2001 ). Gender stereotypes are not only widely shared, but they are also stubbornly resistant to change (Haines, Deaux, & Lofaro, 2016 ). Both the origin and the consequences of these stereotypes have received much attention in social psychology. So how do stereotypes form? The most widely cited theories on stereotype formation—social role theory (SRT; Eagly, 1987 ; Eagly, Wood, & Diekman, 2000 ) and the stereotype content model (SCM; Fiske, Cuddy, Glick, & Xu, J., 2002 )—answer this question. Both of these models focus on gender as a binary concept (i.e., men and women), as does most psychological research on gender, although they could potentially also be applied to other gender groups. Both theories are considered in turn.

Social Role Theory: Gender Stereotypes Are Determined by Roles

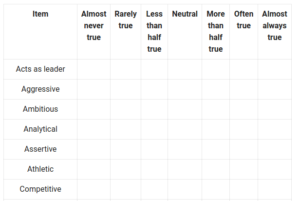

SRT argues that gender stereotypes stem from the distribution of men and women into distinct roles within a given society (Eagly, 1987 ; Eagly et al., 2000 ). The authors note the stability of gender stereotypes across cultures and describe two core dimensions: agency , including traits such as independence, aggression, and assertiveness, and communion , including traits such as caring, altruism, and politeness. While men are generally seen to be high in agency and low in communion, women are generally perceived to be high in communion but low in agency.

According to SRT, these gender stereotypes stem from the fact that women and men are over- and underrepresented in different roles in society. In most societies, even those with higher levels of gender equality, men perform less domestic work compared to women, including childcare, and spend more time in paid employment. Additionally, men disproportionately occupy leadership roles in the workforce (e.g., in politics and management) and are underrepresented in caretaking roles within the workforce (e.g., in elementary education and nursing; see Eagly et al., 2000 ). Eagly and colleagues argue that this gendered division of labor leads to the formation of gender roles and associated stereotypes. More specifically, they propose that different behaviors are seen as necessary to fulfil these social roles, and different skills, abilities, and traits are seen as necessary to execute these behaviors. For example, elementary school teachers are seen to need to care for and interact with children, which is seen to require social skills, empathy, and a caring nature. In contrast, such communal attributes might be seen to be less important—or even detrimental—for a military leader.

To the extent that women and men are differentially represented and visible in certain roles—such as elementary school teachers or military leaders—the behaviors and traits necessary for these roles become part of each respective gender role. In other words, the behaviors and attributes associated with people in caretaking roles, communion, become part of the female gender role, while the behaviors and attributes associated with people in leadership roles, agency, become part of the male gender role.

Building on SRT, Wood and Eagly ( 2002 ) developed a biosocial model of the origins of sex differences which explains the stability of gendered social roles across cultures. The authors argue that, in the past, physical differences between men and women meant that they were better able to perform certain tasks, contributing to the formation of gender roles. More specifically, women had to bear children and nurse them, while men were generally taller and had more upper body strength. In turn, tasks that required upper body strength and long stretches of uninterrupted time (e.g., hunting) were more often carried out by men, while tasks that could be interrupted more easily and be carried out while pregnant or looking after children (e.g., foraging) were more often carried out by women.

Eagly and colleagues further propose that the exact tasks more easily carried out by each sex depended on social and ecological conditions as well as technological and cultural advances. For example, it was only in more advanced, complex societies that the greater size and strength of men led to a division of labor in which men were preferred for activities such as warfare, which also came with higher status and access to resources. Similarly, the development of plough technology led to shifts from hunter–gatherer societies to agricultural societies. This change was often accompanied by a new division of labor in which men owned, farmed, and inherited land while women carried out more domestic tasks. The social structures that arose from these processes in specific contexts in turn affected more proximal causes of gender differences, including gender stereotypes.

It is important to note that this theory focuses on physical differences between the genders, not psychological ones. In other words, the authors do not argue that women and men are inherently different when it comes to their minds, nor that men evolved to be more agentic while women evolved to be more communal.

Stereotype Content Model: Gender Stereotypes Are Determined by Group Relations

The SCM, formulated by Fiske and colleagues ( 2002 ), was not developed specifically for gender, but as an explanation of how stereotypes form more generally. Similar to SRT, the SCM argues that gender stereotypes arise from societal structures. More specifically, the authors suggest that status differences and cooperation versus competition determine group stereotypes—among them, gender stereotypes. This model also suggests two main dimensions to stereotypes, namely, warmth and competence. The concept of warmth is similar to that of communion, previously described, in that it refers to being kind, nice, and caring. Competence refers to attributes such as being intelligent, efficient, and skillful and is thus different from the agency dimension of SRT.

The SCM argues that the dimensions of warmth and competence originate from two fundamental dimensions—status and competition—which characterize the relationships between groups in every culture and society. The degree to which another group is perceived to be warm is determined by whether the group is in cooperation or in competition with one’s own group, which is in turn associated with perceived intentions to help or to harm one’s own group, respectively. While members of cooperating groups are stereotyped as warm, members of competing groups are stereotyped as cold. Evidence suggests that these two dimensions are indeed universal and can be found in many cultures, including collectivist cultures (Cuddy et al., 2009 ). Perceptions of competence, however, are affected by the status and power of the group, which go hand-in-hand with the group’s ability to harm one’s own group. Those groups with high status and power are stereotyped as competent, while those that lack status and power are stereotyped as incompetent.

Groups can thus fall into one of four quadrants of this model. Members of high status groups who cooperate with one’s own group are seen as unequivocally positive—as warm and competent—while those of low status who compete with one’s own group are seen as unequivocally negative—cold and incompetent. More interesting are the two groups that fall into the more ambivalent quadrants—those who are perceived as either warm but incompetent or competent but cold. Applied to gender, this model suggests—and research shows—that typical men are stereotyped as competent but cold, the envious stereotype, while typical women are stereotyped as warm but incompetent, the paternalistic stereotype.

However, these stereotypes do not apply equally to all women and men. Rather, subgroups of men and women come with their own stereotypes. Research demonstrates, for example, that the paternalistic stereotype most strongly applies to traditional women such as housewives, while less traditional women such as feminists and career women are stereotyped as high in competence and low in warmth. For men, there are similar levels of variation—the envious stereotype applies most strongly to men in traditional roles such as managers and career men, while other men are perceived as warm but incompetent (e.g., senior citizens), as cold and incompetent (e.g., punks), or as warm and competent (e.g., professors; Eckes, 2002 ). The section “Gender Stereotypes Affect Emotions, Behavior, and Sexism” discusses the consequences of these stereotypes in more detail.

The Effects of Gender Stereotypes

SRT and the SCM explain how gender stereotypes form. A large body of work in social psychology has focused on the consequences of these stereotypes. These include effects on the gendered perceptions and evaluations of others, as well as effects on the self and one’s own self-image, behavior, and goals.

Gendered Perceptions and Evaluations of Others

Our group-based stereotypes affect how we see members of these groups and how we judge those who do or do not conform to these stereotypes. Gender differs from many other group memberships in several ways (see Fiske & Stevens, 1993 ), which in turn affects consequences of these stereotypes. First, argue Fiske and Stevens, gender stereotypes tend to be more prescriptive than other stereotypes. For example, men may often be told to “man up,” to be tough and dominant, while women may be told to smile, to be nice, and to be sexy (but not too sexy). While stereotypes of other groups also have prescriptive elements, it is probably less common to hear Asians be told to be better at math or African Americans to be told to be more musical. The consequences of these gendered prescriptions are discussed in the section “Gender Stereotypes Affect the Evaluation of Women and Men.” Second, relationships between women and men are characterized by an unusual combination of power differences and close and frequent contact as well as mutual dependence for reproduction and close relationships. The section “Gender Stereotypes Affect Emotions, Behavior, and Sexism” discusses the effects of these factors.

Gender Stereotypes Affect the Evaluation of Women and Men

The evaluation of women and men is affected by both descriptive and prescriptive gender stereotypes. Research on these effects has predominantly focused on those who occupy counterstereotypical roles such as women in leadership or stay-at-home fathers.

Descriptive stereotypes affect the perception and evaluation of women and men in several ways. First, descriptive stereotypes create biased perceptions through expectancy confirming processes (see Fiske, 2000 ) such that individuals, particularly those holding strong stereotypes, seek out information that confirms their stereotypes. This is evident in their tendency to neglect or dismiss ambiguous information and to ask stereotype-confirming questions (Leyens, Yzerbyt, & Schadron, 1994 ; Macrae, Milne, & Bodenhausen, 1994 ). Moreover, people are more likely to recall stereotypical information compared to counterstereotypical information (Rojahn & Pettigrew, 1992 ) Second, descriptive gender stereotypes also bias the extent to which men and women are seen as suitable for different roles, as described in Heilman’s lack of fit model ( 1983 , 1995 ) and Eagly and Karau’s role congruity theory ( 2002 ). These approaches both suggest that the degree of fit between a person’s attributes and the attributes associated with a specific role is positively related to expectations about how successful a person will be in said role. For example, the traits associated with successful managers are generally more similar to those associated with men than those associated with women (Schein, 1973 ; see also Ryan, Haslam, Hersby, & Bongiorno, 2011 ). Thus, all else being equal, a man will be seen as a better fit for a managerial position and in turn as more likely to be a successful manager. These biased evaluations in turn lead to biased decisions, such as in hiring and promotion (see Heilman, 2001 ).

Prescriptive gender stereotypes also affect evaluations, albeit in different ways. They prescribe how women and men should behave, and also how they should not behave. The “shoulds” generally mirror descriptive stereotypes, while the “should nots” often include behaviors associated with the opposite gender. Thus, what is seen as positive and desirable for one gender is often seen as undesirable for the other and can lead to backlash in the form of social and economic penalties (Rudman, 1998 ). For example, women who are seen as agentic are punished with social sanctions because they violate the prescriptive stereotype that women should be nice, even in the absence of information indicating that they are not nice (Rudman & Glick, 2001 ). These processes are particularly problematic in combination with the effects of descriptive stereotypes, as individuals may face a double bind—if women behave in line with gender stereotypes, they lack fit with leadership positions that require agency, but if they behave agentically, they violate gender norms and face backlash in the form of dislike and discrimination (Rudman & Glick, 2001 ). Similar effects have been found for men who violate prescriptive masculine stereotypes, for example, by being modest (Moss-Racusin, Phelan, & Rudman, 2010 ) or by requesting family leave (Rudman & Mescher, 2013 ). Interestingly, however, being communal by itself does not lead to backlash for men (Moss-Racusin et al., 2010 ). In other words, while men can be perceived as highly agentic and highly communal, this is not true for women, who are perceived as lacking communion when being perceived as agentic and as lacking agency when being perceived as communal.

Gender Stereotypes Affect Emotions, Behavior, and Sexism

Stereotypes not only affect how individuals evaluate others, but also their feelings and behaviors toward them. The Behavior from Intergroup Affect and Stereotypes (BIAS) map (Cuddy, Fiske, & Glick, 2007 ), which extends the SCM, describes the relationship between perceptions of warmth and competence of certain groups, emotions directed toward these groups, and behaviors toward them. Cuddy and colleagues argue that bias is comprised of three elements: cognitions (i.e., stereotypes), affect (i.e., emotional prejudice), and behavior (i.e., discrimination), and these are closely linked. Groups perceived as warm and competent elicit admiration while groups perceived as cold and incompetent elicit contempt. Of particular interest to understanding gender are the two ambivalent combinations of warmth and competence: Those perceived as warm, but incompetent—such as typical women—elicit pity, while those perceived as competent, but cold—such as typical men—elicit envy.

Similarly, perceptions of warmth and competence are associated with behavior. Cuddy and colleagues ( 2007 ) argue that the warmth dimension affects behavioral reactions more strongly than competence because it stems from perceptions that a group will help or harm the ingroup. This leads to active facilitation (e.g., helping) when a group is perceived as warm, or active harm (e.g., harassing) when a group is perceived as cold. Competence, however, leads to passive facilitation (e.g., cooperation when it benefits oneself or one’s own group) when the group is perceived as competent, and passive harm (e.g., neglecting to help) when the group is perceived as incompetent.

How these emotional and behavioral reactions affect women and men has received much attention in the literature on ambivalent sexism and ambivalent attitudes toward men (Glick & Fiske, 1996 , 1999 , 2001 ). According to ambivalent sexism theory (AST), sexism is not a uniform, negative attitude toward women or men. Rather, it is comprised of hostile and benevolent elements, which arises from status differences between, and intimate interdependence of, the two genders. While men possess more economic, political, and social power, they depend on women as their mothers and (for heterosexual men) as romantic partners. Thus, while they are likely to be motivated to keep their power, they also need to find ways to foster positive relations with women.

Hostile sexism combines the beliefs that (a) women are inferior to men, (b) men should have more power in society, and (c) women’s sexuality poses a threat to men’s status and power. This form of sexism is mostly directed toward nontraditional women who directly threaten men’s status (e.g., feminists or career women), and women who threaten the heterosexual interdependence of men and women (e.g., lesbians)—in other words, toward women perceived to be competent but cold.

Benevolent sexism is a subtler form of sexism and refers to (a) complementary gender differentiation , the belief that (traditional) women are ultimately the better gender, (b) protective paternalism , where men need to cherish, protect, and provide for women, and (c) heterosexual intimacy , the belief that men and women complement each other such that no man is truly complete without a woman. This form of sexism is directed mainly toward traditional women.

While benevolent sexism may seem less harmful than its hostile counterpart, it ultimately provides an alternative mechanism for the persistence of gender inequality by “keeping women in their place” and discouraging them from seeking out nontraditional roles (see Glick & Fiske, 2001 ). Exposure to benevolent sexism is associated with women’s increased self-stereotyping (Barreto, Ellemers, Piebinga, & Moya, 2010 ), decreased cognitive performance (Dardenne, Dumont, & Bollier, 2007 ), and reduced willingness to take collective action (Becker & Wright, 2011 ), thus reinforcing the status quo.

With perceptions of men, Glick and Fiske ( 1999 ) argue that attitudes are equally ambivalent. Hostile attitudes toward men include (a) resentment of paternalism , stemming from perceptions of unfairness of the disproportionate amounts of power men hold, (b) compensatory gender differentiation , which refers to the application of negative stereotypes to men (e.g., arrogant, unrefined) so that women can positively distinguish themselves from them, and (c) heterosexual hostility , stemming from male sexual aggressiveness and interpersonal dominance. Benevolent attitudes toward men include maternalism , that is, the belief that men are helpless and need to be taken care of at home. Interestingly, while such attitudes portray women as competent in some ways, it still reinforces gender inequality by legitimizing women’s disproportionate amount of domestic work. Benevolent attitudes toward men also include complementary gender differentiation , the belief that men are indeed more competent, and heterosexual attraction , the belief that a woman can only be truly happy when in a romantic relationship with a man.

Cross-cultural research (Glick et al., 2000 , 2004 ) suggests that ambivalent sexism and ambivalent attitudes toward men are similar in many ways and can be found in most cultures. For both constructs, the benevolent and hostile aspects are distinct but positively related, illustrating that attitudes toward women and men are indeed ambivalent, as the mixed nature of stereotypes would suggest. Moreover, ambivalence toward women and men are correlated and national averages of both aspects of sexism and ambivalence toward men are associated with lower gender equality across nations, lending support to the idea that they reinforce the status quo.

Gender Stereotypes Affect the Self

Gender stereotypes not only affect individuals’ reactions toward others, they also play an important part in self-construal, motivation, achievement, and behavior, often without explicit endorsement of the stereotype. This section discusses how gender stereotypes affect observable gender differences and then describes the subtle and insidious effects gender stereotypes can have on performance and achievement through the inducement of stereotype threat (Steele & Aronson, 1995 ).

Gender Stereotypes Affect Gender Differences

Gender stereotypes are a powerful influence on the self-concept, goals, and behaviors. Eagly and colleagues ( 2000 ) argue that girls and boys observe the roles that women and men occupy in society and accommodate accordingly, seeking out different activities and acquiring different skills. They propose two main mechanisms by which gender differences form. First, women and men adjust their behavior to confirm others’ gender-stereotypical expectations. Others communicate their gendered expectations in many, often nonverbal and subtle ways and react positively when expectations are confirmed and negatively when they are not. This subtle communication of expectations reinforces gender-stereotypical behavior as people generally try to elicit positive, and avoid negative, reactions from others. Importantly, the interacting partners need not be aware of these expectations for them to take effect.

The second process by which gender stereotypes translate into gender differences is the self-regulation of behavior based on identity processes and the internalization of stereotypes (e.g., Bem, 1981 ; Markus, 1977 ). Most people form their gender identity based on self-categorization as male or female and subsequently incorporate attributes associated with the respective category into their self-concept (Guimond, Chatard, Martinot, Crisp, & Redersdorff, 2006 ). These gendered differences in the self-concepts of women and men then translate into gender-stereotypical behaviors. The extent to which the self-concept is affected by gender stereotypes—and in turn the extent to which gendered patterns of behavior are displayed—depends on the strength and the salience of this social identity (Hogg & Turner, 1987 ; Onorato & Turner, 2004 ). For example, individuals may be more likely to display gender-stereotypical behavior when they identify more strongly with their gender (e.g., Lorenzi‐Cioldi, 1991 ) or when their gender is more likely to be salient, which is more likely to be the case for women (Cadinu & Galdi, 2012 ).

However, many different subcategories of women exist—housewives, feminists, lesbians—and thus what it means to identify as a woman, and behave like a woman, is likely to be complex and multifaceted (e.g., Fiske et al., 2002 ; van Breen, Spears, Kuppens, & de Lemus, 2017 ). Moreover, research demonstrates that the salience of gender in any given context also determined the degree to which an individual displays gender-stereotypical behavior (e.g., Ryan & David, 2003 ; Ryan, David, & Reynolds, 2004 ). For example, Ryan and colleagues demonstrate that while women and men act in line with gender stereotypes when gender and gender difference are salient, these differences in attitudes and behavior disappear when alternative identities, such as those based on being a student or being an individual, are made salient.

Gender Stereotypes Affect Performance and Achievement

The consequences of stereotypes go beyond the self-concept and behavior. Research in stereotype threat describes the detrimental effects that negative stereotypes can have on performance and achievement. Stereotype threat refers to the phenomenon whereby the awareness of the negative stereotyping of one’s group in a certain domain, and the fear of confirming such stereotypes, can have negative effects on performance, even when the stereotype is not endorsed. The phenomenon was first described by Steele and Aronson ( 1995 ) in the context of African Americans’ intellectual test performance, but has since been found to affect women’s performance and motivation in counterstereotypical domains such as math (Nguyen & Ryan, 2008 ) and leadership (Davies, Spencer, & Steele, 2005 ). This affect holds true even when minority group members’ prior performance and interest in the domain are the same as those of majority group members (Spencer, Steele, & Quinn, 1999 ). Moreover, the effect is particularly pronounced when the minority member’s desire to belong is strong and identity-based devaluation is likely (Steele, Spencer, & Aronson, 2002 ).

Different mechanisms for the effect of stereotype threat have been proposed. Schmader, Johns, and Forbes ( 2008 ) suggest that the inconsistency between one’s self-image as competent and the cultural stereotype about one’s group’s lack of competence leads to a physiological stress response that directly impairs working memory. For example, when made aware of the widely held stereotype that women are bad at math, a female math student is likely to experience an inconsistency. This inconsistency, the authors argue, is not only distressing in itself, but induces uncertainty: Am I actually good at math or am I bad at math as the stereotype would lead me to believe? In an effort to resolve this uncertainty, she is likely to monitor her performance more than others—and more than in a situation in which stereotype threat is absent. This monitoring leads to more conscious, less efficient processing of information—for example, when performing calculations that she would otherwise do more or less automatically—and a stronger focus on detecting potential failure, taking cognitive resources away from the actual task. Moreover, individuals under stereotype threat are more likely to experience negative thoughts and emotions such as fear of failure. In order to avoid the interference of these thoughts, they actively try to suppress them. This suppression, however, takes effort. All of these mechanisms, the authors argue, take working memory space away from the task in question, thereby impairing performance.

The aim of this article is to give an overview of gender research in social psychology, which has focused predominantly on gender stereotypes, their origins, and their consequences, and these are all connected and reinforce each other. Social psychology has produced many fascinating findings regarding gender, and this article has only just touched on these findings. While research into gender has seen a great growth in the past 50 years and has provided us with an unprecedented understanding of women and men and the differences (and similarities) between them, there is still much work to be done.

There are a number of issues that remain largely absent from mainstream social psychological research on gender. First, an interest and acknowledgment of intersectional identities has emerged, such as how gender intersects with race or sexuality. It is thus important to note that many of the theories discussed in this article cannot necessarily be applied directly across intersecting identities (e.g., to women of color or to lesbian women), and indeed the attitudes and behaviors of such women continue to be largely ignored within the field.

Second, almost all social psychological research into gender is conducted using an overly simplistic binary definition of gender in terms of women and men. Social psychological theories and explanations are, for the most part, not taking more complex or more fluid definitions of gender into account and thus are unable to explain gendered attitudes and behavior outside of the gender binary.

Finally, individual perceptions and cognitions are influenced by gendered stereotypes and expectations, and social psychologists are not immune to this influence. How we, as psychologists, ask research questions and how we interpret empirical findings are influenced by gender stereotypes (e.g., Hegarty & Buechel, 2006 ), and we must remain vigilant that we do not inadvertently seek to reinforce our own gendered expectations and reify the gender status quo.

- Barreto, M. , Ellemers, N. , Piebinga, L. , & Moya, M. (2010). How nice of us and how dumb of me: The effect of exposure to benevolent sexism on women’s task and relational self-descriptions. Sex Roles , 62 , 532–544.

- Baumeister, R. F. (2013) Gender differences in motivation shape social interaction patterns, sexual relationships, social inequality, and cultural history. In M. K. Ryan & N. R. Branscombe (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of gender and psychology . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE

- Becker, J. C. , & Wright, S. C. (2011). Yet another dark side of chivalry: Benevolent sexism undermines and hostile sexism motivates collective action for social change. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 101 , 62–77.

- Bem, S. L. (1981). Gender schema theory: A cognitive account of sex typing. Psychological Review , 88 , 354–364

- Buss, D. M. (2016). The evolution of desire . In T. K. Shackelford & V. A. Weekes-Shackelford (Eds.), Encyclopedia of evolutionary psychological science . Cham, SZ: Springer.

- Cadinu, M. , & Galdi, S. (2012). Gender differences in implicit gender self‐categorization lead to stronger gender self‐stereotyping by women than by men. European Journal of Social Psychology , 42 , 546–551.

- Cuddy, A. J. C. , Fiske, S. T. , & Glick, P. (2007). The BIAS map: Behaviors from intergroup affect and stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 92 , 631–648.

- Cuddy, A. J. C. , Fiske, S. T. , Kwan, V. S. Y. , Glick, P. , Demoulin, S. , Leyens, J.-P. , . . . & Ziegler, R. (2009). Stereotype content model across cultures: Towards universal similarities and some differences. British Journal of Social Psychology , 48 , 1–33.

- Dardenne, B. , Dumont, M. , & Bollier, T. (2007). Insidious dangers of benevolent sexism: Consequences for women’s performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 93 , 764–779.

- Davies, P. G. , Spencer, S. J. , & Steele, C. M. (2005). Clearing the air: Identity safety moderates the effects of stereotype threat on women’s leadership aspirations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 88 , 276–287.

- Deaux, K. , & Major, B. (1987) Putting gender into context: An interactive model of gender-related behavior. Psychological Review , 94 , 369–389.

- Eagly, A. H. (1987). Sex differences in social behavior: A social role interpretation . Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Eagly, A. H. , Eaton, A. , Rose, S. , Riger, S. , & McHugh, M. (2012). Feminism and psychology: Analysis of a half-century of research on women and gender. American Psychologist , 67 , 211–230.

- Eagly, A. H. , & Karau, S. J. (2002). Role congruity theory of prejudice towards female leaders. Psychological Review , 109 , 573–598.

- Eagly, A. H. , Wood, W. , & Diekman, A. B. (2000). Social role theory of sex differences and similarities: A current appraisal. In T. Eckes & H. M. Trautner (Eds.), The developmental social psychology of gender (pp. 123–174). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Eckes, T. (2002). Paternalistic and envious gender stereotypes: Testing predictions from the stereotype content model. Sex Roles , 47 , 99–114.

- Etaugh, C. (2016). Psychology of gender: History and development of the field. In N. Naples , R. C. Hoogland , M. Wickramasinghe , & W. C. A. Wong (Eds.), The Wiley Blackwell encyclopedia of gender and sexuality studies , (pp. 1–12). Hoboken, (NJ): John Wiley & Sons.

- Fine, C. (2010). Delusions of gender: How our minds, society, and neurosexism create difference . New York: Norton.

- Fiske, S. T. (2000). Stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination at the seam between the centuries: Evolution, culture, mind, and brain. European Journal of Social Psychology , 30 , 299–322.

- Fiske, S. T. , Cuddy, A. J. C. , Glick, P. , & Xu, J. (2002). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 82 , 878–902.

- Fiske, S. T. , & Stevens, L. E. (1993). What’s so special about sex? Gender stereotyping and discrimination. In S. Oskamp & M. Costanzo (Eds.), Gender issues in contemporary society (pp. 173–196). Newbury Park, CA: SAGE.

- Glick, P. , & Fiske, S. T. (1996). The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 70 , 491–512.

- Glick, P. , & Fiske, S. T. (1999). The Ambivalence toward Men Inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent beliefs about men. Psychology of Women Quarterly , 23 , 519–536.

- Glick, P. , & Fiske, S. T. (2001). An ambivalent alliance: Hostile and benevolent sexism as complementary justifications of gender inequality. American Psychologist , 56 , 109–118.

- Glick, P. , Fiske, S. T. , Mladinic, A. , Saiz, J. L. , Abrams, D. , Masser, B. , . . . & López, W. L. (2000). Beyond prejudice as simple antipathy: Hostile and benevolent sexism across cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 79 (5), 763–775.

- Glick, P. , Lameiras, M. , Fiske, S. T. , Eckes, T. , Masser, B. , Volpato, C. , . . . & Wells, R. (2004). Bad but bold: Ambivalent attitudes toward men predict gender inequality in 16 nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 86 (5), 713–728.

- Guimond, S. , Chatard, A. , Martinot, D. , Crisp, R. J. , & Redersdorff, S. (2006). Social comparison, self-stereotyping, and gender differences in self-construals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 90 , 221.

- Haines, E. L. , Deaux, K. , & Lofaro, N. (2016). The times they are a-changing . . . or are they not? A comparison of gender stereotypes, 1983–2014. Psychology of Women Quarterly , 40 (3), 1–11.

- Hall, G. S. (1904). Adolescence: Its psychology and its relations to physiology, anthropology, sociology, sex, crime, religion, and education . New York: D. Appleton.

- Hegarty, P. , & Buechel, C. (2006). Androcentric reporting of gender differences in APA journals: 1965–2004. Review of General Psychology , 10 (4), 377.

- Heilman, M. E. (1983). Sex bias in work settings: The lack of fit model. In B. Staw & L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior (Vol. 5). Greenwich, CT: JAI.

- Heilman, M. E. (1995). Sex stereotypes and their effects in the workplace: What we know and what we don’t know. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality , 10 , 3–26.

- Heilman, M. E. (2001). Description and prescription: How gender stereotypes prevent women’s ascent up the organizational ladder. Journal of Social Issues , 57 , 657–674.

- Hogg, M. , & Turner, J. C. (1987). Intergroup behaviour, self-stereotyping and the salience of social categories. British Journal of Social Psychology , 26 , 325–340.

- Leyens, J-Ph. , Yzerbyt, V. , & Schadron, G. (1994). Stereotypes, social cognition, and social explanation . London: SAGE.

- Lorenzi-Cioldi, F. (1991). Self‐stereotyping and self‐enhancement in gender groups. European Journal of Social Psychology , 21 (5), 403–417.

- Maccoby, E. E. , & Jacklin, C. N. (1974). The psychology of sex differences . Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Macrae, C. N. , Milne, A. B. , & Bodenhausen, G. V. (1994). Stereotypes as energy-saving devices: A peek inside the cognitive toolbox. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 66 , 37–47.

- Markus, H. R. (1977). Self-schemata and processing information about the self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 35 , 63–78.

- Moss-Racusin, C. A. , Phelan, J. E. , & Rudman, L. A. (2010). When men break the gender rules: Status incongruity and backlash toward modest men. Psychology of Men and Masculinity , 11 , 140–151.

- Nguyen, H. D. , & Ryan, A. M. (2008). Does stereotype threat affect test performance of minorities and women? A meta-analysis of experimental evidence. Journal of Applied Psychology , 93 , 1314–1334.

- Onorato, R. S. , & Turner, J. C. (2004). Fluidity in the self‐concept: the shift from personal to social identity. European Journal of Social Psychology , 34 , 257–278.

- Rojahn, K. , & Pettigrew, T. F. (1992). Memory for schema-relevant information: A meta-analytic resolution. British Journal of Social Psychology , 31 , 81–109.

- Rudman, L. A. (1998). Self-promotion as a risk factor for women: The costs and benefits of counterstereotypical impression management. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 74 , 629–645.

- Rudman, L. A. , & Glick, P. (2001). Prescriptive gender stereotypes and backlash toward agentic women. Journal of Social Issues , 57 , 743–762.

- Rudman, L.A. , & Mescher, K. (2013). Penalizing men who request a family leave: Is flexibility stigma a femininity stigma? Journal of Social Issues , 69 , 322–340.

- Ryan, M. K. , & David, B. (2003). Gender differences in ways of knowing: The context dependence of The Attitudes Toward Thinking and Learning Survey. Sex Roles , 49 , 693–699.

- Ryan, M. K. , David, B. , & Reynolds, K. J. (2004). Who cares?: The effect of context on self-concept and moral reasoning. Psychology of Women Quarterly , 28 , 246–255.

- Ryan, M. K. , Haslam, S. A. , Hersby, M. D. , & Bongiorno, R. (2011). Think crisis—think female: The glass cliff and contextual variation in the think manager—think male stereotype. Journal of Applied Psychology , 96 , 470–484.

- Schein, V. E. (1973). The relationship between sex-role stereotypes and requisite management characteristics. Journal of Applied Psychology , 57 , 95–100.

- Schmader, T. , Johns, M. , & Forbes, C. (2008). An integrated process model of stereotype threat effects on performance. Psychological Review , 115 , 336–356.

- Spencer, S. J. , Steele, C. M. , & Quinn, D. M. (1999). Stereotype threat and women’s math performance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology , 35 , 4–28.

- Steele, C. M. , & Aronson, J. (1995). Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 69 , 797–811.

- Steele, C. M. , Spencer, S. J. , & Aronson, J. (2002). Contending with group image: The psychology of stereotype and social identity threat. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 34, pp. 379–440). San Diego, CA: Academic Press

- Van Breen, J. A. , Spears, R. , Kuppens, T. , & de Lemus, S. (2017). A multiple identity approach to gender: Identification with women, identification with feminists, and their interaction. Frontiers in Psychology , 8 , 1019.

- Vaughan, G. M. , & Hogg, M. A. , (2011). Introduction to Social Psychology (6th ed.). Sydney: Pearson Australia.

- Weisstein, N. (1968). “Kinder, kuche, kirche” as scientific law: Psychology constructs the female . Boston, MA: New England Free Press.

- Wood, W. , & Eagly, A. H. (2002). A cross-cultural analysis of the behavior of women and men: Implications for the origins of sex differences. Psychological Bulletin , 128 , 699–727.

1. Psychology largely conceptualizes gender as binary. While this is problematic in a number of ways, which we touch upon in the Conclusion section, we largely follow these binary conventions throughout this article, as it is representative of the social psychological literature as a whole.

Related Articles

- Gender and Cultural Diversity in Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology

- Social Categorization

- Self and Identity

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Psychology. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 22 April 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|81.177.182.174]

- 81.177.182.174

Character limit 500 /500

The Palgrave Handbook of Power, Gender, and Psychology

- © 2023

- Eileen L. Zurbriggen ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0007-9452-4081 0 ,

- Rose Capdevila ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3014-6938 1

University of California, Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, USA

You can also search for this editor in PubMed Google Scholar

The Open University, Milton Keynes, UK

- The first handbook on theories of gender and power in feminist psychology

- Explores how individual experience of body, self, and world are constituted in social structures and symbolic systems

- Discusses current debates, including the Me Too movement, reproduction rights, and gender in the developing world

10k Accesses

1 Citations

15 Altmetric

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this book

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

Licence this eBook for your library

Institutional subscriptions

Table of contents (33 chapters)

Front matter, introduction: feminist theorizing on power, gender, and psychology.

- Rose Capdevila, Eileen L. Zurbriggen

Setting the Stage

Power/history/psychology: a feminist excavation.

- Natasha Bharj, Katherine Hubbard

Beyond Identity: Intersectionality and Power

- Elizabeth R. Cole

Institutions and Settings

A feminist psychology of gender, work, and organizations.

- Lucy Thompson

“To Be Treated as a Thing”: Discussing Power Relations with Children in a Public School in Rio de Janeiro

- Amana Rocha Mattos, Gabriela de Oliveira Moura e Silva

‘You Feel Like You’re Throwing Your Life Away Just to Make It Look Clean’: Insights into Women’s Everyday Management of Hearth and Home in Wales

- Louise Folkes, Dawn Mannay

Politics, Citizenship, and Activism

Gender, power, and participation in collective action.

- Lauren E. Duncan

The Gendering of Trauma in Trafficking Interventions

- Ingrid Palmary

Surveillance and Gender-Based Power Dynamics: Psychological Considerations

- Sarah Camille Conrey, Eileen L. Zurbriggen

Toward an Intersectional Understanding of Gender, Power, and Poverty

- Heather E. Bullock, Melina R. Singh

Dismantling the Master’s House with the Mistress’ Tools? The Intersection Between Feminism and Psychology as a Site for Decolonization

- Natasha Bharj, Glenn Adams

Bodies and Identities

Men and masculinities: structures, practices, and identities.

- Jeff Hearn, Sam de Boise, Klara Goedecke

Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual (LGB) Identities

- Joanna Semlyen, Sonja Ellis

The Power of Self-Identification: Naming the “Plus” in LGBT+

- T. Evan Smith, Megan R. Yost

Transnormativity in the Psy Disciplines: Constructing Pathology in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual and Standards of Care

- Damien W. Riggs, Ruth Pearce, Carla A. Pfeffer, Sally Hines, Francis Ray White, Elisabetta Ruspini

- Feminist Psychology

- Women's Studies

- Sexuality Studies

- Women's Bodies

- Liberation Psychology

- Liberation Studies

- Critical Approaches

About this book

The Palgrave Handbook of Power, Gender, and Psychology takes an intersectional feminist approach to the exploration of psychology and gender through a lens of power. The invisibility of power in psychological research and theorizing has been critiqued by scholars from many perspectives both within and outside the discipline. This volume addresses that gap. The handbook centers power in the analysis of gender, but does so specifically in relation to psychological theory, research, and praxis. Gathering the work of sixty authors from different geographies, career stages, psychological sub-disciplines, methodologies, and experiences, the handbook showcases creativity in approach, and diversity of perspective. The result is a work featuring a chorus of different voices, including diverse understandings of feminisms and power. Ultimately, the handbook presents a case for the importance of intersectionality and power for any feminist psychological endeavor.

Abigail Stewart, Sandra Schwartz Tangri Distinguished University Professor of Psychology and Women's and Gender Studies, University of Michigan, USA

The Palgrave Handbook of Power, Gender,and Psychology brings together an impressive array of chapters showcasing the incisiveness and importance of feminist psychologies that foreground power relations in their analyses and applications. The book features key feminist writers from around the world, tackles a broad range of topics and approaches, and highlights the necessity of careful, reflexive scholarship aimed at understanding gender and psychology. It should be standard reading for psychology students, academics, and practitioners.

Catriona Macleod, Distinguished Professor of Psychology and SARChI Chair of Critical Studies in Sexualities and Reproduction, Rhodes University, South Africa

Erica Burman, Professor of Education, Manchester Institute of Education, School of Environment, Education and Development, The University of Manchester, UK

Intersectionality is a cornerstone of contemporary feminist psychology, and power analysis is crucial to intersectionality. Yet as intersectionality has diffused into many areas of psychology, the power analysis has often been lost. This book is a healthy corrective, with its emphasis on and elaboration of the centrality of power in the psychology of gender. It is a must-read for any psychologist who aspires to apply an intersectional approach in their work.

Janet Shibley Hyde, Professor Emerit of Psychology and Gender & Women’s Studies, University of Wisconsin—Madison, USA

I am delighted to endorse this luscious collection of transnational essays on power and gender in psychology. Written in the ink of intersectionality and feminism, taking seriously racial capitalism, hetero-patriarchy, local context and herstories, disability and reproductive justice, these essays crucially center questions of power and gender just at a time when right wing/fascist regimes rise across the globe endangering women, femmes and trans folx, rolling back gender justice movements.

This book erupts just when it is needed – to be taught/read/critiqued/extended in schools and community settings; in clinics and kitchens; in bedrooms and childcare settings; in butcher shops and hair salons; in libraries, welfare offices, immigration centers and in the bathrooms of religious spaces; on line and in music… wherever gender is being performed and transformed/silenced and flaunted/re-imaginedand queered through a radical intersectional lens, structurally and intimately.

Michelle Fine, Distinguished Professor of Critical Psychology and Women/Gender Studies at the Graduate Center, CUNY, USA and Visiting Professor, University of South Africa, RSA

The Handbook of Power, Gender, and Psychology is a much-needed intervention to acknowledge and credit feminist scholarship and analysis across multiple domains of study. Its contributors name feminist scholarship as foundational to understanding these domains and they engage its urgent analytic and applied value with rich nuance.

Bonnie Moradi, Professor of Psychology, Director, Center for Gender, Sexualities, and Women’s Studies Research, University of Florida, USA

Peter Hegarty, Professor in Psychology, The Open University, UK

A stunningly expansive collection of field-leaders and emerging voices who represent the vanguard of critical approaches to power,psychology, intersectionality, and social transformation. Both theoretically rich and deeply accessible, Zurbriggen, Capdevila, and their contributors show how feminist psychology can redefine the terms of engagement at this pressing moment in human history, social science, and global democracy. This volume will be the definitive resource for feminist political psychology for at least a generation.

Patrick R. Grzanka, Professor and Dean for Social Sciences, University of Tennessee, President (2023-2024), Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues, USA

Hallelujah! A significant and timely collection that addresses the core issue of gender construction that psychology largely glosses over: Power. Who has a right to be heard? Who has standing as a citizen? How is gender constructed as a means to control access to power and autonomy? This book is a game-changer and should be in the hands of every gender researcher in the psychologicalsciences. Now!

Stephanie A. Shields, Professor Emeritx, Psychology & Women's, Gender, & Sexuality Studies, The Pennsylvania State University, USA

As a scholar of objectification for 30 years, I’ve bemoaned how our individualist-centered field and broader neoliberal cultural framing of gender reduces research and intervention to the rigged game of “empowerment feminism.” Our current political climate demands that we replace this essentializing, divisive approach with one that centers power dynamics. Enter Zurbriggen and Capdevila’s outstanding volume, with feminist psychological science and theory, across a vast array of sites where gender and power intersect, to provide a truly empowering foundation for the collective action necessary to create a more equitable society.

Tomi-Ann Roberts, Professor of Psychology, Colorado College, USA

Janice D. Yoder, Academic Affiliate Professor of Psychology and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, The Pennsylvania State University, USA

Across a wide variety of social, personal, and physical domains, gender and power are metaphors and models for each other. In The Palgrave Handbook of Power, Gender, and Psychology , a geographically and generationally wide range of authors explore these connections in a wide range of topics, fields, and disciplines both traditional and innovative – including the complicity of psychology. The book is an encyclopedic guide to concepts, theories, examples, and strategies to change how power and gender are linked, in everyday life as well as academic disciplines. References and suggestions for further exploration abound.

David G. Winter, Emeritus Professor of Psychology, University of Michigan, USA

Power, Gender and Psychology is not only an extraordinary achievement, but a gift to scholars and practitioners. Impressive in its sweep and range, it brings together the best of contemporary research on gender and psychology, is not afraid to ask challenging questions, and keeps power centre-stage in all its interrogations – from new technologies to mental health, to sexual harassment to work and care. An absolutely essential contribution that will be a source book for years to come.

Rosalind Gill , Professor of Cultural and Social Analysis, City University London, UK

Editors and Affiliations

Eileen L. Zurbriggen

Rose Capdevila

About the editors

Eileen L. Zurbriggen is Distinguished Professor of Psychology at the University of California, Santa Cruz, USA where she is also affiliated with the Feminist Studies department. Her most recent book, co-authored with Ella Ben Hagai, is Queer Theory and Psychology: Gender, Sexuality, and Transgender Identities (2022).

Rose Capdevila is Professor of Psychology at the Open University, UK. Her current research is on gender in digital spaces and the history of UK feminist psychology. Rose is a past co-editor of Feminism & Psychology and co-authored A Feminist Companion to Research Methods in Psychology (2022) with Hannah Frith.

Bibliographic Information

Book Title : The Palgrave Handbook of Power, Gender, and Psychology

Editors : Eileen L. Zurbriggen, Rose Capdevila

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-41531-9

Publisher : Palgrave Macmillan Cham

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology , Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Copyright Information : The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2023

Hardcover ISBN : 978-3-031-41530-2 Published: 29 December 2023

Softcover ISBN : 978-3-031-41533-3 Due: 29 January 2024

eBook ISBN : 978-3-031-41531-9 Published: 28 December 2023

Edition Number : 1

Number of Pages : XXV, 628

Number of Illustrations : 1 b/w illustrations, 1 illustrations in colour

Topics : Gender Studies , Counselling and Interpersonal Skills , Community and Environmental Psychology , Feminism , Women's Studies

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Module 1 What is the Psychology of Gender?

What are little boys made of snips and snails and puppy-dogs’ tails that’s what little boys are made of, what are little girls made of sugar and spice and everything nice that’s what little girls are made of, the central concepts.

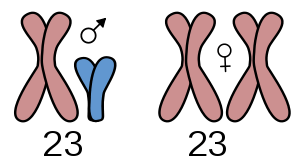

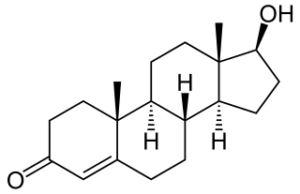

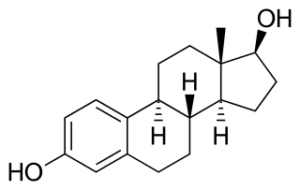

Sex is used to categorize people based on genetic, chromosomal, and anatomical differences as male, female, or intersex, often thought of as biologically determined . Gender refers to the social meanings ascribed to people who belong to a particular sex . The reality of these two terms is more complicated. While traditionally, sex has been thought of as untainted by societal influences, and gender as socially constructed, the argument can be made that both terms are socially constructed. As you will see in a later module, there are several biological markers for femaleness and maleness , but most cultures use only one of those markers to assign babies to a particular sex, the external genitalia. However, nature lies. There may be a mismatch between internal and external reproductive systems, or between chromosomes and external genitalia. The sex and gender binaries are a social system that consists of two non-overlapping, opposing groups. Male and female, and masculine and feminine are used in most, but not all cultures, as they simplify interactions between societal members, aid in organizing division of labor, and help maintain social institutions (Bosson et al., 2019). However, our understanding of research into sex and gender has moved beyond the constraints of a binary system. Both variables currently include a range of categories that better fit to an individual’s own self-identification.

Gender Identity refers to a person’s psychological sense of being male, female, both, or neither . Categories of gender identity include:

- Cisgender or cis refers to individuals who identify with the gender assigned to them at birth . Some people prefer the term non-trans.

- Transgender generally refers to individuals who identify as a gender not assigned to them at birth. A gender transition is based on one’s identity and social expressions. Some individuals who transition do not experience a change in their gender identity since they have always identified in the way that they do . The term is used as an adjective (i.e., “a transgender woman,” not “a transgender”), however some individuals describe themselves by using transgender as a noun. The term transgendered is not preferred because it undermines self-definition.

- Trans is an abbreviated term, and individuals appear to use it self-referentially more often than transgender (Tompkins, 2014).

- Non-binary and genderqueer refer to gender identities beyond binary identifications of man or woman . The term genderqueer became popularized within the queer and trans communities in the 1990s and 2000s, and the term non-binary became popularized in the 2010s (Roxie, 2011).

- Agender , meaning “without gender,” can describe people who do not have a gender identity, while others identify as non-binary or gender neutral, have an undefinable identity, or feel indifferent about gender (Brooks, 2014).

- Genderfluid which highlights that people can experience shifts between gender identities .

Additional gender identity terms exist; these are just a few basic and commonly used terms. Again, the emphasis of these terms is on viewing individuals as they view themselves and using self-designated names and pronouns.

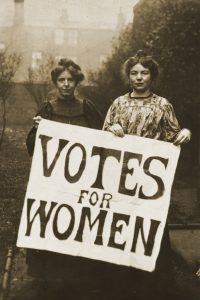

A Brief History of the Women’s Movement in the U.S.

Feminism , also known as the feminist or women’s movement, encompasses many social movements that emphasize improving women’s lives and rectifying gender inequality in society (Young, 1997). Overtime the focus has shifted as gains were made, or circumstances changed. The issues have ranged from women’s right to vote, hold property, receive equal pay and employment opportunity, reproductive rights, domestic violence, sexual harassment, and sexual violence and exploitation. Given the diversity of issues and voices that have been added to the movement it is described as having four waves.

What has come to be called the “first wave” of the feminist movement in the Unites States began in the mid-19th century and lasted to the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920, which gave women the right to vote. White middle-class suffragists, such as Elizabeth Clay Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, focused on women’s suffrage , that is, the right to vote. Suffragists also worked on striking down coverture laws , which stated upon marriage a woman could no longer own property or enter into contract in her own name, and a woman’s right to education and employment (Kang et al., 2017).

Demanding women’s equality, the abolition of coverture, and access to employment and education were quite radical demands at the time. These demands confronted the ideology of the cult of true womanhood , summarized in four key tenets: piety, purity, submission and domesticity . These held that women were rightfully and naturally located in the private sphere of the household and not fit for public, political participation, or labor in the waged economy (Kang et al., 2017) . However, this emphasis on confronting the ideology of the cult of true womanhood was shaped by the white middle-class standpoint of the leaders of the movement. This leadership shaped the priorities of the movement, often excluding the concerns and participation of working-class women and women of color.

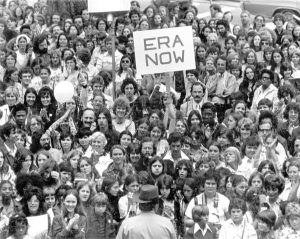

Second Wave

The “second wave” of feminism, from 1920-1980, focused generally on fighting patriarchal structures of power, and specifically on combating occupational sex segregation in employment and fighting for reproductive rights for women (Kang et al., 2017). The Civil Rights Act of 1964, a major legal victory for the civil rights movement, not only prohibited employment discrimination based on race, but Title VII of the Act also prohibited sex discrimination. When the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), the federal agency created to enforce Title VII, largely ignored women’s complaints of employment discrimination, 15 women and one man organized to form the National Organization of Women (NOW). NOW focused its attention and organizing on the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), fighting sex discrimination in education, and defending Roe v. Wade , the Supreme Court decision of 1973 that struck down state laws that prohibited abortion within the first three months of pregnancy.

White women were not the only women spearheading feminist movements. As historian Thompson (2002) argues, in the mid and late 1960s, Latinx women, African American women, and Asian American women were developing multiracial feminist organizations that would become important players within the U.S. second wave feminist movement. However, during this era Black women writers and activists such as Alice Walker, bell hooks, and Patricia Hill Collins developed Black feminist thought as a critique of the ways in which some second wave feminists still ignored racism and class oppression and how they uniquely impact women and men of color and working-class people. bell hooks (1984) argued that feminism cannot just be a fight to make women equal with men, because such a fight does not acknowledge that all men are not equal in a capitalist, racist, and homophobic society. Sexism cannot be separated from racism, classism and homophobia, and that these systems of domination overlap and reinforce each other. These critiques led to the third wave of feminism.

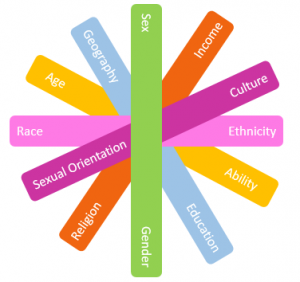

“Third wave” feminism came directly out of the experiences of feminists in the late 20th century who grew up in a world that supposedly did not need social movements because “equal rights” for racial minorities, sexual minorities, and women had been guaranteed by law in many countries (Kang et al., 2017). However, the gap between law and reality, between the abstract proclamations of states and concrete lived experience, revealed the necessity of both old and new forms of activism. Moreover, third-wave feminism criticized second wave feminism’s focus on the universality of women’s experiences. Emerging from the criticism of Black feminists, third wave feminism emphasized the concept of intersectionality. Intersectionality vie ws race, class, gender, sexuality, age, ability, and other aspects of identity as mutually constitutive ; that is, people experience these multiple aspects of identity simultaneously and the meanings of different aspects of identity are shaped by one another .

Fourth Wave

Currently we are in the “fourth wave”, and fourth wavers are not just the reincarnation of their second and third wave grandmothers and mothers. There is a greater emphasis on intersectionality and the diversity of women (Ramptom, 2015). It has borrowed from third wave feminist and understanding that feminism is part of a larger context of oppression, along with ageism, racism, ableism, classism, and those of different sexual orientations. But f ourth wave feminism also rejects the gender binary and focuses on transgender issues. As Ramptom writes “feminism no longer just refers to the struggles of women; it is a clarion call for gender equity” (p.7). Gender equality was the focus of much of the women’s movement. Gender equality refers to not discriminating on the basis of a person’s gender when it comes to access to services, the allocation of resources, or opportunities (McRaney et al. 2021). Gender equity refers to there being fairness and justice in the distribution of resources and responsibilities on the basis of gender (McRaney, et al., 2021).

Fourth wavers have also capitalized on technological advances to promote their campaigns and raise public awareness to gain support (National Women’s History Museum, 2021). Hashtags such as #YesAllWomen, #BringBackOurGirls, and #MeToo have promoted the experiences that women have with violence and harassment. Social media has also galvanized marches in various cities and in the nations capital. Fourth wavers are now more global in their message and in their membership (National Women’s History Museum, 2021).

Feminist Theories

Feminist theory grew out of the feminist/women’s movement that began around 1830 in the United States and Europe. Feminist theory actually consists of many different perspectives, as no single person or perspective is the main authority. Although focusing on different aspects of the female experience, all feminist theories advocate for eliminating gender inequalities and oppression. According to Else-Quest and Hyde (2018), the following are the major points of feminist theories:

- Gender is socially constructed. Feminist theories emphasize that individual cultures and societal influences create and maintain gender roles that perpetuate gender inequality, male domination, and female subjugation. Due to women’s perceived lower status, they are discriminated against in diverse ways, including academically, politically, economically, and interpersonally.

- Men exercise power and control over women . Because men have seized power, they use that power in interpersonal relationships, including rape and domestic violence, in politics by passing laws that harm women, and economically by supporting different pay scales for jobs reflecting traditional gender roles. Men’s sense of entitlement and privilege allow them to exert power without fear of consequences.

- Women’s problems are due to external factors rather than internal factors. Mental health disorders in women, and being the victims of violence, are often viewed as being due to internal/personal reasons. This includes that women are naturally more emotional, and therefore more likely to suffer from a mental health disorder, or they dressed provocatively and therefore were responsible for being raped. Instead, feminist theories see external factors, such as sexism, discrimination, male aggression, and female inequality as the reasons for problems faced by women.

- Consciousness raising is an important aspect of all theories. Consciousness raising involves women first sharing their experiences and reflecting on them. Next, they engage in an analysis of their feelings and experiences. Lastly, they develop action plans to address any negative consequences from their experiences. This could include political or social actions, as well as making changes in interpersonal relationships.

Others have noted that feminist theory, as a collective, is a theoretical position which examines the world through the lens of gender but has a focus that is varied and wide-ranging (Evans, 2014). Thus, feminism is not afraid to engage in issues outside of gender, and understands that changes in the everyday circumstances of people’s lives, such as technology and even the outward trappings of society, does not inevitably bring with it changes in power, privilege, and authority. Many view that it is the role of feminist theory to challenge much of our social knowledge, which has always been supported by, and maintained, the authority of men.

According to Else-Quest and Hyde (2018), Renzetti et al. (2012), and Kang et al., (2017) there are several major types of feminist theory and they include:

Liberal Feminism holds that women and men are equal and should have the same opportunities. Liberal feminists tend to work within the current system for change to ensure that women have full access to legal, educational and career opportunities. The National Organization for Women (NOW) reflects liberal feminism, and this organization worked to pass the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) which states, “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex” (Else-Quest & Hyde, 2018, p. 6). The ERA was passed in the House of Representatives and Senate in 1972, and finally has been ratified by all the 38 states needed to pass it, with Illinois becoming the 37th state May 30, 2018, and Virginia becoming the 38th on January 27, 2020. However, Congress set a 1982 deadline to ratify ERA, so the gesture by these states may be more symbolic. Moreover, several states (Idaho, Kentucky, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Tennessee) have voted to rescind their earlier ratification. However, states can only ratify an amendment, according to Article V of the constitution; they do not have the power to rescind a ratification (Equal Rights Amendment.org, 2018). This means the question of ERA is still in legal limbo.

Cultural Feminism, unlike liberal feminism, believes that women have special and unique qualities that have been devalued by a patriarchal society. The emphasis of cultural feminism is that these qualities, including nurturing, connectedness, and intuition, need to be elevated in society.

Radical Feminism opposes current political and social organizations because they are tied to patriarchy and the domination of women by men. Radical-cultural feminism argues that feminine values, such as interdependence, are preferable to masculine values, such as autonomy and dominance, and therefore men should strive to be more feminine. In contrast, Radical-libertarian feminism focuses on how femininity limits women and instead advocates for female androgyny. Because changing the current patriarchal society will be a difficult process, some radical feminists advocate for separate societies where women can work together free from men.

Women-of-Color Feminism promotes an intersectional model of feminism that emphasizes the unique situation of women of color being in multiple marginalized groups. The diversity of women’s experiences is considered more important than universal female experiences.

Marxist/Socialist Feminism concludes that the oppression of women is an example of class oppression based on a capitalist system. Women’s lower wages, for example, benefit corporate profits and the current capitalist economic system. Marxist/Socialist feminists argue that there should be no such category as “women’s work”, and they believe that women’s status will only improve with a major reform of American society.

Postmodern Feminism views sex and gender as socially determined scripts. They do not support a dualistic view of gender, heteronormativity, or biological determinism Instead, postmodern feminists see gender and sexuality as more fluid. Postmodern feminism is part of the fourth wave of feminism that is evident today.

Ecofeminism is concerned with environmentalism, and some of the most powerful leaders in the environmental movement have been women. Ecofeminism emerged in the 1970s and supports an earth-based spirituality movement that incorporates goddess imagery, female reproduction, healing, and a belief that all living beings are equal and should be respected. Ecofeminism also incorporates a wide range of intersectionality, including women of color, poor women, women with disabilities, and those who are trans and non-gender conforming. Historically, marginalized groups have experienced the brunt of extreme weather, unlawful working conditions, and exposure to toxins and pollution. Ecofeminism looks at these environmental issues through a social justice lens, critically analyzes their effects, and supports the needs of affected, marginalized people (Villalobos, 2017). Additionally, ecofeminism analyzes how western economic models have exploited and discriminated against those in economically underdeveloped societies

Ecofeminism also rejects a patriarchal society that is believed to harm both women and nature. The same societal structures (sexism, racism, classism) that oppress women and minorities, are also believed to be exploiting the environment. Applying ecofeminism in practice incorporates the blending of biocentricism, which endorses inherent value to all living things , and anthropocentricism , which focuses on humans being the most important entity in the universe. Ecofeminists support the needs of both nature and humans, and they encourage those with privilege t o use it for good by advocating with, and on behalf of, others.

Because the women’s liberation movement was seen as a white movement, and the black liberation movement was largely seen as a black male movement, Black feminist activists founded the National Black Feminist Organization (NBFO) in 1973. The NBFO was the first explicitly Black feminist organization in the United States (Few, 2007). The NBFO resulted not only from Black women’s frustration with racism in the women’s movement, but also a desire to raise the consciousness and connections of all Black women. Black feminists focused on defining themselves and rejecting internalized oppression as a way of fighting sexism and racism. Current Black feminists look to popular culture (e.g., hip-hop) and art (e.g., performance, photography, dance) to analyze black women’s lives, activism, and the development of Black female identity.

A Brief History of Men’s Movements in the U.S.