Essential but undervalued: Millions of health care workers aren’t getting the pay or respect they deserve in the COVID-19 pandemic

Subscribe to the brookings metro update, molly kinder molly kinder fellow - brookings metro @mollykinder.

May 28, 2020

- 20 min read

This is the second post in a series on COVID-19 frontline workers. Read the stories of the workers profiled here .

Introduction

Underpaid, undervalued, and essential.

- A policy agenda for essential, low-wage health workers:

Keep all health workers safe

Introduce hazard pay, raise pay to a permanent living wage, expand paid leave, give workers the respect they deserve.

The COVID-19 pandemic has inspired an outpouring of public appreciation for the country’s frontline heroes, from television ads to firefighter salutes to essential worker toys . But while doctors and nurses deserve our praise, they are not the only ones risking their lives during the pandemic—in fact, they represent less than 20% of all essential health workers.

Too often, we overlook the heroism and dignity of millions of low-paid, undervalued, and essential health workers like Sabrina Hopps, a 46-year-old housekeeping aide in an acute nursing facility in Washington, D.C.

“If we don’t clean the rooms correctly, the pandemic will get worse,” said Hopps. She cares deeply about the patients she works with, and knows that the value of her job goes well beyond cleaning. “It’s me and the other housekeepers who sit and talk with [patients] to brighten up their day, because they can’t have family members visiting.”

Despite her contributions, she doesn’t feel recognized. “Housekeeping has never been respected,” she told me recently. “When you think about health care work, the first people you think about are the doctors and the nurses. They don’t think about housekeeping, maintenance, dietary, nursing assistants, patient care techs, and administration.”

Hopps is one of millions of low-wage essential health workers on the COVID-19 front lines. Like the higher-paid doctors and nurses they work alongside, these essential workers are risking their lives during the pandemic—but with far less prestige and recognition, very low pay, and less access to the protective equipment that could save their lives. They are nursing assistants, phlebotomists, home health aides, housekeepers, medical assistants, cooks, and more. The vast majority of these workers are women, and they are disproportionately people of color. Median pay is just $13.48 an hour.

Over the last several weeks, I interviewed nearly a dozen low-wage health workers on the front lines of COVID-19. ( You can read their stories here . ) Despite being declared “essential,” the workers I interviewed described feeling overlooked and deprioritized, even expendable. They spoke with pride about their work, but few felt respected, even as they put their lives on the line. Many expressed frustration—and sometimes anger—over their lack of life-saving protective equipment.

It is long past time that these workers are treated as truly essential. This starts with simply recognizing the value of workers like Hopps—but we can and must do more. The policy recommendations in this report aim to keep these workers safe on the job, compensate them with a living wage, support them if they fall ill, and give them the respect and appreciation they deserve.

Back to top ⇑

The underpaid but essential health care workforce in America comprises nearly 7 million people in low-paid health jobs in these three categories:

- Health care support workers assist health care providers such as doctors and nurses in providing patient care. Roles include orderlies, medical assistants, phlebotomists, and pharmacy aides.

- Direct care workers such as home health workers, nursing assistants, and personal care aides provide care to individuals with physical, cognitive, or other needs.

- Health care service workers include housekeepers, janitors, and food preparation and serving workers employed in health care settings such as hospitals and nursing homes.

More people are employed in health care support, service, and direct care jobs than in all health care practitioner and technician jobs (doctors, nurses, EMTs, lab technicians, etc.). In fact, more people work in hospitals as housekeepers and janitors—like Sabrina Hopps—than as physicians and surgeons. The size of this low-wage health workforce exceeds the size of most other occupational groups of essential workers. It employs more people than the entire transportation and warehousing industry and more than twice as many people as the grocery industry .

Median wages in health care support, service, and direct care jobs were just $13.48 an hour in 2019—well short of a living wage and far lower than the median pay of doctors (over $100 per hour) and nurses ($35.17 per hour). Home health and personal care workers earn even less, with a median hourly wage of only $11.57. The wages are so low that nearly 20% of care workers live in poverty and more than 40% rely on some form of public assistance. These fields are some of the fastest-growing of all occupations, with more than a million new jobs projected by 2028.

Table 1. Demographic profile of workers in the health care and social assistance industry, 2019

Source: Brookings analysis of U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Occupational Employment Statistics and the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey.

Over 80% of health care support, service, and direct care workers are women. They are also disproportionately people of color. Like other low-wage jobs where women and people of color are concentrated , many of these positions are plagued by underinvestment and a lack of benefits. Now, these jobs pose an even greater risk to workers’ lives.

Despite being undervalued, low-wage health workers make essential contributions during the pandemic and beyond. “Nobody is insignificant,” said Tony Powell, a 62-year-old administrative coordinator of a hospital surgical unit in Washington, D.C. “Without environmental service, without dietary, without secretaries, without medical and surgical techs and certified nursing assistants (CNAs), it wouldn’t be a hospital.” Home health workers, for instance, provide the first line of defense against COVID-19 for millions of elderly and vulnerable people living at home. Without that, the limited capacity of hospitals today would be stretched even further.

A policy agenda for essential, low-wage health workers

Policymakers, employers, and the general public should each do their part for low-wage essential health workers during COVID-19 and beyond. The following policy recommendations are aimed at keeping these workers safe on the job, compensating them with a living wage, supporting them if they fall ill, and giving them the respect and appreciation they deserve.

A first-order priority for policymakers and employers should be keeping frontline health workers safe on the job. Dire shortages of life-saving personal protective equipment (PPE) such as surgical masks, N95 respirators, isolation gowns, gloves, and face shields are jeopardizing workers’ lives. One poll showed that two-thirds of health care workers reported insufficient face masks as recently as early May. Frustrated nurses and doctors have made urgent appeals to the federal government to activate the Defense Production Act to mobilize production of needed supplies.

While most news coverage highlights only the risks to nurses and doctors, PPE shortages are also a matter of life and death for millions of health care support, service, and direct care workers on the COVID-19 front line. These workers are at a lower priority for the already-insufficient supplies, meaning that hospitals and health care facilities sometimes overlook their safety as they ration PPE and prioritize vulnerable clinical staff who treat infectious patients.

The workers I interviewed expressed a range of emotions—from fear to frustration to anger—over their lack of access to PPE. David Saucedo, a 52-year-old cook at a Baltimore nursing home, said his supervisors initially denied his requests for PPE.

“Just because I am not a nurse or nursing assistant doesn’t mean I don’t come in contact with patients,” Saucedo told me. “Every footstep a nurse, nursing assistant, or doctor takes in that facility, I actually walk right behind them.” His Alzheimer’s patients, he noted, do not understand social distancing: “They just come up to you, grab you, and sit and talk to you.”

Saucedo had to argue his case to two supervisors before he was finally given the PPE that nurses in his facilities automatically access. “It’s like they prioritized them and forgot about everyone else,” he told me. “It makes me feel like I am secondary, not equal. You are expendable, in a way.”

Andrea (who preferred we only use her first name), a 29-year-old housekeeping aide in a hospital operating room and mother of two young children, had a similar experience. After a patient in a room she was responsible for cleaning was suspected of having the coronavirus, Andrea asked her charge nurse to be fit-tested for an N95 mask. Andrea said the nurse’s response was, “No, these are for special people.”

“One minute you are important enough,” she told me. “The next minute it is like, no you aren’t that important to get the proper equipment, but you are important enough to clean it for the next patient.”

Home care workers face additional hurdles to accessing PPE. Their employers are much lower in priority for state and federal PPE supplies than hospitals, nursing homes, and emergency services, leaving many agencies struggling to procure equipment on their own and pay for its skyrocketing costs on the private market. A recent survey found more than 75% of home care agencies face shortages of masks and sanitizer.

Like others in her field, Elizabeth Peachy, a 49-year-old home health aide in Virginia, received no PPE, COVID-19 training, or supplies from her employer. She described driving to towns across Virginia and West Virginia in search of her own equipment. Yvette Beatty, a 60-year-old home health aide in Philadelphia, said her employer was unable to access PPE despite concerted efforts.

“I would love to see us have hazard masks, instead of putting cloths over our face, or going to the Dollar Store and buying dollar masks,” Beatty told me. “We need equipment. They need to give equipment to agencies. We are running around with cloths, no protective gear. We need the exact same thing as everyone else.”

» Policy recommendations to keep workers safe:

- The federal government should fully utilize the Defense Production Act to mobilize manufacturers across the country to increase the supply of PPE. Until every health care worker has sufficient access to PPE, their lives are at risk.

- State governments should encourage companies to increase PPE supplies and help home health agencies access supplies and finance costs. They can follow the lead of Washington state, which recently added home health workers and other long-term care providers to the top tier of priority for PPE.

- Home care agencies should increase training, information, and resources to frontline workers, so home care workers do not feel like they are navigating a pandemic on their own.

The extremely low pay that health care support, service, and direct care workers earn has long been woefully inadequate. During a pandemic, it is morally reprehensible. Congress should enact hazard pay to ensure that no worker risking his or her life during this crisis is paid less than a family-sustaining wage.

For workers in health jobs, federal funding for hazard pay is especially important. Hospital finances have been hit hard by the pandemic. Home care agencies are limited in their ability to raise pay due to Medicaid reimbursement rates, a major systemic impediment to improving job quality for millions of care workers. Hazard pay for health workers has lagged behind temporary pay increases for workers in sectors such as retail and grocery.

Lawmakers on both sides of the aisle have offered proposals for federally funded hazard pay. In April, President Donald Trump signaled his support for extra compensation to doctors, nurses, and health workers. On May 15, the House of Representatives passed the HEROES Act, which included $200 billion for hazard pay for essential workers. Despite this momentum, U.S. lawmakers have not passed hazard pay into law. In Canada, however, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced a $4 billion commitment to increase pay for essential workers. He singled out low-paid essential workers as a priority, saying that minimum-wage workers risking their health during the pandemic deserve a raise.

The workers I interviewed expressed a strong desire for hazard pay. David Saucedo likened the hazards of his job as a nursing home cook to the risks he faced during his military service: “When I was in the Navy, when we went to war, I was getting paid hazardous duty pay. To me, it is a hazardous job right now. We should be getting paid hazardous pay.” Saucedo noted that additional compensation could be life-saving, affording his colleagues the chance to take a taxi instead of risking exposure to COVID-19 on public transit. “Everybody is contagious on buses,” he said. “The best thing you can do is limit their amount of exposure for a cook or anyone else.”

Housekeeping aide Sabrina Hopps agreed that additional compensation could be life-saving. “If pay was better, I would be able to live on my own and so could my children,” she told me. “What I make, it is not enough. So, I am forced to share an apartment with my son and daughter and my granddaughter. Going back and forth to work, I am jeopardizing their lives.” Hopps is especially concerned for her son, who has asthma and is a cancer survivor. Her employer recently introduced a new bonus for employees providing direct patient care, but excluded housekeepers and other low-paid service workers from the additional compensation.

» Policy recommendations for introducing hazard pay:

- Congress should pass federally mandated hazard pay for at-risk essential workers in the next pandemic relief bill, with a priority for lower-paid workers. Hazard pay should double the wages of low-wage workers. In the HEROES Act legislation, House Democrats included $200 billion for hazard pay through a “Heroes Fund” that would administer grants to employers of essential workers. Their proposed rate of an additional $13 per hour is roughly equivalent to the median wage of health care support, service, and direct care workers.

COVID-19 has laid bare the wide gap between the value that health care support, service, and direct care workers bring to society and the extremely low wages they earn in return. Short-term fixes such as hazard pay are urgently needed. But policymakers and employers should also make lasting changes so that these essential workers finally earn a permanent living wage .

Hospital administrative coordinator Tony Powell explained why wage increases are so critical for low-paid health workers: “They have to realize that these people, just like any other people—doctors, nurses, whoever—they have families. They have to raise their families, too. If you are working just at the poverty level, that is giving you enough to get to work, get lunch, and try to send your kids to school. But without a living wage, it’s not going to mean anything.”

Pauline Moffitt, a 50-year-old direct care worker in Philadelphia, is barely surviving on the poverty wages she earns caring for immunocompromised and elderly residents. At $9 an hour, her pay is so low that Moffitt and her recently laid-off husband cannot make ends meet, even as she commutes nearly three hours each way on five bus and train transfers. “It is a struggle,” she told me. “I have to pay a lot of bills. What am I supposed to do? I pray always: Lord, please stretch my pay. Please .”

Pennsylvania, where Moffitt works, is one of the 21 states that has not mandated a minimum wage above the federal rate of $7.25 per hour. She wants to see permanent pay increases. “I just wish they would raise it and give us a little more,” she said. “Not just for me, but all the other home health aides that are in the same situation.”

» Policy recommendations for permanently boosting pay:

- The federal government and state and local governments should raise the minimum wage to at least $15 per hour.

- State governments and the federal government should increase Medicaid funding to allow employers of home care workers to provide a living wage and offer benefits.

While workers of all incomes are vulnerable to COVID-19, low-wage workers have the least access to paid leave if they fall ill. In 2019, less than a third of workers in the bottom 10% of income earnings had access to paid sick leave, compared to nine out of 10 higher-paid workers in the top quarter of income earnings. The gaps for essential workers like home health aides are particularly large—a 2017 survey of 3,000 home care workers found that less than one in five care workers had access to paid leave.

“We don’t get any benefits,” said Elizabeth Peachy, a 49-year-old home health aide who earns $9 an hour. The funding for her work caring for geriatric patients comes through the state of Virginia, but she is not employed directly by the state. “They have us work as independent contractors,” she told me. “And that way, we get no sick leave, no overtime, no benefits at all. This is pretty standard.”

Peachy thinks policymakers should make changes: “In reality, it is a lot cheaper to pay us a little more money, give us some benefits, and allow us to take care of those patients, keep those patients from being in an ER or a nursing home, and help them have a good quality of life in their own home.”

Low-wage health workers without paid leave are in an impossible position . They face some of the highest risks of exposure to COVID-19, but have little or no ability to stay home to care for themselves or their loved ones. The public health stakes during a pandemic are high—rushing back to their jobs before they are fully recovered jeopardizes workers’ well-being and risks spreading the coronavirus to patients and colleagues. “The problem is you are going to have some workers who are still going to go to work,” said Peachy. “And they shouldn’t, because they may be sick and they may get the person sick. It would be better to have paid sick days because we need these workers to go into homes and take care of the thousands of high-risk people.”

The Families First Coronavirus Response Act took steps to temporarily address this disparity and expand paid sick leave and family and medical leave to workers during the pandemic. However, two gaps in the legislation undermine these benefits for low-wage health workers. First, the legislation only applies to employers with less than 500 employees, which could exclude upwards of half of all workers . It also stipulates that employers may exempt “health care providers,” broadly defined by the Department of Labor to include workers across health care institutions and home care settings.

» Policy recommendations for expanding paid sick leave:

- In the next pandemic relief bill, Congress should revoke exemptions for large employers and expand access to temporary paid sick leave and family and medical leave to all workers. The HEROES Act, passed on May 15, removes the employer size exemption as well as the health care provider exemptions.

- State governments and the federal government should increase Medicaid funding to allow employers of home care workers to offer benefits such as paid leave, alongside a living wage.

Long before COVID-19, 53-year-old Yolanda Ross felt her work as a home health worker outside Richmond, Va. was not respected. She told me that low-wage health workers like her are “underpaid, overlooked and forgotten about, but yet depended upon,” while others on the front line who are deemed “important” are valued differently.

Ross’s experience is reflected in the data. Brookings’s Richard V. Reeves (who is writing about the importance of respect more generally) and Hannah Van Drie recently analyzed data on the perceived social standing of essential jobs. They found a staggering gap between the high prestige of doctors and nurses and the low prestige of lesser-paid but essential hospital workers, including housekeepers.

In interviews, these workers shared stories that bring to life the lack of respect they experience. Several wondered why low-wage essential workers are never included in TV commercials that applaud doctors and nurses. ICU worker Andrea told me her charge nurse calls her “housekeeping” and still hasn’t bothered to learn Andrea’s name despite working together for seven years. Ditanya Rosebud, a 46-year-old cook and hostess at a Baltimore nursing home said her employer responds to her sacrifices by simply telling her, “This is what you signed up for.”

Rosebud and her colleagues are working extra shifts and risking their family’s lives during the pandemic. “We are just another body,” she explained. “That’s it. No more, no less.”

Workers also shared stories of life-saving PPE being reserved for “important people,” wages that do not even cover even basic expenses, hazard pay that is given only to clinical colleagues, and a lack of appreciation for workers’ sacrifices. “People are not looking at people like us on the lower end of the spectrum,” said hospital administrative coordinator Tony Powell. “We’re not even getting respect. That is the biggest thing: We are not even getting respect.”

The COVID-19 pandemic has already upended so many aspects of society, the economy, and our lives. Yolanda Ross hopes that it will also upend our long-standing notions of who deserves to be valued. “I pray there is a redirection,” she said. “That we stop doing things the same old way and listen to those who don’t have a real voice.”

» Recommendations for giving workers respect:

- Government and other civic leaders can do more to recognize the contributions of low-wage workers and give their work public visibility. A collaboration between city leaders in New York and workforce partners around the social media effort #ValueDirectCareWorkers is an example.

- The general public can do more to include lower-wage workers in their recognition of essential workers, including actions such as meal donations to hospitals, public demonstrations of thanks and support, and social media messages.

- The media should address the imbalance in coverage of workers, and publish stories, perspectives, and images of lower-wage health workers on the COVID-19 front line.

- Employers should provide low-wage health workers with respect, appreciation, more equitable pay and support, and opportunities for training, advancement, and better job quality.

It is long past time that low-wage workers who are essential to our society are treated with dignity. Employers, colleagues, policymakers, and the general public have their parts to play in finally giving these workers the respect they have always deserved. “It can change,” Yolanda Ross reminded me. “There is hope.”

Policy recommendations overview

Click here to download a shareable version of this table.

These interviews were conducted between April 1, 2020 and April 28, 2020. Participants have provided permission to Brookings to use their names, likenesses, job titles, location and transcribed words.

We are enormously grateful to Tony Powell, Andrea, Yvette Beatty, David Saucedo, Sabrina Hopps, Elizabeth Peachy, Pauline Moffitt, Ditanya Rosebud, and Yolanda Ross for sharing their stories. We thank and each and every worker on the front lines for the sacrifices they are making.

Thanks to PHI, SEIU, SEIU Local 1199, Angelina Drake, Tatia Cooper, Yvonne Slosarski, Leslie Frane, and LaNoral Thomas for their collaboration with the worker interviews. Thanks to Richard V. Reeves, Angelina Drake, Tiffany Ford, Ai-jen Poo, Greg Larson, Alan Berube, Morgan Welch, Claudia Balog, and Vicki Shabo for substantive comments and thoughtful input.

Related Content

Molly Kinder

April 10, 2020

March 25, 2020

April 9, 2020

Brookings Metro

Simon Hodson

May 8, 2024

Alan Berube, Mark Muro

May 3, 2024

Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh PA

9:00 am - 11:15 am EDT

- Open access

- Published: 24 March 2022

Health care workers’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review

- Souaad Chemali 1 ,

- Almudena Mari-Sáez 1 ,

- Charbel El Bcheraoui 2 &

- Heide Weishaar ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1150-0265 2

Human Resources for Health volume 20 , Article number: 27 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

24k Accesses

83 Citations

11 Altmetric

Metrics details

COVID-19 has challenged health systems worldwide, especially the health workforce, a pillar crucial for health systems resilience. Therefore, strengthening health system resilience can be informed by analyzing health care workers’ (HCWs) experiences and needs during pandemics. This review synthesizes qualitative studies published during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic to identify factors affecting HCWs’ experiences and their support needs during the pandemic. This review was conducted using the Joanna Briggs Institute methodology for scoping reviews. A systematic search on PubMed was applied using controlled vocabularies. Only original studies presenting primary qualitative data were included.

161 papers that were published from the beginning of COVID-19 pandemic up until 28th March 2021 were included in the review. Findings were presented using the socio-ecological model as an analytical framework. At the individual level, the impact of the pandemic manifested on HCWs’ well-being, daily routine, professional and personal identity. At the interpersonal level, HCWs’ personal and professional relationships were identified as crucial. At the institutional level, decision-making processes, organizational aspects and availability of support emerged as important factors affecting HCWs’ experiences. At community level, community morale, norms, and public knowledge were of importance. Finally, at policy level, governmental support and response measures shaped HCWs’ experiences. The review identified a lack of studies which investigate other HCWs than doctors and nurses, HCWs in non-hospital settings, and HCWs in low- and lower middle income countries.

This review shows that the COVID-19 pandemic has challenged HCWs, with multiple contextual factors impacting their experiences and needs. To better understand HCWs’ experiences, comparative investigations are needed which analyze differences across as well as within countries, including differences at institutional, community, interpersonal and individual levels. Similarly, interventions aimed at supporting HCWs prior to, during and after pandemics need to consider HCWs’ circumstances.

Conclusions

Following a context-sensitive approach to empowering HCWs that accounts for the multitude of aspects which influence their experiences could contribute to building a sustainable health workforce and strengthening health systems for future pandemics.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has put health systems worldwide under pressure and tested their resilience. The World Health Organization (WHO) acknowledges health workforce as one of the six building blocks of health systems [ 1 ]. Health care workers (HCWs) are key to a health system’s ability to respond to external shocks such as outbreaks and as first responders are often the hardest hit by these shocks [ 2 ]. Therefore, interventions supporting HCWs are key to strengthening health systems resilience (ibid). To develop effective interventions to support this group, a detailed understanding of how pandemics affect HCWs is needed.

Several recent reviews [ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 ] focus on HCWs’ experiences during COVID-19 and the impact of the pandemic on HCWs’ well-being, including their mental health [ 3 , 7 , 8 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 ]. Most of these reviews refer to psychological scales measurements to provide quantifiable information on HCWs’ well-being and mental health [ 8 , 13 , 14 , 19 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 28 ]. While useful in assessing the scale of the problem, such quantitative measures are insufficient in capturing the breadth of HCWs’ experiences and the factors that impact such experiences. The added value of qualitative studies is in understanding the complex experiences of HCWs during COVID-19 and the contextual factors that influence them [ 29 ].

This paper reviews qualitative studies published during the first year of the pandemic to investigate what is known about HCWs’ experiences during COVID-19 and the factors and support needs associated with those experiences. By presenting HCWs’ perspectives on the pandemic, the scoping review provides the much-needed evidence base for interventions that can help strengthen HCWs and alleviate the pressures they experience during pandemics.

The review follows the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) process and guideline on conducting scoping reviews [ 30 ]. JBI updated guidelines identify scoping reviews as the most suitable choice to explore the breadth of literature on a topic, by mapping and summarizing available evidence [ 30 ]. Scoping reviews are also suitable to address knowledge gaps and provide insightful input for decision-making [ 30 ]. The review also applies the PRISMA checklist guidance on reporting literature reviews [ 31 ].

Information sources

A systematic search was conducted on PubMed database between the 9th and 28th of March 2021.

Search strategy

Drawing on Shaw et al. [ 32 ] and WHO [ 33 ], the search strategy used a controlled vocabulary of index terms including Medical Subject Headings (Mesh) of the keywords and synonyms “COVID-19”, “HCWs”, and “qualitative”. Keywords were combined using the Boolean operator “AND” (see Additional file 1 ).

Eligibility criteria

The population of interest included all types of HCWs, independent of geography and settings. Only original studies were included in the review. Papers further had to (1) report primary qualitative data, (2) report on HCWs’ experiences and perceptions during COVID-19, and (3) be available as full texts in English, German, French, Spanish or Arabic, i.e., in a language that could be reviewed by one or several of the authors. Studies focusing solely on HCWs’ assessment of newly introduced modes of telemedicine during COVID-19 were excluded from the review as their clear emphasis on coping with technical challenges deviated from the review’s focus on HCWs’ personal and professional experiences during the pandemic.

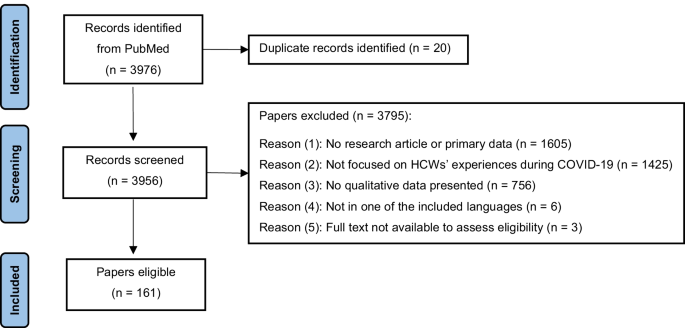

Selection process

The initial search yielded 3976 papers. All papers were screened and assessed against the eligibility criteria by one researcher (SC) to identify relevant studies. A random 25% sample of all papers was additionally screened by a second researcher (HW). Any uncertainty or inconsistency regarding inclusion were resolved by discussing the respective articles ( n = 76) among the authors.

Data collection process

Based on the research question, an initial data extraction form was developed, independently piloted on ten papers by SC and HW and finalised to include information on: (1) author(s), (2) year of publication, (3) type of HCW, (5) study design, (6) sample size, (7) topic of investigation, (8) data collection tool(s), (9) analytical approach, (10) period of data collection, (11) country, (12) income level according to World Bank [ 34 ], (13) context, and (14) main findings related to experiences, factors and support needs. Using the final extraction form, all articles were extracted by SC, with the exception of four German articles (which were extracted by HW), one Spanish and one French article (which were extracted by AMS). As far as applicable, the quality of the included articles was appraised using the JBI critical appraisal tool for qualitative research [ 35 ].

Synthesis methods

The socio-ecological model originally developed by Brofenbrenner was adapted as a framework to analyze and present the findings [ 36 , 37 , 38 ]. The model aims to understand the interconnectedness and dynamics between personal and contextual factors in shaping human development and experiences [ 36 , 38 ]. The model was chosen, because it accounts for the multifaceted interactions between individuals and their environment and is thus suited to capture the different dimensions of HCWs’ experiences, the factors associated with those experiences as well as the sources of support identified. The five socio-ecological levels (individual, interpersonal, institutional, community and policy) of the model served as a framework for analysis and were used to categorise the main themes that were identified in the scoping review as relevant to HCWs’ experiences. The process of identifying the sub-themes was conducted by SC using an excel extraction sheet, in which the main findings were captured and mapped against the socio-ecological framework.

Study selection

The selection process and the number of papers found, screened and included are illustrated in a PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1 ). A total of 161 papers were included in the review (see Additional file 2 ). Table 1 lists the included studies based on study characteristics, including type of HCW, healthcare setting, income level of countries studied and data collection tools.

PRISMA flow diagram

Study characteristics

Included papers investigated various types of HCWs. The most investigated type were nurses, followed by doctors/physicians. Medical and nursing students were also studied frequently, while only a small number of studies focused on other professions, e.g., community health workers, therapists and managerial staff. A third of all studies studied multiple HCWs, rather than targeting single professions. The majority of papers investigated so-called “frontline staff”, i.e., HCWs who engaged directly with patients who were suspected or confirmed to be infected with COVID-19. Fewer studies focused on non-frontline staff, and some explored both frontline and non-frontline staff.

Around two-thirds of all papers studied HCWs’ experiences in high-income countries, notably the USA, followed by the UK. Many papers also focused on HCWs in upper-middle income countries, with almost half of them conducted in China. Few papers investigated HCWs in lower-middle income countries, including India, Zimbabwe, Pakistan, Nigeria, and Senegal. Finally, one paper focused on HCWs in Ethiopia, a low-income country. A couple of studies presented data from multiple countries of different income levels, and one study investigating HCWs in Palestine could not be categorised. Overall, the USA was the most studied and China the second most studied geographical location (see Additional file 3 ). Hospitals were by far the most investigated healthcare settings, whereas outpatient settings, including primary care, pharmacies, homes care, nursing homes, healthcare facilities in prisons and schools as well as clinics, were investigated to a considerably lesser extent. Several studies covered more than one setting.

All studies applied a cross-sectional study design, with 54% published in 2020, and the remainder in 2021. A range of qualitative data collection methods were applied, with interviews being by far the most prominent one, followed by open-ended questionnaires. Focus groups and a few other methods including social media, online platforms or recording systems submissions, observations and open reflections were used with rare frequencies. The sample size in studies using interviews ranged between 6 and 450 interviewees. The sample size in studies using Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) ranged between 7 and 40 participants. Further information on the composition and context of the FGDs can be found in additional file 4 . Several studies used multiple data collection tools. The majority of studies applied common analysis methods, including thematic and content analysis, with few using other specific approaches.

Results of syntheses

An overview of the findings based on the socio-ecological framework is summarised in Table 2 , which lists the main sub-themes identified under each socio-ecological level.

Individual level

At the individual level, HCWs’ experiences related to their well-being, professional and personal identity as well as daily work–life routine. In terms of well-being, HCWs reported negative impacts on their physical health (e.g., tiredness, discomfort, skin damage, sleep disorders) [ 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 ] and compromised mental health. The reported negative impact on mental health included increased levels of self-reported stress, depression, anxiety, fear, grief, guilt, anger, isolation, uncertainty and helplessness [ 39 , 41 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 , 81 , 82 , 83 , 84 , 85 , 86 , 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 , 93 , 94 , 95 , 96 , 97 , 98 , 99 , 100 , 101 , 102 , 103 , 104 , 105 , 106 , 107 , 108 , 109 , 110 , 111 , 112 , 113 , 114 , 115 , 116 , 117 , 118 , 119 , 120 , 121 , 122 , 123 ]. The reported reasons for HCWs’ reduced well-being included work-related factors, such as having to adhere to new requirements in the workplace, the lack and/or burden of using Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) [ 41 , 44 , 52 , 63 , 64 , 78 , 93 , 124 , 125 ], increased workload, lack of specialised knowledge and experience, concerns over delivering low quality of care [ 42 , 44 , 49 , 52 , 53 , 63 , 69 , 70 , 73 , 74 , 76 , 78 , 79 , 83 , 84 , 85 , 86 , 89 , 90 , 93 , 94 , 101 , 103 , 109 , 125 , 126 , 127 , 128 , 129 , 130 , 131 , 132 , 133 , 134 , 135 , 136 , 137 , 138 , 139 , 140 ] and being confronted with ethical dilemmas [ 43 , 72 , 76 , 78 , 136 , 141 , 142 , 143 , 144 , 145 ]. HCWs’ compromised psychological well-being was also triggered by extensive exposure to concerning information via the media and by the pressure that was experienced due to society and the media assigning HCWs hero status [ 53 , 72 , 81 , 92 , 97 , 107 , 139 , 146 ]. Factors that were reported by HCWs as helping them cope with pressure comprised diverse self-care practices and personal activities, including but not limited to psychological techniques and lifestyle adjustments [ 47 , 56 , 64 , 71 , 72 , 78 , 90 , 139 , 147 , 148 ] as well as religious practices [ 81 , 112 , 149 ].

Self-reported well-being differed across occupations, roles in the pandemic response and work settings. One study reported that HCWs working in respiratory, infection and emergency departments expressed more worries compared to HCWs who worked in other hospital wards [ 64 ]. Similarly, frontline HCWs seemed more likely to experience feelings of helplessness and guilt as they witnessed the worsening situation of COVID-19 patients, whereas non-frontline HCWs seemed to experience feelings of guilt due to not supporting their frontline colleagues [ 98 ]. HCWs with managerial responsibility reported heightened concern for their staff’s health [ 75 , 110 , 150 ]. HCWs working in nursing homes and home care reported feelings of being abandoned and not sufficiently recognised [ 75 , 123 , 144 ], while one study investigating HCWs responding to the pandemic in a slums-setting reported fear of violence [ 56 ].

HCWs reported that the pandemic impacted both positively and negatively on their professional and personal identity. While negative emotions were more dominant at the beginning of the pandemic, positive effects were reported to gradually develop after the initial pandemic phase and included an increased sense of motivation, purpose, meaningfulness, pride, resilience, problem-solving attitude, as well as professional and personal growth [ 43 , 44 , 47 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 63 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 71 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 78 , 79 , 87 , 90 , 91 , 92 , 93 , 98 , 102 , 104 , 112 , 114 , 117 , 118 , 119 , 122 , 124 , 131 , 132 , 143 , 150 , 151 , 152 , 153 , 154 , 155 , 156 , 157 , 158 , 159 , 160 , 161 ]. Frontline staff reported particularly strong positive effects related to feelings of making a difference [ 69 , 92 ]. On the other hand, some HCWs reported doubts with regard to their career choices and job dissatisfaction [ 40 , 46 , 59 , 130 ]. Junior staff, assistant doctors and students often reported feelings of exclusion and concerns about the negative effects of the pandemic on their training [ 40 , 162 , 163 ]. Challenges with regard to their professional identity and a sense of failing their colleagues on the frontline were particularly reported by HCWs who had acquired COVID-19 themselves and experienced long COVID-19 [ 121 , 160 , 164 ]. HCWs who reached out to well-being support services expressed concern at being stigmatised [ 97 ].

HCWs reported a work–life imbalance [ 57 , 97 ] as they had to adapt to the disruption of their usual work routine [ 59 , 62 , 131 ]. This disruption manifested in taking on different roles and responsibilities [ 39 , 49 , 67 , 73 , 83 , 89 , 94 , 97 , 110 , 137 , 139 , 144 , 151 ], increased or decreased workload pressure [ 85 , 128 , 130 , 133 ] and sometimes redeployment [ 57 , 155 , 165 ]. HCWs also reported negative financial effects [ 59 , 86 , 166 ].

Interpersonal level

The findings presented in this section relate to HCWs’ perceptions of their relationships in the private and professional environment during the pandemic and to the impact these relationships had on them. With regard to the home environment, HCWs’ concerns over being infected with COVID-19 and transmitting the virus to family members were identified in almost all studies [ 41 , 44 , 48 , 51 , 54 , 56 , 61 , 68 , 75 , 77 , 80 , 85 , 90 , 128 , 139 , 160 , 167 , 168 , 169 , 170 , 171 ]. HCWs living with children or elderly family members were particularly concerned [ 47 , 65 , 95 , 97 , 163 , 172 ]. In some cases, HCWs reported that they had introduced changes to their living situation to protect their loved ones, with some deciding to move out to ensure physical distance and minimise the risk of transmission [ 39 , 43 , 44 , 89 , 105 , 161 ]. Some HCWs reported sharing limited details about their COVID-19-related duties to decrease the anxiety and fear of their significant others [ 81 ]. While in several studies, interpersonal relationships were reported to cause concerns and worries, some study also identified interpersonal relationships and the subsequent emotional connectedness as a helpful resource [ 47 , 173 , 174 ] that could, for example, alleviate anxiety [ 64 ] or provide encouragement for working on the frontline [ 49 , 106 ]. However, interpersonal relationships did not always have a supportive function, with some HCWs reporting being shunned by family and friends [ 66 , 111 , 175 ].

With regard to the work environment, relationships with colleagues were mainly described as supportive and empowering, with various studies reporting the value of teamwork during the pandemic [ 47 , 51 , 52 , 67 , 71 , 77 , 83 , 91 , 97 , 98 , 108 , 134 , 148 , 151 , 161 ]. Challenges with regard to collegial relationships included social distancing (which hindered HCWs’ interaction in the work place) [ 176 ] and working with colleagues one had never worked with before (causing a lack of familiarity with the work environment and difficulties to adapt) [ 79 ]. HCWs who worked in prisons reported interpersonal conflicts due to perceived increased authoritarian behaviour by security personnel that was perceived to manifest in arrogance and non-compliance with hygiene practices [ 88 ].

In terms of HCWs’ relationships with patients, many studies reported challenges in communicating with patients [ 50 , 55 , 126 , 132 , 133 , 172 ]. This was attributed to the use of PPE during medical examinations and care and the reduction of face-to-face visits or a complete switch to telehealth [ 128 , 139 ]. The changes in the relationships with patients varied according to the nature of work. Frontline HCWs, for example, reported challenges in caring for isolated patients [ 41 , 43 , 52 , 148 ], whereas HCWs working in specific settings and occupational roles that required specific interpersonal skills faced other challenges. This was, for example, the case for HCWs working with people with intellectual disabilities, who found it challenging to explain COVID-19 measures to this group and also had to mitigate physical contact that was considered a significant part of their work [ 71 ]. For palliative care staff, the use of PPE and measures of social distancing were challenging to apply with regard to patients and family members [ 177 ]. Building relationships and providing appropriate emotional support was reported to be particularly challenging for mental health and palliative care professionals supporting vulnerable adults or children [ 117 ]. Challenges for health and social care professionals were associated with virtual consultations and more difficult conversations [ 117 ]. Physicians reported particular frustration with remote monitoring of chronic diseases when caring for low-income, rural, and/or elderly patients [ 169 ]. Having to adjust, and compromise on, the relationships with patients caused concerns about the quality of care, which in turn, was reported to impact negatively on HCWs’ professional identity and emotional well-being.

Institutional level

This section presents HCWs’ perceptions of decision-making processes in the work setting, organizational factors and availability of institutional support.

With regard to decision-making, a small number of studies reported HCWs’ trust in the institutions they worked in [ 143 , 172 ], while the majority of studies revealed discontent about institutional leadership and feelings of exclusion from decision-making processes [ 65 , 178 ]. More specifically, HCWs reported a lack of clear communication and coordination [ 41 , 70 , 144 , 148 , 179 ] and a wish to be provided with the rationales behind management decisions and to be included in recovery phase planning [ 48 ]. They perceived centralised decision-making processes as unfamiliar and restrictive [ 150 ]. Instead, HCWs endorsed de-centralised and participatory approaches to communication and decision-making [ 56 ]. Emergency and critical care physicians suggested to include bioethicists as part of the decision-making on triaging scarce critical resources [ 126 ]. Studies of both hospital and primary care settings reported perceived disconnectedness and poor collaboration between managerial, administrative and clinical staff, which was a contributing factor to burnout among HCWs [ 60 , 83 , 149 , 169 , 180 , 181 , 182 ]. Dissatisfaction with communication also related to constantly changing protocols, which were perceived as highly burdening and frustrating, creating ambiguity and negatively affecting HCWs’ work performance [ 44 , 55 , 59 , 78 , 112 , 183 ].

In terms of organizational factors, many HCWs reported a perceived lack of organizational preparedness and poor organization of care [ 60 , 65 , 120 , 179 ]. Changes in the organization of care were perceived as chaotic, especially at the beginning of the pandemic, and changes in roles and responsibilities and role allocation were perceived as unfair and unsatisfying [ 72 , 97 ]. Only in one study, changes in work organisation were perceived positively, with nurses reporting satisfaction with an improved nurse–patient ratio resulting from organisational changes [ 52 ]. Overall, frontline HCWs advocated for more stability in team structure to ensure familiarity and consistency at work [ 47 , 66 , 72 , 114 , 116 ]. HCWs appreciated multidisciplinary teams, despite challenges with regard to achieving rapid and efficient collaboration between members from different departments [ 41 , 143 , 152 ].

Regarding institutional support, in some instances, psychological, managerial, material and technical support was positively acknowledged, while the majority of studies reported HCWs’ dissatisfaction with the support provided by the institution they worked in [ 46 , 48 , 73 , 84 , 92 , 97 , 114 , 139 , 144 , 174 , 184 ]. Across studies, a lack of equipment, including the unavailability of suitable PPEs, was one of the most prominent critiques, especially in the initial phase the pandemic [ 41 , 46 , 54 , 55 , 61 , 69 , 70 , 72 , 73 , 81 , 84 , 85 , 96 , 97 , 111 , 118 , 144 , 147 , 168 ]. In one study of a rural nursing home, HCWs reported being illegally required to treat COVID-19 patients without adequate PPE [ 39 ]. Specialised physicians, such as radiologists, for example, reported that PPE were prioritised for COVID-19 ward workers [ 65 ]. In another instance, HCWs reported that they had taken care of their own mask supply [ 113 ]. Insufficient equipment and the subsequent lack of protection induced fear and anxiety regarding one’s personal safety [ 64 , 87 ]. HCWs also reported inadequate human resources, which had consequences on increased workload [ 44 , 46 , 54 , 69 , 75 , 85 ]. Dissatisfaction with limited infrastructure was reported overall and across settings, but specific limitations were particularly relevant in certain contexts [ 116 ]. HCWs in low resource settings, including Pakistan, Zimbabwe and India, reported worsening conditions regarding infrastructure, characterised by a lack of water supply and ventilation, poor conditions of isolation wards and lack of quality rest areas for staff [ 41 , 58 , 84 ]. Despite adaptive interventions aimed at shifting service delivery to outdoors, procedures such as patient registration and laboratory work took place in poorly ventilated rooms [ 56 ]. Technical support such as the accessibility to specialised knowledge and availability of training were identified by HCWs as an important resource that required strengthening. They advocated for better “tailor-made” trainings in emergency preparedness and response, crisis management, PPE use and infection control [ 41 , 52 , 61 , 68 , 73 , 127 , 144 ]. HCWs argued that the availability of such training would improve their sense of control in health emergencies, while a lack of training compromised their confidence in their ability to provide quality healthcare [ 47 , 134 ].

Structural factors such as power hierarchies and inequalities played a role in HCWs’ perceived sense of institutional support amidst the quick changes in their institutions. Such factors were particularly mentioned in studies investigating nurses who reported dissatisfaction over doctors’ dominance and discrimination in obtaining PPE [ 54 ] as well as unfairness in work allocation [ 72 , 184 ]. They also perceived ambiguity in roles and responsibilities between nurses and doctors [ 101 ]. A low sense of institutional support was also reported by other HCWs. Junior medical staff and administrative staff reported feeling exposed to unacceptable risks of infection and a lack of recognition by their institution [ 139 ]. Staff in non‐clinical roles, non-frontline staff, staff working from home, acute physicians and those on short time contracts felt less supported and less recognised compared to colleagues on the frontline [ 48 , 139 ].

Community level

This level entails how morale and norms, as well as public knowledge relate to HCWs’ experiences in the pandemic. On the positive side, societal morale and norms were perceived as enhancing supportive attitudes among the public toward HCWs and triggering community initiatives that supported HCWs in both emotional and material ways [ 47 , 78 , 92 , 108 , 140 , 147 ]. This supportive element was especially experienced by frontline HCWs, who felt valued, appreciated and empowered by their communities. HCWs’ reaction to the hero status that was assigned to them was ambivalent [ 146 , 185 ]. In response to this status attribution, HCWs reported a sense of pressure to be on the frontline and to work beyond their regular work schedule [ 51 ]. With community support being perceived as clearly focusing on hospital frontline staff, HCWs working from home, in nursing homes, home care and non-frontline facilities and wards perceived less public support [ 139 ] and appreciation [ 85 , 144 ]. One study highlighted that HCWs did not benefit from this form of public praise but preferred an appreciation in the form of tangible and financial resources instead [ 160 ].

A clear negative aspect of social norms manifested in the stigmatisation and negative judgment by community members [ 72 , 100 , 106 , 186 , 187 ], who avoided contact with HCWs based on the perceptions that they were virus carriers and spreaders [ 43 , 68 , 92 , 111 ]. Such discrimination had negative consequences with regard to HCWs’ personal lives, including lack of access to public transportation, supermarkets, childcare and other public services [ 65 , 80 , 107 ]. Chinese HCWs working abroad reported bullying due to others perceiving and labeling COVID-19 as the ‘Chinese virus’ [ 77 ]. Negative judgment was mainly reported in studies on nurses . In a study of a COVID-19-designated hospital, frontline nurses reported unusually strict social standards directed solely at them [ 122 ]. In a comparative study of nursing homes in four countries, geriatric nurses reported social stigma toward their profession, which the society perceive not worth of respect [ 75 ].

Beyond social norms, studies identified the level of public awareness, knowledge and compliance as important determinants of HCWs’ experiences and emotional well-being [ 147 ]. For example, a lack of compliance with social distancing and other preventive measures was reported to induce feelings of betrayal, anger and anxiety among HCWs [ 41 , 80 , 81 , 111 , 188 ]. The dissemination of false information and rumors and their negative influence on knowledge and compliance was also reported with anger by HCWs in general [ 58 ], an in particular by those who worked closely with local communities [ 129 ]. Online resources and voluntary groups facilitated information exchange and knowledge transfer, factors which were valued by HCWs as an important source of information and support [ 131 , 189 ].

Policy level

Findings presented here include HCWs’ perceptions of governmental responses, governmental support and the impact of governmental measures on their professional and private situation. In a small number of studies, HCWs expressed confidence in their government’s ability to respond to the pandemic and satisfaction with governmental compensation [ 45 , 47 ]. In most cases, however, HCWs expressed dissatisfactions with the governmental response, particularly with the lack of health system organisation, the lack of a coordinated, unified response and the failure to follow an evidence-based approach to policy making. HCWs also perceived governmental guidelines as chaotic, confusing and even contradicting [ 61 , 85 , 86 , 115 , 117 , 118 , 120 , 123 , 147 , 160 , 182 , 190 ]. In one study, inadequate staffing was directly attributed to inadequate governmental funding decisions [ 191 ]. Many studies reported that HCWs had a sense of being failed by their governments [ 60 , 100 , 191 ], with non-frontline staff, notably HCWs working with the disabled [ 71 , 181 ], the elderly [ 39 , 75 , 123 , 151 ] or in home-based care [ 58 ], being particularly likely to voice feelings of being forgotten, deprioritised, invisible, less recognised and less valued by their governments. Care home staff perceived governmental support to be unequally distributed across health facilities and as being focused solely on public institutions, which prevented them from receiving state benefits [ 149 ].

Measures and regulations imposed at the governmental level had a considerable impact on HCWs’ professional as well as personal experiences. In nursing homes, HCWs perceived governmental regulations such as visiting restrictions as particularly challenging and complained that rules had not been designed or implemented with consideration to individual cases [ 62 ]. The imposed rules burdened them with additional administrative tasks and forced them to compromise on the quality of care, resulting in moral distress [ 62 ]. In abortion clinics, HCWs expressed concerns about their services being classed as non-essential services during the early stages of the pandemic [ 190 ]. Governmental policies also had impacts on HCWs personally. For example, the closure of childcare negatively impacted HCWs’ ability to balance personal and private roles and commitments. National lockdowns which restricted travel made it harder for HCWs to get to work or to see their families, especially in places with low political stability [ 95 ]. The de-escalation of measures, notably the opening of airports, was perceived as betrayal by HCWs who felt they bore the burden of increased COVID-19 incidences resulting from de-escalation strategies [ 111 ].

HCWs identified clear and consistent governmental crisis communication [ 97 , 126 ], better employees’ rights and salaries, and tailored pandemic preparedness and crisis management policies that considered different healthcare settings and HCWs’ needs [ 43 , 64 , 81 , 101 , 124 , 160 , 167 , 169 , 188 , 192 , 193 ] as important areas for improvement. HCWs in primary care advocated for strengthened primary health care, improved public health education [ 45 , 130 ] and a multi-sectoral approach in pandemic management [ 129 ].

Our scoping review of HCWs’ experiences, support needs and factors that influence these experiences during COVID-19 shows that HCWs were affected at individual, interpersonal, institutional, community and policy levels. It also highlights that certain experiences can have disruptive effects on HCWs’ personal and professional lives, and thus identifies problems which need to be addressed and areas that could be strengthened to support HCWs during pandemics.

To the best of our knowledge, our review is the first to provide a comprehensive account of HCWs’ experiences during COVID-19 across contexts. By applying an exploratory angle and focusing on existing qualitative studies, the review does not only provide a rich description of the situation of HCWs but also develops an in-depth analysis of the contextual multilevel factors which impact on HCWs’ experiences.

Our scoping review shows that, while studies on HCWs’ experiences in low resource settings are scarce, the few studies that exist and the comparison with other studies point towards setting-specific experiences and challenges. We thus argue that understanding HCWs’ experiences requires comparative investigations, which not only take countries’ income levels into account but also other contextual differences. For example, in our analysis, we identify particular challenges experienced by HCWs working in urban slums and places with limited infrastructure and low political stability. Similarly, in a recent short communication in Social Science & Medicine, Smith [ 194 ] presents a case study on the particular challenges of midwives in resource-poor rural Indonesia at the start of the pandemic, highlighting increased risks and intra-country health system inequalities. Contextual intra-country differences in HCWs’ experiences also manifest at institutional level. For example, the review suggests that HCWs who work in non-hospital settings, such as primary care services, nursing homes, home based care or disability services, experienced particular challenges and felt less recognized in relation to hospital-based HCWs. In a similar vein, HCWs working in care homes felt that as state support was not equally distributed, those working in public institutions had better chances to benefit from state support.

The review highlights that occupational hierarchies play a crucial role in HCWs’ work-related experiences. Our analysis suggests that existing occupational hierarchies seem to increase or be exposed during pandemics and that occupation is a structural factor in shaping HCWs’ experiences. The review thus highlights the important role that institutions and employers play in pandemics and is in line with the growing body of evidence that associates HCWs’ well-being during COVID-19 with their occupational role [ 195 ] and the availability of institutional support [ 195 , 196 ]. The findings suggest that to address institutional differences and ensure the provision of needs-based support to all groups of HCWs, non-hierarchical and participative processes of decision-making are crucial.

Another contextual factor affecting HCWs’ experiences are their communities. While the majority of HCWs experience emotional and material support from their community, some also feel pressure by the expectations they are confronted with. The most prominent example of such perceived pressure is the ambivalence that was reported with regard to the assignment of a hero status to HCWs. On the one hand, this attribution meant that HCWs felt recognized and appreciated by their communities. On the other hand, it led to HCWs feeling pressured to work without respecting their own limits and taking care of themselves.

This scoping review points towards a number of research gaps, which, if addressed, could help to hone interventions to support HCWs and improve health system performance and resilience.

First, the majority of existing qualitative studies investigate nurses’ and doctors’ experiences during COVID-19. Given that other types of HCWs play an equally important role in pandemic responses, future research on HCWs’ experiences in pandemics should aim for more diversity and help to tease out the specific challenges and needs of different types of HCWs. Investigating different types of HCWs could inform and facilitate the development of tailored solutions and provide need-based support.

Second, the majority of studies on HCWs’ experiences focus on hospital settings. This is not surprising considering that the bulk of societal and political attention during COVID-19 has been on the provision of acute, hospital-based care. The review thus highlights a gap with regard to research on HCWs in settings which might be considered less affected and neglected but which might, in fact, be severely collaterally affected during pandemics, such as primary health centers, care homes and home-based care. It also indicates that research which compares HCWs’ experiences across levels of care can help to tease out differences and identify specific challenges and needs.

Third, the review highlights the predominance of cross-sectional studies. In fact, we were unable to identify any longitudinal studies of HCWs’ experiences during COVID-19. A possible reason for the lack of longitudinal research is the relatively short time that has passed since the start of the pandemic which might have made it difficult to complete longitudinal qualitative studies. Yet, given the dynamics and extended duration of the pandemic, and knowledge about the impact of persistent stress on an individual’s health and well-being [ 197 , 198 , 199 , 200 ], longitudinal studies on HCWs’ experiences during COVID-19 would provide added value and allow an analysis across different stages of the pandemic as well as post-pandemic times. In our review, three differences in HCWs’ experiences across the phases of the pandemic were observed. The first one is on the individual level, reflecting the dominance of the negative emotions at the initial phase of the pandemic, which was gradually followed by increased reporting of the positive impact on HCWs’ personal and professional identity. The two other differences were on the institutional level, referring to the dissatisfaction over the lack of equipment and organization of care, mainly observed at the initial pandemic phase. Further comparative analysis of changes in HCWs’ experiences over the course of a pandemic is an interesting and important topic for future research, which could also map HCWs’ experiences against hospital capacities, availability of vaccines and tests as well as changes in pandemic restrictions. Such comparative analysis can inform the development of suitable policy level interventions accounting for HCWs’ experiences at different pandemic stages, from preparedness to initial response and recovery.

Finally, the majority of studies included in the review were conducted in the Northern hemisphere, revealing a gap in understanding the reality of HCWs in low- and lower middle income countries. Ensuring diversity in geographies and including resource-poor settings in research on HCWs would help gain a better contextual understanding, contribute to strengthening pandemic preparedness in settings, where the need is greatest, and facilitate knowledge transfer between the global North and South. While further research can help to increase our understanding of HCWs’ experiences during pandemics, this scoping review establishes a first basis for the evaluation and improvement of interventions aimed at supporting HCWs prior to, during and after COVID-19. A key finding of our analysis to strengthen HCWs’ resilience are the interdependencies of factors across the five levels of the socio-ecological model. For example, institutional, community or policy level factors (such as dissatisfaction with decision-making processes, public non-compliance or failures in pandemic management) can have a negative impact on HCWs at interpersonal and individual levels by impacting on their professional relationships, mental health or work performance. Similarly, policy, community or institutional level factors (such as adequate policy measures, appreciation within the community and the provision of PPE and other equipment) can act as protective factors for HCWs’ well-being. In line with the social support literature [ 201 ], interpersonal relationships were identified as a key factor in shaping HCWs’ experiences. The identification of the inter-dependencies between factors affecting HCWs during pandemics further highlights that health systems are severely impacted by factors outside the health systems’ control. Previous scholars have recognized the embeddedness of health systems within, and their constant interaction with, their socio-economic and political environment [ 202 ]. Previous literature, however, also shows that interventions tackling distress of HCWs have largely focused on individual level factors, e.g., on interventions aimed at relieving psychological symptoms, rather than on contextual factors [ 16 ]. To strengthen HCWs and empower them to deal with pandemics, the contextual factors that affect their situation during pandemics need to be acknowledged and interventions need to follow a multi-component approach, taking the multitude of aspects and circumstances into account which impact on HCWs’ experiences.

Limitations and strengths

Our scoping review comes with a number of limitations. First, due to resource constraints, the search was conducted using only one database. The authors acknowledge that running the search strategy on other search engines could have resulted in additional interesting studies to be reviewed. To mitigate any weaknesses, extensive efforts were made to build a strong search string by reviewing previous peer-reviewed publications as well as available resources from recognized public health institutions. Considering the high numbers of studies identified, it can be, however, assumed that the search strategy and review led to valid conclusions. Second, the review excluded non-original publications. While other types of publications could have provided additional data and perspectives on HCWs’ experiences, we decided to limit our review to original, peer-reviewed research articles to ensure quality. Third, the review excluded studies on other pandemics, which could have provided further insights into HCWs’ experiences during health crises. Given the limited resources available to the research project, it was decided to focus only on COVID-19 to accommodate a larger target group of all types of HCWs and a variety of geographical locations and healthcare settings. Furthermore, it can be argued that previous pandemics did not reach the magnitude of COVID-19 and did not lead to similar responses. With the review looking at the burden of COVID-19 as a stressor, it can be assumed that the more important the stressor, the more interesting the results. Therefore, the burdens and the way in which HCWs dealt with these burdens would be particularly augmented with regard to COVID-19, making it a suitable focus example to investigate HCWs’ experiences in health crises. The authors acknowledge that during other pandemics HCWs’ experiences might differ and be less pronounced, yet this review has addressed stressors and ways of supporting HCWs that could also inform future health crises. In our view, a major strength of the review is that is does not apply any limitation in terms of the types of HCWs, the geographical locations or the healthcare settings included. This approach did not only allow us to review a wide range of literature on an expanding area of knowledge [ 30 ], but to appropriately investigate HCWs’ experiences during a public health emergency of international concern that affects countries across the globe. Providing detailed information about the contexts in which HCWs were studied, allowed us to shed light on the contextual factors affecting HCWs’ experiences.

Implications for policy and practice

Areas of future interventions that improve HCWs’ resilience at individual level could aim towards alleviating stress and responding to their specific needs during pandemics, in line with encouraging self-care activities that can foster personal psychological resilience. Beyond that, accounting for the context when designing and implementing interventions is crucial. This can be done by addressing the circumstances HCWs live and work in, referred to in German-speaking countries as “Verhältnisprävention”, i.e., prevention through tackling living and working conditions. Respective interventions should tackle all levels outlined in the socio-ecological model, applying a systems approach. At the interpersonal level, creating a positive work environment in times of crises that is supportive of uninterrupted and efficient communication among HCWs and between HCWs and patients is important. In addition, interpersonal support, e.g., by family and friends could be facilitated. At institutional level, organizational change should consider transparent and participatory decision making and responsible planning of resources availability and allocation. At community level, tracing rumors and misinformation during health emergencies is crucial, as well as advocating for accountable journalism and community initiatives that support HCWs in times of crisis. At policy level, pandemic regulations need to account for their consequences on HCWs’ work situations and personal lives. Governmental policies and guidelines should build on scientific evidence and take into account the situations and lived experiences of HCWs across all levels of care.

This scoping review of existing qualitative research on HCWs’ experiences during COVID-19 sheds light on the impact of a major pandemic on the health workforce, a key pillar of health systems. By identifying key drawbacks, strengths that can be built upon, and crucial entry-points for interventions, the review can inform strategies towards strengthening HCWs and improving their experiences. Following a systems approach which takes the five socio-ecological levels into account is crucial for the development of context-sensitive strategies to support HCWs prior to, during and after pandemics. This in turn can contribute to building a sustainable health workforce and to strengthening and better preparing health systems for future pandemics.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files, except for a detailed extraction sheet for all studies included, which is available from the corresponding author upon request.

Abbreviations

- Health care workers

Joanna Briggs Institute

Focus Groups Discussions

Personal Protective Equipment

World Health Organization

World Health Organization. Strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes—WHO framework for action 2007. https://www.who.int/healthsystems/strategy/everybodys_business.pdf?ua=1 . Accessed 29 July 2020.

Hanefeld J, Mayhew S, Legido-Quigley H, Martineau F, Karanikolos M, Blanchet K. Towards an understanding of resilience: responding to health systems shocks. Health Policy Plan. 2018;33(3):355–67.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Schwartz R, Sinskey JL, Anand U, Margolis RD. Addressing postpandemic clinician mental health: a narrative review and conceptual framework. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(12):981–8.

PubMed Google Scholar

Houghton C, Meskell P, Delaney H, Smalle M, Glenton C, Booth A, et al. Barriers and facilitators to healthcare workers’ adherence with infection prevention and control (IPC) guidelines for respiratory infectious diseases: a rapid qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;4(4):CD013582.

Bhaumik S, Moola S, Tyagi J, Nambiar D, Kakoti M. Community health workers for pandemic response: a rapid evidence synthesis. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(6): e002769.

Chersich MF, Gray G, Fairlie L, Eichbaum Q, Mayhew S, Allwood B, et al. COVID-19 in Africa: care and protection for frontline healthcare workers. Glob Health. 2020;16(1):46.

Google Scholar

Giorgi G, Lecca LI, Alessio F, Finstad GL, Bondanini G, Lulli LG, et al. COVID-19-related mental health effects in the workplace: a narrative review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(21):7857.

CAS PubMed Central Google Scholar

De Brier N, Stroobants S, Vandekerckhove P, De Buck E. Factors affecting mental health of health care workers during coronavirus disease outbreaks (SARS, MERS & COVID-19): a rapid systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(12): e0244052.

Rieckert A, Schuit E, Bleijenberg N, Ten Cate D, de Lange W, de Man-van Ginkel JM, et al. How can we build and maintain the resilience of our health care professionals during COVID-19? Recommendations based on a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2021;11(1): e043718.

Kuek JTY, Ngiam LXL, Kamal NHA, Chia JL, Chan NPX, Abdurrahman A, et al. The impact of caring for dying patients in intensive care units on a physician’s personhood: a systematic scoping review. Philos Ethics Humanit Med. 2020;15(1):12.

Salazar de Pablo G, Vaquerizo-Serrano J, Catalan A, Arango C, Moreno C, Ferre F, et al. Impact of coronavirus syndromes on physical and mental health of health care workers: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2020;275:48–57.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Shreffler J, Petrey J, Huecker M. The impact of COVID-19 on healthcare worker wellness: a scoping review. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21(5):1059–66.

Sanghera J, Pattani N, Hashmi Y, Varley KF, Cheruvu MS, Bradley A, et al. The impact of SARS-CoV-2 on the mental health of healthcare workers in a hospital setting—a systematic review. J Occup Health. 2020;62(1): e12175.

Serrano-Ripoll MJ, Meneses-Echavez JF, Ricci-Cabello I, Fraile-Navarro D, Fiol-deRoque MA, Pastor-Moreno G, et al. Impact of viral epidemic outbreaks on mental health of healthcare workers: a rapid systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:347–57.

Fernandez R, Lord H, Halcomb E, Moxham L, Middleton R, Alananzeh I, et al. Implications for COVID-19: a systematic review of nurses’ experiences of working in acute care hospital settings during a respiratory pandemic. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;111: 103637.

Muller AE, Hafstad EV, Himmels JPW, Smedslund G, Flottorp S, Stensland S, et al. The mental health impact of the covid-19 pandemic on healthcare workers, and interventions to help them: a rapid systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2020;293: 113441.

Paiano M, Jaques AE, Nacamura PAB, Salci MA, Radovanovic CAT, Carreira L. Mental health of healthcare professionals in China during the new coronavirus pandemic: an integrative review. Rev Bras Enferm. 2020;73(suppl 2): e20200338.

Spoorthy MS, Pratapa SK, Mahant S. Mental health problems faced by healthcare workers due to the COVID-19 pandemic—a review. Asian J Psychiatry. 2020;51: 102119.

Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, Giannakoulis VG, Papoutsi E, Katsaounou P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:901–7.

Salari N, Khazaie H, Hosseinian-Far A, Khaledi-Paveh B, Kazeminia M, Mohammadi M, et al. The prevalence of stress, anxiety and depression within front-line healthcare workers caring for COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-regression. Hum Resour Health. 2020;18(1):100.

Cénat JM, Blais-Rochette C, Kokou-Kpolou CK, Noorishad PG, Mukunzi JN, McIntee SE, et al. Prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psychological distress among populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2021;295: 113599.

da Silva FCT, Neto MLR. Psychiatric symptomatology associated with depression, anxiety, distress, and insomnia in health professionals working in patients affected by COVID-19: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2021;104: 110057.

Luo M, Guo L, Yu M, Jiang W, Wang H. The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291: 113190.

da Silva FCT, Neto MLR. Psychological effects caused by the COVID-19 pandemic in health professionals: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Progr Neuro-psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2021;104: 110062.

Preti E, Di Mattei V, Perego G, Ferrari F, Mazzetti M, Taranto P, et al. The psychological impact of epidemic and pandemic outbreaks on healthcare workers: rapid review of the evidence. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2020;22(8):43.

Carmassi C, Foghi C, Dell’Oste V, Cordone A, Bertelloni CA, Bui E, et al. PTSD symptoms in healthcare workers facing the three coronavirus outbreaks: what can we expect after the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020;292: 113312.