How to write a literature review introduction (+ examples)

The introduction to a literature review serves as your reader’s guide through your academic work and thought process. Explore the significance of literature review introductions in review papers, academic papers, essays, theses, and dissertations. We delve into the purpose and necessity of these introductions, explore the essential components of literature review introductions, and provide step-by-step guidance on how to craft your own, along with examples.

Why you need an introduction for a literature review

When you need an introduction for a literature review, what to include in a literature review introduction, examples of literature review introductions, steps to write your own literature review introduction.

A literature review is a comprehensive examination of the international academic literature concerning a particular topic. It involves summarizing published works, theories, and concepts while also highlighting gaps and offering critical reflections.

In academic writing , the introduction for a literature review is an indispensable component. Effective academic writing requires proper paragraph structuring to guide your reader through your argumentation. This includes providing an introduction to your literature review.

It is imperative to remember that you should never start sharing your findings abruptly. Even if there isn’t a dedicated introduction section .

Instead, you should always offer some form of introduction to orient the reader and clarify what they can expect.

There are three main scenarios in which you need an introduction for a literature review:

- Academic literature review papers: When your literature review constitutes the entirety of an academic review paper, a more substantial introduction is necessary. This introduction should resemble the standard introduction found in regular academic papers.

- Literature review section in an academic paper or essay: While this section tends to be brief, it’s important to precede the detailed literature review with a few introductory sentences. This helps orient the reader before delving into the literature itself.

- Literature review chapter or section in your thesis/dissertation: Every thesis and dissertation includes a literature review component, which also requires a concise introduction to set the stage for the subsequent review.

You may also like: How to write a fantastic thesis introduction (+15 examples)

It is crucial to customize the content and depth of your literature review introduction according to the specific format of your academic work.

In practical terms, this implies, for instance, that the introduction in an academic literature review paper, especially one derived from a systematic literature review , is quite comprehensive. Particularly compared to the rather brief one or two introductory sentences that are often found at the beginning of a literature review section in a standard academic paper. The introduction to the literature review chapter in a thesis or dissertation again adheres to different standards.

Here’s a structured breakdown based on length and the necessary information:

Academic literature review paper

The introduction of an academic literature review paper, which does not rely on empirical data, often necessitates a more extensive introduction than the brief literature review introductions typically found in empirical papers. It should encompass:

- The research problem: Clearly articulate the problem or question that your literature review aims to address.

- The research gap: Highlight the existing gaps, limitations, or unresolved aspects within the current body of literature related to the research problem.

- The research relevance: Explain why the chosen research problem and its subsequent investigation through a literature review are significant and relevant in your academic field.

- The literature review method: If applicable, describe the methodology employed in your literature review, especially if it is a systematic review or follows a specific research framework.

- The main findings or insights of the literature review: Summarize the key discoveries, insights, or trends that have emerged from your comprehensive review of the literature.

- The main argument of the literature review: Conclude the introduction by outlining the primary argument or statement that your literature review will substantiate, linking it to the research problem and relevance you’ve established.

- Preview of the literature review’s structure: Offer a glimpse into the organization of the literature review paper, acting as a guide for the reader. This overview outlines the subsequent sections of the paper and provides an understanding of what to anticipate.

By addressing these elements, your introduction will provide a clear and structured overview of what readers can expect in your literature review paper.

Regular literature review section in an academic article or essay

Most academic articles or essays incorporate regular literature review sections, often placed after the introduction. These sections serve to establish a scholarly basis for the research or discussion within the paper.

In a standard 8000-word journal article, the literature review section typically spans between 750 and 1250 words. The first few sentences or the first paragraph within this section often serve as an introduction. It should encompass:

- An introduction to the topic: When delving into the academic literature on a specific topic, it’s important to provide a smooth transition that aids the reader in comprehending why certain aspects will be discussed within your literature review.

- The core argument: While literature review sections primarily synthesize the work of other scholars, they should consistently connect to your central argument. This central argument serves as the crux of your message or the key takeaway you want your readers to retain. By positioning it at the outset of the literature review section and systematically substantiating it with evidence, you not only enhance reader comprehension but also elevate overall readability. This primary argument can typically be distilled into 1-2 succinct sentences.

In some cases, you might include:

- Methodology: Details about the methodology used, but only if your literature review employed a specialized method. If your approach involved a broader overview without a systematic methodology, you can omit this section, thereby conserving word count.

By addressing these elements, your introduction will effectively integrate your literature review into the broader context of your academic paper or essay. This will, in turn, assist your reader in seamlessly following your overarching line of argumentation.

Introduction to a literature review chapter in thesis or dissertation

The literature review typically constitutes a distinct chapter within a thesis or dissertation. Often, it is Chapter 2 of a thesis or dissertation.

Some students choose to incorporate a brief introductory section at the beginning of each chapter, including the literature review chapter. Alternatively, others opt to seamlessly integrate the introduction into the initial sentences of the literature review itself. Both approaches are acceptable, provided that you incorporate the following elements:

- Purpose of the literature review and its relevance to the thesis/dissertation research: Explain the broader objectives of the literature review within the context of your research and how it contributes to your thesis or dissertation. Essentially, you’re telling the reader why this literature review is important and how it fits into the larger scope of your academic work.

- Primary argument: Succinctly communicate what you aim to prove, explain, or explore through the review of existing literature. This statement helps guide the reader’s understanding of the review’s purpose and what to expect from it.

- Preview of the literature review’s content: Provide a brief overview of the topics or themes that your literature review will cover. It’s like a roadmap for the reader, outlining the main areas of focus within the review. This preview can help the reader anticipate the structure and organization of your literature review.

- Methodology: If your literature review involved a specific research method, such as a systematic review or meta-analysis, you should briefly describe that methodology. However, this is not always necessary, especially if your literature review is more of a narrative synthesis without a distinct research method.

By addressing these elements, your introduction will empower your literature review to play a pivotal role in your thesis or dissertation research. It will accomplish this by integrating your research into the broader academic literature and providing a solid theoretical foundation for your work.

Comprehending the art of crafting your own literature review introduction becomes significantly more accessible when you have concrete examples to examine. Here, you will find several examples that meet, or in most cases, adhere to the criteria described earlier.

Example 1: An effective introduction for an academic literature review paper

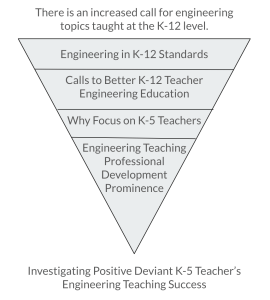

To begin, let’s delve into the introduction of an academic literature review paper. We will examine the paper “How does culture influence innovation? A systematic literature review”, which was published in 2018 in the journal Management Decision.

The entire introduction spans 611 words and is divided into five paragraphs. In this introduction, the authors accomplish the following:

- In the first paragraph, the authors introduce the broader topic of the literature review, which focuses on innovation and its significance in the context of economic competition. They underscore the importance of this topic, highlighting its relevance for both researchers and policymakers.

- In the second paragraph, the authors narrow down their focus to emphasize the specific role of culture in relation to innovation.

- In the third paragraph, the authors identify research gaps, noting that existing studies are often fragmented and disconnected. They then emphasize the value of conducting a systematic literature review to enhance our understanding of the topic.

- In the fourth paragraph, the authors introduce their specific objectives and explain how their insights can benefit other researchers and business practitioners.

- In the fifth and final paragraph, the authors provide an overview of the paper’s organization and structure.

In summary, this introduction stands as a solid example. While the authors deviate from previewing their key findings (which is a common practice at least in the social sciences), they do effectively cover all the other previously mentioned points.

Example 2: An effective introduction to a literature review section in an academic paper

The second example represents a typical academic paper, encompassing not only a literature review section but also empirical data, a case study, and other elements. We will closely examine the introduction to the literature review section in the paper “The environmentalism of the subalterns: a case study of environmental activism in Eastern Kurdistan/Rojhelat”, which was published in 2021 in the journal Local Environment.

The paper begins with a general introduction and then proceeds to the literature review, designated by the authors as their conceptual framework. Of particular interest is the first paragraph of this conceptual framework, comprising 142 words across five sentences:

“ A peripheral and marginalised nationality within a multinational though-Persian dominated Iranian society, the Kurdish people of Iranian Kurdistan (a region referred by the Kurds as Rojhelat/Eastern Kurdi-stan) have since the early twentieth century been subject to multifaceted and systematic discriminatory and exclusionary state policy in Iran. This condition has left a population of 12–15 million Kurds in Iran suffering from structural inequalities, disenfranchisement and deprivation. Mismanagement of Kurdistan’s natural resources and the degradation of its natural environmental are among examples of this disenfranchisement. As asserted by Julian Agyeman (2005), structural inequalities that sustain the domination of political and economic elites often simultaneously result in environmental degradation, injustice and discrimination against subaltern communities. This study argues that the environmental struggle in Eastern Kurdistan can be asserted as a (sub)element of the Kurdish liberation movement in Iran. Conceptually this research is inspired by and has been conducted through the lens of ‘subalternity’ ” ( Hassaniyan, 2021, p. 931 ).

In this first paragraph, the author is doing the following:

- The author contextualises the research

- The author links the research focus to the international literature on structural inequalities

- The author clearly presents the argument of the research

- The author clarifies how the research is inspired by and uses the concept of ‘subalternity’.

Thus, the author successfully introduces the literature review, from which point onward it dives into the main concept (‘subalternity’) of the research, and reviews the literature on socio-economic justice and environmental degradation.

While introductions to a literature review section aren’t always required to offer the same level of study context detail as demonstrated here, this introduction serves as a commendable model for orienting the reader within the literature review. It effectively underscores the literature review’s significance within the context of the study being conducted.

Examples 3-5: Effective introductions to literature review chapters

The introduction to a literature review chapter can vary in length, depending largely on the overall length of the literature review chapter itself. For example, a master’s thesis typically features a more concise literature review, thus necessitating a shorter introduction. In contrast, a Ph.D. thesis, with its more extensive literature review, often includes a more detailed introduction.

Numerous universities offer online repositories where you can access theses and dissertations from previous years, serving as valuable sources of reference. Many of these repositories, however, may require you to log in through your university account. Nevertheless, a few open-access repositories are accessible to anyone, such as the one by the University of Manchester . It’s important to note though that copyright restrictions apply to these resources, just as they would with published papers.

Master’s thesis literature review introduction

The first example is “Benchmarking Asymmetrical Heating Models of Spider Pulsar Companions” by P. Sun, a master’s thesis completed at the University of Manchester on January 9, 2024. The author, P. Sun, introduces the literature review chapter very briefly but effectively:

PhD thesis literature review chapter introduction

The second example is Deep Learning on Semi-Structured Data and its Applications to Video-Game AI, Woof, W. (Author). 31 Dec 2020, a PhD thesis completed at the University of Manchester . In Chapter 2, the author offers a comprehensive introduction to the topic in four paragraphs, with the final paragraph serving as an overview of the chapter’s structure:

PhD thesis literature review introduction

The last example is the doctoral thesis Metacognitive strategies and beliefs: Child correlates and early experiences Chan, K. Y. M. (Author). 31 Dec 2020 . The author clearly conducted a systematic literature review, commencing the review section with a discussion of the methodology and approach employed in locating and analyzing the selected records.

Having absorbed all of this information, let’s recap the essential steps and offer a succinct guide on how to proceed with creating your literature review introduction:

- Contextualize your review : Begin by clearly identifying the academic context in which your literature review resides and determining the necessary information to include.

- Outline your structure : Develop a structured outline for your literature review, highlighting the essential information you plan to incorporate in your introduction.

- Literature review process : Conduct a rigorous literature review, reviewing and analyzing relevant sources.

- Summarize and abstract : After completing the review, synthesize the findings and abstract key insights, trends, and knowledge gaps from the literature.

- Craft the introduction : Write your literature review introduction with meticulous attention to the seamless integration of your review into the larger context of your work. Ensure that your introduction effectively elucidates your rationale for the chosen review topics and the underlying reasons guiding your selection.

Master Academia

Get new content delivered directly to your inbox.

Subscribe and receive Master Academia's quarterly newsletter.

The best answers to "What are your plans for the future?"

10 tips for engaging your audience in academic writing, related articles.

10 key skills of successful master’s students

How to write effective cover letters for a paper submission

Dealing with failure as a PhD student

Reject decisions: Sample peer review comments and examples

Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

What is a Literature Review? How to Write It (with Examples)

A literature review is a critical analysis and synthesis of existing research on a particular topic. It provides an overview of the current state of knowledge, identifies gaps, and highlights key findings in the literature. 1 The purpose of a literature review is to situate your own research within the context of existing scholarship, demonstrating your understanding of the topic and showing how your work contributes to the ongoing conversation in the field. Learning how to write a literature review is a critical tool for successful research. Your ability to summarize and synthesize prior research pertaining to a certain topic demonstrates your grasp on the topic of study, and assists in the learning process.

Table of Contents

- What is the purpose of literature review?

- a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

- b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

- c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

- d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

- How to write a good literature review

- Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Select Databases for Searches:

- Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Review the Literature:

- Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- Frequently asked questions

What is a literature review?

A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with the existing literature, establishes the context for their own research, and contributes to scholarly conversations on the topic. One of the purposes of a literature review is also to help researchers avoid duplicating previous work and ensure that their research is informed by and builds upon the existing body of knowledge.

What is the purpose of literature review?

A literature review serves several important purposes within academic and research contexts. Here are some key objectives and functions of a literature review: 2

- Contextualizing the Research Problem: The literature review provides a background and context for the research problem under investigation. It helps to situate the study within the existing body of knowledge.

- Identifying Gaps in Knowledge: By identifying gaps, contradictions, or areas requiring further research, the researcher can shape the research question and justify the significance of the study. This is crucial for ensuring that the new research contributes something novel to the field.

- Understanding Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks: Literature reviews help researchers gain an understanding of the theoretical and conceptual frameworks used in previous studies. This aids in the development of a theoretical framework for the current research.

- Providing Methodological Insights: Another purpose of literature reviews is that it allows researchers to learn about the methodologies employed in previous studies. This can help in choosing appropriate research methods for the current study and avoiding pitfalls that others may have encountered.

- Establishing Credibility: A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with existing scholarship, establishing their credibility and expertise in the field. It also helps in building a solid foundation for the new research.

- Informing Hypotheses or Research Questions: The literature review guides the formulation of hypotheses or research questions by highlighting relevant findings and areas of uncertainty in existing literature.

Literature review example

Let’s delve deeper with a literature review example: Let’s say your literature review is about the impact of climate change on biodiversity. You might format your literature review into sections such as the effects of climate change on habitat loss and species extinction, phenological changes, and marine biodiversity. Each section would then summarize and analyze relevant studies in those areas, highlighting key findings and identifying gaps in the research. The review would conclude by emphasizing the need for further research on specific aspects of the relationship between climate change and biodiversity. The following literature review template provides a glimpse into the recommended literature review structure and content, demonstrating how research findings are organized around specific themes within a broader topic.

Literature Review on Climate Change Impacts on Biodiversity:

Climate change is a global phenomenon with far-reaching consequences, including significant impacts on biodiversity. This literature review synthesizes key findings from various studies:

a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

Climate change-induced alterations in temperature and precipitation patterns contribute to habitat loss, affecting numerous species (Thomas et al., 2004). The review discusses how these changes increase the risk of extinction, particularly for species with specific habitat requirements.

b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

Observations of range shifts and changes in the timing of biological events (phenology) are documented in response to changing climatic conditions (Parmesan & Yohe, 2003). These shifts affect ecosystems and may lead to mismatches between species and their resources.

c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

The review explores the impact of climate change on marine biodiversity, emphasizing ocean acidification’s threat to coral reefs (Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2007). Changes in pH levels negatively affect coral calcification, disrupting the delicate balance of marine ecosystems.

d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

Recognizing the urgency of the situation, the literature review discusses various adaptive strategies adopted by species and conservation efforts aimed at mitigating the impacts of climate change on biodiversity (Hannah et al., 2007). It emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary approaches for effective conservation planning.

How to write a good literature review

Writing a literature review involves summarizing and synthesizing existing research on a particular topic. A good literature review format should include the following elements.

Introduction: The introduction sets the stage for your literature review, providing context and introducing the main focus of your review.

- Opening Statement: Begin with a general statement about the broader topic and its significance in the field.

- Scope and Purpose: Clearly define the scope of your literature review. Explain the specific research question or objective you aim to address.

- Organizational Framework: Briefly outline the structure of your literature review, indicating how you will categorize and discuss the existing research.

- Significance of the Study: Highlight why your literature review is important and how it contributes to the understanding of the chosen topic.

- Thesis Statement: Conclude the introduction with a concise thesis statement that outlines the main argument or perspective you will develop in the body of the literature review.

Body: The body of the literature review is where you provide a comprehensive analysis of existing literature, grouping studies based on themes, methodologies, or other relevant criteria.

- Organize by Theme or Concept: Group studies that share common themes, concepts, or methodologies. Discuss each theme or concept in detail, summarizing key findings and identifying gaps or areas of disagreement.

- Critical Analysis: Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of each study. Discuss the methodologies used, the quality of evidence, and the overall contribution of each work to the understanding of the topic.

- Synthesis of Findings: Synthesize the information from different studies to highlight trends, patterns, or areas of consensus in the literature.

- Identification of Gaps: Discuss any gaps or limitations in the existing research and explain how your review contributes to filling these gaps.

- Transition between Sections: Provide smooth transitions between different themes or concepts to maintain the flow of your literature review.

Conclusion: The conclusion of your literature review should summarize the main findings, highlight the contributions of the review, and suggest avenues for future research.

- Summary of Key Findings: Recap the main findings from the literature and restate how they contribute to your research question or objective.

- Contributions to the Field: Discuss the overall contribution of your literature review to the existing knowledge in the field.

- Implications and Applications: Explore the practical implications of the findings and suggest how they might impact future research or practice.

- Recommendations for Future Research: Identify areas that require further investigation and propose potential directions for future research in the field.

- Final Thoughts: Conclude with a final reflection on the importance of your literature review and its relevance to the broader academic community.

Conducting a literature review

Conducting a literature review is an essential step in research that involves reviewing and analyzing existing literature on a specific topic. It’s important to know how to do a literature review effectively, so here are the steps to follow: 1

Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Select a topic that is relevant to your field of study.

- Clearly define your research question or objective. Determine what specific aspect of the topic do you want to explore?

Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Determine the timeframe for your literature review. Are you focusing on recent developments, or do you want a historical overview?

- Consider the geographical scope. Is your review global, or are you focusing on a specific region?

- Define the inclusion and exclusion criteria. What types of sources will you include? Are there specific types of studies or publications you will exclude?

Select Databases for Searches:

- Identify relevant databases for your field. Examples include PubMed, IEEE Xplore, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar.

- Consider searching in library catalogs, institutional repositories, and specialized databases related to your topic.

Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Develop a systematic search strategy using keywords, Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT), and other search techniques.

- Record and document your search strategy for transparency and replicability.

- Keep track of the articles, including publication details, abstracts, and links. Use citation management tools like EndNote, Zotero, or Mendeley to organize your references.

Review the Literature:

- Evaluate the relevance and quality of each source. Consider the methodology, sample size, and results of studies.

- Organize the literature by themes or key concepts. Identify patterns, trends, and gaps in the existing research.

- Summarize key findings and arguments from each source. Compare and contrast different perspectives.

- Identify areas where there is a consensus in the literature and where there are conflicting opinions.

- Provide critical analysis and synthesis of the literature. What are the strengths and weaknesses of existing research?

Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- Literature review outline should be based on themes, chronological order, or methodological approaches.

- Write a clear and coherent narrative that synthesizes the information gathered.

- Use proper citations for each source and ensure consistency in your citation style (APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.).

- Conclude your literature review by summarizing key findings, identifying gaps, and suggesting areas for future research.

The literature review sample and detailed advice on writing and conducting a review will help you produce a well-structured report. But remember that a literature review is an ongoing process, and it may be necessary to revisit and update it as your research progresses.

Frequently asked questions

A literature review is a critical and comprehensive analysis of existing literature (published and unpublished works) on a specific topic or research question and provides a synthesis of the current state of knowledge in a particular field. A well-conducted literature review is crucial for researchers to build upon existing knowledge, avoid duplication of efforts, and contribute to the advancement of their field. It also helps researchers situate their work within a broader context and facilitates the development of a sound theoretical and conceptual framework for their studies.

Literature review is a crucial component of research writing, providing a solid background for a research paper’s investigation. The aim is to keep professionals up to date by providing an understanding of ongoing developments within a specific field, including research methods, and experimental techniques used in that field, and present that knowledge in the form of a written report. Also, the depth and breadth of the literature review emphasizes the credibility of the scholar in his or her field.

Before writing a literature review, it’s essential to undertake several preparatory steps to ensure that your review is well-researched, organized, and focused. This includes choosing a topic of general interest to you and doing exploratory research on that topic, writing an annotated bibliography, and noting major points, especially those that relate to the position you have taken on the topic.

Literature reviews and academic research papers are essential components of scholarly work but serve different purposes within the academic realm. 3 A literature review aims to provide a foundation for understanding the current state of research on a particular topic, identify gaps or controversies, and lay the groundwork for future research. Therefore, it draws heavily from existing academic sources, including books, journal articles, and other scholarly publications. In contrast, an academic research paper aims to present new knowledge, contribute to the academic discourse, and advance the understanding of a specific research question. Therefore, it involves a mix of existing literature (in the introduction and literature review sections) and original data or findings obtained through research methods.

Literature reviews are essential components of academic and research papers, and various strategies can be employed to conduct them effectively. If you want to know how to write a literature review for a research paper, here are four common approaches that are often used by researchers. Chronological Review: This strategy involves organizing the literature based on the chronological order of publication. It helps to trace the development of a topic over time, showing how ideas, theories, and research have evolved. Thematic Review: Thematic reviews focus on identifying and analyzing themes or topics that cut across different studies. Instead of organizing the literature chronologically, it is grouped by key themes or concepts, allowing for a comprehensive exploration of various aspects of the topic. Methodological Review: This strategy involves organizing the literature based on the research methods employed in different studies. It helps to highlight the strengths and weaknesses of various methodologies and allows the reader to evaluate the reliability and validity of the research findings. Theoretical Review: A theoretical review examines the literature based on the theoretical frameworks used in different studies. This approach helps to identify the key theories that have been applied to the topic and assess their contributions to the understanding of the subject. It’s important to note that these strategies are not mutually exclusive, and a literature review may combine elements of more than one approach. The choice of strategy depends on the research question, the nature of the literature available, and the goals of the review. Additionally, other strategies, such as integrative reviews or systematic reviews, may be employed depending on the specific requirements of the research.

The literature review format can vary depending on the specific publication guidelines. However, there are some common elements and structures that are often followed. Here is a general guideline for the format of a literature review: Introduction: Provide an overview of the topic. Define the scope and purpose of the literature review. State the research question or objective. Body: Organize the literature by themes, concepts, or chronology. Critically analyze and evaluate each source. Discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the studies. Highlight any methodological limitations or biases. Identify patterns, connections, or contradictions in the existing research. Conclusion: Summarize the key points discussed in the literature review. Highlight the research gap. Address the research question or objective stated in the introduction. Highlight the contributions of the review and suggest directions for future research.

Both annotated bibliographies and literature reviews involve the examination of scholarly sources. While annotated bibliographies focus on individual sources with brief annotations, literature reviews provide a more in-depth, integrated, and comprehensive analysis of existing literature on a specific topic. The key differences are as follows:

References

- Denney, A. S., & Tewksbury, R. (2013). How to write a literature review. Journal of criminal justice education , 24 (2), 218-234.

- Pan, M. L. (2016). Preparing literature reviews: Qualitative and quantitative approaches . Taylor & Francis.

- Cantero, C. (2019). How to write a literature review. San José State University Writing Center .

Paperpal is an AI writing assistant that help academics write better, faster with real-time suggestions for in-depth language and grammar correction. Trained on millions of research manuscripts enhanced by professional academic editors, Paperpal delivers human precision at machine speed.

Try it for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime , which unlocks unlimited access to premium features like academic translation, paraphrasing, contextual synonyms, consistency checks and more. It’s like always having a professional academic editor by your side! Go beyond limitations and experience the future of academic writing. Get Paperpal Prime now at just US$19 a month!

Related Reads:

- Empirical Research: A Comprehensive Guide for Academics

- How to Write a Scientific Paper in 10 Steps

- Life Sciences Papers: 9 Tips for Authors Writing in Biological Sciences

- What is an Argumentative Essay? How to Write It (With Examples)

6 Tips for Post-Doc Researchers to Take Their Career to the Next Level

Self-plagiarism in research: what it is and how to avoid it, you may also like, 4 ways paperpal encourages responsible writing with ai, what are scholarly sources and where can you..., how to write a hypothesis types and examples , measuring academic success: definition & strategies for excellence, what is academic writing: tips for students, why traditional editorial process needs an upgrade, paperpal’s new ai research finder empowers authors to..., what is hedging in academic writing , how to use ai to enhance your college..., ai + human expertise – a paradigm shift....

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

- UConn Library

- Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide

- Introduction

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide — Introduction

- Getting Started

- How to Pick a Topic

- Strategies to Find Sources

- Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

What are Literature Reviews?

So, what is a literature review? "A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries." Taylor, D. The literature review: A few tips on conducting it . University of Toronto Health Sciences Writing Centre.

Goals of Literature Reviews

What are the goals of creating a Literature Review? A literature could be written to accomplish different aims:

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1997). Writing narrative literature reviews . Review of General Psychology , 1 (3), 311-320.

What kinds of sources require a Literature Review?

- A research paper assigned in a course

- A thesis or dissertation

- A grant proposal

- An article intended for publication in a journal

All these instances require you to collect what has been written about your research topic so that you can demonstrate how your own research sheds new light on the topic.

Types of Literature Reviews

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

Narrative review: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific topic/research and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weakness, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section which summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Example : Predictors and Outcomes of U.S. Quality Maternity Leave: A Review and Conceptual Framework: 10.1177/08948453211037398

Systematic review : "The authors of a systematic review use a specific procedure to search the research literature, select the studies to include in their review, and critically evaluate the studies they find." (p. 139). Nelson, L. K. (2013). Research in Communication Sciences and Disorders . Plural Publishing.

- Example : The effect of leave policies on increasing fertility: a systematic review: 10.1057/s41599-022-01270-w

Meta-analysis : "Meta-analysis is a method of reviewing research findings in a quantitative fashion by transforming the data from individual studies into what is called an effect size and then pooling and analyzing this information. The basic goal in meta-analysis is to explain why different outcomes have occurred in different studies." (p. 197). Roberts, M. C., & Ilardi, S. S. (2003). Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology . Blackwell Publishing.

- Example : Employment Instability and Fertility in Europe: A Meta-Analysis: 10.1215/00703370-9164737

Meta-synthesis : "Qualitative meta-synthesis is a type of qualitative study that uses as data the findings from other qualitative studies linked by the same or related topic." (p.312). Zimmer, L. (2006). Qualitative meta-synthesis: A question of dialoguing with texts . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 53 (3), 311-318.

- Example : Women’s perspectives on career successes and barriers: A qualitative meta-synthesis: 10.1177/05390184221113735

Literature Reviews in the Health Sciences

- UConn Health subject guide on systematic reviews Explanation of the different review types used in health sciences literature as well as tools to help you find the right review type

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: How to Pick a Topic >>

- Last Updated: Sep 21, 2022 2:16 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uconn.edu/literaturereview

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

How To Write A Literature Review - A Complete Guide

Table of Contents

A literature review is much more than just another section in your research paper. It forms the very foundation of your research. It is a formal piece of writing where you analyze the existing theoretical framework, principles, and assumptions and use that as a base to shape your approach to the research question.

Curating and drafting a solid literature review section not only lends more credibility to your research paper but also makes your research tighter and better focused. But, writing literature reviews is a difficult task. It requires extensive reading, plus you have to consider market trends and technological and political changes, which tend to change in the blink of an eye.

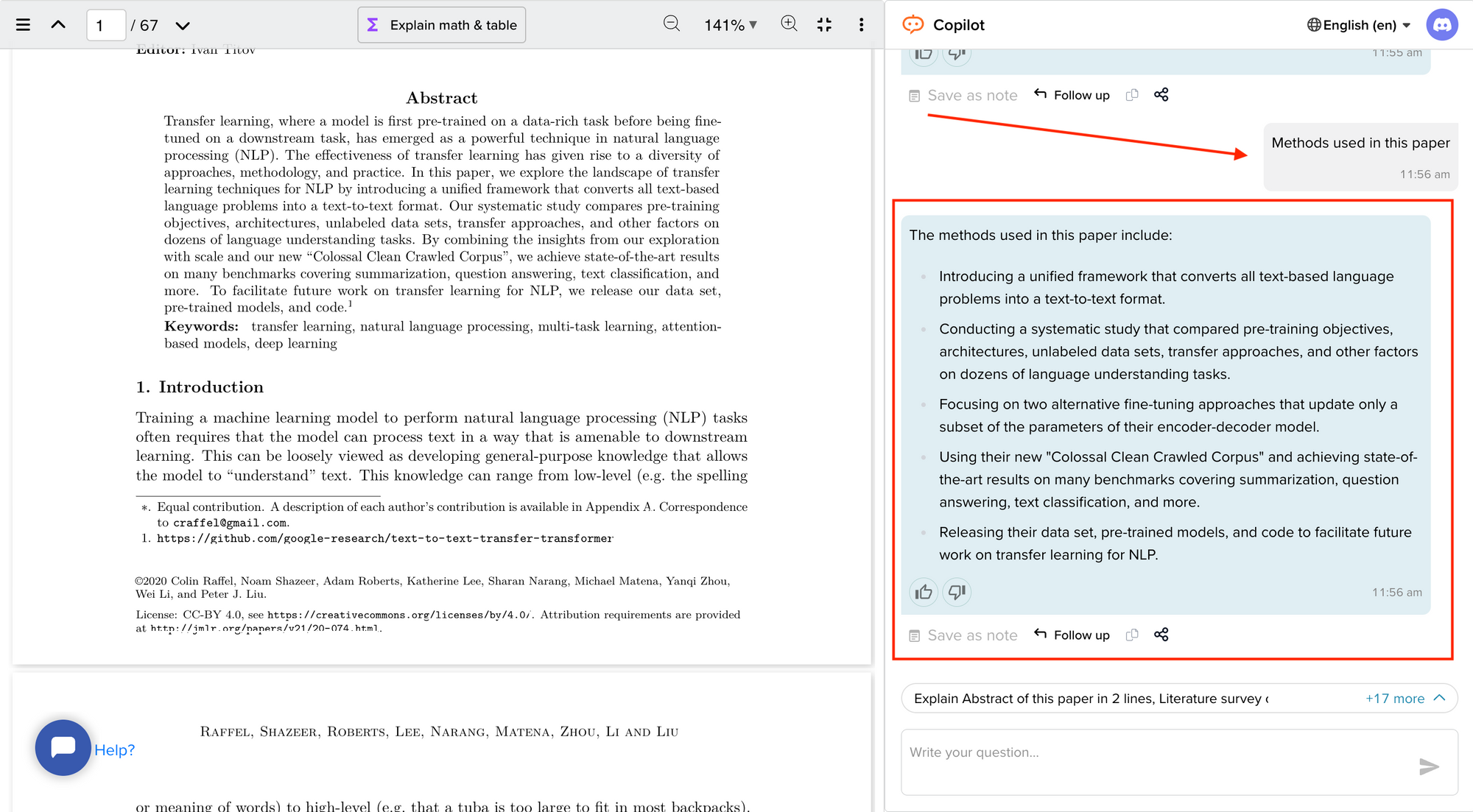

Now streamline your literature review process with the help of SciSpace Copilot. With this AI research assistant, you can efficiently synthesize and analyze a vast amount of information, identify key themes and trends, and uncover gaps in the existing research. Get real-time explanations, summaries, and answers to your questions for the paper you're reviewing, making navigating and understanding the complex literature landscape easier.

In this comprehensive guide, we will explore everything from the definition of a literature review, its appropriate length, various types of literature reviews, and how to write one.

What is a literature review?

A literature review is a collation of survey, research, critical evaluation, and assessment of the existing literature in a preferred domain.

Eminent researcher and academic Arlene Fink, in her book Conducting Research Literature Reviews , defines it as the following:

“A literature review surveys books, scholarly articles, and any other sources relevant to a particular issue, area of research, or theory, and by so doing, provides a description, summary, and critical evaluation of these works in relation to the research problem being investigated.

Literature reviews are designed to provide an overview of sources you have explored while researching a particular topic, and to demonstrate to your readers how your research fits within a larger field of study.”

Simply put, a literature review can be defined as a critical discussion of relevant pre-existing research around your research question and carving out a definitive place for your study in the existing body of knowledge. Literature reviews can be presented in multiple ways: a section of an article, the whole research paper itself, or a chapter of your thesis.

A literature review does function as a summary of sources, but it also allows you to analyze further, interpret, and examine the stated theories, methods, viewpoints, and, of course, the gaps in the existing content.

As an author, you can discuss and interpret the research question and its various aspects and debate your adopted methods to support the claim.

What is the purpose of a literature review?

A literature review is meant to help your readers understand the relevance of your research question and where it fits within the existing body of knowledge. As a researcher, you should use it to set the context, build your argument, and establish the need for your study.

What is the importance of a literature review?

The literature review is a critical part of research papers because it helps you:

- Gain an in-depth understanding of your research question and the surrounding area

- Convey that you have a thorough understanding of your research area and are up-to-date with the latest changes and advancements

- Establish how your research is connected or builds on the existing body of knowledge and how it could contribute to further research

- Elaborate on the validity and suitability of your theoretical framework and research methodology

- Identify and highlight gaps and shortcomings in the existing body of knowledge and how things need to change

- Convey to readers how your study is different or how it contributes to the research area

How long should a literature review be?

Ideally, the literature review should take up 15%-40% of the total length of your manuscript. So, if you have a 10,000-word research paper, the minimum word count could be 1500.

Your literature review format depends heavily on the kind of manuscript you are writing — an entire chapter in case of doctoral theses, a part of the introductory section in a research article, to a full-fledged review article that examines the previously published research on a topic.

Another determining factor is the type of research you are doing. The literature review section tends to be longer for secondary research projects than primary research projects.

What are the different types of literature reviews?

All literature reviews are not the same. There are a variety of possible approaches that you can take. It all depends on the type of research you are pursuing.

Here are the different types of literature reviews:

Argumentative review

It is called an argumentative review when you carefully present literature that only supports or counters a specific argument or premise to establish a viewpoint.

Integrative review

It is a type of literature review focused on building a comprehensive understanding of a topic by combining available theoretical frameworks and empirical evidence.

Methodological review

This approach delves into the ''how'' and the ''what" of the research question — you cannot look at the outcome in isolation; you should also review the methodology used.

Systematic review

This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research and collect, report, and analyze data from the studies included in the review.

Meta-analysis review

Meta-analysis uses statistical methods to summarize the results of independent studies. By combining information from all relevant studies, meta-analysis can provide more precise estimates of the effects than those derived from the individual studies included within a review.

Historical review

Historical literature reviews focus on examining research throughout a period, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, or phenomenon emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and identify future research's likely directions.

Theoretical Review

This form aims to examine the corpus of theory accumulated regarding an issue, concept, theory, and phenomenon. The theoretical literature review helps to establish what theories exist, the relationships between them, the degree the existing approaches have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested.

Scoping Review

The Scoping Review is often used at the beginning of an article, dissertation, or research proposal. It is conducted before the research to highlight gaps in the existing body of knowledge and explains why the project should be greenlit.

State-of-the-Art Review

The State-of-the-Art review is conducted periodically, focusing on the most recent research. It describes what is currently known, understood, or agreed upon regarding the research topic and highlights where there are still disagreements.

Can you use the first person in a literature review?

When writing literature reviews, you should avoid the usage of first-person pronouns. It means that instead of "I argue that" or "we argue that," the appropriate expression would be "this research paper argues that."

Do you need an abstract for a literature review?

Ideally, yes. It is always good to have a condensed summary that is self-contained and independent of the rest of your review. As for how to draft one, you can follow the same fundamental idea when preparing an abstract for a literature review. It should also include:

- The research topic and your motivation behind selecting it

- A one-sentence thesis statement

- An explanation of the kinds of literature featured in the review

- Summary of what you've learned

- Conclusions you drew from the literature you reviewed

- Potential implications and future scope for research

Here's an example of the abstract of a literature review

Is a literature review written in the past tense?

Yes, the literature review should ideally be written in the past tense. You should not use the present or future tense when writing one. The exceptions are when you have statements describing events that happened earlier than the literature you are reviewing or events that are currently occurring; then, you can use the past perfect or present perfect tenses.

How many sources for a literature review?

There are multiple approaches to deciding how many sources to include in a literature review section. The first approach would be to look level you are at as a researcher. For instance, a doctoral thesis might need 60+ sources. In contrast, you might only need to refer to 5-15 sources at the undergraduate level.

The second approach is based on the kind of literature review you are doing — whether it is merely a chapter of your paper or if it is a self-contained paper in itself. When it is just a chapter, sources should equal the total number of pages in your article's body. In the second scenario, you need at least three times as many sources as there are pages in your work.

Quick tips on how to write a literature review

To know how to write a literature review, you must clearly understand its impact and role in establishing your work as substantive research material.

You need to follow the below-mentioned steps, to write a literature review:

- Outline the purpose behind the literature review

- Search relevant literature

- Examine and assess the relevant resources

- Discover connections by drawing deep insights from the resources

- Structure planning to write a good literature review

1. Outline and identify the purpose of a literature review

As a first step on how to write a literature review, you must know what the research question or topic is and what shape you want your literature review to take. Ensure you understand the research topic inside out, or else seek clarifications. You must be able to the answer below questions before you start:

- How many sources do I need to include?

- What kind of sources should I analyze?

- How much should I critically evaluate each source?

- Should I summarize, synthesize or offer a critique of the sources?

- Do I need to include any background information or definitions?

Additionally, you should know that the narrower your research topic is, the swifter it will be for you to restrict the number of sources to be analyzed.

2. Search relevant literature

Dig deeper into search engines to discover what has already been published around your chosen topic. Make sure you thoroughly go through appropriate reference sources like books, reports, journal articles, government docs, and web-based resources.

You must prepare a list of keywords and their different variations. You can start your search from any library’s catalog, provided you are an active member of that institution. The exact keywords can be extended to widen your research over other databases and academic search engines like:

- Google Scholar

- Microsoft Academic

- Science.gov

Besides, it is not advisable to go through every resource word by word. Alternatively, what you can do is you can start by reading the abstract and then decide whether that source is relevant to your research or not.

Additionally, you must spend surplus time assessing the quality and relevance of resources. It would help if you tried preparing a list of citations to ensure that there lies no repetition of authors, publications, or articles in the literature review.

3. Examine and assess the sources

It is nearly impossible for you to go through every detail in the research article. So rather than trying to fetch every detail, you have to analyze and decide which research sources resemble closest and appear relevant to your chosen domain.

While analyzing the sources, you should look to find out answers to questions like:

- What question or problem has the author been describing and debating?

- What is the definition of critical aspects?

- How well the theories, approach, and methodology have been explained?

- Whether the research theory used some conventional or new innovative approach?

- How relevant are the key findings of the work?

- In what ways does it relate to other sources on the same topic?

- What challenges does this research paper pose to the existing theory

- What are the possible contributions or benefits it adds to the subject domain?

Be always mindful that you refer only to credible and authentic resources. It would be best if you always take references from different publications to validate your theory.

Always keep track of important information or data you can present in your literature review right from the beginning. It will help steer your path from any threats of plagiarism and also make it easier to curate an annotated bibliography or reference section.

4. Discover connections

At this stage, you must start deciding on the argument and structure of your literature review. To accomplish this, you must discover and identify the relations and connections between various resources while drafting your abstract.

A few aspects that you should be aware of while writing a literature review include:

- Rise to prominence: Theories and methods that have gained reputation and supporters over time.

- Constant scrutiny: Concepts or theories that repeatedly went under examination.

- Contradictions and conflicts: Theories, both the supporting and the contradictory ones, for the research topic.

- Knowledge gaps: What exactly does it fail to address, and how to bridge them with further research?

- Influential resources: Significant research projects available that have been upheld as milestones or perhaps, something that can modify the current trends

Once you join the dots between various past research works, it will be easier for you to draw a conclusion and identify your contribution to the existing knowledge base.

5. Structure planning to write a good literature review

There exist different ways towards planning and executing the structure of a literature review. The format of a literature review varies and depends upon the length of the research.

Like any other research paper, the literature review format must contain three sections: introduction, body, and conclusion. The goals and objectives of the research question determine what goes inside these three sections.

Nevertheless, a good literature review can be structured according to the chronological, thematic, methodological, or theoretical framework approach.

Literature review samples

1. Standalone

2. As a section of a research paper

How SciSpace Discover makes literature review a breeze?

SciSpace Discover is a one-stop solution to do an effective literature search and get barrier-free access to scientific knowledge. It is an excellent repository where you can find millions of only peer-reviewed articles and full-text PDF files. Here’s more on how you can use it:

Find the right information

Find what you want quickly and easily with comprehensive search filters that let you narrow down papers according to PDF availability, year of publishing, document type, and affiliated institution. Moreover, you can sort the results based on the publishing date, citation count, and relevance.

Assess credibility of papers quickly

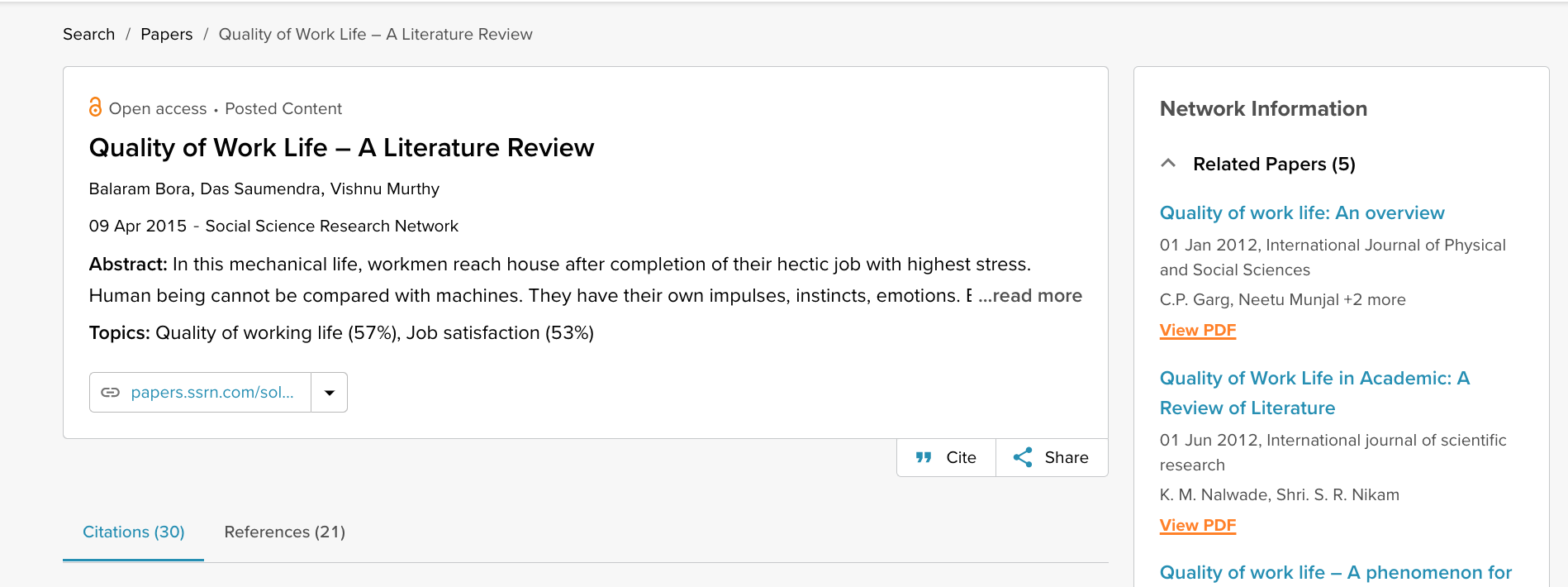

When doing the literature review, it is critical to establish the quality of your sources. They form the foundation of your research. SciSpace Discover helps you assess the quality of a source by providing an overview of its references, citations, and performance metrics.

Get the complete picture in no time

SciSpace Discover’s personalized suggestion engine helps you stay on course and get the complete picture of the topic from one place. Every time you visit an article page, it provides you links to related papers. Besides that, it helps you understand what’s trending, who are the top authors, and who are the leading publishers on a topic.

Make referring sources super easy

To ensure you don't lose track of your sources, you must start noting down your references when doing the literature review. SciSpace Discover makes this step effortless. Click the 'cite' button on an article page, and you will receive preloaded citation text in multiple styles — all you've to do is copy-paste it into your manuscript.

Final tips on how to write a literature review

A massive chunk of time and effort is required to write a good literature review. But, if you go about it systematically, you'll be able to save a ton of time and build a solid foundation for your research.

We hope this guide has helped you answer several key questions you have about writing literature reviews.

Would you like to explore SciSpace Discover and kick off your literature search right away? You can get started here .

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. how to start a literature review.

• What questions do you want to answer?

• What sources do you need to answer these questions?

• What information do these sources contain?

• How can you use this information to answer your questions?

2. What to include in a literature review?

• A brief background of the problem or issue

• What has previously been done to address the problem or issue

• A description of what you will do in your project

• How this study will contribute to research on the subject

3. Why literature review is important?

The literature review is an important part of any research project because it allows the writer to look at previous studies on a topic and determine existing gaps in the literature, as well as what has already been done. It will also help them to choose the most appropriate method for their own study.

4. How to cite a literature review in APA format?

To cite a literature review in APA style, you need to provide the author's name, the title of the article, and the year of publication. For example: Patel, A. B., & Stokes, G. S. (2012). The relationship between personality and intelligence: A meta-analysis of longitudinal research. Personality and Individual Differences, 53(1), 16-21

5. What are the components of a literature review?

• A brief introduction to the topic, including its background and context. The introduction should also include a rationale for why the study is being conducted and what it will accomplish.

• A description of the methodologies used in the study. This can include information about data collection methods, sample size, and statistical analyses.

• A presentation of the findings in an organized format that helps readers follow along with the author's conclusions.

6. What are common errors in writing literature review?

• Not spending enough time to critically evaluate the relevance of resources, observations and conclusions.

• Totally relying on secondary data while ignoring primary data.

• Letting your personal bias seep into your interpretation of existing literature.

• No detailed explanation of the procedure to discover and identify an appropriate literature review.

7. What are the 5 C's of writing literature review?

• Cite - the sources you utilized and referenced in your research.

• Compare - existing arguments, hypotheses, methodologies, and conclusions found in the knowledge base.

• Contrast - the arguments, topics, methodologies, approaches, and disputes that may be found in the literature.

• Critique - the literature and describe the ideas and opinions you find more convincing and why.

• Connect - the various studies you reviewed in your research.

8. How many sources should a literature review have?

When it is just a chapter, sources should equal the total number of pages in your article's body. if it is a self-contained paper in itself, you need at least three times as many sources as there are pages in your work.

9. Can literature review have diagrams?

• To represent an abstract idea or concept

• To explain the steps of a process or procedure

• To help readers understand the relationships between different concepts

10. How old should sources be in a literature review?

Sources for a literature review should be as current as possible or not older than ten years. The only exception to this rule is if you are reviewing a historical topic and need to use older sources.

11. What are the types of literature review?

• Argumentative review

• Integrative review

• Methodological review

• Systematic review

• Meta-analysis review

• Historical review

• Theoretical review

• Scoping review

• State-of-the-Art review

12. Is a literature review mandatory?

Yes. Literature review is a mandatory part of any research project. It is a critical step in the process that allows you to establish the scope of your research, and provide a background for the rest of your work.

But before you go,

- Six Online Tools for Easy Literature Review

- Evaluating literature review: systematic vs. scoping reviews

- Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review

- Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples

You might also like

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Types of Essays in Academic Writing - Quick Guide (2024)

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

Published on 22 February 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 7 June 2022.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research.

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarise sources – it analyses, synthesises, and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Why write a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1: search for relevant literature, step 2: evaluate and select sources, step 3: identify themes, debates and gaps, step 4: outline your literature review’s structure, step 5: write your literature review, frequently asked questions about literature reviews, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a dissertation or thesis, you will have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position yourself in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your dissertation addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

You might also have to write a literature review as a stand-alone assignment. In this case, the purpose is to evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of scholarly debates around a topic.

The content will look slightly different in each case, but the process of conducting a literature review follows the same steps. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research objectives and questions .

If you are writing a literature review as a stand-alone assignment, you will have to choose a focus and develop a central question to direct your search. Unlike a dissertation research question, this question has to be answerable without collecting original data. You should be able to answer it based only on a review of existing publications.

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research topic. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list if you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health