Ideas and insights from Harvard Business Publishing Corporate Learning

Powerful and Effective Presentation Skills: More in Demand Now Than Ever

When we talk with our L&D colleagues from around the globe, we often hear that presentation skills training is one of the top opportunities they’re looking to provide their learners. And this holds true whether their learners are individual contributors, people managers, or senior leaders. This is not surprising.

Effective communications skills are a powerful career activator, and most of us are called upon to communicate in some type of formal presentation mode at some point along the way.

For instance, you might be asked to brief management on market research results, walk your team through a new process, lay out the new budget, or explain a new product to a client or prospect. Or you may want to build support for a new idea, bring a new employee into the fold, or even just present your achievements to your manager during your performance review.

And now, with so many employees working from home or in hybrid mode, and business travel in decline, there’s a growing need to find new ways to make effective presentations when the audience may be fully virtual or a combination of in person and remote attendees.

Whether you’re making a standup presentation to a large live audience, or a sit-down one-on-one, whether you’re delivering your presentation face to face or virtually, solid presentation skills matter.

Even the most seasoned and accomplished presenters may need to fine-tune or update their skills. Expectations have changed over the last decade or so. Yesterday’s PowerPoint which primarily relied on bulleted points, broken up by the occasional clip-art image, won’t cut it with today’s audience.

The digital revolution has revolutionized the way people want to receive information. People expect presentations that are more visually interesting. They expect to see data, metrics that support assertions. And now, with so many previously in-person meetings occurring virtually, there’s an entirely new level of technical preparedness required.

The leadership development tools and the individual learning opportunities you’re providing should include presentation skills training that covers both the evergreen fundamentals and the up-to-date capabilities that can make or break a presentation.

So, just what should be included in solid presentation skills training? Here’s what I think.

The fundamentals will always apply When it comes to making a powerful and effective presentation, the fundamentals will always apply. You need to understand your objective. Is it strictly to convey information, so that your audience’s knowledge is increased? Is it to persuade your audience to take some action? Is it to convince people to support your idea? Once you understand what your objective is, you need to define your central message. There may be a lot of things you want to share with your audience during your presentation, but find – and stick with – the core, the most important point you want them to walk away with. And make sure that your message is clear and compelling.

You also need to tailor your presentation to your audience. Who are they and what might they be expecting? Say you’re giving a product pitch to a client. A technical team may be interested in a lot of nitty-gritty product detail. The business side will no doubt be more interested in what returns they can expect on their investment.

Another consideration is the setting: is this a formal presentation to a large audience with questions reserved for the end, or a presentation in a smaller setting where there’s the possibility for conversation throughout? Is your presentation virtual or in-person? To be delivered individually or as a group? What time of the day will you be speaking? Will there be others speaking before you and might that impact how your message will be received?

Once these fundamentals are established, you’re in building mode. What are the specific points you want to share that will help you best meet your objective and get across your core message? Now figure out how to convey those points in the clearest, most straightforward, and succinct way. This doesn’t mean that your presentation has to be a series of clipped bullet points. No one wants to sit through a presentation in which the presenter reads through what’s on the slide. You can get your points across using stories, fact, diagrams, videos, props, and other types of media.

Visual design matters While you don’t want to clutter up your presentation with too many visual elements that don’t serve your objective and can be distracting, using a variety of visual formats to convey your core message will make your presentation more memorable than slides filled with text. A couple of tips: avoid images that are cliched and overdone. Be careful not to mix up too many different types of images. If you’re using photos, stick with photos. If you’re using drawn images, keep the style consistent. When data are presented, stay consistent with colors and fonts from one type of chart to the next. Keep things clear and simple, using data to support key points without overwhelming your audience with too much information. And don’t assume that your audience is composed of statisticians (unless, of course, it is).

When presenting qualitative data, brief videos provide a way to engage your audience and create emotional connection and impact. Word clouds are another way to get qualitative data across.

Practice makes perfect You’ve pulled together a perfect presentation. But it likely won’t be perfect unless it’s well delivered. So don’t forget to practice your presentation ahead of time. Pro tip: record yourself as you practice out loud. This will force you to think through what you’re going to say for each element of your presentation. And watching your recording will help you identify your mistakes—such as fidgeting, using too many fillers (such as “umm,” or “like”), or speaking too fast.

A key element of your preparation should involve anticipating any technical difficulties. If you’ve embedded videos, make sure they work. If you’re presenting virtually, make sure that the lighting is good, and that your speaker and camera are working. Whether presenting in person or virtually, get there early enough to work out any technical glitches before your presentation is scheduled to begin. Few things are a bigger audience turn-off than sitting there watching the presenter struggle with the delivery mechanisms!

Finally, be kind to yourself. Despite thorough preparation and practice, sometimes, things go wrong, and you need to recover in the moment, adapt, and carry on. It’s unlikely that you’ll have caused any lasting damage and the important thing is to learn from your experience, so your next presentation is stronger.

How are you providing presentation skills training for your learners?

Manika Gandhi is Senior Learning Design Manager at Harvard Business Publishing Corporate Learning. Email her at [email protected] .

Let’s talk

Change isn’t easy, but we can help. Together we’ll create informed and inspired leaders ready to shape the future of your business.

© 2024 Harvard Business School Publishing. All rights reserved. Harvard Business Publishing is an affiliate of Harvard Business School.

- Privacy Policy

- Copyright Information

- Terms of Use

- About Harvard Business Publishing

- Higher Education

- Harvard Business Review

- Harvard Business School

We use cookies to understand how you use our site and to improve your experience. By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies and revised Privacy Policy .

Cookie and Privacy Settings

We may request cookies to be set on your device. We use cookies to let us know when you visit our websites, how you interact with us, to enrich your user experience, and to customize your relationship with our website.

Click on the different category headings to find out more. You can also change some of your preferences. Note that blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience on our websites and the services we are able to offer.

These cookies are strictly necessary to provide you with services available through our website and to use some of its features.

Because these cookies are strictly necessary to deliver the website, refusing them will have impact how our site functions. You always can block or delete cookies by changing your browser settings and force blocking all cookies on this website. But this will always prompt you to accept/refuse cookies when revisiting our site.

We fully respect if you want to refuse cookies but to avoid asking you again and again kindly allow us to store a cookie for that. You are free to opt out any time or opt in for other cookies to get a better experience. If you refuse cookies we will remove all set cookies in our domain.

We provide you with a list of stored cookies on your computer in our domain so you can check what we stored. Due to security reasons we are not able to show or modify cookies from other domains. You can check these in your browser security settings.

We also use different external services like Google Webfonts, Google Maps, and external Video providers. Since these providers may collect personal data like your IP address we allow you to block them here. Please be aware that this might heavily reduce the functionality and appearance of our site. Changes will take effect once you reload the page.

Google Webfont Settings:

Google Map Settings:

Google reCaptcha Settings:

Vimeo and Youtube video embeds:

You can read about our cookies and privacy settings in detail on our Privacy Policy Page.

- Onsite training

3,000,000+ delegates

15,000+ clients

1,000+ locations

- KnowledgePass

- Log a ticket

01344203999 Available 24/7

The Importance of Presentation Skills: That You Must Know About

Uncover The Importance of Presentation Skills in this comprehensive blog. Begin with a brief introduction to the art of effective presentations and its wide-reaching significance. Delve into the vital role of presentation skills in both your personal and professional life, understanding how they can shape your success.

Exclusive 40% OFF

Training Outcomes Within Your Budget!

We ensure quality, budget-alignment, and timely delivery by our expert instructors.

Share this Resource

- Effective Communication Skills

- Presenting with Impact Training

- Interpersonal Skills Training Course

- Effective Presentation Skills & Techniques

- Public Speaking Course

Table of Contents

1) A brief introduction to Presentation Skills

2) Importance of Presentation Skills in personal life

3) Importance of Presentation Skills in professional life

4) Tips to improve your Presentation Skills

5) Conclusion

A brief introduction to Presentation Skills

Presentation skills can be defined as the ability to deliver information confidently and persuasively to engage and influence the audience. Be it in personal or professional settings; mastering Presentation Skills empowers individuals to convey their ideas with clarity, build confidence, and leave a lasting impression. From public speaking to business pitches, honing these skills can lead to greater success in diverse spheres of life. You can also refer to various presentation skills interview questions and answer to build you confidence! This blog will also look into the advantages and disadvantages of presentations .It is therefore important to understand the elements of presentations .

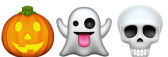

Importance of Presentation Skills in personal life

Effective Presentation skills are not limited to professional settings alone; they play a significant role in personal life as well. Let us now dive deeper into the Importance of Presentation Skills in one’s personal life:

Expressing ideas clearly

In day-to-day conversations with family, friends, or acquaintances, having good Presentation skills enables you to articulate your thoughts and ideas clearly. Whether you're discussing plans for the weekend or sharing your opinions on a particular topic, being an effective communicator encourages better understanding and engagement.

Enhancing social confidence

Many individuals struggle with social anxiety or nervousness in social gatherings. Mastering Presentation skills helps boost self-confidence, making it easier to navigate social situations with ease. The ability to present yourself confidently and engage others in conversation enhances your social life and opens doors to new relationships.

Creating memories on special occasions

There are moments in life that call for public speaking, such as proposing a toast at a wedding, delivering a speech at a family gathering, or giving a Presentation during special events. Having polished Presentation skills enables you to leave a positive and lasting impression on the audience, making these occasions even more memorable.

Handling challenging conversations

Life often presents challenging situations that require delicate communication, such as expressing condolences or resolving conflicts. Strong Presentation skills help you convey your feelings and thoughts sensitively, encouraging effective and empathetic communication during difficult times.

Building stronger relationships

Being a skilled presenter means being a good listener as well. Active listening is a fundamental aspect of effective Presentations, and when applied in personal relationships, it strengthens bonds and builds trust. Empathising with others and showing genuine interest in their stories and opinions enhances the quality of your relationships.

Advocating for personal goals

Whether you're pursuing personal projects or seeking support for a cause you're passionate about, the ability to present your ideas persuasively helps garner support and enthusiasm from others. This can be beneficial in achieving personal goals and making a positive impact on your community.

Inspiring and motivating others

In one’s personal life, Presentation skills are not just about delivering formal speeches; they also involve inspiring and motivating others through your actions and words. Whether you're sharing your experiences, mentoring someone, or encouraging loved ones during tough times, your Presentation skills can be a source of inspiration for others.

Exuding leadership traits

Effective Presentation skills go hand in hand with leadership qualities. Being able to communicate clearly and influence others' perspectives positions you as a leader within your family, social circles, or community. Leadership in personal life involves guiding and supporting others towards positive outcomes.

Unlock your full potential as a presenter with our Presentation Skills Training Course. Join now!

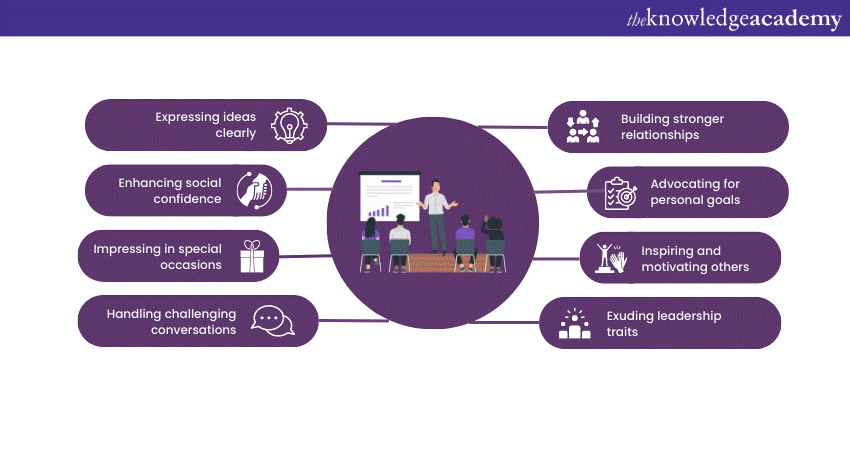

Importance of Presentation Skills in professional life

Effective Presentation skills are a vital asset for career growth and success in professional life. Let us now explore the importance of Presentation skills for students and workers:

Impressing employers and clients

During job interviews or business meetings, a well-delivered Presentation showcases your knowledge, confidence, and ability to communicate ideas effectively. It impresses employers, clients, and potential investors, leaving a positive and memorable impression that can tilt the scales in your favour.

Advancing in your career

In the corporate world, promotions and career advancements often involve presenting your achievements, ideas, and future plans to decision-makers. Strong Presentation skills demonstrate your leadership potential and readiness for higher responsibilities, opening doors to new opportunities.

Effective team collaboration

As a professional, you often need to present projects, strategies, or updates to your team or colleagues. A compelling Presentation facilitates better understanding and association among team members, leading to more productive and successful projects.

Persuasive selling techniques

For sales and marketing professionals, Presentation skills are instrumental in persuading potential customers to choose your products or services. An engaging sales pitch can sway buying decisions, leading to increased revenue and business growth.

Creating impactful proposals

In the corporate world, proposals are crucial for securing new partnerships or business deals. A well-structured and compelling Presentation can make your proposal stand out and increase the chances of successful negotiations.

Gaining and retaining clients

Whether you are a freelancer, consultant, or business owner, Presentation skills play a key role in winning and retaining clients. A captivating Presentation not only convinces clients of your capabilities but also builds trust and promotes long-term relationships.

Enhancing public speaking engagements

Professional life often involves speaking at conferences, seminars, or industry events. Being a confident and engaging speaker allows you to deliver your message effectively, position yourself as an expert, and expand your professional network.

Influencing stakeholders and decision-makers

As you climb the corporate ladder, you may find yourself presenting to senior management or board members. Effective Presentations are essential for gaining support for your ideas, projects, or initiatives from key stakeholders.

Handling meetings and discussions

In meetings, being able to present your thoughts clearly and concisely contributes to productive discussions and efficient decision-making. It ensures that your ideas are understood and considered by colleagues and superiors.

Professional development

Investing time in honing Presentation skills is a form of professional development. As you become a more effective presenter, you become a more valuable asset to your organisation and industry.

Building a personal brand

A strong personal brand is vital for professional success. Impressive Presentations contribute to building a positive reputation and positioning yourself as a thought leader or industry expert.

Career transitions and interviews

When seeking new opportunities or transitioning to a different industry, Presentation Skills are essential for communicating your transferable skills and showcasing your adaptability to potential employers.

Take your Presentations to the next level with our Effective Presentation Skills & Techniques Course. Sign up today!

Tips to improve your Presentation Skills

Now that you know about the importance of presentation skills in personal and professional life, we will now provide you with tips to Improve Your Presentation Skills .

1) Know your audience: Understand the demographics and interests of your audience to tailor your Presentation accordingly.

2) Practice regularly: Rehearse your speech multiple times to refine content and delivery.

3) Seek feedback: Gather feedback from peers or mentors to identify areas for improvement.

4) Manage nervousness: Use relaxation techniques to overcome nervousness before presenting.

5) Engage with eye contact: Maintain eye contact with the audience to establish a connection.

6) Use clear visuals: Utilise impactful visuals to complement your spoken words.

7) Emphasise key points: Highlight important information to enhance audience retention.

8) Employ body language: Use confident and purposeful gestures to convey your message.

9) Handle Q&A confidently: Prepare for potential questions and answer them with clarity.

10) Add personal stories: Include relevant anecdotes to make your Presentation more relatable.

All in all, Presentation skills are a valuable asset, impacting both personal and professional realms of life. By mastering these skills, you can become a more effective communicator, a confident professional, and a persuasive influencer. Continuous improvement and adaptation to technological advancements will ensure you stay ahead in this competitive world.

Want to master the art of impactful Presentations? Explore our Presentation Skills Courses and elevate your communication prowess!

Frequently Asked Questions

Upcoming business skills resources batches & dates.

Fri 7th Jun 2024

Fri 5th Jul 2024

Fri 2nd Aug 2024

Fri 6th Sep 2024

Fri 4th Oct 2024

Fri 1st Nov 2024

Fri 6th Dec 2024

Get A Quote

WHO WILL BE FUNDING THE COURSE?

My employer

By submitting your details you agree to be contacted in order to respond to your enquiry

- Business Analysis

- Lean Six Sigma Certification

Share this course

Our biggest spring sale.

We cannot process your enquiry without contacting you, please tick to confirm your consent to us for contacting you about your enquiry.

By submitting your details you agree to be contacted in order to respond to your enquiry.

We may not have the course you’re looking for. If you enquire or give us a call on 01344203999 and speak to our training experts, we may still be able to help with your training requirements.

Or select from our popular topics

- ITIL® Certification

- Scrum Certification

- Change Management Certification

- Business Analysis Courses

- Microsoft Azure Certification

- Microsoft Excel Courses

- Microsoft Project

- Explore more courses

Press esc to close

Fill out your contact details below and our training experts will be in touch.

Fill out your contact details below

Thank you for your enquiry!

One of our training experts will be in touch shortly to go over your training requirements.

Back to Course Information

Fill out your contact details below so we can get in touch with you regarding your training requirements.

* WHO WILL BE FUNDING THE COURSE?

Preferred Contact Method

No preference

Back to course information

Fill out your training details below

Fill out your training details below so we have a better idea of what your training requirements are.

HOW MANY DELEGATES NEED TRAINING?

HOW DO YOU WANT THE COURSE DELIVERED?

Online Instructor-led

Online Self-paced

WHEN WOULD YOU LIKE TO TAKE THIS COURSE?

Next 2 - 4 months

WHAT IS YOUR REASON FOR ENQUIRING?

Looking for some information

Looking for a discount

I want to book but have questions

One of our training experts will be in touch shortly to go overy your training requirements.

Your privacy & cookies!

Like many websites we use cookies. We care about your data and experience, so to give you the best possible experience using our site, we store a very limited amount of your data. Continuing to use this site or clicking “Accept & close” means that you agree to our use of cookies. Learn more about our privacy policy and cookie policy cookie policy .

We use cookies that are essential for our site to work. Please visit our cookie policy for more information. To accept all cookies click 'Accept & close'.

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- How to prepare and...

How to prepare and deliver an effective oral presentation

- Related content

- Peer review

- Lucia Hartigan , registrar 1 ,

- Fionnuala Mone , fellow in maternal fetal medicine 1 ,

- Mary Higgins , consultant obstetrician 2

- 1 National Maternity Hospital, Dublin, Ireland

- 2 National Maternity Hospital, Dublin; Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Medicine and Medical Sciences, University College Dublin

- luciahartigan{at}hotmail.com

The success of an oral presentation lies in the speaker’s ability to transmit information to the audience. Lucia Hartigan and colleagues describe what they have learnt about delivering an effective scientific oral presentation from their own experiences, and their mistakes

The objective of an oral presentation is to portray large amounts of often complex information in a clear, bite sized fashion. Although some of the success lies in the content, the rest lies in the speaker’s skills in transmitting the information to the audience. 1

Preparation

It is important to be as well prepared as possible. Look at the venue in person, and find out the time allowed for your presentation and for questions, and the size of the audience and their backgrounds, which will allow the presentation to be pitched at the appropriate level.

See what the ambience and temperature are like and check that the format of your presentation is compatible with the available computer. This is particularly important when embedding videos. Before you begin, look at the video on stand-by and make sure the lights are dimmed and the speakers are functioning.

For visual aids, Microsoft PowerPoint or Apple Mac Keynote programmes are usual, although Prezi is increasing in popularity. Save the presentation on a USB stick, with email or cloud storage backup to avoid last minute disasters.

When preparing the presentation, start with an opening slide containing the title of the study, your name, and the date. Begin by addressing and thanking the audience and the organisation that has invited you to speak. Typically, the format includes background, study aims, methodology, results, strengths and weaknesses of the study, and conclusions.

If the study takes a lecturing format, consider including “any questions?” on a slide before you conclude, which will allow the audience to remember the take home messages. Ideally, the audience should remember three of the main points from the presentation. 2

Have a maximum of four short points per slide. If you can display something as a diagram, video, or a graph, use this instead of text and talk around it.

Animation is available in both Microsoft PowerPoint and the Apple Mac Keynote programme, and its use in presentations has been demonstrated to assist in the retention and recall of facts. 3 Do not overuse it, though, as it could make you appear unprofessional. If you show a video or diagram don’t just sit back—use a laser pointer to explain what is happening.

Rehearse your presentation in front of at least one person. Request feedback and amend accordingly. If possible, practise in the venue itself so things will not be unfamiliar on the day. If you appear comfortable, the audience will feel comfortable. Ask colleagues and seniors what questions they would ask and prepare responses to these questions.

It is important to dress appropriately, stand up straight, and project your voice towards the back of the room. Practise using a microphone, or any other presentation aids, in advance. If you don’t have your own presenting style, think of the style of inspirational scientific speakers you have seen and imitate it.

Try to present slides at the rate of around one slide a minute. If you talk too much, you will lose your audience’s attention. The slides or videos should be an adjunct to your presentation, so do not hide behind them, and be proud of the work you are presenting. You should avoid reading the wording on the slides, but instead talk around the content on them.

Maintain eye contact with the audience and remember to smile and pause after each comment, giving your nerves time to settle. Speak slowly and concisely, highlighting key points.

Do not assume that the audience is completely familiar with the topic you are passionate about, but don’t patronise them either. Use every presentation as an opportunity to teach, even your seniors. The information you are presenting may be new to them, but it is always important to know your audience’s background. You can then ensure you do not patronise world experts.

To maintain the audience’s attention, vary the tone and inflection of your voice. If appropriate, use humour, though you should run any comments or jokes past others beforehand and make sure they are culturally appropriate. Check every now and again that the audience is following and offer them the opportunity to ask questions.

Finishing up is the most important part, as this is when you send your take home message with the audience. Slow down, even though time is important at this stage. Conclude with the three key points from the study and leave the slide up for a further few seconds. Do not ramble on. Give the audience a chance to digest the presentation. Conclude by acknowledging those who assisted you in the study, and thank the audience and organisation. If you are presenting in North America, it is usual practice to conclude with an image of the team. If you wish to show references, insert a text box on the appropriate slide with the primary author, year, and paper, although this is not always required.

Answering questions can often feel like the most daunting part, but don’t look upon this as negative. Assume that the audience has listened and is interested in your research. Listen carefully, and if you are unsure about what someone is saying, ask for the question to be rephrased. Thank the audience member for asking the question and keep responses brief and concise. If you are unsure of the answer you can say that the questioner has raised an interesting point that you will have to investigate further. Have someone in the audience who will write down the questions for you, and remember that this is effectively free peer review.

Be proud of your achievements and try to do justice to the work that you and the rest of your group have done. You deserve to be up on that stage, so show off what you have achieved.

Competing interests: We have read and understood the BMJ Group policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: None.

- ↵ Rovira A, Auger C, Naidich TP. How to prepare an oral presentation and a conference. Radiologica 2013 ; 55 (suppl 1): 2 -7S. OpenUrl

- ↵ Bourne PE. Ten simple rules for making good oral presentations. PLos Comput Biol 2007 ; 3 : e77 . OpenUrl PubMed

- ↵ Naqvi SH, Mobasher F, Afzal MA, Umair M, Kohli AN, Bukhari MH. Effectiveness of teaching methods in a medical institute: perceptions of medical students to teaching aids. J Pak Med Assoc 2013 ; 63 : 859 -64. OpenUrl

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

What It Takes to Give a Great Presentation

- Carmine Gallo

Five tips to set yourself apart.

Never underestimate the power of great communication. It can help you land the job of your dreams, attract investors to back your idea, or elevate your stature within your organization. But while there are plenty of good speakers in the world, you can set yourself apart out by being the person who can deliver something great over and over. Here are a few tips for business professionals who want to move from being good speakers to great ones: be concise (the fewer words, the better); never use bullet points (photos and images paired together are more memorable); don’t underestimate the power of your voice (raise and lower it for emphasis); give your audience something extra (unexpected moments will grab their attention); rehearse (the best speakers are the best because they practice — a lot).

I was sitting across the table from a Silicon Valley CEO who had pioneered a technology that touches many of our lives — the flash memory that stores data on smartphones, digital cameras, and computers. He was a frequent guest on CNBC and had been delivering business presentations for at least 20 years before we met. And yet, the CEO wanted to sharpen his public speaking skills.

- Carmine Gallo is a Harvard University instructor, keynote speaker, and author of 10 books translated into 40 languages. Gallo is the author of The Bezos Blueprint: Communication Secrets of the World’s Greatest Salesman (St. Martin’s Press).

Partner Center

- Career Blog

Presentation Skills for Career Success: Examples and Tips

As an expert in both writing and subject matter, I understand the importance of effective presentation skills. From delivering a sales pitch to making a dynamic presentation at a conference, presentation skills are an essential aspect of career success.

Definition of Presentation Skills

Presentation skills refer to the ability to effectively and persuasively communicate information to an audience. This involves several different components, including speaking clearly and confidently, engaging with the audience, and using visual aids to illustrate key points.

Importance of Presentation Skills for Career Success

Strong presentation skills can make all the difference in achieving success in your career. Whether you’re pitching an important idea to investors or delivering a report to your team, being able to communicate your message clearly and effectively is critical. Poor presentation skills can undermine a person’s credibility and ultimately hinder their ability to succeed.

Understanding Your Target Audience

When preparing a presentation, it is crucial to understand your target audience. Without knowing who will be sitting in the audience, it can be challenging to effectively communicate your message. To ensure a successful presentation, you need to:

A. Identifying Your Audience

The first step is to identify your audience. Who are you presenting to? Are they co-workers, executives or customers? What is their demographic? What is their level of knowledge about your topic? Understanding your audience’s characteristics will allow you to personalize the presentation and make it more relatable.

B. Knowing Your Audience’s Expectations

After identifying your audience, the next step is to understand their expectations. What are they hoping to learn from your presentation? Are they looking for specific information, or are they coming in with no prior knowledge? By understanding what your audience expects, you can tailor your message accordingly.

C. Tailoring Your Presentation to Your Audience

Now that you understand who your audience is and what they expect to gain from your presentation, the final step is to tailor your presentation to meet their needs. This means adjusting the way you present information, including visuals and language, to ensure that the message resonates with them.

For example, if you’re presenting to a group of executives, you’ll want to use language that speaks to their level of knowledge and experience. On the other hand, if you’re presenting to a group of new employees, you’ll want to simplify your language and provide more background information.

By customizing your presentation to your audience, you will increase their engagement and enhance their understanding of the topic. This will result in a more successful presentation overall.

Understanding your target audience is crucial to delivering a successful presentation. By identifying your audience, knowing their expectations, and tailoring your message to their needs, you can create a presentation that resonates with your audience and delivers the message effectively.

Creating an Effective Presentation

Creating an effective presentation can be a daunting task, but it is necessary for career success. An effective presentation can be the key to closing a business deal, securing new clients, or impressing your bosses.

To make sure your presentation is effective, there are five key steps you must take: defining your objectives, developing a strong message, structuring your presentation, using visual aids and emotional appeals, and rehearsing your presentation.

A. Defining Your Objectives

Before you start creating your presentation, it is important to define your objectives. Ask yourself: What am I trying to achieve with this presentation? Who is my audience? What message do I want to convey? Once you have answered these questions, you can start creating your presentation with a clear goal in mind.

B. Developing a Strong Message

To create a strong message, you need to think about what your audience needs to hear from you. Your message should be clear, concise, and relevant to your audience. Use language and visuals that are easy to understand and memorable.

C. Structuring Your Presentation

A well-structured presentation is key to keeping your audience engaged. Start with a strong opening that grabs their attention, then move into the main body of your presentation where you can delve deeper into your message using clear examples and evidence. Finally, end with a strong closing that leaves a lasting impression.

D. Using Visual Aids and Emotional Appeals

Using visual aids and emotional appeals can make your presentation more engaging and memorable. Visual aids can help illustrate your message and make it easier to understand. Emotional appeals can help you connect with your audience on a more personal level and make your presentation more memorable.

E. Rehearsing Your Presentation

The final step in creating an effective presentation is rehearsing. Practice your presentation multiple times. This will help you feel more confident and prepared when it is time to present. It will also help you identify areas that need improvement.

Creating an effective presentation is an important skill for career success. By defining your objectives, developing a strong message, structuring your presentation, using visual aids and emotional appeals, and rehearsing your presentation, you can deliver a presentation that is engaging, memorable, and effective.

Presentation Delivery Skills

Effective presentation delivery is a crucial aspect for professional success. The way you present yourself, the ideas, and the subject matter can significantly impact the audience’s perception of you and the content you provide. This section discusses some important presentation delivery skills that can help you in your career.

A. Opening and Closing Strategies

The opening and closing of your presentation should be attention-grabbing and leave a lasting impression. Use a powerful opening statement, a thought-provoking question, or an engaging story that relates to the topic. Similarly, end the presentation with a summarized version of the crucial points, a call to action, or an inspiring quote. These strategies can help the audience remember your presentation long after it’s over.

B. Voice and Body Language

Your voice and body language play an essential role in conveying your message effectively. Speak clearly and confidently, and avoid filler words such as “umm” and “ahh.” Use gestures and body movements that complement your words and help emphasize your message.

C. Eye Contact and Interpersonal Communication

Maintaining eye contact with your audience is a powerful way to build rapport and influence. It shows that you are confident and interested in engaging with them. Along with eye contact, focus on interpersonal communication skills, such as active listening, empathy, and adapting your communication style to resonate with the audience.

D. Managing Nervousness

It’s natural to feel nervous before a presentation, but it can negatively affect your performance. Be prepared by rehearsing beforehand, arriving early, and taking deep breaths. Use positive self-talk, affirmations, and visualization techniques to calm your nerves and build confidence.

E. Tips for Virtual and Remote Presentations

Virtual and remote presentations require additional considerations to ensure a successful delivery. Ensure that your technology works correctly, keep your slides simple and easy to read, and avoid multitasking during the presentation. Practice your presentation in front of a camera to get used to the virtual interface.

Mastering presentation delivery skills is an ongoing process of refinement and practice. Paying attention to your opening and closing strategies, voice and body language, eye contact and interpersonal communication, managing nervousness, and tips for virtual and remote presentations can make a significant difference in the impact of your presentation on the audience. By honing these skills, you can enhance your professional brand and take your career to greater heights.

Engaging Your Audience

Engaging your audience is crucial to delivering an effective presentation. The goal is to keep their attention and leave a lasting impression. In this section, we’ll cover four key techniques to engage your audience: storytelling, audience participation, Q&A sessions, and handling difficult audience members.

A. Using Storytelling Techniques

Stories have the power to captivate an audience and make your presentation memorable. Consider opening with a personal anecdote or sharing a relevant story that connects with your topic. Use descriptive language and vivid details to make your story come alive.

Throughout your presentation, sprinkle in relevant stories and examples to help illustrate your points. If you have data or statistics to share, try presenting them in the form of a story. This will make them more interesting and easier to remember.

B. Encouraging Audience Participation

Encouraging audience participation can help to create an interactive and engaging presentation. There are many ways to do this, such as posing thought-provoking questions or inviting volunteers for a demonstration.

Another way to encourage participation is to use interactive tools, such as live polling or Q&A features. These tools allow the audience to engage with you in real-time and can provide valuable insights into their thoughts and opinions.

C. Asking Questions and Managing Q&A Sessions

Asking questions can be an effective way to keep your audience engaged and test their understanding of the material. Be sure to pause at key points in your presentation and ask relevant questions to keep the audience on their toes.

During the Q&A session, it’s important to manage the flow of questions and keep things organized. Encourage people to raise their hands and wait until they are called upon before speaking. If you’re receiving multiple questions at once, try repeating them back to ensure everyone can hear and understand.

D. Tips for Handling Difficult Audience Members

Dealing with difficult audience members can be a challenge, but it’s important to remain professional and respectful. Here are a few tips for handling different types of difficult audience members:

- The interrupter: Politely ask them to wait until you’ve finished speaking before asking their question.

- The skeptic: Acknowledge their concerns and be prepared with evidence or examples to support your position.

- The distractor: Politely redirect their attention back to the topic at hand and keep the presentation moving forward.

Engaging your audience is crucial to delivering an effective presentation. By using storytelling techniques, encouraging audience participation, asking questions, and handling difficult audience members, you can create a memorable and impactful presentation that resonates with your audience.

Presentation Software and Tools

In today’s professional environment, creating and delivering powerful presentations is a requirement for success. Fortunately, there are many tools and technologies available to help presenters bring their ideas to life. This section explores some of the most popular software and techniques for creating and delivering engaging presentations.

A. Overview of Popular Presentation Software

There are many presentation software tools available, but some are more widely used than others. The most popular presentation software tools include:

- Microsoft PowerPoint – A versatile software tool that allows users to create dynamic presentations with a range of text, graphics, and multimedia features.

- Apple Keynote – An alternative to PowerPoint that includes many of the same features and is optimized for use on Apple devices.

- Google Slides – A cloud-based alternative to PowerPoint that allows users to create and share presentations online.

- Prezi – A non-linear presentation tool that uses a canvas rather than slides to tell a story.

B. Techniques for Using PowerPoint Effectively

PowerPoint is a widely used presentation software tool, but there are some key techniques that can be used to present more effectively. Some of these techniques include:

- Simplicity – Avoid cluttering slides with too much content. Keep text to a minimum and use images and graphics to emphasize key points.

- Consistency – Use a consistent font, color scheme, and style throughout the presentation to create a professional-looking deck.

- Storytelling – Use a clear narrative to guide the audience through the presentation and keep them engaged.

- Animation – Use animations and other visual effects sparingly to emphasize key points and keep the audience’s attention.

C. Tips for Creating Engaging Multimedia

Engaging multimedia elements can help bring a presentation to life and make it more memorable. Some tips for creating engaging multimedia include:

- Images – Use high-quality images that are relevant to the topic and can help illustrate key points.

- Graphs and charts – Use graphs and charts to display data in a clear and concise way.

- Video – Include relevant video clips to emphasize key points and break up the presentation.

- Interactive elements – Use interactive elements such as quizzes or polls to engage the audience and encourage participation.

D. Other Presentation Tools and Technologies

In addition to the software tools and techniques mentioned above, there are many other presentation tools and technologies that can be used to make a presentation more engaging. Some of these include:

- Virtual and augmented reality – Virtual and augmented reality can be used to create immersive experiences for the audience and help them better understand complex concepts.

- Audience response systems – Audience response systems allow the audience to participate in the presentation by responding to questions or providing feedback.

- Live streaming – Live streaming allows the presentation to be broadcast online in real-time, allowing a wider audience to view the presentation.

Presentation Skills in Professional Settings

Delivering effective presentations is a crucial skill for career success. In professional settings, presentations are an opportunity to showcase expertise, make persuasive arguments, and establish credibility. Below are some common types of presentations and tips for delivering them successfully.

A. Interview Presentations

Job interviews often include a presentation component, where candidates are asked to deliver a pitch about themselves and their qualifications. To make a strong impression in an interview presentation, consider the following tips:

- Research the company and its values to tailor your message accordingly.

- Practice your presentation in advance and anticipate potential questions or points of discussion.

- Use storytelling techniques to make your presentation engaging and memorable.

- Be confident, enthusiastic, and energetic to convey your passion for the job and demonstrate your communication skills.

B. Business Proposals

In business settings, proposals are often used to pitch new ideas, products, or services to potential clients or stakeholders. To create a persuasive proposal presentation, consider the following tips:

- Understand the needs and interests of your audience to tailor your proposal accordingly.

- Use a clear and concise format that highlights the key benefits and value of your proposal.

- Anticipate potential objections or concerns and address them proactively in your presentation.

- Use visual aids or demonstrations to support your proposal and make it more engaging.

C. Sales Presentations

Sales presentations are a common way to promote products, services, or solutions to potential customers. To make an effective sales presentation, consider the following tips:

- Focus on the needs and pain points of your target audience, and position your product as a solution.

- Use storytelling techniques or case studies to illustrate the benefits and value of your product.

- Be confident and assertive, but also empathetic and responsive to your audience’s feedback and questions.

- Use visual aids or demos to showcase your product in action and make it more tangible.

D. Conference Presentations

Conference presentations are a chance to share research, insights, or expertise with a broader audience. To make a compelling conference presentation, consider the following tips:

- Identify the main message or takeaway of your presentation and structure your content accordingly.

- Use a clear and engaging narrative or story arc to make your presentation more cohesive and memorable.

- Use visual aids or multimedia to support your main points and make your presentation more engaging.

- Rehearse your delivery and timing to ensure that you stay within the allotted time and maintain a good pace.

E. Other Professional Settings

There are many other professional settings where presentation skills can be valuable, such as meetings, training sessions, or public speaking events. To deliver effective presentations in these settings, consider the following tips:

- Understand the purpose and scope of your presentation, and tailor your content and delivery accordingly.

- Use visual aids or other interactive elements to support your presentation and make it more engaging.

- Anticipate potential objections or questions and prepare to respond effectively.

Excellence in Public Speaking and Presentation Skills

Public speaking and presentation skills play a significant role in career success. To achieve excellence in these skills, one needs to develop strategies for growth, continuously work on improving them, and stay current with future trends.

A. Strategies for Growth

Developing strategies for growth involves setting goals and working towards achieving them. Here are some tips for building a strong foundation:

- Identify your audience – Know who you are presenting to and what their goals and interests are.

- Craft a compelling message – Create a clear message that resonates with your audience.

- Practice regularly – Practice speaking and presenting regularly, either in front of a mirror or in front of others.

- Seek feedback – Seek feedback from colleagues or mentors to identify areas for improvement.

B. Tips for Continuous Improvement

Once you have established good strategies, the next step to excellence is to continually work on improving your skills. Here are some tips for continuous improvement:

- Attend workshops or training sessions – Attend workshops or training sessions on public speaking and presentation skills to learn new techniques and best practices.

- Take advantage of technology – Utilize technology to enhance your presentations, such as incorporating multimedia or using presentation software.

- Analyze successful presentations – Analyze successful presentations from others and learn from their techniques.

- Embrace constructive criticism – Listen to feedback from audience members or colleagues and use it to make improvements.

C. Future Trends in Presentation Skills

As technology continues to advance, there are several future trends in presentation skills that professionals should stay current with, such as:

- Interactive presentations – Interactive presentations engage the audience through the use of technology, such as live polling or virtual reality.

- Storytelling – Storytelling is becoming increasingly popular in presentations, as it allows the presenter to connect with the audience on a more personal level.

- Personalization – Personalization involves tailoring the presentation to the individual needs of the audience, such as incorporating their names or organization’s branding.

- Artificial Intelligence – Artificial intelligence is being used to analyze and provide feedback on presentation skills, allowing presenters to make more data-driven improvements.

To achieve excellence in public speaking and presentation skills, individuals need to invest in building a strong foundation, continuously work on improving their skills, and stay current with future trends. By doing so, professionals can enhance their career success and influence their audience to take meaningful action.

Examples of Effective Presentations

A. sample presentation outlines.

Sample presentation outlines are included to give readers an idea of how presentations can be structured. These outlines may include the following sections:

- Introduction

- Main Points

- Supporting Details

- Call to Action

By following these outlines, presenters can organize their ideas and deliver a clear and concise message to their audience.

B. Video Examples of Effective Presentations

Video examples of effective presentations allow readers to see real-life examples of presenters who excel at delivering engaging and informative presentations. These videos may feature live presentations, TED talks, or business pitches. By watching these videos, readers can learn from the delivery techniques, body language, and visual aids used by the presenters.

C. Analysis of What Makes Effective Presentations

In this section, the article delves deeper into what makes a presentation effective. The analysis may cover topics such as:

- Audience Engagement: An effective presentation should keep the audience engaged and interested by using interactive tools, storytelling techniques, and humor.

- Relevance: The presentation should be relevant and deliver useful information that can benefit the audience.

- Structure: Presentations should follow a logical structure and should be easy to follow, with clear transitions between topics.

- Delivery: An effective presentation requires good vocal and nonverbal communication skills, such as eye contact, posture, and tone of voice.

- Visual Aids: The use of visual aids, such as slides, videos, and infographics, can enhance the message and increase engagement.

By understanding these key elements, individuals can improve their presentation skills and build their confidence when presenting in front of an audience.

Related Articles

- Preparing for New Job Orientation: Tips and Tricks

- Event Coordinator Resume: Examples and Tips for 2023

- 22 Best Reasons for Job Exit: A Pro’s Guide for 2023

- 50 Common Interview Mistakes to Avoid in 2023

- Energy Manager Job Description, Duties, & Opportunities

Rate this article

0 / 5. Reviews: 0

More from ResumeHead

How it works

Transform your enterprise with the scalable mindsets, skills, & behavior change that drive performance.

Explore how BetterUp connects to your core business systems.

We pair AI with the latest in human-centered coaching to drive powerful, lasting learning and behavior change.

Build leaders that accelerate team performance and engagement.

Unlock performance potential at scale with AI-powered curated growth journeys.

Build resilience, well-being and agility to drive performance across your entire enterprise.

Transform your business, starting with your sales leaders.

Unlock business impact from the top with executive coaching.

Foster a culture of inclusion and belonging.

Accelerate the performance and potential of your agencies and employees.

See how innovative organizations use BetterUp to build a thriving workforce.

Discover how BetterUp measurably impacts key business outcomes for organizations like yours.

A demo is the first step to transforming your business. Meet with us to develop a plan for attaining your goals.

- What is coaching?

Learn how 1:1 coaching works, who its for, and if it's right for you.

Accelerate your personal and professional growth with the expert guidance of a BetterUp Coach.

Types of Coaching

Navigate career transitions, accelerate your professional growth, and achieve your career goals with expert coaching.

Enhance your communication skills for better personal and professional relationships, with tailored coaching that focuses on your needs.

Find balance, resilience, and well-being in all areas of your life with holistic coaching designed to empower you.

Discover your perfect match : Take our 5-minute assessment and let us pair you with one of our top Coaches tailored just for you.

Research, expert insights, and resources to develop courageous leaders within your organization.

Best practices, research, and tools to fuel individual and business growth.

View on-demand BetterUp events and learn about upcoming live discussions.

The latest insights and ideas for building a high-performing workplace.

- BetterUp Briefing

The online magazine that helps you understand tomorrow's workforce trends, today.

Innovative research featured in peer-reviewed journals, press, and more.

Founded in 2022 to deepen the understanding of the intersection of well-being, purpose, and performance

We're on a mission to help everyone live with clarity, purpose, and passion.

Join us and create impactful change.

Read the buzz about BetterUp.

Meet the leadership that's passionate about empowering your workforce.

For Business

For Individuals

6 presentation skills and how to improve them

Jump to section

What are presentation skills?

The importance of presentation skills, 6 presentation skills examples, how to improve presentation skills.

Tips for dealing with presentation anxiety

Learn how to captivate an audience with ease

Capturing an audience’s attention takes practice.

Over time, great presenters learn how to organize their speeches and captivate an audience from start to finish. They spark curiosity, know how to read a room , and understand what their audience needs to walk away feeling like they learned something valuable.

Regardless of your profession, you most likely use presentation skills on a monthly or even weekly basis. Maybe you lead brainstorming sessions or host client calls.

Developing effective presentation skills makes it easier to contribute ideas with confidence and show others you’re someone to trust. Although speaking in front of a crowd sometimes brings nerves and anxiety , it also sparks new opportunities.

Presentation skills are the qualities and abilities you need to communicate ideas effectively and deliver a compelling speech. They influence how you structure a presentation and how an audience receives it. Understanding body language , creating impactful visual aids, and projecting your voice all fall under this umbrella.

A great presentation depends on more than what you say. It’s about how you say it. Storytelling , stage presence, and voice projection all shape how well you express your ideas and connect with the audience. These skills do take practice, but they’re worth developing — especially if public speaking makes you nervous.

Engaging a crowd isn’t easy. You may feel anxious to step in front of an audience and have all eyes and ears on you.

But feeling that anxiety doesn’t mean your ideas aren’t worth sharing. Whether you’re giving an inspiring speech or delivering a monthly recap at work, your audience is there to listen to you. Harness that nervous energy and turn it into progress.

Strong presentation skills make it easier to convey your thoughts to audiences of all sizes. They can help you tell a compelling story, convince people of a pitch , or teach a group something entirely new to them. And when it comes to the workplace, the strength of your presentation skills could play a part in getting a promotion or contributing to a new initiative.

To fully understand the impact these skills have on creating a successful presentation, it’s helpful to look at each one individually. Here are six valuable skills you can develop:

1. Active listening

Active listening is an excellent communication skill for any professional to hone. When you have strong active listening skills, you can listen to others effectively and observe their nonverbal cues . This helps you assess whether or not your audience members are engaged in and understand what you’re sharing.

Great public speakers use active listening to assess the audience’s reactions and adjust their speech if they find it lacks impact. Signs like slouching, negative facial expressions, and roaming eye contact are all signs to watch out for when giving a presentation.

2. Body language

If you’re researching presentation skills, chances are you’ve already watched a few notable speeches like TED Talks or industry seminars. And one thing you probably noticed is that speakers can capture attention with their body language.

A mixture of eye contact, hand gestures , and purposeful pacing makes a presentation more interesting and engaging. If you stand in one spot and don’t move your body, the audience might zone out.

3. Stage presence

A great stage presence looks different for everyone. A comedian might aim for more movement and excitement, and a conference speaker might focus their energy on the content of their speech. Although neither is better than the other, both understand their strengths and their audience’s needs.

Developing a stage presence involves finding your own unique communication style . Lean into your strengths, whether that’s adding an injection of humor or asking questions to make it interactive . To give a great presentation, you might even incorporate relevant props or presentation slides.

4. Storytelling

According to Forbes, audiences typically pay attention for about 10 minutes before tuning out . But you can lengthen their attention span by offering a presentation that interests them for longer. Include a narrative they’ll want to listen to, and tell a story as you go along.

Shaping your content to follow a clear narrative can spark your audience’s curiosity and entice them to pay careful attention. You can use anecdotes from your personal or professional life that take your audience along through relevant moments. If you’re pitching a product, you can start with a problem and lead your audience through the stages of how your product provides a solution.

5. Voice projection

Although this skill may be obvious, you need your audience to hear what you’re saying. This can be challenging if you’re naturally soft-spoken and struggle to project your voice.

Remember to straighten your posture and take deep breaths before speaking, which will help you speak louder and fill the room. If you’re talking into a microphone or participating in a virtual meeting, you can use your regular conversational voice, but you still want to sound confident and self-assured with a strong tone.

If you’re unsure whether everyone can hear you, you can always ask the audience at the beginning of your speech and wait for confirmation. That way, they won’t have to potentially interrupt you later.

Ensuring everyone can hear you also includes your speed and annunciation. It’s easy to speak quickly when nervous, but try to slow down and pronounce every word. Mumbling can make your presentation difficult to understand and pay attention to.

6. Verbal communication

Although verbal communication involves your projection and tone, it also covers the language and pacing you use to get your point across. This includes where you choose to place pauses in your speech or the tone you use to emphasize important ideas.

If you’re giving a presentation on collaboration in the workplace , you might start your speech by saying, “There’s something every workplace needs to succeed: teamwork.” By placing emphasis on the word “ teamwork ,” you give your audience a hint on what ideas will follow.

To further connect with your audience through diction, pay careful attention to who you’re speaking to. The way you talk to your colleagues might be different from how you speak to a group of superiors, even if you’re discussing the same subject. You might use more humor and a conversational tone for the former and more serious, formal diction for the latter.

Everyone has strengths and weaknesses when it comes to presenting. Maybe you’re confident in your use of body language, but your voice projection needs work. Maybe you’re a great storyteller in small group settings, but need to work on your stage presence in front of larger crowds.

The first step to improving presentation skills is pinpointing your gaps and determining which qualities to build upon first. Here are four tips for enhancing your presentation skills:

1. Build self-confidence

Confident people know how to speak with authority and share their ideas. Although feeling good about your presentation skills is easier said than done, building confidence is key to helping your audience believe in what you’re saying. Try practicing positive self-talk and continuously researching your topic's ins and outs.

If you don’t feel confident on the inside, fake it until you make it. Stand up straight, project your voice, and try your best to appear engaged and excited. Chances are, the audience doesn’t know you’re unsure of your skills — and they don’t need to.

Another tip is to lean into your slideshow, if you’re using one. Create something colorful and interesting so the audience’s eyes fall there instead of on you. And when you feel proud of your slideshow, you’ll be more eager to share it with others, bringing more energy to your presentation.

2. Watch other presentations

Developing the soft skills necessary for a good presentation can be challenging without seeing them in action. Watch as many as possible to become more familiar with public speaking skills and what makes a great presentation. You could attend events with keynote speakers or view past speeches on similar topics online.

Take a close look at how those presenters use verbal communication and body language to engage their audiences. Grab a notebook and jot down what you enjoyed and your main takeaways. Try to recall the techniques they used to emphasize their main points, whether they used pauses effectively, had interesting visual aids, or told a fascinating story.

3. Get in front of a crowd

You don’t need a large auditorium to practice public speaking. There are dozens of other ways to feel confident and develop good presentation skills.

If you’re a natural comedian, consider joining a small stand-up comedy club. If you’re an avid writer, participate in a public poetry reading. Even music and acting can help you feel more comfortable in front of a crowd.

If you’d rather keep it professional, you can still work on your presentation skills in the office. Challenge yourself to participate at least once in every team meeting, or plan and present a project to become more comfortable vocalizing your ideas. You could also speak to your manager about opportunities that flex your public speaking abilities.

4. Overcome fear

Many people experience feelings of fear before presenting in front of an audience, whether those feelings appear as a few butterflies or more severe anxiety. Try grounding yourself to shift your focus to the present moment. If you’re stuck dwelling on previous experiences that didn’t go well, use those mistakes as learning experiences and focus on what you can improve to do better in the future.

Tips for dealing with presentation anxiety

It’s normal to feel nervous when sharing your ideas. In fact, according to a report from the Journal of Graduate Medical Education, public speaking anxiety is prevalent in 15–30% of the general population .

Even though having a fear of public speaking is common, it doesn’t make it easier. You might feel overwhelmed, become stiff, and forget what you were going to say. But although the moment might scare you, there are ways to overcome the fear and put mind over matter.

Use these tactics to reduce your stress when you have to make a presentation:

1. Practice breathing techniques

If you experience anxiety often, you’re probably familiar with breathing techniques for stress relief . Incorporating these exercises into your daily routine can help you stop worrying and regulate anxious feelings.

Before a big presentation, take a moment alone to practice breathing techniques, ground yourself, and reduce tension. It’s also a good idea to take breaths throughout the presentation to speak slower and calm yourself down .

2. Get organized

The more organized you are, the more prepared you’ll feel. Carefully outline all of the critical information you want to use in your presentation, including your main talking points and visual aids, so you don’t forget anything. Use bullet points and visuals on each slide to remind you of what you want to talk about, and create handheld notes to help you stay on track.

3. Embrace moments of silence

It’s okay to lose your train of thought. It happens to even the most experienced public speakers once in a while. If your mind goes blank, don’t panic. Take a moment to breathe, gather your thoughts, and refer to your notes to see where you left off. You can drink some water or make a quick joke to ease the silence or regain your footing. And it’s okay to say, “Give me a moment while I find my notes.” Chances are, people understand the position you’re in.

4. Practice makes progress

Before presenting, rehearse in front of friends and family members you trust. This gives you the chance to work out any weak spots in your speech and become comfortable communicating out loud. If you want to go the extra mile, ask your makeshift audience to ask a surprise question. This tests your on-the-spot thinking and will prove that you can keep cool when things come up.

Whether you’re new to public speaking or are a seasoned presenter, you’re bound to make a few slip-ups. It happens to everyone. The most important thing is that you try your best, brush things off, and work on improving your skills to do better in your next presentation.

Although your job may require a different level of public speaking than your favorite TED Talk , developing presentation skills is handy in any profession. You can use presentation skills in a wide range of tasks in the workplace, whether you’re sharing your ideas with colleagues, expressing concerns to higher-ups, or pitching strategies to potential clients.

Remember to use active listening to read the room and engage your audience with an interesting narrative. Don’t forget to step outside your comfort zone once in a while and put your skills to practice in front of a crowd. After facing your fears, you’ll feel confident enough to put presentation skills on your resume.

If you’re trying to build your skills and become a better employee overall, try a communications coach with BetterUp.

Elevate your communication skills

Unlock the power of clear and persuasive communication. Our coaches can guide you to build strong relationships and succeed in both personal and professional life.

Elizabeth Perry, ACC

Elizabeth Perry is a Coach Community Manager at BetterUp. She uses strategic engagement strategies to cultivate a learning community across a global network of Coaches through in-person and virtual experiences, technology-enabled platforms, and strategic coaching industry partnerships. With over 3 years of coaching experience and a certification in transformative leadership and life coaching from Sofia University, Elizabeth leverages transpersonal psychology expertise to help coaches and clients gain awareness of their behavioral and thought patterns, discover their purpose and passions, and elevate their potential. She is a lifelong student of psychology, personal growth, and human potential as well as an ICF-certified ACC transpersonal life and leadership Coach.

The 11 tips that will improve your public speaking skills

The importance of good speech: 5 tips to be more articulate, learn types of gestures and their meanings to improve your communication, show gratitude with “thank you for your leadership and vision” message examples, why it's good to have a bff at work and how to find one, why we need to reframe potential into readiness, what is a career path definition, examples, and steps for paving yours, goal-setting theory: why it’s important, and how to use it at work, love them or hate them, meetings promote social learning and growth, similar articles, how to write a speech that your audience remembers, 8 tip to improve your public speaking skills, impression management: developing your self-presentation skills, 30 presentation feedback examples, your guide to what storytelling is and how to be a good storyteller, how to give a good presentation that captivates any audience, 8 clever hooks for presentations (with tips), how to make a presentation interactive and exciting, stay connected with betterup, get our newsletter, event invites, plus product insights and research..

3100 E 5th Street, Suite 350 Austin, TX 78702

- Platform Overview

- Integrations

- Powered by AI

- BetterUp Lead

- BetterUp Manage™

- BetterUp Care™

- Sales Performance

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Case Studies

- Why BetterUp?

- About Coaching

- Find your Coach

- Career Coaching

- Communication Coaching

- Life Coaching

- News and Press

- Leadership Team

- Become a BetterUp Coach

- BetterUp Labs

- Center for Purpose & Performance

- Leadership Training

- Business Coaching

- Contact Support

- Contact Sales

- Privacy Policy

- Acceptable Use Policy

- Trust & Security

- Cookie Preferences

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

14.3: Importance of Oral Presentations

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 83686

- Arley Cruthers

- Kwantlen Polytechnic University

In the workplace, and during your university career, you will likely be asked to give oral presentations. An oral presentation is a key persuasive tool. If you work in marketing, for example, you will often be asked to “pitch” campaigns to clients. Even though these pitches could happen over email, the face-to-face element allows marketers to connect with the client, respond to questions, demonstrate their knowledge and bring their ideas to life through storytelling.

In this section, we’ll focus on public speaking. While this section focuses on public speaking advocacy, you can bring these tools to everything from a meeting where you’re telling your colleagues about the results of a project to a keynote speech at a conference.

Imagine your favourite public speaker. When Meggie (one of the authors of this section) imagines a memorable speaker, she often thinks of her high school English teacher, Mrs. Permeswaran. You may be skeptical of her choice, but Mrs. Permeswaran captured the students’ attention daily. How? By providing information through stories and examples that felt relatable, reasonable, and relevant. Even with a room of students, Meggie often felt that the English teacher was just talking to her . Students worked hard, too, to listen, using note-taking and subtle nods (or confused eyebrows) to communicate that they cared about what was being said.

Now imagine your favourite public speaker. Who comes to mind? A famous comedian like Jen Kirkman? An ac

tivist like Laverne Cox? Perhaps you picture Barack Obama. What makes them memorable for you? Were they funny? Relatable? Dynamic? Confident? Try to think beyond what they said to how they made you feel . What they said certainly matters, but we are often less inclined to remember the what without a powerful how — how they delivered their message; how their performance implicated us or called us in; how they made us feel or how they asked us to think or act differently.

In this chapter, we provide an introduction to public speaking by exploring what it is and why it’s impactful as a communication process. Specifically, we invite you to consider public speaking as a type of advocacy. When you select information to share with others, you are advocating for the necessity of that information to be heard. You are calling on the audience and calling them in to listen to your perspective. Even the English teacher above was advocating that sentence structure and proper writing were important ideas to integrate. She was a trusted speaker, too, given her credibility.

Before we continue our conversation around advocacy, let’s first start with a brief definition of public speaking.

This page has been archived and is no longer updated

Effective Oral Presentations