Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

Definition and Introduction

Journal article analysis assignments require you to summarize and critically assess the quality of an empirical research study published in a scholarly [a.k.a., academic, peer-reviewed] journal. The article may be assigned by the professor, chosen from course readings listed in the syllabus, or you must locate an article on your own, usually with the requirement that you search using a reputable library database, such as, JSTOR or ProQuest . The article chosen is expected to relate to the overall discipline of the course, specific course content, or key concepts discussed in class. In some cases, the purpose of the assignment is to analyze an article that is part of the literature review for a future research project.

Analysis of an article can be assigned to students individually or as part of a small group project. The final product is usually in the form of a short paper [typically 1- 6 double-spaced pages] that addresses key questions the professor uses to guide your analysis or that assesses specific parts of a scholarly research study [e.g., the research problem, methodology, discussion, conclusions or findings]. The analysis paper may be shared on a digital course management platform and/or presented to the class for the purpose of promoting a wider discussion about the topic of the study. Although assigned in any level of undergraduate and graduate coursework in the social and behavioral sciences, professors frequently include this assignment in upper division courses to help students learn how to effectively identify, read, and analyze empirical research within their major.

Franco, Josue. “Introducing the Analysis of Journal Articles.” Prepared for presentation at the American Political Science Association’s 2020 Teaching and Learning Conference, February 7-9, 2020, Albuquerque, New Mexico; Sego, Sandra A. and Anne E. Stuart. "Learning to Read Empirical Articles in General Psychology." Teaching of Psychology 43 (2016): 38-42; Kershaw, Trina C., Jordan P. Lippman, and Jennifer Fugate. "Practice Makes Proficient: Teaching Undergraduate Students to Understand Published Research." Instructional Science 46 (2018): 921-946; Woodward-Kron, Robyn. "Critical Analysis and the Journal Article Review Assignment." Prospect 18 (August 2003): 20-36; MacMillan, Margy and Allison MacKenzie. "Strategies for Integrating Information Literacy and Academic Literacy: Helping Undergraduate Students make the most of Scholarly Articles." Library Management 33 (2012): 525-535.

Benefits of Journal Article Analysis Assignments

Analyzing and synthesizing a scholarly journal article is intended to help students obtain the reading and critical thinking skills needed to develop and write their own research papers. This assignment also supports workplace skills where you could be asked to summarize a report or other type of document and report it, for example, during a staff meeting or for a presentation.

There are two broadly defined ways that analyzing a scholarly journal article supports student learning:

Improve Reading Skills

Conducting research requires an ability to review, evaluate, and synthesize prior research studies. Reading prior research requires an understanding of the academic writing style , the type of epistemological beliefs or practices underpinning the research design, and the specific vocabulary and technical terminology [i.e., jargon] used within a discipline. Reading scholarly articles is important because academic writing is unfamiliar to most students; they have had limited exposure to using peer-reviewed journal articles prior to entering college or students have yet to gain exposure to the specific academic writing style of their disciplinary major. Learning how to read scholarly articles also requires careful and deliberate concentration on how authors use specific language and phrasing to convey their research, the problem it addresses, its relationship to prior research, its significance, its limitations, and how authors connect methods of data gathering to the results so as to develop recommended solutions derived from the overall research process.

Improve Comprehension Skills

In addition to knowing how to read scholarly journals articles, students must learn how to effectively interpret what the scholar(s) are trying to convey. Academic writing can be dense, multi-layered, and non-linear in how information is presented. In addition, scholarly articles contain footnotes or endnotes, references to sources, multiple appendices, and, in some cases, non-textual elements [e.g., graphs, charts] that can break-up the reader’s experience with the narrative flow of the study. Analyzing articles helps students practice comprehending these elements of writing, critiquing the arguments being made, reflecting upon the significance of the research, and how it relates to building new knowledge and understanding or applying new approaches to practice. Comprehending scholarly writing also involves thinking critically about where you fit within the overall dialogue among scholars concerning the research problem, finding possible gaps in the research that require further analysis, or identifying where the author(s) has failed to examine fully any specific elements of the study.

In addition, journal article analysis assignments are used by professors to strengthen discipline-specific information literacy skills, either alone or in relation to other tasks, such as, giving a class presentation or participating in a group project. These benefits can include the ability to:

- Effectively paraphrase text, which leads to a more thorough understanding of the overall study;

- Identify and describe strengths and weaknesses of the study and their implications;

- Relate the article to other course readings and in relation to particular research concepts or ideas discussed during class;

- Think critically about the research and summarize complex ideas contained within;

- Plan, organize, and write an effective inquiry-based paper that investigates a research study, evaluates evidence, expounds on the author’s main ideas, and presents an argument concerning the significance and impact of the research in a clear and concise manner;

- Model the type of source summary and critique you should do for any college-level research paper; and,

- Increase interest and engagement with the research problem of the study as well as with the discipline.

Kershaw, Trina C., Jennifer Fugate, and Aminda J. O'Hare. "Teaching Undergraduates to Understand Published Research through Structured Practice in Identifying Key Research Concepts." Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology . Advance online publication, 2020; Franco, Josue. “Introducing the Analysis of Journal Articles.” Prepared for presentation at the American Political Science Association’s 2020 Teaching and Learning Conference, February 7-9, 2020, Albuquerque, New Mexico; Sego, Sandra A. and Anne E. Stuart. "Learning to Read Empirical Articles in General Psychology." Teaching of Psychology 43 (2016): 38-42; Woodward-Kron, Robyn. "Critical Analysis and the Journal Article Review Assignment." Prospect 18 (August 2003): 20-36; MacMillan, Margy and Allison MacKenzie. "Strategies for Integrating Information Literacy and Academic Literacy: Helping Undergraduate Students make the most of Scholarly Articles." Library Management 33 (2012): 525-535; Kershaw, Trina C., Jordan P. Lippman, and Jennifer Fugate. "Practice Makes Proficient: Teaching Undergraduate Students to Understand Published Research." Instructional Science 46 (2018): 921-946.

Structure and Organization

A journal article analysis paper should be written in paragraph format and include an instruction to the study, your analysis of the research, and a conclusion that provides an overall assessment of the author's work, along with an explanation of what you believe is the study's overall impact and significance. Unless the purpose of the assignment is to examine foundational studies published many years ago, you should select articles that have been published relatively recently [e.g., within the past few years].

Since the research has been completed, reference to the study in your paper should be written in the past tense, with your analysis stated in the present tense [e.g., “The author portrayed access to health care services in rural areas as primarily a problem of having reliable transportation. However, I believe the author is overgeneralizing this issue because...”].

Introduction Section

The first section of a journal analysis paper should describe the topic of the article and highlight the author’s main points. This includes describing the research problem and theoretical framework, the rationale for the research, the methods of data gathering and analysis, the key findings, and the author’s final conclusions and recommendations. The narrative should focus on the act of describing rather than analyzing. Think of the introduction as a more comprehensive and detailed descriptive abstract of the study.

Possible questions to help guide your writing of the introduction section may include:

- Who are the authors and what credentials do they hold that contributes to the validity of the study?

- What was the research problem being investigated?

- What type of research design was used to investigate the research problem?

- What theoretical idea(s) and/or research questions were used to address the problem?

- What was the source of the data or information used as evidence for analysis?

- What methods were applied to investigate this evidence?

- What were the author's overall conclusions and key findings?

Critical Analysis Section

The second section of a journal analysis paper should describe the strengths and weaknesses of the study and analyze its significance and impact. This section is where you shift the narrative from describing to analyzing. Think critically about the research in relation to other course readings, what has been discussed in class, or based on your own life experiences. If you are struggling to identify any weaknesses, explain why you believe this to be true. However, no study is perfect, regardless of how laudable its design may be. Given this, think about the repercussions of the choices made by the author(s) and how you might have conducted the study differently. Examples can include contemplating the choice of what sources were included or excluded in support of examining the research problem, the choice of the method used to analyze the data, or the choice to highlight specific recommended courses of action and/or implications for practice over others. Another strategy is to place yourself within the research study itself by thinking reflectively about what may be missing if you had been a participant in the study or if the recommended courses of action specifically targeted you or your community.

Possible questions to help guide your writing of the analysis section may include:

Introduction

- Did the author clearly state the problem being investigated?

- What was your reaction to and perspective on the research problem?

- Was the study’s objective clearly stated? Did the author clearly explain why the study was necessary?

- How well did the introduction frame the scope of the study?

- Did the introduction conclude with a clear purpose statement?

Literature Review

- Did the literature review lay a foundation for understanding the significance of the research problem?

- Did the literature review provide enough background information to understand the problem in relation to relevant contexts [e.g., historical, economic, social, cultural, etc.].

- Did literature review effectively place the study within the domain of prior research? Is anything missing?

- Was the literature review organized by conceptual categories or did the author simply list and describe sources?

- Did the author accurately explain how the data or information were collected?

- Was the data used sufficient in supporting the study of the research problem?

- Was there another methodological approach that could have been more illuminating?

- Give your overall evaluation of the methods used in this article. How much trust would you put in generating relevant findings?

Results and Discussion

- Were the results clearly presented?

- Did you feel that the results support the theoretical and interpretive claims of the author? Why?

- What did the author(s) do especially well in describing or analyzing their results?

- Was the author's evaluation of the findings clearly stated?

- How well did the discussion of the results relate to what is already known about the research problem?

- Was the discussion of the results free of repetition and redundancies?

- What interpretations did the authors make that you think are in incomplete, unwarranted, or overstated?

- Did the conclusion effectively capture the main points of study?

- Did the conclusion address the research questions posed? Do they seem reasonable?

- Were the author’s conclusions consistent with the evidence and arguments presented?

- Has the author explained how the research added new knowledge or understanding?

Overall Writing Style

- If the article included tables, figures, or other non-textual elements, did they contribute to understanding the study?

- Were ideas developed and related in a logical sequence?

- Were transitions between sections of the article smooth and easy to follow?

Overall Evaluation Section

The final section of a journal analysis paper should bring your thoughts together into a coherent assessment of the value of the research study . This section is where the narrative flow transitions from analyzing specific elements of the article to critically evaluating the overall study. Explain what you view as the significance of the research in relation to the overall course content and any relevant discussions that occurred during class. Think about how the article contributes to understanding the overall research problem, how it fits within existing literature on the topic, how it relates to the course, and what it means to you as a student researcher. In some cases, your professor will also ask you to describe your experiences writing the journal article analysis paper as part of a reflective learning exercise.

Possible questions to help guide your writing of the conclusion and evaluation section may include:

- Was the structure of the article clear and well organized?

- Was the topic of current or enduring interest to you?

- What were the main weaknesses of the article? [this does not refer to limitations stated by the author, but what you believe are potential flaws]

- Was any of the information in the article unclear or ambiguous?

- What did you learn from the research? If nothing stood out to you, explain why.

- Assess the originality of the research. Did you believe it contributed new understanding of the research problem?

- Were you persuaded by the author’s arguments?

- If the author made any final recommendations, will they be impactful if applied to practice?

- In what ways could future research build off of this study?

- What implications does the study have for daily life?

- Was the use of non-textual elements, footnotes or endnotes, and/or appendices helpful in understanding the research?

- What lingering questions do you have after analyzing the article?

NOTE: Avoid using quotes. One of the main purposes of writing an article analysis paper is to learn how to effectively paraphrase and use your own words to summarize a scholarly research study and to explain what the research means to you. Using and citing a direct quote from the article should only be done to help emphasize a key point or to underscore an important concept or idea.

Business: The Article Analysis . Fred Meijer Center for Writing, Grand Valley State University; Bachiochi, Peter et al. "Using Empirical Article Analysis to Assess Research Methods Courses." Teaching of Psychology 38 (2011): 5-9; Brosowsky, Nicholaus P. et al. “Teaching Undergraduate Students to Read Empirical Articles: An Evaluation and Revision of the QALMRI Method.” PsyArXi Preprints , 2020; Holster, Kristin. “Article Evaluation Assignment”. TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovations Library for Sociology . Washington DC: American Sociological Association, 2016; Kershaw, Trina C., Jennifer Fugate, and Aminda J. O'Hare. "Teaching Undergraduates to Understand Published Research through Structured Practice in Identifying Key Research Concepts." Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology . Advance online publication, 2020; Franco, Josue. “Introducing the Analysis of Journal Articles.” Prepared for presentation at the American Political Science Association’s 2020 Teaching and Learning Conference, February 7-9, 2020, Albuquerque, New Mexico; Reviewer's Guide . SAGE Reviewer Gateway, SAGE Journals; Sego, Sandra A. and Anne E. Stuart. "Learning to Read Empirical Articles in General Psychology." Teaching of Psychology 43 (2016): 38-42; Kershaw, Trina C., Jordan P. Lippman, and Jennifer Fugate. "Practice Makes Proficient: Teaching Undergraduate Students to Understand Published Research." Instructional Science 46 (2018): 921-946; Gyuris, Emma, and Laura Castell. "To Tell Them or Show Them? How to Improve Science Students’ Skills of Critical Reading." International Journal of Innovation in Science and Mathematics Education 21 (2013): 70-80; Woodward-Kron, Robyn. "Critical Analysis and the Journal Article Review Assignment." Prospect 18 (August 2003): 20-36; MacMillan, Margy and Allison MacKenzie. "Strategies for Integrating Information Literacy and Academic Literacy: Helping Undergraduate Students Make the Most of Scholarly Articles." Library Management 33 (2012): 525-535.

Writing Tip

Not All Scholarly Journal Articles Can Be Critically Analyzed

There are a variety of articles published in scholarly journals that do not fit within the guidelines of an article analysis assignment. This is because the work cannot be empirically examined or it does not generate new knowledge in a way which can be critically analyzed.

If you are required to locate a research study on your own, avoid selecting these types of journal articles:

- Theoretical essays which discuss concepts, assumptions, and propositions, but report no empirical research;

- Statistical or methodological papers that may analyze data, but the bulk of the work is devoted to refining a new measurement, statistical technique, or modeling procedure;

- Articles that review, analyze, critique, and synthesize prior research, but do not report any original research;

- Brief essays devoted to research methods and findings;

- Articles written by scholars in popular magazines or industry trade journals;

- Pre-print articles that have been posted online, but may undergo further editing and revision by the journal's editorial staff before final publication; and

- Academic commentary that discusses research trends or emerging concepts and ideas, but does not contain citations to sources.

Journal Analysis Assignment - Myers . Writing@CSU, Colorado State University; Franco, Josue. “Introducing the Analysis of Journal Articles.” Prepared for presentation at the American Political Science Association’s 2020 Teaching and Learning Conference, February 7-9, 2020, Albuquerque, New Mexico; Woodward-Kron, Robyn. "Critical Analysis and the Journal Article Review Assignment." Prospect 18 (August 2003): 20-36.

- << Previous: Annotated Bibliography

- Next: Giving an Oral Presentation >>

- Last Updated: May 7, 2024 9:45 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

Evaluating Information

- Understanding Primary and Secondary Sources

- Exploring and Evaluating Popular, Trade, and Scholarly Sources

Reading a Scholarly Article

Common components of original research articles, while you read, reading strategies, reading for citations, further reading, learning objectives.

This page was created to help you:

Identify the different parts of a scholarly article

Efficiently analyze and evaluate scholarly articles for usefulness

This page will focus on reading scholarly articles — published reports on original research in the social sciences, humanities, and STEM fields. Reading and understanding this type of article can be challenging. This guide will help you develop these skills, which can be learned and improved upon with practice.

We will go over:

There are many different types of articles that may be found in scholarly journals and other academic publications. For more, see:

- Types of Information Sources

Reading a scholarly article isn’t like reading a novel, website, or newspaper article. It’s likely you won’t read and absorb it from beginning to end, all at once.

Instead, think of scholarly reading as inquiry, i.e., asking a series of questions as you do your research or read for class. Your reading should be guided by your class topic or your own research question or thesis.

For example, as you read, you might ask yourself:

- What questions does it help to answer, or what topics does it address?

- Are these relevant or useful to me?

- Does the article offer a helpful framework for understanding my topic or question (theoretical framework)?

- Do the authors use interesting or innovative methods to conduct their research that might be relevant to me?

- Does the article contain references I might consult for further information?

In Practice

Scanning and skimming are essential when reading scholarly articles, especially at the beginning stages of your research or when you have a lot of material in front of you.

Many scholarly articles are organized to help you scan and skim efficiently. The next time you need to read an article, practice scanning the following sections (where available) and skim their contents:

- The abstract: This summary provides a birds’ eye view of the article contents.

- The introduction: What is the topic(s) of the research article? What is its main idea or question?

- The list of keywords or descriptors

- Methods: How did the author(s) go about answering their question/collecting their data?

- Section headings: Stop and skim those sections you may find relevant.

- Figures: Offer lots of information in quick visual format.

- The conclusion: What are the findings and/or conclusions of this article?

Mark Up Your Text

Read with purpose.

- Scanning and skimming with a pen in hand can help to focus your reading.

- Use color for quick reference. Try highlighters or some sticky notes. Use different colors to represent different topics.

- Write in the margins, putting down thoughts and questions about the content as you read.

- Use digital markup features available in eBook platforms or third-party solutions, like Adobe Reader or Hypothes.is.

Categorize Information

Create your own informal system of organization. It doesn’t have to be complicated — start basic, and be sure it works for you.

- Jot down a few of your own keywords for each article. These keywords may correspond with important topics being addressed in class or in your research paper.

- Write keywords on print copies or use the built-in note taking features in reference management tools like Zotero and EndNote.

- Your keywords and system of organization may grow more complex the deeper you get into your reading.

Highlight words, terms, phrases, acronyms, etc. that are unfamiliar to you. You can highlight on the text or make a list in a notetaking program.

- Decide if the term is essential to your understanding of the article or if you can look it up later and keep scanning.

You may scan an article and discover that it isn’t what you thought it was about. Before you close the tab or delete that PDF, consider scanning the article one more time, specifically to look for citations that might be more on-target for your topic.

You don’t need to look at every citation in the bibliography — you can look to the literature review to identify the core references that relate to your topic. Literature reviews are typically organized by subtopic within a research question or thesis. Find the paragraph or two that are closely aligned with your topic, make note of the author names, then locate those citations in the bibliography or footnote.

See the Find Articles page for what to do next:

- Find Articles

See the Citation Searching page for more on following a citation trail:

- Citation Searching

- Taking notes effectively. [blog post] Raul Pacheco-Vega, PhD

- How to read an academic paper. [video] UBCiSchool. 2013

- How to (seriously) read a scientific paper. (2016, March 21). Science | AAAS.

- How to read a paper. S. Keshav. 2007. SIGCOMM Comput. Commun. Rev. 37, 3 (July 2007), 83–84.

This guide was designed to help you:

- << Previous: Exploring and Evaluating Popular, Trade, and Scholarly Sources

- Last Updated: Feb 16, 2024 3:55 PM

- URL: https://libguides.brown.edu/evaluate

Brown University Library | Providence, RI 02912 | (401) 863-2165 | Contact | Comments | Library Feedback | Site Map

Library Intranet

How to analyze an article

Affiliation.

- 1 Department of Surgery, Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Tufts University School of Medicine, Tufts-New England Medical Center, 750 Washington Street, Boston, Massuchusetts 02111, USA. [email protected]

- PMID: 15827843

- DOI: 10.1007/s00268-005-7912-z

In clinical research investigators generalize from study samples to populations, and in evidence-based medicine practitioners apply population-level evidence to individual patients. The validity of these processes is assessed through critical appraisal of published articles. Critical appraisal is therefore a core component of evidence-based medicine (EBM). The purpose of critical appraisal is not one of criticizing for criticism's sake. Instead, it is an exercise in assigning a value to an article. A checklist approach to article appraisal is outlined, and common pitfalls of analysis are highlighted. Relevant questions are posed for each section of an article (introduction, methods, results, discussion). The approach is applicable to most clinical surgical research articles, even those of a nonrandomized nature. Issues specific to evidence-based surgical practice, in contrast to evidence-based medicine, are introduced.

- Evaluation Studies as Topic

- Evidence-Based Medicine / methods*

- Peer Review, Research

- Periodicals as Topic*

- Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

ON YOUR 1ST ORDER

How To Critically Analyse An Article – Become A Savvy Reader

By Laura Brown on 22nd September 2023

In the current academic scenario, knowing how to analyse an article critically is essential to attain stability and strength. It’s about reading between the lines, questioning what you encounter, and forming informed opinions based on evidence and sound reasoning.

- To critically analyse an article, read it thoroughly to grasp the author’s main points.

- Evaluate the evidence and arguments presented, checking for credibility and logical consistency.

- Consider the article’s structure, tone, and style while also assessing its sources.

- Formulate your critical response by synthesising your analysis and constructing a well-supported argument.

Have you ever wondered how to tell if an article is good or not? It’s important when it comes to your academic superiority. Critical analysis of an article is like being a detective. You check the article closely to see if it makes sense, if the facts are correct, and if the writer is trying to trick you.

But it’s not just something for school, college or university; it’s a superpower for everyday life. It helps you find the important stuff in an article, spot when someone is trying to persuade you and understand what the writer really thinks.

Think of it as a special skill that lets you dig deep into an article, like a treasure hunt. You uncover hidden biases, find the truth, and see how the writer tries to convince you. It’s a bit like being a detective and a wizard at the same time.

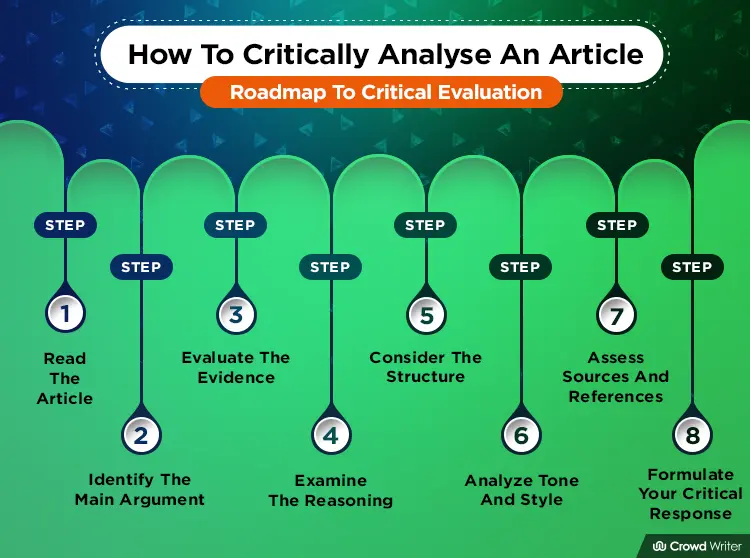

Get ready to become a smart reader. This guide will show you how to use this superpower to make sense of the information around us in just 8 simple steps.

Step 1: Read the Article

Before embarking on the journey to analyse an article critically, it is paramount to begin with the foundational step of reading the article itself. This step lays the groundwork for a comprehensive understanding of the material, enabling you to effectively evaluate its merits and demerits.

Reading an article critically starts with setting aside distractions and immersing yourself in the text. Instead of skimming through it hurriedly, take the time to read it meticulously.

To truly grasp the article’s essence, you must consider both its content and context. Content refers to the information and ideas presented within the article, while context encompasses the circumstances in which it was written.

- Why was this article written?

- Who is the intended audience?

- When was it published, and what was happening in the world at that time?

- What is the author’s background or expertise in the subject matter?

As you read, do not rely solely on your memory to retain key points and insights. Taking notes is an invaluable practice during this phase. Record significant ideas, quotes, and statistics that catch your attention.

Your initial impressions of the article can offer valuable insights into your subjective response. If a particular passage elicits a strong emotional reaction, make a note of it. Identifying your emotional responses can help you later in the analysis process when considering your own biases and reactions to the author’s arguments.

Step 2: Identify the Main Argument

While you are up to critically analyse an article, pinpointing the central argument is akin to finding the North Star guiding you through the article’s content. Every well-crafted article should possess a clear and concise main argument or thesis, which serves as the nucleus of the author’s message. Typically situated in the article’s introduction or abstract , this argument not only encapsulates the author’s viewpoint but also functions as a roadmap for the reader, outlining what to expect in the subsequent sections.

Identifying the main argument necessitates a discerning eye. Delve into the introductory paragraphs, abstract, or the initial sections of the article to locate this pivotal statement. This argument may be explicit, explicitly stated by the author, or implicit, inferred through careful examination of the content. Once you’ve grasped the main argument, keep it at the forefront of your mind as you proceed with your analysis, it will serve as the cornerstone against which all other elements are evaluated.

Step 3: Evaluate the Evidence

In order to solely understand how to analyse an article critically, it is imperative to know that an article’s persuasive power hinges on the quality of evidence presented to substantiate its main argument. In this critical step, it’s imperative to scrutinise the evidence with a discerning eye. Look beyond the surface to assess the data, statistics, examples, and citations provided by the author. You can run it through Turnitin for a plagiarism check. These elements serve as the pillars upon which the argument stands or crumbles.

Begin by evaluating the credibility and relevance of the sources used to support the argument. Are they authoritative and trustworthy? Are they current and pertinent to the subject matter? Assess the quality of evidence by considering the reliability of the data, the objectivity of the sources, and the breadth of examples. Moreover, consider the quantity of evidence; is there enough to convincingly underpin the thesis, or does it appear lacking or selective? A well-supported argument should be built upon a solid foundation of robust evidence.

Step 4: Examine the Reasoning

Critical analysis doesn’t stop at identifying the argument and assessing the evidence; it extends to examining the underlying reasoning that connects these elements. In this step, delve deeper into the author’s logic and the structure of the argument. The goal is to identify any logical fallacies or weak assumptions that might undermine the article’s credibility.

Scrutinise the coherence and consistency of the author’s reasoning. Are there any gaps in the argument, or does it flow logically from point to point? Identify any potential biases, emotional appeals, or rhetorical strategies employed by the author. Assess whether the argument is grounded in sound principles and reasoning.

Be on the lookout for flawed deductive or inductive reasoning, and question whether the evidence truly supports the conclusions drawn . Critical thinking is pivotal here, as it allows you to gauge the strength of the article’s argumentation and identify areas where it may be lacking or vulnerable to critique.

Step 5: Consider the Structure

The structure of an article is not merely a cosmetic feature but a fundamental aspect that can profoundly influence its overall effectiveness in conveying its message. A well-organised article possesses the power to captivate readers, enhance comprehension, and amplify its impact. To harness this power effectively, it’s crucial to pay close attention to various structural elements.

- Headings and Subheadings: Examine headings and subheadings to understand the article’s structure and main themes.

- Transitions Between Sections: Observe how transitions between sections maintain or disrupt the flow of ideas.

- Logical Progression: Assess if the article logically builds upon concepts or feels disjointed.

- Use of Visual Aids: Evaluate the integration and effectiveness of visual aids like graphs and charts.

- Paragraph Organisation: Analyse paragraph structure, including clear topic sentences.

- Conclusion and Summary: Review the conclusion for a strong reiteration of the main argument and key takeaways.

In essence, the structure of an article serves as the blueprint that shapes the reader’s journey. A thoughtfully organised article not only makes it easier for readers to navigate the content but also enhances their overall comprehension and retention. By paying attention to these structural elements, you can gain a deeper understanding of the author’s message and how it is effectively conveyed to the audience.

Step 6: Analyse Tone and Style

Exploring the tone and style of an article is like deciphering the author’s hidden intentions and underlying biases. It involves looking closely at how the author has crafted their words, examining their choice of language, tone, and use of rhetorical devices . Is the tone even-handed and impartial, or can you detect signs of favouritism or prejudice? Understanding the author’s perspective in this way allows you to place their argument within a broader context, helping you see beyond the surface of the text.

When you analyse tone, consider whether the author’s language carries any emotional weight. Are they using words that evoke strong feelings, or do they maintain an objective and rational tone throughout? Furthermore, observe how the author addresses counterarguments. Are they respectful and considerate, or do they employ ad hominem attacks? Evaluating tone and style can offer valuable insights into the author’s intentions and their ability to construct a persuasive argument.

Step 7: Assess Sources and References

A critical analysis wouldn’t be complete without examining the sources and references cited within the article. These citations form the foundation upon which the author’s arguments rest. To assess the credibility of the author’s research, it’s essential to scrutinise the origins of these sources. Are they drawn from reputable, well-established journals, books, or widely recognised and trusted websites? High-quality sources reflect positively on the author’s research and strengthen the overall validity of the argument.

While staying on the journey of how to critically analyse an article, be vigilant when encountering articles that heavily rely on sources that might be considered unreliable or biased. Investigate whether the author has balanced their sources and considered diverse perspectives. A well-researched article should draw upon a variety of reputable sources to provide a well-rounded view of the topic. By assessing the sources and references, you can gauge the robustness of the author’s supporting evidence.

Step 8: Formulate Your Critical Response

Having navigated through the previous steps, it’s now your turn to construct a critical response to the article. This step involves summarising your analysis by identifying the strengths and weaknesses within the article. Do you find yourself in agreement with the main argument, or do you have reservations? Highlight the evidence that you found compelling and areas where you believe the article falls short. Your critical response serves as a valuable contribution to the ongoing discourse surrounding the topic, adding your unique perspective to the conversation. Remember that constructive criticism can lead to deeper understanding and improved future discourse.

Now, let’s be specific on two of the most analysed articles, i.e. research articles and journal articles.

How To Critically Analyse A Research Article?

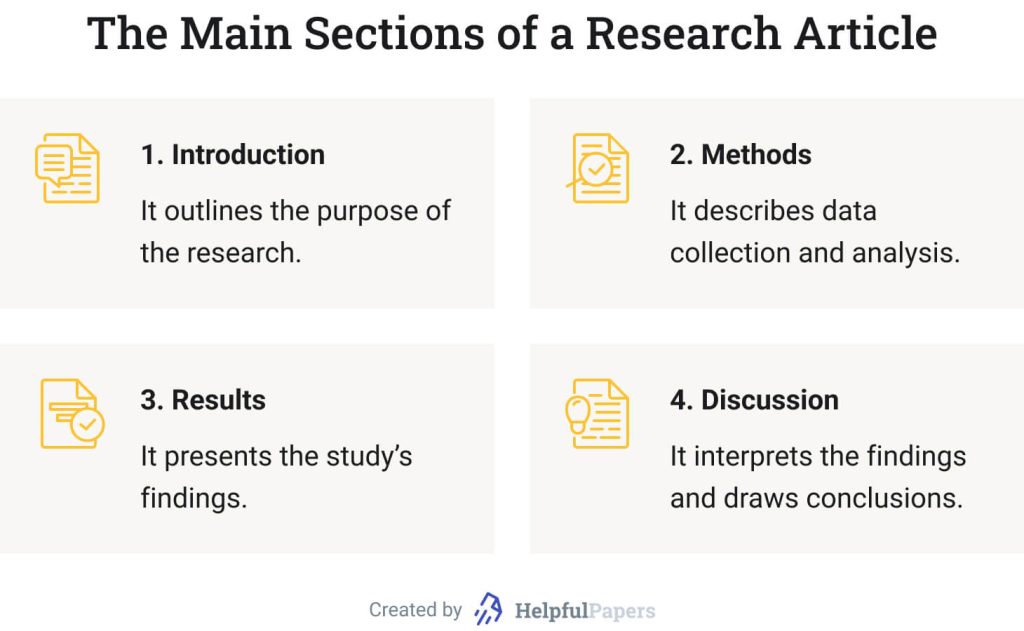

A research article is a scholarly document that presents the findings of original research conducted by the author(s) and is typically published in academic journals. It follows a structured format, including sections such as an abstract, introduction, methods, results, discussion, and references. To critically analyse a research article, you may go through the following six steps.

- Scrutinise the research question’s clarity and significance.

- Examine the appropriateness of research methods.

- Assess sample quality and data reliability.

- Evaluate the accuracy and significance of results.

- Review the discussion for supported conclusions.

- Check references for relevant and high-quality sources.

Never hesitate to ask our customer support for examples and relevant guides as you face any challenges while critically analysing a research paper .

How To Critically Analyse A Journal Article?

A journal article is a scholarly publication that presents research findings, analyses, or discussions within a specific academic or scientific field. These articles typically follow a structured format and are subject to peer review before publication. In order to critically analyse a journal article, take the following steps.

- Evaluate the article’s clarity and relevance.

- Examine the research methods and their suitability.

- Assess the credibility of data and sources.

- Scrutinise the presentation of results.

- Analyse the conclusions drawn.

- Consider the quality of references and citations.

If you have any difficulty conducting a good critical analysis, you can always ask our research paper service for help and relevant examples.

Concluding Upon How To Analyse An Article Critically

Mastering the art of analysing an article critically is a valuable skill that empowers you to navigate the vast sea of information with confidence. By following these eight steps, you can dissect articles effectively, separating reliable information from biased or poorly supported claims. Remember, critical analysis is not about tearing an article apart but understanding it deeply and thoughtfully. With practice, you’ll become a more discerning and informed reader, researcher, or student.

Laura Brown, a senior content writer who writes actionable blogs at Crowd Writer.

Writing a Critical Analysis

What is in this guide, definitions, putting it together, tips and examples of critques.

- Background Information

- Cite Sources

Library Links

- Ask a Librarian

- Library Tutorials

- The Research Process

- Library Hours

- Online Databases (A-Z)

- Interlibrary Loan (ILL)

- Reserve a Study Room

- Report a Problem

This guide is meant to help you understand the basics of writing a critical analysis. A critical analysis is an argument about a particular piece of media. There are typically two parts: (1) identify and explain the argument the author is making, and (2), provide your own argument about that argument. Your instructor may have very specific requirements on how you are to write your critical analysis, so make sure you read your assignment carefully.

Critical Analysis

A deep approach to your understanding of a piece of media by relating new knowledge to what you already know.

Part 1: Introduction

- Identify the work being criticized.

- Present thesis - argument about the work.

- Preview your argument - what are the steps you will take to prove your argument.

Part 2: Summarize

- Provide a short summary of the work.

- Present only what is needed to know to understand your argument.

Part 3: Your Argument

- This is the bulk of your paper.

- Provide "sub-arguments" to prove your main argument.

- Use scholarly articles to back up your argument(s).

Part 4: Conclusion

- Reflect on how you have proven your argument.

- Point out the importance of your argument.

- Comment on the potential for further research or analysis.

- Cornell University Library Tips for writing a critical appraisal and analysis of a scholarly article.

- Queen's University Library How to Critique an Article (Psychology)

- University of Illinois, Springfield An example of a summary and an evaluation of a research article. This extended example shows the different ways a student can critique and write about an article

- Next: Background Information >>

- Last Updated: Feb 14, 2024 4:33 PM

- URL: https://libguides.pittcc.edu/critical_analysis

Research Paper Analysis: How to Analyze a Research Article + Example

Why might you need to analyze research? First of all, when you analyze a research article, you begin to understand your assigned reading better. It is also the first step toward learning how to write your own research articles and literature reviews. However, if you have never written a research paper before, it may be difficult for you to analyze one. After all, you may not know what criteria to use to evaluate it. But don’t panic! We will help you figure it out!

In this article, our team has explained how to analyze research papers quickly and effectively. At the end, you will also find a research analysis paper example to see how everything works in practice.

- 🔤 Research Analysis Definition

📊 How to Analyze a Research Article

✍️ how to write a research analysis.

- 📝 Analysis Example

- 🔎 More Examples

🔗 References

🔤 research paper analysis: what is it.

A research paper analysis is an academic writing assignment in which you analyze a scholarly article’s methodology, data, and findings. In essence, “to analyze” means to break something down into components and assess each of them individually and in relation to each other. The goal of an analysis is to gain a deeper understanding of a subject. So, when you analyze a research article, you dissect it into elements like data sources , research methods, and results and evaluate how they contribute to the study’s strengths and weaknesses.

📋 Research Analysis Format

A research analysis paper has a pretty straightforward structure. Check it out below!

Research articles usually include the following sections: introduction, methods, results, and discussion. In the following paragraphs, we will discuss how to analyze a scientific article with a focus on each of its parts.

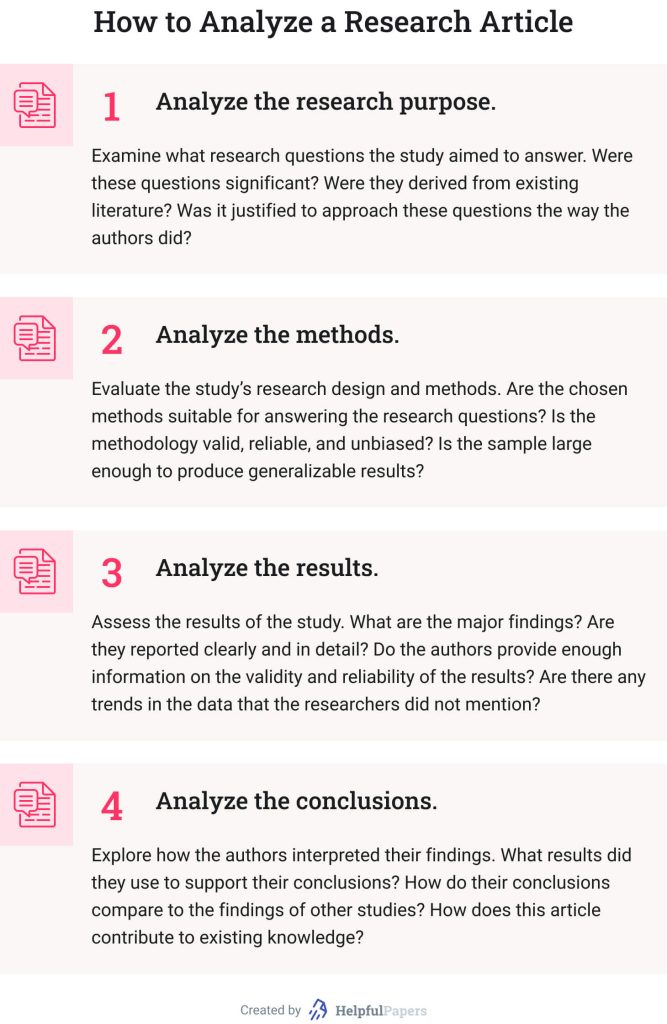

How to Analyze a Research Paper: Purpose

The purpose of the study is usually outlined in the introductory section of the article. Analyzing the research paper’s objectives is critical to establish the context for the rest of your analysis.

When analyzing the research aim, you should evaluate whether it was justified for the researchers to conduct the study. In other words, you should assess whether their research question was significant and whether it arose from existing literature on the topic.

Here are some questions that may help you analyze a research paper’s purpose:

- Why was the research carried out?

- What gaps does it try to fill, or what controversies to settle?

- How does the study contribute to its field?

- Do you agree with the author’s justification for approaching this particular question in this way?

How to Analyze a Paper: Methods

When analyzing the methodology section , you should indicate the study’s research design (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed) and methods used (for example, experiment, case study, correlational research, survey, etc.). After that, you should assess whether these methods suit the research purpose. In other words, do the chosen methods allow scholars to answer their research questions within the scope of their study?

For example, if scholars wanted to study US students’ average satisfaction with their higher education experience, they could conduct a quantitative survey . However, if they wanted to gain an in-depth understanding of the factors influencing US students’ satisfaction with higher education, qualitative interviews would be more appropriate.

When analyzing methods, you should also look at the research sample . Did the scholars use randomization to select study participants? Was the sample big enough for the results to be generalizable to a larger population?

You can also answer the following questions in your methodology analysis:

- Is the methodology valid? In other words, did the researchers use methods that accurately measure the variables of interest?

- Is the research methodology reliable? A research method is reliable if it can produce stable and consistent results under the same circumstances.

- Is the study biased in any way?

- What are the limitations of the chosen methodology?

How to Analyze Research Articles’ Results

You should start the analysis of the article results by carefully reading the tables, figures, and text. Check whether the findings correspond to the initial research purpose. See whether the results answered the author’s research questions or supported the hypotheses stated in the introduction.

To analyze the results section effectively, answer the following questions:

- What are the major findings of the study?

- Did the author present the results clearly and unambiguously?

- Are the findings statistically significant ?

- Does the author provide sufficient information on the validity and reliability of the results?

- Have you noticed any trends or patterns in the data that the author did not mention?

How to Analyze Research: Discussion

Finally, you should analyze the authors’ interpretation of results and its connection with research objectives. Examine what conclusions the authors drew from their study and whether these conclusions answer the original question.

You should also pay attention to how the authors used findings to support their conclusions. For example, you can reflect on why their findings support that particular inference and not another one. Moreover, more than one conclusion can sometimes be made based on the same set of results. If that’s the case with your article, you should analyze whether the authors addressed other interpretations of their findings .

Here are some useful questions you can use to analyze the discussion section:

- What findings did the authors use to support their conclusions?

- How do the researchers’ conclusions compare to other studies’ findings?

- How does this study contribute to its field?

- What future research directions do the authors suggest?

- What additional insights can you share regarding this article? For example, do you agree with the results? What other questions could the researchers have answered?

Now, you know how to analyze an article that presents research findings. However, it’s just a part of the work you have to do to complete your paper. So, it’s time to learn how to write research analysis! Check out the steps below!

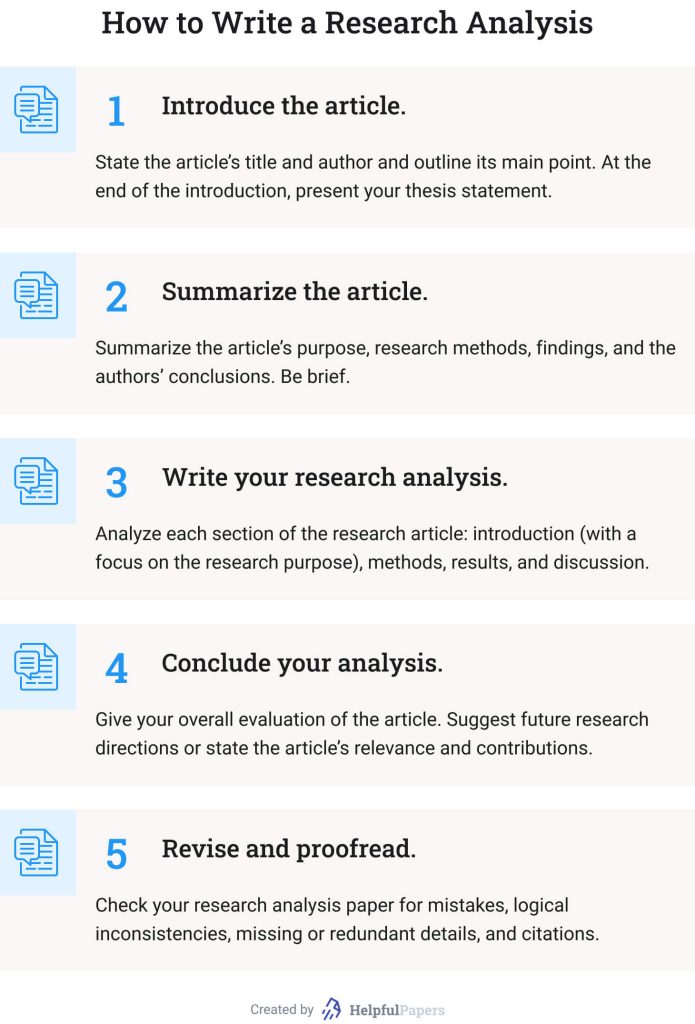

1. Introduce the Article

As with most academic assignments, you should start your research article analysis with an introduction. Here’s what it should include:

- The article’s publication details . Specify the title of the scholarly work you are analyzing, its authors, and publication date. Remember to enclose the article’s title in quotation marks and write it in title case .

- The article’s main point . State what the paper is about. What did the authors study, and what was their major finding?

- Your thesis statement . End your introduction with a strong claim summarizing your evaluation of the article. Consider briefly outlining the research paper’s strengths, weaknesses, and significance in your thesis.

Keep your introduction brief. Save the word count for the “meat” of your paper — that is, for the analysis.

2. Summarize the Article

Now, you should write a brief and focused summary of the scientific article. It should be shorter than your analysis section and contain all the relevant details about the research paper.

Here’s what you should include in your summary:

- The research purpose . Briefly explain why the research was done. Identify the authors’ purpose and research questions or hypotheses .

- Methods and results . Summarize what happened in the study. State only facts, without the authors’ interpretations of them. Avoid using too many numbers and details; instead, include only the information that will help readers understand what happened.

- The authors’ conclusions . Outline what conclusions the researchers made from their study. In other words, describe how the authors explained the meaning of their findings.

If you need help summarizing an article, you can use our free summary generator .

3. Write Your Research Analysis

The analysis of the study is the most crucial part of this assignment type. Its key goal is to evaluate the article critically and demonstrate your understanding of it.

We’ve already covered how to analyze a research article in the section above. Here’s a quick recap:

- Analyze whether the study’s purpose is significant and relevant.

- Examine whether the chosen methodology allows for answering the research questions.

- Evaluate how the authors presented the results.

- Assess whether the authors’ conclusions are grounded in findings and answer the original research questions.

Although you should analyze the article critically, it doesn’t mean you only should criticize it. If the authors did a good job designing and conducting their study, be sure to explain why you think their work is well done. Also, it is a great idea to provide examples from the article to support your analysis.

4. Conclude Your Analysis of Research Paper

A conclusion is your chance to reflect on the study’s relevance and importance. Explain how the analyzed paper can contribute to the existing knowledge or lead to future research. Also, you need to summarize your thoughts on the article as a whole. Avoid making value judgments — saying that the paper is “good” or “bad.” Instead, use more descriptive words and phrases such as “This paper effectively showed…”

Need help writing a compelling conclusion? Try our free essay conclusion generator !

5. Revise and Proofread

Last but not least, you should carefully proofread your paper to find any punctuation, grammar, and spelling mistakes. Start by reading your work out loud to ensure that your sentences fit together and sound cohesive. Also, it can be helpful to ask your professor or peer to read your work and highlight possible weaknesses or typos.

📝 Research Paper Analysis Example

We have prepared an analysis of a research paper example to show how everything works in practice.

No Homework Policy: Research Article Analysis Example

This paper aims to analyze the research article entitled “No Assignment: A Boon or a Bane?” by Cordova, Pagtulon-an, and Tan (2019). This study examined the effects of having and not having assignments on weekends on high school students’ performance and transmuted mean scores. This article effectively shows the value of homework for students, but larger studies are needed to support its findings.

Cordova et al. (2019) conducted a descriptive quantitative study using a sample of 115 Grade 11 students of the Central Mindanao University Laboratory High School in the Philippines. The sample was divided into two groups: the first received homework on weekends, while the second didn’t. The researchers compared students’ performance records made by teachers and found that students who received assignments performed better than their counterparts without homework.

The purpose of this study is highly relevant and justified as this research was conducted in response to the debates about the “No Homework Policy” in the Philippines. Although the descriptive research design used by the authors allows to answer the research question, the study could benefit from an experimental design. This way, the authors would have firm control over variables. Additionally, the study’s sample size was not large enough for the findings to be generalized to a larger population.

The study results are presented clearly, logically, and comprehensively and correspond to the research objectives. The researchers found that students’ mean grades decreased in the group without homework and increased in the group with homework. Based on these findings, the authors concluded that homework positively affected students’ performance. This conclusion is logical and grounded in data.

This research effectively showed the importance of homework for students’ performance. Yet, since the sample size was relatively small, larger studies are needed to ensure the authors’ conclusions can be generalized to a larger population.

🔎 More Research Analysis Paper Examples

Do you want another research analysis example? Check out the best analysis research paper samples below:

- Gracious Leadership Principles for Nurses: Article Analysis

- Effective Mental Health Interventions: Analysis of an Article

- Nursing Turnover: Article Analysis

- Nursing Practice Issue: Qualitative Research Article Analysis

- Quantitative Article Critique in Nursing

- LIVE Program: Quantitative Article Critique

- Evidence-Based Practice Beliefs and Implementation: Article Critique

- “Differential Effectiveness of Placebo Treatments”: Research Paper Analysis

- “Family-Based Childhood Obesity Prevention Interventions”: Analysis Research Paper Example

- “Childhood Obesity Risk in Overweight Mothers”: Article Analysis

- “Fostering Early Breast Cancer Detection” Article Analysis

- Lesson Planning for Diversity: Analysis of an Article

- Space and the Atom: Article Analysis

- “Democracy and Collective Identity in the EU and the USA”: Article Analysis

- China’s Hegemonic Prospects: Article Review

- Article Analysis: Fear of Missing Out

- Codependence, Narcissism, and Childhood Trauma: Analysis of the Article

- Relationship Between Work Intensity, Workaholism, Burnout, and MSC: Article Review

We hope that our article on research paper analysis has been helpful. If you liked it, please share this article with your friends!

- Analyzing Research Articles: A Guide for Readers and Writers | Sam Mathews

- Summary and Analysis of Scientific Research Articles | San José State University Writing Center

- Analyzing Scholarly Articles | Texas A&M University

- Article Analysis Assignment | University of Wisconsin-Madison

- How to Summarize a Research Article | University of Connecticut

- Critique/Review of Research Articles | University of Calgary

- Art of Reading a Journal Article: Methodically and Effectively | PubMed Central

- Write a Critical Review of a Scientific Journal Article | McLaughlin Library

- How to Read and Understand a Scientific Paper: A Guide for Non-scientists | LSE

- How to Analyze Journal Articles | Classroom

How to Write an Animal Testing Essay: Tips for Argumentative & Persuasive Papers

Descriptive essay topics: examples, outline, & more.

How to Critically Analyse an Article

Critical analysis refers to the skill required to evaluate an author’s work. Students are frequently asked to critically analyse a particular journal. The analysis is designed to enhance the reader’s understanding of the thesis and content of the article, and crucially is subjective, because a piece of critical analysis writing is a way for the writer to express their opinions, analysis, and evaluation of the article in question. In essence, the article needs to be broken down into parts, each one analysed separately and then brought together as one piece of critical analysis of the whole.

Key point: you need to be aware that when you are analysing an article your goal is to ensure that your readers understand the main points of the paper with ease. This means demonstrating critical thinking skills, judgement, and evaluation to illustrate how you came to your conclusions and opinions on the work. This might sound simple, and it can be, if you follow our guide to critically analyse an article:

- Before you start your essay, you should read through the paper at least three times.

- The first time ensures you understand, the second allows you to examine the structure of the work and the third enables you to pick out the key points and focus of the thesis statement given by the author (if there is one of course!). During these reads and re-reads you can set down bullet points which will eventually frame your outline and draft for the final work.

- Look for the purpose of the article – is the writer trying to inform through facts and research, are they trying to persuade through logical argument, or are they simply trying to entertain and create an emotional response. Examine your own responses to the article and this will guide to the purpose.

- When you start writing your analysis, avoid phrases such as “I think/believe”, “In my opinion”. The analysis is of the paper, not your views and perspectives.

- Ensure you have clearly indicated the subject of the article so that is evident to the reader.

- Look for both strengths and weaknesses in the work – and always support your assertions with credible, viable sources that are clearly referenced at the end of your work.

- Be open-minded and objective, rely on facts and evidence as you pull your work together.

Structure for Critical Analysis of an Article

Remember, your essay should be in three mains sections: the introduction, the main body, and a conclusion.

Introduction

Your introduction should commence by indicating the title of the work being analysed, including author and date of publication. This should be followed by an indication of the main themes in the thesis statement. Once you have provided the information about the author’s paper, you should then develop your thesis statement which sets out what you intend to achieve or prove with your critical analysis of the article.

Key point: your introduction should be short, succinct and draw your readers in. Keep it simple and concise but interesting enough to encourage further reading.

Overview of the paper

This is an important section to include when writing a critical analysis of an article because it answers the four “w’s”, of what, why, who, when and also the how. This section should include a brief overview of the key ideas in the article, along with the structure, style and dominant point of view expressed. For example,

“The focus of this article is… based on work undertaken… The main thrust of the thesis is that… which is the foundation for an argument which suggests. The conclusion from the authors is that…. However, it can be argued that…

Once you have given the overview and outline, you can then move onto the more detailed analysis.

For each point you make about the article, you should contain this in a separate paragraph. Introduce the point you wish to make, regarding what you see as a strength or weakness of the work, provide evidence for your perspective from reliable and credible sources, and indicate how the authors have achieved, or not their goal in relation to the points made. For each point, you should identify whether the paper is objective, informative, persuasive, and sufficiently unbiased. In addition, identify whether the target audience for the work has been correctly addressed, the survey instruments used are appropriate and the results are presented in a clear and concise way.

If the authors have used tables, figures or graphs do they back up the conclusions made? If not, why not? Again, back up your statements with reliable hard evidence and credible sources, fully referenced at the end of your work.

In the same way that an introduction opens up the analysis to readers, the conclusion should close it. Clearly, concisely and without the addition of any new information not included in the body paragraph.

Key points for a strong conclusion include restating your thesis statement, paraphrased, with a summary of the evidence for the accuracy of your views, combined with identification of how the article could have been improved – in other words, asking the reader to take action.

Key phrases for Critical Analysis of an article

- This article has value because it…

- There is a clear bias within this article based on the focus on…

- It appears that the assumptions made do not correlate with the information presented…

- Aspects of the work suggest that…

- The proposal is therefore that…

- The evidence presented supports the view that…

- The evidence presented however overlooks…

- Whilst the author’s view is generally accurate, it can also be indicated that…

- Closer examination suggests there is an omission in relation to

You may also like

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you’re on board with our cookie policy

- A Research Guide

- Writing Guide

- Article Writing

How to Analyze an Article

- What is an article analysis

- Outline and structure

- Step-by-step writing guide

- Article analysis format

- Analysis examples

- Article analysis template

What Is an Article Analysis?

- Summarize the main points in the piece – when you get to do an article analysis, you have to analyze the main points so that the reader can understand what the article is all about in general. The summary will be an overview of the story outline, but it is not the main analysis. It just acts to guide the reader to understand what the article is all about in brief.

- Proceed to the main argument and analyze the evidence offered by the writer in the article – this is where analysis begins because you must critique the article by analyzing the evidence given by the piece’s author. You should also point out the flaws in the work and support where it needs to be; it should not necessarily be a positive critique. You are free to pinpoint even the negative part of the story. In other words, you should not rely on one side but be truthful about what you are addressing to the satisfaction of anyone who would read your essay.

- Analyze the piece’s significance – most readers would want to see why you need to make article analysis. It is your role as a writer to emphasize the importance of the article so that the reader can be content with your writing. When your audience gets interested in your work, you will have achieved your aim because the main aim of writing is to convince the reader. The more persuasive you are, the more your article stands out. Focus on motivating your audience, and you will have scored.

Outline and Structure of an Article Analysis

What do you need to write an article analysis, how to write an analysis of an article, step 1: analyze your audience, step 2: read the article.

- The evidence : identify the evidence the writer used in the article to support their claim. While looking into the evidence, you should gauge whether the writer brings out factual evidence or it is personal judgments.

- The argument’s validity: a writer might use many pieces of evidence to support their claims, but you need to identify the sources they use and determine whether they are credible. Credible sources are like scholarly articles and books, and some are not worth relying on for research.

- How convictive are the arguments? You should be able to judge the writer’s persuasion of the audience. An article is usually informative and therefore has to be persuasive to the readers to be considered worthy. If it does not achieve this, you should be able to critique that and illustrate the same.

Step 3: Make the plan

Step 4: write a critical analysis of an article, step 5: edit your essay, article analysis format, article analysis example, what didn’t you know about the article analysis template.

- Read through the piece quickly to get an overview.

- Look for confronting words in the article and note them down.

- Read the piece for the second time while summarizing major points in the literature piece.

- Reflect on the paper’s thesis to affirm and adhere to it in your writing.

- Note the arguments and the evidence used.

- Evaluate the article and focus on your audience.

- Give your opinion and support it to the satisfaction of your audience.

Receive paper in 3 Hours!

- Choose the number of pages.

- Select your deadline.

- Complete your order.

Number of Pages

550 words (double spaced)

Deadline: 10 days left

By clicking "Log In", you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We'll occasionally send you account related and promo emails.

Sign Up for your FREE account

Critically Analyzing Information Sources: Critical Appraisal and Analysis

- Critical Appraisal and Analysis

Initial Appraisal : Reviewing the source

- What are the author's credentials--institutional affiliation (where he or she works), educational background, past writings, or experience? Is the book or article written on a topic in the author's area of expertise? You can use the various Who's Who publications for the U.S. and other countries and for specific subjects and the biographical information located in the publication itself to help determine the author's affiliation and credentials.

- Has your instructor mentioned this author? Have you seen the author's name cited in other sources or bibliographies? Respected authors are cited frequently by other scholars. For this reason, always note those names that appear in many different sources.

- Is the author associated with a reputable institution or organization? What are the basic values or goals of the organization or institution?

B. Date of Publication

- When was the source published? This date is often located on the face of the title page below the name of the publisher. If it is not there, look for the copyright date on the reverse of the title page. On Web pages, the date of the last revision is usually at the bottom of the home page, sometimes every page.

- Is the source current or out-of-date for your topic? Topic areas of continuing and rapid development, such as the sciences, demand more current information. On the other hand, topics in the humanities often require material that was written many years ago. At the other extreme, some news sources on the Web now note the hour and minute that articles are posted on their site.

C. Edition or Revision

Is this a first edition of this publication or not? Further editions indicate a source has been revised and updated to reflect changes in knowledge, include omissions, and harmonize with its intended reader's needs. Also, many printings or editions may indicate that the work has become a standard source in the area and is reliable. If you are using a Web source, do the pages indicate revision dates?

D. Publisher

Note the publisher. If the source is published by a university press, it is likely to be scholarly. Although the fact that the publisher is reputable does not necessarily guarantee quality, it does show that the publisher may have high regard for the source being published.

E. Title of Journal

Is this a scholarly or a popular journal? This distinction is important because it indicates different levels of complexity in conveying ideas. If you need help in determining the type of journal, see Distinguishing Scholarly from Non-Scholarly Periodicals . Or you may wish to check your journal title in the latest edition of Katz's Magazines for Libraries (Olin Reference Z 6941 .K21, shelved at the reference desk) for a brief evaluative description.

Critical Analysis of the Content

Having made an initial appraisal, you should now examine the body of the source. Read the preface to determine the author's intentions for the book. Scan the table of contents and the index to get a broad overview of the material it covers. Note whether bibliographies are included. Read the chapters that specifically address your topic. Reading the article abstract and scanning the table of contents of a journal or magazine issue is also useful. As with books, the presence and quality of a bibliography at the end of the article may reflect the care with which the authors have prepared their work.

A. Intended Audience

What type of audience is the author addressing? Is the publication aimed at a specialized or a general audience? Is this source too elementary, too technical, too advanced, or just right for your needs?

B. Objective Reasoning

- Is the information covered fact, opinion, or propaganda? It is not always easy to separate fact from opinion. Facts can usually be verified; opinions, though they may be based on factual information, evolve from the interpretation of facts. Skilled writers can make you think their interpretations are facts.

- Does the information appear to be valid and well-researched, or is it questionable and unsupported by evidence? Assumptions should be reasonable. Note errors or omissions.

- Are the ideas and arguments advanced more or less in line with other works you have read on the same topic? The more radically an author departs from the views of others in the same field, the more carefully and critically you should scrutinize his or her ideas.

- Is the author's point of view objective and impartial? Is the language free of emotion-arousing words and bias?

C. Coverage

- Does the work update other sources, substantiate other materials you have read, or add new information? Does it extensively or marginally cover your topic? You should explore enough sources to obtain a variety of viewpoints.

- Is the material primary or secondary in nature? Primary sources are the raw material of the research process. Secondary sources are based on primary sources. For example, if you were researching Konrad Adenauer's role in rebuilding West Germany after World War II, Adenauer's own writings would be one of many primary sources available on this topic. Others might include relevant government documents and contemporary German newspaper articles. Scholars use this primary material to help generate historical interpretations--a secondary source. Books, encyclopedia articles, and scholarly journal articles about Adenauer's role are considered secondary sources. In the sciences, journal articles and conference proceedings written by experimenters reporting the results of their research are primary documents. Choose both primary and secondary sources when you have the opportunity.

D. Writing Style

Is the publication organized logically? Are the main points clearly presented? Do you find the text easy to read, or is it stilted or choppy? Is the author's argument repetitive?

E. Evaluative Reviews

- Locate critical reviews of books in a reviewing source , such as the Articles & Full Text , Book Review Index , Book Review Digest, and ProQuest Research Library . Is the review positive? Is the book under review considered a valuable contribution to the field? Does the reviewer mention other books that might be better? If so, locate these sources for more information on your topic.

- Do the various reviewers agree on the value or attributes of the book or has it aroused controversy among the critics?

- For Web sites, consider consulting this evaluation source from UC Berkeley .

Permissions Information

If you wish to use or adapt any or all of the content of this Guide go to Cornell Library's Research Guides Use Conditions to review our use permissions and our Creative Commons license.

- Next: Tips >>

- Last Updated: Apr 18, 2022 1:43 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.cornell.edu/critically_analyzing

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 08 May 2024

A meta-analysis on global change drivers and the risk of infectious disease

- Michael B. Mahon ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9436-2998 1 , 2 na1 ,

- Alexandra Sack 1 , 3 na1 ,

- O. Alejandro Aleuy 1 ,

- Carly Barbera 1 ,

- Ethan Brown ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0827-4906 1 ,

- Heather Buelow ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3535-4151 1 ,

- David J. Civitello 4 ,

- Jeremy M. Cohen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9611-9150 5 ,

- Luz A. de Wit ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3045-4017 1 ,

- Meghan Forstchen 1 , 3 ,

- Fletcher W. Halliday 6 ,

- Patrick Heffernan 1 ,

- Sarah A. Knutie 7 ,

- Alexis Korotasz 1 ,

- Joanna G. Larson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1401-7837 1 ,

- Samantha L. Rumschlag ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3125-8402 1 , 2 ,

- Emily Selland ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4527-297X 1 , 3 ,

- Alexander Shepack 1 ,

- Nitin Vincent ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8593-1116 1 &

- Jason R. Rohr ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8285-4912 1 , 2 , 3 na1

Nature ( 2024 ) Cite this article

192 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Infectious diseases

Anthropogenic change is contributing to the rise in emerging infectious diseases, which are significantly correlated with socioeconomic, environmental and ecological factors 1 . Studies have shown that infectious disease risk is modified by changes to biodiversity 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , climate change 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , chemical pollution 12 , 13 , 14 , landscape transformations 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 and species introductions 21 . However, it remains unclear which global change drivers most increase disease and under what contexts. Here we amassed a dataset from the literature that contains 2,938 observations of infectious disease responses to global change drivers across 1,497 host–parasite combinations, including plant, animal and human hosts. We found that biodiversity loss, chemical pollution, climate change and introduced species are associated with increases in disease-related end points or harm, whereas urbanization is associated with decreases in disease end points. Natural biodiversity gradients, deforestation and forest fragmentation are comparatively unimportant or idiosyncratic as drivers of disease. Overall, these results are consistent across human and non-human diseases. Nevertheless, context-dependent effects of the global change drivers on disease were found to be common. The findings uncovered by this meta-analysis should help target disease management and surveillance efforts towards global change drivers that increase disease. Specifically, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, managing ecosystem health, and preventing biological invasions and biodiversity loss could help to reduce the burden of plant, animal and human diseases, especially when coupled with improvements to social and economic determinants of health.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout