122 Festival Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

A festival is a celebration of some holiday, achievements, or other occasions for one or several days. Festivals can be religious, national, seasonal; they can be dedicated to arts, food, fashion, sports, etc. When working on a festival essay, it is essential to consider several aspects. For example, research the history and cultural meaning of an event.

In our compilation of festival topics, we included many topics about festivals (Woodstock, Richmond Folk Festival, Film Festivals, and others). You will also find broad issues about festivals’ cultural heritage and history.

🏆 Best Festival Topic Ideas & Essay Examples

🥇 most interesting festival topics to write about, 📌 simple & easy festival essay titles, 👍 good essay topics on festival, ❓ essay questions about festivals.

- Music Festival Project Management The project is concerned with planning a one-day Music Festival that will take place on the 4th of June 2011, in Greenwich Park.

- School Music Festival Concert The preliminary rounds will be designed to ensure that only the participants who measure up to the high standards of the competition are allowed to go on to the next stage of the competition while […]

- Arts and Crafts Festival Event In addition to informing the people on the huge variety of arts and crafts the company has been able to collect from various parts of the world over time, this event will be a good […]

- Ramadan Celebration: The Religious Festival To conclude, Ramadan month, a religious festival, is my favorite and most memorable event of the year. Individuals behaving better and kinder towards others during this month is another part of the festival that I […]

- The Negative Social Impacts of “Tomorrowland Music Festival” Despite the benefits of this festival for the local community, such as increased economic activity and employment, “Tomorrowland” has also been criticized for the presence of drugs on-site, the issues with cleaning up the location […]

- Spring Festival Gala Event The festival has led to massive public awareness on the Chinese culture The culture movement led to the realization of the importance of the support received from the mass media and the role the popular […]

- Summer Music Festival: Event Project Management Plan The main objective of the festival is to raise funds for the Children Society of the United Kingdom. People below the age of fifteen years have low power and less interest in the event because […]

- Melbourne Food and Wine Festival in Australia The Melbourne Food and Wine Festival is held throughout Melbourne showcasing the urban and regional life of the city and its various food and wine offerings to reinforce the position of the city of Melbourne […]

- Woodstock Music Festival Even though the Woodstock Music Festival was intended to be a ticketed event, ultimately, the planners stopped collecting the tickets because the crowd started to cut away and to trample the fences which made even […]

- Lantern Festival and Rice Ball Moreover, the rice balls are an essential component of the Lantern festival because they are the reason why the fire goddess spared the city of Chang’an.

- Auckland Lantern Festival Event Management Plan The festival will supply the entertainment as well as the props necessary for the performers, but stallholders will have to pay for their spots at the venue.

- Management in Action: The Fyre Festival Case The process begins with a practical idea and a budget that aligns with the resources needed for the event. The standard event planning procedures will be used in getting the resolution to the challenges faced […]

- Food Safety Policy for a Music Festival Several food businesses are expected to be at the festival thus posing a threat to the health of the participants should the right measures fail to be implemented to avoid the spread of food-borne diseases.

- History of Mexican Festival The experience of attending the Mexican festival stretched my cultural perception as I discovered that Mexicans have a rich culture in terms of food, art, and music.

- Festival of Britain, Its History and Success The rationale behind it was to point to the reconstruction of London and the incorporation of futuristic buildings in the architecture of the city.

- The Global Festival of Halloween or Hallow Eve The festival’s roots came from the traditions of religious attention to the edge between the world of the living and the dead.

- A Maslenitsa Festival as a Cultural Event In the video, one could see how people sing, dance, play the accordion, cook and eat pancakes, play team games, such as tug of war and king of the hill, and build a fortress out […]

- The San Joaquin Asparagus Festival in California People from around the region travel to Stockton to join the locals in the celebration of the food that is currently regarded as belonging to individuals in the high-class category.

- Ultra Music Festival Twitter Marketing The first step of the marketing strategy development in this respect is the choice of a platform that corresponds to the goals of marketing.

- The Woodstock Music Festival’s Organizational Challenges For the next Woodstock in 1994, the organizers decided to review their strategies, setting the $135 ticket price. After such a disaster, the festival’s project in 2019 was doomed to fail.

- Transformative Festival Experience: A Comparative Analysis Other important aspect of the transformative component within the leisure experiences is, according to the article, the contrast between the event the question and the general daily experience of a tourist.

- The Orange F.O.O.D Week Festival in Australia Provenance refers to the origin of a particular object or phenomenon, and in this case, it is of food and wine of the Orange Region.

- Food Provision at the Annisburgh District Music Festival It will promote the careers of the local and international artists who will be performing at the event and raise the profile of the district leading to a positive reputation. Over the course of the […]

- Ottawa Folk Festival Management Issues If the festival’s management would implement a no change scenario to the problem of a low level of attendance by young people, the state of affairs will stay the same: the festival will be only […]

- Santa Barbara International Film Festival In its eleven-day span, the festival aims to enrich the local culture and enhance the awareness of film as a form of art.

- Statistics. Exploring the Festival Data From the histogram, we can observe that the festival data of day one is normally distributed about the mean of the data.

- Independent Arts and Crafts Festival: Event Safety However, for a festival of such to be successful much legal documentation has to be put in place and some of these are contracts and fees agreements and the acquiring of some legal documents for […]

- Flavours of Chittering Food & Wine Festival: Analysis As some of the local restaurants are based on cooking the food from the products grown in the valley, people are likely to learn about the real tastes of food in those restaurants because the […]

- Benefits of a Non-Profit Bookfair Festival for a Major US City A book fair in San Antonio would be attended by panelists whose interest would be to discuss the future in books, lovers of poetry who would listen and enjoy recitations and publishers. Considering the fuss […]

- Woodstock Music and Art Fair During the fun and revels of the Woodstock festival, the hippies and flower children were treated to an incredible roster of talented and legendary musicians.

- The Chicago International Film Festival As a matter of fact, the festival’s website points out that it has had a consistent objective that still remains to this moment, “…to discover and present new filmmakers to Chicago, and to acknowledge and […]

- Edinburgh Multi-Day International Festival: Event Evaluation The Edinburgh Festival follows a mission of being the most exciting, innovative, and accessible festival in the world in the realm of the performing arts, promoting the cultural, educational, and economic well-being of the people […]

- Lunar Vietnamese New Year’s Event: Flower Festival It should be noted that the festival is held for several days, and its primary purpose is to prepare the visiting people for the main celebration. The center of all activities that bring the majority […]

- Calvin Jones Big Band Jazz Festival The most interesting feature of the show was the participation of bands from three different colleges the University of the District of Columbia Jazz Ensemble, the Howard University Jazz Ensemble, and the University of Maryland […]

- The Dragon Boat Festival on Qi’ao Island The origins of the holiday are unknown, but there are many popular theories that suggest the holiday to be associated with the death of Qu Yang a famous Chinese thinker and poet.

- Qasr Al Hosn Festival Press Release The festival has been celebrated since the development of the fort in the 1760s. Apart from celebrating the Emirati history, the festival aims to give visitors a chance to appreciate the Emirati heritage that is […]

- Dubai Jazz Festival Press Release James Blunt, who will be in Dubai for the third time, will perform on the first day of the festival together with Christina Perri.

- African Circumcision Festival and Western Attitude I would make sure that I want to visit this event for the elders to be sure that I am interested in the supportive environment at the workplace and the place, I am living.

- Richmond Folk Festival Performances The major goal the organizers of the festival pursue is to present the best traditional musicians found all across the country and to let the audience enjoy their unique talents.

- Made in America Musical Festival Planning Overall, festival planning involves many steps and stages that are crucial to the success of the event, as well as to the safety and security of all visitors.

- Michael Jackson Festival’s Start-Up Business The primary goal of this paper is to develop a detailed start-up business for the Michael Jackson festival with the assistance of the business model canvas.

- Festival Organization Service Operations The increasing number of festivals in both Europe and other parts of the world reduces the efficiency and organisational mechanisms of the events leading to the emergence of other organisational bodies such as the American […]

- The 2014 Joondalup Festival Details In addition, the report focuses on identifying the theme of the event, objectives associated with the event and the philosophy of the event, among other event aspects.

- The Wollongong Music Festival Arranging The paper analyses the roles of the key stakeholders in the Wollongong music festival. Because of the location, the festival may cause major conflicts with the businesses adjoining the venue.

- Ajyal Film Festival and Youth Empowerment The DFI organizes the Ajyal Film Festival to present the film products of its most talented young actors and producers to the government and the business community, as well as the rest of the world.

- College Students’ Satisfaction of Music Festival in China Aquinas says that one of the reasons why music festivals are popular among the students is because they offer them the opportunity to express their feelings.

- Moomba Festival in Melbourne: Event, Significance of the Place, Infrastructure, and Effect on the City Image The reason for the event includes a number of factors that reflect the events that were held in the early 1950s and predestined the start of the festival.

- Promotion Strategy for a Green Festival The main reason for planning the green festival is to get residents of Dubai and its environs to realize the importance of environmental conservation. Secondly, the venue of the green festival and how people will […]

- Charity Softball and Cultural Festival While the main event in the festival will be the softball tournament, the organizers of the charity softball and cultural festival hope to raise funds through several ways.

- A Travel Into the Korean Culture: 2012 Korean Festival in Houston One of the most vivid and memorable events in the Korean culture, the Korean Festival in Houston makes one dive into the Korean culture and understand the essence of the Korean dances.

- Woodstock Music and Art Festival In this paper, we will explore on Woodstock Music and Art festival, the challenges that were faced, and the impact of the festival to the music industry.

- The Mimir Chamber Music Festival Concert The three characteristics were the dynamics, intonation and ensemble where the intonation was brought about by the string quartet playing, the dynamics brought by the careful modulation and the ensemble bringing in a complete experience […]

- The Live Concert by Aleksandr Rybak and the Electo Zoo Festival The lighting and the special effects became a valuable contribution to the performance, intensifying the impression from the beautiful music and the personal charm of the talented performers.

- How to fund a non profit community book festival Through online forums, the visitors of the website can be made aware of the community book festival and be requested to donate funds for the activity.

- Festival in Greektown, Chicago: Due to the fact that this district is one of those that make up the community area, the festival offered to its citizens has to be community based. It is necessary to take care of […]

- The Tibetan Freedom Festival Drives Forward the Cause for Tibetan People

- The History of the Bands of America National Concert Band Festival

- The Venice Film Festival And The Cannes Film Festival

- Understanding the UK: David Cannadine at Edinburgh International Book Festival

- The History and the Symbolism of the Festival of Pesach

- Tradition in Our Culture: the Mid-Autumn Festival

- Tomorrowland: Electronic Music Festival

- The History and Cultural Importance of the Dragon Boat Festival in China

- The Songkran Festival: Traditional New Year’s Day

- The Three Days of Peace and Music During the Woodstock Festival in 1969

- The San Fermin Festival And The Running Of The Bulls

- The On Matsuri Festival Of Kasuga Wakamiya Shrine

- The Festival of Politics: Karl Marx Lecture with Professor Gareth Stedman Jones

- The Role of Green-Festivals Affecting Pro-Environmental Attitudes: The Case of Glastonbury Festival

- The Epa headdress of the Yoruba Epa Festival

- The Impact of Edinburgh International Festival

- The Deployment of Mobile Base Transceiver Station During Lisabi Festival at Abeokuta

- The Role Of Festival In The Mayor Of Casterbridge

- The Implication of Road Toll Discount for Mode Choice: Intercity Travel during the Chinese Spring Festival Holiday

- Vietnam: Lunar New Year Festival

- The Yulin Dog Meat Festival and American Views

- The Flaws and Brilliance of the Sundance Film Festival

- The Impact of the Woodstock Festival in America during the 1960’s

- The Concert At The International Chamber Music Festival Concert

- The Diwali Festival, Its Importance to Hinduism, and Pollution in Diwali

- The New Music Festival : Sound, Light, And Healing

- The Invalid American Views on the Yulin Dog Meat Festival

- The Evolution of Woodstock: A Rock Festival

- The Origin and History of the Interesting Festival of Halloween

- Woodstock Music and Art Festival

- The Largest Cultural Activity in Pakistan: Folk Festival or Lok Mela

- The Marketing of the Melbourne International Film Festival

- Western Festival in China

- The Traditions, Practices and the Processes in the Thaipusam Festival

- Whatever: Culture and Niagara Wine Festival

- The Cultural Impact of the Woodstock Music Festival to Society

- The Effect of Food Tourism Behavior on Food Festival Visitor’s Revisit Intention

- The Love Parade Festival Stampede 2010

- The Woodstock Festival and the Music of the 60s: A Peaceful Rock Revolution

- The History and Impact of Woodstock Music Festival

- The New Year Festival in Vietnam and in America

- The Night Nation Run – the World’s Running Music Festival

- Are Film Festivals Still Necessary?

- What Are the Negative Effects of Festivals?

- What Problems Do Music Festivals Cause?

- Are Religious Festivals Just an Excuse for a Party?

- Why Are Festivals Bad for the Environment?

- How Much Waste Do Festivals Produce?

- How Are the Religious Festivals Harming Our Ecosystem?

- What We Can Do for the Environment on Festivals?

- Why Do the Researchers Called Pollution the Flip Side of Festivals?

- How Much Waste Do UK Festivals Produce?

- What Do Festivals Do With Leftover Tents?

- How Do You Recover From Festivals?

- Where Are Some of the Largest Festivals Held in the United States?

- How Many Music Festivals Are There in the USA?

- How Rituals and Festivals Played a Crucial Role in Traditional European Life?

- What Are Traditional Festivals?

- What Are the Three National Festivals?

- Why Are American Festivals Important?

- What Are the Most Important Festivals in French Culture?

- How Do Festivals Bring Us Together?

- How Many Regional Festivals Are There?

- Are Festivals Important for a Country?

- What Are the Hidden Dangers of Music Festivals?

- What Is the Largest Attendance at The Music Festivals?

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, October 26). 122 Festival Essay Topic Ideas & Examples. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/festival-essay-topics/

"122 Festival Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." IvyPanda , 26 Oct. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/festival-essay-topics/.

IvyPanda . (2023) '122 Festival Essay Topic Ideas & Examples'. 26 October.

IvyPanda . 2023. "122 Festival Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." October 26, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/festival-essay-topics/.

1. IvyPanda . "122 Festival Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." October 26, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/festival-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "122 Festival Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." October 26, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/festival-essay-topics/.

- Popular Music Paper Topics

- Entertainment Ideas

- Dance Essay Ideas

- Social Media Topics

- Subculture Research Topics

- Fast Food Essay Titles

- Contemporary Art Questions

- Halloween Titles

- Tattoo Research Ideas

- Hinduism Topics

- Classical Music Paper Topics

- Hip Hop Essay Topics

- Music Topics

- Yoga Questions

- Ethnographic Paper Topics

We use cookies to enhance our website for you. Proceed if you agree to this policy or learn more about it.

- Essay Database >

- Essays Samples >

- Essay Types >

- Creative Writing Example

Festival Creative Writings Samples For Students

8 samples of this type

If you're seeking a viable method to simplify writing a Creative Writing about Festival, WowEssays.com paper writing service just might be able to help you out.

For starters, you should browse our large directory of free samples that cover most diverse Festival Creative Writing topics and showcase the best academic writing practices. Once you feel that you've determined the major principles of content structuring and drawn actionable ideas from these expertly written Creative Writing samples, putting together your own academic work should go much easier.

However, you might still find yourself in a circumstance when even using top-notch Festival Creative Writings doesn't let you get the job accomplished on time. In that case, you can contact our experts and ask them to craft a unique Festival paper according to your individual specifications. Buy college research paper or essay now!

Good Example Of Creative Writing On Music Ethnography

Creative writing on progress report, ghosttown creative writing examples.

125 Old Road

WTI 3331 22 98 Baker street

Don't waste your time searching for a sample.

Get your creative writing done by professional writers!

Just from $10/page

Diane Feinstein Creative Writing Examples

Proposal letter.

3612 Lemo Street

Las Cruces New Mexico 88003

African art creative writing sample, question one, wheretoget.it creative writing sample, story of the product, good example of work tasks / projects creative writing.

Internship at Mullenlowe Group

Introduction

Cultural event that changed me creative writing examples.

I have to admit that I like to think of myself as a nerd. I hardly go out. I like reading my books and having fun my own way. I am the late bloomer, I get trends last , and I am not that cool and I like my room, and occasionally my passionate moments with nature. This is how I lead my life. However, this was to change just by one event.

Password recovery email has been sent to [email protected]

Use your new password to log in

You are not register!

By clicking Register, you agree to our Terms of Service and that you have read our Privacy Policy .

Now you can download documents directly to your device!

Check your email! An email with your password has already been sent to you! Now you can download documents directly to your device.

or Use the QR code to Save this Paper to Your Phone

The sample is NOT original!

Short on a deadline?

Don't waste time. Get help with 11% off using code - GETWOWED

No, thanks! I'm fine with missing my deadline

April 13, 2024 Conference!

The 2024 Terroir Creative Writing Festival will be held on Saturday, April 13, at the Chehalem Cultural Center in Newberg. A mix of local and regional writers and publishing professionals will be speaking, giving workshops on craft, and reading their own work. The festival is open to anyone from 7th grade through adults of all ages.

The aim of the festival is to build a stronger literary community in our area by encouraging and spotlighting local writers while also making connections with the writing and publishing community beyond Yamhill County, but you don’t have to be a writer to attend. Anyone interested in writing, reading, and the literary life will find something to enjoy.

Schedule and Link to More Information

For details on this year’s speakers and sessions and to sign up

for email updates, please visit the festival website.

Over the years, the festival has definitely found a place in the creative life of Yamhill County. McMinnville’s Third Street Books has served the festival’s on-site bookstore since the beginning, and a number of local venues have hosted us: The McMinnville Community Center , The Yamhill Valley Campus of Chemeketa Community College , and now, the Chehalem Cultural Center in Newberg.

Past speakers

From the beginning, Terroir has hosted both emerging and established writers from the county and the region. Past speakers have included Ursula K. LeGuin, Molly Gloss, Jean Auel, Tracy Daugherty, Kim Stafford, Paulann Petersen, Henry Hughes, Fonda Lee, Chelsea Cain, Willy Vlautin, C. Morgan Kennedy, Andrea Stolowitz, Steve Duin, Laura Stanfill, Emily Grosvenor, Joe Wilkins, Barbara Drake, and many more. With 10 to 15 speakers each year, many outstanding authors have shared the secrets of their craft, offered encouragement, and given readings from their works.

Arts Alliance of Yamhill County

650 NE 2nd Street PO Box 898 McMinnville OR 97128

eMail info: [email protected]

A 501(C)3 non-profit organization

Copyright © 2024 - All Rights Reserved.

2024 festival

At the University of Mississippi, April 4-6, 2024

this year's program

Learn what's in store (and who's featured) this time at the University of Mississippi

Recording of 2023 Keynote Speaker Margaret Renkl

2024 host school

The 2024 Southern Literary Festival will take place Thursday, April 4 through Saturday, April 6, 2024 on the campus of the University of Mississippi in Oxford, MS. MORE INFORMATION >>

2024 SLF Contest results

We're pleased to announce the winners of the Undergraduate Writing Contest for the 2023-2024 festival year! Students are invited to read their winning work at the Festival in April 2024 at the University of Mississippi. They will also be published in this year's print anthology, available at the Festival. ANNOUNCEMENT>>

2024 Panelists & Speakers

Part of the Southern Literary Festival’s mission is to support undergraduate writers by connecting them with established writers. These honored festival guests participate in panel discussions, craft talks, and the festival bookfair. KEYNOTE: ANDRE DUBUS III >> PANELISTS & SPEAKERS >> FULL FESTIVAL SCHEDULE >>

The 2023 Anthology

The winners featured in our annual anthology were also featured readers at the Festival. All conference participants receive a copy of the anthology. Download your digital copy here today! DOWNLOAD THE ANTHOLOGY >>

Become a Member School Today!

Registering your institution for membership in the Southern Literary Festival Association first and foremost benefits your students. When you join the association, you’ll be able to submit to our competition and anthology in the Fall and attend our conference with your students in the Spring. JOIN >> PAY DUES >>

- Mission, vision, purpose

- Our History

- Benefits of Membership

2024 FESTIVAL

- Host School

- keynote speaker

- festival schedule

- Member Schools

COMPETITION

- Submit your work

- 2024 winners

- 2023 Winners

- Past winners

Please come back in Fall 2024 for information about our next competition.

- Download 2023 SLF Anthology

- Download 2022 SLF Anthology

- Download 2021 SLF Anthology

- Download 2020 SLF Anthology

- Give to ECU

- Future Students

- Current Students

- Parent & Family

Annual Scissortail Creative Writing Festival scheduled for April 4-6, 2024

ADA, Okla. – The annual Scissortail Creative Writing Festival returns to East Central University April 4-6, 2024, marking the 19th festival to take place.

Kai Coggin, Steve Yarbrough and Quraysh Ali Lansana, will be the featured authors this year. The event is free and open to the public.

The Scissortail Creative Writing Festival features Oklahoma’s most prestigious high school creative writing competition. The annual Darryl Fisher Creative Writing Contest, now in its 20th year, is open to all state high school students submitting poetry or short works of fiction. Winners and awards for the state-wide competition, as well as the Undergraduate Contest, will be presented during the event.

The three-day festival attracts an array of known and up-and-coming authors from across Oklahoma and the country. Over 70 authors will reading in 25 sessions. The schedule and updates are available at ecuscissortail.blogspot.com .

For more information on the Scissortail Creative Writing Festival or questions about group attendance, contact organizer Dr. Ken Hada at 580-559-5557 or via email at [email protected] .

Below are bios for the featured speakers. Full bios and information on all authors participating can be found on the Scissortail Creative Writing Festival blog.

Kai Coggin Kai Coggin (she/her) is the inaugural Poet Laureate of the City of Hot Springs, Arkansas, and author of four collections, most recently “Mining for Stardust.”

She is a Certified Master Naturalist, a K-12 Teaching Artist in poetry with the Arkansas Arts Council, an Artist Leadership Fellow with the Mid-America Arts Alliance, and host of the longest running consecutive weekly open mic series in the country—Wednesday Night Poetry. Recently awarded the 2021 Governor’s Arts Award, named “Best Poet in Arkansas” by the Arkansas Times, and nominated for Arkansas State Poet Laureate and Hot Springs Woman of the Year, her poetry has been nominated six times for The Pushcart Prize, as well as Bettering American Poetry 2015, and Best of the Net 2016, 2018, 2021— awarded in 2022. Ten of Kai’s poems are going to the moon with the Lunar Codex project, and on earth they have appeared or are forthcoming in POETRY, Prairie Schooner, Best of the Net and elsewhere. Coggin is Associate Editor at The Rise Up Review, and serves on the Board of Directors of the International Women’s Writing Guild.

Steve Yarbrough Steve Yarbrough is the author of twelve books, most recently the novel “Stay Gone Days,” due out in April 2022.

His work has been published in several foreign languages, including Dutch, Italian, Japanese and Polish, and it has also appeared in Ireland, Canada, and the U.K.

He is the recipient of numerous awards, including the Mississippi Institute of Arts and Letters Award for Fiction, the California Book Award, the Richard Wright Award and the Robert Penn Warren Award. He has been a finalist for the PEN/Faulkner Award and is a member of the Fellowship of Southern Writers. His novel “The Unmade World” won the 2019 Massachusetts Book Award for Fiction.

The son of Mississippi Delta cotton farmers, Steve is currently a professor in the Department of Writing, Literature and Publishing at Emerson College. Quraysh Ali Lansana Quraysh Ali Lansana earned his Master of Fine Arts (MFA) from New York University. He is the author of several poetry collections including “A Gift from Greensboro,” “mystic turf” and more. His chapbooks include “reluctant minivan,” “bloodsoil,” “Greatest Hits: 1995-2005” and “cockroach children: corner poems and street psalms.” He has also written a children’s book, “The Big World.”

He is the editor of Glencoe/McGraw-Hill's “African American Literature Reader,” with several other editor and co-editor credits. “Our Difficult Sunlight: A Guide to Poetry, Literacy & Social Justice in Classroom & Community” was published by Teachers & Writers Collaborative and was a 2012 National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) Image Award nominee.

Recent books include “The Breakbeat Poets: New American Poetry in the Age of Hip Hop,” “Revise the Psalm: Work Celebrating the Writings of Gwendolyn Brooks”, with Sandra Jackson-Opoku, among others.

Lansana has been a literary teaching artist and curriculum developer for over a decade and has led workshops in prisons, public schools, and universities in over 30 states. He is a former faculty member of the Drama Division of The Juilliard School, and served as Director of the Gwendolyn Brooks Center for Black Literature and Creative Writing at Chicago State University from 2002-2011, where he was also Associate Professor of English/Creative Writing. Currently, Lansana is on faculty in the Creative Writing Program of the School of the Art Institute in Chicago and the Red Earth MFA Creative Writing Program at Oklahoma City University.

Share this post

- Educational Resources

- Career Center

- Find a School

Search Options

Additional search resources, login.

The following areas are also available:

- Donor Portal

- Learning Portal

- My Membership Profile/Account

- Purposeful Design Publications (Store)

Find a School

menu - site map, quick access menu.

Main Navigation Menu Items

- Academic Support Programs

- Accreditation & Certification

- Store (Purposeful Design Publications)

- Find Your Office

- Public Policy & Legal Affairs

- Professional Development

- Thought Leadership

- Flourishing Schools

Menu by Audience

- School Leader Resources

- Teacher and Faculty Resources

- Parent and Student Resources

- Christian Education Champions

Common Links

- Accreditation & Certification Documents

- Blog & Podcasts

- Learning & CEUs

- My Account/Profile

- Contact Us - Customer Care

Footer Navigation

- Schools: Accreditation Documents

- Teachers: Certification Documents

- What is Accreditation?

- What is Certification?

- Find a Job, Post a Job, ACSI Jobs

- Strategic Partnership Program

- Student Leadership & Learning

Calendar of Events

Events by Category - Registration Links

- Early Education

- Early Education: Cultivating Resilience

- Flourishing Schools Institute

- Flourishing Deeper: Sustainability

- HR & Employment Law for Christian Schools

- International

- Leadership Conference

- Leadership U

- Pre-Conference Educator Training

- Student Leadership & Learning Events

- Student Assessment

Mark your Calendars!

As you are ending this school year and beginning to plan for the 2023-2024 school year, ACSI invites you to mark your calendar and make plans to attend the many ACSI events and experiences happening in the United States. Learn more about our upcoming events.

- Early Education: Reignite

- Flourishing School Institute (FSi)

- ACSI Public Policy & Advocacy Summit

- ACSI Student Assessment Program

- Leadership Network Meetings

- Parents & Students

Creative Writing Festival Resources

Chairperson & Coordinator Resources

ACSI Student Leadership & Learning provides event handbooks and resources for all activities to assist school Coordinators and event Chairpersons in preparation for their upcoming events. School Coordinators are responsible for overseeing student participants and adult volunteers from his or her own school. Event Chairpersons manage a group of registered schools for a specific Student Leadership & Learning event.

Note: All Student Leadership & Learning resources are password protected. The password is given to the school Coordinator once registration has been confirmed by ACSI. All questions may be directed to a Student Leadership & Learning team member .

Coordinator Resources

- Coordinator Handbook

- Student Participation Form

- Judge Volunteer Form

- Creative Writing Festival Certificate

- Student Leadership & Learning Evaluation Form

Chairperson Resources

- Chairperson Handbook

- Judge Packet

- Judge Information Form

- ACH Authorization Form

- Post-Event Finance Report

- Award Inventory Report

Access the: ACSI STUDENT E-VENTS PLATFORM HERE

Student Leadership Programs

Student Leadership Institute

Student Leadership Summit

Student Leadership & Apologetics Conference

Great Commission Project

Student Learning Programs

International Christian STEM Competition

National Math Competition

Performing & Fine Arts Program

Speech and Rhetoric

Venture: Entrepreneurial Innovation Challenge

Distinguished Christian High School Student Award Details

Student Leadership & Learning Event Resources

Art Festival Resources

Math Olympics Resources

Music Events Resources

One-Act Play Festival Resources

Speech Meet Resources

Spelling Bee Resources

Venture Resources

International Christian STEM Competition Resources

- Meet Your Student Leadership & Learning Team

Invention Creative Writing Workshop

Friday, march 22, 2024 (register by march 15, 2024), with special guests award-winning folk musician david wilcox and award-winning novelist sarah loudin thomas, about montreat’s creative writing festival.

Montreat’s Annual Creative Writing Festival offers a one-day experience with creative writing and is welcome to people of all ages, locations, and interests. Songwriting workshops, story-writing strategies, character workshops, publishing advice, and sessions with expert writers are only a few of the previous Montreat Creative Writing Festival offerings. Our past and present guests represent a variety of creative writing interests, including children’s literature author Kimberly Angle, historical fiction and Appalachian fiction author Sarah Loudin Thomas, poet Andy Coe, NY Times bestselling novelist William R. Forstchen, and award-winning folk musician David Wilcox.

2024 Creative Writing Festival Theme: Invention

Invention is the first step in the creative process where writers invent or discover ideas to fuel their writing. We will explore invention: not only how it begins the creative process but also how it is carried throughout planning and organization, writing and revising, as well as editing and publishing.

Registration

Attendees must register for Montreat College’s Annual Creative Writing Festival by March 15, 2023. Registration includes lunch at the college’s Howerton Dining Hall.

General Admission: $15 High School Students and Caregivers: $5

Single Registration

Register using the Single Registration Form if you are a student, parent/caretaker, or a member of the community. If you are registering multiple people within your party, you may do so using this form by clicking “Add Another Attendee.”

Group Registration

Register using the Group Registration Form if you are a school group leader registering yourself and your group of high school students.

Special Guests

David wilcox.

David Wilcox has been connecting with his audiences since his debut album in 1987, The Nightshift Watchman , led him to win the prestigious Kerrville folk festival and a four-album deal with A&M Records. Nearly three decades and over twenty albums later, his writing continues to impact listeners, even garnering top honors in the 23rd annual USA Songwriting Competition in 2018 for “We Make the Way by Walking.” David’s revered folk music is accompanied by heartfelt lyrics and thoughtful storytelling that will undoubtedly appear in his next studio album, due 2024. Find out more about David at https://www.davidwilcox.com/ .

Sarah Loudin Thomas

Sarah Loudin Thomas’ historical fiction celebrates the people, the land, and the heritage of Appalachia. Sarah holds a bachelor’s degree in English from Coastal Carolina University and is the author of the acclaimed novels The Right Kind of Fool– winner of the 2021 Selah Book of the Year–and Miracle in a Dry Season –winner of the 2015 Inspy Award. Sarah has also been a finalist for the Christy Award, ACFW Carol Award and the Christian Book of the Year Award. She and her husband live in western North Carolina where she is the director of Jan Karon’s Mitford Museum. Learn more by visiting www.SarahLoudinThomas.com .

8:30-9:30 a.m. | Check-in | Gaither Fellowship Hall 9:30-10:20 a.m. | Opening remarks | Graham Chapel Panel session with creative specialists 10:30-11:20 a.m. | Breakout sessions | Songwriting workshops featuring folk musician David Wilcox; Workshop with novelist Sarah Loudin Thomas 11:20 a.m.-12:20 p.m. | Lunch (provided) | Howerton Dining Hall 12:30-1:30 p.m. | Songwriting forum with David Wilcox 1:30-2:15 p.m. | Campus tours 2:15-2:30 p.m. | Closing session and Award Ceremony | Graham Chapel

Registration is live now! Cost is $5 for high school students & parents/teachers. General admission is $15

The 2024 creative writing competition.

We invite current junior and senior high school students who are attending the Creative Writing Festival to submit one poetry piece and/or one prose piece. Winners in each category (11th grade poetry, 11th grade prose, 12th grade poetry, and 12th grade prose) will receive a $1,500 scholarship to Montreat College. All entries are due by March 15, 2024.

Eligibility

- 11th grade or 12th grade high school student

- Maximum of one poem and one prose piece per writer

- Attendance at the 2024 Creative Writing Festival

- Entries should be submitted in Microsoft Word or Google Document files and formatted in Times New Roman, 12 pt font with single-spaced text.

- The Creative Writing Festival is offered by Montreat College with its Vision, Mission, Statement of Faith, and Community Life Covenant: https://www.montreat.edu/about/mission/ . We do not expect entries to address the College’s values, and we welcome submissions from writers who see the world from all vantage points; however, entries will be evaluated with consideration of the College’s values.

- Submissions generated in whole or in part by artificial intelligence are forbidden: no exceptions!

- No more than 5,000 words per submission

- Prose pieces may stand alone, such as a short story, or may be a portion of a larger work.

Each submission must be in a separate document. That is, a student submitting a poem and a short story must submit two separate files—one with the poem and one with the short story, each submitted separately via the appropriate form below.

The file must be named with the writer’s last name followed by the initial of the writer’s first name, a hyphen, and the name of the writer’s text, such as the following poem by John Smith entitled “Fly Away”:

- Smith J – Fly Away.docx

Poetry Competition

Prose Competition

Rights to Publication

By the act of submission, each contestant releases one-time rights for their work to Montreat College for editing and publishing in both print and online versions of the college’s arts magazine, The Lamp Post . Submission does not guarantee publication in The Lamp Post . Authors retain full ownership of their works, and this release does not prohibit authors from publishing their works elsewhere.

Please see past editions of The Lamp Post here: https://www.montreat.edu/academics/undergraduate/english/lamp-post/ .

English Program at Montreat College

Check out the English program at Montreat with its literature, creative writing, and professional writing concentrations: https://www.montreat.edu/academics/undergraduate/english/ .

Please direct any questions to the Director of the Writing Program, Dr. Zachary Rhone: [email protected] .

Writing Festival 2024

first biennial, raymond carver and tess gallagher creative writing festival: april 25, 26, and 27 2024 in port angeles, wa..

SPECIAL GUESTS:

Our keynote guests are Tess Gallagher, Billy Collins, TC Boyle, and Selected Shorts.

Celebrate creative writing in Port Angeles, a gritty coastal village where the mountains meet the sea.

Authors, Panelists, Workshop Teachers, and Speakers:

Billy Collins, TC Boyle, Tess Gallagher, Jonathan Evison, Harold Schweizer, CMarie Fuhrman, Alice Derry, Gary Copeland-Lilley, Holly Hughes, Lawrence Matsuda, Tim McNulty, Lisa C. Taylor, Anna Quinn, Charlotte Gould-Warren, Kate Reavey, Chuck Augello, Trinnie Dalton, Kama O’Connor, Asher Finch, Lauren Hanssen, Marianne Monson, Kristine Rae Anderson, Allison Green, Risa Denenberg, Lara Starcevich, Stanley A. Galloway, Holly Norton, Holly Marie Moore, Sam Robison, Teresa Janssen

FESTIVAL OVERVIEW:

The festival includes keynote readings, a film screening, a dance performance, conference style presentations, pie and poetry at Carver’s grave, writing workshops led by accomplished Northwest writers, and more. Catered lunches are included with festival passes on Thursday and Friday.

Two Free Events are open to the public: April 26th 4:00 at Field Arts & Events Hall The Suitcase Players (reserve free RSVP tickets online through Field Hall) / and / Thurs: April 25 12:30-1:30 Studium Lit Reading in PC’s Little Theater (no RSVP required).

All access festival passes are $400. This include sixteen events, two lunches, and a commemorative art piece. Tickets are non-refundable. Follow this link to register: This link will take you to EventBrite.

The all access pass includes all events and activities with the exception of our instructor led creative writing workshops.

Writing workshops are $120. Each workshop meets Thursday and Saturday for two hours each day. Workshops are non-refundable. View a list of instructors and workshop topics on the Workshop Authors 2024 page.

Tickets will be available for all keynote readings at Field Arts & Events Hall for $15 each (plus processing fees) if you’d like extra tickets for friends or family. We expect these tickets to be available at least 2 months prior to the event. Additional tickets to Selected Shorts are $30 (plus processing fees) and are available now.

Students can request a free ticket to one event. A limited number of free student tickets are available for individual panels and readings. E-mail Michael Mills @ [email protected]

SCHOLARSHIPS:

Thanks to the generous gifts of authors and literature patrons, we offer the following Scholarships:

The Lawrence Matsuda Scholarship will provide one attendee an all access festival pass. Lawrence Matsuda Scholarship

The Karen Matsuda scholarship will provide one attendee an all access festival pass. Karen Matsuda Scholarship

The Sally Hedges-Blanquez scholarship will provide one attendee one festival pass and one writing workshop. Sally Hedges-Blanquez Scholarship

To apply, follow the directions in one of the attached documents above. Apply as soon as possible so we can notify Scholarship recipients with sufficient time to make travel arrangements.

PRESENTATIONS and PANELS

A variety of readings, craft talks, and academic presentations will be presented. For dates, times, presenter names, and titles see the full festival schedule.

All events will be held on the gorgeous Peninsula College campus in Port Angeles, Washington, with the exception of the keynote readings, which will be held at the brand new Field Arts & Events Hall.

EVENT SCHEDULE:

Find the full event schedule here: Full Festival Schedule Plus Panels

Events will run from 9 AM to 9 PM Thursday, Friday, and Saturday ending with our keynote readings with Boyle, Collins, and Gallagher and a special performance by Selected Shorts.

The hit public radio series Selected Shorts takes the stage at Field Arts & Events Hall. Actors Dion Graham ( The Wire ), Zach Grenier ( Devs ), and Kirsten Vangsness ( Criminal Minds ) perform extraordinary short stories and poetry by four masters of the form: T. C. Boyle, Raymond Carver, Billy Collins, and Tess Gallagher.

(Actors subject to change.)

Our greatest actors transport us through the magic of fiction, one short story at a time. Funny, moving, and captivating, Selected Shorts connects you to the world with a rich diversity of voices from literature, film, theater, and comedy.

HOTEL ACCOMMODATIONS:

We have reserved a block of rooms at the Red Lion Hotel by City Pier. Waterfront rooms available! Use the following link to secure our discounted rates (Please note that multiple rates and room types are available: click “View More Rooms” for a full list of options.)

https://be.synxis.com/?Hotel=37106&Chain=13325&arrive=2024-04-25&depart=2024-04-27&adult=1&child=0&group=RCTG0425

Red Lion Address: 2104 E 1st St, Port Angeles, WA 98362. Phone: (360) 452-9215. If you call, be sure to request the festival rate.

WHILE YOU ARE HERE:

Check out our stunning local attractions:

Black Ball Ferry to Victoria, BC.

Sol Duc Hotsprings

Olympic National Park

Hoh Rainforest

And just down the street from our campus:

Port Angeles Fine Art Center and Quirky 5 Acre Sculpture Park

Contact Michael Mills at: [email protected]

Search for creative inspiration

19,890 quotes, descriptions and writing prompts, 4,964 themes

red square in moscow - quotes and descriptions to inspire creative writing

The picture had been taken in Red Square, in Moscow. Alex could see the onion-shaped towers of the Kremlin behind the man.

Found in Alex Rider, Skeleton Key , authored by Anthony Horowitz .

Sign in or sign up for Descriptionar i

Sign up for descriptionar i, recover your descriptionar i password.

Keep track of your favorite writers on Descriptionari

We won't spam your account. Set your permissions during sign up or at any time afterward.

- Best of Clallam County

- Best of Jefferson County

- Subscriber Center

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Email Newsletters

- Nation/World

- Clallam County News

- Jefferson County News

- Entertainment

- Submit a Wedding Announcement

- Submit a Letter to the Editor

- Place a Death Notice and/or an Obituary

- Classifieds

- Place a Classified Ad

- Real Estate

- Print Editions

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Marketplace

Creative writing festival to honor local authors

- Tuesday, January 16, 2024 1:30am

- Entertainment Clallam County

Book sale postponed

The faux paws perform sunday, more in entertainment, five acre school barn dance set for saturday.

Five Acre School will host its 14th Barn Dance… Continue reading

‘Stardust and Water’ to feature multimedia production

Turning the Wheel Productions will present “Stardust and Water”… Continue reading

Improv group to perform at Olympic Theatre Arts

Imagined Reality Improv will perform at 7 p.m. Saturday. The… Continue reading

Grand Olympics Chorus, friends revive the 1960s

‘A Grand Musical Adventure!’ set for Saturday performances

Harbor Art Gallery to host reception for artist

A reception for Carol Marshall will be conducted from… Continue reading

‘Breathe’ exhibit now open at Northwind Art

“Dreamy Afternoon” and “The Lava Exhaled” are among the… Continue reading

Music entertainment on tap for Peninsula this weekend

Music entertainment, an art walk and plays will highlight the Peninsula this… Continue reading

Singer to bring an American blend to Field Hall on Friday

Stephanie Anne Johnson learned by traveling on cruise ships

Community Chorus of Port Townsend and East Jefferson County to host weekend concerts

The Community Chorus of Port Townsend and East Jefferson… Continue reading

Monday Musicale to meet at Joshua’s

Monday Musicale will meet for lunch at noon Monday.… Continue reading

Curtis and Loretta to play at Concerts in the Woods

Curtis and Loretta will play at 3 p.m. Sunday for… Continue reading

Claire and Merah to perform at the Palindrome on Friday

Singer-songwriters Kathryn Claire and Margot Merah will perform at… Continue reading

Featured Local Savings

- Calendar/Events

- Navigate: Students

- One-Stop Resources

- Navigate: Staff

- My Wisconsin Portal

- More Resources

- CAMPS AND CONFERENCES

- Additional Camp and Clinic Youth Events

Creative Writing Festival

Registration is now closed for this event. Click here to join our email list to be notified of future events.

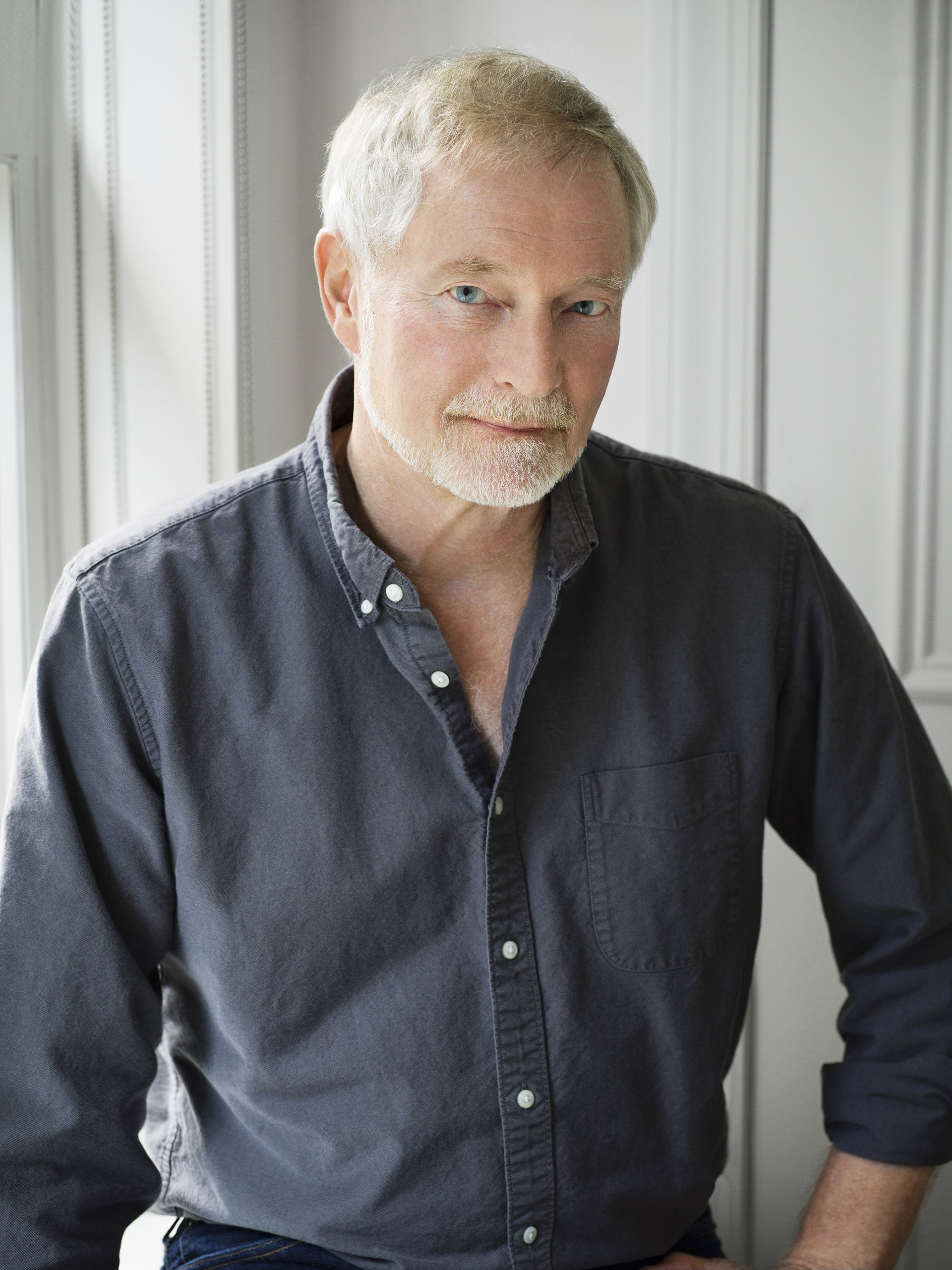

Join fellow students and faculty for a day of celebration and inspiration at the 39th Annual Creative Writing Festival. The 2023 event will again be hosted at UW-Whitewater, allowing high school students the opportunity to connect with peers and writing professionals in a college setting. Join the tradition and be one of over 500 students that attend annually.

During the festival, participants have the chance to attend workshops, keynote speeches, and competitions. These workshops cover a wide range of topics, including poetry, novels, creative nonfiction, and juvenile fiction. Students can learn new writing techniques, explore different genres, and gain insights from published authors. The festival also provides a space for networking and building connections with fellow writers and professionals in the industry.

Thursday, November 30, 2023 | 9:00 - 3:00 pm

Limited to the first 350 submissions, and 500 festival attendees.

Register Online

Registrations accepted online until:

- with submissions - Monday, October 23, 2023 | Deadline extended to Wednesday, November 1, 2023

- without submissions - Wedneday, November 22, 2023

Registration Questions

Advisors are encouraged to register for all participants attending from their school, instead of having each participant register singularly. Please have the answers prior to registering:

Advisor email, name, address, phone, school, how did you hear about this event, accommodations/comments, number of students attending with submission, number of students attending only, number of teachers attending with submission, number of teachers attending only

Identification & Proof of Originality

Each applicant submitting work will verify proof of originality through online registration system. The online registration link will be provided to you in your registration confirmation.

For the Students

- Workshops are designed for students in grades 9-12.

- Students' work will be discussed in assigned workshops.

- Workshops are limited, and student writers will be assigned in advance to the workshop in which their work is critiqued.

- Non-submitting participants may attend any session.

- Each submission will be carefully read and considered.

- A professional writer will make written comments on the original manuscript.

- The schedule designating the workshop assigned and meeting link will be available via the link in your registration confirmation, one day before the event.

Note: Because of the great number of entries in some categories such as poetry, our faculty cannot always discuss every work submitted.

For the Teachers

UW-Whitewater staff members and visiting writers will coordinate special teachers' writing workshops to be held concurrently with the students' workshop. Offerings are subject to interest and facilitator availability. Teachers who wish to submit their own work for consideration in a Teachers Writing Workshop should submit their work by the submission deadline.

Your online registration and payment are always safe and secure. We accept MasterCard and Visa credit card payments in our online registration system. We will NOT accept credit card payments over the phone. We will accept checks made out to "UW-Whitewater" and mailed to UW-Whitewater Camps and Conferences, 800 West Main Street, Room 2005 Roseman Hall, Whitewater WI 53190.

Confirmation Emails

Once you register, a confirmation email will be sent to your email account with details on how to submit and upload creative work. Contact [email protected] if you do not receive this confirmation email. Please make sure you have a working email address on file with us to be able to receive important announcements and updates about this event.

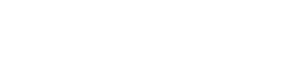

Erik Larson

Erik Larson is the author of eight books, six of which became New York Times bestsellers. His latest books, The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family, and Defiance During the Blitz and Dead Wake: The Last Crossing of the Lusitania , both hit no. 1 on the list soon after launch. His saga of the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893, The Devil in the White City , was a finalist for the National Book Award, and won an Edgar Award for fact-crime writing; it lingered on various Times bestseller lists for the better part of a decade. Hulu plans to adapt the book for a limited TV series, with Leonardo DiCaprio and Martin Scorsese as executive producers. Erik’s In the Garden of Beasts , about how America’s first ambassador to Nazi Germany and his daughter experienced the rising terror of Hitler’s rule, has been optioned by Tom Hanks for development as a feature film.

He graduated summa cum laude from the University of Pennsylvania, where he studied Russian history, language and culture; he received a masters in journalism from Columbia University. After a brief stint at the Bucks County Courier Times , Erik became a staff writer for The Wall Street Journal , and later a contributing writer for Time Magazine. His magazine stories have appeared in The New Yorker, The Atlantic Monthly, Harper’s , and other publications.

He has taught nonfiction writing at San Francisco State, the Johns Hopkins Writing Seminars, the University of Oregon, and the Chuckanut Writers Conference in Bellingham, Washington, and has spoken to audiences from coast to coast. A former resident of Seattle, he now lives in Manhattan with his wife, a neonatologist, who is also the author of the nonfiction memoir, Almost Home , which, as Erik puts it, “could make a stone cry.” They have three daughters in far-flung locations and professions. Their beloved dog Molly resides in an urn on a shelf overlooking Central Park, where they like to think she now spends most of her time.

RULES FOR SUBMISSION

- A participant may submit in only one category (poetry may have up to three titles per submission). See below.

- Participants will submit one file online using the Creative Writing Festival - Submission and Proof of Originality Form. A link will be available in the confirmation receipt and email once registration is completed.

- All manuscripts must include the author's name, and title of the piece, be double-spaced, and adhere to file name requirements, and to category page lengths.

- Submission must be saved as a pdf or mp3 file (not to exceed 25,000 KB) with category code, last name, and first name as the file name. Codes are found next to the categories below. Example: P.Doe.Jane would be the file name for Jane's poetry submission.

- Files exceeding 25,000 KB must be posted on a website and a link provided in a pdf for submission. YouTube can be used.

- We suggest posting the recording on a website (YouTube or other) and providing a PDF of song lyrics for submission.

- Drama/Screenplay entries must submit a video of the screenplay. It is suggested to post the recording on a website (Youtube or other) and provide the screenplay in a pdf for submission.

- Submissions must be received by Monday, October 23, 2023 | Deadline extended to Wednesday, November 1, 2023. Entries submitted after the deadline will not be considered for review.

- Participants can bring hard copies of their submissions for those auditing to read. Ten (10) copies are often sufficient.

- Submitting students must attend the session they are assigned to.

- All students will receive written feedback via email from the facilitators after their workshop sessions.

- At times, a facilitator is unable to attend their assigned session, due to unforeseen circumstances or technical difficulties. We will do everything possible to find a replacement and prevent needing to cancel a session.

- UW-Whitewater is required to report any submissions that indicate neglect, abuse, violence towards others, or self-harm.

Children's Literature (CL)

Maximum: 10 pages

Works written and appropriate for children ranging from toddler to roughly age 10. No topic restrictions other than appropriateness. Work may also include illustrations.

Drama or Screenplay (DR)

Maximum: 10 pages; submit recording/videos

A work (fiction or non-fiction) written in a fashion that can be performed; i.e., primarily comprising dialogue and some stage/screen direction and exposition.

Essay Expository (EE)

Maximum: 5 Pages

Non-fiction, non-poetical short works. Genres generally include, but are not limited to: Personal Narrative (tells a story), Descriptive (paints a picture in words).

Essay Personal

Non-fiction, non-poetical short works. Persuasive (attempts to persuade reader to a specific point of view).

Maximum: 5 pages

Can be in virtually any format (fiction, non-fiction, short drama, essay, etc.) as long as its primary aim is to provide humor and/or humorous entertainment.

Maximum: 3 poems (one pdf file for all three)

A piece of writing that employs some combination of lyrical, metrical, rhythmic, illusory, or imaginative power, frequently employing vivid or suggestive language/imagery or literary devices like similes and metaphors.

Prose Poem/Flash Fiction (PF)

Maximum: 3 pieces

A prose poem is a non-poetical piece that still embodies certain poetic qualities such as prominent rhythms, imagery, compactness, and intensity, though without necessarily rhyming or following a set metrical pattern. Flash fiction is an extremely brief (generally no more than a few hundred words) piece of prose fiction.

Fan Fiction/Science Fiction/Fantasy (FS)

Maximum: 5 pages

SciFi (science fiction) is prose fiction based on imagined future technological and/or scientific advances, frequently employing significant social or environmental changes, space travel, time travel, and/or alien life forms. Fantasy , also prose fiction, employs magical or supernatural qualities of the characters, plot, setting, or theme. While fantasy can employ any time setting, it is frequently set in worlds resembling ancient or medieval Earth. Fan Fiction , a new but growing genre, is a work of fiction set in a pre-existing world created by another author. For example, popular fan fiction works use the characters from a TV/movie series like Star Trek or Harry Potte r, but use those characters in new ways or takes them on new adventures that are imagined by the fan fiction author.

Short Fiction (SF)

Prose writing that presents imaginary people and events.

Song Lyrics (SL)

Submit recording/videos

Words set to music, often resembling a poem that can be sung. Submissions must include music. Post music to website and provide link in song lyric submission.

Tales of Terror & Mystery (TT)

Like fantasy fiction, tales of terror often incorporate supernatural beings, events, and settings, but differs in that its primary intent is to induce horror or terror. Tales of terror need not employ supernatural elements, though in a non-supernatural setting, the genre still creates an aura of eeriness or fright. Tales of mystery can employ many of the same elements as tales of terror, but its impact is intrigue rather than terror, or it offers an outré tale, or it can simply be a piece of crime fiction like a murder mystery.

Teacher (T)

Maximum: Refer above for each category

All creative writing by teachers

Cost Information

- PRIZES & REFUNDS

- Sponsorship & Awards

$35 Students/Teacher with submission

$25 Students/Teachers without submissions

Students who do not wish to submit a manuscript for evaluation in a workshop are still welcome to attend the Festival. These students are encouraged to participate in discussions of the work being considered in the various workshops. Students may not submit a manuscript for evaluation if they do not attend the Festival. Please submit one check from the school or adviser to cover all students attending.

Prize money has amounted to approximately $800 in previous Creative Writing Festivals. Awarding of prizes will depend on the number and quality of submissions per genre. We regret that it will not be possible to give refunds to those who are unable to attend . All cancellation requests must be submitted to [email protected] .

We reserve the right to cancel any event due to low enrollment; in this case, all fees paid will be refunded.

For participants who will be receiving a sponsorship to attend this event, please follow these steps to redeem your sponsorship:

- Register for the event and use the promo code provided by your sponsor during checkout.

- The sponsorship amount will be deducted from your invoice. Any remaining balance will be the participant's responsibility.

- If you need to cancel your registration, please note that the sponsorship funds will be returned to the supporting organization.

Please note that any qualifying discounts given by the event will not be applied after you have paid in full. Be sure to use the promo code during checkout to receive your discount. You will be charged if you do not qualify for the requested discount at the start of the event.

If a refund is issued due to overpayment on your account, a processing fee will be assessed.

If you have received an award or scholarship without a promo code or want to use two promo codes, please call Continuing Education Services at 262-472-3165 or email [email protected] before registering to avoid overpayment fees.

Want to Sponsor a Registrant? If you would like to sponsor a registrant and cover all or partial fees, you can request a promo code to give to your chosen registrant. For more details, please click here .

No discounts available for this event.

Additional Information

Festival check in.

Check-in will take place in University Center.

What Will I Need To Attend

- Lunch is not provided. Please feel free to bring your own or plan to purchase your lunch.

- Water Bottle (optional)

- 10 copies of Submission (optional)

Terms and Conditions

By registering for an event, you agree to our Registration Terms and Conditions. UW-Whitewater will hold all registrants responsible for their conduct. Serious misconduct or disruption will lead to immediate dismissal from event. Registrants dismissed from the event will not receive a refund. Please review the Terms and Conditions for more details.

Be aware that we recommend that all portable electronic devices be left at home, but ultimately it is your decision. We know that parents and children value the ability to be able to call each other at a moment's notice. For that reason, we do not prohibit cell phones at camp, but ask that cell phone use does not interfere with the event and other participants. Parents are responsible for setting clear guidelines for cell use with their child. We will not be responsible for any lost or stolen items.

Frequently Asked Questions

We receive many questions from registrants. Click here to review our frequently asked questions about registering and attending an event.

Special Notice

The University of Wisconsin-Whitewater is committed to equal opportunity in its educational programs, activities and employment policies, for all persons, regardless of race, color, gender, creed, religion, age, ancestry, national origin, disability, sexual orientation, political affiliation, marital status, Vietnam-era veteran status, parental status and pregnancy.

If you have any disabling condition that requires special accommodations or attention, please advise us well in advance. We will make every effort to accommodate your special needs.

By registering for this event you understand that the University may take photographs and/or videos of event participants and activities. You will be required to agree at the time of registration that the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater shall be the owner of and may use such photographs and/or videos relating to the promotion of future events. You will relinquish all rights that you may claim in relation to the use of said photographs and/or videos. Any media shared with the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater on social media or use of its hashtags grants the University use of media for any purpose.

Registrants are encouraged to have their own health insurance as accident insurance provided by the University is limited. Each registrant will be covered by a limited accident insurance policy. The insurance includes primary coverage up to $10,000. Insurance does not cover pre-existing injuries and is for accidents only. The cost of insurance is included in the registration fee.

- Event Schedule

- 2023 RESULTS

- 2022 RESULTS

- 2021 RESULTS

Best of the Festival

Children's literature.

Results will be posted after the event.

Meet the Staff

Nicholas Gulig Co-Director

Barrett Swanson Co-Director

More to Explore

Upcoming Events

Join Our Email List

Sponsor A Registrant

Music Events

Athletic Events

Programs for Adults

We use cookies on this site. By continuing to browse without changing your browser settings to block or delete cookies you agree to the UW-Whitewater Privacy Notice .

Ken Hada is a poet and professor at East Central University in Ada, Oklahoma where he directs the annual Scissortail Creative Writing Festival . Ken finds the natural order a powerful presence for writing. His work has received the 2022 Oklahoma Book Award, the 2017 SCMLA Poetry Prize, has been featured on The Writer’s Almanac , received the Western Heritage Award, named finalist for the Spur Award and six-time finalist for the Oklahoma Book Awards. In 2017 Ken gratefully accepted the Glenda Carlile Distinguished Service Award from the Oklahoma Center for the Book. His published poetry collections include: Come Before Winter , Feral Skies: Selected Poems 2008-2020, Contour Feathers, Sunlight & Cedar , Not Quite Pilgrims , Bring an Extry Mule , Persimmon Sunday , Spare Parts , Margaritas & Redfish , The Way of the Wind and The River White: A Confluence of Brush & Quill . Ken enjoys reading his work at venues around the country.

The Bert C. Bach Written Word Initiative

We sponsor programs related to literature and creative writing at etsu. we place an emphasis on events that benefit students, and we welcome our broader community of readers and writers from around the world. , enjoy these photos from our past events: the 2023 spring literary festival , the women of appalachia project "women speak" reading , and our 2023 young writers' workshop . follow the links to read more about these various projects and partnerships. .

Daniel Wallace reads from his memoir, This Isn't Going to End Well, for the Jack Higgs Memorial Reading at the 2023 Spring Literary Festival keynote address.

Visiting writers Annette Saunooke Clapsaddle, Adrienne Su, and Austin Bunn take questions from students and the community about writing and craft.

Annette Saunooke Clapsaddle reads from her novel, Even As We Breathe, and talks about fiction writing to the crowd.

Joshua Martin reads poetry as one of the presenters for the New Writing from ETSU session. He is a professor in the Department of Literature and Language.

Poet Adrienne Su reads from her book, Peach State.

Dr. Jesse Graves, ETSU's Poet-in-Residence and the Director of the Bert C. Bach Written Word Initiative, opens the two-day Spring Literary Festival.

Keynote speaker Daniel Wallace joins a roundtable discussion with Dr. Jesse Graves and Dr. Scott Honeycutt to discuss his new memoir, This Isn't Going to End Well, and the legacy of William Nealy.

A crowd fills the Reece Museum for the Keynote Address of the Spring Literary Festival, presented by author Daniel Wallace.

Readers during the Women of Appalachia Project "Women Speak" Event: Tina Parker, Jane Hicks, Rita Sims Quillen, Lisa J. Parker, Tamara Baxter, Dana Wildsmith, K.B. Ballentine, Catherine Pritchard Childress, Jessica Cory, Sue Weaver Dunlap, and Chrissie Anderson Peters. Kneeling are Lacy Snapp and Kari Gunter-Seymour.

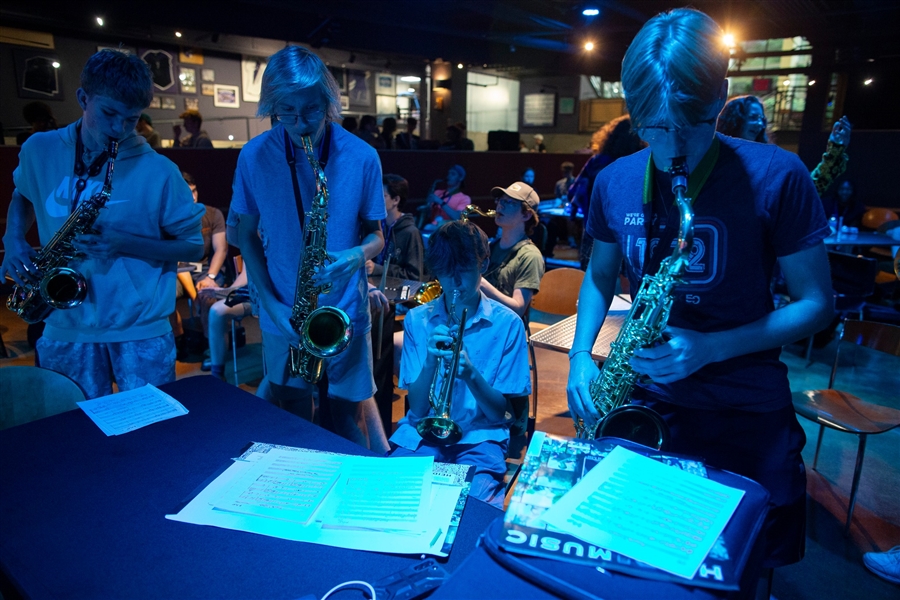

Kari Gunter-Seymour is the Poet Laureate of Ohio and the founder of the Women of Appalachia Project. Here, she holds up the 8th Volume of the "Women Speak" Anthology before the ETSU event.

Jane Hicks reads her poetry during the "Women Speak" event.

Tamara Baxter tells of her Appalachian heritage before reading her fiction piece from the "Women Speak" Anthology.

Dr. Jesse Graves, ETSU's Poet-in-Residence and the Director of the Bert C. Bach Written Word Initiative, Lacy Snapp, Assistant Director of the Bert C. Bach Written Word Initiative, and Kari Gunter-Seymour, Ohio's Poet Laureate and the Founder and Director of the Women of Appalachia Project, gather for a picture at the "Women Speak" ETSU reading.

Our 2024 Spring Literary Schedule is live! Start planning your trip now and reading up on our visiting writers and our keynote speaker, Rita Dove .

The 2023 Spring Literary Festival keynote speaker Daniel Wallace joins a roundtable discussion with Dr. Jesse Graves and Dr. Scott Honeycutt to discuss his new memoir, This Isn't Going to End Well, and the legacy of William Nealy.

Valencia Robin, Leah Naomi Green, and Lisa J. Parker spent the afternoon at ETSU for a roundtable discussion, poetry reading, and Q&A with students and the public for the 3 Emerging Writers' 2023 Event.

Poet-in-Residence Dr. Jesse Graves, 19th Poet Laureate of the United States Natasha Trethewey, and Basler Chair Amy Wright engage in a conversation about memoir during Trethewey's 2022 visit to campus. (from left to right)

Former Poet Laureate Charles Wright and Dr. Jesse Graves host a Q&A during Wright's 2017 visit to campus.

A crowd shot in the Reece Museum during former Poet Laureate Charles Wright's 2017 visit to campus.

Former Poet Laureate Joy Harjo plays a flute to open the Sixth Annual Robert "Jack" Higgs Memorial Reading in 2018.

A 2022 Young Writers' Workshop participant uses the visual prompt of art from the Reece Museum to inspire a poem.

Poet-in-Residence Dr. Jesse Graves, 19th Poet Laureate of the United States Natasha Trethewey, Director of the Black American Studies Program Daryl Carter, and Basler Chair Amy Wright (from left to right)

Author Lynn Powell joins Dr. Jesse Graves and students and faculty from the Literature and Language Department for a photo during her visit to campus in 2018.

A photo from the first Robert J. "Jack" Higgs Reading in 2013 featuring Jesse Graves, Art Smith, Marilyn Kallet, Catherine Pritchard Childress, Jack Higgs, and Thomas Alan Holmes.

Former Poet Laureate Natasha Trethewey reads from her memoir during her 2022 visit to ETSU.

Some of the 2022 Young Writers' Workshop staff from left to right: Madeline Rodenberg, Lacy Snapp, Stella Rodenberg, AK Stites, and Dr. Jesse Graves.

Founded in 2015, this ETSU initiative has helped to sponsor programs such as the Spring Literary Festival, the Fall Residency Readings, 3 Emerging Writers Events, the Young Writers' Workshop, and other partnership events over the past seven years.

The ETSU community was heartbroken to learn of the sudden passing of Dr. Bert C. Bach on August 14, 2023. Dr. Bach was a champion for the arts and especially for making them available to students. We will carry his name and his memory forward with us in all that we do with the Written Word Initiative.

Our history:

In September 2015, Dr. Bert C. Bach requested a meeting with English professor and Poet-in-Residence, Dr. Jesse Graves to discuss what kinds of support would most benefit students of writing at ETSU. Planning for events began immediately, resulting in the very first Spring Literary Festival the following semester in April 2016. The program has hosted some remarkable events through the first six years of the program, most that we would never have dreamed of without the BCB Initiative. We hosted US Poet Laureate and Pulitzer Prize-winning Kingsport, TN native Charles Wright in October 2017; future US Poet Laureate Joy Harjo in April 2018; Jefferson Award-winning novelist Silas House in April 2019, along with many other celebrated authors in those early years. The BCB has hosted dozens of writers since 2016, with many hundreds of students and community members in attendance, and has developed meaningful partnerships with organizations on campus and beyond. What began with Dr. Bach's question, "What do our writing students need?" has resulted in several ongoing programs, such as the annual Spring Literary Festival, Fall Residency, and 3 Emerging Writers series, alongside new partnerships like the Black American Writers' Series, the Young Writers' Workshop, and a continuing TEDxETSU license for the Creative Writing Society.

Dr. Bert C. Bach

Not quite a yummy mummy

Reviews, interviews and days out

Monday 14 April 2014

Interview with actress olivia hallinan, no comments:, post a comment.

CREEES Professional Resources Forum

Center for Russian, East European and Eurasian Studies at The University of Texas at Austin

Grad Program: MA in Creative Writing in Russian (Moscow)

Application opens February 2019

For fiction/non-fiction writers in Russian.

MA “Creative Writing” is:

- Practical and theoretical/historical courses, such as Creative Writing Workshop , Storytelling in Different Media , Literary Editing , Poetics of Novel and Screenwriting ;

- Unique professors and teachers, among them famous Russian writers, screenwriters and critics – Marina Stepnova , Lyudmila Ulitskaya , Lev Danilkin , Sergey Gandlevsky and Maya Kucherskaya as well as prominent philologists, authors of academic and non-fiction books Oleg Lekmanov , Ekaterina Lyamina and Alexey Vdovin ;

- Participation in open readings, discussions and literary expeditions , publications in students’ projects ;

- International exchange – lectures and workshops of the leading specialists in Creative Writing, students’ exchange in the best world universities;

- Help and support in the process of employment in various publishing houses, editorials, Mass Media, high schools and universities and PR;

- Creation and participation in cultural projects ;

- Flexible timetable enabling students to work while studying.

Our graduates already work in the best publishing houses, universities and schools in Moscow. Their writing is published in the authoritative literary magazines. Their projects (such as prize “_Litblog” for the best literary blogger and first Creative Writing Internet resource in Russian “Mnogobukv” and collections of prose) have gained much attention.

Language of instruction: Russian

You can apply to non-paid place as a foreign student in February. Looking forward to seeing you at Higher School of Economics!

More information about the programme: https://www.hse.ru/en/ma/litmaster

Greater Manchester to host UK’s first Muslim children's literary festival with Manga artists and Greek mythology experts

G reater Manchester will host the UK’s first ever literary festival for Muslim children - featuring well-known Manga artists and Greek mythology experts.

Sibgha: Literary Festival for Young Muslim Minds will take place at the European Islamic Centre in Oldham on Saturday (April 20) and will feature a day of creative writing workshops, storytelling readings and sessions with authors and artists from diverse backgrounds.

Aimed at children aged eight and above, the Sibgha festival is being held to promote diversity, inclusivity, and showcase how the power of literature can help to inspire and empower underrepresented young people.