Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Starting the research process

- How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

Published on October 12, 2022 by Shona McCombes and Tegan George. Revised on November 21, 2023.

A research proposal describes what you will investigate, why it’s important, and how you will conduct your research.

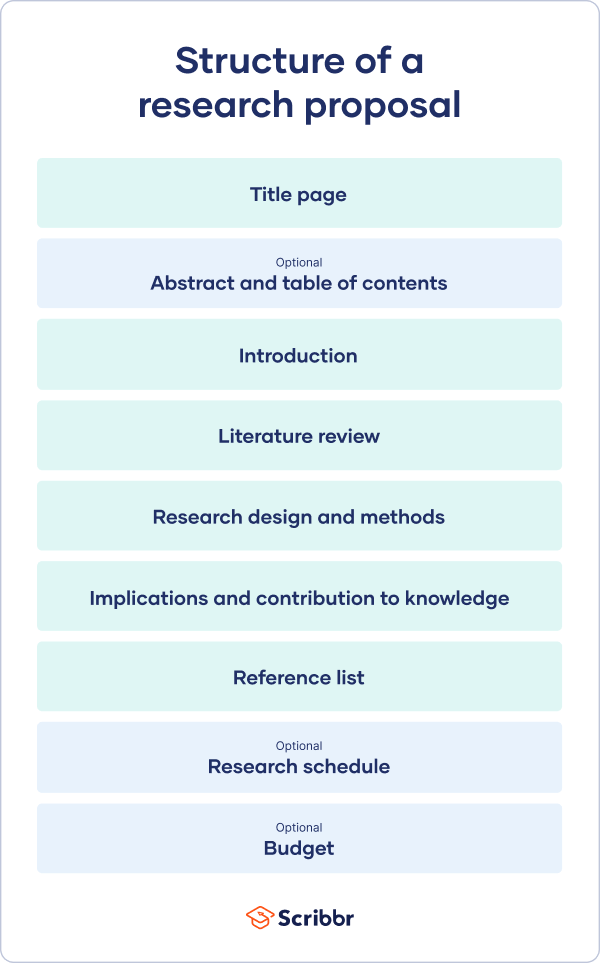

The format of a research proposal varies between fields, but most proposals will contain at least these elements:

Introduction

Literature review.

- Research design

Reference list

While the sections may vary, the overall objective is always the same. A research proposal serves as a blueprint and guide for your research plan, helping you get organized and feel confident in the path forward you choose to take.

Table of contents

Research proposal purpose, research proposal examples, research design and methods, contribution to knowledge, research schedule, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research proposals.

Academics often have to write research proposals to get funding for their projects. As a student, you might have to write a research proposal as part of a grad school application , or prior to starting your thesis or dissertation .

In addition to helping you figure out what your research can look like, a proposal can also serve to demonstrate why your project is worth pursuing to a funder, educational institution, or supervisor.

| Show your reader why your project is interesting, original, and important. | |

| Demonstrate your comfort and familiarity with your field. Show that you understand the current state of research on your topic. | |

| Make a case for your . Demonstrate that you have carefully thought about the data, tools, and procedures necessary to conduct your research. | |

| Confirm that your project is feasible within the timeline of your program or funding deadline. |

Research proposal length

The length of a research proposal can vary quite a bit. A bachelor’s or master’s thesis proposal can be just a few pages, while proposals for PhD dissertations or research funding are usually much longer and more detailed. Your supervisor can help you determine the best length for your work.

One trick to get started is to think of your proposal’s structure as a shorter version of your thesis or dissertation , only without the results , conclusion and discussion sections.

Download our research proposal template

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Writing a research proposal can be quite challenging, but a good starting point could be to look at some examples. We’ve included a few for you below.

- Example research proposal #1: “A Conceptual Framework for Scheduling Constraint Management”

- Example research proposal #2: “Medical Students as Mediators of Change in Tobacco Use”

Like your dissertation or thesis, the proposal will usually have a title page that includes:

- The proposed title of your project

- Your supervisor’s name

- Your institution and department

The first part of your proposal is the initial pitch for your project. Make sure it succinctly explains what you want to do and why.

Your introduction should:

- Introduce your topic

- Give necessary background and context

- Outline your problem statement and research questions

To guide your introduction , include information about:

- Who could have an interest in the topic (e.g., scientists, policymakers)

- How much is already known about the topic

- What is missing from this current knowledge

- What new insights your research will contribute

- Why you believe this research is worth doing

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

As you get started, it’s important to demonstrate that you’re familiar with the most important research on your topic. A strong literature review shows your reader that your project has a solid foundation in existing knowledge or theory. It also shows that you’re not simply repeating what other people have already done or said, but rather using existing research as a jumping-off point for your own.

In this section, share exactly how your project will contribute to ongoing conversations in the field by:

- Comparing and contrasting the main theories, methods, and debates

- Examining the strengths and weaknesses of different approaches

- Explaining how will you build on, challenge, or synthesize prior scholarship

Following the literature review, restate your main objectives . This brings the focus back to your own project. Next, your research design or methodology section will describe your overall approach, and the practical steps you will take to answer your research questions.

| ? or ? , , or research design? | |

| , )? ? | |

| , , , )? | |

| ? |

To finish your proposal on a strong note, explore the potential implications of your research for your field. Emphasize again what you aim to contribute and why it matters.

For example, your results might have implications for:

- Improving best practices

- Informing policymaking decisions

- Strengthening a theory or model

- Challenging popular or scientific beliefs

- Creating a basis for future research

Last but not least, your research proposal must include correct citations for every source you have used, compiled in a reference list . To create citations quickly and easily, you can use our free APA citation generator .

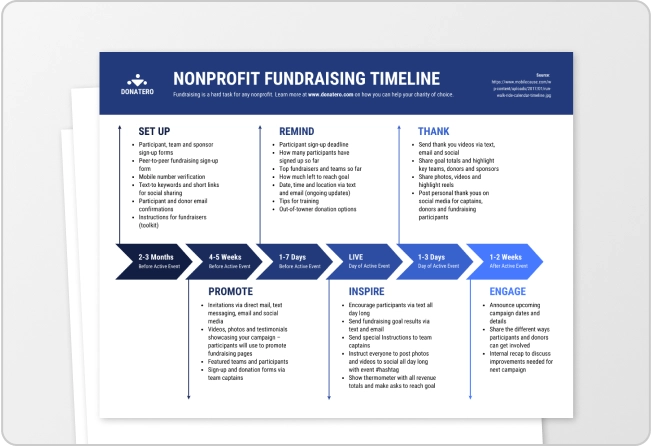

Some institutions or funders require a detailed timeline of the project, asking you to forecast what you will do at each stage and how long it may take. While not always required, be sure to check the requirements of your project.

Here’s an example schedule to help you get started. You can also download a template at the button below.

Download our research schedule template

| Research phase | Objectives | Deadline |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Background research and literature review | 20th January | |

| 2. Research design planning | and data analysis methods | 13th February |

| 3. Data collection and preparation | with selected participants and code interviews | 24th March |

| 4. Data analysis | of interview transcripts | 22nd April |

| 5. Writing | 17th June | |

| 6. Revision | final work | 28th July |

If you are applying for research funding, chances are you will have to include a detailed budget. This shows your estimates of how much each part of your project will cost.

Make sure to check what type of costs the funding body will agree to cover. For each item, include:

- Cost : exactly how much money do you need?

- Justification : why is this cost necessary to complete the research?

- Source : how did you calculate the amount?

To determine your budget, think about:

- Travel costs : do you need to go somewhere to collect your data? How will you get there, and how much time will you need? What will you do there (e.g., interviews, archival research)?

- Materials : do you need access to any tools or technologies?

- Help : do you need to hire any research assistants for the project? What will they do, and how much will you pay them?

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Methodology

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

Once you’ve decided on your research objectives , you need to explain them in your paper, at the end of your problem statement .

Keep your research objectives clear and concise, and use appropriate verbs to accurately convey the work that you will carry out for each one.

I will compare …

A research aim is a broad statement indicating the general purpose of your research project. It should appear in your introduction at the end of your problem statement , before your research objectives.

Research objectives are more specific than your research aim. They indicate the specific ways you’ll address the overarching aim.

A PhD, which is short for philosophiae doctor (doctor of philosophy in Latin), is the highest university degree that can be obtained. In a PhD, students spend 3–5 years writing a dissertation , which aims to make a significant, original contribution to current knowledge.

A PhD is intended to prepare students for a career as a researcher, whether that be in academia, the public sector, or the private sector.

A master’s is a 1- or 2-year graduate degree that can prepare you for a variety of careers.

All master’s involve graduate-level coursework. Some are research-intensive and intend to prepare students for further study in a PhD; these usually require their students to write a master’s thesis . Others focus on professional training for a specific career.

Critical thinking refers to the ability to evaluate information and to be aware of biases or assumptions, including your own.

Like information literacy , it involves evaluating arguments, identifying and solving problems in an objective and systematic way, and clearly communicating your ideas.

The best way to remember the difference between a research plan and a research proposal is that they have fundamentally different audiences. A research plan helps you, the researcher, organize your thoughts. On the other hand, a dissertation proposal or research proposal aims to convince others (e.g., a supervisor, a funding body, or a dissertation committee) that your research topic is relevant and worthy of being conducted.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. & George, T. (2023, November 21). How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved June 27, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-process/research-proposal/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a problem statement | guide & examples, writing strong research questions | criteria & examples, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, what is your plagiarism score.

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

The goal of a research proposal is twofold: to present and justify the need to study a research problem and to present the practical ways in which the proposed study should be conducted. The design elements and procedures for conducting research are governed by standards of the predominant discipline in which the problem resides, therefore, the guidelines for research proposals are more exacting and less formal than a general project proposal. Research proposals contain extensive literature reviews. They must provide persuasive evidence that a need exists for the proposed study. In addition to providing a rationale, a proposal describes detailed methodology for conducting the research consistent with requirements of the professional or academic field and a statement on anticipated outcomes and benefits derived from the study's completion.

Krathwohl, David R. How to Prepare a Dissertation Proposal: Suggestions for Students in Education and the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2005.

How to Approach Writing a Research Proposal

Your professor may assign the task of writing a research proposal for the following reasons:

- Develop your skills in thinking about and designing a comprehensive research study;

- Learn how to conduct a comprehensive review of the literature to determine that the research problem has not been adequately addressed or has been answered ineffectively and, in so doing, become better at locating pertinent scholarship related to your topic;

- Improve your general research and writing skills;

- Practice identifying the logical steps that must be taken to accomplish one's research goals;

- Critically review, examine, and consider the use of different methods for gathering and analyzing data related to the research problem; and,

- Nurture a sense of inquisitiveness within yourself and to help see yourself as an active participant in the process of conducting scholarly research.

A proposal should contain all the key elements involved in designing a completed research study, with sufficient information that allows readers to assess the validity and usefulness of your proposed study. The only elements missing from a research proposal are the findings of the study and your analysis of those findings. Finally, an effective proposal is judged on the quality of your writing and, therefore, it is important that your proposal is coherent, clear, and compelling.

Regardless of the research problem you are investigating and the methodology you choose, all research proposals must address the following questions:

- What do you plan to accomplish? Be clear and succinct in defining the research problem and what it is you are proposing to investigate.

- Why do you want to do the research? In addition to detailing your research design, you also must conduct a thorough review of the literature and provide convincing evidence that it is a topic worthy of in-depth study. A successful research proposal must answer the "So What?" question.

- How are you going to conduct the research? Be sure that what you propose is doable. If you're having difficulty formulating a research problem to propose investigating, go here for strategies in developing a problem to study.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Failure to be concise . A research proposal must be focused and not be "all over the map" or diverge into unrelated tangents without a clear sense of purpose.

- Failure to cite landmark works in your literature review . Proposals should be grounded in foundational research that lays a foundation for understanding the development and scope of the the topic and its relevance.

- Failure to delimit the contextual scope of your research [e.g., time, place, people, etc.]. As with any research paper, your proposed study must inform the reader how and in what ways the study will frame the problem.

- Failure to develop a coherent and persuasive argument for the proposed research . This is critical. In many workplace settings, the research proposal is a formal document intended to argue for why a study should be funded.

- Sloppy or imprecise writing, or poor grammar . Although a research proposal does not represent a completed research study, there is still an expectation that it is well-written and follows the style and rules of good academic writing.

- Too much detail on minor issues, but not enough detail on major issues . Your proposal should focus on only a few key research questions in order to support the argument that the research needs to be conducted. Minor issues, even if valid, can be mentioned but they should not dominate the overall narrative.

Procter, Margaret. The Academic Proposal. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Sanford, Keith. Information for Students: Writing a Research Proposal. Baylor University; Wong, Paul T. P. How to Write a Research Proposal. International Network on Personal Meaning. Trinity Western University; Writing Academic Proposals: Conferences, Articles, and Books. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing a Research Proposal. University Library. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Structure and Writing Style

Beginning the Proposal Process

As with writing most college-level academic papers, research proposals are generally organized the same way throughout most social science disciplines. The text of proposals generally vary in length between ten and thirty-five pages, followed by the list of references. However, before you begin, read the assignment carefully and, if anything seems unclear, ask your professor whether there are any specific requirements for organizing and writing the proposal.

A good place to begin is to ask yourself a series of questions:

- What do I want to study?

- Why is the topic important?

- How is it significant within the subject areas covered in my class?

- What problems will it help solve?

- How does it build upon [and hopefully go beyond] research already conducted on the topic?

- What exactly should I plan to do, and can I get it done in the time available?

In general, a compelling research proposal should document your knowledge of the topic and demonstrate your enthusiasm for conducting the study. Approach it with the intention of leaving your readers feeling like, "Wow, that's an exciting idea and I can’t wait to see how it turns out!"

Most proposals should include the following sections:

I. Introduction

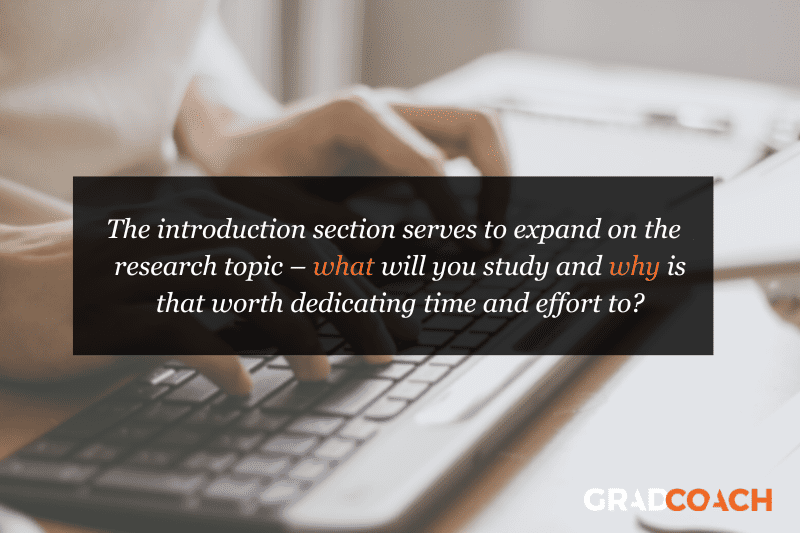

In the real world of higher education, a research proposal is most often written by scholars seeking grant funding for a research project or it's the first step in getting approval to write a doctoral dissertation. Even if this is just a course assignment, treat your introduction as the initial pitch of an idea based on a thorough examination of the significance of a research problem. After reading the introduction, your readers should not only have an understanding of what you want to do, but they should also be able to gain a sense of your passion for the topic and to be excited about the study's possible outcomes. Note that most proposals do not include an abstract [summary] before the introduction.

Think about your introduction as a narrative written in two to four paragraphs that succinctly answers the following four questions :

- What is the central research problem?

- What is the topic of study related to that research problem?

- What methods should be used to analyze the research problem?

- Answer the "So What?" question by explaining why this is important research, what is its significance, and why should someone reading the proposal care about the outcomes of the proposed study?

II. Background and Significance

This is where you explain the scope and context of your proposal and describe in detail why it's important. It can be melded into your introduction or you can create a separate section to help with the organization and narrative flow of your proposal. Approach writing this section with the thought that you can’t assume your readers will know as much about the research problem as you do. Note that this section is not an essay going over everything you have learned about the topic; instead, you must choose what is most relevant in explaining the aims of your research.

To that end, while there are no prescribed rules for establishing the significance of your proposed study, you should attempt to address some or all of the following:

- State the research problem and give a more detailed explanation about the purpose of the study than what you stated in the introduction. This is particularly important if the problem is complex or multifaceted .

- Present the rationale of your proposed study and clearly indicate why it is worth doing; be sure to answer the "So What? question [i.e., why should anyone care?].

- Describe the major issues or problems examined by your research. This can be in the form of questions to be addressed. Be sure to note how your proposed study builds on previous assumptions about the research problem.

- Explain the methods you plan to use for conducting your research. Clearly identify the key sources you intend to use and explain how they will contribute to your analysis of the topic.

- Describe the boundaries of your proposed research in order to provide a clear focus. Where appropriate, state not only what you plan to study, but what aspects of the research problem will be excluded from the study.

- If necessary, provide definitions of key concepts, theories, or terms.

III. Literature Review

Connected to the background and significance of your study is a section of your proposal devoted to a more deliberate review and synthesis of prior studies related to the research problem under investigation . The purpose here is to place your project within the larger whole of what is currently being explored, while at the same time, demonstrating to your readers that your work is original and innovative. Think about what questions other researchers have asked, what methodological approaches they have used, and what is your understanding of their findings and, when stated, their recommendations. Also pay attention to any suggestions for further research.

Since a literature review is information dense, it is crucial that this section is intelligently structured to enable a reader to grasp the key arguments underpinning your proposed study in relation to the arguments put forth by other researchers. A good strategy is to break the literature into "conceptual categories" [themes] rather than systematically or chronologically describing groups of materials one at a time. Note that conceptual categories generally reveal themselves after you have read most of the pertinent literature on your topic so adding new categories is an on-going process of discovery as you review more studies. How do you know you've covered the key conceptual categories underlying the research literature? Generally, you can have confidence that all of the significant conceptual categories have been identified if you start to see repetition in the conclusions or recommendations that are being made.

NOTE: Do not shy away from challenging the conclusions made in prior research as a basis for supporting the need for your proposal. Assess what you believe is missing and state how previous research has failed to adequately examine the issue that your study addresses. Highlighting the problematic conclusions strengthens your proposal. For more information on writing literature reviews, GO HERE .

To help frame your proposal's review of prior research, consider the "five C’s" of writing a literature review:

- Cite , so as to keep the primary focus on the literature pertinent to your research problem.

- Compare the various arguments, theories, methodologies, and findings expressed in the literature: what do the authors agree on? Who applies similar approaches to analyzing the research problem?

- Contrast the various arguments, themes, methodologies, approaches, and controversies expressed in the literature: describe what are the major areas of disagreement, controversy, or debate among scholars?

- Critique the literature: Which arguments are more persuasive, and why? Which approaches, findings, and methodologies seem most reliable, valid, or appropriate, and why? Pay attention to the verbs you use to describe what an author says/does [e.g., asserts, demonstrates, argues, etc.].

- Connect the literature to your own area of research and investigation: how does your own work draw upon, depart from, synthesize, or add a new perspective to what has been said in the literature?

IV. Research Design and Methods

This section must be well-written and logically organized because you are not actually doing the research, yet, your reader must have confidence that you have a plan worth pursuing . The reader will never have a study outcome from which to evaluate whether your methodological choices were the correct ones. Thus, the objective here is to convince the reader that your overall research design and proposed methods of analysis will correctly address the problem and that the methods will provide the means to effectively interpret the potential results. Your design and methods should be unmistakably tied to the specific aims of your study.

Describe the overall research design by building upon and drawing examples from your review of the literature. Consider not only methods that other researchers have used, but methods of data gathering that have not been used but perhaps could be. Be specific about the methodological approaches you plan to undertake to obtain information, the techniques you would use to analyze the data, and the tests of external validity to which you commit yourself [i.e., the trustworthiness by which you can generalize from your study to other people, places, events, and/or periods of time].

When describing the methods you will use, be sure to cover the following:

- Specify the research process you will undertake and the way you will interpret the results obtained in relation to the research problem. Don't just describe what you intend to achieve from applying the methods you choose, but state how you will spend your time while applying these methods [e.g., coding text from interviews to find statements about the need to change school curriculum; running a regression to determine if there is a relationship between campaign advertising on social media sites and election outcomes in Europe ].

- Keep in mind that the methodology is not just a list of tasks; it is a deliberate argument as to why techniques for gathering information add up to the best way to investigate the research problem. This is an important point because the mere listing of tasks to be performed does not demonstrate that, collectively, they effectively address the research problem. Be sure you clearly explain this.

- Anticipate and acknowledge any potential barriers and pitfalls in carrying out your research design and explain how you plan to address them. No method applied to research in the social and behavioral sciences is perfect, so you need to describe where you believe challenges may exist in obtaining data or accessing information. It's always better to acknowledge this than to have it brought up by your professor!

V. Preliminary Suppositions and Implications

Just because you don't have to actually conduct the study and analyze the results, doesn't mean you can skip talking about the analytical process and potential implications . The purpose of this section is to argue how and in what ways you believe your research will refine, revise, or extend existing knowledge in the subject area under investigation. Depending on the aims and objectives of your study, describe how the anticipated results will impact future scholarly research, theory, practice, forms of interventions, or policy making. Note that such discussions may have either substantive [a potential new policy], theoretical [a potential new understanding], or methodological [a potential new way of analyzing] significance. When thinking about the potential implications of your study, ask the following questions:

- What might the results mean in regards to challenging the theoretical framework and underlying assumptions that support the study?

- What suggestions for subsequent research could arise from the potential outcomes of the study?

- What will the results mean to practitioners in the natural settings of their workplace, organization, or community?

- Will the results influence programs, methods, and/or forms of intervention?

- How might the results contribute to the solution of social, economic, or other types of problems?

- Will the results influence policy decisions?

- In what way do individuals or groups benefit should your study be pursued?

- What will be improved or changed as a result of the proposed research?

- How will the results of the study be implemented and what innovations or transformative insights could emerge from the process of implementation?

NOTE: This section should not delve into idle speculation, opinion, or be formulated on the basis of unclear evidence . The purpose is to reflect upon gaps or understudied areas of the current literature and describe how your proposed research contributes to a new understanding of the research problem should the study be implemented as designed.

ANOTHER NOTE : This section is also where you describe any potential limitations to your proposed study. While it is impossible to highlight all potential limitations because the study has yet to be conducted, you still must tell the reader where and in what form impediments may arise and how you plan to address them.

VI. Conclusion

The conclusion reiterates the importance or significance of your proposal and provides a brief summary of the entire study . This section should be only one or two paragraphs long, emphasizing why the research problem is worth investigating, why your research study is unique, and how it should advance existing knowledge.

Someone reading this section should come away with an understanding of:

- Why the study should be done;

- The specific purpose of the study and the research questions it attempts to answer;

- The decision for why the research design and methods used where chosen over other options;

- The potential implications emerging from your proposed study of the research problem; and

- A sense of how your study fits within the broader scholarship about the research problem.

VII. Citations

As with any scholarly research paper, you must cite the sources you used . In a standard research proposal, this section can take two forms, so consult with your professor about which one is preferred.

- References -- a list of only the sources you actually used in creating your proposal.

- Bibliography -- a list of everything you used in creating your proposal, along with additional citations to any key sources relevant to understanding the research problem.

In either case, this section should testify to the fact that you did enough preparatory work to ensure the project will complement and not just duplicate the efforts of other researchers. It demonstrates to the reader that you have a thorough understanding of prior research on the topic.

Most proposal formats have you start a new page and use the heading "References" or "Bibliography" centered at the top of the page. Cited works should always use a standard format that follows the writing style advised by the discipline of your course [e.g., education=APA; history=Chicago] or that is preferred by your professor. This section normally does not count towards the total page length of your research proposal.

Develop a Research Proposal: Writing the Proposal. Office of Library Information Services. Baltimore County Public Schools; Heath, M. Teresa Pereira and Caroline Tynan. “Crafting a Research Proposal.” The Marketing Review 10 (Summer 2010): 147-168; Jones, Mark. “Writing a Research Proposal.” In MasterClass in Geography Education: Transforming Teaching and Learning . Graham Butt, editor. (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015), pp. 113-127; Juni, Muhamad Hanafiah. “Writing a Research Proposal.” International Journal of Public Health and Clinical Sciences 1 (September/October 2014): 229-240; Krathwohl, David R. How to Prepare a Dissertation Proposal: Suggestions for Students in Education and the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2005; Procter, Margaret. The Academic Proposal. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Punch, Keith and Wayne McGowan. "Developing and Writing a Research Proposal." In From Postgraduate to Social Scientist: A Guide to Key Skills . Nigel Gilbert, ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2006), 59-81; Wong, Paul T. P. How to Write a Research Proposal. International Network on Personal Meaning. Trinity Western University; Writing Academic Proposals: Conferences , Articles, and Books. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing a Research Proposal. University Library. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

- << Previous: Writing a Reflective Paper

- Next: Generative AI and Writing >>

- Last Updated: Jun 3, 2024 9:44 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to write a research proposal

What is a research proposal?

What is the purpose of a research proposal , how long should a research proposal be, what should be included in a research proposal, 1. the title page, 2. introduction, 3. literature review, 4. research design, 5. implications, 6. reference list, frequently asked questions about writing a research proposal, related articles.

If you’re in higher education, the term “research proposal” is something you’re likely to be familiar with. But what is it, exactly? You’ll normally come across the need to prepare a research proposal when you’re looking to secure Ph.D. funding.

When you’re trying to find someone to fund your Ph.D. research, a research proposal is essentially your “pitch.”

A research proposal is a concise and coherent summary of your proposed research.

You’ll need to set out the issues that are central to the topic area and how you intend to address them with your research. To do this, you’ll need to give the following:

- an outline of the general area of study within which your research falls

- an overview of how much is currently known about the topic

- a literature review that covers the recent scholarly debate or conversation around the topic

➡️ What is a literature review? Learn more in our guide.

Essentially, you are trying to persuade your institution that you and your project are worth investing their time and money into.

It is the opportunity for you to demonstrate that you have the aptitude for this level of research by showing that you can articulate complex ideas:

It also helps you to find the right supervisor to oversee your research. When you’re writing your research proposal, you should always have this in the back of your mind.

This is the document that potential supervisors will use in determining the legitimacy of your research and, consequently, whether they will invest in you or not. It is therefore incredibly important that you spend some time on getting it right.

Tip: While there may not always be length requirements for research proposals, you should strive to cover everything you need to in a concise way.

If your research proposal is for a bachelor’s or master’s degree, it may only be a few pages long. For a Ph.D., a proposal could be a pretty long document that spans a few dozen pages.

➡️ Research proposals are similar to grant proposals. Learn how to write a grant proposal in our guide.

When you’re writing your proposal, keep in mind its purpose and why you’re writing it. It, therefore, needs to clearly explain the relevance of your research and its context with other discussions on the topic. You need to then explain what approach you will take and why it is feasible.

Generally, your structure should look something like this:

- Introduction

- Literature Review

- Research Design

- Implications

If you follow this structure, you’ll have a comprehensive and coherent proposal that looks and feels professional, without missing out on anything important. We’ll take a deep dive into each of these areas one by one next.

The title page might vary slightly per your area of study but, as a general point, your title page should contain the following:

- The proposed title of your project

- Your supervisor’s name

- The name of your institution and your particular department

Tip: Keep in mind any departmental or institutional guidelines for a research proposal title page. Also, your supervisor may ask for specific details to be added to the page.

The introduction is crucial to your research proposal as it is your first opportunity to hook the reader in. A good introduction section will introduce your project and its relevance to the field of study.

You’ll want to use this space to demonstrate that you have carefully thought about how to present your project as interesting, original, and important research. A good place to start is by introducing the context of your research problem.

Think about answering these questions:

- What is it you want to research and why?

- How does this research relate to the respective field?

- How much is already known about this area?

- Who might find this research interesting?

- What are the key questions you aim to answer with your research?

- What will the findings of this project add to the topic area?

Your introduction aims to set yourself off on a great footing and illustrate to the reader that you are an expert in your field and that your project has a solid foundation in existing knowledge and theory.

The literature review section answers the question who else is talking about your proposed research topic.

You want to demonstrate that your research will contribute to conversations around the topic and that it will sit happily amongst experts in the field.

➡️ Read more about how to write a literature review .

There are lots of ways you can find relevant information for your literature review, including:

- Research relevant academic sources such as books and journals to find similar conversations around the topic.

- Read through abstracts and bibliographies of your academic sources to look for relevance and further additional resources without delving too deep into articles that are possibly not relevant to you.

- Watch out for heavily-cited works . This should help you to identify authoritative work that you need to read and document.

- Look for any research gaps , trends and patterns, common themes, debates, and contradictions.

- Consider any seminal studies on the topic area as it is likely anticipated that you will address these in your research proposal.

This is where you get down to the real meat of your research proposal. It should be a discussion about the overall approach you plan on taking, and the practical steps you’ll follow in answering the research questions you’ve posed.

So what should you discuss here? Some of the key things you will need to discuss at this point are:

- What form will your research take? Is it qualitative/quantitative/mixed? Will your research be primary or secondary?

- What sources will you use? Who or what will you be studying as part of your research.

- Document your research method. How are you practically going to carry out your research? What tools will you need? What procedures will you use?

- Any practicality issues you foresee. Do you think there will be any obstacles to your anticipated timescale? What resources will you require in carrying out your research?

Your research design should also discuss the potential implications of your research. For example, are you looking to confirm an existing theory or develop a new one?

If you intend to create a basis for further research, you should describe this here.

It is important to explain fully what you want the outcome of your research to look like and what you want to achieve by it. This will help those reading your research proposal to decide if it’s something the field needs and wants, and ultimately whether they will support you with it.

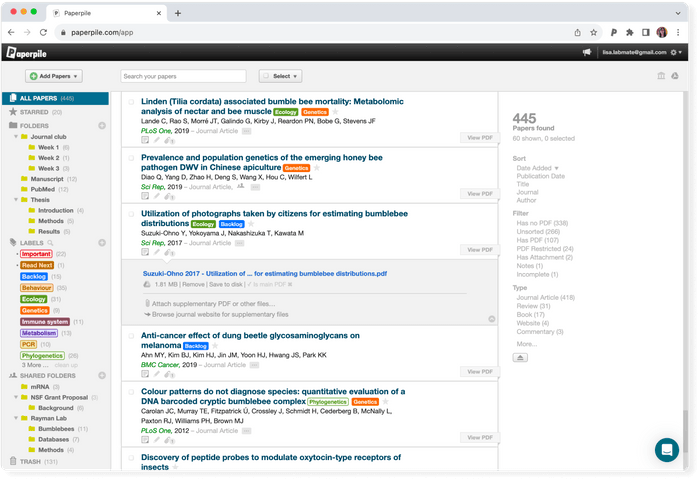

When you reach the end of your research proposal, you’ll have to compile a list of references for everything you’ve cited above. Ideally, you should keep track of everything from the beginning. Otherwise, this could be a mammoth and pretty laborious task to do.

Consider using a reference manager like Paperpile to format and organize your citations. Paperpile allows you to organize and save your citations for later use and cite them in thousands of citation styles directly in Google Docs, Microsoft Word, or LaTeX.

Your project may also require you to have a timeline, depending on the budget you are requesting. If you need one, you should include it here and explain both the timeline and the budget you need, documenting what should be done at each stage of the research and how much of the budget this will use.

This is the final step, but not one to be missed. You should make sure that you edit and proofread your document so that you can be sure there are no mistakes.

A good idea is to have another person proofread the document for you so that you get a fresh pair of eyes on it. You can even have a professional proofreader do this for you.

This is an important document and you don’t want spelling or grammatical mistakes to get in the way of you and your reader.

➡️ Working on a research proposal for a thesis? Take a look at our guide on how to come up with a topic for your thesis .

A research proposal is a concise and coherent summary of your proposed research. Generally, your research proposal will have a title page, introduction, literature review section, a section about research design and explaining the implications of your research, and a reference list.

A good research proposal is concise and coherent. It has a clear purpose, clearly explains the relevance of your research and its context with other discussions on the topic. A good research proposal explains what approach you will take and why it is feasible.

You need a research proposal to persuade your institution that you and your project are worth investing their time and money into. It is your opportunity to demonstrate your aptitude for this level or research by showing that you can articulate complex ideas clearly, concisely, and critically.

A research proposal is essentially your "pitch" when you're trying to find someone to fund your PhD. It is a clear and concise summary of your proposed research. It gives an outline of the general area of study within which your research falls, it elaborates how much is currently known about the topic, and it highlights any recent debate or conversation around the topic by other academics.

The general answer is: as long as it needs to be to cover everything. The length of your research proposal depends on the requirements from the institution that you are applying to. Make sure to carefully read all the instructions given, and if this specific information is not provided, you can always ask.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

What is a research proposal?

A research proposal is a type of text which maps out a proposed central research problem or question and a suggested approach to its investigation.

In many universities, including RMIT, the research proposal is a formal requirement. It is central to achieving your first milestone: your Confirmation of Candidature. The research proposal is useful for both you and the University: it gives you the opportunity to get valuable feedback about your intended research aims, objectives and design. It also confirms that your proposed research is worth doing, which puts you on track for a successful candidature supported by your School and the University.

Although there may be specific School or disciplinary requirements that you need to be aware of, all research proposals address the following central themes:

- what you propose to research

- why the topic needs to be researched

- how you plan to research it.

Purpose and audience

Before venturing into writing a research purposal, it is important to think about the purpose and audience of this type of text. Spend a moment or two to reflect on what these might be.

What do you think is the purpose of your research proposal and who is your audience?

The purpose of your research proposal is:

1. To allow experienced researchers (your supervisors and their peers) to assess whether

- the research question or problem is viable (that is, answers or solutions are possible)

- the research is worth doing in terms of its contribution to the field of study and benefits to stakeholders

- the scope is appropriate to the degree (Masters or PhD)

- you’ve understood the relevant key literature and identified the gap for your research

- you’ve chosen an appropriate methodological approach.

2. To help you clarify and focus on what you want to do, why you want to do it, and how you’ll do it. The research proposal helps you position yourself as a researcher in your field. It will also allow you to:

- systematically think through your proposed research, argue for its significance and identify the scope

- show a critical understanding of the scholarly field around your proposed research

- show the gap in the literature that your research will address

- justify your proposed research design

- identify all tasks that need to be done through a realistic timetable

- anticipate potential problems

- hone organisational skills that you will need for your research

- become familiar with relevant search engines and databases

- develop skills in research writing.

The main audience for your research proposal is your reviewers. Universities usually assign a panel of reviewers to which you need to submit your research proposal. Often this is within the first year of study for PhD candidates, and within the first six months for Masters by Research candidates.

Your reviewers may have a strong disciplinary understanding of the area of your proposed research, but depending on your specialisation, they may not. It is therefore important to create a clear context, rationale and framework for your proposed research. Limit jargon and specialist terminology so that non-specialists can comprehend it. You need to convince the reviewers that your proposed research is worth doing and that you will be able to effectively ‘interrogate’ your research questions or address the research problems through your chosen research design.

Your review panel will expect you to demonstrate:

- a clearly defined and feasible research project

- a clearly explained rationale for your research

- evidence that your research will make an original contribution through a critical review of the literature

- written skills appropriate to graduate research study.

Research and Writing Skills for Academic and Graduate Researchers Copyright © 2022 by RMIT University is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

How To Write A Research Proposal

A Straightforward How-To Guide (With Examples)

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | August 2019 (Updated April 2023)

Writing up a strong research proposal for a dissertation or thesis is much like a marriage proposal. It’s a task that calls on you to win somebody over and persuade them that what you’re planning is a great idea. An idea they’re happy to say ‘yes’ to. This means that your dissertation proposal needs to be persuasive , attractive and well-planned. In this post, I’ll show you how to write a winning dissertation proposal, from scratch.

Before you start:

– Understand exactly what a research proposal is – Ask yourself these 4 questions

The 5 essential ingredients:

- The title/topic

- The introduction chapter

- The scope/delimitations

- Preliminary literature review

- Design/ methodology

- Practical considerations and risks

What Is A Research Proposal?

The research proposal is literally that: a written document that communicates what you propose to research, in a concise format. It’s where you put all that stuff that’s spinning around in your head down on to paper, in a logical, convincing fashion.

Convincing is the keyword here, as your research proposal needs to convince the assessor that your research is clearly articulated (i.e., a clear research question) , worth doing (i.e., is unique and valuable enough to justify the effort), and doable within the restrictions you’ll face (time limits, budget, skill limits, etc.). If your proposal does not address these three criteria, your research won’t be approved, no matter how “exciting” the research idea might be.

PS – if you’re completely new to proposal writing, we’ve got a detailed walkthrough video covering two successful research proposals here .

How do I know I’m ready?

Before starting the writing process, you need to ask yourself 4 important questions . If you can’t answer them succinctly and confidently, you’re not ready – you need to go back and think more deeply about your dissertation topic .

You should be able to answer the following 4 questions before starting your dissertation or thesis research proposal:

- WHAT is my main research question? (the topic)

- WHO cares and why is this important? (the justification)

- WHAT data would I need to answer this question, and how will I analyse it? (the research design)

- HOW will I manage the completion of this research, within the given timelines? (project and risk management)

If you can’t answer these questions clearly and concisely, you’re not yet ready to write your research proposal – revisit our post on choosing a topic .

If you can, that’s great – it’s time to start writing up your dissertation proposal. Next, I’ll discuss what needs to go into your research proposal, and how to structure it all into an intuitive, convincing document with a linear narrative.

The 5 Essential Ingredients

Research proposals can vary in style between institutions and disciplines, but here I’ll share with you a handy 5-section structure you can use. These 5 sections directly address the core questions we spoke about earlier, ensuring that you present a convincing proposal. If your institution already provides a proposal template, there will likely be substantial overlap with this, so you’ll still get value from reading on.

For each section discussed below, make sure you use headers and sub-headers (ideally, numbered headers) to help the reader navigate through your document, and to support them when they need to revisit a previous section. Don’t just present an endless wall of text, paragraph after paragraph after paragraph…

Top Tip: Use MS Word Styles to format headings. This will allow you to be clear about whether a sub-heading is level 2, 3, or 4. Additionally, you can view your document in ‘outline view’ which will show you only your headings. This makes it much easier to check your structure, shift things around and make decisions about where a section needs to sit. You can also generate a 100% accurate table of contents using Word’s automatic functionality.

Ingredient #1 – Topic/Title Header

Your research proposal’s title should be your main research question in its simplest form, possibly with a sub-heading providing basic details on the specifics of the study. For example:

“Compliance with equality legislation in the charity sector: a study of the ‘reasonable adjustments’ made in three London care homes”

As you can see, this title provides a clear indication of what the research is about, in broad terms. It paints a high-level picture for the first-time reader, which gives them a taste of what to expect. Always aim for a clear, concise title . Don’t feel the need to capture every detail of your research in your title – your proposal will fill in the gaps.

Need a helping hand?

Ingredient #2 – Introduction

In this section of your research proposal, you’ll expand on what you’ve communicated in the title, by providing a few paragraphs which offer more detail about your research topic. Importantly, the focus here is the topic – what will you research and why is that worth researching? This is not the place to discuss methodology, practicalities, etc. – you’ll do that later.

You should cover the following:

- An overview of the broad area you’ll be researching – introduce the reader to key concepts and language

- An explanation of the specific (narrower) area you’ll be focusing, and why you’ll be focusing there

- Your research aims and objectives

- Your research question (s) and sub-questions (if applicable)

Importantly, you should aim to use short sentences and plain language – don’t babble on with extensive jargon, acronyms and complex language. Assume that the reader is an intelligent layman – not a subject area specialist (even if they are). Remember that the best writing is writing that can be easily understood and digested. Keep it simple.

Note that some universities may want some extra bits and pieces in your introduction section. For example, personal development objectives, a structural outline, etc. Check your brief to see if there are any other details they expect in your proposal, and make sure you find a place for these.

Ingredient #3 – Scope

Next, you’ll need to specify what the scope of your research will be – this is also known as the delimitations . In other words, you need to make it clear what you will be covering and, more importantly, what you won’t be covering in your research. Simply put, this is about ring fencing your research topic so that you have a laser-sharp focus.

All too often, students feel the need to go broad and try to address as many issues as possible, in the interest of producing comprehensive research. Whilst this is admirable, it’s a mistake. By tightly refining your scope, you’ll enable yourself to go deep with your research, which is what you need to earn good marks. If your scope is too broad, you’re likely going to land up with superficial research (which won’t earn marks), so don’t be afraid to narrow things down.

Ingredient #4 – Literature Review

In this section of your research proposal, you need to provide a (relatively) brief discussion of the existing literature. Naturally, this will not be as comprehensive as the literature review in your actual dissertation, but it will lay the foundation for that. In fact, if you put in the effort at this stage, you’ll make your life a lot easier when it’s time to write your actual literature review chapter.

There are a few things you need to achieve in this section:

- Demonstrate that you’ve done your reading and are familiar with the current state of the research in your topic area.

- Show that there’s a clear gap for your specific research – i.e., show that your topic is sufficiently unique and will add value to the existing research.

- Show how the existing research has shaped your thinking regarding research design . For example, you might use scales or questionnaires from previous studies.

When you write up your literature review, keep these three objectives front of mind, especially number two (revealing the gap in the literature), so that your literature review has a clear purpose and direction . Everything you write should be contributing towards one (or more) of these objectives in some way. If it doesn’t, you need to ask yourself whether it’s truly needed.

Top Tip: Don’t fall into the trap of just describing the main pieces of literature, for example, “A says this, B says that, C also says that…” and so on. Merely describing the literature provides no value. Instead, you need to synthesise it, and use it to address the three objectives above.

Ingredient #5 – Research Methodology

Now that you’ve clearly explained both your intended research topic (in the introduction) and the existing research it will draw on (in the literature review section), it’s time to get practical and explain exactly how you’ll be carrying out your own research. In other words, your research methodology.

In this section, you’ll need to answer two critical questions :

- How will you design your research? I.e., what research methodology will you adopt, what will your sample be, how will you collect data, etc.

- Why have you chosen this design? I.e., why does this approach suit your specific research aims, objectives and questions?

In other words, this is not just about explaining WHAT you’ll be doing, it’s also about explaining WHY. In fact, the justification is the most important part , because that justification is how you demonstrate a good understanding of research design (which is what assessors want to see).

Some essential design choices you need to cover in your research proposal include:

- Your intended research philosophy (e.g., positivism, interpretivism or pragmatism )

- What methodological approach you’ll be taking (e.g., qualitative , quantitative or mixed )

- The details of your sample (e.g., sample size, who they are, who they represent, etc.)

- What data you plan to collect (i.e. data about what, in what form?)

- How you plan to collect it (e.g., surveys , interviews , focus groups, etc.)

- How you plan to analyse it (e.g., regression analysis, thematic analysis , etc.)

- Ethical adherence (i.e., does this research satisfy all ethical requirements of your institution, or does it need further approval?)

This list is not exhaustive – these are just some core attributes of research design. Check with your institution what level of detail they expect. The “ research onion ” by Saunders et al (2009) provides a good summary of the various design choices you ultimately need to make – you can read more about that here .

Don’t forget the practicalities…

In addition to the technical aspects, you will need to address the practical side of the project. In other words, you need to explain what resources you’ll need (e.g., time, money, access to equipment or software, etc.) and how you intend to secure these resources. You need to show that your project is feasible, so any “make or break” type resources need to already be secured. The success or failure of your project cannot depend on some resource which you’re not yet sure you have access to.

Another part of the practicalities discussion is project and risk management . In other words, you need to show that you have a clear project plan to tackle your research with. Some key questions to address:

- What are the timelines for each phase of your project?

- Are the time allocations reasonable?

- What happens if something takes longer than anticipated (risk management)?

- What happens if you don’t get the response rate you expect?

A good way to demonstrate that you’ve thought this through is to include a Gantt chart and a risk register (in the appendix if word count is a problem). With these two tools, you can show that you’ve got a clear, feasible plan, and you’ve thought about and accounted for the potential risks.

Tip – Be honest about the potential difficulties – but show that you are anticipating solutions and workarounds. This is much more impressive to an assessor than an unrealistically optimistic proposal which does not anticipate any challenges whatsoever.

Final Touches: Read And Simplify

The final step is to edit and proofread your proposal – very carefully. It sounds obvious, but all too often poor editing and proofreading ruin a good proposal. Nothing is more off-putting for an assessor than a poorly edited, typo-strewn document. It sends the message that you either do not pay attention to detail, or just don’t care. Neither of these are good messages. Put the effort into editing and proofreading your proposal (or pay someone to do it for you) – it will pay dividends.

When you’re editing, watch out for ‘academese’. Many students can speak simply, passionately and clearly about their dissertation topic – but become incomprehensible the moment they turn the laptop on. You are not required to write in any kind of special, formal, complex language when you write academic work. Sure, there may be technical terms, jargon specific to your discipline, shorthand terms and so on. But, apart from those, keep your written language very close to natural spoken language – just as you would speak in the classroom. Imagine that you are explaining your project plans to your classmates or a family member. Remember, write for the intelligent layman, not the subject matter experts. Plain-language, concise writing is what wins hearts and minds – and marks!

Let’s Recap: Research Proposal 101

And there you have it – how to write your dissertation or thesis research proposal, from the title page to the final proof. Here’s a quick recap of the key takeaways:

- The purpose of the research proposal is to convince – therefore, you need to make a clear, concise argument of why your research is both worth doing and doable.

- Make sure you can ask the critical what, who, and how questions of your research before you put pen to paper.

- Title – provides the first taste of your research, in broad terms

- Introduction – explains what you’ll be researching in more detail

- Scope – explains the boundaries of your research

- Literature review – explains how your research fits into the existing research and why it’s unique and valuable

- Research methodology – explains and justifies how you will carry out your own research

Hopefully, this post has helped you better understand how to write up a winning research proposal. If you enjoyed it, be sure to check out the rest of the Grad Coach Blog . If your university doesn’t provide any template for your proposal, you might want to try out our free research proposal template .

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Research Proposal Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

30 Comments

Thank you so much for the valuable insight that you have given, especially on the research proposal. That is what I have managed to cover. I still need to go back to the other parts as I got disturbed while still listening to Derek’s audio on you-tube. I am inspired. I will definitely continue with Grad-coach guidance on You-tube.

Thanks for the kind words :). All the best with your proposal.

First of all, thanks a lot for making such a wonderful presentation. The video was really useful and gave me a very clear insight of how a research proposal has to be written. I shall try implementing these ideas in my RP.

Once again, I thank you for this content.

I found reading your outline on writing research proposal very beneficial. I wish there was a way of submitting my draft proposal to you guys for critiquing before I submit to the institution.

Hi Bonginkosi

Thank you for the kind words. Yes, we do provide a review service. The best starting point is to have a chat with one of our coaches here: https://gradcoach.com/book/new/ .

Hello team GRADCOACH, may God bless you so much. I was totally green in research. Am so happy for your free superb tutorials and resources. Once again thank you so much Derek and his team.

You’re welcome, Erick. Good luck with your research proposal 🙂

thank you for the information. its precise and on point.

Really a remarkable piece of writing and great source of guidance for the researchers. GOD BLESS YOU for your guidance. Regards

Thanks so much for your guidance. It is easy and comprehensive the way you explain the steps for a winning research proposal.

Thank you guys so much for the rich post. I enjoyed and learn from every word in it. My problem now is how to get into your platform wherein I can always seek help on things related to my research work ? Secondly, I wish to find out if there is a way I can send my tentative proposal to you guys for examination before I take to my supervisor Once again thanks very much for the insights

Thanks for your kind words, Desire.

If you are based in a country where Grad Coach’s paid services are available, you can book a consultation by clicking the “Book” button in the top right.

Best of luck with your studies.

May God bless you team for the wonderful work you are doing,

If I have a topic, Can I submit it to you so that you can draft a proposal for me?? As I am expecting to go for masters degree in the near future.

Thanks for your comment. We definitely cannot draft a proposal for you, as that would constitute academic misconduct. The proposal needs to be your own work. We can coach you through the process, but it needs to be your own work and your own writing.

Best of luck with your research!

I found a lot of many essential concepts from your material. it is real a road map to write a research proposal. so thanks a lot. If there is any update material on your hand on MBA please forward to me.

GradCoach is a professional website that presents support and helps for MBA student like me through the useful online information on the page and with my 1-on-1 online coaching with the amazing and professional PhD Kerryen.

Thank you Kerryen so much for the support and help 🙂

I really recommend dealing with such a reliable services provider like Gradcoah and a coach like Kerryen.

Hi, Am happy for your service and effort to help students and researchers, Please, i have been given an assignment on research for strategic development, the task one is to formulate a research proposal to support the strategic development of a business area, my issue here is how to go about it, especially the topic or title and introduction. Please, i would like to know if you could help me and how much is the charge.

This content is practical, valuable, and just great!

Thank you very much!

Hi Derek, Thank you for the valuable presentation. It is very helpful especially for beginners like me. I am just starting my PhD.

This is quite instructive and research proposal made simple. Can I have a research proposal template?

Great! Thanks for rescuing me, because I had no former knowledge in this topic. But with this piece of information, I am now secured. Thank you once more.

I enjoyed listening to your video on how to write a proposal. I think I will be able to write a winning proposal with your advice. I wish you were to be my supervisor.

Dear Derek Jansen,

Thank you for your great content. I couldn’t learn these topics in MBA, but now I learned from GradCoach. Really appreciate your efforts….

From Afghanistan!

I have got very essential inputs for startup of my dissertation proposal. Well organized properly communicated with video presentation. Thank you for the presentation.

Wow, this is absolutely amazing guys. Thank you so much for the fruitful presentation, you’ve made my research much easier.

this helps me a lot. thank you all so much for impacting in us. may god richly bless you all

How I wish I’d learn about Grad Coach earlier. I’ve been stumbling around writing and rewriting! Now I have concise clear directions on how to put this thing together. Thank you!

Fantastic!! Thank You for this very concise yet comprehensive guidance.

Even if I am poor in English I would like to thank you very much.

Thank you very much, this is very insightful.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Indian J Anaesth

- v.60(9); 2016 Sep

How to write a research proposal?

Department of Anaesthesiology, Bangalore Medical College and Research Institute, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

Devika Rani Duggappa

Writing the proposal of a research work in the present era is a challenging task due to the constantly evolving trends in the qualitative research design and the need to incorporate medical advances into the methodology. The proposal is a detailed plan or ‘blueprint’ for the intended study, and once it is completed, the research project should flow smoothly. Even today, many of the proposals at post-graduate evaluation committees and application proposals for funding are substandard. A search was conducted with keywords such as research proposal, writing proposal and qualitative using search engines, namely, PubMed and Google Scholar, and an attempt has been made to provide broad guidelines for writing a scientifically appropriate research proposal.

INTRODUCTION

A clean, well-thought-out proposal forms the backbone for the research itself and hence becomes the most important step in the process of conduct of research.[ 1 ] The objective of preparing a research proposal would be to obtain approvals from various committees including ethics committee [details under ‘Research methodology II’ section [ Table 1 ] in this issue of IJA) and to request for grants. However, there are very few universally accepted guidelines for preparation of a good quality research proposal. A search was performed with keywords such as research proposal, funding, qualitative and writing proposals using search engines, namely, PubMed, Google Scholar and Scopus.

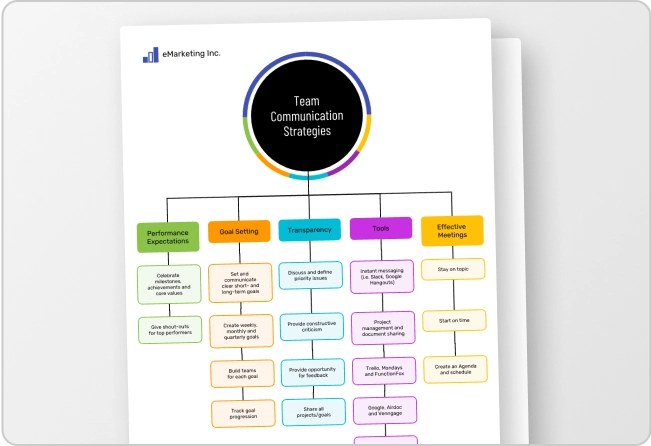

Five ‘C’s while writing a literature review

BASIC REQUIREMENTS OF A RESEARCH PROPOSAL

A proposal needs to show how your work fits into what is already known about the topic and what new paradigm will it add to the literature, while specifying the question that the research will answer, establishing its significance, and the implications of the answer.[ 2 ] The proposal must be capable of convincing the evaluation committee about the credibility, achievability, practicality and reproducibility (repeatability) of the research design.[ 3 ] Four categories of audience with different expectations may be present in the evaluation committees, namely academic colleagues, policy-makers, practitioners and lay audiences who evaluate the research proposal. Tips for preparation of a good research proposal include; ‘be practical, be persuasive, make broader links, aim for crystal clarity and plan before you write’. A researcher must be balanced, with a realistic understanding of what can be achieved. Being persuasive implies that researcher must be able to convince other researchers, research funding agencies, educational institutions and supervisors that the research is worth getting approval. The aim of the researcher should be clearly stated in simple language that describes the research in a way that non-specialists can comprehend, without use of jargons. The proposal must not only demonstrate that it is based on an intelligent understanding of the existing literature but also show that the writer has thought about the time needed to conduct each stage of the research.[ 4 , 5 ]

CONTENTS OF A RESEARCH PROPOSAL

The contents or formats of a research proposal vary depending on the requirements of evaluation committee and are generally provided by the evaluation committee or the institution.

In general, a cover page should contain the (i) title of the proposal, (ii) name and affiliation of the researcher (principal investigator) and co-investigators, (iii) institutional affiliation (degree of the investigator and the name of institution where the study will be performed), details of contact such as phone numbers, E-mail id's and lines for signatures of investigators.

The main contents of the proposal may be presented under the following headings: (i) introduction, (ii) review of literature, (iii) aims and objectives, (iv) research design and methods, (v) ethical considerations, (vi) budget, (vii) appendices and (viii) citations.[ 4 ]

Introduction

It is also sometimes termed as ‘need for study’ or ‘abstract’. Introduction is an initial pitch of an idea; it sets the scene and puts the research in context.[ 6 ] The introduction should be designed to create interest in the reader about the topic and proposal. It should convey to the reader, what you want to do, what necessitates the study and your passion for the topic.[ 7 ] Some questions that can be used to assess the significance of the study are: (i) Who has an interest in the domain of inquiry? (ii) What do we already know about the topic? (iii) What has not been answered adequately in previous research and practice? (iv) How will this research add to knowledge, practice and policy in this area? Some of the evaluation committees, expect the last two questions, elaborated under a separate heading of ‘background and significance’.[ 8 ] Introduction should also contain the hypothesis behind the research design. If hypothesis cannot be constructed, the line of inquiry to be used in the research must be indicated.

Review of literature

It refers to all sources of scientific evidence pertaining to the topic in interest. In the present era of digitalisation and easy accessibility, there is an enormous amount of relevant data available, making it a challenge for the researcher to include all of it in his/her review.[ 9 ] It is crucial to structure this section intelligently so that the reader can grasp the argument related to your study in relation to that of other researchers, while still demonstrating to your readers that your work is original and innovative. It is preferable to summarise each article in a paragraph, highlighting the details pertinent to the topic of interest. The progression of review can move from the more general to the more focused studies, or a historical progression can be used to develop the story, without making it exhaustive.[ 1 ] Literature should include supporting data, disagreements and controversies. Five ‘C's may be kept in mind while writing a literature review[ 10 ] [ Table 1 ].

Aims and objectives

The research purpose (or goal or aim) gives a broad indication of what the researcher wishes to achieve in the research. The hypothesis to be tested can be the aim of the study. The objectives related to parameters or tools used to achieve the aim are generally categorised as primary and secondary objectives.

Research design and method

The objective here is to convince the reader that the overall research design and methods of analysis will correctly address the research problem and to impress upon the reader that the methodology/sources chosen are appropriate for the specific topic. It should be unmistakably tied to the specific aims of your study.

In this section, the methods and sources used to conduct the research must be discussed, including specific references to sites, databases, key texts or authors that will be indispensable to the project. There should be specific mention about the methodological approaches to be undertaken to gather information, about the techniques to be used to analyse it and about the tests of external validity to which researcher is committed.[ 10 , 11 ]

The components of this section include the following:[ 4 ]

Population and sample

Population refers to all the elements (individuals, objects or substances) that meet certain criteria for inclusion in a given universe,[ 12 ] and sample refers to subset of population which meets the inclusion criteria for enrolment into the study. The inclusion and exclusion criteria should be clearly defined. The details pertaining to sample size are discussed in the article “Sample size calculation: Basic priniciples” published in this issue of IJA.

Data collection

The researcher is expected to give a detailed account of the methodology adopted for collection of data, which include the time frame required for the research. The methodology should be tested for its validity and ensure that, in pursuit of achieving the results, the participant's life is not jeopardised. The author should anticipate and acknowledge any potential barrier and pitfall in carrying out the research design and explain plans to address them, thereby avoiding lacunae due to incomplete data collection. If the researcher is planning to acquire data through interviews or questionnaires, copy of the questions used for the same should be attached as an annexure with the proposal.

Rigor (soundness of the research)

This addresses the strength of the research with respect to its neutrality, consistency and applicability. Rigor must be reflected throughout the proposal.

It refers to the robustness of a research method against bias. The author should convey the measures taken to avoid bias, viz. blinding and randomisation, in an elaborate way, thus ensuring that the result obtained from the adopted method is purely as chance and not influenced by other confounding variables.

Consistency

Consistency considers whether the findings will be consistent if the inquiry was replicated with the same participants and in a similar context. This can be achieved by adopting standard and universally accepted methods and scales.

Applicability

Applicability refers to the degree to which the findings can be applied to different contexts and groups.[ 13 ]

Data analysis