Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 25 June 2022

Investigating the association between infertility and psychological distress using Australian Longitudinal Study on Women's Health (ALSWH)

- Tanmay Bagade ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2536-2537 1 ,

- Kailash Thapaliya ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2897-6844 1 , 3 ,

- Erica Breuer ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0952-6650 1 ,

- Rashmi Kamath ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4350-3586 2 ,

- Zhuoyang Li ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7622-150X 1 ,

- Elizabeth Sullivan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8718-2753 1 &

- Tazeen Majeed ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8512-3901 1

Scientific Reports volume 12 , Article number: 10808 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

4689 Accesses

4 Citations

28 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Epidemiology

- Health care

- Risk factors

Infertility affects millions of people globally. Although an estimated 1 in 6 couples in Australia are unable to conceive without medical intervention, little is known about the mental health impacts of infertility. This study investigated how infertility impacts the mental health of women. The study used nationally representative Australian Longitudinal Study on Women's Health (ALSWH) data. We analysed data from survey periods 2–8 conducted every three years between 2000 and 2018 for 6582 women born in 1973–78. We used a Generalised Equation Modelling (GEE) method to investigate the association of primary, secondary and resolved fertility status and psychological distress over time. Multiple measures were used to measure psychological distress: the (1) the mental health index subscale of the 36-item short form survey (SF-36), (2) the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CESD-10), (3) the Goldberg Anxiety and Depression Scale (GADanx) anxiety subscale; and a (4) composite psychological distress variable. About a third (30%) of women reported infertility at any of the survey rounds; a steady increase over 18 years from 1.7% at round 2 to 19.3% at round 8. Half of the women reporting primary or secondary infertility reported psychological distress, with the odds of having psychological distress was higher in women reporting primary (odds ratio (OR) 1.24, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.06–1.45), secondary (OR 1.27, 95% CI 1.10–1.46) or resolved infertility (OR 1.15, 95% CI 1.05–1.26) compared to women reporting normal fertility status. Women with partners, underweight or higher BMI, smoking, and high-risk alcohol use had higher odds of psychological distress, whereas women in paid work had significantly lower odds of psychological distress ( p < 0.001). Diabetes, high blood pressure, asthma, and other chronic physical illness were independently associated with higher odds of psychological distress. Infertility has a significant impact on mental health even after it is resolved. Frequent mental health assessment and a holistic approach to address the lifestyle factors should be undertaken during the treatment of infertility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Depressive symptoms, anxiety, and quality of life of Japanese women at initiation of ART treatment

The associations between infertility-related stress, family adaptability and family cohesion in infertile couples.

Spouse’s coping strategies mediate the relationship between women’s coping strategies and their psychological health among infertile couples

Introduction.

In 2018, an estimated 49–180 million couples globally were suffering from infertility 1 , defined by the World Health Organisation as a disease that affects the couple's inability to achieve conception despite regular and unprotected intercourse for over 12 months 2 . The estimated Global Burden of Disease due to female and male infertility has increased since 1990 3 . The global age-standardised Disability Adjusted Life Years due to female infertility increased by 15.83% from 1990 to 2017, compared to an 8.84% increase in male infertility 3 . In developed countries, infertility prevalence is 15% 4 , whereas, in Australia, the prevalence is estimated to be 17% for women aged between 28 and 33 years 5 . While the prevalence is unknown in the First Nations people of Australia, Gilbert et al. noted a higher incidence of risk factors associated with infertility 6 . Despite having a higher total fertility rate, the First Nations people in Australia may be disproportionately affected by infertility 6 .

Infertility is defined as primary when a pregnancy is never achieved or secondary when a minimum of one pregnancy is attained, but the individuals have difficulties achieving another conception 2 . It may take several years for couples with infertility to achieve a healthy full-term pregnancy, and some do not achieve this even with intervention 7 . Individuals often only seek infertility-related services when they strongly feel that embracing parenthood is a required social role for them at that stage of their life; therefore, the individual's definition of infertility might be different from what is understood in the literature 8 .

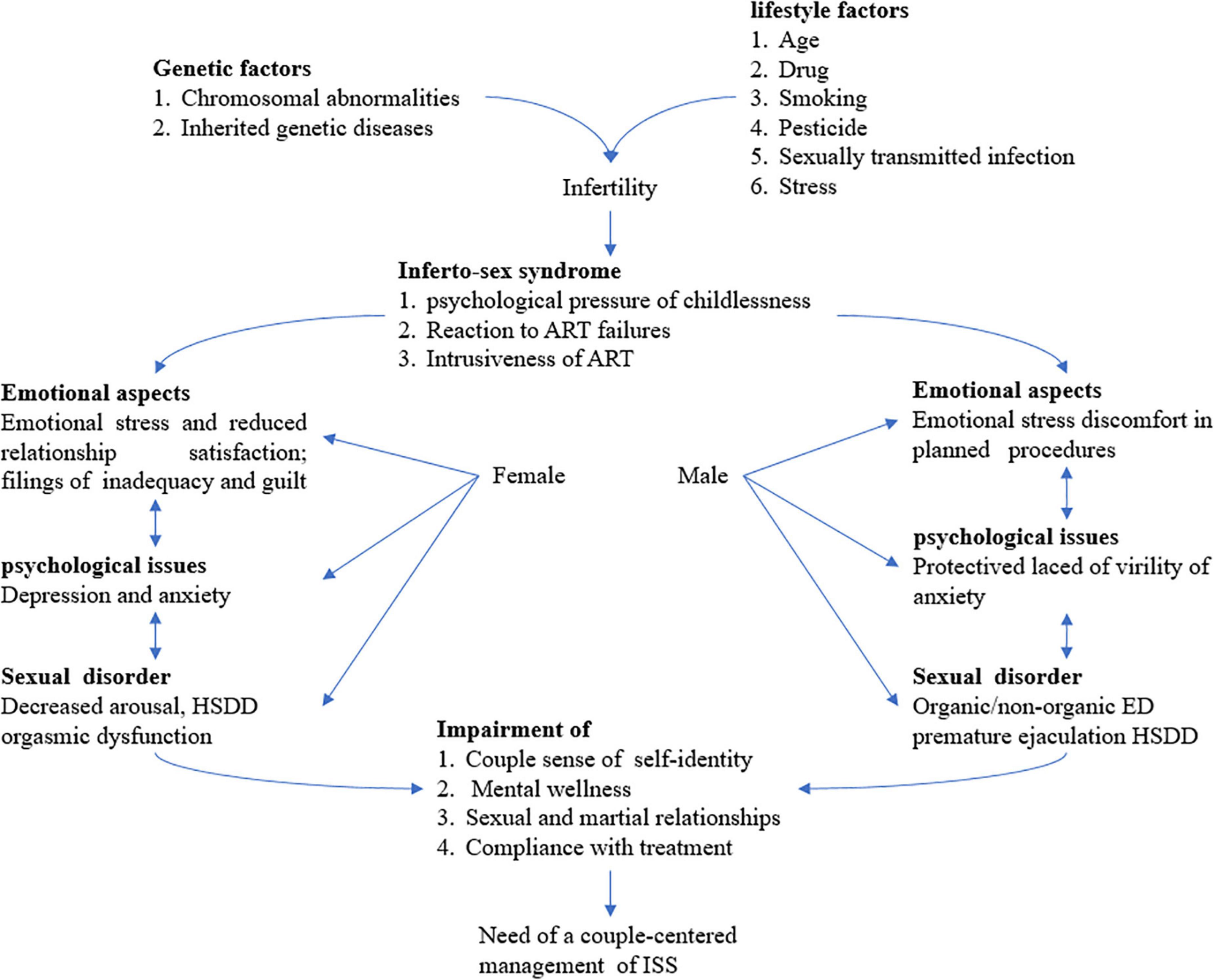

The process of conceiving and having a healthy child can be a challenging and stressful journey, which can further make the individuals feel powerless 9 . A systematic review on quality of life in infertility patients revealed that individuals could spend an average of 8.22 years with infertility 10 . Individuals scored significantly lower on mental health, social functioning and emotional behaviour and failed treatment was associated with lower quality of life 10 . Jacob et al. reported that women seeking infertility treatment show a 16% higher level of psychological distress than those without infertility 11 . Likewise, several other studies conducted in the USA, Finland, Norway have shown an association between infertility and adverse mental health outcomes 12 , 13 , 14 . Berg and Wilson summarised the cluster of anxiety, irritability, depression, blaming the self, lethargy, loneliness, and vulnerability as common infertility-related mental health symptoms 15 . The psychological effects of infertility are not limited to short-term impacts but can affect the long-term mental health and wellbeing of couples. Although infertility can also result in poor mental health outcomes among men 16 , women often experience more psychological distress over time 17 . Women who elect not to have children or are childless due to fertility issues reported poorer social wellbeing and emotional health than the overall female population of Australia 18 , 19 , 20 .

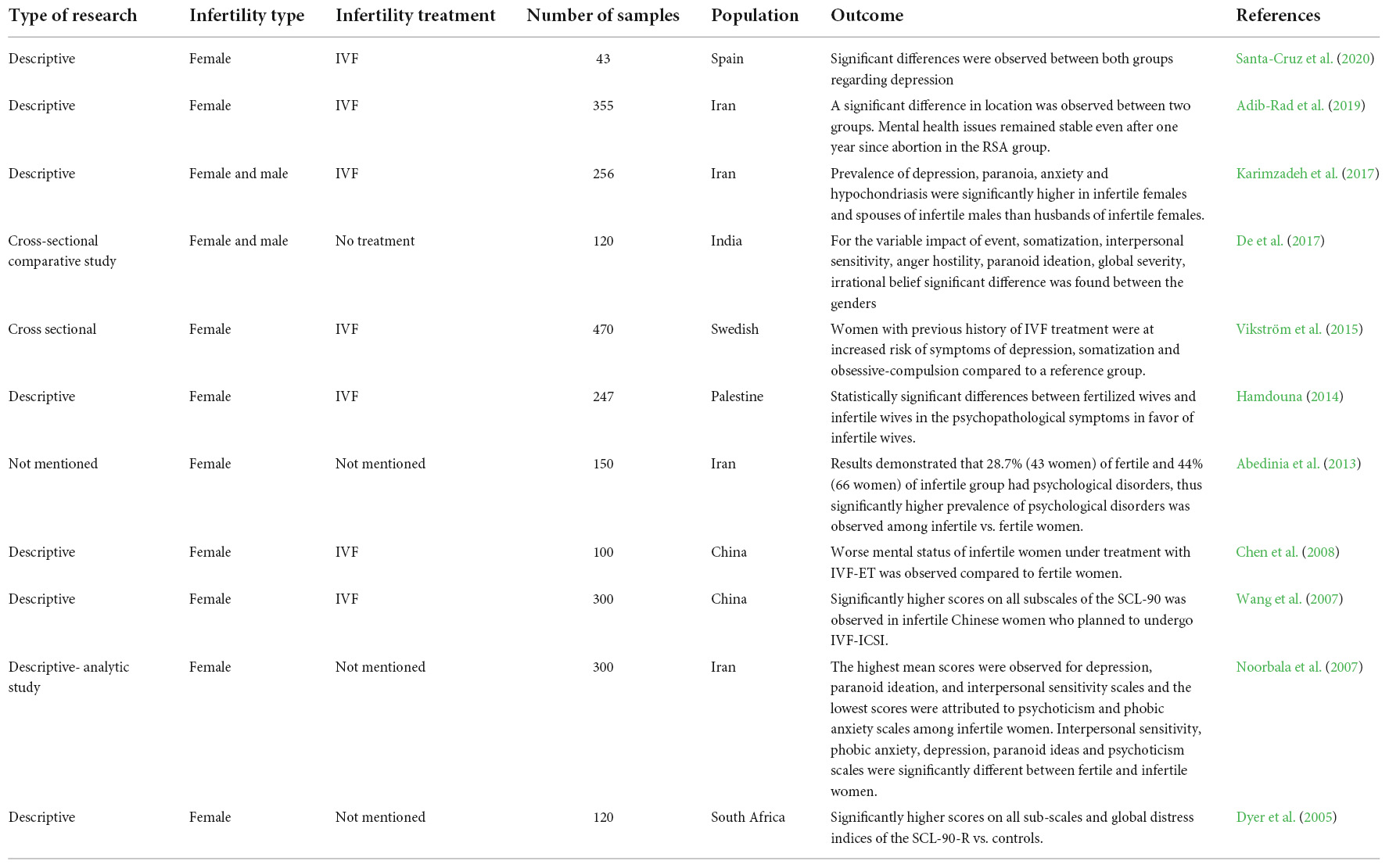

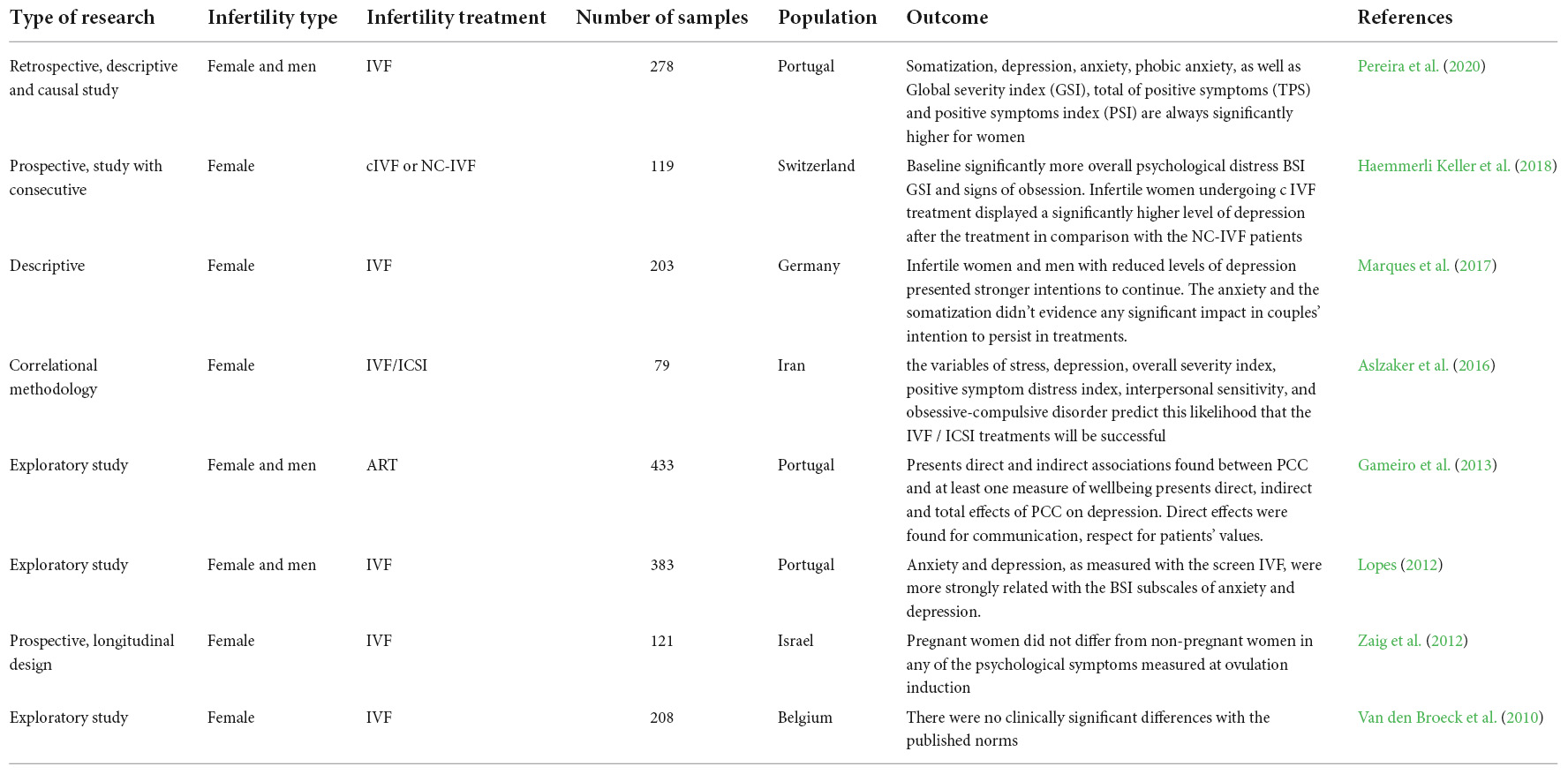

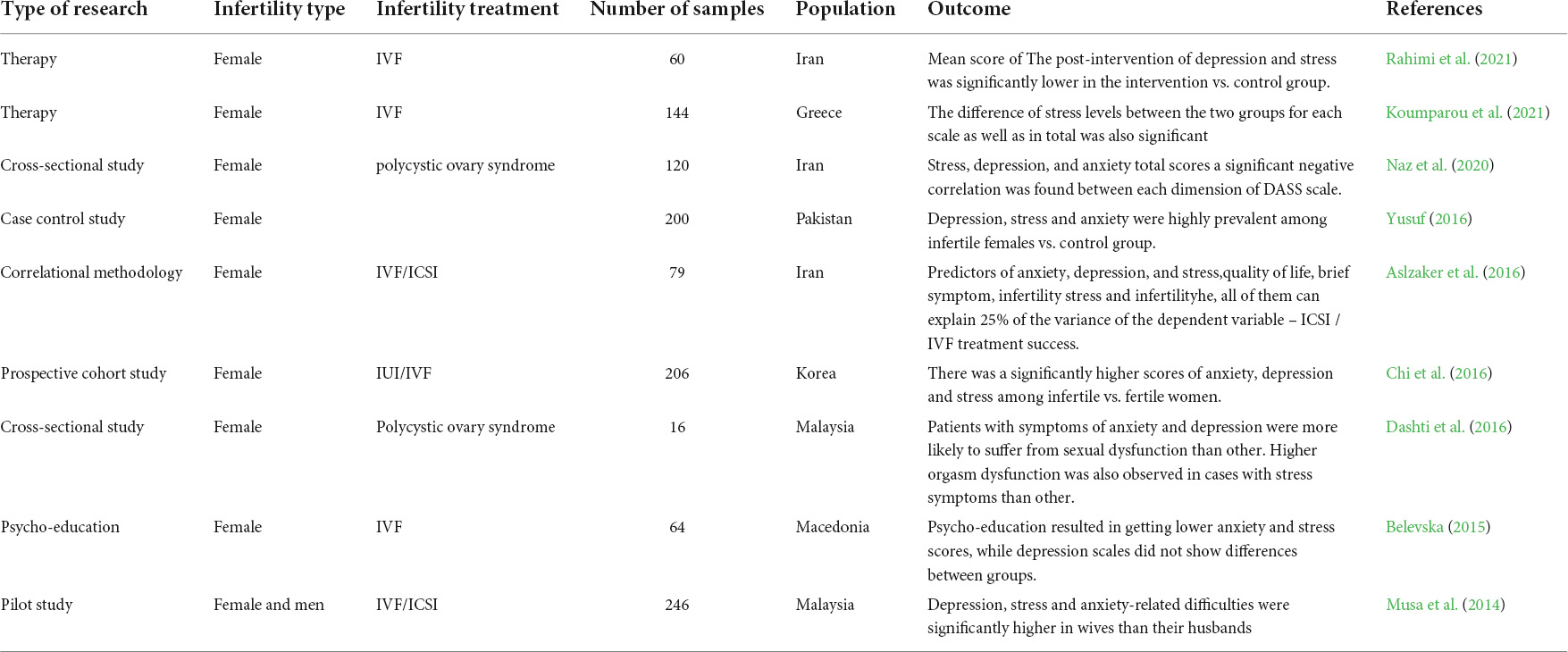

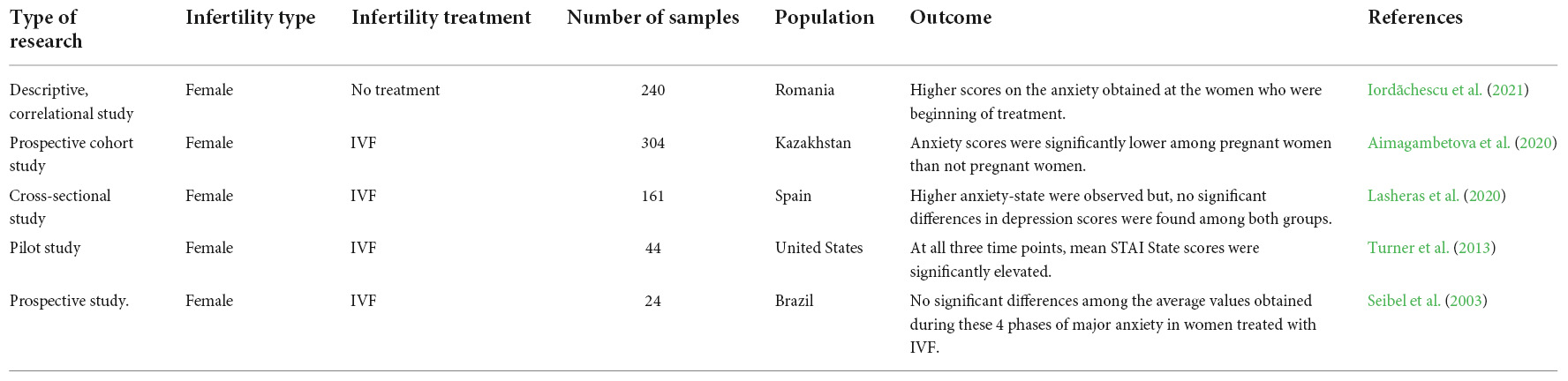

The literature on infertility is disproportionately skewed towards clinical research related to causes of infertility, diagnosis, or Artificial Reproductive Techniques (ART), and lesser on the anthropological, population and public health aspects 21 . Previous studies (nationally and internationally) have looked at cross-sectional data to assess the association between infertility and mental health 17 , 22 , 23 , 24 . However, the study findings of previous studies are either qualitative or limited to a specific facility or have smaller homogenous sample sizes. Furthermore, due to the lengthy duration of infertility diagnosis and treatment, the association of fertility status with mental health outcomes cannot be studied through short-term cross-sectional studies. In a longitudinal analysis, Herbert and colleagues found that depression was a crucial hurdle for women with fertility issues to seek medical advice 25 . Apart from Herbert and colleagues' study, few longitudinal studies have incorporated the impacts of sociodemographic factors such as income, geographical location, marital status, and lifestyle factors such as tobacco and alcohol intake and Body Mass Index (BMI) on fertility status and mental health.

Therefore, this study aims to fill this knowledge gap by presenting a longitudinal analysis of the association of infertility and mental health in Australian women, taking into account sociodemographic and lifestyle factors. From a broader needs perspective, our study is in alignment with one of the five priority areas (maternal, sexual, and reproductive health) of the recently launched National Women's Health Strategy 2020 to 2030 by the Department of Health, Australia 26 , which highlights the growing importance of this issue and the need for this project.

Data source

This study used data over 18 years from survey 2 (22–27 years of age in 2000) to survey 8 (40–45 years of age in 2018) of the 1973–78 birth cohort of the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women's Health (ALSWH) 27 .

Data collection for the study's survey 1 commenced in 1996 when women were aged 18–23 years old. The participants were randomly selected from the national health insurer's database (Medicare Australia) and were broadly representative of women of a similar age in the Australian population 27 . As data on fertility status was only collected from Survey 2 (1996) onwards, Survey 1 has been excluded from this study (details below). Questionnaires, reports and other research outcomes are available on the ALSWH website ( http://www.alswh.org.au ), and more details have been published elsewhere 27 . All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Data sampling

The flow chart in Fig. 1 displays the sampling procedure, along with the inclusion and exclusion criteria. We included data from 6582 of the 14,247 women who had completed at least one survey from Survey 2 to Survey 8. We excluded data from women (1) who had not completed Survey 2, which was considered the baseline for this analysis (n = 4559); (2) those with three or more missing surveys (n = 3018); and (3) those with missing information about fertility status on three or more surveys (n = 88) (discussed further below).

Proportion of 6580 women reporting poor mental health, anxiety, depression and any psychological distress at each survey, according to the fertility status.

Defining 'fertility status' using multiple variables approach

We used the following variables related to 'infertility' and 'child status' to determine the women's 'fertility status' overtime:

Infertility

From Survey 2 onwards, women were asked if they and their partner (current or previous) ever had problems with infertility, defined as having tried unsuccessfully to get pregnant for 12 months or more. Women selected one of the four response options: never tried to get pregnant; no problem with infertility; yes, but have not sought help/treatment; and yes, and have sought help/treatment.

Number and timing of child(ren)

We matched the data from eligible participants with an additional ALSWH data set of "child data" including the number and the presence or absence of children.

Fertility status

We used the above variables to determine the women's fertility status overtime in four mutually exclusive categories:

No infertility issues/voluntarily childfree : no infertility problems reported on any survey and no reported births in the 'child data'/ pregnancies

Primary infertility : infertility problems reported at one or more surveys and no children at all surveys

Secondary infertility : infertility problems reported at one or more surveys with child(ren) born before reported infertility

Resolved infertility : infertility problems at one or more surveys but the child(ren) born after they reported infertility

In further analysis, the category of 'No infertility/ voluntarily child free' was chosen as the reference category.

Measurement of mental health

Presence and levels of reported anxiety and depressive symptoms were assessed by the three validated measures described below:

Current mental health

The SF-36 Mental Health Index (SF-36 MHI) is a five-item subscale of the SF-36 quality of life measure 28 which was collected at all survey rounds. The five items were used to generate a score of 0 to 100 with higher scores indicating better mental health 29 . We applied the commonly used cut-point of ≤ 52 to categorise women as reporting psychological distress at each survey 30 , 31 . Previous research has established this cut point to be conservatively within the bounds of a clinically meaningful indicator of psychological distress 29 .

Current depressive symptoms

The 10-item version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CESD-10) scores (ranging from 0 to 30) were used to measure current depressive symptoms at each survey 28 . A cut-point of ≥ 10 was indicative of a potential clinical diagnosis of depression 32 .

Current anxiety symptoms

The Goldberg Anxiety and Depression Scale (GADanx) anxiety subscale was included in questionnaires from Survey 3 onwards and was used to measure current symptoms indicative of an anxiety disorder. A score greater than five indicates a potential anxiety disorder 33 .

Additionally, we created a composite variable for 'any psychological distress'. Women were identified as having 'any psychological distress' if in any survey, they (1) self-reported anxiety or depression in the last 3 years or (2) their scores on any of the above three validated measures were above or below the respective cut-points described above.

Explanatory variables

We included sociodemographic, chronic health and behavioural factors in the analysis to check and adjust for potential confounding in the association between infertility and mental health.

Demographic factors: the highest level of qualification (no education, school certificate, trade/certificate/diploma and higher education), marital status (partnered, not partnered), area of residence as per the Accessibility/remoteness Index of Australia (ARIA) Plus classification system 34 ; paid work status (not in paid work/in paid work); self-reported general health (excellent/good, fair/poor);

Chronic health issues including diabetes, heart disease, high blood pressure, asthma, cancer and other major physical illness and smoking status (non-smoker, ex-smoker, current smoker); and

Health behavior factors: alcohol consumption (non-drinker, low-risk drinker, high-risk drinker) and BMI (< 18.5, 18.5–24.9, 25–29.9, ≥ 30)

Missing at random data were filled using the 'last observation carried forward (LOCF)' approach to maintain the sample size and reduce the bias caused by the attrition of participants in the study.

Statistical analysis

We used descriptive statistics to analyse baseline demographics and describe psychological distress. We used longitudinal, repeated measures models utilising the generalised estimating equations (GEE) method in parameter estimation for both univariate and multivariate data modelling to test for the presence of an association between ‘Fertility Status and Psychological distress’ (composite variable). GEE analysis requires some key assumptions to be maintained, such as dependent variable linearly related to the predicters, high number of clusters, and observations independent of each other 35 . ALSWH data fulfilled these assumptions, and, therefore, GEE was considered the analysis of choice. Furthermore, GEE enables us to conduct longitudinal data analysis with dichotomous, categorical, nominal or ordinal variables 35 and, therefore, was effective for examining the ALSWH data. Each GEE model (described below) was adjusted for time (six survey rounds) and 'fertility status' with 'psychological distress' as the dependent variable. Variables with a p value of less than 0.25 in the initial univariate approach were selected and entered into the multivariate models as described below 36 .

Model 1: Adjusted for time and fertility status

Model 2: Adjusted for time and fertility status + demographic factors

Model 3: Adjusted for time and fertility status + demographic factors + common chronic health conditions

Model 4: Fully adjusted for time and fertility status + demographic factors + common chronic health conditions + health behaviour factors.

For health conditions (Model 3 and Model 4), the status of 'No' was the reference category. The exchangeable correlation structure approach was utilised for the multivariate modelling based on a smaller QIC (Quasilikelihood under the Independence model Criterion) statistic. The results were reported using odds ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals. SAS 9.4 was used for all analyses.

Ethics approval

This project was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committees (HREC) of the University of Newcastle and the University of Queensland (The University of Newcastle HREC EC00144 , ratified by The University of Queensland HREC EC00456/7 ). The ALSWH survey program has ongoing ethical approval from the Human Research Ethics Committees (HRECs) of the Universities of Newcastle and Queensland (approval numbers H-076-0795 and 2004000224, respectively, for the 1973–78 cohort). Informed consent was obtained from all participants. All participants consented to joining the study and were free to withdraw or suspend their participation at any time with no need to provide a reason.

A total of 6582 women were eligible to be included in the analysis. There was a steady increase in the proportion of women reporting problems with infertility over time. The proportion of women reporting having infertility problems and seeking treatment increased from 1.7% at survey 2 to 19.3% at survey 8, which shows a massive increase in reported infertility (see Table 1 ).

Using the definition for ‘fertility status over time’, the four mutually exclusive categories were created (from the original variable). As seen in Table 2 , 69.2% of women had no reported infertility problem or were voluntarily childfree. Among the women with some reported infertility problems, the majority (18.11%) had resolved infertility.

Table 3 compares each fertility status category's demographic, health, and health behaviour factors at baseline survey 2. The majority of the women in all the categories of fertility status had higher education, were not partnered, were working in paid jobs and living in urban areas. Women reported their general health to be excellent or good. Chronic health conditions such as diabetes, heart disease, high blood pressure, asthma and other physical illnesses were reported higher in women with primary infertility as compared to women reporting secondary infertility, resolved infertility or no infertility. Most women were non-smokers, engaged in low-risk alcohol use, and had an acceptable BMI (Table 3 ).

Figure 1 presents the proportions of the reported psychological distress variables—SF-36 MHI, CESD10 and Goldberg anxiety and depression scales, along with the psychological distress variable over time. The proportion of women with no infertility reporting poor mental health on the SF-36 MHI decreased and stabilised over time; however, the proportion of women reporting poor mental health with primary infertility gradually increased. Fluctuation in reporting poor mental health was seen among women with secondary and resolved infertility; however, a considerable proportion reported poor mental health by survey 8 (women aged 42–45 years). Considerable fluctuation in the proportion of women reporting current depressive symptoms (CESD10) was seen over time. Compared to Survey 2 and Survey 3, few women reported current anxiety symptoms over time. Nearly 50% of women with primary and secondary infertility met the criteria for any psychological distress using the composite psychological distress variable. Women without infertility issues and resolved infertility also had a high proportion of women (40% and 45% respectively) reporting any psychological distress.

The results of the study showed that the odds of reporting psychological distress significantly increased in all models with time (see Table 4 ). The effect of fertility status on the psychological distress was significant for women with primary and secondary infertility ( p < 0.001) and for women with resolved infertility ( p < 0.001), as compared to women without infertility problems or voluntarily child free. In the fully adjusted GEE model, many covariates made significant independent contributions to psychological distress. For example, women who were partnered, reported having diabetes, high blood pressure, asthma, major physical illness, were currently smoking or were ex-smoker, were high-risk drinkers, and reported either with BMI < 18.5 ≥ 30 had higher odds of reported psychological distress over time ( p < 0.05), compared to women in reference categories. Women who were in paid work were less likely to report psychological distress over time ( p < 0.05). Few variables such as area of residence, heart disease, cancer was not statistically significant in the adjusted models (Table 4 ).

This research project assessed the longitudinal associations between fertility status and psychological distress over time among Australian women. To the best of our knowledge, this study is one of the first in Australia to explore these longitudinal associations over 18 years of data. The findings of the longitudinal analysis show that fertility status is an enduring condition that has a significant association with mental health outcomes among our sample of Australian women of reproductive age followed for 18 years from their 20 s to their early 40 s. The study also indicated that mental health impact remains highly substantial among the women who reported primary or secondary infertility and those who reported ‘resolved infertility’. This finding reveals the long-term impact of fertility issues and problems on women.

These findings are corroborated by previous research, which showed that infertility impacts women’s overall self-esteem, confidence, and performance 37 . A previous longitudinal study by Herbert et al. on Australian women’s health data found that out of 5936 women, 1031 women with infertility reported higher odds of self-reported depression than 4905 women who were not suffering from infertility 25 . Herbert et al. also indicated that women with depression and depressive symptoms were less likely to utilise healthcare to treat infertility, which may not resolve infertility 25 . Similarly, other researchers have demonstrated unresolved infertility's adverse long-term mental health impact through several longitudinal studies in Italy, Canada, Denmark, Australia, and Germany 7 , 16 , 38 , 39 .

The desire to have a child is common for many couples and individuals and is emphasised by continued cultural and societal norms 9 , 40 . In several pronatalist cultures, childlessness is associated with the stigma of disgrace, shame, and societal shunning, in addition to marital discord 41 , 42 . In many countries, cultural and societal pressure demands women to have at least one biological child or face discrimination, stigmatisation, and ostracism 42 , 43 . Infertility/subfertility is also associated with higher intimate partner violence 44 . Couples, therefore, choose to remain silent and avoid the anxiety associated with the stigma of infertility and its treatment 45 . Galhardo et al. recorded higher levels of depression and a sense of shame in couples diagnosed with infertility compared to those with no known diagnosis of infertility and adoption-ready couples with a diagnosis of infertility 46 . The researchers also found that couples with the diagnosis of infertility resorted to negative coping mechanisms (avoidant) in comparison to the rational styles (acceptance) of coping reported by adoption-ready couples 46 .

The impact of infertility on mental health may be due to various intersecting reasons. These include the slow and unpredictable success rates of infertility treatment (Chambers, Sullivan, & Ho, 2006), leading to added stress and anxiety, particularly in socioeconomically disadvantaged groups 47 . In many countries, assisted reproductive technology (ART) is expensive, and ART services are either partially included or not included under the government primary healthcare package, nor is it entirely covered by private health insurance 1 . Therefore, the financial barrier to access ART services adds to the infertility treatment-related stress 1 .

In this study, partnered women reported more psychological distress than non-partnered women. This difference may be linked to the socio-cultural aspects of infertility, where in some cultures, childbearing is considered an essential component of married life and is viewed as a symbol of social status 21 , 22 . Alternatively, it may be explained by understanding how couples cope with infertility compared to non-partnered individuals. Two longitudinal studies have highlighted that couples with infertility that use active and passive coping strategies (such as avoidance) have higher psychological distress compared to couples engaged in meaning-based coping strategies (problem-focused strategies, motivation, and optimism) 45 , 48 .

In this study, women in paid employment reported significantly lower psychological distress (Chambers et al., 2013). This finding is not surprising since paid employment gives financial stability and helps couples with higher socioeconomic status have more resources to seek and utilise infertility treatment 47 .

We found that having an underweight BMI or being obese was significantly associated with psychological distress. Scott et al. (2008) analysed 62,277 people in the world mental health surveys and reported that high BMI was modestly associated with mental health disorders in women 49 . Previous studies have highlighted that obesity or being underweight, both extremes can adversely affect fertility 50 , 51 , 52 . Esmaeilzadeh et al. (2013) have also found that women with infertility experience had a 4.8-fold increased risk of obesity compared to women without infertility 53 . Therefore, both high or extremely low BMI should be considered risk factors during mental health and infertility treatment.

Further, the analysis of behavioural health factors such as the prevalence of smoking and alcohol were significantly higher in women reporting psychological distress. Apart from anxiety, there was a significant prevalence of certain chronic illnesses such as diabetes, high blood pressure, asthma, and other major physical illnesses in women reporting psychological distress. Herbert et al. have also reported similar findings (2010). Although our study did not find a significant association between fertility status and psychological distress in women with cancers, previous studies have highlighted that fertility-related psychological distress is prevalent in cancer patients and survivors 54 . In another extensive epidemiological review that analysed 82 articles, Direkvand-M et al. iterated that modifying lifestyle factors such as smoking, alcohol and physical activity, and early diagnosis and management of chronic diseases can significantly help to improve the fertility status in women 55 . Lifestyle risk factors such as smoking, alcohol, unhealthy dietary habits and physical inactivity are responsible for several chronic diseases. The significant findings regarding the lifestyle factors call for a holistic approach during infertility treatment, including awareness and promoting behavioural changes in diet, physical activity, smoking, and alcohol use.

Our study had a few expected limitations. Firstly, the gender differences could not be analysed. Although men with infertility also suffer from poor mental health outcomes 16 , 56 , nationally representative men-only longitudinal data on infertility is unavailable in Australia. Future researchers would focus on assessing gender differences longitudinally. Secondly, we assumed that data was ‘missing at random’, and these missing values were filled in using the last observation carried forward approach that may have caused analytic bias; however, we tried to minimise this possibility by only imputing missing at random observations and by excluding women with three or more missing surveys. Despite a rigorous participant recruitment strategy, the ALSWH study has lower representation from minority groups, Indigenous population, refugees, and non-English speaking migrants. This low representation from diverse community groups is an issue that needs to be addressed at multiple levels starting from the national policy and is, therefore, beyond the scope of the study. We were also unable to include infertility treatments in our assessments as these are not covered by the Medicare (healthcare access scheme for Australians and some visa holders) and hence not a part of the survey and/or linked administrative data. The other limitation of the study was that we could not include clinical conditions related to infertility, such as, polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) or endometriosis. Apart from affecting fertility, PCOS is significantly associated with severe mental health distress, body dissatisfaction and eating disorders 57 , 58 . Further studies should be conducted to understand the relationship of clinical conditions that affect fertility status such as PCOS on mental health distress.

However, the study has several conceptual, methodological, and analytical strengths that have helped us understand the importance of using an integrated approach to treat patients with infertility. We conducted an extensive literature review to understand the gaps in the literature and identify the strengths of different longitudinal studies. ALSWH is the largest and longest-running survey and provides an in-depth insight into various aspects of women’s health in Australia. The longitudinal approach gives an opportunity to follow up the trends of fertility status and mental health in women’s health for 18 years. We independently assessed three validated measures of psychological distress and created a composite score to define psychological distress at each survey; defined fertility status in four mutually exclusive categories by using survey and child and birth data to capture all the relevant details. With these rich data over seven surveys and covering almost 18 years, Generalised Estimating Equation was a robust technique to assess the longitudinal associations.

This study highlighted that infertility is a multidimensional stressor causing anxiety, stress, and depression with long-lasting mental health consequences and makes a strong case for infertility as a strategic public health priority. The study has important implications for implementing the current Australian National women’s health strategy 2020–2030. The implication includes improving the assessment of infertility issues as well as equitable access and affordability of infertility treatment for all groups of population. The assessment of infertility should consist of a comprehensive approach beyond clinically focused management and plans for risky lifestyle behaviours such as smoking and alcohol use. Regular mental health screening should be conducted for all patients, especially in women with primary, secondary, or resolved infertility with easy and accessible access to mental health support to protect women from long-term mental health impacts.

Infertility is rapidly emerging as a significant global health issue. Human overpopulation is causing over consumption of natural resources and causing climate change. The global warming crisis and environmental pollutants are increasing the burden of diseases and a rise in fertility issues. Environmental health affects human health and therefore, we should also draw attention to on the broader issues such as climate change and overpopulation.

Data availability

The Australian Government Department of Health owns ALSWH survey data and due to the personal nature of the data collected, release by ALSWH is subject to strict contractual and ethical restrictions. Ethical review of ALSWH is by the Human Research Ethics Committees at The University of Queensland and The University of Newcastle. De-identified data are available to collaborating researchers where a formal request to use the material has been approved by the ALSWH Data Access Committee. The committee is receptive of requests for datasets required to replicate results. Information on applying for ALSWH data is available from https://alswh.org.au/for-data-users/applying-for-data .

Starrs, A. M. et al. Accelerate progress-sexual and reproductive health and rights for all: Report of the Guttmacher-Lancet Commission. Lancet 391 , 2642–2692. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)30293-9 (2018).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

WHO. WHO fact sheet on infertility. Glob. Reprod. Health 6 , e52. https://doi.org/10.1097/grh.0000000000000052 (2021).

Article Google Scholar

Sun, H. et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence and disability-adjusted life-years for infertility in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: Results from a global burden of disease study, 2017. Aging (Albany NY) 11 , 10952–10991. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.102497 (2019).

Evers, J. L. H. Female subfertility. Lancet 360 , 151–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09417-5 (2002).

Herbert, D. L., Lucke, J. C. & Dobson, A. J. Infertility, medical advice and treatment with fertility hormones and/or in vitro fertilisation: A population perspective from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 33 , 358–364. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-6405.2009.00408.x (2009).

Gilbert, E. W., Boyle, J. A., Campbell, S. K. & Rumbold, A. R. Infertility in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: A cause for concern?. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 60 , 479–481. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajo.13158 (2020).

Schanz, S. et al. Long-term life and partnership satisfaction in infertile patients: A 5-year longitudinal study. Fertil. Steril. 96 , 416–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.05.064 (2011).

Greil, A. L., Slauson-Blevins, K. & McQuillan, J. The experience of infertility: A review of recent literature. Sociol. Health Illn. 32 , 140–162. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2009.01213.x (2010).

Gonzalez, L. O. Infertility as a transformational process: A framework for psychotherapeutic support of infertile women. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 21 , 619–633. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840050110317 (2000).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Chachamovich, J. R. et al. Investigating quality of life and health-related quality of life in infertility: A systematic review. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 31 , 101–110. https://doi.org/10.3109/0167482X.2010.481337 (2010).

Jacob, M. C., McQuillan, J. & Greil, A. L. Psychological distress by type of fertility barrier. Hum. Reprod. 22 , 885–894. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/del452 (2007).

Klemetti, R., Raitanen, J., Sihvo, S., Saarni, S. & Koponen, P. Infertility, mental disorders and well-being—A nationwide survey. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 89 , 677–682. https://doi.org/10.3109/00016341003623746 (2010).

Biringer, E., Howard, L. M., Kessler, U., Stewart, R. & Mykletun, A. Is infertility really associated with higher levels of mental distress in the female population? Results from the North-Trøndelag Health Study and the Medical Birth Registry of Norway. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 36 , 38–45 (2015).

McQuillan, J., Greil, A. L., White, L. & Jacob, M. C. Frustrated fertility: Infertility and psychological distress among women. J. Marriage Fam. 65 , 1007–1018 (2003).

Berg, B. J. & Wilson, J. F. Psychiatric morbidity in the infertile population: A reconceptualization. Fertil. Steril. 53 , 654–661 (1990).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Fisher, J. R. W., Baker, G. H. W. & Hammarberg, K. Long-term health, well-being, life satisfaction, and attitudes toward parenthood in men diagnosed as infertile: Challenges to gender stereotypes and implications for practice. Fertil. Steril. 94 , 574–580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.01.165 (2010).

Oddens, B. J., den Tonkelaar, I. & Nieuwenhuyse, H. Psychosocial experiences in women facing fertility problems—A comparative survey. Hum. Reprod. 14 , 255–261. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/14.1.255 (1999).

Graham, M. L., Hill, E., Shelley, J. M. & Taket, A. R. An examination of the health and wellbeing of childless women: A cross-sectional exploratory study in Victoria, Australia. BMC Womens Health 11 , 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6874-11-47 (2011).

Maximova, K. & Quesnel-Vallée, A. Mental health consequences of unintended childlessness and unplanned births: Gender differences and life course dynamics. Soc. Sci. Med. 68 , 850–857. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.11.012 (2009).

Holton, S., Fisher, J. & Rowe, H. Motherhood: Is it good for women’s mental health?. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 28 , 223–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646830903487359 (2010).

Widge, A. Sociocultural attitudes towards infertility and assisted reproduction in India. Curr. Pract. Controv. Assist. Reprod. 60 , 74 (2002).

Google Scholar

Khan, A. R., Iqbal, N. & Afzal, A. Impact of Infertility on mental health of women. Int. J. Indian Psychol. 7 (1), 804–809. https://doi.org/10.25215/0701.089 (2019).

Ramezanzadeh, F. et al. A survey of relationship between anxiety, depression and duration of infertility. BMC Womens Health 4 , 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6874-4-9 (2004).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hasanpoor-Azghdy, S. B., Simbar, M. & Vedadhir, A. The emotional-psychological consequences of infertility among infertile women seeking treatment: Results of a qualitative study. Iran. J. Reprod. Med. 12 , 131 (2014).

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Herbert, D. L., Lucke, J. C. & Dobson, A. J. Depression: An emotional obstacle to seeking medical advice for infertility. Fertil. Steril. 94 , 1817–1821. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.10.062 (2010).

Mishra, G. D., Chung, H.-F. & Dobson, A. J. The current state of women’s health in Australia: Informing the development of the National Women’s Health Strategy 2020–2030. (Canberra, Australia, 2018).

Lee, C. et al. Cohort profile: The Australian Longitudinal Study on women’s health. Int. J. Epidemiol. 34 , 987–991. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyi098 (2005).

Holden, L. et al. Mental Health: Findings from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health (Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, 2013).

Rumpf, H.-J., Meyer, C., Hapke, U. & John, U. Screening for mental health: Validity of the MHI-5 using DSM-IV Axis I psychiatric disorders as gold standard. Psychiatry Res. 105 , 243–253 (2001).

Holmes, W. C. A short, psychiatric, case-finding measure for HIV seropositive outpatients: Performance characteristics of the 5-item mental health subscale of the SF-20 in a male, seropositive sample. Med. Care 36 , 237–243. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199802000-00012 (1998).

Silveira, E. et al. Performance of the SF-36 health survey in screening for depressive and anxiety disorders in an elderly female Swedish population. Qual. Life Res. 14 , 1263–1274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-004-7753-5 (2005).

Andresen, E. M., Malmgren, J. A., Carter, W. B. & Patrick, D. L. Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D. Am. J. Prev. Med. 10 , 77–84 (1994).

Goldberg, D., Bridges, K., Duncan-Jones, P. & Grayson, D. Detecting anxiety and depression in general medical settings. BMJ 297 , 897–899. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.297.6653.897 (1988).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Remoteness, M. Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia (ARIA) (Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care 2, I, 2001).

Ghisletta, P. & Spini, D. An introduction to generalized estimating equations and an application to assess selectivity effects in a longitudinal study on very old individuals. J. Educ. Behav. Stat. 29 , 421–437. https://doi.org/10.3102/10769986029004421 (2004).

Costanza, M. C. & Afifi, A. Comparison of stopping rules in forward stepwise discriminant analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 74 , 777–785 (1979).

Ezzell, W. The impact of infertility on women’s mental health. N. C. Med. J. 77 , 427. https://doi.org/10.18043/ncm.77.6.427 (2016).

Agostini, F. et al. Assisted reproductive technology treatments and quality of life: A longitudinal study among subfertile women and men. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 34 , 1307–1315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-017-1000-9 (2017).

Daniluk, J. C. Reconstructing their lives: A longitudinal, qualitative analysis of the transition to biological childlessness for infertile couples. J. Couns. Dev. 79 , 439–449. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2001.tb01991.x (2001).

Riggs, D. W. & Bartholomaeus, C. The desire for a child among a sample of heterosexual Australian couples. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 34 , 442–450. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2016.1222070 (2016).

Wilkes, S. & Fankam, F. Review of the management of female infertility: A primary care perspective. Clin. Med. Rev. Women’s Health 2010 , 11–23 (2010).

Tabong, P.T.-N. & Adongo, P. B. Infertility and childlessness: a qualitative study of the experiences of infertile couples in Northern Ghana. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 13 , 72. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-13-72 (2013).

Sembuya, R. Mother or nothing: the agony of infertility. Bull. World Health Organ. 88 , 881–882 (2010).

Stellar, C., Garcia-Moreno, C., Temmerman, M. & van der Poel, S. A systematic review and narrative report of the relationship between infertility, subfertility, and intimate partner violence. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 133 , 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.08.012 (2016).

Schmidt, L., Christensen, U. & Holstein, B. The social epidemiology of coping with infertility. Hum. Reprod. 20 , 1044–1052. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deh687 (2005).

Galhardo, A., Cunha, M. & Pinto-Gouveia, J. Psychological aspects in couples with infertility. Sexologies 20 , 224–228 (2011).

Chambers, G. M., Hoang, V. & Illingworth, P. J. Socioeconomic disparities in access to ART treatment and the differential impact of a policy that increased consumer costs. Hum. Reprod. 28 , 3111–3117. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/det302 (2013).

Peterson, B. D. et al. The longitudinal impact of partner coping in couples following 5 years of unsuccessful fertility treatments. Hum. Reprod. 24 , 1656–1664. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dep061 (2009).

Scott, K. M. et al. Obesity and mental disorders in the general population: Results from the world mental health surveys. Int. J. Obes. (Lond.) 32 , 192–200. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0803701 (2008).

Boutari, C. et al. The effect of underweight on female and male reproduction. Metabolism 107 , 154229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154229 (2020).

Talmor, A. & Dunphy, B. Female obesity and infertility. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 29 , 498–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2014.10.014 (2015).

Sharma, R., Biedenharn, K. R., Fedor, J. M. & Agarwal, A. Lifestyle factors and reproductive health: Taking control of your fertility. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 11 , 66. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7827-11-66 (2013).

Esmaeilzadeh, S., Delavar, M. A., Basirat, Z. & Shafi, H. Physical activity and body mass index among women who have experienced infertility. Arch. Med. Sci. 9 , 499–505. https://doi.org/10.5114/aoms.2013.35342 (2013).

Logan, S., Perz, J., Ussher, J. M., Peate, M. & Anazodo, A. Systematic review of fertility-related psychological distress in cancer patients: Informing on an improved model of care. Psychooncology 28 , 22–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4927 (2019).

Direkvand-Moghadam, A., Delpisheh, A. & Khosravi, A. Epidemiology of female infertility; A review of literature. Biosci. Biotechnol. Res. Asia 10 , 559–567. https://doi.org/10.13005/bbra/1165 (2013).

Ying, L. Y., Wu, L. H. & Loke, A. Y. Gender differences in experiences with and adjustments to infertility: A literature review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 52 , 1640–1652. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.05.004 (2015).

Himelein, M. J. & Thatcher, S. S. Polycystic ovary syndrome and mental health: A review. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 61 , 723–732. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ogx.0000243772.33357.84 (2006).

Brutocao, C. et al. Psychiatric disorders in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Endocrine 62 , 318–325. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-018-1692-3 (2018).

Download references

Acknowledgements

A research team conducts the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health at the University of Newcastle and the University of Queensland. We are grateful to the women who participated in the study and the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing for funding this extraordinary initiative. We acknowledge Hunter Medical Research Institute, Australia, for funding the statistical support of this research project.

The study received a grant from Hunter Medical Research Institute, Australia, for statistical support (Grant Number: G2100167).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

College of Health, Medicine and Wellbeing, The University of Newcastle (UON), University Drive, Callaghan, NSW, 2308, Australia

Tanmay Bagade, Kailash Thapaliya, Erica Breuer, Zhuoyang Li, Elizabeth Sullivan & Tazeen Majeed

Samatva Wellness Center, Noida, India

Rashmi Kamath

Registry of Senior Australians (ROSA), South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute (SAHMRI), North Terrace, Adelaide, SA, 5000, Australia

Kailash Thapaliya

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

T.B., T.M., and E.B. designed the key concept and the project with expert input from E.S. and Z.L. T.B and R.K. wrote the introduction, T.M. and Z.L. oversaw the statistical plan and K.T. was involved in data cleaning and some descriptive analysis, while T.M. conducted the complete analysis, T.M. and K.T. wrote the methods and T.M. write the results section of the manuscript with inputs from E.B. and Z.L. T.B. wrote the discussion, with inputs from T.M., E.B., ES and Z.L. on content and structure. All the authors – T.B., K.T., E.B., R.K., Z.L., E.S. and T.M. reviewed the manuscript multiple times and provided input to the subsequent drafts. The corresponding author (T.B.) and the authors had full access to information used in this study and had the final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Tanmay Bagade .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Bagade, T., Thapaliya, K., Breuer, E. et al. Investigating the association between infertility and psychological distress using Australian Longitudinal Study on Women's Health (ALSWH). Sci Rep 12 , 10808 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-15064-2

Download citation

Received : 02 March 2022

Accepted : 17 June 2022

Published : 25 June 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-15064-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

The social determinants of mental health disorders among women with infertility: a systematic review.

- Tanmay Bagade

- Amanual Getnet Mersha

- Tazeen Majeed

BMC Women's Health (2023)

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- ESHRE Pages

- Mini-reviews

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Reasons to Publish

- Open Access

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Advertising

- Reprints and ePrints

- Sponsored Supplements

- Branded Books

- Journals Career Network

- About Human Reproduction

- About the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology

- Editorial Board

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Contact ESHRE

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, materials and methods, supplementary data, acknowledgments.

- < Previous

Top 10 priorities for future infertility research: an international consensus development study † ‡

Members of the Priority Setting Partnership for Infertility are listed in the Appendix.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

J M N Duffy, G D Adamson, E Benson, S Bhattacharya, S Bhattacharya, M Bofill, K Brian, B Collura, C Curtis, J L H Evers, R G Farquharson, A Fincham, S Franik, L C Giudice, E Glanville, M Hickey, A W Horne, M L Hull, N P Johnson, V Jordan, Y Khalaf, J M L Knijnenburg, R S Legro, S Lensen, J MacKenzie, D Mavrelos, B W Mol, D E Morbeck, H Nagels, E H Y Ng, C Niederberger, A S Otter, L Puscasiu, S Rautakallio-Hokkanen, L Sadler, I Sarris, M Showell, J Stewart, A Strandell, C Strawbridge, A Vail, M van Wely, M Vercoe, N L Vuong, A Y Wang, R Wang, J Wilkinson, K Wong, T Y Wong, C M Farquhar, Priority Setting Partnership for Infertility , Top 10 priorities for future infertility research: an international consensus development study , Human Reproduction , Volume 35, Issue 12, December 2020, Pages 2715–2724, https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deaa242

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Can the priorities for future research in infertility be identified?

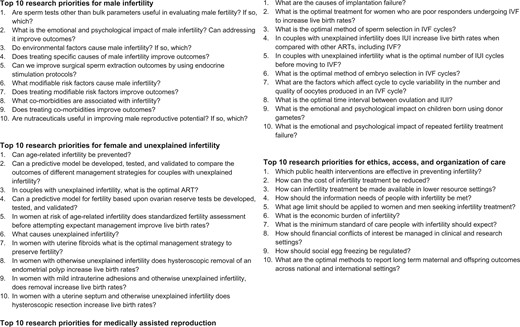

The top 10 research priorities for the four areas of male infertility, female and unexplained infertility, medically assisted reproduction and ethics, access and organization of care for people with fertility problems were identified.

Many fundamental questions regarding the prevention, management and consequences of infertility remain unanswered. This is a barrier to improving the care received by those people with fertility problems.

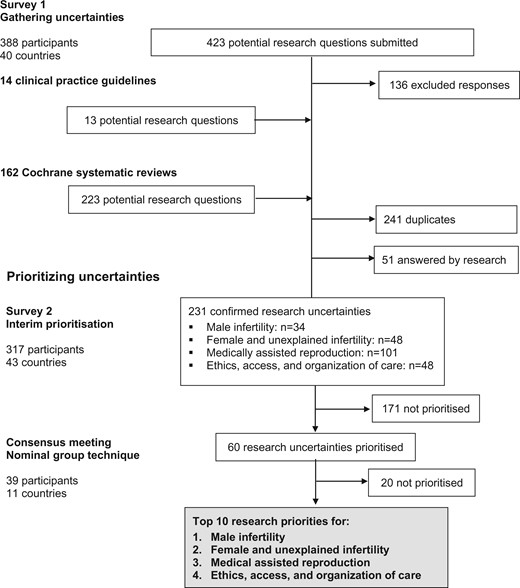

Potential research questions were collated from an initial international survey, a systematic review of clinical practice guidelines and Cochrane systematic reviews. A rationalized list of confirmed research uncertainties was prioritized in an interim international survey. Prioritized research uncertainties were discussed during a consensus development meeting. Using a formal consensus development method, the modified nominal group technique, diverse stakeholders identified the top 10 research priorities for each of the categories male infertility, female and unexplained infertility, medically assisted reproduction and ethics, access and organization of care.

Healthcare professionals, people with fertility problems and others (healthcare funders, healthcare providers, healthcare regulators, research funding bodies and researchers) were brought together in an open and transparent process using formal consensus methods advocated by the James Lind Alliance.

The initial survey was completed by 388 participants from 40 countries, and 423 potential research questions were submitted. Fourteen clinical practice guidelines and 162 Cochrane systematic reviews identified a further 236 potential research questions. A rationalized list of 231 confirmed research uncertainties was entered into an interim prioritization survey completed by 317 respondents from 43 countries. The top 10 research priorities for each of the four categories male infertility, female and unexplained infertility (including age-related infertility, ovarian cysts, uterine cavity abnormalities and tubal factor infertility), medically assisted reproduction (including ovarian stimulation, IUI and IVF) and ethics, access and organization of care were identified during a consensus development meeting involving 41 participants from 11 countries. These research priorities were diverse and seek answers to questions regarding prevention, treatment and the longer-term impact of infertility. They highlight the importance of pursuing research which has often been overlooked, including addressing the emotional and psychological impact of infertility, improving access to fertility treatment, particularly in lower resource settings and securing appropriate regulation. Addressing these priorities will require diverse research methodologies, including laboratory-based science, qualitative and quantitative research and population science.

We used consensus development methods, which have inherent limitations, including the representativeness of the participant sample, methodological decisions informed by professional judgment and arbitrary consensus definitions.

We anticipate that identified research priorities, developed to specifically highlight the most pressing clinical needs as perceived by healthcare professionals, people with fertility problems and others, will help research funding organizations and researchers to develop their future research agenda.

The study was funded by the Auckland Medical Research Foundation, Catalyst Fund, Royal Society of New Zealand and Maurice and Phyllis Paykel Trust. G.D.A. reports research sponsorship from Abbott, personal fees from Abbott and LabCorp, a financial interest in Advanced Reproductive Care, committee membership of the FIGO Committee on Reproductive Medicine, International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technologies, International Federation of Fertility Societies and World Endometriosis Research Foundation, and research sponsorship of the International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technologies from Abbott and Ferring. Siladitya Bhattacharya reports being the Editor-in-Chief of Human Reproduction Open and editor for the Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility Group. J.L.H.E. reports being the Editor Emeritus of Human Reproduction . A.W.H. reports research sponsorship from the Chief Scientist’s Office, Ferring, Medical Research Council, National Institute for Health Research and Wellbeing of Women and consultancy fees from AbbVie, Ferring, Nordic Pharma and Roche Diagnostics. M.L.H. reports grants from Merck, grants from Myovant, grants from Bayer, outside the submitted work and ownership in Embrace Fertility, a private fertility company. N.P.J. reports research sponsorship from AbbVie and Myovant Sciences and consultancy fees from Guerbet, Myovant Sciences, Roche Diagnostics and Vifor Pharma. J.M.L.K. reports research sponsorship from Ferring and Theramex. R.S.L. reports consultancy fees from AbbVie, Bayer, Ferring, Fractyl, Insud Pharma and Kindex and research sponsorship from Guerbet and Hass Avocado Board. B.W.M. reports consultancy fees from Guerbet, iGenomix, Merck, Merck KGaA and ObsEva. E.H.Y.N. reports research sponsorship from Merck. C.N. reports being the Co Editor-in-Chief of Fertility and Sterility and Section Editor of the Journal of Urology , research sponsorship from Ferring and retains a financial interest in NexHand. J.S. reports being employed by a National Health Service fertility clinic, consultancy fees from Merck for educational events, sponsorship to attend a fertility conference from Ferring and being a clinical subeditor of Human Fertility . A.S. reports consultancy fees from Guerbet. J.W. reports being a statistical editor for the Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility Group. A.V. reports that he is a Statistical Editor of the Cochrane Gynaecology & Fertility Review Group and the journal Reproduction . His employing institution has received payment from Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority for his advice on review of research evidence to inform their ‘traffic light’ system for infertility treatment ‘add-ons’. N.L.V. reports consultancy and conference fees from Ferring, Merck and Merck Sharp and Dohme. The remaining authors declare no competing interests in relation to the present work. All authors have completed the disclosure form.

The ultimate aim of infertility research is to improve clinical practice and optimize the chances of people with fertility problems achieving parenthood. For this to be possible, research needs to address questions that are pertinent to people with infertility, be conducted using appropriate methods, and be reported in a comprehensive, transparent and accessible manner ( Duffy et al. , 2017 ). The first step in research production is to identify appropriate questions. Traditionally, research funding organizations and researchers have identified, refined and prioritized their own research agenda. It is unlikely that such prioritization has used formal consensus methods, engaged wider stakeholders, including people with fertility problems, and was independent of commercial interests. There has been modest improvement in some countries, including the Netherlands, the UK and the USA, which has emphasized the importance of including patients and the public in developing research priorities ( Graham et al. , 2020 ).

Sir Iain Chalmers, founder of the Cochrane Collaboration, has advocated for research priorities to be jointly identified by healthcare professionals, patients and communities ( Chalmers and Glasziou, 2009 ). He established the James Lind Alliance, which brings together healthcare professionals, patients and others, in priority setting partnerships. Using formal consensus methods, each priority setting partnership engages in an open and transparent process to identify and prioritize unanswered research questions, known as research uncertainties, in a particular area of health care ( James Lind Alliance, 2018 ). The expectation is that prioritized research uncertainties will establish the future research agenda of funding organizations and researchers. As a result, it is hoped that the gap will close between what research is needed and what research is pursued ( Wilkinson et al. , 2019a ).

An international collaboration has brought healthcare professionals, people with fertility problems and others together within a Priority Setting Partnership for Infertility to develop future research priorities for male infertility, female and unexplained infertility, medically assisted reproduction and ethics, access and organization of care.

An international multidisciplinary steering group, including healthcare professionals, people with fertility problems and researchers, was established to provide a diverse range of perspectives to inform key methodological decisions. The steering group was convened during the development of the study protocol, before the launch of the initial survey and interim prioritization survey, and before the consensus development meeting. A systematic review of registered, progressing and completed priority setting research settings was completed to assist with the planning and delivery of the study ( Graham et al. , 2020 ).

Research uncertainties related to infertility associated with endometriosis, miscarriage and polycystic ovary syndrome were not considered because of other current or completed research prioritization initiatives ( Horne et al. , 2017 ; Prior et al. , 2017 ).

Research priorities were developed in a three-stage process using consensus methods advocated by the James Lind Alliance (2018) . Potential research uncertainties were gathered through an online survey of healthcare professionals, people with fertility problems and others. Healthcare professionals, including embryologists, fertility specialists and gynecologists, were recruited through the British Fertility Society, Core Outcomes in Women’s Health (CROWN) initiative, Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility Group, Fertility and Sterility Forum, Reproductive Medicine Clinical Study Group and Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. People with fertility problems were recruited through Fertility Europe, an umbrella organization of more than 20 European patient organizations, including Fertility Network UK and Freya, Fertility New Zealand, RESOLVE: The National Infertility Association, and the Women’s Voices Involvement Panel hosted by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Other people could register to participate, including healthcare funders, healthcare regulators and researchers. Recruitment was supported by an active social media campaign. Potential participants received an explanatory video abstract, a plain-language summary and survey instructions. Before completing the survey, participants provided demographic details, including age, gender and geographical location, and information pertaining to their professional or personal experience of infertility. Participants were invited to suggest up to five research questions related to infertility that they considered unanswered.

After the survey had closed, the survey responses were examined in detail within an iterative process. Individual responses were reviewed by at least two members of the steering group. Responses were excluded if they included questions that did not fit the scope of the study, were not answerable by research, related to a specific person or situation or were ambiguous. Incomplete responses were also excluded. The remaining responses were formatted into appropriate research questions.

In addition, research recommendations were identified from a systematic review of clinical practice guidelines and Cochrane systematic reviews. Clinical practice guidelines relevant to infertility were identified by searching bibliographical databases, including Embase, International Guideline Library and MEDLINE, from 2007 to July 2017. Research recommendations were extracted verbatim from clinical practice guidelines. Using a data extraction tool available to the Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility Group, research recommendations were extracted from individual Cochrane reviews evaluating potential fertility treatments. Research recommendations from clinical practice guidelines and Cochrane systematic reviews were reviewed by two members of the steering group and formatted into appropriate research questions. Differences in opinion were resolved by discussion with the steering group.

The long list of potential research questions was organized by allocating individual research questions in four categories: male infertility; female and unexplained infertility, including age-related infertility, ovarian cysts, uterine cavity abnormalities and tubal factor infertility; medically assisted reproduction including ovarian stimulation, IUI and IVF; and ethics, access and organization of care. These categories were identified in consultation with the steering group. Duplicate research questions were removed. Research questions were checked against the published research evidence, including clinical practice guidelines, Cochrane systematic reviews and randomized trials, and those questions considered to be already answered were removed.

The long list of confirmed research uncertainties was entered into an interim prioritization survey. Initial survey participants were invited to participate in the survey. In addition, healthcare professionals, people with fertility problems and others were recruited using the same methods as the initial survey. Before completing the survey, participants provided demographic details, including age, gender and geographical location, and information pertaining to their professional or personal experience of infertility. Participants were invited to select the research uncertainties they considered most important. After the survey had closed, questions were ranked based on the frequency they had been chosen by participants.

The top 15 research uncertainties in each category were discussed during a consensus development meeting (data are presented in the Supplementary Table S1 ). A formal consensus development method, the modified nominal group technique, was used to identify the top 10 research uncertainties for each category ( James Lind Alliance, 2018 ). Healthcare professionals, people with fertility problems and others who had completed the initial or interim prioritization survey were invited to participate. The modified nominal group technique does not depend on statistical power. In consultation with the steering group, the aim was to recruit between 15 and 30 participants, as this number has yielded sufficient results and assured validity in other settings ( Murphy et al. , 1998 ).

Before the consensus development meeting, participants provided demographic details, including age, gender and geographical location, and information pertaining to their professional or personal experience of infertility. Following an introductory session, participants were assigned to one of two groups, each with a facilitator, to discuss the ranking of prioritized research uncertainties. The assignments were pre-specified to ensure a mixture of healthcare professionals, people with fertility problems and others. The groups were provided with a set of cards with an individual research uncertainty printed on each. Each participant was asked to contribute their opinions on the research uncertainties they felt most and least strongly about. Following this initial discussion, participants were invited to discuss the ordering of the research uncertainties. By the end of the session, the research uncertainties were placed in ranked order. The rankings from the two groups were aggregated into a single ranking order and presented to the entire group. Participants were invited to discuss the ordering of the research uncertainties. By the end of the discussion, the research uncertainties were placed in a final ranked order.

The National Research Ethics Service, UK, advised the study did not require formal review.

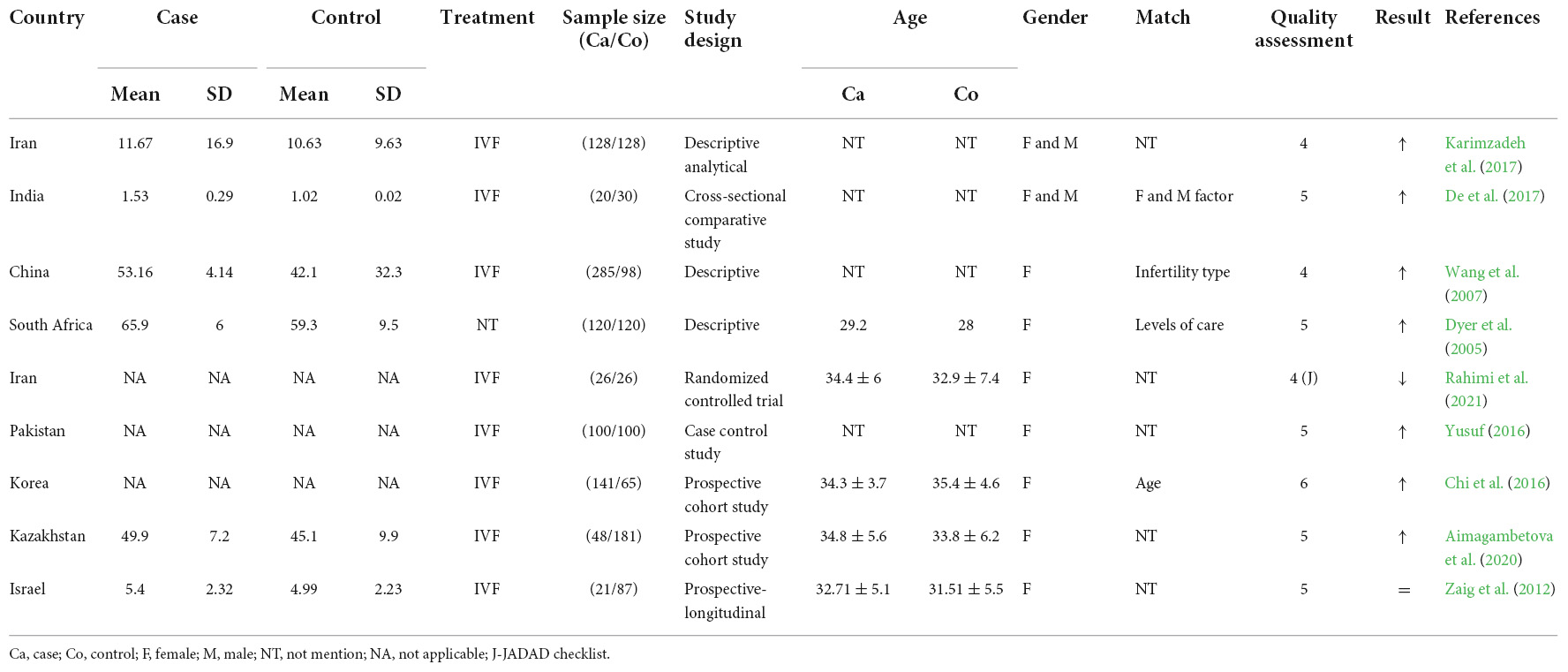

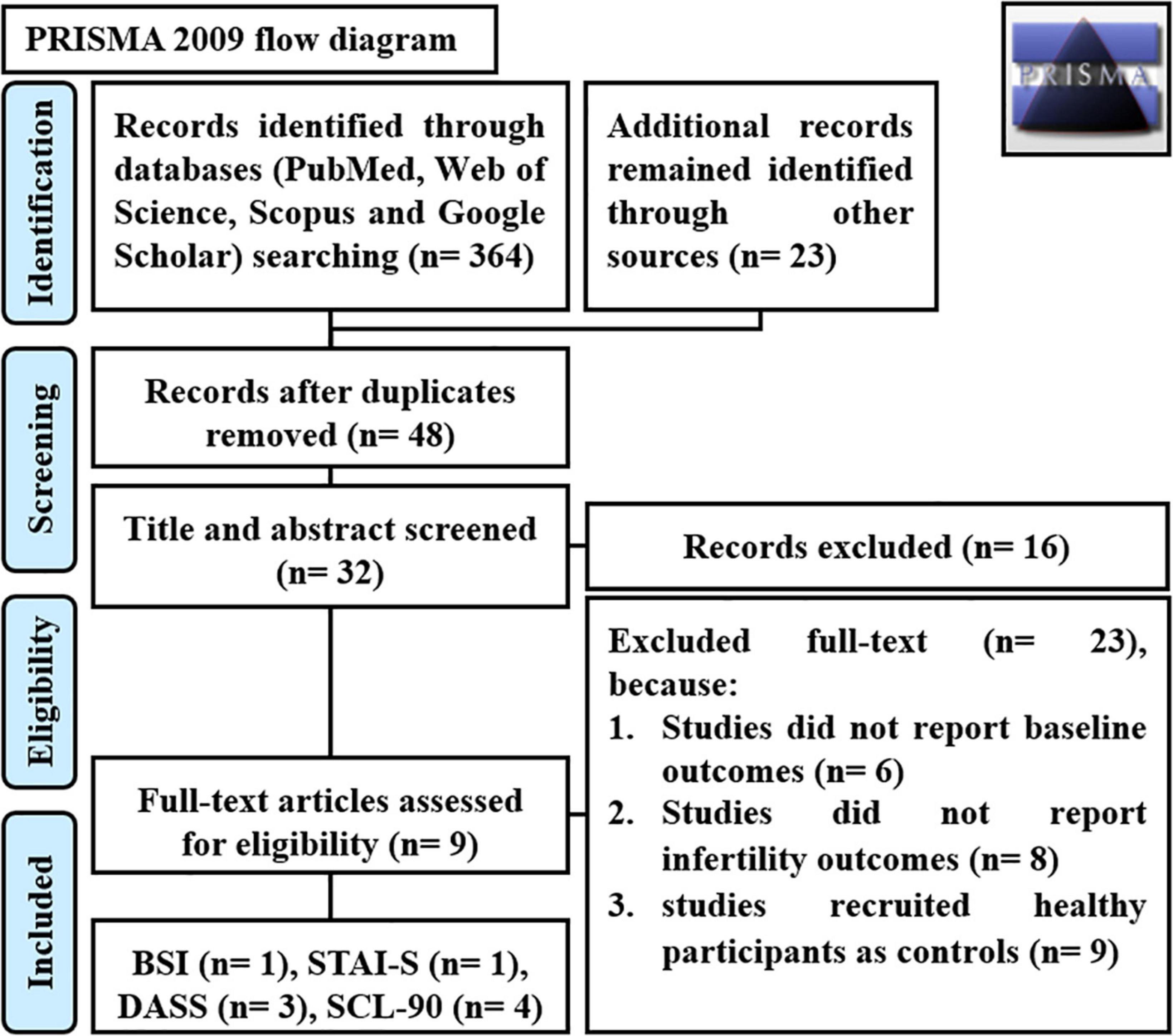

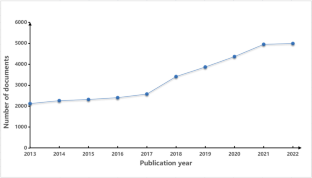

The initial survey was completed by 179 healthcare professionals (46%), 153 people with fertility problems (39%) and 56 others (14%), from 40 countries ( Table I ). Four hundred and twenty-three responses were submitted ( Fig. 1 ). Following review, 136 responses (32%) were excluded. Clinical practice guidelines relevant to infertility were identified by searching bibliographical databases; the search strategy identified 3680 records. After excluding 731 duplicate records, 2949 titles and abstracts were screened. Thirty-two potentially relevant clinical practice guidelines were evaluated. Fourteen clinical practice guidelines met the inclusion criteria, including two guidelines related to infertility in general ( Loh et al. , 2014 ; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2017 ), five guidelines related to male infertility (American Urological Association, 2010; Jarvi et al. , 2010 ; Jungwirth et al. , 2018 ), five guidelines related to uterine anomalies ( Kroon et al. , 2011 ; American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists, 2012 ; Carranza-Mamane et al. , 2015 ; Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, 2016 a, 2017 ) and two guidelines related to medically assisted reproduction ( Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, 2016b ; Penzias et al. , 2017 ). Thirteen research recommendations were extracted from the clinical practice guidelines. The Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility Group provided research recommendations from 162 Cochrane systematic reviews. Two hundred and twenty-three potential research questions were extracted from these research recommendations. A long list of 533 potential research uncertainties was reviewed, 241 duplicate research uncertainties were removed and 51 research uncertainties which had been answered by research were also removed.

Overview of the process of identifying research uncertainties .

Characteristics of the participants in a survey to identify the priorities for future infertility research.

A rationalized list of 231 confirmed research uncertainties was developed, which included 34 research uncertainties related to male infertility, 48 research uncertainties related to female and unexplained infertility, 101 research uncertainties related to medically assisted reproduction and 48 research uncertainties related to ethics, access and organization of care. These confirmed research uncertainties were entered into an interim prioritization survey, which was completed by 143 healthcare professionals, 119 people with fertility problems and 55 others, from 43 countries.

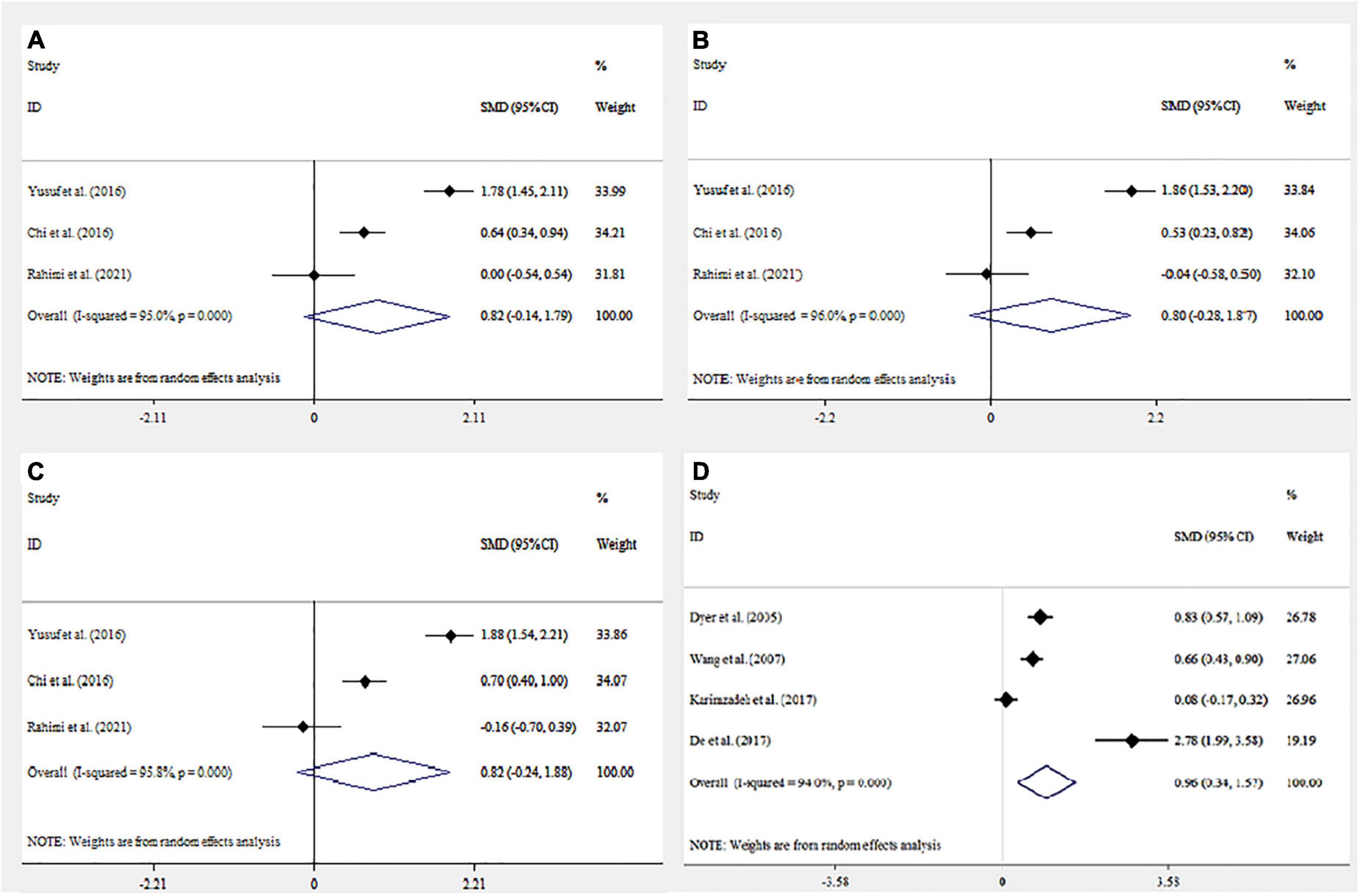

Nineteen healthcare professionals, 14 people with personal experience of infertility and 8 others, from 11 countries, participated in the consensus development meeting. The modified nominal group technique was used to prioritize the top 10 research uncertainties for male infertility, female and unexplained infertility, medically assisted reproduction and ethics, access and organization of care. Fifteen highly prioritized research uncertainties for each category were discussed during the consensus development meeting ( Supplementary Table SI ). The 15 highly prioritized research uncertainties were initially discussed by two separate groups and at the end of the discussion, they ranked the research uncertainties. The first-round ranking is presented in Supplementary Table SI . The rankings from the two groups were aggregated into a single ranking order and discussed by the entire group ( Supplementary Table SI ). Participants were encouraged to discuss and finalize the rank order of the research priorities. The top 10 research priorities are presented in Fig. 2 .

The top 10 priorities for future infertility research in each of the four categories .

The Priority Setting Partnership for infertility has brought together healthcare professionals, people with fertility problems and others to identify the top 10 research priorities for future infertility research. These research priorities are diverse and seek answers to questions regarding prevention, treatment and the longer-term impact, as well as wider contextual issues related to access and public health policy. They highlight the importance of pursuing research which has often been overlooked, including addressing the emotional and psychological impact of infertility, improving access to fertility treatment, particularly in lower resource settings, and securing appropriate regulation. Addressing these priorities will require diverse research methodologies, including laboratory-based science, qualitative and quantitative research and population science.

Strengths and limitations

The James Lind Alliance (2018) has published guidance to inform the design of research priority setting studies. This study has followed this guidance to ensure the research priorities were developed using a clear and transparent process using formal consensus development methods. The study design, development and delivery were also informed by a systematic review of research priority setting studies relevant to women’s health ( Graham et al. , 2020 ). With 388 respondents from 40 countries participating in the initial survey, 317 respondents from 43 countries participating in the interim prioritization survey, and 41 participants from 11 countries included in the consensus development meeting, the global participation achieved in this study should secure the generalizability of the results within an international context. The study included people with fertility problems and they were able to suggest potential research uncertainties during the initial survey, share their views regarding the importance of research uncertainties during the interim prioritization survey and participate fully in the consensus development meeting which prioritized the final research priorities.

This consensus study is not without limitations. Consideration should be given to the representativeness of the study’s participants. For example, when considering the initial survey, there was a higher response from participants who identified as living in Europe (115 participants; 30%). To participate in the initial survey and interim prioritization survey, English proficiency and literacy, a computer and internet access were required. We appreciate that limitations in the representativeness of the sample could impact upon the research uncertainties suggested and prioritized. There is uncertainty regarding the optimal consensus development method to prioritize research uncertainties, and methodological research is required to evaluate different approaches to priority setting and the use of different consensus methods. Further contextual information, including the number of people the research priority impacts upon, the feasibility of answering the research priority, and the resources required to address the research uncertainty could have assisted participants to prioritize research uncertainties. Future methodological research should evaluate the use of contextual information in research priority studies.

Reflections on the research priorities

Reproductive medical care for men has lagged behind that for women. Setting impactful and tractable priorities for male reproduction is consequently a critically important task. For diagnosis, the variation in morphology is extraordinary and counting sperm is challenging, severely limiting our ability to make predictions of male reproductive potential from the standard semen analysis, and begging the question: are there other, better tests of sperm? We need to explore how overall health affects male fertility and whether treating other diseases improves it. Because a man does not live in a vacuum, we need to understand how the environment affects male reproduction. When considering the treatment of male infertility, men often ask what they can do to improve their fertility, and well-conducted studies into diet and nutraceuticals are essential. The endocrine system drives the making of sperm and further evidence is required to understand if hormonal therapy could improve the production of sperm and improve live birth rates.

The priorities for unexplained infertility seek answers to several challenging and long-standing questions, including the prevention of age-related infertility and exploring the role of fibroids, polyps, intrauterine adhesions and uterine septa in unexplained infertility. It is also surprising that it remains unclear what the first-line treatment is for couples with unexplained infertility, IVF or IUI, and the timing of the superior treatment for that couple.

When considering medically assisted reproduction, new large prospective cohorts that consider all variables and use advance methodology will be required to address casual relationships related to implantation failure. Similar complexity will exist when studying oocyte yield and quality over subsequent IVF cycles, even though similar stimulation protocols have been used. The three research priorities concerning the effectiveness of IVF are seeking to identify optimal ovarian stimulation protocols in poor responders, sperm selection techniques and embryo selection. These contrast with the research priorities which explore if, when, and how IUI should be used. To answer these effectiveness questions, well-designed randomized controlled trials will be required ( Wilkinson et al. , 2019b ). The psychological impact of fertility treatment is brought into sharper focus with research priorities related to the emotional and psychological impact of repeated fertility treatment failure and in children following gamete donation. Strong involvement of patient representatives, psychologists and behavioral scientists will be required to establish the appropriate qualitative and quantitative studies to address these important priorities.

The research priorities for ethics, access and organization of care broadly fall into two overarching themes: access and infertility as a public health issue. When considering access, cost is a major barrier to appropriate care, which is reflected in the research priorities aiming to explore interventions to reduce the cost of fertility treatment and increase the availability of fertility treatment in lower-resources settings. Turning to infertility as a public health issue, prevention of infertility should be a key priority for public health initiatives. We need to determine the minimum standard of care that people with fertility problems should expect, especially if we are seeking reimbursements for this care.

Wider context

A prioritized list of research uncertainties, developed to specifically highlight the most pressing clinical needs as perceived by healthcare professionals, people with fertility problems and others, should help funding organizations and researchers to set their future research agenda. The selected list of research uncertainties should serve to focus a discussion regarding the allocation of limited resources.