What Is Digital Literacy and Why Is It Important?

- Updated on March 6, 2024

Digital literacy confines our skills required to understand and use digital technologies. It involves peoples critical thinking and ability to navigate online environments.

In this modern world digital age means more than just using technology. It’s about competence to access, analyze, create, and communicate in an increasingly digital world.

Digital literacy is not only based on a single aspect, it also spans various dimensions including knowledge of basic hardware and software, understanding of internet navigation, and the ethical use of online platforms.

From students to professionals must cultivate these competencies to thrive in modern society. As the digital landscape evolves, staying digitally literate is a continuous journey, essential for participation in the global economy and for engaging with a broader community in an effective, safe, and secure manner.

Digital literacy has become a fundamental skill in the 21st century, related to reading and writing in previous centuries. It bounds a range of abilities that are essential for navigating the technology-saturated world we live in today. Digital Literacy is not merely about knowing how to use a computer; it involves critical thinking and digital problem-solving skills that enable individuals to engage, express, collaborate, and communicate in all aspects of life.

According to the American Library Association (ALA), Digital literacy is the ability to search, evaluate, and communicate information through technology. Beside usage of digital tools it is also a matter of understanding how to use them effectively and responsibly.

This type of literacy helps you in equipping yourself with the skills to navigate the digital realm safely and confidently.

Importance Of Digital Literacy

Relevance of digital literacy cannot be overstated. In this time of digital age, the ability to understand and utilize technology influences every aspect of life—from personal growth to global participation in the digital economy. Some main key points for highlight its significance are:

- Employment Opportunities: Proficiency in digital tools is often a prerequisite for job candidates.

- Educational Resources: Digital skills open up a wealth of learning materials online.

- Global Communication: Internet breaks down geographical barriers, allowing instant interaction with diverse cultures.

- Information Literacy: Being digitally literate aids in discerning the credibility of online content.

Evolution Of Digital Literacy

Concept of digital literacy has changed as technology has advanced. It began with basic ability to operate a computer and now includes a wide range of competencies:

| 1990s | Typing, Basic Computing |

| 2000s | Email, Internet Browsing |

| 2010s | Social Media, Cloud Services |

| 2020s | AI Interaction, Data Analytics |

Progression of digital literacy highlights an ongoing shift toward more complex and integrated uses of technology. To stay current, individuals and organizations must adapt and continuously refine their digital skill sets.

Digital Literacy Skills

Understanding digital literacy skills is essential in our technology-driven age. To thrive in the digital realm, mastering these competencies is crucial as learning to read and write. In essence, digital literacy encompasses a wide array of skills ranging from information evaluation to the responsible use of online platforms. Here, we delve into the core abilities that define a digitally literate individual.

Critical Thinking And Evaluation

In this time of globalization, critical thinking and evaluation are paramount. Digital users must discern credible information from misleading content. This necessitates:

- Analysis of digital resources for accuracy and bias

- Assessment of the relevancy and currency of online data

- Understanding the nuances between opinion and fact

Users who are Equipped with these skills, can navigate the vast digital landscape with a discerning eye by ensuring the veracity and usefulness of consumed information.

Communication And Collaboration

Digital environment extends beyond individual use. Now it’s become a social platform where communication and collaboration reign supreme. Core skills include:

- Effective digital communication using various platforms like email, forums, and social media

- Collaboration using online tools such as shared documents, project management software, and virtual meeting spaces

- Understanding digital etiquette, including tone, privacy, and respect for intellectual property

With these capabilities, one can participate in global conversations, contribute to group projects, and foster community regardless of physical boundaries.

Privacy And Security Awareness

Digital users must be vigilant about privacy and security. Key elements of this critical skill set include:

| Privacy Skill | Description |

| Personal Information Management | Controlling what personal data is shared and understanding how it can be used against you |

| Use of Privacy Settings | Adjusting configurations on social media and other online platforms to protect your identity |

| Security Practices | Implementing strong passwords, using reliable antivirus software, and recognizing phishing attempts |

A solid grounding in these areas is indispensable for ensuring personal and professional data remains secure from various threats.

Principles of Digital Literacy

Digital literacy is grounded in four fundamental principles. Each of the principles forming the core of developing digital literacy skills. Principles of Digital Literacy are as follows:

Understand What You See Online: Digital literacy means knowing how to really get what you’re looking at on the internet. It’s not just about the surface stuff, but digging deeper to grasp the details on digital platforms.

Realize Everything Is Connected: Digital stuff on the web is like a big web of connections. When you know how things link up, you can use digital content better.

Know People Are Different: Remember, online, people come from all walks of life, like different ages, have various educations, jobs, and families. All of these things impact how stuff is made, shared, and stored online.

Learn to Organize What You Find: Think of digital curation as creating your own online library. You can pick and choose what you want to keep, so you can easily find it later.

Above 4 principles are like a map to help you navigate in the digital world. It can help you to understand, connect dots, respect diversity, and stay organized in the vast world of the internet.

Digital Literacy For Lifelong Learning

Embracing the concept of digital literacy is critical in a evolved digital world, especially with its profound impact on lifelong learning. This type of learning is not just confined to the classroom; it extends into every facet of our lives.

Digital literacy enhances the ability to learn new skills, adapt to changing environments, and access vast resources available through technology. Let’s delve into the various ways digital literacy propels learners of all ages towards ongoing personal and professional development.

Professional Development

In today’s fast-paced world, staying competitive means never standing still. Professional development is a perpetual journey, and digital literacy offers the tools necessary for this quest. With digital competencies, individuals can:

- Enhance job performance by keeping up with industry trends and software updates.

- Participate in online workshops, webinars, and courses that fit within busy schedules.

- Collaborate with global experts, gaining insights and exchanging ideas.

Access To Online Resources

Internet is a treasure trove of information and learning materials— from scholarly articles to instructional videos, educational games to digital libraries. Those who are digitally literate unlock the potential to:

- Discover a wide range of resources tailored to specific learning needs and interests.

- Drive self-paced learning by accessing online tutorials, courses, and certification programs.

- Engage with interactive and multimedia content for a more enriching learning experience.

Navigating The Digital Landscape

Digital landscape is vast and navigating it can be daunting without the necessary skills. Digital literacy empowers individuals to navigate the digital world with confidence and ease. By being digitally literate, users can:

- Identify credible information and avoid the pitfalls of misinformation.

- Use various tools and platforms effectively, from social media to cloud storage.

- Protect personal information and privacy through understanding cybersecurity basics.

Digital Literacy Skills and Their Everyday Use

Digital literacy skills necessary for people to navigate in this digital world effectively. These skills can be applied in the following ways:

- Digital media: Skills in digital literacy allows ease and comfort of navigating digital media in everyday life.

- Researching: Individuals will gain the ability to find information and identify reliable sources within different digital platforms.

- Social Inclusivity: Digital literacy skills removes barriers of location, allowing for an increase in social opportunities and connection with those online.

- Understanding Digital Media: With these skills people will be more familiar with common digital media terms and will be able to navigate digital features in their totality.

How to Develop Digital Literacy Skills

Here are some tips from experts to develop and strengthen digital literacy skills.

- Explore with digital tools to understand how they work.

- Stay updated about the latest technologies to remain relevant.

- Focus on technology devices and digital platforms that align with your needs and preferences.

- Be open to learning new things as the digital landscape is always evolving.

- Enroll in online courses to gain insight into different digital technologies and their uses.

- Seek help when encountering new technology devices or platforms.

Frequently Asked Questions On What Is Digital Literacy

What is meant by digital literacy.

Digital literacy refers to an individual’s ability to find, evaluate, and compose clear information through writing and other mediums on various digital platforms. It is crucial for effective communication and problem-solving in the digital age.

Why Is Digital Literacy Important?

Digital literacy is important as it empowers people to navigate technology confidently. This includes safely managing personal data, understanding online resources, and being proficient in digital tools, which are vital skills in today’s tech-driven world.

How Can You Improve Your Digital Literacy?

Improving digital literacy involves regular use of technology, seeking education through online courses or workshops, and practicing critical evaluation of digital content. Staying updated with technological advancements also greatly enhances digital literacy skills.

What Are The Key Components Of Digital Literacy?

Key components of digital literacy include technical skills to use devices, cognitive skills for critical thinking, and ethical understanding for responsible use of technology.

Bottom Line

Nowadays digital literacy is becoming one of the essential parts for individuals navigating this digital world. Development of these skills ensures that individuals can explore digital platforms safely and responsibly.

Related Posts

Why Is Self Care Important

- June 7, 2024

- by projectnewyorker

What Is Adult Literacy And Why Is It Important

- April 24, 2024

Diabetes Workshops in Queens

- April 9, 2024

Teaching critical digital literacy

Critical digital literacy is a set of skills, competencies, and analytical viewpoints that allows a person to use, understand, and create digital media and tools. Related to information literacy skills such as numeracy, listening, speaking, reading, writing and critical thinking, the goal of critical digital literacy is to develop active and engaged thinkers and creators in digital environments. Digital literacy is more than technological understanding or computer skills and involves a range of reflective, ethical, and social perspectives on digital activities.

See also studies of "Critical Media Literacy."

This article is based on work done by Robin Davis as part of the Folger Institute’s Early Modern Digital Agendas (2013) institute. We welcome the addition of resources and readings, particularly those focused on teaching digital literacy from an early modernist perspective and critically analyzing the digital tools related to early modern studies.

- 1 Multi-literacies of digital environments

- 2 Teaching critical early modern digital literacy

- 3 Pedagogical settings for digital literacy

- 4.2 Exercises

- 4.3 Information about tools and infrastructure

- 5.1 Introductions

- 5.2 Short reads

- 5.3 Long reads

Multi-literacies of digital environments

Juliet Hinrichsen and Antony Coombs at the University of Greenwich propose a "5 Resources Model" for articulating the scope and dimensions of digital literacies. The five resources are:

- Decoding : Learners need to develop familiarity with the structures and conventions of digital media, sensitivity to the different modes at work within digital artifacts and confident use of the operational frameworks within which they exist. These skills focus on understanding the navigational mechanisms and movement of the digital landscape (buttons, scrolling, windows, bars); understanding the norms and practices of digital environments (safety and online behavior, community norms, privacy and sharing); understanding common operations (e.g. saving, upload and download, organizing files); recognizing and evaluating stylistics (e.g. the social codes embedded in color, font, transition, and layout choices); and recognizing that different modes of digital texts (twitter streams, video, immersive games) have different characteristics and conventions.

- Meaning Making : This aspect maps onto other well-recognized literacy concepts in recognizing the agency of the learner as a participant in constructing meaning. This dimension of digital literacy focuses on reading , the fluent assimilation of digital content and the ability to follow a narrative across diverse semantic, visual and structural elements; relating , or recognizing relationships between new and existing knowledge and adapting mental models; and expressing , or the capacity to translate a purpose, intention, feeling or idea into a digital form.

- Using : Learners need to develop the ability to effectively and creatively deploy digital tools. This includes finding the tool and the requisite evaluation of different tool options, effectively apply tools and techniques, employ problem solving, and have the confidence to explore, experiment, and innovate to create solutions with imaginative approaches, techniques, or content.

- Analyzing : Learners need to develop the ability to make informed judgements and choices in the digital domain. This includes deconstructing digital resources to analyze their constituent parts, selecting resources and tools, and interrogating the provenance, purpose, and structures that affect digital content and influence its output.

- Persona : Sensitivity to the issues of reputation, identity and membership within different digital contexts. In identity building, learners develop a sense of their own role in digital environments; reputation management emphasizes the importance of building and maintaining both individual and community reputations as assets; while participation focuses on the nature of the collaborative (both synchronous and asynchronous) contributions that make up many digital projects and their ethical and cultural challenges.

Teaching critical early modern digital literacy

Students encounter early modern texts, images, and objects through an increasing array of digital tools and sources. By reading an edited version of Macbeth via the Folger Digital Texts, critiquing a digital facsimile of a pamphlet on Early English Books Online, or navigating the Agas Map at the Map of Early Modern London , digital texts and tools allow for interactive and expansive exploration of early modern topics. In encouraging students to engage with early modern literature and history through these tools, we also need to provide them with the skills to analyze the tool, its intended audiences, its affordances and limitations. By teaching students how to assess digital editions and tools critically, we can prepare them not only to select the best tools for their purpose, but also provide the skills necessary for further development of digital texts, tools, and resources. Critical digital literacy is the first step towards digital authorship.

Pedagogical settings for digital literacy

Critical digital literacy, writ broadly, is taught in a variety of settings, including humanities and information courses; public, academic, and special collections libraries; and K-12 classrooms and after-school programs. The articles listed below present a variety of perspectives on the benefits of critical digital literacy and point to some of the fields in which discussions of critical digital literacy are taking place.

- Graduate education; Rhetoric and Composition.

- Undergraduate education; English Department.

- High school education and postsecondary education; English, Art, Preservice teacher education.

- High School, Academic standards and student attitudes.

- Undergraduate education; Academic libraries.

Teaching resources and exercises

Many digital literacy exercises are designed to make the affordances of specific tools visible. Many students treat digital humanities tools as "black boxes": opaque systems in which a user provides input and receives a product, but does not have information about what happens in between. The goal of many of these exercises is to make the box a little less opaque and open up digital humanities tools, programs, and databases to criticism. We want students to question the assumptions and choices made in the selection, organization, and presentation of content and understand what their tools are doing for them.

http://dhbox.org/ : streamlines installation processes and provides a digital humanities laboratory in the cloud through simple sign-in via a web browser.

- How to see through the cloud : using traceroute to walk through the physical network of the Internet

- Governing Algorithms: Provocation piece : short essay split into 38 provocations concerning algorithms, policy, and practice. #21 is a great discussion starter, courtesy of Solon Barocas, Sophie Hood, and Malte Ziewitz.

- Teaching with Lingfish : Using the Early Modern Recipe Archive, Luna, the OED, and EEBO to examine how different repositories deal with fish, courtesy of Nancy Simpson-Younger.

Information about tools and infrastructure

- The Basement : what an internet hub for a major American city looks like, courtesy of Cabel Sasser.

Further reading

Introductions.

- Folgerpedia's Glossary of digital humanities terms

- A career-focused and skills-focused list of resources by the Department of Commerce. This page allows practitioners in service-oriented organizations—such as libraries, schools, community centers, community colleges, and workforce training centers—to find digital literacy content.

- This section looks at the various aspects and principles relating to digital literacy and the many skills and competencies that fall under the digital literacy umbrella. The relationship between digital literacy and digital citizenship is also explored and tips are provided for teaching these skills in the classroom.

- Kellner, Douglas and Jeff Share, "Toward Critical Media Literacy: Core concepts, debates, organizations, and policy," Discourse: studies in the cultural politics of education . 26, no. 3 (September 2005): 369-86.

Short reads

- Practicing Freedom in the Digital Library by Barbara Fister in Library Journal (2013)

- Beyond Citation student project at the CUNY Graduate Center (2014)

- Digital Humanities Pedagogy: Practices, Principles, and Politics edited by Brett D. Hirsch (2012)

- "Hacking the Classroom: Eight Perspectives" Eds. Mary Hocks and Jentry Sayers. Computers and Composition Online . (Spring 2014).

- Suggested readings from CRTCLDGTL , a reading group at Northwestern

- Never Neutral: Critical Approaches to Digital Tools & Culture in the Humanities , essay by Josh Honn (2013)

- Folger Institute

- Digital humanities

- Bibliography

Digital Pioneers: How a D-Rated District Led the Nation in OER Adoption

- check_box Increase Teacher Adoption

- check_box Increase Parent Involvement

- check_box Increase Student Success

Discover how One District Transformed their Classroom through Personalized Learning & OER Adoption arrow_forward

- Get Started

Critical Thinking: The Key to Digital Literacy

By: fishtree - november 10, 2014.

How should we define digital literacy? Educational leader and PhD student, Lynnea West, explains her research on the principle ways of redefining education through technology, using digital literacy as a key driver: “I would hope that moving forward, we just call them ‘literacies’ and they’re just considered essential components of good literacy practices. We’re living in an online world and digital tools are our reality , so literacy in the broader context is just how we make meaning of what we’re reading or interpreting and how that joins together with our place in the world.”

The concept of digital literacy has been broken down in numerous attempts to define what constitutes a ‘digital native’ and what skills are central to our understanding and interpretation of digital content. Lynnea argues the key to fostering a digital mindset lies in the emphasis of critical thinking. “Critical thinking has always been emphasized in literacy skills but they become much more apparent when it comes to interpreting digital content”, she says. Referencing the work of Dr. Julie Coiro and Donald J. Leu, Lynnea explains, “there’s actually no real correlation between how well a student reads on paper and how well a student can read in a digital environment, so you have to teach those skills and strategies really explicitly about analyzing and evaluating.”

The Evolution of Literacy

Lynnea outlines how digital technology has changed the way we interact with text, taking a more collaborative approach to the way in which we make meaning. “Before, it was like: ‘Here’s your paper, do your worksheet’. Now, we have the opportunity to represent our thinking using visual images in a collage, or by creating a video, so we have a lot of different ways to respond to reading. We also get the opportunity to create meaning together. For example, when responding to a concept, you can create your meaning and demonstrate that through a video. Then, your students can reply to that video and the story gets continued. So it’s not just this singular piece anymore, it’s this dynamic and multimodal process, it’s a back and forth, and it’s collaborative . ”

Lynnea describes technology’s potential to give every single student a voice, showcasing student creativity and critical thinking skills like never before. “If you have a student who is somewhat quiet in a face-to-face conversation, they may just need that time to process, think, listen and then reflect later, and have their voice heard. So you can use technology to increase student voice in a way that they’d never have been able to before.”

The Digital Native

There has been widespread debate on the topic of the digital native, and whether or not the digital generation should inherit the title. Lynnea explains her logic that it’s not simply a question of ‘being’, but rather of ‘becoming’, a digital native. “I’m not in the generation of the digital native but I can certainly navigate my way through technology”, she says. “I don’t think it’s as simple as you are or you aren’t, I think you can be developed in whatever it is that you want to do. Anything, if you have that growth mindset, you can take to the next level .”

While most educators are moving towards this digital mindset, many remain reluctant to embrace the ‘digital native’ status. Lynnea argues that much of this reluctance boils down to the fear of letting go. “I think there are some teachers who have been teaching with pretty impressive results, who feel a sense of mastery, and it’s really uncomfortable to let that go”, she says.

Blurred Lines

Another reason for such reluctance, Lynnea explains, is the blurring of lines between students and teacher, as the traditional school structure begins to change shape. With educators now being urged to join in the learning cycle with their students, the idea of taking a back seat remains frightening to some. “It’s going to continue to change and evolve, and I think the students will be the drivers of that, and that makes the lines a little blurry between teachers and students… Who’s the learner? And who’s the teacher? ”

While many may grimace at the idea of these blurred lines, Lynnea is excited at the prospect of students taking the reigns. “To me, this is awesome. I have two kids, and if they can be put in the role of leader at the age of eleven, then great. That’s a sense of mastery and accomplishment. It’s exciting to me to have those roles a little more blurry”, she says.

As literacies continue to evolve and adapt to our more complex, digital surroundings, the skills at the center are gaining more significance than ever. Could critical thinking be the key driver in our quest for the ‘digital native’? Should educators take a step back to promote the innovative mindset of the 21st century? Are we essentially foreigners in the land of the digital generation? Perhaps it’s time for us to indulge in some critical thinking of our own.

P.S. If you liked this post, you might want to check out fishtree.com . Start teaching with the 21st century learning platform today… the ideal tool for adaptive, blended and mobile learning!

About the author:

Lorna Keane is a teacher of French, English and ESL. She specializes in language teaching and has taught in second and third-level institutions in several countries. She holds a B.A in languages and cultural studies and an M.A in French literature, theory and visual culture. Follow her on Twitter or connect on LinkedIn .

Follow @fishtree_edu

Image credits: Lucélia Ribeiro / CC BY 2.0

Programs submenu

Regions submenu, topics submenu, is it me or the economic system changing chinese attitudes toward inequality: a big data china event, a complete impasse—gaza: the human toll, ukraine and transatlantic security on the eve of the nato summit, new frontiers in uflpa enforcement: a fireside chat with dhs secretary alejandro mayorkas.

- Abshire-Inamori Leadership Academy

- Aerospace Security Project

- Africa Program

- Americas Program

- Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy

- Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative

- Asia Program

- Australia Chair

- Brzezinski Chair in Global Security and Geostrategy

- Brzezinski Institute on Geostrategy

- Chair in U.S.-India Policy Studies

- China Power Project

- Chinese Business and Economics

- Defending Democratic Institutions

- Defense-Industrial Initiatives Group

- Defense 360

- Defense Budget Analysis

- Diversity and Leadership in International Affairs Project

- Economics Program

- Emeritus Chair in Strategy

- Energy Security and Climate Change Program

- Europe, Russia, and Eurasia Program

- Freeman Chair in China Studies

- Futures Lab

- Geoeconomic Council of Advisers

- Global Food and Water Security Program

- Global Health Policy Center

- Hess Center for New Frontiers

- Human Rights Initiative

- Humanitarian Agenda

- Intelligence, National Security, and Technology Program

- International Security Program

- Japan Chair

- Kissinger Chair

- Korea Chair

- Langone Chair in American Leadership

- Middle East Program

- Missile Defense Project

- Project on Critical Minerals Security

- Project on Fragility and Mobility

- Project on Nuclear Issues

- Project on Prosperity and Development

- Project on Trade and Technology

- Renewing American Innovation Project

- Scholl Chair in International Business

- Smart Women, Smart Power

- Southeast Asia Program

- Stephenson Ocean Security Project

- Strategic Technologies Program

- Wadhwani Center for AI and Advanced Technologies

- Warfare, Irregular Threats, and Terrorism Program

- All Regions

- Australia, New Zealand & Pacific

- Middle East

- Russia and Eurasia

- American Innovation

- Civic Education

- Climate Change

- Cybersecurity

- Defense Budget and Acquisition

- Defense and Security

- Energy and Sustainability

- Food Security

- Gender and International Security

- Geopolitics

- Global Health

- Human Rights

- Humanitarian Assistance

- Intelligence

- International Development

- Maritime Issues and Oceans

- Missile Defense

- Nuclear Issues

- Transnational Threats

- Water Security

The Digital Literacy Imperative

Photo: Yasuyoshi Chiba/AFP/Getty Images

Table of Contents

Brief by Romina Bandura and Elena I. Méndez Leal

Published July 18, 2022

Available Downloads

- Download the CSIS Brief 1106kb

The Issue:

- Digital literacy has become indispensable for every global citizen, whether to communicate, find employment, receive comprehensive education, or socialize. Acquiring the right set of digital skills is not only important for learning and workforce readiness but also vital to foster more open, inclusive, and secure societies.

- Digital literacy , like other competencies, should start at school. However, many education systems lack the proper infrastructure, technological equipment, teacher training, or learning benchmarks to effectively integrate digital literacy into curriculums.

Effective strategies to address digital literacy and skill-building will require public and private investments in digital infrastructure, policy and governance frameworks, and training in the use of digital technologies.

- The U.S. government—particularly through the work of the U.S. Agency for International Aid (USAID) , its premier development agency—can partner with the private sector, local organizations, and civil society to lead and support an international coalition on digital skills. It can lead in this space by convening a multistakeholder working group on digital skills, investing in skills development among vulnerable and excluded populations (such as women and girls), and enhancing digital skills in basic curriculums.

Introduction

Reading, writing, and numeracy: these are foundational skills people learn at school and continue using throughout their lifetimes. But as societies evolve and technology progresses, the learning needs and demands of one generation change for the next. Curriculums in educational institutions must keep up with these changes to reflect the new realities. They do so by removing outdated content, incorporating new disciplines, and innovating with new educational tools and techniques. While previous American generations learned Latin and shorthand, current generations learn Spanish or French and practice typing. In many public schools across the United States, cursive handwriting is no longer taught. Children now practice writing and typing using new technology such as tablets and computers, not typewriters. In advanced countries, educational equipment such as blackboards, chalkboards, and even whiteboards have been replaced with high-tech tools such as Promethean boards.

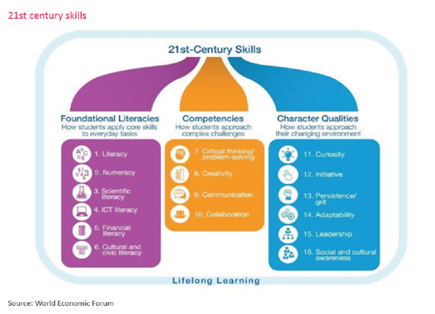

While numeracy and basic literacy are still fundamental to learning, digital literacy has emerged as another critical life skill and is now, per the World Economic Forum, part of the twenty-first-century toolkit (see Figure 1). Beyond basic literacy, digital skills have become indispensable for every global citizen, whether to communicate, find employment, receive comprehensive education , or socialize. More than 90 percent of professional roles in across sectors in Europe require a basic level of digital knowledge and understanding. This need has become even more evident during the Covid-19 pandemic, making it more urgent for countries to embrace digital technologies and their associated skills.

Figure 1: The Skills Toolkit for the Twenty-First Century

To keep up with technological advancements, companies need to hire employees that have the right skills. However, workforces are not always equipped with the requisite digital skills, and businesses often struggle to find qualified talent. Digital skills are at a premium, even in advanced economies. For instance, the European Union’s Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) shows that approximately 42 percent of Europeans lack basic digital skills, including 37 percent of those in the workforce. Women are particularly underrepresented in tech-related professions; only one in six information and communications technology (ICT) specialists and one in three science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) graduates are women.

However, acquiring the right set of digital skills is not only important for learning and workforce readiness: digital skills are also vital to fostering more open, inclusive, and secure societies. When people interact with digital infrastructure, they need to be aware of the privacy and data risks as well as cybersecurity challenges (e.g., ransomware and phishing attacks). Thus, digital literacy also includes handling security and safety challenges created by technology. At the same time, with the rise of digital authoritarianism , misinformation, and disinformation , as well as limitations on personal freedoms, it is equally important to maintain a values framework for digital transformation.

Acquiring the right set of digital skills is not only important for learning and workforce readiness: digital skills are also vital to fostering more open, inclusive, and secure societies.

Digital Literacy in a Continuum

What exactly does “digital literacy” entail? There are many competing definitions, but it can be thought of as the ability to use digital technologies—both hardware and software—safely and appropriately. According to the UN Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization ( UNESCO ) , this includes competencies such as using ICT, processing information, and engaging with media. However, digital skills do not exist in a vacuum and interact with other capabilities such as general literacy and numeracy, social and emotional skills, critical thinking, complex problem solving, and the ability to collaborate.

Digital skills also have different degrees of complexity. According to the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), digital skills exist along a continuum ranging from basic to intermediate to advanced (see Figure 2). Basic digital skills comprise the effective use of hardware (e.g., typing or operating touch-screen technology), software (e.g., word processing, organizing files on laptops, and managing privacy settings on mobile phones), and internet/ICT tasks (e.g., emailing, browsing the internet, or completing an online form). Intermediate digital skills comprise the ability to critically evaluate technology or create content; they are characterized as “job-ready skills” and include desktop publishing, digital graphic design, and digital marketing. Finally, specialists use advanced digital skills in ICT professions such as computer programming and network management. Many technology-sector jobs now require advanced digital skills related to such innovations as artificial intelligence (AI), big data, natural language processing, cybersecurity, the Internet of Things (IoT), software development, and digital entrepreneurship.

Figure 2: The Digital Skills Continuum

Digital literacy, like other competencies, should start at school. But many education systems are not equipped to teach children these skills because they lack the proper infrastructure, technological equipment, teacher training, curriculum, or learning benchmarks. This gap is further pronounced in developing countries. A 2020 study conducted in Chile, Ecuador, Mexico, and Peru assessed teachers’ digital skills and readiness for remote learning, finding that 39 percent of teachers were only able to execute basic tasks, 40 percent were able to perform basic tasks and use the internet to browse or send email, and only 13 percent of teachers could do more complex functions.

Moreover, enhancing digital literacy goes beyond providing access to computers, smartphones, or tablets. Although nearly half of the world is still offline, supplying hardware alone will be insufficient to acquire digital literacy. That is, beyond the estimated $428 billion in investment required to close the digital coverage gap, there is little information on the total investment or demand for addressing this issue. There are alternative models for delivering digital literacy—particularly to vulnerable and under-connected communities—including interactive voice response (IVR), solar-powered devices, downloadable learning, and feature phones. Despite the many innovations in this space, there is scant evidence of what works or what can be scaled.

Although nearly half of the world is still offline, supplying hardware alone will be insufficient to acquire digital literacy.

Multilateral Efforts on Digital Literacy

The need to equip current and future generations with the necessary skills is captured in the United Nations’ sustainable development goals (SDGs). Under target 4.4, the United Nations nudges countries to increase the proportion of youth and adults who have skills relevant for the job market. More specifically, indicator 4.4.1 calls on governments to measure the proportion of youth and adults with ICT skills.

In this regard, international organizations, the private sector, and national governments have established initiatives on digital literacy (see text box). For example, frameworks that measure digital skills target different societal sectors, including primary and secondary schools, government structures, and specific industries. The most relevant frameworks include the ITU’s Digital Toolkit, the Eurostat digital skills indicator survey, and the European Union’s Digital Competence 2.0 Framework for Citizens . In addition, the DQ Framework aggregates 24 leading international frameworks to promote digital literacy and digital skills around the world.

Digital literacy is both an international and local issue. Countries and regions will require tailored approaches to meet their unique needs and contexts. Some governments are putting together strategic plans to increase citizens’ digital literacy, albeit for different purposes. For example, the Republic of Korea has prioritized fostering digital skills in public administration officials to improve efficiency in delivering public services. Meanwhile, Oman has used Microsoft’s Digital Literacy curriculum to improve the ICT industry’s workforce and prepare youth for employment. In 2019, the Ukrainian government launched a national digital education platform called Diia Digital Education offering over 75 courses and teaching materials to its citizens. Through its skills agenda, the European Union has set a target to ensure that 70 percent of adults have basic digital skills by 2025 and to cut the percentage of teens who underperform in computing and digital literacy from 30 percent in 2019 to 15 percent by 2030. Ghana has partnered with the World Bank’s Digital Economy for Africa initiative, launching a $212 million “eTransform” program to increase training, mentoring, and access to technologies.

Digital literacy is both an international and local issue. Countries and regions will require tailored approaches to meet their unique needs and contexts.

Examples of International Digital-Skills Initiatives

USAID released its first four-year digital strategy plan in 2020 to achieve safe and inclusive digital ecosystems in developing countries. In April 2022, the agency also released its Digital Literacy Primer , which aims to raise awareness on how digital literacy can contribute to global development goals and what role USAID can play to improve digital-literacy programming and initiatives.

UNESCO has partnered with Pearson’s Project Literacy program to create digital-literacy guidelines for nongovernmental organizations, governments, and the private sector to utilize when pursuing digital-literacy projects. UNESCO’s Institute for Information Technologies in Education (IITE) hosts discussion events, provides training programs to educators and schools, and advocates for digital-literacy education policies.

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s (OECD) Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) conducted a report on access to digital technology, in which it promoted initiatives to combat growing digital divides. In addition, the OECD’s Going Digital project explains to policymakers why digital development is crucial.

The ITU operates projects around the world centered on digital inclusion through “digital transformation centers,” “smart villages,” and digitizing government services. The ITU and Cisco Systems have also partnered to address digital-skills and -literacy gaps in developing countries.

The World Bank ’s Development Data Group was implemented to expand access and promote digital-skills development across multiple sector In World Development Report 2021: Data for Better Lives , the World Bank offers recommendations for digital-literacy campaigns and strategies. This builds upon the multiple projects in several regions it has instituted to support digital literacy since 2006, as well as its joint program with EQUALS Global Partnership and local organizations to increase digital skills and literacy for women and girls in Rwanda, Nigeria, and Uganda.

The UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF) explored digital-literacy frameworks in 2019, seeking to partner with multiple stakeholders and expand its research on this issue. Thus far, UNICEF primarily researches and publishes reports on digital-literacy plans but does include related goals and resources in its various education programs .

DO4Africa aims to expand digital innovation and projects on the continent, including by promoting digital literacy .

The Role of the United States in Digital Literacy

The Covid-19 pandemic has made evident the need to increase the adoption of innovative digital solutions and, in turn, build the skills that can accompany this wave of digitization. While the impact of the pandemic has increased opportunities for digital payments, e-services, and telework, digital technologies will not foster development and inclusion on their own. Effective strategies to address digital literacy and skill-building will require public and private investments in digital infrastructure, policy and governance frameworks, and training in the use of digital technologies.

In this regard, the U.S. government—particularly through the work of USAID, its premier development agency—can partner with the private sector, local organizations, and civil society to lead and support an international coalition on digital skills. Through its Digital Strategy , USAID is breaking silos internally, incorporating “digital” as an all-encompassing issue across the agency’s strategies and operations. This puts the United States ahead of the curve: Among bilateral donor agencies in the OECD, only 12 countries have digitalization strategies within their organizations.

First, the United States should convene a multistakeholder working group on digital skills. Although many important institutions are working in this sector (including UNESCO, the ITU, the OECD, and the World Bank), USAID can play an important role in supporting a values-based approach to digital transformation and digital literacy. Donors need to think carefully about the principles and values being embedded into digital systems. Without strong guiding standards (such as the Principles for Digital Development) and values for these systems, we risk empowering malign actors instead of lifting people out of poverty; we risk enabling surveillance, disinformation, and digital authoritarianism instead of personal freedom and financial inclusivity; and we risk the wrong kind of systemic change by destabilizing the financial system and entrenching existing inequalities.

To ensure maximum lasting impact, public and private organizations need to work together in a skills-development ecosystem, with more actors connecting through digital platforms and learning. As the saying goes, “If you want to walk fast, you walk alone; if you want to walk far, you walk together.” In this regard, USAID has a comparative advantage in engaging with the private sector. Specifically, the agency could convene a multi-pronged approach that effectively coordinates efforts from the international donor community, multilateral institutions, local governments, and companies. This includes taking stock of existing collaborations and developing a single channel through which donors can communicate and coordinate. The U.S. government and relevant agencies should engage at not just the bilateral level but also multilaterally in order to maintain leadership roles across donor and recipient initiatives and participate in discussions to address digital-literacy challenges such as infrastructure and access.

Second, the United States and its partners should learn from previous digital-transformation approaches and elevate and invest in skills development among vulnerable and excluded populations such as women and girls. In low- and middle-income countries, fewer than 50 percent of women have access to the internet, and far fewer have the skills to effectively and safely interact online, thus impeding their social and economic opportunities . Investment in general education, in addition to digital education, will also be critical to developing twenty-first-century literacy and skills. Digital literacy is a very nuanced topic with many different elements, but research on related programming and interventions is not as robust. USAID can promote and facilitate evidence-based learning around what types of interventions work best for digital literacy—for now there is a large amount of innovation in this field, but there is also a lack of scale.

Third, in partnership with the donor community, USAID should work to enhance digital skills in basic curriculums and identify critical gaps in education systems. The earlier digital education begins, the more attainable a high degree of digital literacy is. Digital Education would improve the overall quality of life in low- to middle-income countries and equip future workforces with necessary skills in a rapidly digitizing world. Where possible, integrating technology and digital skills into curriculums will allow for early development of digital literacy, allowing students to familiarize themselves with modern methods of communication and accessing information. These initiatives will need to be adapted to different countries’ and communities’ local and cultural contexts to maximize learning impact and ensure minimal exclusion. USAID can also assist governments in establishing upskilling initiatives to train older workers and employers in how to integrate digital technologies into businesses and sectors. These initiatives should emphasize preventing “brain drain” and retaining local digital talent. Improving ICT infrastructure will also increase the ability for people to access programs and integrate digital skills into their daily lives.

Digitalization is no longer a sectoral issue but is all-encompassing across sectors and actors. In that regard, “ the future is already here ”—and investing in digital-literacy programs will be critical to establishing global leadership in the digital age. Meeting digital demands and supporting digital transitions worldwide will be essential for global development programming and progressing toward a free, sustainable, and equitable future. In a world that is increasingly online, accessing technologies and the proper digital skills will be critical for countries’ development, security, and inclusion.

Romina Bandura is a senior fellow with the Project on Prosperity and Development and the Project on U.S. Leadership in Development at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, D.C. Elena I. Méndez Leal is a program coordinator and research assistant with the Project on Prosperity and Development at CSIS.

This brief is made possible by the generous support from USAID and DAI.

CSIS Briefs are produced by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a private, tax-exempt institution focusing on international public policy issues. Its research is nonpartisan and nonproprietary. CSIS does not take specific policy positions. Accordingly, all views, positions, and conclusions expressed in this publication should be understood to be solely those of the author(s).

© 2022 by the Center for Strategic and International Studies. All rights reserved.

Romina Bandura

Elena I. Méndez Leal

Programs & projects.

- Education, Work, and Youth

Media and Information Literacy, a critical approach to literacy in the digital world

What does it mean to be literate in the 21 st century? On the celebration of the International Literacy Day (8 September), people’s attention is drawn to the kind of literacy skills we need to navigate the increasingly digitally mediated societies.

Stakeholders around the world are gradually embracing an expanded definition for literacy, going beyond the ability to write, read and understand words. Media and Information Literacy (MIL) emphasizes a critical approach to literacy. MIL recognizes that people are learning in the classroom as well as outside of the classroom through information, media and technological platforms. It enables people to question critically what they have read, heard and learned.

As a composite concept proposed by UNESCO in 2007, MIL covers all competencies related to information literacy and media literacy that also include digital or technological literacy. Ms Irina Bokova, Director-General of UNESCO has reiterated significance of MIL in this media and information landscape: “Media and information literacy has never been so vital, to build trust in information and knowledge at a time when notions of ‘truth’ have been challenged.”

MIL focuses on different and intersecting competencies to transform people’s interaction with information and learning environments online and offline. MIL includes competencies to search, critically evaluate, use and contribute information and media content wisely; knowledge of how to manage one’s rights online; understanding how to combat online hate speech and cyberbullying; understanding of the ethical issues surrounding the access and use of information; and engagement with media and ICTs to promote equality, free expression and tolerance, intercultural/interreligious dialogue, peace, etc. MIL is a nexus of human rights of which literacy is a primary right.

Learning through social media

In today’s 21 st century societies, it is necessary that all peoples acquire MIL competencies (knowledge, skills and attitude). Media and Information Literacy is for all, it is an integral part of education for all. Yet we cannot neglect to recognize that children and youth are at the heart of this need. Data shows that 70% of young people around the world are online. This means that the Internet, and social media in particular, should be seen as an opportunity for learning and can be used as a tool for the new forms of literacy.

The Policy Brief by UNESCO Institute for Information Technologies in Education, “Social Media for Learning by Means of ICT” underlines this potential of social media to “engage students on immediate and contextual concerns, such as current events, social activities and prospective employment.

UNESCO MIL CLICKS - To think critically and click wisely

For this reason, UNESCO initiated a social media innovation on Media and Information Literacy, MIL CLICKS (Media and Information Literacy: Critical-thinking, Creativity, Literacy, Intercultural, Citizenship, Knowledge and Sustainability).

MIL CLICKS is a way for people to acquire MIL competencies in their normal, day-to-day use of the Internet and social media. To think critically and click wisely. This is an unstructured approach, non-formal way of learning, using organic methods in an online environment of play, connecting and socializing.

MIL as a tool for sustainable development

In the global, sustainable context, MIL competencies are indispensable to the critical understanding and engagement in development of democratic participation, sustainable societies, building trust in media, good governance and peacebuilding. A recent UNESCO publication described the high relevance of MIL for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

“Citizen's engagement in open development in connection with the SDGs are mediated by media and information providers including those on the Internet, as well as by their level of media and information literacy. It is on this basis that UNESCO, as part of its comprehensive MIL programme, has set up a MOOC on MIL,” says Alton Grizzle, UNESCO Programme Specialist.

UNESCO’s comprehensive MIL programme

UNESCO has been continuously developing MIL programme that has many aspects. MIL policies and strategies are needed and should be dovetailed with existing education, media, ICT, information, youth and culture policies.

The first step on this road from policy to action is to increase the number of MIL teachers and educators in formal and non-formal educational setting. This is why UNESCO has prepared a model Media and Information Literacy Curriculum for Teachers , which has been designed in an international context, through an all-inclusive, non-prescriptive approach and with adaptation in mind.

The mass media and information intermediaries can all assist in ensuring the permanence of MIL issues in the public. They can also highly contribute to all citizens in receiving information and media competencies. Guideline for Broadcasters on Promoting User-generated Content and Media and Information Literacy , prepared by UNESCO and the Commonwealth Broadcasting Association offers some insight in this direction.

UNESCO will be highlighting the need to build bridges between learning in the classroom and learning outside of the classroom through MIL at the Global MIL Week 2017 . Global MIL Week will be celebrated globally from 25 October to 5 November 2017 under the theme: “Media and Information Literacy in Critical Times: Re-imagining Ways of Learning and Information Environments”. The Global MIL Feature Conference will be held in Jamaica under the same theme from 24 to 27 October 2017, at the Jamaica Conference Centre in Kingston, hosted by The University of the West Indies (UWI).

Alton Grizzle , Programme Specialist – Media Development and Society Section

Other recent news

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

A systematic review on digital literacy

Hasan tinmaz.

1 AI & Big Data Department, Endicott College of International Studies, Woosong University, Daejeon, South Korea

Yoo-Taek Lee

2 Endicott College of International Studies, Woosong University, Daejeon, South Korea

Mina Fanea-Ivanovici

3 Department of Economics and Economic Policies, Bucharest University of Economic Studies, Bucharest, Romania

Hasnan Baber

4 Abu Dhabi School of Management, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

Associated Data

The authors present the articles used for the study in “ Appendix A ”.

The purpose of this study is to discover the main themes and categories of the research studies regarding digital literacy. To serve this purpose, the databases of WoS/Clarivate Analytics, Proquest Central, Emerald Management Journals, Jstor Business College Collections and Scopus/Elsevier were searched with four keyword-combinations and final forty-three articles were included in the dataset. The researchers applied a systematic literature review method to the dataset. The preliminary findings demonstrated that there is a growing prevalence of digital literacy articles starting from the year 2013. The dominant research methodology of the reviewed articles is qualitative. The four major themes revealed from the qualitative content analysis are: digital literacy, digital competencies, digital skills and digital thinking. Under each theme, the categories and their frequencies are analysed. Recommendations for further research and for real life implementations are generated.

Introduction

The extant literature on digital literacy, skills and competencies is rich in definitions and classifications, but there is still no consensus on the larger themes and subsumed themes categories. (Heitin, 2016 ). To exemplify, existing inventories of Internet skills suffer from ‘incompleteness and over-simplification, conceptual ambiguity’ (van Deursen et al., 2015 ), and Internet skills are only a part of digital skills. While there is already a plethora of research in this field, this research paper hereby aims to provide a general framework of digital areas and themes that can best describe digital (cap)abilities in the novel context of Industry 4.0 and the accelerated pandemic-triggered digitalisation. The areas and themes can represent the starting point for drafting a contemporary digital literacy framework.

Sousa and Rocha ( 2019 ) explained that there is a stake of digital skills for disruptive digital business, and they connect it to the latest developments, such as the Internet of Things (IoT), cloud technology, big data, artificial intelligence, and robotics. The topic is even more important given the large disparities in digital literacy across regions (Tinmaz et al., 2022 ). More precisely, digital inequalities encompass skills, along with access, usage and self-perceptions. These inequalities need to be addressed, as they are credited with a ‘potential to shape life chances in multiple ways’ (Robinson et al., 2015 ), e.g., academic performance, labour market competitiveness, health, civic and political participation. Steps have been successfully taken to address physical access gaps, but skills gaps are still looming (Van Deursen & Van Dijk, 2010a ). Moreover, digital inequalities have grown larger due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and they influenced the very state of health of the most vulnerable categories of population or their employability in a time when digital skills are required (Baber et al., 2022 ; Beaunoyer, Dupéré & Guitton, 2020 ).

The systematic review the researchers propose is a useful updated instrument of classification and inventory for digital literacy. Considering the latest developments in the economy and in line with current digitalisation needs, digitally literate population may assist policymakers in various fields, e.g., education, administration, healthcare system, and managers of companies and other concerned organisations that need to stay competitive and to employ competitive workforce. Therefore, it is indispensably vital to comprehend the big picture of digital literacy related research.

Literature review

Since the advent of Digital Literacy, scholars have been concerned with identifying and classifying the various (cap)abilities related to its operation. Using the most cited academic papers in this stream of research, several classifications of digital-related literacies, competencies, and skills emerged.

Digital literacies

Digital literacy, which is one of the challenges of integration of technology in academic courses (Blau, Shamir-Inbal & Avdiel, 2020 ), has been defined in the current literature as the competencies and skills required for navigating a fragmented and complex information ecosystem (Eshet, 2004 ). A ‘Digital Literacy Framework’ was designed by Eshet-Alkalai ( 2012 ), comprising six categories: (a) photo-visual thinking (understanding and using visual information); (b) real-time thinking (simultaneously processing a variety of stimuli); (c) information thinking (evaluating and combining information from multiple digital sources); (d) branching thinking (navigating in non-linear hyper-media environments); (e) reproduction thinking (creating outcomes using technological tools by designing new content or remixing existing digital content); (f) social-emotional thinking (understanding and applying cyberspace rules). According to Heitin ( 2016 ), digital literacy groups the following clusters: (a) finding and consuming digital content; (b) creating digital content; (c) communicating or sharing digital content. Hence, the literature describes the digital literacy in many ways by associating a set of various technical and non-technical elements.

Digital competencies

The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens (DigComp 2.1.), the most recent framework proposed by the European Union, which is currently under review and undergoing an updating process, contains five competency areas: (a) information and data literacy, (b) communication and collaboration, (c) digital content creation, (d) safety, and (e) problem solving (Carretero, Vuorikari & Punie, 2017 ). Digital competency had previously been described in a technical fashion by Ferrari ( 2012 ) as a set comprising information skills, communication skills, content creation skills, safety skills, and problem-solving skills, which later outlined the areas of competence in DigComp 2.1, too.

Digital skills

Ng ( 2012 ) pointed out the following three categories of digital skills: (a) technological (using technological tools); (b) cognitive (thinking critically when managing information); (c) social (communicating and socialising). A set of Internet skill was suggested by Van Deursen and Van Dijk ( 2009 , 2010b ), which contains: (a) operational skills (basic skills in using internet technology), (b) formal Internet skills (navigation and orientation skills); (c) information Internet skills (fulfilling information needs), and (d) strategic Internet skills (using the internet to reach goals). In 2014, the same authors added communication and content creation skills to the initial framework (van Dijk & van Deursen). Similarly, Helsper and Eynon ( 2013 ) put forward a set of four digital skills: technical, social, critical, and creative skills. Furthermore, van Deursen et al. ( 2015 ) built a set of items and factors to measure Internet skills: operational, information navigation, social, creative, mobile. More recent literature (vaan Laar et al., 2017 ) divides digital skills into seven core categories: technical, information management, communication, collaboration, creativity, critical thinking, and problem solving.

It is worth mentioning that the various methodologies used to classify digital literacy are overlapping or non-exhaustive, which confirms the conceptual ambiguity mentioned by van Deursen et al. ( 2015 ).

Digital thinking

Thinking skills (along with digital skills) have been acknowledged to be a significant element of digital literacy in the educational process context (Ferrari, 2012 ). In fact, critical thinking, creativity, and innovation are at the very core of DigComp. Information and Communication Technology as a support for thinking is a learning objective in any school curriculum. In the same vein, analytical thinking and interdisciplinary thinking, which help solve problems, are yet other concerns of educators in the Industry 4.0 (Ozkan-Ozen & Kazancoglu, 2021 ).

However, we have recently witnessed a shift of focus from learning how to use information and communication technologies to using it while staying safe in the cyber-environment and being aware of alternative facts. Digital thinking would encompass identifying fake news, misinformation, and echo chambers (Sulzer, 2018 ). Not least important, concern about cybersecurity has grown especially in times of political, social or economic turmoil, such as the elections or the Covid-19 crisis (Sulzer, 2018 ; Puig, Blanco-Anaya & Perez-Maceira, 2021 ).

Ultimately, this systematic review paper focuses on the following major research questions as follows:

- Research question 1: What is the yearly distribution of digital literacy related papers?

- Research question 2: What are the research methods for digital literacy related papers?

- Research question 3: What are the main themes in digital literacy related papers?

- Research question 4: What are the concentrated categories (under revealed main themes) in digital literacy related papers?

This study employed the systematic review method where the authors scrutinized the existing literature around the major research question of digital literacy. As Uman ( 2011 ) pointed, in systematic literature review, the findings of the earlier research are examined for the identification of consistent and repetitive themes. The systematic review method differs from literature review with its well managed and highly organized qualitative scrutiny processes where researchers tend to cover less materials from fewer number of databases to write their literature review (Kowalczyk & Truluck, 2013 ; Robinson & Lowe, 2015 ).

Data collection

To address major research objectives, the following five important databases are selected due to their digital literacy focused research dominance: 1. WoS/Clarivate Analytics, 2. Proquest Central; 3. Emerald Management Journals; 4. Jstor Business College Collections; 5. Scopus/Elsevier.

The search was made in the second half of June 2021, in abstract and key words written in English language. We only kept research articles and book chapters (herein referred to as papers). Our purpose was to identify a set of digital literacy areas, or an inventory of such areas and topics. To serve that purpose, systematic review was utilized with the following synonym key words for the search: ‘digital literacy’, ‘digital skills’, ‘digital competence’ and ‘digital fluency’, to find the mainstream literature dealing with the topic. These key words were unfolded as a result of the consultation with the subject matter experts (two board members from Korean Digital Literacy Association and two professors from technology studies department). Below are the four key word combinations used in the search: “Digital literacy AND systematic review”, “Digital skills AND systematic review”, “Digital competence AND systematic review”, and “Digital fluency AND systematic review”.

A sequential systematic search was made in the five databases mentioned above. Thus, from one database to another, duplicate papers were manually excluded in a cascade manner to extract only unique results and to make the research smoother to conduct. At this stage, we kept 47 papers. Further exclusion criteria were applied. Thus, only full-text items written in English were selected, and in doing so, three papers were excluded (no full text available), and one other paper was excluded because it was not written in English, but in Spanish. Therefore, we investigated a total number of 43 papers, as shown in Table Table1. 1 . “ Appendix A ” shows the list of these papers with full references.

Number of papers identified sequentially after applying all inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Database | Keyword combinations | Total number of papers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital literacy AND systematic review | Digital skills AND systematic review | Digital competence AND systematic review | Digital fluency AND systematic review | ||

| 1. WoS/Clarivate Analytics | 4 papers | 3 papers | 5 papers | – | 12 papers |

| 2. Proquest Central | 7 papers | 4 papers | – | 1 paper | 12 papers |

| 3.Emerald Management Jour | 3 papers | 1 paper | 1 paper | - | 5 papers |

| 4. Jstor Business College Collection | 9 papers | – | – | 1 paper | 10 papers |

| 5. Scopus, Elsevier | 4 papers | – | – | – | 4 papers |

| Total per keyword combination | 27 papers | 8 papers | 6 papers | 2 papers | 43 papers |

Data analysis

The 43 papers selected after the application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, respectively, were reviewed the materials independently by two researchers who were from two different countries. The researchers identified all topics pertaining to digital literacy, as they appeared in the papers. Next, a third researcher independently analysed these findings by excluded duplicates A qualitative content analysis was manually performed by calculating the frequency of major themes in all papers, where the raw data was compared and contrasted (Fraenkel et al., 2012 ). All three reviewers independently list the words and how the context in which they appeared and then the three reviewers collectively decided for how it should be categorized. Lastly, it is vital to remind that literature review of this article was written after the identification of the themes appeared as a result of our qualitative analyses. Therefore, the authors decided to shape the literature review structure based on the themes.

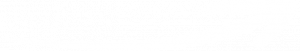

As an answer to the first research question (the yearly distribution of digital literacy related papers), Fig. 1 demonstrates the yearly distribution of digital literacy related papers. It is seen that there is an increasing trend about the digital literacy papers.

Yearly distribution of digital literacy related papers

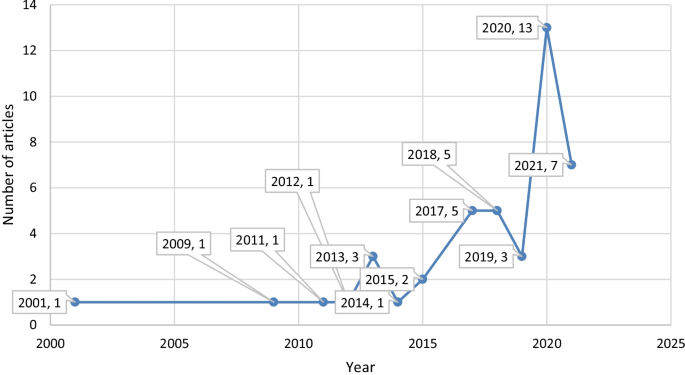

Research question number two (The research methods for digital literacy related papers) concentrates on what research methods are employed for these digital literacy related papers. As Fig. 2 shows, most of the papers were using the qualitative method. Not stated refers to book chapters.

Research methods used in the reviewed articles

When forty-three articles were analysed for the main themes as in research question number three (The main themes in digital literacy related papers), the overall findings were categorized around four major themes: (i) literacies, (ii) competencies, (iii) skills, and (iv) thinking. Under every major theme, the categories were listed and explained as in research question number four (The concentrated categories (under revealed main themes) in digital literacy related papers).

The authors utilized an overt categorization for the depiction of these major themes. For example, when the ‘creativity’ was labelled as a skill, the authors also categorized it under the ‘skills’ theme. Similarly, when ‘creativity’ was mentioned as a competency, the authors listed it under the ‘competencies’ theme. Therefore, it is possible to recognize the same finding under different major themes.

Major theme 1: literacies

Digital literacy being the major concern of this paper was observed to be blatantly mentioned in five papers out forty-three. One of these articles described digital literacy as the human proficiencies to live, learn and work in the current digital society. In addition to these five articles, two additional papers used the same term as ‘critical digital literacy’ by describing it as a person’s or a society’s accessibility and assessment level interaction with digital technologies to utilize and/or create information. Table Table2 2 summarizes the major categories under ‘Literacies’ major theme.

Categories (more than one occurrence) under 'literacies' major theme

| Category | n | Category | n | Category | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital literacy | 5 | Disciplinary literacy | 4 | Web literacy | 2 |

| Critical digital literacy | 2 | Data literacy | 3 | New literacy | 2 |

| Computer literacy | 5 | Technology literacy | 3 | Mobile literacy | 2 |

| Media literacy | 5 | Multiliteracy | 3 | Personal literacy | 2 |

| Cultural literacy | 5 | Internet literacy | 2 | Research literacy | 2 |

Computer literacy, media literacy and cultural literacy were the second most common literacy (n = 5). One of the article branches computer literacy as tool (detailing with software and hardware uses) and resource (focusing on information processing capacity of a computer) literacies. Cultural literacy was emphasized as a vital element for functioning in an intercultural team on a digital project.

Disciplinary literacy (n = 4) was referring to utilizing different computer programs (n = 2) or technical gadgets (n = 2) with a specific emphasis on required cognitive, affective and psychomotor skills to be able to work in any digital context (n = 3), serving for the using (n = 2), creating and applying (n = 2) digital literacy in real life.

Data literacy, technology literacy and multiliteracy were the third frequent categories (n = 3). The ‘multiliteracy’ was referring to the innate nature of digital technologies, which have been infused into many aspects of human lives.

Last but not least, Internet literacy, mobile literacy, web literacy, new literacy, personal literacy and research literacy were discussed in forty-three article findings. Web literacy was focusing on being able to connect with people on the web (n = 2), discover the web content (especially the navigation on a hyper-textual platform), and learn web related skills through practical web experiences. Personal literacy was highlighting digital identity management. Research literacy was not only concentrating on conducting scientific research ability but also finding available scholarship online.

Twenty-four other categories are unfolded from the results sections of forty-three articles. Table Table3 3 presents the list of these other literacies where the authors sorted the categories in an ascending alphabetical order without any other sorting criterion. Primarily, search, tagging, filtering and attention literacies were mainly underlining their roles in information processing. Furthermore, social-structural literacy was indicated as the recognition of the social circumstances and generation of information. Another information-related literacy was pointed as publishing literacy, which is the ability to disseminate information via different digital channels.

Other mentioned categories (n = 1)

| Advanced digital assessment literacy | Intermediate digital assessment literacy | Search literacy |

|---|---|---|

| Attention literacy | Library literacy | Social media literacy |

| Basic digital assessment literacy | Metaliteracy | Social-structural literacy |

| Conventional print literacy | Multimodal literacy | Tagging literacy |

| Critical literacy | Network literacy | Television literacy |

| Emerging technology literacy | News literacy | Transcultural digital literacy |

| Film literacy | Participatory literacy | Transliteracy |

| Filtering literacy | Publishing literacy |

While above listed personal literacy was referring to digital identity management, network literacy was explained as someone’s social networking ability to manage the digital relationship with other people. Additionally, participatory literacy was defined as the necessary abilities to join an online team working on online content production.

Emerging technology literacy was stipulated as an essential ability to recognize and appreciate the most recent and innovative technologies in along with smart choices related to these technologies. Additionally, the critical literacy was added as an ability to make smart judgements on the cost benefit analysis of these recent technologies.

Last of all, basic, intermediate, and advanced digital assessment literacies were specified for educational institutions that are planning to integrate various digital tools to conduct instructional assessments in their bodies.

Major theme 2: competencies

The second major theme was revealed as competencies. The authors directly categorized the findings that are specified with the word of competency. Table Table4 4 summarizes the entire category set for the competencies major theme.

Categories under 'competencies' major theme

| Category | n | Category | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| Digital competence | 14 | Cross-cultural competencies | 1 |

| Digital competence as a life skill | 5 | Digital teaching competence | 1 |

| Digital competence for work | 3 | Balancing digital usage | 1 |

| Economic engagement | 3 | Political engagement | 1 |

| Digital competence for leisure | 2 | Complex system modelling competencies | 1 |

| Digital communication | 2 | Simulation competencies | 1 |

| Intercultural competencies | 2 | Digital nativity | 1 |

The most common category was the ‘digital competence’ (n = 14) where one of the articles points to that category as ‘generic digital competence’ referring to someone’s creativity for multimedia development (video editing was emphasized). Under this broad category, the following sub-categories were associated:

- Problem solving (n = 10)

- Safety (n = 7)

- Information processing (n = 5)

- Content creation (n = 5)

- Communication (n = 2)

- Digital rights (n = 1)