How Do You Define Community and Why Is it Important?

- First Online: 30 September 2023

Cite this chapter

- Laurene Tumiel-Berhalter 18 &

- Linda Kahn 18

Part of the book series: Philosophy and Medicine ((PHME,volume 146))

144 Accesses

Researchers have an ethical responsibility to understand the communities they invite to participate in their research and that their research ultimately impacts. The commonalities that characterize a community are broad and complex, and everyone belongs to multiple, diverse, formal, and informal communities. Understanding experiences of members of different communities can help researchers fine tune their questions, assesses disparities faced by these communities, refine recruitment strategies, and assess whether proposed interventions would be equally as effective in the broader patient population. Before planning research with or in any community, it is important to explore what data has already been collected. Incorporating community voices can also help frame research to be the most inclusive and therefore more generalizable. When researchers understand a community, this can help with recruitment and improve study outcomes.

- Intersectionality

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Arditti, J. A. (2015). Situating vulnerability in research: Implications for researcher transformation and methodological innovation. The Qualitative Report, 20 (10), 1568–1575.

Google Scholar

Benoit, C., Jansson, M., Millar, A., & Phillips, R. (2005). Community-academic research on hard-to-reach populations: Benefits and challenges. Qualitative Health Research, 15 (2), 263–282.

Article Google Scholar

Bernard, H. R. (2006). Research methods in anthropology: Qualitative and quantitative approaches . Altamira press.

Boeri, M., & Shukla, R. K. (2019). Inside ethnography: Researchers reflect on the challenges of reaching hidden populations . University of California Press.

Book Google Scholar

Bradshaw, T. K. (2008). The post-place community: Contributions to the debate about the definition of community. Community Development, 39 (1), 5–16.

Center for Urban Studies in Primary. (1994). The lower west side health needs survey, 1994.

Chavis, D. M., & Lee, K. (2015). What is community anyway? . https://doi.org/10.48558/EJJ2-JJ82

Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force. (2011). Principles of community engagement . In Clinical, Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force on the Principles of Community Engagement Translational Science Awards Consortium, Agency for Toxic Substances United States, Registry Disease, Control Centers for Disease and Prevention. Dept. of Health & Human Services, National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, Clinical and Translational Science Awards (Eds.), Report.

Dankwa-Mullan, I., Rhee, K. B., Williams, K., Sanchez, I., Sy, F. S., Stinson, N., Jr., & Ruffin, J. (2010). The science of eliminating health disparities: Summary and analysis of the NIH summit recommendations. American Journal of Public Health, 100 , 12–18. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2010.191619

Easterling, B. A., & Johnson, E. I. (2015). Conducting qualitative research on parental incarceration: Personal reflections on challenges and contributions. The Qualitative Report, 20 (10), 1568–1575.

Ellard-Gray, A., Jeffrey, N. K., Choubak, M., & Crann, S. E. (2015). Finding the hidden participant solutions for recruiting hidden, hard-to-reach, and vulnerable populations. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 14 (5), 1609406915621420.

Ewing, J. A. (1984). Detecting alcoholism. The CAGE questionnaire. JAMA, 252 (14), 1905–1907. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.252.14.1905

Fremlin, J. (2015). Identifying concepts that build a sense of community . Accessed 30 Apr 2022. Media/Community Psychologist.

Green, L. W., & Mercer, S. L. (2001). Can public health researchers and agencies reconcile the push from funding bodies and the pull from communities? American Journal of Public Health, 91 (12), 1926–1929. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.91.12.1926

Joosten, Y. A., Israel, T. L., Williams, N. A., Boone, L. R., Schlundt, D. G., Mouton, C. P., Dittus, R. S., Bernard, G. R., & Wilkins, C. H. (2015). Community engagement studios: A structured approach to obtaining meaningful input from stakeholders to inform research. Academic Medicine, 90 (12), 1646–1650. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000794

Joosten, Y. A., Israel, T. L., Head, A., Vaughn, Y., Villalta Gil, V., Mouton, C., & Wilkins, C. H. (2018). Enhancing translational researchers’ ability to collaborate with community stakeholders: Lessons from the community engagement studio. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science, 2 (4), 201–207. https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2018.323

Kahn, L. S. (1992). Schooling, jobs, and cultural identity: Minority education in Quebec, Garland reference library of social science . Garland Pub.

Kahn, L. S., Vest, B. M., Kulak, J. A., Berdine, D. E., & Granfield, R. (2019). Barriers and facilitators to recovery capital among justice-involved community members. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 58 (6), 544–565. https://doi.org/10.1080/10509674.2019.1621414

Kahn, L. S., Wozniak, M., Vest, B. M., & Moore, C. (2020). “Narcan encounters:” overdose and naloxone rescue experiences among people who use opioids. Substance Abuse , 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2020.1748165

Krabbe, J., Jiao, S., Guta, A., Slemon, A., Cameron, A. A., & Bungay, V. (2021). Exploring the operationalisation and implementation of outreach in community settings with hard-to-reach and hidden populations: Protocol for a scoping review. BMJ Open, 11 (2), e039451–e039451. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039451

LaMancuso, K., Goldman, R. E., & Nothnagle, M. (2016). “Can I ask that?”: Perspectives on perinatal care after resettlement among karen refugee women, medical providers, and community-based doulas. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 18 (2), 428–435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-015-0172-6

MacQueen, K. M., McLellan, E., Metzger, D. S., Kegeles, S., Strauss, R. P., Scotti, R., Blanchard, L., & Trotter, R. T. (2001). What is community? An evidence-based definition for participatory public health. American Journal of Public Health, 91 (12), 1929–1938. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.91.12.1929

Monograph. (1990). The collection and interpretation of data from hidden populations . NIDA Research.

Moore, L. W., & Miller, M. (1999). Initiating research with doubly vulnerable populations. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 30 (5), 1034–1040. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.01205.x

Newman, S. D., Andrews, J. O., Magwood, G. S., Jenkins, C., Cox, M. J., & Williamson, D. C. (2011). Community advisory boards in community-based participatory research: A synthesis of best processes. Preventing Chronic Disease, 8 (3), A70–A70.

Quinn, S. C. (2004). Ethics in public health research. American Journal of Public Health, 94 (6), 918–922. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.94.6.918

Reilly, S. M., Wilson Crowley, M., Harold, P., Hemphill, D., & Tumiel Berhalter, L. (2018). Patient voices network: Bringing breast cancer awareness and action into underserved communities. Journal of the National Medical Association, 110 (5), 448–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnma.2017.10.008

Schuster, R. C., Rodriguez, E. M., Blosser, M., Mongo, A., Delvecchio-Hitchcock, N., Kahn, L., & Tumiel-Berhalter, L. (2019). “They were just waiting to die”: Somali Bantu and Karen experiences with cancer screening pre- and post-resettlement in Buffalo, NY. Journal of the National Medical Association, 111 (3), 234–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnma.2018.10.006

Smith, M. K. (2013). ‘Community’ in The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education . Accessed 30 Apr. https://infed.org/mobi/community/

Strauss, R. P., Sengupta, S., Quinn, S. C., Goeppinger, J., Spaulding, C., Kegeles, S. M., & Millett, G. (2001). The role of community advisory boards: Involving communities in the informed consent process. American Journal of Public Health, 91 (12), 1938–1943. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.91.12.1938

Terrell, J. A., Williams, E. M., Murekeyisoni, C. M., Watkins, R., & Tumiel-Berhalter, L. (2008). The community-driven approach to environmental exposures: How a community-based participatory research program analyzing impacts of environmental exposure on lupus led to a toxic site cleanup. Environmental Justice, 1 (2), 87–92. https://doi.org/10.1089/env.2008.0517

Tumiel-Berhalter, L., Watkins, R., & Crespo, C. J. (2005). Community-based participatory research: Defining community stakeholders. Metropolitan Universities, 16 (1), 93–106.

Wallerstein, N., & Duran, B. (2010). Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: The intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. American Journal of Public Health, 100 (S1), S40–S46. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2009.184036

Williams, E. M., Terrell, J., Anderson, J., & Tumiel-Berhalter, L. (2016). A case study of community involvement influence on policy decisions: Victories of a community-based participatory research partnership. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13 (5). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13050515

Download references

Acknowledgements

We are truly grateful to the many community partners that we have worked with over the years that have shared their stories, their insight, and their passion with us. We are honored to have been part of your lives and humbled by all you have taught us.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Family Medicine, Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Science, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, USA

Laurene Tumiel-Berhalter & Linda Kahn

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Laurene Tumiel-Berhalter .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Neiswanger Institute for Bioethics, Stritch School of Medicine, Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, IL, USA

Emily E. Anderson

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Tumiel-Berhalter, L., Kahn, L. (2023). How Do You Define Community and Why Is it Important?. In: Anderson, E.E. (eds) Ethical Issues in Community and Patient Stakeholder–Engaged Health Research. Philosophy and Medicine, vol 146. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-40379-8_7

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-40379-8_7

Published : 30 September 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-40378-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-40379-8

eBook Packages : Religion and Philosophy Philosophy and Religion (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- 日本語 ( Japanese )

- 한국어 ( Korean )

- Home /

- / “How Does the Research Benefit Society?”

“How Does the Research Benefit Society?”

Makoto Yuasa shares his views on the impact of, well, impact assessment.

- Opinion Article

- March 1, 2020

“How does your research benefit society?” “I do not quite understand the question. What does it mean?”

This famous exchange between Takaaki Kajita, a professor at the University of Tokyo and a Nobel laureate in Physics, and students at an event after his Nobel win received widespread attention online, and many researchers expressed agreement with Professor Kajita.

I remember the incident well. I have personally interviewed Professor Kajita and I asked him about it. “Basic research does not aim to benefit society in a visible way,” Professor Kajita had said. I agree with this view. It’s a widely accepted opinion that pursuing the truth is the primary intent of a researcher, and if one wants to create something that will benefit the world, one should become a researcher in the private sector.

However, given that many countries today fund universities with large amounts of public funds and invest in academic activities as well as scientific and technological development, it is not untoward to expect academia to give back to society.

There are around 160 universities in the UK, almost all of which are national universities. As they are publicly funded, the subject of whether they have a responsibility to give back to society has sparked intense debate. Universities in the UK have now come under more rigorous scrutiny, and the government has implemented policies compelling them to introduce reforms.

The UK’s impact assessment mechanism has set a precedent where the government urges universities to bring about reform in a specific manner in response to the demands of society. Impact assessment is not necessarily about compelling researchers in every field to create a social impact—a view that kept resurfacing in our interviews with impact officers. Rather, it carries the government’s intent to produce a culture shift in academia, which includes researchers being mindful of the social impact when conducting research activities with the end goal that researchers and universities are perceived as entities that contribute to society.

Changing the culture of a university is a major undertaking that has its challenges. We must applaud the UK government and university staff who undertook such daring reforms despite knowing the risks of introducing impact assessment.

I have met various researchers from numerous countries, and in every country I have visited, I got the impression that universities are considered sacred institutions. The UK government’s call to researchers to show how their research contributes to society is truly innovative. Australia and Hong Kong have followed in the UK’s footsteps and have introduced an impact assessment framework. This is likely to become a global movement. In September 2019, I conducted a seminar on impact assessment at an event in Japan; the topic stoked interest in quite a few members in the audience. Judging by the trend worldwide, it will not be surprising

If, at some point, a similar system is introduced in countries like Japan, South Korea, and China where the volume of research is the highest in Asia.

If relatively unknown research is explained in a manner that is accessible to the general public and if its social impact is understood, the public’s support for the research is likely to increase, and the research is likely to attract financial support in the form of donations and research grants. People who currently frequent a university campus for a short period may find reasons to spend more time there as the university will have a lot more to offer. Stanford University has become a launchpad for startups in the United States. In the same way, research and society may become more connected through information, and there may be more universities that become known for a unique characteristic as they attract more people outside of academia.

Impact assessment may help answer the question “How does research benefit society?” As captured in this issue, the cases that underwent an impact assessment showed impact in areas that are not easily comprehensible, such as economic impact and medical development, and impact was seen in the state of affairs, mentality, behavior, and people’s knowledge. One of the impact officers we interviewed said, “Every researcher always considers the significance of the research when formulating a research plan. That is the starting point of the impact of their research.” Another impact officer noted, “Following the introduction of impact evaluation, it became a norm for researchers to debate social impact when discussing a research plan. That in and of itself is a major impact.”

If we consider impact in a broad sense, can we not argue that all research offers some benefit, albeit in different forms? We need to wait and watch how this initiative, which started in the UK, spreads across the globe. I would like to see how Hong Kong and Australia implement their versions of impact assessment in the long run.

This article is a part of ScienceTalks Magazine issue Making Research Impact Exciting: What Universities Can Learn from REF 2014.

- Takaaki Kajita

Related post

Using experience and expertise to bring change, partnering to bring impact awareness and culture change, the first lady of research impact.

- Find Studies

For Researchers

- Learn about Research

What does it mean to do research within a community?

Some researchers do studies in a lab. Some do studies in a clinic. Some do studies in hospitals. And some do studies within a community. You might be thinking, what does it mean to do research within a community? What do researchers even mean when they say “community”? Why do they want to do research with a community? How do they learn about communities? These are all great questions!

“Community” can mean a lot of different things when it comes to research. Researchers think about communities in many different ways. A community could be people who live in the same area. It could be people who are in the same age group (like children, or older adults). It could be people who share the same identities, speak the same languages, work the same jobs, experience the same health issues, join the same social media groups, enjoy doing the same activities…or people who feel connected to each other for any of these reasons, and others!

Just like there are many different types of communities, there are a lot of reasons why researchers might be interested in doing research with communities. Some researchers want to find out about how people live their lives within their communities to help improve everyday health. Some want to figure out what the most important health issues are in a community. And others want to see if a new program might help make communities healthier.

How do researchers learn about communities?

Imagine you just moved to a new town – how would you try to learn about your new home? Would you go to some events? Try to meet new people? Talk to your neighbors? Find groups that do activities you like? Now, if you were a researcher, how would you try to learn about a community you wanted to work with? If your answers seem similar, that’s because…well…they are. When researchers want to learn about communities, the best thing they can do is (you guessed it) get out there! As a researcher tries to learn more about a community, they might go to events, volunteer with community groups, or meet with people who are interested in the same health topics as they are. They might try to find out what research projects are already going on in a community by talking to other researchers. They might try to find out what health topics are most important to community members by looking at community health reports, or maybe even by trying to organize a listening session where community members come and share their thoughts and feelings about a research topic. The more time a researcher can spend learning about a community, the better their research can be! If you see a researcher out in your community before a research project starts, they might be trying to:

- Build trust and relationships with community members

- Choose a research topic that the community is interested in

- Pick a type of study that the community wants to take part in

- Learn what results community members want to see from the research

- Figure out what might make it hard for community members to join a research study and what might make it easier

- Learn if the community wants to help plan, do, or share the research

How can researchers work with a community on a research project?

One of the most important things a researcher can learn when they want to work with communities is how much a community wants to help plan, do, and share the research. Sometimes research projects happen in communities. Research that happens in communities is called community-based research . You might also think of research as happening on communities (research should not feel like it is happening on you!). Well, research can happen with communities, too. Working with communities on a research project is called community-engaged research .

Even though community-engaged research is one type of research, these projects can all look really different. There are many ways to “engage” with communities on a research project. This is why it is so important for researchers to talk with communities about how involved they want to be in planning, doing, and sharing the research. Researchers can work with community members to…

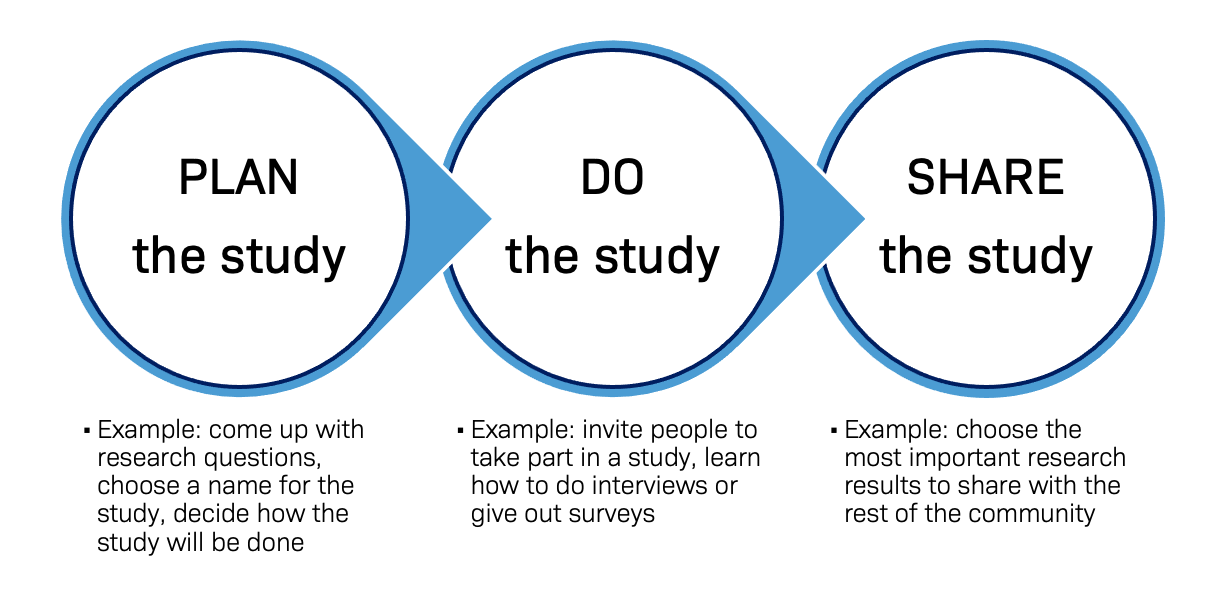

Researchers can work with communities on one part of a research project (like PLAN), or all parts of a research project (PLAN, DO, and SHARE). And sometimes researchers will work with the same communities on many different research projects! It all depends on the researcher, the study, and what the community wants.

What if researchers really want to put the community in the driver’s seat?

Sometimes, when communities are really involved with research, it is called community-based participatory research or CBPR . In community-based participatory research projects, communities aren’t just doing research with a researcher – they are leading the research! Community-based participatory research is done through a true and equal partnership of community members and a researcher or research team. The ideas, research topic, study design…pretty much everything about the research…is driven by community members. They have the power to make decisions about all parts of the study and how the research is done. Community-based participatory research studies usually try to understand big issues impacting communities (maybe something like access to healthcare or poverty within a community) and try to find solutions through policy and social change. This type of research takes a lot of time, strong relationships, and trust between community partners and researchers.

So, to wrap it all up…

There are many researchers out there who work with communities on research. Working with communities to do research takes time, trust, and effort – but it makes the research so much better for everyone!

Copyright © 2013-2022 The NC TraCS Institute, the integrated home of the NIH Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA) Program at UNC-CH. This website is made possible by CTSA Grant UL1TR002489 and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences.

Helpful Links

- My UNC Chart

- Find a Doctor

- Accessibility

- Privacy Policy

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- Virtual Tour

- Staff Directory

- En Español

You are here

Impact of nih research.

Serving Society

Societal Benefits from Research

NIH-supported research findings result in changes that benefit society and the economy.

Neighborhoods and Health

Societal-benefits-research--neighborhoods-health.jpg.

NIH-supported research shows that children who move from a high-poverty neighborhood to a low poverty neighborhood are more likely to attend college and earn over 30% more as young adults. This has prompted changes in policies at the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development and other U.S. agencies.

Image credit: Jonathan Bailey, NHGRI

- Individuals living in low-poverty neighborhoods have improved health and employment compared to individuals living in high-poverty neighborhoods.

- Moving from a high-poverty neighborhood to a low-poverty neighborhood resulted in improved well-being, mental health, and physical health, such as increased rates of employment, decreased substance use and exposure to neighborhood violence, and reduced prevalence of extreme obesity and diabetes.

- This evidence led policymakers to begin reducing systemic barriers for families to live in areas with more opportunities and lower levels of poverty.

Importance of Sleep

Societal-benefits-research--importance-sleep-cropped.jpg.

NIH-funded research shows the importance of sleep in boosting productivity at work and school. For example, a later school start time increases sleep duration and can lead to a 4.5% increase in grades. Because of this research, some states already enacted laws mandating later school start times.

Image credit: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NIH

- NIH-funded research shows that workplaces with health promotion programs have increased employee sleep duration and subsequent increased daytime performance.

- Similarly, in school settings, later school start times can increase students’ median sleep time by 34 minutes and improve school attendance, resulting in a 4.5% rise in median grades.

- A 60-minute delay in school start times also reduces car crash rates by 16.5%, as young drivers have a higher crash risk when sleep deprived.

Air Pollution and Health

Societal-benefits-research--air-pollution-health.jpg.

NIH-funded research found strong associations between exposure to air pollution and mortality. This research contributed to new Clean Air Act regulations in 1990, which resulted in air quality improvements that reached an economic value of $2 trillion by 2020 and prevented 230,000 early deaths in 2020 alone.

Image credit: Elisabeth De la Rosa, University of Texas Health Science Center, NCATS

- The net improvement in economic welfare due to new Clean Air Act regulations is projected to occur because cleaner air leads to better health and productivity for American workers, as well as savings on medical expenses for air pollution-related health problems.

- The beneficial economic effects of better health and savings on medical costs alone are projected to more than offset the expenditures for pollution control.

Dietary Guidelines

Societal-benefits-research--dietary-guidelines.jpg.

Thanks to NIH-supported research, our understanding of how dietary intake contributes to health outcomes has expanded, and a more accurate way to measure metabolism in humans is now available. This has informed dietary guidelines for all Americans, including guidance on school lunches and labels for food and menus.

Image credit: Nancy Krebs University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO

- NIH-supported research has improved our understanding of the relationships between dietary intake, human development, and risk of chronic diet-related health conditions in the U.S.

- The development of doubly labeled water (DLW)—a safe, non-invasive way to measure energy expenditure in humans—was funded by NIH and has revolutionized the measurement of metabolism in humans.

- DLW is essential for the establishment of dietary reference intakes, which are the basis for updating dietary guidelines for all Americans.

Taxes for Public Health

Societal-benefits-research--taxes-public-health.jpg.

Several U.S. cities have imposed a tax on sugar-sweetened beverages, based on research funded by NIH. In Berkeley, CA, this tax resulted in more than $9 million of revenue from 2015-2019, for public health campaigns and promotion for the city.

Image credit: Dr. Ehsan Shokri Kojori, NIAAA

- Implemented in 2015, the Berkeley tax on sugar-sweetened beverages impacted consumer spending, leading to a 10% drop in purchases of unhealthy beverages within a year.

- It also supported a public health intervention that led to improved health outcomes.

Housing and COVID-19

Societal-benefits-research--housing-covid-19.jpg.

NIH-funded research supported federal policies that prevented evictions during the COVID-19 pandemic, reducing the spread of COVID-19 and preventing excess deaths.

Image credit: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH

- Lifting eviction moratoria in the spring and summer of 2020 was associated with 433,700 excess COVID-19 cases and 10,700 excess deaths. These findings were cited in decisions by other U.S. federal agencies to extend eviction moratoria.

- CDC cited NIH research when extending the federal eviction moratorium in January 2021, and in subsequent extensions, which may have had positive downstream impacts on productivity, employment, housing, and health costs.

Nurse Workload

Societal-benefits-research--nurse-workload.jpg.

NIH research demonstrated that when hospital nurses’ workloads are increased, there are higher rates of death for patients in that hospital. This research has informed proposed or passed legislation in almost 25 states that addresses nurse staffing levels, reduces workloads, and saves lives.

Image credit: National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, NIH

- NIH-supported research found that each patient added to a nurse’s workload was associated with a 7% increase in patient mortality.

- This research has guided state-mandated nurse-to-patient ratios in California hospitals. After these guidelines went into effect, NIH researchers found that when compared to states without mandated nurse staffing levels, California nurse workloads were lower, which was associated with fewer patient deaths.

Nursing Education

Societal-benefits-research--nursing-education.jpg.

NIH-supported research showed that a more educated nurse workforce is associated with improvements in patient outcomes in hospitals. This informed recommendations from the National Academy of Medicine on nurse education, leading to an almost 10% increase in nurses with a bachelor’s degree or higher from 2011-2019.

Image credit: John Powell

- NIH-supported research showed that for every 10% increase in nurses with bachelor’s degrees, there is a related 5-7% decrease in the likelihood of death for patients in hospitals.

- This research contributed to the 2011 National Academy of Medicine (formerly the Institute of Medicine) recommendation that 80% of nurses hold a bachelor’s degree by 2020.

- Since these recommendations, the proportion of nurses in the U.S. with a bachelor’s degree or higher increased from 50% in 2011 to 59% in 2019.

- Ludwig J, et al. N Engl J Med . 2011 Oct 20;365(16):1509-19. PMID: 22010917 .

- Ludwig J, et al. Science . 2012 Sep 21;337(6101):1505-10. PMID: 22997331 .

- Fauth R, et al. Soc Sci Med . 2004 Dec;59(11):2271-84. PMID: 15450703 .

- Chetty R, et al. Am Econ Rev . 2016;106(4):855-902. PMID: 29546974 .

- Thornton RLJ, et al. Health Aff (Millwood) . 2016;35(8):1416-23. PMID: 27503966 .

- Housing Choice Voucher Mobility Demonstration -- HUD invites comments to OMB on Phase 1 Evaluation (by 11/22): https://www.aeaweb.org/forum/2181/housing-voucher-mobility-demonstration-comments-evaluation

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities: https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/what-are-housing-mobility-programs-and-why-are-they-needed

- Robbins R, et al. Am J Health Promot . 2019;33(7):1009-1019. PMID: 30957509 .

- Watson NF, et al. J Clin Sleep Med . 2017;13(4):623-625. PMID: 28416043 .

- Dockery DW, et al. N Engl J Med . 1993;329(24):1753-9. PMID: 8179653 .

- Benefits and Costs of the Clean Air Act 1990-2020, the Second Prospective Study: https://www.epa.gov/clean-air-act-overview/benefits-and-costs-clean-air-act-1990-2020-second-prospective-study

- Schoeller DA, et al. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol . 1982;53(4):955-9. PMID: 6759491 .

- Pontzer H, et al. Science . 2021;373(6556):808-812. PMID: 34385400 .

- Rhoads TW, et al. Science . 2021;373(6556):738-739. PMID: 34385381 .

- Doubly Labelled Water Method: https://doubly-labelled-water-database.iaea.org/about

- Scientific Report of the 2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee: https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/2020-advisory-committee-report

- Falbe J, et al. Am J Public Health . 2020;110(9):1429-1437. PMID: 32673112 .

- Kansagra SM, et al. Am J Public Health . 2015;105(4):e61-4. PMID: 25713971 .

- State and Local Backgrounders on Soda Taxes: https://www.urban.org/policy-centers/cross-center-initiatives/state-and-local-finance-initiative/state-and-local-backgrounders/soda-taxes

- Leifheit KM, et al. Am J Epidemiol . 2021;190(12):2503-2510. PMID: 34309643 .

- Temporary Halt in Residential Evictions to Prevent the Further Spread of COVID-19. February 2021 https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/02/03/2021-02243/temporary-halt-in-residential-evictions-to-prevent-the-further-spread-of-covid-19

- Temporary Halt in Residential Evictions to Prevent the Further Spread of COVID-19. March 2021. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/03/31/2021-06718/temporary-halt-in-residential-evictions-to-prevent-the-further-spread-of-covid-19

- Supreme Court of the Unites States. No. 21A23. 2021. https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/20pdf/21a23_ap6c.pdf

- Article: The Coming Wave of Evictions Is More Than a Housing Crisis. https://www.theatlantic.com/family/archive/2021/09/cdc-eviction-ban-housing-crisis/619960/

- Article: Nurse staffing and education linked to reduced patient mortality: https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/nurse-staffing-education-linked-reduced-patient-mortality

- Article: Linda Aiken, Whose Research Revealed the Importance of Nursing in Patient Outcomes, Receives Institute of Medicine’s 2014 Lienhard Award: https://www.nationalacademies.org/news/2014/10/linda-aiken-whose-research-revealed-the-importance-of-nursing-in-patient-outcomes-receives-institute-of-medicines-2014-lienhard-award

- Article: Nurses, and patients, have this woman to thank: https://www.uff.ufl.edu/gators/nurses-patients-woman-thank/

- Aiken LH, et al. JAMA . 2002;288(16):1987-93. PMID: 12387650 .

- Aiken LH, et al. Lancet . 2014;383(9931):1824-30. PMID: 24581683 .

- Aiken LH, et al. Health Serv Res . 2010;45(4):904-21. PMID: 20403061 .

- Learning From the California Experience: https://www.nationalnursesunited.org/learning-california-experience

- Aiken LH, et al. JAMA . 2003;290(12):1617-23. PMID: 14506121 .

- Friese CR, et al. Health Serv Res . 2008;43(4):1145-63. PMID: 18248404 .

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Initiative on the Future of Nursing, at the Institute of Medicine. The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health . 2011. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK209880/

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The Future of Nursing 2020-2030: Charting a Path to Achieve Health Equity . 2021. (page 200) https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/25982/the-future-of-nursing-2020-2030-charting-a-path-to

This page last reviewed on March 1, 2023

Connect with Us

- More Social Media from NIH

- Duke NetID Login

- 919.660.1100

- Duke Health Badge: 24-hour access

- Accounts & Access

- Databases, Journals & Books

- Request & Reserve

- Training & Consulting

- Request Articles & Books

- Renew Online

- Reserve Spaces

- Reserve a Locker

- Study & Meeting Rooms

- Course Reserves

- Digital Health Device Collection

- Pay Fines/Fees

- Recommend a Purchase

- Access From Off Campus

- Building Access

- Computers & Equipment

- Wifi Access

- My Accounts

- Mobile Apps

- Known Access Issues

- Report an Access Issue

- All Databases

- Article Databases

- Basic Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Dissertations & Theses

- Drugs, Chemicals & Toxicology

- Grants & Funding

- Interprofessional Education

- Non-Medical Databases

- Search for E-Journals

- Search for Print & E-Journals

- Search for E-Books

- Search for Print & E-Books

- E-Book Collections

- Biostatistics

- Global Health

- MBS Program

- Medical Students

- MMCi Program

- Occupational Therapy

- Path Asst Program

- Physical Therapy

- Researchers

- Community Partners

Conducting Research

- Archival & Historical Research

- Black History at Duke Health

- Data Analytics & Viz Software

- Data: Find and Share

- Evidence-Based Practice

- NIH Public Access Policy Compliance

- Publication Metrics

- Qualitative Research

- Searching Animal Alternatives

- Systematic Reviews

- Test Instruments

Using Databases

- JCR Impact Factors

- Web of Science

Finding & Accessing

- COVID-19: Core Clinical Resources

- Health Literacy

- Health Statistics & Data

- Library Orientation

Writing & Citing

- Creating Links

- Getting Published

- Reference Mgmt

- Scientific Writing

Meet a Librarian

- Request a Consultation

- Find Your Liaisons

- Register for a Class

- Request a Class

- Self-Paced Learning

Search Services

- Literature Search

- Systematic Review

- Animal Alternatives (IACUC)

- Research Impact

Citation Mgmt

- Other Software

Scholarly Communications

- About Scholarly Communications

- Publish Your Work

- Measure Your Research Impact

- Engage in Open Science

- Libraries and Publishers

- Directions & Maps

- Floor Plans

Library Updates

- Annual Snapshot

- Conference Presentations

- Contact Information

- Gifts & Donations

A Researcher's Guide to Community Engaged Research: What is CEnR?

What is cenr.

- Recommended Reading from Our Community Partners

- Glossary of Terms

- Engaging with Government

- Duke Publications

- Recorded Trainings on Community Engaged Research Practices

Introduction

This guide is an introduction to Community Engaged Research (CEnR), which is defined by the WK Kellogg Community Health Scholars Program as "begin[ning] with a research topic of importance to the community, [and] having] the aim of combining knowledge with action and achieving social change to improve health outcomes and eliminate health disparities."

Here at the Clinical and Translational Science Institute's Community Engaged Research Initiative (CERI) , Duke faculty and staff work with researchers and community members to develop relationships, improve research, and create better health outcomes in our communities, particularly for historically disadvantaged groups of people.

This guide provides resources targeted toward researchers who are looking to learn more about CEnR and implement it in their work, and includes resources about two key concepts in CEnR: cultural competence/humility and plain language .

Diagram Note: Outreach is a preparatory step that does not formally constitute community engagement.

Foundational Principles

Principles of community engagement .

(Developed by the NIH, CDC, ATSDR, and CTSA)

Be clear about the purposes of engagement and the populations you wish to engage

Become knowledgeable about the community, establish relationships, collective self-determination is the responsibility and right of the community, partnering is necessary to create change and improve health, recognize and respect the diversity of the community, mobilize community assets and develop community capacity to take action, release control of actions and be flexible to meet changing needs, collaboration requires long-term commitment.

For more information, please consult:

How-To Guides, Manuals, and Toolkits

Community involvement in research, what does community-engaged research look like.

- Community stakeholders on project steering committees and other deliberative and decision-making bodies

- Community advisory boards

- Compensation for the community's time and other contributions

- Dissemination of results back out to the community

- Takes time!

What community-engaged research is NOT:

- Focus groups or interviews

- A research methodology

- A one-size fits all approach

- Appropriate for all research

- Recruitment of minority research participants

- A relinquishing of all insight or control by researchers

Key Concept: Cultural Competence and Cultural Humility

Key concept: plain language, for more information.

The CTSI Community Engaged Research Initiative (CERI) facilitates equitable, authentic, and robust community-engaged research to improve health. Contact CERI if you are a Duke researcher who wants more information about CEnR or to access CERI's services, which include consultation services and community studios, community partnerships and coalitions, and CEnR education and training.

For more information about the resources in this guide, contact Leatrice Martin ([email protected]).

- Next: What is CEnR? >>

- Last Updated: Feb 24, 2024 4:17 PM

- URL: https://guides.mclibrary.duke.edu/CENR_researchers

- Duke Health

- Duke University

- Duke Libraries

- Medical Center Archives

- Duke Directory

- Seeley G. Mudd Building

- 10 Searle Drive

- [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Dela J Public Health

- v.8(3); 2022 Aug

The Benefits of Community Engaged Research in Creating Place-Based Responses to COVID-19

Dorothy dillard.

1 Center for Neighborhood Revitalization and Research, Delaware State University

Matthew Billie

2 Delaware State University

3 Department of Nursing, Delaware State University

Sharron Xuanren Wang

4 Department of Sociology and Criminal Justice, Delaware State University

Melissa A. Harrington

5 Delaware Institute of Science & Technology, Delaware State University

The DSU COVID-19 study aims to understand the response to and impact of COVID-19 in nine underserved communities in Delaware and to inform public health messaging. In this article, we describe our community engaged research approach and discuss the benefits of community engaged research in creating place-based health interventions designed to reduce entrenched health disparities and to respond to emerging or unforeseen health crises. We also highlight the necessity of sustained community engagement in addressing entrenched health disparities most prevalent in underserved communities and in being prepared for emerging and unforeseen health crises.

Our study is a longitudinal study comprised of three waves: initial, six months follow-up, and twelve months follow-up. Each wave consists of a structured survey administered on an iPad and a serology test. Through community engaged research techniques, a network of community partners, including trusted community facilities serving as study sites, collaborates on study implementation, data interpretation, and informing public health messaging.

The community engaged approach (CEnR) proved effective in recruiting 1,086 study participants from nine underserved communities in Delaware. The research team built a strong, trusting rapport in the communities and served as a resource for accurate information about COVID-19 and vaccinations. Community partners strengthened their research capacity. Collaboratively, researchers and community partners informed public health messaging.

The partnerships developed through CEnR allow for place-based tailored health interventions and education. Policy Implications: CEnR continues to be effective in creating mutually beneficial partnerships among researchers, community partners, and community residents. However, CEnR by nature is transactional. Without sustained partnerships with and in underserved communities, we will make little progress in impacting health disparities and will be ill-prepared to respond to emerging or unforeseen health crises. We recommend that population health strategies include sustainable research practice partnerships (RPPs) to increase their impact.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected poor people of color disproportionately. From the onset of the pandemic, racial/ethnic disparities in both cases and deaths were evident. 1 Differences have persisted as new variants of COVID-19 have emerged. What may look like small differences when aggregated within race/ethnic groups is large when cumulative mortality rate ratios are considering. Bassett and colleagues 2 found that the risk of dying from COVID-19 was greater among Blacks and Hispanics than among non-Hispanic Whites. Further analysis revealed that Blacks and Hispanics younger than 65 years dying as the result of COVID-19 were deprived of almost seven more years of life than non-Hispanic Whites younger than 65 years who died of COVID-19. These disparities by race/ethnicity are more significant than other major causes of death. Feldman and colleagues 3 analyzed CDC data for all 50 states. They concluded that if COVID-19 mortality rates had been equal across race/ethnic categories and income levels, COVID-19 deaths among race/ethnic groups would have been 71% lower.

Studies within states highlight the race/ethnic groups most impacted by COVID-19. In Massachusetts, infection and death rates were “highly correlated with race and poverty.” 4 An analysis of COVID-19 death rates among Latinx in California found that COVID-19 mortality rates were highest among the poorest. 4 Similar trends are evident in Delaware. Early in the pandemic (July 2020), the COVID-19 infection rate was 129/10,000 with Blacks three times as likely and Hispanic seven times as likely to contract COVID-19 than were non-Hispanic Whites. COVID-19 also showed a differential impact by location and race/ethnicity. In New Castle County, the overall infection rate was 95/10,000 but only 58.6 among Whites compared to 150 among Blacks and an astonishing 387.2 among Hispanics. In Kent County, the overall rate was 100/10,000, with a 53.7 positive rate among Whites yet 145.2 among Blacks and a 180.6 among Latinx. The overall COVID-19 infection rate was 2.5 times higher in Sussex County than either Kent or New Castle counties. Similarly, the race/ethnic disparities were also exacerbated with an 80.9 rate among Whites, 294.9 among Blacks, and a staggering 928/10,000 among Latinx. 5

As of July 2022, the state-wide COVID-19 death rate/10,000 persons was 24.2. The rates by county were similar in New Castle County (22.6/10,000) and Sussex County (23.6/10,000) and slightly higher in Kent County (31.5/10,000), 5 A closer look at the COVID-19 related death rates in underserved communities indicates alarming disparities. Looking at a selection of poorer communities, as indicated by Social Vulnerability Index scores of .90 or greater, the COVID-19 death rate is at least double and, in some cases, greater than four times the state rate. Although the factors affecting these disparities are many and complex, the impact of COVID-19 has mirrored that of many other health issues, disproportionately affecting poor communities of color. Research has established that zip code is a greater determinant of health than genetic code. 6 We also know that access to healthcare and other services is more difficult for the poor, particularly for poor minorities. 7 These realities are exacerbated by a justified mistrust of both science 8 and medicine 9 among Black and Brown Americans. Given these realities, understanding the impact of and response to COVID-19 in underserved communities requires a place specific approach.

Study Design

In response to the early signs of COVID-19’s disproportionate impact on lower income communities with a large proportion of Black and Brown residents, we initiated a longitudinal study to examine the impact of and response to COVID-19 in nine underserved communities in Delaware. We have completed the first wave of surveying and serology testing, successfully recruiting 1,085 respondents and building a strong network of community partners. Our experience highlights the role of community engaged research in addressing COVID-19 in underserved communities. More importantly, it underscores the necessity of maintaining partnerships with and in underserved communities if progress is to be made on reducing health disparities and if we are to be prepared for emerging or unforeseen health issues.

Our study, “Social and Behavioral Implications for COVID-19 Testing in Delaware’s Underrepresented Communities,” aims to understand the impact of and response to COVID-19 and to share what we learn with state and community partners to improve and tailor COVID-19 public health messaging. We selected nine underserved communities based on the Community Health Index (CHI), coupled with incidence of COVID-19 and COVID-19 testing rates. The CHI is a score calculated for each census tract by the Delaware Division of Public Health (DPH) based on health indicators. The CHI score ranges from 12.3 (better) to 208.6 (worse). DPH created a color-coded scoring mechanism to identify and track COVID-19 testing and positive rates by census tracts. Table 1 provides an overview of our study communities. All nine communities have high CHI scores, indicating higher rates of health issues among residents, and were ranked as medium or high priority by DPH’s COVID-19 response.

Our study design is longitudinal with surveying and serology testing conducted at initial enrollment (Wave 1), six (6) months after enrollment (Wave 2), and 12 months after enrollment (Wave 3). Data collection includes the administration of a survey and a serology test. The Wave 1 survey, adapted from the COVID-19 Community Response Survey developed by Johns Hopkins University, includes questions about demographics, socioeconomic characteristics, COVID-19-related beliefs and practices, general health, and COVID-19 testing and vaccination. We revised the survey for Waves 2 and 3 to include additional vaccination questions. The serology test provides data on exposure to the COVID-19 infection, allowing for an objective measure of exposure. The study team is comprised of a project manager, DSU graduate nursing students, and DSU undergraduate students. The study team reflects the community in terms of race and ethnicity, including several DSU bilingual students.

The study team employs COVID-19 safety protocol, including wearing masks, using partitions to separate participants while completing the survey and during serology testing and results discussion, and wiping down surfaces and iPads. Prior to entering the study site, the nurse screens potential participants for COVID-19 using CDC recommended screening procedures. If the screen indicates exposure to COVID-19 or COVID-19 symptoms, the potential participant is encouraged to get tested, provided with testing information, and asked to return to the study site when COVID-19 negative or when symptoms have resolved.

Using a community engaged approach, we leveraged existing partnerships with access to trusted service providers located in our study communities. Community-engaged research (CEnR) recognizes the historical mistreatment of marginalized groups in research and places the community first by involving research participants in all aspects of the research process (CEnR). 10 It is an essential approach to understanding and addressing health issues because it focuses on research participants living in close proximity and sharing similar situational characteristics affecting their health. As such, CEnR is responsive to the centrality of place in addressing health disparities.

CEnR is an essential component of translational research, primarily because it aims to include the subjects of research as participants making findings directly relevant and accessible to the target population. Much attention has been given to the importance of CEnR, including the DJPH September 2018 issue. However, less attention is paid to the difficulty of conducting community engaged research in the academic environment. CEnR emphasizes building capacity, improving trust, and translating knowledge to action. To build the trusting mutually beneficial relationship between research and community takes time and effort that is rarely funded, making it low priority and often discouraged. But without these relationships academic researchers are left flat footed when the race to secure funding starts because the time between funding announcement and proposal submission does not allow for building relationships with community partners. CEnR also emphasizes the involvement of community members in all stages of research, from framing the issue, creating the data collection instruments, and designing the study. This too is frequently not feasible in the timeframe for responding to research funding opportunities. Another set of issues emerges from the proposal review process. Proposal review panels frequently expect validated instruments or surveys in the public domain, prohibiting community input on the information collected. Validated instruments also lean toward generic and frequently academic language that excludes culturally and geographically relevant phrasing, increasing the likelihood of respondent misunderstanding. Review panels tend to score quantitative studies with large samples and sophisticated data analysis plans highest, forcing researchers to prioritize reviewer preferences over community needs. The publish or perish culture of academia coupled with its growing expectation of contributing to the institution’s research portfolio by securing external funding exacerbate the barriers to CEnR.

We faced these common challenges as we responded to the NIH call for rapid response proposals to COVID-19. Although we were not able to fully engage our study communities during proposal development, we did rely on our existing community partners, Sussex County Health Coalition (SCHC) and the Wilmington Community Advisory Council (WCAC), to help us shape our recruitment and participant engagement protocol and to connecting us to trusted facilities. Through their extended networks, SCHC and WCAC identified ten trusted facilities willing to serve as study sites.

Our proposal included SCHC as our community partner in Kent and Sussex Counties. WCAC was not able to take on the community partner role but remained a key partner in our research and dissemination efforts. Another community partner, the Wilmington HOPE Commission (WHC) agreed to serve as our community partner in New Castle County. SCHC and WHC are different in that SCHC is a coalition with an extensive network of partners and WHC is a service agency in direct contact with potential study participants. Both types of organizations benefit recruitment. SCHC relies on it network of service providers to advertise the study and recruit participants; whereas, WHC uses word of mouth and its clients to recruit. It is important to note that we compensate our community partners. Monetary compensation creates equity with community partners.

We have grown our network to include additional host sites, allowing the study team to work directly in several isolated rural communities. We have also partnered with two libraries, the Seaford and Harrington public libraries. Establishing study sites at these libraries allowed us access to potential study participants from our communities of interest. We extended our network to include two churches, both located directly in study communities and providing community outreach. Our community partners also identified individuals from the community who we compensated to translate the recruitment materials, consent forms, and survey into Spanish and Haitian Creole. Several community residents were hired to assist at the study sites, serving as translators and being a familiar face at the study site.

SCHC and WHC have primary responsibility for recruiting back and scheduling participants for Wave 2 and Wave 3, six and twelve months after initial enrollment. Our community partners lead the development of recruit-back processes, tailoring them for the study communities. Several techniques were employed, including phone calls and text messages. Participants were contacted for two weeks before and after their return date. With each contact, they are provided a study site schedule, allowing them to complete Wave 2 and Wave 3 at the most convenient site.

Our community partners also provide a platform to disseminate information about the study and findings. One of our primary study aims was to inform public health messaging by sharing findings continuously with our community and state partners. We have been fortunate to expand our network to include the Division of Public Health, university based cooperative extension programs, hospitals and COVID-19 response coalitions. We present findings as they become available, shortening the gap between research and practice. We work directly with DPH and two university cooperative extension teams informing tailored public health messaging. We also respond to partners’ request for information, allowing the community to identify the topics of concern and interest.

The Benefits of Community Engaged Research

Both researchers and community partners benefit from community engaged research approaches. By leveraging the expertise of our community partners, we successfully recruited 1,086 study participants, 91% of our 1,200 participant target, in eight months during COVID-19 resurgences causing site closures. The differences in our recruitment rates by county underscore the importance of our partners. Our strongest partnerships are in New Castle County and in Sussex County. The recruitment rates in both those counties (103% in each county) were over twice the recruitment rate in Kent County (48%) where our community partners took longer to establish and were fewer than in the other two counties.

The study team’s consistent presence in the underserved communities increases trust of researchers. Building trust requires commitment and patience. As an example, the study team was at one remote community site for three weeks with no community participation despite extensive recruitment efforts. The third week a trusted member of the community came to the site to inquire about the activities. She participated in the study and the next week eight additional community members enrolled. The composition of the study team which reflects the residents of many of the study communities has also been key to building trust within the community. Participants have tracked their return dates and returned without reminders. Participants come by the study sites to confirm return dates and volunteer for future studies. Our study bolsters the participants’ confidence in COVID-19 initiatives such as masking, vaccination, and routine testing. We serve as a liaison to local health care resources and combat COVID-19 misinformation. The serology testing component of the study aids participants in gauging previous contact/infection and making decisions about vaccination.

Our CEnR approach has strengthened our community partners’ research muscle. Presentations educate our partners on community engaged research design and implementation, they provide a platform for community partners to ask questions and provide insight and more contextual, community-specific understanding of our research findings. They encourage community partners to ask questions, guiding our analyses and producing more community relevant findings. For example, our early analyses highlighted vaccine hesitancy. 11 When we presented these early findings, community partners were interested in the reasons why participants were not vaccinated, more specific race/ethnic group analyses, and COVID-19 information sources used by study participants. We updated our vaccine hesitancy analyses addressing these community driven requests. We are currently engaging in small group discussions about the findings so we, research and community in collaboration, can focus on the implications of the findings for specific communities. This example also underscores how CEnR strengthens translational research. Our COVID-19 study includes an explicit aim to inform public health messaging, translating science to practice in real time. Frequent communication with community partners, provides the outreach workers critical information to better educate and advocate for their constituents.

Our collaboration with study site host agencies has allowed us to respond to two new requests for proposals, both employing CEnR. During proposal development, we solicited input from an expanded network. The community partnerships we developed while implementing the COVID-19 study allowed us to engage two new community serving partners in these proposals. Both new partners are located in communities of interest and directly serve residents in these communities, strengthening our community focus as well as strengthening community research capacity.

As with most CEnR, significant effort has been extended to implement this study. And, we have once again been reminded that community engagement of any type requires time and patience and for it to be mutually beneficial it must put community first. We also learned that CEnR, as a form of community engagement, is worth the effort for researchers, community partners, and community residents. However, CEnR by nature is transactional. It exists as long as the study is funded, creating a new challenge: maintaining and strengthening community partnerships that are necessary to address health disparities in a tailored place/community specific approach. Without sustained partnerships with and in underserved communities, we will make little progress in impacting health disparities and will be ill-prepared to respond to emerging or unforeseen health crises.

One effective mechanism to maintain and strengthen community partnerships is to build on the foundation established by CEnR by supporting sustainable research practice partnerships (RPPs). Educational research has relied heavily on RPPs to improve teaching and learning. 12 RPPs are designed explicitly to address persistent or entrenched problems by creating equitable partnerships between researchers and practitioners. Through these mutually respectful partnerships, researchers understand practice context (or community) making the research more relevant and practitioners understand and participate in research increasing data informed interventions. In RPPs, researchers support practice partners in achieving their service goals. They are less about peer reviewed publications and more focused on providing practice partners data designed for decision-making. Practice oriented analysis makes RPPs key in translational research. Research partners’ commitment to rigorous, scientifically sound research methodology ensures findings are valid and reliable and increases the likelihood findings are generalizable to similar contexts and populations. The methodological sound research strategy enables RPPs to inform academic and practice disciplines. RPPs offer a transformational partnership between researchers and practitioners, significantly shortening the science to practice translational gap.

Research practice partnerships (RPPs) are a natural outcome of CEnR and offer a sustainable strategy to address entrenched health disparities and to be positioned to respond to emerging and unforeseen health crises. The reality is that some health crises are unpreventable and, in some cases, unpredictable. However, we can be better prepared to respond to the unpredictable health crises and more effective in addressing the entrenched health disparities by responding to what we know and building on what we have.

We know that zip codes are a stronger determinant of health than genetic codes, underscoring the centrality of location in addressing health disparities and emphasizing the need to put location and, thus, community, first in all public health responses. We also know that mistrust of medicine and research continues to inhibit response to health disparities and health emergencies. A sustained partnership between researchers, community serving organizations and community residents through RPPs is necessary to create trust as well as produce and implement community defined responses to health disparities. Community engaged research techniques have proven effective as a research strategy and offer a starting point to create sustainable research practice partnerships that can advance science and improve the health conditions in underserved communities. Including RPPs in all population health strategies would increase the likelihood of decreasing health disparities and increase our preparedness to address emerging and unforeseen health crises.

Acknowledgements

This study could not have been implemented without the continuous assistance and support of our community partners and host sites. We are grateful for their collaboration. We also thank our students and nurses who have created a community friendly COVID-19 safe research environment.

Disclosures

This project is supported by the National Institute of Health (Grant number: 3 P20 GM103653-09S1).

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Before planning research with or in any community, it is important to explore what data has already been collected. Incorporating community voices can also help frame research to be the most inclusive and therefore more generalizable. When researchers understand a community, this can help with recruitment and improve study outcomes. Keywords ...

Impact assessment may help answer the question “How does research benefit society?”. As captured in this issue, the cases that underwent an impact assessment showed impact in areas that are not easily comprehensible, such as economic impact and medical development, and impact was seen in the state of affairs, mentality, behavior, and people ...

Our results provide insights critical to understanding how CEnR approaches function within an emerging aLHS and ways to further build and nurture community-academic partnerships and inform research and institutional priorities to increase health equity, reduce health disparities, and improve community and population health.

We also have a program for seminarians, which might not seem connected to science. We have found that establishing relationships helps to create trust with the religious community. That’s critical to have when disagreement occurs as a level of trust already exists to build upon. You have to build that trust beforehand, not when you need it.

One of the most important things a researcher can learn when they want to work with communities is how much a community wants to help plan, do, and share the research. Sometimes research projects happen in communities. Research that happens in communities is called community-based research.

societal-benefits-research--importance-sleep-cropped.jpg. NIH-funded research shows the importance of sleep in boosting productivity at work and school. For example, a later school start time increases sleep duration and can lead to a 4.5% increase in grades. Because of this research, some states already enacted laws mandating later school ...

Our approach to health research relies on the guidance and advice of our Community Advisory Council, made up of community faith leaders, patients, healthcare providers, and study participants. From this collaboration, we are working together to foster trustworthiness in research and increase broad and diverse representation in research ...

The failure of traditional research to address ongoing and complex health disparities has led to an increased emphasis on Community Engaged Research (CEnR) as a vital tool for finding more effective methods to improve health outcomes. 1,2 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines community engagement as “the process of working collaboratively with groups of people affiliated by ...

Both researchers and community partners benefit from community engaged research approaches. By leveraging the expertise of our community partners, we successfully recruited 1,086 study participants, 91% of our 1,200 participant target, in eight months during COVID-19 resurgences causing site closures.