- University of Pennsylvania

- School of Arts and Sciences

- Penn Calendar

Search form

On Thesis Statements

The thesis statement.

This is not an exhaustive list of bad thesis statements, but here're five kinds of problems I've seen most often. Notice that the last two, #4 and #5, are not necessarily incorrect or illegitimate thesis statements, but, rather, inappropriate for the purposes of this course. They may be useful forms for papers on different topics in other courses.

A thesis takes a position on an issue. It is different from a topic sentence in that a thesis statement is not neutral. It announces, in addition to the topic, the argument you want to make or the point you want to prove. This is your own opinion that you intend to back up. This is your reason and motivation for writing.

Bad Thesis 1

Bad Thesis 2 : This paper will consider the advantages and disadvantages of certain restrictions on free speech.

Better Thesis 1 : Stanley Fish's argument that free speech exists more as a political prize than as a legal reality ignores the fact that even as a political prize it still serves the social end of creating a general cultural atmosphere of tolerance that may ultimately promote free speech in our nation just as effectively as any binding law.

Better Thesis 2 : Even though there may be considerable advantages to restricting hate speech, the possibility of chilling open dialogue on crucial racial issues is too great and too high a price to pay.

A thesis should be as specific as possible, and it should be tailored to reflect the scope of the paper. It is not possible, for instance, to write about the history of English literature in a 5 page paper. In addition to choosing simply a smaller topic, strategies to narrow a thesis include specifying a method or perspective or delineating certain limits.

Bad Thesis 2 : The government has the right to limit free speech.

Better Thesis 1 : There should be no restrictions on the 1st amendment if those restrictions are intended merely to protect individuals from unspecified or otherwise unquantifiable or unverifiable "emotional distress."

Better Thesis 2 : The government has the right to limit free speech in cases of overtly racist or sexist language because our failure to address such abuses would effectively suggest that our society condones such ignorant and hateful views.

A thesis must be arguable. And in order for it to be arguable, it must present a view that someone might reasonably contest. Sometimes a thesis ultimately says, "we should be good," or "bad things are bad." Such thesis statements are tautological or so universally accepted that there is no need to prove the point.

Bad Thesis 2 : There are always alternatives to using racist speech.

Better Thesis 1 : If we can accept that emotional injuries can be just as painful as physical ones we should limit speech that may hurt people's feelings in ways similar to the way we limit speech that may lead directly to bodily harm.

Better Thesis 2 : The "fighting words" exception to free speech is not legitimate because it wrongly considers speech as an action.

A good argumentative thesis provides not only a position on an issue, but also suggests the structure of the paper. The thesis should allow the reader to imagine and anticipate the flow of the paper, in which a sequence of points logically prove the essay's main assertion. A list essay provides no such structure, so that different points and paragraphs appear arbitrary with no logical connection to one another.

Bad Thesis 2 : None of the arguments in favor of regulating pornography are persuasive.

Better Thesis 1 : Among the many reasons we need to limit hate speech the most compelling ones all refer to our history of discrimination and prejudice, and it is, ultimately, for the purpose of trying to repair our troubled racial society that we need hate speech legislation.

Better Thesis 2 : None of the arguments in favor of regulating pornography are persuasive because they all base their points on the unverifiable and questionable assumption that the producers of pornography necessarily harbor ill will specifically to women.

In an other course this would not be at all unacceptable, and, in fact, possibly even desirable. But in this kind of course, a thesis statement that makes a factual claim that can be verified only with scientific, sociological, psychological or other kind of experimental evidence is not appropriate. You need to construct a thesis that you are prepared to prove using the tools you have available, without having to consult the world's leading expert on the issue to provide you with a definitive judgment.

Bad Thesis 2 : Hate speech can cause emotional pain and suffering in victims just as intense as physical battery.

Better Thesis 1 : Whether or not the cultural concept of free speech bears any relation to the reality of 1st amendment legislation and jurisprudence, its continuing social function as a promoter of tolerance and intellectual exchange trumps the call for politicization (according to Fish's agenda) of the term.

Better Thesis 2 : The various arguments against the regulation of hate speech depend on the unspoken and unexamined assumption that emotional pain is either trivial.

Thirty years of research into hate speech: topics of interest and their evolution

- Open access

- Published: 30 October 2020

- Volume 126 , pages 157–179, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Alice Tontodimamma 1 ,

- Eugenia Nissi 2 ,

- Annalina Sarra 3 &

- Lara Fontanella 3

23k Accesses

49 Citations

8 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The exponential growth of social media has brought with it an increasing propagation of hate speech and hate based propaganda. Hate speech is commonly defined as any communication that disparages a person or a group on the basis of some characteristics such as race, colour, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, nationality, religion. Online hate diffusion has now developed into a serious problem and this has led to a number of international initiatives being proposed, aimed at qualifying the problem and developing effective counter-measures. The aim of this paper is to analyse the knowledge structure of hate speech literature and the evolution of related topics. We apply co-word analysis methods to identify different topics treated in the field. The analysed database was downloaded from Scopus, focusing on a number of publications during the last thirty years. Topic and network analyses of literature showed that the main research topics can be divided into three areas: “general debate hate speech versus freedom of expression”,“hate-speech automatic detection and classification by machine-learning strategies”, and “gendered hate speech and cyberbullying”. The understanding of how research fronts interact led to stress the relevance of machine learning approaches to correctly assess hatred forms of online speech.

Similar content being viewed by others

Fake news, disinformation and misinformation in social media: a review

Sexist Slurs: Reinforcing Feminine Stereotypes Online

More human than human: measuring ChatGPT political bias

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In recent years, the ways in which people receive news, and communicate with one another, have been revolutionised by the Internet, and especially by social networks. It is a natural activity, in societies where freedom of speech is recognised, for people to express their opinions. From an era in which individuals communicated their ideas, usually orally and only to small numbers of other people, we have moved on to an era in which individuals can make free use of a variety of diffusion channels in order to communicate, instantaneously, with people who are a long distance away; in addition, more and more people make use of online platforms not only to interact with each other, but also to share news. The detachment created by being enabled to write, without any obligation to reveal oneself directly, means that this new medium of virtual communication allows people to feel greater freedom in the way they express themselves. Unfortunately, though, there is also a dark side to this system. Social media have become a fertile ground for heated discussions which frequently result in the use of insulting and offensive language. The creation and dissemination of hateful speech are now pervading the online platforms. As a result, countries are recognising hate speech as a serious problem, and this has led to a number of International and European initiatives being proposed, aimed at qualifying the problem and developing effective counter-measures.

A first issue, for the identification of a content as hateful, is that there is no universally accepted definition of hate speech, mainly because of the vague and subjective determinations as to whether speech is “offensive” or conveys “hate” (Strossen 2016 ). A comprehensive overview of different definitions can be found in Sellars ( 2016 ) who derives several related concepts that appear throughout academic and legal attempts to define hate speech as well as in attempts of online platforms. The identified common traits refer to: the targeting of a group, or an individual as a member of a group; the presence of a content that expresses hatred, causes a harm, incites bad actions beyond the speech itself, and has no redeeming purpose; the intention of harm or bad activity; the public nature of the speech; finally, a context that makes violent response possible. Sellars ( 2016 ) stresses, however, how the identified traits do not form a single definition, but could be used to help improve the confidence that the speech in question is worthy of identification as hate speech.

In addition to the ambiguity in the definition, hate speech creates a conflict between some people’s speech rights, and other people’s right to be free from verbal abuse (Greene and Simpson 2017 ). The complex balancing between freedom of expression and the defence of human dignity has received significant attention from legal scholars and philosophers and, according to Sellars ( 2016 ), the different approaches to define hate speech can be linked to academics’ particular motivations: “Some do not overtly call for legal sanction for such speech and seek merely to understand the phenomenon; some do seek to make the speech illegal, and are trying to guide legislators and courts to effective statutory language; some are in between.” Advocates of the free speech rights invoke the principle of viewpoint neutrality or content neutrality, which prohibits bans on the expression of viewpoints based on their substantive message (Brettschneider 2013 ). This protection extends even to speech that expresses ideas that most people would find distasteful, offensive, disagreeable, or discomforting, and thus extends even to hate speech (Beausoleil 2019 ). According to Strossen ( 2016 , 2018 ) hate speech laws not only violate the cardinal viewpoint neutrality, but also the emergency principles, by permitting government to suppress speech solely because its message is disfavoured, disturbing, or feared to be dangerous, by government officials or community members, and not because it directly causes imminent serious harm. On the other hand, Cohen-Almagor ( 2016 , 2019 ) insists that it is necessary to “take the evils of hate speech seriously” and that “certain kinds of speech are beyond tolerance.” The author criticizes the viewpoint neutrality concept arguing that a balance needs to be struck between competing social interests because freedom of expression is important as is the protection of vulnerable minorities: “people must enjoy absolute freedom to advocate and debate ideas, but this is so long as they refrain from abusing this freedom to attack the rights of others or their status in society as human beings and equal members of the community.” An alternative remedy to censoring hate speech could be to add more speech, as suggested by the UNESCO study titled “Countering On-line Hate Speech” (Gagliardone et al. 2015) which argues that counter-speech is usually preferable to the suppression of hate speech.

The rising visibility of hate speech on online social platform has resulted in a continuously growing rate of published research into different areas of hate speech. The increasing number of studies on this subject is beneficial to scholars and practitioners, but it also brings about challenges in terms of understanding the key research streams in the area. Previous surveys highlighted the state of the art and the evolution of research on hate speech (Schmidt and Wiegand 2017 ; Fortuna and Nunes 2018 ; MacAvaney et al. 2019 ; Waqas et al. 2019 ). The survey of Schmidt and Wiegand ( 2017 ) describes the key areas that have been explored to automatically recognize hateful utterances using neural language processing. Eight categories of features used in hate speech detection, including simple surface, word generalization, sentiment analysis, lexical resources and linguistic characteristics, knowledge-based features, meta-information, and multimodal information, have been highlighted. In addition, Schmidt and Wiegand ( 2017 ) stress how a comparability of different features and methods requires a benchmark data set. Fortuna and Nunes ( 2018 ) carried out an in-depth survey aimed at providing a systematic overview of studies in the field. In this survey, the authors firstly pay attention to the motivations for studying hate speech and then they conveniently distinguish theoretical and practical aspects. Specifically, they list some of the main rules for hate speech identification and investigate the methods and algorithms adopted in literature for automatic hate speech detection. Also, practical resources, such as datasets and other projects, have been reviewed. MacAvaney et al. ( 2019 ) discussed the challenges faced by online automatic approaches for hate speech detection in text, including competing definitions, dataset availability and construction. A throughout bibliographic and visualization analysis of the scientific literature related to online hate speech was conducted Waqas et al. ( 2019 ). Drawing on Web of Science (WOS) core database, their study concentrated on the mapping of general research indices, prevalent themes of research, research hotspots and influential stakeholders, such as organizations and contributing regions. Along with the most popular bibliometric measures, such as total number of papers, to measure productivity, and total citations, to assess the relevance of a country, institution, or author, the above mentioned research uses mapping knowledge tools to draw the structure and networks of authors, journals, universities and countries. Not surprisingly, the results of this bibliometric analysis show a remarkable increase in publication and citation trend after year 2005, when social media platforms have grown in terms of influence and user adoption, and the Internet has become a central arena for public and private discourse. Furthermore, it has emerged that most of the publications originate from the discipline of psychology and psychiatry, with recurring themes of cyberbullying, psychiatric morbidity, and psychological profiling of aggressors and victims. As noted by the authors, the high representation of psychology-related contributions is mainly due to the choice of WOS core database, which excludes relevant research fields from the analysis, being its coverage geared towards health and social science disciplines rather than engineering or computer ones.

Based on these previous studies, and especially on that of Waqas et al. ( 2019 ), our research intends to enlarge the mapping of global literature output regarding online hate speech over the last thirty years, by relying on bibliographic data extracted from Scopus database and using different methodological approaches. In order to identify how online hate scientific literature is evolving and understand what are the main research areas and fronts and how they interact over time, we used bibliometric measures, mapping knowledge tools and topic modelling. All the above methods are traditionally employed in bibliometrics analysis and share the idea of using a great amount of bibliographic data to let emerge, in an unsupervised way, the underlying knowledge base. In particular, topic analysis, based on the Latent Dirichlet Allocation method (LDA; Blei et al. 2003 ) is gaining popularity among scholars in diverse fields (Alghamdi and Alfalqi 2015 ). A topic model leads to two key outputs: a list of topics (i.e. groups of words that frequently occur together) and a lists of documents that are strongly associated with each topic (McPhee et al. 2017 ). Accordingly, this approach is useful for finding interpretable topics with semantic meaning and for assigning these topics to the literature documents, offering in such way a probabilistic quantification of relevance both for the identification of topics and for the classification of documents.

Our study exploits the main strengths of each method in drawing a synthetic representation of the research trends on online hate and adds value to previous quoted works, by taking advantage of topic modelling to retrieve latent driven themes. As highlighted in Suominen and Toivanen ( 2016 ), the key novelty of topic modelling, in classifying scientific knowledge, is that it virtually eliminates the need to fit new-to-the-world knowledge into known-to-the-world definitions.

The remainder of this work is structured as follows. Section “Materials and methods” describes the data source and the methods used. Section “Results” presents the bibliometric results, focusing on the yearly quantitative distribution of publications and on the latent topics retrieved through LDA. This section provides useful insights into the temporal evolution of the topics, their interactions and the research activity in the identified latent themes. A conclusion and future perspectives are given in “Conclusion” section. Finally, we report additional information on the bibliographic data set and the topic analysis results, in the online Supplementary Material.

Materials and methods

Bibliographic dataset.

For the analysis, we use a bibliometric dataset, covering the period 1992–2019, retrieved from Scopus database. This bibliographic database was selected because it is one of the most suitable source of references for scientific peer-reviewed publications.

In the same vein of Waqas et al. ( 2019 ), we focus on online hate and, for our search, we built a query that, in addition to the exact phrase “hate speech”, combines terms related to offensive or denigratory language (“hatred”, “abusive language, “abusive discourse”, “abusive speech”, “offensive language”, “offensive discourse”, “offensive speech”, “denigratory language”, “denigratory discourse”, “denigratory speech”) with words linked to the online nature (“online”,“social media”, “web”, “virtual”, “cyber”, “Orkut”, “Twitter”, “Facebook”, “Reddit”, “Instagram”, “Snapchat”, “Youtube”, “Whatsapp”, “Wechat”, “QQ”, “Tumblr”, “Linkedin”, “Pinterest”).

We have not considered specific terms linked to cyberbullying because, although if this phenomenon overlaps partially with hate speech, it encompasses a broader field. The exact query can be found in the Supplementary Material.

The bibliographic data was extracted by applying the query to the contents of title, abstract and keywords. The data for each resulting publication was manually exported on December 15, 2019.

All types of publications were included in the search, and 1614 documents related to hate speech, published in 995 different sources, were identified. This high number indicates a wide variety of research themes, and the multidisciplinary character of the subject which involves a plurality of disciplines. In particular, the top publication fields include Social Sciences, Computer Science, Arts and Humanities and Psychology. Looking at the document type, the majority is article, conference paper and book chapter.

Information about document distribution by research field is given in the Supplementary Material, along with the document distribution by source and the ranking of the most productive countries and authors.

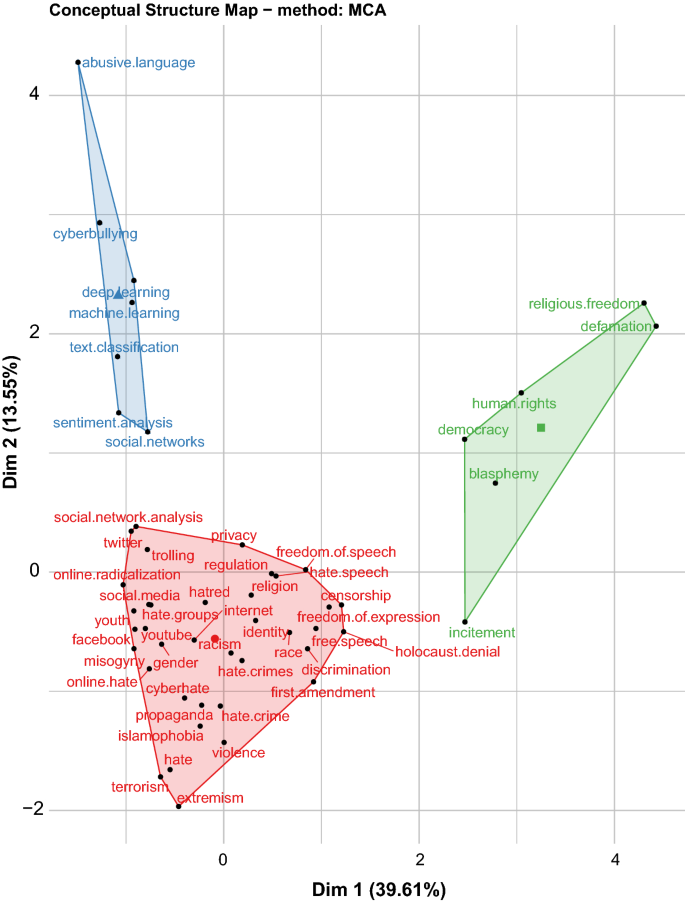

Conceptual structure map

To investigate the structure of research on hate speech, we firstly consider an exploratory analysis of the keywords selected by the authors. The analysis was carried out through the R package Bibliometrix (Aria and Cuccurullo 2017 ), which allows to perform multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) (Greenacre and Blasius 2006 ) and hierarchical clustering to draw a conceptual structure map of the field. Specifically, MCA allows to obtain a low-dimensional Euclidean representation of the original data matrix, by performing a homogeneity analysis of the “documents by keywords” indicator matrix, built by considering a dummy variable for each keyword. The words are plotted onto a two-dimensional map where closer words are more similar in distribution across the documents. In addition, the implementation of a hierarchical clustering procedure on this reduced space leads to identify clusters of documents that are characterised by common keywords.

Topic analysis

To gain a deeper understanding of the topics discussed in the published research on hate speech, we have applied Latent Dirichet Allocation, which is an automatic topic mining technique that enables to uncover hidden thematic subjects in document collections by revealing recurring clusters of co-occurring words. The two foundational probabilistic topic models are the Probabilistic Latent Semantic Analysis (pLSA, Hofmann 1999 ) and the Latent Dirichlet Allocation (Blei et al. 2003 ). The pLSA is a probabilistic variant of the Latent Semantic Analysis introduced by Deerwester et al. ( 1990 ) to capture the semantic information embedded in large textual corpora without human supervision. In the pLSA approach, each word in a document is modelled as a sample from a mixture model, where the mixture components are multinomial random variables that can be viewed as representations of topics. The pLSA model allows multiple topics in each document, and the possible topic proportions are learned from the document collection. Blei et al. ( 2003 ) introduced the LDA which presents a higher modelling flexibility over pLSA by assuming fully complete probabilistic generative model where each document is represented as a random mixture over latent topics and each topic is characterized by a distribution over words. LDA mitigates some shortcomings of the earlier topic models. Specifically, it has the advantage to improve the way of mixture models of capturing the exchangeability of both words and documents. LDA assumes a probabilistic generative model where each document is described by a distribution of topics and each topic is described by a distribution of words. The set of candidate topics are the same for all documents and each document may contain words from multiple different topics. The generative two-stage process of each document in the corpus can be described as follows (Blei 2012 ). In the first step a distribution over topics is randomly chosen; in the second step for each word in the document a topic is randomly chosen from the distribution over topics and a word is randomly chosen from the corresponding distribution over the vocabulary. Following Blei ( 2012 ), it it is possible to describe LDA more formally. Let assume that we have a corpus defined as a collection of D documents where each document is a sequence of N words, \(w_d=(w_{d,1},w_{d,2},\dots ,w_{d,N})\) , and each word is an item from a vocabulary indexed by \(\{1,\dots ,V\}\) . Furthermore, we assume that there are K latent topics, \(\beta _{1:K}\) , defined as distribution over the vocabulary. The generative process for LDA corresponds to the following joint distribution of the hidden and observed variables

The topic proportions for the d th document are \(\theta _d\) , where \(\theta _{d,k}\) is the topic proportion for topic k in document d . The topic assignments for the d th document are \(z_d\) , where \(z_{d,n}\) is the topic assignment for the n th word in document d . Both the topic proportions and the topic distributions over the vocabulary follow a Dirichlet distribution. Since the posterior distribution, \(p \left( \beta _{1:K},\theta _{1:D},z_{1:D}|w_{1:D}\right) \) , is intractable for exact inference, a wide variety of approximate inference algorithms, such as sampling-based (Steyvers and Griffiths 2006 ) and variational (Blei et al. 2003 ) algorithms can be considered.

In our analysis, we implement LDA to model a corpus where each document consists of the publication title, its abstract and the keywords. To exctract the relevant content and remove any unwanted nuisance terms, we performed a cleaning process (tokenization; lowercase conversion; special characters, and stop-words removal) of the text documents using the function provided in the Text Analytics Toolbox of Matlab (MATLAB 2018 ). For the analyses, the tokens with less than 10 occurrences in the corpus have been pruned. LDA analysis was performed through the fitlda Matlab routine available in the same Toolbox.

The results of this study involved different analyses. Firstly, we concentrated on the yearly quantitative distribution of literature, then we examined the conceptual structure of hate speech research. Next, we combined the results of topic and network analysis for highlighting the emerging topics, their interactions over time, the most influential countries and the academic cooperations in the retrieved themes.

Research activity

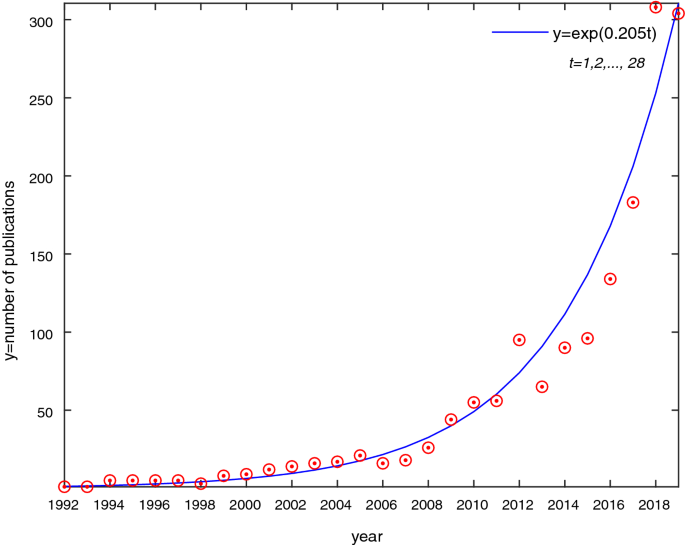

The evolution over time of the number of published documents shows a remarkable growth, highlighting the increased global focus on online hate. See Fig. 1 , in which the number of publications per year is displayed.

Since 1992, it is possible to distinguish between two different phases. During the first phase from 1992 to 2010, a slow increase in publications occurred. A higher growth rate characterises, instead, the second phase, from 2010 to 2019, testifying the growing interest. This is consistent with Price’s theory on the productivity on a given subject (Price 1963 ), according to which the development of science goes through three phases. In the preliminary phase, known as the precursor, when some scholars start publishing research into a new field, small increments in scientific literature are recorded. In the second phase, the number of publications grows exponentially, since the expansion of the field attracts an increasing number of scientists, as many aspects of the subject still have to be explored. Finally, in the third phase there is a consolidation of the body of knowledge along with a stabilisation in the productivity; therefore the aspect of the curve transforms from exponential to logistic.

To verify the rapid increase in the trend of research literature related to online hate speech, we fit an exponential growth curve to the data (Price 1963 ). According to this model the annual rate of change is equal to \(20.5\%\) . Therefore, it can be said that hate speech research is in the second phase of development: an increasing amount of research is being published, but there is still room for improvement in many aspects.

Number of publications on hate speech per year: observed and expected distribution according to an exponential growth

Conceptual structure of hate speech research

The conceptual structure of the research on hate speech is represented in Fig. 2 , where authors’ keywords, whose occurrences are greater than ten, are represented on the two dimensional plane obtained through Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA).

Conceptual map of hate speech research

The two dimensions of the maps which emerged from the MCA can be interpreted as follows. The first, horizontal, dimension separates keywords emphasizing social networks and communities and hate speech linked to religion (on the right), from those related to the political aspects of the hate speech phenomenon (on the left). This dimension explains the \(39.61\%\) of variability. The second, vertical dimension, considers machine learning techniques and accounts for the \(13.55\%\) of overall inertia. In Fig. 2 are also displayed the results obtained through a hierarchical cluster analysis carried out adopting the method of the average linkage on the factorial coordinates obtained with the MCA. A very important fact is evident from the conceptual map: three clusters represent the three major areas of research involved in the matter of hate diffusion. The blue cluster shows words as “abusive language”, “cyberbullying”, “deep learning”, “text classification”, “sentiment analysis”, “social network”, terms that bring out the problem related to automatic detection. The green cluster shows words as “human rights”, “democracy”, “incitement”, “blasphemy”, words that bring out the problem related to the legal sphere. The red cluster, the most numerous, shows words as “social network analysis”, “privacy”, “youtube”, “facebook”, “online hate”, “cyberhate”, words that bring out the problem related to social sphere and social media.

Research topics in hate speech literature

Topic modelling, performed via LDA technique, provides an additional insight in structuring the online hate research into different topics. As known, LDA algorithm needs to specify a fixed number of topics, implying that the researchers should have some idea of the possible bounds of latent features in the text. In fact, there is no unique value, appropriate in all situations and all datasets (Barua et al. 2014 ). Of course, the LDA model produces finer-grained aggregations by increasing the number of desired topics while smaller values will produce coarser-grained, more general topics. On the other hand, a higher number of topics may cause the progressive intrusion of non-relevant terms among the most probable words, affecting the semantic coherence of the retrieved themes.

In our study, we run the LDA analysis by setting the number of desired topics, in turn, equal to 10, 12, 14 and, in the end, we adopted the twelve-topic solution which guarantees a fair compromise between topic interpretability and a detailed analysis.

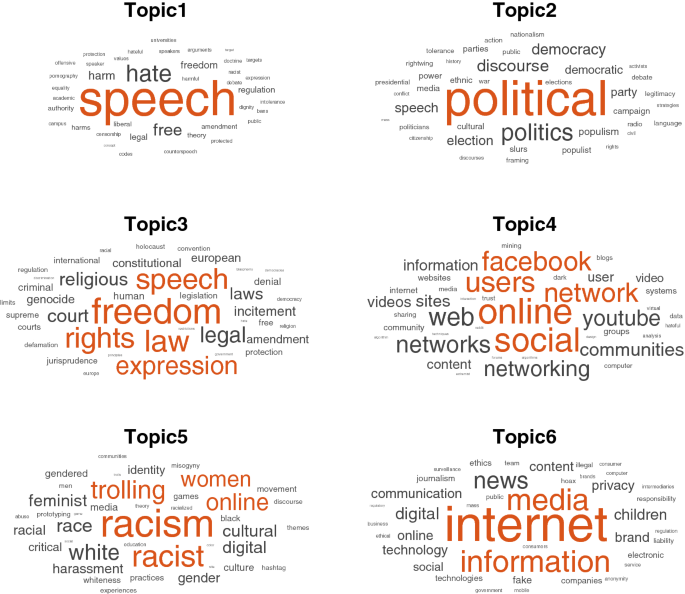

Topic interpretation

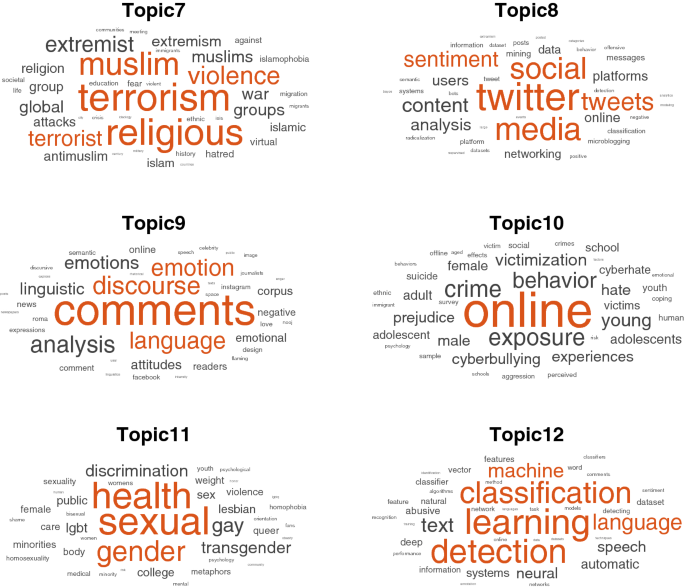

In LDA, the topics are assumed to be latent variables, which need to be meaningfully interpreted. This is usually achieved by examining the top keywords in each topic (Steyvers and Griffiths 2006 ). Figures 3 and 4 show the most relevant words for each topic, where relevance is measured normalizing the posterior word probabilities per topic by the geometric mean of the posterior probabilities for the word across all topics. Topics are sorted according to the estimated probability to be observed in the entire data set. The most relevant terms, along with their relevance measures are provided in Section 2.1 of the Supplementary Material.

The twelve identified topics reveal important areas of online hate research in the past thirty years. They can be synthetically described as dealing with the following themes.

Word clouds for topics 1–6

Word clouds for topics 7–12

Topic 1 includes words such as “speech”, “hate”, “free”, “harm”, “freedom”, suggesting a broad discussion on the debate “hate speech” versus “free speech”. The constitutional right of freedom of expression is considered also in Topic 3, mainly characterised by words like “freedom”, “law/laws”, “rights”, “expression”,“constitutional”. Topic 2 is strictly linked with the political aspects of the hate speech phenomenon and contains terms such as “political/politics/politician”, “discourse”, “democracy”, “elections”. Topic 7 covers hate speech related to religion and extremism and is described by words such as “terrorism/terrorist”, “religion/religious”, “muslim/muslims”, “violence”, “global”,“war”, “extremism/extremist”.

The online aspect of hate is clearly highlighted in Topics 4, 6, 8 and 10. In particular, Topic 4 is related to research on social networks and communities, especially Facebook and Youtube, which are large social media providers whose inner mechanisms allow users to report hate speech. Studies in Topic 8 refer to Twitter, and it is possible to stress how they make use, above all, of content and sentiment analysis. Topic 6 covers the aspect of information diffusion on the Internet, including terms like “internet”, “information”, “media”. Finally, Topic 10 considers the problem of online deviant behaviour and cyberbullying, in which relevant words are: “online”, “exposure”, “crime/crimes”, “behavior”, “cyberbullying”, “cyberhate”.

Interestingly, the distinct hate speech targets are disclosed by Topics 5 and 11. Topic 5 deals with issues on racism, as indicated by the following sets of words: “racism”, “racist”, “race”, “racial”,“white/whiteness”, “black’; in that topic we also find, among the top scoring words, some terms associated with feminism (i.e.“feminist”, “women”, “misogyny”). Topic 11 refers to hate speech linked to gender and sexual identity since the most relevant-used words are: “sexual/sexuality”, “gender”, “gay”, “trasgender”, “lesbian”, “lgbt/lgbtq”.

Finally, Topics 9 and 12 deals with methodological aspects of hate speech analysis. In particular, Topic 9 refers to the analysis of discourse and language, as suggested by the most relevant words contained in it (“comments”, “discourse”, “language”, “emotions”, “linguistic”,“corpus”). On the other hand, Topic 12 considers machine learning techniques, in fact, within this specific topic, the terms “learning”, “detection”, “classification”, “machine”,“text” are those with the top scoring.

Topic temporal evolution

To further analyse each of the topics, we focus on their dynamic changes over the years. As previously pointed out, LDA algorithm estimates each topic as a mixture of words, but also models each document as a mixture of topics. Therefore, each document can exhibit multiple topics on the base of the words used. The estimated probabilities of observing each topic in each document can be exploited to assign one or more topics to the documents of the analysed bibliographic dataset. Specifically, in this study, we decided to assign the topics with the top three highest document-topic probabilities to each document, provided the probabilities are greater than 0.2.

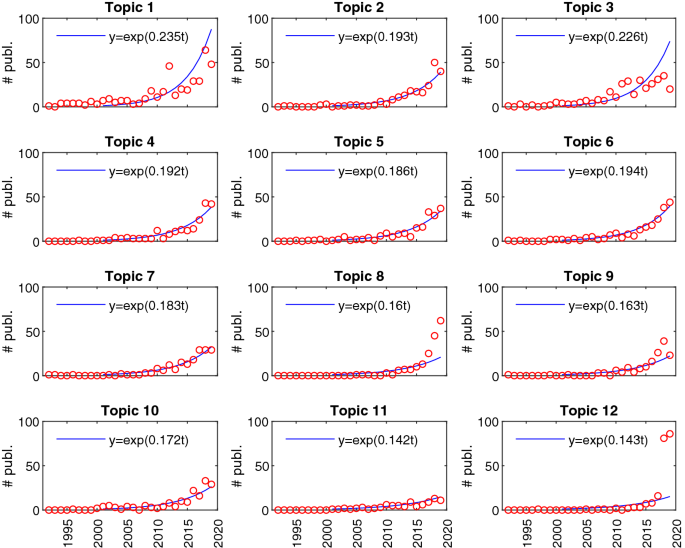

The temporal evolution of the scientific productivity for each topic can be captured through Fig. 5 , where the exponential growth model has been fitted considering the number of documents published since 2000.

Number of publications for each topic: observed and expected distributions according to an exponential growth

The temporal trend of most topics agrees with an exponential growth. However, looking at Topic 1 and Topic 3, we notice how the number of publications in the last period falls below the number expected according to the exponential law considered by Price ( 1963 ) with regard to the second phase in the development of scientific research on a given subject. We saw that the content of Topics 1 and 3 is associated with generic themes of online hate speech, thus the lesser amount of related publications in the last period reflects the interest of research community in identifying new research fronts. Conversely, the number of published documents for Topic 8 shows a sudden rise starting from 2018. This conclusion holds, even if to a lesser extend, for Topic 9 where the observed productivity rises above the expected one.

The notable case in Fig. 5 regards Topic 12, dealing with the application of the dominant and new theme of machine learning algorithms to online hate speech. In the last two years, this topic exhibits an explosive growth as for the related publication volumes. A relatively more contained rise in the size of publications is recorded for Topics 10 and 11, whose contents are associated with the specific themes of cyberhate and gendered hate.

Overall, these temporal patterns seem to suggest a shift in hate speech literature from more generic themes, about the debate on freedom of speech versus hate speech, towards research more focused on the technical aspects of hate speech detection and methodologies and techniques included in the fields of linguistics, statistics and machine learning. The appearance and development of new fields of interest and innovative ideas in the research activity on hate speech is confirmed by the heatmaps provided in the Supplementary Material, which show the number of documents, by years, assigned to the identified topics.

Topic interactions

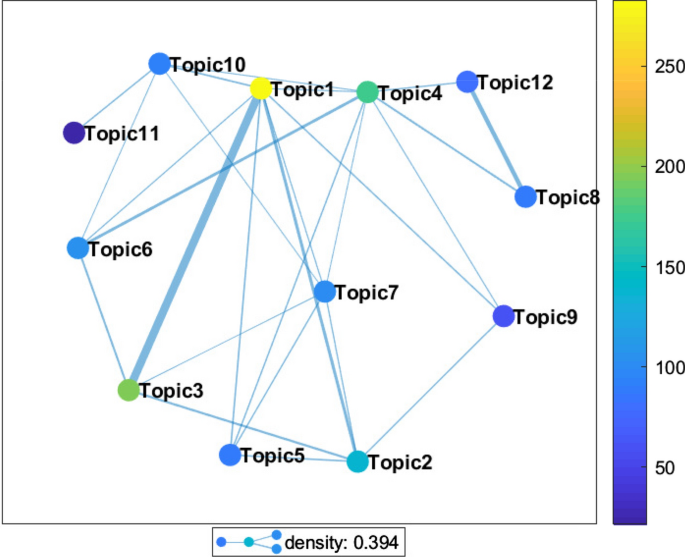

After exploring the features of the identified topics in online hate speech research, we quantitatively model their interactions and build a topic relation network. In particular, given that each document has been assigned to multiple topics, we can exploit the topic co-occurence matrix in order to understand the connections among the different themes developed in this field of research.

In Fig. 6 , we display the topic network. In the graph, the nodes are coloured according to their degree and the edges are weighted according to the co-occurences: the wider the line, the stronger the connection. Moreover, the edges whose weight is lower than the average co-occurence number have been removed. Details on the connections are provided in Section 2.3 of the Supplementary Material.

Topic co-occurence network for the publication on hate speech from 1992 to 2019

From the analysis of the links it is possible disclosing interesting relations between research fronts, which underline the multi-disciplinary nature of online hate research and the crossbreeding between different disciplines and research subjects. The strongest connection is between Topics 1 and 3, dealing respectively with the broad debate of hate speech versus free speech and the constitutional right of freedom of expression, respectively. This relation reflects the fact that both the topics are related to the boundaries of freedom of expression; accordingly, it is obvious to observe an overlapping of these two themes among documents. Through the network visualization, we see that Topic 1, being a general theme, is connected with the majority of the nodes. Other most connecting nodes are referred to the topic dealing with the questions of free speech (Topic3 ) and to the activities of hateful users on online social media (Topic 4). An interesting clique shows how closely connected are also Topics 4, 8 and 12. The interactions of this subgroup of nodes reveal the relation between computer sciences and social sciences disciplines.

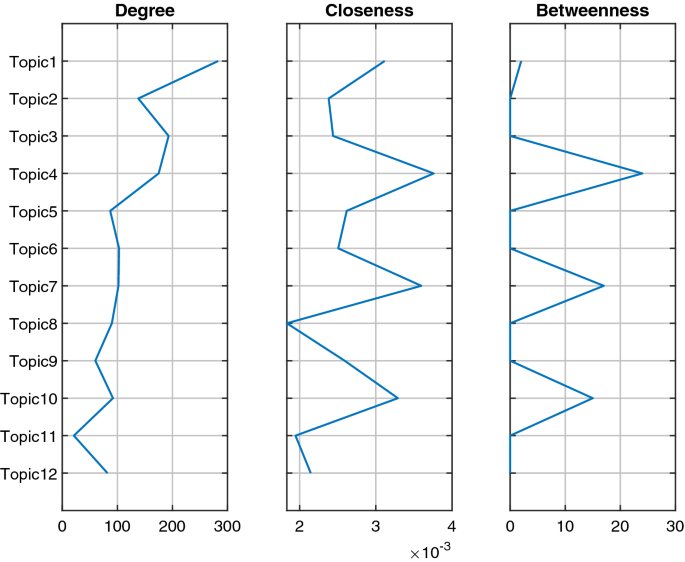

The importance of the retrieved topics in the network of connections can be inferred considering the degree centrality measures shown in Fig. 7 .

Node centrality measures

Besides, closeness and betweenness centrality scores, displayed also in Fig. 7 , are of interest to quantitatively characterize the topography of the topic co-occurrence network. Specifically, closeness centrality measures the mean distance from a vertex to other vertices (Zhang and Luo 2017 ), whereas the betweenness centrality of a node measures the extent to which the node is part of paths that connect an arbitrary pair of nodes in the network (Brandes 2001 ); put in other way betweenness measure quantifies the degree to which a node serves as a bridge. It results that the thematic topics such as “social networks and communities” (Topic 4), “religion and extremism” (Topic 7) and “cyberhate” (Topic 10) are ranked first. These findings suggest that those research areas are more effective and accessible in the network and form the densest bridges with other nodes.

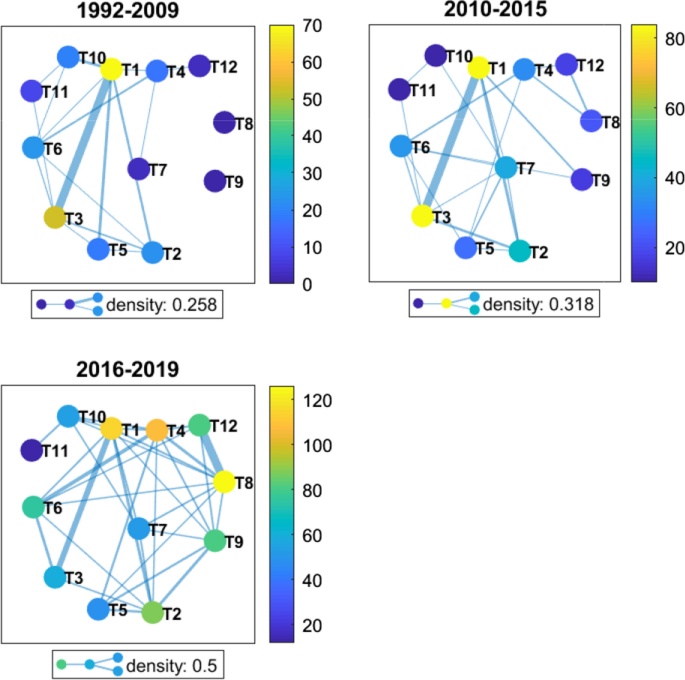

We also built the topic co-occurrence networks distinguishing three different stages in the historical development of online hate speech research, as displayed in Fig. 8 . The initial development stage refers to 1992–2009 and accounts for 227 publications; then there was the rapid development stage (2010–2015 years), when the results of research have been rapidly emerging with more than 450 scientific contributes published. Finally, we move into the last three years-period (2016–2019), when more than 300 papers are being published every year. As before, the connections in the network maps represent the interactions between the different research fields and, in each network, the edges whose weight is lower than the average co-occurrence number for the corresponding temporal interval have been suppressed.

Topic co-occurence networks

It can be seen that as new topics emerge, the network structure becomes richer in terms of connections, showing the most important footprints of the related research activities. Through a qualitative analysis of Fig. 8 , we observe that with advances in computer technology, especially developments in data or text mining and information retrieval, research on online hate speech based on computer sciences continues to receive more and more attention. In fact, from the analysis of links in the co-occurrence topic network, it was possible to identify, in the last period, interesting relations especially between Topics 8 and 12.

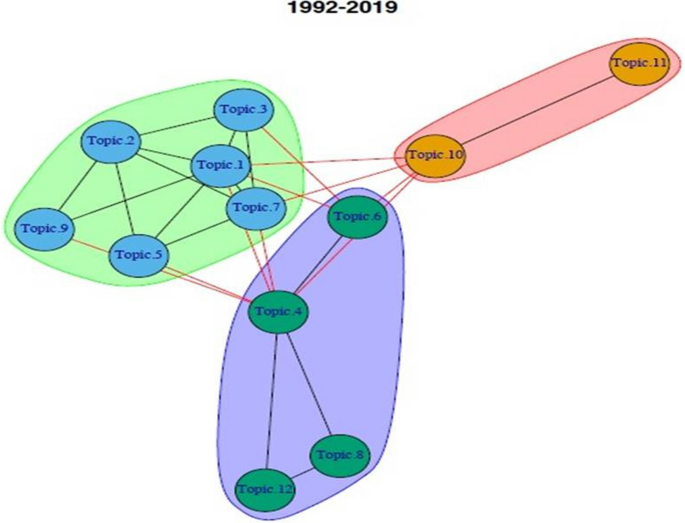

Overall, in the last thirty years, topics related to online hate research tend to arrange into three main clusters (Fig. 9 ). The fast greedy algorithm implemented in the R package igraph (Csardi and Nepusz 2006 ) was used to group the topics. The first meaningful cluster includes six topics that bring together basic themes of hate speech, covered by Topics 1,2, 3, as well as online speech designed to promote hate on the basis of race (Topic 5) and religion and extremism (Topic 7). At this group belongs also Topic 9, associated with analysis of discourse and language. In the smallest group, we find that cyberhate and gendered online hate are clustered together. Finally, Topics 4, 6, 8 and 12, in the last group, reveals that publications in this cluster deal with machine learning techniques and hateful content on online social media.

Topic clusters

Research activity in the identified topics

Influential countries in the identified topics.

Table 1 summarises the top-ten countries’ share of publication in the study of online hate speech for each of the identified clusters. Actually, for the themes of the first group (Topics 1, 3, 5, 7 and 9), owing to the presence of ex-fair scores, are displayed the first 11 publisher countries. Not surprisingly, the Anglo-Saxon States are very involved in research dealing with the general debate of “hate speech” versus “freedom of expression”. In fact, in these countries, especially in the United States, the constitutional protection of freedom of speech is vigorously defended. Conversely, other countries, mainly European countries, prohibit certain forms of speech and even the expression of certain opinions, such those to incite hatred, but also to publicly deny crimes of genocide (e.g., the Holocaust) or war crimes.

United States and United Kingdom holds the largest share of publications in the other two domains, suggesting that both these countries had a pioneering role and the strongest impact in the new strands of research focused on machine learning algorithms and text classification as a viable source for identification of hate speech as well as on investigating cyberbullying and gendered hate behaviours. Interestingly, research on automatic identification and classification of hateful languages on social media using machine learning methods emerges as an important component also in the Italian, Indian and Spanish research activity on hate speech. Finally, for the third cluster (Topics 10 and 11), we see that a not negligible number of publications on themes linked with cyberbulling and gendered hate originated from Finland, which occupies the third position in the correspondent ranking, followed by Italy and South Africa.

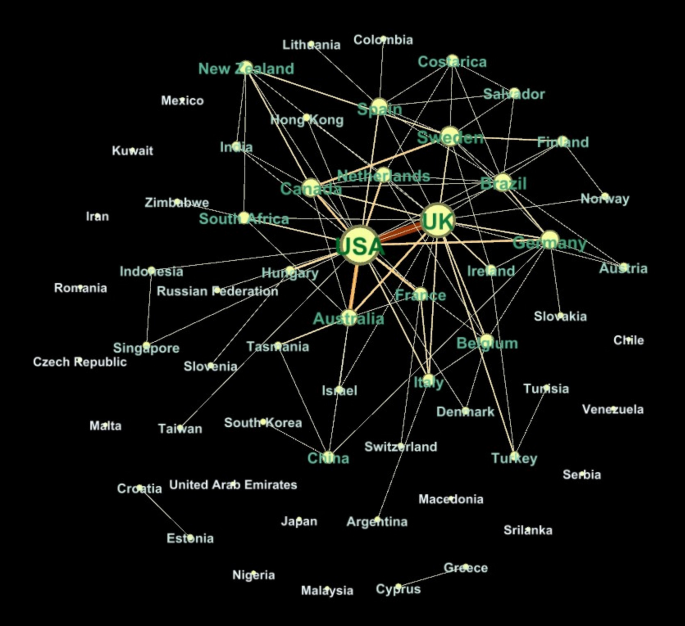

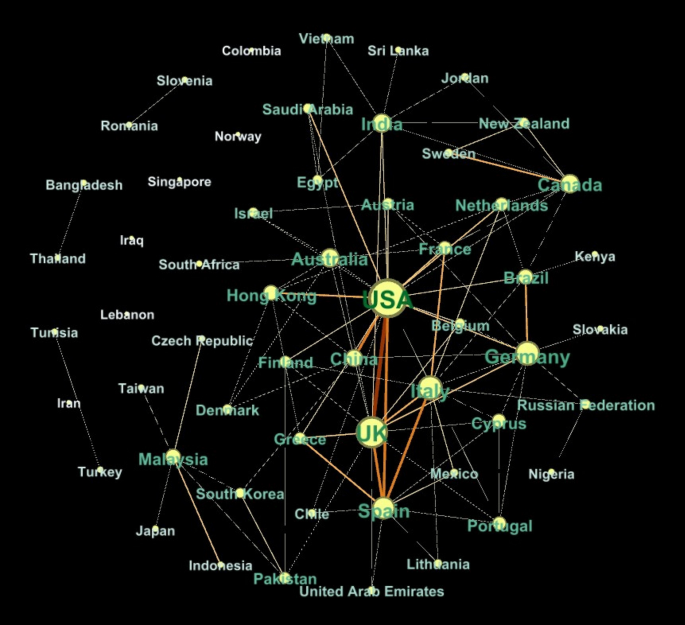

Country cooperation in the identified topics

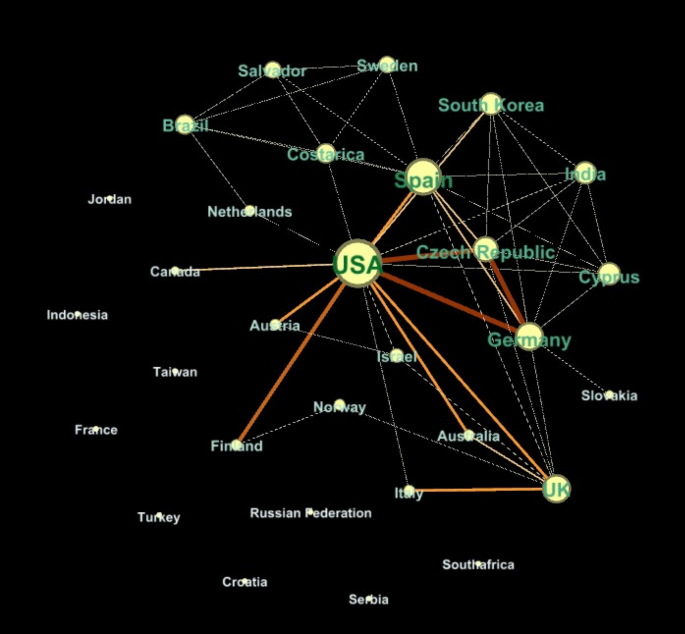

The preliminary analysis in the previous subsection depicts the overall landscape of countries contribution to the studies on online hate speech. Moving forward, by taking into account authors’ affiliation, it is possible to analyse the level of cooperation between countries. It is worth noting that country research collaboration is a valuable means since it allows scholars to share information and play their academic advantages (Ebadi and Schiffauerova 2015 ), and is deemed the hallmark of contemporary scientific production. To highlight the country research collaboration in the online hate speech research field, we constructed the countries cooperation network, displayed in the Supplementary Material. In what follows, we take into account the cooperation with respect to each of the clusters identified in the “Topic interactions” section. The characteristics of international cooperation between different countries in each domain of online hate research can be argued from the network maps visualised in Figs. 10 , 11 and 12 . We see that the United States is the major partner in international cooperation in the field of online hate speech, in all identified topic clusters. Academic cooperative connections among countries, generating research on Topics 1, 2, 3, 5, 7 and 9, primarily originate from the Unites States, United Kingdom, Germany, Brazil, Sweden and Spain. The top ranked countries by centrality, for the cluster that embraces Topics 4, 6, 8 and 12, are Unites States, United Kingdom, China, Italy, Spain, Germany and Brazil. Finally, for the research related to the remaining Topics 10 and 11, we discover a wider scientific collaboration, mainly, among United States, Spain, South Korea, Czech Republic and Germany.

Country cooperation network for topics 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 9

Country cooperation network for topics 4,6,8,12

Country cooperation network for topics 10,11

In the last years, the dynamics and usefulness of social media communications are seriously affected by hate speech (Arango et al. 2019 ), which has become a huge concern, attracting worldwide interest. The attention payed to online hate speech by the scientific research community and by policy makers is a reaction to the spread of of hate speech, in all its various forms, on the many social media and other online platforms, and to the pressing need to guarantee non-discriminatory access to digital spaces, as well.

Motivated by these concerns, this paper has presented a bibliometric study of the world’s research activity on online hate speech, performed with the aim of providing an overview of the extent of published research in this field, assessing the research output and suggesting potential, fruitful, future directions.

Beyond the identification and mapping of traditional bibliometric indicators, we focused on the contemporary structure of the field that is composed of a certain variety of themes that researchers are engaging with over the years. Through topic modelling analysis, implemented via LDA algorithm, the main research topics of online hate have been identified and grouped in categories. In contrast to previous researches, designed as qualitative literature review, this study provides a broader and quantitative analysis of publications of online hate speech. In this respect, it should be noted that although topic models do not offer new insights on representing the main area of the research, it gives to our knowledge, for the first time, the possibility of discovering latent and potentially useful contents, shape their possible structure and relationships underlying the data, with quantitative methods.

As pointed out by different authors (see, among others, Yau et al. 2014 ), the combination of topic modelling algorithms and bibliometrics allows the researcher to feature the retrieved topics with a number of topic-based analytic indicators, other than to investigate their significance and dynamic evolution, and model their quantitative relations.

Our analysis has systematically sorted the relevant international studies, producing a visual analysis of 1614 documents published in Scopus database, and generated a large amount of empirical data and information.

The following conclusions can be drawn. The volume of academic papers published in a representative sample, from 1992 to 2019, displays a significant increase after 2010; thus, in the main evolution of online hate speech research, it has been possible to identify an initial development stage (1992–2010) followed by a rapid development (2011–2019). Many countries are regularly involved in publishing in this research field, even if the majority of studies have been conducted in the context of the high-income western countries; in this respect, it is notable the research strength of United States and United Kingdom. Also, the empirical findings provide evidence for the capability of countries to build significant research cooperation. The topic analysis retrieves twelve recurring topics, which can be characterised into three clusters. Specifically, the contemporary structure of online hate literature can be viewed as composed by a group dealing with basic themes of hate speech, a collection of documents that focuses on hate-speech automatic detection and classification by machine-learning strategies and, finally, a third core which focuses on specific themes of gendered hate speech and cyberbullying. Once the groups have been created and identified, the next step is to understand the evolutionary process of each of them over the years. Looking chronologically at online hate research development, we have a trace of an overall shift from generic and knowledge based themes towards approaches that face the challenges of automatic detection of hate speech in text and hate speech addressed to specific targets. The combination of topic modelling algorithms with tools of network analysis enabled to clarify topics relation and has made clear and visible the interdisciplinary nature of the field. The confluence of online hate studies into hate-speech automatic detection and classification approaches stresses how the problem of hate diffusion should be studied not only from the social point of view but also from the point of view of computer science. In our opinion, the main reason driving the shift from conceptually oriented studies to more practically oriented ones is that there is a growing demand for finding statistical methodologies to automatically detect hate speech and make it possible to build effective counter-measures. It is worth noting, however, that the observed shift does not remove the subjective nature of hate speech denotation, given that automatic detection and classification methods need ultimately to rely on a specific definition of what communication should be interpreted as offensive, dangerous and conveying hate. Moreover, supervised techniques require an annotated set of social media contents that will be used to train the algorithms to better detect and score online comments but interpretation of hatefulness varies significantly among individual raters (Salminen et al. 2019 ). There is also evidence highlighting how people from different countries perceive hatefulness of the same online comments differently (Salminen et al. 2018 ). The authors of these studies suggest that online hate should be defined as a subjective experience rather than as an average score that is uniform to all users and that research should concentrate on how incorporate user-level features when scoring and automating the processing of online hate.

An other interesting field worth of investigation is related to the producers of online hate speech. While the online behaviour of organized hate groups has been extensivily analysed, only recently attention has focused on the behaviour of individuals that produce hate speech on the mainstream platforms (see Siegel 2020 , and references herein). Finally, future study should continue to investigate tools devoted to effectively combat online hate speech. Since content deletion or user suspension may be charged with censorship and overblocking, one alternate strategy is to oppose hate content with counter-narratives (Gagliardone et al. 2015 ). Therefore, a promising line of research is the exploration of effective counterspeech techniques which can vary according to hate speech targets, online platforms and haters characteristics.

We think that this work, based on solid data and computational analyses, might provide a clearer vision for researchers involved in this field, providing evidence of the current research frontiers and the challenges that are expected in the future, highlighting all the connections and implications of the research in several research domains.

Alghamdi, R., & Alfalqi, K. (2015). A survey of topic modeling in text mining. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications , 6 (1), 147–153. https://doi.org/10.14569/IJACSA.2015.060121 .

Article Google Scholar

Arango, A., Pérez, J., & Poblete, B. (2019). Hate speech detection is not as easy as you may think: A closer look at model validation. In: Proceedings of the 42nd International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, ACM, New York, NY, pp. 45–54, https://doi.org/10.1145/3331184.3331262 .

Aria, M., & Cuccurullo, C. (2017). Bibliometrix: an R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. Journal of Informetrics , 11 (4), 959–975. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2017.08.007 .

Barua, A., Thomas, S., & Hassan, A. (2014). What are developers talking about? An analysis of topics and trends in stack overflow. Empirical Software Engineering , 19 (3), 619–654. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10664-012-9231-y .

Beausoleil, L. E. (2019). Free, hateful, and posted: rethinking first amendment protection of hate speech in a social media world. Boston College Law Review , 60 (7), 2101–2144.

Google Scholar

Blei, D. M. (2012). Probabilistic topic models. Communications of the ACM , 55 (4), 77–84. https://doi.org/10.1145/2133806.2133826 .

Blei, D. M., Ng, A. Y., & Jordan, M. I. (2003). Latent Dirichlet allocation. Journal of Machine Learning Research , 3 (1), 993–1022. https://doi.org/10.1162/jmlr.2003.3.4-5.993 .

Article MATH Google Scholar

Brandes, U. (2001). A faster algorithm for betweenness centrality. The Journal of Mathematical Sociology , 25 (2), 163–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/0022250X.2001.9990249 .

Brettschneider, C. (2013). Value democracy as the basis for viewpoint neutrality: A theory of free speech and its implications for the state speech and limited public forum doctrines. Northwestern University Law Review , 107 , 603–646.

Cohen-Almagor, R. (2016). Hate and racist speech in the United States: A critique. Philosophy and Public Issues , 6 (1), 77–123.

Cohen-Almagor, R. (2019). Racism and hate speech: A critique of Scanlon’s contractual theory. First Amendment Studies , 53 (1–2), 41–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/21689725.2019.1601579 .

Csardi, G., & Nepusz, C. (2006). The igraph software package for complex network research. Inter Journal Complex Systems :1695, http://igraph.org

Deerwester, S., Dumais, S., Furnas, G., Landauer, T., & Harshman, R. (1990). Indexing by latent semantic analysis. Journal of the American society for information science , 41 (6), 391–407.

Ebadi, A., & Schiffauerova, A. (2015). How to receive more funding for your research? get connected to the right people. PloS One ,. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0133061 .

Fortuna, P., & Nunes, S. (2018). A survey on automatic detection of hate speech in text. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) ,. https://doi.org/10.1145/3232676 .

Gagliardone, I., Gal, D., Alves, T., & Martinez, G. (2015). Countering Online Hate Speech . Paris: UNESCO Publishing.

Greenacre, M., & Blasius, J. (2006). Multiple Correspondence Analysis and Related Methods . New York: Chapman and Hall/CRC. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781420011319 .

Book MATH Google Scholar

Greene, A. R., & Simpson, R. M. (2017). Tolerating hate in the name of democracy. The Modern Law Review , 80 (4), 746–765. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2230.12283 .

Hofmann, T. (1999). Probabilistic latent semantic indexing. In: Proceedings of the 22nd annual international ACM SIGIR conference on Research and development in information retrieval, pp. 50–57, https://doi.org/10.1145/312624.312649 .

MacAvaney, S., Yao, H. R., Yang, E., Russell, K., Goharian, N., & Frieder, O. (2019). Hate speech detection: Challenges and solutions. PloS one ,. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0221152 .

MATLAB (2018). version 9.5.0.944444 (R2018b). The MathWorks Inc., Natick, Massachusetts.

McPhee, C., Santonen, T., Shah, A., & Nazari, A. (2017). Reflecting on 10 years of the TIM review. Technology Innovation Management Review , 7 (7), 5–20. 10.22215/timreview/1087.

Price, D. J. (1963). Little Science, Big Science . New York: Columbia University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Salminen, J., Veronesi, F., Almerekhi, H., Jun, S., & Jansen, BJ. (2018). Online Hate Interpretation Varies by Country, But More by Individual: A Statistical Analysis Using Crowdsourced Ratings. In: 2018 Fifth International Conference on Social Networks Analysis, Management and Security (SNAMS), pp. 88–94, https://doi.org/10.1109/SNAMS.2018.8554954 .

Salminen, J., Almerekhi, H., Kamel, AM., Jung, S., & Jansen, BJ. (2019). Online Hate Ratings Vary by Extremes: A Statistical Analysis. In: CHIIR ’19: Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Human Information Interaction and Retrieval, Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, pp. 213–217, https://doi.org/10.1145/3295750.3298954 .

Schmidt, A., & Wiegand, M. (2017). A survey on hate speech detection using natural language processing. In: Proceedings of the Fifth International Workshop on Natural Language Processing for Social Media, Association for Computational Linguistics, pp. 1–10, https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/W17-1101 .

Sellars, AF, (2016). Defining Hate Speech. Berkman Klein Center Research Publication No. 2016-20 Paper No. 16-48, Boston University School of Law, Public Law Research, Boston University School of Law, Public Law Research, available at SSRN: https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2882244 .

Siegel, A. A. (2020). Online hate speech. In J. Tucker & N. Persily (Eds.), Social Media and Democracy: The State of the Field . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Steyvers, M., & Griffiths, T. (2006). Probabilistic topic models. In T. Landauer, D. McNamara, S. Dennis, & W. Kintsch (Eds.), Latent Semantic Analysis: A Road to Meaning . New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Strossen, N. (2016). Freedom of speech and equality: Do we have to choose? Journal of Law and Policy , 25 (1), 185–225.

Strossen, N. (2018). HATE: Why We Should Resist it With Free Speech, Not Censorship (Inalienable Rights) . New York: Oxford University Press.

Suominen, A., & Toivanen, H. (2016). Map of science with topic modeling: Comparison of unsupervised learning and human-assigned subject classification. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology ,. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23596 .

Waqas, A., Salminen, J., Jung, Sg, Almerekhi, H., & Jansen, B. (2019). Mapping online hate: A scientometric analysis on research trends and hotspots in research on online hate. PLoS One ,. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222194 .

Yau, C., Porter, A., Newman, N., & Suominen, A. (2014). Clustering scientific documents with topic modeling. Scientometrics ,. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-014-1321-8 .

Zhang, J., & Luo, Y. (2017). Degree Centrality, Betweenness Centrality, and Closeness Centrality in Social Network. In: Proceedings of the 2017 2nd International Conference on Modelling, Simulation and Applied Mathematics (MSAM2017), Advances in Intelligent Systems Research, pp. 300–303, https://doi.org/10.2991/msam-17.2017.68 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi G. D'Annunzio Chieti Pescara within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. We are grateful to the reviewers for their useful comments and suggestions which have significantly improved the quality of the paper.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Neuroscience, Imaging and Clinical Sciences, University G. d’Annunzio of Chieti–Pescara, Chieti, Italy

Alice Tontodimamma

Department of Economics, University G. d’Annunzio of Chieti–Pescara, Pescara, Italy

Eugenia Nissi

Department of Legal and Social Sciences, University G. d’Annunzio of Chieti–Pescara, Pescara, Italy

Annalina Sarra & Lara Fontanella

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Annalina Sarra .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary material 1 (pdf 508 KB)

Rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Tontodimamma, A., Nissi, E., Sarra, A. et al. Thirty years of research into hate speech: topics of interest and their evolution. Scientometrics 126 , 157–179 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03737-6

Download citation

Received : 28 January 2020

Published : 30 October 2020

Issue Date : January 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03737-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Online hate speech

- Bibliometrics analysis

- Topic models

- Latent Dirichlet allocation

Mathematics Subject Classification

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Hate Speech

Hate speech is a concept that many people find intuitively easy to grasp, while at the same time many others deny it is even a coherent concept. A majority of developed, democratic nations have enacted hate speech legislation—with the contemporary United States being a notable outlier—and so implicitly maintain that it is coherent, and that its conceptual lines can be drawn distinctly enough. Nonetheless, the concept of hate speech does indeed raise many difficult questions: What does the ‘hate’ in hate speech refer to? Can hate speech be directed at dominant groups, or is it by definition targeted at oppressed or marginalized communities? Is hate speech always ‘speech’? What is the harm or harms of hate speech? And, perhaps most challenging of all, what can or should be done to counteract hate speech?

In part because of these complexities, hate speech has spawned a vast and interdisciplinary literature. Legal scholars, philosophers, sociologists, anthropologists, political theorists, historians, and other academics have each approached the topic with exceeding interest. In this current article, however, we cannot hope to cover how these many disciplines have engaged with the concept of hate speech. Here, we will focus most explicitly on how hate speech has been taken up within philosophy, with particular emphasis on issues such as: how to define hate speech; what are the plausible harms of hate speech; how an account of hate speech might include both overt expressions of hate (e.g., the vitriolic use of slurs) as well as more covert, implicit utterances (e.g., dogwhistles); the relationship between hate speech and silencing; and what might we do to counteract hate speech.

1.1 The Harms of Hate Speech

2. religious hatred and anti-semitism, 3.2 dogwhistles and coded language, 4. pornography, hate speech, and silencing, 5.1 the case for bans, 5.2 objections to bans, and some responses, 5.3 the supported counterspeech alternative, other internet resources, related entries, 1. what is hate speech.

The term ‘hate speech’ is more than a descriptive concept used to identify a specific class of expressions. It also functions as an evaluative term judging its referent negatively and as a candidate for censure. Thus, defining this category carries serious implications. What is it that designates hate speech as a distinctive class of speech? Some claim the term ‘hate speech’ itself is misleading because it wrongly suggests “virulent dislike of a person for any reason” as a defining feature (Gelber 2017, 619). That is not, however, the way in which the term is understood among most legal theorists and philosophers. Perhaps it would be useful to start with some examples.

Bhikhu Parekh (2012) lists the following instances as examples different countries have either punished or sought to punish as hate speech:

- Shouting “[N-words] go home,” making monkey noises, and chanting racist slogans at soccer matches.

- “Islam out of Britain. Protect the British people.”

- “Arabs out of France.”

- “Serve your country, burn down a mosque.”

- “Blacks are inherently inferior, lecherous, predisposed to criminal activities, and should not be allowed to move into respectable areas.”

- “Jews are conspiratorial, devious, treacherous, sadistic, child killers, and subversive; want to take over the country; and should be carefully watched.”

- Distribution by a political party of leaflets addressed to “white fellow citizens” saying that, if it came to power, it would remove all Surinamese, Turks, and other “undesired aliens” from the Netherlands.

- A poster of a woman in a burka with text that reads: “Who knows what they have under their sinister and ugly looking clothes: stolen goods, guns, bombs even?”

- Speech that either denies or trivializes the holocaust or other crimes against humanity.

Robert Post’s four bases for defining hate speech might help us organize the features of Parekh’s list:

In law, we have to define hate speech carefully to designate the forms of the speech that will receive distinctive legal treatment. This is no easy task. Roughly speaking, we can define hate speech in terms of the harms it will cause—physical contingent harms like violence or discrimination; or we can define hate speech in terms of its intrinsic properties—the kinds of words it uses; or we can define hate speech in terms of its connection to principles of dignity; or we can define hate speech in terms of the ideas it conveys. Each of these definitions has advantages and disadvantages. Each intersects with the first amendment theory in a different way. In the end, any definition that we adopt must be justified on the ground that it will achieve the results we wish to achieve. (Herz and Molnar 2012, 31)

The four definitional bases are in terms of: (1) harm, (2) content, (3) intrinsic properties, i.e., the type of words used, and (4) dignity. One could also attempt a hybrid definition by combining the ways mentioned. But, as is made clear in Post’s remarks, definitions of this sort are relative to the interests of the definer; “We must evaluate the status of ‘hate speech’ so defined in order to determine whether it achieves what we wish to accomplish and whether the harms of the definition will outweigh its advantages” (Herz and Molnar 2012, 31). The upshot is a rejection of a univocal definition that captures “the essence” of hate speech as a phenomenon.

It is important to note that many definitions of hate speech will not fall squarely within the categories Post outlines. For instance, the UN’s International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination identifies hate speech both in terms of its content and its harmful consequences. Most definitions tend to characterize hate speech in multiple ways.

Harm-based definitions conceive of hate speech in terms of the harms to which targets are subjected. Things like discrimination or linguistic violence are candidates, though some (Gelber, 2017) argue that hate speech can harm one’s ability to participate in democratic deliberation. Susan Brison (1998a) offers a disjunctive definition that centers on a kind of abuse to targets. She defines hate speech as “speech that vilifies individuals or groups on the basis of such characteristics as race, sex, ethnicity, religion, and sexual orientation, which (1) constitutes face-to-face vilification, (2) creates a hostile or intimidating environment, or (3) is a kind of group libel” (313). ‘Harm’ as used by Brison refers to what Joel Feinberg describes “as a wrongful setback to (or invasion of) someone’s interests” (Brison, 1998b, 42).

Perhaps an immediate reaction to disjunctive definitions of the sort Brison offers is skepticism about the definitiveness of the purported list. When we go to test the definition’s application, we invariably find contestable inclusions and exclusions. Recall the examples from Parekh at the start of this section. Something like “Arabs out of France” might be included as an instance of hate speech on Brison’s account on the grounds that it creates a hostile or intimidating environment. Should statements that communicate a similar message in a less abrasive manner also be included? Suppose “Only French Nationals should occupy France” is roughly equivalent content-wise to “Arabs out of France.” If the former is indeed a less abrasive presentation though communicating the same content as the latter, what are we to make of its status? Many will find the statement odious; many will not. And since it is certainly not a face-to-face vilification or form of group libel, classifying it as hate speech will depend on how likely it is to create an intimidating or hostile environment.

The previous objection might entice one to opt for a content-based view. Content-based views define hate speech as that which “expresses, encourages, stirs up, or incites hatred against a group of individuals distinguished by a particular feature or set of features such as race, ethnicity, gender, religion, nationality, and sexual orientation” (Parekh, 2012, 40). This version makes it easier to conceive of semantically equivalent statements that differ in manner of presentation as instances of hate speech.

Content-based accounts face the challenge of determining which contents meet this standard. If the content that distinguishes hate speech from other types of speech must express, encourage, or incite hatred towards groups or individuals based on certain features, then the proponent of this view will need an account of expression. Is the speech in view that which signals the presence of a particular mental state in the speaker (i.e., hate) or that which is likely to prime feelings of animosity in a specific audience?

Another issue facing content-based approaches concerns distinguishing between speech that “respects ‘the decencies of controversy’” and that “which is outrageous and therefore hate inducing” (Post, 2009, 128). The ability to express a wide range of views, even contentious ones, is a cherished aspect of democratic societies. Failure to observe this distinction would broaden the scope of what counts as hate speech perhaps too much. In order to make this distinction, one could follow Post in tying it to “ambient social norms” that distinguish outrageous and respectful behavior. One challenge though is in determining the content of those social norms. For instance, a minority group whose opinions have little impact on the makeup of norms are unjustifiably excluded from influencing the shape of their society’s civility norms.

Definitions of hate speech based on intrinsic properties generally refer to those that emphasize the type of the speech uttered. What is at issue is the use of speech widely known to instigate offense or insult among a majority of society. Explicitly derogatory expressions like slurs are paradigmatic examples of this type of view. In general, the type of speech identified on this account is inherently derogatory, discriminatory, or vilifying.

Though attractive at first glance, classifying hate speech along these lines might prove to fall short in two ways. First, defining hate speech in this way might be too constricting. Some of the examples in our initial list would seem not to count as hate speech since they arguably lack the intrinsic features. “Arabs out of France,” for example, does not contain explicitly slurring terms. And second, this definition might prove too expansive. In cases where slurs are reappropriated by members of the target group or where artists incorporate them into a creative work, it would appear odd to count these as instances of hate speech. The concern is tied specifically to locating the issue in the terms themselves, as opposed to the use to which the terms are put.

Perhaps a final challenge to intrinsic property views can be derived from the work of Judith Butler (1997). On Butler’s account, hate speech is a kind of performative that is “always delivered twice-removed, that is, through a theory of the speech act that has its own performative power” (96). More specifically, “[w]hat hate speech does … is to constitute the subject in a subordinate position” (19). Butler locates the trouble with hate speech in its perlocutionary effects, a concept introduced by J.L. Austin that refers to the effects a speech act can have on its audience. An example of a perlocutionary effect is feeling amused at a joke or frightened from the telling of a ghost story. Unlike with intrinsic property definitions, Butler shifts focus to the nature of the acts performed rather than the terms in use. (For a critical look at Butler’s account, see Schwartzman (2002).)

Lastly, dignity-based conceptions focus primarily on the role of harms to the dignity of targets of hate speech. For instance, both Steven Heyman (2008) and Jeremy Waldron (2014) appeal to dignity in their accounts. Broadly speaking, hate speech on this kind of conception amounts to speech that undermines its target’s “basic social standing, the basis of [their] recognition as social equals and as bearers of human rights and constitutional entitlements” (Waldron, 2014, 59). This conception of hate speech will also include characterizations in terms of group defamation or group libel. Section 130 of Germany’s penal code is an example of legislation that incorporates a dignity-based conception of hate speech, prohibiting “attacks on human dignity by insulting, maliciously maligning, or defaming part of the population” (see Waldron, 2014, 8).

Worries about application follow dignity-based conceptions as well. Firstly, there may be questions about how we, in particular instances, are to distinguish between false statements about a group as a whole and those about a particular member of a group (Brown, 2017a). Presumably, only the former is consistent with an understanding of hate speech as a group-based phenomenon. Secondly, an implication of the view appears to be that it expands the range of things that would count as hate speech. Any speech that calls into question the basic standing of certain groups falls under this notion, which may make it more difficult to distinguish between contentious political speech and hate speech.

Perhaps a lesson to draw from the profusion of disjunctive definitions is a general skepticism about a definitive description of hate speech. We might concur with Alexander Brown that ‘hate speech’ is an equivocal term denoting a family of meanings (Brown 2017b, 562). According to Brown, ‘hate speech’ isn’t just a term with contested meanings, but rather, it is “systematically ambiguous; which is to say, it carries a multiplicity of different meanings” (2017b, 564). Because the expression is what is typically referred to as an essentially contested term, the hunt for a univocal or universal definition is futile.

The harms that have been attributed to hate speech comprise a long and varied list, ranging from the immediate psychological harms experienced in the moment by the person(s) targeted by an instance of hate speech, to much more long-term impacts that affect not only those targeted but whole communities, and even the strength of an entire nation.

A distinction between “assaultive hate speech” and “propagandistic hate speech” is helpful when discussing these harms (Langton 2012; 2018a; see also Gelber and McNamara (2016) who discuss “face-to-face encounters” and “incidences of general circulation”). Hate speech yelled at an individual on the street, or from a passing car, is a face-to-face encounter, and an assaultive speech act. This is, moreover, most often inter-group hate speech, where the speaker(s) are, for example, white, and the targets are non-white. On the other hand, propagandistic hate speech is often intra-group speech, spoken by members of one group to fellow ingroup members (e.g., a white person to other white people). The newsletter of the KKK, therefore, would fit into this category.