The Lightning Press SMARTbooks

Javascript & Cookies

Many features on our site require Javascript & Cookies. Please make sure these are both enabled in your browser settings.

1-800-997-8827 Customer Service and Quotes

- Subscriptions

Your cart is empty

Number Of Books

International.

Domestic Shipping (US & APO/FPO/DPO)

Economy/Saver Shipping (5-20 Days)

Expedited shipping (2-5 Days)

Shipping to Canada Rates

Economy/Saver Shipping (5-11 Days)

Expedited shipping (3-6 Days)

Global Shipping Rates

Economy/Saver Shipping (9-20 Days)

Expedited shipping (4-10 Days)

Processing & Handling

Start reading sooner. Just $10 for RUSH processing & handling. Learn more

RUSH Handling (+$10)

- All Books (Purchase/Order)

- Discount SMARTsets

- Military Reference: Multi-Service & Specialty

- Military Reference: Joint & Service-Level

- Joint Strategic, Interagency, & National Security

- Threat, OPFOR, Regional & Cultural

- Homeland Defense, DSCA, Disaster & National Response

- SMARTupdates (Keep your SMARTbooks up-to-date!)

Books in Development

Digital smartbooks.

- Digital FAQs & Help (Adobe Digital Editions)

- SMARTupdates, Changes, and Revisions

- SMARTnews Blog

- SMARTregister

- SMARTleader Program

- Join the Mailing List

- Government Sales

- Quote and Pro Forma Invoices

- Shipping and Handling

- SMARTbook Payment/Order Options

- About SMARTbooks

- About The Lightning Press

- Contributing Authors

- Author/Book Submissions

- Reseller Inquiries

- Reader Comments

- SMARTbook Design, Composition & Production Services

Remember to check out our Digital/Ebooks tab for Immediate Download!

Intelligence preparation of the battlefield (ipb), military reference: multi-service & specialty.

BSS7: The Battle Staff SMARTbook, 7th Ed.

SUTS3: The Small Unit Tactics SMARTbook, 3rd Ed.

TLS7: The Leader’s SMARTbook, 7th Ed.

SMFLS5: The Sustainment & Multifunctional Logistics SMARTbook, 5th Ed.

TAA2: The Military Engagement, Security Cooperation & Stability SMARTbook, 2nd Ed. (w/Change 1)

Military Reference: Service-level

AODS7: The Army Operations & Doctrine SMARTbook, 7th Ed.

MAGTF: The MAGTF Operations & Planning SMARTbook

MEU3: The Marine Expeditionary Unit SMARTbook, 3rd Ed.

The Naval Operations & Planning SMARTbook

AFOPS2: The Air Force Operations & Planning SMARTbook, 2nd Ed.

Joint, Strategic, Interagency, & National Security

JFODS6: The Joint Forces Operations & Doctrine SMARTbook, 6th Ed.

Joint/Interagency SMARTbook 1 – Joint Strategic & Operational Planning, 3rd Ed.

INFO1: The Information Operations & Capabilities SMARTbook

CYBER1-1: The Cyberspace Operations & Electronic Warfare SMARTbook (w/SMARTupdate 1)

CTS1: The Counterterrorism, WMD & Hybrid Threat SMARTbook

Threat, OPFOR, Regional & Cultural

OPFOR SMARTbook 1 - Chinese Military

OPFOR SMARTbook 2 - North Korean Military

OPFOR SMARTbook 3 - Red Team Army, 2nd Ed.

OPFOR SMARTbook 4 - Iran & the Middle East

OPFOR SMARTbook 5 - Irregular & Hybrid Threat

Homeland Defense, DSCA, & Disaster Response

HDS1: The Homeland Defense & DSCA SMARTbook

Disaster Response SMARTbook 1 – Federal/National Disaster Response

Disaster Response SMARTbook 2 – Incident Command System (ICS)

Disaster Response SMARTbook 3 - Disaster Preparedness, 2nd Ed.

SMARTupdates

Change 1 (July 2019 ADPs) SMARTupdate to AODS6

Change 1 (Aug ‘21) SMARTupdate to CYBER1

The ''WARFIGHTING'' SUPERset (7 books)

The ''ARMY'' SMARTset (5 books)

''Multidomain Operations'' Planner's SMARTset (2 books)

The ''OPFOR THREAT'' SMARTset (5 books)

The ''JOINT FORCES + JOINT/INTERAGENCY'' SMARTset (2 books)

The ''INFO + CYBER'' SMARTset (2 books)

The ''NAVY'' SMARTset (3 books)

The ''AIR FORCE'' SMARTset (3 books)

The ''MAGTF + MEU'' SMARTset (2 books)

The ''DISASTER RESPONSE'' SMARTset (3 books)

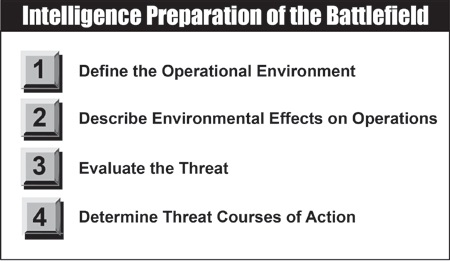

Intelligence preparation of the battlefield (IPB) is the systematic process of analyzing the mission variables of enemy, terrain, weather, and civil considerations in an area of interest to determine their effect on operations.

IPB allows commanders and staffs to take a holistic approach to analyzing the operational environment (OE). A holistic approach—

• Describes the totality of relevant aspects of the OE that may impact friendly, threat, and neutral forces. • Accounts for all relevant domains that may impact friendly and threat operations. • Identifies windows of opportunity to leverage friendly capabilities against threat forces. • Allows commanders to leverage positions of relative advantage at a time and place most advantageous for mission success with the most accurate information available.

IPB results in intelligence products that are used during the military decisionmaking process (MDMP) to assist in developing friendly courses of action (COAs) and decision points for the commander. Additionally, the conclusions reached and the products (which are included in the intelligence estimate)developed during IPB are critical to planning information collection and targeting operations. IPB products include—

• Threat situation templates with associated COA statements and high-value target (HVT) lists. • Event templates and associated event matrices. • Modified combined obstacle overlays (MCOOs), terrain effects matrices, and terrain assessments. • Weather effects work aids—weather forecast charts, weather effects matrices, light and illumination tables, and weather estimates. • Civil considerations overlays and assessments.

The IPB process consists of the following four steps:

Step 1—Define The Operational Environment

An operational environment is a composite of the conditions, circumstances, and influences that affect the employment of capabilities and bear on the decisions of the commander (JP 3-0). An OE for any specific operation comprises more than the interacting variables that exist within a specific physical area. It also involves interconnected influences from the global or regional perspective (such as politics, economics) that affect OE conditions and operations. Thus, each commander’s OE is part of a higher commander’s OE. Defining the OE results in the identification of—

• Significant characteristics of the OE that can affect friendly and threat operations. • Gaps in current intelligence holdings.

Step 1 is important because it assists the commander in defining relative aspects of the OE in time and space. This is equally important when considering characteristics of multi-domain OEs. Aspects of these OEs may act simultaneously across the battlefield but may only factor in friendly or threat operations at specific times and locations.

During step 1, the intelligence staff must identify those significant characteristics related to the mission variables of enemy, terrain and weather, and civil considerations that are relevant to the mission. The intelligence staff evaluates significant characteristics to identify gaps and initiate information collection. The intelligence staff then justifies the analysis to the commander. Failure to identify or misidentifying the effect these variables may have on operations at a given time and place can hinder decision making and result in the development of an ineffective information collection strategy. During step 1, the area of operations (AO), AOI, and area of influence must also be identified and established.

Understanding friendly and threat forces is not enough; other factors, such as culture, languages, tribal affiliations, and operational and mission variables, can be equally important. Identifying the significant characteristics of the OE is essential in identifying the additional information needed to complete IPB. Once approved by the commander, this information becomes the commander’s initial intelligence requirements—which focus the commander’s initial information collection efforts and the remaining steps of the IPB process.

Additionally, where a unit will be assigned and how its operations will synchronize with other associated operations must be considered. For example, the G-2/S-2 should be forming questions regarding where the unit will deploy within the entire theater of operations and the specific logistics requirements needed to handle the operation’s contingency plans.

Step 2—Describe Environmental Effects On Operations

During step 2 of the IPB process, the intelligence staff describes how significant characteristics affect friendly operations. The intelligence staff also describes how terrain, weather, civil considerations, and friendly forces affect threat forces. This evaluation focuses on the general capabilities of each force until the development of threat COAs in step 4 of IPB and friendly COAs later in the MDMP. The entire staff determines the effects of friendly and threat force actions on the population.

If the intelligence staff does not have the information required to form conclusions, it uses assumptions to fill information gaps—always careful to ensure the commander understands when assumptions are used in place of facts to form conclusions.

Step 3—Evaluate The Threat

The purpose of evaluating the threat is to understand how a threat can affect friendly operations. Although threat forces may conform to some of the fundamental principles of warfare that guide Army operations, these forces will have obvious, as well as subtle, differences in how they approach situations and problem solving. Understanding these differences is essential to understanding how a threat force will react in a given situation.

Threat evaluation does not begin with IPB. The intelligence staff conducts threat evaluations and creates threat models during generate intelligence knowledge of the intelligence support to force generation task. Using this information, the intelligence staff refines threat models, as necessary, to support IPB. When analyzing a well-known threat, the intelligence staff may be able to rely on previously developed threat models. When analyzing a new or less well-known threat, the intelligence staff may need to evaluate the threat and develop threat models during the MDMP’s mission analysis step. When this occurs, the intelligence staff relies heavily on the threat evaluation conducted by higher headquarters and other intelligence agencies.

In situations where there is no threat force, the intelligence analysis conducted and the products developed relating to terrain, weather, and civil considerations may be sufficient to support planning. An example of this type of situation is a natural disaster.

Step 4—Determine Threat Courses Of Action

During step 4, the intelligence staff identifies and develops possible threat COAs that can affect accomplishing the friendly mission. The staff uses the products associated with determining threat COAs to assist in developing and selecting friendly COAs during COA steps of the MDMP. Identifying and developing all valid threat COAs minimize the potential of surprise to the commander by an unanticipated threat action.

Failure to fully identify and develop all valid threat COAs may lead to the development of an information collection strategy that does not provide the information necessary to confirm what COA the threat has taken and may result in friendly forces being surprised and possibly defeated. When needed, the staff should identify all significant civil considerations (this refers to those civil considerations identified as OE significant characteristics) to portray the interrelationship of the threat, friendly forces, and population activities.

The staff develops threat COAs in the same manner friendly COAs are developed. The COA development discussion in ADRP 5-0 is an excellent model for developing valid threat COAs that are suitable, feasible, acceptable, unique, and consistent with threat doctrine or patterns of operation. Although the intelligence staff has the primary responsibility for developing threat COAs, it needs assistance from the rest of the staff to present the most accurate and complete analysis to the commander.

Browse additional military doctrine articles in our SMARTnews Blog & Resource Center .

About The Lightning Press SMARTbooks. Recognized as a “whole of government” doctrinal reference standard by military, national security and government professionals around the world, SMARTbooks comprise a comprehensive professional library. SMARTbooks can be used as quick reference guides during operations, as study guides at education and professional development courses, and as lesson plans and checklists in support of training. Browse our collection of Military Reference SMARTbooks to learn more.

Subscribe to the SMARTnews mailing list!

Best military books on leadership, strategy & tactics.

The Lightning Press publishes the best non-fiction reference books on military leadership and war strategy for active-duty and reserve military personnel and civilians.

Recognized as a “whole of government” doctrinal reference standard by military, national security and government professionals around the world, SMARTbooks comprise a comprehensive professional library designed for all levels of Service.

SMARTbooks can be used as quick reference guides during military operations, as study guides at education and professional development courses, and as lesson plans and checklists in support of training.

Download our signed 889 v4 Representation Form on file, or we can complete an alternate version.

SMARTbook Catalog

Download and print the latest SMARTbook catalog!

Download PDF Catalog

In addition to paperback, SMARTbooks are also available in digital (eBook) format. Our digital SMARTbooks are for use with Adobe Digital Editions and can be transferred to up to six computers and six devices with free software available for 85+ devices and platforms.

SMARTnews Email List

Join our SMARTnews mailing list to receive free email notification of new titles, updates, revisions, doctrinal changes, and member-only discounts to our SMARTbooks!

Contact and Support Information

- Customer Service and Quotes: 863-409-8084 (Mon-Fri 0800-1700 EST) or 1-800-997-8827 (24-hour voicemail)

- Email: [email protected]

- SMARTnews: Signup for the latest news and releases

- SMARTupdates: Signup to keep up to date on updates and revisions

Copyright © 2024 Norman M. Wade, The Lightning Press Website Development and Management by thirteen05 creative

- Military Reference Categories/Books

- National Power Categories/Books

- Reader Support

Panduan Penulisan Policy Brief 2021

- September 4, 2021

- Insentif Publikasi / Policy Brief

Guna mendorong peningkatan kontribusi IPB dalam perumusan rekomendasi kebijakan di tingkat nasional maupun internasional, Direktorat Publikasi Ilmiah dan Informasi Strategis (DPIS) mengadakan program insentif penulisan Policy Brief. Program ini merupakan bagian dari upaya untuk menghasilkan dan meningkatkan produk science to policy interfacing yang lebih berkualitas.

Policy Brief ini akan kami publikasikan melalui media online yang dikelola oleh DPIS. Policy Brief kami terima paling lambat tanggal 30 Oktober 2021 .

Panduan dan template penulisan serta pengiriman naskah policy brief dapat diakses pada tautan berikut:

- Panduan dan Template Penulisan Policy Brief_DPIS_2020

- Form Upload Policy Brief

Informasi lebih lanjut mengenai program ini dapat menghubungi Sdr. Sangadji (WA: 081287101143) atau mengirimkan email ke: [email protected]

Komentar anda Cancel reply

- Struktur Organisasi

- Strategic Talks

- Policy Brief

- Artikel Populer

- Update Publikasi Ilmiah

- Daftar Jurnal IPB University

- Pendampingan Jurnal

- Journal Camp

- Tentang Layanan Bahasa Inggris

- Layanan Cek Bahasa Inggris (Grammarly)

- Layanan Edit Bahasa Inggris (Paperpal)

- Tentang Similaritas

- Layanan Cek Similaritas (Turnitin)

- Tentang Proofread

- Layanan Proofread Q1/Q2 (Enago)

- Layanan Proofread Q1/Q2 (Editage)

- Layanan Proofread Q3 (GoodLingua)

- FAQ Pemutakhiran SINTA

- APC (Article Processing Charge)

- Bantuan Publikasi Subscription

- Tentang Post Doctoral

- Pengumuman Nominal Pendanaan Program Hibah Post-Doctoral Tahun 2024

- Pengumuman Hibah Post Doctoral 2024

- Jurnal Terindeks Scopus

- Insentif Buku Ajar

- Insentif Policy Brief

- Insentif Artikel Populer

Writing and formatting

Any paper published in a leading research journal should clearly and concisely demonstrate a substantial, novel and interesting scientific result. There are three stages to preparing a paper for submission to a journal: planning, writing and editing.

Consider the best way to structure your paper before you begin to write it. Some journals have templates available which can assist you with structuring. Different sections that typically appear in scientific papers are described below.

The title attracts the attention of your desired readership at a glance and should distinguish your paper from other published work. You might choose an eye-catching title to appeal to as many readers as possible, or a more descriptive title to engage readers with a specific interest in the subject of your paper.

The abstract very concisely describes the contents of your paper. It states simply what work you undertook, your results and your conclusions. Importantly, like the title, the abstract will help potential readers to decide whether your full paper will be of interest to them. Abstracts are usually less than 200 words in length and should not contain undefined abbreviations or jargon.

The introduction clearly states the object of your work, its scope and the main advances you are reporting. It gives reference to relevant results of previously published work.

A theoretical and experimental methods section gives sufficient information to allow another researcher to duplicate your method.

The results and discussion section states your results and their potential implications. In the discussion you should state the impact of your results compared with recent work.

Conclusions summarise key results and may include any plans for relevant future work.

Acknowledgments recognise the contribution of funding bodies and anyone who has assisted in the work.

References list relevant papers referred to in the other sections, citing original works both historical and recent.

Carefully chosen and well prepared figures , such as diagrams and photos, can greatly enhance your article. We encourage you to prepare figures that are clear, easy to read, and of the best possible quality.

2D simulation of primary recrystallization with an initial uniform stored energy M Bernacki, H Resk, T Coupez and R E Logé 2009 Modelling Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 17 064006.

Once you have established a plan, you can begin writing your paper. You may wish to consider the following tips for good writing practice.

Clarity is crucial. Your paper must be easy to understand. Consider the readership of your chosen journal, bearing in mind the knowledge expected of that audience. You should introduce any ideas that may be unfamiliar to your readers early in the paper so that your results can be easily understood. Your paper must be written in correct English. If you lack experience of writing in English you may wish to consult a native speaker for assistance. Some journal publishers offer assistance in language editing.

Conciseness is effective in holding the attention of readers. All content of your paper should be relevant to your main scientific result. Convey your ideas concisely by avoiding overlong sentences and paragraphs. However, avoid making it so concise that it loses clarity.

On completion of the first draft, carefully re-read your paper and make any amendments that will improve the content. When editing your paper, reconsider your original plan. It might be necessary to alter the structure of your paper to better fit your original outline. You may decide to rewrite portions of your paper to improve clarity and conciseness. You should repeat these processes over several successive drafts if necessary. When complete, send the paper to colleagues and co-authors for feedback. When all co-authors are satisfied that the draft is ready to be submitted to a journal, carry out one final spelling and grammar check before submission.

2D distributions of plasma properties in the ICP reactor chamber during CF 4 plasma etching of SiO 2 : (left) electron density, (centre) F density, (right) F – density H Fukumoto et al 2009 Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 18 045027.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Example of a great essay | Explanations, tips & tricks

Example of a Great Essay | Explanations, Tips & Tricks

Published on February 9, 2015 by Shane Bryson . Revised on July 23, 2023 by Shona McCombes.

This example guides you through the structure of an essay. It shows how to build an effective introduction , focused paragraphs , clear transitions between ideas, and a strong conclusion .

Each paragraph addresses a single central point, introduced by a topic sentence , and each point is directly related to the thesis statement .

As you read, hover over the highlighted parts to learn what they do and why they work.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about writing an essay, an appeal to the senses: the development of the braille system in nineteenth-century france.

The invention of Braille was a major turning point in the history of disability. The writing system of raised dots used by visually impaired people was developed by Louis Braille in nineteenth-century France. In a society that did not value disabled people in general, blindness was particularly stigmatized, and lack of access to reading and writing was a significant barrier to social participation. The idea of tactile reading was not entirely new, but existing methods based on sighted systems were difficult to learn and use. As the first writing system designed for blind people’s needs, Braille was a groundbreaking new accessibility tool. It not only provided practical benefits, but also helped change the cultural status of blindness. This essay begins by discussing the situation of blind people in nineteenth-century Europe. It then describes the invention of Braille and the gradual process of its acceptance within blind education. Subsequently, it explores the wide-ranging effects of this invention on blind people’s social and cultural lives.

Lack of access to reading and writing put blind people at a serious disadvantage in nineteenth-century society. Text was one of the primary methods through which people engaged with culture, communicated with others, and accessed information; without a well-developed reading system that did not rely on sight, blind people were excluded from social participation (Weygand, 2009). While disabled people in general suffered from discrimination, blindness was widely viewed as the worst disability, and it was commonly believed that blind people were incapable of pursuing a profession or improving themselves through culture (Weygand, 2009). This demonstrates the importance of reading and writing to social status at the time: without access to text, it was considered impossible to fully participate in society. Blind people were excluded from the sighted world, but also entirely dependent on sighted people for information and education.

In France, debates about how to deal with disability led to the adoption of different strategies over time. While people with temporary difficulties were able to access public welfare, the most common response to people with long-term disabilities, such as hearing or vision loss, was to group them together in institutions (Tombs, 1996). At first, a joint institute for the blind and deaf was created, and although the partnership was motivated more by financial considerations than by the well-being of the residents, the institute aimed to help people develop skills valuable to society (Weygand, 2009). Eventually blind institutions were separated from deaf institutions, and the focus shifted towards education of the blind, as was the case for the Royal Institute for Blind Youth, which Louis Braille attended (Jimenez et al, 2009). The growing acknowledgement of the uniqueness of different disabilities led to more targeted education strategies, fostering an environment in which the benefits of a specifically blind education could be more widely recognized.

Several different systems of tactile reading can be seen as forerunners to the method Louis Braille developed, but these systems were all developed based on the sighted system. The Royal Institute for Blind Youth in Paris taught the students to read embossed roman letters, a method created by the school’s founder, Valentin Hauy (Jimenez et al., 2009). Reading this way proved to be a rather arduous task, as the letters were difficult to distinguish by touch. The embossed letter method was based on the reading system of sighted people, with minimal adaptation for those with vision loss. As a result, this method did not gain significant success among blind students.

Louis Braille was bound to be influenced by his school’s founder, but the most influential pre-Braille tactile reading system was Charles Barbier’s night writing. A soldier in Napoleon’s army, Barbier developed a system in 1819 that used 12 dots with a five line musical staff (Kersten, 1997). His intention was to develop a system that would allow the military to communicate at night without the need for light (Herron, 2009). The code developed by Barbier was phonetic (Jimenez et al., 2009); in other words, the code was designed for sighted people and was based on the sounds of words, not on an actual alphabet. Barbier discovered that variants of raised dots within a square were the easiest method of reading by touch (Jimenez et al., 2009). This system proved effective for the transmission of short messages between military personnel, but the symbols were too large for the fingertip, greatly reducing the speed at which a message could be read (Herron, 2009). For this reason, it was unsuitable for daily use and was not widely adopted in the blind community.

Nevertheless, Barbier’s military dot system was more efficient than Hauy’s embossed letters, and it provided the framework within which Louis Braille developed his method. Barbier’s system, with its dashes and dots, could form over 4000 combinations (Jimenez et al., 2009). Compared to the 26 letters of the Latin alphabet, this was an absurdly high number. Braille kept the raised dot form, but developed a more manageable system that would reflect the sighted alphabet. He replaced Barbier’s dashes and dots with just six dots in a rectangular configuration (Jimenez et al., 2009). The result was that the blind population in France had a tactile reading system using dots (like Barbier’s) that was based on the structure of the sighted alphabet (like Hauy’s); crucially, this system was the first developed specifically for the purposes of the blind.

While the Braille system gained immediate popularity with the blind students at the Institute in Paris, it had to gain acceptance among the sighted before its adoption throughout France. This support was necessary because sighted teachers and leaders had ultimate control over the propagation of Braille resources. Many of the teachers at the Royal Institute for Blind Youth resisted learning Braille’s system because they found the tactile method of reading difficult to learn (Bullock & Galst, 2009). This resistance was symptomatic of the prevalent attitude that the blind population had to adapt to the sighted world rather than develop their own tools and methods. Over time, however, with the increasing impetus to make social contribution possible for all, teachers began to appreciate the usefulness of Braille’s system (Bullock & Galst, 2009), realizing that access to reading could help improve the productivity and integration of people with vision loss. It took approximately 30 years, but the French government eventually approved the Braille system, and it was established throughout the country (Bullock & Galst, 2009).

Although Blind people remained marginalized throughout the nineteenth century, the Braille system granted them growing opportunities for social participation. Most obviously, Braille allowed people with vision loss to read the same alphabet used by sighted people (Bullock & Galst, 2009), allowing them to participate in certain cultural experiences previously unavailable to them. Written works, such as books and poetry, had previously been inaccessible to the blind population without the aid of a reader, limiting their autonomy. As books began to be distributed in Braille, this barrier was reduced, enabling people with vision loss to access information autonomously. The closing of the gap between the abilities of blind and the sighted contributed to a gradual shift in blind people’s status, lessening the cultural perception of the blind as essentially different and facilitating greater social integration.

The Braille system also had important cultural effects beyond the sphere of written culture. Its invention later led to the development of a music notation system for the blind, although Louis Braille did not develop this system himself (Jimenez, et al., 2009). This development helped remove a cultural obstacle that had been introduced by the popularization of written musical notation in the early 1500s. While music had previously been an arena in which the blind could participate on equal footing, the transition from memory-based performance to notation-based performance meant that blind musicians were no longer able to compete with sighted musicians (Kersten, 1997). As a result, a tactile musical notation system became necessary for professional equality between blind and sighted musicians (Kersten, 1997).

Braille paved the way for dramatic cultural changes in the way blind people were treated and the opportunities available to them. Louis Braille’s innovation was to reimagine existing reading systems from a blind perspective, and the success of this invention required sighted teachers to adapt to their students’ reality instead of the other way around. In this sense, Braille helped drive broader social changes in the status of blindness. New accessibility tools provide practical advantages to those who need them, but they can also change the perspectives and attitudes of those who do not.

Bullock, J. D., & Galst, J. M. (2009). The Story of Louis Braille. Archives of Ophthalmology , 127(11), 1532. https://doi.org/10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.286.

Herron, M. (2009, May 6). Blind visionary. Retrieved from https://eandt.theiet.org/content/articles/2009/05/blind-visionary/.

Jiménez, J., Olea, J., Torres, J., Alonso, I., Harder, D., & Fischer, K. (2009). Biography of Louis Braille and Invention of the Braille Alphabet. Survey of Ophthalmology , 54(1), 142–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.survophthal.2008.10.006.

Kersten, F.G. (1997). The history and development of Braille music methodology. The Bulletin of Historical Research in Music Education , 18(2). Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/40214926.

Mellor, C.M. (2006). Louis Braille: A touch of genius . Boston: National Braille Press.

Tombs, R. (1996). France: 1814-1914 . London: Pearson Education Ltd.

Weygand, Z. (2009). The blind in French society from the Middle Ages to the century of Louis Braille . Stanford: Stanford University Press.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

An essay is a focused piece of writing that explains, argues, describes, or narrates.

In high school, you may have to write many different types of essays to develop your writing skills.

Academic essays at college level are usually argumentative : you develop a clear thesis about your topic and make a case for your position using evidence, analysis and interpretation.

The structure of an essay is divided into an introduction that presents your topic and thesis statement , a body containing your in-depth analysis and arguments, and a conclusion wrapping up your ideas.

The structure of the body is flexible, but you should always spend some time thinking about how you can organize your essay to best serve your ideas.

Your essay introduction should include three main things, in this order:

- An opening hook to catch the reader’s attention.

- Relevant background information that the reader needs to know.

- A thesis statement that presents your main point or argument.

The length of each part depends on the length and complexity of your essay .

A thesis statement is a sentence that sums up the central point of your paper or essay . Everything else you write should relate to this key idea.

A topic sentence is a sentence that expresses the main point of a paragraph . Everything else in the paragraph should relate to the topic sentence.

At college level, you must properly cite your sources in all essays , research papers , and other academic texts (except exams and in-class exercises).

Add a citation whenever you quote , paraphrase , or summarize information or ideas from a source. You should also give full source details in a bibliography or reference list at the end of your text.

The exact format of your citations depends on which citation style you are instructed to use. The most common styles are APA , MLA , and Chicago .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bryson, S. (2023, July 23). Example of a Great Essay | Explanations, Tips & Tricks. Scribbr. Retrieved March 25, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/example-essay-structure/

Is this article helpful?

Shane Bryson

Shane finished his master's degree in English literature in 2013 and has been working as a writing tutor and editor since 2009. He began proofreading and editing essays with Scribbr in early summer, 2014.

Other students also liked

How to write an essay introduction | 4 steps & examples, academic paragraph structure | step-by-step guide & examples, how to write topic sentences | 4 steps, examples & purpose, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Templates and guidelines for proceedings papers

These are our templates and guidelines for proceedings papers, they are there to to help you prepare your work.

Essential guidelines

Please follow these essential guidelines when preparing your paper:

- Basic guidelines for preparing a paper

- Style guide for conference organisers and authors

Authors must prepare their papers using our Microsoft Word or LaTeX2e templates, and then convert these to PDF format for submission:

- Microsoft Word templates

- LaTeX2e class file

If you would like to submit multimedia to accompany your paper, you might find these guidelines useful:

- Multimedia guidelines

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Academic Writing

How to Format an Essay

Last Updated: August 26, 2022 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Carrie Adkins, PhD and by wikiHow staff writer, Aly Rusciano . Carrie Adkins is the cofounder of NursingClio, an open access, peer-reviewed, collaborative blog that connects historical scholarship to current issues in gender and medicine. She completed her PhD in American History at the University of Oregon in 2013. While completing her PhD, she earned numerous competitive research grants, teaching fellowships, and writing awards. There are 11 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 85,080 times.

You’re opening your laptop to write an essay, knowing exactly what you want to write, but then it hits you—you don’t know how to format it! Using the correct format when writing an essay can help your paper look polished and professional while earning you full credit. There are 3 common essay formats—MLA, APA, and Chicago Style—and we’ll teach you the basics of properly formatting each in this article. So, before you shut your laptop in frustration, take a deep breath and keep reading because soon you’ll be formatting like a pro.

Setting Up Your Document

- If you can’t find information on the style guide you should be following, talk to your instructor after class to discuss the assignment or send them a quick email with your questions.

- If your instructor lets you pick the format of your essay, opt for the style that matches your course or degree best: MLA is best for English and humanities; APA is typically for education, psychology, and sciences; Chicago Style is common for business, history, and fine arts.

- Most word processors default to 1 inch (2.5 cm) margins.

- Do not change the font size, style, or color throughout your essay.

- Change the spacing on Google Docs by clicking on Format , and then selecting “Line spacing.”

- Click on Layout in Microsoft Word, and then click the arrow at the bottom left of the “paragraph” section.

- Using the page number function will create consecutive numbering.

- When using Chicago Style, don’t include a page number on your title page. The first page after the title page should be numbered starting at 2. [4] X Research source

- In APA format, a running heading may be required in the left-hand header. This is a maximum of 50 characters that’s the full or abbreviated version of your essay’s title. [5] X Research source

- For APA formatting, place the title in bold at the center of the page 3 to 4 lines down from the top. Insert one double-spaced line under the title and type your name. Under your name, in separate centered lines, type out the name of your school, course, instructor, and assignment due date. [6] X Research source

- For Chicago Style, set your cursor ⅓ of the way down the page, then type your title. In the very center of your page, put your name. Move your cursor ⅔ down the page, then write your course number, followed by your instructor’s name and paper due date on separate, double-spaced lines. [7] X Trustworthy Source Purdue Online Writing Lab Trusted resource for writing and citation guidelines Go to source

- Double-space the heading like the rest of your paper.

Writing the Essay Body

- Use standard capitalization rules for your title.

- Do not underline, italicize, or put quotation marks around your title, unless you include other titles of referred texts.

- A good hook might include a quote, statistic, or rhetorical question.

- For example, you might write, “Every day in the United States, accidents caused by distracted drivers kill 9 people and injure more than 1,000 others.”

- "Action must be taken to reduce accidents caused by distracted driving, including enacting laws against texting while driving, educating the public about the risks, and giving strong punishments to offenders."

- "Although passing and enforcing new laws can be challenging, the best way to reduce accidents caused by distracted driving is to enact a law against texting, educate the public about the new law, and levy strong penalties."

- Use transitions between paragraphs so your paper flows well. For example, say, “In addition to,” “Similarly,” or “On the other hand.” [12] X Research source

- A statement of impact might be, "Every day that distracted driving goes unaddressed, another 9 families must plan a funeral."

- A call to action might read, “Fewer distracted driving accidents are possible, but only if every driver keeps their focus on the road.”

Using References

- In MLA format, citations should include the author’s last name and the page number where you found the information. If the author's name appears in the sentence, use just the page number. [14] X Trustworthy Source Purdue Online Writing Lab Trusted resource for writing and citation guidelines Go to source

- For APA format, include the author’s last name and the publication year. If the author’s name appears in the sentence, use just the year. [15] X Trustworthy Source Purdue Online Writing Lab Trusted resource for writing and citation guidelines Go to source

- If you don’t use parenthetical or internal citations, your instructor may accuse you of plagiarizing.

- At the bottom of the page, include the source’s information from your bibliography page next to the footnote number. [16] X Trustworthy Source Purdue Online Writing Lab Trusted resource for writing and citation guidelines Go to source

- Each footnote should be numbered consecutively.

- If you’re using MLA format , this page will be titled “Works Cited.”

- In APA and Chicago Style, title the page “References.”

- If you have more than one work from the same author, list alphabetically following the title name for MLA and by earliest to latest publication year for APA and Chicago Style.

- Double-space the references page like the rest of your paper.

- Use a hanging indent of 0.5 inches (1.3 cm) if your citations are longer than one line. Press Tab to indent any lines after the first. [17] X Research source

- Citations should include (when applicable) the author(s)’s name(s), title of the work, publication date and/or year, and page numbers.

- Sites like Grammarly , EasyBib , and MyBib can help generate citations if you get stuck.

Formatting Resources

Expert Q&A

You might also like.

- ↑ https://www.une.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/392149/WE_Formatting-your-essay.pdf

- ↑ https://content.nroc.org/DevelopmentalEnglish/unit10/Foundations/formatting-a-college-essay-mla-style.html

- ↑ https://camosun.libguides.com/Chicago-17thEd/titlePage

- ↑ https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-guidelines/paper-format/page-header

- ↑ https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-guidelines/paper-format/title-page

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/chicago_manual_17th_edition/cmos_formatting_and_style_guide/general_format.html

- ↑ https://www.uvu.edu/writingcenter/docs/handouts/writing_process/basicessayformat.pdf

- ↑ https://www.deanza.edu/faculty/cruzmayra/basicessayformat.pdf

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/mla_style/mla_formatting_and_style_guide/mla_in_text_citations_the_basics.html

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/apa_style/apa_formatting_and_style_guide/in_text_citations_the_basics.html

- ↑ https://library.menloschool.org/chicago

About This Article

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Maansi Richard

May 8, 2019

Did this article help you?

Jan 7, 2020

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Develop the tech skills you need for work and life

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, the complete ib extended essay guide: examples, topics, and ideas.

International Baccalaureate (IB)

IB students around the globe fear writing the Extended Essay, but it doesn't have to be a source of stress! In this article, I'll get you excited about writing your Extended Essay and provide you with the resources you need to get an A on it.

If you're reading this article, I'm going to assume you're an IB student getting ready to write your Extended Essay. If you're looking at this as a potential future IB student, I recommend reading our introductory IB articles first, including our guide to what the IB program is and our full coverage of the IB curriculum .

IB Extended Essay: Why Should You Trust My Advice?

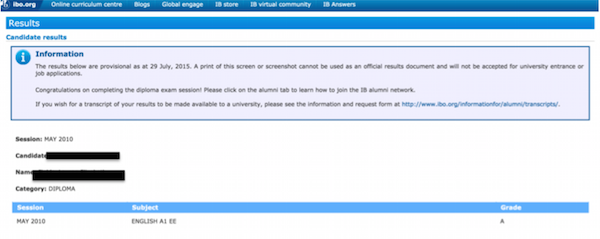

I myself am a recipient of an IB Diploma, and I happened to receive an A on my IB Extended Essay. Don't believe me? The proof is in the IBO pudding:

If you're confused by what this report means, EE is short for Extended Essay , and English A1 is the subject that my Extended Essay topic coordinated with. In layman's terms, my IB Diploma was graded in May 2010, I wrote my Extended Essay in the English A1 category, and I received an A grade on it.

What Is the Extended Essay in the IB Diploma Programme?

The IB Extended Essay, or EE , is a mini-thesis you write under the supervision of an IB advisor (an IB teacher at your school), which counts toward your IB Diploma (learn more about the major IB Diploma requirements in our guide) . I will explain exactly how the EE affects your Diploma later in this article.

For the Extended Essay, you will choose a research question as a topic, conduct the research independently, then write an essay on your findings . The essay itself is a long one—although there's a cap of 4,000 words, most successful essays get very close to this limit.

Keep in mind that the IB requires this essay to be a "formal piece of academic writing," meaning you'll have to do outside research and cite additional sources.

The IB Extended Essay must include the following:

- A title page

- Contents page

- Introduction

- Body of the essay

- References and bibliography

Additionally, your research topic must fall into one of the six approved DP categories , or IB subject groups, which are as follows:

- Group 1: Studies in Language and Literature

- Group 2: Language Acquisition

- Group 3: Individuals and Societies

- Group 4: Sciences

- Group 5: Mathematics

- Group 6: The Arts

Once you figure out your category and have identified a potential research topic, it's time to pick your advisor, who is normally an IB teacher at your school (though you can also find one online ). This person will help direct your research, and they'll conduct the reflection sessions you'll have to do as part of your Extended Essay.

As of 2018, the IB requires a "reflection process" as part of your EE supervision process. To fulfill this requirement, you have to meet at least three times with your supervisor in what the IB calls "reflection sessions." These meetings are not only mandatory but are also part of the formal assessment of the EE and your research methods.

According to the IB, the purpose of these meetings is to "provide an opportunity for students to reflect on their engagement with the research process." Basically, these meetings give your supervisor the opportunity to offer feedback, push you to think differently, and encourage you to evaluate your research process.

The final reflection session is called the viva voce, and it's a short 10- to 15-minute interview between you and your advisor. This happens at the very end of the EE process, and it's designed to help your advisor write their report, which factors into your EE grade.

Here are the topics covered in your viva voce :

- A check on plagiarism and malpractice

- Your reflection on your project's successes and difficulties

- Your reflection on what you've learned during the EE process

Your completed Extended Essay, along with your supervisor's report, will then be sent to the IB to be graded. We'll cover the assessment criteria in just a moment.

We'll help you learn how to have those "lightbulb" moments...even on test day!

What Should You Write About in Your IB Extended Essay?

You can technically write about anything, so long as it falls within one of the approved categories listed above.

It's best to choose a topic that matches one of the IB courses , (such as Theatre, Film, Spanish, French, Math, Biology, etc.), which shouldn't be difficult because there are so many class subjects.

Here is a range of sample topics with the attached extended essay:

- Biology: The Effect of Age and Gender on the Photoreceptor Cells in the Human Retina

- Chemistry: How Does Reflux Time Affect the Yield and Purity of Ethyl Aminobenzoate (Benzocaine), and How Effective is Recrystallisation as a Purification Technique for This Compound?

- English: An Exploration of Jane Austen's Use of the Outdoors in Emma

- Geography: The Effect of Location on the Educational Attainment of Indigenous Secondary Students in Queensland, Australia

- Math: Alhazen's Billiard Problem

- Visual Arts: Can Luc Tuymans Be Classified as a Political Painter?

You can see from how varied the topics are that you have a lot of freedom when it comes to picking a topic . So how do you pick when the options are limitless?

How to Write a Stellar IB Extended Essay: 6 Essential Tips

Below are six key tips to keep in mind as you work on your Extended Essay for the IB DP. Follow these and you're sure to get an A!

#1: Write About Something You Enjoy

You can't expect to write a compelling essay if you're not a fan of the topic on which you're writing. For example, I just love British theatre and ended up writing my Extended Essay on a revolution in post-WWII British theatre. (Yes, I'm definitely a #TheatreNerd.)

I really encourage anyone who pursues an IB Diploma to take the Extended Essay seriously. I was fortunate enough to receive a full-tuition merit scholarship to USC's School of Dramatic Arts program. In my interview for the scholarship, I spoke passionately about my Extended Essay; thus, I genuinely think my Extended Essay helped me get my scholarship.

But how do you find a topic you're passionate about? Start by thinking about which classes you enjoy the most and why . Do you like math classes because you like to solve problems? Or do you enjoy English because you like to analyze literary texts?

Keep in mind that there's no right or wrong answer when it comes to choosing your Extended Essay topic. You're not more likely to get high marks because you're writing about science, just like you're not doomed to failure because you've chosen to tackle the social sciences. The quality of what you produce—not the field you choose to research within—will determine your grade.

Once you've figured out your category, you should brainstorm more specific topics by putting pen to paper . What was your favorite chapter you learned in that class? Was it astrophysics or mechanics? What did you like about that specific chapter? Is there something you want to learn more about? I recommend spending a few hours on this type of brainstorming.

One last note: if you're truly stumped on what to research, pick a topic that will help you in your future major or career . That way you can use your Extended Essay as a talking point in your college essays (and it will prepare you for your studies to come too!).

#2: Select a Topic That Is Neither Too Broad nor Too Narrow

There's a fine line between broad and narrow. You need to write about something specific, but not so specific that you can't write 4,000 words on it.

You can't write about WWII because that would be a book's worth of material. You also don't want to write about what type of soup prisoners of war received behind enemy lines, because you probably won’t be able to come up with 4,000 words of material about it. However, you could possibly write about how the conditions in German POW camps—and the rations provided—were directly affected by the Nazis' successes and failures on the front, including the use of captured factories and prison labor in Eastern Europe to increase production. WWII military history might be a little overdone, but you get my point.

If you're really stuck trying to pinpoint a not-too-broad-or-too-narrow topic, I suggest trying to brainstorm a topic that uses a comparison. Once you begin looking through the list of sample essays below, you'll notice that many use comparisons to formulate their main arguments.

I also used a comparison in my EE, contrasting Harold Pinter's Party Time with John Osborne's Look Back in Anger in order to show a transition in British theatre. Topics with comparisons of two to three plays, books, and so on tend to be the sweet spot. You can analyze each item and then compare them with one another after doing some in-depth analysis of each individually. The ways these items compare and contrast will end up forming the thesis of your essay!

When choosing a comparative topic, the key is that the comparison should be significant. I compared two plays to illustrate the transition in British theatre, but you could compare the ways different regional dialects affect people's job prospects or how different temperatures may or may not affect the mating patterns of lightning bugs. The point here is that comparisons not only help you limit your topic, but they also help you build your argument.

Comparisons are not the only way to get a grade-A EE, though. If after brainstorming, you pick a non-comparison-based topic and are still unsure whether your topic is too broad or narrow, spend about 30 minutes doing some basic research and see how much material is out there.

If there are more than 1,000 books, articles, or documentaries out there on that exact topic, it may be too broad. But if there are only two books that have any connection to your topic, it may be too narrow. If you're still unsure, ask your advisor—it's what they're there for! Speaking of advisors...

Don't get stuck with a narrow topic!

#3: Choose an Advisor Who Is Familiar With Your Topic

If you're not certain of who you would like to be your advisor, create a list of your top three choices. Next, write down the pros and cons of each possibility (I know this sounds tedious, but it really helps!).

For example, Mr. Green is my favorite teacher and we get along really well, but he teaches English. For my EE, I want to conduct an experiment that compares the efficiency of American electric cars with foreign electric cars.

I had Ms. White a year ago. She teaches physics and enjoyed having me in her class. Unlike Mr. Green, Ms. White could help me design my experiment.

Based on my topic and what I need from my advisor, Ms. White would be a better fit for me than would Mr. Green (even though I like him a lot).

The moral of my story is this: do not just ask your favorite teacher to be your advisor . They might be a hindrance to you if they teach another subject. For example, I would not recommend asking your biology teacher to guide you in writing an English literature-based EE.

There can, of course, be exceptions to this rule. If you have a teacher who's passionate and knowledgeable about your topic (as my English teacher was about my theatre topic), you could ask that instructor. Consider all your options before you do this. There was no theatre teacher at my high school, so I couldn't find a theatre-specific advisor, but I chose the next best thing.

Before you approach a teacher to serve as your advisor, check with your high school to see what requirements they have for this process. Some IB high schools require your IB Extended Essay advisor to sign an Agreement Form , for instance.

Make sure that you ask your IB coordinator whether there is any required paperwork to fill out. If your school needs a specific form signed, bring it with you when you ask your teacher to be your EE advisor.

#4: Pick an Advisor Who Will Push You to Be Your Best

Some teachers might just take on students because they have to and aren't very passionate about reading drafts, only giving you minimal feedback. Choose a teacher who will take the time to read several drafts of your essay and give you extensive notes. I would not have gotten my A without being pushed to make my Extended Essay draft better.

Ask a teacher that you have experience with through class or an extracurricular activity. Do not ask a teacher that you have absolutely no connection to. If a teacher already knows you, that means they already know your strengths and weaknesses, so they know what to look for, where you need to improve, and how to encourage your best work.

Also, don't forget that your supervisor's assessment is part of your overall EE score . If you're meeting with someone who pushes you to do better—and you actually take their advice—they'll have more impressive things to say about you than a supervisor who doesn't know you well and isn't heavily involved in your research process.

Be aware that the IB only allows advisors to make suggestions and give constructive criticism. Your teacher cannot actually help you write your EE. The IB recommends that the supervisor spends approximately two to three hours in total with the candidate discussing the EE.

#5: Make Sure Your Essay Has a Clear Structure and Flow

The IB likes structure. Your EE needs a clear introduction (which should be one to two double-spaced pages), research question/focus (i.e., what you're investigating), a body, and a conclusion (about one double-spaced page). An essay with unclear organization will be graded poorly.

The body of your EE should make up the bulk of the essay. It should be about eight to 18 pages long (again, depending on your topic). Your body can be split into multiple parts. For example, if you were doing a comparison, you might have one third of your body as Novel A Analysis, another third as Novel B Analysis, and the final third as your comparison of Novels A and B.

If you're conducting an experiment or analyzing data, such as in this EE , your EE body should have a clear structure that aligns with the scientific method ; you should state the research question, discuss your method, present the data, analyze the data, explain any uncertainties, and draw a conclusion and/or evaluate the success of the experiment.

#6: Start Writing Sooner Rather Than Later!

You will not be able to crank out a 4,000-word essay in just a week and get an A on it. You'll be reading many, many articles (and, depending on your topic, possibly books and plays as well!). As such, it's imperative that you start your research as soon as possible.

Each school has a slightly different deadline for the Extended Essay. Some schools want them as soon as November of your senior year; others will take them as late as February. Your school will tell you what your deadline is. If they haven't mentioned it by February of your junior year, ask your IB coordinator about it.

Some high schools will provide you with a timeline of when you need to come up with a topic, when you need to meet with your advisor, and when certain drafts are due. Not all schools do this. Ask your IB coordinator if you are unsure whether you are on a specific timeline.

Below is my recommended EE timeline. While it's earlier than most schools, it'll save you a ton of heartache (trust me, I remember how hard this process was!):

- January/February of Junior Year: Come up with your final research topic (or at least your top three options).

- February of Junior Year: Approach a teacher about being your EE advisor. If they decline, keep asking others until you find one. See my notes above on how to pick an EE advisor.

- April/May of Junior Year: Submit an outline of your EE and a bibliography of potential research sources (I recommend at least seven to 10) to your EE advisor. Meet with your EE advisor to discuss your outline.

- Summer Between Junior and Senior Year: Complete your first full draft over the summer between your junior and senior year. I know, I know—no one wants to work during the summer, but trust me—this will save you so much stress come fall when you are busy with college applications and other internal assessments for your IB classes. You will want to have this first full draft done because you will want to complete a couple of draft cycles as you likely won't be able to get everything you want to say into 4,000 articulate words on the first attempt. Try to get this first draft into the best possible shape so you don't have to work on too many revisions during the school year on top of your homework, college applications, and extracurriculars.

- August/September of Senior Year: Turn in your first draft of your EE to your advisor and receive feedback. Work on incorporating their feedback into your essay. If they have a lot of suggestions for improvement, ask if they will read one more draft before the final draft.

- September/October of Senior Year: Submit the second draft of your EE to your advisor (if necessary) and look at their feedback. Work on creating the best possible final draft.

- November-February of Senior Year: Schedule your viva voce. Submit two copies of your final draft to your school to be sent off to the IB. You likely will not get your grade until after you graduate.

Remember that in the middle of these milestones, you'll need to schedule two other reflection sessions with your advisor . (Your teachers will actually take notes on these sessions on a form like this one , which then gets submitted to the IB.)

I recommend doing them when you get feedback on your drafts, but these meetings will ultimately be up to your supervisor. Just don't forget to do them!

The early bird DOES get the worm!

How Is the IB Extended Essay Graded?

Extended Essays are graded by examiners appointed by the IB on a scale of 0 to 34 . You'll be graded on five criteria, each with its own set of points. You can learn more about how EE scoring works by reading the IB guide to extended essays .

- Criterion A: Focus and Method (6 points maximum)

- Criterion B: Knowledge and Understanding (6 points maximum)

- Criterion C: Critical Thinking (12 points maximum)

- Criterion D: Presentation (4 points maximum)

- Criterion E: Engagement (6 points maximum)

How well you do on each of these criteria will determine the final letter grade you get for your EE. You must earn at least a D to be eligible to receive your IB Diploma.

Although each criterion has a point value, the IB explicitly states that graders are not converting point totals into grades; instead, they're using qualitative grade descriptors to determine the final grade of your Extended Essay . Grade descriptors are on pages 102-103 of this document .

Here's a rough estimate of how these different point values translate to letter grades based on previous scoring methods for the EE. This is just an estimate —you should read and understand the grade descriptors so you know exactly what the scorers are looking for.

Here is the breakdown of EE scores (from the May 2021 bulletin):

How Does the Extended Essay Grade Affect Your IB Diploma?

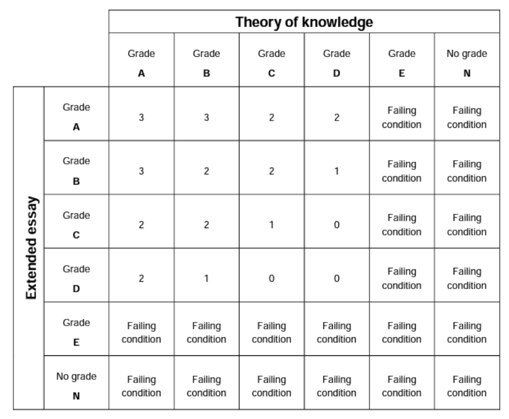

The Extended Essay grade is combined with your TOK (Theory of Knowledge) grade to determine how many points you get toward your IB Diploma.

To learn about Theory of Knowledge or how many points you need to receive an IB Diploma, read our complete guide to the IB program and our guide to the IB Diploma requirements .

This diagram shows how the two scores are combined to determine how many points you receive for your IB diploma (3 being the most, 0 being the least). In order to get your IB Diploma, you have to earn 24 points across both categories (the TOK and EE). The highest score anyone can earn is 45 points.

Let's say you get an A on your EE and a B on TOK. You will get 3 points toward your Diploma. As of 2014, a student who scores an E on either the extended essay or TOK essay will not be eligible to receive an IB Diploma .

Prior to the class of 2010, a Diploma candidate could receive a failing grade in either the Extended Essay or Theory of Knowledge and still be awarded a Diploma, but this is no longer true.

Figuring out how you're assessed can be a little tricky. Luckily, the IB breaks everything down here in this document . (The assessment information begins on page 219.)

40+ Sample Extended Essays for the IB Diploma Programme

In case you want a little more guidance on how to get an A on your EE, here are over 40 excellent (grade A) sample extended essays for your reading pleasure. Essays are grouped by IB subject.

- Business Management 1

- Chemistry 1

- Chemistry 2

- Chemistry 3

- Chemistry 4

- Chemistry 5

- Chemistry 6

- Chemistry 7

- Computer Science 1

- Economics 1

- Design Technology 1

- Design Technology 2

- Environmental Systems and Societies 1

- Geography 1

- Geography 2

- Geography 3

- Geography 4

- Geography 5

- Geography 6

- Literature and Performance 1

- Mathematics 1

- Mathematics 2

- Mathematics 3

- Mathematics 4

- Mathematics 5

- Philosophy 1

- Philosophy 2

- Philosophy 3

- Philosophy 4

- Philosophy 5

- Psychology 1

- Psychology 2

- Psychology 3

- Psychology 4

- Psychology 5

- Social and Cultural Anthropology 1

- Social and Cultural Anthropology 2

- Social and Cultural Anthropology 3

- Sports, Exercise and Health Science 1

- Sports, Exercise and Health Science 2

- Visual Arts 1

- Visual Arts 2

- Visual Arts 3

- Visual Arts 4

- Visual Arts 5

- World Religion 1

- World Religion 2

- World Religion 3

What's Next?

Trying to figure out what extracurriculars you should do? Learn more about participating in the Science Olympiad , starting a club , doing volunteer work , and joining Student Government .

Studying for the SAT? Check out our expert study guide to the SAT . Taking the SAT in a month or so? Learn how to cram effectively for this important test .

Not sure where you want to go to college? Read our guide to finding your target school . Also, determine your target SAT score or target ACT score .

Want to improve your SAT score by 160 points or your ACT score by 4 points? We've written a guide for each test about the top 5 strategies you must be using to have a shot at improving your score. Download it for free now:

As an SAT/ACT tutor, Dora has guided many students to test prep success. She loves watching students succeed and is committed to helping you get there. Dora received a full-tuition merit based scholarship to University of Southern California. She graduated magna cum laude and scored in the 99th percentile on the ACT. She is also passionate about acting, writing, and photography.

Student and Parent Forum

Our new student and parent forum, at ExpertHub.PrepScholar.com , allow you to interact with your peers and the PrepScholar staff. See how other students and parents are navigating high school, college, and the college admissions process. Ask questions; get answers.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Format pengetikan diuraikan di Bab III Sistematika Karya Ilmiah serta pada lampiran, berikut contoh-contoh yang lengkap dan praktis untuk diikuti, termasuk jenis dan ukuran fon, spasi, jarak pengetikan, dan pias (margin). Perlu diingat bahwa yang dicontohkan di sini adalah format pengetikan dokumen final. Mahasiswa dapat menyiapkan naskah

Pedoman Penulisan Karya Ilmiah IPB. IPB Repository. IPB's Books. IPB Press. View Item.

Direktorat Administrasi Pendidikan Email : [email protected] Instagram : @ditap.ipb Gd. Andi Hakim Nasoetion Lt. 1 Kampus IPB Dramaga Jl. Raya Darmaga Kampus IPB Darmaga Bogor 16680 Jawa Barat, Indonesia Kode Pos: 16680

msp.ipb.ac.id is a webpage that provides a pdf file of guidelines for scientific paper writing, based on the standards of IPB University. The pdf file covers topics such as structure, format, citation, and reference of scientific papers. It also includes examples and tips for writing effectively and ethically. The pdf file is useful for students, researchers, and lecturers who want to write ...

Buku Pedoman Penulisan Karya Ilmiah (PPKI) Tugas Akhir Mahasiswa edisi ke-4. ini, merupakan revisi dari PPKI edisi sebelumnya, dan berisi panduan tentang penulisan. karya ilmiah tugas akhir mahasiswa IPB multistrata mulai dari vokasi, sarjana, magister, sampai doktor. Karya tugas akhir mahasiswa vokasi berupa laporan akhir yang berasal dari.

Format and Style. The manuscript should be typed with single spacing, single column and font size 12 on A4 paper not exceeding 20 pages and should be submitted using the online submission system at Online Submissison System. The title of a manuscript should be concise, descriptive and preferably not exceeding 15 words.

Nemoto HK, Kiritani K, Ono H. 1984. [Enhancement of the intrinsic rate of natural increase induced by the treatment of the diamondback moth (Plutella xylostella (L.)) with sublethal concentration of methomyl] [dalam bahasa Jepang]. Jap J Appl Entomol Zool. 28(3):150-155.

CSL IPB Panduan Penulisan Karya Ilmiah (PPKI) Panduan Pemakaian Mendeley dan Zotero Template TA program Doktor Template TA program Magister Template TA program Sarjana Template Powerpoint Dept. of Statistics Virtual Background: Statistika dan Sains Data, IPB University (1) Statistika dan Sains Data, IPB University (2) Kolokium Seminar Ujian Skripsi Ujian Tesis Form Pascasarjana Formulir ...

Biro Legislasi dan Pelayanan Hukum | JDIH IPB Bogor

Rumah Publikasi IPB merupakan layanan yang disediakan oleh Direktorat Kajian Strategis dan Reputasi Akademik (DKaSRA), IPB University dalam rangka meningkatkan jumlah dan mutu publikasi ilmiah yang dihasilkan oleh dosen, peneliti, dan mahasiswa IPB. Layanan Rumah Publikasi IPB terdiri atas: 1. Cek Grammar naskah (menggunakan Akun Grammarly berlanggan) Untuk layanan Grammarly dapat diakses ...

Form Pendaftaran. Berikut Panduan Penulisan Makalah Semianar dan Kolokium. Format Makalah Kolokium dan Seminar Dept ESL. Contoh Makalah Seminar. Berikut. Departemen Ekonomi Sumberdaya dan Lingkungan Fakultas Ekonomi dan Manajemen IPB University.

SMARTsets. Intelligence preparation of the battlefield (IPB) is the systematic process of analyzing the mission variables of enemy, terrain, weather, and civil considerations in an area of interest to determine their effect on operations. IPB allows commanders and staffs to take a holistic approach to analyzing the operational environment (OE).

Pada video ini berisi langkah-langkah untuk mendownload dan menggunakan template tugas akhir IPB Terbaru...#Template #Skripsi #Tesis #Disertasi #Terbaru #IPB

PENGUMUMAN. Menindak lanjuti dan memperkuat Surat Edaran No. 1484/I3.10/KM/2010 tanggal 10 Februari 2010 (terlampir), maka mulai tanggal 1 Oktober 2010 Sekolah Pascasarjana IPB tidak akan menerima lagi tesis atau disertasi yang tidak memenuhi syarat sebagai berikut ini: 1. Menulis ringkasan tesis dan disertasi tidak lebih dari tiga halaman.

Guna mendorong peningkatan kontribusi IPB dalam perumusan rekomendasi kebijakan di tingkat nasional maupun internasional, Direktorat Publikasi Ilmiah dan Informasi Strategis (DPIS) mengadakan program insentif penulisan Policy Brief. Program ini merupakan bagian dari upaya untuk menghasilkan dan meningkatkan produk science to policy interfacing yang lebih berkualitas.

Your paper must be easy to understand. Consider the readership of your chosen journal, bearing in mind the knowledge expected of that audience. You should introduce any ideas that may be unfamiliar to your readers early in the paper so that your results can be easily understood. Your paper must be written in correct English.

Formatting an essay may not be as interesting as choosing a topic to write about or carefully crafting elegant sentences, but it's an extremely important part of creating a high-quality paper. In this article, we'll explain essay formatting rules for three of the most popular essay styles: MLA, APA, and Chicago.

This essay begins by discussing the situation of blind people in nineteenth-century Europe. It then describes the invention of Braille and the gradual process of its acceptance within blind education. Subsequently, it explores the wide-ranging effects of this invention on blind people's social and cultural lives.

Authors must prepare their papers using our Microsoft Word or LaTeX2e templates, and then convert these to PDF format for submission: Microsoft Word templates; LaTeX2e class file; Multimedia. If you would like to submit multimedia to accompany your paper, you might find these guidelines useful: Multimedia guidelines

If your instructor lets you pick the format of your essay, opt for the style that matches your course or degree best: MLA is best for English and humanities; APA is typically for education, psychology, and sciences; Chicago Style is common for business, history, and fine arts. 2. Set your margins to 1 inch (2.5 cm) for all style guides.

FORMAT ESAI 1. Esai ditulis dengan huruf Times New Roman 12, spasi 1,5. 2. Esai ditulis dalam 500—1.000 kata. 3. Esai mencakup gambaran isu terkini terkait dunia sastra serta sumbang saran dan pandangan tentang pengembangan dan pembinaan sastra di Indonesia sesuai dengan subtema Munsi III. 4. Esai dilengkapi bagian daftar rujukan (apabila ada ...

References and bibliography. Additionally, your research topic must fall into one of the six approved DP categories, or IB subject groups, which are as follows: Group 1: Studies in Language and Literature. Group 2: Language Acquisition. Group 3: Individuals and Societies. Group 4: Sciences. Group 5: Mathematics.

CLICK HERE to review the Certified Technician Program requirements. Ticket sales open at least 3 weeks prior to the exam date and close the week prior to the exam on Monday. All 6 CTP exams are offered at each exam session in Electronic format. Electronic Manual w/ Electronic Exam ticket - a PDF CTP manual is provided to the registrant for use during the exam. The registrant's self-provided ...