Search form

- பயிற்சியைக் கண்டு பிடியுங்கள்

- மையத்தைக் கண்டு பிடியுங்கள்

பெண்களுக்கு அதிகாரமளித்தல் (Women empowerment in tamil)

ஒவ்வொரு நாளும் பல்வேறு விதமான பங்குகளை முயற்சியின்றி ஏற்று வாழும் பெண்கள் எந்த சமுதாயத்திலும் சற்றும் சந்தேகமின்றி சமுதாயத்தின் முதுகெலும்பாகவே திகழ்கின்றனர். அருமையான மகள், அக்கறையான தாய் திறமையான சக பணியாளர் மற்றும் பல பங்குகளை நம்மைச் சுற்றி மகளிர் குறையின்றி நயம்பட வகித்து வருகின்றனர். ஆயினும் சமுதாயத்தில் அவர்கள் புறக்கணிக்கப் பட்ட பகுதியினராகவே உலகின் பல பகுதிகளிலும் இருந்து வருகின்றனர். பெரும்பாலும் சமத்துவமின்மை, அடக்குமுறை, பொருளாதார சார்பு மற்றும் பல சமூக கொடுமைகளுக்கு ஆளாகின்றனர்.பல நூற்றாண்டுகளாக பணித்துறையிலும் சொந்த வாழ்விலும் உயரங்களை எட்ட தடைகளுடனேயே மகளிர் வாழ்ந்து வருகின்றனர்.

மகளிர் சமுதாய மற்றும் பொருளாதார மேம்பாடு பெறச் செய்தல் |Empowering Women Socially and Economically

அவர்களுக்கு உரிமையான, மரியாதைக்குரிய நிலையினை மீட்டெடுத்து வரவும், அவர்களது உள்மன வலிமை, படைப்பாற்றல், சுய மதிப்பு அனைத் தையும் அளிக்கும் வகையில் வாழும்கலை மகளிர் மேம்பாட்டுத் திட்டங் களை முன்னெடுத்து வந்திருக்கின்றது.

இந்த அடிப்படை நன்கு கட்டமைக்கப் பட்ட நிலையில், மகளிர் எந்த சவாலையும் திறன்கள் நம்பிக்கை மற்றும் நளினத்துடன் ஏற்றுக் கையாளத் தயாராகி விட்டனர்.அவர்கள் முன்னிலைக்கு வந்து தங்களுக்கு, தங்கள் குடும்பத்திற்கு பிற மகளிருக்கு மற்றும் சமுதாயத்திற்கு நேர்மறையான மாற்றம் எடுத்து வரும் சமாதானத் தூதுவர்களாகவும் ஆகி விட்டனர்.

வாழும் கலை மேற்கொண்டிருக்கும் ஆறு மகளிர் மேம்பாட்டுத் திட்டங்கள் | 6 Women Empowerment programs taken up by The Art of Living

- பொருளாதார சுதந்திரம்

- பெண் குழந்தைக்கு கல்வி

- ஹெச் ஐ வி மற்றும் எய்ட்ஸ்

- சிறைப் பயிற்சித் திட்டம்

- தலைமைத்துவம்

- சமுதாய அதிகாரம்

ஊக்குவிக்கும் மகளிர் மேம்பாட்டுக் கதைகள்

குண்டூர் ஸ்ரீ ஸ்ரீ சேவா மந்திருக்கு மூன்று பெண்கள் வந்தனர். அவர்கள் மனதில் ஆழமான காயங்களடங்கிய கடந்த காலப் பதிவுகள் இருந்தன. அன்னையின் கவனமான மற்றும் அன்பு நிறைந்த வழிகாட்டுதலில் ஜோதி, தத்வமஸி மற்றும் ஸ்ரவாணி ஆகிய மூன்று பெண்களும் இப்போது அழிக்க முடியாத ஆனந்த வாழ்க்கையினை உற்சாகத்துடன் வாழ்ந்து வருகின்றனர்.

கல்வி மூலம் மகளிருக்கு அதிகாரமளித்தல் | Women Empowerment through education

வாழ்க்கையில் முன்னேற கல்வி முக்கியமான கருவியாகும். மகளிரை மேம்படச் செய்து அதிகாரமளிக்க கல்வியை விட வேறென்ன சிறந்த வழி யுள்ளது? வாழும் கலை தனது பல்வேறு முயற்சிகளின் மூலம் இளம் பெண்கள் மகளிர் ஆகியோருக்கு இந்தியாவின் ஒதுக்குப் புறமுள்ள கிராமங்களிலும் சிறந்த தரம் வாய்ந்த கல்வியை அளிக்கிறது.இதைப் பற்றி மேலும் அறிந்து கொள்ளுங்கள்.

இந்தியாவில் மகளிருக்கு அதிகாரமளிக்கும் பணித் திட்டங்கள் | Women Empowerment Programs in India

வாழும்கலையின் மகளிர் மேம்பாட்டுத் திட்டங்களின் மூலம் இதியாவில் மற்றும் பல நாடுகளில் மகளிர் பொருளாதார சுதந்திரம் அடைந்து சமூக அநீதியை எதிர்த்திருக்கின்றனர். அவர்கள் மாற்றங்களை எடுத்து வரும் முகவர்களுமாகி பிற மகளிருக்கு கல்வி, சுய அதிகாரம், சுயமாக தாங்களே தங்கள் வாழ்க்கையைக் கவனித்துக் கொள்ளுதல் ஆகியவற்றுக்குத் தயார் செய்கின்றனர்.

வாழும்கலையின் மகளிர் மேம்பாட்டுத் திட்டங்கள் பல நூற்றாண்டுகளாக இருந்து வரும் கட்டுப்பாடுகளைத் தகர்க்கும் ஊக்கியாக அமைந்து, மகளிருக்கு அவர்களுக்குரித்தான சுதந்திரம் மற்றும் சமஉரிமை ஆகியவற்றை அடையும் மேடையை அமைத்துக் கொடுத்திருக்கின்றன.

வெவ்வேறு திட்டங்களின் பற்றி மேலும் அறிய :

சுற்றுச் சூழல் பாதுகாப்பு (Environment protection in tamil)

கல்வி (Importance of education in tamil)

அமைதி (Peace in tamil)

எங்களது அதிகாரமளிக்கும் உருப் படிவம் (Youth Leadership Programs in tamil)

எங்களது முழுமையான அணுகுமுறை (Our Holistic Approach In tamil)

Panels, Politics, and Penn (Women) In The Land Of Tamil Nadu

A report by Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) and UN Women titled Women In Politics (2017) states, “As on October 2016, out of the total 4,118 MLAs across the country, only 9 per cent were women.” India ranks 151 th among the 190 countries and 5 th among the 8 South-Asian countries.

Equality in Politics – A Survey of Women and Men in Parliaments explains various aspects relating to women’s political representation and parliamentary governance. Overall disparities follow the same trend with the lack of confidence and finance being the major deterrent that prevented women from entering politics. These stats along with the recently released ‘manel’ report by the Network of Women in Medi a (NWMI) 2019 sheds light on the ingrained prejudice against women within the Indian news media.

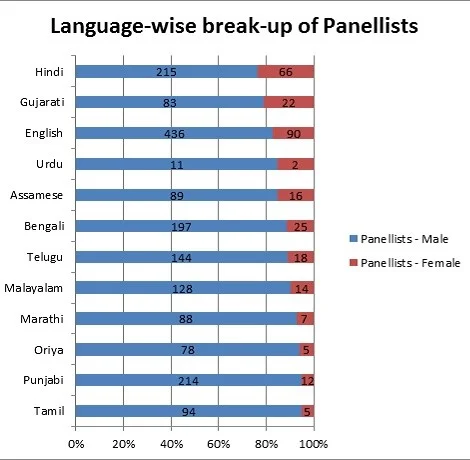

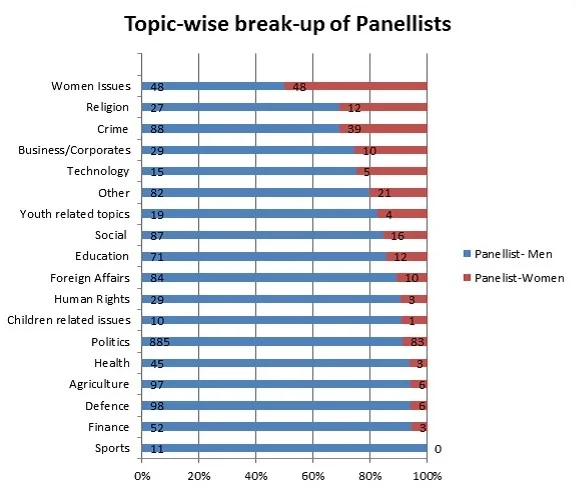

Panel discussions occupy prime time viewership in the TV news universe, irrespective of the language. The manel report extensively described the biased pattern in prime-time debate shows. While the outright ‘gender imbalance’ was sort of given, one statistic in the report was surprising. It states that the representation of women in prime-time panels was 5% in Tamil and Punjabi channels – the lowest average among the states.

With better literacy, health and other human development indices, the state of Tamil Nadu has often revelled in the numbers that made it a ‘class apart’ within the country. The low score is telling of the accepted model of toxic masculinity and cultural patriarchy, that encompasses Tamil society.

While the male-led leadership fight amongst themselves, to claim the ‘true’ Tamil identity, women get the short end of the stick.

This media representation, however, explains the deeper hypocrisy that is imbibed in the Tamil society. Tamil pride has often been a merger of distinct linguistic and cultural identity. The yesteryear values based on ancient Tamil texts, glorify chastity, virginity, and a submissive female who happily lays down independence for the family or her man’s wishes.

Also read: Women and Politics: Women Voters Are Higher Than Men But Why Is Female Representation In Politics Still Low

Simply put, the ideal Tamil female is the virtue of chastity and the Tamil man, an epitome of virility. The proponents of this identity beginning with the speakers of Dravidian movement to many of the modern-day political stalwarts stick to this image adherently. This so-called ‘Tamil’ identity has sexist undertones, “middle-class morality” which are often glorified to forge a partnership among the common people.

In Tamil Nadu, feminism is often angled with the words of two very distinct personalities, the poet Subramanian Bharati, and Periyar (the founder of Dravian Kazhagam ). The two men are often identified as radical feminist thinkers who articulated thoughts that has shaped feminist thinking in the state. Additionally, the angle of caste forged by the self-respect movement as a common cause for unity has splintered parties along the same lines it sought to diminish. While their commendable efforts have survived, it’s a sad reality that their values have not. They have simply become a poster for others to claim one thing – the women’s vote.

According to the election commission report, in 2016, more women turned up to vote when compared to men. While the vote matters, women as leaders, candidates do not get the encouragement or support. This is in line with the superficial streak of female empowerment practised by regional politics.

- In the last state assembly elections in 2016, the AIADMK and CPI(M) fielded 12% and DMK, 10%. The Congress fielded three of the 41 candidates (7%) the party.

- Women MLAs accounted for 3% to 10% of the Tamil Nadu state Assembly.

Stage culture of Tamil oratory can be an empowering platform for aspiring female leaders but ‘a handful representation’ of female speakers are pigeonholed to score political points. The point of female empowerment or representation gets lost in the wider politics between the parties. This spills into the outrage drama that follows shouting-matches linked to ‘controversial’ statements.

While this passes for prime-time journalism, diversity and representation in these panels are more than often absent. In between film trailers and other product placements, the debate is usually carried on by the same set of women, handpicked by the channels for their political leanings. While representation by women in various issues lack numbers, a handful representing the whole of the state is an acknowledgement of this gender bias.

The whole concept of language bonded nationalism has been the cornerstone of Dravidian politics. While the male-led leadership fight amongst themselves, to claim the ‘true’ T amil identity, women get the short end of the stick.

The state has long had an authoritarian female leadership by the late CM Jayalalitha. As a head of a Dravidian party, unapologetic of her caste, religion, she had a distinctive governance style. Absolute subservience with her central authority was ubiquitous throughout her tenure. This level of internalised patriarchy is common in the toxic world of Tamil Nadu’s politics.

Also read: Dalit Women in Media and Politics Conference: When #DalitWomenSpeakOut, Revolution Beckons

Though the state has very good indicators with regard to literacy, women still face challenges because of the patriarchal mindset that pervades daily life in Tamil Nadu.

- Total literacy rate in Tamil Nadu has shown an increasing trend over the years, increasing from 62.66% in 1991 to 80.33% in 2011.

- 14 districts have female literacy rates above the State average that is, above 73.86%.

Women leaders of the state have in the recent years have only been meme topics and insults on-stage by politicians. Even insults hurled between men on-stage bear references to their mothers, often demeaning them. This downgrade in stage decorum is a far cry from the flowing Tamil language used to garner public support for the party, during earlier times. This also goes hand in hand with that way political parties slowly ease out women from active participation.

Only 5% of the professional and independent analysts featured on panels were women

Politics has become a man’s domain and women mostly get typecast as symbols for virtue, chastity or as whores. The latter word had caused quite a stir in the state earlier last year, when nuanced argument ceased and war of words flowed defending the chastity of a goddess. This added leverage in the #Metoo debates that followed, as well. While the caste angle was apparent, since its Tamil Nadu, there was a strange backlash and role reversal. During the same time, the murder of a Dalit woman did not garner this support but remained an isolated issue to be handled solely by Dalit activists. This caste schism affects women, and issues of real concern get buried in the 24-hour news cycle.

While systemic patriarchy and caste deter women as political candidates, grassroots are an active platform to inculcate female leadership. In this intrusive social media age and the social reality of “ TV culture is Tamil culture ”, media can be effective to provide role-models.

Gender bias, in the panel discussions, the conspicuous absence of women’s point of view, and the lack of diversity among the women represented are serious causes for concern. The explicit lack of role-models, female leadership continues to manifest as an ineffective debate of issues.

Only 5% of the professional and independent analysts featured on panels were women; the corresponding figures for party spokespersons and subject experts were 8% and 11% respectively. Politics dominate these prime-time debates and by extension our daily lives. On the other hand, in discussions on politics, which constituted nearly half (45%) of all panel discussions on news television, only 8% of the panellists were women.

In a 2015 survey on media and gender in India by the International Federation of Journalists (focusing primarily on patterns of employment and working conditions), only 6.34% of the respondents felt that women were shown as ‘experts/leaders’ in the news. A miniscule 2.17% thought women were depicted as ‘equal citizens’. In contrast, many more respondents said women were generally depicted as ‘victims’, ‘sexual objects’, ‘family figures’ or ‘negative’ stereotypes.

The early gains of the Dravidian party and the popularity of the Congress-old guard in the state was mainly due to active women participation. The shelving of female participation and leadership is not the true essence of democracy. Media shapes the way we think, and when we don’t see representation and assume it is okay, the consequence is a broken democratic setup.

1. Equality in Politics: A Survey of Women and Men in Parliaments 2. Panels or Manels ? The Network of Women in Media, India, February 2019 3. Election Commission Of India reports for Tamil Nadu assembly elections 1996 , 2001 , 2006 , 2011 and 2016 4. Tamil Nadu Human Development 2017

Featured Image Source: Livemint

A homemaker trying to wedge feminism into daily life. Ambica enjoys reading and is a news junkie. She loves political satire, especially by female comedians. Her other interests are films and plays.

Related Posts

Bulldozer Injustice: State Violence In The Garb Of Addressing ‘Illegal Encroachments’

By Akshita Prasad

From Leaders To Abusers: Yediyurappa’s Case And BJP’s Troubling Legacy

By Sohini Sengupta

The Prosecution Of Arundhati Roy Under UAPA: Intertwining Legal, Political And Human Rights Dimensions

By Atika Sayeed

"> img('logo-tagline', [ 'class'=>'full', 'alt'=>'Words Without Borders Logo' ]); ?> -->

- Get Started

- About WWB Campus

- Translationship: Examining the Creative Process Between Authors & Translators

- Ottaway Award

- In the News

- Submissions

Outdated Browser

For the best experience using our website, we recommend upgrading your browser to a newer version or switching to a supported browser.

More Information

The Poetry of Radical Female Fighters

Meena kandasamy on translating women from the tamil eelam.

Chennai-born Meena Kandasamy is an award-winning novelist and poet, best known for her book When I Hit You . She started translating at the age of eighteen and has worked on speeches and writings by activist and politician Thol. Thirumavalavan, writer Salma, Tamil Eelam poets, and many more. Her work is an active resistance against gender- and caste-based violence, and she describes her writing process as taking things that “rattle her” and “smuggling them into English.” Much of her recent focus has been on dismantling Hindutva, the hard-line right-wing rule of the Bharatiya Janta Party in India.

Her work as an activist has made her no stranger to trolls and threats. In her latest book-length essay, The Orders Were to Rape You , she writes about growing up during the Sri Lankan Civil War, which lasted from 1983 to 2009 and involved the violent persecution of Sri Lankan Tamils, including many state-supported anti-Tamil pogroms, the designation of Sinhala as the sole official language of the state, and the unreported rape, torture, and disappearance of Tamils. More specifically, Kandasamy remembers life in Tamil Nadu when the Indian Peacekeeping Force (IPKF) was still occupying Tamil Eelam, a proposed independent state for Tamils in Sri Lanka. It was during this time that she saw women from Tamil Eelam fighting back, “donning combat gear and taking up AK-47s” as part of the guerrilla independence movement known as the Liberation Tigers. Inspired by these women, Kandasamy participated in demonstrations to support the movement for Tamil Eelam, and started translating news reports and articles to give their struggle a wider readership.

The Orders Were to Rape You also documents Kandasamy’s experience, as an adult, meeting women fighters from the Liberation Tigers in the aftermath of the brutal war. The women she spoke to lived as refugees in Southeast Asian countries where the threat of war still lurked in their everyday lives. Kandasamy ends the book with her own translations of work by three female Tamil combatant poets. These poems also appeared in Guernica ’s Female Fighters Series.

In this interview, conducted via email, Kandasamy discusses the stakes of translation, decolonization, and the process of writing a long-form first-person essay about women and their experience confronting war.

—Suhasini Patni

Suhasini Patni (SP): The Orders Were to Rape You was originally conceived as a documentary film. Why did you change your approach, and what was the process of converting the documentary scraps into a book? Did you have any struggles?

Meena Kandasamy (MK): At some point, I had to come to terms with the fact that this project wouldn’t become a documentary. Like all writers who cannot let go of their projects, I lived in denial for a long time—there was this feverish urge to make the world see and hear this story, and then there was something I wasn’t used to: the task of mobilizing a diverse group of people, mobilizing funding, and finding a producer/backer who could make sure that this material was communicated in the best way and reached the best audience. It is not that people were not ready—everyone was moved by the story—but they were also aware that just invoking the word “terrorism” would bury this work. Although the project was about female insurgents fighting for the liberation of their homeland and about the consequences they faced after the war, we knew how easily it could be termed illegal. Once a certain amount of money is invested, no one wants to take risks. By the end of 2013, the raw footage was all there. For four, five years, I kept chasing it, trying to see if I could make it materialize. In 2018, I decided that I had to write it down. This way it would be completely within my control; I was not going to be dependent on others. If there were consequences, I would face them single-handedly.

At first it was a process of unlearning. In trying to make a documentary, I was learning how to not think and work and perform like a writer. Film was a different medium, a different genre, a different beast altogether. I had to first learn the basics, and then the intricacies, of the medium of film. It is another language, another grammar—and one has to teach oneself to think differently, do differently.

And then, fortunately, or unfortunately, after a period of five years, I realized that the only way to get the story out was within the framework of nonfiction, the long-form narrative lyric essay—whatever you choose to call it. And this was unwieldy. This was a story that I had shot visually, a story that did not include me at all. When I began to write it down, it required that I tell the meta-story of how and why I came to be in the story. That self-awareness became an integral part of the project. I felt a little uncomfortable in the beginning, because all these years, I’ve never embraced the first-person essay. It always felt too individualistic, too self-absorbed. To transform that, to show how political events shape individual lives, to dissect the “I” mercilessly became imperative for me.

SP: In The Orders Were to Rape You, you talk about why you initially wanted to make this project a documentary: “I wanted my subjects to have autonomy, I wanted them to speak for themselves. I did not want their words coming out filtered through a writer’s pen.” How do you feel about this now that the book has been published?

MK: Yes, that was the initial aim, as I mentioned in the book. I tried to keep that aim intact even when I wrote it out as a book-length essay, hence the strange format—there’s no reported speech at all. Their interviews are transcribed almost breathlessly, without, as I said, the filter of the writer’s pen.

I am happy to have made that decision. It is not an approach that always works, but in this instance, because of the harrowing stories the interviewees share, it was only right that they hold the floor.

SP: As you mention in the book, this was not your first time translating Tamil Eelam poets. What was the process of translating them like when you were younger and had less experience with translation? Is the process any different now?

MK: When I translated the Tamil Eelam poets in 2009, after the genocide, I had already published more than six books of Tamil-to-English translations, including the works of Dravidian ideologue Periyar, the writings of Tamil leader Thol. Thirumavalavan, and the poetry and fables of Tamil Eelam poet Kasi Anandan. So I had been working for years already before I embarked on translating poets like Cheran Rudramoorthy and VIS Jayapalan. That said, when I translated Captain Vaanathi and Captain Kasthuri in 2019 for the purposes of my piece in Guernica , which was commissioned by Dr. Nimmi Gowrinathan as part of the Female Fighters Series, I had been translating for seventeen years. I wish I could say it gets easier, but it doesn’t. I don’t want to lie. I’d say that on the contrary, having translated a lot means that one should still be very careful, not be lazy, not allow the pride of experience to get into one’s head. Every work is different, there is so much nuance where poetry is concerned, and everyone also needs their own individual signature style in the target language—they should not sound like you. It is a lot of work.

SP: What’s particularly interesting to me is that you also tell your own story alongside the Tamil Eelam struggle. It reminded me a little of Exquisite Cadavers , your earlier novel, where you choose to split the page in half—one side is the story and the other side is what’s going on in your head as you write it. But in that book, there was a sharp physical divide on the page. Here you intersperse your own thoughts and life with that of the poetry and documentation. Can you talk about how you find a balance with such a narrative?

MK: Thank you for bringing this up. In a lot of my works of fiction I am trying to break down the fourth wall. Exquisite Cadavers was a clever and challenging experiment to pull off, and I think it went rather well. In The Orders Were to Rape You , it was not just about narrative balance. Documenting what Tamil women (those related to the Tamil Tigers and Tigresses) faced in the Manik Farm camps in the aftermath of the 2009 genocide was urgent. It had to be done—none of these women have gotten any kind of justice, many of them are still struggling to get asylum abroad, and back in Sri Lanka, the Rajapaksas are once more in power. 1 That is one of the important strands of the book.

The other important strand is how the Tamil Tigresses defined themselves—and to address this question, I was looking at the poetry of Captain Vanathi and Captain Kasturi, who were outspokenly feminist, anti-imperialist, and extremely critical of oppression (whether it was class-based or in the name of tradition). How did I locate myself within the book, the story of the story, so to speak? Or rather, why was I telling their story? I grew up in a family that was extremely supportive of the Tamil Eelam liberation struggle—the kind of people who unfailingly attended protest marches, courted arrest, and followed the everyday news. This support for Tamil Eelam was very much a landscape for many of us growing up in the 1980s and 1990s. In the years of the worst repression in Sri Lanka, much of the organizing simply moved to Tamil Nadu. So it pervaded our imaginations and many aspects of our lives here.

In absolute contrast to this, the Indian government was consistently acting against the interests of the Eelam Tamils. As an Indian Tamil woman, it became even more important for me to stand up against what my so-called nation was doing to perpetuate the occupation and settler-colonialism in Tamil Eelam. India’s role in Tamil Eelam is a story written in blood: rapes and massacres during the IPKF, consistent involvement against Tamil interests, tacit support of Sri Lanka during the genocide, and now corporate profiteering and disaster capitalism. Although it appears to be my story, I’m only a prism; I’m only telling the story of what India was doing.

SP: I’m sure you find similarities between your own poems and the ones you’ve translated for this book. I certainly saw connections between your poems in Ms Militancy and Captain Kasturi’s poems. Does the awareness of these similarities affect your translation process at all?

MK: I think the similarities are a result of the subject matter. In fact, I wish I had been exposed to the poetry of the female Tigers, or any other guerrilla poets, earlier in my life. I wrote all of Ms Militancy when I was a fellow of the International Writing Program at the University of Iowa. I was twenty-five; this was in 2009. Initially, I had wanted to write the novel that eventually became Gypsy Goddess , but once I was actually there I realized I just couldn’t do fiction. I couldn’t while away all this time that was paid for and so well-earned, and so I came up with a poetry project. A book of feminist poetry like Anne Sexton’s Transformations , like Carol Ann Duffy’s The World’s Wife . So, although my political outlook was hugely affected by the genocide that had just concluded on the island of Sri Lanka (there are at least two or three poems in Ms Militancy that deal with this war), my poetic impulses were influenced by the confessional poets I was reading at that time, including Kamala Das.

The similarities you speak about—I think they arose partly because this is a shared political journey, partly because of the Tamil tradition Captain Kasturi and I share, and partly because my work, like hers, deals with what it means to be a woman who is forced to confront violence. In fact, when I first read Captain Kasturi’s poems, I was envious. She was not sitting there and wondering if some critic would dismiss her work as propaganda poetry—she couldn’t care less! She wasn’t worried that an exhortation for the workers’ and oppressed people’s revolution would not be considered lyrical enough. When you do not operate within the literary establishment, when you can be forthright about your politics on the page, when you are not held back by any fear, you can write songs of liberation—that is how her poetry feels.

SP: You mention that when a senior Tigress you were interviewing was dying of cancer, the people around her asked if you had links to any white documentary filmmaker, because whiteness is “an automatic stamp of neutrality, balance, sound political judgment.” Instead, you write that you wanted to tell the story on your terms, and the terms of the women whose story you’re telling. What is this process like? I’m thinking particularly about the chapbook you edited and co-translated for Tilted Axis, Desires Become Demons . That chapbook was a part of a “wider project of decolonization through and of translation, and in response to seeing women authors of color misread through a white feminist lens.” Do you see this book as an expansion of your project to reimagine the possibilities of intersectional feminism?

MK: White people often take it very personally if we even mention the phrase “white people.” But that kind of racial hegemony is undeniable, and stating it bears no malice against those who happen to be white. The built-in assumption that the white person is unbiased, neutral, fair; that a white person narrating a story carries more authority than a brown person who was actually involved as a witness telling the same story in the same language—these are not the opinions of white people alone. Such thoughts permeate each and every section of our society, and it becomes very important to counter them regardless of their source.

Tilted Axis is doing marvelous work. I’d work for them if they ever had a job opening because I love their vision of translation, of feminism, of women’s writing. It is revolutionary. In this chapbook Desires Become Demons , we take the word feminism and translate what it means to four activist women poets in Tamil Nadu. And it is amazing how differently they define feminism, how for so many of them, feminism is a project against caste oppression as well. And it is important to situate, translate, and narrate the feminisms outside of Europe and what they have done, what they are aiming to do. Tamil Nadu, for instance, had a social movement called the Self Respect Movement, and one of its most visionary leaders was Thanthai Periyar. And even in the 1920s and 1930s, they were already advocating for anti-caste marriages, nonreligious marriages, divorce, remarriage, equal education, and representation, including in the police forces, and, most of all, a women’s control over her own body, a woman’s choice to be free of the burden of motherhood and social reproduction if she so wished! These were progressive and far, far ahead of their time. These rich traditions are not copycats of European feminism—I think progressive European ideas no doubt influenced people, there was always the circulation of thought and ideas—but they also evolved very much in the Tamil context, and they went far beyond what was being articulated by the feminists who were from European colonial backgrounds.

How do we write about all of this? A full-frontal attack, like the one my friend and scholar Rafia Zakaria makes in Against White Feminism brilliantly and without pulling any punches? Something in-depth, thoughtful, and historical, as Francois Verges does in A Decolonial Feminism? Or something like Radicalizing Her, which scholar-activist Nimmi Gowrinathan wrote after spending more than a dozen years of her life interviewing and studying the female militants of our times—it’s a sharp and essential contribution to understanding women taking up arms as a reaction to state violence. These are phenomenal contributions, and I urge you to read them all.

My academic training would have told me to analyze and parse what was happening with the Tamil Tigresses, but my first instinct was to approach this as a storyteller, or rather, as someone who could facilitate the telling of their stories. In my mind, The Orders Were To Rape You is a book that does not spend its time rejecting the frameworks of white feminism, or rehashing much of European feminism’s suspicion toward national liberation struggles (which are in fact struggles necessitated because of colonialism) or the way white feminism seeks to portray all women who choose to join a guerrilla struggle as brainwashed cultists, or addressing some dainty white feminist argument about violence = bad, without situating it contextually. Abandoning this framework, refusing to anticipate and answer these questions, is liberatory in and of itself. I wanted to place on record the women’s stories in their own words. This was not just true of the Tamil Tigresses I got to interview, but also of the Tamil Tigresses who wrote poetry. They were very clear in what they were doing: linking the process of fighting for liberation to a struggle to smash patriarchy. It was important to bear witness to and chronicle their dreams, and their subsequent disillusionment. Just as the Tigers’ testimony in the book lays bare the nature of the Sinhala majoritarian state that used rape as a weapon of war during an ongoing genocide, the work of the Tigress-poets shows their political outlook. In that sense, to answer your question, yes—this book is a text that shows what an anti-imperialist feminism looks like, and the dangerous price (sexual violence, death) that women have had to pay in this struggle.

Meena Kandasamy (b. 1984) is an anti-caste activist, poet, novelist, and translator. Her writing aims to deconstruct trauma and violence while spotlighting the militant resistance against caste, gender, and ethnic oppressions. She explores this in her poetry and prose, most notably in her books of poems such as Touch (2006) and Ms Militancy (2010), as well as her three novels, The Gypsy Goddess (2014), When I Hit You (2017), and Exquisite Cadavers (2019). Her latest work is a collection of essays, The Orders Were to Rape You: Tamil Tigresses in the Eelam Struggle (2021). Her novels have been shortlisted for the Women’s Prize for Fiction, the International Dylan Thomas Prize, the Jhalak Prize, and the Hindu Lit Prize.

She has been a fellow of the University of Iowa’s International Writing Program (2009), a Charles Wallace India Trust Fellow at the University of Kent (2011), and is presently a fellow of the Berlin-based Junge Akademie (AdK).

Activism is at the heart of her literary work; she has translated several political texts from Tamil to English, and previously held an editorial role at The Dalit, an alternative magazine. She holds a PhD in sociolinguistics. Her op-eds and essays have appeared in the White Review , Guernica , The Guardian, and the New York Times , among others.

1. Mahinda Rajapaksa was the president of Sri Lanka from 2005 to 2015. His brother, Gotabaya Rajapaksa, who is currently president, appointed Mahinda Rajapaksa as prime minister in 2019. ↩

Related Reading:

“Changing Landscapes and Identities: An Introduction to Tamil Writing” by Lakshmi Holmström

“Women, Writing War” by Eliza Griswold

“ T he Origins of the FARC: An Interview with Sergeant Pascuas” by Alfredo Molano, translated by Ezra E. Fitz

Suhasini Patni

Suhasini Patni is a freelance writer based…

Revitalizing the Rajasthani Language: An Interview with Vishes Kothari

“the landscape around us”: marcia lynx qualey’s ottaway award acceptance speech, writing that mattered in 2022.

International Research Journal of Tamil

- About About the Journal Privacy Statement

- Articles & Issues Current Archives

- Editorial Team

- Submissions

- Guidelines Author Guidelines Recommended Reviewer Complaint Policy Ethical & Malpractice Policies Advertising Policy Licenses, Copyright & Permissions Peer - Review & Publication Policies Article Retraction & Withdrawal Policy Policies on Conflict of Interest and Informed Consent

- Article Processing Fee

Feminism in Periyar's View

Published 2022-12-10

- Freedom of Speech

How to Cite

Download citation.

Copyright (c) 2022

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

Plum Analytics

Periyar, an Unparalleled Humanist in the Twentieth Century. Earlier his life and philanthropic spirit got trapped in the darkness of intense ignorance and later it brought light to the society to dispel the ignorance of the people. He condemned God, religion, caste, ritual and formality and he root out superstitions. Although many leaders in India emerged to save women from the sufferings, periyar’s ideals were great. Ever since the dawn of human society, men have dominated women in one way or another. Chastity, morals, education, property rights, employment, choosing a life partner etc. in all these things women should have equal rights to men. This article explains that men and women must be treated equally and both should not be superior or inferior. Also, Periyar was a rational thinker all these things in 20 years which would have been taken twenty centuries.

- Aadhiveerapandian, (1962) Vetriverikai, Arjipathi Company, Chennai, India.

- Aannaimuthu, V. (1974) Periyar E.V.R. Sinthanaikal, Kazhaga Veeliyedu, Chennai, India.

- Bharathidasan, (2019) Bharathidasan Kavidhaigalil Penniyamum Periyarum, Naam Thamizhar Pathippagam, Chennai, India.

- Bharathiyar, (2001) Bharathiar Kavithaikal, Sri Hindu Pathippagam, Chennai, India.

- Ilampuranar, (1966) Tholkappiyam Porulathikaram- Ilampuranar Urai, First Edition, Saradha pathippagam, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India.

- Periyar, (1936) Kudiaarasu, Periyar Suyamariyathai Pirachara Niruvanam, Chennai, India.

- Periyar, (1948) Viduthalai, Periyar Suyamariyathai Pirachara Niruvanam, Chennai, India.

- Vairamuthu, (1999) Melukuvarththi, Surya Pathippagam, Chennai, India.

- Research Repository

- Faculty of Arts

- Media Studies

| Title: | Portrayal of Women in Indian Tamil Films Directed by Women: A Feministic Reading |

| Authors: | |

| Keywords: | Indian Tamil Cinema;Portrayal;Female Directors;Feministic Reading |

| Issue Date: | 2018 |

| Publisher: | 5th International Conference on Social Sciences 2018 (ICOSS 2018) |

| Abstract: | The world we live in is clearly permeated with media. Films are the twentieth century’s definitive medium of mass communication. In that powerful medium, the representation of women in films is highly complex and popular on movies and is increasingly more demands. The women portrayal continues in local cinema with other formulas throughout the history. The aim of this study is to determine the portrayal of women representation in Indian Tamil films; which were directed by women directors. The prime objective of this study is to analyse how the films of women directors having specific approaches on portrayal of women in their films. And, the secondary objective is to investigate significant differences between the men directors and women directors when they portray the women in their respective films. The sociological approach employs in this study through the feministic reading and three films which are recently directed by women are selected by the researcher as samples. The content analysis was used by the researcher in both qualitative and quantitative ways to find out the answer for the research questions: how women portrayed in Indian Tamil films, films were directed by women and how women directors handled gender issues in their films. The findings of the research exposed that the most part of the scenes portray the women as smart, energetic and able to make their own decisions and not in stereotypes. Further, the findings revealed that, even though, the women characters show the innocence, they become stronger when the male dominant society put pressures on them. While the male directors portray the women character as dependent largely, the women directors produce them not depending on anybody. On other side, the study made known that the portrayal of women in the scenes involve with physical affections and the exposure of female body were elaborated and illustrated in detail of the point of view of the women by female directors than male counterparts. |

| URI: | |

| Appears in Collections: | |

| File | Description | Size | Format | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 982.54 kB | Adobe PDF | |

Items in DSpace are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise indicated.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Feminism and Feminists in Tamil Nadu -Fifty Years of Founded Disinterest

Related Papers

The world all are women’s equal in all societies, women have claimed equal status with men. It is of a vital importance in modern social science studies, and involves serious research. Progress in attitude, behavior, pattern and legal system is inevitable in all civilized societies. In a progressive society the rights and obligations were determined on the basis of status of an individual.This paper examines historically the status of special reference to Tamil Nadu women. The level of culture of a particular society can very well be judged by the position of women in that society. Women especially the married one, enjoyed a position of respect and authority in the family as well as in society.

Centre for Social Studies Golden Jubilee Lecture Series 2

Vibhuti Patel

Main concerns of women’s movement in India have been: • Men outnumber women in India, unlike in most countries where the reverse is the case. • Majority of women go through life in a state of nutritional stress - they are anaemic and malnourished. Girls and women face nutritional discrimination within the family, eating last and least. • The average Indian woman has little control over her own fertility and reproductive health. • Literacy rate is lower in women as compared to men and far fewer girls than boys go to school. Even when girls are enrolled, many of them drop out of school. • Women’s work is undervalued and unrecognized. Women work longer hours than men and carry the major share of household and community work, which is unpaid and invisible. • Once ‘women’s work’ is professionalized, there is practically a monopoly on it by men. For example, the professional chefs are still largely men. The Sexual Division of Labour ensures that women will always end up as having to prioritize unpaid domestic work over paid work. It is not a ‘natural’ biological difference that lies behind the sexual division of labour, but certain ideological assumptions. • Women generally earn a far lower wage than men doing the same work, despite the Equal Remuneration Act of 1976. In no State do women and men earn equal wages in agriculture. • Women are under-represented in various bodies of governance as well as decision-making positions in both public and private sectors. • Women are legally discriminated against in land and property rights. Most women do not own property in their own names and do not get a share of parental property. • Women face violence inside and outside the family throughout their lives.

suma scaria

Nabeela Siddiqui

Darshi Thoradeniya

This essay analyses the implications of the state performing a welfare function for an extended period of time in relation to the social contract between women citizens and the state. It argues that a prolonged status of 'welfare provider' ascribes certain patriarchal attributes to the state, which in turn reduces the position of the citizens, especially women, to a mere 'beneficiary' level. With the use of two specific policy documents relating to public health – Well Woman Clinic (WWC) programme launched in 1996, and the Population and Reproductive Health (PRH) policy designed in 1998 – it shows that in the absence of a rights based approach to public health, women have become mere beneficiaries, as opposed to active citizens, of the prolonged welfare State of Sri Lanka. This relationship has deterred women citizens from exercising the right to demand their needs from the State.

Rajni Palriwala

Kenneth Bo Nielsen , Anne Waldrop

International Research Journal Commerce arts science

Haryana More than half of the population of the world is made of woman but she is not treated at par with man despite innumerable evolutions and revolutions. She has the same mental and moral power, yet she is not recognized as his equal. In such conditions the question of searching her identity is justified. Actually in this male dominated society, she is wife, mother, sister and homemaker. She is expected to serve, sacrifice, submit and tolerate each ill against her peacefully. Her individual self has very little recognition in the patriarchal society and so complete selflessness is her normal way of life. Inspite of all brouhaha and sloganeering about woman lib, the blink ring view that woman's place in India is within the four walls of a home that pervades the entire system. The crime statistics against woman and the cases reported and unreported of female feticides, rapes, sati, devdasi, prostitution, use and throw like divorce practices rampant in society even after sixty years of independence, all are indicative of the fact that what we talk about woman, we aspire not. The ideas, thoughts, traditions, and practices reflect anti woman attitude and the values fixed by patriarchal hegemony have made the life of the woman much more pitiable. Various feminist movements right from mid 19 th century till the recent decade establish the fact that women have been neglected throughout the world on one pretext or the other. They are oppressed under a system of structural hierarchies and injustices. Besides, certain relational hierarchies direct women against one another in a family setup. The patriarchal male dissuades them their rights by supporting the one who is inadvertently provided a higher position in the hierarchy. Women are hindered not by lack of ability but by bias and outmoded institutional structures. And a nation is an era of global competition cannot afford such under use of precious human capital. The intense culture bias relegated woman to playing second fiddle. Woman central issues are always tainted with male bias. Woman has always been restricted, forced, pressurized, and persuaded to be a homemaker, supportive spouse, esteemed mom, and professional success for man. And she gradually melded all these personas, letting the male all the glory, just for peace of mind.

Sumit S A U R A B H Srivastava

Parliament’s Representation of Women: A Selective Review of Sri Lanka’s Hansards from 2005-2014

Shermal Wijewardene

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

International journal of health sciences

deshdeep singh

Mridula Sharda

Kumkum Bhattacharya

Pam Sarulchana

Vibhuti Patel , Radhika Khajuria

AARF Publications Journals

Stephanie Anketell

Priyanthi Bagchi , Asim Karmakar

Pat O Connor

Journal ijmr.net.in(UGC Approved)

karen leonard

Rajakumar Tenali

Tahesin Malek

Journal of emerging technologies and innovative research

RISHI KUMAR

Nilika Mehrotra

The Indian Journal of Public Administration

Radhika Kumar

biplove kumar

Lakshmi Lingam

Dr. Hari Krishna Behera

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

The Modern Tamil Novel: Changing Identities and Transformations

- First Online: 31 March 2017

Cite this chapter

- Lakshmi Holmström 3

319 Accesses

This essay examines the articulation of voices and genres of the Indian contemporary multilingual canon by introducing Tamil fiction and the impact of translation on it. Holmström reconstructs the development of the modern novel in Tamil in the past decades, discussing in particular some authors who have been deemed to be extremely influential on the course of recent Tamil literary history. Ashokamitran, Sundara Ramaswamy, Ambai, and Bama have narrated the story of the individual in times of political and social change both in Tamil Nadu and in India, each with their own innovative point of view, including feminist, Dalit, and diasporic perspectives. Many important works by these four novelists have been translated into other Indian languages as well as into English. Some have been translated into European languages such as French, Spanish, and German. Yet some translations have taken on a life of their own, while others have not. In the essay’s final remarks, the relationship between the original text and its successful translation is explored.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction: Intellectual Traditions of India in Dialogue with Mikhail Bakhtin

“No Blind Admirer of Byron”: Imperialist Rivalries and Activist Translation in Júlio Dinis’s Uma Família Inglesa

Self-Translation and Exile in the Work of Catalan Writer Agustí Bartra. Some Notes on Xabola (1943), Cristo de 200.000 brazos (Campo de Argelés) (1958) and Crist de 200.000 braços (1968)

Ambai (1992) A Purple Sea , translated with an introduction by Lakshmi Holmström, Madras: Affiliated East-West Press.

Google Scholar

Ambai (2006) In a Forest, a Deer , translated by Lakshmi Holmström, New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Ambai (2012) Fish in a Dwindling Lake , translated by Lakshmi Holmström, New Delhi: Penguin India.

Ashokamitran (1993) Water , translated by Lakshmi Holmström, London:Heinemann; 2nd edition, New Delhi: Katha, 2001.

Bama (2000) Karukku , translated with an introduction by Lakshmi Holmström, Chennai: Macmillan India, 2nd edition, New Delhi: OUP India, 2012.

Bama (2005) Sangati: Events , translated with an introduction by Lakshmi Holmström, New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Cheran (2013) In a Time of Burning , translated by Lakshmi Holmström, Todmorden: Arc.

Doraiswamy, T.K. (1974) ‘Ashokamitranin Tannir’ in Pakkiamuttu T. (ed.) Vidudalaikkuppin Tamil Naavalkal . Madras: Christian Literature Society, n.p.

Ebeling, S. (2010) Colonizing the Realm of Words: The Transformation of Tamil Literature in Nineteenth-Century South India , Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Gauthaman, R. (1995) ‘Olivattangal Tevai Illai’ [‘We Have No Need for Haloes’] in India Today Annual , pp. 96–98.

Pudumaippittan (1954) Pudumaippittan Katturaigal , Madras: Star Publications.

Ramaswamy, S. (2013) Children, Women, Men , translated by Lakshmi Holmström, New Delhi: Penguin India.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Norwich, England

Lakshmi Holmström

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Lakshmi Holmström .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

English and Anglophone Literatures, University of Naples ‘L’Orientale’, Naples, Italy

Rossella Ciocca

School of English, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom

Neelam Srivastava

Copyright information

© 2017 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Holmström, L. (2017). The Modern Tamil Novel: Changing Identities and Transformations. In: Ciocca, R., Srivastava, N. (eds) Indian Literature and the World. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-54550-3_6

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-54550-3_6

Published : 31 March 2017

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, London

Print ISBN : 978-1-137-54549-7

Online ISBN : 978-1-137-54550-3

eBook Packages : Literature, Cultural and Media Studies Literature, Cultural and Media Studies (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Let Me Explain

- Yen Endra Kelvi

- SUBSCRIBER ONLY

- Whats Your Ism?

- Pakka Politics

- NEWSLETTERS

Why tribal school girls in TN flung dupattas in the air to welcome a feminist writer

As Geeta Ilangovan, the author of a collection of feminist essays titled Dupatta Podunga Thozhi ('Wear a dupatta, girlfriend') arrived at the venue of a three-day workshop for female students of tribal schools in Tamil Nadu, scores of dupattas went flying out of classroom corridors. It was a gesture to show how much the students resonated with Geeta’s essay on women’s relationship with their own bodies, bodily autonomy, and the imposition of a garment to cover breasts instead of leaving it to the girls’ choice.

Over 150 girls from various Government Tribal Residential schools in Tamil Nadu’s Kallakurichi district gathered at the district headquarters last week for the workshop that discussed subjects like sexuality education, feminism, and agency. It was on March 12, the second day of the workshop themed ‘Empower Her/Avaladhigaram,’ that the powerful visual from the camp was shared on social media.

The sessions were organised as part of a programme aimed at bringing down school dropout rates and child marriages among tribal girls from the Kalvarayan Hills. The video, which went viral, has reignited familiar discussions on women’s choice, and their right to cover themselves and dress how they please. While the conversations continue, Tamil writer Geeta along with Nivedita Louis, the publisher of her book, and the organisers of the workshop told TNM that the students participated in the act of their own will, almost risking censure from school authorities and their families.

The symbolic act of flinging dupattas in the air

Sandhiyan Thilagavathy, the founder of AWARE India, an NGO working with the Kallakurichi district administration to implement a sexuality education and life skills programme in government tribal residential schools, explains that prior to this workshop, his team has been regularly visiting the students of 11 schools since November. They have conducted sessions on subjects including body positivity, self-esteem, peer pressure, relationships, gender identity, sexual and reproductive rights, and mental health.

View this post on Instagram A post shared by AWARE India (@awareindia2020)

Read: ‘Dupatta podunga doli’: The underlying sexism in mainstream Tamil meme pages

It was on the first night of the three-day workshop when the students were seated around a campfire with writer and publisher Nivedita Louis, that she initiated the conversation on clothing. “I asked them what they felt was the most constricting dress. They said that from the moment they attained puberty, they are told to cover their breasts and wear a dupatta, which they didn’t like,” says Nivedita. As they agreed with Geeta’s essay, Nivedita suggested half-seriously that they could get rid of their dupattas to show their appreciation for her essay when the writer arrived the next day. “I didn't think that they would actually do it. It happened spontaneously,” says Nivedita.

Sandhiyan says that the girls risked backlash from their teachers to go ahead with the act, and proceeded without any coercion from adults. After the video was shot, the girls went downstairs to pick up their dupattas and according to Sandhiyan, some of them decided to leave theirs in the classroom and attend the day’s session without wearing them. While some were vocal about rejecting it, some students chose to wear it immediately after the video was shot, he says, either because they were worried about consequences, or because they felt more comfortable wearing one.

Geeta, who is also an independent filmmaker, was delighted by the gesture. She recalls that some students insisted they didn’t want to wear a dupatta at least for that one day, to exercise their agency. “Some children were wearing dupattas because we told them it is up to them to decide. It’s just not the duty of others to tell them what to wear or what not to wear,” she says.

Nivedita acknowledges some of the criticism directed towards the video, including the argument that women from oppressed communities had strived hard for the right to cover their upper bodies. “There are different perspectives and arguments against this video, but there are also people supporting it, saying that covering up is a woman's choice, whether with a burqa or a dupatta,” she says.

Talking about her essay collection, Geeta says it was partly intended to be an introduction to feminist ideas for adolescents. “The first essay, (‘Dupatta Podunga Thozhi’), discusses the shame women feel about their bodies due to social conditioning. I wanted to tell them to be proud of their body, and understand that it’s a tool to work and express themselves, their intelligence, and courage,” says Geeta, adding that the book also urges youngsters to understand the work of Periyar and Ambedkar in order to understand life itself.

Read: A look at the history of the Channar Revolt as Pinarayi, Stalin commemorate it

Sexuality education, feminism, and more

Sandhiyan says the students read many other texts at the workshop, some of them published by Her Stories , a Tamil feminist publishing house run by Nivedita. Movies and web series such as J aya Jaya Jaya Jaya Hey, Gargi, Ponmagal Vandhal , and Ayali were also screened to propel the conversations initiated in AWARE India’s earlier sessions.

“In other parts of the state, we usually partner with parents and teachers to help us better communicate sensitive topics to young girls,” Sandhiyan says. However, in the tribal residential schools, with parents and other members of the community remaining largely inaccessible, libraries were set up with books that could help adolescents navigate difficult experiences.

Geeta and Nivedita both say that while they were initially unsure if the students had read the texts, they soon learned that many of the writings had struck a chord with them. Geeta says the students talked about patriarchy, restrictions on the way they dress, their education and ambitions, romantic relationships, having multiple partners before marrying someone, monogamy as a norm, the choice to be child-free, and many other topics that they read up on and found relatable.

“Due to familial and peer pressure, there is a high risk of the students dropping out and having to get married. This is exacerbated by poverty, and the pandemic too. We discussed the importance of withstanding all kinds of pressure to focus on education and financial independence,” says Geeta.

Related Stories

Essay on Feminism

500 words essay on feminism.

Feminism is a social and political movement that advocates for the rights of women on the grounds of equality of sexes. It does not deny the biological differences between the sexes but demands equality in opportunities. It covers everything from social and political to economic arenas. In fact, feminist campaigns have been a crucial part of history in women empowerment. The feminist campaigns of the twentieth century made the right to vote, public property, work and education possible. Thus, an essay on feminism will discuss its importance and impact.

Importance of Feminism

Feminism is not just important for women but for every sex, gender, caste, creed and more. It empowers the people and society as a whole. A very common misconception is that only women can be feminists.

It is absolutely wrong but feminism does not just benefit women. It strives for equality of the sexes, not the superiority of women. Feminism takes the gender roles which have been around for many years and tries to deconstruct them.

This allows people to live freely and empower lives without getting tied down by traditional restrictions. In other words, it benefits women as well as men. For instance, while it advocates that women must be free to earn it also advocates that why should men be the sole breadwinner of the family? It tries to give freedom to all.

Most importantly, it is essential for young people to get involved in the feminist movement. This way, we can achieve faster results. It is no less than a dream to live in a world full of equality.

Thus, we must all look at our own cultures and communities for making this dream a reality. We have not yet reached the result but we are on the journey, so we must continue on this mission to achieve successful results.

Impact of Feminism

Feminism has had a life-changing impact on everyone, especially women. If we look at history, we see that it is what gave women the right to vote. It was no small feat but was achieved successfully by women.

Further, if we look at modern feminism, we see how feminism involves in life-altering campaigns. For instance, campaigns that support the abortion of unwanted pregnancy and reproductive rights allow women to have freedom of choice.

Moreover, feminism constantly questions patriarchy and strives to renounce gender roles. It allows men to be whoever they wish to be without getting judged. It is not taboo for men to cry anymore because they must be allowed to express themselves freely.

Similarly, it also helps the LGBTQ community greatly as it advocates for their right too. Feminism gives a place for everyone and it is best to practice intersectional feminism to understand everyone’s struggle.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Conclusion of the Essay on Feminism

The key message of feminism must be to highlight the choice in bringing personal meaning to feminism. It is to recognize other’s right for doing the same thing. The sad part is that despite feminism being a strong movement, there are still parts of the world where inequality and exploitation of women take places. Thus, we must all try to practice intersectional feminism.

FAQ of Essay on Feminism

Question 1: What are feminist beliefs?

Answer 1: Feminist beliefs are the desire for equality between the sexes. It is the belief that men and women must have equal rights and opportunities. Thus, it covers everything from social and political to economic equality.

Question 2: What started feminism?

Answer 2: The first wave of feminism occurred in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It emerged out of an environment of urban industrialism and liberal, socialist politics. This wave aimed to open up new doors for women with a focus on suffrage.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

பெண் உரிமை லட்சினை. பெண்ணியம் (feminism) என்பது பெண்களை ...

சுற்றுச் சூழல் பாதுகாப்பு (Environment protection in tamil) கல்வி (Importance of education in tamil) அமைதி (Peace in tamil)

women in Tamil literature has been quite an articulate aspect. Right from the turn of century most nationalistic texts dealt with the plight of women especially child marriage and widowhood. In fact, most male writers like Ramasami -Kootha Theevu - ( a feminist Utopia) of pre-independence era have evinced a sympathetic portrayal

The essay aims to disband the accepted, though disturbing and monolithic category of "the good Tamil woman." In its place, Comeau offers an opportunity to acknowledge and promote the relative diversity of roles played by female characters in fictional verses. Keywords: feminism, South Asian religion, Tamil literature, women in Hinduism ...

Feminism in the view of tamil wome n writers V. Rajendran a, * , A. Packiamuthu b a Department of Tamil, Scott Christian College ( Autonomous), Nagarcoil- 629001 , Tamil Nadu, India .

Keywords: Eco-feminism, environmentalism, Tamil women's poetry, women and environment. Introduction: Tamil language and literature has a rich legacy and Tamil poetry has 2500 years old history. During classical times all writing - including writings on medicine, astrology, architecture and the art of music,

newspaper, ZSvadesa-mittiran [ came in 1880. Tamil prose literature was first written during the 17th and 18th centuries. It became an independent genre in the 19th century. One of the founders of Tamil prose was Vedanayakam Pillai, who wrote the first Tamil Novel, ZPiratapa Mutaliyar harithram [. This was a landmark in Tamil literature.

This essay also tries to give the statistics of the books published, especially the books about Feminism, and the Anthology of Tamil women poems. In Tamil context, so far Tamil fictions have ...

Feminism explains the cultural constructs and gender formation created by men and shows up how the old cultural values changed with the formation of new cultural values. Feminist ideas are mentioned in Tolkappiyam, Sangam literature, devotional literature, epics, mythology and modern literature. ... International Research Journal of Tamil, 4(S ...

In the recent Tamil context, there are two major topics that were highly spoken namely Feminism and Dalitism. In the two-thousand-year-long history of Tamil literature, the space for women and their literature was limited. ... A., (2022). Feminism in the view of Tamil Women Writers, International Research Journal of Tamil, 4(SPL 1), 147-152 ...

Total literacy rate in Tamil Nadu has shown an increasing trend over the years, increasing from 62.66% in 1991 to 80.33% in 2011. 14 districts have female literacy rates above the State average that is, above 73.86%. Women leaders of the state have in the recent years have only been meme topics and insults on-stage by politicians.

Co-author: Radhika Coomaraswamy. This essay explores the history of gender and Tamil nationalism from the colonial context until the final round of peace talks in the early two thousands in Sri Lanka. The paper explores different feminist arguments made about women impacted by Tamil nationalism.

Being feminist the tamil way. V. Geetha. See Full PDF Download PDF. See Full PDF Download PDF. Related Papers. Notes towards a Tamil Patriarchy. V. Geetha. Download Free PDF View PDF. FEMINIST MOVEMENT IN INDIA ANAMIKA 1 & GARIMA TYAGI 2 ...

Chennai-born Meena Kandasamy is an award-winning novelist and poet, best known for her book When I Hit You. She started translating at the age of eighteen and has worked on speeches and writings by activist and politician Thol. Thirumavalavan, writer Salma, Tamil Eelam poets, and many more. Her work is an active resistance against gender- and ...

Feminism refers to the struggle of women for equal rights in a peaceful way. Bama's first noval Karukku is the first Dalit Novel in Tamil literature. Women endowed with education along can come out from the darkness of ignorance to the radiant light of radical thoughts. Only such women can ignite the spark of reformation in the women ...

Periyar, an Unparalleled Humanist in the Twentieth Century. Earlier his life and philanthropic spirit got trapped in the darkness of intense ignorance and later it brought light to the society to dispel the ignorance of the people. He condemned God, religion, caste, ritual and formality and he root out superstitions. Although many leaders in India emerged to save women from the sufferings ...

The literacy rate in the state was. 86.8% for m en and 73.4% for women in 2011, according to the census. In Tamil Nadu, there. is a gender gap in literacy rates between rural and urban areas. 91.8 ...

The movie focuses elements like female infanticide, sentiments, emotions, local culture, dowry, male dominance, liability to bring in male heirs and financial crisis Impact Factor (JCC): 2.8058 ...

Indian Tamil Cinema;Portrayal;Female Directors;Feministic Reading: Issue Date: 2018: Publisher: 5th International Conference on Social Sciences 2018 (ICOSS 2018) Abstract: The world we live in is clearly permeated with media. Films are the twentieth century's definitive medium of mass communication. In that powerful medium, the representation ...

Feminism and Feminists in Tamil Nadu - Fifty Years of Founded Disinterest A paper read at a seminar organized to reflect on the Dravidian Movement, 2017 V. Geetha I am not sure whether this ought to be a commemorative moment, or one to wonder at - given the comic-tragic apotheosis of everyday Dravidian politics in Tamil Nadu.

This essay examines the articulation of voices and genres of the Indian contemporary multilingual canon by introducing Tamil fiction and the impact of translation on it. ... Tamil, history and culture. In this way, it tracks a feminism which is specific to Tamil writing. Rewriting Dalit Identity: Bama's Karukku and Sangati 'Bama' is the ...

As Geeta Ilangovan, the author of a collection of feminist essays titled Dupatta Podunga Thozhi ('Wear a dupatta, girlfriend') arrived at the venue of a three-day workshop for female students of ...

500 Words Essay On Feminism. Feminism is a social and political movement that advocates for the rights of women on the grounds of equality of sexes. It does not deny the biological differences between the sexes but demands equality in opportunities. It covers everything from social and political to economic arenas.