To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, toward a holistic theory of strategic problem solving.

Team Performance Management

ISSN : 1352-7592

Article publication date: 1 May 1999

To date, many of the models and theories that seek to explain problem solving and decision making, have tended to adopt an overly reductionist view of the processes involved. As a consequence, most theories and models have proved unsuitable in providing managers with a practical explanation of the dynamics that underpin problem solving. A substantial part of a manager’s time is taken up with problem solving and decision making issues. The question of whether managers possess the necessary problem solving skills, or have access to “tools”, which can be used to manage different types of problems, has become an issue of some importance for managers and organisations alike. This paper seeks to contribute to the current literature on problem solving and decision making, by presenting a conceptual model of problem solving, which is intended to assist managers in developing a more holistic framework for managing problem solving issues.

- Strategic management

- Problem solving

- Decision making

O’Loughlin, A. and McFadzean, E. (1999), "Toward a holistic theory of strategic problem solving", Team Performance Management , Vol. 5 No. 3, pp. 103-120. https://doi.org/10.1108/13527599910279470

Copyright © 1999, MCB UP Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Suggestions or feedback?

MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Machine learning

- Social justice

- Black holes

- Classes and programs

Departments

- Aeronautics and Astronautics

- Brain and Cognitive Sciences

- Architecture

- Political Science

- Mechanical Engineering

Centers, Labs, & Programs

- Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL)

- Picower Institute for Learning and Memory

- Lincoln Laboratory

- School of Architecture + Planning

- School of Engineering

- School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences

- Sloan School of Management

- School of Science

- MIT Schwarzman College of Computing

Adopting a holistic approach to problem-solving in business

Press contact :.

Previous image Next image

“Price discounting is one of my pet peeves,” says Sharmila Chatterjee. No, the academic head for the Enterprise Management (EM) Track of MIT Sloan School of Management’s MBA program doesn’t have it out for customers looking for a deal. Rather, this is a stitch in a running thread of conversation about bigger-picture thinking honed from years of research.

Chatterjee is a business-to-business (B2B) marketing expert and an award-winning case writer who examines issues in the domains of channels of distribution, sales force management, and relationship marketing. “No one should be engaged in price gouging, of course,” she says, “but get an equitable return on the value delivered through your offerings, such that you can sustain investments for the long-term success of your brand.”

Citing Millward Brown’s finding that brands account for more than 30 percent of the stock market value of companies in the S&P 500 index, The Economist acknowledged that for many companies, their brand is their most valuable asset. Consider United Airlines' 2017 branding crisis that resulted in their stock plummeting $1.4 billion in a matter of days after video footage emerged showing the forced removal of a passenger from an overbooked flight.

Brand, according to Chatterjee, is a function of customer experience. In a 2019 opinion piece for USA Today , Chatterjee outlined the importance of customer experience by examining the case of bricks-and-mortar (B&M) retailers. When e-commerce emerged in the early 1990s, traditional retailers tried to compete by slashing prices. As a result, they were forced to cut costs elsewhere: They whittled down sales teams, neglected investment in training, and ignored merchandising and product development — all to the detriment of the in-person customer experience.

Their misapprehension of the situation resulted in a self-fulfilling prophecy. Customers flocked online for discounts, leaving, among others, big brands like RadioShack, Toys R Us, and Sears to file for bankruptcy. In an unexpected twist, the rise of the digital age exposed the importance of the human interface. Today, savvy retailers recognize the benefits of combining e-commerce and B&M, integrating online and offline. “Technology is a great facilitator and enabler. Problems arise when we turn to technology as a panacea,” warns Chatterjee. “Human capital is critical for successful outcomes in most cases — minimizing this comes at a great cost.”

For further evidence of the need for human-tech complementarity, we need look no further than the high rates of technology implementation failures experienced by businesses today. In 2001, Gartner reported a 50 percent failure rate of customer relationship management (CRM) implementation. Fast-forward to 2021, and those numbers have only increased. How to reconcile this with the fact that CRM spending shows no sign of slowing down, and for many businesses, CRM has become the largest revenue area of spending in enterprise software?

Meanwhile, a recent study conducted by MIT Sloan Management Review with Boston Consulting Group found that technology implementation failure rates of 70 percent or higher are the norm, and only 10 percent of companies report significant returns on their AI investments. “There is obviously enormous potential for technology to deliver value, but the potential is not being realized, and therein lies the role of human capital,” says Chatterjee.

In an effort to understand the high rate of technology implementation failures, particularly in the B2B context, Chatterjee conducted an empirical analysis of buying organizations that purchased and implemented business intelligence software. She found that the most significant predictors of both successful technology assimilation and overall customer satisfaction were related to a set of intangibles that the buyer assigned to the software seller; the “soft” service facet, reflecting a holistic understanding of the customer’s business context, value creation potential, and pathway to value.

She calls this the “value mindset.” Once a business has a competitive product, they need to be able to communicate how to best extract the potential value from the technology. This means, among other things, sharing with the buyer the change management needed in the legacy processes as well as best business practices and lessons learned from failure. Sellers that communicated “value mindset,” according to Chatterjee, experienced significantly higher rates of customer satisfaction — to the extent of a three-to-one effect. “Again, this demonstrates in spades the incredible value of the human interface — value not communicated is value not delivered. Again, technology and humans as complements,” she explains.

Chatterjee's research began with a fascination with information silos fostered during her time as a graduate student at the Wharton School, where she first became aware of a statistic that found a mere 30 percent of marketing leads were pursued by sales teams. This revelation regarding the gap in the sales-marketing interface was something Chatterjee channeled into years of research in the domain of sales lead management and customer retention. Focused on this disconnect between human behavior and the rhythms of capitalism, she would go on to conduct some of the first studies in the critical area of the sales-marketing interface, specifically sales lead management, including a study she and her colleagues titled " The Sales Lead Black Hole: On Sales Rep’s Follow-up of Marketing Leads ."

A self-proclaimed empiricist in her research, Chatterjee employs surveys coupled with econometric methods for analysis that tests models in the real world. This focus on real-world business challenges extends to her administrative role leading the EM Track at MIT. All MBA programs deliver content, whether it be in finance, marketing, operations, or leadership. But at the Institute, Chatterjee emphasizes the importance of mindset. From the outset, students in the EM Track are encouraged to think like CEOs while on a pathway to future leadership. In practice, this means training students to move away from siloed thinking while adopting a holistic, cross-functional approach to problem-solving in order to transform organizations.

The best way to instill this leadership mindset is for students to work on real-life business projects and challenges with companies while applying theoretical concepts and frameworks learned in the classroom. In their first year, students are thrown into the deep end. Through the Enterprise Management Lab (EM-Lab), EM Track students are provided the opportunity to work hands-on with large enterprises to address business challenges. "My students' work on real business challenges embodies the MIT motto “mens et manus,” mind and hand,” she says.

Companies like Procter & Gamble/Gillette, Amazon, BMW, and IBM have all participated in EM-Lab projects. “Multinationals come back to us year after year because we deliver useful findings that they can implement in their companies,” says Chatterjee. At the same time, MIT students benefit from the real-world experience, refining their research skills while developing the mindset of future business leaders. “It’s a very symbiotic relationship, a partnership that benefits all involved,” Chatterjee says.

Share this news article on:

Related links.

- Sharmila Chatterjee

- Video: Sharmila Chatterjee

- MIT Industrial Liaison Program

- MIT Sloan School of Management

Related Topics

- Business and management

- Digital technology

- Human Resources

- Technology and society

Related Articles

Amazon.com VP compares e-commerce and manufacturing

Mit sloan’s new track: enterprise management.

Previous item Next item

More MIT News

Most work is new work, long-term study of U.S. census data shows

Read full story →

Does technology help or hurt employment?

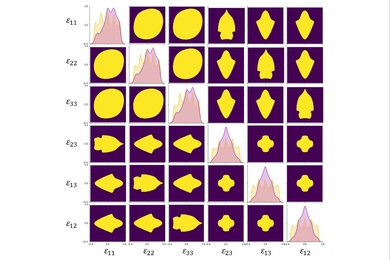

A first-ever complete map for elastic strain engineering

“Life is short, so aim high”

Shining a light on oil fields to make them more sustainable

MIT launches Working Group on Generative AI and the Work of the Future

- More news on MIT News homepage →

Massachusetts Institute of Technology 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA, USA

- Map (opens in new window)

- Events (opens in new window)

- People (opens in new window)

- Careers (opens in new window)

- Accessibility

- Social Media Hub

- MIT on Facebook

- MIT on YouTube

- MIT on Instagram

- Open Advanced Search

- Enterprise Plans

Get 20M+ Full-Text Papers For Less Than $1.50/day. Start a 14-Day Trial for You or Your Team.

Learn more →.

Sorry, your browser isn't supported.

Upgrading to a modern browser will give you the best experience with DeepDyve.

- Google Chrome

Toward a holistic theory of strategic problem solving

- References BETA

- Recommended

- Add to Folder

Have problems reading an article? Let us know here.

Thanks for helping us catch any problems with articles on DeepDyve. We'll do our best to fix them.

How was the reading experience on this article?

Check all that apply - Please note that only the first page is available if you have not selected a reading option after clicking "Read Article".

Include any more information that will help us locate the issue and fix it faster for you.

Thank you for submitting a report!

Submitting a report will send us an email through our customer support system.

References (85)

M. Extejt, M. Lynn (1996)

Inf. Manag. , 30

E.S. McFadzean

H. Mintzberg

R. Cyert, J. March (1964)

K. Glaister, D. Thwaites (1993)

Journal of General Management , 18

C. Kimble, Kevin McLoughlin (1995)

ArXiv , cs.CY/0102029

M.S. Darling

R. Belbin, Victoria Brown (2022)

A. Dennis, J. Valacich (1993)

Journal of Applied Psychology , 78

P. Nutt (1992)

Decision Sciences , 23

D. Mclellan (1988)

M. Eierman, F. Niederman, C. Adams (1995)

Decis. Support Syst. , 14

Rashi Glazer, J. Steckel, R. Winer (1992)

Management Science , 38

B. Massetti (1996)

MIS Q. , 20

Steve Cooke, N. Slack (1991)

S. Sitkin, Amy Pablo (1992)

Academy of Management Review , 17

R. Gallupe, A. Dennis, W. Cooper, J. Valacich, L. Bastianutti, J. Nunamaker (1992)

Academy of Management Journal , 35

Dorothy Leonard-Barton (2000)

R. Weisberg (1988)

B. Nelsen, M. Reed, M. Hughes (1992)

A. Pinsonneault, K. Kraemer (1990)

European Journal of Operational Research , 46

D. Vogel, J. Nunamaker (1990)

Inf. Manag. , 18

S. Rogelberg, J. Barnes-Farrell, C. Lowe (1992)

Journal of Applied Psychology , 77

T. Rickards (1974)

D. Power, Ramon Aldag (1985)

Academy of Management Review , 10

G. DeSanctis, M. Poole (1994)

Organization Science , 5

Thomas Peters, R. Waterman (1983)

Administrative Science Quarterly , 28

J. Kidd (1982)

Gerald Smith (1992)

Decis. Support Syst. , 8

James Evans (1997)

Interfaces , 27

H. Simon, A. Newell (1971)

American Psychologist , 26

C. Nemeth (1997)

California Management Review , 40

E.S. McFadzean, A. Money

Elspeth McFadzean (1997)

Creativity and Innovation Management , 6

Frances Milliken, D. Vollrath (1991)

Human Relations , 44

Richard Watson, G. DeSanctis, M. Poole (1988)

R. McLeod, J. Jones, Carol Saunders (1995)

Business Horizons , 38

Elspeth McFadzean (1998)

Management Decision , 36

James Higgins (1996)

Long Range Planning , 29

J. Swan (1995)

Human Relations , 48

I. Janis (1973)

The Journal of American History , 60

G. Āllport (1961)

O. Kharbanda, E. Stallworthy (1990)

Management Decision , 28

Archer Er (1980)

B. Travica, B. Cronin (1995)

International Journal of Information Management , 15

R. Volkema (1988)

Systems Research and Behavioral Science , 33

Teresa Amabile, Regina Conti, Heather Coon, J. Lazenby, M. Herron (1996)

Academy of Management Journal , 39

P. Todd, I. Benbasat (1992)

MIS Q. , 16

Teresa Amabile (1997)

M. Higgs (1996)

Gerald Smith (1989)

Management Science , 35

J. Katzenbach, D. Smith (1993)

Harvard business review , 71 2

C. Bartlett, S. Ghoshal (1995)

Long Range Planning , 4

J. George (1992)

Journal of Management , 18

J.R. Eiser, J. Van Der Pligt

B. Silverman (1995)

Interfaces , 25

S. Everwijn, J. Gaspersz, Th.H. Homan, R. Reuland (1990)

European Management Journal , 8

O. Behling, C. Schriesheim

James Evans (1992)

Interfaces , 22

A. Ven, A. Delbecq (1974)

Academy of Management Journal , 17

J. Vancouver (1996)

Behavioral science , 41 3

P. Gordon (1997)

Business Horizons , 40

M. West, N. Anderson, G. Hardy (1990)

R.P. Bentall

D. Fleet (1983)

Academy of Management Journal , 26

R. Sutton, Andrew Hargadon (1996)

Administrative Science Quarterly , 41

Alison Davis-Blake, J. Pfeffer (1989)

Academy of Management Review , 14

J. March, Z. Shapira (1987)

Management Science , 33

David Held (1983)

R. Cattell (1970)

A. Ven (1980)

Human Relations , 33

P. Licker (1997)

A. Newell (1973)

J. Barnard (1992)

Business Horizons , 35

- Team Performance Management /

- Volume 5 Issue 3

- Subject Areas /

- Business, Management and Accounting

To date, many of the models and theories that seek to explain problem solving and decision making, have tended to adopt an overly reductionist view of the processes involved. As a consequence, most theories and models have proved unsuitable in providing managers with a practical explanation of the dynamics that underpin problem solving. A substantial part of a manager’s time is taken up with problem solving and decision making issues. The question of whether managers possess the necessary problem solving skills, or have access to “tools”, which can be used to manage different types of problems, has become an issue of some importance for managers and organisations alike. This paper seeks to contribute to the current literature on problem solving and decision making, by presenting a conceptual model of problem solving, which is intended to assist managers in developing a more holistic framework for managing problem solving issues.

Team Performance Management – Emerald Publishing

Published: May 1, 1999

Keywords: Strategic management; Problem solving; Decision making; Paradigms; Models

Recommended Articles

There are no references for this article..

- {{#if ref_link}} {{ref_title}} {{ref_author}} {{else}} {{ref_title}} {{ref_author}} {{/if}}

Share the Full Text of this Article with up to 5 Colleagues for FREE

Sign up for your 14-day free trial now.

Read and print from thousands of top scholarly journals.

Continue with Facebook

Log in with Microsoft

Already have an account? Log in

Save Article to Bookmarks

Bookmark this article. You can see your Bookmarks on your DeepDyve Library .

To save an article, log in first, or sign up for a DeepDyve account if you don’t already have one.

Sign Up Log In

Subscribe to Journal Email Alerts

To subscribe to email alerts, please log in first, or sign up for a DeepDyve account if you don’t already have one.

Copy and paste the desired citation format or use the link below to download a file formatted for EndNote

Reference Managers

Follow a Journal

To get new article updates from a journal on your personalized homepage, please log in first, or sign up for a DeepDyve account if you don’t already have one.

Access the full text.

Sign up today, get DeepDyve free for 14 days.

Our policy towards the use of cookies

All DeepDyve websites use cookies to improve your online experience. They were placed on your computer when you launched this website. You can change your cookie settings through your browser.

cookie policy

Strategic Problem-Solving: A State of the Art

Ieee account.

- Change Username/Password

- Update Address

Purchase Details

- Payment Options

- Order History

- View Purchased Documents

Profile Information

- Communications Preferences

- Profession and Education

- Technical Interests

- US & Canada: +1 800 678 4333

- Worldwide: +1 732 981 0060

- Contact & Support

- About IEEE Xplore

- Accessibility

- Terms of Use

- Nondiscrimination Policy

- Privacy & Opting Out of Cookies

A not-for-profit organization, IEEE is the world's largest technical professional organization dedicated to advancing technology for the benefit of humanity. © Copyright 2024 IEEE - All rights reserved. Use of this web site signifies your agreement to the terms and conditions.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

A More Holistic Approach to Problem Solving

- B V Krishnamurthy

When you’re stuck on a problem, it often helps to step back and look at the bigger picture. You see things differently and discover new solutions. What I ask participants in my Total Leadership program to do is take the “four-way view” – the interaction among work, home, community, and self – and come up […]

When you’re stuck on a problem, it often helps to step back and look at the bigger picture. You see things differently and discover new solutions. What I ask participants in my Total Leadership program to do is take the “four-way view” – the interaction among work, home, community, and self – and come up with creative ways of bringing them together into a more coherent whole. I’ve found that when you do this, you see opportunities for change to which you were previously blind. The happy result: improved performance and satisfaction all the way around.

- B V Krishnamurthy is the Director and Executive Vice-President of Alliance Business Academy in Bangalore, India, where he is also the ASI Distinguished Professor of Strategy and International Business.

Partner Center

Join a network of impact. Register your interest today.

Smart. Open. Grounded. Inventive. Read our Ideas Made to Matter.

Which program is right for you?

Through intellectual rigor and experiential learning, this full-time, two-year MBA program develops leaders who make a difference in the world.

A rigorous, hands-on program that prepares adaptive problem solvers for premier finance careers.

A 12-month program focused on applying the tools of modern data science, optimization and machine learning to solve real-world business problems.

Earn your MBA and SM in engineering with this transformative two-year program.

Combine an international MBA with a deep dive into management science. A special opportunity for partner and affiliate schools only.

A doctoral program that produces outstanding scholars who are leading in their fields of research.

Bring a business perspective to your technical and quantitative expertise with a bachelor’s degree in management, business analytics, or finance.

A joint program for mid-career professionals that integrates engineering and systems thinking. Earn your master’s degree in engineering and management.

An interdisciplinary program that combines engineering, management, and design, leading to a master’s degree in engineering and management.

Executive Programs

A full-time MBA program for mid-career leaders eager to dedicate one year of discovery for a lifetime of impact.

This 20-month MBA program equips experienced executives to enhance their impact on their organizations and the world.

Non-degree programs for senior executives and high-potential managers.

A non-degree, customizable program for mid-career professionals.

Navigating the MIT EMBA journey

How the MIT Executive MBA sparked a new inflection point

Finding your flow with the MIT EMBA

MIT Executive MBA

Learning a holistic approach for effective strategy

Ana Escandon, EMBA '19

Aug 12, 2020

Ana Escandon '19

Strategy is important for all companies, yet a common pitfall is not looking at the organization holistically. Often, strategy is biased, taking a narrow view of the company. As a result, the strategy might solve a few problems but may not be transformational at all.

A simple analogy for strategy is picking apples. You pick up the fruit and quickly look at it; you might find a few spots and still decide to buy it, thinking it appears to be healthy. I learned through MIT’s Global Organizations Lab (GO-Lab) that by taking a holistic approach, you can observe and extract additional information that can make strategic decisions, or picking the right apples, more effective. By carefully viewing all sides of the fruit and considering its condition below the surface, you may discover that a simple spot is an indication that the apple is not so healthy after all.

GO-Lab is an international, integrative project of the Executive MBA in which teams are tasked to solve a strategic challenge for a real company. I had the fortune to work alongside an incredible team and a highly invested client. The challenge was to provide strategic guidance to a global organization on whether or not to enter a new business somewhat far from its current capabilities. As I reflected on this experience, it became clear that these three learnings are absolutely critical when it comes to holistic and effective strategy.

Effective strategy is multidisciplinary

When presented with a problem statement, the first step is to “go see and assess” to determine if the stated problem is in fact the real problem. The goal is to identify the actual problem and better understand its cause. Just like the examination of the apple, this means looking at the problem statement from different perspectives.

In the GO-Lab project, this came naturally for our team because we all came from diverse backgrounds, from strategy and R&D to finance and pharma. We asked our client all sorts of questions and requested information from different departments. As a result, we talked with people across the entire organization, gathering data and perceptions from detractors, as well as regions and departments that weren’t obvious internal stakeholders. We also talked to external actors in the client’s ecosystem who could contribute other viewpoints of the organization. We included researchers, universities, and even other companies related to the industry in our interviews.

While it took some time, these discussions gave us a well-rounded idea of the company and its position in the marketplace. Moreover, it revealed that the original problem statement didn’t represent the real problem at stake. Getting to this point was crucial in delivering good results for the project and the client.

Effective strategy is honest

Acknowledging the organization’s capabilities is key. Several times during the project, my teammates would say, “the farther you are from headquarters, the more real it gets.” People at the front line are the ones who experience the true ability of the organization’s capabilities. By detaching from corporate beliefs, you can make more assertive strategic decisions.

Throughout our project, we encountered key people at the company’s headquarters who defined the organization based on past experiences and successes. As a result, the company thought it could enter the new market on its own. From our visits to the company’s sites and talking to frontline employees, we found many gaps in the company’s common knowledge and the new business’ benchmark. When we brought back this information to the client, they were able to be honest with themselves and admit to where they really were in the market. In the end, this honesty enabled them to select a much better strategy to enter the space.

Effective strategy is political

As noted above, problem statements aren’t always accurate. A political lens is helpful to understand the underlying interests of different groups surrounding the problem. Understanding this can help to reduce obstacles in generating commitment towards strategic goals. If you can’t align interests, the organization won’t move towards the desired direction.

As we dug in deeper through the project, we realized that the customer had fundamental interests that weren’t explicit in the problem statement. We had to tap into our political savviness to understand these interests and how they conflicted with the views of other internal stakeholders. Realizing this helped us to frame our proposal in ways that would be more practical for the client to sell their strategy internally.

Applying a holistic approach

The client moved forward with the project, the team graduated, and these learnings lived on for a new purpose. Today, I’m in charge of strategy and business development in my organization and use these GO-Lab learnings to help drive a transformational, strategic agenda for the company.

I follow this holistic approach to include a diversity of people in discussions, learning from their perspectives on the company’s position and understanding conflicting interests in order to move forward. By doing this, I have been able to reveal misconceptions about our capabilities and opportunities, which helped me to take the lead in redesigning our growth strategy for the next five years.

Thanks to this experience, I have changed as a leader and a driver for change. Without coming to MIT, I would never have imagined that something as simple as “picking apples” could deliver transformational results if done well.

Ana Escandon, EMBA '19, is Head of Sales at Citrofrut in Monterrey, Mexico.

Related Posts

Toward a holistic theory of strategic problem solving

827 citations

108 citations

92 citations

View 3 citation excerpts

Cites background or methods from "Toward a holistic theory of strateg..."

... At that time these ideas will be re-assessed and may be utilized or discarded depending on whether they are in-line with the organizational strategy (O’Loughlin and McFadzean, 1999). ...

... The innovation output is monitored and the information obtained from this monitoring is fed-back (O’Loughlin and McFadzean, 1999), and placed in a repository providing inspiration for subsequent Entrepreneurship and innovation 401 ideas (O’Loughlin, 2001). ...

... The innovation output is monitored and the information obtained from this monitoring is fed-back (O’Loughlin and McFadzean, 1999), and placed in a repository providing inspiration for subsequent Entrepreneurship and innovation ...

70 citations

69 citations

View 1 citation excerpt

Additional excerpts

... As useful information is often needed for decision-making process (O’Loughlin and McFadzean 1999; Garcı́a-Meca 2005), constructive information to the stockholders or other stakeholders could help them make informed decisions). ...

10,770 citations

8,897 citations

5,240 citations

4,869 citations

4,117 citations

Related Papers (5)

Ask Copilot

Related papers

Contributing institutions

Related topics

Intuition versus analysis: Strategy and experience in complex everyday problem solving

- Published: April 2008

- Volume 36 , pages 554–566, ( 2008 )

Cite this article

- Jean E. Pretz 1

7139 Accesses

74 Citations

11 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Research on dual processes in cognition has shown that explicit, analytical thought is more powerful and less vulnerable to heuristics and biases than is implicit, intuitive thought. However, several studies have shown that holistic, intuitive processes can outperform analysis, documenting the disruptive effects of hypothesis testing, think-aloud protocols, and analytical judgments. To examine the effects of intuitive versus analytical strategy and level of experience on problem solving, 1st- through 4th-year undergraduates solved problems dealing with college life. The results of two studies showed that the appropriateness of strategy depends on the problem solver’s level of experience. Analysis was found to be an appropriate strategy for more experienced individuals, whereas novices scored best when they took a holistic, intuitive perspective. Similar effects of strategy were found when strategy instruction was manipulated and when participants were compared on the basis of strategy preference. The implications for research on problem solving, expertise, and dual-process models are discussed.

Article PDF

Download to read the full article text

Similar content being viewed by others

Cognitive load theory and educational technology

John Sweller

Decision Making: a Theoretical Review

Matteo Morelli, Maria Casagrande & Giuseppe Forte

Cognitive Architecture and Instructional Design: 20 Years Later

John Sweller, Jeroen J. G. van Merriënboer & Fred Paas

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Abernathy, C. M. , & Hamm, R. M. (1995). Surgical intuition: What it is and how to get it . Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus.

Google Scholar

Ambady, N. , & Rosenthal, R. (1992). Thin slices of expressive behavior as predictors of interpersonal consequences: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin , 111 , 256–274.

Article Google Scholar

Antonakis, J., Hedlund J., Pretz, J. , & Sternberg, R. J. (2002). Exploring the nature and acquisition of tacit knowledge for military leadership (Research Note 2002–04). Alexandria, VA: Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences.

Baylor, A. L. (2001). A U-shaped model for the development of intuition by level of expertise. New Ideas in Psychology , 19 , 237–244.

Berry, D. C. , & Broadbent, D. E. (1988). Interactive tasks and the implicit—explicit distinction. British Journal of Psychology , 79 , 251–272.

Cattell, R. B. , & Cattell, A. K. S. (1961). Test of “g”: Culture fair . Champaign, IL: Institute for Personality and Ability Testing.

Chase, V. M., Hertwig, R. , & Gigerenzer, G. (1998). Visions of rationality. Trends in Cognitive Sciences , 2 , 206–214.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Chi, M. T. H., Feltovich, P. J. , & Glaser, R. (1981). Categorization and representation of physics problems by experts and novices. Cognitive Science , 5 , 121–152.

Chi, M. T. H., Glaser, R. , & Farr, M. J. (1988). The nature of expertise . Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Cianciolo, A. T., Grigorenko, E. L., Jarvin, L., Gil, G., Drebot, M. E. , & Sternberg, R. J. (2006). Practical intelligence and tacit knowledge: Advancements in the measurement of developing expertise. Learning & Individual Differences , 16 , 235–253.

Cianciolo, A. T., Matthew, C., Sternberg, R. J. , & Wagner, R. K. (2006). Tacit knowledge, practical intelligence, and expertise. In K. A. Ericsson, N. Charness, P. J. Feltovich, & R. R. Hoffman (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of expertise and expert performance (pp. 613–632). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Cronbach, L. J. (1957). The two disciplines of scientific psychology. American Psychologist , 12 , 671–684.

Dijksterhuis, A. (2004). Think different: The merits of unconscious thought in preference development and decision making. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology , 87 , 586–598.

Dijksterhuis, A. , & Nordgren, L. F. (2006). A theory of unconscious thought. Perspectives on Psychological Science , 1 , 95–109.

Epstein, S. (1991). Cognitive—experiential self-theory: An integrative theory of personality. In R. C. Curtis (Ed.), The relational self: Theoretical convergences in psychoanalysis and social psychology (pp. 111–137). New York: Guilford.

Epstein, S., Pacini, R., Denes-Raj, V. , & Heier, H. (1996). Individual differences in intuitive—experiential and analytical—rational thinking styles. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology , 71 , 390–405.

Greenwald, A. G. , & Banaji, M. R. (1995). Implicit social cognition: Attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes. Psychological Review , 102 , 4–27.

Hill, O. W. (1987–1988). Intuition: Inferential heuristic or epistemic mode? Imagination, Cognition, & Personality , 7 , 137–154.

Hogarth, R. M. (2001). Educating intuition . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hogarth, R. M. (2005). Deciding analytically or trusting your intuition? The advantages and disadvantages of analytic and intuitive thought. In T. Betsch & S. Haberstroh (Eds.), Routines of decision making (pp. 67–82). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Jung, C. J. (1926). Psychological types . London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Klein, G. (1998). Sources of power: How people make decisions . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Legree, P. J. (1995). Evidence for an oblique social intelligence factor established with a Likert-based testing procedure. Intelligence , 21 , 247–266.

Martinsen, O. (1995). Cognitive styles and experience in solving insight problems: Replication and extension. Creativity Research Journal , 8 , 291–298.

Myers, I., McCaulley, M. H., Quenk, N. L. , & Hammer, A. L. (1998). Manual: A guide to the development and use of the Myers—Briggs Type Indicator (2nd ed.). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

PACE Center (2002). College Student Tacit Knowledge Inventory [Unpublished test].

Pacini, R. , & Epstein, S. (1999). The relation of rational and experiential information processing styles to personality, basic beliefs, and the ratio-bias phenomenon. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology , 76 , 972–987.

Polanyi, M. (1966). The tacit dimension . Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

Pretz, J. E. (2001). Implicit processing aids problem solving: When to incubate ideas and trust intuitions . Unpublished manuscript.

Pretz, J. E., & Zimmerman, C. (2007, August). Rule discovery in the balance task depends on strategy and rule complexity . Poster presented at the 29th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society. Nashville, TN.

Psotka, J. (2003, December). Consensual scaling of informal knowledge . Talk presented at the Abilities and Expertise Seminar Series in the Yale Psychology Department, New Haven, CT.

Raven, J. C., Raven, J. , & Court, J. H. (1985). Mill Hill Vocabulary Scale . San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment.

Reber, A. S. (1989). Implicit learning and tacit knowledge. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General , 118 , 219–235.

Rencher, A. C. (1995). Methods of multivariate analysis . New York: Wiley.

Roediger, H. L. , III (1990). Implicit memory: Retention without remembering. American Psychologist , 45 , 1043–1056.

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action . New York: Basic Books.

Schooler, J. W. , & Melcher, J. (1995). The ineffability of insight. In S. M. Smith (Ed.), Creative cognition approach (pp. 97–133). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Sloman, S. A. (1996). The empirical case for two systems of reasoning. Psychological Bulletin , 119 , 3–22.

Sternberg, R. J. (1988). The triarchic mind . New York: Penguin.

Sternberg, R. J., Forsythe, G. B., Hedlund, J., Horvath, J., Snook, S., Williams, W. M., et al. (2000). Practical intelligence in everyday life . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Sternberg, R. J. , & Weil, E. M. (1980). An aptitude * strategy interaction in linear syllogistic reasoning. Journal of Educational Psychology , 72 , 226–239.

Tulving, E. , & Schacter, D. L. (1990). Priming and human memory systems. Science , 247 , 301–306.

Tversky, A. , & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science , 185 , 1124–1131.

Wilson, T. D. , & Schooler, J. W. (1991). Thinking too much: Introspection can reduce the quality of preferences and decisions. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology , 60 , 181–192.

Wimmers, P. F., Schmidt, H. G., Verkoeijen, P. P. J. L. , & van de Wiel, M. W. J. (2005). Inducing expertise effects in clinical case recall. Medical Education , 39 , 949–957.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, Illinois Wesleyan University, P.O. Box 2900, 61702-2900, Bloomington, IL

Jean E. Pretz

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jean E. Pretz .

Additional information

Study 1 was part of a doctoral dissertation submitted to Yale University. Support for this project was provided by a Yale University Dissertation Fellowship, an APA COGDOP award, and an APA dissertation award.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Pretz, J.E. Intuition versus analysis: Strategy and experience in complex everyday problem solving. Memory & Cognition 36 , 554–566 (2008). https://doi.org/10.3758/MC.36.3.554

Download citation

Received : 12 June 2007

Accepted : 21 September 2007

Issue Date : April 2008

DOI : https://doi.org/10.3758/MC.36.3.554

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Cognitive Style

- Dual Process

- Fluid Intelligence

- Intuitive Condition

- Part Icipants

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous

- Next chapter >

1 An Overview of Strategic Thinking in Complex Problem Solving

- Published: January 2016

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The first chapter, “An overview of strategic thinking in complex problem solving,” gives a general description of the book and introduces the case study that is used in each chapter to exemplify how the tools apply to a practical case. The case study requires no specialized knowledge: a friend’s dog disappears on the very day that the friend dismissed his temperamental housekeeper; did the dog escape or was he kidnapped? The chapter also introduces five key concepts that come at various points along the resolution process: using alternatively divergent and convergent thinking, using issue maps to identify all possible answers to a question exactly once (by using a mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive (MECE) structure), acquiring the right skills, simplifying to reveal the underlying structure of a problem, and not fooling oneself and others.

On a Wednesday afternoon, your cell phone rings. It’s your friend John, and he is frantic: “My dog, Harry, is gone! I came home a few minutes ago and Harry’s not here. I left my house at noon, and when I came back, around four, he was missing. Our house has a backyard with a doggy door in between. This is really strange, because he hasn’t escaped in months—ever since we fixed the gate, he can’t. I think the housekeeper is holding him hostage. I fired her this morning for poor performance. She blamed Harry, saying he sheds too much. She was really upset and threatened to get back at us. He has no collar; how are we going to find him? Also, the yard crew came today to mow the lawn. Anyway, you’re the master problem solver. Help me find him!”

You and I solve countless problems every day, sometimes even without being aware of it. Harry is a real dog, whose disappearance provided me with an opportunity to describe some tools that are universally applicable through a concrete (and true!) case. This book will help you acquire techniques to become better at solving complex problems that you encounter in your personal and professional life, regardless of your occupation, level of education, age, or expertise.

In some cases, these ideas will not apply as well to your own situation, or you may feel that an alternative is better. For instance, one limitation of this technique is that it is time consuming, so it is ill-suited to Grint’s critical problems that require decision-making under tight deadlines. 1 If that’s the case, you may want to cut some corners (more in Chapter 9 ) or use a different route. This is perfectly fine, because this approach is meant to be a modular system of thinking, one that you can adapt to your needs.

This book shows how to structure your problem-solving process using a four-step approach: framing the problem (the what ), diagnosing it (the why ), finding solutions (the how ), and implementing the solution (the do ) (see Figure 1.1 ).

We use a four-step approach to solving problems.

First, identify the problem you should solve (the what ).

Facing a new, unfamiliar situation, we should first understand what the real problem is. This is a deceptively difficult task: We often think we have a good idea of what we need to do and quickly begin to look for solutions only to realize later on that we are solving the wrong problem, perhaps a peripheral one or just a symptom of the main problem. Chapter 2 shows how to avoid this trap by using a rigorous structuring process to identify various problem statements, compare them, and record our decision.

Second, identify why you are having this problem (the why ).

Knowing what the problem is, move to identify its causes. Chapter 3 explains how to identify the diagnostic key question —the one question, formulated with a why root, that encompasses all the other relevant diagnostic questions. I then show how to frame that question, and how to capture the problem in a diagnostic definition card that will guide subsequent efforts.

Next, we will do a root-cause analysis: In Chapter 4 , we will diagnose the problem by first identifying all the possible reasons why we have the problem before focusing on the important one(s). To do that, we will build a diagnosis issue map : a graphical breakdown of the problem that breaks it down into its various dimensions and lays out all the possible causes exactly once. Finally, we will associate concrete hypotheses with specific parts of the map, test these hypotheses, and capture our conclusions.

Third, identify alternative ways to solve the problem (the how ).

Knowing what the problem is and why we have it, we move on to what people commonly think of when talking about problem solving: that is, actively looking for solutions. In Chapter 5 , we will start by formulating a solution key question , this one formulated with a how root, and framing it. Next, we will construct a solution issue map and, mirroring the processes of Chapters 3 and 4 , we will formulate hypotheses for specific branches of the map and test these hypotheses. This will take us to the decision-making stage: selecting the best solutions out of all the possible ones (Chapter 6 ).

Fourth, implement the solution (the do ).

Finally, we will implement the solution, which starts with convincing key stakeholders that our conclusions are right, so Chapter 7 provides guidelines to craft and deliver a compelling message. Then, we will discuss implementation considerations and, in particular, effectively leading teams (Chapter 8 ).

What, Why, How, Do. That’s our process in four words.

In conclusion, Chapter 9 has some ideas for dealing with complications and offers some reflections on the overall approach.

Note that the book’s primary objective is to provide a way to go through the entire problem-solving process, so it presents one tool to achieve each task and discusses that one tool in depth, rather than presenting several alternatives in less detail. 2 Most of these tools and ideas are not mine; they come from numerous academic disciplines and practitioners that provide the conceptual underpinnings for my approach. I have referenced this material as consistently as I could so that the interested reader can review its theoretical and empirical bases. A few ideas are from my own observations, gathered over 15 years of researching these concepts, applying them in managerial settings, and teaching them to students, professionals, and executives.

1. Finding Harry

Let’s pretend that we just received John’s phone call. Many of us would rush into action relying on instinct. This can prove ineffective, however; for example, if the housekeeper is indeed holding Harry hostage, as John thinks, there is little value in searching the neighborhood. Similarly, if Harry has escaped, calling the police to tell them that the housekeeper is keeping him hostage will not help.

So finding Harry starts with understanding the problem and summarizing it in a project definition card, or what card, as Figure 1.2 shows. This is the what part of the process. You may decide that your project is finding Harry, which you want to do in a reasonable time frame, perhaps 72 hours, and that to do so, you first need to understand why he is missing.

A project definition card—or what card—is useful to capture your plan in writing: what you propose to do by when.

Next, you will want to diagnose the problem. This is the why part of the process. Having identified a diagnostic key question—Why is Harry the dog missing?—you can look for all the possible explanations and organize them in a diagnostic issue map, as in Figure 1.3 .

A diagnostic issue map helps identify and organize all the possible root causes of a problem.

When I present this case to students, someone usually dismisses the possibility of Harry being held hostage as ridiculous. This is not as far fetched, however, as it might look: Statistics show that there is such a thing as dognapping, as it is called, and it is actually on the rise. 3 Others also question that someone would hold a dog hostage, but here, too, there is a precedent: In 1934, Harvard students dognapped Yale’s bulldog mascot—Handsome Dan—and held him hostage on the eve of a Yale–Harvard football game. 4

From here, you can formulate formal hypotheses, identify the evidence that you need to obtain to test them, conduct the analysis, and determine the root cause(s) of Harry’s disappearance.

Knowing why Harry is missing, we can now identify alternative ways to get him back. This is the how part of the process. The procedure mirrors our diagnostic approach: We develop a solution definition card, draw an issue map (this time, a solution issue map), formulate hypotheses, identify and gather the evidence necessary to test the hypotheses, and draw conclusions.

This leads us to identify a number of possible ways to look for Harry. Because our resources are limited, we cannot implement all these solutions simultaneously; therefore, we must discard some or, at least, decide in which order we should implement them. To do so, we use a decision tool that considers the various attributes that we want to take into account in our decision and assign each of them a weight. Then, we evaluate the performance of each possible solution with respect to each attribute to develop a ranking, as Table 1.1 shows.

Now that we have identified how we will search for Harry, the strategizing part is over, and it is time to implement our plan. The do part of the process starts by convincing the key decision makers and other stakeholders that we have come to the right conclusions. We then move on to agreeing on who needs to do what by when and then actually doing it. The implementation also includes monitoring the effectiveness of our approach and correcting it as needed.

The case is a real story—although I changed Harry’s name, to protect his privacy—and we did find him after a few hours. This problem is relatively simple and time-constrained; therefore, it does not need the depth of analysis to which we are taking it. It provides a roadmap, however, for solving complex, ill-defined, and nonimmediate problems (CIDNI, pronounced “seed-nee”). As such, we will come back to Harry in each chapter to illustrate how the concepts apply in a concrete example.

2. Solving Complex, Ill-defined, and Nonimmediate Problems

A problem can be defined as a difference between a current state and a goal state. 5 Problem solving , the resolution of such a difference, is omnipresent in our lives in diverse forms, from executing simple tasks—say, choosing what socks to wear on a given day—to tackling complex, long-term projects, such as curing cancer. This book is about solving the latter: the complex, ill-defined, and nonimmediate problems.

Complex means that the problem’s current and goal states, along with obstacles encountered along the way, are diverse, dynamic during their resolution, interdependent, and/or not transparent. 6 Ill-defined problems have unclear initial and final conditions and paths to the solution. 7 They usually do not have one “right” solution; 8 in fact, they may not have any solution at all. 9 They usually are one of a kind. 10 Finally, nonimmediate means that the solver has some time, at least a few days or weeks, to identify and implement a solution. At the organizational level, a CIDNI problem for a company may be to develop its marketing strategy. On a global scale, CIDNI problems include ensuring environmental sustainability, reducing extreme poverty and hunger, achieving universal primary education, and all the other United Nations’ Millennium Development Goals. 11

A fundamental characteristic of CIDNI problems is that, because they are ill-defined, their solutions are at least partly subjective. Indeed, appropriate solutions depend on your knowledge and values, and what may be the best solution for you may not be for someone else. 12 Another implication is that the problem-solving process is only roughly linear. Despite our best efforts to define the problem at the onset of the project, new information surfacing during the resolution may prompt us to modify that definition later on. In fact, such regression to a previous step may happen at any point along the resolution process. 13

Think about what makes your problem CIDNI.

Problems can be challenging for various reasons, and understanding these may help you choose a direction in which to look for a solution. Some problems are complex because they are computationally intensive. A chess player, for instance, cannot think of all alternatives—and all the opponent’s replies—until late in the game, when the universe of possibilities is much reduced. Chess, however, is a fairly well-defined environment.

Contrast this with opening a hotel in a small village in the Caribbean and discovering that obtaining a license will require bribing local officials. The challenge here is not computational, but the problem is ill-defined in important ways: Do you still want to carry out the project if bribery is a requirement? If you want to avoid bribing officials, how can you do so successfully? And so on.

Indeed, ill definition stems in many ways when human interactions are part of the picture. Consider the case of a graduate student ready to defend her dissertation only to discover that two key members of her jury have just had a bitter argument and cannot sit in the same room for more than five minutes without fighting. How should she proceed?