Definition of Biography

A biography is the non- fiction , written history or account of a person’s life. Biographies are intended to give an objective portrayal of a person, written in the third person. Biographers collect information from the subject (if he/she is available), acquaintances of the subject, or in researching other sources such as reference material, experts, records, diaries, interviews, etc. Most biographers intend to present the life story of a person and establish the context of their story for the reader, whether in terms of history and/or the present day. In turn, the reader can be reasonably assured that the information presented about the biographical subject is as true and authentic as possible.

Biographies can be written about a person at any time, no matter if they are living or dead. However, there are limitations to biography as a literary device. Even if the subject is involved in the biographical process, the biographer is restricted in terms of access to the subject’s thoughts or feelings.

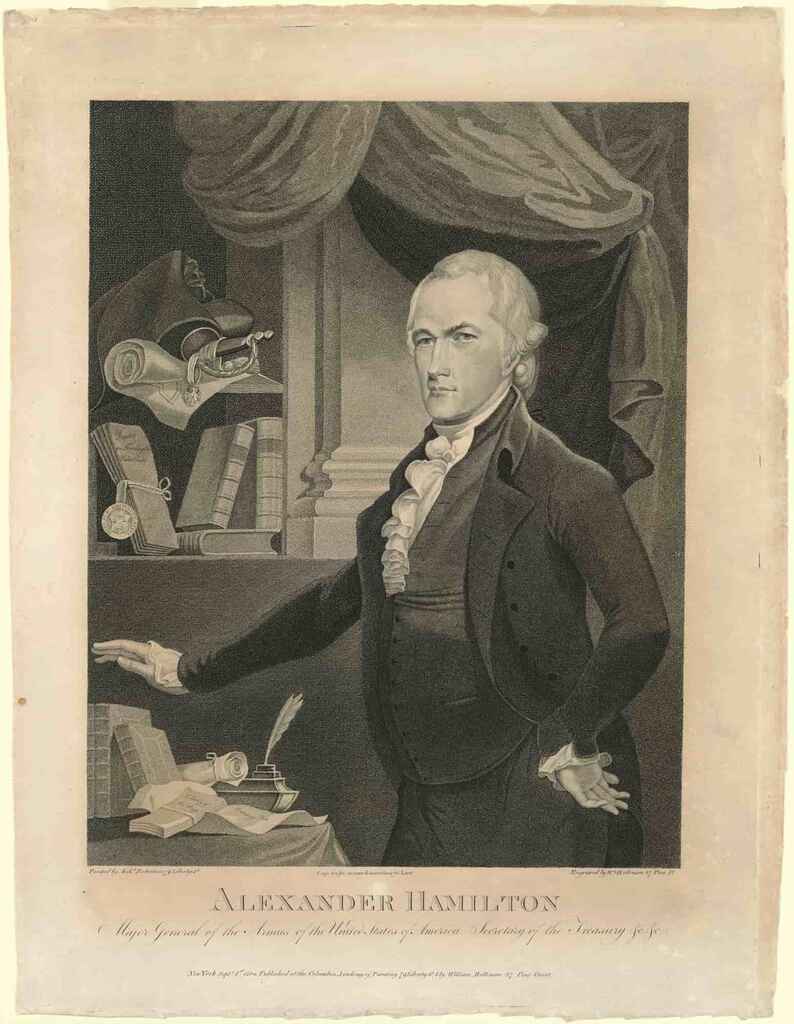

Biographical works typically include details of significant events that shape the life of the subject as well as information about their childhood, education, career, and relationships. Occasionally, a biography is made into another form of art such as a film or dramatic production. The musical production of “Hamilton” is an excellent example of a biographical work that has been turned into one of the most popular musical productions in Broadway history.

Common Examples of Biographical Subjects

Most people assume that the subject of a biography must be a person who is famous in some way. However, that’s not always the case. In general, biographical subjects tend to be interesting people who have pioneered something in their field of expertise or done something extraordinary for humanity. In addition, biographical subjects can be people who have experienced something unusual or heartbreaking, committed terrible acts, or who are especially gifted and/or talented.

As a literary device, biography is important because it allows readers to learn about someone’s story and history. This can be enlightening, inspiring, and meaningful in creating connections. Here are some common examples of biographical subjects:

- political leaders

- entrepreneurs

- historical figures

- serial killers

- notorious people

- political activists

- adventurers/explorers

- religious leaders

- military leaders

- cultural figures

Famous Examples of Biographical Works

The readership for biography tends to be those who enjoy learning about a certain person’s life or overall field related to the person. In addition, some readers enjoy the literary form of biography independent of the subject. Some biographical works become well-known due to either the person’s story or the way the work is written, gaining a readership of people who may not otherwise choose to read biography or are unfamiliar with its form.

Here are some famous examples of biographical works that are familiar to many readers outside of biography fans:

- Alexander Hamilton (Ron Chernow)

- Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder (Caroline Fraser)

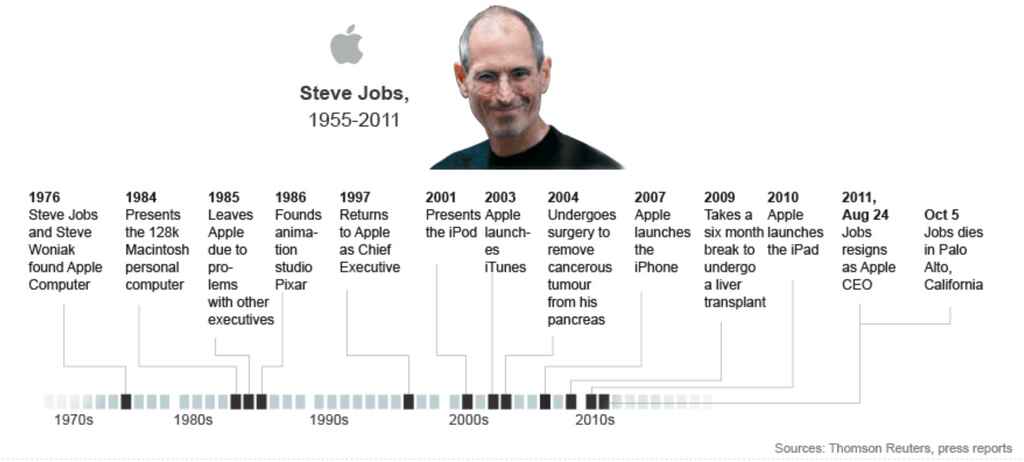

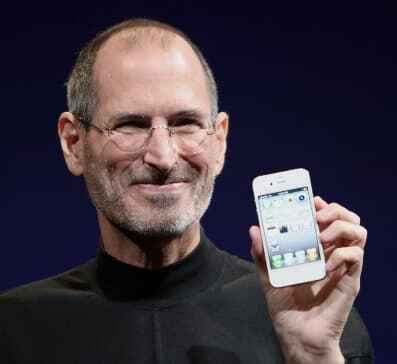

- Steve Jobs (Walter Isaacson)

- Churchill: A Life (Martin Gilbert)

- The Professor and the Madman: A Tale of Murder, Insanity, and the Making of the Oxford English Dictionary (Simon Winchester)

- A Beautiful Mind (Sylvia Nasar)

- The Black Rose (Tananarive Due)

- John Adams (David McCullough)

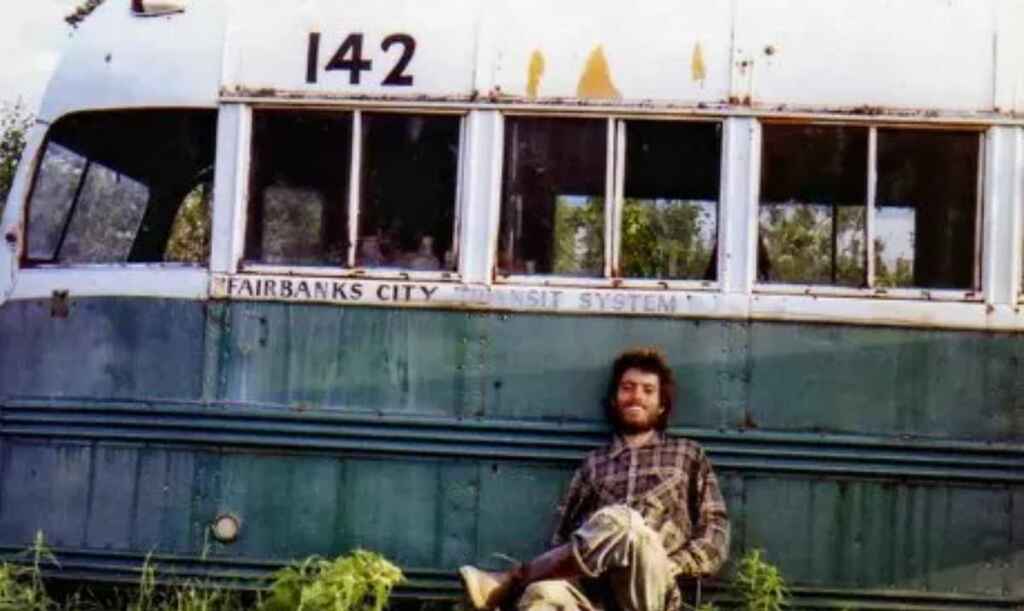

- Into the Wild ( Jon Krakauer )

- John Brown (W.E.B. Du Bois)

- Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo (Hayden Herrera)

- The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks (Rebecca Skloot)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln (Doris Kearns Goodwin)

- Shirley Jackson : A Rather Haunted Life ( Ruth Franklin)

- the stranger in the Woods: The Extraordinary Story of the Last True Hermit (Michael Finkel)

Difference Between Biography, Autobiography, and Memoir

Biography, autobiography , and memoir are the three main forms used to tell the story of a person’s life. Though there are similarities between these forms, they have distinct differences in terms of the writing, style , and purpose.

A biography is an informational narrative and account of the life history of an individual person, written by someone who is not the subject of the biography. An autobiography is the story of an individual’s life, written by that individual. In general, an autobiography is presented chronologically with a focus on key events in the person’s life. Since the writer is the subject of an autobiography, it’s written in the first person and considered more subjective than objective, like a biography. In addition, autobiographies are often written late in the person’s life to present their life experiences, challenges, achievements, viewpoints, etc., across time.

Memoir refers to a written collection of a person’s significant memories, written by that person. Memoir doesn’t generally include biographical information or chronological events unless it’s relevant to the story being presented. The purpose of memoir is reflection and an intention to share a meaningful story as a means of creating an emotional connection with the reader. Memoirs are often presented in a narrative style that is both entertaining and thought-provoking.

Examples of Biography in Literature

An important subset of biography is literary biography. A literary biography applies biographical study and form to the lives of artists and writers. This poses some complications for writers of literary biographies in that they must balance the representation of the biographical subject, the artist or writer, as well as aspects of the subject’s literary works. This balance can be difficult to achieve in terms of judicious interpretation of biographical elements within an author’s literary work and consideration of the separate spheres of the artist and their art.

Literary biographies of artists and writers are among some of the most interesting biographical works. These biographies can also be very influential for readers, not only in terms of understanding the artist or writer’s personal story but the context of their work or literature as well. Here are some examples of well-known literary biographies:

Example 1: Savage Beauty: The Life of Edna St. Vincent Millay (Nancy Milford)

One of the first things Vincent explained to Norma was that there was a certain freedom of language in the Village that mustn’t shock her. It wasn’t vulgar. ‘So we sat darning socks on Waverly Place and practiced the use of profanity as we stitched. Needle in, . Needle out, piss. Needle in, . Needle out, c. Until we were easy with the words.’

This passage reflects the way in which Milford is able to characterize St. Vincent Millay as a person interacting with her sister. Even avid readers of a writer’s work are often unaware of the artist’s private and personal natures, separate from their literature and art. Milford reflects the balance required on the part of a literary biographer of telling the writer’s life story without undermining or interfering with the meaning and understanding of the literature produced by the writer. Though biographical information can provide some influence and context for a writer’s literary subjects, style, and choices , there is a distinction between the fictional world created by a writer and the writer’s “real” world. However, a literary biographer can illuminate the writer’s story so that the reader of both the biography and the biographical subject’s literature finds greater meaning and significance.

Example 2: The Invisible Woman: The Story of Nelly Ternan and Charles Dickens (Claire Tomalin)

The season of domestic goodwill and festivity must have posed a problem to all good Victorian family men with more than one family to take care of, particularly when there were two lots of children to receive the demonstrations of paternal love.

Tomalin’s literary biography of Charles Dickens reveals the writer’s extramarital relationship with a woman named Nelly Ternan. Tomalin presents the complications that resulted for Dickens from this relationship in terms of his personal and family life as well as his professional writing and literary work. Revealing information such as an extramarital relationship can influence the way a reader may feel about the subject as a person, and in the case of literary biography it can influence the way readers feel about the subject’s literature as well. Artists and writers who are beloved , such as Charles Dickens, are often idealized by their devoted readers and society itself. However, as Tomalin’s biography of Dickens indicates, artists and writers are complicated and as subject to human failings as anyone else.

Example 3: Virginia Woolf (Hermione Lee)

‘A self that goes on changing is a self that goes on living’: so too with the biography of that self. And just as lives don’t stay still, so life-writing can’t be fixed and finalised. Our ideas are shifting about what can be said, our knowledge of human character is changing. The biographer has to pioneer, going ‘ahead of the rest of us, like the miner’s canary, testing the atmosphere , detecting falsity, unreality, and the presence of obsolete conventions’. So, ‘There are some stories which have to be retold by each generation’. She is talking about the story of Shelley, but she could be talking about her own life-story.

In this passage, Lee is able to demonstrate what her biographical subject, Virginia Woolf, felt about biography and a person telling their own or another person’s story. Literary biographies of well-known writers can be especially difficult to navigate in that both the author and biographical subject are writers, but completely separate and different people. As referenced in this passage by Lee, Woolf was aware of the subtleties and fluidity present in a person’s life which can be difficult to judiciously and effectively relay to a reader on the part of a biographer. In addition, Woolf offers insight into the fact that biographers must make choices in terms of what information is presented to the reader and the context in which it is offered, making them a “miner’s canary” as to how history will view and remember the biographical subject.

Post navigation

- Daily Crossword

- Word Puzzle

- Word Finder

Word of the Day

- Synonym of the Day

- Word of the Year

- Language stories

- All featured

- Gender and sexuality

- All pop culture

- Grammar Coach ™

- Writing hub

- Grammar essentials

- Commonly confused

- All writing tips

- Pop culture

- Writing tips

Advertisement

[ bahy- og -r uh -fee , bee- ]

the biography of Byron by Marchand.

- an account in biographical form of an organization, society, theater, animal, etc.

- such writings collectively.

- the writing of biography as an occupation or field of endeavor.

/ ˌbaɪəˈɡræfɪkəl; baɪˈɒɡrəfɪ /

- an account of a person's life by another

- such accounts collectively

- The story of someone's life. The Life of Samuel Johnson , by James Boswell , and Abraham Lincoln , by Carl Sandburg , are two noted biographies. The story of the writer's own life is an autobiography .

Discover More

Derived forms.

- biographical , adjective

- ˌbioˈgraphically , adverb

- biˈographer , noun

Word History and Origins

Origin of biography 1

Example Sentences

Barrett didn’t say anything on Tuesday to contradict our understanding of her ideological leanings based on her past rulings, past statements and biography.

Republicans, meanwhile, focused mostly on her biography — including her role as a working mother of seven and her Catholic faith — and her credentials, while offering few specifics about her record as a law professor and judge.

She delivered an inspiring biography at one point, reflecting on the sacrifice her mother made to emigrate to the United States.

As Walter Isaacson pointed out in his biography of Benjamin Franklin, Franklin proposed the postal system as a vital network to bond together the 13 disparate colonies.

Serving that end, the book is not an in-depth biography as much as a summary of Galileo’s life and science, plus a thorough recounting of the events leading up to his famous trial.

The Amazon biography for an author named Papa Faal mentions both Gambia and lists a military record that matches the FBI report.

For those unfamiliar with Michals, an annotated biography and useful essays are included.

Did you envision your Pryor biography as extending your previous investigation—aesthetically and historically?

But Stephen Kotkin's new biography reveals a learned despot who acted cunningly to take advantage of the times.

Watching novelists insult one another is one of the primary pleasures of his biography.

He also published two volumes of American Biography, a work which his death abridged.

Mme. de Chaulieu gave her husband the three children designated in the duc's biography.

The biography of great men always has been, and always will be read with interest and profit.

I like biography far better than fiction myself: fiction is too free.

The Bookman: "A more entertaining narrative whether in biography or fiction has not appeared in recent years."

Related Words

- autobiography

[ ak -s uh -lot-l ]

Start each day with the Word of the Day in your inbox!

By clicking "Sign Up", you are accepting Dictionary.com Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policies.

What Is a Biography?

Learning from the experiences of others is what makes us human.

At the core of every biography is the story of someone’s humanity. While biographies come in many sub-genres, the one thing they all have in common is loyalty to the facts, as they’re available at the time. Here’s how we define biography, a look at its origins, and some popular types.

“Biography” Definition

A biography is simply the story of a real person’s life. It could be about a person who is still alive, someone who lived centuries ago, someone who is globally famous, an unsung hero forgotten by history, or even a unique group of people. The facts of their life, from birth to death (or the present day of the author), are included with life-changing moments often taking center stage. The author usually points to the subject’s childhood, coming-of-age events, relationships, failures, and successes in order to create a well-rounded description of her subject.

Biographies require a great deal of research. Sources of information could be as direct as an interview with the subject providing their own interpretation of their life’s events. When writing about people who are no longer with us, biographers look for primary sources left behind by the subject and, if possible, interviews with friends or family. Historical biographers may also include accounts from other experts who have studied their subject.

The biographer’s ultimate goal is to recreate the world their subject lived in and describe how they functioned within it. Did they change their world? Did their world change them? Did they transcend the time in which they lived? Why or why not? And how? These universal life lessons are what make biographies such a meaningful read.

Origins of the Biography

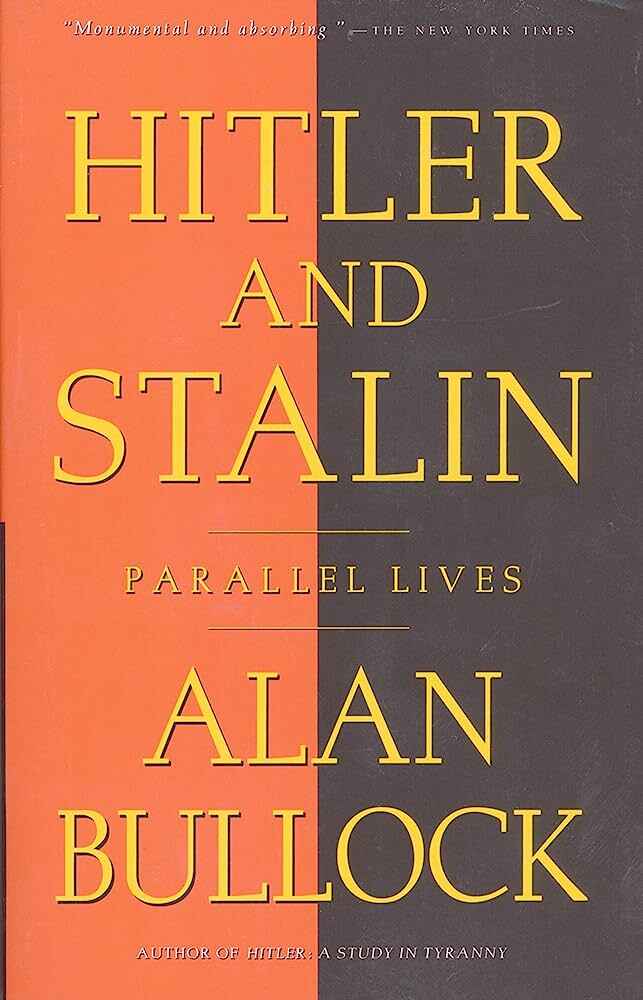

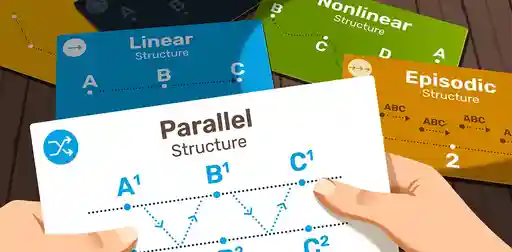

Greco-Roman literature honored the gods as well as notable mortals. Whether winning or losing, their behaviors were to be copied or seen as cautionary tales. One of the earliest examples written exclusively about humans is Plutarch’s Parallel Lives (probably early 2 nd century AD). It’s a collection of biographies in which a pair of men, one Greek and one Roman, are compared and held up as either a good or bad example to follow.

In the Middle Ages, Einhard’s The Life of Charlemagne (around 817 AD) stands out as one of the most famous biographies of its day. Einhard clearly fawns over Charlemagne’s accomplishments throughout, yet it doesn’t diminish the value this biography has brought to centuries of historians since its writing.

Considered the earliest modern biography, The Life of Samuel Johnson (1791) by James Boswell looks like the biographies we know today. Boswell conducted interviews, performed years of research, and created a compelling narrative of his subject.

The genre evolves as the 20th century arrives, and with it the first World War. The 1920s saw a boom in autobiographies in response. Robert Graves’ Good-Bye to All That (1929) is a coming-of age story set amid the absurdity of war and its aftermath. That same year, Mahatma Gandhi wrote The Story of My Experiments with Truth , recalling how the events of his life led him to develop his theories of nonviolent rebellion. In this time, celebrity tell-alls also emerged as a popular form of entertainment. With the horrors of World War II and the explosion of the civil rights movement, American biographers of the late 20 th century had much to archive. Instantly hailed as some of the best writing about the war, John Hersey’s Hiroshima (1946) tells the stories of six people who lived through those world-altering days. Alex Haley wrote the as-told-to The Autobiography of Malcom X (1965). Yet with biographies, the more things change, the more they stay the same. One theme that persists is a biographer’s desire to cast its subject in an updated light, as in Eleanor and Hick: The Love Affair that Shaped a First Lady by Susan Quinn (2016).

Types of Biographies

Contemporary Biography: Authorized or Unauthorized

The typical modern biography tells the life of someone still alive, or who has recently passed. Sometimes these are authorized — written with permission or input from the subject or their family — like Dave Itzkoff’s intimate look at the life and career of Robin Williams, Robin . Unauthorized biographies of living people run the risk of being controversial. Kitty Kelley’s infamous His Way: The Unauthorized Biography of Frank Sinatra so angered Sinatra, he tried to prevent its publication.

Historical Biography

The wild success of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton is proof that our interest in historical biography is as strong as ever. Miranda was inspired to write the musical after reading Ron Chernow’s Alexander Hamilton , an epic 800+ page biography intended to cement Hamilton’s status as a great American. Paula Gunn Allen also sets the record straight on another misunderstood historical figure with Pocahontas: Medicine Woman, Spy, Entrepreneur, Diplomat , revealing details about her tribe, her family, and her relationship with John Smith that are usually missing from other accounts. Historical biographies also give the spotlight to people who died without ever getting the recognition they deserved, such as The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks .

Biography of a Group

When a group of people share unique characteristics, they can be the topic of a collective biography. The earliest example of this is Captain Charles Johnson’s A General History of the Pirates (1724), which catalogs the lives of notorious pirates and establishes the popular culture images we still associate with them. Smaller groups are also deserving of a biography, as seen in David Hajdu’s Positively 4th Street , a mesmerizing behind-the-scenes look at the early years of Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Mimi Baez Fariña, and Richard Fariña as they establish the folk scene in New York City. Likewise, British royal family fashion is a vehicle for telling the life stories of four iconic royals – Queen Elizabeth II, Diana, Kate, and Meghan – in HRH: So Many Thoughts on Royal Style by style journalist Elizabeth Holmes.

Autobiography

This type of biography is written about one’s self, spanning an entire life up to the point of its writing. One of the earliest autobiographies is Saint Augustine’s The Confessions (400), in which his own experiences from childhood through his religious conversion are told in order to create a sweeping guide to life. Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings is the first of six autobiographies that share all the pain of her childhood and the long road that led to her work in the civil rights movement, and a beloved, prize-winning writer.

Memoirs are a type of autobiography, written about a specific but vital aspect of one’s life. In Toil & Trouble , Augusten Burroughs explains how he has lived his life as a witch. Mikel Jollett’s Hollywood Park recounts his early years spent in a cult, his family’s escape, and his rise to success with his band, The Airborne Toxic Event. Barack Obama’s first presidential memoir, A Promised Land , charts his path into politics and takes a deep dive into his first four years in office.

Fictional Biography

Fictional biographies are no substitute for a painstakingly researched scholarly biography, but they’re definitely meant to be more entertaining. Z: A Novel of Zelda Fitzgerald by Therese Anne Fowler constructs Zelda and F. Scott’s wild, Jazz-Age life, told from Zelda’s point of view. The Only Woman in the Room by Marie Benedict brings readers into the secret life of Hollywood actress and wartime scientist, Hedy Lamarr. These imagined biographies, while often whimsical, still respect the form in that they depend heavily on facts when creating setting, plot, and characters.

Share with your friends

Related articles.

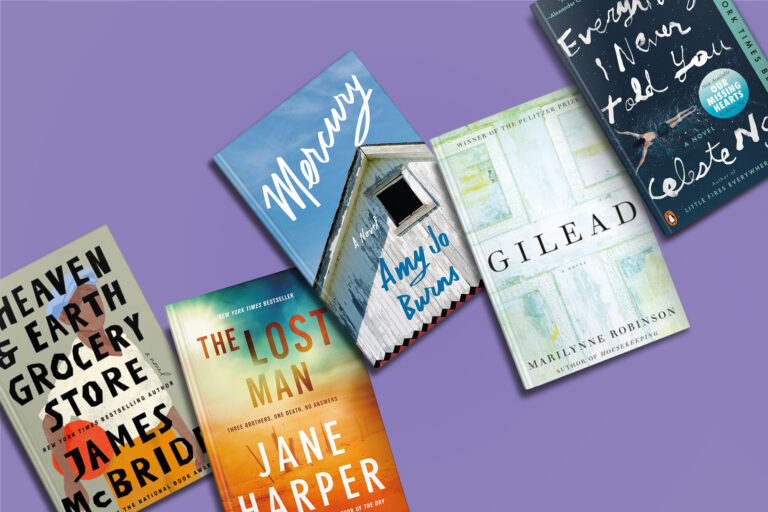

10 Evocative Literary Fiction Books Set in Small Towns

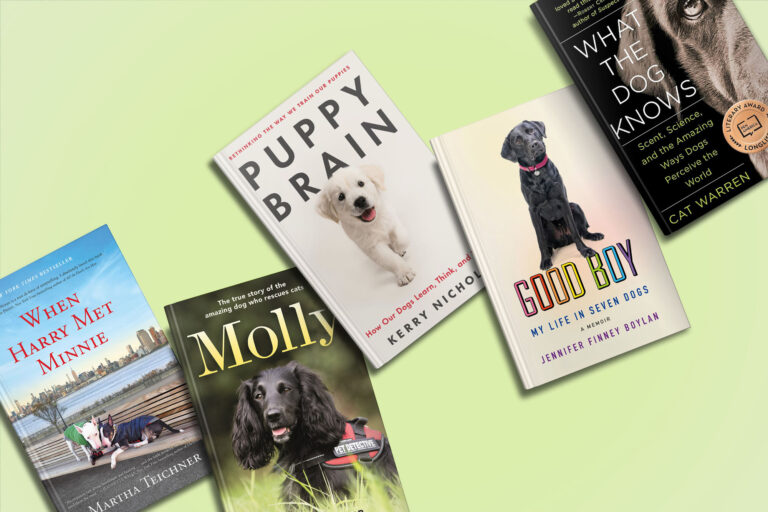

11 Must-Read Books About Dogs

What We’re Reading: Spring 2024

Celadon delivered.

Subscribe to get articles about writing, adding to your TBR pile, and simply content we feel is worth sharing. And yes, also sign up to be the first to hear about giveaways, our acquisitions, and exclusives!

" * " indicates required fields

Connect with

Sign up for our newsletter to see book giveaways, news, and more.

What Is Biography? Definition, Usage, and Literary Examples

Biography definition.

A biography (BYE-og-ruh-fee) is a written account of one person’s life authored by another person. A biography includes all pertinent details from the subject’s life, typically arranged in a chronological order. The word biography stems from the Latin biographia , which succinctly explains the word’s definition: bios = “life” + graphia = “write.”

Since the advent of the written word, historical writings have offered information about real people, but it wasn’t until the 18th century that biographies evolved into a separate literary genre. Autobiographies and memoirs fall under the broader biography genre, but they are distinct literary forms due to one key factor: the subjects themselves write these works. Biographies are popular source materials for documentaries, television shows, and motion pictures.

The History of Biographies

The biography form has its roots in Ancient Rome and Greece. In 44 BCE, Roman writer Cornelius Nepos published Excellentium Imperatorum Vitae ( Lives of the Generals ), one of the earliest recorded biographies. In 80 CE, Greek writer Plutarch released Parallel Lives , a sweeping work consisting of 48 biographies of famous men. In 121 CE, Roman historian Suetonius wrote De vita Caesarum ( On the Lives of the Caesars ), a series of 12 biographies detailing the lives of Julius Caesar and the first 11 emperors of the Roman Empire. These were among the most widely read biographies of their time, and at least portions of them have survived intact over the millennia.

During the Middle Ages, the Roman Catholic Church had a notable influence on biographies. Historical, political, and cultural biographies fell out of favor. Biographies of religious figures—including saints, popes, and church founders—replaced them. One notable exception was Italian painter/architect Giorgio Vasari’s 1550 biography, The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects , which was immensely popular. In fact, it is one of the first examples of a bestselling book.

Still, it wasn’t until the 18th century that authors began to abandon multiple subjects in a single work and instead focus their research and writing on one subject. Scholars consider James Boswell’s 1791 The Life of Samuel Johnson to be the first modern biography. From here, biographies were established as a distinct literary genre, separate from more general historical writing.

As understanding of psychology and sociology grew in the 19th and early 20th centuries, biographies further evolved, offering up even more comprehensive pictures of their subjects. Authors who played major roles in this contemporary approach to biographing include Lytton Strachey, Gamaliel Bradford, and Robert Graves.

Types of Biographies

While all biographical works chronicle the lives of real people, writers can present the information in several different ways.

- Popular biographies are life histories written for a general readership. The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot and Into the Wild by Jon Krakauer are two popular examples.

- Critical biographies discuss the relationship between the subject’s life and the work they produced or were involved in; for example, The Billionaire Who Wasn’t: How Chuck Feeney Secretly Made and Gave Away a Fortune by Conor O’Clery and Unpresidented: A Biography of Donald Trump by Martha Brockenbrough.

- Historical biographies put greater understanding on how the subject’s life and contributions affected or were affected by the times in which they lived; see John Adams by David McCullough and Catherine the Great by Peter K. Massie.

- Literary biographies concentrate almost exclusively on writers and artists, blending a conventional narrative of the historical facts of the subject’s life with an exploration of how these facts impacted their creative output. Some examples include Savage Beauty: The Life of Edna St. Vincent Millay by Nancy Milford and Jackson Pollock: An American Saga by Gregory White Smith and Steven Naifeh.

- Reference biographies are more scholarly writings, usually written by multiple authors and covering multiple lives around a single topic. They verify facts, provide background details, and contribute supplemental information resources, like bibliographies, glossaries, and historical documents; for example, Black Americans in Congress, 1870-2007 and the Dictionary of Canadian Biography .

- Fictional biographies, or biographical novels, like The Other Boleyn Girl by Philippa Gregory, incorporate creative license into the retelling of a real person’s story by taking on the structure and freedoms of a novel. The term can also describe novels in which authors give an abundance of background information on their characters, to the extent that the novel reads more like a biography than fiction. An example of this is George R.R. Martin’s Fire and Blood , a novel detailing the history of a royal family from his popular A Song of Ice and Fire

Biographies and Filmed Entertainment

Movie makers and television creators frequently produce biographical stories, either as dramatized productions based on real people or as nonfiction accounts.

Documentary

This genre is a nonfictional movie or television show that uses historical records to tell the story of a subject. The subject might be a one person or a group of people, or it might be a certain topic or theme. To present a biography in a visually compelling way, documentaries utilize archival footage, recreations, and interviews with subjects, scholars, experts, and others associated with the subject.

Famous film documentaries include Grey Gardens, a biography of two of Jacqueline Kennedy’s once-wealthy cousins, who, at the time of filming, lived in squalor in a condemned mansion in the Hamptons; and I Am Not Your Negro , a biography of the life and legacy of pioneering American author James Baldwin.

Television documentary series tell one story over the course of several episodes, like The Jinx : The Life and Deaths of Robert Durst , a biography of the real estate heir and alleged serial killer that focused on his suspected crimes. There are many nonfiction television shows that use a documentary format, but subjects typically change from one episode to the next, such as A&E’s Biography and PBS’s POV .

These films are biographical motion pictures, written by screenwriters and performed by actors. They often employ a certain amount of creative liberty in their interpretation of a real life. This is largely done to maintain a feasible runtime; capturing all of the pivotal moments of a subject’s life in a 90- or 120-minute movie is all but impossible. So, filmmakers might choose to add, eliminate, or combine key events and characters, or they may focus primarily on one or only a few aspects of the subject’s life. Some popular examples: Coal Miner’s Daughter , a biography of country music legend Loretta Lynn; Malcom X , a biopic centered on the civil rights leader of the same name; and The King’s Speech , a dramatization of Prince Albert’s efforts to overcome a stutter and ascend the English throne.

Semi-fictionalized account

This approach takes a real-life event and interprets or expands it in ways that stray beyond what actually happened. This is done for entertainment and to build the story so it fits the filmmaker’s vision or evolves into a longer form, such as a multi-season television show. These accounts sometimes come with the disclaimer that they are “inspired by true events.” Examples of semi-fictionalized accounts are the TV series Orange Is the New Black , Masters of Sex , and Mozart of the Jungle —each of which stem from at least one biographical element, but showrunners expounded upon to provide many seasons of entertainment.

The Functions of Biography

Biographies inform readers about the life of a notable person. They are a way to introduce readers to the work’s subject—the historical details, the subject’s motivations and psychological underpinnings, and their environment and the impact they had, both in the short and long term.

Because the author is somewhat removed from their subject, they can offer a more omniscient, third-person narrative account. This vantage point allows the author to put certain events into a larger context; compare and contrast events, people, and behaviors predominant in the subject’s life; and delve into psychological and sociological themes of which the subject may not have been aware.

Also, a writer structures a biography to make the life of the subject interesting and readable. Most biographers want to entertain as well as inform, so they typically use a traditional plot structure—an introduction, conflict , rising of tension, a climax, a resolution, and an ending—to give the life story a narrative shape. While the ebb and flow of life is a normal day-to-day rhythm, it doesn’t necessarily make for entertaining reading. The job of the writer, then, becomes one of shaping the life to fit the elements of a good plot.

Writers Known for Biographies

Many modern writers have dedicated much of their careers to biographies, such as:

- Kitty Kelley, author of Jackie Oh! An Intimate Biography; His Way: The Unauthorized Biography of Frank Sinatra ; and The Family: The Real Story of the Bush Dynasty

- Antonia Fraser, author of Mary Queen of Scots ; Cromwell; Our Chief of Men ; and The Gunpowder Plot: Terror and Faith in 1605

- David McCullough, author of The Path Between the Seas; Truman ; and John Adams

- Andrew Morton, author of Diana: Her True Story in Her Own Words; Madonna ; and Tom Cruise: An Unauthorized Biography

- Alison Weir, author of The Six Wives of Henry VIII; Eleanor of Aquitaine: By the Wrath of God; Queen of England ; and Katherine Swynford: The Story of John of Gaunt and His Scandalous Duchess

Examples of Biographies

1. James Boswell, The Life of Samuel Johnson

The biography that ushered in the modern era of true-life writing, The Life of Samuel Johnson covered the entirety of its subject’s life, from his birth to his status as England’s preeminent writer to his death. Boswell was a personal acquaintance of Johnson, so he was able to draw on voluminous amounts of personal conversations the two shared.

What also sets this biography apart is, because Boswell was a contemporary of Johnson, readers see Johnson in the context of his own time. He wasn’t some fabled figure that a biographer was writing about centuries later; he was someone to whom the author had access, and Boswell could see the real-world influence his subject had on life in the here and now.

2. Sylvia Nasar, A Beautiful Mind

Nasar’s 1998 Pulitzer Prize-nominated biography of mathematician John Nash introduced legions of readers to Nash’s remarkable life and genius. The book opens with Nash’s childhood and follows him through his education, career, personal life, and struggles with schizophrenia. It ends with his acceptance of the 1994 Nobel Prize for Economics. In addition to a Pulitzer nomination, A Beautiful Mind won the National Book Critics Circle Award for Biography, was a New York Times bestseller, and provided the basis for the Academy Award-winning 2001 film of the same name.

3. Catherine Clinton, Harriet Tubman: The Road to Freedom

Clinton’s biography of the abolitionist icon is a large-scale epic that chronicles Tubman’s singular life. It starts at her birth in the 1820s as the slave Araminta Ross, continuing through her journey to freedom; her pivotal role in the Underground Railroad; her Moses-like persona; and her death in 1913.

Because Tubman could not read or write, she left behind no letters, diaries, or other personal papers in her own hand and voice. Clinton reconstructed Tubman’s history entirely through other source material, and historians often cite this work as the quintessential biography of Tubman’s life.

4. Megan Mayhew Bergman, Almost Famous Women

Almost Famous Women is not a biography in the strictest sense of the word; it is a fictional interpretation of real-life women. Each short story revolves around a woman from history with close ties to fame, such as movie star Marlene Dietrich, Standard Oil heiress Marion “Joe” Carstairs, aviatrix Beryl Markham, Oscar Wilde’s niece Dolly, and Lord Byron’s daughter Allegra. Mayhew Bergman imagines these colorful women in equally colorful episodes that put them in a new light—a light that perhaps offers them the honor and homage that history denied them.

Further Resources on Biography

Newsweek compiled their picks for the 75 Best Biographies of All Time .

The Open Education Database has a list of 75 Biographies to Read Before You Die .

Goodreads put together a list of readers’ best biography selections .

If you’re looking to write biographies, Infoplease has instructions for writing shorter pieces, while The Writer has practical advice for writing manuscript-length bios.

Ranker collected a comprehensive list of famous biographers .

Related Terms

- Autobiography

- Short Story

- Dictionaries home

- American English

- Collocations

- German-English

- Grammar home

- Practical English Usage

- Learn & Practise Grammar (Beta)

- Word Lists home

- My Word Lists

- Recent additions

- Resources home

- Text Checker

Definition of biography noun from the Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary

- Boswell’s biography of Johnson

- a biography by Antonia Fraser

- The book gives potted biographies of all the major painters.

- blockbuster

- unauthorized

- biography by

- biography of

Want to learn more?

Find out which words work together and produce more natural-sounding English with the Oxford Collocations Dictionary app. Try it for free as part of the Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary app.

Written by Nicole Ahlering

Have you found yourself browsing the biography section of your favorite library or bookstore and wondered what is a biography book ?

Don’t worry, we’ve got you covered!

In this brief guide, we’ll explore the definition of a biography, along with its purpose, how you might write one yourself, and more. Let’s get started.

Need A Nonfiction Book Outline?

In this article, we'll explore:

What is a biography of a person .

A biography is simply a written account of someone’s life. It is written by someone other than whom the book is about. For example, an author named Walter Isaacson has written biographies on Steve Jobs , Leonardo da Vinci , and Einstein .

Biographies usually focus on the significant events that occurred in a person’s life, along with their achievements, challenges they’ve overcome, background, relationships, and more.

They’re an excellent way to get a comprehensive understanding of someone you admire.

What is the point of a biography?

Biographies have a few purposes. They can serve as historical records about a notable figure, inspire and educate readers, and give us more insight into how the folks we’re interested in lived their lives.

They can also be valuable research resources for people studying a notable figure, like Einstein!

Does a biography cover someone’s entire life?

Biographies typically encompass most of a person’s life. Obviously, if the subject of the book is still alive, their entire life cannot be written about.

If the person lived a long and eventful life with many achievements, the author may cover only an especially noteworthy period of the subject’s life.

Even so, the point of a biography is to learn about your subject beyond just what they achieved, so there will likely still be contextual information about the subject’s childhood, formative experiences, and more.

Is a biography always nonfiction?

Surprisingly, a biography is not always nonfiction . There is a genre called biographical fiction in which the author uses real-life people and events to inspire their fictional narrative .

This genre is fun because the author can postulate about what their subject may have been thinking, feeling, and more in a way they may not be able to with a nonfiction biography.

Just keep in mind that biographical fiction blends facts with made-up information, so it can’t be used as a primary research source. That said, it’s a fun supplement to learning about a figure you’re interested in, and can help generate curiosity and insights about their lives.

If you’d like to read a biographical fiction book, check out books like:

- The Paris Wife by Paula McLain

- The Other Boleyn Girl by Philippa Gregory

- The Aviator’s Wife by Melanie Benjamin

Why would someone write a biography?

An author may want to write a biography about someone because they’re inspired by them and want to educate the public about them. Or, they want to create a historical resource for scholars to study.

An author may even have a commercial motivation for writing a biography, like a lucrative celebrity profile or a biography that has the potential to be adapted into a film or television series.

Is it possible to write a biography about yourself?

If you write a book about yourself, it’s called an autobiography or a memoir—not a biography. So, when you start writing your book, make sure you don't get caught in the autobiography vs biography or biography vs memoir maze.

If you’d like a book written about you that you’re not the author of, you can hire a writer to create one for you. You may choose to do this if you feel your writing skills are not up to par or you don’t have time to write your own biography .

Hiring a writer to write your biography can also make sense if you’d like to make sure the book is as objective and professional as it can be. Of course, this means you have to surrender control of the narrative!

Some folks may also feel that a biography has more credence than an autobiography or memoir since the book’s subject doesn’t get to decide what is said about them. So hiring a writer for your biography can be a good way to credibly get your story out there.

Can you write a biography about anyone you’d like?

When it comes to writing about other people’s lives, it’s wise to proceed with an abundance of caution. After all, you don’t want to be sued for defamation or find yourself in other legal hot water.

We highly suggest you look into the legal ramifications of writing about your chosen subject before you begin writing about them, but here are a couple of general things to know:

- Typically, you don’t need permission to write about someone who is a public figure. However, the definition of a public figure can vary depending on your jurisdiction and more, so you’ll need to do your research.

- Even if you discover that you can write about your subject without permission, it’s still advisable to contact the subject and or their family. Not only is it good manners, but it may afford you some insider information about your subject.

- If your subject or the family of your subject tells you they don’t want a biography about them, you may still legally be able to proceed—consult a lawyer—but you might face backlash when the book is published, limited access to information about your subject, and perhaps a pressing sense of guilt. Not worth it, if you ask us!

Examples of biographies

Ready to get started reading biographies? Here are a few of the best biographies you should add to your list:

- Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo by Hayden Herrera

- Heavier Than Heaven: A Biography of Kurt Cobain by Charles R. Cross

- Anne Frank: The Biography by Melissa Müller

- You Never Forget Your First: A Biography of George Washington by Alexis Coe

- The Beatles: The Biography by Bob Spitz

- Victoria the Queen: An Intimate Biography of the Woman Who Ruled an Empire by Julia Baird

Final thoughts

Reading a biography is a great way to get inspired, learn from other people’s experiences, and more. And writing a biography can be an excellent educational experience in its own right! If you’d like to publish a biography but don’t know where to start, we’re here to help. Simply schedule a book consultation to get started.

Related posts

Business, Marketing, Writing

Amazon Book Marketing: How to Do Amazon Ads

Writing, Fiction

How to Write a Novel: 15 Steps from Brainstorm to Bestseller

An author’s guide to 22 types of tones in writing.

Biographies: The Stories of Humanity

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

A biography is a story of a person's life, written by another author. The writer of a biography is called a biographer while the person written about is known as the subject or biographee.

Biographies usually take the form of a narrative , proceeding chronologically through the stages of a person's life. American author Cynthia Ozick notes in her essay "Justice (Again) to Edith Wharton" that a good biography is like a novel, wherein it believes in the idea of a life as "a triumphal or tragic story with a shape, a story that begins at birth, moves on to a middle part, and ends with the death of the protagonist."

A biographical essay is a comparatively short work of nonfiction about certain aspects of a person's life. By necessity, this sort of essay is much more selective than a full-length biography, usually focusing only on key experiences and events in the subject's life.

Between History and Fiction

Perhaps because of this novel-like form, biographies fit squarely between written history and fiction, wherein the author often uses personal flairs and must invent details "filling in the gaps" of the story of a person's life that can't be gleaned from first-hand or available documentation like home movies, photographs, and written accounts.

Some critics of the form argue it does a disservice to both history and fiction, going so far as to call them "unwanted offspring, which has brought a great embarrassment to them both," as Michael Holroyd puts it in his book "Works on Paper: The Craft of Biography and Autobiography." Nabokov even called biographers "psycho-plagiarists," meaning that they steal the psychology of a person and transcribe it to the written form.

Biographies are distinct from creative non-fiction such as memoir in that biographies are specifically about one person's full life story -- from birth to death -- while creative non-fiction is allowed to focus on a variety of subjects, or in the case of memoirs certain aspects of an individual's life.

Writing a Biography

For writers who want to pen another person's life story, there are a few ways to spot potential weaknesses, starting with making sure proper and ample research has been conducted -- pulling resources such as newspaper clippings, other academic publications, and recovered documents and found footage.

First and foremost, it is the duty of biographers to avoid misrepresenting the subject as well as acknowledging the research sources they used. Writers should, therefore, avoid presenting a personal bias for or against the subject as being objective is key to conveying the person's life story in full detail.

Perhaps because of this, John F. Parker observes in his essay "Writing: Process to Product" that some people find writing a biographical essay "easier than writing an autobiographical essay. Often it takes less effort to write about others than to reveal ourselves." In other words, in order to tell the full story, even the bad decisions and scandals have to make the page in order to truly be authentic.

- An Introduction to Literary Nonfiction

- How to Define Autobiography

- A Profile in Composition

- What Is a Novel? Definition and Characteristics

- Biography of Salman Rushdie, Master of the Modern Allegorical Novel

- 10 Contemporary Biographies, Autobiographies, and Memoirs for Teens

- Stream of Consciousness Writing

- Biography of William Golding, British Novelist

- Biography of Louise Erdrich, Native American Author

- Biography of Marge Piercy, Feminist Novelist and Poet

- Genres in Literature

- What Is the Definition of Passing for White?

- What Is an Autobiography?

- Organizational Strategies for Using Chronological Order in Writing

What is biography?

by Professor Dame Hermione Lee FBA

What is biography? A big fat book about a dead person, you might reply. A book with lots of dates and some pictures and chapters going chronologically from cradle to grave. A book about a single person’s life and work, but probably with a great deal, too, about their family and friends, relations and children, colleagues and acquaintances.

The word ‘biography’ means ‘life-writing’: the two halves of the word derive from medieval Greek bios , ‘life’, and graphia , ‘writing’. Dictionary definitions give you “the history of the lives of individual men, as a branch of literature”, or “a written record of the life of an individual” ( Oxford English Dictionary , 1971), or, more up-to-date and succinct, “An account of someone’s life written by someone else” ( New Oxford Dictionary of English, 2001). Essentially, it’s the written story of another person’s life.

The word started to be used, in western literature, in the late 18th century, but biography reaches far back through histories and cultures to all kinds of older forms: the ancient Sumerian epic of Gilgamesh, full of conflict and adventure; classical and Egyptian lives of rulers and illustrious heroes, with warning stories of triumphs turning to disaster and decline; venerating biographies of Tibetan Buddhist leaders or medieval Christian saints, showing you how best to live under the eye of God. Mainly, biography used to be the Lives of Great Men (and less often, women), written to give you something to live up to or learn from. But it’s become a more democratic form of writing. ‘Lives’ can be written of ‘ordinary’ people as well as kings and saints.

And there have come to be many different kinds of biographical narratives. It doesn’t have to be the written story of a dead person. Biography can take the form of a film or a poem, an obituary or an opera. It can be about a living subject, or a group, or a city, or a river, or an animal. You can start at the end, with a death-bed, or tell the story of one year in a life. Biography often goes back to a famous life-story that’s been told before – think of Van Gogh, Nelson Mandela, Keats, Sylvia Plath, or Mahatma Gandhi – so it can be a form of revision. Virginia Woolf said: “There are some stories which have to be retold by each generation”.

It might be easier to say what it’s not, than what it is. It is supposed to be true and factual: so it isn’t fiction. (Though biography is capable of making things up or missing things out). It is supposed to be objective and not written in the first person: so it isn’t autobiography. (But all biographers write out of their own point of view, race, class, gender and time, so complete objectivity is never possible). It is about an individual or individuals: so it isn’t history. (But history, inevitably, plays a part). It tries to analyse character and motives: but biographers aren’t usually psychologists or psychoanalysts (though they have sometimes pretended to be). It follows clues, tries to unpick secrets and often needs to rely on witnesses: but it isn’t quite the same as a detective story or a thriller. There isn’t always a murder, though some critics of biography feel that it can be the next thing to it: a well-known quotation says that “biography adds a new terror to death”.

A more interesting question about biography might be, not “what is it?” but “what is it for?” or “why does it matter”? Is it for learning lessons, or bringing history alive, or providing information about the sources and circumstances of a person’s work? All of the above. But more than that, biography takes us beyond ourselves, into the experience of a life that’s not our own. It expands our knowledge of life and widens our boundaries. It makes us imagine and understand what it’s like to be somebody else. That’s why it matters.

Dame Hermione Lee is Emeritus Professor of English Literature at the University of Oxford. Her works include biographies of Virginia Woolf , Edith Wharton and Penelope Fitzgerald . Her biography of Tom Stoppard will be published by Faber on 1 October 2020. She was elected a Fellow of the British Academy in 2001.

Related blogs

What are the digital humanities?

What is musicology?

What is Islamic studies?

Sign up to our email newsletters, preferences.

Yes, I wish to receive regular emails from the British Academy about the work of the organisation which may include news, reports, publications, research, affiliate organisations, engagement, projects, funding, fundraising and events.

Literary Devices

Literary devices, terms, and elements, definition of biography.

A biography is a description of a real person’s life, including factual details as well as stories from the person’s life. Biographies usually include information about the subject’s personality and motivations, and other kinds of intimate details excluded in a general overview or profile of a person’s life. The vast majority of biography examples are written about people who are or were famous, such as politicians, actors, athletes, and so on. However, some biographies can be written about people who lived incredible lives, but were not necessarily well-known. A biography can be labelled “authorized” if the person being written about, or his or her family members, have given permission for a certain author to write the biography.

The word biography comes from the Greek words bios , meaning “life” and – graphia , meaning “writing.”

Difference Between Biography and Autobiography

A biography is a description of a life that is not the author’s own, while an autobiography is the description of a writer’s own life. There can be some gray area, however, in the definition of biography when a ghostwriter is employed. A ghostwriter is an author who helps in the creation of a book, either collaborating with someone else or doing all of the writing him- or herself. Some famous people ask for the help of a ghostwriter to create their own autobiographies if they are not particularly gifted at writing but want the story to sound like it’s coming from their own mouths. In the case of a ghostwritten autobiography, the writer is not actually writing about his or her own life, but has enough input from the subject to create a work that is very close to the person’s experience.

Common Examples of Biography

The genre of biography is so popular that there is even a cable network originally devoted to telling the stories of famous people’s lives (fittingly called The Biography Channel). The stories proved to be such good television that other networks caught on, such as VH1 producing biographies under the series name “Behind the Music.” Some examples of written biographies have become famous in their own right, such as the following books:

- Alexander Hamilton by Ron Chernow (made even more famous by the musical “Hamilton,” created by Lin-Manuel Miranda)

- Unbroken by Laura Hillenbrand

- Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson

- Into the Wild by Jon Krakauer

- The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot

- Mountains Beyond Mountains: The Quest of Dr. Paul Farmer, A Man Who Would Cure the World by Tracy Kidder

- Three Cups of Tea: One Man’s Mission to Promote Peace … One School at a Time by Greg Mortenson

Significance of Biography in Literature

The genre of biography developed out of other forms of historical nonfiction, choosing to focus on one specific person’s experience rather than all important players. There are examples of biography all the way back to 44 B.C. when Roman biographer Cornelius Nepos wrote Excellentium Imperatorum Vitae (“Lives of those capable of commanding”). The Greek historian Plutarch was also famous for his biographies, creating a series of biographies of famous Greeks and Romans in his book Parallel Lives . After the printing press was created, one of the first “bestsellers” was the 1550 famous biography Lives of the Artists by Giorgio Vasari. Biography then got very popular in the 18th century with James Boswell’s 1791 publication of The Life of Samuel Johnson . Biography continues to be one of the best selling genres in literature, and has led to a number of literary prizes specifically for this form.

Examples of Biography in Literature

And I can imagine Farmer saying he doesn’t care if no one else is willing to follow their example. He’s still going to make these hikes, he’d insist, because if you say that seven hours is too long to walk for two families of patients, you’re saying that their lives matter less than some others’, and the idea that some lives matter less is the root of all that’s wrong with the world.

( Mountains Beyond Mountains: The Quest of Dr. Paul Farmer, A Man Who Would Cure the World by Tracy Kidder)

Tracy Kidder’s wonderful example of biography, Mountains Beyond Mountains , brought the work of Dr. Paul Farmer to a wider audience. Dr. Farmer cofounded the organization Partners in Health (PIH) in 1987 to provide free treatment to patients in Haiti; the organization later created similar projects in countries such as Russia, Peru, and Rwanda. Dr. Farmer was not necessarily a famous man before Tracy Kidder’s biography was published, though he was well-regarded in his own field. The biography describes Farmer’s work as well as some of his personal life.

On July 2, McCandless finished reading Tolstoy’s “Family Happiness”, having marked several passages that moved him: “He was right in saying that the only certain happiness in life is to live for others…” Then, on July 3, he shouldered his backpack and began the twenty-mile hike to the improved road. Two days later, halfway there, he arrived in heavy rain at the beaver ponds that blocked access to the west bank of the Teklanika River. In April they’d been frozen over and hadn’t presented an obstacle. Now he must have been alarmed to find a three-acre lake covering the trail.

( Into the Wild by Jon Krakauer)

Jon Krakauer is a writer and outdoorsman famous for many nonfiction books, including his own experience in a mountaineering disaster on Mount Everest in 1996. His book Into the Wild is a nonfiction biography of a young boy, Christopher McCandless who chose to donate all of his money and go into the wilderness in the American West. McCandless starved to death in Denali National Park in 1992. The biography delved into the facts surrounding McCandless’s death, as well as incorporating some of Krakauer’s own experience.

A commanding woman versed in politics, diplomacy, and governance; fluent in nine languages; silver-tongued and charismatic, Cleopatra nonetheless seems the joint creation of Roman propagandists and Hollywood directors.

( Cleopatra: A Life by Stacy Schiff)

Stacy Schiff wrote a new biography of Cleopatra in 2010 in order to divide fact from fiction, and go back to the amazing and intriguing personality of the woman herself. The biography was very well received for being both scrupulously referenced as well as highly literary and imaginative.

Confident that he was clever, resourceful, and bold enough to escape any predicament, [Louie] was almost incapable of discouragement. When history carried him into war, this resilient optimism would define him.

( Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience, and Redemption by Laura Hillenbrand)

Laura Hillenbrand’s bestselling biography Unbroken covers the life of Louis “Louie” Zamperini, who lived through almost unbelievable circumstances, including running in the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin, being shot down as a bomber in WWII, surviving in a raft in the ocean for 47 days, and then surviving Japanese prisoner of war camps. Zamperini’s life story is one of those narratives that is “stranger than fiction” and Hillenbrand brings the drama brilliantly to the reader.

I remember sitting in his backyard in his garden, one day, and he started talking about God. He [Jobs] said, “ Sometimes I believe in God, sometimes I don’t. I think it’s 50/50, maybe. But ever since I’ve had cancer, I’ve been thinking about it more, and I find myself believing a bit more, maybe it’s because I want to believe in an afterlife, that when you die, it doesn’t just all disappear. The wisdom you’ve accumulated, somehow it lives on.”

( Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson)

Steve Jobs is one of the most famous cultural icons of modern-day America and, indeed, around the world, and thus his biography was eagerly awaited. The author, Walter Isaacson, was able to interview Jobs extensively during the writing process. Thus, the above excerpt is possible where the writer is a character in the story himself, asking Jobs about his views on life and philosophy of the world.

Test Your Knowledge of Biography

1. Which of the following statements is the best biography definition? A. A retelling of one small moment from another person’s life. B. A novel which details one specific character’s full life. C. A description of a real person’s entire life, written by someone else.

2. Which of the following scenarios qualifies as a biography? A. A famous person contracts a ghostwriter to create an autobiography. B. A famous author writes the true and incredible life story of a little known person. C. A writer creates a book detailing the most important moments in her own life.

3. Which of the following statements is true? A. Biographies are one of the best selling genres in contemporary literature. B. Biographies are always written about famous people. C. Biographies were first written in the 18th century.

What Is a Biography? Definition & 25+ Examples

Have you ever wondered what lies beneath the surface of history’s most influential figures?

Imagine a chance to delve into the intricate tapestry of their lives, unraveling the threads that have woven together the very essence of their character, and unearthing the pivotal moments that shaped their destinies.

Welcome to the enthralling world of biographies, where you are invited to embark on a captivating journey into the lives of the extraordinary. Prepare to be captivated by the compelling tales of human resilience, ingenuity, and ambition that lie at the heart of each biography.

Table of Contents

Defining Biography

A biography is a detailed account of a person’s life, written by someone other than the subject. The term “biography” is derived from two Greek words: “bio,” which means life, and “graphy,” which signifies writing. Thus, a biography is the written history of someone’s life, offering an in-depth look at their experiences, achievements, and challenges.

Biographies typically focus on the life of notable individuals, such as historical figures or celebrities, and provide a comprehensive view of their personal and professional journey.

Biographers, the authors of these works, aim to offer an accurate, well-researched portrayal of their subjects by studying various sources and conducting interviews if possible. This thorough research and attention to detail ensure that the resulting narrative is both informative and engaging.

Biographies are a subgenre of non-fiction literature, as they chronicle the lives of real people. However, not all life stories fall under the category of biography.

Autobiographies and memoirs, for instance, focus on the author’s own experiences and are written from a first-person perspective. While autobiographies aim to present an overarching narrative of the author’s life, memoirs tend to focus on specific incidents or periods.

When crafting a biography, it is essential for the biographer to maintain a neutral tone, avoiding any judgment or personal bias. This objectivity allows readers to form their opinions based on the presented facts, gaining a broader understanding of the subject.

Elements of a Biography

A well-crafted biography contains several key elements that provide a comprehensive picture of the subject’s life. These elements help readers gain a deeper understanding of the subject while fostering an emotional connection. Below are some essential aspects of a biography:

Personal and Family Background

The personal and family background section of a biography provides an essential foundation for understanding the subject’s journey and the factors that shaped their life. By exploring the subject’s early years, readers gain insight into the environment and experiences that influenced their character, values, and aspirations.

This section typically begins with an overview of the subject’s birthplace, family origins, and cultural heritage. It delves into the family dynamics, including descriptions of the subject’s parents, siblings, and extended family, shedding light on the relationships that played a crucial role in their development.

The personal and family background section also addresses significant life events, challenges, and milestones that occurred during the subject’s upbringing. These formative experiences may include pivotal moments, such as moving to a new city, attending a particular school, or encountering a mentor who had a lasting impact on their life.

Education and Career

The education and career section of a biography is crucial for understanding the intellectual and professional development of the subject. By tracing the subject’s academic journey and career progression, readers gain a clearer picture of the knowledge, skills, and experiences that shaped their path and contributed to their success.

This section begins by outlining the subject’s educational background, including the schools they attended, the degrees or qualifications they obtained, and any specialized training they received. It also highlights the subject’s academic achievements, such as scholarships, awards, or distinctions, and any influential mentors or teachers who played a significant role in their intellectual growth.

The education and career section also delves into the subject’s professional life, chronicling their work history, job titles, and key responsibilities. It explores the subject’s career trajectory, examining how they transitioned between roles or industries and the factors that influenced their choices.

Major Events and Turning Points

The major events and turning points section of a biography delves into the pivotal moments and experiences that significantly influenced the subject’s life, shaping their character, values, and destiny.

By exploring these transformative events, readers gain a deeper understanding of the forces and circumstances that drove the subject’s actions and choices, as well as the challenges and triumphs they faced along the way.

This section encompasses a wide range of events, which could include personal milestones, such as marriage, the birth of children, or the loss of a loved one.

These personal events often provide insights into the subject’s emotional landscape and reveal the support systems, relationships, and personal values that sustained them through difficult times or propelled them to greater heights.

Influences and Inspirations

The influences and inspirations section of a biography delves into the individuals, ideas, and events that had a profound impact on the subject’s beliefs, values, and aspirations.

By understanding the forces that shaped the subject’s worldview, readers gain a deeper appreciation for the motivations driving their actions and decisions, as well as the creative and intellectual foundations upon which their accomplishments were built.

This section often begins by identifying the key figures who played a significant role in the subject’s life, such as family members, mentors, peers, or historical figures they admired.

It explores the nature of these relationships and how they shaped the subject’s perspectives, values, and ambitions. These influential individuals can provide valuable insights into the subject’s personal growth and development, revealing the sources of inspiration and guidance that fueled their journey.

The influences and inspirations section also delves into the ideas and philosophies that resonated with the subject and shaped their worldview. This could include an exploration of the subject’s religious, political, or philosophical beliefs, as well as the books, theories, or artistic movements that inspired them.

This section examines the events, both personal and historical, that impacted the subject’s life and inspired their actions. These could include moments of personal transformation, such as a life-altering experience or an epiphany, or broader societal events, such as wars, social movements, or technological innovations.

Contributions and Impact

The contributions and impact section of a biography is pivotal in conveying the subject’s lasting significance, both in their chosen profession and beyond. By detailing their achievements, innovations, and legacies, this section helps readers grasp the extent of the subject’s influence and the ways in which their work has shaped the world around them.

This section begins by highlighting the subject’s key accomplishments within their profession, such as breakthroughs, discoveries, or innovative techniques they developed. It delves into the processes and challenges they faced along the way, providing valuable insights into their creativity, determination, and problem-solving abilities.

The contributions and impact section also explores the subject’s broader influence on society, culture, or the world at large. This could include their involvement in social or political movements, their philanthropic endeavors, or their role as a cultural icon.

In addition to discussing the subject’s immediate impact, this section also considers their lasting legacy, exploring how their work has continued to inspire and shape subsequent generations.

This could involve examining the subject’s influence on their successors, the institutions or organizations they helped establish, or the enduring relevance of their ideas and achievements in contemporary society.

Personal Traits and Characteristics

The personal traits and characteristics section of a biography brings the subject to life, offering readers an intimate glimpse into their personality, qualities, and views.

This section often begins by outlining the subject’s defining personality traits, such as their temperament, values, and passions. By exploring these attributes, readers gain insight into the subject’s character and the motivations driving their actions and decisions.

These qualities could include their perseverance, curiosity, empathy, or sense of humor, which may help explain their achievements, relationships, and outlook on life.

The personal traits and characteristics section also delves into the subject’s views and beliefs, offering a window into their thoughts and opinions on various topics. This could include their perspectives on politics, religion, culture, or social issues, providing readers with a clearer understanding of the context in which they operated and the factors that shaped their worldview.

Anecdotes and personal stories play a crucial role in illustrating the subject’s personality and characteristics, as they offer concrete examples of their behavior, actions, or interactions with others.

Quotes and first-hand accounts from the subject or those who knew them well can also be invaluable in portraying their personal traits and characteristics. These accounts offer unique insights into the subject’s thoughts, feelings, and experiences, allowing readers to see the world through their eyes and better understand their character.

Types of Biographies

Biographies come in various forms and styles, each presenting unique perspectives on the lives of individuals. Some of the most common types of biographies are discussed in the following sub-sections.

Historical Fiction Biography

Historical fiction biographies artfully weave together factual information with imaginative elements, creating a vibrant tapestry of the past. By staying true to the core of a historical figure’s life and accomplishments, these works offer a unique window into their world while granting authors the creative freedom to delve deeper into their emotions, relationships, and personal struggles.

Such biographies strike a delicate balance, ensuring that the essence of the individual remains intact while allowing for fictional embellishments to bring their story to life. This captivating blend of fact and fiction serves to humanize these iconic figures, making their experiences more relatable and engaging for readers who embark on a journey through the pages of history.

Here are several examples of notable historical fiction biographies:

- “Wolf Hall” by Hilary Mantel (2009)

- “The Paris Wife” by Paula McLain (2011)

- “Girl with a Pearl Earring” by Tracy Chevalier (1999)

- “The Other Boleyn Girl” by Philippa Gregory (2001)

- “Loving Frank” by Nancy Horan (2007)

Academic Biography

Academic biographies stand as meticulously researched and carefully crafted scholarly works, dedicated to presenting an accurate and comprehensive account of a subject’s life.

Authored by experts or researchers well-versed in their field, these biographies adhere to rigorous standards of accuracy, sourcing, and objectivity. They delve into the intricacies of a person’s life, achievements, and impact, scrutinizing every aspect with scholarly precision.

Intended for an educated audience, academic biographies serve as valuable resources for those seeking a deeper understanding of the subject’s contributions and influence. By placing the individual within the broader context of their time, these works illuminate the complex web of factors that shaped their lives and legacies.

While academic biographies may not always carry the same narrative flair as their fictional counterparts, their commitment to factual integrity and thorough analysis make them indispensable resources for scholars, students, and enthusiasts alike

Here are several examples of notable academic biographies:

- “Einstein: His Life and Universe” by Walter Isaacson (2007)

- “Steve Jobs” by Walter Isaacson (2011)

- “John Adams” by David McCullough (2001)

- “Alexander the Great” by Robin Lane Fox (1973)

- “Marie Curie: A Life” by Susan Quinn (1995)

Authorized Biographies

Authorized biographies offer a unique perspective on the lives of their subjects, as they are written with the explicit consent and, often, active participation of the individual in question.

This collaboration between the biographer and the subject can lead to a more accurate, detailed, and intimate portrayal of the person’s life, as the author is granted access to a wealth of personal information, documents, and anecdotes that might otherwise be inaccessible.

When working on an authorized biography, the biographer is typically given permission to access personal documents, such as letters, diaries, and photographs, which can provide invaluable insights into the subject’s thoughts, emotions, and experiences.

This primary source material allows the biographer to construct a narrative that is grounded in fact and captures the essence of the individual’s life and personality.

Here are several examples of notable authorized biographies:

- “Mandela: The Authorized Biography” by Anthony Sampson (1999)

- “Marilyn Monroe: The Biography” by Donald Spoto (1993)

- “Joni Mitchell: In Her Own Words” by Malka Marom (2014)

- “The Snowball: Warren Buffett and the Business of Life” by Alice Schroeder (2008)

- “Notorious RBG: The Life and Times of Ruth Bader Ginsburg” by Irin Carmon and Shana Knizhnik (2015)

Fictionalized Academic Biography

Fictionalized academic biographies merge the best of both worlds, combining the rigorous research and scholarly integrity of academic biographies with the engaging storytelling of historical fiction.

Authors of these works expertly navigate the delicate balance between maintaining factual accuracy and venturing into the realm of imagination.

This approach allows them to explore the subject’s personal life, relationships, and the broader historical context in a compelling manner, while ensuring the narrative remains firmly rooted in well-researched facts.

Here are several examples of notable fictionalized academic biographies:

- “The Women” by T.C. Boyle (2009)

- “Z: A Novel of Zelda Fitzgerald” by Therese Anne Fowler (2013)

- “The Marriage of Opposites” by Alice Hoffman (2015)

- “Vanessa and Her Sister” by Priya Parmar (2014)

- “The Last Days of Night” by Graham Moore (2016)

Prophetic Biography

Prophetic biographies delve into the rich and profound narratives of religious figures or prophets, meticulously weaving together insights from sacred texts, religious traditions, and historical accounts.

By providing a comprehensive portrayal of the individual’s life, teachings, and impact on society, these biographies serve as an invaluable resource for understanding the pivotal role these figures played in shaping the course of religious history and the lives of the faithful.

Here are several examples of notable prophetic biographies:

- “Muhammad: His Life Based on the Earliest Sources” by Martin Lings (1983)

- “The Life of Moses” by F.B. Meyer (1893)

- “The Life of the Buddha: According to the Pali Canon” by Bhikkhu Ñāṇamoli (1972)

- “The Quest of the Historical Jesus” by Albert Schweitzer (1906)

- “The Lives of the Saints” by Alban Butler (1756)

Biography Development Process

A biography is a comprehensive written account of an individual’s life, and the development process involves several essential components to ensure the biography’s accuracy and readability.

A biographer’s primary responsibility is to conduct extensive research in order to gather a comprehensive array of facts about the subject. This meticulous process involves reviewing various documents and sources that shed light on the individual’s life and experiences, as well as the historical context in which they lived.

Key documents, such as birth and death certificates, provide essential information about the subject’s origins and family background. Personal correspondence, letters, and diaries offer invaluable insights into the subject’s thoughts, emotions, relationships, and experiences. News articles, on the other hand, can reveal public perceptions of the subject, as well as their impact on society and culture.

Archives often serve as treasure troves of information for biographers, as they contain a wealth of primary sources that can help illuminate the subject’s life and times. These archives may include collections of personal papers, photographs, audio recordings, and other materials that offer first-hand accounts of the individual’s experiences or shed light on their accomplishments and impact.

Consulting relevant books and articles is another crucial aspect of a biographer’s research process, as these secondary sources provide context, analysis, and interpretation of the subject’s life and work.

By delving into the existing scholarship and engaging with the works of other researchers, biographers can solidify their understanding of the individual and the historical circumstances in which they lived.

Interviewing people who knew the subject personally is a vital component of a biographer’s research process, as it allows them to access unique insights, personal stories, and firsthand accounts of the individual’s life.

Friends, family members, co-workers, and colleagues can all offer valuable perspectives on the subject’s character, relationships, achievements, and challenges, thereby enriching the biographer’s understanding of their life and experiences.