Critical Thinking Definition, Skills, and Examples

- Homework Help

- Private School

- College Admissions

- College Life

- Graduate School

- Business School

- Distance Learning

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/ADHeadshot-Cropped-b80e40469d5b4852a68f94ad69d6e8bd.jpg)

- Indiana University, Bloomington

- State University of New York at Oneonta

Critical thinking refers to the ability to analyze information objectively and make a reasoned judgment. It involves the evaluation of sources, such as data, facts, observable phenomena, and research findings.

Good critical thinkers can draw reasonable conclusions from a set of information, and discriminate between useful and less useful details to solve problems or make decisions. These skills are especially helpful at school and in the workplace, where employers prioritize the ability to think critically. Find out why and see how you can demonstrate that you have this ability.

Examples of Critical Thinking

The circumstances that demand critical thinking vary from industry to industry. Some examples include:

- A triage nurse analyzes the cases at hand and decides the order by which the patients should be treated.

- A plumber evaluates the materials that would best suit a particular job.

- An attorney reviews the evidence and devises a strategy to win a case or to decide whether to settle out of court.

- A manager analyzes customer feedback forms and uses this information to develop a customer service training session for employees.

Why Do Employers Value Critical Thinking Skills?

Employers want job candidates who can evaluate a situation using logical thought and offer the best solution.

Someone with critical thinking skills can be trusted to make decisions independently, and will not need constant handholding.

Hiring a critical thinker means that micromanaging won't be required. Critical thinking abilities are among the most sought-after skills in almost every industry and workplace. You can demonstrate critical thinking by using related keywords in your resume and cover letter and during your interview.

How to Demonstrate Critical Thinking in a Job Search

If critical thinking is a key phrase in the job listings you are applying for, be sure to emphasize your critical thinking skills throughout your job search.

Add Keywords to Your Resume

You can use critical thinking keywords (analytical, problem solving, creativity, etc.) in your resume. When describing your work history, include top critical thinking skills that accurately describe you. You can also include them in your resume summary, if you have one.

For example, your summary might read, “Marketing Associate with five years of experience in project management. Skilled in conducting thorough market research and competitor analysis to assess market trends and client needs, and to develop appropriate acquisition tactics.”

Mention Skills in Your Cover Letter

Include these critical thinking skills in your cover letter. In the body of your letter, mention one or two of these skills, and give specific examples of times when you have demonstrated them at work. Think about times when you had to analyze or evaluate materials to solve a problem.

Show the Interviewer Your Skills

You can use these skill words in an interview. Discuss a time when you were faced with a particular problem or challenge at work and explain how you applied critical thinking to solve it.

Some interviewers will give you a hypothetical scenario or problem, and ask you to use critical thinking skills to solve it. In this case, explain your thought process thoroughly to the interviewer. He or she is typically more focused on how you arrive at your solution rather than the solution itself. The interviewer wants to see you analyze and evaluate (key parts of critical thinking) the given scenario or problem.

Of course, each job will require different skills and experiences, so make sure you read the job description carefully and focus on the skills listed by the employer.

Top Critical Thinking Skills

Keep these in-demand skills in mind as you refine your critical thinking practice —whether for work or school.

Part of critical thinking is the ability to carefully examine something, whether it is a problem, a set of data, or a text. People with analytical skills can examine information, understand what it means, and properly explain to others the implications of that information.

- Asking Thoughtful Questions

- Data Analysis

- Interpretation

- Questioning Evidence

- Recognizing Patterns

Communication

Often, you will need to share your conclusions with your employers or with a group of classmates or colleagues. You need to be able to communicate with others to share your ideas effectively. You might also need to engage in critical thinking in a group. In this case, you will need to work with others and communicate effectively to figure out solutions to complex problems.

- Active Listening

- Collaboration

- Explanation

- Interpersonal

- Presentation

- Verbal Communication

- Written Communication

Critical thinking often involves creativity and innovation. You might need to spot patterns in the information you are looking at or come up with a solution that no one else has thought of before. All of this involves a creative eye that can take a different approach from all other approaches.

- Flexibility

- Conceptualization

- Imagination

- Drawing Connections

- Synthesizing

Open-Mindedness

To think critically, you need to be able to put aside any assumptions or judgments and merely analyze the information you receive. You need to be objective, evaluating ideas without bias.

- Objectivity

- Observation

Problem-Solving

Problem-solving is another critical thinking skill that involves analyzing a problem, generating and implementing a solution, and assessing the success of the plan. Employers don’t simply want employees who can think about information critically. They also need to be able to come up with practical solutions.

- Attention to Detail

- Clarification

- Decision Making

- Groundedness

- Identifying Patterns

More Critical Thinking Skills

- Inductive Reasoning

- Deductive Reasoning

- Noticing Outliers

- Adaptability

- Emotional Intelligence

- Brainstorming

- Optimization

- Restructuring

- Integration

- Strategic Planning

- Project Management

- Ongoing Improvement

- Causal Relationships

- Case Analysis

- Diagnostics

- SWOT Analysis

- Business Intelligence

- Quantitative Data Management

- Qualitative Data Management

- Risk Management

- Scientific Method

- Consumer Behavior

Key Takeaways

- Demonstrate you have critical thinking skills by adding relevant keywords to your resume.

- Mention pertinent critical thinking skills in your cover letter, too, and include an example of a time when you demonstrated them at work.

- Finally, highlight critical thinking skills during your interview. For instance, you might discuss a time when you were faced with a challenge at work and explain how you applied critical thinking skills to solve it.

University of Louisville. " What is Critical Thinking ."

American Management Association. " AMA Critical Skills Survey: Workers Need Higher Level Skills to Succeed in the 21st Century ."

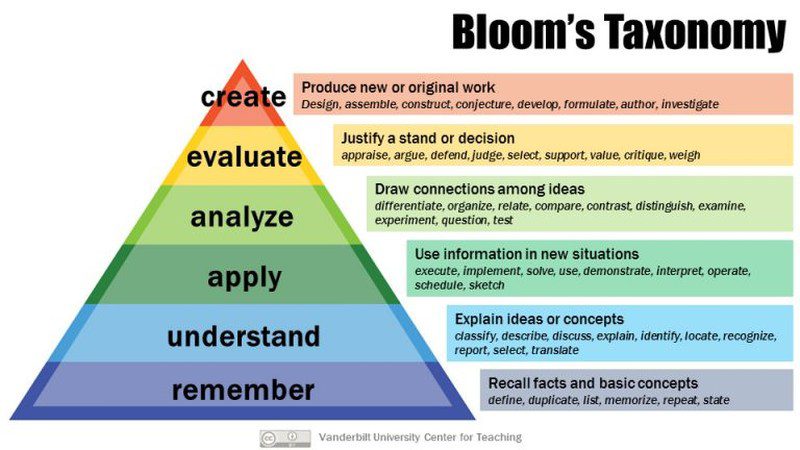

- Questions for Each Level of Bloom's Taxonomy

- Critical Thinking in Reading and Composition

- Bloom's Taxonomy in the Classroom

- How To Become an Effective Problem Solver

- 2020-21 Common Application Essay Option 4—Solving a Problem

- Introduction to Critical Thinking

- Creativity & Creative Thinking

- Higher-Order Thinking Skills (HOTS) in Education

- 6 Skills Students Need to Succeed in Social Studies Classes

- College Interview Tips: "Tell Me About a Challenge You Overcame"

- Types of Medical School Interviews and What to Expect

- The Horse Problem: A Math Challenge

- What to Do When the Technology Fails in Class

- What Are Your Strengths and Weaknesses? Interview Tips for Teachers

- A Guide to Business Letters Types

- Landing Your First Teaching Job

- Partnerships

Critical thinking

Effective lifelong learning

Executive summary

- One of the most striking characteristics of the XX and XXI centuries is the “exponential growth” of knowledge generated in any discipline, which is available to most of the world’s citizens.

- As it is no longer possible to comprehend all the information available, in relation to disciplines or even subdisciplines, education should promote the acquisition of learning abilities related to modes of thought rather than solely the accumulation or memorization of, in many cases, information that may be only infrequently useful.

- One mode of thought, reflective thinking or critical thinking, is a metacognitive process—a set of habituated intellectual resources put purposefully into action—that enables a deeper understanding of new information. It also provides a secure foundation for more effective problem-solving, decision-making, and appropriate argumentation of ideas and opinions.

- The global output of teaching critical thinking is adding new competences to everyone’s basic capacities for greater cognitive development and freedom.

“… Nothing better for the mental development of the child and the adolescent than to teach them superior ways of learning that complement, continue, rectify and elevate the spontaneous ways. Originality is a precious heritage that the pedagogue must not only guard, but lead, in the domain of values, to its maximum expression. And with superior ways of learning, culture and originality grow in parallel. To teach superior ways of learning is to add to the native powers, new powers for greater independence of the spirit in all its manifestations. It is teaching to move only upwards…Teaching to observe well, to think well, to feel good, to express oneself well and to act well is what, in sum, every pedagogical doctrine, new or old, revolutionary or conservative, of now and forever, is materialized.” (Clemente Estable, 1947 1 ).

Introduction and historical background

The brain is the organ that allows us to think. This confronts us with a philosophical challenge that has been accompanying human civilization for more than 2,500 years: H ow can the brain help us to understand how the brain enables us to understand? 2

Ancient Greek philosophers have already questioned themselves about the source of knowledge and cognitive functions and hypothesized about the fundamental role of the brain, in opposition to the heart or even the air or fire 3-6 . The Socratic method, involving the introspective scrutiny of thought guided by questioning, paved the long-lasting way to contemporary approaches and conceptions about “good thinking,” also called “reflective thinking,” 7 and more recently, “critical thinking” 8 .

As in any area of knowledge, most of the accumulated content—which is vast and always evolving—is nowadays accessible to everyone who has access to the internet. Thus, it can be argued that educational efforts should concentrate on improving the next generation’s modes of thinking. It is desirable to promote engagement with knowledge rather than transmitting the requirement of accumulating data—usually disposable information—through mastery or memorization 9 .

Critical thinking is a fundamental pillar in every field of learning within disciplines as diverse as science, technology, engineering, and mathematics as well as the humanities including literature, history, art, and philosophy 5,9,10 .

No matter the discipline, critical thinking pursues some end or purpose, such as answering a question, deciding, solving a problem, devising a plan, or carrying out a project to face present and future challenges 11 . Hence, it is also applicable to everyday life and is desirable for a plural society with citizenship literacy and scientific competence for participation in diverse situations, including dilemmas of scientific tenor 7,12 .

In spite of the explicit valuing of critical thinking, and iterative efforts to promote its effective incorporation in the curricula at different levels of education of science, humanities, and education itself, difficulties for deeper grasping of critical thinking and challenges for its fruitful integration in educational curricula persist 13,14 . Such difficulty is in part caused by a lack of consensus regarding a definition of critical thinking.

Defining critical thinking

Critical thinking is a mental process 11 like creative thinking, intuition, and emotional reasoning, all of which are important to the psychological life of an individual 10 . It pertains to a family of forms of higher order thinking, including problem-solving, creative thinking, and decision-making 15 . However, there is not a single or direct definition of critical thinking, probably reflecting the emphasis made on different features or aspects by several authors from diverse disciplines as education, philosophy, and neurosciences 7,10,16-18 .

Some of the distinguishing features of critical thinking and critical thinkers are ( 7, 11, 12, 16, 19, 20 ; see Figure 1):

Figure 1. Diagram of the principal features of critical thinking, including some of the necessary cognitive functions and intellectual resources. The arrows indicate the main mechanisms of modulation: top-down, involving the effect of upper on lower level intellectual resources (for example, the effect of metacognition on motivation that in turn affects perception), and bottom-up (such as the influence of self-analysis and habituation on self-regulation and metacognition).

- Critical thinkers pursue some end or purpose such as answering a question, making a decision, solving a problem, devising a plan, or carrying out a project to cope with present or future challenges.

- Accordingly, critical thinking is purposively put into action and driven by .

- As a result of this top-down influence, critical thinking is an attitude which does not occur spontaneously.

- Critical thinking also involves the knowledge, acquisition, and improvement of a spectrum of intellectual resources such as: – methods of logical inquiry; – information literacy to gather significant information about the problem and the context for embracing comprehensive background knowledge; – operational knowledge of processing skills for generation of concepts and beliefs: analysis, evaluation, inference, reflective judgment.

- To accomplish these intellectual resources, critical thinkers need to put into action the most basic cognitive functions such as perception, motor coordination and action, sensory-motor coordination, language perception and production, memory, and decision-making.

- Critical thinkers apply these procedures and methods in a systematic and reasonable way.

- As a result, critical thinking is not an immediate cognitive event but a process .

- The main outcome of critical thinking is a reflective, ordered, causal flow of ideas .

- Critical thinkers self-analyze and self-assess the mode of thinking.

- Consequently, critical thinking is a metacognitive process .

- Self-evaluation launches a bottom-up process for modulation and improvement of critical thinking, enabling greater adaptability to different situations.

- Thus, critical thinking also requires training and habituation .

- As a global outcome, critical thinking, as a metacognitive process, also refines self-regulation (i.e., the ability to understand and control our learning environments) 20 .

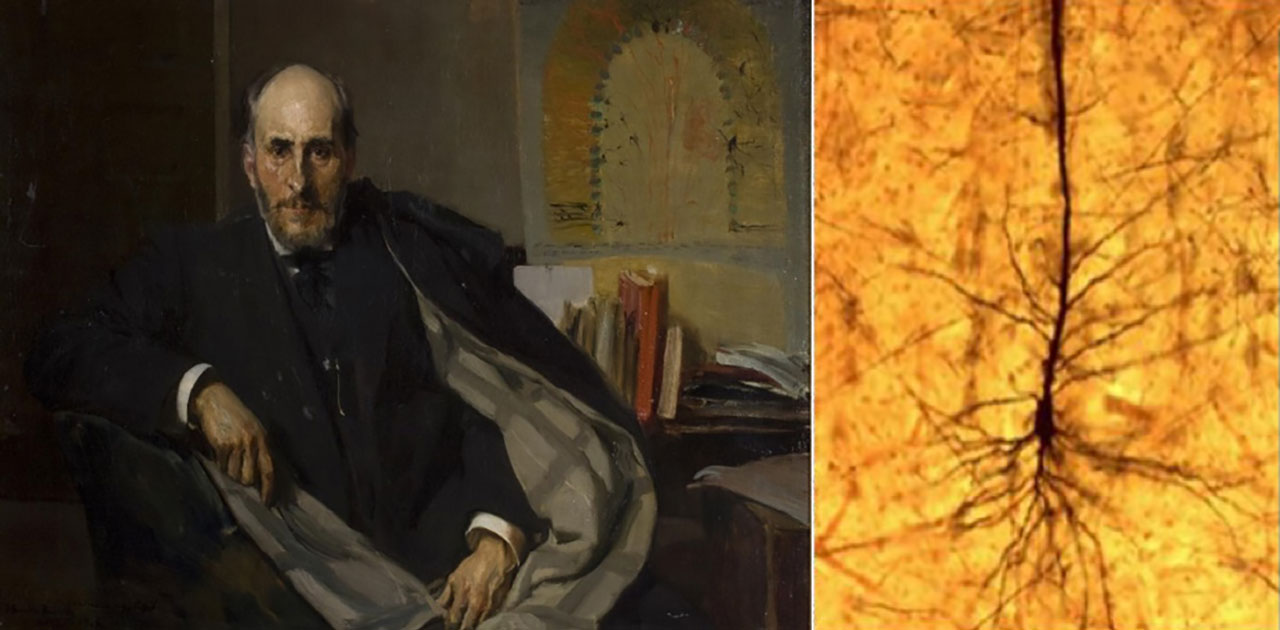

In sum, critical thinking is a purposeful, intellectually demanding, disciplined, plastic, and trainable mode of thinking in which motivation, self-analysis, and self-regulation play key roles. Several of these aspects were stressed by Santiago Ramón y Cajal (see Figure 2A). Cajal—founder of modern neuroscience and Nobel Prize of Medicine in 1906—hypothesized about the role of brain plasticity, metanalysis habituation, and self-regulation for the acquisition of knowledge about objects or problems: “When one thinks about the curious property that man possesses of changing and refining his mental activity in relation to a profoundly meditated object or problem, one cannot but suspect that the brain, thanks to its plasticity, evolves anatomically and dynamically, adapting progressively to the subject. This adequate and specific organization acquired by the nerve cells eventually produces what I would call professional talent or adaptation, and has its own will, that is, the energetic resolution to adapt our understanding to the nature of the matter.” 20

Figure 2. Left: Portrait of Santiago Ramón y Cajal. Oil painted by the Spanish Postimpressionist painter Joaquín Sorolla in 1906, the year Cajal received the Nobel Prize in Medicine 21 . Right: Microphotography of an original preparation of Cajal showing a pyramidal neuron of the human brain cortex. Staining: Golgi staining. Original handwritten label: Pyramid. Boy 22 .

Neural basis of critical thinking

Figure 3. Mapping of cognitive functions. The diagram superposed on the lateral view of the human brain indicates the location of distributed neural assemblies activated in relation to cognitive functions. Note that the indicated cognitive functions are involved in the same or successive phases of critical thinking. (Modified from ref. 26 ).

The cognitive functions and intellectual resources involved in critical thinking are emergent properties of the human brain’s structure and function which depend on the activity of its building blocks, the neurons (see Figure 2B). Neurons are specialized cells which are almost equal in number to nonneuronal cells in human brains. Of the total amount of 86 billon neurons, 19% form the cerebral cortex and 78% the cerebellum 23 . Neurons are interconnected and intercommunicate through specialized junctions called synapses, of which there are about 0,15 quadrillion in the cerebral cortex 24 and more than 3 trillion in the cerebellar cortex (considering the total number of Purkinje cells and the total amount of synapses/Purkinje cell 25 ). These stellar numbers help us imagine the density of the entangled brain web. This web is not fully active at any time. Instead, distributed groups of neurons or “distributed neural assemblies” are more active at certain topographies when particular cognitive functions are taking place 26 . Considering the spectrum of cognitive functions involved in the process of critical thinking, it will increase activation in much of the brain cortex (see Figure 3).

Teaching critical thinking

“It is not enough to know how we learn, we must know how to teach.” (Tracey Tokuhama-Espinosa, 2010 27 ).

Teachers have the invaluable potential power of fostering knowledge in the next generations of students and citizens. However, this power is expressed when teachers, instead of teaching what they know—and hence limiting students’ knowledge to their own—teach students to think critically and so open up the possibility that students’ knowledge will expand beyond the borders of the teachers’ own knowledge 28 . Thus, it is important to be aware that—similar to electrical circuits and Ohm’s law—the wealth and depth of students’ knowledge that is achieved or expressed depends not only on the energy or effort that students put in the task but also their own (internal) resistance as well as teachers’ (external) resistance. This metaphor exemplifies that the expected outcomes of education may be better achieved if teachers are familiar with the foundations of critical thinking, better appreciate its worth, and themselves become proficient at thinking critically, particularly in relation to their professional activity.

Now more than ever it is possible for teachers to build a framework to improve the teaching and learning of critical thinking in the classroom 29 thanks to a wealth of information and guidelines resulting from contributions of diverse disciplines since the renewed interest in critical thinking and its promotion in education pioneered by Dewey 7 at the dawn of the 20th century. According to Boisvert (1999 28 ), up to the 1980s, education focused on the abilities of critical thinking as goals to achieve.

Since then, a growing movement of critical thinking has been characterized by iterative attempts to define critical thinking, as well as by instructing teachers about this process and how to teach it. In parallel, several tools for assessment have been created 11, 30, 31, 32, 33 .

Nevertheless, the long-lasting aim has not been achieved. In trying to envisage more fruitful strategies, it is worth noting the difficulty of transmitting critical thinking as just a skill that can be trained without considering the context. On the contrary, the domain of knowledge and the development of critical thinking should be considered in parallel as related intellectual resources—as pointed out by Willimham 33 . It is worth pointing out that, parallel to the critical thinking movement, there has been an increasing simultaneous interest in the neural bases of critical thinking, leading to the emergence 5,34 of “educational neuroscience” 35 and “brain, mind and education” 36 . These interdisciplinary fields have been elucidating the fundamental mechanisms involved in critical thinking as well as the role of factors that impact on this ability. This, along with the tight collaboration between scientists and teachers, is forging a new (Machado) path or bridge over the “gulf” between these fields 35 .

References/Suggested Readings & Notes

- Estable, C. 1947. Pedagogía de presión normativa y pedagogía de la personalidad y de la vocación. An. Ateneo Urug., 2ª ed., 1, 155-156. http://www.periodicas.edu.uy/Anales_Ateneo_Uruguay/pdfs/Anales_Ateneo_Uruguay_2a_epoca_n2.pdf

- Shepherd, G, M. 1994. Neurobiology, 3rd edn , Oxford University Press.

- Cope, E. M. 1875. Plato’s Phaedo, Literally translated , Cambridge University Press.

- Adams, L. L. D. 1849. Hippocrates Translated from the Greek with a preliminary discourse and annotations. The Sydenham Society.

- Vieira, R. M., Tenreiro-Vieira, C. & Martins, I. P. Critical thinking: conceptual clarification and its importance in science education. Science Education International 22,43–54 (2011).

- Panegyres, K. P. & Panegyres, P. K. The ancient Greek discovery of the nervous system: Alcmaeon, Praxagoras and Herophilus. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience 29, 21–24 (2016).

- Dewey, J. How we think. The Problem of Training Thought 14 (1910). doi:10.1037/10903-000

- Glaser, E. M. (1941). An experiment in the development of critical thinking . New York: Columbia University Teachers College.

- Edmonds, Michael, et al. History & Critical Thinking: A Handbook for Using Historical Documents to Improve Students’ Thinking Skills in the Secondary Grades. Wisconsin Historical Society, 2005. http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/pdfs/lessons/EDU-History-and-Critical-Thinking-Handbook.pdf

- Mulnix, J. W. Thinking critically about critical thinking. Educational Philosophy and Theory 44, 464–479 (2012).

- Bailin, S., Case, R., Coombs, J. R. & Daniels, L. B. Conceptualizing critical thinking. Journal of Curriculum Studies 31, 285–302 (1999).

- Dwyer, C. P., Hogan, M. J. & Stewart, I. An integrated critical thinking framework for the 21st century. Thinking Skills and Creativity 12, 43–52 (2014).

- Paul, R. The state of critical thinking today. New Directions for Community Colleges 130, 27–39 (2005).

- Lloyd, M. & Bahr, N. Thinking critically about critical thinking in higher education. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching & Learning 4, 1–16 (2010).

- Rudd, R. D. Defining critical thinking. Techniques. 46 (2007).

- Siegel, H. (1988) . Educating reason: Rationality, critical thinking, and education . Philosophy of education research library. Routledge Inc.

- Siegel, H. in International Encyclopedia of Education 141–145 (Elsevier Ltd, 2010). doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-044894-7.00582-0

- Bailin, S. Critical thinking and science education. Science & Education (2002) 11: 361. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016042608621

- Facione, P. A. Critical Thinking: A Statement of Expert Consensus for Purposes of Educational Assessment and Instruction. California Academic Press 1–19 (1990). doi:10.1080/00324728.2012.723893

- Schraw, G., Crippen, K. J., & Hartley, K. (2006). Promoting self-regulation in science education: metacognition as part of a broader perspective on learning. Research in Science Education 36(1–2), 111–139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-005-3917-8

- Ramon y Cajal, S. Recuerdos de mi vida . Juan Fernández Santarén, Barcelona. Editorial Crítica ( 1899); Of Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida, Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=32562506).

- From: http://www.montelouro.es/Cajal.html.

- Herculano-Houzel, S. The human brain in numbers: a linearly scaled-up primate brain. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 3, (2009).

- Pakkenberg, B. et al. Aging and the human neocortex. Experimental Gerontology 38, 95–99 (2003).

- Nairn JG, Bedi KS, Mayhew TM, Campbell LF. On the number of Purkinje cells in the human cerebellum: unbiased estimates obtained by using the “fractionator”. J Comp Neurol. 290(4), 527-32 (1989).

- Pulvermüller, F., Garagnani, M. & Wennekers, T. Thinking in circuits: toward neurobiological explanation in cognitive neuroscience. Biological Cybernetics 108, 573–593 (2014).

- Tokuhama-Espinosa, T. The New Science of Teaching and Learning: Using the Best of Mind, Brain, and Education Science in the Classroom. Teachers College Press (2010).

- Chavan, A. A. & Khandagale V. S. Development of critical thinking skill programme for the student teachers of diploma in teacher education colleges. Issues Ideas Educ. http://dspace.chitkara.edu.in/xmlui/handle/1/159.

- Paul, R. & Elder, L. Guide for educators to critical thinking competency standards: standards, principles, performance indicators, and outcomes with a critical thinking master rubric. Foundation for Critical Thinking. (2007).

- Paul, R. W. Critical Thinking: What Every Person Needs to Survive in a Rapidly Changing World. Foundation for Critical Thinking. (2000). Retrieved from http://assets00.grou.ps/0F2E3C/wysiwyg_files/FilesModule/criticalthinkingandwriting/20090921185639-uxlhmlnvedpammxrz/CritThink1.pdf

- Paul, R. W., Elder, L. & Bartell, T. California Teacher Preparation for Instruction in Critical Thinking: Research Findings and Policy Recommendations. (1997). Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1001.1087&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Vieira, R. M. Formação continuada de professores do 1.º e 2.º ciclos do Ensino Básico para uma educação em Ciências com orientação CTS/PC. Tese de doutoramento (não publicada), Universidade de Aveiro. (2003). Retrieved from: http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/374/37419205.pdf

- Willingham, D. T. Critical Thinking: Why Is It So Hard to Teach? American Educator 31, 8-19. (2007). Retrieved from http://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/periodicals/Crit_Thinking.pdf

- Zadina, J. N. The emerging role of educational neuroscience in education reform. Psicología Educativa 21,71–77 (2015).

- Goswami, U. Neurociencia y Educación: ¿podemos ir de la investigación básica a su aplicación? Un posible marco de referencia desde la investigación en dislexia. Psicologia Educativa 21, 97–105 (2015).

- Schwartz, M. Mind, brain and education: a decade of evolution. Mind, Brain, and Education 9, 64–71 (2015).

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Critical Thinking

Critical thinking is a widely accepted educational goal. Its definition is contested, but the competing definitions can be understood as differing conceptions of the same basic concept: careful thinking directed to a goal. Conceptions differ with respect to the scope of such thinking, the type of goal, the criteria and norms for thinking carefully, and the thinking components on which they focus. Its adoption as an educational goal has been recommended on the basis of respect for students’ autonomy and preparing students for success in life and for democratic citizenship. “Critical thinkers” have the dispositions and abilities that lead them to think critically when appropriate. The abilities can be identified directly; the dispositions indirectly, by considering what factors contribute to or impede exercise of the abilities. Standardized tests have been developed to assess the degree to which a person possesses such dispositions and abilities. Educational intervention has been shown experimentally to improve them, particularly when it includes dialogue, anchored instruction, and mentoring. Controversies have arisen over the generalizability of critical thinking across domains, over alleged bias in critical thinking theories and instruction, and over the relationship of critical thinking to other types of thinking.

2.1 Dewey’s Three Main Examples

2.2 dewey’s other examples, 2.3 further examples, 2.4 non-examples, 3. the definition of critical thinking, 4. its value, 5. the process of thinking critically, 6. components of the process, 7. contributory dispositions and abilities, 8.1 initiating dispositions, 8.2 internal dispositions, 9. critical thinking abilities, 10. required knowledge, 11. educational methods, 12.1 the generalizability of critical thinking, 12.2 bias in critical thinking theory and pedagogy, 12.3 relationship of critical thinking to other types of thinking, other internet resources, related entries.

Use of the term ‘critical thinking’ to describe an educational goal goes back to the American philosopher John Dewey (1910), who more commonly called it ‘reflective thinking’. He defined it as

active, persistent and careful consideration of any belief or supposed form of knowledge in the light of the grounds that support it, and the further conclusions to which it tends. (Dewey 1910: 6; 1933: 9)

and identified a habit of such consideration with a scientific attitude of mind. His lengthy quotations of Francis Bacon, John Locke, and John Stuart Mill indicate that he was not the first person to propose development of a scientific attitude of mind as an educational goal.

In the 1930s, many of the schools that participated in the Eight-Year Study of the Progressive Education Association (Aikin 1942) adopted critical thinking as an educational goal, for whose achievement the study’s Evaluation Staff developed tests (Smith, Tyler, & Evaluation Staff 1942). Glaser (1941) showed experimentally that it was possible to improve the critical thinking of high school students. Bloom’s influential taxonomy of cognitive educational objectives (Bloom et al. 1956) incorporated critical thinking abilities. Ennis (1962) proposed 12 aspects of critical thinking as a basis for research on the teaching and evaluation of critical thinking ability.

Since 1980, an annual international conference in California on critical thinking and educational reform has attracted tens of thousands of educators from all levels of education and from many parts of the world. Also since 1980, the state university system in California has required all undergraduate students to take a critical thinking course. Since 1983, the Association for Informal Logic and Critical Thinking has sponsored sessions in conjunction with the divisional meetings of the American Philosophical Association (APA). In 1987, the APA’s Committee on Pre-College Philosophy commissioned a consensus statement on critical thinking for purposes of educational assessment and instruction (Facione 1990a). Researchers have developed standardized tests of critical thinking abilities and dispositions; for details, see the Supplement on Assessment . Educational jurisdictions around the world now include critical thinking in guidelines for curriculum and assessment.

For details on this history, see the Supplement on History .

2. Examples and Non-Examples

Before considering the definition of critical thinking, it will be helpful to have in mind some examples of critical thinking, as well as some examples of kinds of thinking that would apparently not count as critical thinking.

Dewey (1910: 68–71; 1933: 91–94) takes as paradigms of reflective thinking three class papers of students in which they describe their thinking. The examples range from the everyday to the scientific.

Transit : “The other day, when I was down town on 16th Street, a clock caught my eye. I saw that the hands pointed to 12:20. This suggested that I had an engagement at 124th Street, at one o’clock. I reasoned that as it had taken me an hour to come down on a surface car, I should probably be twenty minutes late if I returned the same way. I might save twenty minutes by a subway express. But was there a station near? If not, I might lose more than twenty minutes in looking for one. Then I thought of the elevated, and I saw there was such a line within two blocks. But where was the station? If it were several blocks above or below the street I was on, I should lose time instead of gaining it. My mind went back to the subway express as quicker than the elevated; furthermore, I remembered that it went nearer than the elevated to the part of 124th Street I wished to reach, so that time would be saved at the end of the journey. I concluded in favor of the subway, and reached my destination by one o’clock.” (Dewey 1910: 68–69; 1933: 91–92)

Ferryboat : “Projecting nearly horizontally from the upper deck of the ferryboat on which I daily cross the river is a long white pole, having a gilded ball at its tip. It suggested a flagpole when I first saw it; its color, shape, and gilded ball agreed with this idea, and these reasons seemed to justify me in this belief. But soon difficulties presented themselves. The pole was nearly horizontal, an unusual position for a flagpole; in the next place, there was no pulley, ring, or cord by which to attach a flag; finally, there were elsewhere on the boat two vertical staffs from which flags were occasionally flown. It seemed probable that the pole was not there for flag-flying.

“I then tried to imagine all possible purposes of the pole, and to consider for which of these it was best suited: (a) Possibly it was an ornament. But as all the ferryboats and even the tugboats carried poles, this hypothesis was rejected. (b) Possibly it was the terminal of a wireless telegraph. But the same considerations made this improbable. Besides, the more natural place for such a terminal would be the highest part of the boat, on top of the pilot house. (c) Its purpose might be to point out the direction in which the boat is moving.

“In support of this conclusion, I discovered that the pole was lower than the pilot house, so that the steersman could easily see it. Moreover, the tip was enough higher than the base, so that, from the pilot’s position, it must appear to project far out in front of the boat. Moreover, the pilot being near the front of the boat, he would need some such guide as to its direction. Tugboats would also need poles for such a purpose. This hypothesis was so much more probable than the others that I accepted it. I formed the conclusion that the pole was set up for the purpose of showing the pilot the direction in which the boat pointed, to enable him to steer correctly.” (Dewey 1910: 69–70; 1933: 92–93)

Bubbles : “In washing tumblers in hot soapsuds and placing them mouth downward on a plate, bubbles appeared on the outside of the mouth of the tumblers and then went inside. Why? The presence of bubbles suggests air, which I note must come from inside the tumbler. I see that the soapy water on the plate prevents escape of the air save as it may be caught in bubbles. But why should air leave the tumbler? There was no substance entering to force it out. It must have expanded. It expands by increase of heat, or by decrease of pressure, or both. Could the air have become heated after the tumbler was taken from the hot suds? Clearly not the air that was already entangled in the water. If heated air was the cause, cold air must have entered in transferring the tumblers from the suds to the plate. I test to see if this supposition is true by taking several more tumblers out. Some I shake so as to make sure of entrapping cold air in them. Some I take out holding mouth downward in order to prevent cold air from entering. Bubbles appear on the outside of every one of the former and on none of the latter. I must be right in my inference. Air from the outside must have been expanded by the heat of the tumbler, which explains the appearance of the bubbles on the outside. But why do they then go inside? Cold contracts. The tumbler cooled and also the air inside it. Tension was removed, and hence bubbles appeared inside. To be sure of this, I test by placing a cup of ice on the tumbler while the bubbles are still forming outside. They soon reverse” (Dewey 1910: 70–71; 1933: 93–94).

Dewey (1910, 1933) sprinkles his book with other examples of critical thinking. We will refer to the following.

Weather : A man on a walk notices that it has suddenly become cool, thinks that it is probably going to rain, looks up and sees a dark cloud obscuring the sun, and quickens his steps (1910: 6–10; 1933: 9–13).

Disorder : A man finds his rooms on his return to them in disorder with his belongings thrown about, thinks at first of burglary as an explanation, then thinks of mischievous children as being an alternative explanation, then looks to see whether valuables are missing, and discovers that they are (1910: 82–83; 1933: 166–168).

Typhoid : A physician diagnosing a patient whose conspicuous symptoms suggest typhoid avoids drawing a conclusion until more data are gathered by questioning the patient and by making tests (1910: 85–86; 1933: 170).

Blur : A moving blur catches our eye in the distance, we ask ourselves whether it is a cloud of whirling dust or a tree moving its branches or a man signaling to us, we think of other traits that should be found on each of those possibilities, and we look and see if those traits are found (1910: 102, 108; 1933: 121, 133).

Suction pump : In thinking about the suction pump, the scientist first notes that it will draw water only to a maximum height of 33 feet at sea level and to a lesser maximum height at higher elevations, selects for attention the differing atmospheric pressure at these elevations, sets up experiments in which the air is removed from a vessel containing water (when suction no longer works) and in which the weight of air at various levels is calculated, compares the results of reasoning about the height to which a given weight of air will allow a suction pump to raise water with the observed maximum height at different elevations, and finally assimilates the suction pump to such apparently different phenomena as the siphon and the rising of a balloon (1910: 150–153; 1933: 195–198).

Diamond : A passenger in a car driving in a diamond lane reserved for vehicles with at least one passenger notices that the diamond marks on the pavement are far apart in some places and close together in others. Why? The driver suggests that the reason may be that the diamond marks are not needed where there is a solid double line separating the diamond lane from the adjoining lane, but are needed when there is a dotted single line permitting crossing into the diamond lane. Further observation confirms that the diamonds are close together when a dotted line separates the diamond lane from its neighbour, but otherwise far apart.

Rash : A woman suddenly develops a very itchy red rash on her throat and upper chest. She recently noticed a mark on the back of her right hand, but was not sure whether the mark was a rash or a scrape. She lies down in bed and thinks about what might be causing the rash and what to do about it. About two weeks before, she began taking blood pressure medication that contained a sulfa drug, and the pharmacist had warned her, in view of a previous allergic reaction to a medication containing a sulfa drug, to be on the alert for an allergic reaction; however, she had been taking the medication for two weeks with no such effect. The day before, she began using a new cream on her neck and upper chest; against the new cream as the cause was mark on the back of her hand, which had not been exposed to the cream. She began taking probiotics about a month before. She also recently started new eye drops, but she supposed that manufacturers of eye drops would be careful not to include allergy-causing components in the medication. The rash might be a heat rash, since she recently was sweating profusely from her upper body. Since she is about to go away on a short vacation, where she would not have access to her usual physician, she decides to keep taking the probiotics and using the new eye drops but to discontinue the blood pressure medication and to switch back to the old cream for her neck and upper chest. She forms a plan to consult her regular physician on her return about the blood pressure medication.

Candidate : Although Dewey included no examples of thinking directed at appraising the arguments of others, such thinking has come to be considered a kind of critical thinking. We find an example of such thinking in the performance task on the Collegiate Learning Assessment (CLA+), which its sponsoring organization describes as

a performance-based assessment that provides a measure of an institution’s contribution to the development of critical-thinking and written communication skills of its students. (Council for Aid to Education 2017)

A sample task posted on its website requires the test-taker to write a report for public distribution evaluating a fictional candidate’s policy proposals and their supporting arguments, using supplied background documents, with a recommendation on whether to endorse the candidate.

Immediate acceptance of an idea that suggests itself as a solution to a problem (e.g., a possible explanation of an event or phenomenon, an action that seems likely to produce a desired result) is “uncritical thinking, the minimum of reflection” (Dewey 1910: 13). On-going suspension of judgment in the light of doubt about a possible solution is not critical thinking (Dewey 1910: 108). Critique driven by a dogmatically held political or religious ideology is not critical thinking; thus Paulo Freire (1968 [1970]) is using the term (e.g., at 1970: 71, 81, 100, 146) in a more politically freighted sense that includes not only reflection but also revolutionary action against oppression. Derivation of a conclusion from given data using an algorithm is not critical thinking.

What is critical thinking? There are many definitions. Ennis (2016) lists 14 philosophically oriented scholarly definitions and three dictionary definitions. Following Rawls (1971), who distinguished his conception of justice from a utilitarian conception but regarded them as rival conceptions of the same concept, Ennis maintains that the 17 definitions are different conceptions of the same concept. Rawls articulated the shared concept of justice as

a characteristic set of principles for assigning basic rights and duties and for determining… the proper distribution of the benefits and burdens of social cooperation. (Rawls 1971: 5)

Bailin et al. (1999b) claim that, if one considers what sorts of thinking an educator would take not to be critical thinking and what sorts to be critical thinking, one can conclude that educators typically understand critical thinking to have at least three features.

- It is done for the purpose of making up one’s mind about what to believe or do.

- The person engaging in the thinking is trying to fulfill standards of adequacy and accuracy appropriate to the thinking.

- The thinking fulfills the relevant standards to some threshold level.

One could sum up the core concept that involves these three features by saying that critical thinking is careful goal-directed thinking. This core concept seems to apply to all the examples of critical thinking described in the previous section. As for the non-examples, their exclusion depends on construing careful thinking as excluding jumping immediately to conclusions, suspending judgment no matter how strong the evidence, reasoning from an unquestioned ideological or religious perspective, and routinely using an algorithm to answer a question.

If the core of critical thinking is careful goal-directed thinking, conceptions of it can vary according to its presumed scope, its presumed goal, one’s criteria and threshold for being careful, and the thinking component on which one focuses. As to its scope, some conceptions (e.g., Dewey 1910, 1933) restrict it to constructive thinking on the basis of one’s own observations and experiments, others (e.g., Ennis 1962; Fisher & Scriven 1997; Johnson 1992) to appraisal of the products of such thinking. Ennis (1991) and Bailin et al. (1999b) take it to cover both construction and appraisal. As to its goal, some conceptions restrict it to forming a judgment (Dewey 1910, 1933; Lipman 1987; Facione 1990a). Others allow for actions as well as beliefs as the end point of a process of critical thinking (Ennis 1991; Bailin et al. 1999b). As to the criteria and threshold for being careful, definitions vary in the term used to indicate that critical thinking satisfies certain norms: “intellectually disciplined” (Scriven & Paul 1987), “reasonable” (Ennis 1991), “skillful” (Lipman 1987), “skilled” (Fisher & Scriven 1997), “careful” (Bailin & Battersby 2009). Some definitions specify these norms, referring variously to “consideration of any belief or supposed form of knowledge in the light of the grounds that support it and the further conclusions to which it tends” (Dewey 1910, 1933); “the methods of logical inquiry and reasoning” (Glaser 1941); “conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and/or evaluating information gathered from, or generated by, observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication” (Scriven & Paul 1987); the requirement that “it is sensitive to context, relies on criteria, and is self-correcting” (Lipman 1987); “evidential, conceptual, methodological, criteriological, or contextual considerations” (Facione 1990a); and “plus-minus considerations of the product in terms of appropriate standards (or criteria)” (Johnson 1992). Stanovich and Stanovich (2010) propose to ground the concept of critical thinking in the concept of rationality, which they understand as combining epistemic rationality (fitting one’s beliefs to the world) and instrumental rationality (optimizing goal fulfillment); a critical thinker, in their view, is someone with “a propensity to override suboptimal responses from the autonomous mind” (2010: 227). These variant specifications of norms for critical thinking are not necessarily incompatible with one another, and in any case presuppose the core notion of thinking carefully. As to the thinking component singled out, some definitions focus on suspension of judgment during the thinking (Dewey 1910; McPeck 1981), others on inquiry while judgment is suspended (Bailin & Battersby 2009, 2021), others on the resulting judgment (Facione 1990a), and still others on responsiveness to reasons (Siegel 1988). Kuhn (2019) takes critical thinking to be more a dialogic practice of advancing and responding to arguments than an individual ability.

In educational contexts, a definition of critical thinking is a “programmatic definition” (Scheffler 1960: 19). It expresses a practical program for achieving an educational goal. For this purpose, a one-sentence formulaic definition is much less useful than articulation of a critical thinking process, with criteria and standards for the kinds of thinking that the process may involve. The real educational goal is recognition, adoption and implementation by students of those criteria and standards. That adoption and implementation in turn consists in acquiring the knowledge, abilities and dispositions of a critical thinker.

Conceptions of critical thinking generally do not include moral integrity as part of the concept. Dewey, for example, took critical thinking to be the ultimate intellectual goal of education, but distinguished it from the development of social cooperation among school children, which he took to be the central moral goal. Ennis (1996, 2011) added to his previous list of critical thinking dispositions a group of dispositions to care about the dignity and worth of every person, which he described as a “correlative” (1996) disposition without which critical thinking would be less valuable and perhaps harmful. An educational program that aimed at developing critical thinking but not the correlative disposition to care about the dignity and worth of every person, he asserted, “would be deficient and perhaps dangerous” (Ennis 1996: 172).

Dewey thought that education for reflective thinking would be of value to both the individual and society; recognition in educational practice of the kinship to the scientific attitude of children’s native curiosity, fertile imagination and love of experimental inquiry “would make for individual happiness and the reduction of social waste” (Dewey 1910: iii). Schools participating in the Eight-Year Study took development of the habit of reflective thinking and skill in solving problems as a means to leading young people to understand, appreciate and live the democratic way of life characteristic of the United States (Aikin 1942: 17–18, 81). Harvey Siegel (1988: 55–61) has offered four considerations in support of adopting critical thinking as an educational ideal. (1) Respect for persons requires that schools and teachers honour students’ demands for reasons and explanations, deal with students honestly, and recognize the need to confront students’ independent judgment; these requirements concern the manner in which teachers treat students. (2) Education has the task of preparing children to be successful adults, a task that requires development of their self-sufficiency. (3) Education should initiate children into the rational traditions in such fields as history, science and mathematics. (4) Education should prepare children to become democratic citizens, which requires reasoned procedures and critical talents and attitudes. To supplement these considerations, Siegel (1988: 62–90) responds to two objections: the ideology objection that adoption of any educational ideal requires a prior ideological commitment and the indoctrination objection that cultivation of critical thinking cannot escape being a form of indoctrination.

Despite the diversity of our 11 examples, one can recognize a common pattern. Dewey analyzed it as consisting of five phases:

- suggestions , in which the mind leaps forward to a possible solution;

- an intellectualization of the difficulty or perplexity into a problem to be solved, a question for which the answer must be sought;

- the use of one suggestion after another as a leading idea, or hypothesis , to initiate and guide observation and other operations in collection of factual material;

- the mental elaboration of the idea or supposition as an idea or supposition ( reasoning , in the sense on which reasoning is a part, not the whole, of inference); and

- testing the hypothesis by overt or imaginative action. (Dewey 1933: 106–107; italics in original)

The process of reflective thinking consisting of these phases would be preceded by a perplexed, troubled or confused situation and followed by a cleared-up, unified, resolved situation (Dewey 1933: 106). The term ‘phases’ replaced the term ‘steps’ (Dewey 1910: 72), thus removing the earlier suggestion of an invariant sequence. Variants of the above analysis appeared in (Dewey 1916: 177) and (Dewey 1938: 101–119).

The variant formulations indicate the difficulty of giving a single logical analysis of such a varied process. The process of critical thinking may have a spiral pattern, with the problem being redefined in the light of obstacles to solving it as originally formulated. For example, the person in Transit might have concluded that getting to the appointment at the scheduled time was impossible and have reformulated the problem as that of rescheduling the appointment for a mutually convenient time. Further, defining a problem does not always follow after or lead immediately to an idea of a suggested solution. Nor should it do so, as Dewey himself recognized in describing the physician in Typhoid as avoiding any strong preference for this or that conclusion before getting further information (Dewey 1910: 85; 1933: 170). People with a hypothesis in mind, even one to which they have a very weak commitment, have a so-called “confirmation bias” (Nickerson 1998): they are likely to pay attention to evidence that confirms the hypothesis and to ignore evidence that counts against it or for some competing hypothesis. Detectives, intelligence agencies, and investigators of airplane accidents are well advised to gather relevant evidence systematically and to postpone even tentative adoption of an explanatory hypothesis until the collected evidence rules out with the appropriate degree of certainty all but one explanation. Dewey’s analysis of the critical thinking process can be faulted as well for requiring acceptance or rejection of a possible solution to a defined problem, with no allowance for deciding in the light of the available evidence to suspend judgment. Further, given the great variety of kinds of problems for which reflection is appropriate, there is likely to be variation in its component events. Perhaps the best way to conceptualize the critical thinking process is as a checklist whose component events can occur in a variety of orders, selectively, and more than once. These component events might include (1) noticing a difficulty, (2) defining the problem, (3) dividing the problem into manageable sub-problems, (4) formulating a variety of possible solutions to the problem or sub-problem, (5) determining what evidence is relevant to deciding among possible solutions to the problem or sub-problem, (6) devising a plan of systematic observation or experiment that will uncover the relevant evidence, (7) carrying out the plan of systematic observation or experimentation, (8) noting the results of the systematic observation or experiment, (9) gathering relevant testimony and information from others, (10) judging the credibility of testimony and information gathered from others, (11) drawing conclusions from gathered evidence and accepted testimony, and (12) accepting a solution that the evidence adequately supports (cf. Hitchcock 2017: 485).

Checklist conceptions of the process of critical thinking are open to the objection that they are too mechanical and procedural to fit the multi-dimensional and emotionally charged issues for which critical thinking is urgently needed (Paul 1984). For such issues, a more dialectical process is advocated, in which competing relevant world views are identified, their implications explored, and some sort of creative synthesis attempted.

If one considers the critical thinking process illustrated by the 11 examples, one can identify distinct kinds of mental acts and mental states that form part of it. To distinguish, label and briefly characterize these components is a useful preliminary to identifying abilities, skills, dispositions, attitudes, habits and the like that contribute causally to thinking critically. Identifying such abilities and habits is in turn a useful preliminary to setting educational goals. Setting the goals is in its turn a useful preliminary to designing strategies for helping learners to achieve the goals and to designing ways of measuring the extent to which learners have done so. Such measures provide both feedback to learners on their achievement and a basis for experimental research on the effectiveness of various strategies for educating people to think critically. Let us begin, then, by distinguishing the kinds of mental acts and mental events that can occur in a critical thinking process.

- Observing : One notices something in one’s immediate environment (sudden cooling of temperature in Weather , bubbles forming outside a glass and then going inside in Bubbles , a moving blur in the distance in Blur , a rash in Rash ). Or one notes the results of an experiment or systematic observation (valuables missing in Disorder , no suction without air pressure in Suction pump )

- Feeling : One feels puzzled or uncertain about something (how to get to an appointment on time in Transit , why the diamonds vary in spacing in Diamond ). One wants to resolve this perplexity. One feels satisfaction once one has worked out an answer (to take the subway express in Transit , diamonds closer when needed as a warning in Diamond ).

- Wondering : One formulates a question to be addressed (why bubbles form outside a tumbler taken from hot water in Bubbles , how suction pumps work in Suction pump , what caused the rash in Rash ).

- Imagining : One thinks of possible answers (bus or subway or elevated in Transit , flagpole or ornament or wireless communication aid or direction indicator in Ferryboat , allergic reaction or heat rash in Rash ).

- Inferring : One works out what would be the case if a possible answer were assumed (valuables missing if there has been a burglary in Disorder , earlier start to the rash if it is an allergic reaction to a sulfa drug in Rash ). Or one draws a conclusion once sufficient relevant evidence is gathered (take the subway in Transit , burglary in Disorder , discontinue blood pressure medication and new cream in Rash ).

- Knowledge : One uses stored knowledge of the subject-matter to generate possible answers or to infer what would be expected on the assumption of a particular answer (knowledge of a city’s public transit system in Transit , of the requirements for a flagpole in Ferryboat , of Boyle’s law in Bubbles , of allergic reactions in Rash ).

- Experimenting : One designs and carries out an experiment or a systematic observation to find out whether the results deduced from a possible answer will occur (looking at the location of the flagpole in relation to the pilot’s position in Ferryboat , putting an ice cube on top of a tumbler taken from hot water in Bubbles , measuring the height to which a suction pump will draw water at different elevations in Suction pump , noticing the spacing of diamonds when movement to or from a diamond lane is allowed in Diamond ).

- Consulting : One finds a source of information, gets the information from the source, and makes a judgment on whether to accept it. None of our 11 examples include searching for sources of information. In this respect they are unrepresentative, since most people nowadays have almost instant access to information relevant to answering any question, including many of those illustrated by the examples. However, Candidate includes the activities of extracting information from sources and evaluating its credibility.

- Identifying and analyzing arguments : One notices an argument and works out its structure and content as a preliminary to evaluating its strength. This activity is central to Candidate . It is an important part of a critical thinking process in which one surveys arguments for various positions on an issue.

- Judging : One makes a judgment on the basis of accumulated evidence and reasoning, such as the judgment in Ferryboat that the purpose of the pole is to provide direction to the pilot.

- Deciding : One makes a decision on what to do or on what policy to adopt, as in the decision in Transit to take the subway.

By definition, a person who does something voluntarily is both willing and able to do that thing at that time. Both the willingness and the ability contribute causally to the person’s action, in the sense that the voluntary action would not occur if either (or both) of these were lacking. For example, suppose that one is standing with one’s arms at one’s sides and one voluntarily lifts one’s right arm to an extended horizontal position. One would not do so if one were unable to lift one’s arm, if for example one’s right side was paralyzed as the result of a stroke. Nor would one do so if one were unwilling to lift one’s arm, if for example one were participating in a street demonstration at which a white supremacist was urging the crowd to lift their right arm in a Nazi salute and one were unwilling to express support in this way for the racist Nazi ideology. The same analysis applies to a voluntary mental process of thinking critically. It requires both willingness and ability to think critically, including willingness and ability to perform each of the mental acts that compose the process and to coordinate those acts in a sequence that is directed at resolving the initiating perplexity.

Consider willingness first. We can identify causal contributors to willingness to think critically by considering factors that would cause a person who was able to think critically about an issue nevertheless not to do so (Hamby 2014). For each factor, the opposite condition thus contributes causally to willingness to think critically on a particular occasion. For example, people who habitually jump to conclusions without considering alternatives will not think critically about issues that arise, even if they have the required abilities. The contrary condition of willingness to suspend judgment is thus a causal contributor to thinking critically.

Now consider ability. In contrast to the ability to move one’s arm, which can be completely absent because a stroke has left the arm paralyzed, the ability to think critically is a developed ability, whose absence is not a complete absence of ability to think but absence of ability to think well. We can identify the ability to think well directly, in terms of the norms and standards for good thinking. In general, to be able do well the thinking activities that can be components of a critical thinking process, one needs to know the concepts and principles that characterize their good performance, to recognize in particular cases that the concepts and principles apply, and to apply them. The knowledge, recognition and application may be procedural rather than declarative. It may be domain-specific rather than widely applicable, and in either case may need subject-matter knowledge, sometimes of a deep kind.

Reflections of the sort illustrated by the previous two paragraphs have led scholars to identify the knowledge, abilities and dispositions of a “critical thinker”, i.e., someone who thinks critically whenever it is appropriate to do so. We turn now to these three types of causal contributors to thinking critically. We start with dispositions, since arguably these are the most powerful contributors to being a critical thinker, can be fostered at an early stage of a child’s development, and are susceptible to general improvement (Glaser 1941: 175)

8. Critical Thinking Dispositions

Educational researchers use the term ‘dispositions’ broadly for the habits of mind and attitudes that contribute causally to being a critical thinker. Some writers (e.g., Paul & Elder 2006; Hamby 2014; Bailin & Battersby 2016a) propose to use the term ‘virtues’ for this dimension of a critical thinker. The virtues in question, although they are virtues of character, concern the person’s ways of thinking rather than the person’s ways of behaving towards others. They are not moral virtues but intellectual virtues, of the sort articulated by Zagzebski (1996) and discussed by Turri, Alfano, and Greco (2017).

On a realistic conception, thinking dispositions or intellectual virtues are real properties of thinkers. They are general tendencies, propensities, or inclinations to think in particular ways in particular circumstances, and can be genuinely explanatory (Siegel 1999). Sceptics argue that there is no evidence for a specific mental basis for the habits of mind that contribute to thinking critically, and that it is pedagogically misleading to posit such a basis (Bailin et al. 1999a). Whatever their status, critical thinking dispositions need motivation for their initial formation in a child—motivation that may be external or internal. As children develop, the force of habit will gradually become important in sustaining the disposition (Nieto & Valenzuela 2012). Mere force of habit, however, is unlikely to sustain critical thinking dispositions. Critical thinkers must value and enjoy using their knowledge and abilities to think things through for themselves. They must be committed to, and lovers of, inquiry.

A person may have a critical thinking disposition with respect to only some kinds of issues. For example, one could be open-minded about scientific issues but not about religious issues. Similarly, one could be confident in one’s ability to reason about the theological implications of the existence of evil in the world but not in one’s ability to reason about the best design for a guided ballistic missile.

Facione (1990a: 25) divides “affective dispositions” of critical thinking into approaches to life and living in general and approaches to specific issues, questions or problems. Adapting this distinction, one can usefully divide critical thinking dispositions into initiating dispositions (those that contribute causally to starting to think critically about an issue) and internal dispositions (those that contribute causally to doing a good job of thinking critically once one has started). The two categories are not mutually exclusive. For example, open-mindedness, in the sense of willingness to consider alternative points of view to one’s own, is both an initiating and an internal disposition.

Using the strategy of considering factors that would block people with the ability to think critically from doing so, we can identify as initiating dispositions for thinking critically attentiveness, a habit of inquiry, self-confidence, courage, open-mindedness, willingness to suspend judgment, trust in reason, wanting evidence for one’s beliefs, and seeking the truth. We consider briefly what each of these dispositions amounts to, in each case citing sources that acknowledge them.

- Attentiveness : One will not think critically if one fails to recognize an issue that needs to be thought through. For example, the pedestrian in Weather would not have looked up if he had not noticed that the air was suddenly cooler. To be a critical thinker, then, one needs to be habitually attentive to one’s surroundings, noticing not only what one senses but also sources of perplexity in messages received and in one’s own beliefs and attitudes (Facione 1990a: 25; Facione, Facione, & Giancarlo 2001).

- Habit of inquiry : Inquiry is effortful, and one needs an internal push to engage in it. For example, the student in Bubbles could easily have stopped at idle wondering about the cause of the bubbles rather than reasoning to a hypothesis, then designing and executing an experiment to test it. Thus willingness to think critically needs mental energy and initiative. What can supply that energy? Love of inquiry, or perhaps just a habit of inquiry. Hamby (2015) has argued that willingness to inquire is the central critical thinking virtue, one that encompasses all the others. It is recognized as a critical thinking disposition by Dewey (1910: 29; 1933: 35), Glaser (1941: 5), Ennis (1987: 12; 1991: 8), Facione (1990a: 25), Bailin et al. (1999b: 294), Halpern (1998: 452), and Facione, Facione, & Giancarlo (2001).

- Self-confidence : Lack of confidence in one’s abilities can block critical thinking. For example, if the woman in Rash lacked confidence in her ability to figure things out for herself, she might just have assumed that the rash on her chest was the allergic reaction to her medication against which the pharmacist had warned her. Thus willingness to think critically requires confidence in one’s ability to inquire (Facione 1990a: 25; Facione, Facione, & Giancarlo 2001).

- Courage : Fear of thinking for oneself can stop one from doing it. Thus willingness to think critically requires intellectual courage (Paul & Elder 2006: 16).

- Open-mindedness : A dogmatic attitude will impede thinking critically. For example, a person who adheres rigidly to a “pro-choice” position on the issue of the legal status of induced abortion is likely to be unwilling to consider seriously the issue of when in its development an unborn child acquires a moral right to life. Thus willingness to think critically requires open-mindedness, in the sense of a willingness to examine questions to which one already accepts an answer but which further evidence or reasoning might cause one to answer differently (Dewey 1933; Facione 1990a; Ennis 1991; Bailin et al. 1999b; Halpern 1998, Facione, Facione, & Giancarlo 2001). Paul (1981) emphasizes open-mindedness about alternative world-views, and recommends a dialectical approach to integrating such views as central to what he calls “strong sense” critical thinking. In three studies, Haran, Ritov, & Mellers (2013) found that actively open-minded thinking, including “the tendency to weigh new evidence against a favored belief, to spend sufficient time on a problem before giving up, and to consider carefully the opinions of others in forming one’s own”, led study participants to acquire information and thus to make accurate estimations.

- Willingness to suspend judgment : Premature closure on an initial solution will block critical thinking. Thus willingness to think critically requires a willingness to suspend judgment while alternatives are explored (Facione 1990a; Ennis 1991; Halpern 1998).

- Trust in reason : Since distrust in the processes of reasoned inquiry will dissuade one from engaging in it, trust in them is an initiating critical thinking disposition (Facione 1990a, 25; Bailin et al. 1999b: 294; Facione, Facione, & Giancarlo 2001; Paul & Elder 2006). In reaction to an allegedly exclusive emphasis on reason in critical thinking theory and pedagogy, Thayer-Bacon (2000) argues that intuition, imagination, and emotion have important roles to play in an adequate conception of critical thinking that she calls “constructive thinking”. From her point of view, critical thinking requires trust not only in reason but also in intuition, imagination, and emotion.

- Seeking the truth : If one does not care about the truth but is content to stick with one’s initial bias on an issue, then one will not think critically about it. Seeking the truth is thus an initiating critical thinking disposition (Bailin et al. 1999b: 294; Facione, Facione, & Giancarlo 2001). A disposition to seek the truth is implicit in more specific critical thinking dispositions, such as trying to be well-informed, considering seriously points of view other than one’s own, looking for alternatives, suspending judgment when the evidence is insufficient, and adopting a position when the evidence supporting it is sufficient.

Some of the initiating dispositions, such as open-mindedness and willingness to suspend judgment, are also internal critical thinking dispositions, in the sense of mental habits or attitudes that contribute causally to doing a good job of critical thinking once one starts the process. But there are many other internal critical thinking dispositions. Some of them are parasitic on one’s conception of good thinking. For example, it is constitutive of good thinking about an issue to formulate the issue clearly and to maintain focus on it. For this purpose, one needs not only the corresponding ability but also the corresponding disposition. Ennis (1991: 8) describes it as the disposition “to determine and maintain focus on the conclusion or question”, Facione (1990a: 25) as “clarity in stating the question or concern”. Other internal dispositions are motivators to continue or adjust the critical thinking process, such as willingness to persist in a complex task and willingness to abandon nonproductive strategies in an attempt to self-correct (Halpern 1998: 452). For a list of identified internal critical thinking dispositions, see the Supplement on Internal Critical Thinking Dispositions .

Some theorists postulate skills, i.e., acquired abilities, as operative in critical thinking. It is not obvious, however, that a good mental act is the exercise of a generic acquired skill. Inferring an expected time of arrival, as in Transit , has some generic components but also uses non-generic subject-matter knowledge. Bailin et al. (1999a) argue against viewing critical thinking skills as generic and discrete, on the ground that skilled performance at a critical thinking task cannot be separated from knowledge of concepts and from domain-specific principles of good thinking. Talk of skills, they concede, is unproblematic if it means merely that a person with critical thinking skills is capable of intelligent performance.

Despite such scepticism, theorists of critical thinking have listed as general contributors to critical thinking what they variously call abilities (Glaser 1941; Ennis 1962, 1991), skills (Facione 1990a; Halpern 1998) or competencies (Fisher & Scriven 1997). Amalgamating these lists would produce a confusing and chaotic cornucopia of more than 50 possible educational objectives, with only partial overlap among them. It makes sense instead to try to understand the reasons for the multiplicity and diversity, and to make a selection according to one’s own reasons for singling out abilities to be developed in a critical thinking curriculum. Two reasons for diversity among lists of critical thinking abilities are the underlying conception of critical thinking and the envisaged educational level. Appraisal-only conceptions, for example, involve a different suite of abilities than constructive-only conceptions. Some lists, such as those in (Glaser 1941), are put forward as educational objectives for secondary school students, whereas others are proposed as objectives for college students (e.g., Facione 1990a).

The abilities described in the remaining paragraphs of this section emerge from reflection on the general abilities needed to do well the thinking activities identified in section 6 as components of the critical thinking process described in section 5 . The derivation of each collection of abilities is accompanied by citation of sources that list such abilities and of standardized tests that claim to test them.

Observational abilities : Careful and accurate observation sometimes requires specialist expertise and practice, as in the case of observing birds and observing accident scenes. However, there are general abilities of noticing what one’s senses are picking up from one’s environment and of being able to articulate clearly and accurately to oneself and others what one has observed. It helps in exercising them to be able to recognize and take into account factors that make one’s observation less trustworthy, such as prior framing of the situation, inadequate time, deficient senses, poor observation conditions, and the like. It helps as well to be skilled at taking steps to make one’s observation more trustworthy, such as moving closer to get a better look, measuring something three times and taking the average, and checking what one thinks one is observing with someone else who is in a good position to observe it. It also helps to be skilled at recognizing respects in which one’s report of one’s observation involves inference rather than direct observation, so that one can then consider whether the inference is justified. These abilities come into play as well when one thinks about whether and with what degree of confidence to accept an observation report, for example in the study of history or in a criminal investigation or in assessing news reports. Observational abilities show up in some lists of critical thinking abilities (Ennis 1962: 90; Facione 1990a: 16; Ennis 1991: 9). There are items testing a person’s ability to judge the credibility of observation reports in the Cornell Critical Thinking Tests, Levels X and Z (Ennis & Millman 1971; Ennis, Millman, & Tomko 1985, 2005). Norris and King (1983, 1985, 1990a, 1990b) is a test of ability to appraise observation reports.

Emotional abilities : The emotions that drive a critical thinking process are perplexity or puzzlement, a wish to resolve it, and satisfaction at achieving the desired resolution. Children experience these emotions at an early age, without being trained to do so. Education that takes critical thinking as a goal needs only to channel these emotions and to make sure not to stifle them. Collaborative critical thinking benefits from ability to recognize one’s own and others’ emotional commitments and reactions.

Questioning abilities : A critical thinking process needs transformation of an inchoate sense of perplexity into a clear question. Formulating a question well requires not building in questionable assumptions, not prejudging the issue, and using language that in context is unambiguous and precise enough (Ennis 1962: 97; 1991: 9).

Imaginative abilities : Thinking directed at finding the correct causal explanation of a general phenomenon or particular event requires an ability to imagine possible explanations. Thinking about what policy or plan of action to adopt requires generation of options and consideration of possible consequences of each option. Domain knowledge is required for such creative activity, but a general ability to imagine alternatives is helpful and can be nurtured so as to become easier, quicker, more extensive, and deeper (Dewey 1910: 34–39; 1933: 40–47). Facione (1990a) and Halpern (1998) include the ability to imagine alternatives as a critical thinking ability.