Friday Essay: an introduction to Confucius, his ideas and their lasting relevance

Senior Lecturer in Chinese Studies, The University of Western Australia

Disclosure statement

Yu Tao does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Western Australia provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

The man widely known in the English language as Confucius was born around 551 BCE in today’s southern Shandong Province. Confucius is the phonic translation of the Chinese word Kong fuzi 孔夫子, in which Kong 孔 was his surname and fuzi is an honorific for learned men.

Widely credited for creating the system of thought we now call Confucianism, this learned man insisted he was “not a maker but a transmitter”, merely “believing in and loving the ancients”. In this, Confucius could be seen as acting modestly and humbly, virtues he thought of highly.

Or, as Kang Youwei — a leading reformer in modern China has argued — Confucius tactically framed his revolutionary ideas as lost ancient virtues so his arguments would be met with fewer criticisms and less hostility.

Confucius looked nothing like the great sage in his own time as he is widely known in ours. To his contemporaries, he was perhaps foremost an unemployed political adviser who wandered around different fiefdoms for some years, attempting to sell his political ideas to different rulers — but never able to strike a deal.

It seems Confucius would have preferred to live half a millennium earlier, when China — according to him — was united under benevolent, competent and virtuous rulers at the dawn of the Zhou dynasty. By his own time, China had become a divided land with hundreds of small fiefdoms, often ruled by greedy, cruel or mediocre lords frequently at war.

But this frustrated scholar’s ideas have profoundly shaped politics and ethics in and beyond China ever since his death in 479 BCE. The greatest and the most influential Chinese thinker, his concept of filial piety, remains highly valued among young people in China , despite rapid changes in the country’s demography.

Despite some doubts as to whether many Chinese people take his ideas seriously, the ideas of Confucius remain directly and closely relevant to contemporary China.

This situation perhaps is comparable to Christianity in Australia. Although institutional participation is in constant decline, Christian values and narratives remain influential on Australian politics and vital social matters .

The danger today is in Confucianism being considered the single reason behind China’s success or failure. The British author Martin Jacques, for example, recently asserted Confucianism was the “biggest single reason” for East Asia’s success in the handling of the COVID-19 pandemic, without giving any explanation or justification.

If Confucius were alive, he would probably not hesitate to call out this solitary root of triumph or disaster as being lazy, incorrect and unwise.

Political structure and mutual responsibilities

Confucius wanted to restore good political order by persuading rulers to reestablish moral standards, exemplify appropriate social relations, perform time-honoured rituals and provide social welfare.

He worked hard to promote his ideas but won few supporters. Almost every ruler saw punishment and military force as shortcuts to greater power.

It was not until 350 years later during the reign of the Emperor Wu of Han that Confucianism was installed as China’s state ideology.

But this state-sanctioned version of Confucianism was not an honest revitalisation of Confucius’ ideas. Instead, it absorbed many elements from rival schools of thought, notably legalism , which emerged in the latter half of China’s Warring States period (453–221 BCE). Legalism argued efficient governance relies on impersonal laws and regulations — rather than moral principles and rites.

Like most great thinkers of the Axial Age between the 8th and 3rd century BCE, Confucius did not believe everyone was created equal.

Similar to Plato (born over 100 years later), Confucius believed the ideal society followed a hierarchy. When asked by Duke Jing of Qi about government, Confucius famously replied:

let the ruler be a ruler; the minister, a minister; the father, a father; the son, a son.

However it would be a superficial reading of Confucius to believe he called for unconditional obedience to rulers or superiors. Confucius advised a disciple “not to deceive the ruler but to stand up to them”.

Confucius believed the legitimacy of a regime fundamentally relies on the confidence of the people. A ruler should tirelessly work hard and “lead by example”.

Like in a family, a good son listens to his father, and a good father wins respect not by imposing force or seniority but by offering heartfelt love, support, guidance and care.

In other words, Confucius saw a mutual relationship between the ruler and the ruled.

Love and respect for social harmony

To Confucius, the appropriate relations between family members are not merely metaphors for ideal political orders, but the basic fabrics of a harmonious society.

An essential family value in Confucius’ ideas is xiao 孝, or filial piety, a concept explained in at least 15 different ways in the Analects, a collection of the words from Confucius and his followers.

Read more: Can Ne Zha, the Chinese superhero with $1b at the box office, teach us how to raise good kids?

Depending on the context, Confucius defined filial piety as respecting parents, as “never diverging” from parents, as not letting parents feel unnecessary anxiety, as serving parents with etiquette when they are alive, and as burying and commemorating parents with propriety after they pass away.

Confucius expected rulers to exemplify good family values. When Ji Kang Zi, the powerful prime minister of Confucius’ home state of Lu asked for advice on keeping people loyal to the realm, Confucius responded by asking the ruler to demonstrate filial piety and benignity ( ci 慈).

Confucius viewed moral and ethical principles not merely as personal matters, but as social assets. He profoundly believed social harmony ultimately relies on virtuous citizens rather than sophisticated institutions.

In the ideas of Confucius, the most important moral principle is ren 仁, a concept that can hardly be translated into English without losing some of its meaning.

Like filial piety, ren is manifested in the love and respect one has for others. But ren is not restricted among family members and does not rely on blood or kinship. Ren guides people to follow their conscience. People with ren have strong compassion and empathy towards others.

Translators arguing for a single English equivalent for ren have attempted to interpret the concept as “benevolence”, “humanity”, “humanness” and “goodness”, none of which quite capture the full significance of the term.

The challenge in translating ren is not a linguistic one. Although the concept appears more than 100 times in the Analects, Confucius did not give one neat definition. Instead, he explained the term in many different ways.

As summarised by China historian Daniel Gardner , Confucius defined ren as:

to love others, to subdue the self and return to ritual propriety, to be respectful, tolerant, trustworthy, diligent, and kind, to be possessed of courage, to be free from worry, or to be resolute and firm.

Instead of searching for an explicit definition of ren , it is perhaps wise to view the concept as an ideal type of the highest and ultimate virtue Confucius believed good people should pursue.

Relevance in contemporary China

Confucius’ thinking hs had a profound impact on almost every great Chinese thinker since. Based upon his ideas, Mencius (372–289 BCE) and Xunzi (c310–c235 BCE) developed different schools of thought within the system of Confucianism.

Arguing against these ideas, Mohism (4th century BCE), Daoism (4th century BCE), Legalism (3rd century BCE) and many other influential systems of thought emerged in the 400 years after Confucius’ time, going on to shape many aspects of the Chinese civilisation in the last two millennia.

Modern China has a complicated relationship with Confucius and his ideas.

Since the early 20th century, many intellectuals influenced by western thought started denouncing Confucianism as the reason for China’s national humiliations since the first Opium War (1839-42).

Confucius received fierce criticism from both liberals and Marxists .

Hu Shih , a leader of China’s New Culture Movement in the 1910s and 1920s and an alumnus of Columbia University , advocated overthrowing the “House of Confucius”.

Mao Zedong, the founder of the People’s Republic of China, also repeatedly denounced Confucius and Confucianism. Between 1973 and 1975, Mao devoted the last political campaign in his life against Confucianism.

Read more: To make sense of modern China, you simply can't ignore Marxism

Despite these fierce criticisms and harsh persecutions, Confucius’ ideas remain in the minds and hearts of many Chinese people, both in and outside China.

One prominent example is PC Chang , another Chinese alumnus of Columbia University, who was instrumental in drafting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights , proclaimed by the United Nations General Assembly in Paris on December 10 1948. Thanks to Chang’s efforts , the spirit of some most essential Confucian ideas, such as ren , was deeply embedded in the Declaration.

Today, many Chinese parents, as well as the Chinese state, are keen children be provided a more Confucian education .

In 2004, the Chinese government named its initiative of promoting language and culture overseas after Confucius, and its leadership has been enthusiastically embracing Confucius’ lessons to consolidate their legitimacy and ruling in the 21st century.

Read more: Explainer: what are Confucius Institutes and do they teach Chinese propaganda?

- Chinese history

- Friday essay

- Chinese politics

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Senior Disability Services Advisor

Deputy Social Media Producer

Associate Professor, Occupational Therapy

GRAINS RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION CHAIRPERSON

ENCYCLOPEDIC ENTRY

Confucianism.

Confucianism is one of the most influential religious philosophies in the history of China, and it has existed for over 2,500 years. It is concerned with inner virtue, morality, and respect for the community and its values.

Religion, Social Studies, Ancient Civilizations

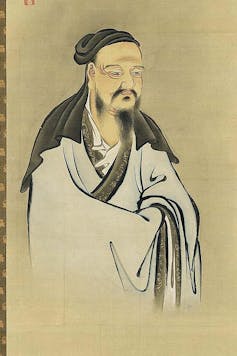

Confucian Philosopher Mencius

Confucianism is an ancient Chinese belief system, which focuses on the importance of personal ethics and morality. Whether it is only or a philosophy or also a religion is debated.

Photograph by Historica Graphica Collection/Heritage Images/Getty Images, taken from Myths and Legends of China

Confucianism is a philosophy and belief system from ancient China, which laid the foundation for much of Chinese culture. Confucius was a philosopher and teacher who lived from 551 to 479 B.C.E. His thoughts on ethics , good behavior, and moral character were written down by his disciples in several books, the most important being the Lunyu . Confucianism believes in ancestor worship and human-centered virtues for living a peaceful life. The golden rule of Confucianism is “Do not do unto others what you would not want others to do unto you.” There is debate over if Confucianism is a religion. Confucianism is best understood as an ethical guide to life and living with strong character. Yet, Confucianism also began as a revival of an earlier religious tradition. There are no Confucian gods, and Confucius himself is worshipped as a spirit rather than a god. However, there are temples of Confucianism , which are places where important community and civic rituals happen. This debate remains unresolved and many people refer to Confucianism as both a religion and a philosophy. The main idea of Confucianism is the importance of having a good moral character, which can then affect the world around that person through the idea of “cosmic harmony.” If the emperor has moral perfection, his rule will be peaceful and benevolent. Natural disasters and conflict are the result of straying from the ancient teachings. This moral character is achieved through the virtue of ren, or “humanity,” which leads to more virtuous behaviours, such as respect, altruism , and humility. Confucius believed in the importance of education in order to create this virtuous character. He thought that people are essentially good yet may have strayed from the appropriate forms of conduct. Rituals in Confucianism were designed to bring about this respectful attitude and create a sense of community within a group. The idea of “ filial piety ,” or devotion to family, is key to Confucius thought. This devotion can take the form of ancestor worship, submission to parental authority, or the use of family metaphors, such as “son of heaven,” to describe the emperor and his government. The family was the most important group for Confucian ethics , and devotion to family could only strengthen the society surrounding it. While Confucius gave his name to Confucianism , he was not the first person to discuss many of the important concepts in Confucianism . Rather, he can be understood as someone concerned with the preservation of traditional Chinese knowledge from earlier thinkers. After Confucius’ death, several of his disciples compiled his wisdom and carried on his work. The most famous of these disciples were Mencius and Xunzi, both of whom developed Confucian thought further. Confucianism remains one of the most influential philosophies in China. During the Han Dynasty, emperor Wu Di (reigned 141–87 B.C.E.) made Confucianism the official state ideology. During this time, Confucius schools were established to teach Confucian ethics . Confucianism existed alongside Buddhism and Taoism for several centuries as one of the most important Chinese religions. In the Song Dynasty (960–1279 C.E.) the influence from Buddhism and Taoism brought about “Neo- Confucianism ,” which combined ideas from all three religions. However, in the Qing dynasty (1644–1912 C.E.), many scholars looked for a return to the older ideas of Confucianism , prompting a Confucian revival.

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Production Managers

Program specialists, last updated.

March 6, 2024

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

17 Confucianism in Mainland China

Tongdong Bai is Professor of Philosophy and the director of an English-based MA program in Chinese philosophy at Fudan University in China. His publications in English include Against Political Equality: The Confucian Case (Princeton, 2019) and China: The Political Philosophy of the Middle Kingdom (Zed Books, 2012).

- Published: 26 January 2023

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Although Confucianism has been on the defensive for much of the past 150 years, it has experienced renewal and growth in the past 40 years in mainland China. This essay will contextualize the attacks of Confucianism in the early People’s Republic of China, the beginnings of a Confucian revival in the 1980s, and the factors that have led to new modes of Confucianism in the past several decades, including works by the older generations and their students, the influence of Overseas New Confucianism, and since the new millennium, a growing minority among mainland Confucian sympathizers, the so-called Mainland New Confucians. This essay looks in particular at the Mainland New Confucianism, arguing that it may be more promising than Overseas New Confucianism in offering critical and constructive ideas relevant not only to China, but to the wider world.

Groundwork: The Republican Era

Through much of traditional Chinese history, Chinese considered themselves the center of the human civilization. There were occasional military defeats, usually by horse-riding nomads from the hinterlands, but to rule China, apparently, the conquerors had to adopt the Chinese way of politics and life. Confucianism, as the official ideology of the state for much of imperial China, was considered to contain “universal values,” values any civilized people would adopt. But this perception changed after defeats in the nineteenth century by Western powers and then the Japanese: this time, the conquerors seemed to prevail on account of better technologies, better political institutions, and even better culture. Confucianism was blamed as a root cause of a weak China, and to radicals, China needed to “smash down Confucianism” (打倒孔家店) in order to embrace democracy and science based on a new culture.

The Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT/Kuomintang or GMD/Guomindang) that controlled China in the first half of the twentieth century was an anti-traditionalist and Leninist party. But in order to distinguish itself from the even more radical Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the KMT would sometimes present itself as the legitimate heir and a protector of the tradition, and Confucian institutions and values on the grassroots level were not intentionally attacked by the KMT. But many elites did attack the tradition. For example, though apparently a scholar of traditional subjects, Hu Shih 胡适 turned a living tradition into dead, museum objects with the slogan, “sorting out the old things of the [Chinese] nation” (整理国故). 1 This partly explains an apparently paradoxical phenomenon in the greater China: many experts on Chinese traditions are themselves often staunch anti-traditionalists.

Fu Sinian 傅斯年, a follower of Hu, was openly hostile to a philosophical approach to Confucianism. It is partly due to his legacy that Academia Sinica (moved to Taiwan after 1949) did not have an Institute of Philosophy until the late 1980s. The contemporary scholar Zheng Jiadong郑家栋 argues that Fu was once interested in philosophy, and he changed his attitude because of his disgust toward the kind of philosophy he encountered, German philosophy. 2 Those who embraced the philosophical approach to Confucianism, interestingly, often shared Fu’s misplaced identity between (Western) philosophy and German philosophy. This legacy from the Republican era would shape the approach to Confucianism in the People’s Republic.

The Cultural Desert: The First Thirty Years in the People’s Republic

In 1949 the CCP took over China, and Confucianism was openly rejected as the “dross of feudal despotism” (封建专制的糟粕). Confucian institutions and values were thoroughly attacked at every level, culminating in the Cultural Revolution. Any attempt to approach Confucianism as a live and viable tradition was completely suppressed because only Marxism could be approached as such. 3 Liang Shuming梁漱溟 was a rare exception who fared better than other Confucians due to his close ties with Mao before the Communist takeover, and the fact that his idea of “village construction” (乡村建设) resonated somewhat with CCP’s agenda. But even he soon fell out of favor due to the personal and ideological conflicts with Mao and Maoist projects. Fung Yu-lan 冯友兰 (spelled as “Feng Youlan” in pinyin), an important Confucian philosopher in the twentieth century, had been invited to stay in the United States during a visit but rejected the offer because he felt that Confucianism was regarded as a curiosity item in a museum. 4 But soon after he returned in 1947, he could only study Confucianism through the “Marxist” lens as described by the Soviet and then Chinese authorities, that is, only as a dead object in the new “Marxist/Communist museum.” Even worse, this dead object was completely destroyed during the Cultural Revolution, and Fung himself was involved in the destruction projects, such as the notorious liang xiao 梁效 group.

Generally speaking, in the first thirty years of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), any study of Chinese philosophy had to use the “two pairs of opposites” method introduced by the Soviet ideologue Andrei Alexandrovich Zhdanov, and as a result, the history of Chinese philosophy was analyzed and reconstructed as battles between materialism and idealism, and between dialectics and metaphysics. 5 The linguistic, classical, and historical studies of Confucianism fared a little better, because most of them already took Confucianism as a dead (and bad) object in a museum from a previous age, and these studies became a not-so-green oasis in an otherwise cultural desert. The philosophically minded could retreat to the study of German idealism, one of the few areas of philosophy the authority deemed important because of its close connection to Marxism. As mentioned earlier, “Western philosophy” was already identified with German philosophy, and this move reinforced that idea, laying ground of a biased philosophical approach to Chinese philosophy that has lasted beyond Mao.

The Return of Old Scholars and Old Traditions: The 1980s and 1990s

“I have had few achievements in my life; the only one is that I have survived.” These words were spoken by Zhang Dainian 张岱年, a relative of Fung Yu-lan and an important scholar of Chinese philosophy, in a conference celebrating his scholarly achievements. 6 The humor, the sadness, and the repressed anger is palpable, and this dry understatement vividly reflects the fate of Confucian scholarship during the Mao era. 7

After Mao’s death, universities were reopened after being almost completely shut down during the Cultural Revolution. Older scholars such as Zhang could teach the next generation of Confucian scholars and intellectuals. Many works from the Republican era were republished, such as Zhang’s An Outline of Chinese Philosophy 中国哲学大纲; some new works were written to redress what they were forced to say during the Mao era, such as Fung’s volume 7 of The New History of Chinese Philosophy 中国哲学史新编. Other scholars, such as Jin Jingfang金景芳, Pang Pu庞朴, and Li Zehou李泽厚, criticized how Confucianism was treated and “studied” in the Mao era, and suggested new methods of studies. 8

However, the dominant mood among intellectuals in the 1980s was “re-Enlightenment,” which meant re-Westernization or re-modernization and another round of attacks on Chinese traditions. 9 The latter were and still are vilified as the root cause of the Cultural Revolution, the consummation of anti-traditional movements in China, as well as other ills of contemporary China, despite the fact that these traditions have been vehemently attacked for the past 150 years!

There was, however, a dramatic shift, a highly visible revival of Confucianism in the 1990s. The Westernization movement was suppressed by the state after 1989, and many Chinese pro-Western “liberals” became disillusioned. 10 The latter once had a rosy image of a benevolent West that has no national interests and only wants to promote democracy for those suffering in authoritarian or despotic regimes, and they were shocked to see that, for example, instead of helping the ordinary Russians who were suffering, the Western nations apparently took advantage of the collapse of the Soviet Union, regarding only their own national interests. With Maoism challenged in the 1980s, and Western values suppressed or questioned in the 1990s, China faced a spiritual and political vacuum. At the same time, China’s economy was rising fast, and this rise, together with the economic rise of East Asia, challenged the Weberian thesis that Protestantism was crucial for capitalism and economic development, while Confucianism was an obstacle. The democratization of Taiwan and South Korea—two societies that have better preserved Confucian values than mainland China—challenged the Huntingtonian “clash of civilizations” thesis. These developments removed the stigma placed on Confucianism, and gave a new-found confidence in Chinese traditions.

A variety of events during the 1980s and 1990s also contributed to the Confucian revival, including governmental and quasi-governmental organized conferences promoting Confucianism. For example, Tang Yijie 汤一介 and others established centers sponsoring conferences and public events, and published journals that some point to as the beginning of the guo xue 国学 (national/traditional learnings) wave. 11

To those who believe that the Western way is the only way and thus any suggestion of an alternative must have a nefarious agenda, this revival is the result of governmental manipulation of a credulous public by promoting a thinly disguised nationalism after the collapse of Maoism. But this suspicion is one-sided because there are also innate factors that lead people to embrace Confucianism, as I have argued. Even in terms of manipulation, a tug of war is still going on, and the manipulators can eventually become the manipulated if governmental promotion helps scholars to present and people to embrace a kind of Confucianism that the government finds inconvenient but has to accept due to its popularity.

Introduction of Overseas New Confucianism

In the Confucian revival, one group of scholars were instructed or inspired by the works of scholars from the previous generation such as Fung Yu-lan, Zhang Dainian, Jin Yuelin 金岳霖, and He Lin 贺麟. Scholars in this group include Tang Yijie 汤一介, Feng Qi 冯契, Zhang Liwen 张立文, Meng Peiyuan 蒙培元, Yu Dunkang 余敦康, Feng Dawen 冯达文, and Wang Shuren 王树人. 12 Because of the disruption of higher education during the Cultural Revolution, these scholars were part of a very small group of doctoral advisers in the 1990s, producing the majority of scholars for more than a decade. Their exposure to and engagement with wider philosophical conversations, particularly with the West, is often limited, and as a result, to anyone trained in philosophy from the West their works can appear incomprehensible or simplistic—for example, claiming that environmental issues can be solved by the Confucian idea of the unity between Heaven and the human. 13

Another group of scholars continued the earlier generations’ work in intellectual history, which was somewhat permitted in the Mao era. A leading scholar in this group is Chen Lai 陈来, whose works on the intellectual history of Confucianism, especially Neo-Confucianism, have been considered authoritative. While these works clearly contribute to the Confucian revival, they are more an intellectual history than philosophy. 14

But Confucianism is a challenging topic, particularly when it is approached as a live and still viable tradition, and isolation from the global academic community under Mao only intensified this problem. For this reason Overseas New Confucianism ( hai wai or gang tai xin ru jia 海外/港台新儒家) has played a significant role in the Confucian revival in the mainland: it was not suppressed by the Hong Kong and Taiwanese governments, and it is concerned with the issue of the relevance of Confucianism to today’s world.

The seed for the influence of Overseas New Confucianism in the PRC was planted in the 1980s. Tu Weiming 杜维明, an important Overseas New Confucian, visited China, including Peking University. 15 Around the same time, Fang Keli 方克立, an orthodox Marxist in the PRC, and some of his students and colleagues focused on criticizing Overseas New Confucianism. 16 Though often hostile to Confucianism in its contemporary iterations, 17 their works, ironically, have contributed to the Confucian revival in mainland China through their introduction and discussion of Overseas New Confucianism. Some scholars from Fang’s camp have even “converted” and become defenders of Confucian values.

During the Confucian revival in the 1990s, Overseas New Confucianism became dominant among mainland scholars of Confucianism, and it has remained influential to today. Mainland scholars such as Guo Qiyong 郭齐勇, Yan Bingang 颜秉罡, and Jing Haifeng 景海峰 have played important roles in promoting Overseas New Confucianism in the mainland. But as was stated earlier, the model of philosophy for most thinkers in the Republican era was German philosophy, and Overseas New Confucianism has preserved this biased view of philosophy. Mou Zongsan’s 牟宗三 school of Confucianism draws heavily on Kant, and Lee Ming-hue 李明辉, an important Confucian philosopher from Mou’s school, has noted that the philosophical resources and inspirations for Overseas New Confucianism are continental philosophy, especially German idealism, with little attention paid to the Anglo-American tradition. 18 The importance of German idealism as an intellectual refuge under Mao facilitated the embrace of Overseas New Confucianism by mainland scholars.

Similar to May Fourth radicals, most Overseas New Confucians and their mainland followers are committed to the universal values of democracy and science. They differ in thinking that Confucianism, as a spiritual doctrine or a moral metaphysics, is not in conflict with democracy and science. Their criticisms of Western societies are limited to Western ethics and its social and cultural applications, not at fundamental political institutions. They reject traditional Chinese political regimes as feudalistic, authoritarian, and even despotic, and they link the political dimension of Confucianism to the defense of bad politics and rulers of traditional China. 19 Following this assessment it would be little more than perverse curiosity to take seriously the political aspect of Confucianism. Overseas New Confucians and their mainland followers thus look at Confucianism primarily from a moral-metaphysical perspective, and this focus on metaphysics is reinforced by the influence of German idealism. It limits and biases their understanding and reconstruction of Confucian traditions, and it also needs to justify itself against the anti-metaphysical and pluralistic challenges raised by many philosophers in the analytic tradition.

Rise of Mainland New Confucianism

A new form of Confucianism, Mainland New Confucianism or political Confucianism, has been a fast-growing minority among mainland Confucian sympathizers since the turn of the millennium. 20 The term could refer to the ideas of any mainland scholar sympathetic to Confucianism; 21 in this essay the term is used in contrast to Overseas New Confucianism, especially in the former’s focus on the political aspect of Confucianism rather than moral metaphysics. Thus, Mainland New Confucians are also called “political Confucians.” Overseas New Confucians also pay attention to the political implication of Confucianism, but they consider the latter to be derivative from their moral metaphysics. But Mainland New Confucians consider the political aspects of Confucianism equally fundamental, and some of them even argue that the moral metaphysics is secondary to the political, or even dispensable.

Mainland New Confucians also reject the conviction that traditional Chinese regimes are simply authoritarian and defend the merits of these regimes. This stance is intertwined with a critical attitude toward Western institutions. They illustrate and develop Confucian political elements to address the failings of Western democracy and the present world order, suggesting the application of Confucian political ideas even globally.

According to Zeng Hailong, the term “Mainland New Confucianism” was introduced by Fang Keli. According to Fang, an article by Jiang Qing 蒋庆, published, ironically, in the key Overseas New Confucian journal, E Hu 鹅湖, in Taiwan, entitled “The Practical Implications of Reviving Confucianism in Mainland China and the Problems It Faces” (中国大陆复兴儒学的现实意义及其面临的问题) (1989), should be considered a Mainland New Confucian manifesto, comparable to the far more famous 1958 Overseas New Confucian one, “A Manifesto to All People in the World on Behalf of Chinese Culture” (为中国文化敬告世界人士宣言). He also noticed the important role of Yuan Dao 原道 for this newly emerging group. 22 At first, Fang didn’t distinguish between the Overseas and Mainland New Confucians: to him, both groups are culturally conservative, of which he, an “old-guard” Marxist, is highly critical. 23

In 2004, a Confucian-style symposium ( hui jiang 会讲) with four main speakers took place at a Confucian-style academy, Yang Ming Jing She 阳明精舍 in Guizhou province, an academy founded by Jiang Qing. Now Fang noted the difference between Mainland and Overseas New Confucians: the shift from xin-xing 心性 (moral-metaphysical) Confucianism to political Confucianism, and from the revival of Confucianism as a teaching ( ru xue 儒学) to the revival of Confucianism as a religion ( ru jiao 儒教). 24 This observation is incisive, but Fang still fails to make it explicit that rather than focusing on merely private moral cultivation, Mainland New Confucianism is centered on the importance of Confucianism in the public sphere.

Many Mainland New Confucians have been inspired or influenced by Jiang Qing. Jiang used a lot of the Gongyang Commentaries (春秋公羊传) in his version of Confucianism, and identified with “New Text Confucianism” ( jin wen jing xue 今文经学). 25 In this he followed Kang Youwei 康有为, a late Qing and early Republican Confucian who used the same resources. For this reason, some Mainland New Confucians are referred to as members of the New Kang Youwei School (新康有为主义者) or more jokingly, as Kang Party members (康党).

There has been a conflation of Jiang’s group with Mainland New Confucians in general. Even within the “Kang Party,” there are intellectuals with different and even mutually incompatible agendas (Kang Youwei himself had incoherent and often changing agendas). Younger scholars such as Zeng Yi 曾亦 and Chen Bisheng 陈壁生 focus more on Kang Youwei’s so-called jing xue 经学 approach—a particular and controversial kind of hermeneutic approach—to Confucian canons. Like Jiang, Zeng focuses more on its institutional implications; Chen centers on the scholarly studies of this approach to Confucianism. Gan Chunsong 干春松, a former student of Fang Keli’s, engages in the institutional and political implications of Confucianism, particularly Kang Youwei’s thought, but is far more liberal than Jiang. Together with Tang Wenming 唐文明 and Chen Ming, Gan also focuses on the issue of Confucian religion, kong jiao 孔教, another issue introduced by Kang Youwei. Gan and Chen take jiao more as jiao hua 教化 (transformation through moral and civil teachings), or “civil religion” ( gong ming zong jiao 公民宗教), whereas Tang uses the term jiao more in line with religions such as Christianity.

Other political Confucians have little to do with either Kang or Jiang. Chen Ming, one of the four speakers in the 2004 Confucian symposium and a member of the New Kang Youwei School, had his original point of contact with political Confucianism not via Jiang; he was a student of the aforementioned scholar Yu Dunkang. Two others from the 2004 symposium are even less connected with Jiang. With a background in statistics, Kang Xiaoguang 康晓光 has done works in polling and social analysis, and he has been involved with charity organizations. He brings Confucian concerns to this work and is more an activist than a theorist.

Sheng Hong 盛洪was trained as a Hayekian economist, and the executive director of the Unirule Institute of Economics, a pro-free-market think-tank that had been recently disbanded by the government. He has argued that Confucianism is in line with Hayekian free-market economy, and Confucian ideas and practices make economic sense. Pro-market Chinese intellectuals are usually critical of traditional Chinese society, and thus Sheng is quite unusual. Another important Mainland New Confucian, Yao Zhongqiu 姚中秋, also known as Qiu Feng秋风, was likewise a member of the Unirule Institute and a translator of Friedrich Hayek’s works, although he has recently become a vocal defender of the Chinese state. A student of Hayek’s who fled to Taiwan after the communist takeover, Zhou Dewei 周德伟, was also highly sympathetic to Confucianism. The Hayekian connection with Confucianism and the economic perspective on Confucianism that is brought by Sheng Hong and others is refreshing, further broadening the “Way” of Confucianism.

A minority group within Mainland New Confucianism is the “Qian Party” (钱党), a label half-jokingly coined by me in a conference that was seen as the official debut of the New Kang Youwei School. Several at the conference were not influenced by Jiang or Kang, but admired the works of the Chinese historian Qian Mu 钱穆, thus the coining of this term. In this group, Ren Feng 任锋is an expert on the Zhe Dong 浙东 School of Confucianism and other more politically and socially oriented Confucians in later imperial China. My own scholarship came to align with political Confucianism partly through my appreciation of John Rawl’s defense of pluralism, a conviction of the limit and even futility of any attempt to reconstruct moral metaphysics that is meant to have a broader appeal, and my early ideas about Confucian political institutions were inspired by the work of Daniel Bell. In spite of the different foci, both Ren and I (as well as other members of the Qian Party) found connections between our works and Qian’s analysis of and charitable attitude toward traditional Chinese political regimes.

Many Mainland New Confucians from the “Kang Party” are ultra-conservative, comparable to the religious ultra-conservatives in the West, while “Qian Party” members tend to be more liberal and less anti-Western. For example, when news spread to China that Justice Kennedy had quoted Confucius in the U.S. Supreme Court majority opinion that legalized same-sex marriages, many Kang Party members were furious, calling homosexuality an “abomination.” 26 Some are also strongly nationalistic and anti-Western, and their anti-Western attitude and claims are often a mirror image of the claims of anti-traditional radicals, whom they condemn, in that they claim that “West is bad, and China is good” as frivolously as the radicals claim “China is bad, and West is good.” Some Mainland New Confucians are hostile to a philosophical approach to Confucianism. As indicated above, the “philosophy” to which they object has been heavily influenced by German idealism. It is likely that the Mainland New Confucians are, unwittingly, merely objecting to this biased version of philosophy. 27

Two more thinkers important to the Confucian revival in mainland China are difficult to categorize in the framework presented here. Li Zehou’s 1980 article, mentioned earlier, calling for a reevaluation of Confucius was quite influential at the time; he is also a very vocal critic of Overseas New Confucians’ neglect of the political dimension of Confucianism. However, his constructive works on Confucianism have drawn on intellectual resources such as Marxism and more recent developments in moral psychology and evolutionary ethics. Zhang Xianglong 张祥龙 was trained in the U.S. with a focus on Heidegger. He is not a follower of Overseas New Confucianism, but he is not as a vocal critic of it as Li. Drawing on Heidegger and continental philosophy, Zhang offers Confucianism-inspired philosophical evaluations of Chinese history and other social and political issues, and makes his own practical proposals. His sympathy to traditional Chinese culture and institutions, his critical attitude toward the West, and his effort at offering practical proposals would align him with Mainland New Confucians except for his reliance on Heideggerian metaphysics. 28

In addition to political Confucians and Confucians who are influenced by Overseas New Confucians, other Confucian sympathizers have also promoted Confucianism in society among the common people ( min jian ru xue 民间儒学). 29 The difference, if any, is that for the former, this work is important because the social is part of the political and the institutional, while for the latter, this work is important because the political situations can only be improved if we improve the morals of the individuals in a society.

In spite of the aforementioned problems it would seem that Mainland New Confucianism, including works by Li Zehou and Zhang Xianglong, is more promising than Overseas New Confucianism and its mainland followers’ ideas. The latter appears to be “cheerleading” Western political, scientific, and technological institutions, and only defending Confucianism on the moral-metaphysical ground, which is doomed to be merely one of many comprehensive doctrines in a pluralistic society. When liberal democracy and pluralism become a social reality, this version of New Confucianism has little left to address, which is perhaps why Overseas New Confucianism has little influence in already democratized and pluralistic Taiwan. In contrast, Mainland New Confucians, whatever their deficiencies, work to engage the West in the political, economic, and social fields, making it more likely to offer “universalizable” answers to globally shared issues.

Acknowledgments

The research for this chapter is supported by the Program for Professor of Special Appointment (Eastern Scholar, second term) at Shanghai Institutions of Higher Learning.

1. Here I borrow the metaphor of the sinologist Joseph Levenson, who claimed that Confucianism has undergone a “museumization” in the past hundred or more years; Joseph R. Levenson , Confucian China and Its Modern Fate (Berkeley: University of California Press,1968), 160 .

2. Zheng, Jiadong 郑家栋, “Writing ‘History of Chinese Philosophy’ and the Modern Dilemma of Traditional Chinese Thought” ‘中国哲学史’写作与中国思想传统的现代困境, Renmin University Journal , no. 3 (2004), 4 . Many of the works I refer to in this article are in Chinese, and I won’t list them in the Bibliography. They can be found by searching for the scholars who are mentioned in this chapter or in one of the following review articles: Cunshan Li 李存山, “Forty Years of the Studies of Chinese Philosophy” 中国哲学研究四十年, in Chinese Philosophical Almanac 中国哲学年鉴 (Beijing: China Social Science Press, 2018), 22–29 ; and Qiyong Guo 郭齐勇 and Xiaowei Liao 廖晓炜, “Confucian Studies in the Forty Years of China’s Reform and Opening-Up” 改革开放四十年儒学研究, Confucian Academy: Chinese Thought and Culture Review 孔学堂·中国思想文化评论5 (3 September 2018), 5–14 [Chinese] and 6–15 [English].

See also Li, “Forty Years.”

4. Youlan Feng , The Complete Collections of San Song Tang 三松堂全集 (2nd ed.) (Zhengzhou: Henan Renmin 2001), vol. 1, 108 .

Li, “Forty Years.”

6. Zhang was a professor at Peking University when I studied there, and this line was reported to us by a teacher whose class I was taking. It was also mentioned in Ding Yin 殷鼎, Fung Yu-lan 冯友兰 (Taipei: Dong Da Press 东大图书公司, 1991), 5 . Yin said that it was a claim made in a conference dedicated to the sixty-year anniversary of Zhang’s teaching. According to Chen Lai陈来, Zhang started teaching in 1933 ( https://phil.pku.edu.cn/xwgg/xzxw/xzdt/491194.htm ), and the sixty-year anniversary would take place in the year of 1993, two years after the publication of Yin’s book. It is likely that Yin made a mistake here.

There are two excellent reviews (in Chinese) of the fate of Confucianism in the last forty years in China: Li, “Forty Years” and Guo and Liao, “Confucian Studies.” Many of their observations resonate with mine, and they (especially Guo and Liao) contain a large number of references, including earlier reviews of similar nature (over shorter periods), in Chinese. The journal that publishes Guo and Liao includes English translations of all the articles in the same issue, so readers who don’t read Chinese can read the English version of this article. In this chapter, I use the page numbers of the Chinese version of this article. In spite of the agreements, this chapter is more critical of the role of German philosophy in the field of Chinese philosophy, Confucianism included, and of Overseas New Confucianism. I also give more space to the discussion of the so-called Mainland New Confucianism, with more charity than Guo and Liao (Li mostly ignores this trend).

See Li, “Forty Years” and Guo and Liao, “Confucian Studies” for more details. Guo and Liao stated that Li Zehou’s article “Reevaluating Confucius” was the most influential in this group of articles (ibid., 6).

Guo and Liao, “Confucian Studies” has a similar observation (6–7).

I put “liberals” in quotation marks because they are not liberals in the American sense, but are simply pro-democracy and pro-Western.

Guo and Liao, “Confucian Studies,” 6–8.

Interested readers can either search for their names, or see Li, “Forty Years” and Guo and Liao, “Confucian Studies” for works done by these scholars.

13. For a criticism of this alleged solution, see Tongdong Bai , “Will the Idea of the Unity between Heaven and Man Solve Environmental Problems? A Chinese Philosophical Reflection on Climate Change” 天人合一能够解决环境问题么?--气候变化的政治模式反思, Exploration and Free Views 探索与争鸣, no. 12 (2015), 59–62 .

In 2014, Chen Lai published a book, Ren Xue Ben Ti Lun 仁学本体论, which marked his attempt to construct a Confucianism-based philosophical system.

See also Guo and Liao, “Confucian Studies,” 7.

16. Ibid.

Some people in his camp are hostile to Confucianism not necessarily from a Marxist perspective, but from a general pro-Western and anti-traditional “liberal” perspective.

18. Ming-huei Lee , Political Thoughts through Confucian Lens 儒家视野下的政治思想 (Taipei: National Taiwan University’s Publication Center 国立台湾大学出版中心, 2005), vii and 35.

19. See Liu Shuxian刘述先’s criticism of the “politicized Confucians” in, for example, Shuxian Liu , On the Three Epochs of Confucian Philosophy 论儒家哲学的三大时代 (Guiyang: Guizhou People’s Press 2009), 3 and 50.

20. There have been more and more discussions of Mainland New Confucianism in Chinese, but many, if not most, of them are very biased or downright hostile (see, for example, Guo and Liao, “Confucian Studies,” 10–12). For a relatively balanced and detailed review, see Hailong Zeng 曾海龙, “From Modern Confucianism to Mainland New Confucianism—with a Focus on the New Kang Youwei School” 从现代新儒家到大陆新儒家—以“新康有为主义”为中心的考察, Guo Ji Ru Xue Lun Cong 国际儒学论丛, no. 2 (2017), 19–39 (also available on https://www.rujiazg.com/article/13066 ). It is, however, focused on the “New Kang Youwei School” of Mainland New Confucianism and doesn’t offer a more comprehensive picture of this new trend.

21. This is how, for example, Guo Qiyong defines this term. See Guo , “An Overview of Contemporary New Confucian Trends” 当代新儒学思潮概览, People’s Daily (11 September 2016) .

This is a journal founded in 1994 by Chen Ming 陈明, who would be later labeled as a Mainland New Confucian.

This discussion can be found in Zeng, “From Modern Confucianism,” 23.

Zeng, “From Modern Confucianism,” 22–23. More discussion of “ ru jiao ” will be found later in this section.

25. For an overview of Jiang’s work on Confucian constitutionalism and some critical reviews (including my own), see Daniel Bell and Fan Ruiping (eds.), A Confucian Constitutional Order (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012) .

26. For some references and a Confucian endorsement of the same-sex marriage, see Tongdong Bai , “Confucianism and Same-Sex Marriage,” Politics and Religion 14, no. 1 (March 2021), 132–158, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755048320000139 .

27. For a detailed analysis of the contrast between the “Kang Party” and the “Qian Party,” the criticisms of the approach of the former, and a defense of the (political) philosophical approach, see Tongdong Bai , “ Jing Xue or Zi Xue —Reflections on How to Revive Political Confucianism” 经学还是子学—对政治儒学复兴之路的一些思考 (rev. and enl.), Philosophical Review 哲学评论 22 (2019), 1–32 .

There are some other mainland Confucian intellectuals I fail to cover in this short chapter. For example, Huang Yushun 黄玉顺 was also inspired by Heidegger and has developed his own version of Confucianism, “life Confucianism” 生活儒学.

Guo Qiyong is an example of the latter. See Guo and Liao, “Confucian Studies,” 8.

Selected Bibliography

Bai, Tongdong白彤东 . “Will the Idea of the Unity between Heaven and Man Solve Environmental Problems? A Chinese Philosophical Reflection on Climate Change ” 天人合一能够解决环境问题么?--气候变化的政治模式反思, Exploration and Free Views 探索与争鸣, no. 12 ( 2015 ), 59–62.

Bai, Tongdong 白彤东. “ Jing Xue or Zi Xue —Reflections on How to Revive Political Confucianism” 经学还是子学—对政治儒学复兴之路的一些思考” (rev. and enl.), Philosophical Review 哲学评论 22 ( 2019 ), 1–32.

Bai, Tongdong 白彤东. “ Jing Xue or Zi Xue —Reflections on How to Revive Political Confucianism” 经学还是子学—政治儒学复兴应选择何种途径, Exploration and Free Views 探索与争鸣, no. 1 (2018), 67–71. [This is an earlier version of Bai (2019).]

Bai, Tongdong 白彤东. “ How Should Confucians View the Legalization of Same-Sex Marriages? ” Politics and Religion 14, no. 1 (March 2021), 132–158, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755048320000139 .

Bell, Daniel and Fan Ruiping , eds. A Confucian Constitutional Order . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012 .

Google Scholar

Google Preview

Fung, Yu-lan [Feng, Youlan] 冯友兰. The Complete Collections of San Song Tang 三松堂全集 (2nd ed.). Zhengzhou: Henan Renmin Press, 2001 .

Guo, Qiyong 郭齐勇. “An Overview of Contemporary New Confucian Trends” 当代新儒学思潮概览, People’s Daily , September 11, 2016.

Guo, Qiyong 郭齐勇 and Xiaowei Liao 廖晓炜. “Confucian Studies in the Forty Years of China’s Reform and Opening-Up” 改革开放四十年儒学研究, Confucian Academy: Chinese Thought and Culture Review 《孔学堂·中国思想文化评论》 5, no. 3 (September 2018), 5–14 [Chinese] and 6–15 [English].

Levenson, Joseph R. Confucian China and Its Modern Fate . Berkeley: University of California Press, 1968 .

Li, Cunshan 李存山. “Forty Years of the Studies of Chinese Philosophy” 中国哲学研究四十年, in Chinese Philosophical Almanac 中国哲学年鉴, 22–29. Beijing: China Social Science Press, 2018 .

Li, Minghui [ Lee, Ming-huei ] 李明辉. Political Thoughts through Confucian Lens 儒家视野下的政治思想. Taipei: National Taiwan University’s Publication Center 国立台湾大学出版中心, 2005 .

Liu, Shuxian 刘述先. On the Three Epochs of Confucian Philosophy 论儒家这些的三大时代. Guiyang: Guizhou People’s Press, 2009 .

Yin, Ding 殷鼎. Fung Yu-lan 冯友兰. Taipei: Dong Da Press东大图书公司, 1991 .

Zeng, Hailong 曾海龙 . “From Modern Confucianism to Mainland New Confucianism—with a Focus on the New Kang Youwei School” 从现代新儒家到大陆新儒家—以“新康有为主义”为中心的考察, Guo Ji Ru Xue Lun Cong 国际儒学论丛, no. 2 ( 2017 ), 19–39. Also available on: https://www.rujiazg.com/article/13066 accessed on March 3, 2019.

Zheng, Jiadong 郑家栋, “ Writing ‘History of Chinese Philosophy’ and the Modern Dilemma of Traditional Chinese Thought ” 中国哲学史’写作与中国思想传统的现代困境, Renmin University Journal , no. 3 ( 2004 ), 2–11.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Utility Menu

GA4 Tracking Code

- Confucianism

The Scholarly Tradition

The tradition described by the neologism “Confucianism,” first used by European scholars in the 19th century, is rooted in the “The Scholarly Tradition,” of which Confucius is the most well-known practitioner. Some scholars argue that the tradition is a humanistic system of ethics, emphasizing the purification of one’s heart and mind to actively engage in familial and societal matters. Others argue that Confucianism is indeed a humanistic religious tradition, since the completion of moral cultivation is said to lead to cosmological and spiritual transcendence. ... Read more about The Scholarly Tradition

“Confucius and Sons” in America

Confucian teaching and interpretation largely became based on four key texts called The Four Books: Analects , Book of Mencius , Great Learning , and Doctrine of the Mean . East Asian immigrant communities in the United States differ in the way they view Confucian teachings: Some deem the teachings irrelevant for scientific society and democratic governance, while others uphold the teachings as an integral component of their cultural traditions. ... Read more about “Confucius and Sons” in America

To Become a Sage

To find expressions of Confucian values in the United States one must look not so much at explicit ceremonial activities, but at underlying motives as they surface in everyday life. Confucian values are often expressed among many East Asian immigrants through an emphasis on education, family cohesiveness, and self-abnegation in support of others. ... Read more about To Become a Sage

The 21st Century: A Confucian Revival?

The late 20th century saw the rise of organizations that promote Confucianism in the United States and abroad. In 2004, for instance, the Chinese government opened the Confucius Institute, a partnership with many institutions to teach Chinese language, culture, and literature. In the United States, Boston Confucianism is a growing intellectual movement that asserts that anyone, not only East Asians, can participate and learn from the Confucian tradition. ... Read more about The 21st Century: A Confucian Revival?

Confucian figures should take part in creating peaceful election: VP

Women of the red dragon: chinese mythology as a catalyst for feminism, game changer: how mahjong helped jewish and asian americans overcome racism.

- Confucius Institute

- Boston Confucianism

- Five Classics

Confucianism Timeline

93d47c446711dda147dd775e4558d38c, confucianism timeline (text), 551 - 479 bce the life of confucius.