- Please enable javascript in your browser settings and refresh the page to continue.

- Technology Research /

- Enterprise Architecture

Enterprise Architecture - Case Studies

- Infrastructure & Operations 6

- Enterprise Architecture 10

- Data & Business Intelligence 2

- Strategy & Operating Model 8

- Applications 10

- Project & Portfolio Management 8

- Data & Business Intelligence 3

- Vendor Management 8

Types of Content

- Job Descriptions 20

- Templates & Policies 176

- Case Studies 10

- Blueprints 34

- Storyboards 90

Please confirm the appointment time and click Schedule.

Your call is being booked. A representative will be available to assist you if needed.

Free Site Analysis Checklist

Every design project begins with site analysis … start it with confidence for free!

Understanding Architecture Case Studies

- Updated: February 12, 2024

History teaches us many things, and it can carry valuable lessons on how to move forward in life. In architecture , when we are faced with a project, one of the first places we can look is the past – to see what worked, what didn’t, and what we can improve for our own projects.

This process comes in the form of architecture case studies, and every project can benefit from this research.

Here we take you through the purpose, process, and pointers for conducting effective case studies in architecture.

What is an architecture case study

A case study (also known as a precedent study ) is a means of finding relevant information about a project by examining another project with similar attributes. Case studies use real-world context to analyze, form, support, and convey different ideas and approaches in design.

Simply put, architectural case studies are when you use existing buildings as references for new ones.

Architects can conduct case studies at nearly every stage of a project, adapting and relating applicable details to refine and communicate their own projects. Students can use case studies to strengthen their research and make a more compelling case for their concepts .

Regardless of the size or scale of a project, case studies can positively impact a design in a multitude of ways.

How do you select a case study?

There are more than a hundred million buildings in the world, and your project could have similarities with thousands of other projects. On the other hand, you could also have a hard time finding buildings that match your specific project requirements.

Focusing your search parameters can help you find helpful references quickly and accurately.

The architectural program includes the spatial organization , user activity, and general functions of a building. Case studies with comparable programs can give you an idea of the spaces and circulation required for a similar project. From this, you can form a design brief catering to the unique requirements of the client or study.

Scale can be a strong common denominator among projects as it can be used to compare buildings of the same size, with a similar number of occupants or volume of visitors. Scale also ensures that the study project has an equivalent impact on the city or its surroundings.

Spaces and designs vary greatly between standalone structures and large-scale complexes, so finding case studies that emulate your project’s scale can give you more relevant and applicable information.

Project type is crucial for comparing spaces one to one. Common types include residential, commercial, office, educational, institutional, or industrial buildings. Each type can also have sub-categories such as single-family homes, mass housing, or urban condominiums.

Case studies with the same project type can help you compare occupant behavior, building management, and specific facilities that relate to your design.

Some case studies can lead you to specific architects with specialty portfolios in certain sectors such as museums, theaters, airports, or hospitals. Their expertise results in a body of work ideal for research and comparison, especially with complex public or transportation buildings.

You may also look into a specific architect if their projects embody the style and design sensibilities that you wish to explore. Many renowned architecture firms have set themselves apart with unique design philosophies and new approaches to planning.

Finding core theories to build on can help steer your project in the right direction.

Project Location

If possible, you’ll want to find case studies in the same region or setting as your project. Geographically, buildings can have significantly different approaches to planning and design based on the environment, demographic, and local culture of the area. There are also many building codes and regulations that may vary across cities and states.

Even when case studies are not from the same locality, it’s important to still have a relevant site context for your project. A tropical beach resort, for example, can take inspiration from tropical beaches across the world.

Likewise, a ski lodge project would require a look into different snowy mountains from different countries.

How are they used?

Whether it’s for academic, professional, or even personal use, case studies can offer plenty of insight for your projects and a look into different approaches and methods you may not have otherwise considered. Here are some of the most common uses for architectural case studies.

Case studies are most commonly used for research, to analyze the past, present, and future of the project typology. Through case studies you can see the evolution of a building type, the different ways problems were solved, and the considerations factored into each design.

In practice, this could be as simple as saying, “Let’s see how they did it.” It’s about learning as much as we can from completed projects and the world around us.

Inspiration

When designing from scratch, it’s common to have a few blank moments here and there. Maybe you’re struggling to develop a unified design , or are simply unsure of how to proceed with a project. Senior architects or academic instructors will often suggest seeking inspiration from existing buildings – those that we can explore and experience.

Throughout history , architecture is shown to have evolved over centuries of development, each era taking inspiration from the last while integrating forms and technologies unique to the time. Case studies are very much a part of this process, giving us a glimpse into different styles, building systems, and forms .

A study project could serve as your entire design peg, or it could add ideas far beyond the facade. The important thing about using a case study for inspiration is beginning with a basis, instead of venturing off into the great unknown. After that, it’s all up to the designers to integrate what they see fit.

As Bruce Lee once said, “absorb what is useful, discard what is not, and add what is uniquely your own.”

Design justification

Case studies help architects make well-informed decisions about planning and design, from the simplest to the most complex ideas. A single finished project is often enough to show proof of concept , and showing completed examples can go a long way in getting stakeholders on board with an idea.

When clients or jurors show skepticism or confusion about an idea, case studies can help you navigate through the hesitation to win approval for your project. Similarly, as a student, case studies can bolster your presentation to help defend your design decisions.

Communication

Unless your clients are architecture enthusiasts themselves, you’re likely going to know a lot more about buildings than them. Because of this, certain ideas aren’t going to resonate with the audience immediately, and you may need additional examples or references to make a convincing presentation.

Case studies help to make connections to existing projects. Beyond the typical sales talk and flowery words, case studies represent actual projects with quantifiable results.

With a study project, for example, you can say “this retail design strategy has been shown to increase rentable space by 15% in these two projects”, or “this facade system used in X project has reduced the need for artificial cooling by 40%, and we think it would be a great fit for what we’re trying to achieve here”.

The Concept Kit

Discover the core components, principles, and processes to form the foundations of award winning work.

Have confidence in your design process.

What to look for during your research.

Each case study should have a specific purpose for your project, be it a useful comparison or a key contribution to your ideas. Sometimes a case study could look drastically different from your project, but it can be used to communicate a wide variety of features and facets that aren’t immediately visible to the eye.

Here are a few things to look out for when doing your research.

If you’re looking to build a museum, the first kinds of buildings to look out for are other museums from around the world. A building with the same typology as yours is almost guaranteed to have similar aspects and approaches. You’ll also be able to see how the building works with its surroundings.

In the case of a museum, you’ll see if the study projects stand out monumentally, or blend in seamlessly, and from there you can decide which is more applicable for your design.

Function is another important aspect that will inform your research.

If for example, you’re comparing two museums, but one is a museum of modern art and the other is a museum of military equipment, they’re going to have vastly different spaces and functions. Similarly, schools can take inspiration from thousands of other schools, but an elementary school’s functions are going to vary greatly from a college campus.

Finding case projects that function more or less the same way as yours will give you more relevant information about the design.

There are also study projects that work well together despite having slightly different functions, such as theaters and concert halls, or bus stations and train stations. These projects, though not exactly the same, still share plenty of similarities in spatial and traffic requirements to be used as effective case studies.

If you’re exploring a certain style, you can find projects with a design close to what you’re trying to achieve.

However the forms don’t necessarily need to look the same.

For example, if you’re planning a museum with a continuous experience from one exhibit to another, you might use the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York as a case study – being one of the earliest and best examples of such style with its round, gently ramped design. But your design doesn’t need to resemble the Frank Lloyd Wright landmark.

The main purpose for finding similar styles is to see how it’s been executed with comparable planning considerations, and to see the effect the style has on a particular project type.

Whether your project is relatively small or large, it’s good to consider how projects of the same scale fare when built. Even if a building has nearly identical features and functions as your project, if it operates on a completely different scale the same principles may be far less effective on your site.

Site conditions can hugely influence the architectural design of a project, especially when working with extreme slopes or remote locations. You’ll often want to study projects that are in a similar part of the world geographically, with comparable site conditions and nearly identical settings.

Check if your site is in a rural or urban area , if it has generally flat or rolling terrain, and if the lot is a particular shape or length.

Environment

Similar to the site itself, environmental considerations will have a large impact on the way case study buildings are designed.

It’s important to know the climate, weather, and scenery of study projects to fully understand the challenges and opportunities that their designers worked with. Buildings in tropical, humid environments use very different materials and elements than those in arid or icy environments.

Circulation

Circulation is a crucial aspect of projects as it directly affects how a building is experienced.

With case studies you’ll need to look out for the flow of people, the ingress and egress areas, and how people and vehicles pass through and around the building. Circulation will determine how the design interacts with the users and the general public.

Accessibility

Though often overlooked, accessibility is becoming increasingly more important, especially for large-scale projects in dense cities. This involves how people move from the rest of the city to the site. It includes traffic management, road networks, public transportation, and universal design for the disabled.

If the target users can’t get to your building, the project can’t be used as intended. When doing case studies, it’s important to consider what measures were taken to ensure the sites were made open and accessible.

Landscape architecture encompasses far more than vegetation and trees. Each project has a unique way of approaching its landscape to address specific goals and tendencies on site.

How does the building integrate itself with the site and surroundings? How are softscapes and hardscapes introduced to create a desirable atmosphere, direct movement, facilitate activity, and promote social interaction?

Government buildings, for example, are often accompanied by wide lawns and open fields. This conveys a sense of openness, transparency, and public presence. It also frames the buildings as significant, monumental structures standing strong in an open area. These are the subtle aspects that can shape your building’s overall perception.

Construction

Construction methods and structural systems are vital for making our buildings stand safe and sound. Some systems are more applicable in tall buildings, while others are more suited for low-rise structures, but it can be interesting to see the different techniques used throughout your case studies.

You can explore systems like cantilevered beams, diagrid steel, thin shell construction, or perhaps something new entirely.

Materiality

If you’re thinking of using certain materials like stone or wood, and you’re curious to see how it was executed elsewhere, case studies can offer some great examples of materiality and the different ways a single material can be used.

The Innovation Center of UC by Alejandro Aravena is a good illustration of how a particular finish – in this case raw concrete – can be used in an unusual way to the benefit of the overall design.

Building services

Building services are one of the many aspects that make architecture a science. Understanding how a building handles things like energy, ventilation, vertical transportation, and water distribution can help you see beneath the surface to get a better idea of how the building works.

Although there are common practices, buildings can deal with services and utilities very differently. A prime example of this is the Centre Pompidou in Paris, which famously turned the building inside out to expose its services on the facade while opening up the interior space for uninterrupted volumes of light and movement.

This style became known as bowellism , and it was largely popularized by the late Richard Rogers .

Some building types are much more demanding when it comes to building services. Airports, for example, have to deal with the flow of luggage, heightened security, and all the boarding and maintenance requirements of the airplanes themselves.

The final thing to analyze while doing your case studies is the building program. This is how the composition of spaces works in relation to the building requirements. It’s helpful to see what makes the building look good, feel good, and function well.

If your study project is accompanied by a program diagram , it can be an excellent way to see how the architects were thinking.

For instance, OMA’s big and bold diagrams show how their designs are organized in a simple and logical manner. It’s become a signature and memorable part of their work, and it communicates the program in a way that everyone can understand.

A building’s arrangement of spaces can often make or break a design. It can be simple and easy to navigate, or complex and intriguing to explore. It can also be confusing or at times, troublesome to get around. Spaces can feel spacious, cozy, or cramped, and each space can evoke a different emotion whether deliberate or unintentional.

The building program is a fundamental aspect that must be considered when conducting case studies.

How do you write and present an architectural case study?

Select the most applicable projects.

There are often hundreds of potential case studies out there, and you can certainly learn from as many projects as you want, but sticking with the most relevant projects can keep your study clear and concise. Depending on the focus of your research, limit your case studies to those most suitable for communicating your ideas.

Stay on topic

It can be tempting to write entire reports about certain buildings – especially if you find them particularly interesting, but it’s important to remember you’re only mentioning these projects to help develop yours. Keep your case study on topic and in a consistent direction to keep the audience engaged.

Use graphics to illustrate key concepts throughout your projects . Even before preparing refined, colorful graphics, you can sketch visual representations as an alternative to notes for your own personal reference.

In addition to making diagrams, you can present multiple examples of similar or dissimilar concepts to compare and contrast the core ideas of different designs. Offering more than one example helps people grasp the ideas that make a building unique.

Strategic Visuals

If the visual speaks for itself, your verbal explanation will only need to describe the essence of it all. When presenting, your speaking time is valuable and it’s best to prepare your slides for maximum engagement so that you don’t lose your audience along the way.

If you carefully select and prepare your visuals, you can optimize your presentation for attention, emotion, and specific responses from the target audience.

Create a narrative

Creating a narrative is a way of tying the whole study together . By using a sequence of visuals and verbal cues, you can take the audience through a journey of the story that you’re trying to tell. Instead of showing each case study differently and independently, you can uniformly relate each project back to the common themes, or back to your project’s design.

This helps to make the relevance of each project crystal clear.

What if your project is unique?

If you’re struggling to find relevant case studies for your project, it could be a good sign that you’ve created a typology that hasn’t been done before – a first of its kind. New building types are important for shaping society and expanding the boundaries of architecture.

Innovative buildings can make people’s lives better.

As far as case studies go, you’ll likely need to gather a handful of reference projects that collectively represent the idea for your project. You can also present a progression, explaining how current and past typologies have evolved into your proposed building type. New-era architecture requires creativity, not only in the ideas but also in the research.

Case studies show us – and our clients – the many great success stories and mistakes of the past, to learn from and improve on as we move into the future. They serve an essential role in guiding our decisions as we design the buildings of tomorrow.

From school , to practice , and everything in between, case studies can be made as the foundation on which we build upon.

For a deeper dive into how case and precedent studies can build upon and influence your conceptual design approaches, we cover this and other key determining factors in our resource The Concept Kit below:

Find confidence in your design approach, and learn the processes that create unique and meaningful conceptual approaches.

Do you find design projects difficult?

...Remove the guesswork, and start designing award winning projects.

FAQ’s about architecture case studies

Where can i find architecture case studies.

There are many resources where you can find architectural case studies. Here are some examples:

- ArchDaily : This is one of the largest online architecture publications worldwide. It provides a vast selection of architectural case studies from around the globe.

- Architectural Review : An international architecture magazine that covers case studies in detail.

- Dezeen : Another online architecture and design magazine where you can find case studies of innovative projects.

- Detail Online : This is a great resource for case studies with an emphasis on construction details.

- Divisare : It offers a comprehensive collection of buildings from across the world and often includes detailed photographs, plans, and explanatory texts.

- The Building Centre : An online platform with case studies on a variety of topics including sustainable design, technology in architecture, and more.

- Harvard Graduate School of Design : Their website provides access to various case studies, including those from students and researchers.

- El Croquis : This is a high-profile architecture and design magazine that offers in-depth case studies of significant projects.

- Casestudy.co.in : It is an Indian platform where you can find some unique case studies of architecture in India.

- Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (CTBUH) : They have an extensive database of case studies on tall buildings worldwide.

In addition to these, architecture books, peer-reviewed journals, and university theses are excellent sources for case studies. If you’re a student, your school library may have resources or databases you can use. Remember to make sure the sources you use are reputable and the information is accurate.

What is the difference between case study and literature study in architecture?

A case study and a literature study in architecture serve different purposes and utilize different methods of inquiry.

- Case Study : A case study in architecture is an in-depth examination of a particular project or building. The goal is to understand its context, concept, design approach, construction techniques, materials used, the functionality of spaces, environmental performance, and other relevant aspects. Architects often use case studies to learn from the successes and failures of other projects. A case study may involve site visits, interviews with the architects or users, analysis of plans and sections, and other hands-on research methods.

- Literature Study : A literature study, also known as a literature review, involves a comprehensive survey and interpretation of existing literature on a specific topic. This could include books, articles, essays , and other published works. The goal is to understand the current state of knowledge and theories about the topic, identify gaps or controversies, and situate one’s own work within the larger discourse. In architecture, a literature study might focus on a particular style, period, architect, theoretical approach, or design issue. It’s more about collating and synthesizing what has already been written or published, rather than conducting new empirical research.

In short, a case study provides an in-depth understanding of a specific instance or example, while a literature study provides a broad understanding of a specific subject as it has been discussed in various texts. Both methods are useful in their own ways, and they often complement each other in architectural research.

Every design project begins with site analysis … start it with confidence for free!.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Latest Articles

19 Awesome Architecture Blogs To Follow

Keeping up to date with what’s occurring is an important part of our professional development…

Restaurant Design Concepts: Architecture guide

…this is far more than mere decoration or architectural indulgence.

Architectural Lighting Concepts – Illuminating spaces

Beyond its fundamental role in visibility, lighting shapes our experiences, influences our emotions, and defines the essence of architectural itself…

Understanding Forced Perspective in Architecture

By tricking the eye, architects have harnessed forced perspective to enhance, distort, or subtly guide the viewer’s experience of a space…

Free Architecture Detail Drawings: The best online construction resources

Accessing high-quality construction and architecture detail drawings can often come with a high cost…

How To Improve Your Architecture Detailing

Mastering the art of architectural detailing is no small feat. It requires a deep understanding of materials, construction methods, and design principles…

As seen on:

Unlock access to all our new and current products for life .

23 Of The Best Architecture Books

Architecture Site Analysis: An introduction

Form Finding in Architecture

Providing a general introduction and overview into the subject, and life as a student and professional.

Study aid for both students and young architects, offering tutorials, tips, guides and resources.

Information and resources addressing the professional architectural environment and industry.

- Concept Design Skills

- Portfolio Creation

- Meet The Team

Where can we send the Checklist?

By entering your email address, you agree to receive emails from archisoup. We’ll respect your privacy, and you can unsubscribe anytime.

- Publications

- News and Events

- Education and Outreach

Software Engineering Institute

Case Studies in Software Architecture

December 13, 2017 • collection.

More and more organizations are realizing the importance of software architecture in their systems' success in areas such as avionics systems, network tactical systems, internet information systems, architecture reconstruction, automotive systems, distributed interactive simulation systems, scenario-based architectural analysis, system acquisition, and wargame simulation systems.

The SEI can provide information and guidance about architecture-related questions and problems. Please contact us . Below are published case studies of real-world applications of architecture-centric engineering. They include case studies using

- architecture evaluation, analysis, and design

- the Architecture Tradeoff Analysis Method (ATAM)

- the Quality Attribute Workshops (QAW)

- architecture reconstruction

Collection Items

A principled way to use frameworks in architecture design, november 30, 2012 • article, by humberto cervantes (universidad autonoma metropolitana–iztapalapa) , perla velasco-elizondo (autonomous university of zacatecas) , rick kazman.

In the past decade, researchers have devised many methods to support and codify architecture design.

Developing Architecture-Centric Engineering Within TSP

April 1, 2013 • brochure, by software engineering institute.

This information sheet describes the Bursatec project, which successfully combined software architecture-centric engineering with the Team Software Process to successfully meet the challenges of architecting a financial trading system.

Relating Business Goals to Architecturally Significant Requirements for Software Systems

April 30, 2010 • technical note, by paul c. clements , len bass.

The purpose of this report is to facilitate better elicitation of high-pedigree quality attribute requirements. Toward this end, we want to be able to elicit business goals reliably and understand …

System Architecture Virtual Integration: An Industrial Case Study

October 31, 2009 • technical report, by peter h. feiler , jörgen hansson (university of skovde) , dionisio de niz , lutz wrage.

This report introduces key concepts of the SAVI paradigm and discusses the series of development scenarios used in a POC demonstration to illustrate the feasibility of improving the quality of …

Evaluating Software Architectures: Methods and Case Studies

October 22, 2001 • book, by paul c. clements , rick kazman , mark h. klein.

This book is a comprehensive guide to software architecture evaluation, describing specific methods that can quickly and inexpensively mitigate enormous risk in software projects.

Scenario-Based Analysis of Software Architecture

November 1, 1996 • white paper, by gregory abowd , len bass , paul c. clements , rick kazman.

This paper presents an experiential case study illustrating the methodological use of scenarios to gain architecture-level understanding and predictive insight into large, real-world systems in various domains.

An Architectural Analysis Case Study: Internet Information Systems

April 1, 1995 • white paper.

This paper presents a method for analyzing systems for nonfunctional qualities from the perspective of their software architecture and applies this method to the field of Internet information systems (IISs).

Using the SEI Architecture Tradeoff Analysis Method to Evaluate WIN-T: A Case Study

August 31, 2005 • technical note, by paul c. clements , john k. bergey , dave mason.

This report describes the application of the SEI ATAM (Architecture Tradeoff Analysis Method) to the U.S. Army's Warfighter Information Network-Tactical (WIN-T) system.

Using the Architecture Tradeoff Analysis Method (ATAM) to Evaluate the Software Architecture for a Product Line of Avionics Systems: A Case Study

June 30, 2003 • technical note, by mario r. barbacci , paul c. clements , anthony j. lattanze , linda m. northrop , william wood.

This 2003 technical note describes an ATAM evaluation of the software architecture for an avionics system developed for the Technology Applications Program Office (TAPO) of the U.S. Army Special Operations …

Using the Architecture Tradeoff Analysis Method to Evaluate a Wargame Simulation System: A Case Study

November 30, 2001 • technical note, by lawrence g. jones , anthony j. lattanze.

This report describes the application of the ATAM (Architecture Tradeoff Analysis Method) to a major wargaming simulation system.

Using the Architecture Tradeoff Analysis Method to Evaluate a Reference Architecture: A Case Study

May 31, 2000 • technical note, by brian p. gallagher.

This report describes the application of the ATAM (Architecture Tradeoff Analysis Method) to evaluate a reference architecture for ground-based command and control systems.

Using Quality Attribute Workshops to Evaluate Architectural Design Approaches in a Major System Acquisition: A Case Study

June 30, 2000 • technical note, by john k. bergey , mario r. barbacci , william wood.

This report describes a series of Quality Attribute Workshops (QAWs) that were conducted on behalf of a government agency during its competitive acquisition of a complex, tactical, integrated command and …

Architecture Reconstruction to Support a Product Line Effort: Case Study

June 30, 2001 • technical note, by liam o'brien.

This report describes the architecture reconstruction process that was followed when the SEI performed architecture reconstructions on three small automotive motor systems.

Architecture Reconstruction Case Study

March 31, 2003 • technical note.

This report outlines an architecture reconstruction carried out at the SEI on a software system called VANISH, which was developed for prototyping visualizations.

Use of Quality Attribute Workshops (QAWs) in Source Selection for a DoD System Acquisition: A Case Study

May 31, 2002 • technical note, by john k. bergey , william wood.

This case study outlines how a DoD organization used architecture analysis and evaluation in a major system acquisition to reduce program risk.

IT architecture: Cutting costs and complexity

Amid the economic downturn, companies are searching for every opportunity to cut costs. IT represents an important part of total spending—5 percent or more in some industries—and its direct contribution to revenues and profits is often difficult to assess. As an unsurprising result, many CEOs and CFOs are eager to squeeze their CIOs’ budgets.

But finding substantial savings isn’t easy. Many CIOs have already spent years reducing costs in operations, procurement, and outside services. Among many other things, they have consolidated data centers and help desks, virtualized servers instead of buying more expensive new ones, rationalized procurement processes, postponed upgrades, and outsourced services to less expensive offshore providers.

Nonetheless, significant additional reductions and efficiencies are possible if companies take a broader look at the way they manage the IT architecture as a whole. The key to these economies is bringing business and IT leaders together in a combined effort to rationalize not only business applications and processes but also the core IT infrastructure and operations. At one large consumer products company, for example, such a joint initiative to combine, consolidate, and rationalize disparate IT systems across business units led to a drastic reduction in the size of the IT staff (by more than 50 percent in the application-management area) and inventories of spare parts, increased leverage in negotiating discounts with suppliers, and the faster completion of new IT initiatives.

The complexities of IT architecture

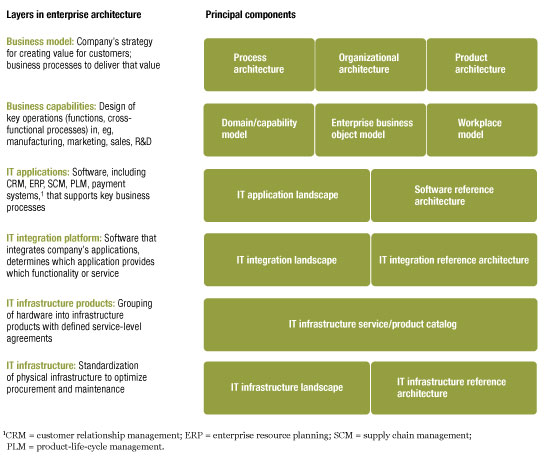

The IT architecture of a company is a formal description of its business operations (processes and functions), the business applications and databases that support them, and the equipment and services that run the applications. A complete IT architecture has six layers (Exhibit 1). In the best cases, companies codify it in a compendium—a blue book—that details the workings of the six layers, as well as the processes, roles, and responsibilities for managing the whole. This document should also provide a road map and rules to guide upgrades and additions.

Mapping IT architecture

Most companies have an IT architecture, but few control it. Instead, it grows organically, and the result is often duplicated systems, proliferating and inconsistent data, and makeshift integration. To make matters still more complicated, at most large companies, even within divisions, many IT initiatives are driven as much by short-term business wants and needs as by any long-term blueprint. That operational reality is especially evident for applications software and the business processes it supports. Such software is usually designed and deployed to suit the needs of one division or business unit, with relatively little regard for the impact on a company’s overall IT architecture.

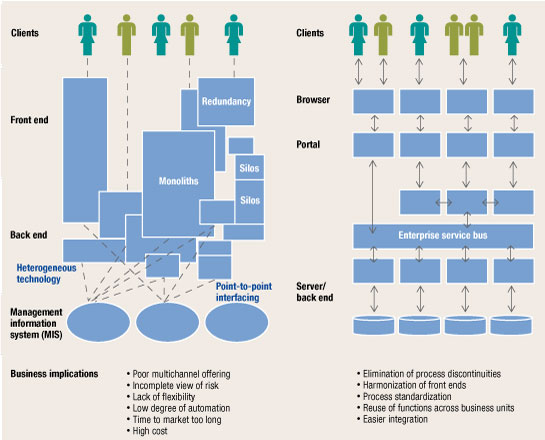

CIOs at the corporate or division level generally do have substantial control over the core IT infrastructure components: servers, storage systems, and the associated infrastructure software. But the business applications, processes, and business model sitting atop the IT infrastructure often reflect the wants of the leaders of business units and functions, who understandably focus more on their own needs than on overall IT efficiency. Across a global company, the result is often an unwieldy, heterogeneous IT environment where incompatible (and often duplicative) hardware, applications, and processes sprout year by year, in every corner of the organization, in response to specific near-term needs.

At a large financial-services company, for example, we recently found seven different payments systems with 20 custom-built applications, which mostly undertook the same functions for purposes such as payroll, taxes, and suppliers. The company had gradually created the systems and applications to meet its major needs, and the outcome was a complex, inefficient, and expensive operation. The IT architecture team had little influence over many ongoing IT projects, so only a small fraction of them were fully in line with corporate standards and guidelines.

Similar inefficiencies characterize the IT operations of companies in every industry. These patchwork systems require substantially more time and money for development, support, and maintenance—at the expense of budgets, new IT capabilities, and business innovation. At large companies, eliminating these duplications and inefficiencies can reduce IT spending by tens or hundreds of millions of dollars while improving the quality of the IT operation and the satisfaction of those who rely on it. The CIO alone, however, cannot reduce these costs; business leaders too must sponsor and participate in the transformation.

Reducing costs and complexity: An integrated architectural approach

Today’s global economic crisis has created a golden opportunity to make order-of-magnitude reductions in IT costs by modifying the corporate IT architecture. What’s needed is a clearly defined IT blueprint with organization-wide guidelines for the most appropriate and efficient systems, applications, and processes. Developing and enforcing these guidelines helps companies to create a consistent and standardized infrastructure and to minimize unnecessary complexity, duplication, and costs (Exhibit 2).

A clean-system landscape

That’s why CEOs must engage a cross-company team of business unit and IT leaders in a no-holds-barred program of architectural review and transformation. We have found that a phased joint approach, focused on a series of cost reduction levers, can reveal and realize substantial savings far beyond the norm for IT-only initiatives. In fact, companies that take this route can also create more flexible and efficient architectures that will help them thrive when the downturn ends.

To create an efficient IT architecture, business leaders and the CIO must jointly evaluate the business requirements and processes that underlie the existing architecture and then explore more efficient alternatives; without a high degree of collaboration, companies probably won’t adhere to even the best architectural designs. In our experience, the right starting point is a high-level business–IT task force that provides cross-organizational governance and accountability. This team’s main responsibilities are to review the existing IT architecture and create a baseline for the new initiative, to define a process ensuring that systems and projects comply with the desired architecture, and to identify short-, mid-, and long-term opportunities for savings and improvements. The team should include all key stakeholder groups, with representatives at a sufficiently high level to make strategic decisions on their behalf.

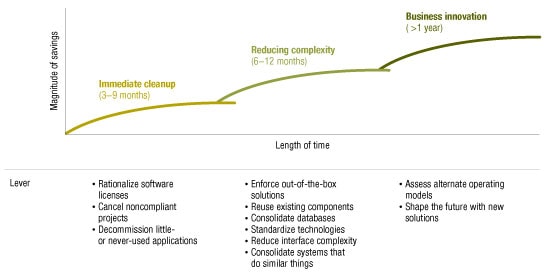

In the interest of minimizing disruption and maximizing benefits, we suggest a three-phase approach, beginning with the easier changes and working gradually toward more substantial ones (Exhibit 3). Staging them carefully makes companies far more likely to build internal collaboration at an appropriate pace, to generate early gains that can finance subsequent initiatives—and to avoid the significant risks of an all-at-once, “big bang” approach: excessive up-front investment, an internal backlash, or system-wide failure, for example.

A three-phased approach

Phase 1: Immediate cleanup

In the first phase, the team’s task is to identify obvious targets and generate quick wins through cost reductions that help build momentum for larger initiatives. In our experience, three levers are important at this point.

Rationalize software licenses. An inventory of licenses should uncover idle, underused, and even incorrect ones. When business managers participate in the review, CIOs can determine how many licenses are truly necessary, retire those that aren’t, and then negotiate deeper discounts by consolidating licenses.

Cancel noncompliant projects. An assessment of the degree to which ongoing projects support both the business and IT strategies can reveal candidates for continuing support, revision, or termination. In ordinary times, this type of review often highlighted projects that business leaders regard as important enough to justify exceptions to architectural rules. The exceptions bar should now be set much higher. Together, the team can segment projects into four groups: (1) projects that have high business value and directly support the IT strategy ought to continue; (2) those that have high business value but don’t comply with the IT strategy should be reshaped; (3) those that comply with the IT strategy but have little business value ought to be delayed; and (4) noncompliant projects with low business value ought to be cancelled.

Decommission little- or never-used applications. Candidates for retirement include business applications that have rarely or never been used over the past year. Different approaches may be required: depending on usage and need, some may be retired immediately, others replaced by newer applications, and still others phased out gradually.

A telecom operator, for example, recently observed that violations of its IT architectural guidelines were rising sharply because managers of business units—who weren’t directly affected by the failure to comply with the guidelines and had little incentive to do so—demanded that IT support new business initiatives quickly. The violations usually made the IT operation more complex and therefore raised its long-term costs.

The company decided to focus on potential IT architecture violations at the start of any IT project or the release of a new application. The new approach—which involves assessing the overall implications of violations, including their possible additional cost—enables the company to support new business requirements quickly but requires any violations they create to be fixed in a later phase. The company can therefore assess the business and IT cost–benefit trade-offs in each case before moving ahead with projects.

Phase 2: Reducing complexity

In the second phase, the team should focus on making the whole IT architecture less complex. This more ambitious undertaking is essential to reverse the ad hoc expansion of customized systems, applications, and processes and to begin enforcing a more complete adherence to the desired architecture. The main objective now is to decide if different pieces of the existing IT setup are truly needed rather than trying to optimize them. Often, the team will find that simpler off-the-shelf systems and the reuse of existing components can support business requirements. Companies can use a number of levers during this phase.

Enforce out-of-the-box solutions. Too many projects adopt customization as a first rather than last option. A company can’t make all its business units embrace standard, completely uncustomized applications immediately, but given limited resources the team should require out-of-the-box solutions in the vast majority of cases, allowing customization only when absolutely necessary to meet legal requirements or provide meaningful competitive advantages. Functions such as finance and accounting, human resources, and purchasing, which typically don’t play a role in direct competition with other companies, are prime candidates for savings in this phase. It’s hard to change organizational mind-sets and behavior, but many IT projects fail because of excessive customization, so its end can make companies substantially more efficient and effective.

Encourage reuse. Too many companies spend precious IT resources reinventing the wheel. A serious review of the existing project portfolio will probably uncover a number of opportunities to reuse existing solutions and build a common repository of services and solutions. The move to a service-oriented architecture (SOA)—which describes a system in terms of the business capabilities it requires and a uniform way of accessing and interacting with them—is an important part of this shift.

Consolidate databases and develop an integrated data model. As companies grow, they add new databases and applications for online sales, customer relationship management, and billing to support business units and functions whose needs actually don’t require different databases. In fact, nonintegrated databases greatly raise costs and result in inefficient processes, duplicative development efforts, longer times to market, business errors, and missed opportunities.

Standardize technologies. In many companies, the great diversity of technologies—including programming languages, operating systems, and integration tools—creates tremendous inefficiencies. A careful review will point out redundant versions, unsupported technologies, and nonstandard tools that should give way to fewer, more standard systems. The cost savings come from simpler and consolidated procurement, as well as lower support and maintenance expenditures.

Reduce interface complexity. An IT staff can spend as much as 30 percent of its development time on applications making all of their interfaces work, largely because customized applications have so many point-to-point interfaces. Standardized interfaces, such as the enterprise service bus (ESB), can greatly ease the burden of system integration and minimize the chore of dealing with local changes. The team should start by identifying and focusing on the key interfaces driving most of the effort.

Consolidate systems that do similar things. Different business units in the same company often have their own versions of essential systems, such as payments and Internet applications. Consolidating these systems at the corporate level can bring substantial savings and make processes simpler and more efficient.

In addressing each opportunity, the CIO and business leaders must look hard at trade-offs between short-term convenience for business units and short- and longer-term costs and complexity for the company as a whole. Facing such realities isn’t easy, but the economic crisis should create a sense of urgency. Some of these cost-cutting opportunities will call for investments, and every one of them will demand a solid business case.

At one retail bank, for example, a comprehensive assessment to reduce architectural complexity identified major cost savings in most areas. A team of business and IT executives helped the company find more than 50 unused applications to decommission, 150 redundant applications to consolidate, 800 point-to-point interfaces to put on an integration platform, and 400 applications to connect with a data integration platform.

Most of these changes required near-term investments—in several cases, such as eliminating or consolidating larger redundant applications, fairly substantial ones. Not all consolidation proposals showed a positive return. What mattered most was the team’s decision to insist that the leaders of projects prove the business case for each of them. In all, the effort is on track to provide a return on investment of more than 50 percent, a reduction in time to market of at least 30 percent, and additional organizational benefits, including better alignment between business and IT.

Phase 3: Business innovation

In times of crisis, companies must consider transforming or even completely reinventing themselves. IT can play a central role in implementing big changes in the way they operate and bring products or services to market. The third and most ambitious phase of architectural transformation is about making these bold changes. As companies look beyond the downturn, they should consider changing their IT in more radical ways that can drive or support strategic innovation and fundamentally new areas for growth. Two levers are relevant.

Assess alternate operating models. Most companies have a global business, but far fewer have developed a truly global IT operating model that supports the corporate strategy. A comprehensive review of the IT value chain should identify the level of sourcing, harmonization, consolidation, governance, and IT enablement necessary for each essential business capability. This review can lead to a new, more effective blueprint and architecture model for IT.

For example, managing and minimizing risk, which is especially important in downturns, depends heavily on getting the right data from the entire business to support timely decision making. Business and IT leaders must work together to design the data-management model that promotes the most effective data-driven decision processes.

Shape the future. Business leaders should work closely with IT to explore investments in a wide range of emerging technologies that support new ways of working, such as using the Internet to cocreate products with customers and suppliers, online collaboration among employees, and data-driven management. New tools and processes can accelerate globalization in product development, find profitable niches in declining markets, and increase productivity.

The triggers for this more ambitious approach to architectural transformation can vary. At one manufacturing company, it was an acquisition. The company had just purchased another international business, vaulting the combined entity into the top five in its industry, with more than 20,000 employees and more than $13 billion in annual revenue. Looking to capitalize on this enhanced position, the company’s leaders realized that they couldn’t succeed with two different operating models relying on archaic information systems.

After defining a new, integrated global operating model for sales and distribution, the supply chain, product-life-cycle management, and postsales service, the company implemented it with a streamlined IT architecture. The impact was substantial. Among many other benefits, the company reduced the time required to quote special-bid prices by 90 percent and to create custom products by 80 percent.

The architectural transformation at a national oil company was sparked by its management’s desire to turn it into one of the world’s top oil and gas businesses. The company’s IT systems couldn’t support such growth. Too many systems were customized to local needs. Too few business processes were in compliance with company standards. Data were inconsistent from one business unit to another, so cross-divisional collaboration was arduous. And IT rarely matched best industry practices.

With a clear mandate from top management, IT and business leaders focused on core business objectives requiring a reformed architecture. Under the new plan, IT would support world-class processes, facilitate corporate-wide decision making by supplying better data, help the company develop better insights about customers, and provide an accurate and up-to-date view of its financial, managerial, and logistics position. The company is developing a unified information system to link all divisions and reviewing with greater discipline all requests for new IT projects. IT is exerting more control over critical functions such as finance, human resources, and sales.

The downturn gives IT and business leaders an important opportunity to collaborate in reducing costs and reshaping the IT architecture for competitive advantage. When companies look solely to the IT function to find savings, the results are often limited. A joint IT–business team can achieve much more.

Bringing IT and business leaders together can also help IT create new ways to make the business grow. Greater flexibility, faster times to market, and more efficient and effective business processes will outlast the downturn. For companies that see the present troubles as a chance not only to control their costs but also to reposition themselves for faster growth once the turnaround begins, restructuring the IT architecture can be among the most valuable moves.

Janaki Akella is a principal in McKinsey’s Silicon Valley office, Helge Buckow is a consultant in the Berlin office, and Stéphane Rey is a principal in the Geneva office.

Explore a career with us

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

IT Strategy Case Study of a Mid-Sized Health Care Organization. Performance and ability to support future growth were being challenged by an increasingly complex healthcare market and ever-tightening budgets. IT needed to chart a new... Visit our IT Cost Optimization Center. Over 100 analysts waiting to take your call right now: 1-519-432-3550 ...

What is an architecture case study. A case study (also known as a precedent study) is a means of finding relevant information about a project by examining another project with similar attributes. Case studies use real-world context to analyze, form, support, and convey different ideas and approaches in design.

Objective: The CLP enterprise architecture team needed to update their architecture to set their organization up for growth. They moved from a project-siloed, application-centric architecture to a future fit architecture built around re-usable business capabilities. At the same time they built an architecture roadmap for a successful smart ...

This detailed case study provides a solution by presenting a comprehensive step-by-step guide on implementing EA using the TOGAF framework. This TOGAF implementation case study initially establishes the necessity of aligning the EA vision and mission with the overarching enterprise goals. Then, it thoroughly explores TOGAF - its definition ...

Evaluating Software Architectures: Methods and Case Studies. October 22, 2001•Book. By Paul C. Clements, Rick Kazman, Mark H. Klein. This book is a comprehensive guide to software architecture evaluation, describing specific methods that can quickly and inexpensively mitigate enormous risk in software projects. Read.

In Deloitte’s 2016 Global CIO Survey, 46 percent of 1,200 IT executives surveyed identified “simplifying IT infrastructure” as a top business priority. Likewise, almost a quarter deemed the performance, reliability, and functionality of their legacy systems “insufficient.” 2.

In Dell’s case the EA team began by establishing an enterprise vision—a blueprint to guide individual projects. This blueprint laid out the structure of the enterprise in terms of its strategy, goals, objectives, operating model, capabilities, business processes, information assets, and governance. Using the blueprint, enterprise architects ...

9 use cases for enterprise architecture 1. Post-merger harmonization . Overview of use case. Corporate and private equity executives foresee an acceleration of merger and acquisition (M&A) activity in 2018, both in the number of deals and the size of the transactions. If Mergers & Acquisitions remain on-trend, close to $5 trillion will be ...

The IT architecture of a company is a formal description of its business operations (processes and functions), the business applications and databases that support them, and the equipment and services that run the applications. A complete IT architecture has six layers (Exhibit 1). In the best cases, companies codify it in a compendium—a blue ...

A case study in architecture is a detailed study of a chosen architectural project, to understand its design, construction, functionality, or contextual importance. The specific architectural qualities examined are to serve as inspiration or as a precedent for your architectural project. Scroll to the bottom to download our Architecture Case ...