Inspiration and Tools for Architects

Thanks for signing up!

Adaptive Reuse Revolution: 7 Commercial Projects Potently Preserving the Past

Buildings aren’t built to be bulldozed. these a+award-winning schemes are a masterclass in injecting new life into languishing landmarks..

The latest edition of “ Architizer: The World’s Best Architecture ” — a stunning, hardbound book celebrating the most inspiring contemporary architecture from around the globe — is now available. Order your copy today .

One of the biggest questions architects and designers face is: what do we do with the buildings we inherit? While demolition yields a blank slate, it erases the historic roots of our built environments and is a wholly unsustainable practice. Extending the lifecycles of existing structures dramatically reduces the energy consumption and carbon emissions generated by constructing anew.

The benefits of adaptive reuse are deeply social as well as environmental. Imbuing the fabric of the past with a purpose for the future is a special kind of alchemy. This collision of architectural timelines can result in astonishing spaces that revive a region’s unique cultural heritage.

These seven winning commercial projects from the 11 th A+Awards exemplify how radical reuse can elevate our skylines. Combining reverence for the past with pioneering designs, there’s much to learn from these extraordinary structures…

By Ehrlich Yanai Rhee Chaney Architects , Costa Mesa, California

Jury winner and popular choice winner, 11 th annual a+awards, commercial renovations & additions.

Contemporary adaptations to the building are thoughtful and restrained. In the atrium at its center, an architectural metal staircase pays homage to the original fabric. Historic elements such as paint chips and conveyor belts have been preserved in situ, yet these emblems of industry are softened by biophilic details. Shrublands pepper the floors of the communal spaces and one of the site’s existing trees now grows through the metalwork of the structure itself.

Ombú

By foster + partners , madrid, spain, jury winner, 11 th annual a+awards, sustainable commercial building.

Designed by architect Luis de Landecho, the exquisite building envelope has been preserved in all its glory and sensitively reworked without compromising the original fabric. In a stroke of architectural genius, a free-standing structure crafted from sustainably sourced timber was inserted beneath the breathtaking pitched steel trusses to accommodate new offices. The platform is recyclable and can be dismantled, so the spatial layout can be effortlessly rewritten in the future. Compared to the lifecycle impact of a new construction, this compassionate design reduces the building’s embodied carbon by 25%, while saving a culturally significant local landmark.

SEE MONSTER

By newsubstance , weston-super-mare, united kingdom, popular choice winner, 11 th annual a+awards, pop-ups & temporary.

While it may be anchored on dry land, the rig’s origins are articulated via a 32-foot-high (10 meter) waterfall, which cascades into a shallow pool at the structure’s base. The platform itself is encircled with kinetic wind sculptures and artworks, as well as wildflowers and trees that balance out the angular, metallic form. This unconventional space inspires unconventional circulation. A playful slide snakes through the middle of the rig, offering an alternate way to navigate the platform.

DB55 Amsterdam

By d/dock , amsterdam, netherlands, jury winner, 11 th annual a+awards, coworking space.

It’s not just the warehouse that’s been given a new lease of life. The interior aesthetic was led by the availability of reclaimed materials. The wood flooring planks comprise domestic roof boarding, and the concrete and glass walls were recycled, while the tiling from the bathrooms was salvaged. 70% of the furniture is second-hand too, including the audiovisual and kitchen equipment.

Kabelovna Studios

By b² architecture , prague, czechia, popular choice winner, 11 th annual a+awards, commercial interiors (<25,000 sq ft.).

The scheme fuses the industrial past with modern functionality. The original restored brickwork envelops the work zones is rich in history and texture, offering an ideal acoustic environment for recording. Modern interventions are sensitively negotiated. Large skylights and sleek glass walls flood the studio with light and allow the bones of the factory to shine.

Casa Pich i Pon. LOOM Plaza Catalunya

By scob architecture & landscape , barcelona, spain, popular choice winner, 11 th annual a+awards, coworking space.

The original heritage skin of the structure has been rediscovered and brought into focus once more. Compelling interior windows offer a portal back in time through the building’s history. Overhead, coffered ceilings and undulating ribbons of brick frame the work zones in an enigmatic canopy. Elsewhere, the prevailing crisp white walls give way to pockets of exposed brickwork. The past is a striking presence in this enchanting reuse project.

By Spark Architects , Rochor, Singapore

Jury winner, 11 th annual a+awards, retail.

Far from business as usual, this retail space is now a pulsing hub that draws in content creators and the digital generation. Threads of vibrant neon lights outline the graphic, cubic structure, creating a glowing beacon amid the melee of gray tower blocks. Street food outlets and social zones occupy the staggered levels, while an outdoor staircase, dubbed the ‘social stair’, carves out a space for live performances and screenings.

Related Content

Brands & firms.

- Ehrlich Yanai Rhee Chaney Architects

- Foster + Partners

- SCOB Architecture & Landscape

- Spark Architects

Future Retro: How Architects Are Crafting Timeless Spaces in the Age of Transience

Future Retro design demonstrates that “timeless charm’ can still exist in a predominately trend-driv en present.

Seamless Integration: The Revitalization of 712 Fifth Avenue Lobby

New York, NY, United States

Subscribe to the Architizer Weekly Newsletter

Case Studies

Before anything, we build trust. Find the who, what, why and how we helped to reduce errors and shorten cycle times.

Open-Web Trusses and creative solutions for a warehouse renovation

This building renovation came with challenges: working through a global pandemic, supply chain restraints, and an expensive original design plan. RedBuilt stepped in with a solution that cut half a million dollars from the budget.

Solving Site Building Height Issues

Through coordination and changes in the radius of the truss, this custom home was able to meet building height requirements for the neighborhood without sacrificing the integrity of the design.

Taylor Middle School Cafeteria

At the beginning of the project, the team conveyed that they wanted more of an open feel since the roof system was going to be exposed. To achieve this look, they came up with a final design that consisted of double trusses at eight-foot on-center.

Kansas City Zoo Cafe: Dressing Up the Tuxedo Grill on a Budget

In October 2013, the Kansas City Zoo opened a new penguin exhibit. Shortly before the exhibit opened, the Zoo also decided to renovate the nearby restaurant—the park’s main eating facility.

Utilizing the Scope of RedBuilt’s Products

RedBuilt has worked on many prefabricated buildings, but this drive-thru restaurant was a great opportunity to showcase our building solutions and unmatched level of service.

Wood trusses, design collaboration support California school build

A new school was built in California’s Imperial Valley. When the project was initially launched and coordinated by Sanders Architecture, RedBuilt’s open web trusses were chosen by their engineering partner, Orie 2 .

Trusses used in design for innovative food bank

Open-web roof trusses and LVL wood were used to satisfy design needs and budgetary constraints in a non-profit food bank and integrated service center. The building’s external, structural transparency was matched by its semi-industrial interior, with a warm, inviting aesthetic that included a mixture of metal and wood materials.

Building an Oregon school with RedBuilt roof and floor trusses

The Gilkey International Middle School project featured a wave-shaped roof that proved to be an interesting challenge for engineers and framers, as well as a concrete-topped floor that required analysis of floor performance over time. Read about how we helped make this a reality.

Prefabricated table forms keep parking garage on time and on budget

“The project schedule and site logistics were a challenge from the start,” says Steve Murray, field operations manager at McClone Construction. “There was not time in the schedule or room on site for us to fabricate the deck tables needed for the parking structure. We needed tables that could be delivered and ready to use immediately, and RedBuilt provided that.”

Log in to my account

- Design Objectives

- Building Types

- Space Types

- Design Disciplines

- Guides & Specifications

- Resource Pages

- Project Management

- Building Commissioning

- Operations & Maintenance

- Building Information Modeling (BIM)

- Unified Facilities Guide Specifications (UFGS)

- Unified Facilities Criteria (UFC)

- VA Master Specifications (PG-18-1)

- Design Manuals (PG-18-10)

- Department of Energy

- General Services Administration

- Department of Homeland Security

- Department of State

- Course Catalog

- Workforce Development

- Case Studies

- Codes & Standards

- Industry Organizations

Case Studies

Below you will find case studies that demonstrate the 'whole building' process in facility design, construction and maintenance. Click on any arrow in a column to arrange the list in ascending or descending order.

Many case studies on the WBDG are past winners Beyond Green™ High-Performance Building and Community Awards sponsored by the National Institute of Building Sciences.

| Beyond Green™ Award Winner | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Building Project: New Construction | 2012 | ||

| Building Project: New Construction | 2016 | ||

| Building Project: New Construction | 2014 | ||

| Building Project: New Construction | 2015 | ||

| Building Project: Existing Addition/Renovation/Retrofit | 2009 | ||

| Building Project: New Construction | 2013 | ||

| Building Project: New Construction | |||

| Initiative | 2018 | ||

| Building Project: New Construction | 2018 | ||

| Building Project: Existing Addition/Renovation/Retrofit | 2013 | ||

| Building Project: New Construction | |||

| Building Project: New Construction | 2012 | ||

| Building Project: Existing Addition/Renovation/Retrofit | 2013 | ||

| Building Project: New Construction | |||

| Building Project: New Construction | 2008 | ||

| Building Project: New Construction | 2014 | ||

| Building Project: Existing Addition/Renovation/Retrofit | |||

| Initiative | 2017 | ||

| Building Project: New Construction | |||

| Building Project: New Construction | 2018 | ||

| Building Project: New Construction | |||

| Building Project: Existing Addition/Renovation/Retrofit | 2016 | ||

| Building Project: Existing Addition/Renovation/Retrofit | 2017 | ||

| Building Project: New Construction | 2018 | ||

| Building Project: New Construction | |||

| Initiative | 2016 | ||

| Building Project: Existing Addition/Renovation/Retrofit | 2015 | ||

| Building Project: New Construction | |||

| Building Project: New Construction |

WBDG Participating Agencies

National Institute of Building Sciences Innovative Solutions for the Built Environment 1090 Vermont Avenue, NW, Suite 700 | Washington, DC 20005-4950 | (202) 289-7800 © 2024 National Institute of Building Sciences. All rights reserved. Disclaimer

- PRESS / AWARDS

- CASE STUDIES

- PLANNING + URBAN DESIGN

- MARKETPLACES

- RETAIL CENTERS

- MIXED USE + HOUSING

- INTERVENTIONS

- ON THE BOARDS

case study tHe ferry building

The ferry building is one of san francisco's most cherished landmark buildings. the renovation was founded on two key ideas - one architectural and one programmatic. architecturally, the project team proposed to return the building's lost soul, the dramatic 660-foot long nave. programmatically, recreated nave would provide a new public use for the building by housing a public market, showcasing the very best of the bay area's food purveyors., site - history, the ferry building was constructed in 1898 by noted architect arthur page brown. the colusa limestone building replaced an earlier wooden terminal located at the same spot, the terminus for ferry service around the bay and the portal to san francisco at the foot of market street. the building was the starting and end point of a journey across america. it was from here that passengers reached the transcontinental railroad in oakland from which the railroads ran a ferry service., at its peak usage in the early decades of the 20th century, the ferry building served more people per day than any building west of the mississippi. but with the construction of the golden gate and the bay bridges, ferry traffic declined and ultimately ceased in the late 1950’s., the ferry building was converted into an office building, with most of its public spaces being cut up and filled in. the bay-facing side of the building, which once looked out onto ferry slips, was closed in and the building began decades of an insular life that removed it from the everyday life of the city. this separation from nearby urban life was dramatically compounded by the construction of the two-story elevated embarcadero freeway, which ran in front of the building, effectively hiding the building from the city., the 1989 loma prieta earthquake structurally weakened the freeway, giving the impetus for its removal. after the removal of the freeway a farmers market sprang up in the space left vacant in front of the building. over the next decade there were many debates over what should occur at the ferry building, culminating in an rfp from the port of san francisco in 1997. the owners of the building, the port of san francisco, recognized the opportunity they had to revitalize the waterfront, and sponsored a competition for the building’s renaissance., bcv architects was the retail architect within a multi-faceted team of developers, designers, preservationists and financial investors led by developer wilson meany sullivan that won the competition with a public/private collaboration on a mixed use concept, with a world class food marketplace and premier office space above. the key element securing this victory was the restoration of the 660 foot nave that had been covered up during various renovations, and the conversion of the former ground floor baggage area into the ferry building marketplace., the vision for the project was to anchor the marketplace with select established local food retail and restaurant operations, such as slanted door, acme bread, cowgirl creamery and scharffenberger chocolate. once those groundbreaking tenants signed on, the team offered smaller tenant spaces to incubate small food producers who had never had a retail outlet before. some of these tenants included long-time bay area wholesale businesses like hog island oysters company and mcevoy olive oil. others were vendors from the already-established ferry plaza farmer’s market, who were ready for the step-up to a daily operation. these vendors included frog hollow farm, prather ranch meat and far west fungi., although bcv had developed a fairly complete design for the ferry building marketplace at the time of the competition, we believed the project deserved a careful study of existing and historic market precedents. the design team embarked on a european trip that would be invaluable for research and background., the team explored the historic markets of london, paris, milan and venice. topics that were studied ranged from the urban - how the buildings and their functions integrate into the life of the city - to the technical, such as shop size and servicing. although no longer a true food market, the physical dimensions and architectural character of london’s covent garden became a touchstone., the relationship of paris’ markets to the surrounding urban fabric, along with the city’s thriving street markets, illustrated the ways in which the ferry building marketplace could function as an iconic and important destination within san francisco. paris institutions hediard and fouchon, along with peck in milan, inspired the team in the ways that food could be merchandised. venice’s rialto fish market taught us important lessons about how to engage the water’s edge., final design, the design for the ferry building marketplace weaves together strategic new construction within the historic fabric of the original building. the designers’ intention was to celebrate historic character of the building while breathing new life into the building. the ground floor nave became defined by tiled archways and steel gates at each vendor stall. the tile relates to the historic brick above, and the gates to the building’s steel trusses., the design purposely narrowed the width of the original nave’s dimension at its ground floor expression, to create an intimate public space. a grand promenade around the perimeter of the second floor office level looks down on the market. three east-west pedestrian connectors cut through the building from the embarcadero to the water, accented with a decorative graphic band above that celebrates bay area towns and cities of the local foodshed. the goal was to create an authentic, working market hall amenity to the class a office space above, that would come to life early each morning, and be washed down at the end of the day., construction, as befits a complicated, historic adaptive reuse project supported on piles over the san francisco bay, the ferry building’s construction yielded many dramatic moments during its deconstruction and rebuilding., the specific vision for the ferry building marketplace was to provide a uniform armature and “vanilla shell” for future demised spaces, including planning for the different tenant types, sizes and adjacencies that would contribute to a vibrant and dynamic market environment. the evolution of the market since its opening in 2004 has seen a dynamic growth of several small tenants to larger spaces, fulfilling the goal of incubating local vendors., the common armature provided a framework within which different tenant expressions could be inserted. this approach supported a variety of producers and encouraged the individual design and brand expressions that contribute to the vitality of an authentic market., bcv was also the architect for many of the ferry building’s original and long-term tenants, and assisted gott’s roadside, acme bread, capay organic, hog island oyster co. and others in creating their ideal shop within the market framework..

back to marketplaces

back to case studies

©2023 :: BCV Architecture + Interiors Powered by TIME Sites

Sign up to receive bcv news and events:.

Pumping Up Sustainability – All-Electric Campus

Key Facts • 12 mixed-use, commercial, and multifamily buildings • 426,000 square feet • $252 million invested • Design begun in 2016, delivered in phases between 2017 and 2024 • Mid-rise, four stories • VRF heat pump systems throughout The founder of Morgan Creek Ventures, Andy Bush, has been implementing heat pumps in new construction […]

Pumping Up Sustainability – 17 Central

Key Facts •Eight-story, mixed-use mid-rise new construction in midtown Sacramento •111 units (one-bedrooms and studios) •Estimated savings of $200,000–$300,000 in labor and materials avoided by not installing individual gas lines to the units •One air-source mini-split heat pump per apartment •Delivered in June 2022 In the design phase of 17 Central in 2020, D&S Development […]

The Materials Movement – PAE Living Building

Designed in accordance with the world’s most rigorous sustainability standards, the PAE Living Building in Portland, Oregon, is the first developer-driven and largest commercial urban Living Building in the world. Constructed with mass timber and nontoxic, bio-based materials, the building sequesters carbon while delivering health and economic benefits to its occupants and owners. The five-story, […]

The Materials Movement – 1550 on the Green

1550 on the Green, a 28-story, 387,000-squarefoot office tower developed by Skanska USA Commercial Development, is on track to become one of the most sustainable buildings in Houston. In addition to targeting WELL and LEED Platinum certifications, the development aims to reduce embodied carbon by 60 percent compared to baseline. Located adjacent to Discovery Green, […]

The Materials Movement – Westlake 66

As the first commercial development to use low-carbon concrete bricks in Hong Kong and mainland China, Westlake 66 is taking an important step forward for sustainability. The 2.1 million-square-foot (194,100 sq m) mixed-use development—including five office towers, a hotel, and a retail podium—is ocated in Hangzhou, China, a rapidly growing tech hub, home to online […]

Net Zero for All – Beach Green Dunes II

Commercial tenant selection is a critical piece of expanding access to high-performing net zero buildings, while also boosting social equity outcomes. L+M Development Partners in New York’s tristate area exemplifies this practice. Committed to “fostering economically diverse communities by developing mixed-income and mixed-use buildings,” L+M has also gone all in on sustainability. Its portfolio includes […]

Health and Social Equity in Real Estate — Schuylkill Yards

Community-Serving Park and Comprehensive Neighborhood Investment at the Schuylkill Yards Development At Schuylkill Yards, Brandywine Realty Trust—a national, fully integrated REIT—went beyond bricks and mortar to respond to the needs of the West Philadelphia community in the long-term master plan for the 14-acre site. The team has prioritized health and social equity with a $16.4 […]

Menomonee Valley Industrial Center (MVIC) and Three Bridges Park

[Quick Facts] [Project Summary] [Introduction] [The Valley] [The Site] [Background] [How it Came Together] [Health and the Environment] [The Developer and the Idea] [Menomonee Valley Industrial Center] [The Stormwater Park] [Job Creation Requirements] [The First Buyer] [Recreation and Entertainment Developments] [Three Bridges Park] [Sales Procedures and Principles] [Design and Development Guidelines] [Development Finance] [Results] [Observations […]

105 Victoria Street

Conceived as a new destination for the West End, 105 Victoria Street is a mixed-use development that will pioneer innovations in sustainability, provide spaces that enhance wellbeing and reinstate a sense of community in London’s Victoria. This development’s world-class office accommodation has been designed to be flexible and long-life to accommodate rapidly evolving ways of […]

Net Zero Deal Profile: HopeWorks Station North

Executive Summary HopeWorks Station North is a net zero–ready development at which affordable housing, workforce development, and job training combine with innovative sustainability elements to improve the life of residents and help the planet. Owned by HopeWorks and Housing Hope, the mixed-use retail and multifamily housing development provides comprehensive housing, social services, and job reentry […]

Sign in with your ULI account to get started

Don’t have an account? Sign up for a ULI guest account.

A checklist for architectural case studies

A case study is a process of researching into a project and documenting through writings, sketches , diagrams, and photos. To understand the various aspects of designing and constructing a building one must consider learning from other people’s mistakes. As Albert Einstein quoted, “Learn from yesterday, live for today, and hope for tomorrow. The important thing is not to stop questioning.”

A case study can be a starting point of any project or it can also serve as a link or reference which can help in explaining the project with ease. It is not necessary that the building we choose for our case study should be the true representation of our project. The main purpose is to research and understand the concepts that an architect has used while designing that project and how it worked, and our aim should be to learn from its perfections as well as from its mistakes too while adding our creativity.

- Primarily, talk to people and never stop questioning, read books, and dedicate your time to researching famous projects . Try to gather information on all famous projects because it is essential for a successful case study and easily available too. Also before starting the case study do a complete literature study on a particular subject, it gives a vague idea about the requirements of the project.

- Study different case studies that other people have done earlier on the projects which you would choose for your own just to get a vague idea about the project, before actually diving into it.

- Do case studies of similar projects with different requirements. For example, while doing a case study of a residential building, you should choose 3 residential buildings, one with the minimum, average, and maximum amenities. It helps in comparing between different design approaches.

- If possible, visit the building and do a live case study, a lot of information can be gathered by looking at the building first hand and you will get a much deeper insight and meaningful understanding of the subject and will also be able to feel the emotion which the building radiates.

- While doing the case study if you come across certain requirements that are missing but went through it while doing the literature study, they should try to implement those requirements in the design.

Certain points should be kept in mind while preparing the questionnaire, they are as follows,

Style of architecture

- The regional context is prevalent in the design or not.

- Special features.

Linkage / Connectivity diagrams

- From all the plans gather the linkage diagram.

Site plan analysis

- Size of the site.

- Site and building ratio.

- The orientation of the building.

- Geology, soil typology, vegetation, hydrography

Construction technologies and materials

- Related to the project.

- Materials easily available in that region and mostly used.

- Technologies used in that region. Search for local technologies that are known among the local laborers.

Environment and micro-climate

- Try to document a building situated in a region that is somewhat similar to the region in which the project will be designed.

- Important climatic factors- sun path, rainfall, and wind direction.

Requirements and used behaviors

- Areas required that will suffice the efficiency of the work to be done in that space.

- Keeping in mind the requirements, age-group, gender, and other factors while designing.

Form and function

- The form is incomplete without function. To define a large space or form it is necessary to follow the function.

- To analyze the reason behind the formation of a certain building and how it merges with the surroundings or why it stands out and does not merge with the surroundings.

- Why the architect of the building adopted either of the philosophies, “form follows function” or “function follows form”.

Circulation- Horizontal and Vertical

- Size and area of corridor and lobbies.

- Placement of staircases, ramps, elevators, etc.

Structure- Column, beam, etc.

- Analyzing the structure detail.

- Types of beams, columns, and trusses used, for example, I- section beam, C- section beam.

Building services or systems

- Analyzing the space requirement of HVAC, fire alarm system, water supply system, etc.

Consideration of Barrier-free environment in design detailing

- Designing keeping the requirements of disabled people, children, pregnant women, etc. in mind.

Access and approach

- Entry and exit locations into the site as well as into the building.

- Several entries and exit points.

Doing a case study and documenting information gives you various ideas and lets you peek into the minds of various architects who used their years of experience and dedicated their time to creating such fine structures. It is also fun as you get to meet different people, do lots of traveling, and have fun.

She is a budding architect hailing from the city of joy, Kolkata. With dreams in her eyes and determination in her will, she is all set to tell stories about buildings, cultures, and people through her point of view. She hopes you all enjoy her writings. Much love.

Architectural drawings :5 Major components and how to ace them

10 Online courses architects can take during Isolation

Related posts.

Building Brands: Nike

Innovative Waste Management Solutions for Construction Sites

Role of Social Welfare in Business

Creative Techniques in Museum Design: Merging Functionality with User Experience

The Intersection of Spirituality and Geometry in Asian Sacred Spaces: A Comparative Study of Mandalas, Vastu Shastra, and Feng Shui

Inclusive Innovation: Design for All

- Architectural Community

- Architectural Facts

- RTF Architectural Reviews

- Architectural styles

- City and Architecture

- Fun & Architecture

- History of Architecture

- Design Studio Portfolios

- Designing for typologies

- RTF Design Inspiration

- Architecture News

- Career Advice

- Case Studies

- Construction & Materials

- Covid and Architecture

- Interior Design

- Know Your Architects

- Landscape Architecture

- Materials & Construction

- Product Design

- RTF Fresh Perspectives

- Sustainable Architecture

- Top Architects

- Travel and Architecture

- Rethinking The Future Awards 2022

- RTF Awards 2021 | Results

- GADA 2021 | Results

- RTF Awards 2020 | Results

- ACD Awards 2020 | Results

- GADA 2019 | Results

- ACD Awards 2018 | Results

- GADA 2018 | Results

- RTF Awards 2017 | Results

- RTF Sustainability Awards 2017 | Results

- RTF Sustainability Awards 2016 | Results

- RTF Sustainability Awards 2015 | Results

- RTF Awards 2014 | Results

- RTF Architectural Visualization Competition 2020 – Results

- Architectural Photography Competition 2020 – Results

- Designer’s Days of Quarantine Contest – Results

- Urban Sketching Competition May 2020 – Results

- RTF Essay Writing Competition April 2020 – Results

- Architectural Photography Competition 2019 – Finalists

- The Ultimate Thesis Guide

- Introduction to Landscape Architecture

- Perfect Guide to Architecting Your Career

- How to Design Architecture Portfolio

- How to Design Streets

- Introduction to Urban Design

- Introduction to Product Design

- Complete Guide to Dissertation Writing

- Introduction to Skyscraper Design

- Educational

- Hospitality

- Institutional

- Office Buildings

- Public Building

- Residential

- Sports & Recreation

- Temporary Structure

- Commercial Interior Design

- Corporate Interior Design

- Healthcare Interior Design

- Hospitality Interior Design

- Residential Interior Design

- Sustainability

- Transportation

- Urban Design

- Host your Course with RTF

- Architectural Writing Training Programme | WFH

- Editorial Internship | In-office

- Graphic Design Internship

- Research Internship | WFH

- Research Internship | New Delhi

- RTF | About RTF

- Submit Your Story

- Our Mission

- What is a Sustainable Built Environment?

- Unlocking the Sustainable Development Goals

- News and Thought Leadership

- Our Annual Reports

- Why become a Green Building Council

- Partner with us

- Work with us

Case Study Library

- Sustainable Building Certifications

- Advancing Net Zero

- Better Places for People

- Circularity Accelerator

- #BuildingLife

- Net Zero Carbon Buildings Commitment

- Regional Advocacy

- Sustainable Finance

- Corporate Advisory Board

- GBC CEO Network

- Global Directory of Green Building Councils

- Asia Pacific

- Middle East & North Africa

- Regional Leadership

Your lawyers since 1722

Home Case Study Library

Welcome to World Green Building Council’s Case Study Library. Here you can find examples of the world’s most cutting edge sustainable buildings. Each case study demonstrates outstanding performance of an operational building that complies with at least one of WorldGBC’s three strategic impact areas: Climate Action ; Health , Equity & Resilience ; and Resources & Circularity .

Explore the map below to find examples from across the globe!

Building type

Sustainability focus, certification/rating.

Kaiser Permanente Santa Rosa Medical Office Building

Urbanización el paraíso, 1 new street square, 117 easy street, 18 king wah road, 218 electric road, 435 indioway, 62 kimpton rd, 84 harrington street, 945 front street, dpr construction office, a zero-water discharge community , adam joseph lewis center for environmental studies, oberlin college, affordable housing project , alpine branch library, arch | nexus sac headquarters, arlington business park, arthaland century pacific tower, ash+ash rainwater capture & reuse, ballard emerald star zero energy home, bcci construction company, bcci south bay, bea 347. oficinas bioconstrucción, bergen inclusion centre, birch house, bishop o’dowd high school environmental science center, booth transport logistics and distribution hub, bürogebäude herdweg 19, burwood brickworks shopping centre, camisas polo salvador, casa laguna, center for intelligent buildings tm, centre block, chai wan campus for the technological and higher education institute of hong kong (thei), city hall freiburg, construction industry council – zero carbon park, cooperative housing , craven gap residence, creating adequate, sustainable, and affordable housing through pension fund capital , cwra cape town, design engineers, disaster resilience retrofits , discovery elementary school, double cove residential development, east liberty presbyterian church, echohaven house, edificio lucia, el camino apartments , elobau logistics centre, energy+home1.0, enhancing lives of refugees , entegrity headquarters, entrepatios las carolinas, filiale kirchheimbolanden, five elements harvest house, floth 69 robertson street, fortitude valley, gibbons street , globicon terminals, green idea house, habitat lab, hadera alfa kindergartens, highland dr, hks chicago living lab, honda smart home us, ideas “z squared” office, indigo hammond + playle architects net pos energy office, integral group, toronto, integral office, oakland, interface global headquarters, irota ecolodge, j.p. morgan chase headquarters (under construction), kāinga ora – homes and communities, king county parks north utility maintenance facility, king street, knauf insulation experience center, lakeline learning center, langes haus, lincoln net positive farmhouse, lombardo welcome center – millersville university, madrona passive house, minneapolis net zero victorian, mohawk college the joyce centre for partnership & innovation, morningside crossing, mvule gardens , nasa sustainability base, ncr corporate headquarters, spring at 8th, nex shopping mall, ohm sweet ohm, packard foundation headquarters, panda passage, petinelli curitiba, phare building, noor solar complex, pitzer college robert redford conservancy, plantronics european office, pyörre house, quay quarter tower, rayside labossière architectes, renovating 32 terraced houses, enhancing satisfaction and comfort , residência loft, rocky road straw bale | community rebuilds, saint-gobain and certainteed north american headquarters, salyani housing project, sede rac engenharia, sfo – 1057 – airfield operations facility (aof), social housing , taft faculty house, te mirumiru early childhood education centre, kawakawa, te papa peninsula, the cork haus, the palestinian museum, the recycled houses, the rmi innovation center, toronto dominion centre, ernst and yonge tower, tour elithis danube, tour elithis dijon, trasciende la parroquia, univercity childcare center, university of california, berkeley haas school of business, ward village, wilde lake middle school, wo lee fabrication & distribution center, wsp brisbane fitout, xiao jing wan university, yitpi yartapuultiku.

Please note that the case studies shown on this page may include older entries. At the time of their submission, these buildings were certified under the relevant schemes and met the submission criteria. However, their certification status may have since expired. We will work towards updating these submissions to provide the most current information. Thank you for your understanding and patience as we strive to maintain the accuracy and relevance of our data.

World Green Building Council Suite 01, Suite 02, Fox Court, 14 Gray’s Inn Road, London, WC1X 8HN

- Privacy Overview

- Strictly Necessary Cookies

- 3rd Party Cookies

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Strictly Necessary Cookie should be enabled at all times so that we can save your preferences for cookie settings.

If you disable this cookie, we will not be able to save your preferences. This means that every time you visit this website you will need to enable or disable cookies again.

This website uses Google Analytics to collect anonymous information such as the number of visitors to the site, and the most popular pages.

Keeping this cookie enabled helps us to improve our website.

Please enable Strictly Necessary Cookies first so that we can save your preferences!

- WHITE PAPERS

- ENEWSLETTER

- CONTINUING ED

- BUILDING SYSTEMS/O&M

- SMART BUILDINGS

- RESILIENCY & SUSTAINABILITY

- SAFETY & SECURITY

- HEALTH & WELLNESS

- CASE STUDIES

- Case Studies

How Mixed-Use Developments Can Ease Urban Density

Despite historic pandemic lows in population growth, the U.S. population is increasing , and urban centers face continued pressure to answer the demand for housing and mixed-use amenities through densification and adaptive reuse. Designers can bring multiple strategies to alleviate these challenges and promote more livable and climate-conscious solutions.

Rising Demand for Mixed-Use Development

The pandemic increased demand for workplace flexibility. By co-locating office, residential and mixed-use functions, designers can provide flexibility for individual working needs while transforming the commute and reducing car travel by facilitating walkability.

The 2023 commercial real estate market foresees a challenging year thanks to global, macroeconomic forces. However, projects that include or are adjacent to residential and other mixed-use functions are in high demand, as many metropolitan areas across the country are experiencing a housing shortage. With workforce housing especially lacking in many cities, the densification of urban areas is growing, and developers are focusing on projects with mixed-use amenities to create livable, 24/7 cities.

Fostering Healthy, Active Lifestyles in Cities Experiencing Rapid Growth

Public health researchers for many years have noted that unhealthy behaviors are the consequences of an unhealthy environment . One of the most critical factors in designing mixed-use developments and offices is providing options. Trends in design over the past decade include creating multiple places to go about the day’s tasks within any environment, whether you’re in the comfort of your home, in a collaborative office space or sitting at a table outdoors.

Providing options for collaboration, privacy, and working engenders a sense of comfort and control. At 301 Hillsborough at Raleigh Crossing, an amenity level shared by multiple tenants is centered on a hospitality-oriented approach to provide people a flexible space to suit their needs. They can catch up with a coworker over cold brew, organize an event with access to the outdoor terrace or simply have a quiet place for taking a break.

Transforming vacant or underutilized sites into public plazas and amenities can further connections to nature and allow city residents to enjoy fresh air, an alternative spot to work or attend community events. As the first phase of the 100-acre Hub RTP development, the two-block development of Horseshoe will transform the live-work-play experience. The innovative mixed-use project will redefine and reinvigorate Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, with on-site restaurants and retail and creative office space.

The “high tech meets nature” theme is reflected in Hub RTP’s location along a network of creeks, trails and naturalized outdoor space on the site’s western edge. Extensive access to the outdoors at the ground floor and via balconies and terraces for office levels distinguishes the Horseshoe development in this market.

Connecting new developments to existing cultural, natural and recreational resources can provide tenants with new opportunities for social and personal development. Walkable neighborhoods with restaurants, retail, workplaces and housing foster an active and balanced lifestyle. By orienting the office building and two retail pavilions in a U configuration, Horseshoe shapes a central landscaped plaza shared by neighboring residents. A small event lawn will host concerts and other performances. Artwork curated into niches in ground-level facades, along organic pathways and sunken terraces further enhance the complex as a public plaza. Open views offer easy navigation and encourage exploration.

Reimagining Parking Structures to Transform Neighborhoods

NCR Global Headquarters transformed an underutilized parking lot into a transparent and transformative work environment with two distinct towers and a multi-layered vertical program. NCR’s visibility from HWY 75/85—traveled by a million people a day—and adjacency to innovative engineering and design programs at Georgia Tech and SCAD provides an urban environment rich with amenities for NCR’s employees.

Typically, city sites near interstate highways are considered development “dead zones.” Instead, this project’s smart building layout, sensitive site design, and visionary developer and design team reimagined a potentially undesirable location as a marquee urban headquarters. The Fortune 500 company’s relocation brought 3,600 jobs to Atlanta.

During NCR’s design, the project team engaged in public review sessions with Midtown Alliance—a non-profit organization dedicated to planning and developing buildings focused on the safety and quality of the physical environment in Midtown Atlanta. Extensive design materials, including physical models and drawings, were presented for comment and recommendation.

This collaboration led to NCR being featured in the Midtown Alliance Owner’s Manual design guidelines as an exemplary urban response. The case study highlighted the project’s creation of walkable blocks and open spaces, greater density, matching setbacks, compatible massing, unobtrusive driveways and attractive screening. Green design features specific to water quality, groundwater and rainwater harvesting systems, and low-flow fixtures contribute to the complex using 35% less water than a typical office building.

Connecting Mixed-Use Developments to Urban Greenways and Greenspaces

With increased awareness of the impacts of climate change, urban greenspace provides opportunities for key climate mitigation strategies including stormwater runoff control, sunshading, reducing the heat island effect, water filtration and air purification.

Human health is improved by access to greenspace and natural areas. Greenspaces in urban settings have been recognized as having great potential for protecting and promoting human health and well-being. The Republic, a 48-story office tower in Austin, Texas, is located on a full block next to Republic Square—a fully renovated urban park and one of Austin’s four original public squares. A 60-foot setback allows for an expansive covered entry courtyard and a public plaza that expands and complements the Republic Square Park as a destination for events, farmers markets and public art installations. Integrated ground-floor retail faces the plaza and is included on all four sides of the tower. The completed project is expected to be the city’s next landmark building, serving as a nexus point with direct connections to a future light rail serving the City of Austin.

Jay Smith serves as Principal and Design Director at Duda|Paine for diverse corporate, commercial and institutional building typologies. His leadership and strength in analysis and conceptual thinking has established award-winning projects at Duda|Paine including The Republic, NCR Global Headquarters, NC Central University Student Center, 301 Hillsborough at Raleigh Crossing and master plans for UNC Asheville and UNC Pembroke.

Sanjeev Patel

Sanjeev Patel, who serves as Principal and Design Director at Duda|Paine, is motivated to make the built environment more meaningful and sustainable to inspire well-being and provide opportunities for building community. His expertise has facilitated a broad range of award-winning projects and diverse building typologies, including Horseshoe at Hub RTP, Stratus Midtown in Atlanta, Walton Family Whole Health & Fitness, Duke Student Wellness Center, and Cox Campus in Atlanta.

Voice your opinion!

To join the conversation, and become an exclusive member of buildings, create an account today, continue reading.

The Case For Indoor Camera Systems at Construction Sites

Ensuring Privacy for Occupants in Smart Building Environments

Sponsored recommendations, latest from case studies.

How the Wright Museum’s Digital Transformation is Leading the Way for Sustainability in Museums

Take a Tour of Philly’s 123 South Broad Street Building (BOMA 2024)

Rooftop Fall Protection: Anchor Certifications, Inspections, and OSHA Requirements

Explore the World’s First Core Living Building at Muhlenberg College

Unlocking the Benefits of Smart Lighting in Commercial Buildings

Commercial Design India

Building for tomorrow – Sustainable strategies and case studies in commercial architecture

India, one of the fastest-growing economies, faces a dual challenge: to accommodate rapid urbanisation and development while ensuring sustainable growth. As cities expand and commercial activities intensify, the need for sustainable commercial architecture becomes paramount. Sustainable commercial architecture not only mitigates environmental impact but also offers economic benefits in the long term. This article explores various sustainable strategies and case studies that highlight successful implementations in India’s commercial architecture.

Sustainable Strategies in Commercial Architecture

1. Energy Efficiency

- Passive Solar Design: Leveraging natural light and heat to reduce dependence on artificial lighting and heating systems. This includes proper building orientation, strategic placement of windows, and the use of thermal mass.

- LED Lighting and HVAC Systems: Incorporating sensor-based LED lighting and VRV or Chiller HVAC systems significantly reduces energy consumption.

2. Water Conservation:

- Rainwater Harvesting: Collecting and storing rainwater for various uses, reducing dependence on municipal water supply.

- Greywater Recycling: Reusing water from sinks, showers, and other sources for non-potable applications like irrigation and flushing toilets.

3. Sustainable Materials:

- Locally Sourced Materials: Reducing the carbon footprint associated with transportation and supporting local economies.

- Recycled and Recyclable Materials: Using materials that have been recycled or can be recycled at the end of their lifecycle.

4. Waste Management:

- Construction Waste Management: Reducing waste during construction through proper planning and using prefabricated components.

- Operational Waste Management: Implementing robust waste segregation and recycling systems within commercial buildings.

5. Green Roofs and Vertical Gardens:

- Green Roofs: Installing vegetation on rooftops to enhance insulation, reduce the urban heat island effect, and manage stormwater runoff.

- Vertical Gardens: Using vertical spaces for growing plants, which improves air quality and aesthetics.

6. Smart Building Technologies:

- Building Management Systems (BMS): Integrating advanced monitoring and control systems to optimize energy use, water use, and indoor climate conditions.

- IoT and AI: Utilising the Internet of Things (IoT) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) to enhance building efficiency and user comfort.

Case Studies of Sustainable Commercial Architecture in India

1. CII-Sohrabji Godrej Green Business Centre, Hyderabad

The Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) – Sohrabji Godrej Green Business Centre in Hyderabad is a pioneering project in green architecture.

– Energy Efficiency: The building orientation and design reduce the need for artificial lighting and cooling. It employs solar photovoltaic panels to generate renewable energy on-site.

– Water Conservation: The centre uses rainwater harvesting and greywater recycling systems. Efficient irrigation systems and drought-resistant landscaping minimize water use.

– Sustainable Materials: Recycled materials were extensively used in the construction. The building also uses low-energy embodied materials.

– Certification: This centre was the first building outside the United States to receive the LEED Platinum rating.

2. ITC Green Centre, Gurgaon

The ITC Green Centre in Gurgaon is another landmark in sustainable commercial architecture.

– Energy Efficiency: The building incorporates high-efficiency HVAC systems, solar shading, and a building management system to monitor and control energy use.

– Water Conservation: ITC Green Centre has an advanced rainwater harvesting system and uses water-efficient fixtures. The on-site wastewater treatment plant ensures that recycled water is used for landscaping and flushing.

– Waste Management: The building has a comprehensive waste management plan, including recycling and composting.

– Green Spaces: The design includes ample green spaces, both on the ground and as green roofs, which contribute to improved air quality and thermal comfort.

3. KLJ House, Central Delhi

KLJ House is a sustainable Grade A office building in Central Delhi

– Energy Efficiency: KLJ House is designed to maximize natural light, reducing the need for artificial lighting. The building uses high-performance double glazing and naturally ventilated stairwells to minimize heat gain.

– Water Conservation: The building implements extensive rainwater harvesting systems and a water-cooled chiller HVAC plant. Recycled water is used for landscaping.

– Sustainable Materials: The building construction utilized locally sourced materials and low-VOC (Volatile Organic Compounds) paints and adhesives.

As India urbanizes rapidly, the pressure on natural resources and infrastructure intensifies. Sustainable commercial architecture offers a viable solution to balance development with environmental stewardship. The benefits of sustainable buildings are manifold:

Reduced Environmental Impact: Sustainable buildings use fewer resources, generate less waste, and emit fewer greenhouse gases.

Economic Benefits: Energy-efficient buildings reduce operational costs, providing long-term financial savings.

Enhanced Occupant Comfort and Health: Improved indoor air quality, natural lighting, and thermal comfort contribute to the well-being and productivity of occupants.

Regulatory Compliance and Market Differentiation: Adhering to green building standards and certifications can enhance a company’s reputation and meet regulatory requirements.

India’s commercial architecture landscape is evolving, with sustainability at its core. Through innovative strategies and successful case studies, it is evident that sustainable architecture is not only achievable but also beneficial for businesses and the environment. As urbanization relentlessly continues, adopting sustainable practices in commercial architecture will be crucial for building a resilient and prosperous future for India’s cities.

- Key Activities

- Peer Review

- Building Controls

- Building Electric Appliances, Devices, and Systems

- Building Energy Modeling

- Building Equipment

- Solid-State Lighting

- Opaque Envelope

- Thermal Energy Storage

- Tools & Resources

- Publications

- Building Science Education

- Software Providers

- Research & Background

- Home Performance with ENERGY STAR

- Home Improvement Catalyst

- Zero Energy Design Designation

- Race to Zero Student Design Competition

- STEP Campaign

- SWIP Campaign

- ZERH Program Requirements

- ZERH Partner Central

- 45L Tax Credits and ZERH

- DOE Tour of Zero

- ZERH Partner Locator

- ZERH Program Resources

- Housing Innovation Awards

- Standard Energy Efficiency Data Platform

- Building Performance Database

- Energy Asset Score

- Technology Performance Exchange

- BuildingSync

- Building Energy Data Exchange Specification

- Advanced Energy Design Guides

- Advanced Energy Retrofit Guides

- Building Energy Modeling Guides

- Workforce Development & Training

- About Zero Energy Buildings

- Zero Energy Design Tools

- Zero Energy Technologies & Approaches

- Zero Energy Project Types

- Zero Energy Project Profiles

- Zero Energy Programs

- History & Impacts

- Statutory Authorities & Rules

- Regulatory Processes

- Plans & Schedules

- Reports & Publications

- Standards & Test Procedures

- Standardized Templates for Reporting Test Results

- Test Procedure Waivers

- How to Participate or Comment

- Public Meetings & Comment Deadlines

- Appliance Standards & Rulemaking Federal Advisory Committee

- Further Guidance

- Testing & Verification

- Building Energy Codes

- Success Stories

- Funding Opportunities

- Events & Webinars

- Advanced Building Construction Initiative

Systems-based retrofit strategies have significant energy-savings potential, providing anywhere from 49% to 82% in additional energy savings compared to component-only upgrades. 1,2 Until now, few studies have explored how often American businesses include systems-based retrofits in their energy and sustainability investments. After examining a dataset of 12,000 retrofit projects, the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE’s) Building Technologies Office (BTO) and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) found that while system retrofits represent less than 20% of all retrofit projects, they are twice as common in projects with higher overall energy savings.

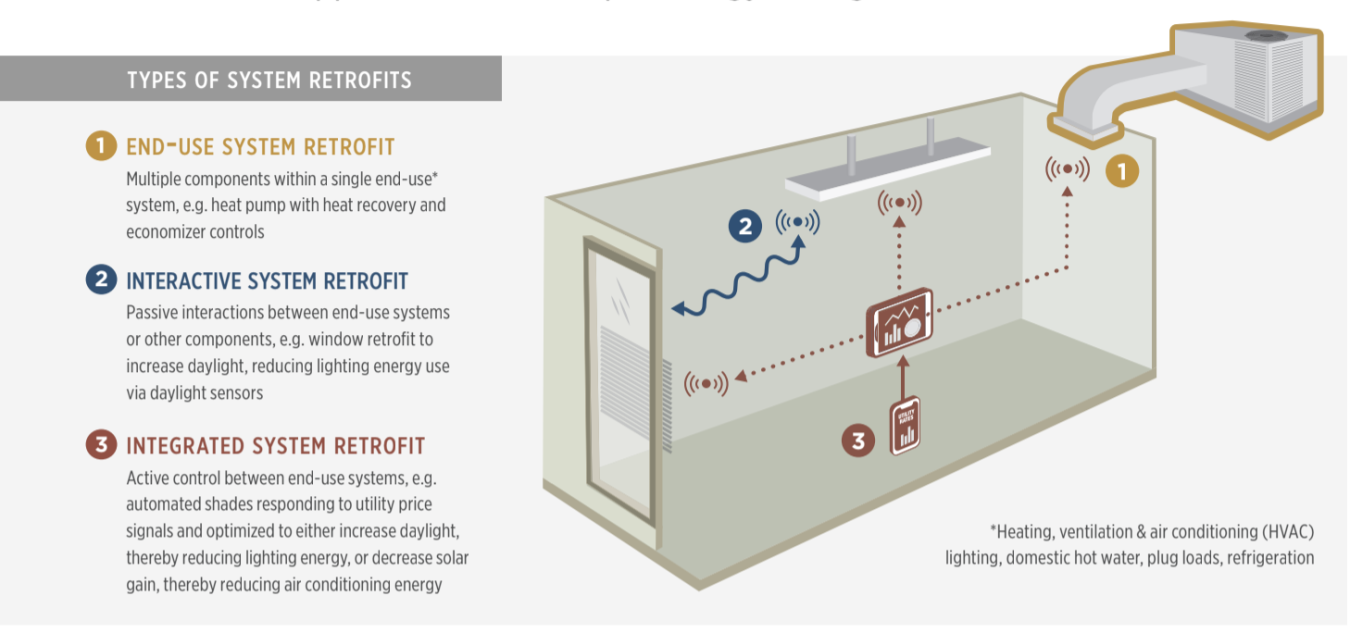

The study, “ Systems Retrofit Trends in Commercial Buildings: Opening Up Opportunities for Deeper Savings ,” provides a framework for categorizing systems approaches. It defines a systems-based retrofit as going beyond a single component (such as a lamp or chiller) by incorporating additional elements or controls within an end-use system or using passive or active controls for interaction with other building components or end-use systems.

Systems-based retrofit strategies.

LBNL’s researchers evaluated the dataset―which contained information from utility custom retrofit programs, federal government retrofit programs, and energy service company retrofits―to identify the following:

- How often system retrofits are occurring

- The most prevalent technologies used in these retrofits

- Whether system retrofits save more energy than component retrofits

- How these different programs are successful in deploying system retrofits

This research, led by FLEXLAB ® Executive Director Cynthia Regnier, shows that system retrofits in commercial buildings are critical to achieving aggressive energy-reduction goals. Forty percent of projects with high energy savings were found to include system retrofits, while only 16% of projects with low energy savings included systems retrofits. Additionally, there were notable differences in the success of each program type in deploying system retrofits. Utilities lagged behind other programs, relying heavily on lighting-system retrofits. Mechanisms such as energy savings performance contracts (ESPCs), on the other hand, achieved deeper levels of energy savings and made use of a wider range of strategies, including HVAC system retrofits.

The study includes interviews with a range of stakeholders, which shed light on barriers to further uptake and increased deployment. The interviews show that system retrofits could be expanded through increased awareness of their energy-savings potential, technology and process improvements to reduce complexity of design, installation and operation, and, in some cases, removal of policy barriers that require individual measures of cost-effectiveness, which can be incongruent to a system that is cost-effective as a whole.

This work complements ongoing research on the benefits associated with commercial building technologies. To learn more about BTO’s efforts to improve energy efficiency in the country’s 5.6 million commercial buildings, visit www.energy.gov/eere/buildings/commercial-buildings-integration .

1 Regnier, C., K. Sun, T. Hong, and M.A. Piette. “Quantifying the benefits of a building retrofit using an integrated system approach: A case study.” Energy and Buildings 159 (2018).

2 Regnier, C., P. Mathew, A. Robinson, P. Schwartz, J. Shackelford, and T. Walter. 2018. Energy Savings and Costs of Systems-Based Building Retrofits: A Study of Three Integrated Lighting Systems in Comparison with a Component Based Retrofit. Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

Add a bookmark to get started

ESG and Commercial Real Estate Case Study

New and complex laws intended to increase the sustainability, climate resilience, and efficiency of commercial buildings are rapidly emerging across the US and worldwide. While some laws have required the disclosure of energy and water use in buildings for years, numerous state and local jurisdictions are now instituting "building performance" laws that require building energy use reductions and carbon emissions caps, together with penalties for failing to meet these new standards. DLA Piper can help commercial real estate owners and property managers understand and take proactive steps to meet these requirements in ways that support sustainability initiatives while avoiding unexpected financial burdens.

Navigating an evolving regulatory landscape

Building performance laws typically hold building owners responsible for legal compliance. But in commercial real estate, the drivers of actual energy and water use in buildings are generally its tenants. This means that buildings not only have to be built to specific requirements, but landlords and tenants must cooperate to ensure that building use and operation meet stated requirements. Strong working relationships and enforceable agreements with tenants and property managers are critical to avoiding penalties and other unanticipated costs.

We are at the forefront of helping clients proactively understand the requirements coming into effect, plan for them, anticipate new requirements, and negotiate "green" leases that help landlords and tenants strategically align priorities and behaviors, and avoid unwanted liabilities. We are also helping our clients understand how these laws could apply to their buildings under various future regulatory scenarios if their buildings rely on utility services from the grid (which may be powered by fossil fuels).

Practice example: Building decarbonization and clean energy law tracking

Our client, a leading international real estate owner focused on the life science and technology sectors, is subject to numerous ESG laws that are difficult to find, hard to understand, and frequently changing. Our client needed help to identify, summarize, and then track proactively the rapidly changing legal landscape of international, state, county, and city laws, regulations, and building codes that are driving decarbonization of buildings and forcing utilities to replace fossil-fuel-powered electricity with clean energy sources. This client sought a trusted partner to track and summarize laws that fall under the following interrelated, cross-disciplinary legal topics:

- "Benchmarking and Disclosure Laws": Laws that require building owners to calculate and report building-specific energy usage, energy efficiency measures, water conservation measures, and/or projected greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from energy usage at a building (or buildings) on a regular reporting schedule.

- "Building Performance/GHG Emissions Cap Laws": Building performance laws or building codes that either (i) prohibit buildings from producing/emitting GHGs beyond certain established caps (which caps may be progressively reduced to reach "net zero" over time), or (ii) require buildings to be built to higher energy efficiency or green building standards.

- "Bans on Fossil Fuel Use or Fossil-Fuel-Powered Utility Connections in Buildings": Laws or building codes that prohibit the use of natural gas (or other fossil fuels) as a direct source of energy for specified buildings; that prohibit building connections to fossil-fuel-powered utility/building infrastructure; and/or that prohibit installation of equipment that use natural gas.

- "Electrical Grid - Clean Energy - Renewable Portfolio Standards (RPS) and Clean Energy Sourcing Requirements": Clean and renewable energy sourcing requirements for public utilities in target cities, including state renewable portfolio standards and regional compacts, that could affect carbon emissions caused by using energy from the grid.

We assembled a cross-disciplinary team from our deep bench of environmental/ESG and real estate lawyers who have the relevant expertise and skills to track the complex web of decarbonization laws in 22 cities across the United States and United Kingdom. We identified and summarized current laws at the national, state, county, and city levels, and we continue to track changes to these laws and provide updated summaries and regular quarterly reports to capture evolving trends in real time.

Our client views compliance with ESG-related requirements as critical to its continued success in the marketplace and to its ability to attract a wide range of investors far into the future. By helping our client understand the range of ESG-related requirements affecting its portfolio, assist with current compliance, plan for future compliance, and avoid fines and penalties, we are helping our client achieve these important business objectives.

Comprehensive coverage

The above example is significant, not only because we are tracking emerging laws at the cutting edge of sustainable real estate as they unfold, but because we are covering laws at every scale, down to the most granular level, from national and regional laws to local codes. This scope of coverage is particularly important as more government agencies try to regulate sustainability by increasing climate disclosures while forcing carbon emissions reductions, both in the United States and the European Union. Companies will need to align company-wide reporting with their business operations across numerous jurisdictions, which inevitably will include their real estate assets. Because of our large US and global platform, we are able to offer clients a one-stop shop to understand and track these requirements and translate them in business-friendly ways.

Getting started

The intersection of sustainability and real estate presents numerous challenges that should be met with a thoughtful and deliberate strategy. Our ESG and real estate lawyers are ahead of the curve in helping clients understand the issues and develop practical, real-world solutions to mitigate these multi-dimensional challenges.

We look forward to working with you.

Related capabilities

- Capabilities

- Find an office

DLA Piper is a global law firm operating through various separate and distinct legal entities. For further information about these entities and DLA Piper's structure, please refer to the Legal Notices page of this website. All rights reserved. Attorney advertising.

© 2024 DLA Piper

Unsolicited e-mails and information sent to DLA Piper or the independent DLA Piper Relationship firms will not be considered confidential, may be disclosed to others, may not receive a response, and do not create a lawyer-client relationship with DLA Piper or any of the DLA Piper Relationship firms. Please do not include any confidential information in this message. Also, please note that our lawyers do not seek to practice law in any jurisdiction in which they are not properly permitted to do so.

Homes and commercial buildings need substantial investments to become more resilient and sustainable. Who pays for these investments has important equity implications.

Subscribe to infrastructure at metro, jenny schuetz and jenny schuetz senior fellow - brookings metro eve devens eve devens research assistant - brookings metro.

September 17, 2024

- 32 min read

Executive summary

Real estate markets have complex interactions with climate change. Homes, offices, stores, and other buildings are major contributors to greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs), the cause of global warming. At the same time, buildings—and the people inside them—are highly vulnerable to physical damage from floods , wildfire s, and high winds . Buildings in high-risk locations also face financial harms , such as rising insurance premiums and a potential decline in property values . Therefore, a green transition will require investments aimed at improving buildings’ sustainability (reducing GHG emissions) and resilience (making buildings safer). In the U.S., most of these investments will require retrofits of existing structures; new constructions adhere to more recent building codes, but they constitute a very small share of the overall building stock.

This leads to an obvious question: Who will pay for these climate investments? Roughly two-thirds of U.S. households are homeowners; how many of them have the financial resources and technical expertise to undertake appropriate energy-efficiency and resilience upgrades? Many low-income households rent their homes, so they are dependent on their landlords’ actions. Owners of commercial properties—including apartments, offices, stores, factories, and warehouses—range from small mom-and-pop landlords to real estate investment trusts (REITs) to sovereign wealth funds. Different types of property owners have widely varying access to financing sources and costs of capital—not to mention the organizational capacity to research the right type of climate investments, obtain equipment, and oversee contractors.

This report provides an overview of the challenges facing private-sector real estate markets as they adjust to climate change, focusing particularly on sources of funding that can support green investments in buildings. The analysis synthesizes insights from academic research, drawing particularly on recent empirical work in urban and real estate economics. The report does not address climate investments in real estate owned by government agencies or large institutional nonprofit organizations, such as universities and hospitals.

Key findings from the report include:

- The breadth and complexity of the industry means that climate investments are likely to emerge unevenly, particularly under the patchwork of current policies at the local, state, and federal levels. The four primary challenges to privately led climate investment are: highly decentralized ownership and decisionmaking, property owners and managers facing a lack of relevant information, fragmented funding sources, and inconsistent policies from public agencies.

- The prospects for climate investments in both owner-occupied homes and commercial properties depend heavily on the resources of property owners—raising serious concerns about equity. Affluent homeowners can upgrade their properties by tapping into their savings or borrowing against accumulated home equity—options that would be difficult for homeowners with tight budget constraints. Rental housing raises even greater concerns because renters have lower average incomes than homeowners; moreover, low- and moderate-income renters tend to live in older, poorer-quality buildings that are less likely to meet stricter building codes or energy-performance standards. On the resilience side, low-income households and communities (as well as commercial properties) often face greater physical risks yet have fewer financial resources to protect themselves.

Climate stresses on homes and commercial real estate will only increase in the coming decades. Better communication between public agencies and private real estate actors about climate investments, as well as deliberate attention to equity concerns, will be necessary to increase the sustainability and resilience of buildings and communities.

Introduction

The economic, social, and human costs of climate change are becoming increasingly salient across the U.S. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) to slow the pace of climate change will require behavioral changes from households, businesses, civic organizations, and public agencies. Additionally, communities are struggling to protect themselves from increasingly intense—and sometimes unexpected—climate events ranging from wildfires and intense storms to extreme heat and drought.

While all sectors of the economy will need to engage in adaptation and mitigation efforts, the real estate sector faces particular stresses. Homes, offices, stores, and warehouses are substantial contributors to GHG emissions, and these buildings are vulnerable to damage from climate events. Most real estate in the U.S. is owned by private individuals or companies, who bear the primary responsibility for maintaining and upgrading their properties. How quickly a green transition in the real estate sector happens will depend on the knowledge, resources, and decisions of millions of individual property owners.

The goal of this report is to provide an overview of the challenges facing private-sector real estate markets as they adjust to climate change, focusing particularly on sources of funding that can support green investments in buildings. By synthesizing insights from academic research, we identify four primary challenges to more widespread adoption of climate investments: highly decentralized ownership and decisionmaking, property owners and managers facing a lack of relevant information, fragmented funding sources, and inconsistent policies from public agencies. Further, climate investments depend heavily on the knowledge and financial resources of property owners, raising serious concerns about equity issues in undertaking these investments.

Buildings contribute to environmental damage and are vulnerable to climate events

Buildings are a substantial contributor to GHG emissions and are highly vulnerable to physical and financial risk from climate events; therefore, a green transition will require investments aimed at both mitigation and adaptation. Furthermore, the real estate sector is exposed to considerable transition risk, as local, state, and federal government officials adopt new policies and private capital markets reconsider where to channel resources.

What kinds of investments could make buildings more sustainable and resilient?

The building sector contributes to GHG emissions directly through energy consumption and indirectly based on where homes, offices, and stores are built. Buildings consume energy for heating, cooling, hot water, and the operating of appliances. Residential and commercial buildings together account for roughly 30% of GHG emissions (including indirect emissions from electricity generation). Additionally, where buildings are located relative to economic activity , infrastructure, and amenities impacts GHG emissions from the transportation sector. Low-density residential and commercial development creates greater distances between homes, jobs, and retail and services locations, and low-density development is difficult to serve efficiently through public transportation. Better land use planning could allow people to commute to work and run errands by using public transit, walking, or cycling. The production of building materials —especially concrete and steel—also causes GHG emissions (as discussed in a related report ).

On the mitigation side, a variety of physical investments are needed to decarbonize buildings, as summarized in Table 1 below. Replacing heating systems that rely on natural gas or home heating oil with electric heat pumps, which both heat and cool buildings, is a major focus of the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act . Replacing old, leaky windows and doors with new, double-paned, tight-fitting windows and doors—and adding insulation and sealing air leaks—can reduce energy usage from heating and cooling systems. New appliances, such as hot water heaters, dishwashers, and clothes dryers, are more energy efficient than appliances from several decades ago. About half of U.S. homes are over 40 years old ; retrofitting older homes and commercial buildings is one of the major challenges for decarbonizing buildings.

As for adaptation investments, buildings across the U.S. face high physical risk from several types of climate events, including flood s, wildfire s, and high winds . Extreme temperatures can also damage buildings, particularly when they occur in regions of the country that are unaccustomed to extreme heat or cold. For example, below-freezing temperatures in the Deep South are more likely to lead to water pipes bursting.

A range of adaptation strategies could help protect buildings and their occupants from climate risks. Elevating structures in flood-prone areas, using fire-resistant exterior building materials, bolting roofs more securely against high winds, and coating external surfaces with heat-reflective ultrawhite paint are all ways that individual property owners can reduce the expected harms of climate events. Some of the most effective adaptation strategies require community-level investments , such as upgrading stormwater management systems and installing rain gardens to handle higher volumes of rainfall or increasing the tree canopy to cool entire neighborhoods.

The cost of mitigation and adaptation investments can vary widely, making it difficult to estimate the scale of funding needed. What types of retrofitting investments are needed depends on the age, structure type, size, and quality of existing buildings. In addition, construction sector wages and benefits vary widely across regions of the country—as does even the availability of contractors with relevant expertise. Community-based investments require implementation from local or regional governments and potentially support from civic organizations. As later sections will discuss, varying expertise and access to financing by property owners is one of the major hurdles to an equitable transition of the buildings sector.

Real estate values and operating costs are likely to change in response to climate events and policy changes

Physical climate risk creates direct financial risk to property owners through several channels. A growing body of research shows that owner-occupied homes that face higher risks of flooding and wildfire s sell for lower prices than similar homes in the same city, and research also indicates that sales volumes for high-risk homes also decline after disasters. These papers find that impacts mostly follow in the short term after high-visibility events, but they often disappear within 3–5 years. Commercial real estate (CRE) prices also decline after flooding from intense storms . There is less consensus on whether climate risks impact rents for apartments; fewer studies have looked at residential rental markets, partly because of the difficulty in observing rent data for small geographic areas. Another notable gap in the research is the impact on real estate markets of chronic stresses, such as extreme heat and drought.

Both acute and chronic climate stresses can also increase operating expenses for both owner-occupied and investor-owned real estate. Most notably, the past several years have seen rising insurance premiums and declining availability of policies in states such as California , Florida , and Colorado . Both households and businesses often experience disruptions in their income following natural disasters, which can increase the probability of delayed or missed rental and mortgage payments , especially among low- and moderate-income households. Climate change is also likely to impact expenditures on property maintenance, utilities, local property taxes, and user fees; further research is needed on these topics.