clock This article was published more than 1 year ago

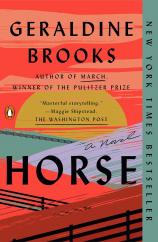

The historical novel ‘Horse’ sheds light on real-life racism

Pulitzer winner geraldine brooks’s latest book is a sweeping tale that uses the true story of a famous 19th-century racehorse to explore the roots and legacy of enslavement.

In 2019, a PhD student in art history rescues an oil painting of a racehorse from a pile of discarded stuff on a Georgetown sidewalk, and a zoologist finds a skeleton marked “Horse” in a Smithsonian attic. In 1850, an enslaved boy is present at the birth of a foal. These are the ingredients with which Geraldine Brooks begins her new novel, “Horse,” and, goodness, they are just as beguiling as her fluid, masterful storytelling.

From the beginning, the weave of the narrative is clear: It’s no surprise that the horse in the painting is the same animal whose bones are collecting dust in the Smithsonian and the same again as the newborn foal who will find a devoted, lifelong companion in the boy, Jarret. The horse’s name is Lexington, and he was a real-life racehorse who won six of his seven starts and became a legendary thoroughbred sire whose offspring dominated American racing in the late 19th century. Brooks includes other figures from history: Lexington’s various owners; Thomas J. Scott, a Pennsylvania-born animal painter who served in the Union Army during the Civil War; and the modernist art dealer Martha Jackson. But Brooks’s central characters — Jarret; the art historian Theo; and the zoologist Jess — are invented.

Geraldine Brooks reimagines King David’s life in ‘The Secret Chord’

Jarret is the child of Harry Lewis, a horse trainer who was able to buy his own freedom in antebellum Kentucky. Harry’s employer, Dr. Elisha Warfield, offers to give the colt Lexington to Harry in lieu of a year’s wages so that Harry, if he makes the horse a success, might earn enough to purchase his son. This bargain proves too good to be true. Once Lexington wins his first race, Harry’s ownership gives covetous White horsemen the necessary leverage to take the animal from him. It turns out there is a law forbidding Black people from running horses, and so Dr. Warfield is blackmailed into selling both Lexington and Jarret. The young man and the horse are sent south, eventually to the massive racing operation of Richard Ten Broeck in Louisiana. Of course, the abhorrent and absurd truth is that both Lexington and Jarret are considered livestock, resources to be exploited until they die. Ten Broeck recognizes the value of Jarret’s skill with horses and deep rapport with Lexington and, in what could be mistaken for generosity but is actually just canny exploitation, elevates him to the status of deputy trainer, a promotion that gives Jarret responsibility without true authority.

A century and a half later, Theo and Jess are brought together by Lexington’s remnants: his portrait, his bones. Theo, who is Black, is the child of diplomats, a Nigerian mother and an American father. He grew up in British boarding schools and was a polo star at Oxford before the indignities of racism — from which privilege could not insulate him — drove him from the sport. His interest in the horse portrait is casual at first, then sharpens as he homes in on the presence of Black men in similar works from the era — grooms and trainers — likely to have been enslaved. Jess is White, Australian and an odd duck, fascinated since childhood with the bones of living things. The two begin a tentative relationship, their mutual attraction existing uneasily alongside Jess’s tendency toward oblivious microaggression and Theo’s doubts that she is capable of fully understanding his experience as a Black man.

The 23 most unforgettable last sentences in fiction

Jarret’s story is one of individualism. His dogged betterment of himself and his tenacious devotion to Lexington serve as a private rebellion against the erasure that is slavery. Ultimately the war determines his fate, but unpredictably so. Theo and Jess are also at the mercy of their time, but progress is a complicated proposition. The resolution of their story is saturated with the same rot of injustice that was introduced to this country with slavery and has flourished ever since. In “Horse,” Brooks, who is a meticulous researcher and whose previous novels, including “ People of the Book ” “ Caleb’s Crossing ” and the Pulitzer Prize-winning “ March ,” have all been concerned with the past, writes about our present in such a way that the tangled roots of history, just beneath the story, are both subtle and undeniable.

The feeling that pervades is that the more things change, the more they stay the same. Horses were cruelly used and discarded by the antebellum horse-racing industry; the same is true of modern racing. Enslaved men were regarded as inherently dangerous and were murdered without consequence according to White whims; police officers kill Black men with impunity still today. The artist Thomas J. Scott, initially sympathetic toward Confederate prisoners, eventually gives up talking to them because they were “lost to a narrative untethered to anything he recognized as true. Their mad conception of Mr. Lincoln as some kind of cloven-hoofed devil’s scion, their complete disregard — denial — of the humanity of the enslaved, their fabulous notions of what evils the Federal government intended for them should their cause fail — all of it was ingrained so deep, beyond the reach of reasonable dialogue or evidence.” If that doesn’t sound familiar, you haven’t been on the internet lately.

Maggie Shipstead’s ‘Great Circle’ is a soaring work of historical fiction and a perfect summer novel

I raced through the novel’s first half and then slowed and slowed as I went on, so worried for what might happen to Jarret and Theo and to Lexington that I could hardly bear to find out. “Horse” is not a grim book, but it did sometimes make me very angry, and it did make me cry. “Horse” is a reminder of the simple, primal power an author can summon by creating characters readers care about and telling a story about them — the same power that so terrifies the people so desperately trying to get Toni Morrison banned from their children’s reading lists.

Maggie Shipstead is the author of “Seating Arrangements,” “Astonish Me,” “Great Circle” and “You Have a Friend in 10A.”

By Geraldine Brooks

Viking. 416 pp. $28

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Horse by Geraldine Brooks review – a confident novel of racing and race

The Australian-American author gallops through the life of a famed racehorse in the antebellum south but falters when she reaches modern America

I n a museum laboratory, a young osteologist – a scholar of bones – reassembles the skeleton of a 19th-century racehorse. The animal has spent decades fixed too haughtily upright; a prim parody of a thoroughbred. Rewired, he may run again, if only in the imaginations of those who stare at his bare, beautiful frame.

In her sixth novel, Horse, Geraldine Brooks attempts the same feat on the page – setting loose a history-bound stallion. Her subject is the famed Kentucky thoroughbred Lexington, king of the antebellum racetrack. “A horse so fast that the mass-produced stopwatch was manufactured so his fans could clock times in races that regularly drew more than twenty thousand spectators,” Brooks marvels. “A horse so handsome, that the best equestrian artists vied to paint him.” Lexington was famously virile, too, the greatest sire of his age; the father of dynasties and battle steeds.

But underneath the romance lies a dark inevitability: antebellum horseracing was an industry of white prestige built on the plundered labour of Black horsemen. “As I began to research Lexington’s life, it became clear to me that this novel could not merely be about a racehorse,” Brooks explains in her afterword. “It would also need to be about race.” It’s the kind of solemn and virtuous statement that can make a reader wary; that unmistakable whiff of good intentions.

In green-pastured Kentucky in the early 1850s, an itinerant artist – a painter of rich men’s horses – is struck by the beauty of a white-socked foal, and captures the animal on canvas. Watching him paint is Jarret, an enslaved groom who will tend to the horse until its dying breath. It is the last defiant decade of US slavery, and the boy and the horse will be bought and sold together. “A racehorse is a mirror,” the painter tells Jarret, “and a man sees his own reflection there.”

More than 160 years later, an oil painting of a white-socked horse is dumped on the roadside in Washington DC. It’s salvaged by Theo, a graduate student with an equine fixation. The equestrian art of the antebellum south often includes Black stablemen, and Theo is writing his PhD on the dehumanising equivalences these paintings make between man and beast – the gilt-edged boast of ownership.

Horse moves between Lexington’s record-breaking life and his cultural afterlife; between Jarret’s world and Theo’s. Jarret is denied the dignity of his own name; Theo is the poshly educated son of diplomats; but both are living in policed Black bodies. Horse is a tale of America’s inescapable and ever-braided legacies: the mythic and the monstrous.

Brooks cut her journalistic teeth on the racing beat, and she knows her way around a horse. This book returns the Australian-American novelist to the terrain that won her a Pulitzer prize with March , her 2005 tale of the war-absent father from Little Women. She brings the same archival confidence and sensory flair to the antebellum racetrack. Jarret’s portion of Horse is exactly the novel you’d expect: bloodlines and broodmares; farriers and knackeries; wild gambles, wild gallops and plantation-era grotesqueries. A dollop of civil war valour. And at the centre of it all, love story: a boy and his horse.

It’s when Brooks resurfaces in the near-present that Horse falters. With his elaborate backstory, convenient thesis and issue-prodding love interest, Theo’s story feels machine-tooled. Raised outside the US, he’s as naive as he is worldly – a man on a collision course with American injustice.

But there’s more than didacticism at play, for Lexington’s history is full of serendipities. An original painting of the racehorse was indeed rescued from street garbage, and his skeleton was discovered lurking in the attic of the Smithsonian. It’s possible to connect the stallion to General Ulysses S Grant and to Jackson Pollock’s reckless death. Brooks cannot bear to leave these details out. Who could? And so Horse crowbars its characters into these cosmic accidents. Six degrees of equine.

But with tender precision, Horse shows us history in flux. As Theo researches his abandoned painting, he encounters the devoted boffins who work to enrich the story we tell of the past: archivists, curators, scientists. It’s here that our osteologist makes an appearance, with her lab of flesh-eating beetles and bleached bones. When a skeleton is hung well, she explains, the armature disappears: “A really good mount allow[s] a species to tell its own story.” A really good historical novel does the same thing, letting the past stretch out into a wild and beastly shape. Horse has strong bones – but the struts and wires are showing.

Horse by Geraldine Brooks is published by Hachette on 15 June in Australia ($39.99) and 16 June in the UK, and by PRH in the US

- Geraldine Brooks

- Australian book reviews

- Australian books

- Horse racing

Most viewed

Geraldine Brooks

401 pages, Hardcover

First published June 14, 2022

About the author

Ratings & Reviews

What do you think? Rate this book Write a Review

Friends & Following

Community reviews.

"Equestrian portrait art of that era was a highly specialized field and only flourished briefly--after the Civil War, photography quickly supplanted it. There were few painters of note. Troye, of course, was the master. According to the database, Scott was his student. It was a small world they moved in--wealthy turf enthusiasts, one recommending his painter to the other."

"Whenever Jarret recalled that first morning in New Orleans, it was the noise and the smell that came back to him most vividly. Through the thicket of ship masts, he glimpsed bright ensigns of every nation fluttering in the slight breeze. Sweating men stacked bales and crates on the crowded dockside. Carefully, he led the horse down the gangway and into a wall of sound and scent--the medley of languages that, later he would be able to distinguish as French and Spanish, Italian and Portuguese, but that first morning blended into a musical blur. The smells were various, pungent: the tang of sassafras, the biscuit aroma of fat and flour roasting together into rich, dark roux, the intoxicating fragrance of jasmine, roses, magnolias and gardenias, and the intense perfumes of the women--old, young, their complexions every shade from linen through honey, pecan, ebony--in expensive fabric or simple calico, clothed and ornamented with more care and style than any women he had ever seen."

Join the discussion

Can't find what you're looking for.

- print archive

- digital archive

- book review

[types field='book-title'][/types] [types field='book-author'][/types]

Viking, 2022

Contributor Bio

Bailey sincox, more online by bailey sincox.

- Lucy by the Sea

- Our Country Friends

by Geraldine Brooks

Reviewed by bailey sincox.

“Historical fiction” may be one name for Geraldine Brooks’s craft, but that label doesn’t do her novels justice. Her Pulitzer Prize-winner, March (2005) , spotlights the taciturn father from Little Women. A transcendentalist compelled to enter the Union Army, he is a man of ideas struggling to become a man of action. People of the Book (2008) follows a Jewish manuscript from medieval Spain to modern Bosnia through exile, conflict, and genocide. Brooks’s novels don’t just use history as backdrop; they plumb the depths of the past in search of wisdom for the present.

Horse brings together the best parts of Brooks’s earlier work. It combines March ’s focus on the American Civil War with People of the Book ’s multiple narrators. Like March , Horse focuses on a character, while also centering on objects, like People of the Book .

The title refers to the label on a skeleton gathering dust in the Smithsonian’s attic. As it turns out, “Horse” is as much of a misnomer for Lexington, called “the greatest thoroughbred stud sire in racing history,” as “historical fiction” is for Horse. In Washington, D.C. in 2019, Jess, a zoologist, is called to restore Lexington’s newly-identified bones for public display. She collaborates with Theo, an art historian, who finds a painting of a horse in his neighbor’s garbage. This is the premise for Brooks’s latest transhistorical, when-worlds-collide plot.

Jess and Theo’s stories are interspersed with that of Jarret, Lexington’s groom, during the 1850s and 60s. Born into slavery in Kentucky, Jarret bonds with a colt called Lexington, setting out to prove that “all men are equal on the turf or under it” and hoping to win enough at the races to purchase his freedom. Lexington grows famous for his speed and endurance under Jarret’s care, but, by 1854, “the enmity is grown so great that even the turf provides no neutral ground.” Sold, along with Lexington, first to a New Orleans entrepreneur, then back to Kentucky, Jarret watches the Civil War unfold from the South’s elite stables. In 2019, Jess and Theo know nothing about Jarret. Nevertheless, they use the evidence they have to reconstruct his world.

In Horse, Brooks examines what others have overlooked. Like Horse ’s protagonists, she rummages through what looks like junk, searching for treasure. Jess rescues Lexington’s bones and “articulates” them; Theo salvages the painting to restore it. These objects carry traces of the past that need to be studied in order to be understood—and in order for their full stories to be told.

Part Da Vinci Code and part Nickel Boys, Horse draws readers into a historical mystery: what made Lexington so great? If he was so great, why was he forgotten? ( Seabiscuit gets a shoutout, too.) In its search for answers, the novel wavers between awe and indignation. While many of the novel’s characters are historical figures (abolitionist Cassius Clay, art dealer Martha Jackson, Lexington himself), Jarret is just a figure in a painting—the painting of Lexington “led by Black Jarret, his groom” recorded in an artist’s catalogue. A painting that’s now lost.

At the novel’s heart, then, is a more important question: how did we forget about Jarret? The bitter fact of knowing more about the horse than the man is not lost on Brooks. She elevates the history of Black grooms, trainers, and jockeys even as she underscores the disturbing interchangeability of the men with the horses they rode. When the New Orleans horse racing impresario Ten Broek says “this [ … ] is my Jarret. He knows the horse. Follow his advice in every particular, as if his instructions were my own,” Jarret “trie[s] to ignore the dissonant clanging of Ten Broeck’s words. My horse. My Jarret. New grandstands, new barns—did the man just buy up everything he wanted in this world?” This is Horse ’s strength: it depicts dignity and indignity at once. It asks readers to remember the passion and expertise Black men brought to the sport of horse racing and to recognize the violence that kept them out of its official record. As the novel shows, the horse whose legacy is preserved in museums, art galleries, and stud catalogues would not exist if not for the man whose life is irrecoverable except through fiction.

Horse may be better on the past than the present. The novel’s attempts to depict the Black Lives Matter movement and other current events can be clunky. But its spirit of humility and humanity prevails. Words directed at a collector buying Lexington’s painting may as well be directed at Brooks: “I guess you like horses.” Like her, Brooks responds: “It’s far more complicated than that.” Horse shows us just how complicated it is.

Published on September 6, 2022

Like what you've read? Share it!

Geraldine Brooks Probes Racing—and Race—in Her New Historical Novel, Horse

The Pulitzer Prize winner explores the unwritten true tale of America’s most famous racehorse—and uses that story to show how far we need to go in confronting systemic racism.

Our editors handpick the products that we feature. We may earn commission from the links on this page.

Don’t let the title fool you; Geraldine Brooks’s Horse is not Black Beauty for grown-ups. Yes, the title character is one of history’s most famous equine celebrities, a foal named Darley, who later became a pop culture phenomenon called Lexington—and was revered as the fastest horse in the world. But first and foremost, Horse is a thrilling story about humanity in all its ugliness and beauty.

Lexington is one of several characters in the book—the rest of them human—based on real-life figures, as Horse is a product of careful research fleshed out with vivid imagination. It’s a technique that has served Brooks well; she earned a Pulitzer Prize for March, which follows the fictional father in Little Women, based in part on the real-life Bronson Alcott. But while the historic detail in the book is impressive, it’s the fictions filling in the blanks where Brooks’s genius truly shines.

Arguably the central character is Jarrett, the enslaved groom who raised Darley from a foal and risks his own life more than once to protect the horse. In her fascinating afterword, Brooks explains that she was inspired to create Jarrett after reading about a missing painting by equestrian artist T.J. Scott, described in an 1870 issue of Harper’s New Monthly Magazine as depicting Lexington being led by “black Jarrett, his groom.” With no further information about the man available, Brooks took his name and created a complex individual, realizing the true scope of Horse. During her research into 19th-century racing, she found, as she writes in her end note, “this thriving industry was built on the labor and skill of Black horsemen, many of whom were, or had been, enslaved…it became clear to me that this novel could not merely be about a racehorse, it would also need to be about race.”

The lost painting features in the book as well, as Brooks imagines a dramatic and violent history for it that connects characters and time periods. In 1954, Martha Jackson, a female dealer in a male-dominated art world, stumbles upon a similar work that is tangentially involved in the death of Jackson Pollock. In 2019, Jess seeks portraits of Lexington to help reshape his skeleton for an exhibit, and Theo, a Lagos-born, Oxford-educated art historian, finds a cast-off horse painting and begins studying equine art through a post-colonial lens. Examining a portrait of a thoroughbred named Richard Singleton alongside several Black grooms, titled Richard Singleton with Viley’s Harry, Charles, and Lew, Theo thinks that the artist “may have portrayed these men as individuals, but perhaps only in the same clinical way that he exactly documented the splendid musculature of the thoroughbred. It was impossible not to suspect some equivalence between the men and the horse: valued, no doubt, but living by the will of their enslaver, submitting to the whip.” He goes on to notice that, “while the horse had two names, the men had only one.”

Horse unfolds in chapters told from various points of view, and each time the reader is reunited with Jarrett, the chapter bears the name of his enslaver, as the groom might have been described in a painting’s title: Warfield’s Jarrett, Ten Broeck’s Jarrett, Alexander’s Jarrett. It’s a device that forces the reader to consider a world in which gifted horses are valued more than human beings. And that’s not the only big question Horse asks. At a research facility studying the declining population of North Atlantic whales, Jess muses on “the artistry and the ingenuity of our own species,” and wonders, “How could we be so creative and destructive at the same time?” But far from being a preachy cautionary tale about man’s inhumanity to man and beast, this novel is a page-turner that reads like a series of mysteries: Who is this horse? Who was his groom? What happened to their shared portrait?

While those explorations drive the plot, it’s the voices of the different characters, each so distinct, that make the novel as delightful to read as it is thought-provoking. In 2019, Jess thinks, “careers can be as accidental as car wrecks.… Not many girls from Burwood Road in western Sydney got to go to French Guiana and bounce through the rainforest with scorpion specimens pegged across the jeep like so much drying laundry.” In 1854, Jarrett observes that “to be spoken of as livestock was as bitter as a gallnut.” And that same year, the equine painter, gambler, and sometime reporter Thomas J. Scott muses, “Modest winnings, payments for reportage—as ever, paltry and laggard—would not have kept me long in New Orleans, a city whose ample pleasures are a constant tax upon the purse.” The care with which Brooks crafts each character’s voice is a plea to look past the categorical labels and legends with which we describe each other, to truly see the individual. Paired with a compelling plot, the evocative voices create a story so powerful, reading it feels like watching a neck-and-neck horse race, galloping to its conclusion—you just can’t look away.

The Best Anne Lamott Quotes

The Most Addictive Reads of All Time

You Can Run, but You Can’t Hide

Lara Love Hardin’s Remarkable Journey

These New Novels Make the Perfect Backyard Reads

Books that Will Put You to Sleep

The Other Secret Life of Lara Love Hardin

The Best Quotes from Oprah’s 104th Book Club Pick

The Coming-of-Age Books Everyone Should Read

Pain Doesn’t Make Us Stronger

How One Sentence Can Save Your Life

White Author, Black Paragons

When writing across cultural divides flattens characters

I t’s 2019 in Washington, D.C. , and Theo is changing his art-history dissertation after finding a painting of a horse in his neighbor’s giveaway pile. He is 26 years old, a Black Londoner (his mother is Yoruba, his father Californian) and a former star polo player. He left the sport for academia because of relentless racist harassment, and now studies stereotypes of Africans in British painting. The working title for his dissertation is Sambo, Othello, and Uncle Tom: Caricature, Exoticization, Subalternization, 1700–1900 . He jogs with his dog for exercise, careful to wear his Georgetown shirt because “his favorite run took him through lily-white Northwest Washington and Daniel, his best friend at Yale, had instructed him that a Black man, running, should dress defensively.” Because he’s from the U.K., he may not understand all the nuances of American racism, but he understands enough. When the lady across the street, from whom he got the horse painting, flinches as he approaches to help her, he feels “the usual gust of anger” and takes a deep breath, saying to himself: “Just a White woman, White-womaning.”

Explore the July/August 2022 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Theo might be chagrined to find himself a protagonist in Horse , Geraldine Brooks’s latest work of historical fiction, which braids his story with the narrative of Jarret, an enslaved groom of the horse in the 19th-century painting Theo finds. For one, Theo is skeptical of white artists taking on Black subjects. The original hypothesis of his dissertation is that the Africans in British portraits were rendered less as people than as objects: “His argument mirrored Frederick Douglass’s caustic essay , arguing that no true portraits of Africans by White artists existed; that White artists couldn’t see past their own ingrained stereotypes of Blackness.”

This is a self-conscious—and bold—inclusion for a novel with not one but two young Black male protagonists written by a 66-year-old white Australian woman. Brooks is a skilled journalist and an acclaimed novelist, and Horse is not her first foray into historical fiction set in part during the American Civil War. Her novel March is narrated primarily by the father in Little Women , and tells the story of Mr. March’s years as a chaplain for the Union Army. That novel won the Pulitzer Prize in 2006. Neither is this her first time writing across cultural divides. Her first nonfiction book, Nine Parts of Desire (1994) , was about the “hidden world of Islamic women.” Her 2011 novel, Caleb’s Crossing , is about a young white Puritan girl’s friendship with Caleb Cheeshahteaumauk , a character inspired by a Wampanoag man of the same name who was the first Native American to graduate from Harvard, in 1665.

This kind of venture has become trickier in the past 10 years. The publishing world has been racked by overdue debate about cultural appropriation and whether and how white authors should write characters from other racial or ethnic backgrounds. Five years after Brooks published Caleb’s Crossing , the white American writer Lionel Shriver gave a notorious keynote speech— briefly donning a sombrero —at a Brisbane literary festival, ranting about the “clamorous world of identity politics” and the threat she felt it posed to literature: “The kind of fiction we are ‘allowed’ to write is in danger of becoming so hedged, so circumscribed, so tippy-toe, that we’d indeed be better off not writing the anodyne drivel to begin with.” Retorts and replies followed. “ It is possible to write about others not like oneself , if one understands that this is not simply an act of culture and free speech, but one that is enmeshed in a complicated, painful history of ownership and division,” the novelist Viet Thanh Nguyen observed. More recently, the blockbuster turned critical conflagration American Dirt (a novel about migrant trauma, for which its white author was paid a seven-figure advance ) set off months of heated articles. Some pointed out that immigrants remain under-published and underpaid for their own stories in the American media market; others objected to the implication that any identity-based limits should be placed on a fiction writer’s license.

In putting Douglass’s argument so early in the book—on page 57—Brooks signals to us that she enters her latest project knowingly. She’s read up on the Discourse. A gauntlet has been thrown—white artists can’t do justice to Black subjects—and she will take it up. Despite her evident efforts, the book does not turn out to be the counterexample she might have hoped.

H orse started with a real horse: Lexington, who was one of the great racehorses of the 19th century and a prolific sire. When Lexington died, his skeleton became an exhibit but was later forgotten in the attic of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History . Brooks, a horsewoman herself, grew fascinated with the painter Thomas J. Scott, who did several portraits of Lexington, and she was especially curious about one of Scott’s portraits that remains missing. A description of that painting in a July 1870 issue of Harper’s magazine describes Lexington being led by “black Jarret, his groom.” Nothing else is known about the real Jarret, and Horse grew out of Brooks’s imaginings of the life he might have lived. She had wanted to write about horses, she admits in her afterword. But as she researched horse racing in the antebellum South, “it became clear to me that this novel could not merely be about a racehorse; it would also need to be about race.”

The structure of the novel is poly-vocal, occupying a loose, floating third person as its short chapters jump among its cast of characters. The story is bounded historically by 2020 in Washington, D.C., where Theo’s find is identified as a lost 19th-century portrait of Lexington, and the 1850s at several southern horse-breeding farms, where Jarret, a gifted and reserved young horse trainer, develops a spiritual, even psychic connection with a newborn foal named Darley, who will later become famous as Lexington. The boy and the horse become best friends and deeply bonded partners. “That horse about the only one thing I care for,” Jarret declares. Though his father, also a horse trainer, has bought his own freedom, Jarret remains enslaved, and his story line is fraught with vulnerability: Jarret and Lexington are sold together from one wealthy landowner to another, to another.

Occasionally, the book swerves to the 1950s in New York, where Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner make an appearance: Their friend, an art dealer named Martha Jackson, acquires one of the lost Lexington paintings from her maid, who seems to have inherited it from an ancestor connected to Jarret. (This third era’s plot, which is also based in historical fact, is notably less developed than the other two.) Sometimes Jarret’s perspective dominates in the novel; other times Scott’s or Theo’s vantage prevails—or that of Jess, a young white Australian woman who’s pursuing her fascination with zoological research at the Smithsonian in 2019; or that of Mary, the young daughter of the white emancipationist Cassius Clay and a frequent presence at the Meadows, the farm where Jarret and his father work. Intermittently, Brooks serves up a mix of multiple viewpoints over the course of a single chapter.

But in spirit, the book belongs to Jarret and Theo, with complementary foils in the form of the two young white women. (While there are several Black female characters in the book, none is granted complex interiority.) In 2019, Theo begins to date Jess, despite some ambivalence. In 1850, Mary likes to hang around the barns and talk to Jarret (who is two years older) while he works. Brooks has taken pains to make both women flawed: Whereas Jarret and Theo are carefully dressed, meticulous, and possessed of “impeccable manners,” these women are often careless, unkempt, emotionally fragile—and racist without quite knowing it. Jess and Theo meet because she assumes he’s stealing her bike. She’s then so embarrassed by her behavior that she tells him she found the incident traumatic. (“Typical, Theo thought. He’d been accused, yet she was traumatized.”) When Mary is angry, she reminds Jarret that he’s enslaved, and then feels hurt later when she tells him that she considers them friends and he is too incredulous at the idea to reciprocate.

Brooks clearly attempts to demonstrate self-awareness, to preemptively deflect any criticism that she has favored the characters whose life experience most resembles her own—but the dynamic she creates between Theo and Jess and between Jarret and Mary flattens all the characters. Theo and Jarret are described, at every turn, as exemplary, socially and spiritually. They are handsome, tall, gifted, and educated (Jarret takes an opportunity to learn how to read). Animals instinctively trust them (Theo and his dog are exquisitely attuned). They are constantly swallowing their rage. They are always patiently explaining something. Where others stumble, they are steady. Theo tells Jess at one point that he wants to help his old-lady neighbor even if she’s racist, because “ ‘whatever she might be, it doesn’t mean that I won’t do what I know to be right.’ Jess sighed, defeated, and smiled at him. ‘You’re just a better person than me, I guess.’ ”

Theo is a better person than Jess, no doubt, but Brooks grants Jess something that she denies Theo—and to a degree Jarret. Jess gets to fail; Jess gets to change. By contrast, Theo is static. Sometimes he reads like a caricature: “He was his own man long before any of his peers even realized that was an option. He’d embraced life as a rootless loner, at home in the world but belonging nowhere in particular. Comfortable with a wide range of people, close to very few.” He remains angry but patient, smart, gentlemanly, and gentle to the end.

Jarret, the most rounded of the many characters who take turns narrating Horse , changes less than you would expect given that the story tracks him from adolescence into his late 30s. His spiritual evolution is condensed into two formative episodes. In the first, he is saved by Mary and her father from an ill-conceived escape attempt, and he learns thereafter to control his anger and work within the constraints of his enslavement. The second leap forward—which is presented as his real moral maturation—comes when he is briefly forbidden to care for Lexington and is sent to labor in the fields, where he is whipped.

Startlingly, this is framed as a blessing:

He conceived, in those hard days, a renewed gratitude toward his father, who had endured hardship to rise to a measure of dignity that had extended its protective cloak over Jarret’s childhood. He learned, in those fields, what he had been spared. He felt a new understanding for the folk who bore it, and an admiration for those brave enough to risk everything to run away from such a life. An empathy grew in him. He began to watch people with the sensitive attention he’d only ever accorded his horses … Even as his world contracted and pressed in upon him, in equal measure his heart expanded.

When Jarret finally reunites with Lexington and leaves that plantation, he reflects that “he wasn’t sorry to have seen what he’d seen, and learned what he learned. Not just the book learning. He felt larger in spirit. There was a space in his soul for the suffering of people. He resolved to take account of their lives, the heavy burdens they carried.”

These passages call to mind the history of white people insisting that whippings under chattel slavery were an experience of moral training upon which the enslaved might reflect with sanguine gratitude—a history that Brooks is aware of but nevertheless echoes here. Jarret, an emotional teenager who doesn’t seem to lack empathy in the first place, is turned into a saint, floating somewhat above the action.

I keep thinking about Parul Sehgal’s elegant panning of American Dirt , in which she joins the novelist Hari Kunzru in arguing that “imagining ourselves into other lives and other subjectives is an act of ethical urgency.” Transracial authorial imagining, she writes, is a profound undertaking. “The caveat is to do this work of representation responsibly, and well.” Brooks’s attempt is made earnestly, but not well. In keeping with the character construction, the plot itself veers toward formula. Horse relies on ungainly cliff-hangers to pull the reader from chapter to chapter. (In one, Jess inspects Lexington’s skeleton in 2019 and concludes, “Something had happened to this horse when it was alive. Something dreadful.”) The romance is bland. (“Was it the wine, or was she becoming infatuated with this man?”) The details occasionally inspire a flinch (describing an enslaved young man as a “dusky youth”), and the moments when Brooks addresses racism more directly can read as self-conscious and pedantic. (“Look. It’s not your fault you get to move easy in the world,” Theo’s friend Daniel tells Jess after an act of violence. “We just can’t afford to.”)

Brooks is an accomplished writer, and many of her gifts are evident amid the clumsiness of the overall effort. The relationship between Jarret and Lexington is intimate and compelling. When they are briefly separated, the uncertainty of their reunion feels like an existential crisis. Brooks has a talent and passion for research that is fully expressed here—she writes beautifully about the anatomy of horses and the delicate work of “articulating” their skeletons, arranging every bone in its proper place. The descriptions of 19th-century horse racing, when the animals were bred differently and raced much longer tracks, are thrilling. Brooks has attended with equal care to the quotidian details of each era (corn pone in the antebellum South, bebop for Jackson Pollock, mid-century-modern furniture for Theo).

I read to the end wanting Horse to right itself, to be one of those books that achieve the creative and ethical intersubjectivity that signals great fiction. Brooks gives Jarret and Theo just enough spark to make us wish she’d also given them a more deeply imagined, nuanced, and substantial portrayal. Each ends as a trope: one a man who triumphs against all odds, the other a martyr. Brooks’s sympathies are evidently with them, and so are ours. But sympathy seems like an inadequate achievement in a project like this, which takes as its subject the worst consequences of white Americans’ failure to recognize the full humanity of Black people. Sympathy has a way of falling short, aesthetically as well as politically—it is a frail substitute for the knotty, vital insight that can emerge from sustained immersion in another psyche, another soul. If readers feel sorry for Theo and Jarret without really needing to believe in them as whole beings, what exactly do their portraits accomplish?

This article appears in the July/August 2022 print edition with the headline “A White Author Fails Her Black Characters.”

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

- ADMIN AREA MY BOOKSHELF MY DASHBOARD MY PROFILE SIGN OUT SIGN IN

Awards & Accolades

Our Verdict

New York Times Bestseller

IndieBound Bestseller

by Geraldine Brooks ‧ RELEASE DATE: June 14, 2022

Strong storytelling in service of a stinging moral message.

A long-lost painting sets in motion a plot intertwining the odyssey of a famed 19th-century thoroughbred and his trainer with the 21st-century rediscovery of the horse’s portrait.

In 2019, Nigerian American Georgetown graduate student Theo plucks a dingy canvas from a neighbor’s trash and gets an assignment from Smithsonian magazine to write about it. That puts him in touch with Jess, the Smithsonian’s “expert in skulls and bones,” who happens to be examining the same horse's skeleton, which is in the museum's collection. (Theo and Jess first meet when she sees him unlocking an expensive bike identical to hers and implies he’s trying to steal it—before he points hers out further down the same rack.) The horse is Lexington, “the greatest racing stallion in American turf history,” nurtured and trained from birth by Jarret, an enslaved man who negotiates with this extraordinary horse the treacherous political and racial landscape of Kentucky before and during the Civil War. Brooks, a White writer, risks criticism for appropriation by telling portions of these alternating storylines from Jarret’s and Theo’s points of view in addition to those of Jess and several other White characters. She demonstrates imaginative empathy with both men and provides some sardonic correctives to White cluelessness, as when Theo takes Jess’ clumsy apology—“I was traumatized by my appalling behavior”—and thinks, “Typical….He’d been accused, yet she was traumatized.” Jarret is similarly but much more covertly irked by well-meaning White people patronizing him; Brooks skillfully uses their paired stories to demonstrate how the poison of racism lingers. Contemporary parallels are unmistakable when a Union officer angrily describes his Confederate prisoners as “lost to a narrative untethered to anything he recognized as true.…Their fabulous notions of what evils the Federal government intended for them should their cause fail…was ingrained so deep, beyond the reach of reasonable dialogue or evidence.” The 21st-century chapters’ shocking denouement drives home Brooks’ point that too much remains the same for Black people in America, a grim conclusion only slightly mitigated by a happier ending for Jarret.

Pub Date: June 14, 2022

ISBN: 978-0-39-956296-9

Page Count: 416

Publisher: Viking

Review Posted Online: March 15, 2022

Kirkus Reviews Issue: April 1, 2022

LITERARY FICTION

Share your opinion of this book

More by Geraldine Brooks

BOOK REVIEW

by Geraldine Brooks

edited by Geraldine Brooks

More About This Book

SEEN & HEARD

by Kristin Hannah ‧ RELEASE DATE: Feb. 6, 2024

A dramatic, vividly detailed reconstruction of a little-known aspect of the Vietnam War.

A young woman’s experience as a nurse in Vietnam casts a deep shadow over her life.

When we learn that the farewell party in the opening scene is for Frances “Frankie” McGrath’s older brother—“a golden boy, a wild child who could make the hardest heart soften”—who is leaving to serve in Vietnam in 1966, we feel pretty certain that poor Finley McGrath is marked for death. Still, it’s a surprise when the fateful doorbell rings less than 20 pages later. His death inspires his sister to enlist as an Army nurse, and this turn of events is just the beginning of a roller coaster of a plot that’s impressive and engrossing if at times a bit formulaic. Hannah renders the experiences of the young women who served in Vietnam in all-encompassing detail. The first half of the book, set in gore-drenched hospital wards, mildewed dorm rooms, and boozy officers’ clubs, is an exciting read, tracking the transformation of virginal, uptight Frankie into a crack surgical nurse and woman of the world. Her tensely platonic romance with a married surgeon ends when his broken, unbreathing body is airlifted out by helicopter; she throws her pent-up passion into a wild affair with a soldier who happens to be her dead brother’s best friend. In the second part of the book, after the war, Frankie seems to experience every possible bad break. A drawback of the story is that none of the secondary characters in her life are fully three-dimensional: Her dismissive, chauvinistic father and tight-lipped, pill-popping mother, her fellow nurses, and her various love interests are more plot devices than people. You’ll wish you could have gone to Vegas and placed a bet on the ending—while it’s against all the odds, you’ll see it coming from a mile away.

Pub Date: Feb. 6, 2024

ISBN: 9781250178633

Page Count: 480

Publisher: St. Martin's

Review Posted Online: Nov. 4, 2023

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Dec. 1, 2023

FAMILY LIFE & FRIENDSHIP | GENERAL FICTION | HISTORICAL FICTION

More by Kristin Hannah

by Kristin Hannah

PERSPECTIVES

BOOK TO SCREEN

by Max Brooks ‧ RELEASE DATE: June 16, 2020

A tasty, if not always tasteful, tale of supernatural mayhem that fans of King and Crichton alike will enjoy.

Are we not men? We are—well, ask Bigfoot, as Brooks does in this delightful yarn, following on his bestseller World War Z (2006).

A zombie apocalypse is one thing. A volcanic eruption is quite another, for, as the journalist who does a framing voice-over narration for Brooks’ latest puts it, when Mount Rainier popped its cork, “it was the psychological aspect, the hyperbole-fueled hysteria that had ended up killing the most people.” Maybe, but the sasquatches whom the volcano displaced contributed to the statistics, too, if only out of self-defense. Brooks places the epicenter of the Bigfoot war in a high-tech hideaway populated by the kind of people you might find in a Jurassic Park franchise: the schmo who doesn’t know how to do much of anything but tries anyway, the well-intentioned bleeding heart, the know-it-all intellectual who turns out to know the wrong things, the immigrant with a tough backstory and an instinct for survival. Indeed, the novel does double duty as a survival manual, packed full of good advice—for instance, try not to get wounded, for “injury turns you from a giver to a taker. Taking up our resources, our time to care for you.” Brooks presents a case for making room for Bigfoot in the world while peppering his narrative with timely social criticism about bad behavior on the human side of the conflict: The explosion of Rainier might have been better forecast had the president not slashed the budget of the U.S. Geological Survey, leading to “immediate suspension of the National Volcano Early Warning System,” and there’s always someone around looking to monetize the natural disaster and the sasquatch-y onslaught that follows. Brooks is a pro at building suspense even if it plays out in some rather spectacularly yucky episodes, one involving a short spear that takes its name from “the sucking sound of pulling it out of the dead man’s heart and lungs.” Grossness aside, it puts you right there on the scene.

Pub Date: June 16, 2020

ISBN: 978-1-9848-2678-7

Page Count: 304

Publisher: Del Rey/Ballantine

Review Posted Online: Feb. 9, 2020

Kirkus Reviews Issue: March 1, 2020

GENERAL SCIENCE FICTION & FANTASY | GENERAL THRILLER & SUSPENSE | SCIENCE FICTION

More by Max Brooks

by Max Brooks

- Discover Books Fiction Thriller & Suspense Mystery & Detective Romance Science Fiction & Fantasy Nonfiction Biography & Memoir Teens & Young Adult Children's

- News & Features Bestsellers Book Lists Profiles Perspectives Awards Seen & Heard Book to Screen Kirkus TV videos In the News

- Kirkus Prize Winners & Finalists About the Kirkus Prize Kirkus Prize Judges

- Magazine Current Issue All Issues Manage My Subscription Subscribe

- Writers’ Center Hire a Professional Book Editor Get Your Book Reviewed Advertise Your Book Launch a Pro Connect Author Page Learn About The Book Industry

- More Kirkus Diversity Collections Kirkus Pro Connect My Account/Login

- About Kirkus History Our Team Contest FAQ Press Center Info For Publishers

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Reprints, Permission & Excerpting Policy

© Copyright 2024 Kirkus Media LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Popular in this Genre

Hey there, book lover.

We’re glad you found a book that interests you!

Please select an existing bookshelf

Create a new bookshelf.

We can’t wait for you to join Kirkus!

Please sign up to continue.

It’s free and takes less than 10 seconds!

Already have an account? Log in.

Trouble signing in? Retrieve credentials.

Almost there!

- Industry Professional

Welcome Back!

Sign in using your Kirkus account

Contact us: 1-800-316-9361 or email [email protected].

Don’t fret. We’ll find you.

Magazine Subscribers ( How to Find Your Reader Number )

If You’ve Purchased Author Services

Don’t have an account yet? Sign Up.

The Book Report Network

- Bookreporter

- ReadingGroupGuides

- AuthorsOnTheWeb

Sign up for our newsletters!

Find a Guide

For book groups, what's your book group reading this month, favorite monthly lists & picks, most requested guides of 2023, when no discussion guide available, starting a reading group, running a book group, choosing what to read, tips for book clubs, books about reading groups, coming soon, new in paperback, write to us, frequently asked questions.

- Request a Guide

Advertise with Us

Add your guide, you are here:, reading group guide.

- Discussion Questions

Horse by Geraldine Brooks

- Publication Date: January 16, 2024

- Genres: Fiction , Historical Fiction

- Paperback: 464 pages

- Publisher: Penguin Books

- ISBN-10: 0399562974

- ISBN-13: 9780399562976

- About the Book

- Reading Guide (PDF)

- How to Add a Guide

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Newsletters

Copyright © 2024 The Book Report, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

- Bookreporter

- ReadingGroupGuides

- AuthorsOnTheWeb

The Book Report Network

Sign up for our newsletters!

Regular Features

Author spotlights, "bookreporter talks to" videos & podcasts, "bookaccino live: a lively talk about books", favorite monthly lists & picks, seasonal features, book festivals, sports features, bookshelves.

- Coming Soon

Newsletters

- Weekly Update

- On Sale This Week

- Spring Preview

- Winter Reading

- Holiday Cheer

- Fall Preview

- Summer Reading

Word of Mouth

Submitting a book for review, write the editor, you are here:.

Pulitzer Prize winner Geraldine Brooks’ latest novel, HORSE, is an intriguing examination of enduring prejudices past and present. Split between two major time periods --- the 19th-century American South and 2019 Washington, D.C. --- along with a brief stopover in mid-20th-century New York City, the bookaddresses the overt and covert currents of racism pervading society throughout history.

The first narrative thread follows Jarret, an enslaved young Black man expertly skilled in horses who occupies an uneasy place in the world governed by his enslaver, Dr. Elisha Warfield. Jarret is close with his father, the formerly enslaved trainer Harry, and is treated with careless friendship by the young lady of the house --- without taking into account the trouble this might put him in.

"Brooks vividly illustrates the bond between the young man and the horse in a way that brings to life Jarret’s knowledge of animal husbandry and meticulous care for the creature."

But when a talented young horse eventually called Lexington is born on Warfield’s farm, Jarret becomes inextricably linked to the thoroughbred’s fate --- so much so that, when the colt is sold to another owner, so, too, is Jarret. No matter how much his enslavers profess to care for him or the cause of anti-slavery, they tolerate it and treat him as beneath their ultimate regard.

Parallel to this story is that of Theo, a brilliant arts graduate student at Georgetown University. Micro and macro aggressions interweave almost every aspect of his life that we see, from discussions with his neighbors to his first meeting with Australian curator Jess. That last awkward encounter peppers Theo’s growing personal and professional bond with Jess as they discover more about Lexington’s skeleton and a portrait depicting Jarret and the horse. One realizes that, as much as she tries, Jess can never understand the complexities and tragedies that Theo faces…especially as the novel reaches its tragic climax.

Brooks vividly illustrates the bond between the young man and the horse in a way that brings to life Jarret’s knowledge of animal husbandry and meticulous care for the creature. However, as she depicts not just the dangers of overt racism but also the effects of the “well-meaning” disregard of “kind” white people and how that endangers Black lives past and present, readers may wonder if Brooks is questioning her own narrative authority. She appears to be asking if she, too, is yet another “well-meaning” white writer telling Black stories. This is a good question, but one that she doesn't answer or use to elevate Black voices.

By taking a whole book to explore the privileges of white characters throughout the ages --- and, by extension, her own --- Brooks encourages her white audience to examine their own. What she stops short of, though, is demanding that they do something about it. That, instead, is up to the reader.

Reviewed by Carly Silver on July 1, 2022

Horse by Geraldine Brooks

- Publication Date: January 16, 2024

- Genres: Fiction , Historical Fiction

- Paperback: 464 pages

- Publisher: Penguin Books

- ISBN-10: 0399562974

- ISBN-13: 9780399562976

Book Review: Horse

By Geraldine Brooks ’83JRN. (Viking)

A story of present-day interracial romance woven together with a history of thoroughbred racing in the antebellum South, Horse , a new novel by Geraldine Brooks ’83JRN, is no safe bet. Yet readers who appreciate rigorous historical research and polished storytelling should certainly stay the course.

The novel opens in Washington, DC, where art historian Theo is rescuing a painting of Lexington, one of America’s most renowned racehorses, from his neighbor’s trash. Theo takes the artwork to the Smithsonian for evaluation and is introduced to Jess, who is restoring the skeleton of the same horse for an exhibit. The encounter is awkward: Theo, who is Black, recognizes Jess as the white woman who had earlier confronted him when she thought he was stealing her bike. Weeks later, when the couple begin to fall in love, Theo will wonder how to answer the question of how they met, since “being tacitly accused of bike theft wasn’t exactly a meet cute.”

The action then shifts to 1850, to the day Lexington is born on the Kentucky farm of the physician Elisha Warfield. Warfield promises Harry Lewis, a talented Black trainer, an interest in the racehorse in lieu of a year’s wages — an exciting prospect, since Lewis hopes to use any future winnings to buy the freedom of his son Jarret, whom Warfield has enslaved. Jarret proves to be as talented as his father. He spends all his waking hours with the horse, and through hard work and unwavering commitment he eventually raises one of the greatest racing stallions in turf history. Unfortunately, his father will never live to see or profit from this achievement.

Brooks is known for undertaking extensive research, and in the novel’s afterword she says that as she pored over archives she was struck by the stories of the Black grooms, trainers, and jockeys who played a “central role in the wealth creation of the antebellum thoroughbred industry.” These key figures, of course, are hidden in the margins of history, a place Brooks is always eager to explore. Her novel March , which won a Pulitzer Prize, imagined the Civil War experiences of chaplain John March, the fictional father of the girls in Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women . Caleb’s Crossing , set in 1665, told the story of the first Native American to graduate from Harvard College.

Horse shifts between Jarret in 1850 and Theo and Jess in 2019 (with a whistle stop in New York City in the 1950s), and it carries the heavy burden of acknowledging the deep roots and painful persistence of structural racism. Jarret averts his eyes when he is asked for his opinion, acknowledging that “it wasn’t a good idea to speak to a White stranger without putting a deal of thought into it. Words could be snares.” One hundred and seventy years later, Theo, the Oxford-educated, polo-playing son of civil servants, cannot escape the racist tropes that pollute the most mundane interactions. When he goes to help a neighbor with her shopping, she flinches with alarm. “Theo felt the usual gust of anger and took a deep breath. Just a White woman, White-womaning.”

Geraldine Brooks, of course, is also a white woman, writing from the perspective of an enslaved man and a multiracial student confronting the disappointing limits of “woke” culture. It’s a bold choice for a novelist, especially when debates over cultural appropriation in fiction are heated and divisive. Brooks seems aware of the risk. In the novel, Theo’s own thesis takes issue with Frederick Douglass’s argument “that no true portraits of Africans by White artists existed; that White artists couldn’t see past their own ingrained stereotypes of Blackness.” In the afterword, Brooks takes pains to point out that she sought insights into the contemporary Black experience from several early readers, including Bizu Horwitz, the son she and her husband, the late journalist Tony Horwitz ’83JRN, adopted from Ethiopia.

Brooks’s novel started out as a story about a racehorse, but as she began to research the history of thoroughbred racing in America, Brooks writes, “it became clear that this novel could not merely be about a racehorse, it would also need to be about race.” And in the end, the novel is all about race. Despite the book’s title, the horse, Lexington, becomes less of a major character and more of an also-ran, and by making that choice, the novelist raised the stakes.

More From Books

Sign up for our newsletter.

General Data Protection Regulation

Columbia University Privacy Notice

Horse: A Novel

- By Geraldine Brooks

- Reviewed by Patricia Schultheis

- June 28, 2022

A sweeping look at race — and racing — in America.

Horse by Geraldine Brooks, winner of the 2006 Pulitzer Prize for March , is a sprawling roman à clef covering nearly 170 years of American history, stretching from antebellum Kentucky to present-day Washington, DC. Thoroughbreds provide the unifying element for this far-reaching narrative, but horses and the complex culture surrounding them are only devices for Brooks to explore her fundamental subject: race and its corrosive influence on our nation’s foundation and cancerous impact on society today.

Told from the perspective of six characters, Horse interweaves the story of the Black equestrians who made their white masters fabulously wealthy with those of contemporary young professionals struggling to form relationships despite racial microaggressions and misunderstandings.

By far, the most compelling narrative is that of Jarret, an enslaved boy in Kentucky, whom Brooks describes as being “slow to master human speech, but he could interpret the horses: their moods, their alliances, their simple wants, their many fears. He came to believe that horses lived with a world of fear, and when you grasped that you had a clear idea how to be with them.”

Jarret understands the fear horses have because he, too, is wholly dependent on the whims of others for food and shelter. And like horses, he can be beaten or sold at any moment. In the antebellum South, horses and their enslaved attendants are commodities. Nothing more.

But the night he helps his father, a free man, with the birth of a white-footed foal, Jarret’s life begins to change. “He makes me feel — hopeful,” Jarret says of the animal. “Like the future gone matter more than it did the day before he come.” Eventually, the foal is named Lexington and goes on to become a legendary racer and an even more legendary sire.

Jarret and the horse develop a profound bond that enables the young man to gain some agency over his own life. As Lexington is sold, then sold again, Jarret is sold along with him, changing from Warfield’s Jarret to Ten Broeck’s Jarret to Alexander’s Jarret. Although he has no last name, Jarret gradually becomes literate, perceptive, disciplined, canny, and empathetic. Once freed, he becomes Jarret Lewis, no one’s man but his own.

Observing Jarret’s transformation from boy to man is Thomas J. Scott, an itinerant artist and writer hired by wealthy patrons to paint their horses. Scott’s narrative is the only one told in the first person — through his diaries — and Brooks does a wonderful job capturing the artist’s obsequious tone and cool detachment toward the moneyed gentry who pay him. Over the course of many years, Scott paints several pictures of Lexington. An early, rough one he gives to young Jarret. Later, Scott gives Jarret another one, although it, too, is imperfect.

Scott’s paintings form the basis for the chapters covering the 1950s and 2019, but Brooks, who so beautifully captures the nuanced and constant sense of threat permeating the Old South, fails to achieve similar tension with her contemporary characters. Martha Jackson, for instance, who buys one of Scott’s paintings from her maid, remains too slight to engross the reader. Yes, she does ultimately bequeath the work to the Smithsonian (an action that impacts later developments in Horse ), but a subplot involving her interactions with Jackson Pollock is needlessly distracting.

The more successful modern-day thread involves Jess, a white Australian conservator at the Smithsonian, and Theo, a Black doctoral student in art history. An African American in the sense that his father was American and his mother is Nigerian, Theo is a liminal figure, unencumbered by an ancestry of enslavement, yet impacted by today’s prejudice.

“Meet cute” might describe his initial collision with Jess, but “contrived” may be more accurate. Both ride expensive, blue Trek CrossRip bikes; both have lived in Canberra and know what a Kelpie is. (It’s an Australian sheepdog.) With this much in common, what could go wrong? Apparently, a lot.

Yet despite mixed messages and microaggressions, Jess and Theo begin a fitful relationship that might border on cliché if not for the fact that Brooks’ subject isn’t love. It’s race in America. And her gripping, tragic conclusion to Horse exemplifies the truth of Faulkner’s memorable assertion: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

Patricia Schultheis is the author of Baltimore’s Lexington Market , published by Arcadia Publishing in 2007, and of St. Bart’s Way , an award-winning story collection published by Washington Writers’ Publishing House in 2015. Her latest book is A Balanced Life , published by All Things That Matter Press in 2018.

Support the Independent by purchasing this title via our affliate links: Amazon.com Powell's.com Or through Bookshop.org

Book Review in Fiction More

Zeroes: A Novel

By chuck wendig.

A sluggishly paced thriller that suffers, in part, from its own immense scope.

- Science Fiction ,

Here Goes Nothing: A Novel

By steve toltz.

(The after) life is beautiful…or not.

Advertisement

- Member Login

- Library Patron Login

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR

FREE NEWSLETTERS

Search: Title Author Article Search String:

BookBrowse Reviews Horse by Geraldine Brooks

Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

by Geraldine Brooks

Critics' Opinion:

Readers' Opinion:

- Historical Fiction

- Washington DC

- Tenn. Va. W.Va. Ky.

- 19th Century

- Contemporary

- Books About Animals

- Top 20 Best Books of 2022

Rate this book

About this Book

- Reading Guide

Book Awards

- Media Reviews

- Reader Reviews

Historical artifacts related to the legendary thoroughbred racehorse Lexington serve as the backdrop to this dual timeline novel reckoning with racial inequality in America.

Winner: 2022 Best Fiction Award . Geraldine Brooks creates a powerful backstory for 19th-century thoroughbred racehorse Lexington, weaving a rich tapestry of historical and current-day narratives that aptly reflect how the legacy of slavery still ripples through America. Horse truly does offer something for every reader. Brooks seamlessly weaves fact and fiction, past and present, to tell the story of the remarkable Lexington and examine race in America. The real-life Lexington was not only known for his breathtaking speed and agility on the track, but also for his equally talented progeny. Brooks engineers a plausible biography for the horse, filling in the blanks with intriguing research as she traces the history of thoroughbred racing, including the impact of Black jockeys and the Civil War on the industry. This is complemented by compelling contemporary narratives that explore the complex dynamics of race and relationships today. The novel begins in 2019 with the dueling narratives of Theo, a Nigerian graduate student of the arts working on his thesis, and Jess, a white scientist working for the Smithsonian. Theo salvages a painting of a horse from his neighbor's garbage; Jess unearths horse bones discarded in a neglected attic space. These discoveries bring the characters together and a romantic relationship ensues, complicated by their divergent racial heritage. Jess is Australian and relatively new to the US, and is naive to the myriad concessions and considerations Theo must make due to the color of his skin. Alternately, while a victim of racism both subtle and overt, Theo purposefully tries to look beyond race. At one point, he discloses that he was judged by his former girlfriend as "insufficiently steeped in an experience of American Blackness" to date a Black woman. Despite Jess's protestations that race is not an issue, she first meets Theo when she mistakenly believes he is stealing her bicycle. Jess and Theo's narratives are entrancing enough to stand on their own as an engrossing read. Brooks is deft at characterization; more than once I found myself wanting to meet Jess or Theo at a local coffee shop so I could hear more of their stories. On the heels of Jess's and Theo's narratives comes Jarrett's, or as Brooks notably titles these sections, "Warfield's Jarrett," reflective of Dr. Warfield's ownership and underscoring Jarrett's status as a slave. Jarrett's story, beginning in 1850, narrates Lexington's time as a foal and Jarrett's deep and abiding connection with the horse. Jarrett is the son of trainer Harry Lewis, and is sold along with Lexington to various affluent, white horse owners. His tale traverses the early halcyon days of thoroughbred racing (as Jarrett becomes Lexington's primary caretaker and ultimately his trainer), through a daring escape from Confederate clutches during the Civil War, and Lexington's later days as a successful stud. The historic underpinnings of the work are as spellbinding as the characters. Whether Brooks is chronicling the history of thoroughbred racing, exploring the impact of the Civil War on African American jockeys, or detailing the nuances of American equestrian art, it is all equally engrossing. Likewise, each character's backstory is transfixing. The novel ends with a resounding and shocking crescendo that demands an examination of race in America today. Horse will buoy your soul, break your heart, educate your mind and leave you waiting for Brooks's next work. It is just that spectacular.

- "Beyond the Book" articles

- Free books to read and review (US only)

- Find books by time period, setting & theme

- Read-alike suggestions by book and author

- Book club discussions

- and much more!

- Just $45 for 12 months or $15 for 3 months.

- More about membership!

Beyond the Book: Black Jockeys: The Foundation of American Horse Racing

Read-alikes.

- Genres & Themes

If you liked Horse, try these:

The Last House on the Street

by Diane Chamberlain

Published 2023

About this book

More by this author

A community's past sins rise to the surface in New York Times bestselling author Diane Chamberlain's The Last House on the Street when two women, a generation apart, find themselves bound by tragedy and an unsolved, decades-old mystery.

Unbreakable

by Richard Askwith

Published 2021

The courageous and heartbreaking story of a Czech countess who defied the Nazis in a legendary horse race.

Support BookBrowse

Join our inner reading circle, go ad-free and get way more!

Find out more

BookBrowse Book Club

Members Recommend

The House on Biscayne Bay by Chanel Cleeton

As death stalks a gothic mansion in Miami, the lives of two women intertwine as the past and present collide.

The Stone Home by Crystal Hana Kim

A moving family drama and coming-of-age story revealing a dark corner of South Korean history.

Who Said...

Our wisdom comes from our experience, and our experience comes from our foolishness

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Solve this clue:

and be entered to win..

Your guide to exceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.

Subscribe to receive some of our best reviews, "beyond the book" articles, book club info and giveaways by email.

- Biggest New Books

- Non-Fiction

- All Categories

- First Readers Club Daily Giveaway

- How It Works

Get the Book Marks Bulletin

Email address:

- Categories Fiction Fantasy Graphic Novels Historical Horror Literary Literature in Translation Mystery, Crime, & Thriller Poetry Romance Speculative Story Collections Non-Fiction Art Biography Criticism Culture Essays Film & TV Graphic Nonfiction Health History Investigative Journalism Memoir Music Nature Politics Religion Science Social Sciences Sports Technology Travel True Crime

April 11, 2024

- An examination of colonialism in the Pacific

- Hamilton Nolan on Pamela Paul, and other columnists

- Revisiting Karl Marx’s The Eighteenth Brumaire

By the Book

Doris Kearns Goodwin Wasn’t Competing With Her Husband

Richard Goodwin, an adviser to presidents, “was more interested in shaping history,” she says, “and I in figuring out how history was shaped.” Their bond is at the heart of her new book, “An Unfinished Love Story: A Personal History of the 1960s.”

Credit... Rebecca Clarke

Supported by

- Share full article

Describe your ideal reading experience.

The early hours before dawn have always been best. I have all that is necessary: quiet, a bathrobe, a comfortable old blue leather couch, a table stacked with books and research.

What books are on your night stand?

Right now: “Three Roads Back,” a powerful book (especially after the death of my husband, Dick Goodwin ) on how Emerson, Thoreau and William James dealt with grief. “The Facts,” by Philip Roth, in which I am delighted to find a hilarious dinnertime conversation concerning the politics of divorce between Roth, Robert Kennedy and my husband. And, in readiness for reading time with my grandson, “Frog and Toad Are Friends” and “Don’t Let the Pigeon Drive the Bus!”

How do you organize your books?

I’ve come to realize my books organize me more than I organize them! Every book I’ve written has required its own library. Before I knew it, I had amassed full-blown libraries, including fiction as well as nonfiction, for Lincoln, the Civil War, Theodore Roosevelt, the muckraker journalists, F.D.R., World War II and the 1960s. I even built an extended alcove to hold baseball books and memorabilia. Not to mention my husband’s extensive library of plays, poetry, science and philosophy. Books took over every room of the house Dick and I shared in Concord, Mass., as they do now in my Boston home.

What books would people be surprised to find on your shelves?

Stacks and stacks of mystery and detective stories. As W.H. Auden wrote, “The reading of detective stories is an addiction like tobacco or alcohol.”

Did spending so much time with your husband’s letters and journals influence your beliefs about how history gets told?

Too often, history is told and remembered with the knowledge of how events turned out. For 50 years, Dick had resisted opening the 300 boxes he had saved, a time capsule of the 1960s. The ending of the decade — the Vietnam War, the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Dick’s close friend Robert Kennedy, the riots, the violence on college campuses — had cast a dark curtain on the entire era for him and the country.

But when Dick turned 80 and we finally opened the boxes in chronological order, what struck both of us were not the tremendous sorrows of the time, but the exhilarating convictions that individuals could make a difference. This was the impulse that led tens of thousands of young people to join the Peace Corps, participate in sit-ins, freedom rides, marches against segregation and the denial of the vote.

Reading all that alongside him must have been head-spinning.

I‘ve often called the subjects of my books — Abraham Lincoln and both Roosevelts — “my guys,” because I spent decades immersing myself in their letters, diaries and memoirs. I would often talk to them and ask them questions. They never answered. But now, my actual guy, my husband, was sitting across the room from me — arguing, correcting, laughing as he read aloud from his own letters and diaries. Head-spinning for sure!

Which of you was the better writer?

I could never have withstood the pressure and time constraint under which Dick drafted his most important presidential speeches. History is far more patient, far better suited to my slow pace of research and writing. It took me twice as long to unwind the interrelated stories I wanted to tell about the Civil War and World War II as it took those wars to be fought. Dick and I were never in competition. We complemented one another. He was more interested in shaping history, and I in figuring out how history was shaped.

What’s the best book you’ve ever received as a gift?

This past Christmas my son and daughter-in-law, Joe and Veronika, gave me a signed first edition of Barbara Tuchman’s “The Guns of August” — a gift that carried me back to the first time I read the book 60 years ago in college. Here was a woman writing about the field of war traditionally reserved for men. Here was a master storyteller who believed historians must write only what was known by the people at the time, resisting the urge to reference future events.

What’s the most terrifying book you’ve ever read?

“2666,” by Roberto Bolaño.

What do you plan to read next?

James McBride’s “The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store” and Geraldine Brooks’s “Horse.”

You’re organizing a dinner party. Which three storytellers, dead or alive, do you invite?

Lincoln, F.D.R. and L.B.J. I know what they liked to drink and eat. So I would serve water, oyster stew and chicken fricassee with biscuits for Lincoln; martinis and hot dogs with all the fixings for F.D.R.; and Cutty Sark Scotch, chicken fried steak and mashed potatoes for L.B.J. And for once I would keep my mouth shut and listen to three of the most entertaining and enlightening storytellers America has ever produced.

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

Stephen King, who has dominated horror fiction for decades , published his first novel, “Carrie,” in 1974. Margaret Atwood explains the book’s enduring appeal .

The actress Rebel Wilson, known for roles in the “Pitch Perfect” movies, gets vulnerable about her weight loss, sexuality and money in her new memoir.

“City in Ruins” is the third novel in Don Winslow’s Danny Ryan trilogy and, he says, his last book. He’s retiring in part to invest more time into political activism .

Jonathan Haidt, the social psychologist and author of “The Anxious Generation,” is “wildly optimistic” about Gen Z. Here’s why .

Do you want to be a better reader? Here’s some helpful advice to show you how to get the most out of your literary endeavor .

Each week, top authors and critics join the Book Review’s podcast to talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

Advertisement

Breaking News

The week’s bestselling books, April 7

- Show more sharing options

- Copy Link URL Copied!

Hardcover fiction

1. James by Percival Everett (Doubleday: $28) An action-packed reimagining of “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.”

2. The Women by Kristin Hannah (St. Martin’s Press: $30) An intimate portrait of coming of age in a dangerous time and an epic tale of a nation divided.

3. The Hunter by Tana French (Viking: $32) A taut tale of retribution and family set in the Irish countryside.

4. The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store by James McBride (Riverhead: $28) The discovery of a skeleton in Pottstown, Pa., opens out to a story of integration and community.

5. Wandering Stars by Tommy Orange (Knopf: $29) Three generations of a family trace the legacy of the Sand Creek Massacre of 1864 and the Carlisle Indian Industrial School.

6. Until August by Gabriel García Márquez, Anne McLean (Transl.) (Knopf: $22) The Nobel Prize winner’s rediscovered novel is a tale of female desire and abandon.

7. North Woods by Daniel Mason (Random House: $28) A sweeping historical tale focused on a single house in the New England woods.

8. Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin (Knopf: $28) Lifelong BFFs collaborate on a wildly successful video game.

9. Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar (Knopf: $28) An orphaned son of Iranian immigrants embarks on a search for a family secret.

10. Expiration Dates by Rebecca Serle (Atria Books: $27) A heartbreaking novel about what it means to be single, what it means to find love, and ultimately how we define each of them for ourselves.

Hardcover nonfiction

1. The Creative Act by Rick Rubin (Penguin: $32) The music producer’s guidance on how to be a creative person.

2. Atomic Habits by James Clear (Avery: $27) An expert guide to building good habits and breaking bad ones via tiny changes.