The New Generation: Understanding Millennials and Gen Z

17 Pages Posted: 1 Mar 2024

Dr. Priyanka Wandhe

Rashtrasant Tukdoji Maharaj Nagpur University

Date Written: January 31, 2024

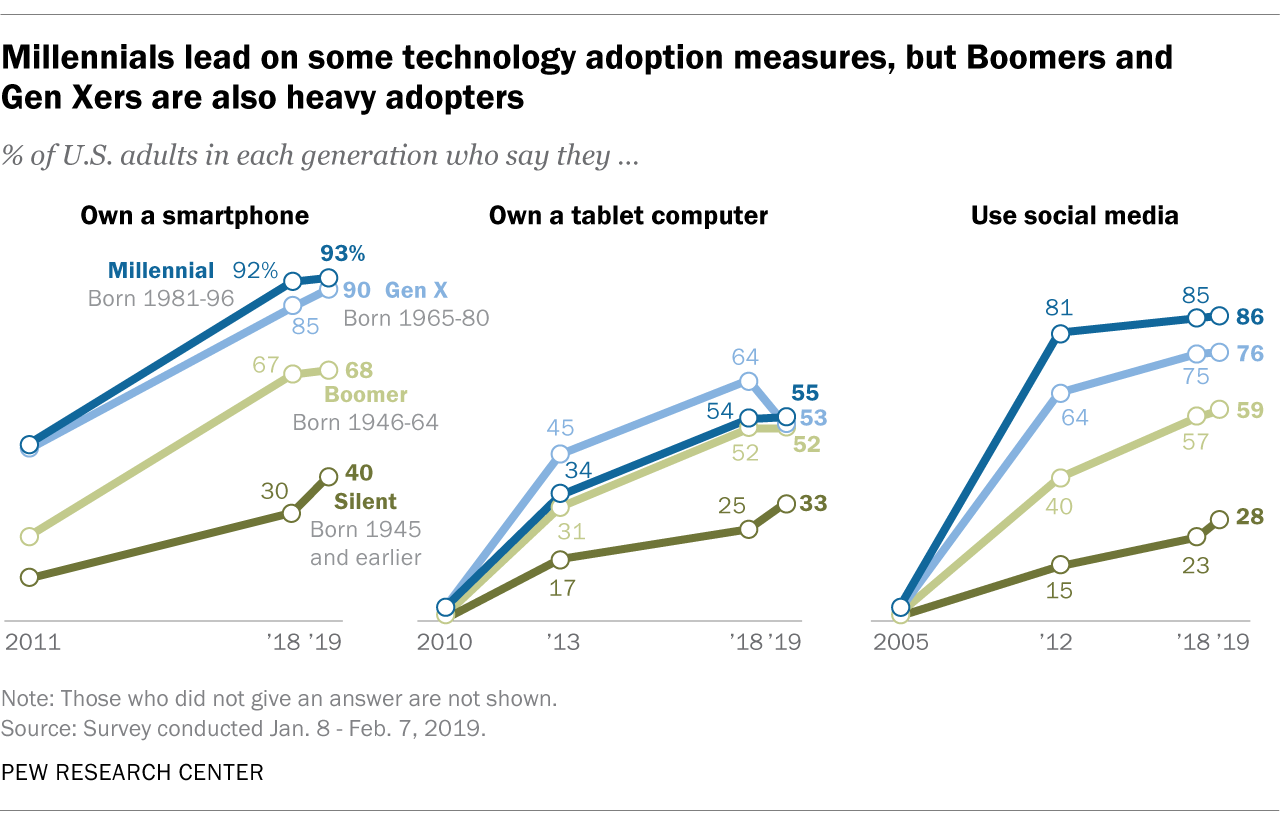

The millennial and Gen Z generations, often referred to as the "new generation," are significantly shaping the social, economic, and cultural landscape of today's society. These abstract aims to provide an understanding of these demographic groups, examining their characteristics, behaviour, values, and aspirations. Millennials represent the first digital-native generation. They grew up with rapid advances in technology, such as the widespread adoption of the internet and the proliferation of social media platforms. This has led to an increased reliance on digital communication and connectivity, promoting globalization and breaking down barriers of distance and culture. Gen Z are the epitome of the digital age. They have never experienced a world without smartphones, social media, or instantaneous access to information. As a result, they are highly adept at navigating online platforms and are early adopters of emerging technologies. This generation values authenticity, diversity, and inclusivity, which has influenced the way they interact with brands, consume media, and participate in online communities. Both millennials and Gen Z are highly influential in shaping consumer trends and preferences. They prioritize experiences over material possessions, opting for meaningful and socially conscious products and services. Sustainability, ethical practices, and corporate social responsibility are important factors when making purchasing decisions. Furthermore, both generations place a strong emphasis on work-life balance and value jobs that offer flexibility, purpose, and personal growth. Traditional hierarchical structures are less appealing to them, as they seek a more collaborative and inclusive work environment. Understanding the motivations and behaviours of millennials and Gen Z is essential for businesses, policymakers, and marketers to effectively engage with these demographics. This research helps identify new strategies and approaches to cater to their evolving needs and preferences. Thus, by acknowledging their unique characteristics, businesses and institutions can adapt their strategies to effectively engage with the new generation and ensure future success.

Keywords: Millennials, Generation Y, Gen Z, Digital natives, Tech-savvy, social media, Self-expression, Diversity, Entrepreneurship, Work-life balance, Sustainability, Social justice, Authenticity, Flexibility, Personalization, Instant gratification, Collaboration, Empathy, Multitasking Globalization

JEL Classification: A00, A10, I20, M00, M10, M30, M31, M37

Suggested Citation: Suggested Citation

Dr. Priyanka Wandhe (Contact Author)

Rashtrasant tukdoji maharaj nagpur university ( email ).

Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Administrative Premises Ravindranath Tagore Marg Nagpur, Maharashtra 440001 India

Do you have a job opening that you would like to promote on SSRN?

Paper statistics, related ejournals, sustainable technology ejournal.

Subscribe to this fee journal for more curated articles on this topic

Humanistic Management eJournal

Subscribe to this free journal for more curated articles on this topic

Educational Psychology & Cognition eJournal

Educational technology, media & library science ejournal, teacher education ejournal, advertising, marketing & strategic communication ejournal, decision-making & management science ejournal, communication & technology ejournal, decision science education ejournal, educational & instructional communication ejournal, educational impact & evaluation research ejournal, interpersonal communication ejournal, communication education ejournal, communication across the lifespan ejournal.

Millennials and Post Millennials: A Systematic Literature Review

- Published: 08 February 2021

- Volume 37 , pages 99–116, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Karuna Prakash 1 &

- Prakash Tiwari 1

2226 Accesses

5 Citations

Explore all metrics

The purpose of the study is to investigate into the research conducted on two young generations i.e. the millennial generation and the post millennial generation in the subject field of business and management. The study takes into account the research conducted from 2010 to 2020 from the Scopus database. Bibliometric analysis is adopted to determine the progress on the study of millennials and post millennials, while identifying the most productive authors, institutions and countries. The results depict a concentration of these studies in developed markets like the USA, Australia, Canada and United Kingdom. India and China are also not too far behind in their contributions. There was seen a dearth in research in emerging markets, which is essential and creates a need for further research to be conducted across different geographical locations. The study contributes to the existing field of knowledge on millennials and post millennials.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or Ebook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Source : Figure is extracted using VOSviewer

Similar content being viewed by others

Reviews and directions of FinTech research: bibliometric–content analysis approach

Running up that hill: a literature review and research agenda proposal on “gazelles” firms

Research Productivity in Economics and Business Disciplines in Emerging Economies: Insights from Kazakhstan

Bascha. (2011). Z: The open source generation. Retrieved from http://opensource.com/business/11/9/z-open-source-generation

Bennett MM, Beehr TA, Ivanitskaya LV. Work-family conflict: differences across generations and life cycles. J Manag Psychol. 2017;32(4):314–32. https://doi.org/10.1108/jmp-06-2016-0192 .

Article Google Scholar

Bolton RN, Parasuraman A, Hoefnagels A, Migchels N, Kabadayi S, Gruber T, et al. Understanding generation Y and their use of social media: a review and research agenda. J Serv Manag. 2013;24(3):245–67. https://doi.org/10.1108/09564231311326987 .

Bulut ZA, Çımrin FK, Doğan O. Gender, generation and sustainable consumption: exploring the behaviour of consumers from Izmir Turkey. Int J Consum Stud. 2017;41(6):597–604. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12371 .

Chen M-H, Chen BH, Chi CG-Q. Socially responsible investment by generation Z: a cross-cultural study of Taiwanese and American investors. J Hosp Market Manag. 2019;28(3):334–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2019.1525690 .

Chuah SH-W, Marimuthu M, Kandampully J, Bilgihan A. What drives Gen Y loyalty? Understanding the mediated moderating roles of switching costs and alternative attractiveness in the value-satisfaction-loyalty chain. J Retail Consum Serv. 2017;36:124–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2017.01.010 .

Cucina JM, Byle KA, Martin NR, Peyton ST, Gast IF. Generational differences in workplace attitudes and job satisfaction: lack of sizable differences across cohorts. J Manag Psychol. 2018;33(3):246–64. https://doi.org/10.1108/jmp-03-2017-0115 .

Culpin V, Millar C, Peters K. Multi-generational frames of reference: managerial challenges of four social generations in the organization. J Manag Psychol. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-08-2014-0231 .

Deal JJ, Altman DG, Rogelberg SG. Millennials at work: what we know and what we need to do (if anything). J Bus Psychol. 2010;25(2):191–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-010-9177-2 .

Deloitte (2019) The Deloitte Global Millennial Survey 2019: societal discord and technological transformation create a “generation disrupted”

Duque Oliva EJ, Cervera Taulet A, Rodríguez Romero C. A bibliometric analysis of models measuring the concept of perceived quality inproviding internet service. Innovar. 2006;16(28):223–43.

Google Scholar

Ellegaard O, Wallin JA. The bibliometric analysis of scholarly production: how great is the impact? Scientometrics. 2015;105(3):1809–31.

Funches V, Yarber-Allen A, Johnson K. Generational and family structural differences in male attitudes and orientations towards shopping. J Retail Consum Serv. 2017;37:101–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2017.02.016 .

Gomes SB, Deuling JK. Family influence mediates the relation between helicopter-parenting and millennial work attitudes. J Manag Psychol. 2019;34(1):2–17. https://doi.org/10.1108/jmp-12-2017-0450 .

Hernaus T, Vokic NP. Work design for different generational cohorts: determining common and idiosyncratic job characteristics. J Organ Change Manag. 2014;27(4):615–41. https://doi.org/10.1108/jocm-05-2014-0104 .

Hershatter A, Epstein M. Millennials and the world of work: an organization and management perspective. J Bus Psychol. 2010;25(2):211–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-010-9160-y .

Kowske BJ, Rasch R, Wiley J. Millennials’ (lack of) attitude problem: an empirical examination of generational effects on work attitudes. J Bus Psychol. 2010;25(2):265–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-010-9171-8 .

Kultalahti, S., & Viitala, R. (2015). Generation Y–challenging clients for HRM? J Manag Psychol.

Kupperschmidt BR. Multigeneration employees: strategies for effective management. Health Care Manag. 2000;19(1):65–76.

Mannheim K. Essays on the Sociology of Knowledge. London: Routledge and Kegan; 1952.

Milian EZ, Spinola MDM, de Carvalho MM. Fintechs: a literature review and research agenda. Electron Commer Res Appl. 2019;34:100833.

Ng ESW, Schweitzer L, Lyons ST. New generation, great expectations: a field study of the millennial generation. J Bus Psychol. 2010;25(2):281–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-010-9159-4 .

Park S, Park S. Exploring the generation gap in the workplace in South Korea. Human Resour Dev Int. 2018;21(3):276–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2017.13067

Pew Research Center. (2018). More than a third of the workforce are Millennials. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/04/11/millennials-largest-generation-us-labor-force/ft_18-04-02_genworkforcerevised_bars1

Rentz KC. Beyond the generational stereotypes: a study of U.S. Generation Y employees in context. Bus Commun Quart. 2014; 77(4):136–66.

Rodriguez M, Boyer S, Fleming D, Cohen S. Managing the next generation of sales, GenZ/Millennial Cusp: an exploration of grit, entrepreneurship, and loyalty. J Businessto-Business Market. 2019;26(1):43–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/1051712X.2019.1565136 .

Scopus, (2019). https://www.elsevier.com/en-gb/solutions/scopus

Tulgan, B. Meet Generation Z: the second generation within the giant" Millennial" cohort. Rainmaker Thinking. 2013; 125.

Twenge JM. A review of the empirical evidence on generational differences in work attitudes. J Bus Psychol. 2010;25(2):201–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-010-9165-6 .

Twenge JM, Campbell SM, Hoffman BJ, Lance CE. Generational differences in work values: leisure and extrinsic values increasing, social and intrinsic values decreasing. J Manag. 2010;36(5):1117–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309352246 .

Van Raan AFJ. Advances in bibliometric analysis: Research performance assessment and science mapping. Dordretch: Portland Press; 2014.

Ward S. Consumer socialization. J Consum Res. 1974;1(2):1–14.

Xiang Z, Tussyadiah I, Buhalis D. Smart destinations: foundations, analytics, and applications. J Destination Market Manag. 2015;4(3):143–4.

Zabel KL, Biermeier-Hanson BBJ, Baltes BB, Early BJ, Shepard A. Generational differences in work ethic: fact or fiction. J Bus Psychol. 2017;32(3):301–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-016-9466-5 .

Zupic I, Čater T. Bibliometric methods in management and organization. Organ Res Methods. 2015;18(3):429–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428114562629 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Management Studies, DIT University, Dehradun, Uttarakhand, India

Karuna Prakash & Prakash Tiwari

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Karuna Prakash .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Prakash, K., Tiwari, P. Millennials and Post Millennials: A Systematic Literature Review. Pub Res Q 37 , 99–116 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12109-021-09794-w

Download citation

Accepted : 26 January 2021

Published : 08 February 2021

Issue Date : March 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s12109-021-09794-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Millennials

- Post millennials

- Bibliometric analysis

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Making generational differences work: What empirical research reveals about leading millennials

Generational differences – reality versus rumor

The topic of generational differences is one that never seems to go away. There has always been a certain amount of narrative and debate about what the differences are and how they influence organizational dynamics. Yet it is important to bear in mind that generational categories are somewhat arbitrary social constructs and that shifting patterns of motivation and behavior are a natural function of a world that itself is changing rapidly. Furthermore, people’s notion of any given generation is based on stereotyping, subjective perception and untested assumptions.

Millennials, aka Generation Y, are the fastest-growing organizational population globally. Yet how much do business leaders understand about them beyond general perceptions, and what are these perceptions based upon? Are there any empirical data to validate or challenge these assumptions?

One thing is certain – the environment in which people grow up influences their expectations and behavioral norms and, consequently, how they categorize and interpret the behaviors of others. People tend to measure performance relative to their own expectations, and this alone is an important consideration when evaluating generational differences.

In an attempt to provide more factual, specific and measurable information on the topic, Management Research Group conducted a global study of generational differences involving over 23,000 leaders across Europe, North America and Asia- Pacific. The aim of the study was to move beyond the general mythology of generational differences and to identify the exact ways in which motivational characteristics vary.

Research methodology

A total of 23,298 leaders completed the Individual Directions InventoryTM (IDI) assessment. The IDI is an expert psychometric assessment that measures 17 underlying and intrinsic motivational characteristics using a sophisticated semi-ipsative normative questionnaire design. This article presents the findings within Europe (n=9,450) across four generations:

Baby Boomers – mid-1940s to mid-’60s (n=3,263)

Gen X – mid-’60s to late ’70s (n=4,623)

Gen Y – early ’80s to early ’90s (n=1,472)

Gen Z – early ’90s to date (n=92)

The median value of each generation in the 17 motivational scales was calculated and plotted on a line graph. For the purposes of comparability, the data in each of the three global regions were compared against the General European norm (n=5,678). The 17 drivers measured in the IDI are organized into thematic groups (Affiliating, Attracting, Perceiving, etc.) to make it easier to understand key facets of the motivational profile.

There are a few caveats when dealing with generational differences. The research identifies the ways in which the motivation of Millennials varies from that of other generations. But people evolve as they learn and mature, so leaders need to be careful not to create a fixed concept of Millennials upon which important organizational decisions might be based. How different will they be 10 years from now? There is also a degree of variance within the Millennial population (as with other generations), so there will always be a need for some calibration in the way individuals are managed.

Understanding motivational DNA

Before examining the findings of this research, it is important to understand what these data are measuring. In this case, they are measuring intrinsic motivation – that is, the areas in which people derive an internal feeling of satisfaction and personal fulfillment. These characteristics originate from a person’s early years, the first 10 to 12 years being highly influential in shaping their unique motivational profile. Motivation does, however, evolve slowly over time; what people find personally rewarding and fulfilling in their early 20s compared with their 50s is likely to be different in some ways. Life experience, personal growth and broader perspective, among other factors, inevitably contribute to changes in what people find emotionally satisfying as they age.

It is important to note that this research does not measure behavior, so the findings do not describe what different generations do. This is interesting insofar as the only thing that can be observed about others is their behavior, but how much of their behavior reflects them intrinsically, and how much of it reflects the way they adapt to different environments? By measuring intrinsic motivation, the research is getting much closer to the truth of the individual, and in so doing measuring characteristics that are more stable over time and likely to reflect the person more than their context.

Baby Boomers and Gen X (mid-1940s to late 1970s)

Depending on how these generations are defined, together they cover a period from the mid-1940s to the late 1970s, a significant period of time in itself but all the more noteworthy when the degree of social, political and technological change is considered.

The pattern of distribution in Figure 1 clearly indicates that there are relatively minor differences between the median values in intrinsic motivation between Baby Boomers and Gen X. This is perhaps a little surprising considering both the span of time that these generations cover and the degree of change in world affairs. It suggests that it potentially takes a lot to change motivational DNA, or at least that the factors that really influence motivational drivers were not necessarily experienced during this period.

Figure 1: Individual Directions Inventory for Baby Boomers and Gen X

Millennials or Generation Y (early 1980s to early 1990s)

Much has been written about the Millennial generation, not all of it complementary. Time magazine in May 2013 described Millennials as “lazy, entitled narcissists who live with their parents.” While the content of the article was in fact reasonably balanced, in general there seems to be more focus on the negatives than on the positives. It is worth remembering that newer generations are simply different from those that preceded them; whether that makes them better or worse is a matter of opinion.

Millennials have lived through an era of phenomenal technological growth, including the emergence of the internet and social media. Like Generation Z, they have witnessed the relentlessness of global terrorism and unprecedented economic turmoil. The world is an uncertain, informationally overloaded, fast- moving place. Some countries in particular (e.g. Spain, Greece and Italy) are still experiencing the economic repercussions of the global credit crisis; how might this influence the core drivers of those who have grown up in such an environment?

Figure 2 shows key differences between Millennials and their predecessors, bearing in mind that the graph measures motivational DNA, not behavioral characteristics. Millennials have higher expectations of achievement (Excelling), bringing a greater sense of urgency to accelerated growth and career progression. Interestingly, there is strong evidence to suggest less originality in this generation than the stereotype might suggest. For example, Millennials are more motivated by a world that is safe and predictable (Stability) and less by environments that require them to innovate and to think in more lateral terms (Creating). This flies in the face of many preconceptions about this newer generation, particularly considering their immersion in new technology. But are they truly the originators, or merely the consumers of innovation?

Figure 2: Individual Directions Inventory for Baby Boomers, Gen X and Millennnials

The elevated median score on the Structuring scale is the most dramatic feature. This scale measures the extent to which the individual enjoys working in a manner that is meticulous, precise and systematic. It also indicates that more clarity about process and “how to” is critical for this generation, and that there might be the first signs of more compulsive tendencies emanating from this underlying motivational characteristic. The graph also indicates less enjoyment from assuming command (Controlling) or from working in a more autonomous, self-reliant manner (Independence). These point strongly toward a preference for more democratic, inclusive decision-making processes and a facilitative approach to leadership.

Motivational measures in themselves describe what people find personally satisfying and rewarding, so they can appear to be a very positive type of construct. But motivational drivers can easily conflict with each other, and often do. For example, some people are motivated by success and security at the same time, so the desire to achieve comes with an elevated fear of failure. This newer generation wants significant achievement (Excelling) with less inherent risk (Stability), and wants to do so in a manner that requires less self-sufficiency (Independence). Previous generations, particularly those whose work ethic revolves around “serving one’s time” and earning the right to be successful, might not appreciate these characteristics.

Practical steps for working with Millennials

Comparatively speaking, Millennials have a more significant informational need than their predecessors. They clearly like to be kept in the loop, finding an ongoing flow of information reassuring as well as informative . They also like to understand the “how to,” reflecting their need for others to be granular and specific in their instructions. They are likely to feel uncomfortable in “last-minute” scenarios, preferring some degree of advance notice to an extent that might be underestimated by others. If previous generations are unaware of these variances, it makes it more difficult for them to make good behavioral choices and to calibrate the ways in which they keep newer generations informed (and vice versa).

The same approach can be applied to other themes such as expectations and sensitivities in relationships. For example, Millennials (and Gen Z even more so) are more likely to be sensitive to situations in which they feel unsupported (Receiving). Newer generations also appear to manifest a greater degree of caution (higher on Stability and Structuring, lower on Creating), which suggests that they will be more comfortable driving innovation when they can do so collectively and with input and validation from others.

This research, especially the empirical measurement that it is based upon, provides practical insights and objective evidence about how to lead, manage and motivate employees across generations. Leaders would do well to act on the following guidelines:

- Be aware that a faster pace of progression and learning is important. Millennials have very high expectations of achievement, both in extent and pace. Establishing a clear career path, developmental stages and criteria for progression helps in this process. Be tangible and specific, not conceptual.

- Foster a more inclusive and democratic environment. Newer generations work best when they collaborate and exchange information and ideas continually. They are likely to feel less secure when they have to work autonomously, and may hold off making a decision until they have satisfied their higher level of informational needs.

- Avoid a “command and control” approach to leadership – it doesn’t work. A more facilitative style is more likely to coax the best out of Millennials; they are a highly motivated group so there is a great deal of positive energy to tap into. Delegate ownership, not just task. Keep a supportive eye on progress and provide ongoing feedback. Develop your “leader as mentor/coach” skills.

- Set clear expectations from the outset. Providing context, explaining method and defining objectives will make a positive difference. As before, be tangible and specific, not conceptual. Leave the door open to allow Millennials to double-check things as they execute.

- Provide ongoing support. Although previous generations might interpret supervision as micromanagement, Millennials are more likely to interpret it as support . They also expect more immediate access to information and support. They might feel more comfortable finding out for themselves if they can use a technology platform to support their learning or to provide immediate access to critical information.

- Develop an understanding of motivational characteristics. By being aware of their own expectations and biases and using a methodical approach to measuring motivation, leaders can try to bring the best out in others irrespective of their generational origin.

Looking ahead to Generation Z (early 1990s to date)

The changing patterns of motivation described above are intriguing in themselves, but are they one-off variances, or do they represent a specific trajectory that continues into the post-Millennial generation? Generation Z represents a much smaller population, both in this research study and in organizations in general, but it is worth including, if only to see where the motivational direction is heading.

The purple line in Figure 3 represents Generation Z; these findings are quite extraordinary and provide an early indication that the variance observed between Millennials and previous generations is not simply random. Something more fundamental is changing in motivational dynamics. What the causal factors are remains an open question; these results, particularly their consistency, are unlikely to be arbitrary. Therefore, a reasonable assumption is that something is happening environmentally that is propagating an unprecedented degree of change in motivational drivers. Hence the need for leaders to keep the focus on understanding generational differences and to adopt a more nuanced and thoughtful leadership style in the quest to enhance the performance of both individuals and the organization.

Figure 3: Individual Directions Inventory for Baby Boomers, Gen X, Millennnials and Gen Z

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

The world’s most famous referee Pierluigi Collina shares his insights into how to make decision making under pressure

Growing numbers of executives are stuck in survival mode – and risking exhaustion. IMD's Susan Goldsworthy reflects on how CHROs can work with seni...

There is much that organizations can learn from artists and designers, from turning ideas into innovation to creative problem-solving and better de...

With the pressure to innovate only growing, along with the epidemic of digital distractions, our experts offer a mindful leader’s toolkit packed wi...

Case (B) explains the contents of the Holder report, which investigated the diversity, equity and inclusion culture at Uber and ends with Travis Ka...

Case (C) discusses the meeting that showcased the proposed actions following the Holder report recommendations and highlights the concerning respon...

This is a fascinating case about Adam Neumann’s problematic behavior, which led to the downfall of WeWork, once one of America’s most valued startu...

The case study examines recent aviation safety concerns at Boeing, focusing on manufacturing issues, leadership decisions and regulatory oversight....

Case (A) recounts Travis Kalanick’s journey through the growth of Uber, highlighting instances of his problematic behavior and the board’s lack of ...

Margherita Della Valle tells IMD President Jean-François Manzoni how she is delivering radical change to reenergize Vodafone and paving the way for...

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Innov Aging

Millennials and Their Parents: Implications of the New Young Adulthood for Midlife Adults

Karen l fingerman.

Department of Human Development and Family Sciences, The University of Texas at Austin

The period of young adulthood has transformed dramatically over the past few decades. Today, scholars refer to “emerging adulthood” and “transitions to adulthood” to describe adults in their 20s. Prolonged youth has brought concomitant prolonged parenthood. This article addresses 3 areas of change in parent/child ties, increased (a) contact between generations, (b) support from parents to grown children as well as coresidence and (c) affection between the generations. We apply the Multidimensional Intergenerational Support Model (MISM) to explain these changes, considering societal (e.g., economic, technological), cultural, family demographic (e.g., fertility, stepparenting), relationship, and psychological (normative beliefs, affection) factors. Several theoretical perspectives (e.g., life course theory, family systems theory) suggest that these changes may have implications for the midlife parents’ well-being. For example, parents may incur deleterious effects from (a) grown children’s problems or (b) their own normative beliefs that offspring should be independent. Parents may benefit via opportunities for generativity with young adult offspring. Furthermore, current patterns may affect future parental aging. As parents incur declines of late life, they may be able to turn to caregivers with whom they have intimate bonds. Alternately, parents may be less able to obtain such care due to demographic changes involving grown children raising their own children later or who have never fully launched. It is important to consider shifts in the nature of young adulthood to prepare for midlife parents’ future aging.

Translational Significance

Clinicians will be able to help normalize situations when midlife parents are upset due to involvement with their young adult children. Policy makers may be able to foresee and plan for future issues involving aging parents and midlife children.

Young adulthood has changed dramatically since the middle of the 20th century. Research over the past two decades has documented this restructuring, relabeling the late teens and 20s under the auspices of “transitions to adulthood” or “emerging adulthood” ( Arnett, 2000 ; Furstenberg, 2010 ). As such, the life stage from ages 18 to 30 has shifted from being clearly ensconced in adulthood, to an interim period marked by considerable heterogeneity. Historically, young people also took circuitous paths in their careers and love interests ( Keniston, 1970 ; Mintz, 2015 ), but a recent U.S. Census report shows that young people today are less likely to achieve traditional markers of adulthood such as completion of education, marriage, moving out of the parental home or securing a job with a livable wage as they did in the mid to late twentieth century ( Vespa, 2017 ). Individuals who achieve such markers do so at later ages, and patterns vary by socioeconomic background ( Furstenberg, 2010 ).

Much of the research regarding this stage of life has focused on antecedents of young adult pathways or implications of different transitions for the young adults’ well-being ( Schulenberg & Schoon, 2012 ). Yet, the prolongation of entry into adulthood involves a concomitant prolongation of midlife parenthood; implications of parenting young adult offspring remain poorly understood. This article focuses on midlife parents’ involvement with grown children from the parents’ perspective (and does not address implications for grown children).

Several theoretical perspectives suggest that parents will be affected by changes in the nature of young adulthood. The life course theory concept “linked lives” suggests that events in one party’s life influence their close relationship partners’ lives. Family systems theory posits that changes in one family member’s life circumstances will reverberate throughout the family, even when children are grown ( Fingerman & Bermann, 2000 ). Further, the developmental stake hypothesis suggests that parents’ high investment and involvement with young adult children may generate both a current and a longer term impact on parental well-being ( Birditt, Hartnett, Fingerman, Zarit, & Antonucci, 2015 ). These theories collectively suggest that events in young adults’ lives may reverberate through their parents’ lives.

As such, this article addresses changes that midlife parents experience stemming from shifts in young adulthood. Specifically it describes (a) what has changed in ties between midlife parents and young adults over the past two decades, (b) why these changes have occurred, and (c) the implications of these changes for parents’ well-being currently in midlife, and in the future if they incur physical declines, cognitive deficits, or social losses associated with late life.

What Has Changed in Parents’ Ties to Young Adults

Parental involvement with young adult children has increased dramatically over the past few decades. Notably, there has been an increase in parents’ contact with, support of, coresidence, and intimacy with young adult children ( Arnett & Schwab, 2012a ; Fingerman, 2016 ; Fingerman, Miller, Birditt, & Zarit, 2009 ; Fry, 2016 ; Johnson, 2013 ).

Parental Contact With Young Adult Children

Parents have more frequent contact with their young adult children than was the case thirty years ago. Research using national US data from the mid to late twentieth century revealed that only half of parents reported contact with a grown child at least once a week ( Fingerman, Cheng, Tighe, Birditt, & Zarit, 2012 ). Because most parents have more than one grown child, by inference many grown children had even less frequent contact with their parents. Recent studies in the twenty-first century, however, found that nearly all parents had contact with a grown child in the past week, and over half of parents had contact with a grown child everyday ( Arnett & Schwab, 2012b ; Fingerman, et al., 2016 ).

It would be remiss to imply that all midlife parents have frequent contact with their grown children, however, because a small group shows the opposite trend. From the child’s perspective, national data reveal 20% of young adults lack contact with a father, and 6.5% lack contact with a mother figure in the United States ( Hartnett, Fingerman, & Birditt, 2017 ). Similarly, research examining Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) young adults suggests that some parents reject grown children who declare a minority sexuality or gender identity, but this appears to be a relatively rare occurrence. Instead, a representative survey found that LGBT young adults choose whether to come out to parents; only 56% had told their mother and only 39% had told their father ( Pew Research Center, 2013 ). As such, it seems that LGBT young adults who are likely to be rejected by parents may decide not to tell them about their sexuality. Death accounted for some of the lack of parents (4% of young adults lack a father due to death and 3% lack a mother). Rather, divorce, incarceration, and other factors such as addiction or earlier placement in foster care may account for estrangement from a parent figure ( Hartnett et al., 2017 ). Of course, estrangement may be different from the parents’ perspective. For example, one study of aging mothers found that 11% of aging mothers reported being estranged from one child ( Gilligan, Suitor, & Pillemer, 2015 ), but these mothers rarely reported being estranged from all of their children. Nevertheless, a significant subgroup of parents may be excluded from increased involvement described here for other parents.

Parental Support of Young Adult Children

Parents also give more support to grown children, on average, than parents gave in the recent past. Across social strata, parents provide approximately 10% of their income to young adult children, a shift from the late twentieth century (Kornich & Furstenberg, 2013). From the 1970s through the 1990s, parents spent the most money on children during the teenage years. But since 2000, parents across economic strata have spent the most money on children under age 6 or young adult children over the age of 18 (Kornich & Furstenberg, 2013). Indeed, some scholars have suggested that over a third of the financial costs of parenting occur after children are age 18 ( Mintz, 2015 ).

The amount of financial support parents provide varies by the parents’ and grown child’s SES, however. Parents from higher socioeconomic strata provide more financial assistance to adult children ( Fingerman et al., 2015 ; Grundy, 2005 ). This pattern is not limited to the United States; better off parents invest money in young adult offspring who are pursuing education or who have not yet secured steady employment in most industrialized nations ( Albertini & Kohli, 2012 ; Fingerman et al., 2016 ; Swartz, Kim, Uno, Mortimer, & O’Brien, 2011 ). Yet, this pattern may perpetuate socioeconomic inequalities in the United States, rendering lower SES parents more likely to have lower SES grown children ( Torche, 2015 ).

In addition to financial support, many parents devote time to grown children (e.g., giving practical or emotional support; Fingerman et al., 2009 ). Young people face considerable demands gaining a foothold in the adult world (e.g., education, jobs, evolving romantic ties; Furstenberg, 2010 ). In response, parents may offer adult offspring help by making doctor’s appointments, or giving advice and emotional support at a distance, using phone, video technologies, text messages, or email.

Such nonmaterial support may stem from early life patterns. In early life, parenting has become more time intensive over the past few decades, particularly among upper SES parents ( Bianchi & Milkie, 2010 ). Lower SES parents may work multiple jobs or face constraints (e.g., rigid work hours, multiple shifts) that preclude intensive parenting more typical in upper SES families ( Conger, Conger, & Martin, 2010 ). It is not clear whether such differences in time persist in adulthood.

Rather, the types of nonmaterial support may differ by SES. Research suggests better off parents are more likely to give information and to spend time listening to grown children, and less well-off parents provide more childcare (i.e., for their grandchildren; Fingerman et al., 2015 ; Henretta, Grundy, & Harris, 2002 ). Grown children in better off families are more likely to pursue higher education, and student status is strongly associated with parental support (including time as well as money) throughout the world ( Fingerman et al., 2016 ; Henretta, Wolf, van Voorhis, & Soldo, 2012 ). Yet, less well-off parents are more likely to coreside with a grown child.

Nevertheless, research suggests that across SES strata, midlife parents attempt to support grown children in need. A recent study found that overall, lower SES parents gave as much or more support than upper SES parents, but lower SES young adult children were still likely to receive less support on average (i.e., due to greater needs across multiple family members in lower SES families; Fingerman et al., 2015 ).

Parental Coresidence With Young Adult Children

Coresidence could be conceptualized as a form of support from parents to grown children; grown children who reside with parents save money and may receive advice, food, childcare or other forms of everyday support. In industrialized nations, rates of intergenerational coresidence have risen in the past few decades. In the United States in 2015, intergenerational coresidence became the modal residential pattern for adults aged 18 to 34, surpassing residing with romantic partners for the first time ( Fry, 2015 , 2016 ). Rates of coresidence have increased in many European countries as well in the past 30 years, though rates vary by country. Coresidence is common in Southern European nations (e.g., 73% of adults aged 18 to 34 lived with parents in Italy in 2007), but relatively rare in Nordic nations (e.g., 21% of young adults lived with parents in Finland in 2007). Coresidence rates in Southern European countries evolved from historical patterns, but also reflect an increase over the past 40 years. For example, in Spain in 1977, fewer than half of young adults remained in the parents’ home, but by the early 21st century over two-thirds of young adults did ( Newman, 2011 ). Coresidence appears to be an extension of the increased involvement between adults and parents (as well as reflecting offspring’s economic needs).

Parental Affection, Solidarity, and Ambivalence Towards Young Adult Children

In general, affection between young adults and parents seems to be increasing in the twenty-first century as well. It is not possible to objectively document changes in the strength of emotional bonds due to measurement issues and ceiling effects—most people have reported close ties to parents or grown children across the decades. Still, it seems intergenerational intimacy is on the rise. In the 20th century in Western societies, marriage was the primary tie. Yet, over 15 years ago, Bengtson (2001) speculated that the prominence of multigenerational ties would rise in the 21st century due to changes in family structure (e.g., dissolution of romantic bonds) and longevity (e.g., generations sharing more years together). Bengtson’s predictions seem to be coming to fruition.

Increases in midlife parents’ affection for young adult children would be consistent with a rise in intergenerational solidarity. Intergenerational solidarity theory was developed in the 20th century to explain strengths in intergenerational bonds ( Bengtson, 2001 ; Lowenstein, 2007 ). Solidarity theory is mechanistic in nature, suggesting that positive features of relationships (e.g., contact, support, shared values, affection) co-occur like intertwining gears. In this regard, we might conceptualize the overall increase in parental involvement as increased intergenerational solidarity.

It is less clear whether conflictual or negative aspects of the relationship have changed in the past few decades. It was only towards the end of the 20th century that researchers began to measure ambivalence (mixed feelings) or conflict in this tie ( Fingerman, 2001 ; Luescher & Pillemer, 1998 ; Pillemer et al., 2007 ; Suitor, Gilligan, & Pillemer, 2014 ). As such, it is difficult to track changes in ambivalence across the decades. Nevertheless, one study found that midlife adults experienced greater ambivalence or negative feelings for their young adult children than for their aging parents ( Birditt et al., 2015 ), suggesting the parent/child tie may have shifted towards greater ambivalence in that younger generation.

Indeed, scholars have argued that ambivalence arises when norms are contradictory, such as the norm for autonomy versus the norm of dependence for adult offspring ( Luescher & Pillemer, 1998 ). And as I discuss, norms for autonomy contrast current interdependence in this tie, providing fodder for ambivalence. Moreover, frequent contact provides more opportunity for conflicts to arise ( van Gaalen & Dykstra, 2010 ). Taken together, these trends suggest that intergenerational ambivalence between midlife parents and grown children also may be on the rise.

Why Parent/Offspring Ties Have Changed

The Multidimensional Intergenerational Support Model (MISM) provides a framework to explain behaviors in parent/child ties. The model initially pertained to patterns of exchange between generations, but extends to a broader understanding of increased parental involvement. Drawing on life course theory and other socio-contextual theories, the basic premise of the MISM model is that structural factors (e.g., economy, technology, policy), culture (norms), family structure (e.g., married/remarried), and relationship and individual (e.g., affection, gender) factors coalesce to generate behaviors in intergenerational ties ( Figure 1 .) Likewise, changes in the parent/child tie and the reasons underlying those changes reflect such factors.

Multidimension intergenerational involvement model.

MISM is truly intended as a framework for stipulating the types of factors that contribute to parents’ and grown children’s relationship behaviors rather than a model of causal influences. Scholars interested in ecological contexts of human development have often designated hierarchies or embedding of different types of contexts (e.g., family subsumed in economy; Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006 ; Elder, 1998 ). Intuitively, young adults’ and midlife parents’ relationships do respond to economic factors, with the Great Recession partially instigating the increase in coresidence ( Fry, 2015 ). Yet, economies arise in part from families and culture as well; in Western democracies, policies, and politicians are a reflection of underlying beliefs and values of the people who vote (as post-election dissection of Presidential voting in the United States suggests). As such, I propose that each of these levels—structural (e.g., economy, policy), cultural (beliefs, social position), family (e.g., married parents/single parent), and relationship or individual factors contribute to midlife parents’ involvement with grown children without implying a hierarchy of influence among the factors. As discussed later, a second aspect of Figure 1 pertains to understanding how parent/child involvement is associated with parental well-being.

Societal Shifts Associated With Changes Between Parents and Young Adults

Economic factors.

Economic changes in the past 40 years weigh heavily on the parent/child tie. Young adults’ dependence on parents reflects complexities of gaining an economic foothold in adulthood. The U.S. Census shows that financial independence is rare for young people today. Compared to their mid twentieth century counterparts, young people today are more likely to fall at the bottom of the economic ladder with low wage jobs. In 1975, fewer than 25% of young adults fell in the bottom of the economic ladder (i.e., less than $30,000 a year in 2015 dollars), but by 2016, 41% did ( Vespa, 2017 ).

Further, roughly one in four young adults who live with their parents in the United States (i.e., 32% who live with parents; Fry, 2016 ) are not working or attending school ( Vespa, 2017 ). These 8% of young adults might reside with parents while raising young children of their own. But notably, the rate of young women who were homemakers fell from 43% in 1975 to just 14% in 2016 ( Vespa, 2017 ) and as I discuss later, fertility has also dropped in this age group ( World Bank, 2017a ). Moreover, a large proportion of young adults who live with parents have a disability of some sort (10%; Vespa, 2017 ). Thus, factors other than childrearing such as disability, addiction, or life problems seem more likely to account for the 2.2 million 25–34 year olds residing with parents not engaged in work or education.

Moreover, the shift toward coresidence with parents is not purely economic—one can imagine a society where young people turn to friends, siblings, or early romantic partnership to deal with a tough economy. Thus, other factors also contribute to these patterns.

Public policies

Public policies play a strong role in shaping relationships between adults and parents in European countries, but may play a lesser role in shaping these ties in the United States. In European countries, the government provides health coverage and long-term care, and government investments in older adults result in transfers of wealth to their middle generation progeny ( Kohli, 1999 ). Similar processes occur with regard to midlife parents and young adults in Europe. Differences in programs to support young adults in Nordic countries versus Southern European countries are associated with the type of welfare state; that is, social democratic welfare regimes assist young adults in Nordic countries towards autonomy, whereas conservative continental or familistic welfare regimes encourage greater dependence on families in southern Europe ( Billari, 2004 ). The coresidence patterns described previously conform to the type of regime. As such, patterns of parental involvement in Europe seem to be associated with government programs.

These patterns are less clear in the United States. Indeed, lack of government support for young adults may help explain many aspects of the intensified bonds. For example, as college tuition has increased and state and federal funding of education has decreased, parents have stepped in to provide financial help or co-sign loans for young adult students. When U.S. policies do address young adults, the policies seem to be popular. For example, in 2017, when the U.S. Congress debated repealing the Affordable Care Act (i.e., Obamacare), there was bipartisan support for allowing parents to retain grown children on their health insurance until age 26, even if these young adults were not students. This policy, instigated in 2011, seemed to be a reaction to the greater involvement of parents in supporting young adults rather than a catalyst of such involvement.

Related to economic changes, a global rise in parental support of young adults may partially reflect the prolonged tertiary education that has occurred throughout the world (i.e., rates of college attendance have risen worldwide; OECD, 2016 ). In the United States, in 2016, 40% of adults aged 18–24 were pursuing higher education ( National Center for Education Statistics, 2017 ), the highest rate observed historically. Similarly, in industrialized nations, young adults are more likely to attend college today than in the past (Fingerman, Cheng, et al., 2016 ).

The influence of education on parental involvement has been observed globally. In young adulthood, students receive more parental support than nonstudents ( Bucx, van Wel, & Knijn, 2012 ; Johnson, 2013 ). A study of college students in Korea, Hong Kong, Germany, and the United States revealed that, across nations, parents provided advice, practical help, and emotional support to college students at least once a month ( Fingerman et al., 2016 ). Young people who don’t pursue an education may end up in part time jobs with revolving hours or off hour shifts and may depend on parents for support ( Furstenberg, 2010 ), but students typically receive more parental support ( Henretta et al., 2012 ).

Technology and geographic stability

Recent technologies also have altered the nature of the parent/child bond, allowing more frequent conversations and exchanges of nontangible support (e.g., advice, sharing problems). Beginning in the 1990s, competitive rates for long distance telephone calls facilitated contact between young adults and parents who resided far apart. Since that time, cell phone, text messages, email, and social media have provided almost instantaneous contact at negligible cost, regardless of distance (Cotten, McCollough, & Adams, 2012).

Parents and grown children also may have more opportunities to visit in person. Residential mobility decreased in the United States from the mid-20th century into the 21st century. Data regarding how far young adults reside from their parents in the United States are not readily available. But in 1965, 21% of U.S. adults moved households; mobility declined steadily over the next 40 years and by 2016 had dropped to 11% (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011, 2016). As such, parents and grown children may be more likely to reside in closer geographic proximity. Deregulation of airlines in 1978 in the United States established the basis for airline competition and declining prices in airfare (with concomitant diminished quality of air travel experience), facilitating visits between parents and grown children who reside at longer distances.

Cultural Beliefs Associated With Changes Between Parents and Young Adults

Culture also contributes to the nature of parent/child ties. Parents and grown children harbor values, norms or beliefs about how parents and grown children should behave. Shifts in cultural values have also contributed to increased involvement.

Historical changes in values for parental involvement

The cultural narrative regarding young adults and parents in the United States has shifted over the past few decades. During the 1960s and 1970s, popular media and scholars referred to the “generation gap” involving dissension between midlife parents and young adult children ( Troll, 1972 ). This cultural notion of a gap reflected the younger generation’s separation from the older one during this historical period. For example, in 1960, only 20% of adults aged 18–34 lived with their parents ( Fry, 2016 ). Into the 1970s, 80% of adults were married by the age of 30 ( Vespa, 2017 ). As such, the generations were living apart. Cultural attention to a generation gap reflected the younger generation’s independence from the older generation. Notably, there was not much empirical evidence of generational dissension . And in the 21st century, this conception of separation of generations and intrafamily conflict seems antiquated.

Today’s cultural narrative is consistent with increased intimacy and dependence of the younger generation, while also disparaging this increased parental involvement. Recent media trends and scholarly work in the early 21st century focus on “helicopter parents” who are too involved with their grown children (Fingerman, Cheng, Wesselmann, et al., 2012 ; Luden, 2012 ). Although the concept of the helicopter parent implies intrusiveness, it is also a narrative that reflects increased contact, intimacy, and parental support documented here. The pejorative aspect of the moniker stems from retention of norms endorsing autonomy; the relationships are deemed too close and intimate. Although intrusive parents undoubtedly exist, there is little evidence that intrusive helicopter ties are pervasive (outside small convenience studies of college students). Rather, young adults seem to benefit from parental support in many circumstances (Fingerman, Cheng, Wesselmann, 2012), but to perhaps question their own competency under some circumstances of parental support ( Johnson, 2013 ). Nevertheless, a cultural lag is evident in beliefs about autonomy in young adulthood versus the increased parental involvement. Many midlife parents believe young adults should be more autonomous than they are (Fingerman, Cheng, Wesselmann, et al., 2012 ).

Historical changes in sense of obligation

Shifts in beliefs are notable with regard to a diminished sense of obligation to attend to parent/child ties as well. Obligation has been measured most often with regard to midlife adults’ beliefs concerning help to aging parents (i.e., filial obligation). For example, Gans and Silverstein (2006) examined four waves of data regarding adults’ ties to parents from 1985 to 2000; they documented a trend of declining endorsement of obligation over that period. Similarly, many Asian countries (e.g., China, Korea, Singapore) traditionally followed Confucian ideals involving a high degree of respect and filial piety. But over the past three decades, these values have eroded in these countries ( Kim, Cheng, Zarit, & Fingerman, 2015 ). As such, norms obligating parent/child involvement seem to be waning.

Instead, the strengthened bonds and increased parental involvement may reflect a loosening of mores that govern relationships in general. Scholars have suggested that increased individual freedom and fewer links between work, social activity, and family life characterize modern societies over the past decades. These changes also are associated with evolving family forms (e.g., divorce and stepties) as well as decreased fertility ( Axinn & Yabiku, 2001 ; Lesthaegh, 2010 ). Likewise, this loosening of rules has rendered the parent/child relationship more chosen and voluntary in nature. This is not to say the tie has become reciprocal; parents typically give more to offspring than they receive ( Fingerman et al., 2011 ). Yet, the increased involvement and solidarity may stem from freedom parents and grown children experience to retain strong bonds (rather than following norms of autonomy).

National and ethnic differences in beliefs about parent/child ties

The role of beliefs and values in shaping ties between young adults and parents is evident in cross national differences. High parental involvement occurs most often in cultures where people highly value such involvement. Analysis of European countries has found that in countries where adults and parents coreside more often, adults place a higher value on parental involvement with grown children ( Hank, 2007 ; Newman, 2011 ). For example, families in Southern Europe (Spain, Italy, Greece) coreside most often and also prefer shared daily life. Based on this premise, we would expect to see a surge in norms in the United States endorsing intergenerational bonds and young adults’ dependence on parents, but this is not necessarily the case.

In addition to the cultural lag mentioned previously, within the U.S. ethnic differences in parental beliefs about involvement with young adults are evident. For example, Fingerman, VanderDrift, and colleagues (2011) examined three generations among Black and non-Hispanic White families. Findings revealed that overall, non-Hispanic White midlife adults provided more support of all types to their grown children than to their parents. Black midlife adults also provided more support overall to their grown children than to their parents, but they provided more emotional support, companionship, and practical help to their parents. Importantly, midlife adults’ support to different generations was consistent with ethnic/racial differences in value and beliefs—Black and non-Hispanic adults’ support behaviors were associated with their perceived obligation to help grown children and rated rewards of helping grown children and parents (above and beyond factors such as resources, SES, offspring likelihood of being a student, and familial needs) ( Fingerman, VanderDrift, et al., 2011 ). These findings were consistent with a study conducted in the late 20th century using a national sample of young adults; that study found that racial and immigration status differences in parents’ support of young adults reflected factors in addition to young adult resources, family SES, or other structural factors (Hardie & Selzter, 2016), presumably cultural differences. As such, the overall culture surrounding young adults and family may play a role in increased parental involvement.

Family Factors Associated With Changes Between Parents and Young Adults

Changes in family structure are likely to affect the nature of parent/child relationships, including (a) proportion of mothers married to a grown child’s father, (b) likelihood of a midlife parent having stepchildren, and (c) the grown child’s fertility. Collectively, these family changes contribute to the nature of bonds between young adults and parents, and raise questions about the future of this tie.

Declines in married parents and rise of stepfamilies

Changes in parents’ marital status contribute to relationships with grown children in complex ways. Some changes facilitate the strengthened bonds observed, but other changes diminish the likelihood of a strong bond. As such, while the overall trend shows greater parental involvement, specific groups of midlife parents may have only tenuous or conflicted ties with their grown children.

The previous few decades saw a shift from families where two parents were likely to be married to one another toward single parents and complex family forms. From 1970 to 2010, the marriage rate for women in the United States declined steadily, particularly for Black women (in 2010 only 26% of Black women were married; Cruz, 2013 ). Mothers who raise children alone typically have stronger ties when those children grow into young adults. By contrast, never-married fathers may have little contact and are more likely to be estranged from those children ( Hartnett et al., 2017 ).

Further, midlife adults are more likely to have ties to grown children through remarriage (i.e., stepchildren) than in the past. Divorce rates rose and plateaued in the mid to late twentieth century. Divorce is associated with greater tensions between young adults and parents, particularly for fathers ( Yu, Pettit, Lansford, Dodge, & Bates, 2010 ).

Remarriage rates also continued to rise over the past few decades; 40% of all marriages involve at least one partner who was previously married ( Livingston, 2014 ). A recent survey found 18% of adults in the United States aged 50–64 and 22% of adults over age 65 had a stepchild ( Pew Research Center, 2011 ). Stepparents are less involved with grown stepchildren ( Aquilino, 2006 ) and feel less obligated to help stepchildren than biological/adoptive parents do ( Ganong & Coleman, 2017 ; Pew Research Center, 2011 ). Thus, many midlife adults have ties to grown children that do not involve the intensity of biological relationships. Yet, it is not clear whether these same midlife adults have biological children to whom they remain close.

Young adults’ marriage and fertility

Young adults’ marital and procreation patterns may contribute to more intense bonds with midlife parents. In well-off families, young adults are delaying marriage ( Cherlin, 2010 ). Given that marriage typically draws young adults away from parents ( Sarkisian & Gerstel, 2008 ), this delay may contribute to more intense ties with parents. Upper SES young adults are more likely to marry, but do so at later ages ( Vespa, 2017 ) and thus, also retain stronger ties to parents.

Changes in childbearing also may facilitate prolonged ties to parents. The transition to adulthood co-occurs with the period of highest fecundity, but several factors contribute to diminished fertility since 1960s ( World Bank, 2017a ). Rising levels of women’s education and effective contraception are associated with lower birth rates ( Lesthaegh, 2010 ). Americans no longer believe parenthood is a key marker of adulthood ( Vespa, 2017 ). Further, declines in fertility occur during economic downswings, such as the Great Recession ( Mather, 2012 ).

Declines in fertility lengthen the period of time in which young adult retain child-free ties to parents, and also shape the midlife adults’ transition to grandparenthood. Yet, the likelihood and experience of being a grandparent also differs by socioeconomic position. In lower SES families, young adult women are more likely to become mothers without a long term partner ( Cherlin, 2010 ); their midlife mothers (the grandmothers) may help with childcare, housing, and other support. Further, lower SES midlife parents are more likely to be involved in living with or raising grandchildren (Ellis & Simons, 2014; U.S. Census Bureau, 2014). Thus, a majority of midlife adults remain in limbo with regard to whether and when they will become grandparents and their involvement with their own children reflects a prolongation of prior parental involvement, but a subset of typically under-privileged midlife parents may be highly involved in care for grandchildren.

Relationship and Individual Characteristics Associated With Parent/Child Ties

Finally, ties between midlife adults and their grown children occur between two people, and the characteristics of these people and their shared history account for the nature of those relationships.

History of the relationship

Close relationships in young adulthood may arise from strong relationships in childhood and adolescence. Attachment theory suggests children form bonds to parents in infancy that endure into their relationship patterns in adulthood, and theorists also argue that parents retain bonds to children formed earlier in life ( Antonucci & Akiyama, 1994 ; Kahn & Antonucci, 1980 ). Of course, these assumptions raise questions about what types of relationships are likely to be stronger in childhood and adolescence.

Similar structural, cultural, and family contexts contribute to childhood patterns and to continuity into adulthood. For example, upper socioeconomic status parents are more likely to engage in intensive parenting when their children are young such as playing games with them and ferrying them to soccer practice ( Bianchi & Milkie, 2010 ; Sayer, Bianchi, & Robinson, 2004 ). Likewise, parental marital status plays a role in these patterns, with divorced or single fathers less involved with young children than coresident married fathers ( Kalmijn, 2013a ; Sweeney, 2010 ). Lower socioeconomic mothers may be involved with their children because they are more likely to be never married or divorced. A complete review of the factors that shape ties between young children and parents is beyond the scope of this article, but suffice it to say that the factors that account for ties between young adults and parents also shape ties earlier in the lifespan, and that observed relationships between young adults and parents in part arise from these earlier relationships.

Individual Characteristics and Within Family Differences

In addition, midlife parents bring individual characteristics to their relationships with grown children, including their gender, socioeconomic position, and marital status. Socioeconomic position has already been covered with regard to provision of support, and marital status was reviewed with regard to family structure.

But parental gender also plays a key role, favoring maternal involvement with grown children. The pattern of current maternal involvement is not new; research from the mid twentieth century documented that mothers were consistently more involved than fathers were with grown children of all ages ( Rossi & Rossi, 1990 ; Umberson, 1992 ).

Parental gender is situated in a variety of other contextual variables, including SES (single mothers likely to be poorer, with fewer financial resources for children) and marital status (e.g., unmarried mothers are closer to their grown children, unmarried/remarried fathers have lessened involvement or may be estranged from grown children). Yet, studies find that mothers have more frequent contact with grown children, provide more support, and report greater closeness and conflict at midlife even after controlling for social structure and marital status (e.g., Arnett & Schwab, 2012a ; Fingerman et al., 2009 ; Fingerman et al., 2016 ).

Notably, relationships between young adults and parents also vary within families. That is, parents do not have equally intense relationships with each of their children ( Suitor et al., in press ). Parents respond to their children’s characteristics and their sense of compatibility with each child. Parents provide support in reaction to crises (e.g., divorce, illness) or ongoing everyday needs associated with a child’s statuses (e.g., child is a parent; student) or age ( Hartnett et al., 2017 ). Parents also are more likely to give support to young adult and midlife children whom they view as successful, with whom they have closer relationships, or with whom they share values ( Kalmijn, 2013b ; Suitor, Pillemer, & Sechrist, 2006 ; Suitor et al., 2016 ).

Declining fertility described previously may diminish within-family variability in the future ( World Bank, 2017a ). Today’s midlife adults grew up in larger sibships than today’s young adults, and parents invest more in each child in smaller sibships ( Fingerman et al., 2009 ). As such, the intensity of ties between midlife parents and their grown children is generally higher than in the past, and likely to remain high, with diminishment of within family variability.

Implications of Changes in Young Adulthood for Midlife Parents’ Well-Being

All of these issues raise the question—do changes in parents’ ties to young adults matter for the parents? Theory and research regarding the effects of parental involvement have focused on the grown child (e.g., Johnson, 2013 ) rather than on the parent.

Emerging evidence suggests involvement with young adult offspring has implications for midlife parents’ current well-being, however. The research literature on this topic is nascent, beginning in the past 10 years (perhaps reflecting the increase in parental involvement during that period). Further, most studies examine effects of parental involvement without contextual factors such as SES or marital status. As such, the MIS model ( Figure 1 ) is comprised of two models, one model predicting parental involvement from a variety of factors, and the other model predicting parental well-being from parental involvement. Several of the connections between levels of the model are theoretical and warrant additional research attention. In describing associations between parental involvement and well-being, I highlight which factors might warrant particular research attention in the future.

Generativity and benefits of parental involvement

Midlife parents may benefit from involvement with their grown children. Erikson’s (1963) theory of lifespan development indicated the task of midlife is generativity—that is, midlife adults derive rewards from giving to the next generation. In the context of the parent/child tie, one study found that parents who gave more instrumental support to their grown children reported better well-being (fewer depressive symptoms) over time ( Byers, Levy, Allore, Bruce, & Kasl, 2008 ). Similarly, another study found that parents shared laughter and enjoyable exchanges with grown children in their daily interactions. Over the course of the study week, 90% of the parents ( N = 247) reported having an enjoyable encounter with a grown child, and 89% reported laughing with a grown child ( Fingerman, Kim, Birditt, & Zarit, 2016 ).

Yet, not all parents experience such generativity and enjoyment of grown children. The family factors described previously may play a role in whether parents benefit from, or are harmed by, involvement with grown children. Parents who are estranged from offspring (i.e., fathers) may suffer diminished well-being due to the loss of this normative role. Similarly, stepparents may incur fewer rewards due to lessened involvement with grown children. Future research should focus specifically on opportunities for generativity in different populations, particularly among midlife men.

Further, as mentioned, midlife adults are less likely to be grandparents due to young adults’ delayed fertility (or decisions to not have children). Midlife adults who are grandparents are often highly involved with their grandchildren (as well as their grown children), providing childcare on a frequent basis ( Hank & Buber, 2009 ). Grandparents typically find the grandparenting role rewarding ( Fingerman, 1998 ). Future research should ask whether midlife adults who have grown children, but not grandchildren experience frustration or longing.

Emotional involvement and grown children’s problems

Parental well-being also may align with events in their grown children’s lives. Coregulation of emotions has been found in marital couples and in ties between parents and younger children who live in their home ( Butler & Randall, 2013 ). Likewise, the increased frequency of contact with grown children may generate an immediate emotional response to problems grown children experience. Indeed, factors that have facilitated contact between generations, such as technologies, decreased mobility, and coresidence allow parents to experience immediate reactions to events in grown children’s lives. For example, in the 1980s, a grown child who failed a college exam might call at the end of the week to relate that story to a parent, along with the resolution of the problem (the professor offered extra credit because students did not perform well on that test). The parent learned of the events without reacting emotionally. By contrast, in the 21st century, young adults text or call their parents in the throes of crisis, and parents experience the vicissitudes of young adulthood in the moment.

In particular, midlife parents incur detriments from grown children suffering life crises such as divorce, health problems, job loss, addiction, or being the victim of a crime. Researchers have found that even one grown child experiencing one problem has a negative effect on a midlife parent, regardless of how successful other children in the family might be ( Fingerman, Cheng, Birditt, & Zarit, 2012 ). Similarly, in late life, mothers suffer when grown children experience such crises, irrespective of their favoritism or feelings about the grown child ( Pillemer, Suitor, Riffin, & Gilligan, 2017 ). These effects on parental well-being may reflect a variety of responses including a sense that one has failed in the parenting role, worry about the child, empathy with the grown child, or stress of trying to ameliorate the situation (Fingerman, Cheng, Birditt, et al., 2012 ; Hay, Fingerman, & Lefkowitz, 2008 ). Again, structural factors such as SES are associated with the likelihood parents will have a grown child who experiences such problems. That is, lower SES is associated with increased risks of a grown child experiencing financial and other life problems.

The familial changes noted previously also may play a role regarding which parents are affected by grown children. Stepparents may incur fewer rewards from stepchildren and less harm when their stepchildren suffer problems compared to biological (or adopted early in life) children. Yet, the marriage may suffer if the stepparent objects to the biological parents’ involvement with a grown children who has incurred a life crisis. Future research should address these issues.

In sum, many midlife parents incur benefits from their stronger ties to grown children. But when grown children experience life crises—job loss or serious health problems—these problems may undermine their parents’ well-being, particularly when parents are highly involved with those grown children.

Beliefs About Involvement With Grown Children

Parents’ beliefs about their involvement with grown children may also be pivotal in the implications of that involvement for their well-being. Cognitive behavioral theories suggest that individuals’ perspectives on these relationships determine the implications of involvement with family members. Indeed, research regarding intergenerational caregiving has established that beliefs about the caregiving role and subjective burden contribute to the implications of caregiving more than the objective demands of caregiving ( Aneshensel, Pearlin, Mullan, Zarit, & Whitlatch, 1995 ; Zarit, Reever, & Bach-Peterson, 1980 ).

Similar processes may be evident regarding midlife parents’ involvement with their grown children. It is not so much the involvement, per se, as the parents’ perceptions of that involvement that affects the parents’ well-being. For example, in one study, when midlife parents provided support to grown children several times a week, parents’ ratings of the child’s neediness were associated with parental well-being. Parents who viewed their grown children as more needy than other young adults reported poorer well-being, but the frequency of support the parents provided was not associated with the parents’ well-being (though more frequent support was beneficial from the grown child’s perspective; Fingerman, Cheng, Wesselmann, et al., 2012 ).

Shifts in beliefs and the associations with well-being may reflect both the overall cultural norms for parental involvement and the economy. For example, a study in the United States before the Great Recession (when intergenerational coresidence was less common) found that adults of all ages endorsed coresidence between generations solely when the younger generation incurred economic problems or was single and childless ( Seltzer, Lao, & Bianchi, 2012 ). A more recent study of the “empty nest” found that midlife parents who had children residing in their home in 2008 had poorer quality marital ties. But in 2013 (when intergenerational coresidence became more common), parents residing with offspring reported poorer marital quality only when their children suffered life problems ( Davis, Kim, & Fingerman, in press ). Thus, norms for parental involvement with grown children and the economic context may shape the implications of that involvement for parents’ marital ties and well-being. Parents are harmed when they believe their grown children should be more autonomous (Fingerman, Cheng, Wesselmann, et al., 2012 ; Pillemer et al., 2017 ).

Future Consequences of Today’s Young Adulthood for Parents Entering Late Life