How to Write Learning Goals

Main navigation, learning goals overview.

Specific, measurable goals help you design your course and assess its success. To clearly articulate them, consider these questions to help you determine what you want your students to know and be able to do at the end of your course.

- What are the most important concepts (ideas, methods, theories, approaches, perspectives, and other broad themes of your field, etc.) that students should be able to understand, identify, or define at the end of your course?

- What would constitute a "firm understanding", a "good identification", and so on, and how would you assess this? What lower-level facts or information would students need to have mastered and retained as part of their larger conceptual structuring of the material?

- What questions should your students be able to answer at the end of the course?

- What are the most important skills that students should develop and be able to apply in and after your course (quantitative analysis, problem-solving, close reading, analytical writing, critical thinking, asking questions, knowing how to learn, etc.)?

- How will you help the students build these skills, and how will you help them test their mastery of these skills?

- Do you have any affective goals for the course, such as students developing a love for the field?

A note on terminology: The academy uses a number of possible terms for the concept of learning goals, including course goals, course outcomes, learning outcomes, learning objectives, and more, with fine distinctions among them. With respect for that ongoing discussion, given that the new Stanford course evaluations are focused on assessing learning goals, we will use "learning goals" when discussing what you want your students to be able to do or demonstrate at the end of your class.

A CTL consultant can help you develop your learning goals.

For more information about how learning goals can contribute to your course design, please see Teacher-centered vs. Student-centered course design .

Learning Goal Examples

Examples from Stanford’s office of Institutional Research & Decision Support and syllabi of Stanford faculty members:

Languages and Literature

Students will be able to:

- apply critical terms and methodology in completing a literary analysis following the conventions of standard written English

- locate, apply, and cite effective secondary materials in their own texts

- analyze and interpret texts within the contexts they are written

Foreign language students will be able to:

- demonstrate oral competence with suitable accuracy in pronunciation, vocabulary, and language fluency

- produce written work that is substantive, organized, and grammatically accurate

- accurately read and translate texts in their language of study

Humanities and Fine Arts

- demonstrate fluency with procedures of two-dimensional and three-dimensional art practice

- demonstrate in-depth knowledge of artistic periods used to interpret works of art including the historical, social, and philosophical contexts

- critique and analyze works of art and visual objects

- identify musical elements, take them down at dictation, and perform them at sight

- communicate both orally and in writing about music of all genres and styles in a clear and articulate manner

- perform a variety of memorized songs from a standard of at least two foreign languages

- apply performance theory in the analysis and evaluation of performances and texts

Physical and Biological Sciences

- apply critical thinking and analytical skills to interpreting scientific data sets

- demonstrate written, visual, and/or oral presentation skills to communicate scientific knowledge

- acquire and synthesize scientific information from a variety of sources

- apply techniques and instrumentation to solve problems

Mathematics

- translate problems for treatment within a symbolic system

- articulate the rules that govern a symbolic system

- apply algorithmic techniques to solve problems and obtain valid solutions

- judge the reasonableness of obtained solutions

Social Sciences

- write clearly and persuasively to communicate their scientific ideas clearly

- test hypotheses and draw correct inferences using quantitative analysis

- evaluate theory and critique research within the discipline

Engineering

- explain and demonstrate the role that analysis and modeling play in engineering design and engineering applications more generally

- communicate about systems using mathematical, verbal and visual means

- formulate mathematical models for physical systems by applying relevant conservation laws and assumptions

- choose appropriate probabilistic models for a given problem, using information from observed data and knowledge of the physical system being studied

- choose appropriate methods to solve mathematical models and obtain valid solutions

For more information about learning goals, meet with a CTL consultant .

See more STEM learning goal examples from the Carl Wieman Science Education Initiative .

Key dates for end-term feedback

Check the dates for end-term feedback for the academic year.

Frequently asked questions

Get answers to some common questions.

Key principles of evaluation

Key ideas guiding evaluations and student feedback at Stanford.

- Request a Consultation

- Workshops and Virtual Conversations

- Technical Support

- Course Design and Preparation

- Observation & Feedback

Teaching Resources

Writing Effective Learning Goals

Resource overview.

Tips and resources to help you set learning goals for your course

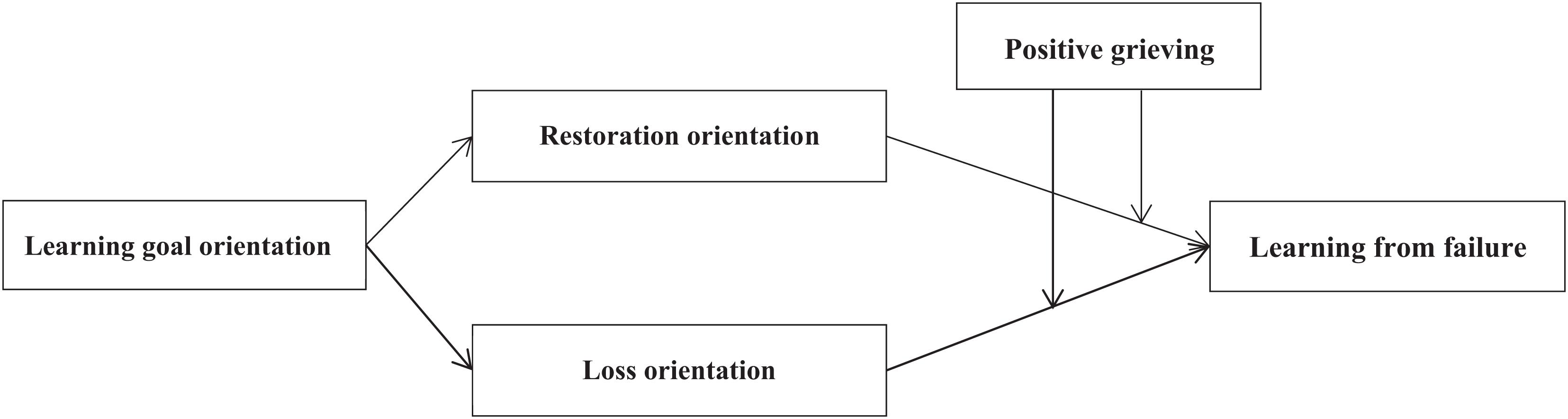

Oftentimes when instructors are developing courses, they start by thinking about a reading list or a list of topics to lecture on. This is considered a forward-thinking process of designing a course. By contrast, Wiggins and McTighe (2005) recommend a backward design approach that encourages you to consider your outcomes (goals) for students first. A learning goal is a statement of what your students should know or be able to do as a result of successfully completing your course.

By clarifying and explicitly stating your learning goals first, you can then design assessments and learning activities that are aligned with those goals. The benefit of following backward design that you can be confident that students who succeed in the course will leave having achieved the goals that you set for them at the beginning.

Identifying Your Learning Goals

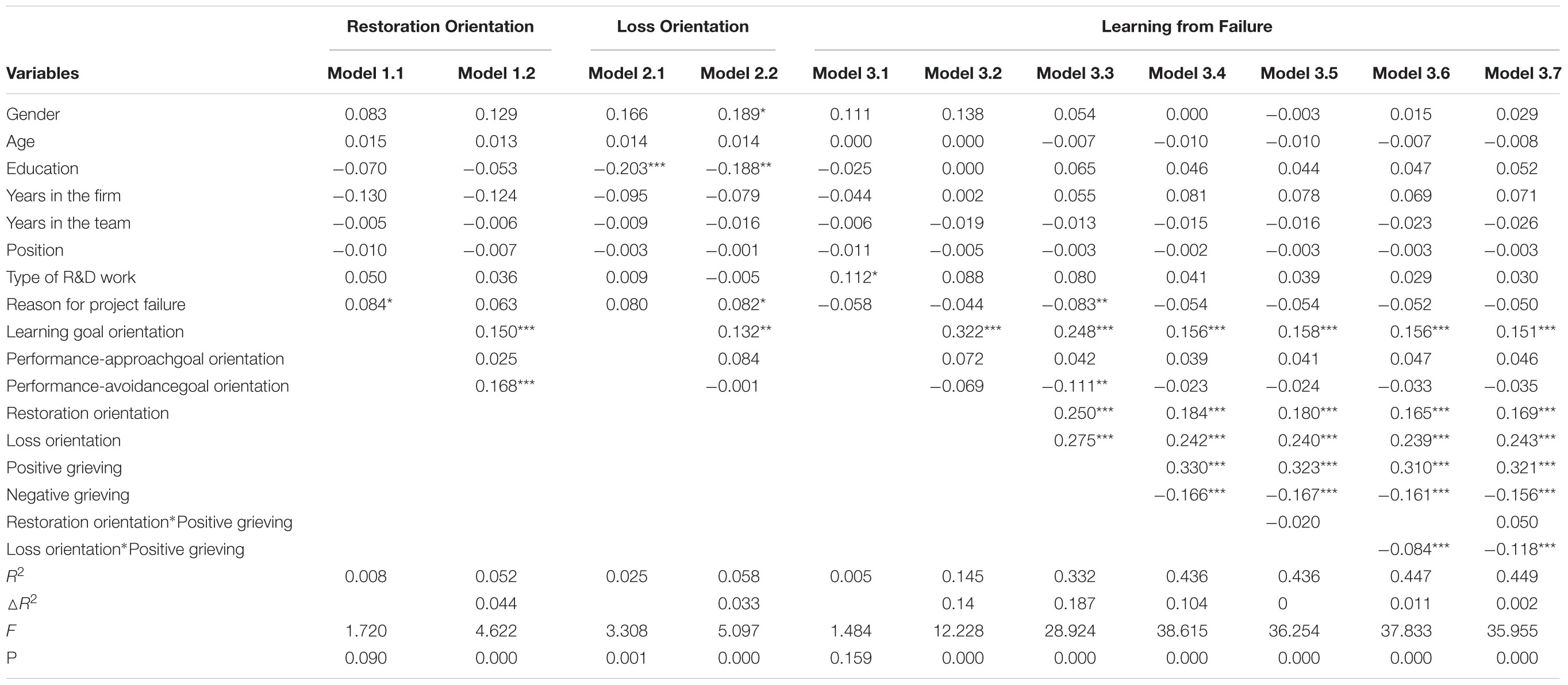

Ideally, learning goals for a course are developed through considering contextual factors, as well as the kinds of knowledge production activities (e.g. synthesis, analysis, comparison, etc.) and skills that you want your students to leave your course comfortable performing. Starting from contextual factors, and considering types of learning on a macro-level, should make it easier to identify specific course-level learning goals for your students. As you are exploring the chart below, consider the relationships among the teaching context, types of learning, and beginning draft of learning goals provided:

What’s the Big Deal about Learning Goals?

So, you might be wondering at this point: what’s the big deal about learning goals? You might even be annoyed if you see learning goals as simply an output of the corporatization of higher education. The truth is however that even if you haven’t used the words “learning goals” before to describe your classes, instructors always have in mind what it is they want their students to get out of a course. And, the best, most meaningful classes for students tend to be those in which that foundational set of goals drives every other decision that is made about the course: What assignments should I ask my students to complete? What should they read or watch? What should we do in class? How should they interact with each other? In short, learning goals can be our compass, can keep us from veering off course in ways that don’t support our students’ learning.

In a time when fancy new technologies and all the other considerations seem overwhelming, learning goals are all the more critical. If you are willing to start from your learning goals, the noise of possibilities will begin to die down, and everything that is truly essential for you to know in order to support your students’ learning will become clearer.

Writing a Learning Goal

As you develop and refine your learning goals for students, you’ll want to make sure they are specific and measurable. It’s critical that the goals that you choose are ones that can be measured–that is, that it would be possible for you to assess how well students have been able to accomplish this goal in your class.

A good way to start drafting a specific learning goal is to identify what you want students to actually do with the knowledge that you hope they will gain in your course. Examining a list of verbs can really be helpful for identifying the specific things that you’d like students to be able to do with knowledge acquired.

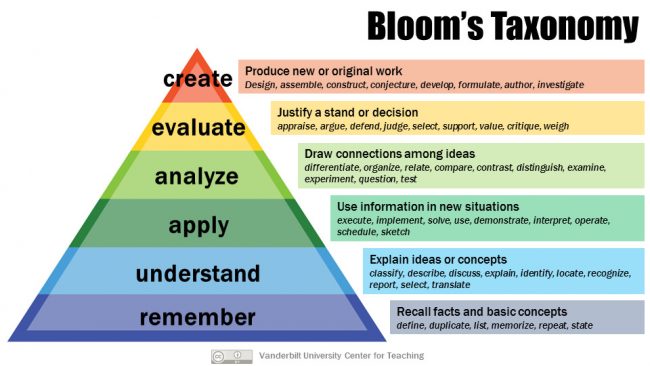

One common way to break down these cognitive activities (what students are “doing”) is Bloom’s (revised) Taxonomy, a hierarchical framework for constructing and classifying learning goals (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001). The revised taxonomy includes the following levels of cognitive engagement: Remember, Understand, Apply, Analyze, Evaluate, and Create. This taxonomy suggests that one isn’t ready to do more complex cognitive tasks (e.g. application, analysis) until one has a firm grasp on the lower-levels (remember, understand).

Traditionally, learning goals are written from the student’s point of view, for example: “The student should be able to trace the carbon cycle in a given ecosystem.”

Click here to see more examples of learning goals.

Characteristics of Effective Learning Goals

It’s relatively easy to write a learning goal, it’s more challenging to write a really effective one! Watch the short video presentation below (~6 minutes) to learn some of the basic principles of effective learning goals.

Further Reading

Nilson, L. (2016). “Outcomes-Centered Course Design” in Teaching at It’s Best , 4th edition. Jossey-Bass.

Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning, Yale University. (2017). Bloom’s Taxonomy .

Fink, L. D. (2005). A Self-Directed Guide to Designing Courses for Significant Learning .

Anderson, L. W. & Krathwohl, D. R. (Eds.). (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing : A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. Longman.

Wiggins, G. & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design . ASCD.

Have suggestions?

If you have suggestions of resources we might add to these pages, please contact us:

[email protected] (314) 935-6810 Mon - Fri, 8:30 a.m. - 5:00 p.m.

Teaching Commons Conference 2024

Join us for the Teaching Commons Conference 2024 – Cultivating Connection. Friday, May 10.

Creating Learning Outcomes

Main navigation.

A learning outcome is a concise description of what students will learn and how that learning will be assessed. Having clearly articulated learning outcomes can make designing a course, assessing student learning progress, and facilitating learning activities easier and more effective. Learning outcomes can also help students regulate their learning and develop effective study strategies.

Defining the terms

Educational research uses a number of terms for this concept, including learning goals, student learning objectives, session outcomes, and more.

In alignment with other Stanford resources, we will use learning outcomes as a general term for what students will learn and how that learning will be assessed. This includes both goals and objectives. We will use learning goals to describe general outcomes for an entire course or program. We will use learning objectives when discussing more focused outcomes for specific lessons or activities.

For example, a learning goal might be “By the end of the course, students will be able to develop coherent literary arguments.”

Whereas a learning objective might be, “By the end of Week 5, students will be able to write a coherent thesis statement supported by at least two pieces of evidence.”

Learning outcomes benefit instructors

Learning outcomes can help instructors in a number of ways by:

- Providing a framework and rationale for making course design decisions about the sequence of topics and instruction, content selection, and so on.

- Communicating to students what they must do to make progress in learning in your course.

- Clarifying your intentions to the teaching team, course guests, and other colleagues.

- Providing a framework for transparent and equitable assessment of student learning.

- Making outcomes concerning values and beliefs, such as dedication to discipline-specific values, more concrete and assessable.

- Making inclusion and belonging explicit and integral to the course design.

Learning outcomes benefit students

Clearly, articulated learning outcomes can also help guide and support students in their own learning by:

- Clearly communicating the range of learning students will be expected to acquire and demonstrate.

- Helping learners concentrate on the areas that they need to develop to progress in the course.

- Helping learners monitor their own progress, reflect on the efficacy of their study strategies, and seek out support or better strategies. (See Promoting Student Metacognition for more on this topic.)

Choosing learning outcomes

When writing learning outcomes to represent the aims and practices of a course or even a discipline, consider:

- What is the big idea that you hope students will still retain from the course even years later?

- What are the most important concepts, ideas, methods, theories, approaches, and perspectives of your field that students should learn?

- What are the most important skills that students should develop and be able to apply in and after your course?

- What would students need to have mastered earlier in the course or program in order to make progress later or in subsequent courses?

- What skills and knowledge would students need if they were to pursue a career in this field or contribute to communities impacted by this field?

- What values, attitudes, and habits of mind and affect would students need if they are to pursue a career in this field or contribute to communities impacted by this field?

- How can the learning outcomes span a wide range of skills that serve students with differing levels of preparation?

- How can learning outcomes offer a range of assessment types to serve a diverse student population?

Use learning taxonomies to inform learning outcomes

Learning taxonomies describe how a learner’s understanding develops from simple to complex when learning different subjects or tasks. They are useful here for identifying any foundational skills or knowledge needed for more complex learning, and for matching observable behaviors to different types of learning.

Bloom’s Taxonomy

Bloom’s Taxonomy is a hierarchical model and includes three domains of learning: cognitive, psychomotor, and affective. In this model, learning occurs hierarchically, as each skill builds on previous skills towards increasingly sophisticated learning. For example, in the cognitive domain, learning begins with remembering, then understanding, applying, analyzing, evaluating, and lastly creating.

Taxonomy of Significant Learning

The Taxonomy of Significant Learning is a non-hierarchical and integral model of learning. It describes learning as a meaningful, holistic, and integral network. This model has six intersecting domains: knowledge, application, integration, human dimension, caring, and learning how to learn.

See our resource on Learning Taxonomies and Verbs for a summary of these two learning taxonomies.

How to write learning outcomes

Writing learning outcomes can be made easier by using the ABCD approach. This strategy identifies four key elements of an effective learning outcome:

Consider the following example: Students (audience) , will be able to label and describe (behavior) , given a diagram of the eye at the end of this lesson (condition) , all seven extraocular muscles, and at least two of their actions (degree) .

Audience

Define who will achieve the outcome. Outcomes commonly include phrases such as “After completing this course, students will be able to...” or “After completing this activity, workshop participants will be able to...”

Keeping your audience in mind as you develop your learning outcomes helps ensure that they are relevant and centered on what learners must achieve. Make sure the learning outcome is focused on the student’s behavior, not the instructor’s. If the outcome describes an instructional activity or topic, then it is too focused on the instructor’s intentions and not the students.

Try to understand your audience so that you can better align your learning goals or objectives to meet their needs. While every group of students is different, certain generalizations about their prior knowledge, goals, motivation, and so on might be made based on course prerequisites, their year-level, or majors.

Use action verbs to describe observable behavior that demonstrates mastery of the goal or objective. Depending on the skill, knowledge, or domain of the behavior, you might select a different action verb. Particularly for learning objectives which are more specific, avoid verbs that are vague or difficult to assess, such as “understand”, “appreciate”, or “know”.

The behavior usually completes the audience phrase “students will be able to…” with a specific action verb that learners can interpret without ambiguity. We recommend beginning learning goals with a phrase that makes it clear that students are expected to actively contribute to progressing towards a learning goal. For example, “through active engagement and completion of course activities, students will be able to…”

Example action verbs

Consider the following examples of verbs from different learning domains of Bloom’s Taxonomy . Generally speaking, items listed at the top under each domain are more suitable for advanced students, and items listed at the bottom are more suitable for novice or beginning students. Using verbs and associated skills from all three domains, regardless of your discipline area, can benefit students by diversifying the learning experience.

For the cognitive domain:

- Create, investigate, design

- Evaluate, argue, support

- Analyze, compare, examine

- Solve, operate, demonstrate

- Describe, locate, translate

- Remember, define, duplicate, list

For the psychomotor domain:

- Invent, create, manage

- Articulate, construct, solve

- Complete, calibrate, control

- Build, perform, execute

- Copy, repeat, follow

For the affective domain:

- Internalize, propose, conclude

- Organize, systematize, integrate

- Justify, share, persuade

- Respond, contribute, cooperate

- Capture, pursue, consume

Often we develop broad goals first, then break them down into specific objectives. For example, if a goal is for learners to be able to compose an essay, break it down into several objectives, such as forming a clear thesis statement, coherently ordering points, following a salient argument, gathering and quoting evidence effectively, and so on.

State the conditions, if any, under which the behavior is to be performed. Consider the following conditions:

- Equipment or tools, such as using a laboratory device or a specified software application.

- Situation or environment, such as in a clinical setting, or during a performance.

- Materials or format, such as written text, a slide presentation, or using specified materials.

The level of specificity for conditions within an objective may vary and should be appropriate to the broader goals. If the conditions are implicit or understood as part of the classroom or assessment situation, it may not be necessary to state them.

When articulating the conditions in learning outcomes, ensure that they are sensorily and financially accessible to all students.

Degree

Degree states the standard or criterion for acceptable performance. The degree should be related to real-world expectations: what standard should the learner meet to be judged proficient? For example:

- With 90% accuracy

- Within 10 minutes

- Suitable for submission to an edited journal

- Obtain a valid solution

- In a 100-word paragraph

The specificity of the degree will vary. You might take into consideration professional standards, what a student would need to succeed in subsequent courses in a series, or what is required by you as the instructor to accurately assess learning when determining the degree. Where the degree is easy to measure (such as pass or fail) or accuracy is not required, it may be omitted.

Characteristics of effective learning outcomes

The acronym SMART is useful for remembering the characteristics of an effective learning outcome.

- Specific : clear and distinct from others.

- Measurable : identifies observable student action.

- Attainable : suitably challenging for students in the course.

- Related : connected to other objectives and student interests.

- Time-bound : likely to be achieved and keep students on task within the given time frame.

Examples of effective learning outcomes

These examples generally follow the ABCD and SMART guidelines.

Arts and Humanities

Learning goals.

Upon completion of this course, students will be able to apply critical terms and methodology in completing a written literary analysis of a selected literary work.

At the end of the course, students will be able to demonstrate oral competence with the French language in pronunciation, vocabulary, and language fluency in a 10 minute in-person interview with a member of the teaching team.

Learning objectives

After completing lessons 1 through 5, given images of specific works of art, students will be able to identify the artist, artistic period, and describe their historical, social, and philosophical contexts in a two-page written essay.

By the end of this course, students will be able to describe the steps in planning a research study, including identifying and formulating relevant theories, generating alternative solutions and strategies, and application to a hypothetical case in a written research proposal.

At the end of this lesson, given a diagram of the eye, students will be able to label all of the extraocular muscles and describe at least two of their actions.

Using chemical datasets gathered at the end of the first lab unit, students will be able to create plots and trend lines of that data in Excel and make quantitative predictions about future experiments.

- How to Write Learning Goals , Evaluation and Research, Student Affairs (2021).

- SMART Guidelines , Center for Teaching and Learning (2020).

- Learning Taxonomies and Verbs , Center for Teaching and Learning (2021).

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- CBE Life Sci Educ

- v.21(3); Fall 2022

Writing and Using Learning Objectives

Rebecca b. orr.

† Division of Academic Affairs, Collin College, Plano, TX 75074

Melissa M. Csikari

‡ HHMI Science Education, BioInteractive, Chevy Chase, MD 20815

Scott Freeman

§ Department of Biology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195

Michael C. Rodriguez

∥ Educational Psychology, College of Education and Human Development, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN 55455

Learning objectives (LOs) are used to communicate the purpose of instruction. Done well, they convey the expectations that the instructor—and by extension, the academic field—has in terms of what students should know and be able to do after completing a course of study. As a result, they help students better understand course activities and increase student performance on assessments. LOs also serve as the foundation of course design, as they help structure classroom practices and define the focus of assessments. Understanding the research can improve and refine instructor and student use of LOs. This essay describes an online, evidence-based teaching guide published by CBE—Life Sciences Education ( LSE ) at http://lse.ascb.org/learning-objectives . The guide contains condensed summaries of key research findings organized by recommendations for writing and using LOs, summaries of and links to research articles and other resources, and actionable advice in the form of a checklist for instructors. In addition to describing key features of the guide, we also identify areas that warrant further empirical studies.

INTRODUCTION

Learning objectives (LOs) are statements that communicate the purpose of instruction to students, other instructors, and an academic field ( Mager, 1997 ; Rodriguez and Albano, 2017 ). They form the basis for developing high-quality assessments for formative and summative purposes. Once LOs and assessments are established, instructional activities can help students master the material. Aligning LOs with assessments and instructional practice is the essence of backward course design ( Fink, 2003 ).

Many terms in the literature describe statements about learning expectations. The terms “course objectives,” “course goals,” “learning objectives,” “learning outcomes,” and “learning goals” are often used interchangeably, creating confusion for instructors and students. To clarify and standardize usage, the term “objective” is defined as a declarative statement that identifies what students are expected to know and do . At the same time, “outcome” refers to the results measured at the end of a unit, course, or program. It is helpful to think of LOs as a tool instructors use for describing intended outcomes, regardless of the process for achieving the outcome ( Mager, 1997 ). The term “goal” is less useful. Although it is often used to express more general expectations, there is no consistent usage in the literature.

In this guide, “learning objective” is defined as a statement that communicates the purpose of instruction using an action verb and describes the expected performance and conditions under which the performance should occur. Examples include:

- At the end of this lesson, students should be able to compare the processes of diffusion, osmosis, and facilitated diffusion, and provide biological examples that illustrate each process.

- At the end of this lesson, students should be able to predict the relative rates at which given ions and molecules will cross a plasma membrane in the absence of membrane protein and explain their reasoning.

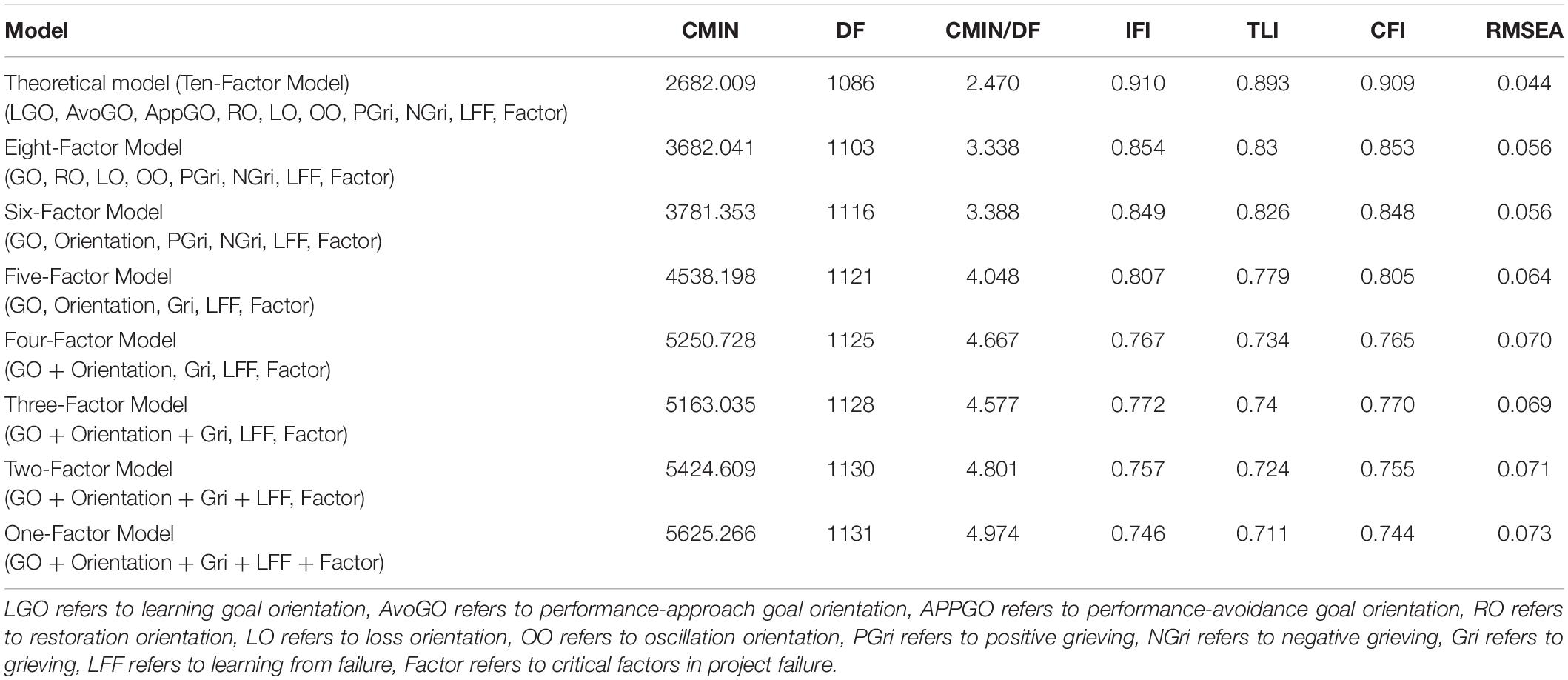

In terms of content and complexity, LOs should scaffold professional practice, requirements for a program, and individual course goals by communicating the specific content areas and skills considered important by the academic field ( Rodriguez and Albano, 2017 ). They also promote course articulation by supporting consistency when courses are taught by multiple instructors and furnishing valuable information about course alignment among institutions. As a result, LOs should serve as the basis of unit or module, course, and program design and can be declared in a nested hierarchy of levels. For clarity, we describe a hierarchy of LOs in Table 1 .

Levels of LOs ( Rodriguez and Albano, 2017 )

a Hereafter, our use of the term “learning objectives” specifically refers to instructional LOs.

This article describes an evidence-based teaching guide that aggregates, summarizes, and provides actionable advice from research findings on LOs. It can be accessed at http://lse.ascb.org/learning-objectives . The guide has several features intended to help instructors: a landing page that indicates starting points ( Figure 1 ), syntheses of observations from the literature, summaries of and links to selected papers ( Figure 2 ), and an instructor checklist that details recommendations and points to consider. The focus of our guide is to provide recommendations based on the literature for instructors to use when creating, revising, and using instructional LOs in their courses. The Effective Construction section provides evidence-based guidelines for writing effective LOs. The Instructor Use section contains research summaries about using LOs as a foundational element for successful course design, summaries of the research that supports recommended practices for aligning LOs with assessment and classroom instruction, and direction from experts for engaging with colleagues in improving instructor practice with LOs. The Student Use section includes a discussion on how students use LOs and how instructor guidance can improve student use of LOs, along with evidence on the impact of LO use coupled with pretests, transparent teaching methods, and summaries of LO-driven student outcomes in terms of exam scores, depth of learning, and affect (e.g., perception of utility and self-regulated learning). Some of the questions and considerations that serve to organize the guide are highlighted in the following sections.

LO guide landing page, which provides readers with an overview of choice points.

Screenshots representing summaries of and links to selected papers.

WRITING EFFECTIVE INSTRUCTIONAL LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Writing LOs effectively is essential, as their wording should provide direction for developing instructional activities and guide the design of assessments. Effective LOs clearly communicate what students should know and be able to do and are written to be behavioral, measurable, and attainable ( Rodriguez and Albano, 2017 ). It is particularly important that each LO is written with enough information to ensure that other knowledgeable individuals can use the LO to measure a learner’s success and arrive at the same conclusions ( Mager, 1997 ). Clear, unambiguous wording encourages consistency across sections and optimizes student use of the stated LOs.

Effective LOs specify a visible performance—what students should be able to do with the content—and may also include conditions and the criteria for acceptable performance ( Mager, 1997 ). When constructing an LO, one should use an action verb to describe what students are expected to know and be able to do with the disciplinary knowledge and skills ( Figure 3 ). Bloom’s taxonomy of cognitive skills provides a useful framework for writing LOs that embody the intended complexity and the cognitive demands involved in mastering them ( Bloom, 1956 ; Anderson and Krathwohl, 2001 ). Assessment items and course activities can then be aligned with LOs using the Blooming Biology Tool described by Crowe et al. (2008) . However, LOs should not state the instructional method(s) planned to accomplish the objectives or be written so specifically as to be assessment tasks themselves ( Mager, 1997 ).

Components of an LO.

Our Instructor Checklist provides specific recommendations for writing LOs, along with a link to examples of measurable action verbs associated with Bloom’s taxonomy.

COURSE DESIGN: ALIGNING LEARNING OBJECTIVES WITH ASSESSMENT AND CLASSROOM INSTRUCTION

Course designs and redesigns built around clear and measurable LOs result in measurable benefits to students (e.g., Armbruster et al. , 2009 , and other citations in the Course and Curriculum Design and Outcomes section of this guide). LOs are established as the initial step in backward design ( McTighe and Wiggins, 2012 ). They provide a framework for instructors to 1) design assessments that furnish evidence on the degree of student mastery of knowledge and skills and 2) select teaching and learning activities that are aligned with objectives ( Mager, 1997 ; Rodriguez and Albano, 2017) . Figure 4 depicts depicts integrated course course design, emphasizing the dynamic and reciprocal associations among LOs, assessment, and teaching practice.

Components of integrated course design (after Fink, 2003 ).

Used in this way, LOs provide a structure for planning assessments and instruction while giving instructors the freedom to be creative and flexible ( Mager, 1997 ; Reynolds and Kearns, 2017 ). In essence, LOs respond to the question: “If you don’t know where you’re going, how will you know which road to take and how do you know when you get there?” ( Mager, 1997 , p. 14). When assessments are created, each assessment item or task must be specifically associated with at least one LO and measure student learning progress on that LO. The performance and conditions components of each LO should guide the type of assessment developed ( Mager, 1997 ). Data gathered from assessment results (feedback) can then inform future instruction. The Assessment section of our guide contains summaries of research reporting the results of aligning assessment with LOs and summaries of frameworks that associate assessment items with LOs.

The purpose of instruction is communicated to students most effectively when instructional activities are aligned with associated instructional and course-level LOs (e.g., Chasteen et al. , 2011 , and others within the Instructor Use section of this guide). The literature summarized in the Course and Curriculum Design section of the guide supports the hypothesis that student learning is strongly impacted by what instructors emphasize in the classroom. In the guide’s Student Buy-In and Metacognition section, we present strategies instructors have used to ensure that LOs are transparent and intentionally reinforced to students . When LOs are not reinforced in instruction, students may conclude that LOs are an administrative requirement rather than something developed for their benefit. The guide’s Instructor Checklist contains evidence-based suggestions for increasing student engagement through making LOs highly visible.

Using LOs as the foundation of course planning results in a more student-centered approach, shifting the focus from the content to be covered to the concepts and skills that the student should be able to demonstrate upon successfully completing the course (e.g., Reynolds and Kearns, 2017 , and others within the Active Learning section of this guide). Instead of designing memorization-driven courses that are “a mile wide and an inch deep,” instructors can use LOs to focus a course on the key concepts and skills that prepare students for future success in the field. Group problem solving, discussions, and other class activities that allow students to practice and demonstrate the competencies articulated in LOs can be prioritized over lectures that strive to cover all of the content. The guide’s Active Learning section contains a summary of the literature on the use of LOs to develop activities that promote student engagement, provide opportunities for students to practice performance, and allow instructors to gather feedback on learning progress. The evidence-based teaching guides on Group Work and Peer Instruction provide additional evidence and resources to support these efforts.

ENGAGING WITH COLLEAGUES TO IMPROVE LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Momsen et al. (2010) examined Bloom’s level of assessment items and course goals from 50 faculty in 77 introductory biology courses for majors. The authors found that 93% of the assessment items were rated low-level Bloom’s, and 69% of the 250 course goals submitted were rated low-level Bloom’s ( Momsen et al. , 2010 ). A recent survey of 38 instructors of biology for nonmajors found similar results. Heil et al. (unpublished data) reported that 74% of the instructors surveyed write their own LOs, and 95% share their LOs with their students ( Heil et al. , unpublished data ). The action verbs used in 66% of these LOs were low-level Bloom’s cognitive skills, assessing knowledge and comprehension ( Heil et al. , unpublished data ). Further, an analysis of 1390 LOs from three best-selling biology textbooks for nonscience majors found that 89% were rated Bloom’s cognitive skill level 1 or level 2. Vision & Change competencies, as articulated in the BioSkills Guide ( Clemmons et al. , 2020 ), were only present in 17.7% of instructors’ LOs and 7% of the textbook LOs ( Heil et al. , unpublished data ). These data suggest that, in introductory biology for both majors and nonmajors, most instructors emphasize lower-order cognitive skills that are not aligned with teaching frameworks.

Researchers have documented effective strategies to improve instructors’ writing and use of LOs. The guide’s Engaging with Colleagues section contains summaries demonstrating that instructor engagement with the scholarship of teaching and learning can improve through professional development in collaborative groups—instructors can benefit by engaging in a collegial community of practice as they implement changes in their teaching practices (e.g., Richlin and Cox, 2004 , and others within the Engaging with Colleagues section of the guide). Collaboration among institutions can create common course-level LOs that promote horizontal and vertical course alignment, which can streamline articulation agreements and transfer pathways between institutions ( Kiser et al. , 2022 ). Departmental efforts to map LOs across program curricula can close gaps in programmatic efforts to convey field-expected criteria and develop student skills throughout a program ( Ezell et al. , 2019 ). The guide contains summaries of research-based recommendations that encourage departmental support for course redesign efforts (e.g., Pepper et al. , 2012 , and others within the Engaging with Colleagues section of the guide).

HOW DO LEARNING OBJECTIVES IMPACT STUDENTS?

When instructors publish well-written LOs aligned with classroom instruction and assessments, they establish clear goalposts for students ( Mager, 1997 ). Using LOs to guide their studies, students should no longer have to ask “Do we have to know …?” or “Will this be on the test?” The Student Use section of the guide contains summaries of research on the impact of LOs from the student perspective.

USING LEARNING OBJECTIVES TO GUIDE STUDENT LEARNING

Researchers have shown that students support the use of LOs to design class activities and assessments. In the Guiding Learning section of the guide, we present evidence documenting how students use LOs and how instructors can train students to use them more effectively ( Brooks et al. , 2014 , and other citations within this section of the guide). However, several questions remain about the impact of LOs on students. For example, using LOs may improve students’ ability to self-regulate, which in turn may be particularly helpful in supporting the success of underprepared students ( Simon and Taylor, 2009 ; Osueke et al. , 2018 ). But this hypothesis remains untested.

There is evidence that transparency in course design improves the academic confidence and retention of underserved students ( Winkelmes et al. , 2016 ), and LOs make course expectations transparent to students. LOs are also reported to help students organize their time and effort and give students, particularly those from traditionally underserved groups, a better idea of areas in which they need help ( Minbiole, 2016 ). Additionally, LOs facilitate the construction of highly structured courses by providing scaffolding for assessment and classroom instruction. Highly structured course design has been demonstrated to improve all students’ academic performance. It significantly reduces achievement gaps (difference in final grades on a 4.0 scale) between disadvantaged and nondisadvantaged students ( Haak et al. , 2011 ). However, much more evidence is needed on how LOs impact underprepared and/or underresourced students:

- Does the use of LOs lead to increased engagement with the content and/or instructor by underprepared and/or underserved students?

- Does LO use have a disproportionate and positive impact on the ability of underprepared and/or underresourced students to self-direct their learning?

- Is there a significant impact on underserved students’ academic performance and persistence with transparent LOs in place?

In general, how can instructors help students realize the benefits of well-written LOs? Research indicates that many students never receive instruction on using LOs ( Osueke et al. , 2018 ). However, when students receive explicit instruction on LO use, they benefit ( Osueke et al. , 2018 ). Examples include teaching students how to turn LOs into questions and how to answer and use those questions for self-assessment ( Osueke et al. , 2018 ). Using LOs for self-assessment allows students to take advantage of retrieval practice, a strategy that has a positive effect on learning and memory by helping students identify what they have and have not learned ( Bjork and Bjork, 2011 ; Brame and Biel, 2015 ). Some students, however, may avoid assessment strategies that identify what they do not understand or know because they find difficulty uncomfortable ( Orr and Foster, 2013 ; Dye and Stanton, 2017 ).

Brooks et al. (2014) reported that about one-third of students surveyed indicated that they had underestimated the depth of learning required to pass an assessment on the stated LOs. Further, students may have difficulty understanding the scope or expectations of stated LOs until after learning the content. Research on how instructors should train students to use LOs has been limited, and many of these open questions remain:

- What are the best practices to help students use LOs in self-assessment strategies?

- How can instructors motivate students to go outside their comfort zones for learning and use LOs in self-assessment strategies?

- How can instructors help students better understand the performance, conditions, and criteria required by the LOs to demonstrate successful learning?

- How might this differ for learners at different institutions, where academic preparedness and/or readiness levels may vary greatly?

CAPITALIZING ON THE PRETEST EFFECT

The guide’s Pretesting section contains research findings building on the pretesting effect reported by Little and Bjork (2011) . Pretesting with questions based on LOs has been shown to better communicate course expectations to students, increase student motivation and morale by making learning progress more visible, and improve retention of information as measured by final test scores ( Beckman, 2008 ; Sana et al. , 2020 ). Operationalizing LOs as pretest questions may serve as an effective, evidence-based model for students to self-assess and prepare for assessment. The research supporting this strategy is very limited, however, prompting the following questions:

- How broadly applicable—in terms of discipline and course setting—is the benefit of converting LOs to pretest questions?

- Is the benefit of operationalizing LOs to create pretests sustained when converting higher-level Bloom’s LOs into pretest questions?

- Does the practice of using LOs to create pretest questions narrow students’ focus such that the breadth/scope of their learning is overly limited/restricted? This is particularly concerning if students underestimate the depth of learning required by the stated LOs ( Brooks et al. , 2014 ).

- Could this practice help instructors teach students to use LOs to self-assess with greater confidence and persistence?

STUDENT OUTCOMES

The guide concludes with research summaries regarding the specific benefits to students associated with the use of LOs. Specifically, 1) alignment of LOs and assessment items is associated with higher exam scores (e.g., Armbruster et al. , 2009 , and others within the Outcomes section of the guide); 2) exam items designed to measure student mastery of LOs can support higher-level Bloom’s cognitive skills (e.g., Armbruster et al. , 2009 , and others within the Outcomes section of the guide); and 3) students adjust their learning approach based on course design and have been shown to employ a deeper approach to learning in courses in which assessment and class instruction are aligned with LOs ( Wang et al. , 2013 ).

CHALLENGES IN MEASURING THE IMPACT OF LEARNING OBJECTIVES

It is difficult to find literature in which researchers measured the impact of LOs alone on student performance due to their almost-necessary conflation with approaches to assessment and classroom practices. We argue that measuring the impact of LOs independently of changes in classroom instruction or assessment would be inadvisable, considering the role that LOs play in integrated course design ( Figure 4 ). Consistent with this view, the guide includes summaries of research findings on course redesigns that focus on creating or refining well-defined, well-written LOs; aligning assessment and classroom practice with the LOs; and evaluating student use and/or outcomes ( Armbruster et al. , 2009 ; Chasteen et al. , 2011 ). We urge instructors to use LOs from this integrated perspective.

CONCLUSIONS

We encourage instructors to use LOs as the basis for course design, align LOs with assessment and instruction, and promote student success by sharing their LOs and providing practice with how best to use them. Instructor skill in using LOs is not static and can be improved and refined with collaborative professional development efforts. Our teaching guide ends with an Instructor Checklist of actions instructors can take to optimize their use of LOs ( http://lse.ascb.org/learning-objectives/instructor-checklist ).

Acknowledgments

We thank Kristy Wilson for her guidance and support as consulting editor for this effort and Cynthia Brame and Adele Wolfson for their insightful feedback on this paper and the guide. This material is based upon work supported in part by the National Science Foundation under grant number DUE 201236 2. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

- Anderson, L. W., Krathwohl, D. R. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives (Complete ed.). New York, NY: Longman. [ Google Scholar ]

- Armbruster, P., Patel, M., Johnson, E., Weiss, M. (2009). Active learning and student-centered pedagogy improve student attitudes and performance in introductory biology . CBE—Life Sciences Education , 3 ( 8 ), 203–213. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Beckman, W. S. (2008). Pre-testing as a method of conveying learning objectives . Journal of Aviation/Aerospace Education & Research , 17 ( 2 ), 61–70. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bjork, E. L., Bjork, R. A. (2011). Making things hard on yourself, but in a good way: Creating desirable difficulties to enhance learning . In Gernsbacher, M. A., Pomerantz, J. (Eds.), Psychology and the real world: Essays illustrating fundamental contributions to society (2nd ed., pp. 59–68). New York, NY: Worth Publishers. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bloom, B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals by a committee of college and university examiners. Handbook I: Cognitive domain . New York, NY: David McKay. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brame, C. J., Biel, R. (2015). Test-enhanced learning: The potential for testing to promote greater learning in undergraduate science courses . CBE—Life Sciences Education , 14 , 1–12. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brooks, S., Dobbins, K., Scott, J., Rawlinson, M., Norman, R. I. (2014). Learning about learning outcomes: The student perspective . Teaching in Higher Education , 19 ( 6 ), 721–733. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chasteen, S. V., Perkins, K. K., Beale, P. D., Pollock, S. J., Wieman, C. E. (2011). A thoughtful approach to instruction: Course transformation for the rest of us . Journal of College Science Teaching , 40 , 24–30. [ Google Scholar ]

- Clemmons, A. W., Timbrook, J., Herron, J. C., Crowe, A. J. (2020). BioSkills Guide: Development and national validation of a tool for interpreting the Vision and Change core competencies . CBE—Life Sciences Education , 19 ( 20 ), 1–19. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Crowe, A., Dirks, C., Wenderoth, M. P. (2008). Biology in Bloom: Implementing Bloom’s taxonomy to enhance student learning in biology . CBE—Life Sciences Education , 7 ( 4 ), 368–381. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dye, K. M., Stanton, J. D. (2017). Metacognition in upper-division biology students: Awareness does not always lead to control . CBE—Life Sciences Education , 16 ( 2 ), 1–14. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ezell, J. D., Lending, D., Dillon, T. W., May, J., Hurney, C. A., Fulcher, K. H. (2019). Developing measurable cross-departmental learning objectives for requirements elicitation in an information systems curriculum . Journal of Information Systems Education , 30 ( 1 ), 27–41. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fink, L. D. (2003). A self-directed guide to designing courses for significant learning . San Francisco, CA: Dee Fink & Associates. https://www.deefinkandassociates.com/GuidetoCourseDesignAug05.pdf [ Google Scholar ]

- Haak, D. C., HilleRisLambers, J., Pitre, E., Freeman, S. (2011). Increased structure and active learning reduce the achievement gap in introductory biology . Science , 332 ( 6034 ), 1213–1216. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Heil, H., Gormally, C., Brickman, P. (in press). Low-level learning and expectations for non-science majors . Journal of College Science Teaching . [ Google Scholar ]

- Kiser, S., Kayes, L. J., Baumgartner, E., Kruchten, A., Stavrianeas, S. (2022). Statewide curricular alignment & learning outcomes for introductory biology: Using Vision & Change as a vehicle for collaboration . American Biology Teacher , 84 ( 3 ), 130–136. [ Google Scholar ]

- Little, J. L., Bjork, E. L. (2011). Pretesting with multiple-choice questions facilitates learning . Cognitive Science , 33 , 294–299. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mager, R. F. (1962). Preparing instructional objectives: A critical tool in the development of effective instruction (1st ed.). Palo Alto, CA: Fearon Publishers. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mager, R. F. (1997). Preparing instructional objectives: A critical tool in the development of effective instruction (3rd ed.). Atlanta, GA: Center for Effective Performance. [ Google Scholar ]

- McTighe, J., Wiggins, G. (2012, March). Understanding by design framework . Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. [ Google Scholar ]

- Minbiole, J. (2016). Improving course coherence & assessment rigor: “Understanding by Design” in a nonmajors biology course . American Biology Teacher , 78 ( 6 ), 463–470. [ Google Scholar ]

- Momsen, J. L., Long, T. M., Wyse, S. A., Ebert-May, D. (2010). Just the facts? Introductory undergraduate biology courses focus on low-level cognitive skills . CBE—Life Sciences Education , 9 ( 4 ), 435–440. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Orr, R., Foster, S. (2013). Increasing student success using online quizzing in introductory (majors) biology . CBE—Life Sciences Education , 12 ( 3 ), 509–514. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Osueke, B., Mekonnen, B., Stanton, J. D. (2018). How undergraduate science students use learning objectives to study . Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education , 19 ( 2 ), 1–8. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pepper, R. E., Chasteen, S. V., Pollock, S. J., Perkins, K. K. (2012). Facilitating faculty conversations: Development of consensus learning goals . AIP Conference Proceedings , 1413 , 291. [ Google Scholar ]

- Reynolds, H. L., Kearns, K. D. (2017). A planning tool for incorporating backward design, active learning, and authentic assessment in the college classroom . College Teaching , 65 ( 1 ), 17–27. [ Google Scholar ]

- Richlin, L., Cox, M. D. (2004). Developing scholarly teaching and the scholarship of teaching and learning through faculty learning communities . New Directions for Teaching and Learning , 97 , 127–135. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rodriguez, M. C., Albano, A. D. (2017). The college instructor’s guide to writing test items: Measuring student learning . New York, NY: Routledge. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sana, F., Forrin, N. D., Sharma, M., Dubljevic, T., Ho, P., Jalil, E., Kim, J. A. (2020). Optimizing the efficacy of learning objectives through pretests . CBE—Life Sciences Education , 19 ( 3 ), 1–10. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Simon, B., Taylor, J. (2009). What is the value of course-specific learning goals? Journal of College Science Teaching , 39 , 52–57. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wang, X., Su, Y., Cheung, S., Wong, E., Kwong, T. (2013). An exploration of Biggs’ constructive alignment in course design and its impact on students’ learning approaches . Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education , 38 , 477–491. [ Google Scholar ]

- Winkelmes, M., Bernacki, M., Butler, J., Zochowski, M., Golanics, J., Weevil, K. H. (2016). A teaching intervention that increases underserved college students’ success . Peer Review , 18 ( 1/2 ), 31–36. [ Google Scholar ]

- Learning Goals

- Course Design

- UDL Syllabus

- Learning Goals (Currently Selected)

- Emotion and Learning

- UDL and Assessment

- Executive Functioning in Online Environments

- Social Learning

- Blended Courses

- Case-Based Learning

- Working with Industry Partners

- Using LMS Data to Inform Course Design

What is this resource about? This resource discusses the ways in which learning goals can be constructed through the lens of Universal Design for Learning . Within instructional design, goals are expectations for knowledge, skills, or outcomes. These expectations can be communicated as performance goals -- which focus on proving ability -- or as learning goals (also known as mastery goals), which emphasize developing and improving an ability. 1 Read more about Learning Goals from a UDL Perspective , and Separating the Means from the Ends .

Why is this important in higher education? Learners at all stages benefit from being aware of their own goals and the goals instructors and institutions hold for them. 2 Some instructional circumstances call for performance goals; but learning goals, oriented towards growth, are more likely to support course completion, persistence through challenging transitions, and change in deeply-held conceptions. 3

UDL Connections

Consider how goals are articulated and communicated: goals that unnecessarily prescribe narrow means of achievement will inadvertently privilege, exclude, and under-engage learners. 4 Clear goals are the cornerstone of well-designed curricula, as only through clarification of what learners are expected to accomplish, and by when, can instructors begin to consider which assessments , methods and materials will be most effective.

Learning Goals from a UDL Perspective

In the UDL model, goals move beyond their traditional role in curriculum planning as mere content or performance markers. A UDL approach seeks to create clear learning goals and support the development of expert, lifelong learners that are strategic, resourceful, and motivated. 5 A UDL approach to effective learning goals in postsecondary settings consists of three key components:

- separating the means from the ends

- addressing variability in learning

- providing UDL options in the materials, methods, and assessments

Separating the Means from the Ends

From a UDL perspective, goals and objectives should be attainable by different learners in different ways. In some instances, linking a goal with the means for achievement may be intentional; however, often times we unintentionally embed the means of achievement into a goal, thereby restricting the pathways students can take to meet it.

The following sample curricular goal is articulated as: “Write a paragraph about how the circulatory system works.” What are the barriers this goal might pose for students?

Writing a paragraph is an additional task layered over mastery of the content knowledge that you want your students to attain. Rephrasing this goal into something like, “Describe a complete cycle in the circulatory system” is more explicit about what students should be able to explain, and allows flexibility in terms of how students convey their knowledge (create a diagram, label an image, write out the steps in the process, make a short video explaining an image, etc.). It is also more of a learning goal than a performance goal in that it invites students to demonstrate the fullest extent of their understanding – rather than asking them to prove that they can write a paragraph.

In your College Writing Seminar, the learning goal (learning how to write strong essays) is frequently linked to the production means (writing essays). Given the wide variability of writing abilities in the classroom, you want to be sure that your students first get a strong understanding of the concept of a thesis statement first before adding the additional challenge of writing one.

In the case of this learning objective, the desired outcome is that students understand the concept of a strong thesis statement--perhaps as a prerequisite to writing one. Therefore, the means by which students demonstrate this ability can be more flexible, since the concept of a thesis statement and the ability to write one are not always one in the same. Students could write a thesis statement, but they could also put forward a video with a narrative, or some sort of visual. Requiring that students fulfill this objective through only one modality would, for some students, add task-irrelevant demands that pose a barrier to their fundamental understanding of a thesis statement.

The solutions above illustrate a key characteristics of well-designed goals: to make explicit the desired outcomes, rather than the means of achieving those outcomes. By focusing on the desired outcomes, instructors are able to maintain high expectations for students while opening multiple pathways towards achievement. This focus also capitalizes on the varied strengths of a wider range of students. Such support encourages persistence and content mastery that otherwise might be inadvertently deterred.

Goals need to be relevant to students. Especially at the postsecondary level -- where there is a focus on functioning independently in professions or life after school -- educators must consider that “students will never use knowledge they don't care about, nor will they practice or apply skills they don't find valuable.” 6

1 Dweck, C. S. (1986). Motivational processes affecting learning. American Psychologist, 41(10), 1040; Rusk, N., Tamir, M., & Rothbaum, F. (2011). Performance and learning goals for emotion regulation. Motivation and Emotion, 35(4), 444-460. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11031-011-9229-6

2 Simon, B., & Taylor, J. (2009). What is the value of course-specific learning goals. Journal of College Science Teaching, 39(2), 52-57. https://testwww2.bc.edu/maya-tamir/download/rusk%20et%20al_201

3 Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2012). Mindsets that promote resilience: When students believe that personal characteristics can be developed. Educational Psychologist, 47(4), 302-314; Ranellucci, J., Muis, K. R., Duffy, M., Wang, X., Sampasivam, L., & Franco, G. M. (2013). To master or perform? Exploring relations between achievement goals and conceptual change learning. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 83(3), 431-451. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23822530

4 Meyer, A., Rose, D. H., & Gordon, D. (2014). Universal design for learning: Theory and practice. Wakefield MA: CAST Professional Publishing. http://udltheorypractice.cast.org/login

6 Rose, D. H., Harbour, W. S., Johnston, C. S., Daley, S. G., & Abarbanell, L. (2006). Universal Design for Learning in Postsecondary Education: Reflections on Principles and their Application. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 19(2), 135-151. https://www.cast.org/products-services/resources/2006/udl-postsecondary-education-reflections-principles-application-rose-johnston-daley

UDL is an educational approach based on the learning sciences with three primary principles—multiple means of representation of information, multiple means of student action and expression, and multiple means of student engagement.

Assessment is the process of gathering information about a learner’s performance using a variety of methods and materials in order to determine learners’ knowledge, skills, and motivation for the purpose of making informed educational decisions.

Video is the recording, reproducing, or broadcasting of moving visual images.

- U.S. Locations

- UMGC Europe

- Learn Online

- Find Answers

- 855-655-8682

- Current Students

UMGC Effective Writing Center Designing an Effective Thesis

Explore more of umgc.

- Writing Resources

Key Concepts

- A thesis is a simple sentence that combines your topic and your position on the topic.

- A thesis provides a roadmap to what follows in the paper.

- A thesis is like a wheel's hub--everything revolves around it and is attached to it.

After your prewriting activities-- such as assignment analysis and outlining--you should be ready to take the next step: writing a thesis statement. Although some of your assignments will provide a focus for you, it is still important for your college career and especially for your professional career to be able to state a satisfactory controlling idea or thesis that unifies your thoughts and materials for the reader.

Characteristics of an Effective Thesis

A thesis consists of two main parts: your overall topic and your position on that topic. Here are some example thesis statements that combine topic and position:

Sample Thesis Statements

Importance of tone.

Tone is established in the wording of your thesis, which should match the characteristics of your audience. For example, if you are a concerned citizen proposing a new law to your city's board of supervisors about drunk driving, you would not want to write this:

“It’s time to get the filthy drunks off the street and from behind the wheel: I demand that you pass a mandatory five-year license suspension for every drunk who gets caught driving. Do unto them before they do unto us!”

However, if you’re speaking at a concerned citizen’s meeting and you’re trying to rally voter support, such emotional language could help motivate your audience.

Using Your Thesis to Map Your Paper for the Reader

In academic writing, the thesis statement is often used to signal the paper's overall structure to the reader. An effective thesis allows the reader to predict what will be encountered in the support paragraphs. Here are some examples:

Use the Thesis to Map

Three potential problems to avoid.

Because your thesis is the hub of your essay, it has to be strong and effective. Here are three common pitfalls to avoid:

1. Don’t confuse an announcement with a thesis.

In an announcement, the writer declares personal intentions about the paper instead stating a thesis with clear point of view or position:

Write a Thesis, Not an Announcement

2. a statement of fact does not provide a point of view and is not a thesis..

An introduction needs a strong, clear position statement. Without one, it will be hard for you to develop your paper with relevant arguments and evidence.

Don't Confuse a Fact with a Thesis

3. avoid overly broad thesis statements.

Broad statements contain vague, general terms that do not provide a clear focus for the essay.

Use the Thesis to Provide Focus

Practice writing an effective thesis.

OK. Time to write a thesis for your paper. What is your topic? What is your position on that topic? State both clearly in a thesis sentence that helps to map your response for the reader.

Our helpful admissions advisors can help you choose an academic program to fit your career goals, estimate your transfer credits, and develop a plan for your education costs that fits your budget. If you’re a current UMGC student, please visit the Help Center .

Personal Information

Contact information, additional information.

By submitting this form, you acknowledge that you intend to sign this form electronically and that your electronic signature is the equivalent of a handwritten signature, with all the same legal and binding effect. You are giving your express written consent without obligation for UMGC to contact you regarding our educational programs and services using e-mail, phone, or text, including automated technology for calls and/or texts to the mobile number(s) provided. For more details, including how to opt out, read our privacy policy or contact an admissions advisor .

Please wait, your form is being submitted.

By using our website you agree to our use of cookies. Learn more about how we use cookies by reading our Privacy Policy .

Creating Measurable Learning Objectives

Sara Bakker

Music Department, Utah State University

E-mail: [email protected]

Received June 2019

Peer Reviewed by: Abigail Shupe, Daniel Blim

Accepted for publication September 2019

Published September 2, 2020

https://doi.org/10.18061/es.v7i0.7369

This essay argues for the articulation of learning goals at all levels of teaching in music theory, from the curriculum to the individual lesson plan. It summarizes the use of cognitive-process verbs from the field of learning theory and acknowledges a confusing overlap between common music theory tasks and cognitive-process verbs. It suggests a model for stating learning goals in music theory that blends our current terminology with more universal and established terms. It concludes with a detailed discussion of several models of learning goals at the assignment, course, and curricular levels.

Keywords: goals, objectives, outcomes, Bloom's taxonomy, verbs, curriculum

Introduction

"[A]ll aspects of theory teaching—from the presentation of lecture material and drill practice to the construction of curricular models and statements of objectives—should be patterned by design and not by chance ."

"While a philosophy may remain unspoken, it should never remain unknown ."

These statements come from the second edition of Michael Rogers's (2004, 15–16, emphasis added) foundational book on music theory pedagogy. They emphasize, much like the book more broadly, the importance of intention in every aspect of teaching: lessons, practice, curricula, and learning goals. These are indeed laudable, almost superfluous aims in teaching, and yet the book, and indeed the field more broadly, has not developed them evenly. While the field of music theory pedagogy has flourished in the development of innovative and effective ways of teaching, I argue that it has grossly neglected learning goals. There is a critical lack of research in music theory to assist in selecting or articulating them. I hypothesize that articulating learning goals is especially challenging because many common music-theory tasks do not fit neatly in the most commonly used model for creating learning goals, the Bloom taxonomy. Finally, I provide sample learning goals and critique real-world examples of learning goals at three levels of learning—assignment, course, and curriculum.

Education researchers distinguish between learning objectives and learning outcomes , both of which are examples of goal-setting for learning. Learning objectives focus on a specific skill and are most appropriate at the lesson- or assignment-level, whereas learning outcomes focus on more synthetic skill sets and are most appropriate at the course- or curriculum-level. In the literature, these are treated as distinct categories. Individual studies and articles tend to address either objectives or outcomes. I have found it helpful in my own teaching, however, to group them together. I understand objectives and outcomes as different by degree, but not in kind, and will use "learning goal" as an umbrella term to refer to goal-setting for learning at any level. Learning goals are statements of the knowledge and skills that students are expected to demonstrate as a result of learning. They can address learning at any level, from individual lessons and assignments to whole courses and curricula. Thinking of learning goals more holistically is helpful in coordinating different levels of teaching, ensuring a good fit between curricular and course goals on the one hand and day to day classroom activities on the other.

According to renowned specialist in course design Allen Miller (1987) , learning goals serve three main purposes. They (1) clarify for students the instructor's expectations of learning so that students can direct their efforts and monitor their own progress, (2) assist instructors in selecting and organizing appropriate teaching and learning activities, and (3) assist instructors in selecting appropriate ways to assess student-learning. In addition to this, I would add that they (4) can also be used to coordinate instructors, both across sections of a single course and across a curriculum to ensure students are prepared for subsequent courses.

In music theory pedagogy, we have no foundational references to assist with selecting or articulating learning goals. Anna Gawboy (2013) confronts the issue in a syllabus-writing workshop. She is stumped by its most fundamental question, "What do you want your students to be able to do after taking your class?" Gawboy seeks models from the syllabi of courses she has taken and ones her colleagues taught, but finds that none describe the course from the perspective of student-doing. Instead, she finds descriptions of what the class will cover, answering a related, but different question, "What do you want your students to know after taking your class?" Essentially, Gawboy is describing a common confusion between content goals and learning goals. The difference is subtle: one frames a class from the perspective of teacher-input (this is what I will teach you), while the other frames it with student-output (this is what you will be able to do because of what you have learned). Without adequate models and resources, Gawboy frames the course she is designing at the workshop with content-goals instead of learning-goals, and realizes retrospectively that in so doing she "managed to sidestep the most profound question facing every theory teacher."

Had she looked to contemporary music theory literature for guidance, she would have found only two sources, neither of which would have been much help. Rogers (2004) underscores the importance of learning goals with statements such as those quoted at the outset of this article, but does not go into enough detail to even provide a workable definition. Deborah Rifkin and Phillip Stoecker (2011) address learning from a student-doing perspective, but they only address the aural skills classroom in their model. Indeed, music theory literature on learning goals remains an underrepresented area. Editors Rachel Lumsden and Jeffrey Swinkin (2018) include over twenty essays on music theory pedagogy, only one of which address learning goals with any intentionality. Although they are central to Brian Alegant's chapter, readers would not know to look for them based on the title, "Teaching Post-Tonal Aural Skills." Echoes of the concept of learning goals are also present in essays by Janet Bourne and Elizabeth West Marvin, but learning goals are not the central point of any chapter. Leigh VanHandel (2020) similarly lacks dedicated essays on learning goals. Searches of keywords "goal," "objective," and "outcome" return no hits on the Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy 's website. Perhaps it is telling that the two sources that foreground learning goals, do so in relation to aural skills pedagogy. Maybe we feel that skills classes are where students do things, as opposed to learn things. This is a false distinction, however, because learning should always be framed as something students can do because of information, reflection, teaching, and so on.

Designing Learning Goals

Most recommendations for articulating learning goals emphasize three main issues. Learning goals should (1) be student-centered, (2) emphasize the appropriate cognitive task using codified verbs, and (3) name the applicable course content. Some also recommend (4) clarifying any constraints, such as time, approved reference material, etc., and (5) listing the specific instruction that prepares students, such as a lesson, reading, module, course, etc. To read a few examples parsed according to these categories, please see Example 2.

One of the most crucial elements of a learning goal is a verb that clearly defines the intended task. These verbs both focus attention on student-doing and indicate possible methods of assessment. The most commonly referred to taxonomy of such verbs is by learning theorists Harold Bloom and David Krathwohl (1956) , updated by Lorin Anderson and David Krathwohl (2001) . Their taxonomy codifies six hierarchical categories of knowledge, each of which is named by a "hallmark" verb and exemplified by similar verbs. Each category subsumes all categories to its left, modeling increased processing of information, incorporation of educated opinions, use of originality, and general cognitive load with each leftward category. Example 1 reproduces an especially concise list, although the information in the taxonomy is widely available in a variety of formats , including automated builders , and in Rifkin and Stoecker (2011) with modifications for aural-skills tasks.

Designing Music Theory Learning Goals

Two special issues confront teachers of music theory who wish to write clear learning goals: verb-fit for music theory learning and unfamiliarity with appropriate models of goals at various levels of learning.

Verb-Fit for Music Theory

Choosing appropriate verbs is essential to the success and clarity of learning goals, yet there are issues with applying Bloom-verbs to music theory. One challenge is that many common music theory tasks are actually quite complex, relying on multiple component cognitive tasks. Labeling nonchord tones, for example, requires an understanding of Roman numerals, which itself requires an understanding of keys, scales, chords, and inversions. We might think that naming nonchord tones is an "Understand" task, when in most contexts it would more likely be an "Evaluate" task. Other music theory tasks may also be surprisingly complex to instructors, including stylistic composition ("Create"), harmonic dictation and sight singing ("Evaluate," where the most complex element involves judging the fit between the given stimulus and what the student produces), or resolving chordal 7ths properly ("Apply").

A second complication with using Bloom verbs in music theory is that "Analyze" is a category unto itself. Analysis is perhaps the quintessential music theory task, one we know, love, and assign frequently. Yet as my previous example suggests, we must be careful not to conflate analytical tasks with "Analyze" tasks. Here are some common analytical tasks that are not "Analyze" tasks:

- Analyzing Roman numerals in contexts without nonchord tones; analyzing pre-segmented set classes ("Understand")

- Analyzing or realizing figured bass ("Apply")

- Analyzing Roman numerals in contexts with nonchord tones; set class analysis where the segmentation is not given; analyzing form ("Evaluate")

- Schenkerian analysis; analytical essays ("Create")

A final complication for using Bloom verbs in music theory is that some of the most common music theoretical tasks, such as "harmonization," "sight singing," and "notate" are not represented in the verb list at all. Instructors are on their own to determine where these fit. Below, I present a method to aid in determining the most appropriate Bloom verb for common music theory tasks.

To identify where a given task falls on the Bloom chart, one must carefully determine the subskills involved, perhaps through listing them, rewording the task using only verbs from the Bloom chart (imagining that you can't say "harmonize," for example), or finding substitute verbs from the Bloom chart. Next, determine which of the subskills involved in the target task is the most leftward on the Bloom chart. Finally, reword the target task using a verb from the appropriate category. Additionally, it will be helpful to students and instructors alike if the traditional music theory verb also appears in the learning goal, perhaps in parentheses, to clarify instructor expectations. Example 2 shows some common music theory tasks articulated first with the traditional music theory verb and the most appropriate Bloom verb in parentheses.

Assignment-Level Learning Goals

Learning goals at the assignment level should use carefully chosen verbs and make the learning task as explicit as possible. The models above do this by including common music theory verbs that are not on Bloom lists, as well as a representative Bloom verb, and puts that verb in the second position of the learning goal. Michaelsen 2020 discusses ways to assess progress on learning goals using the concept of mastery learning. Below, I demonstrate how to revise existing learning goals, using examples from Daniel Stevens's keynote for the Pedagogy into Practice conference in May 2019.