Declaration of Independence

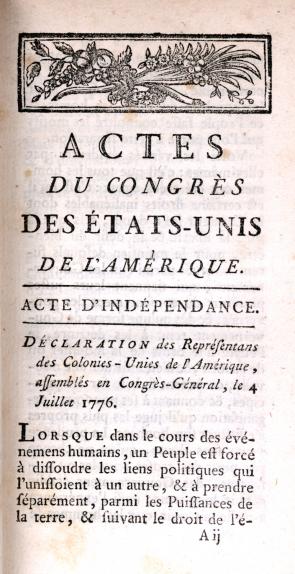

The Declaration of Independence is the foundational document of the United States of America. Written primarily by Thomas Jefferson, it explains why the Thirteen Colonies decided to separate from Great Britain during the American Revolution (1765-1789). It was adopted by the Second Continental Congress on 4 July 1776, the anniversary of which is celebrated in the US as Independence Day.

The Declaration was not considered a significant document until more than 50 years after its signing, as it was initially seen as a routine formality to accompany Congress' vote for independence. However, it has since become appreciated as one of the most important human rights documents in Western history. Largely influenced by Enlightenment ideals, particularly those of John Locke , the Declaration asserts that "all men are created equal" and are endowed with the "certain unalienable rights" to "Life, Liberty and the pursuit of happiness"; this has become one of the best-known statements in US history and has become a moral standard that the United States, and many other Western democracies, have since strived for. It has been cited in the push for the abolition of slavery and in many civil rights movements, and it continues to be a rallying cry for human rights to this day. Alongside the Articles of Confederation and the US Constitution, the Declaration of Independence was one of the most important documents to come out of the American Revolutionary era. This article includes a brief history of the factors that led the colonies to declare independence from Britain, as well as the complete text of the Declaration itself.

Road to Independence

For much of the early part of their struggle with Great Britain, most American colonists regarded independence as a final resort, if they even considered it at all. The argument between the colonists and the British Parliament, after all, largely boiled down to colonial identity within the British Empire ; the colonists believed that, as subjects of the British king and descendants of Englishmen, they were entitled to the same constitutional rights that governed the lives of those still in England . These rights, as expressed in the Magna Carta (1215), the Habeas Corpus Act of 1679, and the Bill of Rights of 1689, among other documents, were interpreted by the Americans to include self-taxation, representative government, and trial by jury. Englishmen exercised these rights through Parliament, which, at least theoretically, represented their interests; since the colonists were not represented in Parliament, they attempted to exercise their own 'rights of Englishmen' through colonial legislative assemblies such as Virginia's House of Burgesses .

Parliament, however, saw things differently. It agreed that the colonists were Britons and were subject to the same laws, but it viewed the colonists as no different than the 90% of Englishmen who owned no land and therefore could not vote, but who were nevertheless virtually represented in Parliament. Under this pretext, Parliament decided to directly tax the colonies and passed the Stamp Act in 1765. When the Americans protested that Parliament had no authority to tax them because they were not represented in Parliament, Parliament responded by passing the Declaratory Act (1766), wherein it proclaimed that it had the authority to pass binding legislation for all Britain's colonies "in all Cases whatsoever" (Middlekauff, 118). After doubling down, Parliament taxed the Americans once again with the Townshend Acts (1767-68). When these acts were met with riots in Boston, Parliament sent regiments of soldiers to restore the king's peace. This only led to acts of violence such as the Boston Massacre (5 March 1770) and acts of disobedience such as the Boston Tea Party (16 December 1773).

While the focal point of the argument regarded taxation, the Americans believed that their rights were being violated in other ways as well. As mandated in the so-called Intolerable Acts of 1774, Britain announced that American dissidents would now be tried by Vice-Admiralty courts or shipped to England for trial, thereby depriving them of a jury of peers; British soldiers could be quartered in American-owned buildings; and Massachusetts' representative government was to be suspended as punishment for the Boston Tea Party, with a military governor to be installed. Additionally, there was the question of land; both the Royal Proclamation of 1763 and the Quebec Act of 1774 restricted the westward expansion of Americans, who believed they were entitled to settle the West. While the colonies viewed themselves as separate polities within the British Empire and would not view themselves as a single entity for many years to come, they had nevertheless become bound together over the years due to their shared Anglo background and through their military cooperation during the last century of colonial wars with France. Their resistance to Parliament only tied them closer together and, after the passage of the Intolerable Acts, the colonies announced support for Massachusetts and began mobilizing their militias.

When the American Revolutionary War broke out in 1775, all thirteen colonies soon joined the rebellion and sent representatives to the Second Continental Congress, a provisional wartime government. Even at this late stage, independence was an idea espoused by only the most radical revolutionaries like Samuel Adams . Most colonists still believed that their quarrel was with Parliament alone, that King George III of Great Britain (r. 1760-1820) secretly supported them and would reconcile with them if given the opportunity; indeed, just before the Battle of Bunker Hill (17 June 1775), regiments of American rebels reported for duty by announcing that they were "in his Majesty's service" (Boatner, 539). In August 1775, King George III dispelled such notions when he issued his Proclamation of Rebellion, in which he announced that he considered the colonies to be in a state of rebellion and ordered British officials to endeavor to "withstand and suppress such rebellion". Indeed, George III would remain one of the biggest advocates of subduing the colonies with military force; it was after this moment that Americans began referring to him as a tyrant and hope of reconciliation with Britain diminished.

Writing the Declaration

By the spring of 1776, independence was no longer a radical idea; Thomas Paine 's widely circulated pamphlet Common Sense had made the prospect more appealing to the general public, while the Continental Congress realized that independence was necessary to procure military support from European nations. In March 1776, the revolutionary convention of North Carolina became the first to vote in favor of independence, followed by seven other colonies over the next two months. On 7 June, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia introduced a motion putting the idea of independence before Congress; the motion was so fiercely debated that Congress decided to postpone further discussion of Lee's motion for three weeks. In the meantime, a committee was appointed to draft a Declaration of Independence, in the event that Lee's motion passed. This five-man committee was comprised of Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, Robert R. Livingston of New York, John Adams of Massachusetts, Roger Sherman of Connecticut, and Thomas Jefferson of Virginia.

The Declaration was primarily authored by the 33-year-old Jefferson, who wrote it between 11 June and 28 June 1776 on the second floor of the Philadelphia home he was renting, now known as the Declaration House. Drawing heavily on the Enlightenment ideas of John Locke, Jefferson places the blame for American independence largely at the feet of the king, whom he accuses of having repeatedly violated the social contract between America and Great Britain. The Americans were declaring their independence, Jefferson asserts, only as a last resort to preserve their rights, having been continually denied redress by both the king and Parliament. Jefferson's original draft was revised and edited by the other men on the committee, and the Declaration was finally put before Congress on 1 July. By then, every colony except New York had authorized its congressional delegates to vote for independence, and on 4 July 1776, the Congress adopted the Declaration. It was signed by all 56 members of Congress; those who were not present on the day itself affixed their signatures later.

The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America. When in the course of human events it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to separation. Remove Ads Advertisement We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness. – That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, – That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive toward these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such a form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and, accordingly, all experience hath shewn that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security. – Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world. He has refused to Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good. He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing importance, unless suspended in their operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them. Remove Ads Advertisement He has refused to pass other Laws for the accommodation of large districts of people, unless those people would relinquish the right of Representation in the Legislature, a right inestimable to them and formidable to tyrants only. He has called together legislative bodies at places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the depository of their Public Records, for the sole purpose of fatiguing them into compliance with his measures. He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly firmness his invasions on the rights of the people. He has refused for a long time, after such dissolutions, to cause others to be elected; whereby the Legislative Powers, incapable of Annihilation, have returned to the People at large for their exercise; the State remaining in the mean time exposed to all the dangers of invasion from without, and convulsions within. Love History? Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter! He has endeavored to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws of Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither, and raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands. He has obstructed the Administration of Justice by refusing his Assent to Laws for establishing Judiciary Powers. He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone for the tenure of their offices, and the amount and payment of their salaries. He has erected a multitude of New Offices, and sent hither swarms of Officers to harass our people and eat out their substance. He has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures. He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil Power. He has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution, and unacknowledged by our laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation: For quartering large bodies of armed troops among us: For protecting them, by a mock Trial from punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States: For cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world: For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent: For depriving us in many cases, of the benefit of Trial by Jury: For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended offences: For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an Arbitrary government, and enlarging its Boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rules into these Colonies For taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable Laws and altering fundamentally the Forms of our Governments: For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with power to legislate for us in all cases whatsoever. He has abdicated Government here, be declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us. He has plundered our seas, ravaged our coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people. He is at this time transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the works of death , desolation, and tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty and Perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized nation. He has constrained our fellow Citizens taken Captive on the high Seas to bear Arms against their Country, to become the executioners of their friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their Hands. He has excited domestic insurrections against us, and has endeavored to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages whose known rule of warfare , is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes, and conditions. In every stage of these Oppressions We have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury. A Prince, whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people. Nor have We been wanting in attentions to our British brethren. We have warned them from time to time of attempts by their legislature to extend an unwarrantable jurisdiction over us. We have reminded them of the circumstances of our emigration and settlement here. We have appealed to their native justice and magnanimity, and we have conjured them by the ties of our common kindred to disavow these usurpations, which would inevitably interrupt our connections and correspondence. They too have been deaf to the voice of justice and of consanguinity. We must, therefore, acquiesce in the necessity, which denounces our Separation, and hold them, as we hold the rest of mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace Friends. We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, do, in the Name, and by the Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these united Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States, that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do. – And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of Divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes, and our sacred Honor.

The following is a list of the 56 men who signed the Declaration of Independence, many of whom are considered the Founding Fathers of the United States. John Hancock , as president of the Continental Congress, was the first to affix his signature. Robert R. Livingston was the only member of the original drafting committee to not also sign the Declaration, as he had been recalled to New York before the signing took place.

Massachusetts: John Hancock, Samuel Adams, John Adams, Robert Treat Paine, Elbridge Gerry.

New Hampshire: Josiah Bartlett, William Whipple, Matthew Thornton.

Rhode Island: Stephen Hopkins , William Ellery.

Connecticut: Roger Sherman, Samuel Huntington, William Williams, Oliver Wolcott.

New York: William Floyd, Philip Livingston, Francis Lewis, Lewis Morris.

New Jersey: Richard Stockton, John Witherspoon, Francis Hopkinson, John Hart, Abraham Clark.

Pennsylvania: Robert Morris, Benjamin Rush, Benjamin Franklin, John Morton, George Clymer, James Smith, George Taylor, James Wilson, George Ross.

Delaware: George Read, Caesar Rodney, Thomas McKean.

Maryland: Samuel Chase, William Paca, Thomas Stone, Charles Carroll of Carrollton.

Virginia: George Wythe, Richard Henry Lee, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Harrison, Thomas Nelson Jr., Francis Lightfoot Lee, Carter Braxton.

North Carolina: William Hooper, Joseph Hewes, John Penn.

South Carolina: Edward Rutledge, Thomas Heyward Jr., Thomas Lynch Jr., Arthur Middleton.

Georgia: Button Gwinnett, Lyman Hall, George Walton.

Subscribe to topic Bibliography Related Content Books Cite This Work License

Bibliography

- Boatner, Mark M. Cassell's Biographical Dictionary of the American War of Independence. London: Cassell, 1973., 1973.

- Britannica: Text of the Declaration of Independence Accessed 25 Mar 2024.

- Declaration of Independence - Signed, Writer, Date | HISTORY Accessed 25 Mar 2024.

- Declaration of Independence: A Transcription | National Archives Accessed 25 Mar 2024.

- Meacham, Jon. Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power. Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2013.

- Middlekauff, Robert. The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789. Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Wood, Gordon S. The Radicalism of the American Revolution. Vintage, 1993.

About the Author

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this article into another language!

Questions & Answers

What is the declaration of independence, who wrote the declaration of independence, who signed the declaration of independence, related content.

Second Continental Congress

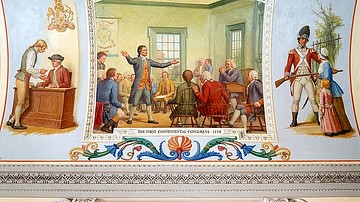

First Continental Congress

Natural Rights & the Enlightenment

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

The Enlightenment

Free for the world, supported by you.

World History Encyclopedia is a non-profit organization. For only $5 per month you can become a member and support our mission to engage people with cultural heritage and to improve history education worldwide.

Recommended Books

| , published by Penguin Workshop (2016) |

| , published by QuickStudy Reference Guides (2018) |

| , published by CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform (2016) |

| , published by Liveright (2015) |

| , published by Children's Press (2008) |

Cite This Work

Mark, H. W. (2024, April 03). Declaration of Independence . World History Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/article/2411/declaration-of-independence/

Chicago Style

Mark, Harrison W.. " Declaration of Independence ." World History Encyclopedia . Last modified April 03, 2024. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/2411/declaration-of-independence/.

Mark, Harrison W.. " Declaration of Independence ." World History Encyclopedia . World History Encyclopedia, 03 Apr 2024. Web. 26 Jun 2024.

License & Copyright

Submitted by Harrison W. Mark , published on 03 April 2024. The copyright holder has published this content under the following license: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike . This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon this content non-commercially, as long as they credit the author and license their new creations under the identical terms. When republishing on the web a hyperlink back to the original content source URL must be included. Please note that content linked from this page may have different licensing terms.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Declaration of Independence

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 25, 2024 | Original: October 27, 2009

The Declaration of Independence was the first formal statement by a nation’s people asserting their right to choose their own government.

When armed conflict between bands of American colonists and British soldiers began in April 1775, the Americans were ostensibly fighting only for their rights as subjects of the British crown. By the following summer, with the Revolutionary War in full swing, the movement for independence from Britain had grown, and delegates of the Continental Congress were faced with a vote on the issue. In mid-June 1776, a five-man committee including Thomas Jefferson , John Adams and Benjamin Franklin was tasked with drafting a formal statement of the colonies’ intentions. The Congress formally adopted the Declaration of Independence—written largely by Jefferson—in Philadelphia on July 4 , a date now celebrated as the birth of American independence.

America Before the Declaration of Independence

Even after the initial battles in the Revolutionary War broke out, few colonists desired complete independence from Great Britain, and those who did–like John Adams– were considered radical. Things changed over the course of the next year, however, as Britain attempted to crush the rebels with all the force of its great army. In his message to Parliament in October 1775, King George III railed against the rebellious colonies and ordered the enlargement of the royal army and navy. News of his words reached America in January 1776, strengthening the radicals’ cause and leading many conservatives to abandon their hopes of reconciliation. That same month, the recent British immigrant Thomas Paine published “Common Sense,” in which he argued that independence was a “natural right” and the only possible course for the colonies; the pamphlet sold more than 150,000 copies in its first few weeks in publication.

Did you know? Most Americans did not know Thomas Jefferson was the principal author of the Declaration of Independence until the 1790s; before that, the document was seen as a collective effort by the entire Continental Congress.

In March 1776, North Carolina’s revolutionary convention became the first to vote in favor of independence; seven other colonies had followed suit by mid-May. On June 7, the Virginia delegate Richard Henry Lee introduced a motion calling for the colonies’ independence before the Continental Congress when it met at the Pennsylvania State House (later Independence Hall) in Philadelphia. Amid heated debate, Congress postponed the vote on Lee’s resolution and called a recess for several weeks. Before departing, however, the delegates also appointed a five-man committee–including Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, John Adams of Massachusetts, Roger Sherman of Connecticut, Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania and Robert R. Livingston of New York–to draft a formal statement justifying the break with Great Britain. That document would become known as the Declaration of Independence.

Thomas Jefferson Writes the Declaration of Independence

Jefferson had earned a reputation as an eloquent voice for the patriotic cause after his 1774 publication of “A Summary View of the Rights of British America,” and he was given the task of producing a draft of what would become the Declaration of Independence. As he wrote in 1823, the other members of the committee “unanimously pressed on myself alone to undertake the draught [sic]. I consented; I drew it; but before I reported it to the committee I communicated it separately to Dr. Franklin and Mr. Adams requesting their corrections….I then wrote a fair copy, reported it to the committee, and from them, unaltered to the Congress.”

As Jefferson drafted it, the Declaration of Independence was divided into five sections, including an introduction, a preamble, a body (divided into two sections) and a conclusion. In general terms, the introduction effectively stated that seeking independence from Britain had become “necessary” for the colonies. While the body of the document outlined a list of grievances against the British crown, the preamble includes its most famous passage: “We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.”

The Continental Congress Votes for Independence

The Continental Congress reconvened on July 1, and the following day 12 of the 13 colonies adopted Lee’s resolution for independence. The process of consideration and revision of Jefferson’s declaration (including Adams’ and Franklin’s corrections) continued on July 3 and into the late morning of July 4, during which Congress deleted and revised some one-fifth of its text. The delegates made no changes to that key preamble, however, and the basic document remained Jefferson’s words. Congress officially adopted the Declaration of Independence later on the Fourth of July (though most historians now accept that the document was not signed until August 2).

The Declaration of Independence became a significant landmark in the history of democracy. In addition to its importance in the fate of the fledgling American nation, it also exerted a tremendous influence outside the United States, most memorably in France during the French Revolution . Together with the Constitution and the Bill of Rights , the Declaration of Independence can be counted as one of the three essential founding documents of the United States government.

HISTORY Vault

Stream thousands of hours of acclaimed series, probing documentaries and captivating specials commercial-free in HISTORY Vault

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Library of Congress

Exhibitions.

- Ask a Librarian

- Digital Collections

- Library Catalogs

- Exhibitions Home

- Current Exhibitions

- All Exhibitions

- Loan Procedures for Institutions

- Special Presentations

Thomas Jefferson Declaration of Independence: Right to Institute New Government

Through the many revisions made by Jefferson, the committee, and then by Congress, Jefferson retained his prominent role in writing the defining document of the American Revolution and, indeed, of the United States. Jefferson was critical of changes to the document, particularly the removal of a long paragraph that attributed responsibility of the slave trade to British King George III. Jefferson was justly proud of his role in writing the Declaration of Independence and skillfully defended his authorship of this hallowed document.

Influential Precedents

Instructions to virginia's delegates to the first continental congress written by thomas jefferson in 1774.

Thomas Jefferson, a delegate to the Virginia Convention from Albemarle County, drafted these instructions for the Virginia delegates to the first Continental Congress. Although considered too radical by the Virginia Convention, Jefferson's instructions were published by his friends in Williamsburg. His ideas and smooth, eloquent language contributed to his selection as draftsman of the Declaration of Independence. This manuscript copy contains additional sections and lacks others present in the published version, A Summary View of the Rights of British America.

Thomas Jefferson. Instructions to Virginia's Delegates, 1774. Manuscript. Manuscript Division (39)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#039

Fairfax County Resolves, July 18, 1774

The Fairfax County Resolves were written by George Mason (1725–1792) and George Washington (1732/33–1799) and adopted by a Fairfax County Convention chaired by Washington and called to protest Britain's harsh measures against Boston. The resolves are a clear statement of constitutional rights considered to be fundamental to Britain's American colonies. The Resolves call for a halt to trade with Great Britain, including an end to the importation of slaves. Jefferson tried unsuccessfully to include in the Declaration of Independence a condemnation of British support of the slave trade.

George Mason and George Washington. Fairfax County Resolves, 1774. Manuscript. Manuscript Division (40)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#040

George Mason's Virginia Declaration of Rights

The Virginia Declaration of Rights was drafted by George Mason and Thomas Ludwell Lee (1730–1778) and adopted unanimously in June 1776 during the Virginia Convention in Williamsburg that propelled America to independence. It is one of the documents heavily relied on by Thomas Jefferson in drafting the Declaration of Independence. The Virginia Declaration of Rights can be seen as the fountain from which flowed the principles embodied in the Declaration of Independence, the Virginia Constitution, and the Bill of Rights. The document exhibited here is Mason's first draft to which Thomas Ludwell Lee added several clauses. Even a cursory examination of Mason's and Jefferson's declarations reveal the commonality of language and principle.

George Mason and Thomas Ludwell Lee. Draft of the Virginia Declaration of Rights, 1776. Manuscript. Manuscript Division (41)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#041

Thomas Jefferson's Draft of a Constitution for Virginia, predecessor of The Declaration Of Independence

Immediately on learning that the Virginia Convention had called for independence on May 15, 1776, Jefferson, a Virginia delegate to the Continental Congress, wrote at least three drafts of a Virginia constitution. Jefferson's drafts are not only important for their influence on the Virginia government, they are direct predecessors of the Declaration of Independence. Shown here is Jefferson's litany of governmental abuses by King George III as it appeared in his first draft.

Thomas Jefferson. Draft of Virginia Constitution, 1776. Manuscript. Manuscript Division (45)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#045

The Fragment

Fragment of the earliest known draft of the declaration, june, 1776.

This is the only surviving fragment of the earliest draft of the Declaration of Independence. This fragment demonstrates that Jefferson heavily edited his first draft of the Declaration of Independence before he prepared a fair copy that became the basis of “the original Rough draught.” None of the deleted words and passages in this fragment appears in the “Rough draught,” but all of the undeleted 148 words, including those careted and interlined, were copied into the “Rough draught” in a clear form.

Thomas Jefferson. Draft fragment of the Declaration of Independence, 1776, Manuscript. Manuscript Division (48)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#048

The Rough Draft

Original rough draft of the declaration.

Written in June 1776, Thomas Jefferson's draft of the Declaration of Independence, included eighty-six changes made later by John Adams (1735–1826), Benjamin Franklin 1706–1790), other members of the committee appointed to draft the document, and by Congress. The “original Rough draught” of the Declaration of Independence, one of the great milestones in American history, shows the evolution of the text from the initial composition draft by Jefferson to the final text adopted by Congress on the morning of July 4, 1776. At a later date perhaps in the nineteenth century, Jefferson indicated in the margins some but not all of the corrections suggested by Adams and Franklin. Late in life Jefferson endorsed this document: “Independence Declaration of original Rough draught.”

Thomas Jefferson. Draft of Declaration of Independence, 1776. Manuscript. Manuscript Division (49)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#049

Back to top

The Graff House where Jefferson drafted the Declaration of Independence

The house of Jacob Graff, brick mason, located at the southwest corner of Market and Seventh Street, Philadelphia, was the residence of Thomas Jefferson when he drafted the Declaration of Independence. The three-story brick house is pictured here in Harper's Weekly, April 7, 1883. Jefferson rented the entire second floor for himself and his household staff.

Harper's Weekly, April 7, 1883. Reproduction of journal page. Prints and Photographs Division (43)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#043

Submitting the Declaration of Independence to the Continental Congress, June 28, 1776

This image is considered one of the most realistic renditions of this historical event. Jefferson is the tall person depositing the Declaration of Independence on the table. Benjamin Franklin sits to his right. John Hancock (1737–1793) sits behind the table. Fellow committee members, John Adams, Roger Sherman (1721–1793), and Robert R. Livingston (1746–1813) stand (left to right) behind Jefferson.

Edward Savage and/or Robert Edge Pine. Congress Voting the Declaration of Independence, c. 1776. Copyprint of oil on canvas, Courtesy of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania (53)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#053

The “Declaration Committee,” chaired by Thomas Jefferson

On June 11, 1776, anticipating that the vote for independence would be favorable, Congress appointed a committee to draft a declaration: Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, Roger Sherman of Connecticut, Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, Robert R. Livingston of New York, and John Adams of Massachusetts. Currier and Ives prepared this imagined scene for the one hundredth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence.

Currier and Ives. The Declaration Committee, New York, 1876. Copyprint of lithograph. Prints and Photographs Division (56)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#056

The Final Document

George washington's copy of the declaration of independence.

This is the surviving fragment of John Dunlap's initial printing of the Declaration of Independence, which was sent to George Washington by John Hancock, president of the Continental Congress on July 6, 1776. General Washington had the Declaration read to his assembled troops in New York on July 9. Later that night the Americans destroyed a bronze statue of Great Britain's King George III, which stood at the foot of Broadway on the Bowling Green.

[ In Congress, July 4, 1776. A Declaration By the Representatives of the United States of America, In General Congress Assembled. ] [Philadelphia: John Dunlap, July 4, 1776]. Broadside with broken at lines 34 and 54 with text below line 54 missing. Manuscript Division (51)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#051

Independence Hall

Congress voted for Independence in the Pennsylvania State House located on Chestnut Street between Fifth and Sixth Streets. Charles Willson Peale painted this northwest view of the state house and its sheds in 1778. The building was ornamented by two clocks and a steeple, which was removed shortly after the British left Philadelphia in 1778.

James Trenchard after a painting by Charles Willson Peale. A NW View of the State House in Philadelphia in Columbian Magazine, 1787. Copyprint of engraving. Rare Book & Special Collections Division (44)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#044

Prospect of Philadelphia

This is a view of the city of Philadelphia in 1768 from the Jersey shore, with a street map and an enlarged engraving of the State House and the River Battery. Jefferson would have seen Philadelphia, as depicted, when he visited Annapolis, Philadelphia, and New York in 1766. The Philadelphia skyline had not dramatically changed when Jefferson returned in 1775.

George Heap under the direction of Nicholas Scull, surveyor general of Pennsylvania. Prospect of the City of Philadelphia, 1768. Copyprint of map and engraving. Prints and Photographs Division (6)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#006

Destroying the statue of King George III

After hearing the Declaration of Independence read on July 9, the American army destroyed the statue of King George III at the foot of Broadway on the Bowling Green in New York City.

John C. McRae after Johnannes A. Oertel. Pulling down the statue of George III by the “Sons of Freedom,” at the Bowling Green, City of New York, July 1776. New York : Published by Joseph Laing, [ca. 1875] Copyprint of engraving. Prints and Photographs Division (52)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#052

First public reading of the Declaration of Independence

Pennsylvania militia colonel John Nixon (1733–1808) is portrayed in the first public reading of the Declaration of Independence on July 6, 1776. This scene was created by William Hamilton after a drawing by George Noble and appeared in Edward Barnard, History of England (London, 1783).

The Manner in Which the American Colonies Declared Themselves Independent of the King of England, Throughout the Different Provinces, on July 4, 1776. Copyprint of etching. Prints and Photographs Division (57)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#057

The Aftermath

Jefferson's draft of the declaration of independence, as reported to congress.

This copy of the Declaration represents the fair copy that the committee presented to Congress. Jefferson noted that “the parts struck out by Congress shall be distinguished by a black line drawn under them, & those inserted by them shall be placed in the margin or in a concurrent column.” Despite its importance in the story of the evolution of the text, this copy of the Declaration has received very little public attention.

Thomas Jefferson. Draft of Declaration of Independence, 1776. Manuscript. //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/images/vc50p2.jpg ">Page 2 . //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/images/vc50p3.jpg ">Page 3 . //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/images/vc50p4.jpg ">Page 4 . Manuscript Division (50)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#050

Jefferson consoled for his “mangled” manuscript

Thomas Jefferson sent copies of the Declaration of Independence to a few close friends, such as Richard Henry Lee (1732–1794), indicating the changes that had been made by Congress. Lee, replied: “I wish sincerely, as well for the honor of Congress, as for that of the States, that the Manuscript had not been mangled as it is. It is wonderful, and passing pitiful, that the rage of change should be so unhappily applied. However the Thing is in its nature so good, that no Cookery can spoil the Dish for the palates of Freemen.”

Richard Henry Lee to Thomas Jefferson, July 21, 1776. Manuscript letter. Manuscript Division (54)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#054

The Goddess Of Liberty

In this allegorical print, the Goddess of Liberty points to Thomas Jefferson's portrait while gazing at the portrait of George Washington. It was made late in Jefferson's second presidential administration. The cupids here are the Genius of Peace and the Genius of Gratitude, and in this context Jefferson is “Liberty's Genius.”

The Goddess of Liberty with a Portrait of Thomas Jefferson, Salem, Massachusetts, January 15, 1807. Copyprint of painting. Courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery, the Mabel Brady Garvan Collection (32)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#032

Thomas Jefferson's portable writing desk

The Declaration of Independence was composed on this mahogany lap desk, designed by Jefferson and built by Philadelphia cabinet maker Benjamin Randolph. Jefferson gave it to Joseph Coolidge, Jr. (1798–1879) when he married Ellen Randolph, Jefferson's granddaughter. In giving it, Jefferson wrote on November 18, 1825: “Politics, as well as Religion, has it's superstitions. These, gaining strength with time, may, one day give imaginary value to this relic, for it's association with the birth of the Great Charter of our Independence.” Coolidge replied, on February 27, 1826, that he would consider the desk “no longer inanimate, and mute, but as something to be interrogated and caressed.”

Benjamin Randolph after a design by Thomas Jefferson. Portable writing desk, Philadelphia, 1776. Courtesy of the National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution (30)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#030

Thomas Jefferson's monogrammed silver pen

Thomas Jefferson ordered this small cylindrical silver fountain pen with a gold nib from his agent in Richmond, Virginia. It was probably made by William Cowan (1779–1831), a Richmond watchmaker. An elliptical cap that screws into the end of the cylinder and caps the ink reservoir is engraved “TJ”.

Probably by William Cowan. Silver pen, Richmond, Virginia, c.1824. Courtesy of the Monticello, Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation, Inc. (31)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#031

Lord Kames, Henry Home, Essays on the Principles of Morality and Natural Religion

This is Jefferson's personal copy of the Scottish moral philosopher's work and is one of the few books annotated by Jefferson. Lord Kames (1696–1782) was a leader of the “moral sense” school, that advocated that men had an inner sense of right and wrong. Lord Kames provided the philosophical foundation of the phrase “pursuit of happiness,” which was appropriated by Jefferson as an inalienable right of mankind in the Declaration of Independence.

Lord Kames (Henry Home). Essays on the Principles of Morality and Natural Religion. Two parts. Edinburgh: R. Fleming, for A. Kincaid and A. Donaldson, 1751. Rare Book and Special Collections Division (34)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#034

Algernon Sidney, Discourses Concerning Government

Jefferson considered Algernon Sidney's (1622–1683) Discourses the best fundamental textbook on the principles of government. In a December 13, 1804 letter to Mason Weems, Jefferson commented that “they are in truth a rich treasure of republican principles . . . it is probably the best elementary book of the principles of government.” Sidney was a republican executed by the British for seditious writings including the Discourses. This is Jefferson's personal copy which was sold to Congress in 1815.

Algernon Sidney. Discourses Concerning Government by Algernon Sidney with his Letters, Trial Apology and some Memoirs of His Life. London: Printed for A. Millar, 1763. Rare Book and Special Collections Division (35)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#035

Liberty And Science

Thomas Jefferson is pictured, at the beginning of his first presidential term, holding the Declaration of Independence with scientific instruments in the background. Tiebout used the bust portrait of Rembrandt Peale and created an imaginary full-body, because no standing portrait of Jefferson had been painted.

Cornelius Tiebout. Thomas Jefferson: President of the United States, Philadelphia, 1801. Copyprint of engraving. Prints and Photographs Division (95)

Bookmark this item: //www.loc.gov/exhibits/jefferson/jeffdec.html#095

Connect with the Library

All ways to connect

Subscribe & Comment

- RSS & E-Mail

Download & Play

- iTunesU (external link)

About | Press | Jobs | Donate Inspector General | Legal | Accessibility | External Link Disclaimer | USA.gov

- Utility Menu

Text of the Declaration of Independence

Note: The source for this transcription is the first printing of the Declaration of Independence, the broadside produced by John Dunlap on the night of July 4, 1776. Nearly every printed or manuscript edition of the Declaration of Independence has slight differences in punctuation, capitalization, and even wording. To find out more about the diverse textual tradition of the Declaration, check out our Which Version is This, and Why Does it Matter? resource.

WHEN in the Course of human Events, it becomes necessary for one People to dissolve the Political Bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the Powers of the Earth, the separate and equal Station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent Respect to the Opinions of Mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the Separation. We hold these Truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness—-That to secure these Rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just Powers from the Consent of the Governed, that whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these Ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its Foundation on such Principles, and organizing its Powers in such Form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient Causes; and accordingly all Experience hath shewn, that Mankind are more disposed to suffer, while Evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the Forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long Train of Abuses and Usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object, evinces a Design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their Right, it is their Duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future Security. Such has been the patient Sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the Necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The History of the present King of Great-Britain is a History of repeated Injuries and Usurpations, all having in direct Object the Establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid World. He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public Good. He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing Importance, unless suspended in their Operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them. He has refused to pass other Laws for the Accommodation of large Districts of People, unless those People would relinquish the Right of Representation in the Legislature, a Right inestimable to them, and formidable to Tyrants only. He has called together Legislative Bodies at Places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the Depository of their public Records, for the sole Purpose of fatiguing them into Compliance with his Measures. He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly Firmness his Invasions on the Rights of the People. He has refused for a long Time, after such Dissolutions, to cause others to be elected; whereby the Legislative Powers, incapable of Annihilation, have returned to the People at large for their exercise; the State remaining in the mean time exposed to all the Dangers of Invasion from without, and Convulsions within. He has endeavoured to prevent the Population of these States; for that Purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their Migrations hither, and raising the Conditions of new Appropriations of Lands. He has obstructed the Administration of Justice, by refusing his Assent to Laws for establishing Judiciary Powers. He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone, for the Tenure of their Offices, and the Amount and Payment of their Salaries. He has erected a Multitude of new Offices, and sent hither Swarms of Officers to harrass our People, and eat out their Substance. He has kept among us, in Times of Peace, Standing Armies, without the consent of our Legislatures. He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil Power. He has combined with others to subject us to a Jurisdiction foreign to our Constitution, and unacknowledged by our Laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation: For quartering large Bodies of Armed Troops among us: For protecting them, by a mock Trial, from Punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States: For cutting off our Trade with all Parts of the World: For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent: For depriving us, in many Cases, of the Benefits of Trial by Jury: For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended Offences: For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an arbitrary Government, and enlarging its Boundaries, so as to render it at once an Example and fit Instrument for introducing the same absolute Rule into these Colonies: For taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable Laws, and altering fundamentally the Forms of our Governments: For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with Power to legislate for us in all Cases whatsoever. He has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us. He has plundered our Seas, ravaged our Coasts, burnt our Towns, and destroyed the Lives of our People. He is, at this Time, transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the Works of Death, Desolation, and Tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty and Perfidy, scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous Ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized Nation. He has constrained our fellow Citizens taken Captive on the high Seas to bear Arms against their Country, to become the Executioners of their Friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their Hands. He has excited domestic Insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the Inhabitants of our Frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known Rule of Warfare, is an undistinguished Destruction, of all Ages, Sexes and Conditions. In every stage of these Oppressions we have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble Terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated Injury. A Prince, whose Character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the Ruler of a free People. Nor have we been wanting in Attentions to our British Brethren. We have warned them from Time to Time of Attempts by their Legislature to extend an unwarrantable Jurisdiction over us. We have reminded them of the Circumstances of our Emigration and Settlement here. We have appealed to their native Justice and Magnanimity, and we have conjured them by the Ties of our common Kindred to disavow these Usurpations, which, would inevitably interrupt our Connections and Correspondence. They too have been deaf to the Voice of Justice and of Consanguinity. We must, therefore, acquiesce in the Necessity, which denounces our Separation, and hold them, as we hold the rest of Mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace, Friends. We, therefore, the Representatives of the UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the World for the Rectitude of our Intentions, do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly Publish and Declare, That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be, Free and Independent States; that they are absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political Connection between them and the State of Great-Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do. And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm Reliance on the Protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes, and our sacred Honor.

Signed by Order and in Behalf of the Congress, JOHN HANCOCK, President.

Attest. CHARLES THOMSON, Secretary.

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Course: US history > Unit 11

The declaration of independence.

- The Articles of Confederation

- The Constitution of the United States

- Frederick Douglass, "What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?"

- Letter from a Birmingham Jail

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

Declaration of Independence Causes and Effects

America's Founding Documents

Declaration of Independence: A Transcription

Note: The following text is a transcription of the Stone Engraving of the parchment Declaration of Independence (the document on display in the Rotunda at the National Archives Museum .) The spelling and punctuation reflects the original.

In Congress, July 4, 1776

The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America, When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.--That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, --That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.--Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world.

He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good.

He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing importance, unless suspended in their operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them.

He has refused to pass other Laws for the accommodation of large districts of people, unless those people would relinquish the right of Representation in the Legislature, a right inestimable to them and formidable to tyrants only.

He has called together legislative bodies at places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the depository of their public Records, for the sole purpose of fatiguing them into compliance with his measures.

He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly firmness his invasions on the rights of the people.

He has refused for a long time, after such dissolutions, to cause others to be elected; whereby the Legislative powers, incapable of Annihilation, have returned to the People at large for their exercise; the State remaining in the mean time exposed to all the dangers of invasion from without, and convulsions within.

He has endeavoured to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither, and raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands.

He has obstructed the Administration of Justice, by refusing his Assent to Laws for establishing Judiciary powers.

He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone, for the tenure of their offices, and the amount and payment of their salaries.

He has erected a multitude of New Offices, and sent hither swarms of Officers to harrass our people, and eat out their substance.

He has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures.

He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil power.

He has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution, and unacknowledged by our laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation:

For Quartering large bodies of armed troops among us:

For protecting them, by a mock Trial, from punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States:

For cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world:

For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent:

For depriving us in many cases, of the benefits of Trial by Jury:

For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended offences

For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an Arbitrary government, and enlarging its Boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these Colonies:

For taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable Laws, and altering fundamentally the Forms of our Governments:

For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with power to legislate for us in all cases whatsoever.

He has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us.

He has plundered our seas, ravaged our Coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people.

He is at this time transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the works of death, desolation and tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty & perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized nation.

He has constrained our fellow Citizens taken Captive on the high Seas to bear Arms against their Country, to become the executioners of their friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their Hands.

He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.

In every stage of these Oppressions We have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury. A Prince whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people.

Nor have We been wanting in attentions to our Brittish brethren. We have warned them from time to time of attempts by their legislature to extend an unwarrantable jurisdiction over us. We have reminded them of the circumstances of our emigration and settlement here. We have appealed to their native justice and magnanimity, and we have conjured them by the ties of our common kindred to disavow these usurpations, which, would inevitably interrupt our connections and correspondence. They too have been deaf to the voice of justice and of consanguinity. We must, therefore, acquiesce in the necessity, which denounces our Separation, and hold them, as we hold the rest of mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace Friends.

We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States; that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do. And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.

Button Gwinnett

George Walton

North Carolina

William Hooper

Joseph Hewes

South Carolina

Edward Rutledge

Thomas Heyward, Jr.

Thomas Lynch, Jr.

Arthur Middleton

Massachusetts

John Hancock

Samuel Chase

William Paca

Thomas Stone

Charles Carroll of Carrollton

George Wythe

Richard Henry Lee

Thomas Jefferson

Benjamin Harrison

Thomas Nelson, Jr.

Francis Lightfoot Lee

Carter Braxton

Pennsylvania

Robert Morris

Benjamin Rush

Benjamin Franklin

John Morton

George Clymer

James Smith

George Taylor

James Wilson

George Ross

Caesar Rodney

George Read

Thomas McKean

William Floyd

Philip Livingston

Francis Lewis

Lewis Morris

Richard Stockton

John Witherspoon

Francis Hopkinson

Abraham Clark

New Hampshire

Josiah Bartlett

William Whipple

Samuel Adams

Robert Treat Paine

Elbridge Gerry

Rhode Island

Stephen Hopkins

William Ellery

Connecticut

Roger Sherman

Samuel Huntington

William Williams

Oliver Wolcott

Matthew Thornton

Back to Main Declaration Page

Background Essay: Applying the Ideals of the Declaration of Independence

Guiding Questions: Why have Americans consistently appealed to the Declaration of Independence throughout U.S. history? How have the ideals in the Declaration of Independence affected the struggle for equality throughout U.S. history?

- I can explain how the ideals of the Declaration of Independence have inspired individuals and groups to make the United States a more equal and just society.

Essential Vocabulary

| to point to as evidence | |

| understand | |

| gave | |

| created | |

| a list released by Seneca Falls of injustices committed against women | |

| receiving | |

| an infamous Supreme Court decision that ruled the Constitution was not meant to allow Blacks to become citizens in the United States | |

| given | |

| to inherit | |

| given up | |

| 87 years | |

| impossible to take away | |

| a permanent quality | |

| established | |

| for no reason | |

| a fundamental principle | |

| goal | |

| pass away | |

| bringing complaints to the government | |

| a political and social reform group that began in the late 19th century | |

| a signed promise to pay money to someone | |

| idea | |

| the ability of the people to govern their country without foreign involvement | |

| obvious | |

| the first women’s rights convention held in the United States | |

| possessing ultimate power | |

| a war that brought the United States into more involvement in world affairs | |

| impossible to take away | |

| violations |

In an 1857 speech criticizing the Supreme Court decision in Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857), Abraham Lincoln commented that the principle of equality in the Declaration of Independence was “meant to set up a standard maxim [fundamental principle] for a free society.” Indeed, throughout American history, many Americans appealed to the ideals of the Declaration of Independence to make liberty and equality a reality for all.

A constitutional democracy requires vigorous deliberation and debate by citizens and their representatives. Therefore, it should not be surprising that the meanings and implications of the Declaration of Independence and its principles have been debated and contested throughout history. This civil and political dialogue helps Americans understand the principles and ideas upon which their country was founded and the means of working to achieve them.

Applying the Declaration of Independence from the Founding through the Civil War

Individuals appealed [pointed to as evidence] to the principles of the Declaration of Independence soon after it was signed. In the 1770s and 1780s, enslaved people in New England appealed to the natural rights principles of the Declaration and state constitutions as they petitioned legislatures and courts for freedom and the abolition of slavery. A group of enslaved people in New Hampshire stated, “That the God of Nature, gave them, Life, and Freedom, upon the Terms of the most perfect Equality with other men; That Freedom is an inherent [of a permanent quality] Right of the human Species, not to be surrendered, but by Consent.” While some of these petitions were unsuccessful, others led to freedom for the petitioner.

The women and men who assembled at the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention , the first women’s rights conference held in the United States, adopted the Declaration of Sentiments and Resolutions , a list of injustices committed against women. The document was modeled after the Declaration of Independence, but the language was changed to read, “We hold these truths to be self-evident : [clear without having to be stated] that all men and women are created equal.” It then listed several grievances regarding the inequalities that women faced. The document served as a guiding star in the long struggle for women’s suffrage.

The Declaration of Independence was one of the centerpieces of the national debate over slavery. Abolitionists such as Frederick Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison, and Abby Kelley all invoked the Declaration of Independence in denouncing slavery. On the other hand, Senators Stephen Douglas and John Calhoun, Justice Roger Taney, and Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens all denied that the Declaration of Independence was meant to apply to Black people.

Abraham Lincoln was president during the crisis of the Civil War, which was brought about by this national debate over slavery. He consistently held that the Declaration of Independence had universal natural rights principles that were “applicable to all men and all time.” In his Gettysburg Address, Lincoln stated that the nation was “conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.”

The Declaration at Home and Abroad: The Twentieth Century and Beyond

The case of Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) revealed a split over the meaning of the equality principle even in the Supreme Court. The majority in the 7–1 decision thought that distinctions and inequalities based upon race did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment and did not imply inferiority, and therefore, segregation was constitutional. Dissenting Justice John Marshall Harlan argued for equality when he famously wrote, “In the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our constitution is colorblind.”

The expansion of American world power in the wake of the Spanish-American War of 1898 triggered another debate inspired by the Declaration of Independence. The war brought the United States into more involvement in world affairs. Echoing earlier debates over Manifest Destiny during nineteenth-century westward expansion, supporters of American global expansion argued that the country would bring the ideals of liberty and self-government to those people who had not previously enjoyed them. On the other hand, anti-imperialists countered that creating an American empire violated the Declaration of Independence by taking away the liberty of self-determination , or freedom of government without foreign interference, and consent from Filipinos and Cubans.

Politicians of differing perspectives viewed the Declaration in opposing ways during the early twentieth century. Progressives [a political and social reform group that began in the late 19th century] such as Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson argued that the principles of the Declaration of Independence were important for an earlier period in American history, to gain independence from Great Britain and to set up the new nation. They argued that the modern United States faced new challenges introduced by an industrial economy and needed a new set of ideas that required a more active government and more powerful national executive. They were less concerned with preserving an ideal of liberty and equality and more concerned with regulating society and the economy for the public interest. Wilson in particular rejected the views of the Founding, criticizing both the Declaration and the Constitution as irrelevant for facing the problems of his time.

President Calvin Coolidge disagreed and adopted a conservative position when he argued that the ideals of the Declaration of Independence should be preserved and respected. On the 150th anniversary of the Declaration, Coolidge stated that the principles formed the American belief system and were still the basis of American republican institutions. They were still applicable regardless of how much society had changed.

During World War II, Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan threatened the free nations of the world with aggressive expansion and domination. The United States and the coalition of Allied powers fought for several years to reverse their conquests. President Franklin Roosevelt and other free-world leaders proclaimed the principles of liberty and self-government from the Declaration of Independence in documents such as the Atlantic Charter , the Four Freedoms speech, and the United Nations Charter.

After World War II, American social movements for justice and equality called upon the Declaration of Independence and its principles. For example, in his “I Have a Dream” speech, Martin Luther King, Jr., referred to the Declaration as the “sacred heritage” of the nation but said that it had not lived up to its ideals for Black Americans. King demanded that the United States live up to its “sacred obligation” of liberty and equality for all.

The natural rights republican ideals of the Declaration of Independence influenced the creation of American constitutional government founded upon liberty and equality. They also shaped the expectation that a free people would live in a just society. Indeed, the Declaration states that to secure natural rights is the fundamental duty of government. Achieving those ideals has always been part of a robust and dynamic debate among the sovereign people and their representatives.

Inspired by the ideals of the Declaration of Independence, many social movements, politicians, and individuals helped make the United States a more equal and just society. The Emancipation Proclamation ; the Thirteenth , Fourteenth , and Fifteenth Amendments ; the Nineteenth Amendment ; the 1964 Civil Rights Act ; and the 1965 Voting Rights Act were only some of the achievements in the name of equality and justice. As James Madison wrote in Federalist 51 , “Justice is the end of government. It is the end of civil society. It ever has been and ever will be pursued until it be obtained.”

Related Content

Graphic Organizer: The Declaration of Independence and Equality in U.S. History

Documents: The Declaration of Independence and Equality in U.S. History

The Guiding Star of Equality: The Declaration of Independence and Equality in U.S. History Answer Key

Self-Paced Courses : Explore American history with top historians at your own time and pace!

- AP US History Study Guide

- History U: Courses for High School Students

- History School: Summer Enrichment

- Lesson Plans

- Classroom Resources

- Spotlights on Primary Sources

- Professional Development (Academic Year)

- Professional Development (Summer)

- Book Breaks

- Inside the Vault

- Self-Paced Courses

- Browse All Resources

- Search by Issue

- Search by Essay

- Become a Member (Free)

- Monthly Offer (Free for Members)

- Program Information

- Scholarships and Financial Aid

- Applying and Enrolling

- Eligibility (In-Person)

- EduHam Online

- Hamilton Cast Read Alongs

- Official Website

- Press Coverage

- Veterans Legacy Program

- The Declaration at 250

- Black Lives in the Founding Era

- Celebrating American Historical Holidays

- Browse All Programs

- Donate Items to the Collection

- Search Our Catalog

- Research Guides

- Rights and Reproductions

- See Our Documents on Display

- Bring an Exhibition to Your Organization

- Interactive Exhibitions Online

- About the Transcription Program

- Civil War Letters

- Founding Era Newspapers

- College Fellowships in American History

- Scholarly Fellowship Program

- Richard Gilder History Prize

- David McCullough Essay Prize

- Affiliate School Scholarships

- Nominate a Teacher

- Eligibility

- State Winners

- National Winners

- Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize

- Gilder Lehrman Military History Prize

- George Washington Prize

- Frederick Douglass Book Prize

- Our Mission and History

- Annual Report

- Contact Information

- Student Advisory Council

- Teacher Advisory Council

- Board of Trustees

- Remembering Richard Gilder

- President's Council

- Scholarly Advisory Board

- Internships

- Our Partners

- Press Releases

History Resources

The Declaration of Independence in Global Perspective

By david armitage.

The Declaration was addressed as much to "mankind" as it was to the population of the colonies. In the opening paragraph, the authors of the Declaration—Thomas Jefferson, the five-member Congressional committee of which he was part, and the Second Continental Congress itself—addressed "the opinions of Mankind" as they announced the necessity for

. . . one People to dissolve the Political Bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the Powers of the Earth, the separate and equal Station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them. . . .