Adult Education as a Pathway to Empowerment: Challenges and Possibilities

- Open Access

- First Online: 24 March 2023

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Pepka Boyadjieva 8 &

- Petya Ilieva-Trichkova 8

Part of the book series: Palgrave Studies in Adult Education and Lifelong Learning ((PSAELL))

2524 Accesses

1 Citations

This chapter develops a theoretical framework for conceptualising adult education’s role in individual empowerment using a capability approach perspective. It also provides empirical evidence on how adult education can contribute to individuals’ empowerment. Adult education is both a sphere of, and a factor for, empowerment. Empowerment through adult education is embedded in institutional structures and socio-cultural contexts and has both intrinsic and instrumental value; it is neither linear nor unproblematic. Adult education’s empowerment role is revealed in expanded agency; this enables individuals and social groups to gain power over their environment. Using quantitative and qualitative data, the chapter shows that participation in non-formal adult education can empower individuals, increasing their self-confidence, capacity to find employment, and to control their daily lives.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Empowerment Through Lifelong Learning

Introduction

There has recently been growing research interest in going beyond the instrumental and economised understanding of adult and lifelong education and learning and focusing on its empowerment potential (Baily, 2011 ; Fleming & Finnegan, 2014 ; Fleming, 2016 ; Tett, 2018 ). Attempts have also been made to provide a more comprehensive view of the mission and roles adult education serves by revealing its substantial transformative power at both the individual and societal levels (Boyadjieva & Ilieva-Trichkova, 2021 ). In addition, policy documents have been published which not only acknowledge the complexity of adult educational goals and the contributions made to individual and societal development, but also explicitly emphasise the emancipatory role that lifelong learning can play. Thus, according to UNESCO’s Recommendation on Adult Learning and Education of 2015 (UNESCO, 2016 ), the objectives of adult learning and education are: ‘to equip people with the necessary capabilities to exercise and realise their rights and take control of their destinies… to develop the capacity of individuals to think critically and to act with autonomy and a sense of responsibility’, and to reinforce their capacity not only to adapt and deal with but also to ‘ shape the developments taking place in the economy and the world of work’ (art. 8 and 9, italics added). However, more research is needed in order to better conceptualise and empirically demonstrate the complexity of the empowerment potential and implementation of adult education in different socio-cultural contexts.

Against the above background, this chapter contributes to the discussion of the relationship between adult education and empowerment, thus further developing one of the main arguments of the present book: that there are multiple benefits to lifelong learning and adult education for individuals and societies, and they should not be restricted to delivering requisite skills to the workforce. It also enriches the understanding of the concept of bounded agency (Rubenson & Desjardins, 2009 ) by demonstrating, firstly, that the process of empowerment through adult education is not a linear or unproblematic one and, secondly, that only in some cases can the benefits from adult education lead to empowered agency. More concretely, the objective of this chapter is twofold. On the one hand, it seeks to outline a theoretical framework for conceptualising the role of adult education in individual empowerment from a capability approach perspective. On the other, it aims to provide some empirical evidence about how adult education can contribute to individuals’ empowerment. To that end, we argue that adult education is a distinct sphere of empowerment. At the individual level and from a capability approach perspective, empowerment in and through adult education is a process of expanding both agency and capabilities, enabling individuals to gain power over their environment as they strive for their own well-being and a just social order. As a process, empowerment is embedded in the available opportunity structures.

The chapter proceeds as follows. First, we present our conceptual framework by briefly reviewing different approaches towards the understanding of empowerment and highlighting ideas which are relevant to discussions on (adult) education. Then, we outline an empowerment perspective towards adult education within the theoretical framework of the capability approach. A description of the data (both quantitative and qualitative) and methods as well as a presentation of the results follow. Finally, these results are discussed in light of previous research, and some directions for future research and policy implications are outlined in the conclusion.

Theoretical Considerations

Empowerment as a contested concept.

Many studies—and Chap. 2 of this volume, as well—have emphasised that the notion of empowerment Footnote 1 is inherently complex and open to many interpretations, that there are internal contradictions in this concept, and that it remains under-theorised and contested (Samman & Santos, 2009 ; Monkman, 2011 ; Pruijt & Yerkes, 2014 ; Unterhalter, 2019 ). Some of the problems and confusion which prevent our understanding of empowerment arise from the fact that its ‘root-concept – power – is itself disputed’ (Rowlands, 1995 , p. 101).

Unterhalter ( 2019 , p. 86) traces the history of the use of the word empowerment back to the mid-seventeenth century, outlining that this historical detour highlights ‘that empowerment as a concept can be deployed in multiple ways’. The concept was later firmly established by radical social movements, especially women’s movements, and feminist theorists starting in the 1970s. It has mainly been used to delineate personal and collective actions for justice and the processes of participatory social change which challenge both existing power hierarchies and the relationship between inequality and exclusion (Batliwala, 1994 , 2010 ; Unterhalter, 2019 ). It has been argued that, over the last 30 years, the concept of empowerment has undergone some distortion, becoming ‘a trendy and widely used buzzword’ (Batliwala, 2010 , p. 111). Batliwala ( 2010 , pp. 114, 119) claims that the dominance of neo-liberal ideology has led to ‘the transition of empowerment out of the realm of societal and systemic change into the individual domain—from a noun signifying shifts in social power to a verb signalling individual power, achievement, status’. Some authors argue that empowerment in itself is ‘a disguised control device’, one ‘fraught with contradictions’ stemming from its essence as an asymmetrical relationship (e.g. Pruijt & Yerkes, 2014 , pp. 49–50). Empowerment is also viewed as a power relationship which remains, even when the will to empower is well-intentioned, ‘a strategy for constituting and regulating the political subjectivities of the “empowered”; and furthermore, “the object of empowerment is to act upon another’s interests and desires in order to conduct their actions toward an appropriate end”’ (Cruikshank, 1999 , p. 69). In a similar vein, Pruijt and Yerkes ( 2014 ) identify three challenges associated with empowerment as an asymmetrical relationship: level of control, programmed failure, and risk of stigmatisation. Thus, for example, they argue that ‘an empowerment frame can entice people to start on an impossible mission that can end with them blaming themselves for problems beyond their control’ and that often ‘those to be empowered are deemed to be lacking in autonomy or self-sufficiency’, which entails a risk of stigmatisation (Pruijt & Yerkes, 2014 , p. 51).

In a comprehensive review of works on empowerment, Ibrahim and Alkire ( 2007 ) systematise 29 understandings of the concept used in the period from 1991 to 2006. These definitions of empowerment differ in terms of the theoretical frameworks they have been elaborated in, the levels they refer to (individual and/or collective), and their scope (processes but also activities and outcomes). All of the above clearly demonstrates that empowerment—both as a concept and a practice—needs to be very carefully studied and re-thought based on fresh theoretical ideas, taking into account its specificity in different social spheres as well as socio-cultural and political contexts. It is very important to emphasise that ‘although different kinds of empowerment may be interconnected, empowerment is domain specific’ (Ibrahim & Alkire, 2007 , p. 383). This means that in order to be thoroughly understood, empowerment should be analysed in respect to different domains of life whilst acknowledging their specificity. Thus, for example, empowerment in education is not only related to empowerment at work or in public life but may also differ from them. Revealing this difference is a sine qua non for grasping its meaning and path towards accomplishment.

Theorising the Relationship Between Empowerment and Education

As Unterhalter ( 2019 , p. 75) acknowledges, ‘the relationship between empowerment and education is neither simple nor clear’. She concludes that education ‘can be positioned as an outcome of empowerment or as a process associated with its articulation’ (Unterhalter, 2019 , p. 80).

The diversity of theoretical approaches which could be applied towards an understanding of the relationship between empowerment and education is clearly evident in the special ‘Gender, education and empowerment’ issue of the journal Research in Comparative and International Education , published in 2011. Various authors there use Stromquist’s ( 1995 ) model of empowerment, which consists of four necessary components: cognitive, psychological, political, and economic. Still others try to reveal the three dimensions upon which Rowlands’s ( 1995 ) empowerment operates—the personal, where empowerment is about developing a sense of self and individual confidence and capacity; that of close relationships, where empowerment is about developing the ability to negotiate and influence the nature of those relationships and the decisions made within them; and the collective, where individuals work together to achieve more extensive impact than they could alone. The issue features articles based on Cattaneo and Chapman’s ( 2010 ) Empowerment Process Model, articulating empowerment as an iterative process whose components include personally meaningful and power-oriented goals, self-efficacy, knowledge, competence, and action, as well as Rocha’s model ( 1997 ), which presents the empowerment process as a ladder moving from individual to community. Furthermore, several authors have used the capability approach (Sen, 1999 ; Nussbaum, 2000 ). It is important to note that there are some crucial points regarding the relationship between empowerment and education which the studies in this issue agree upon: ‘education does not automatically or simplistically result in empowerment; empowerment is a process; it is not a linear process, direct or automatic; context matters; decontextualized numerical data, although useful in revealing patterns and trends, are inadequate for revealing the deeper and nuanced nature of empowerment processes; individual empowerment is not enough; collective engagement is also necessary; empowerment of girls and women is not just about them, but perforce involves boys and men in social change processes that implicate whole communities; it is important to consider education beyond formal schooling: informal interactional processes and multi-layered policy are also implicated’ (Monkman, 2011 , p. 10). Taking into account these outlined characteristics of the relationship between empowerment and education, we will try to delve further and present a more sophisticated understanding of this relationship within the framework of the capability approach.

The Capability Approach Towards the Relationship Between Empowerment and (Adult) Education

The capability approach is a social justice normative theoretical framework for conceptualising and evaluating phenomena such as inequalities, well-being, and human development. According to the capability approach, it is not so much the achieved outcomes (functionings) that matter; rather, one’s real opportunities (capabilities) determine whether those outcomes can be achieved. For Sen, capabilities are freedoms conceived as real opportunities (Sen, 1985 , 2009 ). More specifically, ‘capabilities as freedoms’ refer to the presence of valuable options—in the sense that opportunities do not exist only formally or legally but are also effectively available to the agent (Robeyns, 2013 ).

There are three strands of research relevant to any attempt at understanding the relationship between empowerment and (adult) education from a capability approach perspective. The first one discusses the meanings of empowerment by drawing on different concepts associated with the capability approach, but it does not reflect upon any possible connections between education and empowerment (e.g. Alsop et al., 2006 ; Ibrahim & Alkire, 2007 ; Samman & Santos, 2009 ). The second strand includes literature on education and empowerment, also often referring to the debate over capabilities and empowerment (e.g. Loots & Walker, 2015 ; Monkman, 2011 ). The third strand comprises studies which aim to reveal the heuristic potential of the capability notion in understanding the relationship between empowerment and education (e.g. DeJaeghere & Lee, 2011 ; Seeberg, 2011 ; Unterhalter, 2019 ).

Based on this literature, we define empowerment in and through (adult) education from a capability approach perspective as an expansion of both agency (process freedom) and capabilities (opportunity freedom). Empowerment and adult education have one characteristic in common: neither is a single act, but they are rather lifelong processes embedded in the available institutional structures and socio-cultural context. The empowerment role of (adult) education is purposeful and matters both intrinsically and instrumentally. Empowerment in and through (adult) education is closely related, but not identical, to agency enhancement. It is not only an expanded agency but one which has a clear goal—gaining control over an individual’s environment with the aim of improving their own well-being and that of society. The empowerment role of (adult) education has two sides: a subjective one, referring to an individual’s capability to gain control over the environment, and an objective one, reflecting the available opportunity structures.

Adult Education as a Sphere of Empowerment

Alsop et al. ( 2006 , p. 19) identify three domains, divided into different subdomains, in which empowerment can take place—the state (justice, politics, and public service delivery); the market (labour, goods, and private services); and society (intra-household and intra-community). We argue that (adult) education can be defined as a specific, complex subdomain of empowerment which functions at the intersection of all three domains: the state, the market, and society. (Adult) education can be a public service, but it is also a good—both private and public—which is firmly embedded in the dominant social hierarchies, institutional and cultural norms, community, and societal milieu.

In conceptualising (adult) education as a sphere of empowerment, we have drawn upon the heuristic potential of Sen’s concept of conversion factors and the crucial significance of context for agency within the capability approach (Sen, 1985 , 1999 ; Nussbaum, 2000 ). Conversion factors are defined as a range of factors influencing how a person can convert the characteristics of his/her available resources (initial conditions) into freedom or achievement. The empowering role of (adult) education depends on and is realised through the very way it is established and organised in a given society. That is why revealing and evaluating the empowerment role of adult education requires ‘understanding the contexts of learning, teaching, and education governance, considering whether the content of education encourages an individualistic or an inclusive and solidaristic sense of agency’, and looking ‘both at organisations and the norms that govern them’ (Unterhalter, 2019 , p. 93).

At first glance, it seems that the role of adult education (viewed as a sphere and an outcome) for the subjectivity and agency of individuals would be less pronounced in adult students than teenagers. However, this statement does not take into account essential changes in systemic-structural characteristics of contemporary societies or the individual’s role in shaping them. The societies of late modernity feature changes, turning from sporadic occurrences into a permanent fixture, in both their existence and the lives of individuals (Bauman, 1997 ). Changes in the main characteristics of these societies will inevitably generate significant changes in the way individuals relate to their own lives, models of personal realisation, and long-term plans. Such life plans and goals are becoming increasingly hard to pursue, and the paths taken by individuals do not often follow single projects but rather increasingly become a matter of self-building—wherein the goals at one stage of a person’s development may not necessarily accrue upon the goals of preceding stages, quite possibly taking a very different turn (Bauman, 2002 , pp. 433–434). Thus, throughout their lives, people are confronted with the need to (re)build their identity and subjectivity.

Adult Education as a Factor for Empowerment

Adult education can function as a factor for empowerment at three levels—individual, collective/group, and societal.

At an individual level, empowerment through adult education relates to its role in further developing individual capability sets, thus increasing their potential to make high-quality choices and allowing them the freedom to act. As already outlined, empowerment is not about expanding agency for any purposes or developing any capabilities—it is about developing capabilities that enable engagement in social change processes. Unterhalter ( 2019 , p. 80) argues that ‘the capability approach provides some important additional conceptual connections that help link empowerment more closely to ideas about social justice and an understanding of the institutional space in which this is to be achieved’. She also emphasises, ‘for Sen, agency (and by implication empowerment) is not mere self-interest, but an expression of a sense of fairness for oneself and due process for oneself and others’ (Unterhalter, 2019 , p. 91).

At a collective/group level, adult education can empower different social groups, especially vulnerable ones, by helping them to organise and express their interests and to achieve upward mobility.

At a societal level, empowerment through adult education reflects the role of education towards achieving important public goods—such as social equity, trust, and environmental conservation—and thus making the world a better place to live in. According to Sen ( 2009 , p. 249), development is ‘fundamentally an empowering process’, and one of its important aims is to preserve and enrich the environment. Education plays a crucial role in this empowering process, as ‘the spread of school education and improvements in its quality can make us more environmentally conscious’ (Ibid).

Intrinsic and Instrumental Value of the Empowerment Role of Adult Education

The capability approach requires looking beyond achievements and relating the real freedoms or opportunities an individual has to the ‘goals or values he or she regards as important’ (Sen, 1985 , p. 203). As far as adult education can have both intrinsic and instrumental value, its empowerment role also matters both intrinsically and instrumentally. Empowerment through adult education has intrinsic value: similarly to agency (Sen, 1985 ), it is the result of a ‘genuine choice’ made by a ‘responsible agent’, and as such, this is an important end in and of itself. Instrumentally, empowerment through adult education matters because it can serve as a means to develop other capabilities and achieve different outcomes.

The Role of Non-formal Adult Education for Increasing Individuals’ Agency Capacity: An Empirical Study

The next part of the chapter is empirically based and focuses only on two aspects of the very complex relationship between empowerment and adult education, outlined in the theoretical discussion. More concretely, we will analyse the influence of participation in non-formal adult education on the subjective side of the empowerment role of adult education, that is, on individuals’ capacity to act through increasing their self-confidence and capacity to control their daily life.

Data and Empirical Strategy

The empirical basis of our study is the Adult Education Survey Footnote 2 (AES) and some interviews. The Adult Education Survey, conducted via random sampling procedure, targets people aged 25 to 64 who live in private households. So far, this survey has been conducted three times: in 2007, 2011, and 2016. However, 2007 was the only year in which questions about attitudes towards learning were included. The number of countries participating in the 2007 Adult Education Survey was 29. However, data on attitudes are available for just 13 of those (Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Finland, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia). Depending on the variable of interest, this data could also be found for 14 (+Poland) or 15 countries (+Poland and the United Kingdom). For that reason, the following analysis is based on data for the above-listed countries. In terms of the overall quality of data, it is worth mentioning that the Synthesis Quality Report (Eurostat, 2010 ) evaluated the Adult Education Survey positively. Classification regarding education follows the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) revision of 1997.

In addition, some qualitative data from interviews with young adults involved in adult education programmes will also be presented. As there are only a limited number of interviews that were carried out within the Enliven project, we have used quotations from these interviews mainly to illustrate the results obtained based on qualitative data. The fieldwork was conducted on 28 May 2018 in a small city in Bulgaria. Seven in-depth interviews, based on a preliminary scenario, were conducted: five with participants from low-income households in the Roma ethnic community lacking education and work experience; one with a staff member running the programme (the school principal); and one with a representative at the level of the learning setting (a teacher).

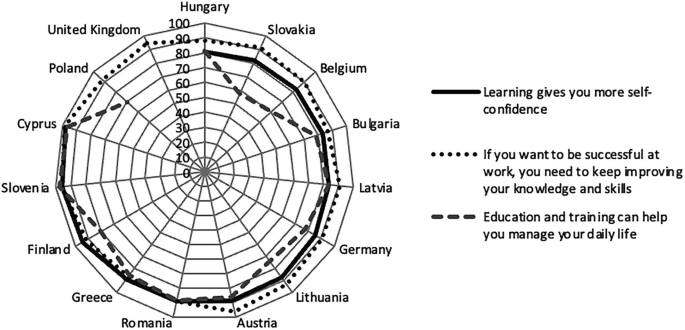

We measured self-confidence via two indicators: ‘ Learning gives you more self-confidence’ and ‘ If you want to be successful at work, you need to keep improving your knowledge and skills’ . One indicator was used to measure the capacity to control one’s daily life: ‘ Education and training can help you manage your daily life’ . These indicators represent respondents’ subjective perceptions and make up our dependent variables, which we measured on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (Fully agree) to 5 (Totally disagree). However, for the needs of our analysis, the scale for each dependent variable was dichotomized into two values: 1, which includes the answers ‘Agree’ and ‘Fully agree’, and 0, which includes the remaining three answer options.

We used multi-level modelling to analyse the three dependent variables. Given that our dependent variables are binary, we used two-level random intercept logistic models. We also used the xtlogit command in Stata 14. More specifically, we estimated three model specifications for each dependent variable. This was done in order to see whether the effects of the different variables changed when additional variables were included. Model 0 is our (unconditional) baseline model containing the intercept (constant) only. Model 1 includes our main independent variable—participation in non-formal education or training (NFET) in the previous 12 months (dummy ref.: no = 0, yes = 1). We also included the highest educational level (three categories, ref.: ISCED 0–2 = low, ISCED 3–4 = medium, and ISCED 5–6 = higher) because previous research has clearly shown that participation in adult education strongly depends on the level of educational attainment (Roosmaa & Saar, 2012 ; Boyadjieva & Ilieva-Trichkova, 2021 ). In Model 2, we included an interaction term between the highest educational level and participation in NFET in order to determine whether the effect of NFET on the three dependent variables differed according to adults’ educational levels. To account for differences in the composition of different groups of adults, all our specifications were made to control for: educational background (dummy ref.: 0 = no parents had higher education [low]; 1 = at least one parent had higher education [high]); gender (dummy ref.: 0 = male; 1 = female); and main activity (ref. employed; 1 = unemployed, or 2 = inactive).

Following Rabe-Hesketh and Skrondal ( 2012 ), we interpreted the odds ratios conditionally on the random intercepts of the models. The odds ratio is the number by which we multiplied the odds of agreeing with our three indicators for measuring self-confidence and control over everyday life for every single-unit increase in an independent variable, for example, participation in non-formal adult education. We interpreted an odds ratio greater than 1 as the increased odds of agreement with a certain statement along with the independent variable, whereas an odds ratio of less than 1 indicated decreased odds when the independent variable increased. Given that most of our independent variables are dummy and categorical, we compared the odds of each statement category with one which we chose as a reference.

How Learning Matters to Adults’ Agency Capacity

We begin with a look at the distribution of dependent variables in 13–15 European countries. Figure 7.1 shows the proportions of those agreeing with the three statements of interest. Overall, the majority of adults have a very positive attitude towards learning and they think that it gives them more confidence, regardless of their country of residence. The same is also true for the attitude that people who want to be successful need to keep improving their knowledge and skills—even to a slightly higher extent in almost all countries apart from Finland, Greece, Romania, and Slovenia. The majority of adults in all countries agreed that education and training could help them manage their daily life, although to a lesser extent compared to the previous two statements.

Attitudes towards the benefits of learning of adults aged 25–64 (Percentages of those who agreed with the three statements of interest). (Source: AES 2007, own calculations, weighted data)

We now proceed to a more detailed discussion, based on multivariate analyses, of the three benefits of participation in non-formal adult education. Model 1 in Table 7.1 indicates that participation in NFET was positively associated with adults’ perceptions that learning provides more confidence . More specifically, the odds of agreeing with this statement are about 1.7 times greater for adults who had participated in NFET in the previous 12 months than for those who had not taken part in such an activity. There are also clear differences between adults according to educational level. The higher their attainment of education, the higher the conditional odds were of agreeing that learning gives you more self-confidence. The estimates in Model 2 are consistent with those from Model 1, and we could still observe the positive link between higher educational attainment and participation in NFET in the last 12 months and adults’ attitudes that learning provides more confidence. It is important to emphasise that the influence of NFET on this attitude differed among adults with varying levels of education. Namely, this influence was less pronounced among those with medium and higher education levels than those with lower levels of education. More specifically, having participated in NFET is significantly associated with relatively lower conditional odds of agreeing that learning provides more confidence among adults with medium and higher educational levels.

We carried out interviews with young adults who were illiterate or had completed only primary education. Those who had passed literacy programmes felt more satisfied, independent and confident:

Interviewer: ‘How do you feel now? Do you have a higher level of self-confidence?’

Respondent: ‘Yes, I feel good about it. Even when they evaluated me, I felt really happy.’ [BG2_P5_108]

Respondent: ‘It was really pleasant. I actually liked it. I’m satisfied.’ [BG2_P1_147–148]

The interviews with other young adults with lower literacy rates also confirmed that their decisions to be involved in adult education had been informed by a desire for their capabilities as human beings to be recognised and to develop their own abilities in order to improve self-identity and contribute to the flourishing of others.

Participation in NFET also demonstrated a positive link with adults’ likelihood to agree that in order to be successful at work, you need to keep improving your knowledge and skills . More specifically, Model 1 in Table 7.2 indicates that the conditional odds of agreeing with this statement were about 2 times greater for adults who had participated in NFET in the previous 12 months than for those who had not taken part in such an activity. It also shows that there are clear differences between adults, depending on their educational levels, in terms of attitudes about whether the constant improvement of knowledge and skills is important for success at work. The higher the educational level, the higher the odds were of agreeing that people’s improvement of knowledge and skills was a prerequisite for success at work, given the other covariates. The estimates in Model 2 are fairly consistent with those in Model 1—an interaction term was added between the highest educational attainment and participation in NFET. Our analysis shows that having participated in NFET was significantly associated with relatively lower conditional odds of agreeing that ‘If you want to be successful at work, you need to keep improving your knowledge and skills’ among young adults with medium and higher levels of education.

The positive association between participation in NFET and the importance given to improving knowledge and skills as a prerequisite for success at work is furthermore clearly visible in the following quotations from our interviews with young adults:

Interviewer: ‘How has participating in the programme changed your life?’

Respondent: ‘What’s changed, really, is that now I know more and things are clearer to me… And I want to continue studying… I’d really like to get a license for a car – a driver’s licence. I’d feel a little better at least having my diploma. Everyone thinks they can go out and find a job, no problem. It’s not such a big deal after all, completing 7th grade, but every place wants a diploma now.’ [BG2_P1_129–139]

Respondent: ‘Nothing happens without an education.’ [BG2_P2_42]

Participation in NFET also had a positive influence on the likelihood adults to agree that education and training can help you manage your daily life holding all other variables constant. More specifically, Model 1 in Table 7.3 shows that the odds of agreeing with this statement were about 1.4 times greater for adults who had participated in NFET in the previous 12 months than for those who had not taken part in such an activity. There are also clear differences among adults, depending on their educational levels, in terms of their degree of agreement that education and training help them to manage their daily lives. The higher the educational attainment, the higher the odds were of agreeing that education and training could help one to manage their daily life. The estimates in Model 2 are consistent with those from Model 1, and we can still observe the positive association between formal education and participation in NFET in the last 12 months and the attitudes about the role of education and training in managing one’s daily life—we added an interaction term between the highest educational level and participation in formal and NFET. In a similar way to the other two dependent variables, the results here show that the influence of NFET varies among adults with different levels of education. So, it follows that this influence was lower among those with medium and higher education levels than among those with low levels of education.

The positive association between participating in NFET and beliefs that education and training could help one to manage their daily life is further illustrated here:

Interviewer: ‘Did you volunteer for the programme?’

Respondent: ‘Yes, voluntarily, because they didn’t want to hire me because I am illiterate. And also [because I want] to be literate, not to be cheated with the bills, to understand numbers, to understand what is written.’ [BG2_P5_38–44]

Interviewer: ‘What motivated you to participate in the programme?’

Respondent: ‘I want to get my driver’s license, since I have a small child who’s starting kindergarten, then school. I think we’ll have to travel a long way away because we’re from the ghetto. I’d still like for my kid to learn in Bulgarian.’ [BG2_P3_91–93]

The Need to Rethink Adult Education Policies

The present chapter enriches the critical perspective adopted by this book and the Enliven project by outlining a theoretical framework for conceptualising the role of adult education for individuals’ empowerment from a capability approach perspective. The study contains both theoretical and methodological contributions. At the theoretical level, it argues that adult education should be regarded as both a sphere of and a factor for empowerment. Empowerment through adult education is embedded in the available institutional structures and socio-cultural context, and it matters both intrinsically and instrumentally. The empowerment role of adult education is revealed through agency expansion, which enables individuals and social groups to gain power over their environment in their striving towards individual and societal well-being. At the methodological level, to the best of our knowledge, this chapter offers the first attempt to investigate the importance of adult education in empowerment by using quantitative data from a large-scale international survey. Our analyses show that participation in non-formal adult education is viewed as a means for empowering individuals through increasing their self-confidence and their capacity to find a job and to control their daily life.

Despite wide-ranging criticism, adult education policies have recently been dominated by vocationalisation, instrumental epistemology (Bagnall & Hodge, 2018 ), and the prioritisation of ‘learning as performance over the holistic educational formation of a person’ (Seddon, 2018 , p. 111). The empowerment perspective helps to reveal one very often overlooked part of these narrow, deficient aspects of contemporary adult education policies. We are referring to the often neglected role of adult education in the formation of individual agency, self-confidence, and capacity to control one’s environment.

This chapter has shown that the relationship between empowerment and adult education policies and practices should be regarded as a complex field of study. There is a need for future in-depth inquiries into a number of theoretical and methodological issues, including: (i) how the empowerment role of adult education differs in various socio-economic contexts and how to explain transnational differences; (ii) which dominant cultural norms in different countries impede parity of participation in adult education and its empowerment role; (iii) how the empowerment role of adult education is manifested in formal and non-formal adult education; (iv) how to develop policies aimed at enhancing the role of adult education in the formation of individual agency, self-esteem, and self-confidence; (v) how to produce reliable data in order to study the relationship between empowerment and adult education; (vi) what kinds of methodological instruments may be needed to reveal different aspects of the relationship between empowerment and adult education; and vii) what kinds of objective indicators could be used for measuring the empowerment role of adult education.

Tett ( 2018 , p. 362) mentions that in the league tables produced by international organisations such as the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) and the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competences (PIAAC), ‘attention is paid only to economic (or redistributive) aspects of inequality and both the cultural (or recognitive) aspects and also the participative (or representative) are ignored’. This conclusion can be extended to the Adult Education Survey, as well. In fact, the 2007 pilot Adult Education Survey survey included a special section on ‘Attitude towards learning’ that was comprised of eight questions. Footnote 3 Unfortunately, these and a number of other attitudinal questions were left out of the subsequent surveys conducted in 2011 and 2016.

Our analysis has demonstrated that the empowerment effect of adult education is greater among learners with low educational levels than it is among those with medium and higher educational levels. This means that in order to truly be sensitive towards vulnerable groups, adult education policies have to more seriously consider the varying roles adult education can play in the empowerment of people from different social backgrounds.

‘To “empower” as a neologism was first used in the mid-seventeenth century in England in the context of the Civil War… the first uses of the term in 1641, 1643, and 1655 all refer generally to men being “empowered” by the law or a supreme authority to do certain things’ (Unterhalter, 2019 , p. 80).

This chapter uses data from Eurostat, AES, 2007, obtained for the needs of Research Project Proposal 124/2016-LFS-AES-CVTS-CSIS. The responsibility for all conclusions drawn from the data lies entirely with the authors.

More specifically, adults were asked if they agreed or disagreed with the following statements: ‘People who continue to learn as adults are more likely to avoid unemployment’; ‘If you want to be successful at work, you need to keep improving your knowledge and skills’; ‘Employers should be responsible for the training of their employees’; ‘The skills you need to do a job can’t be learned in the classroom’; ‘Education and training can help you manage your daily life better’; ‘Learning new things is fun’; ‘Learning gives you more self-confidence’; & ‘Individuals should be prepared to pay something for their adult learning’.

Alsop, R., Bertelsen, M., & Holland, J. (2006). Empowerment in Practice. From Analysis to Implementation . World Bank.

Google Scholar

Bagnall, R. G., & Hodge, S. (2018). Contemporary Adult and Lifelong Education and Learning: An Epistemological Analysis. In M. Milana, S. Webb, J. Holford, R. Waller, & P. Jarvis (Eds.), Palgrave International Handbook on Adult and Lifelong Education and Learning (pp. 13–34). Palgrave Macmillan.

Chapter Google Scholar

Baily, S. (2011). Speaking Up: Contextualizing Women’s Voices and Gatekeepers’ Reactions in Promoting Women’s Empowerment in Rural India. Research in Comparative and International Education, 6 (1), 107–118.

Article Google Scholar

Batliwala, S. (1994). The Meaning of Women’s Empowerment: New Concepts from Action. In G. Sen, A. Germain, & L. C. Chen (Eds.), Population Policies Reconsidered: Health, Empowerment and Rights (pp. 127–138). Harvard University Press.

Batliwala, S. (2010). Taking the Power Out of Empowerment–An Experiential Account. In A. Cornwall & D. Eade (Eds.), Deconstructing Development Discourse, Buzzwords and Fuzzwords (pp. 111–122). Oxfam GB.

Bauman, Z. (1997). Universities: Old, New and Different. In A. Smith & F. Webster (Eds.), The Postmodern University? Contested Visions of Higher Education in Society (pp. 17–26). SRHE and Open University Press.

Bauman, Z. (2002). A sociological Theory of Postmodernity. In C. Calhoum, J. Gerteis, J. Moody, S. Pfaff, & I. Virk (Eds.), Contemporary Sociological Theory (pp. 429–440). Blackwell Publishing.

Boyadjieva, P., & Ilieva-Trichkova, P. (2021). Adult Education as Empowerment: Re-imagining Lifelong Learning Through the Capability Approach, Recognition Theory and Common Goods Perspective . Palgrave Macmillan.

Book Google Scholar

Cattaneo, L. B., & Chapman, A. R. (2010). The Process of Empowerment: A Model for Use in Research and Practice. American Psychology, 65 (7), 646–659.

Cruikshank, B. (1999). The Will to Empower. Democratic Citizens and Other Subjects . Cornell University Press.

DeJaeghere, J., & Lee, S. (2011). What Matters for Marginalized Girls and Boys in Bangladesh: A Capabilities Approach for Understanding Educational Well-Being and Empowerment. Research in Comparative and International Education, 6 (1), 27–42.

Eurostat. (2010). Synthesis Quality Report: Adult Education Survey . European Commission.

Fleming, T. (2016). Reclaiming the Emancipatory Potential of Adult Education: Honneth’s Critical Theory and the Struggle for Recognition. European Journal for Research on the Education and Learning of Adults, 7 (1), 13–24.

Fleming, T., & Finnegan, F. (2014). Critical Theory and Non-traditional Students in Irish Higher Education. In F. Finnegan, B. Merrill, & C. Thunborg (Eds.), Student Voices on Inequalities in European Higher Education (pp. 51–62). Routledge.

Ibrahim, S., & Alkire, S. (2007). Agency and Empowerment: A Proposal for Internationally Comparable Indicators. Oxford Development Studies, 35 (4), 379–403.

Loots, S., & Walker, M. (2015). Shaping a Gender Equality Policy in Higher Education: Which Human Capabilities Matter? Gender and Education, 27 (4), 361–375.

Monkman, K. (2011). Introduction. Framing Gender, Education and Empowerment. Research in Comparative and International Education, 6 (1), 1–13.

Nussbaum, M. (2000). Women and Human Development: The Capabilities Approach . Cambridge University Press.

Pruijt, H., & Yerkes, M. A. (2014). Empowerment as Contested Terrain. European Societies, 16 (1), 48–67.

Rabe-Hesketh, S., & Skrondal, A. (2012). Multilevel and Longitudinal Modeling Using Stata (3rd ed.). Stata Press.

Robeyns, I. (2013). Capability Ethics. In H. LaFollette & I. Persson (Eds.), The Blackwell Guide to Ethical Theory (2nd ed., pp. 412–432). Blackwell Publishing.

Rocha, E. M. (1997). A Ladder of Empowerment. Journal of Planning Education & Research, 17 , 31–44.

Roosmaa, E.-L., & Saar, E. (2012). Participation in Non-formal Learning in EU-15 and EU-8 Countries: Demand and Supply Side Factors. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 31 (4), 477–501.

Rowlands, J. (1995). Empowerment Examined. Development in Practice, 5 (2), 101–107.

Rubenson, K., & Desjardins, R. (2009). The Impact of Welfare State Regimes on Barriers to Participation in Adult Education: A Bounded Agency Model. Adult Education Quarterly, 59 (3), 187–207.

Samman, E., & Santos, M. E. (2009). Agency and Empowerment: Review of Concepts, Indicators and Empirical Evidence (OPHI Research Chapter 10a). Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative.

Seddon, T. (2018). Adult Education and the ‘Learning’ Turn. In M. Milana, S. Webb, J. Holford, R. Waller, & P. Jarvis (Eds.), Palgrave International Handbook on Adult and Lifelong Education and Learning (pp. 111–131). Palgrave Macmillan.

Seeberg, V. (2011). Schooling, Jobbing, Marrying: What’s a Girl to Do to Make Life Better? Empowerment Capabilities of Girls at the Margins of Globalization in China. Research in Comparative and International Education, 6 (1), 43–61.

Sen, A. (1985). Well-being, Agency and Freedom: The Dewey Lectures 1984. The Journal of Philosophy, 82 (4), 169–221.

Sen, A. (1999). Development as Freedom . Oxford University Press.

Sen, A. (2009). The idea of justice . Allen Lane.

Stromquist, N. P. (1995). Theoretical and Practical Bases for Empowerment. In C. Medel Annonuevo (Ed.), Women, Education and Empowerment: Pathways Towards Autonomy (pp. 13–22). UNESCO-UIE.

Tett, L. (2018). Participation in Adult Literacy Programmes and Social Injustices. In M. Milana, S. Webb, J. Holford, R. Waller, & P. Jarvis (Eds.), Palgrave International Handbook on Adult and Lifelong Education and Learning (pp. 359–374). Palgrave Macmillan.

UNESCO. (2016). Recommendation on Adult Learning and Education 2015 . UNESCO.

Unterhalter, E. (2019). Balancing Pessimism of the Intellect and Optimism of the Will: Some Reflections on the Capability Approach, Gender, Empowerment, and Education. In D. A. Clark, M. Biggeri, & A. Frediani (Eds.), The Capability Approach, Empowerment and Participation Concepts, Methods and Applications (pp. 75–99). Palgrave Macmillan.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute of Philosophy and Sociology, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia, Bulgaria

Pepka Boyadjieva & Petya Ilieva-Trichkova

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

School of Education, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK

John Holford

Pepka Boyadjieva

Sharon Clancy

3s, Vienna, Austria

Günter Hefler

Institute for Forecasting, CSPS, Slovak Academy of Sciences, Bratislava, Slovakia

Ivana Studená

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Boyadjieva, P., Ilieva-Trichkova, P. (2023). Adult Education as a Pathway to Empowerment: Challenges and Possibilities. In: Holford, J., Boyadjieva, P., Clancy, S., Hefler, G., Studená, I. (eds) Lifelong Learning, Young Adults and the Challenges of Disadvantage in Europe. Palgrave Studies in Adult Education and Lifelong Learning. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-14109-6_7

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-14109-6_7

Published : 24 March 2023

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-14108-9

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-14109-6

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Back to Home

Understanding Adult Literacy in the U. S.

Research indicates that there continues to be a need for Federal investment in adult education programs, in part because of data suggesting that the United States is losing ground to many of its economic competitors as measured by the employment-related skills of working-age adults.

The Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC), also known as the Survey of Adult Skills, is a cyclical, large-scale international study that was developed under the auspices of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). PIAAC is a direct household assessment designed to assess and compare the basic skills and competencies of adults around the world. The assessment focuses on cognitive and workplace skills needed for successful participation in 21st-century society and the global economy. In the U.S., PIAAC is funded and led by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) of the U.S. Department of Education.

The PIAAC Gateway provides access to U.S. and international resources on PIAAC. The Gateway includes information and resources for researchers, practitioners, program managers, policy makers, and more.

PIAAC Cycle 1 (2012-2017) included three rounds of data collection in the U.S., each conducted in 2012, 2014, and 2017. From these rounds of data collection, NCES developed the interactive U.S. PIAAC Skills Map: State and County Indicators of Adult Literacy and Numeracy , an online mapping tool with estimates of adults' literacy and numeracy skills for all U.S. states and counties. More information on the state and county estimates can be found here .

PIAAC Cycle 2 (2022-2029) includes two rounds of data collection in the U.S., each being conducted in 2022-2023, and 2024-2029. There are several differences between PIAAC Cycle 1 and Cycle 2. PIAAC Cycle 2 continues the direct assessment of literacy, numeracy, and includes a new domain called adaptive problem solving. The U.S. PIAAC assessment has had a new section added to collect data on the financial literacy of the adult population. In addition to the reading components, PIAAC Cycle 2 includes component measures of numeracy. In PIAAC Cycle 2, the direct assessment is conducted on a tablet platform.

To learn more about the NCES PIAAC Schedule and Plans page, click here .

To learn more about the 43 million U. S. adults with low literacy skills and the 74 million adults with low numeracy skills, click here .

To learn more about PIAAC and see Frequently Asked Questions, click here .

To learn more about the U.S. Prison Study data collection, click here .

Ongoing and Completed Research

The Office of Career, Technical, and Adult Education (OCTAE) at the U.S. Department of Education uses national leadership funds from section 242 of AEFLA to conduct rigorous research and evaluation. OCTAE is currently collaborating with the Institute of Education Sciences on a national assessment of adult education that is examining both the implementation of adult education policies and programs and the effectiveness of adult education strategies.

- Linking Adult Education to Workforce Development in 2018-19: Early Implementation of the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act at the Local Level – Many adults need help with basic skills like reading, writing, mathematics, and English proficiency to succeed in the American workforce. Congress has long provided resources to help individuals address these educational challenges, most recently through Title II of the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act of 2014. But WIOA includes new requirements and incentives to strengthen the link between adult education and the overall workforce development system, to move adults into and along a career pathway. This report examines the extent to which local adult education providers' instructional approaches and coordination with other agencies reflect this link, highlighting the challenges providers experience in collecting related performance data.

- National Study of the Implementation of Adult Education Under the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act: Compendium of Survey Results from 2018-2019 – This report provides data tables from a survey of State directors and approximately 1,600 local providers of adult education in the 50 States and the District of Columbia. It also includes analyses of provider-level data obtained by states for the National Reporting System. These data include information on the types of organizations providing adult education services and on enrollment in each type of program offered. The data present a snapshot of implementation under the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act during the 2018-2019 program year.

- Second, the Connecting Adults to Success (CATS) Study seeks to expand evidence on how to support learners in their career pathways Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act encourages State agencies and local providers to find ways to facilitate postsecondary enrollment, credential attainment, and higher earnings for the nearly one million learners who participate in adult education programs. One promising approach is providing these learners with career navigators, namely staff whose dedicated role is to advise learners in career and college planning and to help them address challenges as they follow through on their plans. Navigators can be a significant expense for adult education providers, but the staff often receive little training despite their diverse backgrounds and thus may not be equipped with the knowledge and skills needed to effectively guide learners. This study is testing whether providing a promising model of training to navigators leads to improvements in learner outcomes.

The What Works Clearinghouse (WWC) at the Institute of Education Sciences reviewed the research on Washington State’s Integrated Basic Education Skills and Training (I-BEST) program and its impacts on community college students. Based on the research, the WWC found that I-BEST has positive effects on industry-recognized credential, certificate, or license completion; potentially positive effects on short-term employment; potentially positive effects on short-term earnings; and no discernible effects on credit accumulation. Read the full report and learn more about the studies that contributed to this rating.

Examples of other IES reviews and guides:

- Here is the LINCS Resource Collection Profile as well: https://lincs.ed.gov/professional-development/resource-collections/profile-8821

- Here is the LINCS Resource Collection Profile as well: https://lincs.ed.gov/professional-development/resource-collections/profile-8823

Additionally, the Institute of Education Sciences also supports field-initiated research to help understand and improve the ability of the adult education system to provide services. The researchers mentioned below have been conducting various research projects in partnership with adult education providers, primarily through the National Center for Education Research .

Examples of IES supported field-initiated projects and partnerships:

- The CREATE Adult Skills Research Network , comprised of six research teams and a network lead are focusing on technology-supported professional development , new assessment tools , and instruction in English language and civics instruction , numeracy , writing , and reading .

- The Georgia Partnership for Adult Education and Research (GPAER) , is a collaboration among researchers at Georgia State University and leadership at the Georgia Office of Adult Education to help understand adult literacy programs across the state.

- Using Process Data to Characterize Response Profiles and Test-Taking Behaviors of Low-Skilled Adult Responders on PIAAC Literacy and Numeracy Items is using PIAAC data to understand how adults with low basic skills (literacy and numeracy) interact with digital assessments and to determine the roles of low basic skills, fluency with digital tools, and assessment design on performance.

- The Center for the Study of Adult Literacy (CSAL) , developed a curriculum and technology for adults reading between the 3rd- and 8th-grade levels.

- The Career Pathways Programming for Lower-Skilled Adults and Immigrants conducted mixed-methods research in partnership with Chicago, Houston, and Miami to helped each city understand what types of career pathways adult education programs were offering and who was participating in such programing.

- The New York State Literacy Zone Researcher-Practitioner Partnership focused on improving the ability of case managers to help adult learners leverage wrap-around services and access and succeed in adult education and training programs.

- The Study of Effects of Transition Planning Process (TPP) on Adult Basic Skills Learners' GED® Attainment and Enrollment in Postsecondary Education , which was a partnership between Abt Associates and Oregon Higher Education Coordinating Commission, Office of Community Colleges and Workforce Development that aimed to evaluate the efficacy of the use of the Oregon Transition Planning Process, a text-messaging supplement to adult basic skills advising activities designed to help students complete their GED® credential and enroll in postsecondary courses.

Additional items of information:

- To learn more about funding opportunities through NCER’s standing topic area, Postsecondary and Adult Education , calling for additional research relevant to adult education, click here .

- To find additional IES publications relevant to adult learners, click here .

Literacy Information and Communication System (LINCS)

The Literacy Information and Communication System (LINCS) is a national leadership initiative of the U.S. Department of Education, Office of Career, Technical, and Adult Education (OCTAE) to expand evidence-based practice in the field of adult education.

LINCS demonstrates OCTAE's commitment to delivering high-quality, on-demand educational opportunities to practitioners of adult education, so those practitioners can help adult learners successfully transition to postsecondary education and 21st century jobs.

One of five components of LINC S, the LINCS Resource Collection, provides online access to freely-available high-quality, evidence-based, vetted materials to help adult education practitioners and state and local staff improve programs, services, instruction, and teacher quality. Spanning 13 topic areas, the collection includes research articles and briefs.

Related Links

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Adults With Special Educational Needs Participating in Interactive Learning Environments in Adult Education: Educational, Social, and Personal Improvements. A Case Study

Javier díez-palomar.

1 Department of Linguistic and Literary Education and Teaching and Learning of Experimental Sciences and Mathematics, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

María del Socorro Ocampo Castillo

2 Instituto de Mediación Pedagógica, Mexico City, Mexico

Ariadna Munté Pascual

3 Social Work Training and Research Section, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

Esther Oliver

4 Department of Sociology, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

Associated Data

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Previous scientific contributions show that interactive learning environments have contributed to promoting learners' learning and development, as interaction and dialogue are key components of learning. When it comes to students with special needs, increasing evidence has demonstrated learning improvements through interaction and dialogue. However, most research focuses on children's education, and there is less evidence of how these learning environments can promote inclusion in adult learners with SEN. This article is addressed to analyse a case study of an interactive learning environment shared by adults with and without special needs. This case shows several improvements identified by adult learners with special needs participating in this study. Based on a documental analysis and a qualitative study, this study analyses a context of participatory and dialogic adult education. From the analysis undertaken, the main results highlight some improvements identified in the lives of these adult women and men with SEN, covering educational improvements, increased feeling of social inclusion, and enhanced well-being.

Introduction

The World Health Organisation estimates that more than one billion people live with some form of disability (WHO, 2020 ), corresponding to ~15% of the world's population. It states that 3.8% of people aged 15 years and older have significant functioning difficulties and require assistance from various services. Furthermore, according to UNESCO, people with disabilities are more likely to be out of school or drop out of school before completing primary or secondary education (UNESCO UIL | UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning UIS, 2017 ).

According to UNESCO ( 2019 ), adults with disabilities are considered one of the most vulnerable groups in society. The limited possibilities to attend or complete school as children led to low literacy capacity as adults and overall educational achievement, which negatively influences their participation in further education following the Mathew Effect, which states that those with more education get more. Those with less education get little or nothing. Adults living with disabilities are increasingly being a target group for adult learning and teaching in different countries. However, they are still poorly visible and continue facing barriers in accessing adult learning and education.

To achieve the fourth goal of the Sustainable Development Goals (UN, 2015 ) (ensuring inclusive, equitable and quality education and promoting lifelong learning opportunities), it is necessary to investigate which educational actions serve this purpose, in which contexts they occur, and the role that adult education can have in it.

In this article, “adult education” is used in a sense given to it by the international scientific community at CONFINTEA V (UNESCO, 1997 ), as it can be read in the Hamburg Declaration . The impact of the fifth Conférence Internationale sur l'Education des Adultes (CONFINTEA V) held in this German city in 1997 in the definition of EU policies on adult education and lifelong learning is relevant to mention. In the Hamburg event (1997) many debates were held about the role of adult education in a changing environment, being adult learning understood as an integral part of lifelong learning. Learners were conceptualised as subjects (not objects) of their learning processes and adult education was connected to community learning and to dialogue between cultures. Adult education was related to social and economic development struggles, to justice and equality, being a potential way for individual empowerment and social transformation (Oliver, 2010 ). CONFINTEA VI (2009) continued being a relevant platform to further dialogue about formal and non-formal adult learning policies at the international level, establishing ambitious goals and urging to real actions towards advancing to favour that adults enjoy their human right of lifelong learning. In the next future, CONFINTEA VII (2022) will continue this line contributing to the analysis of efficient learning and adult education policies from the lifelong learning perspectives, taking into account the Sustainable Development Goals from the United Nations (UNESCO). Thus, this understanding of adult education is also related to the idea of democracy, social justice and solidarity that some communities are promoting to enhance the learning opportunities for all students (Vanegas et al., 2019 ).

In that sense, adult education encompasses formal, non-formal and the whole range of informal and occasional learning in multicultural societies. This concept includes diverse learning spaces, among others: home, school, community and workplace.

Key historical and political milestones influence the development of the adult education in Europe.

The White Paper in Education (European Commission, 1995 ) represented a relevant moment in the understanding of the advancement of Adult Education policies in the European Union. It signified the promotion of education and training in Europe in a context of technological and economic change, proposing objectives to guarantee a high-quality education for all. Specific EC action programs, such as the Socrates programme with a section of adult education, were an important milestone in this context, followed by the Grundtvig action, focused on adult education and other educational pathways to promote lifelong learning with a European dimension.

In 2001, the European Ministers of Education defined the main goals to be achieved, including improving the quality and effectiveness of educational and training systems. At that moment, it was already recognised that people with more difficulties to be engaged in lifelong learning processes had a greater risk of suffering social exclusion (Council of the European Union, 2001 ). This implied efforts to promote social inclusion in AE, to overcome barriers and favour more significant access to different educational and training systems for all. The case analysed in this article is also addressed to show how several of these barriers can be overcome through a concrete interactive learning environment in the case of the adult learners participating in the study.

Similarly, in line to favour lifelong learning strategies across Europe, the Memorandum on Lifelong Learning (Commission of the European Communities, 2000 ) launched a consultation process across Europe to identify strategies and ways to foster lifelong learning opportunities for all. Lifelong learning was considered an umbrella for a wide diversity of learning processes, from pre-school to post-retirement, including informal and non-formal learning. From this process of consultation, the establishment of a European area of Lifelong Learning was proposed. It was thought to create a common frame in Europe to facilitate mobility and more coherent use of the existing resources towards lifelong learning, promoting the centrality of the learner within the learning process, equal opportunities and the quality and relevance of learning opportunities (Commission of the European Communities, 2001 ). Relevant stress for analysing learning needs more precisely and to respond to the needs of diverse social groups was identified. In 2006, for example, the EC Communication It is never too late to learn (Commission of the European Communities, 2006 ) encouraged the Member States to increase and consolidate lifelong learning opportunities for adults and make them accessible. This article responds to the need to provide scientific evidence on the improvements of a concrete interactive learning environment in specific learning and personal trajectories of adults with special needs. Since the Council Resolution on a renewed European agenda for adult learning (Council of the European Union, 2011 ), relevant emphasis was given to promote the acquisition of work skills, active citizenship and personal development and fulfilment, favouring flexible learning environments and mechanisms to assist adult learners.

Consequently, today Adult Education is intrinsically linked to lifelong learning, affects the actors involved and envisages the extension of multiple educational networks encompassing all possible institutions. Adult education understood as a common good is achieved in a society when there are accessibility, availability, affordability and social commitment to its functioning (Boyadjieva and Ilieva-Trichkova, 2018 ).

According to previous research (Desjardins, 2019 ; Hamdan et al., 2019 ) adult education has positive effects on a wide range of aspects, such as adult empowerment, social inclusion, social networking, motivation for learning, work-related aspects, including improved job and career prospects, performance and earnings, job satisfaction and commitment to work and innovative skills, as well as other parts of everyday life (Moni et al., 2011 ; Ryan and Griffiths, 2015 ; Magro, 2019 ).

Adult education can also have an impact on adults with special educational needs. By “adults with special educational needs” we mean people who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual, or sensory impairments which, in interaction with various barriers, may prevent their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others (UN, 2006 ). Recent research in education suggests that learning environments based on inclusive interactions help promote learning and development of students with Special Educational Needs (SEN).

In the case of children with special educational needs, previous research suggests that their participation in educational activities developed in inclusive, interactive environments has clear benefits on learning (Duque et al., 2020 ). However, this result has not yet been discussed in the case of adults.

According to the findings of Moni et al. ( 2011 ) with adults with SEN in community-based adult education contexts, community organisations contribute to the literacy processes of participants with SEN in these programmes. This study points out that, for many years, functional skills training (such as cooking and manual jobs) has dominated community-based programmes for people with SEN and there has been limited recognition of the role that literacy can play in improving the quality of life of learners with SEN through lifelong learning (p. 474). There is currently no research investigating the degree of literacy needed by adults with SEN in a variety of contexts in adulthood. Depending on the adults' needs, literacy needs can vary widely from employment, family, daily living challenges, leisure and recreation, even to the degree of literacy needed in specific areas such as computers/internet and the broad area of health issues. In any case, it is a basic instrumental knowledge necessary in diverse contexts; therefore it is relevant to identify venues to enhance its learning.

The development of social competences is an integral part of education of this collective. According to de Morais and Rapsová ( 2019 ), several specific criteria have to be considered when working with people with special educational needs. Some of them are: (1) To perceive the education of older people as a lifelong process, (2) to take into account the possibilities of education in the system, (3) to recognise the needs and interests of individuals, (4) to enable education without discrimination, (5) to improve the quality of life through education and occupations, and (6) to make use of their life experience for themselves and society as an asset (de Morais and Rapsová, 2019 ).

In this sense, training focused on social aspects can be beneficial because competences to manage a wide range of social situations provide specific protection in cases of stress, tensions and conflicts. A reasonable level of social competences significantly determines the ability to cope with everyday stress, create excellent and non-conflictual interpersonal relationships, and find more efficient ways of resolving conflicts and misunderstandings. Socially competent people play an active role in their lives, can express their needs and achieve their personal goals (Wilkinson and Canter, 2005 ; Praško et al., 2007 ).

Some studies focus on analysing the participation of adults with SEN in training and lifelong learning activities from a labour economic perspective (Myklebust and Båtevik, 2014 ; Båtevik, 2019 ) and highlight the value of receiving formal education for the acquisition of future employment opportunities. However, these studies do not delve into the educational characteristics of such learning opportunities for this specific group.

Other research highlights the importance of collaborative work between caregivers of people with learning difficulties and educators in charge of training programmes as this raises awareness of the value of education for these adults and facilitates the establishment of learning opportunities in the everyday lives of people with learning difficulties (Wilson and Hunter, 2010 ; Brown, 2020 ).

It is known that interaction and dialogue are critical components of learning (Flecha, 2000 ; Aubert et al., 2009 ; Racionero, 2017 ). Following the sociocultural theory of learning initiated by Vygotsky, learning and cognitive development are explained as cultural processes that occur in interaction with others (Vygotsky, 1978 ; Rogoff, 1993 ). Specifically, Vygotsky develops how the human learning is understood as presupposing a specific social nature and a process by which children grow into an intellectual life of those around them (Vygotsky, 1978 : 78). Similarly, Bruner ( 1996 ) also highlights that learning is an interactive process in which people learn from each other and Wells ( 1999 ) argues about the way human beings built their knowledge about the world through a common action and about the way this knowledge is later used in their collective action.

Subsequently, a dialogic turn in educational psychology (Racionero and Padrós, 2010 ) explained that interactive and dialogical learning environments improve students' learning opportunities and outcomes. The project INCLUD-ED: Strategies for Inclusion and Social Cohesion in Europe from Education identified a set of Successful Educational Actions (SEAs) (Flecha, 2015 ) that have been shown to contribute to improved learning outcomes and social cohesion (Soler-Gallart and Rodrigues de Mello, 2020 ). These SEAs have been shown to increase learning efficiency, i.e., instrumental tools needed to live included in today's society (basic and transversal skills), and generate equity. Subsequent research has reinforced this evidence, showing that organising teaching based on interaction and dialogue simultaneously improves performance and coexistence among the student group (García-Carrión et al., 2016 ). Interactive Groups and Dialogical Gatherings are two of the SEAs that allow this type of teaching organisation to be carried out so that high levels of learning are achieved in safe and supportive spaces that promote friendly relationships and better coexistence. Interactive groups -IGs- (Valls and Kyriakides, 2013 ) are a way to organise the classroom in which the students are split in groups, with a volunteer facilitating that all participants in the group interact with each other when solving the task. IGs draw on to the principles set up by the “Dialogic Learning” theory (Flecha, 2000 ), that is: participants engage in an egalitarian dialogue in which they exchange statements (arguments, reasons, facts, etc.) drawing on validity claims, rather than on their “power” position within the group. Dialogical Gatherings work on the basis of dialogic reading: participants read universal readings, and then they share their reading in a gathering, where everyone can contribute reading aloud the fragment they want to share. Then all participants in the gathering can comment or discuss on the fragment, reaching a distributed (Hutchins, 2000 ) understanding of it throughout the dialogue (Bakhtin, 2010 , Flecha, 2000 ). Dialogic Gatherings include different types, such as Dialogic Literary Gatherings (participants use universal readings), Dialogic Music Gatherings (participants use universal plays), Dialogic Mathematics Readings (participants read mathematics masterpieces), Dialogic Arts Gatherings (participants share their comments on universal paintings or sculpture), etc.

These contributions also apply to students with disabilities, as they benefit from interactive learning contexts to progress to higher levels of learning and higher stages of development. Duque et al. ( 2020 ) state that interaction and dialogue positively impact students with SEN. According to the results they present, participating in activities such as interactive groups or dialogical discussions with the rest of the students, makes students with SEN improve their learning and social integration skills with the rest of the group. Interacting with peers with higher academic competence levels under the same curriculum allows students with special needs to make more significant learning progress in mainstream schools. Each person, regardless of their condition, can contribute from their cultural intelligence to the learning process. Previous research suggests that placing students with SEN in the mainstream classroom, together with the rest of their peers, and promoting interactions based on egalitarian dialogue (Flecha, 2000 ), has benefits both on the learning of students with SEN and the rest of the students (Fernandez-Villardon et al., 2020 ). Inclusion fosters the acquisition of academic skills (Dessemontet et al., 2012 ), improves educational outcomes (Nahmias et al., 2014 ) and intellectual engagement (Mortier et al., 2009 ) of students with SEN. It also has positive impacts on social development, as interacting with the rest of the student body leads these students with SEN to improve their social skills and the acceptance they receive from other students (Meadan and Monda-Amaya, 2008 ; Draper et al., 2019 ; García-Carrión et al., 2019 ).