- What is New

- Download Your Software

- Behavioral Research

- Software for Consumer Research

- Software for Human Factors R&D

- Request Live Demo

- Contact Sales

Sensor Hardware

We carry a range of biosensors from the top hardware producers. All compatible with iMotions

iMotions for Higher Education

Imotions for business.

How Does Environmental Ergonomics Affect Behavior?

Ergonomics Testing

Morten Pedersen

Can You Build Your Own Eye Tracking Glasses?

News & events.

- iMotions Lab

- iMotions Online

- Eye Tracking

- Eye Tracking Screen Based

- Eye Tracking VR

- Eye Tracking Glasses

- Eye Tracking Webcam

- FEA (Facial Expression Analysis)

- Voice Analysis

- EDA/GSR (Electrodermal Activity)

- EEG (Electroencephalography)

- ECG (Electrocardiography)

- EMG (Electromyography)

- Respiration

- iMotions Lab: New features

- iMotions Lab: Developers

- EEG sensors

- Sensory and Perceptual

- Consumer Inights

- Human Factors R&D

- Work Environments, Training and Safety

- Customer Stories

- Published Research Papers

- Document Library

- Customer Support Program

- Help Center

- Release Notes

- Contact Support

- Partnerships

- Mission Statement

- Ownership and Structure

- Executive Management

- Job Opportunities

Publications

- Newsletter Sign Up

The Importance of Research Design: A Comprehensive Guide

Research design plays a crucial role in conducting scientific studies and gaining meaningful insights. A well-designed research enhances the validity and reliability of the findings and allows for the replication of studies by other researchers. This comprehensive guide will provide an in-depth understanding of research design, its key components, different types, and its role in scientific inquiry. Furthermore, it will discuss the necessary steps in developing a research design and highlight some of the challenges that researchers commonly face.

Table of Contents

Understanding research design.

Research design refers to the overall plan or strategy that outlines how a study is conducted. It serves as a blueprint for researchers, guiding them in their investigation, and helps ensure that the study objectives are met. Understanding research design is essential for researchers to effectively gather and analyze data to answer research questions.

When embarking on a research study, researchers must carefully consider the design they will use. The design determines the structure of the study, including the research questions, data collection methods, and analysis techniques. It provides clarity on how the study will be conducted and helps researchers determine the best approach to achieve their research objectives. A well-designed study increases the chances of obtaining valid and reliable results.

Definition and Purpose of Research Design

Research design is the framework that outlines the structure of a study, including the research questions, data collection methods, and analysis techniques. It provides a systematic approach to conducting research and ensures that all aspects of the study are carefully planned and executed.

The purpose of research design is to provide a clear roadmap for researchers to follow. It helps them define the research questions they want to answer and identify the variables they will study. By clearly defining the purpose of the study, researchers can ensure that their research design aligns with their objectives.

Key Components of Research Design

A research design consists of several key components that influence the study’s validity and reliability. These components include the research questions, variables and operational definitions, sampling techniques, data collection methods, and statistical analysis procedures.

The research questions are the foundation of any study. They guide the entire research process and help researchers focus their efforts. By formulating clear and concise research questions, researchers can ensure that their study addresses the specific issues they want to investigate.

Variables and operational definitions are also crucial components of research design. Variables are the concepts or phenomena that researchers want to measure or study. Operational definitions provide a clear and specific description of how these variables will be measured or observed. By clearly defining variables and their operational definitions, researchers can ensure that their study is consistent and replicable.

Sampling techniques play a vital role in research design as well. Researchers must carefully select the participants or samples they will study to ensure that their findings are generalizable to the larger population. Different sampling techniques, such as random sampling or purposive sampling, can be used depending on the research objectives and constraints.

Data collection methods are another important component of research design. Researchers must decide how they will collect data, whether through surveys, interviews, observations, or experiments. The choice of data collection method depends on the research questions and the type of data needed to answer them.

Finally, statistical analysis procedures are used to analyze the collected data and draw meaningful conclusions. Researchers must determine the appropriate statistical tests or techniques to use based on the nature of their data and research questions. The choice of statistical analysis procedures ensures that the data is analyzed accurately and that the results are valid and reliable.

Types of Research Design

Research design encompasses various types that researchers can choose depending on their research goals and the nature of the phenomenon being studied. Understanding the different types of research design is essential for researchers to select the most appropriate approach for their study.

When embarking on a research project, researchers must carefully consider the design they will employ. The design chosen will shape the entire study, from the data collection process to the analysis and interpretation of results. Let’s explore some of the most common types of research design in more detail.

Experimental Design

Experimental design involves manipulating one or more variables to observe their effect on the dependent variable. This type of design allows researchers to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables by controlling for extraneous factors. Experimental design often relies on random assignment and control groups to minimize biases.

Imagine a group of researchers interested in studying the effects of a new teaching method on student performance. They could randomly assign students to two groups: one group would receive instruction using the new teaching method, while the other group would receive instruction using the traditional method. By comparing the performance of the two groups, the researchers can determine whether the new teaching method has a significant impact on student learning.

Experimental design provides a strong foundation for making causal claims, as it allows researchers to control for confounding variables and isolate the effects of the independent variable. However, it may not always be feasible or ethical to manipulate variables, leading researchers to explore alternative designs.

Free 44-page Experimental Design Guide

For Beginners and Intermediates

- Introduction to experimental methods

- Respondent management with groups and populations

- How to set up stimulus selection and arrangement

Non-Experimental Design

Non-experimental design is used when it is not feasible or ethical to manipulate variables. This design relies on naturally occurring variations in data and focuses on observing and describing relationships between variables. Non-experimental design can be useful for exploratory research or when studying phenomena that cannot be controlled, such as human behavior.

For instance, researchers interested in studying the relationship between socioeconomic status and health outcomes may collect data from a large sample of individuals and analyze the existing differences. By examining the data, they can determine whether there is a correlation between socioeconomic status and health, without manipulating any variables.

Non-experimental design allows researchers to study real-world phenomena in their natural setting, providing valuable insights into complex social, psychological, and economic processes. However, it is important to note that non-experimental designs cannot establish causality, as there may be other variables at play that influence the observed relationships.

Quasi-Experimental Design

Quasi-experimental design resembles experimental design but lacks the element of random assignment. In situations where random assignment is not possible or practical, researchers can utilize quasi-experimental designs to gather data and make inferences. However, caution must be exercised when drawing causal conclusions from quasi-experimental studies.

Consider a scenario where researchers are interested in studying the effects of a new drug on patient recovery time. They cannot randomly assign patients to receive the drug or a placebo due to ethical considerations. Instead, they can compare the recovery times of patients who voluntarily choose to take the drug with those who do not. While this design allows for data collection and analysis, it is important to acknowledge that other factors, such as patient motivation or severity of illness, may influence the observed outcomes.

Quasi-experimental designs are valuable when experimental designs are not feasible or ethical. They provide an opportunity to explore relationships and gather data in real-world contexts. However, researchers must be cautious when interpreting the results, as causal claims may be limited due to the lack of random assignment.

By understanding the different types of research design, researchers can make informed decisions about the most appropriate approach for their study. Each design offers unique advantages and limitations, and the choice depends on the research question, available resources, and ethical considerations. Regardless of the design chosen, rigorous methodology and careful data analysis are crucial for producing reliable and valid research findings.

The Role of Research Design in Scientific Inquiry

A well-designed research study enhances the validity and reliability of the findings. Research design plays a crucial role in ensuring the scientific rigor of a study and facilitates the replication of studies by other researchers. Understanding the role of research design in scientific inquiry is vital for researchers to conduct impactful and robust research.

Ensuring Validity and Reliability

Research design plays a critical role in ensuring the validity and reliability of the study’s findings. Validity refers to the degree to which the study measures what it intends to measure, while reliability pertains to the consistency and stability of the results. Through careful consideration of the research design, researchers can minimize potential biases and increase the accuracy of their measurements.

Facilitating Replication of Studies

A robust research design allows for the replication of studies by other researchers. Replication plays a vital role in the scientific process as it helps confirm the validity and generalizability of research findings. By clearly documenting the research design, researchers enable others to reproduce the study and validate the results, thereby contributing to the cumulative knowledge in a field.

Steps in Developing a Research Design

Developing a research design involves a systematic process that includes several important steps. Researchers need to carefully consider each step to ensure that their study is well-designed and capable of addressing their research questions effectively.

Identifying Research Questions

The first step in developing a research design is to identify and define the research questions or hypotheses. Researchers need to clearly articulate what they aim to investigate and what specific information they want to gather. Clear research questions provide guidance for the subsequent steps in the research design process.

Selecting Appropriate Design Type

Once the research questions are identified, researchers need to select the most appropriate type of research design. The choice of design depends on various factors, including the research goals, the nature of the research questions, and the available resources. Careful consideration of these factors is crucial to ensure that the chosen design aligns with the study objectives.

Determining Data Collection Methods

After selecting the research design, researchers need to determine the most suitable data collection methods. Depending on the research questions and the type of data required, researchers can utilize a range of methods, such as surveys, interviews, observations, or experiments. The chosen methods should align with the research objectives and allow for the collection of high-quality data.

One of the most important considerations when designing a study in human behavior research is participant recruitment. We have written a comprehensive guide on best practices and pitfalls to be aware of when recruiting participants, which can be read here.

Enhancing Research Design with iMotions and Biosensors

Introduction to enhanced research design.

In the realm of scientific studies, especially within human cognitive-behavioral research, the deployment of advanced technologies such as iMotions software and biosensors has revolutionized research design. This chapter delves into how these technologies can be integrated into various research designs, improving the depth, accuracy, and reliability of scientific inquiries.

Integrating iMotions in Research Design

Imotions software: a key to multimodal data integration.

The iMotions platform stands as a pivotal tool in modern research design. It’s designed to integrate data from a plethora of biosensors, providing a comprehensive analysis of human behavior. This software facilitates the synchronizing of physiological, cognitive, and emotional responses with external stimuli, thus enriching the understanding of human behavior in various contexts.

Biosensors: Gateways to Deeper Insights

Biosensors, including eye trackers, EEG, GSR, ECG, and facial expression analysis tools, provide nuanced insights into the subconscious and conscious aspects of human behavior. These tools help researchers in capturing data that is often unattainable through traditional data collection methods like surveys and interviews.

Application in Different Research Designs

- Eye Tracking : In experimental designs, where the impact of visual stimuli is crucial, eye trackers can reveal how subjects interact with these stimuli, thereby offering insights into cognitive processes and attention.

- EEG : EEG biosensors allow researchers to monitor brain activity in response to controlled experimental manipulations, offering a window into cognitive and emotional responses.

- Facial Expression Analysis : In observational studies, analyzing facial expressions can provide objective data on emotional responses in natural settings, complementing subjective self-reports.

- GSR/EDA : These tools measure physiological arousal in real-life scenarios, giving researchers insights into emotional states without the need for intrusive measures.

- EMG : In studies where direct manipulation isn’t feasible, EMG can indicate subtle responses to stimuli, which might be overlooked in traditional observational methods.

- ECG/PPG : These sensors can be used to understand the impact of various interventions on physiological states such as stress or relaxation.

Streamlining Research Design with iMotions

The iMotions platform offers a streamlined process for integrating various biosensors into a research design. Researchers can easily design experiments, collect multimodal data, and analyze results in a unified interface. This reduces the complexity often associated with handling multiple streams of data and ensures a cohesive and comprehensive research approach.

Integrating iMotions software and biosensors into research design opens new horizons for scientific inquiry. This technology enhances the depth and breadth of data collection, paving the way for more nuanced and comprehensive findings.

Whether in experimental, non-experimental, or quasi-experimental designs, iMotions and biosensors offer invaluable tools for researchers aiming to uncover the intricate layers of human behavior and cognitive processes. The future of research design is undeniably intertwined with the advancements in these technologies, leading to more robust, reliable, and insightful scientific discoveries.

Challenges in Research Design

Research design can present several challenges that researchers need to overcome to conduct reliable and valid studies. Being aware of these challenges is essential for researchers to address them effectively and ensure the integrity of their research.

Ethical Considerations

Research design must adhere to ethical guidelines and principles to protect the rights and well-being of participants. Researchers need to obtain informed consent, ensure participant confidentiality, and minimize potential harm or discomfort. Ethical considerations should be carefully integrated into the research design to promote ethical research practices.

Practical Limitations

Researchers often face practical limitations that may impact the design and execution of their studies. Limited resources, time constraints, access to participants or data, and logistical challenges can pose obstacles during the research process. Researchers need to navigate these limitations and make thoughtful choices to ensure the feasibility and quality of their research.

Research design is a vital aspect of conducting scientific studies. It provides a structured framework for researchers to answer their research questions and obtain reliable and valid results. By understanding the different types of research design and following the necessary steps in developing a research design, researchers can enhance the rigor and impact of their studies.

However, researchers must also be mindful of the challenges they may encounter, such as ethical considerations and practical limitations, and take appropriate measures to address them. Ultimately, a well-designed research study contributes to the advancement of knowledge and promotes evidence-based decision-making in various fields.

Last edited

About the author

See what is next in human behavior research

Follow our newsletter to get the latest insights and events send to your inbox.

Related Posts

Exploring Mobile Eye Trackers: How Eye Tracking Glasses Work and Their Applications

Understanding Screen-Based Eye Trackers: How They Work and Their Applications

Product guides.

Can you use HTC VIVE Pro Eye for eye tracking research?

Top 5 Publications of 2023

Laila Mowla

You might also like these

Human Factors and UX

The World Runs on Behavioral Insights

Consumer Insights

New OSM Reference System from iMotions

Case Stories

Explore Blog Categories

Best Practice

Collaboration, product news, research fundamentals, research insights, 🍪 use of cookies.

We are committed to protecting your privacy and only use cookies to improve the user experience.

Chose which third-party services that you will allow to drop cookies. You can always change your cookie settings via the Cookie Settings link in the footer of the website. For more information read our Privacy Policy.

- gtag This tag is from Google and is used to associate user actions with Google Ad campaigns to measure their effectiveness. Enabling this will load the gtag and allow for the website to share information with Google. This service is essential and can not be disabled.

- Livechat Livechat provides you with direct access to the experts in our office. The service tracks visitors to the website but does not store any information unless consent is given. This service is essential and can not be disabled.

- Pardot Collects information such as the IP address, browser type, and referring URL. This information is used to create reports on website traffic and track the effectiveness of marketing campaigns.

- Third-party iFrames Allows you to see thirdparty iFrames.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 20 March 2023.

A research design is a strategy for answering your research question using empirical data. Creating a research design means making decisions about:

- Your overall aims and approach

- The type of research design you’ll use

- Your sampling methods or criteria for selecting subjects

- Your data collection methods

- The procedures you’ll follow to collect data

- Your data analysis methods

A well-planned research design helps ensure that your methods match your research aims and that you use the right kind of analysis for your data.

Table of contents

Step 1: consider your aims and approach, step 2: choose a type of research design, step 3: identify your population and sampling method, step 4: choose your data collection methods, step 5: plan your data collection procedures, step 6: decide on your data analysis strategies, frequently asked questions.

- Introduction

Before you can start designing your research, you should already have a clear idea of the research question you want to investigate.

There are many different ways you could go about answering this question. Your research design choices should be driven by your aims and priorities – start by thinking carefully about what you want to achieve.

The first choice you need to make is whether you’ll take a qualitative or quantitative approach.

Qualitative research designs tend to be more flexible and inductive , allowing you to adjust your approach based on what you find throughout the research process.

Quantitative research designs tend to be more fixed and deductive , with variables and hypotheses clearly defined in advance of data collection.

It’s also possible to use a mixed methods design that integrates aspects of both approaches. By combining qualitative and quantitative insights, you can gain a more complete picture of the problem you’re studying and strengthen the credibility of your conclusions.

Practical and ethical considerations when designing research

As well as scientific considerations, you need to think practically when designing your research. If your research involves people or animals, you also need to consider research ethics .

- How much time do you have to collect data and write up the research?

- Will you be able to gain access to the data you need (e.g., by travelling to a specific location or contacting specific people)?

- Do you have the necessary research skills (e.g., statistical analysis or interview techniques)?

- Will you need ethical approval ?

At each stage of the research design process, make sure that your choices are practically feasible.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Within both qualitative and quantitative approaches, there are several types of research design to choose from. Each type provides a framework for the overall shape of your research.

Types of quantitative research designs

Quantitative designs can be split into four main types. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs allow you to test cause-and-effect relationships, while descriptive and correlational designs allow you to measure variables and describe relationships between them.

With descriptive and correlational designs, you can get a clear picture of characteristics, trends, and relationships as they exist in the real world. However, you can’t draw conclusions about cause and effect (because correlation doesn’t imply causation ).

Experiments are the strongest way to test cause-and-effect relationships without the risk of other variables influencing the results. However, their controlled conditions may not always reflect how things work in the real world. They’re often also more difficult and expensive to implement.

Types of qualitative research designs

Qualitative designs are less strictly defined. This approach is about gaining a rich, detailed understanding of a specific context or phenomenon, and you can often be more creative and flexible in designing your research.

The table below shows some common types of qualitative design. They often have similar approaches in terms of data collection, but focus on different aspects when analysing the data.

Your research design should clearly define who or what your research will focus on, and how you’ll go about choosing your participants or subjects.

In research, a population is the entire group that you want to draw conclusions about, while a sample is the smaller group of individuals you’ll actually collect data from.

Defining the population

A population can be made up of anything you want to study – plants, animals, organisations, texts, countries, etc. In the social sciences, it most often refers to a group of people.

For example, will you focus on people from a specific demographic, region, or background? Are you interested in people with a certain job or medical condition, or users of a particular product?

The more precisely you define your population, the easier it will be to gather a representative sample.

Sampling methods

Even with a narrowly defined population, it’s rarely possible to collect data from every individual. Instead, you’ll collect data from a sample.

To select a sample, there are two main approaches: probability sampling and non-probability sampling . The sampling method you use affects how confidently you can generalise your results to the population as a whole.

Probability sampling is the most statistically valid option, but it’s often difficult to achieve unless you’re dealing with a very small and accessible population.

For practical reasons, many studies use non-probability sampling, but it’s important to be aware of the limitations and carefully consider potential biases. You should always make an effort to gather a sample that’s as representative as possible of the population.

Case selection in qualitative research

In some types of qualitative designs, sampling may not be relevant.

For example, in an ethnography or a case study, your aim is to deeply understand a specific context, not to generalise to a population. Instead of sampling, you may simply aim to collect as much data as possible about the context you are studying.

In these types of design, you still have to carefully consider your choice of case or community. You should have a clear rationale for why this particular case is suitable for answering your research question.

For example, you might choose a case study that reveals an unusual or neglected aspect of your research problem, or you might choose several very similar or very different cases in order to compare them.

Data collection methods are ways of directly measuring variables and gathering information. They allow you to gain first-hand knowledge and original insights into your research problem.

You can choose just one data collection method, or use several methods in the same study.

Survey methods

Surveys allow you to collect data about opinions, behaviours, experiences, and characteristics by asking people directly. There are two main survey methods to choose from: questionnaires and interviews.

Observation methods

Observations allow you to collect data unobtrusively, observing characteristics, behaviours, or social interactions without relying on self-reporting.

Observations may be conducted in real time, taking notes as you observe, or you might make audiovisual recordings for later analysis. They can be qualitative or quantitative.

Other methods of data collection

There are many other ways you might collect data depending on your field and topic.

If you’re not sure which methods will work best for your research design, try reading some papers in your field to see what data collection methods they used.

Secondary data

If you don’t have the time or resources to collect data from the population you’re interested in, you can also choose to use secondary data that other researchers already collected – for example, datasets from government surveys or previous studies on your topic.

With this raw data, you can do your own analysis to answer new research questions that weren’t addressed by the original study.

Using secondary data can expand the scope of your research, as you may be able to access much larger and more varied samples than you could collect yourself.

However, it also means you don’t have any control over which variables to measure or how to measure them, so the conclusions you can draw may be limited.

As well as deciding on your methods, you need to plan exactly how you’ll use these methods to collect data that’s consistent, accurate, and unbiased.

Planning systematic procedures is especially important in quantitative research, where you need to precisely define your variables and ensure your measurements are reliable and valid.

Operationalisation

Some variables, like height or age, are easily measured. But often you’ll be dealing with more abstract concepts, like satisfaction, anxiety, or competence. Operationalisation means turning these fuzzy ideas into measurable indicators.

If you’re using observations , which events or actions will you count?

If you’re using surveys , which questions will you ask and what range of responses will be offered?

You may also choose to use or adapt existing materials designed to measure the concept you’re interested in – for example, questionnaires or inventories whose reliability and validity has already been established.

Reliability and validity

Reliability means your results can be consistently reproduced , while validity means that you’re actually measuring the concept you’re interested in.

For valid and reliable results, your measurement materials should be thoroughly researched and carefully designed. Plan your procedures to make sure you carry out the same steps in the same way for each participant.

If you’re developing a new questionnaire or other instrument to measure a specific concept, running a pilot study allows you to check its validity and reliability in advance.

Sampling procedures

As well as choosing an appropriate sampling method, you need a concrete plan for how you’ll actually contact and recruit your selected sample.

That means making decisions about things like:

- How many participants do you need for an adequate sample size?

- What inclusion and exclusion criteria will you use to identify eligible participants?

- How will you contact your sample – by mail, online, by phone, or in person?

If you’re using a probability sampling method, it’s important that everyone who is randomly selected actually participates in the study. How will you ensure a high response rate?

If you’re using a non-probability method, how will you avoid bias and ensure a representative sample?

Data management

It’s also important to create a data management plan for organising and storing your data.

Will you need to transcribe interviews or perform data entry for observations? You should anonymise and safeguard any sensitive data, and make sure it’s backed up regularly.

Keeping your data well organised will save time when it comes to analysing them. It can also help other researchers validate and add to your findings.

On their own, raw data can’t answer your research question. The last step of designing your research is planning how you’ll analyse the data.

Quantitative data analysis

In quantitative research, you’ll most likely use some form of statistical analysis . With statistics, you can summarise your sample data, make estimates, and test hypotheses.

Using descriptive statistics , you can summarise your sample data in terms of:

- The distribution of the data (e.g., the frequency of each score on a test)

- The central tendency of the data (e.g., the mean to describe the average score)

- The variability of the data (e.g., the standard deviation to describe how spread out the scores are)

The specific calculations you can do depend on the level of measurement of your variables.

Using inferential statistics , you can:

- Make estimates about the population based on your sample data.

- Test hypotheses about a relationship between variables.

Regression and correlation tests look for associations between two or more variables, while comparison tests (such as t tests and ANOVAs ) look for differences in the outcomes of different groups.

Your choice of statistical test depends on various aspects of your research design, including the types of variables you’re dealing with and the distribution of your data.

Qualitative data analysis

In qualitative research, your data will usually be very dense with information and ideas. Instead of summing it up in numbers, you’ll need to comb through the data in detail, interpret its meanings, identify patterns, and extract the parts that are most relevant to your research question.

Two of the most common approaches to doing this are thematic analysis and discourse analysis .

There are many other ways of analysing qualitative data depending on the aims of your research. To get a sense of potential approaches, try reading some qualitative research papers in your field.

A sample is a subset of individuals from a larger population. Sampling means selecting the group that you will actually collect data from in your research.

For example, if you are researching the opinions of students in your university, you could survey a sample of 100 students.

Statistical sampling allows you to test a hypothesis about the characteristics of a population. There are various sampling methods you can use to ensure that your sample is representative of the population as a whole.

Operationalisation means turning abstract conceptual ideas into measurable observations.

For example, the concept of social anxiety isn’t directly observable, but it can be operationally defined in terms of self-rating scores, behavioural avoidance of crowded places, or physical anxiety symptoms in social situations.

Before collecting data , it’s important to consider how you will operationalise the variables that you want to measure.

The research methods you use depend on the type of data you need to answer your research question .

- If you want to measure something or test a hypothesis , use quantitative methods . If you want to explore ideas, thoughts, and meanings, use qualitative methods .

- If you want to analyse a large amount of readily available data, use secondary data. If you want data specific to your purposes with control over how they are generated, collect primary data.

- If you want to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables , use experimental methods. If you want to understand the characteristics of a research subject, use descriptive methods.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, March 20). Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 31 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/research-design/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Research Design 101

Everything You Need To Get Started (With Examples)

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewers: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) & Kerryn Warren (PhD) | April 2023

Navigating the world of research can be daunting, especially if you’re a first-time researcher. One concept you’re bound to run into fairly early in your research journey is that of “ research design ”. Here, we’ll guide you through the basics using practical examples , so that you can approach your research with confidence.

Overview: Research Design 101

What is research design.

- Research design types for quantitative studies

- Video explainer : quantitative research design

- Research design types for qualitative studies

- Video explainer : qualitative research design

- How to choose a research design

- Key takeaways

Research design refers to the overall plan, structure or strategy that guides a research project , from its conception to the final data analysis. A good research design serves as the blueprint for how you, as the researcher, will collect and analyse data while ensuring consistency, reliability and validity throughout your study.

Understanding different types of research designs is essential as helps ensure that your approach is suitable given your research aims, objectives and questions , as well as the resources you have available to you. Without a clear big-picture view of how you’ll design your research, you run the risk of potentially making misaligned choices in terms of your methodology – especially your sampling , data collection and data analysis decisions.

The problem with defining research design…

One of the reasons students struggle with a clear definition of research design is because the term is used very loosely across the internet, and even within academia.

Some sources claim that the three research design types are qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods , which isn’t quite accurate (these just refer to the type of data that you’ll collect and analyse). Other sources state that research design refers to the sum of all your design choices, suggesting it’s more like a research methodology . Others run off on other less common tangents. No wonder there’s confusion!

In this article, we’ll clear up the confusion. We’ll explain the most common research design types for both qualitative and quantitative research projects, whether that is for a full dissertation or thesis, or a smaller research paper or article.

Research Design: Quantitative Studies

Quantitative research involves collecting and analysing data in a numerical form. Broadly speaking, there are four types of quantitative research designs: descriptive , correlational , experimental , and quasi-experimental .

Descriptive Research Design

As the name suggests, descriptive research design focuses on describing existing conditions, behaviours, or characteristics by systematically gathering information without manipulating any variables. In other words, there is no intervention on the researcher’s part – only data collection.

For example, if you’re studying smartphone addiction among adolescents in your community, you could deploy a survey to a sample of teens asking them to rate their agreement with certain statements that relate to smartphone addiction. The collected data would then provide insight regarding how widespread the issue may be – in other words, it would describe the situation.

The key defining attribute of this type of research design is that it purely describes the situation . In other words, descriptive research design does not explore potential relationships between different variables or the causes that may underlie those relationships. Therefore, descriptive research is useful for generating insight into a research problem by describing its characteristics . By doing so, it can provide valuable insights and is often used as a precursor to other research design types.

Correlational Research Design

Correlational design is a popular choice for researchers aiming to identify and measure the relationship between two or more variables without manipulating them . In other words, this type of research design is useful when you want to know whether a change in one thing tends to be accompanied by a change in another thing.

For example, if you wanted to explore the relationship between exercise frequency and overall health, you could use a correlational design to help you achieve this. In this case, you might gather data on participants’ exercise habits, as well as records of their health indicators like blood pressure, heart rate, or body mass index. Thereafter, you’d use a statistical test to assess whether there’s a relationship between the two variables (exercise frequency and health).

As you can see, correlational research design is useful when you want to explore potential relationships between variables that cannot be manipulated or controlled for ethical, practical, or logistical reasons. It is particularly helpful in terms of developing predictions , and given that it doesn’t involve the manipulation of variables, it can be implemented at a large scale more easily than experimental designs (which will look at next).

That said, it’s important to keep in mind that correlational research design has limitations – most notably that it cannot be used to establish causality . In other words, correlation does not equal causation . To establish causality, you’ll need to move into the realm of experimental design, coming up next…

Need a helping hand?

Experimental Research Design

Experimental research design is used to determine if there is a causal relationship between two or more variables . With this type of research design, you, as the researcher, manipulate one variable (the independent variable) while controlling others (dependent variables). Doing so allows you to observe the effect of the former on the latter and draw conclusions about potential causality.

For example, if you wanted to measure if/how different types of fertiliser affect plant growth, you could set up several groups of plants, with each group receiving a different type of fertiliser, as well as one with no fertiliser at all. You could then measure how much each plant group grew (on average) over time and compare the results from the different groups to see which fertiliser was most effective.

Overall, experimental research design provides researchers with a powerful way to identify and measure causal relationships (and the direction of causality) between variables. However, developing a rigorous experimental design can be challenging as it’s not always easy to control all the variables in a study. This often results in smaller sample sizes , which can reduce the statistical power and generalisability of the results.

Moreover, experimental research design requires random assignment . This means that the researcher needs to assign participants to different groups or conditions in a way that each participant has an equal chance of being assigned to any group (note that this is not the same as random sampling ). Doing so helps reduce the potential for bias and confounding variables . This need for random assignment can lead to ethics-related issues . For example, withholding a potentially beneficial medical treatment from a control group may be considered unethical in certain situations.

Quasi-Experimental Research Design

Quasi-experimental research design is used when the research aims involve identifying causal relations , but one cannot (or doesn’t want to) randomly assign participants to different groups (for practical or ethical reasons). Instead, with a quasi-experimental research design, the researcher relies on existing groups or pre-existing conditions to form groups for comparison.

For example, if you were studying the effects of a new teaching method on student achievement in a particular school district, you may be unable to randomly assign students to either group and instead have to choose classes or schools that already use different teaching methods. This way, you still achieve separate groups, without having to assign participants to specific groups yourself.

Naturally, quasi-experimental research designs have limitations when compared to experimental designs. Given that participant assignment is not random, it’s more difficult to confidently establish causality between variables, and, as a researcher, you have less control over other variables that may impact findings.

All that said, quasi-experimental designs can still be valuable in research contexts where random assignment is not possible and can often be undertaken on a much larger scale than experimental research, thus increasing the statistical power of the results. What’s important is that you, as the researcher, understand the limitations of the design and conduct your quasi-experiment as rigorously as possible, paying careful attention to any potential confounding variables .

Research Design: Qualitative Studies

There are many different research design types when it comes to qualitative studies, but here we’ll narrow our focus to explore the “Big 4”. Specifically, we’ll look at phenomenological design, grounded theory design, ethnographic design, and case study design.

Phenomenological Research Design

Phenomenological design involves exploring the meaning of lived experiences and how they are perceived by individuals. This type of research design seeks to understand people’s perspectives , emotions, and behaviours in specific situations. Here, the aim for researchers is to uncover the essence of human experience without making any assumptions or imposing preconceived ideas on their subjects.

For example, you could adopt a phenomenological design to study why cancer survivors have such varied perceptions of their lives after overcoming their disease. This could be achieved by interviewing survivors and then analysing the data using a qualitative analysis method such as thematic analysis to identify commonalities and differences.

Phenomenological research design typically involves in-depth interviews or open-ended questionnaires to collect rich, detailed data about participants’ subjective experiences. This richness is one of the key strengths of phenomenological research design but, naturally, it also has limitations. These include potential biases in data collection and interpretation and the lack of generalisability of findings to broader populations.

Grounded Theory Research Design

Grounded theory (also referred to as “GT”) aims to develop theories by continuously and iteratively analysing and comparing data collected from a relatively large number of participants in a study. It takes an inductive (bottom-up) approach, with a focus on letting the data “speak for itself”, without being influenced by preexisting theories or the researcher’s preconceptions.

As an example, let’s assume your research aims involved understanding how people cope with chronic pain from a specific medical condition, with a view to developing a theory around this. In this case, grounded theory design would allow you to explore this concept thoroughly without preconceptions about what coping mechanisms might exist. You may find that some patients prefer cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) while others prefer to rely on herbal remedies. Based on multiple, iterative rounds of analysis, you could then develop a theory in this regard, derived directly from the data (as opposed to other preexisting theories and models).

Grounded theory typically involves collecting data through interviews or observations and then analysing it to identify patterns and themes that emerge from the data. These emerging ideas are then validated by collecting more data until a saturation point is reached (i.e., no new information can be squeezed from the data). From that base, a theory can then be developed .

As you can see, grounded theory is ideally suited to studies where the research aims involve theory generation , especially in under-researched areas. Keep in mind though that this type of research design can be quite time-intensive , given the need for multiple rounds of data collection and analysis.

Ethnographic Research Design

Ethnographic design involves observing and studying a culture-sharing group of people in their natural setting to gain insight into their behaviours, beliefs, and values. The focus here is on observing participants in their natural environment (as opposed to a controlled environment). This typically involves the researcher spending an extended period of time with the participants in their environment, carefully observing and taking field notes .

All of this is not to say that ethnographic research design relies purely on observation. On the contrary, this design typically also involves in-depth interviews to explore participants’ views, beliefs, etc. However, unobtrusive observation is a core component of the ethnographic approach.

As an example, an ethnographer may study how different communities celebrate traditional festivals or how individuals from different generations interact with technology differently. This may involve a lengthy period of observation, combined with in-depth interviews to further explore specific areas of interest that emerge as a result of the observations that the researcher has made.

As you can probably imagine, ethnographic research design has the ability to provide rich, contextually embedded insights into the socio-cultural dynamics of human behaviour within a natural, uncontrived setting. Naturally, however, it does come with its own set of challenges, including researcher bias (since the researcher can become quite immersed in the group), participant confidentiality and, predictably, ethical complexities . All of these need to be carefully managed if you choose to adopt this type of research design.

Case Study Design

With case study research design, you, as the researcher, investigate a single individual (or a single group of individuals) to gain an in-depth understanding of their experiences, behaviours or outcomes. Unlike other research designs that are aimed at larger sample sizes, case studies offer a deep dive into the specific circumstances surrounding a person, group of people, event or phenomenon, generally within a bounded setting or context .

As an example, a case study design could be used to explore the factors influencing the success of a specific small business. This would involve diving deeply into the organisation to explore and understand what makes it tick – from marketing to HR to finance. In terms of data collection, this could include interviews with staff and management, review of policy documents and financial statements, surveying customers, etc.

While the above example is focused squarely on one organisation, it’s worth noting that case study research designs can have different variation s, including single-case, multiple-case and longitudinal designs. As you can see in the example, a single-case design involves intensely examining a single entity to understand its unique characteristics and complexities. Conversely, in a multiple-case design , multiple cases are compared and contrasted to identify patterns and commonalities. Lastly, in a longitudinal case design , a single case or multiple cases are studied over an extended period of time to understand how factors develop over time.

As you can see, a case study research design is particularly useful where a deep and contextualised understanding of a specific phenomenon or issue is desired. However, this strength is also its weakness. In other words, you can’t generalise the findings from a case study to the broader population. So, keep this in mind if you’re considering going the case study route.

How To Choose A Research Design

Having worked through all of these potential research designs, you’d be forgiven for feeling a little overwhelmed and wondering, “ But how do I decide which research design to use? ”. While we could write an entire post covering that alone, here are a few factors to consider that will help you choose a suitable research design for your study.

Data type: The first determining factor is naturally the type of data you plan to be collecting – i.e., qualitative or quantitative. This may sound obvious, but we have to be clear about this – don’t try to use a quantitative research design on qualitative data (or vice versa)!

Research aim(s) and question(s): As with all methodological decisions, your research aim and research questions will heavily influence your research design. For example, if your research aims involve developing a theory from qualitative data, grounded theory would be a strong option. Similarly, if your research aims involve identifying and measuring relationships between variables, one of the experimental designs would likely be a better option.

Time: It’s essential that you consider any time constraints you have, as this will impact the type of research design you can choose. For example, if you’ve only got a month to complete your project, a lengthy design such as ethnography wouldn’t be a good fit.

Resources: Take into account the resources realistically available to you, as these need to factor into your research design choice. For example, if you require highly specialised lab equipment to execute an experimental design, you need to be sure that you’ll have access to that before you make a decision.

Keep in mind that when it comes to research, it’s important to manage your risks and play as conservatively as possible. If your entire project relies on you achieving a huge sample, having access to niche equipment or holding interviews with very difficult-to-reach participants, you’re creating risks that could kill your project. So, be sure to think through your choices carefully and make sure that you have backup plans for any existential risks. Remember that a relatively simple methodology executed well generally will typically earn better marks than a highly-complex methodology executed poorly.

Recap: Key Takeaways

We’ve covered a lot of ground here. Let’s recap by looking at the key takeaways:

- Research design refers to the overall plan, structure or strategy that guides a research project, from its conception to the final analysis of data.

- Research designs for quantitative studies include descriptive , correlational , experimental and quasi-experimenta l designs.

- Research designs for qualitative studies include phenomenological , grounded theory , ethnographic and case study designs.

- When choosing a research design, you need to consider a variety of factors, including the type of data you’ll be working with, your research aims and questions, your time and the resources available to you.

If you need a helping hand with your research design (or any other aspect of your research), check out our private coaching services .

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

10 Comments

Is there any blog article explaining more on Case study research design? Is there a Case study write-up template? Thank you.

Thanks this was quite valuable to clarify such an important concept.

Thanks for this simplified explanations. it is quite very helpful.

This was really helpful. thanks

Thank you for your explanation. I think case study research design and the use of secondary data in researches needs to be talked about more in your videos and articles because there a lot of case studies research design tailored projects out there.

Please is there any template for a case study research design whose data type is a secondary data on your repository?

This post is very clear, comprehensive and has been very helpful to me. It has cleared the confusion I had in regard to research design and methodology.

This post is helpful, easy to understand, and deconstructs what a research design is. Thanks

how to cite this page

Thank you very much for the post. It is wonderful and has cleared many worries in my mind regarding research designs. I really appreciate .

how can I put this blog as my reference(APA style) in bibliography part?

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

How to choose your study design

Affiliation.

- 1 Department of Medicine, Sydney Medical School, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia.

- PMID: 32479703

- DOI: 10.1111/jpc.14929

Research designs are broadly divided into observational studies (i.e. cross-sectional; case-control and cohort studies) and experimental studies (randomised control trials, RCTs). Each design has a specific role, and each has both advantages and disadvantages. Moreover, while the typical RCT is a parallel group design, there are now many variants to consider. It is important that both researchers and paediatricians are aware of the role of each study design, their respective pros and cons, and the inherent risk of bias with each design. While there are numerous quantitative study designs available to researchers, the final choice is dictated by two key factors. First, by the specific research question. That is, if the question is one of 'prevalence' (disease burden) then the ideal is a cross-sectional study; if it is a question of 'harm' - a case-control study; prognosis - a cohort and therapy - a RCT. Second, by what resources are available to you. This includes budget, time, feasibility re-patient numbers and research expertise. All these factors will severely limit the choice. While paediatricians would like to see more RCTs, these require a huge amount of resources, and in many situations will be unethical (e.g. potentially harmful intervention) or impractical (e.g. rare diseases). This paper gives a brief overview of the common study types, and for those embarking on such studies you will need far more comprehensive, detailed sources of information.

Keywords: experimental studies; observational studies; research method.

© 2020 Paediatrics and Child Health Division (The Royal Australasian College of Physicians).

- Case-Control Studies

- Cross-Sectional Studies

- Research Design*

Experimental Research Design — 6 mistakes you should never make!

Since school days’ students perform scientific experiments that provide results that define and prove the laws and theorems in science. These experiments are laid on a strong foundation of experimental research designs.

An experimental research design helps researchers execute their research objectives with more clarity and transparency.

In this article, we will not only discuss the key aspects of experimental research designs but also the issues to avoid and problems to resolve while designing your research study.

Table of Contents

What Is Experimental Research Design?

Experimental research design is a framework of protocols and procedures created to conduct experimental research with a scientific approach using two sets of variables. Herein, the first set of variables acts as a constant, used to measure the differences of the second set. The best example of experimental research methods is quantitative research .

Experimental research helps a researcher gather the necessary data for making better research decisions and determining the facts of a research study.

When Can a Researcher Conduct Experimental Research?

A researcher can conduct experimental research in the following situations —

- When time is an important factor in establishing a relationship between the cause and effect.

- When there is an invariable or never-changing behavior between the cause and effect.

- Finally, when the researcher wishes to understand the importance of the cause and effect.

Importance of Experimental Research Design

To publish significant results, choosing a quality research design forms the foundation to build the research study. Moreover, effective research design helps establish quality decision-making procedures, structures the research to lead to easier data analysis, and addresses the main research question. Therefore, it is essential to cater undivided attention and time to create an experimental research design before beginning the practical experiment.

By creating a research design, a researcher is also giving oneself time to organize the research, set up relevant boundaries for the study, and increase the reliability of the results. Through all these efforts, one could also avoid inconclusive results. If any part of the research design is flawed, it will reflect on the quality of the results derived.

Types of Experimental Research Designs

Based on the methods used to collect data in experimental studies, the experimental research designs are of three primary types:

1. Pre-experimental Research Design

A research study could conduct pre-experimental research design when a group or many groups are under observation after implementing factors of cause and effect of the research. The pre-experimental design will help researchers understand whether further investigation is necessary for the groups under observation.

Pre-experimental research is of three types —

- One-shot Case Study Research Design

- One-group Pretest-posttest Research Design

- Static-group Comparison

2. True Experimental Research Design

A true experimental research design relies on statistical analysis to prove or disprove a researcher’s hypothesis. It is one of the most accurate forms of research because it provides specific scientific evidence. Furthermore, out of all the types of experimental designs, only a true experimental design can establish a cause-effect relationship within a group. However, in a true experiment, a researcher must satisfy these three factors —

- There is a control group that is not subjected to changes and an experimental group that will experience the changed variables

- A variable that can be manipulated by the researcher

- Random distribution of the variables

This type of experimental research is commonly observed in the physical sciences.

3. Quasi-experimental Research Design

The word “Quasi” means similarity. A quasi-experimental design is similar to a true experimental design. However, the difference between the two is the assignment of the control group. In this research design, an independent variable is manipulated, but the participants of a group are not randomly assigned. This type of research design is used in field settings where random assignment is either irrelevant or not required.

The classification of the research subjects, conditions, or groups determines the type of research design to be used.

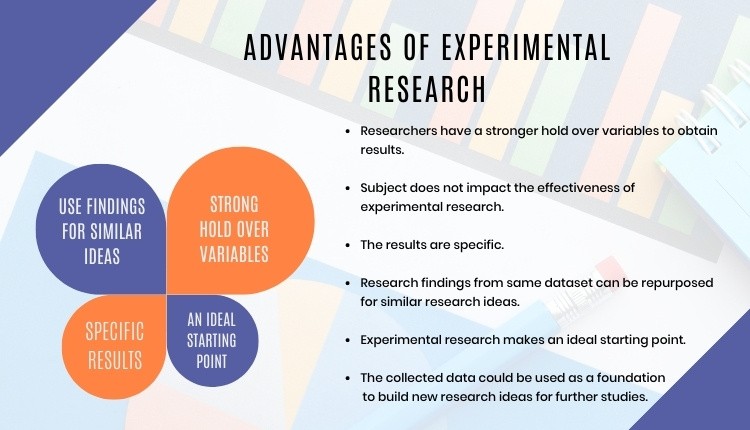

Advantages of Experimental Research

Experimental research allows you to test your idea in a controlled environment before taking the research to clinical trials. Moreover, it provides the best method to test your theory because of the following advantages:

- Researchers have firm control over variables to obtain results.

- The subject does not impact the effectiveness of experimental research. Anyone can implement it for research purposes.

- The results are specific.

- Post results analysis, research findings from the same dataset can be repurposed for similar research ideas.

- Researchers can identify the cause and effect of the hypothesis and further analyze this relationship to determine in-depth ideas.

- Experimental research makes an ideal starting point. The collected data could be used as a foundation to build new research ideas for further studies.

6 Mistakes to Avoid While Designing Your Research

There is no order to this list, and any one of these issues can seriously compromise the quality of your research. You could refer to the list as a checklist of what to avoid while designing your research.

1. Invalid Theoretical Framework

Usually, researchers miss out on checking if their hypothesis is logical to be tested. If your research design does not have basic assumptions or postulates, then it is fundamentally flawed and you need to rework on your research framework.

2. Inadequate Literature Study

Without a comprehensive research literature review , it is difficult to identify and fill the knowledge and information gaps. Furthermore, you need to clearly state how your research will contribute to the research field, either by adding value to the pertinent literature or challenging previous findings and assumptions.

3. Insufficient or Incorrect Statistical Analysis

Statistical results are one of the most trusted scientific evidence. The ultimate goal of a research experiment is to gain valid and sustainable evidence. Therefore, incorrect statistical analysis could affect the quality of any quantitative research.

4. Undefined Research Problem

This is one of the most basic aspects of research design. The research problem statement must be clear and to do that, you must set the framework for the development of research questions that address the core problems.

5. Research Limitations

Every study has some type of limitations . You should anticipate and incorporate those limitations into your conclusion, as well as the basic research design. Include a statement in your manuscript about any perceived limitations, and how you considered them while designing your experiment and drawing the conclusion.

6. Ethical Implications

The most important yet less talked about topic is the ethical issue. Your research design must include ways to minimize any risk for your participants and also address the research problem or question at hand. If you cannot manage the ethical norms along with your research study, your research objectives and validity could be questioned.

Experimental Research Design Example

In an experimental design, a researcher gathers plant samples and then randomly assigns half the samples to photosynthesize in sunlight and the other half to be kept in a dark box without sunlight, while controlling all the other variables (nutrients, water, soil, etc.)

By comparing their outcomes in biochemical tests, the researcher can confirm that the changes in the plants were due to the sunlight and not the other variables.

Experimental research is often the final form of a study conducted in the research process which is considered to provide conclusive and specific results. But it is not meant for every research. It involves a lot of resources, time, and money and is not easy to conduct, unless a foundation of research is built. Yet it is widely used in research institutes and commercial industries, for its most conclusive results in the scientific approach.

Have you worked on research designs? How was your experience creating an experimental design? What difficulties did you face? Do write to us or comment below and share your insights on experimental research designs!

Frequently Asked Questions

Randomization is important in an experimental research because it ensures unbiased results of the experiment. It also measures the cause-effect relationship on a particular group of interest.

Experimental research design lay the foundation of a research and structures the research to establish quality decision making process.

There are 3 types of experimental research designs. These are pre-experimental research design, true experimental research design, and quasi experimental research design.

The difference between an experimental and a quasi-experimental design are: 1. The assignment of the control group in quasi experimental research is non-random, unlike true experimental design, which is randomly assigned. 2. Experimental research group always has a control group; on the other hand, it may not be always present in quasi experimental research.

Experimental research establishes a cause-effect relationship by testing a theory or hypothesis using experimental groups or control variables. In contrast, descriptive research describes a study or a topic by defining the variables under it and answering the questions related to the same.

good and valuable

Very very good

Good presentation.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

![importance of research study design What is Academic Integrity and How to Uphold it [FREE CHECKLIST]](https://www.enago.com/academy/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/FeatureImages-59-210x136.png)

Ensuring Academic Integrity and Transparency in Academic Research: A comprehensive checklist for researchers

Academic integrity is the foundation upon which the credibility and value of scientific findings are…

- Publishing Research

- Reporting Research

How to Optimize Your Research Process: A step-by-step guide

For researchers across disciplines, the path to uncovering novel findings and insights is often filled…

- Industry News

- Trending Now

Breaking Barriers: Sony and Nature unveil “Women in Technology Award”

Sony Group Corporation and the prestigious scientific journal Nature have collaborated to launch the inaugural…

Achieving Research Excellence: Checklist for good research practices

Academia is built on the foundation of trustworthy and high-quality research, supported by the pillars…

- Promoting Research

Plain Language Summary — Communicating your research to bridge the academic-lay gap

Science can be complex, but does that mean it should not be accessible to the…

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for…

Comparing Cross Sectional and Longitudinal Studies: 5 steps for choosing the right…

Research Recommendations – Guiding policy-makers for evidence-based decision making

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

As a researcher, what do you consider most when choosing an image manipulation detector?

- Interesting

- Scholarships

- UGC-CARE Journals

What is a Research Design? Importance and Types

Why Research Design is Important for a Researcher?

A research design is a systematic procedure or an idea to carry out different tasks of the research study. It is important to know the research design and its types for the researcher to carry out the work in a proper way.

The purpose of research design is that enable the researcher to proceed in the right direction without any deviation from the tasks. It is an overall detailed strategy of the research process.

The design of experiments is a very important aspect of a research study. A poor research design may collapse the entire research project in terms of time, manpower, and money.

7 Importance of Research Design – iLovePhD

What is a Research Design in Research Methodology ?

A research design is a plan or framework for conducting research. It includes a set of plans and procedures that aim to produce reliable and valid data. The research design must be appropriate to the type of research question being asked and the type of data being collected.

A typical research design is a detailed methodology or a roadmap for the successful completion of any research work. ilovephd.com

Importance of Research Design

A Good research design consists of the following important points:

- Formulating a research design helps the researcher to make correct decisions in each and every step of the study.

- It helps to identify the major and minor tasks of the study.

- It makes the research study effective and interesting by providing minute details at each step of the research process.

- Based on the design of experiments (research design), a researcher can easily frame the objectives of the research work.

- A good research design helps the researcher to complete the objectives of the study in a given time and facilitates getting the best solution for the research problems .

- It helps the researcher to complete all the tasks even with limited resources in a better way.

- The main advantage of a good research design is that it provides accuracy, reliability, consistency, and legitimacy to the research.

How to Create a Research Design?

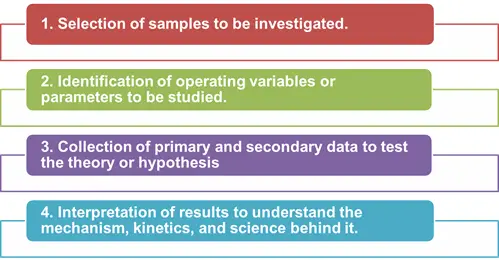

According to Thyer, the research design has the following components:

- A researcher begins the study by framing the problem statement of the research work.

- Then, the researcher has to identify the sampling points, the number of samples, the sample size, and the location.

- The next step is to identify the operating variables or parameters of the study and detail how the variables are to be measured.

- The final step is the collection, interpretation, and dissemination of results.

Considerations in selecting the research design

The researchers should know the various types of research designs and their applicability. The selection of a research design can only be made after a careful understanding of the different research design types . The factors to be considered in choosing a research design are

- Qualitative Vs quantitative

- Basic Vs applied

- Empirical Vs Non-empirical

Types of Research Design?

There are four main types of research designs: experimental, observational, quasi-experimental, and descriptive.

- Experimental designs: are used to test cause-and-effect relationships. In an experiment, the researcher manipulates one or more independent variables and observes the effect on a dependent variable.

- Observational designs are used to study behavior without manipulating any variables. The researcher simply observes and records the behavior.

- Quasi-experimental designs are used when it is not possible to manipulate the independent variable. The researcher uses a naturally occurring independent variable and controls for other variables.

- Descriptive designs are used to describe a behavior or phenomenon. The researcher does not manipulate any variables, but simply observes and records the behavior.

I hope, this article would help you to know about what is research design, the types of research design, and what are the important points to be considered in carrying out the research work.

- classification of research design

- experimental research design

- research design

- research design and methodology

- research design and methods

- research design example

- research design explained

- research design in hindi

- research design lecture

- research design meaning

- research design types

- Research Methodology

- research methods

- types of research design

- what is research design

List of Open Access SCI Journals in Computer Science

24 best online plagiarism checker free – 2024, how to write a research paper in a month, leave a reply cancel reply, most popular, scopus indexed journals list 2024, 5 free data analysis and graph plotting software for thesis, the hrd scheme india 2024-25, 6 best online chemical drawing software 2024, imu-simons research fellowship program (2024-2027), india science and research fellowship (isrf) 2024-25, example of abstract for research paper – tips and dos and donts, best for you, what is phd, popular posts, how to check scopus indexed journals 2024, popular category.

- POSTDOC 317

- Interesting 258

- Journals 234

- Fellowship 130

- Research Methodology 102

- All Scopus Indexed Journals 92

iLovePhD is a research education website to know updated research-related information. It helps researchers to find top journals for publishing research articles and get an easy manual for research tools. The main aim of this website is to help Ph.D. scholars who are working in various domains to get more valuable ideas to carry out their research. Learn the current groundbreaking research activities around the world, love the process of getting a Ph.D.

Contact us: [email protected]

Google News

Copyright © 2024 iLovePhD. All rights reserved

- Artificial intelligence

- Open access

- Published: 31 May 2024

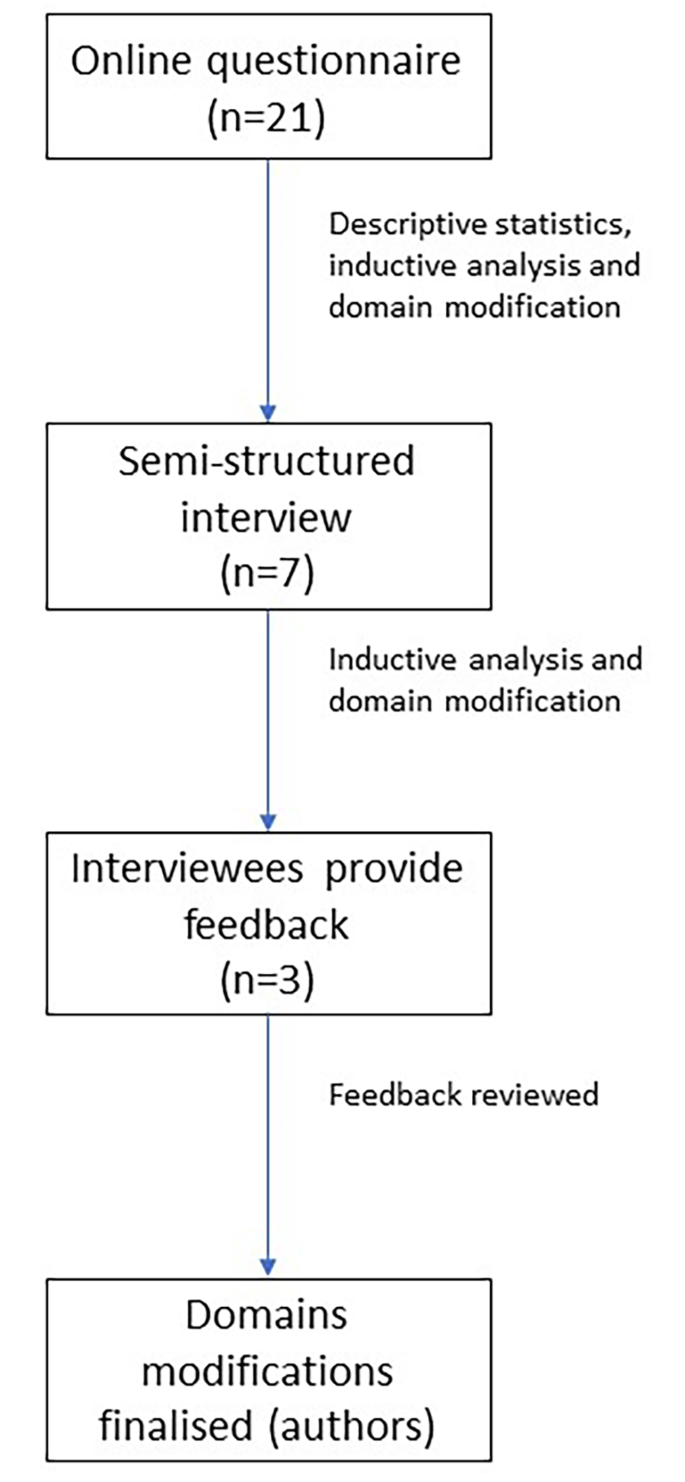

Modifications of the readiness assessment for pragmatic trials tool for appropriate use with Indigenous populations

- Joanna Hikaka 1 ,

- Ellen M. McCreedy 2 , 3 ,

- Eric Jutkowitz 3 , 4 ,

- Ellen P. McCarthy 5 , 6 &

- Rosa R. Baier 2 , 3

BMC Medical Research Methodology volume 24 , Article number: 121 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details